Abstract

How might ‘agency’ be practiced in the meeting of performer and text? What are the ethical concerns of how these two materials might merge? The analysis draws on the author’s research at the Norwegian Theatre Academy with students of diverse backgrounds. It traces notions of agency from the institutional context to the specifics of studio exercises: acknowledging these as interconnecting systems which affect each other. It proposes a trans-aesthetic approach which foregrounds agency as primary mode of learning. The work contributes to the field by developing an analytical strategy of overlay and simultaneity: exploring how different methods may co-exist. It considers text and body as heterogeneous hybrids: bodies as texts and texts as bodies, drawing on Camilleri’s research on hybridity and the bodyworld, Barad’s intra-action, Crenshaw’s intersectionality, Meizel’s multivocality, Cahill’s hesitation and Russel’s glitch feminism, among others. It grounds the practical exploration in existing approaches such as Stanislavksi and Viewpoints, discussing how these methods expand to meet 2024; and aiming to speak to students and teachers whose work spans a range of methodological backgrounds. In relation to text and body as merged hybrids, this article explores examples such as: exploding the text, code shifting, aesthetic hybridity, glitching - all as examples of heterogeneous sonic world-making.

Introduction

How might ‘agency’ be understood or practiced in the meeting of performer and text? Does the performer have agency over the text, or are they ‘at the service of’ the choices made by the author/director? What are the ethical concerns of how these two materials might merge? As an acting and voice teacher, at (what might be pigeon-holed as) an ‘experimental’ school, I have for years been fascinated by performers whom I have seen practice high levels of agency within other contexts, return to passive patterns when meeting text work; as if cultural paradigms of power are embedded in the words themselves. What is specific about this situation; is there something particularly complex about agency and text?

This analysis draws on the author’s research as pedagogue at the Norwegian Theatre Academy with students of diverse backgrounds. It traces agency from the overarching institutional context to the specifics of studio exercises: acknowledging these as interconnecting systems which affect each other. To consider what agency ‘means’ in a moment of performer training, I must take into consideration how this is supported or contradicted at various levels of the world and institution in which that performer ‘performs’.Footnote1

The article proposes a trans-aesthetic approach which foregrounds agency as primary mode of learning. It contributes to the field by developing an analytical strategy of overlay and simultaneity: exploring how different methods co-exist. This draws theoretically on intersectionality (Crenshaw), multivocality (Meizel), worlding (Spivak), intra-action (Barad) hybridity and the bodyworld (Camilleri). This is distinct from approaches which (re)consider or deconstruct in order to find fault or update. This approach aims to create models of multiplicity, on the level of method and ontology, which support diversity within a student/performer group.Footnote2

The practical examples are organized into conversations, training and compositional invitations for the classroom. They outline a way of working beyond binaries of traditional/experimental, agency/passivity. The conversations are grounded in Camilleri’s notion of a hybridity continuum, (rather than hybridity as a ‘meaningless universal soup’ Pieterse in Camilleri, Citation2020, 18), a continuum which acknowledges the intra-action (Barad) of materials and a multilateral flow of agency.Footnote3 As provocation for uncovering assumptions, I propose a terminology, considering bodies as texts and texts as bodies. Training and composition exercises include: exploding the text, code shifting, aesthetic hybridity, glitching - all as examples of sonic world-making.

Institutional perspective: agency and privilege

When reflecting on ‘agency’ within the context of university training, one is already reflecting on a select few: those who passed the audition. Even acting educations like the Norwegian Theatre Academy, which aims to accept and support a racial, neuro and physically diverse student body, are often elitist endeavors: we accept maximum 14 students every 3 years. As Maxwell and Aggleton in Privilege, Agency and Affect reflect:

Much of our recent work has been focused on young women from relatively well-off backgrounds, who are engaging in the process of developing subject positions and imagined futures within the ‘bubble’ of private education in England…this work has required us to think carefully not only about ‘what is agency’, ‘how can it be observed’ and ‘how is it narrated’, but also about the dynamic between privileged subject positions and/or the inhabiting of privileged spaces, and possibilities for, and the outcomes of, agentic practices (2013, 1).

How do pre-existing conditions which limit agency in life, affect how students meet studio exercises? For example, in Norway, they have recently introduced high student fees for non-European citizens, while Norwegians pay nothing and receive government grants for housing. When offered the ‘agency’ to choose text to work on in the classroom, do the non-Norwegian students choose based on what interests them, or do they use it as a chance to work on a monologue which might get them a job at a well-paid theatre? Questions of ‘agency’ connect to some of the key concerns of performer training in our time such as empowerment of marginalized voices, intersectionality and anti-discriminatory practice. In privileged contexts, such as many acting conservatories are, narratives of agency, cannot be about gaining ‘more’ agency or a louder voice, but must speak to the specificity of the students present, acknowledge the relationship between agency, power and hence responsibility, explore strategies and critical reflection which unpack the complexity of having choice.

Trans-aesthetic training as frame

Zooming in on the university studio: what frame makes space for agency-driven learning for a diverse student group?Footnote4 As Gordon problematized in The Purpose of Playing:

Most actors today are trained according to the one method favored by their particular […] school. Most often the specific approach is not taught in a conscious or critical process, but is absorbed experientially by the student as a unique set of practices […] Problems occur when […] actors are asked to create performances utilizing techniques and stage conventions other than the ones in which they were schooled. These problems arise not merely because actors are unfamiliar with the alien conventions and techniques, but also because their performing identity has already been formed by the aesthetic they have unself-consciously absorbed in training. (Gordon, Citation2006, 2)

principles and practices inside of my body/voice can be understood in reference to each other; each tradition becomes an embodied context for learning the praxis of another tradition. Through trial and error as well as strategically designed interactions, the different trainings inside of me can interface. These combinations create different body knowledges from which I am able to develop alternative methods and models for training…. (2009, 174)

articles on overarching principles (Behrens Citation2016), an intercultural approach to text work (Behrens Citation2016), an ethical approach to song (Behrens and Berkeley-Schultz Citation2017) and a spatial approach towards training as holistic practice (forthcoming) […and] a materialist approach to voicework with a focus on sound. (2019, 396)

Terminologies: bodies as texts ⇆ texts as bodies

Bodies and texts are two entities, which are often assumed to be definable materialities; they are touchable, readable, have edges, are finite. What if, instead, we consider the immateriality, fluidity, hybridity or constant approximations of these bodies/texts, that they are both, in different ways, never fixed and always in a state of becoming. As glitch feminist Legacy Russell writes, the ‘dematerialization of the body’ is a way towards empowering beyond the limiting categorization of binary gender (2016/17, 1). The underlying wish here is to forward an argument of resisting interpretation – that neither a body or a text is one ‘truth’:

Responding to Donna Haraway’s proclamation, ‘I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess,’…Gill Kirkup asks, ‘[But] is it better to be a cyborg than a woman?’…Glitch Feminism answers to this today with a resounding ‘YES!’ Haraway’s cyborg premise revolves around ‘…the struggle for language and the struggle against perfect communication, against the one code that translates all meaning perfectly, the central dogma of phallogocentrism’; thus the (de)coding of gender becomes as much about how it is constructed, as whether it can or cannot be read… Judith Butler observes in her Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative, ‘One ‘exists’ not only by virtue of being recognized, but…by being recognizable.’… Let us make space for ourselves by broadening the realm of the unrecognizable (2016/17, 1)

In terms of teaching, the first invitation for students when approaching text, is to dialogue around these terms; to practice talking, before doing. As mentioned, when performers start to speak text, unconscious assumptions and patterns often manifest quickly. Talking conceptually, first, allows groups to unpack these received ideas and to offer them alternative modes of thinking, which they build together.

Conversation 1: bodies as texts

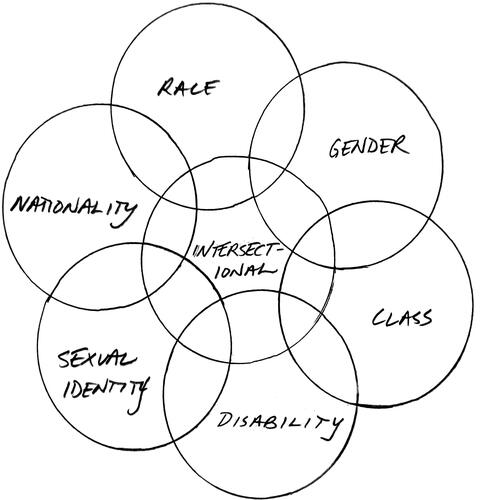

Our body is always being ‘read’ by visual signs perceived from the outside: it is different to be ‘read’ as a black woman or white woman, still different to be read as a black queer woman, and the experience of being misread, is familiar to many. In terms of reading the body as text, the notions of intersectionality and multivocality offer two interesting images to consider. Intersectionality, originally coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw 1989, came from a very specific need: to explain and expose patterns of discrimination for marginalized communities. This model gives an image of the body and identity that is multiple: the self is potentially fragmented or merged, dislocated or hidden, rather than the narratives of ‘purity’ of identity or presence which exist in some Western centered actor trainings ().

Meizel’s notion of multivocality, the idea that we all have multiple voices from which we speak, for example, offers another metaphor, this time specifically in relation to the voice. The increasing number of individuals whose backgrounds include a variety of nationalities and socio-cultural backgrounds, begs the question of how these bodytexts might take agency when working with a text.

In terms of how we envision the complexity of the bodytext, I keep returning to Tomsha’s evocative quote and Katrin’s reflective comment:

I am not ‘half Japanese’ and ‘half Lithuanian Jewish.’ When I’m singing a Japanese folk song, I don’t sing with half my voice, but with my whole voice. When I’m taping together my grandparents’ Jewish marriage contract, worn by time but still resilient, it’s not half of my heart that is moved, but my whole heart. I am complete, and I embody layers of identities that belong together. I am made of layers, not fractions. – Yumi Tomsha

It’s colonization that seeks to break us into pieces. (Kim Katrin facebook post Nov 10, 2018)

Conversation 2: texts as bodies

Texts, just like bodies, are often considered as singular, fixed, black and white on the page. To consider text as a body, is conceptually, a way to consider a text not as an inanimate object which can either be worshiped or deconstructed, but rather as a fluid ‘being’ created from a complex historical moment and whose meaning shifts in relation to its current context. In this sense, a Shakespearean text does not necessarily ‘belong’ to Elizabethan times, which would make an interpretation based on this positionality most ‘authentic’, but it rather intra-acts with the body that speaks it to generate a range of different meanings. In this context, it is relevant to remember how many texts in current circulation in drama schools privilege a white cis male perspective; it is often a struggle for those not identifying as such, to find texts written from perspectives and by authors which mirror their own intersectionality.Footnote7 As Anna-Helena McLean reflects, one way to approach language is to acknowledge the deeply embedded bias within it, ‘In the same way women, and other marginalised identities, are categorised and reduced to ‘fit into’ and perform their othered roles in a phallogocentric, linguistically prescribed society that they haven’t been given licence to contribute to, own or have very little real agency within’, she suggests positioning one’s self toward language like putting on a kind of drag, as a way to find agency within a textual body which has, in a sense, written you out. (personal conversation, January 2024).

As discussed, I propose a trans-aesthetic approach. I do not introduce methods as a hierarchy (Laban as preparation for Chekhov), but rather allow them to stand next to each other and overlap, much like the circles of intersectionality. Practically, this might mean working with Meisner one week, Viewpoints the next and Stanislavski after that. The provocation is to critically reflect with a student group on why and how different exercises allow different voices within the text + their body, to emerge or retreat.

In, for lack of a better word, ‘traditional’ text work, the practice is often started with text analysis, a process of a human unpacking and/or deciding what a text might mean. This can be connected to the literal meaning of the words, a consideration of character, the power of the poetry in the structure of the writing as well as many other elements. As I have written about elsewhere, text, singing and sound based trainings are often done separately, ‘as if’ they are distinct trainings even when they are all executed by the same voice. In my work I try to destabilize how students understand that text can ‘make meaning’. Very simply, this means suggesting that a text is still ‘itself’ and makes meaning even if we cannot understand the words: just like an individual is not only their race or gender or other symbolic markers we might ‘read’ on first meeting or privilege as more important.

How can I invite exercises which unlock these different kinds of meaning? Working with the text as text, song or sound, is one place to start. I would suggest that intersectionality and multivocality describe different notions of what Camilleri terms bodyworlds, with a particular focus on how the individual experiences themselves. Significant in this discussion, is the context of performance, and the openings offered therein, for disturbing normative bodyworld patterns and making space for different material interactions. In working with performers, it is important both to help them articulate the texts already existing in their bodies due to their intersectionality, but also to invite for generative play: how might they employ the performative frame to find fluidity with these different identities? In my reading of Camilleri’s bodyworld, McLean’s invitation regarding language as drag is a great example of how a performer can take agency and ethically ‘play’ with their intersectional identity within the fluidity offered by the performative space.

Lastly, I want to touch upon strategies of deconstruction when applied to text. Spivak’s notion of worlding is ethically important. She argues that the West was able to create narratives of, for example, the Third World, via promoting an idea that there was ‘nothing’ there before that world was ‘created’ by the West. This justifies the colonial impulse. In terms of the performer exploring agency in terms of both their own bodytext and textbodies they work with, there are important ethics to consider. In postdramatic text work there are many methods of deconstructing text, treating it as ‘material’ in the sense of something that can be cut up (literally), rearranged etc and that this is justifiable in the name of art. Historically, this tearing up of a ‘body of text’, is a reaction to the almost holy attitude towards the text that is a narrative in some character-based acting methods and has sometimes been an empowering reclamation and means to re-insert silenced voices within normative narratives. The postdramatic impulse cannot, I would however argue, be employed as a ‘carte blanche’ for the justifiable deconstruction of all texts; this would be to mirror a colonialist impulse, that a text is a ‘nothingness’, waiting to be colonized. Considering a text as a body, reminds us of the ethical considerations of deconstruction; what body would I tear apart? I wonder about a third way, an approach to text that employs an ethical understanding of the historical complexity of any text or body and that this is part of the performer’s reflection as they work and compose.

Agency on the floor: unpacking presence

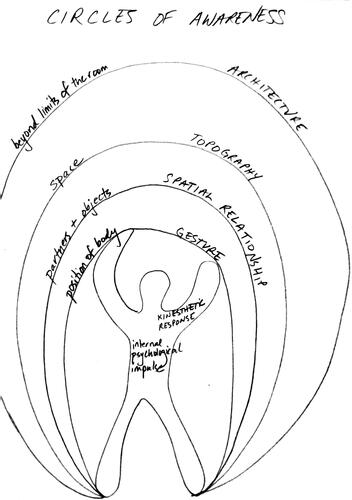

In the previous sections, I have discussed how to open up the possibilities inherent within texts and bodies and aim to awaken students to the ethical complexity of working with agency. Now the question becomes, how to ground these concepts in practical exercises? In the next two sections, I will start from some training exercises/images familiar to many drama students, and dialogue them with the previous conversations, to explore how presence can go from singular to multiple, human centered, to a human-nonhuman hybrid. Historically, I would argue that one of the ground principles for understanding ‘agency’ in the embodied work of the performer, is the research that has been done on understanding presence: firstly the performer needs to become present in the moment, in order for them to practice agency and choice. I look at Stanislavksi’s Circles of Attention and the Viewpoints of Space and Time as two fundamental exercises that root their respective traditions in a notion of presence.Footnote8 These images/principles offer a specificity of presence in relation to ‘things’ and ‘a world’ that make them an interesting starting point for further overlays.Footnote9

In Stanislavski’s Circles of Attention, a performer practices extending their attention, like the circumference of a light beam, first to their own body, then to the floor, the objects in the room and finally out to the walls. Notably, within the context of theatre with a fourth wall. In ‘Vocal Action’ I write:

I updated Stanislavski’s circle of attention, extending the circles beyond the stage and shifting ‘attention’ to ‘awareness’ … This allows me to talk about the necessary opening or narrowing of the field of awareness which a performer does as they shift aesthetic logic, without using terms that have an aesthetic connotation. More fundamentally it defines presence relationally rather than as any kind of objective experience. (ibid, 81)

Expanding agency

Both of these methods, Stanislavksi and Viewpoints, understand presence and afterwards agency, from an anthropocentric, or ‘I’ centered perspective: the ‘I’ alone has agency.Footnote10 What happens if we overlay the text⇆body conversations on these exercises? What happens if we consider agency as a field of choice/change available within a performative or training moment: that performer and text can have and share agency?

Camilleri’s bodyworld and Barad’s intra-action offer an extension of these ideas.

Camilleri writes:

The post-psychophysical updates the notion of an integrated bodymind in various ways, including via the concept of ‘bodyworld’ to capture the actor/performer’s engagement with her performance material. By ‘performance material’ I refer not only to the practitioner’s psychosomatic and aesthetic processes (i.e. ‘material’ as score) but also as it emerges from the sociomateriality of her situated milieu (i.e. the impact of/on the material world), including as it incorporates technology in the broad sense that admits objects, tools, and clothing in addition to machines and digitization. In this way, the idea of bodyworld reaches beyond that of bodymind which, by the very terms of the latter’s neologism, is human-centric and excludes anything extraneous to the human body, and which is thus not equipped to account for the roles played by the world-around-us. (2020, 157)

Most scholars consider living humans to be the only agents with their fingers on the puppet strings of otherwise inanimate objects and otherwise inanimate people – not the other way around… the ‘other way around’ perspective is at least in part what the new materialism is reevaluating … (ibid, 10)

Intra-action is a Baradian term used to replace ‘interaction,’ which necessitates pre-established bodies that then participate in action with each other. Intra-action understands agency as not an inherent property of an individual or human to be exercised, but as a dynamism of forces. (2007, 141)

Furthermore, intersectionality invites another perspective on the self as material. Imagine overlaying the Circles of Awareness and the circles of intersectionality. In Circles of Awareness, the body is depicted as a singular and fixed thing at the center of shifting contexts. The information offered through the circles of intersectionality, I would suggest, invites a complexification of how self meets world – how an individual experiences their sexual identity shifts radically in terms of how they relate to spatial relationship, objects, gesture, their own inner landscapes. This overlay makes present, via specificity, the non-neutrality of presence and thereby also the responsibility of agency and action.

Training invitations: hybrids as layered wholes

In this next section I will outline some training invitations. These will not be in the form of step-by-step exercises, but rather as speculative sketches which identify key areas that practitioners may explore. In terms of setting up the training space, it is important to articulate that the performers are dramaturgs/devisers as much as they are embodied performers. Zarrilli writes:

The term ‘dramaturgy’ refers to how the actor’s tasks are composed, structured, and shaped during the rehearsal period into a repeatable performance score that constitutes the fictive body available for the audience’s experience in performance […] The actor’s performance is shaped by the aesthetic logic of the text and the production per se as it evolves in rehearsals […] Post-dramatic performances often require the actor to develop a performance score that has multiple dramaturgies. (2009, 113)

Practically, I often divide my course time in two halves, the first part being focused around exercises which research the textbody and bodytexts in the room and their meeting points, and the second around building and rehearsing material. In the first half, I as teacher have more agency, choosing exercises and readings. In the second half, I decenter myself, allowing the student to make choices about their own work, I become tutor. In terms of the ethics of equity, I suggest that everything we do is a performance – there is no exercise that is ‘just’ an exercise or preparation for anything else, but rather each of these explorations we do can be, or already is, a seed for a full aesthetic world.

One exercise I often start with is that the students say their whole text on vowels, and then, in a second round on only consonants. This is a tried and true technical exercise often used in singing, to help singers open up the trajectory of vowels in a song. Likewise, it is used often as preperatory work in Shakespeare textwork in order to find out the ‘inner state’ of a character. Juliet’s ‘Gallop apace’ monologue, in which she anticipates the coming of Romeo and the loss of her virginity is full of ‘o’ ‘o’ ‘o’. My proposal is to work this exercise, not as a technical exercise, but as a one-to-one performance. The student is invited to take time with each vowel, to feel the space it makes inside, to stretch it, extend it etc and then move to the next: to find the action within each and explore them as an energetic trajectory. After the performance, the witness feeds back on what they heard, associations, sensations etc. Then the performer responds and they have a small conversation. Some students have taken this exercise and used it as a base for a final performance – working completely without spoken words, but rather returning to the sonic impulses ‘before’ the words, the text’s ‘soundbody’.

Another interesting area to open when exploring the multiple bodies of a text is the question of language. I have a series of exercises that work with the range of different meanings that arise when a text is, for example translated from one language to another. Reflecting with students on why a text ‘says one thing’ in one language and ‘something else’ in the second language, can be a fruitful destabilizing of the perceived informational meaning of a text. Working with students from Singapore, some reflected how they had some languages which felt ‘private’, the language they only spoke to their grandmother and other languages they used to perform or speak in the streets. In other national contexts, this might be relevant in terms of accent. The frequency of individuals who can speak two languages or more is only increasing; multilingualism and also hybridity of language is a highly topical area worth exploring in text work today. As some of my NTA student remarked, there are also interesting power dynamics at play when one consciously chooses to work in a language that they know the audience will not understand, or which only some of the audience will understand. For example, Maritea Dæhlin, a Mexican born multilingual performer, chooses to always perform in Spanish, even in Norway. She says that she chooses to assume that there is someone there who speaks the language who can translate. And that it is politically significant for audience members of a dominant language group to have the experience of ‘not understanding’ on the level of what I call ‘informational meaning’.

Compositional explorations: impulse, hesitation and glitching as gateways

After exploring different textbodies via some of the mentioned exercises, I invite the students to develop one of their explorations towards a repeatable score. As mentioned, one example is the option to work ‘only’ with the soundbody of the text. Another example would be of course to explore how, within one text, you might shift from one way of making meaning with text to another: a hybrid. One example of this, might be working between two different languages within one text. In ‘Training a Performer’s Voices’ I write about ‘exploding Chekhov’, an approach to interrupting the written textual flow, with sound (2016). Another might be to work with how the written text might be interrupted by a meta layer which allows the performer to intersect the text with their own thoughts, bringing their intersectionality more present in the room. The image of glitch, from Glitch feminism, a mistake that becomes a site of agency, seems extremely resonant:

glitch has been used pejoratively, its etymology is rooted in the ‘…Yiddish glitch (‘slippery area’) or perhaps German glitschen (‘to slip, slide’); it is this slip and slide that the glitch makes plausible, a swim in the liminal, a trans-formation, across selfdoms.’ [glitch – my insertion] ….may not, in fact, be an error at all, but rather a much-needed erratum… Glitch Feminism is therefore ‘activated by the accident’. (Russell Citation2016/17, 2)

These questions of composition, connect very much to the positionality of the performer as deviser or dramaturg. One conceptual framework I would offer here as potentially useful, is the question of – how to find these moments of explosion, rupture or insertion, in a way that links them back to the psychophysical work of the performer: so they don’t simply become conceptual experiment. Returning to a notion of acting as a cycle of action-reaction, which Stanislavksi introduces. Merlin, in The Complete Stanislavski Toolkit specifies that within the category of ‘impulse’ there are actually 2 small actions – a physical reaction, or what would be in Viewpoints considered kinesthetic response, and then a small choice made by the mind. These happen almost simulatneously – but not completely.

Many voice methods train the performer to respond instinctively with voice. This is often described as bodymind integration or psychophysicality. This is an important aspect of the work and all that is needed when the next ACTION (i.e. the words the performer will say), is pre-determined – the performer’s relation to the moment needs only to help them choose how to shape the words, not what the words are. For the composing performer, the fact that the moment of REACTION is made up of two parts (body and mind) has significance. This moment of the mind is the moment in which the performer is composer. During the inbreath and outbreath, the performer must be the embodier, the one who does, with full belief in what they do – it is a moment ‘inside’ a single culture of performance. The moment of the mind, however, is the moment of choice, the moment when the performer decides to sing instead of speak the next line, or to look to the audience silently. This happens in the moment of suspension between one breath and the next. Like a pendulum which is difficult to push off-course during the downswing but easily diverted to a new path when it is at the apex, this is the moment of release and listening in which a gentle thought can redirect an action. (Behrens, Citation2011, 58)

Cahill and Hamill write about the productivity of hesitation as a strategy for working beyond our socio-culturally received patterns:

Developing more just habits of receiving a wide diversity of vocalized sounds…will require significant experiences of hesitation, disruption and discomfort…Such…hesitation may involve…disorientation, but … disorientation can be a productive element of moral agency, particularly in the context of sustained structural inequalities. (2022, 81)

Conclusion

This article aims to provoke the question of agency in relation to text work within the frame of ethically reflective performance work with devising performers. To contribute to methods for performers to work simultaneously as psychophysical embodiers of text as well as composers of material. Ethically, it proposes an approach that resists interpretation, grounded in trans-aesthetic methods which invite agency for human and non-human agents. Looking forward, I hope these approaches can further productively complicate questions of ownership and history in written language and allow students from a variety of backgrounds to engage proactively with pedagogues about the ‘truths’ of text and make space for ‘their own’ modes of speech.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Electa Behrens

Electa Behrens (USA/Norway): works as the Program Responsible for the BA in Acting at the Norwegian Theatre Academy. She is a performer, mother, theorist, teacher. Phd: Kent University, MA: Exeter University, BA: Vassar College (theatre&anthropology). Her work explores voice as a way to be in, build and deconstruct worlds. She has written on voice and: touch, darkness, composition, decomposition, presence, action, intersectionality, agency, ethics and space. She has worked with, among others Odin Teatret (DK), Richard Schechner (USA), Marina Abramovic (Serbia), Dah Theatre (Serbia) and the Centre for Performance Research (Wales).

Notes

1 In the forthcoming book chapter, ‘Singing Pedagogy for Actors: Questioning Quality’, co-authored with Øystein Elle, I further discuss how the institution and studio intra-act.

2 This references the notion of ‘communities of disagreement’, coined by Iversen, which posits that a truly inclusive society needs to find models which support dissonance, rather than integration as agreement or singular narrative. This is further explored in the forthcoming chapter ‘The Ethics of Ensemble: Safe, brave and accountable spaces and communities of disagreement’ written in conversation with Ditte Berkeley, bradley high, Anna-Helena McLean, and Ian Morgan.

3 Camilleri was co-editor of a Performance Research Issue: On Hybridity (2020), which investigated: ‘the intersections between hybridity and performance as the coming together of performer and environment, materials and practitioners, performance and reception, event and analysis. Thus understood, hybridity is at once a formative, trans-formative and performative encounter that shapes performance and culture on many levels: as pedagogical process, as compositional and production strategy, as ensemble and assembly (human and nonhuman), as inter- and intradisciplinary endeavour, as a policy and as inter- and intracultural phenomenon. (Camilleri and Kapsali, p. 2).

4 Trans-aesthetic’ does not here refer to the aesthetics of the trans community. Neither, does it, however, simply mean an approach which works ‘across’ aesthetics in a simplified sense. This term attempts to identify a practice in which a performer works in the liminal in-betweens, with an understanding of the non-fixedness of any ‘aesthetic’, person or method. In this sense it is in keeping with trans aesthetics in the first sense mentioned, as an approach dedicated to fluidity and aiming to resist reification into a singular ‘thing’. For those in the trans community, I apologize for any confusion and hope that this term can offer something to the discussion in its resonances and dissonances.

5 I have a practice in my teaching of using sketched images as a teaching aid for definitions and images. Even when printed images are available, I choose to make my own drawings – and usually redraw each image each time I teach. This allows me to add small comments specific to each group and to highlight the transience and approximate nature of any definition –all theories and images that are now seen as fixed and final, were once an idea scribbled on a napkin.

6 See ‘Voice (as and in) Touch’ for examples of this quote as starting point for embodied exercise.

7 Latinx Actor Training by DeCure and Espinosa is an example of a monologue book specifically for Latinx performers, aiming exactly to redress this lack.

8 Viewpoints was originally developed by Mary Overlie and popularized by Anne Bogart.

9 This proposed methodology of overlays does not suggest or aim for a ‘perfect match’ of translation of terms. Instead, much in the same way something is lost in translation from English to Norwegian, the invitation here is to look for the productive overlaps while acknowledging and learning from the dissonances. This again returns to a notion of integration, or how body knowledges interface, not as a aim for sameness, but rather a dynamic liminal space which needs to be navigated ethically.

10 This may seem obvious in a Stanislavksian perspective. For Viewpoints, although the method appears to offer an equality between the viewpoints of space and time, I argue in my doctoral thesis that ‘rather than training nine equal interrelated principles, I contend that she actually trains kinaesthetic response within the other viewpoints. Architecture, for example, cannot be ‘trained,’ the walls are fixed. What her exercises actually do is put the focus on one or other of the Viewpoints as the stimuli which the performer becomes aware of and trains the ability to respond kinaesthetically to (2011).’ ‘She’ here refers to Bogart in her book The Viewpoints Book co-written with Landau.

References

- Ahenkorah, E. 2020. ‘Safe and Brave Spaces Don’t Work (and What You Can Do Instead)’. https://medium.com/@elise.k.ahen/safe-and-brave-spaces-dont-work-and-what-you-can-do-instead-f265aa339aff.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Behrens, E. 2011. ‘Vocal Action: From Training towards Performance.’ Unpublished PhD.

- Behrens, E. 2016. ‘Training a Performer’s Voices.’ Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 7 (3): 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2016.1222302.

- Behrens, E., and D. Berkeley-Schultz. 2017. ‘Songs of Tradition as Training in Higher Education?’ Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies 2 (2): 187–200.

- Bogart, A., and T. Landau. 2005. The Viewpoints Book: A Practical Guide to Viewpoints and Composition. New York: Theatre Communications group.

- Camilleri, F. 2020. ‘Of Assemblages, Affordances, and Actants – or the Performer as Bodyworld: The Case of Puppet and Material Performance.’ Studies in Theatre and Performance 42 (2): 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2020.1757320.

- DiAngelo, R. 2018. White Fragility, Why It’s so Hard for White People to Talk about Racism. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Gordon, R. 2006. The Purpose of Playing: Modern Acting Theories in Perspective. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Katrin, K. 2018. ‘I Am Not ‘Half Japanese.’ Facebook post Nov 10 2018.

- Maxwell, C., and P. Aggleton. 2013. Privilege, Agency and Affect: Understanding the Production and Effects of Action. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McAllister-Viel, T. 2009. ‘(Re)considering the Role of Breath in Training Actors’ Voices: Insights from Dahnjeon Breathing and the Phenomena of Breath.’ Theatre Topics 19 (2): 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.0.0068.

- Meizel, K. 2020. Multivocality: Singing on the Boarders of Identity. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Merlin, B. 2007. The Complete Stanislavski Toolkit. London: Nick Hern Books.

- Russell, L. 2016/17. On #GLITCHFEMINISM and The Glitch Feminism Manifesto. http://beingres.org/2017/10/17/legacy-russell/.

- Spivak, G. 1985. ‘The Rani of Sirmur: An Essay in Reading the Archives.’ History and Theory 24 (3): 247–272. https://doi.org/10.2307/2505169.

- Stanislavski, K. 1937. Elizabeth Hapgood Reynolds ed. An Actor Prepares. London: Methuen.

- Stark, W. 2016. Intra-action. https://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/i/intra-action.html.

- Zarrilli, P. 2002. Acting (Re)Considered: A Theoretical and Practical Guide. London: Routledge.

- Zarrilli, P. 2009. Psychophysical Acting. Abingdon: Routledge.