Abstract

Discussion on the role of listening in actor training is limited. Compared with studies on ear training for conservatoire music students, there is a gap in the literature regarding the ways in which student actors acquire and improve listening skills. This paper investigates the musicality inherent in Meisner Technique, an approach to actor training, and points to intersections with ear training in Dalcroze Eurhythmics, an approach to music education. It analyses the common ground between these pedagogical practices, drawing on sources from a variety of domains in which listening is foregrounded. It asserts that Meisner Technique and Dalcroze Eurhythmics promote similar forms of responsive, interpretative, and collaborative listening skills. This paper is written from the author’s interdisciplinary perspective as a teacher of acting and music at a university conservatoire. It offers insight into practical training through a personal, philosophical lens. Its themes are transferable to actor trainers and music educators engaged in continuing professional development.

Introduction

Listening is fundamental to the actor’s craft. In performance, listening is the channel through which the actor receives their scene partner’s words and intentions. In rehearsal, listening underpins the actor’s professional temperament and informs their successful collaboration within a group of artists. In training, listening unlocks the student actor’s potential for inquiry and empathy, increasing understanding of the self and others. Actor trainer Steven Wangh asserts:

All performance disciplines are deeply dependent upon listening. Musicians of all kinds, dancers, and actors must all learn to ‘listen’ aurally, visually, or kinesthetically [sic], to many signals, often to several signals at once. So, in one way or another, all teachers of performance are also teachers of ‘listening’. (Wangh Citation2013, 27)

Due to its quiet invisibility, listening rarely draws attention to itself. For this reason, Western culture frequently positions the speaker as dominant and the listener as subordinate. This binary opposition is part of a logocentric tradition inherited from ancient times. Theatre practitioner and educator Jean Benedetti explains:

All early discussions of the actor’s art were made in terms of the precepts of rhetorical delivery laid down in Greece and Rome[.] Rhetoric is the art of persuasion, of convincing other people that what you are saying is true. You can persuade in two ways: by perfect logical argument, or by attracting a sympathetic emotional response. The best speeches do both. (Benedetti Citation2007, 7)

In practice, of course, all actors play both roles interchangeably, just as all human beings shift their bearings between being on ‘send’ and being on ‘receive’ in daily life. The interpersonal communication researcher Charles Berger explains that ‘We speak while we listen and we listen while we speak’:

[W]e may naively assume […] that acting and speaking on the one hand and perceiving and listening on the other must be subserved by isolated systems. [In fact,] these systems are coordinated and integrated to the point that they communicate with each other and do so in ways that humans are incapable of sensing. It is only because these systems can interact automatically, rapidly and without conscious awareness that humans can quickly adapt[.] (Berger Citation2011, 108)

Meisner Technique (MT) is rooted in Sanford Meisner’s early ambition to become a professional pianist. Musicality permeated his work as an acting teacher and is most evident in his pedagogical emphasis on listening. Writing early in Meisner’s career, music educator Melville Smith describes musicality as the ability to create ‘a meaningful ensemble of impressions’ from the simultaneous threads of music, and ‘to react musically to them’ (Smith Citation1934, 16). I cannot speculate on Meisner’s impressions of music, but I can point to ways in which he ‘react[ed] musically’. The primary source for his practice, Sanford Meisner On Acting (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987), is punctuated with musical analogies for the craft of acting. One secondary source (Adair Citation2005) offers useful commentary on the available anecdotes about ‘the symbiotic relationship Meisner believed existed between music and theatre’ (22). Beyond analogy and anecdote, I seek to identify concrete principles in MT which intersect with ear training in music education. In addition, as there is no published work to date on Meisner the musician, I offer some historical flags for future research.

Dalcroze Eurhythmics (DE) is influenced by Emile Jaques-Dalcroze’s early ambition to become a professional actor. Theatricality permeated his career as a music teacher and is most evident in his pedagogical emphasis on whole-body musicianship. Melville Smith suggests musicianship is attained when ‘the language of music is not only a means of communication from the outside in, but also a means of expression of what [the musician] feels within himself [sic]’ (Smith Citation1934, 16). This is musically equivalent to Konstantin Stanislavski’s examination of inner and outer states for the actor, a pursuit directly influenced by the work of Jaques-Dalcroze (Davidson Citation2021a, 194). The primary source for Jaques-Dalcroze’s practice, Rhythm, Music and Education (Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation1921] 1967), proposes movement as the fundamental means to analyse and understand music. I have published elsewhere on historical and pedagogical connections between Stanislavskian actor training and Dalcrozian music education (Davidson Citation2021a). Here, I seek to highlight aspects of DE which promote the acquisition and improvement of listening skills for the actor in parallel with MT.

Psychologist Carl Rogers proposes active listening as a process toward empathy. His research shows that a high degree of empathy facilitates self-directed learning. Rogers’ depiction of listening in a therapeutic setting is in parallel with tasks undertaken by the student actor and musician as they discover, analyse, and commune with either the fictional character they seek to inhabit, or the musical message they seek to project:

Entering the private perceptual world of the other […] becoming thoroughly at home in it […] being sensitive, moment by moment, to the changing felt meanings which flow in this other person […] temporarily living in the other’s life, moving about in it delicately without making judgements [] sensing meanings […] look[ing] with fresh and unfrightened eyes [and] lay[ing] aside your own views and values in order to enter another’s world without prejudice. (Rogers Citation1980, 143)

Historical background

Meisner’s formal training as a pianist took place a century ago in New York City. The Institute of Musical Art (IMA) was established by Frank Damrosch in 1905 and was the predecessor institution to the present-day Juilliard school. Meisner’s recent biography states that, following high school, ‘he spent two years at the Damrosch Institute’ and that he had ‘studied piano for years’ (Carville and Trost Citation2017, 40). The Juilliard Archives indicate Meisner was enrolled in the piano diploma programme in the academic year 1923–1924. Meisner’s piano teachers were Arthur Newstead and Zofia Naimska. He studied keyboard harmony with George Anson Wedge, music theory with A. Madeley Richardson, and attended the music history lectures of George H. Gartlan. Meisner’s ear-training and sight-singing teachers were Belle Julie Soudant and Helen Wiseman Whiley (Juilliard Archives email, 28 July 2022). It is clear from the IMA prospectus of 1923–1924 that Meisner inherited an educational ethos of technical rigour in pursuit of expressive freedom. This culture is outlined in an article ‘On Acting’ by singing faculty member Gardner Lamson in IMA’s magazine, The Baton:

The highest art is simply perfected automatism […] doing the same thing over and over, better each time, apparently a simple proposition, but involving years of intelligent and patient and very often elusive work[.] (Lamson Citation1923, 1–2)

Lamson’s article also refers to ‘French training’ as having a positive impact on acting technique at the time (Lamson Citation1923, 2). This alludes to Jacques Copeau’s company, the Vieux Colombier, which had been resident in New York City from 1917 to 1919 (Willis Citation1968, 27). Copeau was the leading theatrical advocate of Swiss music pedagogue Emile Jaques-Dalcroze. Theatre scholar Ronald Willis writes:

The visit of Copeau’s company […] undoubtedly focused attention on Dalcroze Eurhythmics as a training device for actors. […] It seeks to develop the actor’s physical responsiveness, his [sic] sense of rhythm, and his ability to control his body in movement. It makes use of two basic kinds of exercises, those of control and those of interpretation. (297)

By the mid-1920s, DE had been disseminated internationally. It became a core component of actor training at the Moscow Art Theatre where Stanislavski coined the term Tempo-Rhythm to describe the phenomenon of physicalising two contrasting rhythms simultaneously (Davidson Citation2021a, 193). The Polish-Russian émigré Richard Boleslavsky prescribed DE for all his actors at the American Laboratory Theatre in New York City (Willis Citation1968, 91) writing, ‘Just as rhythm is the basis of all the arts, so it is in the actor’s art. The performer whose body is not rhythmically trained has no instrument on which to play’ (296). Elsa Findlay taught DE at The Lab for six of its seven seasons. Her students included Harold Clurman and Lee Strasberg, two founders of the Group Theatre who invited Sanford Meisner to join their acting company in 1931. It is not clear whether DE played any explicit role in the Group Theatre’s process, but there is evidence Meisner played the piano at its classes and events:

While his [musical] talent was perhaps underused or underappreciated [Meisner] never completely abandoned his skills as a pianist, nor did he stop applying his [musical] training as he focused his energies on theatre and teaching. (Adair Citation2005, 13)

Dalcroze Eurhythmics (DE)

Jaques-Dalcroze identified several problems with music education at the turn of the twentieth century. Theory and harmony were taught abstractly without reference to actual sound. Instrumental technique was taught with no consideration for the effect of music on the listener. Classes in score reading and musical dictation neglected to train students to actually hear what they were reading, or to write what they actually heard (Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation1921] 1967, 5–11).

As Professor of Harmony at Geneva Conservatoire of Music, Jaques-Dalcroze confronted the ‘lack of aural skills, reduced sense of rhythm, and scarcity of creative expression’ (Stevenson Citation2021, 315). He sought to re-sensitise the music student to any form of repetitive practice (e.g., scales and arpeggios) and cautioned against a ‘tyranny of meaningless virtuosity’ (Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation1921] 1967, 120). For Jaques-Dalcroze, ‘drilling’ was mindless repetition, but mindful repetition offered ‘variety and challenge’ (Alperson Citation1994, 245). He developed improvisatory exercises to activate the student’s flexibility and openness to change (e.g., swapping, omitting, or adding rhythmic elements) while scaffolding new levels of achievement on each repetition. Outside the academy, Jaques-Dalcroze confronted the tendency for the general population to conflate the manual operation of a musical instrument with being a musician. He challenged the accepted wisdom that students ‘are taught at the piano […] before they can hear sounds or appreciate rhythms’ (Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation1921] 1967, 63). He asserted that the most vital way to learn music was through pre-instrumental training, facilitated by whole-body movement, to awaken active listening and provide the student with a lived experience of music’s sensory impact. Only after this process would they take to their instrument and apply their experience to musical repertoire.

Jaques-Dalcroze borrowed the term ‘automatism’ from physiology to describe physical patterns acquired through repetition. Again, this is not rote learning, it is mindful repetition as a means to promote expertise in the mechanics of the body, developing sensitivity to nuance, and accessing authentic instinct. Mindful repetition produces a kind of physical template embedded in the nervous system, accessible to the performer whether the body is in motion or stillness. Automatisms ‘allow the mind to be freed from attending to tasks already mastered’ (CIJD (Collège of the Institute Jaques-Dalcroze) Citation2019, 9) in order to focus on challenges posed by other aspects of performance. For Jaques-Dalcroze, ear training through DE would boost concentration, improve muscular effectiveness, accelerate mind-body communication, and facilitate ‘seeing oneself clearly’ (Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation1921] 1967, 62–63). Work on the artistic self will be addressed in discussion of the intersections between DE and MT.

In his lifetime, physiology and neuroscience were not equipped to measure what Jaques-Dalcroze intuited. Physiology now shows that the vestibular system connects ‘our kinesthetic [sic] perception of movement and our aural perception of musical sound’ (Urista Citation2016, 9–10). Evolutionary biology asserts that synchronisation of movement with music is central to human musicality (Davidson Citation2021b, 9). Music psychology demonstrates that kinaesthetic learning is ‘one of the three human sensory sub-modalities which are especially important for music’ (Galvao and Kemp Citation1999, 135). Music education philosophy suggests that ‘moving without actually performing music may be a powerful way of acquiring listening expertise’, and that a person moving without making music ‘may indeed be “listening to” and “listening for”’ (Cutietta and Stauffer Citation2003, 135).

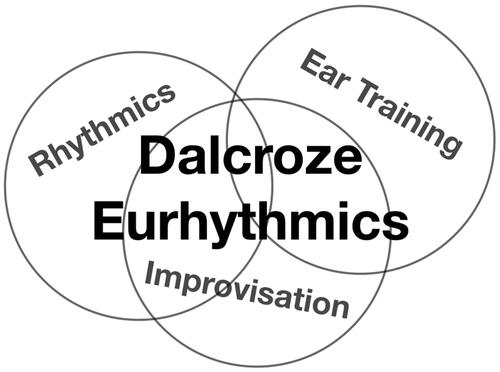

DE is a methodological approach to music education. illustrates its three main branches: Rhythmics, Ear Training, and Improvisation. DE’s non-linear trajectory engages the student with a full range of musical subjects in what DE teacher Robert Abramson calls a ‘consistent spiral of learning’ (Davidson Citation2021a, 194). Additionally, as the student aims higher on each repetition, aided by the teacher’s scaffolding, perhaps a more accurate model would be a helix:

[DE] encourages the student to revisit musical subjects from multiple perspectives, to embrace an increase in challenge on each visit, and to contextualize [sic] new experiences with what came before. This broadens and deepens awareness of the subject, fosters sensitivity to complexities, and encourages the application of basic principles to more advanced musical examples. (194)

Unique to ear training in DE are the student’s response to the teacher’s piano improvisation with whole-body movement, and the cohort-based collaboration between all members of the DE class. The student shows what they hear in the music through action rather than words. The teacher sees what the student is listening for and listening to, based on how they move. Each student learns more about the music by observing movement choices made by other students. Individuals, pairs, and groups improvise with the musical material to build dialogic and ensemble relationships. The teacher’s piano improvisation adapts to follow the students’ lead. Listening in a Dalcroze context is more than an aural experience, it is behavioural. By physicalising all aspects of music learning in this immersive way, the connection between the ear and the body is refined. The student engages with a lived experience of time, space, energy, weight, balance, and plasticity, drawn from the musical phenomenon being studied (Urista Citation2016, 4).

In practice, Jaques-Dalcroze prioritised listening from the start of his teaching career. He was aware of his students as listeners in classes and at concerts. He observed that the act of music listening, while seated in stillness, provoked in them a wide variety of surreptitious physical actions (Davidson Citation2021a, 188–189). He surmised that these small-scale movements were the by-product of an unconscious response or an inner analysis. Through lessons in solfège, the European term for ear training, Jaques-Dalcroze sought to make these invisible processes explicit. For example, walking or running engages the student in an exploration of musical tempo, beat, and subdivision. Awareness of the breath influences the perception of beginnings, endings, and lengths of musical phrases. Expressive use of the voice brings sensitivity to articulation, dynamic range, and melodic contour. Muscular contraction and expansion activate physical sensations equivalent to harmonic tension and release. Jaques-Dalcroze developed creative exercises for the student to discover how music behaves (i.e., embodied analysis) as well as diagnostic exercises for the teacher to determine the student’s understanding (i.e., continuous assessment) (Alperson Citation1994, 209). The teacher sees in real-time what the student is listening to and listening for, as well as what the student cannot yet perceive, identify, or express. In parallel with MT, ‘the process is endlessly diagnostic [and] it has to be side-coached and nurtured through each stage’ (Moseley Citation2012, 8).

Jaques-Dalcroze’s solfège develops the receptive skills required for cognitive analysis of pitch material, and fluid connection between the eye and ear while singing from a score. It promotes the productive skills required for singing in tune and in time with oneself and others, and inner hearing that facilitates transcription from sound to notational symbols. Standard practice in solfège uses the syllables do-re-mi-fa-so-la-[ti] to label notes in scales, modes, melodies, chords, etc. In DE, ear training and sight singing are supported by piano improvisation, providing harmonic context for any given exercise. Creative and collaborative skills are engaged through improvisation, inviting the student to produce new music, with and for others, using the materials and skills acquired through body-based ear training (see Urista Citation2016 and Stevenson Citation2021).

Meisner Technique (MT)

Meisner defines acting as ‘living truthfully under imaginary circumstances’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 15; 87; 136). Although this oft-quoted phrase appears three times in Sanford Meisner On Acting, it is helpful to explain it from a practitioner’s point of view. ‘Living’ poses a challenge to the actor to deal fully with each event from moment to moment. ‘Truthfully’ urges the actor to really do things rather than pretending to do them. ‘Imaginary’ entices the actor to engage thoroughly with the world of the character as set down in the writer’s text. ‘Circumstances’ demand that the actor accepts in detail the given situation of their character.

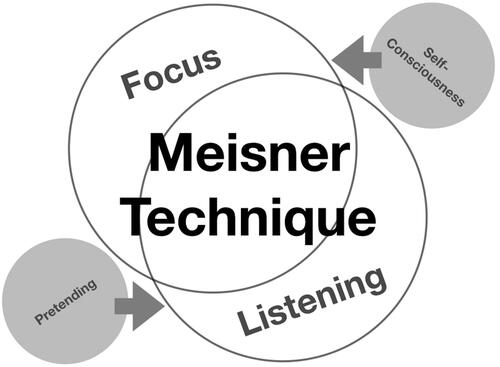

As Head of Acting at the Neighbourhood Playhouse in New York City, Meisner identified two problems that arise for the student actor: self-consciousness and pretending (Ditmyer Citation2018). Each of these problems fuels the other. Acting can be exposing and, when a student actor feels self-conscious, they do not attend to the words or behaviour of the other actor in the scene. They pretend to pay attention while thinking unhelpful thoughts, planning how to say their next line, or merely waiting for the other actor to stop speaking. Meisner asserted that, if the actor is required to repeat aloud everything spoken by their scene partner, immediately and precisely, their focus will remain entirely on the other actor with no opportunity for distracted thought. Under these conditions, self-consciousness will disappear from their work. When the actor is required to place full focus outside of themself, true character is revealed from moment to moment by spontaneous impulses. As Meisner expresses it, ‘What you do doesn’t depend on you; it depends on the other fellow’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 34).

In order to repeat the words of their scene partner, the student is obliged to listen actively. A loss of focus will make it impossible to repeat everything they hear. Meisner asserted that listening is the only real activity an actor has available to them, everything else is pretend (e.g., costumes or sound effects). Acting is a fiction, but the one real thing that exists in the midst of that fiction is listening. Stanislavski writes of this, ‘In life we listen properly because we’re interested, or because we have to. Onstage, most times, we only represent being attentive, we make a show of listening’ (Stanislavski Citation2017, 417). Meisner concluded, when the student repeats what their scene partner just said, we have audible proof of listening. If the quality of listening is simple and honest, the audience will perceive truthful behaviour. If the quality of listening is distracted or forced, the audience will perceive pretence. For Meisner, the actor who listens with their whole self will not be accused of pretending.

MT is a methodological approach to actor training. illustrates the key solutions Meisner offered for the problems of self-consciousness and pretending, i.e., focus and listening. MT’s linear trajectory engages the student in a comprehensive series of developmental exercises over a two-year period. Meisner describes his process with reference to automatism, in the style of a piano teacher who ‘takes you back to the absolute beginning of learning how to play’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 53):

Of course, if I were a pianist and sat for an hour just making each finger move in a certain way, the onlooker could very well say, ‘That’s boring!’ And it would be – to the onlooker. But the practitioner is somebody who is learning to funnel his instincts [sic], not give performances. (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 37)

Unique to MT are its pedagogical emphasis on active listening and the collaborative connection good listening cultivates between all members of the MT class. The student is guided away from dependence on rational thought and the absolutism of words. In parallel with DE, listening in a Meisner context is more than an aural experience, it is behavioural (Krasner Citation2010, 157). The attentive, receptive, perceptive skill of ‘reading behaviour compels actors to focus on scene-partners’ (159). Actor trainer David Shirley observes that this outward focus ‘developed in [Meisner’s] students the ability to listen and respond truthfully without imposing or indicating feelings and emotions’ (Shirley Citation2010, 201). Ultimately, this leads to ‘increased powers of observation, communication, responsiveness and spontaneity’ (202).

In practice, Meisner launched into listening from his very first lesson. He brings his students’ attention to the reality of their own listening, ‘Are you really listening to me? […] You’re not pretending that you’re listening’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 16). Then, he sets a task to engage active listening, instructing his students to ‘listen to the number of cars that you hear outside’. He raises the issue of authenticity (i.e., really doing) when he asks, ‘did you listen as yourself or were you playing some character?’ (17). Next, he draws directly from music education; ‘choose a melody that you like and sing it to yourself – just to yourself, not out loud’ (18). Playback in the mind’s ear awakens a skill which music education theorist Edwin Gordon calls audiation. Audiation is the ability to voluntarily recall music in one’s head; to understand not only individual sounds but also their relationships; and to anticipate, on hearing a new piece for the first time, how that music will behave. Gordon observes, ‘Sound itself is not music. Sound becomes music through audiation when, as with language, we translate sounds in our mind and give them meaning’ (Gordon Citation2008, 5).

Meisner developed his skill for audiation from an early age. As a stock boy in his family’s factory, ‘he would practice his pitch recognition and sight reading, going over solfège in his mind, that is, practicing his do-re-mi’s’ (Carville and Trost Citation2017, 15). The musician’s process of identifying and labelling rhythmic and melodic material in the mind’s ear equates with the actor’s process of listening ‘not only to what is said, but how it is said’ (Adair Citation2005, 162). The ability to apprehend nuances of speech rhythm, intonation, inflection, and cadence is integral to meaning-making. Decades later, Meisner’s students recalled that he had, on occasion, assessed them with his eyes closed. Perhaps this slice of theatre folklore points to Meisner’s deliberate audiation of his students’ work: attending, perceiving, predicting, analysing, and evaluating in the manner of a music educator. Musicologist Victor Zuckerkandl writes of fundamental differences between looking and listening. He observes that visual experiences are physically set apart from the viewer, whereas aural encounters with sound waves, as they permeate the listener’s whole self, enable a deeper connection with the source:

The eye discloses space to me in that it excludes me from it. The ear, on the other hand, discloses space to me in that it lets me participate in it. [] Where the eye draws the strict boundary line that divides without from within, world from self, the ear creates a bridge. (Zuckerkandl Citation1956, 291)

Intersections between

Below, I illuminate common ground between MT and DE with regard to the acquisition and improvement of listening skills. I focus first on a pedagogical principle found in both practices. I then discuss relationships between a series of six sample exercises. Finally, I draw together shared vocabularies from both practices to explain how the behavioural approaches of MT and DE promote responsive, interpretative, and collaborative listening for the student actor and musician. Through my interdisciplinary reflections, I assert that MT and DE offer complementary benefits to students in the other artistic domain.

Both practices successfully disentangle what Stanislavski calls ‘work on the self’ and ‘work on the role’ (Stanislavski Citation2017, xv, 7). Jaques-Dalcroze might have called his similar distinction ‘work on the musical self’ and ‘work on the musical subject’. In both MT and DE, the student artist is trained separately from, and prior to, work on a script or score. The foundation exercises of MT, unlike traditional theatre improvisation exercises, do not rely on fictional scenarios or personas (i.e., given circumstances). Meisner likened this freedom from context to practicing the piano without a musical repertoire: ‘When Horowitz plays scales, he isn’t concerned either with Beethoven or an audience’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 116). By this, he meant it is possible for a theatre artist to distil the essence of acting technique separately from scene work and character study. Being unencumbered by the given circumstances of a playwright’s text ‘turns the [student actor’s] focus away from the content of the improvisation to the process of the improvisation itself’ (McLaughlin Citation2012, 86). Such a procedure facilitates discoveries about the self in relation to the nature of the artform without the added demands of a specific piece of writing.

Similarly, distilling the essence of a musical subject is a conventional way for the DE teacher to structure learning. The Dalcroze Subjects are a wide range of musical elements, each studied for its own characteristics before being revealed in examples from repertoire (CIJD (Collège of the Institute Jaques-Dalcroze) Citation2019, 31). Working independently of a composer’s ‘given circumstances’ (i.e., the score) immerses the student in a musical phenomenon, inviting them to experience and improvise with it. Such a delineation permits the DE teacher to use various improvisatory strategies and styles to evoke and explore the subject. This is not variety for its own sake, but variety as a teaching tool. The student’s ear is guided to identify familiar characteristics of a musical subject in new musical landscapes. DE teacher Ruth Alperson writes that, ‘when a music element or idea was presented it was never done only once, or only one way’, quoting a student as saying, ‘You do it a zillion different ways until you can do it any way’ [italics mine] (Alperson Citation1994, 245–246).

The demarcation between artform and repertoire serves to avoid ‘confusion’, a word used by both Meisner and Jaques-Dalcroze in explaining their motivations. Implementing this demarcation was not without its challenges. Meisner recalls a student saying, ‘just listening to what’s going on and not applying it to anything else [] I’m a little confused […] Because I don’t know how I’m going to listen and answer truthfully, moment to moment, when I get a script’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 58). Meisner reassures the student they are not yet half-way through their process: ‘That’s the way you are going to begin with a script’ (58). MT teacher William Esper follows up on Meisner’s meaning, offering two reasons to acquire technique in isolation from text. First, he makes the pedagogical point that ‘Text is a very confusing element in acting. It can mask a great many problems’ (Esper and DiMarco Citation2008, 43). Second, he wryly suggests that ‘The fact that someone can memorize [sic] lines and speak them in more or less the right order might give people the impression that they’re acting’ (43).

Both Meisner and Jaques-Dalcroze recognised how easily the outer appearance of an artform can be counterfeited in order to impress the spectator. Jaques-Dalcroze observes, ‘Parents are apt to confuse music with the piano’ (Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation1921] 1967, 52). By this, he meant that a child’s capacity to press the piano keys ‘in more or less the right order’, to echo Esper above, does not make them a musician. I recall the experience of a student who stopped my music lesson to ask the genuine question, ‘When will we be doing some music?’ It is likely that this student’s prior training had established a narrow definition of the artform, consisting only of reading scores and playing instruments. They were not yet able to perceive how active, reactive, and interactive learning could develop their musicality and musicianship. Their desire for full and certain knowledge harks back to the word-based, fact-based guarantees of logocentrism. By contrast, Jaques-Dalcroze wanted his students to declare not merely, ‘I know’, but more profoundly, ‘I have experienced’ (Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation1921] 1967, 63). In my own teaching, the student artist is guided to yield as part of their craft; creativity cannot be forced or faked; they must learn to trust the process.

Both practices devote time and space to mentoring the student through a series of artistic encounters with the hands-on stuff of acting and musicking before introducing a playwright’s script or a composer’s score. This concentrates the student’s energies on their acquisition of personal skills and their developmental understanding of all aspects of their artform. Having examined this common pedagogical principle, I will demonstrate relationships between three pairs of sample exercises. I adopt the generally accepted name for each exercise and indicate them as titles using capitalisation: Follow (DE) and Repetition (MT); Quick Response (DE) and the Knock at the Door (MT); Association & Dissociation (DE) and the Independent Activity (MT).

Follow exercises often appear early in a DE lesson in order to ‘tune up’ the embodied listening of the student musician. Working with a specific musical element (e.g., changes of tempo or dynamic contrasts), the DE teacher improvises at the piano and the student matches the sound with improvised movement. Training instinct in this way connects the student’s ears to their muscles so listening can bypass conscious thought. Follow exercises establish an immediate relationship with musical sound. Similarly, in MT, early exercises awaken impulse through verbal sound, during which ‘you’ve got to trust your instincts and not your head’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 49). Over time, the impulse to match music with movement becomes a habit of kinaesthetic memory. However, movement in DE does not have to be an end in itself, as ‘sensations we experience consciously through movement are later drawn upon subconsciously to enhance future listening and performing experiences’ (Urista Citation2016, 10).

Repetition is encountered in both practices and is foundational to MT. Repetition exercises demand whole-body listening, compelling the student actor to observe closely and to respond rapidly. When Actor A verbalises something they notice about Actor B (e.g., ‘You’re wearing glasses’), Actor B repeats this from their own point of view (i.e., ‘I’m wearing glasses’). These same words bounce back and forth between them, instantly and accurately, like a musical ostinato. The two actors remain attentive to nuances in each other’s behaviour and, when one actor observes a change in the other, the words change in response (e.g., Actor A: You took off your glasses!). All observations are expressed as statements, not questions, keeping the focus in the present moment. Each actor gives honest answers, expresses their point of view, and works off the other’s behaviour (Ditmyer Citation2018). Repetition in MT is not an end in itself. However, in the initial stages, the Repetition exercise simply requires the actor to follow their scene partner’s words and respond quickly to change.

Quick Response exercises in DE pose more precise challenges than Follow exercises, namely the negotiation between flexible timing and decisive feedback. In a Quick Response exercise, the DE teacher gives aural signals while improvising music at the piano. These signals may be verbal or musical; and, between students, visual or tactile. The student reacts with a given response at a specific time (e.g., a particular pitch from the piano incites the student to change direction in the room on the next beat of the bar). Quick Response exercises activate and stabilise the body’s neuro-muscular connection, honing accuracy and closing the gap between impulse and action. The immediacy required of a Quick Response is captured in Meisner’s use of the evocative phrase, ‘quick as flame’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 115). Meisner’s aesthetic opinions on honest immediacy in acting are in parallel with Jaques-Dalcroze’s view of authenticity in performance of all kinds (Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation1921] 1967, 199–230).

The Knock at the Door exercise in MT asks the student actor to interpret an essentially musical event. So long as theatrical artifice is avoided, Meisner writes, ‘a knock has a meaning’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 46). Actor A is inside the studio; Actor B is outside. Actor B comes to the door and knocks in three different ways, leaving a ten-second pause between each. Actor A interprets each of these with a spoken response (e.g., ‘That’s a confident knock’). The exercise sensitises the ear to rhythm, pitch, dynamic, articulation, etc., eliciting a swift and simple interpretation. Some of my students have immediate imaginative impulses (e.g., a surprise visit, an unwanted interruption); others, challenged by the lack of given circumstances, succumb to self-consciousness and search in vain for impressive adjectives. The Knock at the Door demands instant interpretation of another human being’s communication through non-verbal sound. The door becomes a percussion instrument that resounds with the student actor’s intention, and calls for a subjective response from their scene partner.

Association & Dissociation exercises in DE challenge the student musician to listen to, perceive, and express two or more musical ideas independently and in counterpoint. This gradually builds masterful awareness and control of several voices simultaneously. The teacher improvises piano music with two voices (e.g., a bass line with a steady pulse against a syncopated melody). To begin, the student moves each voice in isolated areas of the body (e.g., walk the steady bass/tap the melody). Then, as both voices are physicalised simultaneously, the two separate voices integrate, and the student is encouraged to focus on the global sensation in the body. Next, the teacher swaps the two voices at the piano (i.e., syncopated bass/steady melody) and the student swaps the voices in their body (i.e., feet/hands). Finally, the teacher calls verbal signals for a Quick Response exercise, and the student develops expertise in swapping both voices between different parts of the body, instantly and with physical ease.

The Independent Activity exercise in MT applies Association & Dissociation in an actorly context. If acting is really doing, then the student actor needs something real to do. Ditmyer gives five parameters for an Independent Activity: it must be concrete, specific, difficult, urgent, and have a standard of perfection (Ditmyer Citation2018). My student actors offer everything from balancing a chair on one finger to solving a mathematical equation in under three minutes. Actor A is inside the studio; Actor B is outside. Actor A begins their activity. Via a Knock at the Door, Actor B elicits a response from Actor A who now has to manage the counterpoint between the Independent Activity and the Repetition exercise which play out simultaneously due to the presence of Actor B. Having a compelling reason to do the activity engages imagination, and aspiring to its difficulty intensifies concentration (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 53–54). The student’s embodied listening is vastly expanded by this example of musicality in MT. It presents an impressive polyrhythmic challenge.

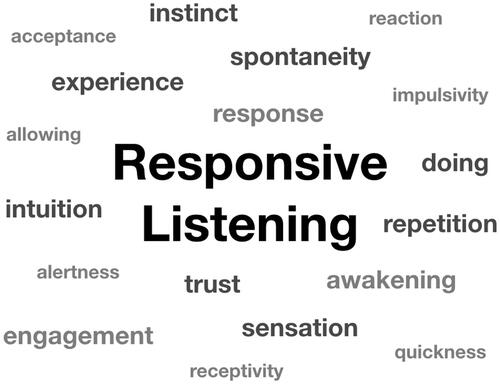

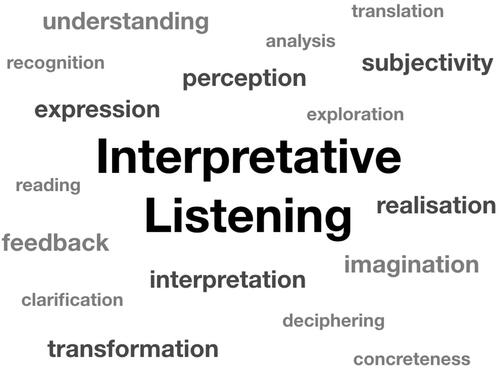

In drawing this paper to a close, I offer three groups of vocabulary shared by both MT and DE. I have gathered these together during detailed readings of primary sources; while analysing terminology in secondary sources; and in documenting reflections of student actors and musicians who have undertaken my MT and DE classes. I present them as three ‘word clouds’, graphic representations titled: Responsive Listening, Interpretative Listening, and Collaborative Listening.

Responsive Listening () is characteristic of MT and DE. Both practices cultivate responsiveness by training impulse, instinct, and intuition. They set aside conscious reasoning in favour of unconscious processing. The student of either practice is guided to deal fully with sensation before abstraction, reacting before rationalising, and doing before thinking. Alperson explains, ‘we often underestimate our capacity to get the message through our senses – we try to analyze [sic] an impression before we fully experience it’ (Alperson Citation1994, 36). Similarly, MT teacher Nick Moseley advises his students to be ‘listening with your body, bypassing the judgemental, analytical part of your brain […] and allowing the body to mirror your partner’s, so it is not just the sound but their whole presence to which you are responding’ (Moseley Citation2012, 19).

Interpretative Listening () is characteristic of MT and DE. Both practices cultivate perception, recognition, and transformation. The student works concretely with what they encounter in the room, in the moment. The student actor responds to their scene partner’s behaviour and the student musician makes a subjective response to qualities in the music or the movement of others. In MT, the importance of interpreting behaviour is hammered home in Meisner’s writing, e.g., ‘an ounce of behavior [sic] is worth a pound of words’ (Meisner and Longwell Citation1987, 4; 29). The Dalcrozian approach to musical interpretation is built on ‘bodily experience [which] constitutes a kind of knowing that is deep, pre-reflective, and subjective’ (Andrianopoulou Citation2020, 112). When DE classes focus on musical repertoire, they may include a process known as plastique animée, which calls on the student’s subjective interpretation in making a physical analysis and choreographic realisation of the piece of music being studied (CIJD (Collège of the Institute Jaques-Dalcroze) Citation2019, 26–29).

Collaborative Listening () is characteristic of MT and DE. Both practices cultivate adaptability, empathy, and teamwork. They foster sensitivity and responsibility, facilitating a collaborative, communicative, and co-operative spirit. Either practice offers an improvisatory forum encouraging flexibility and openness to change. The student adjusts to signals from others, works with given materials and circumstances, and reacts to aural, visual, physical, and tactile signals. They develop mutual understanding of others based on observation and non-verbal connection. Alperson’s study of DE students finds ‘a strong sense of working and learning together; they viewed their peers as supportive and non-competitive and shared an awareness of a group identity’ (Alperson Citation1994, 194). Actor trainer David Krasner writes that MT ‘emphasises ensemble behaviour, creating a spontaneous exchange in a jazz-like atmosphere of action and reaction […] relational, dialogic and alive to immediate and spontaneous human communication and interaction’ (Krasner Citation2010, 160).

Conclusion

This paper makes a contribution to the research literature on the student actor’s acquisition and improvement of listening skills. It sits in parallel with studies on ear training for conservatoire music students. The paper has positioned behavioural listening in actor training as a receptive channel for words and intentions, as a foundation for good professional collaboration, and as a tool for inquiry that increases empathy and understanding. It has consulted literature from a variety of domains in which listening is foregrounded, including philosophy, pedagogy, and psychology. The paper has unfolded historical backdrops to the work of Sanford Meisner and Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, and has summarised the principles of their approaches. It has investigated the musicality of MT and mapped out intersections with ear training in DE. Discussion has provided detailed descriptions and working analyses of selected exercises. The paper asserts that the student of either or both approaches acquires behavioural listening skills that make a vital contribution to professional artistry.

The author invites actor trainers and music educators alike to reflect on the place and purpose of listening in their own teaching practice. For example, following the philosophical thread in this paper, how does your approach to teaching encourage your students to ‘dwell with’, ‘abide by’, and ‘co-exist with’ one another, and listen to the intent of the creator of the work your students seek to perform (Fiumara Citation1990, 15)? Following the pedagogical thread in this paper, how are responsive, interpretative, and collaborative listening fostered as skills in your classroom? Which specific exercises in your practice engage students to listen and respond ‘to several signals at once’ (Wangh Citation2013, 27)? As these ‘several signals’ constitute a polyrhythmic demand, what sequential or iterative processes do you offer your students to help them experience two or more things at once (i.e., activities, rhythms, etc.)? How do you stimulate your students’ curiosity for dissecting and reassembling the global sensation of polyrhythm in the body, mind, and voice? Finally, following the psychological thread in this paper (Rogers Citation1980), how might you empower your students to assert the silent musicality of their actorly self, or the actorly empathy of their musical self? How might active listening awaken your students’ self-directed inquiry into the fictional world they seek to inhabit, or the musical message they seek to communicate?

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a paper given at the Fourth International Conference of Dalcroze Studies (ICDS) at the Karol Szymanowski Academy of Music, Katowice, Poland in July 2019. Thanks to Steven Ditmyer, Head of Meisner International, whose workshops inspired me to develop my teaching practice in Meisner Technique. Thanks to Silvia del Bianco, Director of the Institute Jaques-Dalcroze, who suggested that acting exercises may have the potential to improve the performance skills of Dalcroze Eurhythmics students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrew Davidson

Andrew Davidson is an Australian theatre practitioner and musician with specialisms in actor training and music education. He is based in London, UK, and is Senior Lecturer in Acting & Musical Theatre at Guildford School of Acting (GSA), University of Surrey. Andrew is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (FHEA) and the Royal Society for the Arts (FRSA). He is a graduate of Australia’s National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) and holds a Master of Music degree from Longy School of Music, USA. Andrew directs theatre, writes music, and plays piano for dance. He is a qualified teacher of Dalcroze Eurhythmics and has undertaken training in Meisner Technique. Andrew has presented at conferences and workshops internationally, and has published in Stanislavski Studies and Research in Dance Education.

References

- Adair, Aaron. 2005. “Analyzing and Applying the Sanford Meisner Approach to Acting.” PhD diss., University of Texas.

- Alperson, Ruth. 1994. “A Qualitative Study of Dalcroze Eurhythmics Classes for Adults.” PhD diss., New York University.

- Andrianopoulou, Monika. 2020. Aural Education: Reconceptualising Ear Training in Higher Music Education. SEMPRE Studies in the Psychology of Music. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Benedetti, Jean. 2007. The Art of the Actor: The Essential History of Acting from Classical Times to the Present Day. New York: Routledge.

- Berger, Charles R. 2011. “Listening is for Acting.” International Journal of Listening 25 (1–2): 104–110. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2011.536477

- Brook, Peter. 2008. The Empty Space. London: Penguin.

- Carville, James, and Scott Tillma Trost. 2017. De Tree a We: The Remarkable Lives of Sanford Meisner, James Carville and Boolu. New York: GR8 Books.

- CIJD (Collège of the Institute Jaques-Dalcroze). 2019. The Dalcroze Identity: Professional Training in Dalcroze Eurhythmics, Theory & Practice. Geneva: Collège of IJD.

- Cutietta, Robert A., and Sandra L. Stauffer. 2003. “Listening Reconsidered.” In Praxial Music Education: Reflections and Dialogues, edited by David J. Elliott, 123–141. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Davidson, Andrew. 2021a. “Konstantin Stanislavski and Emile Jaques-Dalcroze: Historical and Pedagogical Connections between Actor Training and Music Education.” Stanislavski Studies 9 (2): 185–203. doi: 10.1080/20567790.2021.1945811

- Davidson, Andrew. 2021b. “The Cycle of Creativity’: A Case Study of the Working Relationship between a Dance Teacher and a Dance Musician in a Ballet Class.” Research in Dance Education: 1–19. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1080/14647893.2021.1971645

- Ditmyer, Steven. 2018. Foundations of Meisner Technique. London: Workshop, Meisner International, June 18–22.

- Esper, William, and Damon DiMarco. 2008. The Actor’s Art and Craft: William Esper Teaches the Meisner Technique. New York: Random House.

- Fiumara, Gemma Corradi. 1990. The Other Side of Language: A Philosophy of Listening. Translated by Charles Lambert. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Galvao, Afonso, and Anthony Kemp. 1999. “Kinaesthesia and Instrumental Music Instruction: Some Implications.” Psychology of Music 27 (2): 129–137.

- Gordon, Edwin E. 2008. Clarity by Comparison and Relationship: A Bedtime Reader for Music Educators. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

- Jaques-Dalcroze, Emile. 1921 [1967]. Rhythm, Music and Education. Translated by Harold F. Rubenstein. London: Dalcroze Society.

- Krasner, David. 2010. “Strasberg, Adler and Meisner: Method Acting.” In Actor Training. 2nd ed., edited by Alison Hodge, 144–163. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lamson, Gardner. 1923. “On Acting.” The Baton 2 (5): 1–2.

- McLaughlin, Anthony. 2012. “Meisner across Paradigms: The Phenomenal Dynamic of Sanford Meisner’s Technique of Acting and Its Resonances with Postmodern Performance.” PhD diss., University of Exeter.

- Meisner, Sanford, and Dennis Longwell. 1987. Sanford Meisner: On Acting. New York: Vintage.

- Moseley, Nick. 2012. Meisner in Practice. London: Nick Hern Books.

- Rogers, Carl. 1980. A Way of Being. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Shirley, David. 2010. “The Reality of Doing’: Meisner Technique and British Actor Training.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 1 (2): 199–213. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2010.505005

- Smith, Melville. 1934. “Solfège: An Essential in Musicianship.” Music Supervisors’ Journal 20 (5): 16–61.

- Stanislavski, Konstantin. 2017. An Actor’s Work. Translated by Jean Benedetti. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Stevenson, John Robert. 2021. “The Solfège of Émile Jaques-Dalcroze.” In The Routledge Companion to Aural Skills Pedagogy: Before, in, and beyond Higher Education, edited by Kent D. Cleland and Paul Fleet, 306–319. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Urista, Diane. 2016. The Moving Body in the Aural Skills Classroom: A Eurhythmics Based Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wangh, Stephen. 2013. The Heart of Teaching: Empowering Students in the Performing Arts. New York: Routledge.

- Willis, Ronald Arthur. 1968. “The American Laboratory Theatre, 1923–1930.” PhD diss., University of Iowa.

- Zuckerkandl, Victor. 1956. Sound and Symbol: Music and the External World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.