Abstract

This research proposes a pedagogic practice to increase dynamic independent student participation and engagement through the lens of the flipped classroom, promoting the understanding of learning as a cyclical process of the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. With recommendations that may support hybrid delivery of actor training delivered both face to face and via online platforms, this paper considers the student learning experience of approaching rehearsals when preparing for a role within the UK actor training conservatoire by applying an overview of the methodologies of two key practitioners to this framework. The publications in the English translation of the practitioners Stanislavski and Hagen have been used, to ensure that as authentic a voice as possible is examined.

Introduction

Actor training in the conservatoire setting aspires to enable ‘the practical, intellectual, physical and emotional skills of students in an environment that is enabling, supportive and empowering […] preparing students for a sustainable career in a rapidly changing professional environment’ (Federation of Drama Schools Citation2019). Training seeks to establish the performer as a creative being and the work of Bloom (Citation1956) and Krathwohl (Citation2002) outlines a systematic approach to building the learner toward this outcome. Rivers and Kinchin (Citation2019) however, contest that this is a non-linear process. It is the aim of this research paper to consider a framework for re-rendering the core principles of approaching a role in rehearsal by key practitioners through the lens of the flipped classroom (Sams and Bergmann Citation2012), informed by the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy,Footnote1 a classification of cognitive learning, to commonly taught acting practitioner processes, as reimagined by Rivers and Kinchin (Citation2019).

This discussion will suggest that the flipped classroom when applied to this model, within the context of rehearsals in an actor training setting, can maximise the involvement of students in face to face class time, whilst allowing them to process information at a rate that is appropriate to the individual learner (Sams and Bergmann Citation2012, 74, 24). This consideration of practical aspects of actor training will enable the proposal of a pedagogic approach in the absence of a formal commonly agreed framework, consciously acknowledging that such learning is not linear, but in fact cyclical. The subsequent recommendation could hold currency within both the actor training and university performing arts sector, by providing a bench mark model for pedagogic practice that promotes an integration of face to face rehearsal experiences with structured independent learning that can be engaged with via online platforms.

The taxonomy of educational objectives

The Classification of Educational Goals was first published in 1956 in the United States of America by Bloom et al to provide a classification tool for cognitive educational goals, see (Bloom Citation1956, 1–2). The intention was to provide specificity of approach when describing learning targets and outcomes, to enable effectively differentiated learning and assessment strategies (Bloom Citation1956, 2). The taxonomy was then subject to review and redefinition by one of the original contributors. The Taxonomy is a facilitating tool for cognitive educational planning, as acknowledged by Bloom, and not a device by which to attribute psychological judgements upon students (Bloom Citation1956, 6). The structure intended to identify and offer analytical classification of the intended cognitive outcomes of learners under the guidance of a teacher (Bloom Citation1956, 12), and not the behavioural outcomes. Importantly, the quality of the learning and any subsequent grading outcome was not intended to be captured by the taxonomy (Bloom Citation1956, 123), as this is outlined by the authors as also being affected and influenced by other external social and emotional experiential elements.

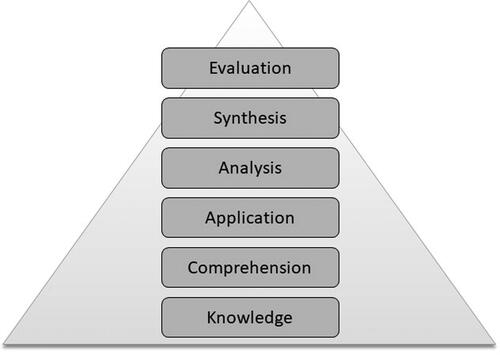

Figure 1. Bloom’s Taxonomy, redrawn by A McNamara (Bloom Citation1956, 201).

The difficulty in attempting to attribute a set classification to something that is of an inherently qualitative nature is identified and acknowledged by Bloom, but it is expressed that this obstacle has been overcome by allocating precise statements to each level of classification (Bloom Citation1956, 5). Also documented here is the concern that teachers may aspire only for higher orders of thinking under the taxonomy, leading to a disjointed approach to target setting and planning of learning activities, at the expense and oversight of the essential framework structure of the lower order activities. Therefore, the taxonomy was presented in a hierarchical format, to allow clear and relevant links and connections between the objectives (Bloom Citation1956, 6). Initially, the taxonomy was presented in six levels.

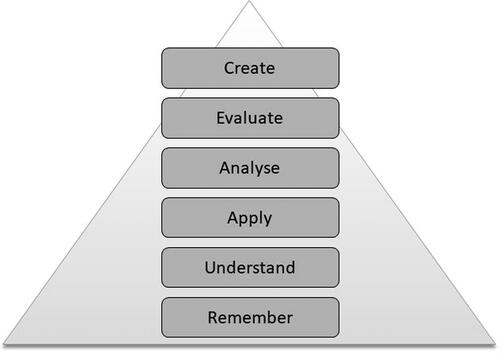

The purpose of the work was to establish a classification system for levels of understanding, which could then be used to assess and structure learning. The notion of and attached importance to lower, mid and higher order thinking, stemming from Bloom’s Taxonomies, asserts that different learning aims, and objectives can be stratified, each layer building on previously acquired skills and/or knowledge. Importantly, although this was presented in hierarchal triangular form structurally, Bloom acknowledged that it was possible to offer alternative orders (Bloom Citation1956, 18). The original categories were ordered ‘from simple to complex and from concrete to abstract’ (Krathwohl Citation2002, 212) and as a ‘cumulative hierarchy’ (Krathwohl Citation2002, 212). The subsequent revision further developed the multi-dimensional facets of the taxonomy, supporting and recognising different types of knowledge inherent within the learning process (Krathwohl Citation2002, 214). These were outlined by Krathwohl as factual, conceptual, procedural and meta-cognitive (Krathwohl Citation2002, 214) and expanded the breadth of the original taxonomy placing creativity as the pinnacle of the learning process.

Krathwohl explained his rationale for the revised order of the hierarchy of the taxonomy, which he termed the ‘Taxonomy Table’ (Krathwohl Citation2002, 215), presented in .

This new presentation of learning verbs allows the teacher to cross-reference the dimensions of knowledge with the newly structured cognitive dimensions (Krathwohl Citation2002, 215), acknowledging the complexity of learning processes.

Dynamic learning

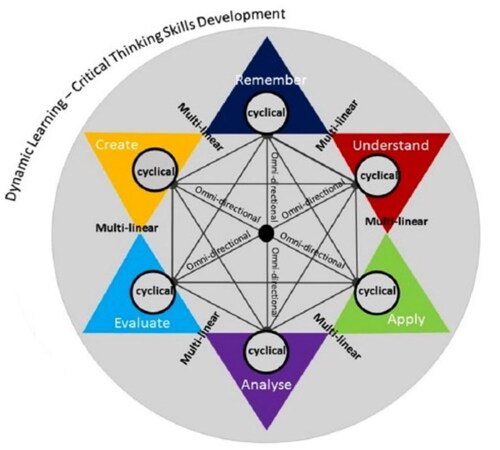

Investigating the development of critical thinking skills in Business education, Rivers and Kinchin (Citation2019) established a model of learning progression that counters the linear narrative of both the Bloom’s and Revised Bloom models (see ). Considering learning as a dynamic process, with students observed as moving to and fro between the orders of learning (151), Rivers and Kinchin explode the traditional triangular concepts, as illustrated above in and , and reimagine a messier approach to learning consisting of an omni-directional, multi-linear journey, with cyclical encounters within each of the levels of the taxonomy.

Figure 2. The Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, redrawn by A McNamara (Krathwohl Citation2002, 215).

Figure 3. Critical Thinking as a Dynamic Learning Process (Rivers and Kinchin Citation2019, 151) 3.

A teacher’s role within such a dynamic and cyclical, messy framework, is vital to scaffold and signpost development supporting the learner’s cognitive tools, making tasks more manageable, increasing success. The teacher’s function to both collaborate and work with students is highly important in this complex, non-linear scaffolding process, to ensure active rather than passive, independent learning that can operate efficiently beyond and between the teacher scaffold. By involving and engaging the student in the learning material through well-designed activities that respond to this multi-directional active approach, learning can be appropriately dynamic.

Scaffolding dynamic learning: Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy applied to actor training

To understand how the learning concepts of the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy may translate to actor training within a dynamic learning structure, key components of the actor’s rehearsal process must first be classified within the learning concepts of the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. The following discussions provide an introductory overview as to how the orders of thinking as defined by the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy may map against the preparation of a role in rehearsals, using the conceptual practices of Stanislavski and Hagen for indicative purposes. The acting practitioners Stanislavski and Hagen have been selected for scrutiny as they appear to be among the most commonly utilised among the Federation of Drama School member institutions, as indicated by a survey of the schools’ websites, although as Roznowski rightly points out, ‘[a] cursory overview on a website does not reveal what occurs behind the closed doors in studio training’ (Roznowski Citation2015, E3). How practices examined below explore different concepts of knowledge is important to this study as the authors of the techniques and practices do not explicitly outline the pedagogic elements of their work.

The preparatory work on a role can be divided into three great periods: studying it [lower order thinking], establishing the life of the role [mid order thinking], putting it into physical form [higher order thinking]. (Stanislavski Citation2013c, 3)

Lower order thinking

Stanislavski recommends that the lower order level work takes place prior to an actor commencing work on a character. This work is largely research based homework (Citation2013b, 223), which Stanislavski terms as analysis. This phrase used by Stanislavski contains a different connotation to that used by Bloom et al. and Krathwohl. Here Stanislavski details the importance of an actor knowing and understanding all the minutiae of a character and the role within the play under examination. These aspects of Stanislavski’s analysis are, in fact, therefore deemed by Bloom et al. and Krathwohl to be the lower order levels of Understanding and Remembering.

Further aspects of lower order thinking requiring work beyond the studio as outlined by Stanislavski are the actor’s establishment of a relaxed state, enabling them to be well-prepared for practical creative work (Citation2013a, 229, 94). This achievement and understanding of a relaxed state, Stanislavski asserts, will allow the actor to be increasingly open and receptive to working collaboratively in communion with the work of their fellow actors (Citation2013a, 185). Stanislavski states that this is achieved through dedication to private repetition work, as illustrated through his fictitious character’s progress through their own training as detailed in his writings (Citation2013a, 94). Thus, the actor may independently prepare themselves internally to find the inner justification that will go on to motivate the higher order action work (Citation2013a, 46).

Hagen outlines three areas she deems as necessary homework, to be completed and carried out beyond the studio; contextual research, character preparation and interpretation of the role. All aspects of this work come under the auspices of Bloom’s understanding and remembering. When researching a role, Hagen states that an actor must explore the play’s topic and themes intelligently (Citation1991, 237) and independently (Citation1991, 248). She highlights this as necessary contextual research (Citation2008, 30), to include detailed notes, ideas, questions, answers and other notable information. Hagen asserts that historical research must be completed prior to transplanting a character out of context (Citation2008, 136) as this informs the given circumstances of the character (Citation1991, 73), informing work to be carried out in the studio. Hagen acknowledges that this work may be time consuming and considered as laborious to the actor, but that ‘all tedious research is worth one inspired moment’ (Citation2008, 154) in practical application.

An actor must create a life for their character before a play begins (Citation1991, 142). To facilitate this, the actor must study the play as part of their preparation for a role making interpretative considerations. In the absence of a director in this independent process, Hagen places the actor in the role of responsibility (Citation1991, 242). This responsibility is described as including reading the play in its entirety (Citation1991, 248, 233) and carrying out the essential background work in seclusion and secrecy (Citation2008, 157). Hagen offers development of homework tasks, bridging the transition between the private, independent preparatory tasks and the communal directed exploratory work of the studio. This continues along the route of Krathwohl’s Revised Taxonomy of understanding into the mid-range level of application.

To further student understanding Hagen details the object exercises (Citation2008, 82) as a tool requiring private preparation to optimise success in a shared public environment (Citation2008, 86). To enable a successful transition from public to private, Hagen emphasises the need for the homework to continue (Citation1991, 248–250) and for the actor to be prepared to listen to the director (Citation1991, 252) so they may ascertain the relevance of both exploratory and preparatory tasks (Citation1991, 221), thus there are implications in relation to the application of techniques or knowledge.

Interpreting a role and preparatory work should be limited to lower order thinking actions and the actor must avoid higher order analysis when preparing a role, as this, in Hagen’s view, will lead to an unnecessary tension between the actor and the director (Citation2008, 149). Hagen is clear in her guidance that the independent learning elements of understanding a role are to facilitate efficient testing of the role in the studio, under the guidance of the director (Citation1991, 276, 77). As such the actor must undergo intensive private work and exercise (Citation1991, 248) to enable them to identify the basic components of their character, drawing from themselves as a resource (Citation1991, 56). Hagen specifically warns the actor to guard against independent clinical psychopathic analysis of the homework stage of preparation (Citation1991, 46), guiding them to continue this work through to shortly after their opening night in a theatrical production (Citation1991, 248).

Mid-level order thinking

Preparatory, mid-range order exercises that Stanislavski outlines as requiring the guidance of a teacher/director encompass aspects of application and analysis. Practical work that arises from the examination and examination of the text and it’s given circumstances (Citation2013c, 8), include the analysis, application and evaluation of the super objective, through line (Citation2013a, 241) and tempo-rhythms (Citation2013b, 184). Given that Stanislavski espouses the establishment of a broad bedrock for creativity (Citation2013a, 159) it is unsurprising that so many of Stanislavski’s outlined technical approaches to acting sit within the mid-range order of Krathwohl’s Revised Taxonomy; effecting public solitude (Citation2013a, 71), circles of attention (Citation2013a, 65), the setting of objectives, be they outer, inner or psychological (Citation2013a, 104) and affective memory (Citation2013a, 159). The latter, Stanislavski states, provides a bedrock for creativity. His aspiration is that the actor will achieve the ability to use and manipulate vocal and physical expression in order to fulfil their creative, higher order needs (Citation2013b, 57, 80).

Similarly, Hagen outlines how the actor’s preparatory mid order processes will then enable their exploration of self as a resource (Citation2008, 25) and allow the actor to discover detail (Citation2008, 45) through action (Citation1991, 99). A necessary process of private self-discovery (Citation2008, 34) may embrace transference of personal concepts to the actor’s character within. This may then be examined in practice through application (Citation2008, 117), a Revised Taxonomy mid-order process. When applying their understanding to a role, Hagen instructs the actor to score the role on six stages (Citation1991, 257). This process, she suggests, will allow the actor to recognise needs and feelings and make connections between these and ensuing behaviour (Citation2008, 26). The considerations an actor will make during the independent preparatory phase will be tested during rehearsals (Citation1991, 276–277), Hagen asserts. This will allow the background research to inform the given circumstances, motivating the character’s needs, pursuits and relationships. This transference from preparation to action provided justifications for the actor’s choices (Citation1991, 73), making the actor a participant in a new world (Citation1991, 216).

Higher order thinking

Stanislavski’s development of now seminal techniques pursues the end goal of the actor balancing emotion with intelligence in performance (Citation2013a, 216), juggling, balancing and continuing a multi-faceted character (Citation2013a, 221). To achieve this, Stanislavski promotes the use of the actor’s imagination and inner motive as the driving force (Citation2013a, 211) behind the creative process. This higher level of thinking as outlined in the Revised Taxonomy, is aided by such exercises and techniques as the Magic If (Citation2013a, 47), and improvisations (Citation2013c, 219). Stanislavski wants his actors to utilise their imagination to fully realise and create a character, breathing life into rehearsed ideas, stating that imagination unlocks creativity (Citation2013a, 57, 60). As with Krathwohl, Stanislavski values guided creation most highly.

For Hagen the rehearsal space is a laboratory (Citation1991, 295) for the communal creation of a culture of curiosity (Citation2008, 29) and self-awareness (Citation2008, 32), where the actor can experiment with technique (Citation2008, 110), create (Citation2008, 75), explore and test different tasks (Citation1991, 127) and conditions until ingrained in the actor (Citation2008, 133). Hagen utilised the German word for rehearsal, die Probe, ‘to test, to try […] to adventure’ (Citation2008, 192). The higher orders of the Revised Taxonomy hold the most currency in Hagen’s studio space. There Hagen believes that the guidance of a director can hone and shape the actor’s intelligence (Citation1991, 237), asking them not to judge, but to constructively critique, offering neither approval nor disapproval (Citation2008, 192). Analysis, evaluation and creation, according to Hagen, belong in this part of the actor’s process, all higher order thinking elements of the Revised Taxonomy. Hagen details how an actor may be led up to the very final phase of rehearsals into performance, when, if correctly trained, they will be capable of the final editing and selecting phase of preparation (Citation2008, 149), creating a new life for the character (Citation2008, 78), feeling the results (Citation2008, 111) through physical actions (Citation2008, 84, 185).

Reflections on the taxonomy for actor training: flipping the rehearsal room

It is interesting that in the description of the work of the key practitioners above, it is the lower order elements of each practice that take up the greater weighting of the narrative. Similarly, within a crowded actor training curriculum, these processes may engage a large quantity of resources in terms of studio and staff time, particularly within larger cohorts. As lower order thinking is traditionally considered to require high teacher dependency, there is little room left within the structure of a class to test, explore, analyse and investigate the students’ newly acquired knowledge. However, if the majority of lower order thinking processes and exchanges occur outside of the teaching studio, class leaders are left free to interrogate their students’ knowledge and understanding through a dynamic and responsive student-centred approach to the higher order thinking activities of analysis, evaluation and creation.

The practices of these influential historical actor training practitioners give support to the student’s use of independent yet scaffolded preparatory homework to engage with the lower order thinking concepts. They also place value and emphasis on higher order thinking processes taking place within the studio setting, under the face to face guidance of the teacher or director. This paper proposes that those interactions that develop, produce, utilise and sustain higher order thinking, such as analysis, evaluation, application and creation, have a higher requirement for face to face tutor support than those which promote lower order thinking, such as recall, memorisation and repetition, which may be supported via guided online and/or independent learning. By enabling the tutor-student contact hours to be filled with value enhanced activities that instil and encourage higher order thinking and practices, class times become more enriched and increasingly enriching for the learner. To facilitate this proposed practice, it is therefore necessary for the essentially foundation building lower order activities to be fully scaffolded beyond the direct contact setting.

This approach to the flipped classroom does not advocate a self-instructive approach, but rather promotes and imbues value in the reflective practices and preparatory activities that are possible via remote directed learning, as one may find in distance learning courses. This possibility holds great potential for a hybrid delivery model for the performing arts at a time when the global Covid-19 pandemic has brought about the requirement for social distancing, impacting the numbers allowed to engage in physical gatherings and reducing the frequency of such face to face encounters.

Sams and Bergmann claim origination and formulation of the concept of the flipped classroom (Citation2012, 110), advocating the removal of activities from the classroom scenario that do not require the physical presence of the teacher. The flipped classroom reverses the conventional structure of lessons, delivering activities that traditionally may have been homework activities in class time and placing the gathering and receipt of information as a homework task. To put it succinctly: homework tasks become preparation activities. Preparatory activities are centred on the acquisition of knowledge, enabling the learner to take responsibility for understanding concepts (Lage, Platt, and Treglia Citation2000, 34). This technique is cited by the authors as having many benefits once students come together with their teacher in the classroom setting, including allowing the teacher to scaffold and support each student individually as needed (Citation2012, 23). Under Sams and Bergmann’s flipped classroom model, the processes of learning become the focus of each class, with the student responsible for and choosing their own rate of learning (Citation2012, 60–67). This approach is also used to demonstrate the resulting class work being of a greater complexity (Lage, Platt, and Treglia Citation2000, 34), as the teacher works toward the learning objective and the individual student determines the methodology (Lage, Platt, and Treglia Citation2000, 32), in a truly co-constructed learning environment.

Recommendations: dynamic learning for the hybrid performing arts landscape

Drawing inspiration from Rivers and Kinchin (Citation2019) model of critical thinking skills as a cyclical and inter-relational evaluation of the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, , below, provides a model for dynamic hybrid learning for the performing arts. This overview proposes a pedagogic model for the cyclical, inter-connected dynamic learning process, that enables scaffolded opportunities for independent online learning that speak directly to and from the face to face guided practice of the studio. This model recognises the relationships between concepts as developmental points in the learning process, as well as understanding the cyclical, repeating and developing nature of the overarching pedagogic journey.

In 2020, the entire sector of performing arts training was forced online due to the isolating effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Moving forwards, the performing arts training sector may benefit from taught elements continuing to be delivered via an online methodology. Suggested areas may include but are not limited to; preparatory work and learning, contextual research, initial exploratory exercises and development, learning and consolidation of material, aide memoires and resources for rehearsal, revision and practice sessions. This model enables the optimisation of valuable studio time when disrupting factors such as the global Covid-19 pandemic, or other stressors, such as economic or resourcing issues impact physical access to shared practical spaces.

The relevance of this approach for experiential learners (Lage, Platt, and Treglia Citation2000, 41) in the performing arts is that the face to face contact time between teacher and student becomes high value (Sams and Bergmann Citation2012, 73). This flexibility and independence of learning beyond the studio supports students who have a heavy workload by allowing them to manage their own learning time as they require (Citation2012, 22) and to access learning beyond face to face scenarios. In a pedagogic approach most applicable to the process of actor training in a hybrid model of delivery, a flipped classroom enables students to complete preparatory and lower order learning exercises independently within a scaffolded structure that will then facilitate in-depth work in the classroom. For independent study, systems of help and assistance are to be structured (Wertsch and Tulviste Citation2006) to ensure maximum efficiency over a gradual growth process, dependent on indivdualised level of ability and performance. The scaffolding of independent activities is essential as the learners’ need for guidance and structure is greater when they are first introduced to a concept, with a growth toward independence occurring following a period of scaffolding, provided by the teacher figure (Tharp and Gallimore Citation2006).

For such a culture of learning to be embraced across both an in-person learning environment as well as in structured private individual study simultaneously, the shared principles of such a hybrid delivery model must feature in all interactions and guidance (Tharp and Gallimore Citation2006, 93). Tharp and Gallimore in their exploration of educationalist Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, assert that for social elements to transform into psychological notions, internalisation must occur, and this requires an acknowledgement and acceptance of sociological context by both learner and teacher (Citation2006, 94). Furthermore, they stipulate that these learning processes and exchanges must be holistic, active engagements, as inert passive participation is a fruitless developmental endeavour (Citation2006, 95). When independent activities have a relevance, pertinence and currency based in the practical face to face work of the studio, the associated value will optimise student engagement and the relevance of the independent activities will maximise the likelihood of student and staff engagement alike, where the learner can take ownership of their personal learning journey (Prior Citation2012, 208). Actor training, whilst pursuing professional training for actors (Evans Citation2008, 14), must work toward achieving a mastery of the art of independent learning, as well as guided creativity:

…we can develop a higher level of performing than the one which has resulted from the hit- or-miss customs of the past. (Hagen Citation2008, 4)

To investigate and develop the full potential for this dynamic flipped learning model in the performing arts, further research is required. Specific areas requiring more detailed investigation include the application of the dynamic learning for the hybrid performing arts landscape model to specific areas of skills-based training in the performing arts beyond the context of the rehearsal room, for example, in voice, singing and movement. Such examination and pedagogic enquiry will provide a more nuanced empirical analysis of the ongoing long-term benefit of this pedagogic approach as a tool for performer training in conservatoires and Higher Education settings.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna McNamara

Anna McNamara is Director of Learning and Teaching at the Guildford School of Acting, University of Surrey. She trained in Musical Theatre at the Guildford School of Acting before moving into teaching full time in 2001, gaining an MA in Education. Anna holds teaching qualifications in dance, singing and music, and drama. Anna is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. In 2017 she was awarded the University of Surrey Vice Chancellor’s award for Teacher of the Year.

Notes

1 For ease of reading, all references made to the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy refer to the work of Krathwohl (Citation2002). Reference to the original Bloom’s Taxonomy refers to Bloom (Citation1956), unless otherwise directed.

References

- Bloom, B. S., ed., 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook 1, Cognitive Domain. 1st ed. New York: David McKay.

- Evans, M. 2008. Movement Training for the Modern Actor. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

- Federation of Drama Schools. 2019. http://www.federationofdramaschools.co.uk/ [Accessed 10 Oct 2020].

- Hagen, U. 1991. A Challenge for the Actor. New York: Scribner.

- Hagen, U. 2008. Respect for Acting. 1st ed. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

- Krathwohl, D. 2002. “A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview.” Theory into Practice 41 (4): 212–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

- Lage, M., G. Platt, and M. Treglia. 2000. “Inverting the Classroom: A Gateway to Creating an Inclusive Learning Environment.” The Journal of Economic Education 31 (1): 30–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220480009596759

- Prior, R. W. 2012. Teaching Actors: Knowledge Transfer in Actor Training. 1st ed. Bristol: Intellect.

- Rivers, C., and I. Kinchin. 2019. “Dynamic Learning: Designing a Hidden Pedagogy to Enhance Critical Thinking Skills Development.” Management Teaching Review 4 (2): 148–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298118807224

- Roznowski, R. 2015. “Transforming Actor Education in the Digital Age.” Theatre Topics 25 (3): E1–E7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2015.0028

- Sams, A., and J. Bergmann. 2012. Flip Your Classroom; Reach Every Student in Every Class Everyday. ISTE.

- Stanislavski, C. 2013a. An Actor Prepares. London: Bloomsbury.

- Stanislavski, C. 2013b. Building a Character. London: Bloomsbury.

- Stanislavski, C. 2013c. Creating a Role. London: Bloomsbury.

- Tharp, R., and R. Gallimore. 2006. “A Theory of Teaching as Assisted Performance.” In Learning Relationships in the Classroom, edited by. D. Faulkner, K. Littleton, and M. Woodhead. London: Routledge in association with the Open University.

- Wertsch, J. J., and P. Tulviste. 2006. “L.S. Vygotsky and Contemporary Developmental Psychology.” In Learning Relationships in the Classroom, edited by D. Faulkner, K. Littleton, and M. Woodhead, 4th ed., 13–30. Oxon: Routledge in association with the Open University.