ABSTRACT

In recent years, thousands of posthole features have been located during open-area excavations of Indigenous archaeological sites in the Caribbean Islands. However, the reconstruction of village spatial organization and its changes over time is sometimes a challenging task, because Indigenous village occupation can span more than 500 years. This article presents archaeological data from rescue excavations at Argyle, an Indigenous village site dating to the late pre-colonial and early colonial period on Saint Vincent Island in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean Islands. The archaeological data are juxtaposed with an ethnographic reading of seventeenth-century European documentary sources of the Lesser Antilles and two ethnoarchaeological village studies conducted with Arawakan and Cariban-speaking peoples in the Tropical Lowlands of mainland South America. This study demonstrates the value of an integrated approach in understanding the Argyle site and conceptualizing the dynamics of Indigenous village settlements in the wider Circum-Caribbean area.

Introduction

In this article we compare and integrate archaeological, ethnohistoric, and ethnoarchaeological evidence to better understand village layout and dynamics at pre-colonial and early colonial sites in the Lesser Antilles. Approximately 2,500 years ago, Ceramic Age people migrated from northern South America into the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico and settled permanently there. Several hundred years later, around AD 400, these people also settled on the larger islands of the Greater Antilles to the east (e.g. Fernandes et al. Citation2021; Fitzpatrick Citation2015; Keegan and Hofman Citation2017; Nägele et al. Citation2020; Reid Citation2018). During the late pre-colonial period (cal. AD 1200–1500), the density of settlement increased in both the coastal and inland areas of the Caribbean islands (Keegan and Hofman Citation2017).

Caribbean archaeology has long focused on small-scale excavation units with the goal of building chronologies and understanding stratigraphy (e.g. Rouse Citation1992). However, there has been a recent trend toward larger-scale open-area excavations and a focus on posthole configurations and settlement layout (e.g. Hofman et al. Citation2020a; Hoogland Citation1996; Rivera and Rodríguez Citation1991; Samson Citation2010; Samson et al. Citation2015; Siegel Citation1989; Bel and Romon Citation2010; Versteeg and Rostain Citation1997; Versteeg and Schinkel Citation1992). The number of rescue archaeology projects has risen in response to the construction of hotels, golf courses, airports, and the increasing natural impacts on archaeological sites in the archipelago. Heavy machinery is often used in construction with potentially detrimental outcomes for the archaeological record. Engaging local communities and other stakeholders is necessary to support rescue archaeology and prevent the records of the past from being lost forever in the geopolitically diverse islandscape of the Caribbean, where heritage legislation is in many cases non-existent or minimally implemented (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2016; Siegel et al. Citation2013).

This article presents the results of rescue excavations conducted in 2009 and 2010 at the Argyle site on Saint Vincent Island in the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles. The site dates to the late pre-colonial/early colonial period, i.e. AD 1445–1650 (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012, Citation2018; Hofman, Hoogland, and Roux Citation2015). It was threatened with destruction by the development of the Argyle International Airport. In collaboration with the Saint Vincent and the Grenadines National Trust and the International Airport Development Company, we conducted large-scale rescue excavations and documented numerous postholes, Cayo and European material culture, and other features associated with fifteenth to seventeenth century “Island Carib” sites. Affiliation with the mainland Guianas was established by the relationship between Cayo and Koriabo ceramics, which are ancestral to the ceramics of contemporary Kali’na communities of the mainland Guianas (Boomert Citation1986; Hofman et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020c).

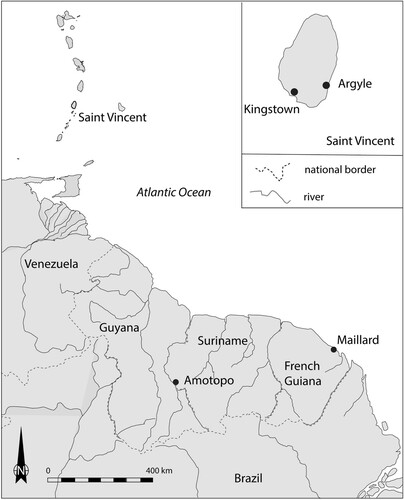

To make sense of the archaeological evidence from the Argyle site excavations, we compare the archaeological data with seventeenth-century European documentary sources on the Island Carib and two ethnoarchaeological case studies from the Tropical Lowlands of mainland South America. The ethnoarchaeological research was conducted among Cariban and Arawakan-speaking peoples, respectively, in the Palikur village of Maillard in French Guiana and the Trio village of Amotopo in Suriname (). The two ethnoarchaeological case studies were undertaken when large-scale excavations focused on postholes and other features had become more common in the region, though prior to the excavations at Argyle. To address questions of regional archaeology, the ethnoarchaeological studies of Maillard and Amotopo were focused on archaeologically-relevant features such as postholes, drip-lines, pits, refuse deposits, and hearths. Consequently, these ethnoarchaeological features can be compared readily with the archaeological features at the Argyle site. By comparing the three datasets in this article, our goal is to apply ethnohistory and ethnoarchaeology to better understand and conceptualize village layout and dynamics at archaeological sites in the Caribbean islands and the wider Circum-Caribbean area.

Figure 1. General map of the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles and the Guianas indicating the locations of Argyle (Saint Vincent), Amotopo (Surinam), and Maillard (French Guiana). (Drawing by Menno L.P. Hoogland).

Juxtaposing Archaeological with Ethnohistorical and Ethnoarchaeological Datasets

Ethnoarchaeological and actualistic studies (Kroll and Price Citation2013) in South America developed in tandem with the archaeology of the pre-colonial period. However, ethnoarchaeological studies concerning the Amazonian house are few. In the 1970s, Annette Laming-Emperaire and colleagues (Citation1978) conducted an interesting ethnoarchaeological investigation at a Xetá settlement in Brazil, focused on the lithic technology that its inhabitants still used. Following the pioneering work of Donald Lathrap (DeBoer and Lathrap Citation1979), his students conducted ethnoarchaeological research in various areas of the South American lowlands in the 1980s. In the eastern foothills of the Peruvian Andes, Peter G. Roe and Peter E. Siegel (Citation1982; Siegel and Roe Citation1986) evaluated the organization of two Shipibo dwelling compounds, one still inhabited and the other recently abandoned, to establish correspondence between use and discard areas. Subsequently, Siegel (Citation1990a, Citation1990b) studied the relationship between the demographic and architectural organization of a Waiwai village in Guyana. James Zeidler (Citation1983) made a complete inventory of an Achuar household in Ecuador and classified the importance of each group of artifacts and all activity areas. The Brazilian edited volume Habitações Indigenas also provides useful data on the country’s Indigenous habitations (Caiuby Novaes Citation1983). More recently, Brenda Bowser (Citation2000; Bowser and Patton Citation2004) analyzed the gender-based division of activities and spaces in Achuar and Kichwa houses in Ecuador, and Stéphen Rostain used ethnoarchaeology to identify the organization of a domestic floor during a horizontal excavation of a pre-Columbian proto-Jivaro house at the Sangay site, Ecuador (Rostain Citation2006, Citation2011). Gustavo Politis (Citation2007) conducted detailed research on the activities of the Nukak, hunter-gatherers in Colombia, which illuminates the spatial organization of activities at their habitation sites Additionally, Ogeron et al. (Citation2018) provided useful data on the construction techniques of the Palikur and their choice of tree species in French Guiana. However, few researchers of the cultures in the Tropical Lowlands have conducted comparative studies integrating ethnoarchaeological investigations and archaeological excavations (but see Barreto Citation2015; Bassi Citation2016; DeBoer, Kintigh, and Rostoker Citation1996; Politis Citation2002; Rostain Citation2011; Wüst Citation1998). In all of the studies reviewed, there have been few attempts to cross-reference the data, hypotheses, and interpretations of these two fields of research. Moreover, with some notable exceptions (e.g. Heckenberger and Petersen Citation1995 on circular village patterns; Hofman, Daan Isendoorn, and Booden Citation2008 on ceramic production; Roe Citation1997 on Taino shamanism; Siegel Citation1989 on site organization in the Caribbean; Torres Citation2005 on communities and social landscapes; Versteeg Citation1989 on internal organization of settlements), correlations between the Tropical Lowlands and the insular Caribbean are seldom made.

This trend toward the study of residential spaces in Lowland South America and the Caribbean has to be revived, and ideas between the two disciplines and the two geographical and cultural areas should be shared and applied. We are fully aware that this exchange cannot take place without respecting the undeniably different contexts of the insular Caribbean and the Tropical Lowlands of South America and recognizing their mutual influence on archaeological interpretations. It is, of course, important to acknowledge that the present situation is radically different from the past. Major changes in demography, socio-political systems, land availability, landscape, and group relationships, to name but a few impacts, were experienced by the Indigenous peoples of the insular Caribbean after European colonization (e.g. Boomert Citation2016; Castilla-Beltrán et al. Citation2018; Hofman, Ramos, and Pagán-Jiménez Citation2018, Citation2020b). As noted by many for Tropical Lowlands of South America, even where contemporary Indigenous peoples are the heirs to the lands of their pre-colonial ancestors, they fundamentally differ from their predecessors in many respects (DeBoer and Lathrap Citation1979; Meggers and Evans Citation1979; Politis Citation2002; Siegel Citation2014; Siegel and Roe Citation1986; Wüst Citation1998; Yu Citation2015; Zeidler Citation1983, Citation2014).

One of the main objectives of the two ethnoarchaeological case studies discussed in this article was to evaluate the validity of reasoning used by archaeologists to explain their data. In both ethnoarchaeological studies, detailed mapping of the village lay-out and documentation of the structures was accomplished, followed by ethnographic observations and interviews. In this article, these ethnoarchaeological datasets are compared with the posthole configurations at the Argyle archaeological site to better understand and conceptualize the layout(s) of the village and its dynamics through time. By comparing the datasets, it is expected that misidentifications and distortions in interpretations of village organization in the archaeological record will be revealed. For similar studies, see DeBoer, Kintigh, and Rostoker (Citation1996) on site reoccupation; DeBoer and Lathrap (Citation1979) on the implications of ethnography for archaeology; Meggers and Evans (Citation1979) on an experimental reconstruction of Taruma village succession and some implications; Siegel and Roe (Citation1986) on the ethnoarchaeology of site formation processes and archaeological Interpretation; and Zeidler (Citation1983) on the ethnoarchaeology of an Achuar house. This approach has been successfully applied in the archaeology of other regions of the world as well (see Agorsah et al. Citation1985 for Ghana; Friesem and Lavi Citation2017 for India; Kahn and Kirch Citation2004 for Polynesia; and Kus and Raharijaona Citation2000 for Madagascar).

It should be emphasized, however, that the case studies of the villages of Maillard and Amotopo were primarily conducted as research projects in their own right and were not originally meant to be “means to an end” for the purpose of enhancing archaeological interpretations and conceptualizations (see Buchli and Lucas Citation2001, 4; Gosden and Marshall Citation1999, 9; Meskell Citation2005, 82). Therefore, in the context of this article, we aim to clearly explain and explicitly contrast past and present archaeological and ethnoarchaeological cases rather than implicitly importing anthropological interpretations deprived of their specific formative contexts (see also Spriggs Citation2008).

Mainland-island-mainland Connections

The Cariban and Arawakan Connection in the Lesser Antilles and Guiana Region: Arawak – Palikur – Trio – Kali’na – Kalinago

The Lesser Antilles and the northern part of mainland South America, especially the Guianas, were originally understood by anthropologists to represent the Indigenous Carib heartland (see Basso Citation1977; Rivière Citation1984; Whitehead Citation1994, Citation1995). Although this still holds true, Indigenous identities and linguistic associations in this area are more diverse than previously understood. Today, Indigenous communities persist, but Indigenous peoples are significantly fewer in number due to centuries of colonialism, forcibly displaced from their territories and living in marginal and inaccessible lands.

The Indigenous communities living in the Lesser Antilles today are multi-ethnic descendant communities of Arawakan and Cariban speakers and Waraoan peoples who were once living in Trinidad and the northern South American mainland (Boomert Citation2016; Hofman and Carlin Citation2010; Hofman et al. Citation2019; Mans Citation2018). According to ethnohistoric sources, the Island Carib people, or Kalinago (male lexicon) and Kalipuna (female lexicon) as they identified themselves, were the early colonial population of the Windward Islands in the Lesser Antilles; according to their own historical accounts, their ancestors moved from the mainland to the islands several centuries prior to European colonization. Their history has long been contested and unsupported by archaeological evidence, but over the past decades, their archaeological traces have been documented in the pre-contact record throughout the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles (Boomert Citation1986; Bright Citation2011; Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012). Archaeologically, the Cayo material culture repertoire represents the Island Carib and reflects the ethnogenesis of a new identity, with cultural elements from both the Greater Antilles (specifically, the Chicoid/Meillacoid ceramic series) and the South American mainland (the Koriabo ceramic complex) (Hofman et al. Citation2020c). Island Carib strongholds are known to have resisted European control until the 1800s (Hofman et al. Citation2019). In more recent centuries, these Indigenous communities became further entangled with Africans and Europeans and over time moved mainly to the most rugged parts of the smaller islands of the Lesser Antilles to establish their settlements. Today, the Kalinago are a community of around 3,000 people living in the only constituted legal Indigenous space in the archipelago, the Kalinago Territory in the northeastern part of Dominica (Honychurch Citation2000). The Kalinago as well as the Black Carib or Garifuna also occupy the northeastern part of Saint Vincent, and some smaller communities are located in its northwestern portion. At present, about 1,500 people in Trinidad consider themselves to be of Indigenous ancestry. The best known are the First Peoples of the Santa Rosa community in the north-central part of the island and the Waroa in the southern part of the island (Boomert Citation2016, 159). Although ethnically and geographically distinct, their traditional houses and village organization appear to be relatively similar to those of their fellow islanders.

The Indigenous communities living in the Guianas are ethnically more diverse and populous. They are part of a multi-ethnic mix of communities with speakers belonging to the Arawakan, Cariban, Waraoan, and Tupian linguistic stocks (Carlin Citation2011). The two ethnoarchaeological case studies that are detailed here were conducted among the Palikur, who are primarily Arawakan speakers, and the Trio, predominantly Cariban speakers.

The Palikur are a coastal Indigenous population living in northern Amapá, Brazil, and along the Oyapock River that forms the boundary between French Guiana and Brazil. The province of Paricura is mentioned for the first time in 1513 by the traveler Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, which suggests that the Palikur have been living in this part of the coastal zone for at least five centuries (Nimuendajú Citation1926). During the colonial period, many different Indigenous groups came to Paricura to flee from European violence on the Orinoco River and at the mouth of the Amazon (Meggers and Evans Citation1957; Whitehead Citation1988, Citation1994). This resulted in a mixture of refugees of various origins creating new ethnicities and identities, which persist today, and the present division of traditional society into exogamic clans (Grenand and Grenand Citation1987). A clear territorial cultural dichotomy has existed during the last four centuries along the coast of the Guianas, delimited by Cayenne Island, reproducing a similar division, which existed during pre-colonial times (Rostain Citation2012). The Kali’na (previously called Galibi by the Europeans) were living on the west side of Cayenne Island up to the central coast of Suriname, while the Palikur and other Arawakan-speaking groups occupied the east side up to northern Amapá. Thus, from the seventeenth century onwards, coastal Guiana was a place of territorial conflict between Cariban and Arawakan-speaking peoples.

Following a drastic demographic decline among the Palikur in the early twentieth century (Nimuendajú Citation1926), with a decrease to 238 individuals mainly attributed to introduced European diseases, there has been a steady increase associated with better access to health care. In 1982, 1,026 Palikur reportedly lived in French Guiana and the state of Amapá in Brazil, increasing to 1,480 individuals in recent years (Grenand and Grenand Citation1994). Today, Palikur culture is strongly influenced by Western society, especially because of pressure from Seventh Day Adventists (Rostain, personal observation), but it still retains many traditional features. The Palikur mostly live in the marshy area of the Oyapock and Uaça rivers. They occupy small hills in the swamps and travel by canoe through the seasonally inundated savannahs and along the rivers. They build their houses on stilts, hunt and fish in the surrounding environment, and cultivate temporary fields of manioc and other crops using slash-and-burn techniques. One of their best-known handicrafts is basketry which they use or trade with other groups. Ceremonial festivities are an essential aspect of their life. The Palikur organize weekly meetings in the central plazas of their villages in order to contact the spirit world through dances, drinks, and shamanistic rituals (IPFEIMK Citation2009).

The Trio are one of the Indigenous populations living in the southern interior of Suriname and the northern part of the Brazilian state of Pará. Although their presence in the Guiana Highlands was reported as early as the first decades of the eighteenth century, more became known about them by outsiders through colonial Dutch expeditions into the interior in the early twentieth century. These expeditions were destined to establish the exact boundary between the colony of Suriname and Brazil in the south and with the other Guianas to the east and west. More permanent contact between the Trio and colonial settlers in the coastal area was established when airstrips were opened in the Surinamese interior in the early 1960s, this time to explore the mineralogical extraction possibilities of the Dutch colony. Simultaneously, the first missionaries settled among the Trio. Today, the Trio are understood to be a fusion of several ethnic communities. They now all speak Trio and self-identify as Trio to outsiders (see Carlin and Mans Citation2015; Mans Citation2014).

This Trio ethnogenesis developed, directly and indirectly, through European and Maroon pressure from the north and Portuguese pressure from Brazil. Like the Palikur and other Indigenous groups in the area, the Trio suffered from an epidemic in the early twentieth century because of contact with outsiders. Fortunately, their population has grown as a result of both fusion and improved health care since the 1960s. In 2007, the Trio-speaking villages in both Suriname and Brazil were estimated to total approximately 2,700 inhabitants (Mans Citation2012, 21). In the darkest times of the early twentieth century the Trio mainly moved by foot and were living in inter-fluvial areas hidden from malevolent strangers. Today they have moved to live near the main river channels where they go fishing and hunting in dugout canoes with outboard engines and fly by small plane to the nearest cities to meet people and exchange their goods. Despite this relatively new modern lifestyle, the physical distance away from the coast means that for subsistence the Trio continue to rely on slash-and-burn cultivation with manioc as their staple and on their catch from fishing and hunting trips. The distance and the resulting transportation difficulties also limit the import of commercial building materials, except for some occasional corrugated metal roof tops. For the construction of their houses, they continue to extract wood from the nearby environment as they have done for as long as they can remember (Mans Citation2012).

The Argyle Site

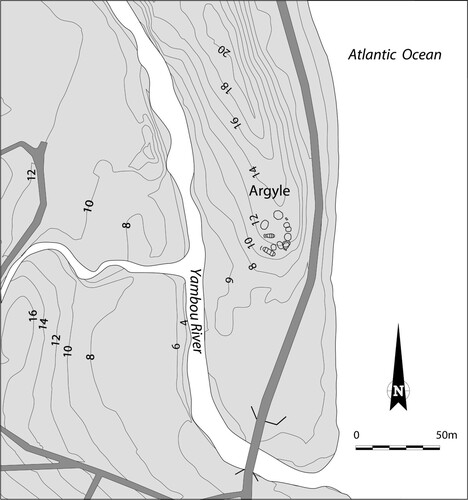

The early colonial archaeological site of Argyle is situated strategically on top of a ridge overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, next to the mouth of the Yambou River in the south-eastern part of Saint Vincent Island (). The Yambou River drains the Mesopotamia Valley, an area known for its many petroglyph sites. The Argyle region has been used extensively in pre-colonial and colonial times (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012).

Large-scale open-area rescue excavations in 2009–2010 in response to the development of the Argyle International Airport exposed a surface area of 2800 m2 with approximately 310 posthole features. Clearance of the site by heavy machinery was necessary due to the dense coverage of standing trees. Thereafter, a backhoe was employed to mechanically scrape off the remainder of the topsoil until the feature level was reached at a depth of 25 cm below the original surface. Archaeological materials were collected during the mechanical removal of overburden. Next, the surface was carefully scraped with shovels to expose the variation in soil color across the surface of the site. Soil texture and color were most important for identifying features. Features were labeled and mapped using a total station. Finally, the features were sectioned and drawn; depth, width, and soil texture of all natural and anthropogenic features were recorded. The cliff side was excavated to a depth of 30 cm in units of 2×2 m. The archaeological material was sorted from the excavated soils by hand as the soil was too heavy for sifting.

The relatively low density of features and the high percentage of features assigned to potential houses and ancillary structures suggested at first a rather short period of occupation of the settlement (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012; Hofman, Hoogland, and Roux Citation2015). Radiocarbon samples from two of the postholes provided dates between cal. AD 1445 and 1650 (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012, Citation2018). Due to the fluctuations of radioactive carbon content in the atmosphere the calibrated dates are spread over a span of time between the beginning of the second half of the fifteenth century and the end of the second half of the seventeenth century (). When the datable archaeological materials such as majolica, faience beads, and glass beads are taken into consideration, the time frame narrows to between AD 1550 and AD 1625.

Table 1. Radiocarbon dates of two postholes at the Argyle site.

The radiocarbon dates of Argyle fall into the same range as the 16 dates provided for the contemporaneous Cayo site of La Poterie on the neighboring island of Grenada (Hofman et al. Citation2019).

Of the 310 posthole features, 302 were assigned to the sixteenth to early seventeenth-century occupation and eight to a colonial period tobacco shed dating to the end of the eighteenth century. A total of 102 posthole features could be securely attributed to 11 structures, two large oval and nine smaller round-to-oval structures (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012). In all, 12 small and 26 large posts were assigned to the two oval structures. The larger of the two oval structures encompassed seven smaller posthole features with a depth of 15–25 cm and 14 larger postholes with a depth of 35–50 cm. Four posts along each long side of the floor plan were aligned, and three posts formed each short end of the structure, aligned with the posts on the opposite end. The distance between the posts was 2.2–2.3 or 3.25 m, and the width between each pair was 4 m. Thus, the floor plan of this main structure measured 11.8×4 m between the large posts and 16×7 m between the small posts.

Nine small round-to-oval houses with sizes between 4.5×5 m and 6×8 m were dispersed in the habitation area, encircling a plaza. Each of these structures was comprised by a circle or ellipse of 6–13 posts. One of these round structures yielded, next to a post, a large eared-stone axe at a depth of 20 cm. This has been interpreted as a ritual deposit related to the house (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012). Additionally, 11 posthole features were documented as belonging to two rectangular structures. In all, 200 features cannot be assigned to any particular structure in the field, but are thought to belong to a set of ancillary structures located between the houses (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012, Citation2018; Hofman, Hoogland, and Roux Citation2015, Citation2019).

Three burial pits were identified in two of the smaller round houses, suggesting that the deceased were buried under the house floors. Due to the high acidity of the clayey soil, bone is not well preserved, but two of the three burial pits still contained the enamel tooth crowns of the deceased individuals. The practice of burying the dead under house floors has been recorded as a common practice at many pre-colonial sites in the Lesser Antilles (e.g. Hofman and Hoogland Citation2011; Hoogland Citation1996; Hoogland and Hofman Citation1999; Bel and Romon Citation2010).

Few cultural remains were found in the area of the houses. Neither shell nor faunal remains are preserved, which may be due to the high acidity of the soil. Most of the recovered Cayo ceramics and lithic materials as well as the associated sixteenth to early seventeenth-century European artifacts were found in the profile exposed in the eroded cliff at the seafront.

Juxtaposing Archaeology and Ethnohistory

An Ethnographic Reading of the Ethnohistoric Sources on Island Carib/Kalinago

Until recently, the main ideas about what Island Carib or Kalinago houses and villages would have looked like were based exclusively on ethnohistoric accounts, because archaeological evidence was absent. When reviewing the early historic documents, it becomes clear that the various chroniclers documented a variety of Carib terms to describe settlement layout and house construction (Hofman, Hoogland, and Roux Citation2015). Here, we discuss predominantly the descriptions given by Father Raymond Breton in his dictionaries “caraibe-françois” and “françois-caraibe,” published in 1665 and 1666 (Breton Citation1999) respectively, and those by the contemporaneous French chroniclers Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre (Citation1654) and the Anonyme de Carpentras (Citation2002). For cross-reference, the French terms are translated into English in the text while the original French texts are provided in footnotes.

The Island Carib settlement or IcábanumFootnote1

When describing Island Carib or Kalinago villages, the chroniclers mention hamlets or single households dispersed across the landscape. Blondel’s map of 1666 shows the Carib settlements on the Island of Grenada located primarily in the northern and eastern parts of the island. Breton mentions that the Indigenous settlements were usually located close to the sea on the rugged windward or Atlantic sides of the islands (Breton Citation1999, 140) that offered defensive sites for their settlements. They were usually located close to a stream, where the inhabitants washed and took potable water (Breton Citation1999, 140). The immediate relationship between village and sea becomes evident from the terms huéitinocouFootnote2 and ineroubacálicou,Footnote3 which both mean “villager” and “crew member” (Breton Citation1999, 121, 151). When constructing a settlement, the Island Carib did not cut many trees, as a result of which the Europeans could not detect it easily. The Island Carib icháliFootnote4 or “gardens” were situated at a walking distance of up to one hour from the villages.Footnote5 Here, manioc, sweet potatoes, and other food crops were cultivated, while utilitarian plants and fruit trees were planted in small kitchen gardens near the houses.

The village had space for just one táboüiFootnote6 or ínnobonêFootnote7 (men’s house) and a few small family houses around a circular plaza (Breton Citation1999, 152, 239). The men’s house was used by the men to drink, rest, meet, and receive guests, and the unmarried men used to sleep here. A large táboüi described by Breton (Citation1999, 239) measured 19.5×6.5 m and had four small doors, each 1.3 m high, diametrically placed in the middle of the long walls and in the short ends of the building.

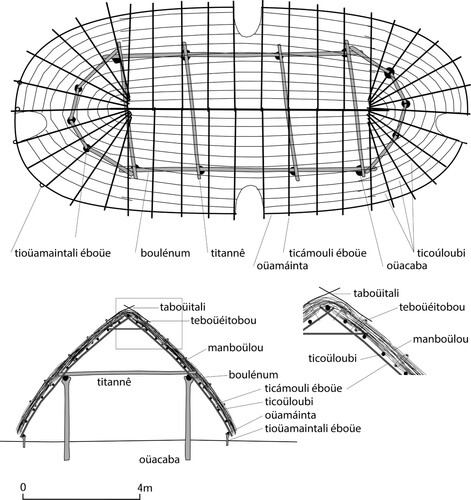

Breton recounts in detail the construction elements of this men’s house (). The forked posts (oüaccabouFootnote8) were approximately 1.8–2 m high, buried 65–95 cm into the soil, and set about 4 m from each other.Footnote9 Hard wood like guaiac (Guaiacum officinale [L.]) was preferred for use as posts as it is extremely resistant to termites, wood lice, and wood rot. Lengthwise, the main posts were connected by two top plates or headers (boulénumFootnote10) and these were cross-connected by 3.0 or 3.20 m-long tie beams (titannêFootnote11) (Breton Citation1999, 239). Breton mentions aócoma (Quercus spp.) as the preferred timber for good house construction (Citation1999, 123). According to Breton, it is the native oak and the French called it acornas (indet.). The first roof batten (oüamáintaFootnote12) was tied to small forked posts (tioüamaintali éboüeFootnote13) and formed the outline of the roof one or two feet above the ground. The rafters (ticámouli éboüeFootnote14) were fixed on the lower batten, resting in notches in the top plates and connected pairwise at the roof-ridge. A ridgepole was laid on the rafters and tied with lianas or vines (alloúgoutiFootnote15) or strips of bark (oüágneuFootnote16) of mahot (Hibiscus elatus [Sw.]). Roof battens (ticoúloubiFootnote17) (Gynerium sagittatum [Aubl]) provided the construction strength lengthwise and formed the frame of the roof covering. The roof was thatched with heads of a reed known as roseau (manboülouFootnote18) with the stems folded in half over the roof battens. The leaves functioned outside as roof cover and the stem inside served to fix the thatching. The thatching was cured by split stems of the roseau (teboüéitobouFootnote19), half placed lengthwise on the roof and the other half inside. Both halves were bound together with strips of mahot bark. Finally, the top of the roof was secured by pairs of sticks (taboüitaliFootnote20) tied together at the outside and fixed to the rafters at the inside of the roof. They served to hold the upper teboüéitobou tight to the rafters in such a way that the upper layer of roseau could not be lifted by the wind.

Figure 3. Top view and cross-sections of the reconstructed Island Carib or Kalinago táboüi (men’s house). The reconstruction is based on the archaeological floor plan at Argyle and the description of the building elements by Breton (Citation1999). (Drawing by Menno L.P. Hoogland).

The táboüi described by Breton had a row of beams for hanging a series of “cotton beds” or hammocks at a height of around 2 m. There was space for approximately 100–120 hammocks (Breton Citation1999, 239). The mánna,Footnote21 or small round houses for the individual households, were spread around this central building (Breton Citation1999, 176). There was only one opening in the mánna, a small one approximately 1.20 m high.Footnote22 The house, according to Breton, was not divided into different quarters (Breton Citation1999, 176).

The acaonagleFootnote23 or bouellélebouFootnote24 was the plaza in front of the houses. The various households had the duty to keep clean the part of this plaza in front of their houses (Breton Citation1999, 6, 45). This practice is reflected by the expression baráboucae píembouFootnote25 which means “take your food remains away” (Breton Citation1999, 151). The trash had to be removed, because it would attract chícke or sand fleas (Tunga penetrans [L.]). The cooking hearth consisted of three stones, manbácha,Footnote26 supporting a cooking pot which was placed on the fire lit between these three stones. The boucan (aríbeletFootnote27) was a wooden rack, consisting of four forked wooden sticks on which thin straight branches had been placed to roast meat (Breton Citation1999, 28).

Among the Island Carib or Kalinago, the deceased were buried in the dwellings under the house floors. After depositing the deceased person into a grave, wrapped in their own hammock, a huge fire was lit and all the elders, men and women, crouched down on their knees in a circle around the fire. They dug a round pit almost 1 m deep inside the house for the corpse. The burial pit was sometimes covered by a reed mat or planks and occasionally ceramic vessels were buried upside-down over the head. When the burial was outside the house, a small hut or house was built over it, for they would never leave the dead without a cover (Breton Citation1978, II:80).

Household goods consisted for the most part of perishable materials, such as plant fibers for basketry, reeds, wooden mortars, cotton hammocks, and needles made from fish bone or other bone. Only a small portion was made of non-perishable goods such as clay, stone, and bone. Cotton was used to make hammocks (acat, báti, or ébou, or fem. ekêraFootnote28) and arm and leg bands. The latter were sometimes decorated with small, white glass beads (Breton Citation1978, II:61–62; Du Tertre Citation1654, 436). The hammocks were woven in a frame hanging from the beams in the house.

Comparing the Archaeological Record with the Ethnoarchaeological Case Studies

Maillard, an Abandoned Palikur Village in French Guiana

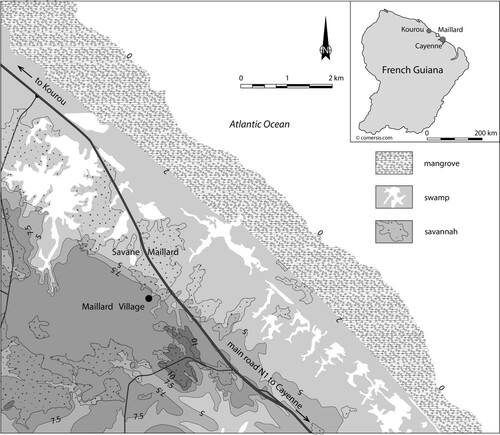

The village of Maillard was located in a seasonally flooded savanna on the coastal plain in French Guiana, approximately 2 km south of the seashore (). The settlement was visited and analyzed a few weeks after its abandonment by its inhabitants in 1990 (Rostain Citation1994, Citation2017). Several visits were made during the 20 years thereafter to track the condition of remains and features. The village occupied a low sandy bar approximately oriented north–south. It stretched over 50 m from north to south and 38 m from east to west.

Figure 4. Geographical map of the environment of Maillard village, Commune de Macouria, French Guiana. (Drawing by Menno L.P. Hoogland after regional map by the National Geographical Institute IGN).

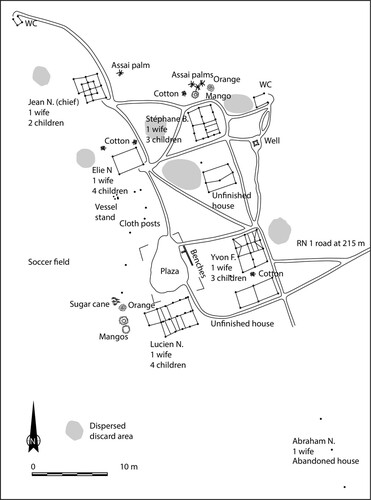

The village had a roughly rectangular shape with houses built in two parallel rows. Two north–south paths ran alongside these rows of houses, while perpendicular paths connected them. Another path led to the National Road about 250 m north of the settlement. Collective latrines were located north and south of the village, and a well had been dug not far from the first latrine. A large central plaza had been cleared in the eastern half of the settlement. Six refuse deposits (middens) were distributed near the houses. Seven houses were identified during the first period of fieldwork (). Planted trees were recorded as well.

There were few types of structures, mainly the houses, restrooms, and one well. There was no evidence of communal dwellings, separate kitchens, or meat-drying racks, which generally are common in Indigenous villages in this region. Dispersed wooden posts were present in the ground in several places, some positioned in pairs to support a line for drying clothes. In sum, a relatively low variety of structures was found. At the time of abandonment in 1990, 28 people – 12 adults and 16 children – were living in the village of Maillard as their primary residence. The village layout covered an area of almost 2,000 m2.

Five points of information, mainly obtained through ethnographic investigations, are crucial for a good reading of the ethnoarchaeological record. First, the period of occupation was short. The village was inhabited for only four years. The village chief was the first person to live in the settlement. He came from the Lower Oyapock River about 100 km to the east, arriving in 1986. His brothers joined him in the same year, traveling by canoe across the sea and transporting a collectively-owned ceremonial wooden bench in the shape of an anaconda about 3.8 m long. Second, a structure cannot be built in a few days and used immediately. In several cases, buildings were started, yet remained unfinished. Third, the abandonment occurred gradually over time. The inhabitants of the easternmost house, positioned slightly away from the other houses, had left long before the other households. Most of the residents moved out of the village in May 1990, when the land owner banished the community. Three people stayed in one of the houses until the month of August before moving. Consequently, the abandonment of the hamlet was spread over months. However, the use of this space continued for several more months after abandonment, because the former inhabitants sometimes visited their former dwellings to collect useful materials, such as household goods, wooden posts, and fruit from trees planted there. For example, during one of our trips to conduct interviews at the site, one man took advantage of the opportunity to bring large sheets of metal roofing from Maillard to his new village. Fourth, village spatial organization does not always conform to the general pattern observed in comparable settlements. For instance, it is common in the Guianas that the chief’s house is one of the largest ones and is located in front of the central plaza (Rivière Citation1984; Roth Citation1924). However, in Maillard, the chief’s house was relatively small and located at the western periphery of the village, far from the plaza. The fifth and last important point concerns the discarded artifacts and refuse found in the settlement. The Maillard site fundamentally differs from pre-colonial villages in terms of the raw materials, relative frequencies, spatial distribution, and preservation of materials. Most of the materials at the Maillard site were not locally made. Most of the refuse evident on the ground surface was broken, presumably discarded, industrially manufactured, and rapidly deteriorating, and often European in origin. Metal objects and glass containers dominated the assemblage, along with cardboard food packaging, earthenware, and plastic bottles. Glass and metal fragments that were dangerous for people walking barefoot because of the risk of their feet being cut painfully were concentrated in middens. For that reason, according to former residents, it was necessary to regularly clean up the outdoor social spaces and concentrate trash in the dump areas to avoid injury to their feet while walking through the village.

Extrapolating the time over centuries, the Maillard village would have left few clues to its existence, except for postholes from the houses and some refuse areas with meager remains (, top). No ceremonial life or specialized activities would be evident from the palimpsest of features that we recorded there.

Amotopo, a Present-day Trio Village in Suriname

Amotopo is one of several small Trio villages of the Surinamese southern interior. It was founded in 2001. Trio is a language that is part of the Cariban language stock. In 2007 and 2008 ethnoarchaeological fieldwork was conducted by Mans (Citation2011) in this village to record material dimensions relevant to archaeological studies. While Rostain’s study at Maillard focused on village abandonment and development of the archaeological record over 20 years, Mans’ study in Amotopo was more concerned with documenting and understanding the systemic context of a young village from a synchronic perspective.

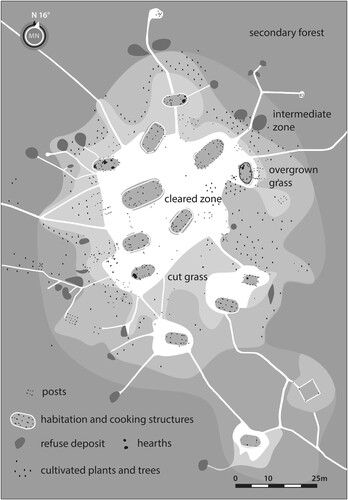

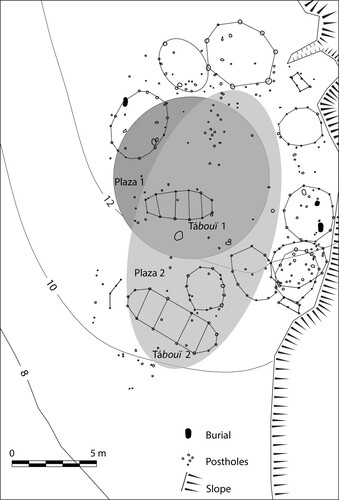

Described synchronically (Mans Citation2012, 83), the Amotopo village layout includes 14 large structures and numerous smaller ones, surrounded by small refuse scatters and heaps. The total area encompassing these features is 0.81 ha (Mans Citation2012, 211). This area was originally established when the first garden was cleared to distinguish it from the surrounding forest. The village center consists of the large cleared area where most of the larger structures are located. Moving away from the village, one passes through a series of spaces that characterize people’s domestication of the forest near the village, from a weeded clearing, to grassy areas that are partially cut or becoming overgrown, to an intermediate zone of gardens with cultivated plants and trees, to secondary forest areas overgrown with larger shrubs and trees, then to older-growth forest ().

Gardens belonging to a specific household are located outside the grassy zone behind the house and cooking structures (see ). A wide variety of plants and trees are cultivated in household gardens, including chili peppers, corn, pineapple, papaya, cashew, lime, herbs, cotton, pigment-providing plants, and calabash (Mans Citation2012, 233 and Figure 3.31). Beyond this area, in older large gardens, many varieties of manioc and banana are cultivated. Next, the newer manioc gardens are located in the older-growth forest within about 800 m of the village.

Following archaeological conventions, we could say that this village site consists of refuse deposits, hearths, and clusters of postholes, some of which are surrounded by ditches. Reasoning from an archaeological plan view, the 23 refuse deposits delimit the outer boundary of the village. These refuse deposits, mainly consisting of perishable subsistence remains, were in the middle of the toss zone surrounding the village. The most durable remains of artifacts that could no longer be reused were tossed from the area of habitation and cooking structures into the intermediate area of cultivated plants and trees and beyond (see ). It is therefore likely that, from an archaeological perspective, the total refuse area would be encountered as a band surrounding the settlement. Most other archaeological features would be found within this ring of refuse. These features would all be associated spatially with the structures, including 11 hearths, 15 ditches, and 639 postholes and stakeholesFootnote29.

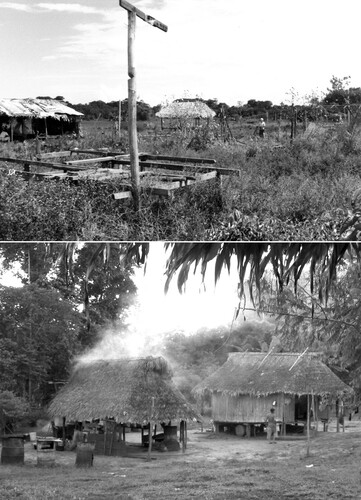

One can differentiate the structures in the village that would probably leave an archaeological trace in the soil from those that would be less visible archaeologically. A hearth and a ditch are supportive evidence to identify a structure, although its main diagnostic evidence is a cluster of postholes. A structure was defined as any cluster of three or more posts or stakes that served a common purpose. The ones that would be mostly visible archaeologically are the structures that have excavated foundations where posts have been placed. Amotopo had four such types of structures, namely the two communal structures, seven habitation structures, six cooking structures with at least one hearth, and two storage structures (, bottom). Additionally, 25 smaller structures without excavated foundations were recorded, including racks for drying meat, dog pens on platform floors, and lavatories.

The construction of a Trio house was observed and documented in detail by Mans (Citation2012, 47–57). The construction starts by digging a posthole about one-arm deep (about 0.6m) at each corner of the layout for the main structure. The four corner posts are about 2.4 m tall and support the four crossbeams that constitute the lower frame of the roof (Mans Citation2012, Figures 3.7 and 3.10). The corner posts are made of durable wakapu wood (Vouacapoua Americana [Teunissen, Noordam, and van Troon Citation2003]). The top of each post is not forked, but notched in order to seat the first two crossbeams securely. The first two crossbeams are placed in the notches of the posts to span the front and the back of the structure, then securely fastened with liana to the posts. The ends of these beams extend beyond the outline of the structure. Next, the other two crossbeams are placed on top of the protruding ends to span the long sides of the structure, then fastened with liana to the corner posts and supporting beams. Less durable wood species (Ephedanthus guianensis [Hoffman Citation2009] and Duguetia spp.) are used for the crossbeams. Then, two post holes about 1.0 m deep are dug along the central axis of the structure for the posts that will support the roof ridge beam. These posts are made from very durable wakapu wood, also. Additional beams placed are placed lengthwise, including a roof ridge beam, to strengthen the house. The frame of the house is finished by constructing semicircular roof extensions at both short ends of the building and by placing light poles to serve as rafters for supporting the roof covering (Mans Citation2012, 57–59, 62–65). Although there are many similarities between Island Carib and Trio houses, they differ in that Trio houses have a rectangular lay-out with semicircular extensions on both short ends, an elevated platform floor, and a roof covered by 2-m-long mats made of plaited palm leaves.

Although the map of Amotopo () suggests that the houses and other structures were used synchronously, the layout of the village developed and changed over the seven years of its existence, and there was continuous movement of people in and out of the village. Over the seven years, a total of 24 residents (18 adults and 6 children) lived there, mostly belonging to one extended family, leaving a palimpsest of traces. By 2008, during the last fieldwork season, there were only 17 residents (11 adults and 6 children) living there, and some houses were vacant. The village leader was residing in one of the communal structures, in one of its extensions, the rest being maintained as communal space for visitors and community gatherings. Another large structure had been built by the village leader’s step-brother, who after several years in Amotopo decided to move 5 km away with his family to found his own village. The structure he left behind might be interpreted archaeologically as a communal house based on its size, which is nearly double the floor area of other houses, and construction, which utilized three instead of two posts to support the roof ridge beam. These examples show how the function of a structure may change across its life history and differ from normative expectations (Mans Citation2012, 213).

Discussion: Constructing from the Invisible

The main objective of this study was to compare archaeological, ethnohistoric, and ethnoarchaeological evidence to conceptualize Island Carib or Kalinago village layout and dynamics in the late pre-colonial to early colonial insular Caribbean. The archaeological data were recovered during extensive rescue excavations at the site of Argyle, Saint Vincent in the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles. Destruction of the site was threathened by the construction of an international airport in the same location. The ethnohistoric information used was extracted from early seventeenth-century European sources. The ethnoarchaeological case studies were done in two Indigenous villages, Maillard and Amotopo, in the Tropical Lowlands of mainland South America. It is important to note that the ethnoarchaeological studies were conducted as independent investigations prior to the excavations at Argyle and not for the purpose of interpreting or conceptualizing archaeological data from Argyle. The researchers directing the Argyle excavations were familiar, though, with the ethnohistoric sources on the Island Carib of the Windward Islands. Therefore, the archaeological research was informed by a critical ethnographic reading of the ethnohistoric sources for the first interpretation of the settlement layout.

In his Dictionnaire caraïbe-françois, Breton (Citation1999) mentions about 10 building elements of the táboüi, some described in great detail with measurements and names of trees, reed, and liana, some less detailed. This information permitted the researchers to make a very reliable interpretation of the two oval floorplans at Argyle () as Breton’s description of a communal or men’s house (táboüi) closely matches the archaeological floorplans. The táboüi described by Breton, however, had much larger dimensions (Breton Citation1999, 239). The Argyle táboüis had only four pairs of posts along each long side of the structure, requiring four tie beams. This divided the house into five compartments, of which three compartments would have been suitable for suspending hammocks. Following Breton, this táboüi could provide space for some 15–20 men.

Figure 8. Interpretation of the Argyle settlement, Saint Vincent, based on archaeological data and ethnohistorical information. (Drawing by Menno L.P. Hoogland).

The French sources (Breton Citation1999, 45, 140; Du Tertre Citation1654, 437–438) recount that there was space for only one táboüi in a village; thus, it seems plausible that the two men’s houses in Argyle represent two phases of occupation. In each phase the táboüi was surrounded by family houses (mánna) arranged around the village plaza (acaonagle or bouellélebou). The ethnohistoric data led to the hypothesis that two plaza areas existed, each with a táboüi, (), but these were related to two successive phases of occupation (Hofman and Hoogland Citation2012, Citation2018; Hofman, Hoogland, and Roux Citation2015). This process can be interpreted as a gradual rearrangement of the village or a reoccupation after abandonment (DeBoer, Kintigh, and Rostoker Citation1996). The smaller men’s house may have represented the initial phase of the village and the larger one a second phase when the population of the settlement had grown or the táboüi had to be rebuilt. The larger men’s house was built more to the south and the plaza was reorganized. It measured 15×25 m and was the southernmost structure around this open space.

Breton describes the táboüi as a gendered space where young unmarried men spent the night, men performed their everyday activities and discussed politics, and guests were entertained. The women entered the táboüi only to serve food to the men (Breton, 239). The seventeenth-century European chroniclers also mention ancillary structures comparable to the ones described in Amotopo.

The two uninterpreted rectangular structures at Argyle possibly represent drying racks for smoking meat, barbacoas for grilling meat, poles for suspending hammocks, or dog pens, for example. According to the ethnohistoric sources, the deceased were buried under the floors of the houses. This was also the case at Argyle. The absence of cultural remains in the area of the dwellings, which was initially attributed to the mechanical scraping during the archaeological rescue work, also may be the result of the continuous clean-up activities around the houses as described by the chroniclers and observed ethnoarchaeologically. The cultural remains that were found eroding from the cliff at the seafront may represent garbage that was thrown behind the houses, forming heaps or an oval-shaped refuse scatter around the village.

This preliminary interpretation has led to the creation of a model of the village, which is currently exhibited in the National Library at Kingstown, Saint Vincent, and to the request of the government of Saint Vincent and The Grenadines to erect a live experimental reconstruction of the Cayo village at the location of the excavations at Argyle ( [Hofman and Hoogland Citation2016; Hofman et al. Citation2020c). Both initiatives have been important for the Kalinago and Garifuna communities in Saint Vincent and Dominica for whom the construction at Argyle may represent a place of memory.

Figure 9. Experimental reconstruction of five houses in the Cayo village of Argyle, Saint Vincent. (Photo by Menno L.P. Hoogland, 2017).

When comparing the archaeological data, the ethnohistoric sources, and the two ethnoarchaeological case studies, three interesting considerations come to the fore that must be considered to understand village layout and dynamics in the archaeological record of the insular Caribbean.

First, the reality of Indigenous ways of life in this region is fundamentally distinguished by intense and continuous fission and fusion, involving movements of people going elsewhere to live or visit. The number of residents may vary in a village over the course of its occupation and even seasonally. Villages are temporarily vacated for journeys of weeks or even months. This is common today and may have happened in the past. This may have implications as to the life history, abandonment, or reuse of a village and individual structures. Such mobility can involve single individuals or whole families. The reasons for leaving the village are diverse and may include specific tasks, contract work, trade, participation at events in other communities, and funerary feasts, among others. These periods of absence by the inhabitants do not leave visible traces in the soil, except by contrast with the houses and household compounds that have been maintained, built and rebuilt, over longer durations.

Second, the often-dense palimpsest of features and structures encountered at a site needs to be taken into account when considering village dynamics. Maillard and Amotopo had continuous but dynamic settlement histories resulting in a number of overlapping features and structures even over a short period of time. There were many displacements and other movements of people from the villages that would not be visible in the archaeological record. In the village of Maillard one of the main pitfalls in interpreting the features and reconstructing the house plans was the difficulty in precisely defining the process behind the feature formation (Rostain Citation2017). For instance, it was difficult to distinguish houses that had been completely built from unfinished ones, because most of their features were similar. Contrary to normative expectations, the house of the chief was not the largest one in the village, but instead rather small in size and not located in its center. At Amotopo, a palimpsest of postholes and structures was documented accounting for several specialized structures. It became evident, however, that not all houses were occupied simultaneously and permanently. Both villages showed a complex history of house building, with a succession of dwellings, changes of location, abandonment of structures, and changes of function.

Third, the diversity of refuse systems and disposal behavior needs to be considered when interpreting the village layout. The continuous sweeping of the ground in the open space surrounding the houses and plaza is mentioned for Maillard, Amotopo, and Island Carib villages. Important differences can be seen, though, in the location of middens, the density of refuse, and the period of occupation. These variations have a direct impact on the interpretation of the archaeological remains. For instance, in Maillard each refuse area was directly associated with a house, while in Amotopo the main refuse area was behind the collective cooking structure and the tossing areas were in the periphery outside the settlement. Consequently, the archaeological palimpsests are different between familial and collective middens.

Concluding Remarks

The Argyle archaeological data benefited from a critical ethnographical reading of the ethnohistorical information on structures and village layout. The ethnoarchaeological case studies helped to conceptualize subtle changes in the use and transformation of the structures that were difficult to grasp in the field and from the poor radiometric material that was preserved. The palimpsest of posts at Argyle indeed suggests that several construction phases were present, but the contemporaneous use or temporary abandonment of the structures as seen in the ethnoarchaeological cases is difficult to assess from the archaeological data alone.

The recovery of most artifacts from the cliff area suggests that the refuse deposits were located behind the houses, although this interpretation is limited by the damage done to the site by development activities prior to the excavations. Future work is needed to understand the distinction between family or community-based trash disposal and the relationship between length of occupation and the density and distribution of discarded materials.

Combining these multi-disciplinary data has shown to be fundamental for a better understanding and conceptualization of past settlement spaces and village dynamics at Argyle. This archaeological site appears to have been a village with two phases of occupation rather than one phase of occupation with two men’s houses, two plazas, and a number of round dwellings as well as ancillary structures attributable to one of the two phases, and potential toss zones behind the houses on the cliffside facing the Atlantic Ocean. The early European documentary evidence of the Island Carib villages has been very useful here to disentangle the ephemeral remains of a contemporaneous village, especially given the very detailed information of house construction, building materials, and use of structures. Of the 302 postholes assigned to the late sixteenth to early seventeenth-century occupation, 102 could be assigned definitively to structures, a relative frequency that is high but not exceptional when compared to other archaeological sites in the region (Hofman et al. Citation2020c; Hoogland Citation1996; Samson Citation2010). A palimpsest of postholes can be difficult to document and interpret, but these have been important sources of evidence for the interpretation of settlements (see also Greaves Citation2006; Politis Citation2002; Siegel Citation1990b) with clear relevance to matters of population size, social relationships, activity areas, cross-cultural variation, site organization, mobility, duration and density of occupation, Indigenous responses to settler colonialism, and human-environment interactions. The ethnoarchaeological studies at Maillard and Amotopo have both shown dynamic and continuous settlement resulting in a palimpsest of features and structures even over a short period of time. The dark circles and stains in the soil reflect the construction, repair, rebuilding, abandonment, and reuse of structures which are only partially grasped through archaeological assessment, but are better understood when conceptualizing the past through the present.

Acknowledgments

The project at Argyle has been facilitated by the National Trust of Saint Vincent and The Grenadines and the Saint Vincent and The Grenadines International Airport Development Company Ltd. In this context we particularly would like to acknowledge Mrs. Kathy Martin and Dr. Henry Petitjean Roget. The project included researchers, students, and members of the Kalinago and Garifuna communities of Saint Vincent and Dominica. The data on Amotopo were collected by Jimmy Mans during his PhD research in 2007 and 2008. Stéphen Rostain did research in the Maillard village in 1990 when he was contracted by ORSTOM (now IRD, the French Institute of Research for Development). This article is the result of a collaborative effort that was initiated during the 3-month’s stay of Dr. Rostain at the Faculty of Archaeology of Leiden University in Spring 2017. We acknowledge Emma de Mooij, Arie Boomert, Greg Tonks, and David Tonks for their editorial help and Brenda Bowser and all internal and external reviewers for their useful comments which considerably improved the readability of this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Corinne L. Hofman

Corinne L. Hofman is Professor of Caribbean Archaeology at the Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University, and Senior Researcher at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV/KNAW). Hofman’s research in the Caribbean is highly inter- and transdisciplinary and addresses issues such as mobility, exchange, inter- and transcultural dynamics, colonialism, and social adaptation to climate change. Her projects aim to contribute to historical awareness, valorization of archaeological heritage, and knowledge exchange in the Caribbean. Recent awards include the Dutch Research Council (NWO) Spinoza prize (2014), the European Research Council (ERC) Synergy Grant for the Nexus 1492 project (2013–2019). Currently, she is one of the Principal Investigators in the NWO project Island(er)s at the Helm (2021–2026).

Stéphen Rostain

Stéphen Rostain is senior researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in France. He received his Ph.D. in archaeology at the University of Pantheon-Sorbonne in Paris in 1994. He has conducted archaeological and interdisciplinary projects in Aruba, the Guianas, and the Ecuadorian Amazon. His main focuses are landscape archaeology and constructed earthworks, historical ecology, iconography, technology of pre-Columbian artifacts, and ethnoarchaeology. Rostain has published more than 300 papers and books in English, Spanish, and French. He received the Grand Livre d'Archéologie book prize in 2020 and the Clio award for French projects in foreign countries in 2008.

Jimmy L.J.A. Mans

Jimmy Mans is a policy officer for the Dutch Research Council (NWO). From 2006 to 2017, he was a doctoral and postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Archaeology at Leiden University. Between 2013 and 2017 he was affiliated to the ERC-Synergy Nexus 1492 project and the Humanities in the European Research Area (HERA)-CARIB project. For three years he worked as a museum researcher of the Caribbean collections for the Dutch National Museum of Ethnology. His research interests include Indigenous histories of the Caribbean and the Guianas, contemporary and historical archaeologies, and collaborative museum and heritage projects.

Menno L.P. Hoogland

Menno L.P. Hoogland is a retired Associate Professor in the Faculty of Archaeology at Leiden University. For his Masters in Anthropology he conducted fieldwork in the Kalinago Territory in Dominica in 1984. In 1996 he obtained a PhD in Archaeology focusing on Amerindian settlement patterns on the island of Saba. His research interests are the lifeways and deathways of the pre-colonial and early colonial Amerindian societies. Menno was a senior researcher in the ERC-Synergy project Nexus 1492 between 2013 and 2019. Currently he works for the CaribTrails project at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV/KNAW).

Notes

1 The term Icábanum seems to have been borrowed from the French term cabane, cabaner. In the Dictionnaire françois-caraïbe, Breton gives two synonyms for habitation: aütê, fem. Obogne (Breton Citation1666, 199).

2 huéitinocou: concitoyens, habitants, mariniers d’un même carbet (Breton Citation1999, 121).

3 ineroubacálicou: habitant, marinier d’un carbet (Breton Citation1999, 151).

4 icháli: jardin. “Les Sauvages n’usent point de nos légumes, et cependant ils ont des jardins qui leur servent de champs et de vignes, d’autant qu’ils en tirent leur pain et leur vin, leurs maniocs et leurs patates; c’est ce que nous appelons nos places, nos habitations, non pas chez les Sauvages, dont l’habitation et le carbet sont séparés des jardins, un trou ici, un autre là, à la différence des Français dont tous les jardins et habitations se suivent; je ne les saurais mieux représenter que par les bastides de Marseille, sauf qu’elles sont bien plus larges et plus longues, les bâtiments sont sur les places, n‘y ayant encore aux îles que des commencements de bourgs où les habitants n’ont pas grandes attaches, parce qu’ils ont la meilleure partie de ce qui leur est nécessaire, outre qu’ils sont sur leur travail, et peuvent avoir l’œil sur leurs gens” (Breton Citation1999, 141).

5 “[Certains jardins sont] au-dessus des montagnes éloignés quelquefois de près de deux lieues [3.265 km each] de l’habitation de ces Indiens’, un capitaine qui avait un jardin environ 500 pas proche de notre habitation, qui était chose rare d’en être si prêt” (Anonyme de Carpentras Citation2002, 140, 156–157).

6 “[… itáboüiri …] Carbet qui est la salle, la halle, l’ouvroir, le r��servoir, le réfectoire, le dortoir, et la case commune des Sauvages. Il est à peu près comme un berceau en ovale sur sa hauteur, et longueur qui a 60 pieds sur vingt de largeur, bâti d'une manière rustique, mais aussi délicatement et à profit que l'on se le puisse imaginer; on y entre par quatre trous diamétralement opposés sur le centre de l’ovale qui n’ont que quatre pieds de hauteur sans autres portes, ni fenêtres, sans chevilles, ni clous, sans étages, ni chambres et sans autres séparations ni embarras qui empêchent de s’y promener douze personnes de front; seulement à la hauteur de sept pieds il y a des travers sur dix de longueur pour y suspendre cent ou 120 lits de coton où ils reposent paisiblement avec une intelligence très parfaite sans querelle et sans bruit, les femmes n'y entrant que rarement et encore pour les y servir” (Breton Citation1999, 239).

7 Ínnobonê: Carbet (Breton Citation1999, 152).

8 “oüacaba, fourche” (Breton Citation1999, 201).

9 “Il faut savoir que toutes leurs cabanes sont appuyées sur des piliers plus hauts qu’un grand homme qu’ils nomment ouaccabou” (Anonyme de Carpentras Citation2002, 184); “[Le carbet] est composé de grandes fourches hautes de dix-huit ou vingt pieds, plantées en terre de douze en douze pied” (Du Tertre Citation1654, 437).

10 “boulénum, deux grandes pièces de bois posées qui vont le long de la couverture en dedans, les poutres en travers sont attachées à celles-ci, et le faix de la case posé dans les entailles, qui sont faites sur celles-ci, elles supportent tout le bâtiment, en sorte que n’y ayant point de colonnes, ou fourches au milieu, on s’y peut promener comme dans une halle, sans empechement, huit à dix de front” (Breton Citation1999, 48).

11 “titannê, un travers de case” (Breton Citation1999, 233).

12 “oüamáinta, c’est la sablière qui est en bas sur laquelle on attache les chevrons qui posent à terre, sont aussi des paquets de gaules” (Breton Citation1999, 203).

13 “tioüamaíntali éboüe, sont les petites fourches qui les [oüamáinta] portent” (Breton Citation1999, 203).

14 “ticámouli éboüe, chevron” (Breton Citation1999, 231).

15 “Alloúgouti, f. chichálouca. Les Sauvages n’ont point d’autres chevilles dans leurs bâtiments que ces lianes qui durent autant que le bois sans se pourrir” (Breton Citation1999, 131).

16 “oüágneu, mahot. Cet arbre ici pour être fréquent n’est pas moins utile, il est tout tordu et sans lui nous ne saurions rien faire de droit, si on veut bien monter un rôle de pétun, il faut du Mahot, si on veut attacher des roseaux, il faut du Mahot, s’il faut lier quelque chose, c’est avec du Mahot ; les femmes Caraïbes en lèvent des larges et longues aiguillettes qu’elles posent sur leur front, et entortillent des deux côtés de leur catoli pour les porter; les hommes s’en servent au lieu d’étoupe pour calfater leurs pirogues; les Nègres sont bien mollement quand ils ont du Mahot pour faire une Cabane. Enfin je ne sais ce qu’on ferait sans Mahot” (Breton Citation1999, 128–129).

17 “ticoúloubi, sont les perches qui sont rangées le long des pirogues qui soutiennent les planches sur lesquelles on s’assoit, sont encore celles qui servent de ventrières dans les carbets” (Breton Citation1999, 231).

18 “manboülou, roseau. De sa tête on couvre les cases, les Sauvages en font sécher et les brûlent, puis ils frottent de la cendre et en noircissent ceux qui ont les pians. Les bâtons ou tuyaux servent à latter les toits, ou à pallissader et fermer les cases” (Breton Citation1999, 175).

19 “teboüéitobou, c’est un roseau fendu en deux, dont une partie est dessous la couverture, et l’autre dessus; on les saisit avec des lianes, ou du mahot ce qui empêche que le vent n’enlève la couverture” (Breton Citation1999, 99).

20 “taboüitali, c'est un baston qu’on fait passer dans le faîte qui tient les roseaux fendus qui arrêtent le faîte de la case, ou du carbet, ils sont appellés teboüitobou” (Breton Citation1999, 222).

21 “Mánna: Maison. Les Sauvages ont des chaumines bâties à peu près comme celles de nos villageois, à la réserve que la couverture est de têtes de roseaux ou de feuilles de Palmistes, qui vont jusques à terre; qu’elles sont en ovale, sans aucune fenêtre, il y a seulement un trou au lieu de porte par lequel on ne saurait entrer qu’en se baissant : le dedans n’est point embarrassé de poutres, ni de fourches qui soutiennent le logis, de chambres, d’antichambres, ni de plancher” (Breton Citation1999, 176).

22 “Le trou par lequel ils entrent qui est haut de deux à trois coudées” (Breton Citation1978, II, 68). During the 17th century, the coudée measured approximately 52.36 cm.

23 “Acaonagle: la cour, ou la place de devant le carbet” (Breton Citation1999, 6).

24 “Bouellélebou: c’est la cour, la place qui est entre le carbet et les cases; chacun nettoie devant la sienne et après le souper, ils s’assemblent et discourent autour du feu qu’ils y font (si la soirée est fraîche) jusqu’à ce qu’ils s’entredisent: Kichícoulama, allons-nous coucher, cependant ils ne se plaignent pas du serein le lendemain, ni n’en sont pas enrhumés” (Breton Citation1999, 45).

25 “Baráboucae píembou: va porter tes arêtes, tes pelures, et autres restes de table. Ils vont jeter cela au loin, parce que ces choses engendrent des chiques” (Breton Citation1999, 151).

26 “Manbácha: trépied, sont trois roches qui soutiennent le pot qu’on met sur le feu qui est au milieu de ces roches, c’est aussi le foyer” (Breton Citation1999, 174).

27 “Aríbelet: un boucan, sont quatre fourchettes plantées en terre, des bâtons dessus en travers et un feu à rôtir un bœuf. Voilà leur grille” (Breton Citation1999, 28).

28 “acat: lit de Sauvage” (Breton Citation1999, 6); “báti: lit de coton, un appentis, un ajoupa, une remise” (Breton Citation1999, 41); “ébou: lit” (Breton Citation1999, 97–98); “écra: lit” (Breton Citation1999, 100).

29 im the entire document posthole is one word, thuis shpuld be here also

References

- Agorsah, E. Kofi, John H. Atherton, Graham Connah, Candice L. Goucher, B. G. Halbar, Francois J. Kense, Arthur C. Lhemann, Roderick Mclntosh, Simon Ottenberg, P. L. Shinnie. 1985. “Archaeological Implications of Traditional House Construction Among the Nchumuru of Northern Ghana (and comments and reply).” Current Antropology 16 (1): 103–115.

- Anonyme de Carpentras. 2002. Un Flibustier Français dans la Mer des Antilles (1618–1620). Relation d’un Voyage Infortuné fait aux Indes Occidentales par le Capitaine Fleury avec la Description de Quelques Îles qu’on y Rencontre, Recueillie par l’un de Ceux de la Compagnie qui Fit le Voyage. Text presented by J.P. Moreau. Paris: Payot & Rivages.

- Barreto, Bruno de Souza. 2015. Diacronia e Cultura Material no Sítio Laranjal do Jari 01: um Assentamento Associado às Cerâmicas Jari e Koriabo, Baixo Rio Jari, sul do Amapá (670–1450 AD). Dissertação de Master, Universidade Federal de Sergipe.

- Bassi, Filippo Stampanoni. 2016. A Maloca Saracá: Uma Fronteira Cultural no Médio Amazonas pré-Colonial, Vista da Perspectiva de Uma Casa. Tese de Doutorado, Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, São Paulo.

- Basso, Ellen B. 1977. Carib-Speaking Indians: Culture, Society and Language. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Bel, Martijn van den, and Thomas Romon. 2010. “A Troumassoid Site at Trois-Rivières, Guadeloupe, FWI, Funerary Practices and House Patterns at La Pointe de Grande Anse.” Journal of Caribbean Archaeology 9: 1–17.

- Boomert, Arie. 1986. “The Cayo Complex of St. Vincent: Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Aspects of the Island Carib Problem.” Antropológica 66: 3–68.

- Boomert, Arie. 2016. The Indigenous Peoples of Trinidad and Tobago from the First Settlers until Today. Sidestone Press: Leiden.

- Bowser, Brenda J. 2000. “From Pottery to Politics: An Ethnoarchaeological Study of Political Factionalism, Ethnicity, and Domestic Pottery Style in the Ecuadorian Amazon.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 7 (3): 219–248.

- Bowser, Brenda J., and John Q. Patton. 2004. “Domestic Spaces as Public Places: An Ethnoarchaeological Case Study of Houses, Gender, and Politics in the Ecuadorian Amazon.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 11 (2): 157–181.

- Breton, Raymond. 1666. Dictionnaire François-Caraibe. Auxerre: Gilles Bouquet.

- Breton, Raymond. 1978. Relation de l’Île de la Guadeloupe. Basse-Terre: Société d’Histoire de la Guadeloupe.

- Breton, Raymond. 1999. Dictionnaire Caraïbe-Français (1665). Édition Sous la Responsabilité de Marina Besada Paisa. Paris: Éditions KARTHALA et IRD.

- Bright, Alistair J. 2011. Blood is Thicker than Water: Amerindian Intra- and Inter-insular Relationships and Social Organization in the pre-Colonial Windward Islands. Sidestone Press: Leiden.

- Buchli, Victor, and Gavin Lucas. 2001. “The Absent Present: Archaeologies of the Contemporary Past.” In Archaeologies of the Contemporary Past, edited by Victor Buchli, and Gavin Lucas, 3–18. London: Routledge.

- Caiuby Novaes, Sylvia, ed. 1983. Habitações Indigenas. Belém: Livraria Nobel. Sao Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo.

- Carlin, Eithne B. 2011. “Nested Identities in the Southern Guyana-Suriname Corner.” In Ethnicity in Ancient Amazonia: Reconstructing Past Identities from Archaeology, Linguistics, and Ethnohistory, edited by Alf Hornborg and Jonathan D. Hill, 225–236. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

- Carlin, Eithne B., and Jimmy J.L.A. Mans. 2015. “Movement Through Time in the Southern Guianas: Deconstructing the Amerindian Kaleidoscope.” In In and Out of Suriname: Language, Mobility & Identity, edited by Eithne B. Carlin, Isabelle Leglise, Bettina Migge, and Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat, 76–100. Leiden: Brill.

- Castilla-Beltrán, Alvaro, Henry Hooghiemstra, Menno L.P. Hoogland, Jaime R. Pagán-Jiménez, Bas van Geel, Michael H. Field, Maarten Prins, … Corinne L. Hofman. 2018. “Columbus’ Footprint in Hispaniola: A Paleoenvironmental Record of Indigenous and Colonial Impacts on the Landscape of the Central Cibao Valley, Northern Dominican Republic.” Anthropocene 22: 66–80.

- DeBoer, Warren R., Keith Kintigh, and Arthur G. Rostoker. 1996. “Ceramic Seriation and Site Reoccupation in Lowland South America.” Latin American Antiquity 7: 263–278.

- DeBoer, Warren R., and Donald W. Lathrap. 1979. “The Making and Breaking of Shipibo-Conibo Ceramics.” In Ethnoarchaeology: Implications of Ethnography for Archaeology, edited by Carol Kramer, 102–138. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Du Tertre, Jean-Baptiste. 1654. Histoire Générale des Îles de S. Christophe, de la Guadeloupe, de la Martinique, et Autres Dans L’Amerique. Paris: Jacques et Emmanuel Langlois.

- Fernandes, Daniel M., Kendra A. Sirak, Harald Ringbauer, Jakob Sedig, Nadin Rohland, … David Reich. 2021. “A Genetic History of the pre-Contact Caribbean.” Nature 590: 103–110.

- Fitzpatrick, Scott M. 2015. “The Pre-Columbian Caribbean: Colonization, Population Dispersal, and Island Adaptations.” PaleoAmerica 1 (4): 305–331.

- Friesem, David E., and Noa Lavi. 2017. “Foragers, Tropical Forests and the Formation of Archaeological Evidences: An Ethnoarchaeological View from South India.” Quaternary International 448: 117–128.

- Gosden, Chris, and Yvonne Marshall. 1999. “The Cultural Biography of Objects.” World Archaeology 31 (2): 169–178.

- Greaves, Russell D. 2006. “Forager Landscape Use and Residential Organization.” In Archaeology and Ethnoarchaeology of Mobility, edited by Russell D. Greaves, Frederic Sellet, and Pei-Lin Yu, 127–152. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Grenand, Française, and Pierre Grenand. 1987. “La Côte d’Amapá, de la Bouche de l’Amazonie à la Baie d’Oyapock, à Travers la Tradition Orale Palikur.” Boletim do Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi 3 (1): 1–77.

- Grenand, Pierre, and Française Grenand. 1994. “Grande Amazonie.” In Situation des Populations Indigènes des Forêts Denses Humides, edited by Pierre Grenand, Française Grenand, and Serge Bahuchet, 89–175. Brussels: DG XII Environnement, Office des Publications Officielles des Communautés Européennes.

- Heckenberger, Michael J., and James B. Petersen. 1995. “Concentric Circular Village Patterns in the Caribbean: Comparisons from Amazonia.” In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology 379–390.

- Hoffman, B. 2009. Drums and Arrows: Ethnobotanical Classification and Use of Tropical Plants by a Maroon and Amerindian Community in Suriname, with Implications for Biocultural Conservation. PhD diss., University of Hawai’i, Manoa.

- Hofman, Corinne L., Lewis S. Borck, Jason E. Laffoon, Emma R. Slayton, Rebecca B. Scott, Thomas W. Breukel, Catarina Guzzo Falci, Maroussia Favre, and Menno L.P. Hoogland. 2020a. “Island Networks: Transformations of Inter-Community Social Relationships in the Lesser Antilles at the Advent of European Colonialism.” Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, doi:10.1080/15564894.2020.1748770.

- Hofman, Corinne L., and Eithne B. Carlin. 2010. “The Ever-Dynamic Caribbean: Exploring New Approaches to Unraveling Social Networks in the pre-Colonial and Early Colonial Periods.” In Linguistics and Archaeology in the Americas: The Historization of Language and Society, edited by Eithne B. Carlin, and Simon van de Kerke, 107–122. Leiden: Brill.