Abstract

The Bridge of Winds is an international research group founded in 1989 by Odin Teatret actress Iben Nagel Rasmussen. For thirty-three years, a core group of artists from 12 countries has met together annually, carrying out in-depth research into the actor’s craft. During these encounters, highly detailed psychophysical training is recovered and developed by the group, which feeds into performances, concerts and barters. The aim of this critical article is to reflect on the role of agency in the Bridge of Wind’s practice, drawing on field research carried out by the author in December 2021. It is argued that Rasmussen and her partners in the Bridge of Winds have re-envisioned laboratory theatre practice, allowing for an idiorrhythmic culture of practice to emerge that balances schema (fixed, fully developed form) and rhuthmos, (improvised, changeable form). Whilst the members of the Bridge of Winds are rigorous and disciplined, having inherited a laboratory ethos and schematic leaning grounded in the practice of Odin Teatret, there is a tenacious trace in their work of an idiorrhythmity that also allows for subversion, transformation and revolt. The group’s training, in particular, accommodates the reality of the older actor’s body, just as it enables younger arrivals to excavate a sense of bios. Thus, the essay will chart out the contours of a particular nomadic laboratory practice that advocates both individual agency and collective solidarity, serving as a creative touchstone and wellspring for its members.

Introduction

The Bridge of Winds is an international research group founded in 1989 by Odin Teatret actress Iben Nagel Rasmussen. For over three decades now, a core group of artists gathered by Rasmussen from around the globe has met on an annual basis in differing geo-political contexts to develop rigorous praxical research into the actor’s craft. During each encounter, a daily regime of psychophysical training developed by the group is revisited, alongside a repertoire of performances, concerts and barters that enable the Bridge of Winds to reach out and dialogue with the different communities they visit. Footnote1 The aim of this article is to reflect on the role of agency in the Bridge of Wind’s practice, drawing specifically on Barthes’ (Citation2012) notion of idiorrhythmicity – a model for communal life-practices that balances schema (fixed, fully developed form) with rhuthmos, (improvised, changeable form). It will be argued that the group’s training serves as a unique creative catalyst, nourishing and empowering members at different stages in their professional trajectories, accommodating the reality of the older actor’s body whilst enabling younger arrivals to hone a sense of energetic presence and scenic bios.

Morning training

It is December 2021. I have arrived at Camp Stendis, a former village school in a little Danish hamlet, to observe this year’s annual meeting of the Bridge of Winds. It is the first day of a three-week gathering, and the group members are all preparing for the morning training. The large windows at the end of the school hall look out onto the fields beyond. Snow falls from the sky as the actors finish their stretching and stand in a semi-circle in front of Iben, who is sat on a chair in the centre of the space. A sense of anticipation hangs in the air. Together, the actors sing the song Campanas del Sol, which initiates every training session, and then, as one organic whole, they begin the Wind Dance; the first of the five exercises, or energies, that constitute this approach to psychophysical training.Footnote2

The Wind Dance is composed of a three-step, ternary structure, fusing action with breath. The first step, taken on an exhalation, grounds downwards; the second step, taken on an inhalation, contains a vertical impulse, levering the body upwards, whilst the third step, taken on the same inhalation, is a transition enabling the steps to be repeated to the other side. These technicalities are not apparent, however, as I watch the members of the Bridge of Winds enact the exercise: I see a group of bodies in flight, dancing through the space with grace, rhythm, and ease. There is a supple fluidity and sense of play throughout, and an incredible collective energy cultivated as the actors react to one another, introducing small freezes and throwing actions into the exercise, retaining and directing energy into the space. As the actors move, Iben watches attentively, tapping her feet gently to the rhythm articulated by the actors’ collective breath. She remains silent throughout the sequence, only speaking at the end, giving succinct, technical feedback to the actors.

After about twenty minutes of different inflections of the exercise, including group work in circles and pair work accompanied by songs, the group segues into the next energy: Green. Whilst the Wind Dance defies gravity, Green explores the actors’ connection to the earth. Based on the basic walk of Noh Theatre, the group begins to move slowly with a sense of resistance, spines erect, knees bent, and hips fixed in place. Green is a deceptively difficult exercise, yet the actors transition with ease from the extroverted, explosive energy of the Wind Dance to this introverted, compact energetic state. It is as if they hover through the space, gliding ghost-like across the floor.

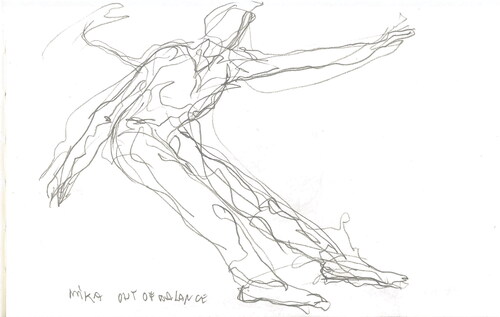

After some time exploring Green, the actors form a ‘mountain’; a clump of bodies in the space, and vocalise using a guttural vocal resonator grounded in the root of the body. One by one, they suddenly break out into the next exercise: Out of Balance. Technically, this is one of the most demanding exercises; the actors take their bodies into a state of imbalance, fall towards the floor and, at the last moment, block the fall with one leg, retaining the energy, which is then launched into the air with a throwing action in the opposite direction. The actors can then either move directly into another position of imbalance or ‘transition’ in the space, allowing themselves to be carried freely by the energy until the exercise is repeated. The expressive quality instilled is dynamic and volatile, as different bodies fall, recuperate, and launch energy explosively through the space, following individual tempo-rhythms and impulses ().

Out of Balance comes to an end as the actors form a second ‘mountain’, vocalising this time with a piercing, high-pitched vocal resonator. The group then moves onto the fourth energy: Slow Motion. This exercise is based on a slow, fluid way of moving with no resistance at all, as if the body were underwater or in outer space. The spine is the source of all action, as a steady wave of impulses flow from the actor’s centre into the extremities of the body. Iben uses the image of ‘seaweed’ to explain the energetic quality of this exercise, and as the actors move together, it is as if their bodies are rocked by the currents and waves of an invisible, energetic ocean.

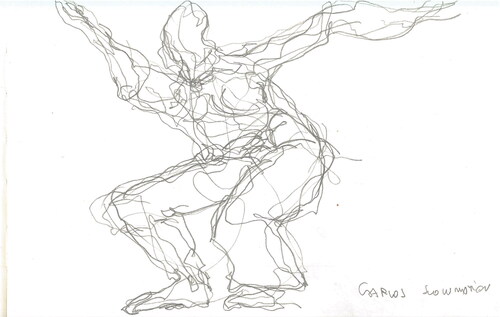

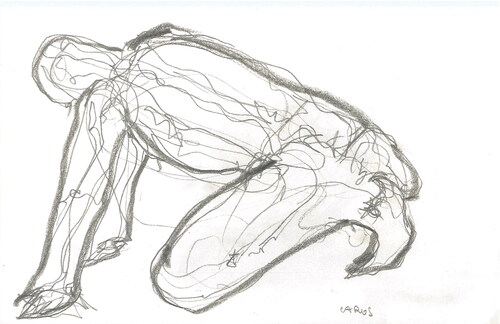

After some time, the actors transition into the final exercise: Samurai. Based on the image of a Japanese warrior, they enact a range of codified steps, maintaining the spine erect, knees bent and a low centre of gravity. The arms are positioned as if each actor held a wooden pole (which is initially employed whilst learning the exercise, to help the actor embody the correct posture) and the steps are interspersed with different modes of sitting and rising from the floor. The quality of this exercise is martial; the actors work with a precise visual focus, reacting to the actions of partners. At times, the bellicose Samurai is intercalated with the Geisha; a softer quality of energy, characterised by the segmentation of body parts and codified gestures evoking the world of the Japanese hostess. Towards the end of the exercise, the actors kneel on the floor one by one, coming to an organic moment of stillness. The session has ended ().

The Bridge of Winds’ training creates a unique energetic flow, enabling the actors to continuously modulate their scenic presence over the course of the hour-long sequence, both individually and in terms of their relationship to the wider collective. I am taken by the virtuoso enactment of the exercises, but also by a sense of openness permeating the work. The exercises are taxing, offering complex challenges, ‘knots’ that the actors unravel through their bodies in space-time: whilst the younger actors cultivate a potent level of dexterity and an extroverted energetic presence through the sequence, a number of the older actors explore the exercises in a reduced fashion that is no less beguiling and rich in complexity. I am struck by a dynamic in the Bridge of Winds’ training between structure and agency; the exercises as a pre-determined assemblage of forces and the space for idiosyncrasy they afford. To articulate this fruitful tension, I am drawn to Barthes’ writings on idiorrhythmity, and the dialectic he detects between schema (fixed, fully developed form) and rhuthmos, (improvised, changeable form), as a means of mapping out an artistic agency conditioned by the particular disciplinary structures and expectations of laboratory theatre practice.

Idiorrhythmity, rhuthmos and schema

What do we mean when we speak of ‘agency’? Are we referring to a pre-structural, essentialist vision of the foundational subject able to assert their own free will openly and without restriction? How does such a conceptualisation of agency sit with the poststructuralist notion of a decentred subjectivity, one founded and conditioned by pre-personal processes and structures of power related to sexuality, gender, race, ethnicity, abled-bodiness and class? Furthermore, how can agency truly emerge within a theatrical context, an artistic milieu also shaped by and dependent upon aesthetic discourses and paradigms, often spanning millennia? If agency is to emerge within the context of actor training, what possible shape might it take and how can we best frame and articulate such a phenomenon?

In Poststructuralist Agency: The Subject in Twentieth Century Theory (2020), Rae draws on the writings of Derrida, Deleuze, Foucault, Butler, Kristeva and Castoriadis to articulate how critical theory maps out the ways in which a conditioned subjectivity can still be permeated by lines of flight (in the Deleuzian-Guattarian sense of novel epistemes that allow for adaptation in relation to sociological, political and psychological factors), offering space for agential events. As he suggests:

My fundamental argument, therefore, is that rather than simply discard the subject as an effect of pre-personal relations or processes, poststructuralist thinkers, albeit in different ways, aim to depose one dominant form of subjectivity so as to propose another, with this alternative thought as a constituted effect of the ontological premises of poststructuralism (differential, multiple, non-essentialist and non-substantial, continuously becoming, and so on). (Rae, Citation2020, 17)

I do theatre because I want to preserve my freedom to refuse certain rules and values of the world around me. But the opposite is also true: I am forced or encouraged to refuse them because I do theatre. (Barba, Citation2000)

What should also become clear is that, in guiding the Bridge of Winds, Iben also encourages members to infuse the group’s fixed training sequence with personal discoveries, opening up to diversity whilst enabling older actors in particular to discover a tempo-rhythm and dynamic that accommodates the shifting capabilities of the aging body. Thus, she cultivates a space for creative dissensus within the group that allows for refusal and creative renewal. In order to better comprehend how agency may emerge on the micro-level of the Bridge of Winds’ psychophysical training, Barthes’ interlinked concepts of idiorrhythmity, rhuthmos and schema can provide a useful framework.

In How to Live Together. Novelistic Simulations of Some Everyday Spaces (2012), Barthes explores notions of space and daily life in monastic communities, contrasting the strict rules and regulations of coenobitic communitarian monks to other orders that followed an idiorrhythmic structure. This focus on monasticism is, according to Barthes, a way of articulating a fantasy, understood as a catalyst of forces and differences engendering culture (ibid). For Barthes, idiorrhythmity represents the fantasy of ‘something like solitude with regular interruptions: the paradox, the contradiction, the aporia of bringing distances together – the utopia of a socialism of distance’ (ibid: 6). Thus, Barthes is not interested in monasticism per se, but rather how the fantasy of idiorrhythmity manifests in different historical and literary forms, and what this tells us about a deep-seated human need to live together whilst maintaining agency and individuality.

Tracing an etymology of the term, Barthes draws on the original Greek concepts of schema and rhuthmos: whilst schema denotes ‘fixed form,’ rhuthmos indicates an ‘improvised, changeable form’ (idem). Hence, idorrhythmity (which adds the prefix idios, ‘personal’, to rhuthmus) represents ‘the interstices, the fugitivity of the code, of the manner in which the individual inserts himself into the social (or natural) code’ (idem). It indicates a certain level of agency in relation to extant structures and orders; an ability to follow one’s own path within a community of like-minded seekers.

In many ways, the tension between schema and rhuthmos, allied with an idiorrhythmic desire to create a space of creative agency, resonates with both the professional trajectory of Iben Nagel Rasmussen and the genesis of the Bridge of Winds, shedding light on this particular lineage of theatre laboratory practice. The short span of each annual encounter allows for a utopian ‘no-space’ to be established, one in which praxical questions can be foregrounded and more complex financial questions related to the maintenance of a permanent ensemble eschewed. In this sense, idiorrhythmity serves as a canny logistic tactic, ensuring both the economic viability and lasting endurance of this particular theatrical collective.

Iben Nagel Rasmussen and the Bridge of Winds

Iben Nagel Rasmussen joined acclaimed theatre laboratory Odin Teatret in 1966, going on to perform in 30 of the group’s performances and work demonstrations over a 56-year period.Footnote3 The rigour and discipline of the Odin’s approach to actor training and scenic montage offered her an initial artistic framework, a schema, that importantly taught her to think through the body. When Iben joined the group, Odin Teatret’s training was collective, and based on exercises developed by Grotowski’s Teatr Laboratorium in Poland, as well as elements of gymnastics, yoga and ballet. The training was hard, requiring strength, dexterity and stamina. Whilst Iben was physically able to keep up with the other actors, she could not find the same energetic and affective connection to the work, the transparency that she witnessed in the practice of the older members of the Odin.

‘Transparency’ is a key word in Iben’s professional lexicon, denoting the energetic potency and transcendence of the ego that systematic psychophysical training can engender. It is as if the actor moves beyond the exercise as corporeal schema alone, uncovering a personal rhuthmos, a unique flow of organic impulses that permeates and transfigures the exercise, transforming it into a vehicle for personal revelation. Significantly, it was when Iben broke with the very schema of the Odin’s collective training itself, developing her own idiorrhythmic practice, based on different ways of sitting, turning, letting her body fall out of balance to the floor and getting up again, that she encountered this sense of flow and transparency for herself (Rasmussen, Citation2023). By developing her own form of training, known today as the Swiss Exercises, Iben asserted her own agency within the Odin whilst helping to revitalise the group’s practice. The other actors of the group subsequently went on to develop their own unique training practices, responding to their personal needs, as well.

Iben was also a pioneer in terms of pedagogy within the Odin: in the 1970s, at a point when Barba felt that admitting new actors to the ensemble was unnecessary, Iben ‘adopted’ three pupils: Karl Olsen, Toni Cots and Silvia Ricciardelli, taking on responsibility for their training, housing and living costs. Iben formed a group with her students, Hugin, and began working with them on creating personal dances: complex fixed scores of physical actions that reflected the individual physicality and embodied research of each young actor (ibid). Whilst Olsen left and Cots and Ricciardelli were eventually absorbed into the main Odin ensemble, this focus on personal dance would become a recurring feature of Iben’s pedagogic practice, reflecting the idiorrhythmic impulse inflecting her own personal training.

In 1983, Iben offered a month-long workshop in the Italian town of Farfa to a mixed group of actors. The extended duration of the session allowed her to pass on elements of her own training, including the Swiss Exercises. She explored these with the participants, investigating how to avoid injuring the knees by blocking the fall with one leg before reaching the floor; this was the genesis of the Out of Balance exercise, alluded to above. During this seminar, Iben also introduced the group of young actors to the personal dance methodology and the Samurai, an Odin Teatret exercise developed during a particularly rigorous period of the group’s collective training (Citationibid). The encounter was such a success that Iben gathered the group together in Denmark the following year, weaving their personal dances into a montage, Heridos por el viento. They went on to form a stable group, named Farfa after the location of the initial workshop gathering.

Iben was now in the unique position of having established a professional group within a group: Farfa developed a range of productions, touring and offering workshops and barters across Europe and Latin America. It proved difficult, however, to conciliate her responsibilities as an Odin actress with her role as director of Farfa, creating a range of logistic and personal challenges. Rather than a refuge away from the Odin, an idiorrhythmic space where Iben could follow her own creative impulses, she found herself trapped between two different schema: two groups requiring her input, commitment and energy. When Farfa eventually folded, Iben vowed never to give a workshop ever again.

Her decision was short lived: in 1989 she led a one-month seminar for an international group of eight actors. The focus was on training, and once again Iben found herself developing fruitful avenues for praxical research beyond the confines of Odin Teatret. Just as the young actors of Farfa had enabled Iben to hone the Out of Balance exercise, the Wind Dance emerged out of this new seminar, based on an exercise developed by Polish theatre laboratory Gardzienice, brought to the group by former member Caroline Bering. Iben explained in a private interview that the Wind Dance represented a collective development of the personal dances she had developed with the members of Hugin and Farfa previously: whilst these had taken a long time to develop and fix, the simple nature of the Wind Dance meant that a complex ensemble training practice could unfold relatively quickly (Citationibid). The Green exercise was also developed at this point: the name came from the green cloths that the actors placed around each other’s head, chest, hips and ankles in order to generate the desired quality of resistance (ibid).

Once again, the seminar context provided a fertile terrain for a new phase of idiorrhythmic research. The young participants were keen to continue working with Iben; she accepted, and they established a group: Vindenes Bro (the Bridge of Winds, in Danish). Unlike Farfa, this was not envisaged as a permanent ensemble, but rather a nomadic collective that would meet once a year for an intensive three-week period, to continue joint research together. In 1999, Iben set up a new collective, the New Winds, made up of young artists from Europe. This group eventually folded into the Bridge of Winds, increasing the size and complexity of the collective.

For 34 years now, the group has continued to meet annually, developing a consolidated, idiorrhythmic theatrical tradition. The members of the group are all renowned artists and pedagogues in their home countries and have transmitted the group’s training methodologies to generations of practitioners, particularly in Latin America, ensuring the reach and lasting impact of the practice.

The members of the Bridge of Winds

In a series of interviews carried out with the Bridge of Winds in 2023, I was able to gather different members’ experiences of the group’s artistic practice and ethos.Footnote4 Idiorrhythmity and the tension between schema and rhuthmos all came to the fore in the artists’ responses to the semi-structured questions posed, revealing an affective cartography grounded upon a sustained dedication to theatrical craft and a sense of deep loyalty to both Iben and the group as a whole.Footnote5 Key thematic concerns emerged related to ways in which a constituted subjectivity might also afford space for the emergence of agency. These concerns (such as diversity, age, youth, (inter)disciplinarity and the extended reach of training) guide the writing henceforth.

The training structure: embodied knowledge and idiorrhythmic agency

Carlos Simioni (Brazilian actor, founded the group with Iben in 1989) recalls that, when the exercises were first developed during the initial seminar in 1989, Iben would train with the group and then stop to correct them individually. Carlos recalls Iben’s touch on his body: something would ‘snap’ internally and he would automatically find the right posture. Iben was somehow able to transmit her embodied knowledge tacitly, with touch rather than words (Simioni, Citation2023). Thus, from the very beginning, the training has consistently represented an idiorrhythmic flight away from dominant, schematic modes of knowledge exchange based on the primacy of logos ().

The training sequence took its final shape after about 18 years. Before that, it would be a surprise which exercise Iben would indicate next and there was a laboratory attitude to the work (as they were still exploring each energy). For Simioni, this shift was useful because it created a structured dramaturgy akin to a performance and taught the actors how to measure their forces when moving from one energy to the next (ibid). In contrast, for Tatiana Cardoso (Brazilian actress and academic, joined in 1996), this shift within the group’s training away from a rhythmic, fluid approach towards a more schematic structure was experienced as ‘a cut […] something that inhibited my ability to improvise.’ (Cardoso, Citation2023). Over time however, she learnt that she could:

[…] open up a space that allowed for new challenges and nuances within each exercise. It was as if the training was no longer so ample in terms of possible variations but rather offered a deepening of the work: there was a focus on quality, now, instead of diversity. (Ibid)

Each exercise is linked to different principles, and we go on to research this away from our colleagues at the Bridge of Winds. When we meet up again, the structure is the same, but the substance of the work is diverse, because each one of us back home has a unique professional life, working in distinct ways and at different rates with diverse groups of people in differing cultural contexts. This obliges you to search and find novel expressive possibilities within the same language […] adding to the richness of our collective training together. (Rocca, Citation2023)

It’s an autonomy that depends on the other: on your colleagues, the exercises, Iben’s outside gaze. Today, the work with the Bridge of Winds has to do with this: each actor is offered a generous gaze, focused on our individual development and creative pathway. (Cardoso, Citation2023)

The training and diversity

Rodrigo Carinhana (Brazilian actor, joined in 2018) emphasises the multicultural makeup of the group. He suggests that Iben has a particular way of seeing diversity, which comes out of her experience of Odin Teatret’s border-crossing work (Carinhana, Citation2023). The idiorrhythmic nature of the group has allowed a range of people from different countries and continents to establish a lasting working relationship together, opening up possibilities for exchange both inside and outside the group (ibid). Luis Alonso-Aude (Cuban actor-director, joined in 2005) expands on issues of diversity within the training:

Searching for the wind and the connection between our bodies takes us away from our cultural contexts and differences. We are able to connect to one another in this shared experience of life, this place of immanence which is so removed from death and from life: it is this place that remains. This is the main thing that the training has allowed me to discover, and I think it came from watching Iben perform. When I saw her perform for the first time […] I saw that which she calls a transparent body: a body that was completely alive on stage without hiding anything. A poetics, of sort. (Alonso-Aude, Citation2023)

The training and age

The question of age is also key within the Bridge of Winds: a number of the group members are now in their sixties and continue to train alongside the younger members on an equal footing. Carlos Simioni explains that he feels he gained the ‘honours’ of the training from his youth: the essence of the exercises is rooted deeply in his body, and he can still keep the flow alive within the sequence because he trained rigorously into his fifties. Today, he bears the ‘energetic grace’ of a life dedicated to these practices (Simioni, Citation2023). Guillermo Angelelli (Argentinian actor – joined in 1990) has also responded praxically to the question of aging. The first energy that he learnt from Iben was the Samurai, but if he enacted this exercise today with the same energy that he had when he was 24, he would last for maybe ten minutes (Angeleli, Citation2023). He asked Iben if he could work with the image of an aged Samurai within the training, but also tries to recuperate something of the younger version. It has been fundamental for him to persevere with the training, despite age and infirmities, and he came to understand that it is not just a question of physical exertion: rather, the training represents a commitment to the present. The five energies cultivate a relaxed sense of alertness and a perceptive listening that is both internal and external. One of the richest aspects of the work for Angelelli is working with a collective rhythm whilst finding his own, unique line of actions, and this allows for different levels of physical dexterity over time (ibid).

Rafael Magalhães (Brazilian actor, joined in 1993) reiterates this point:

I have a structure within my body: 32 years ago, it took a different form. I recognise this form, through the exercises and the training, but 32 years have passed, and my physical body is different now. Time has made it other. But the pleasure comes from realising that the essence of everything you worked on is still inside of you. And rather than resting on your laurels, your body is troubled, and you are obliged to find an equilibrium between the reality of your body today and the form of the training from 32 years ago. It’s a positive restlessness, as it allows you to adapt the energy according to your present reality. (Magalhães, Citation2023)

The training and youth

There are several younger members in the Bridge of Winds, and the training appears to offer them a sense of empowerment, a phenomenological experience of expanded presence and an increasing ability to attenuate energy and cultivate the subtleties of theatrical craft. Sophia Monsalve (Colombian actress, joined in 2008) reveals that:

[The training] has changed, but not in the sense that it has diminished: rather, it has amplified, a lot […] Last year and the year before that, I felt very powerful. The Wind Dance is so nice because you can do it slowly and gently and still have this beautiful flow, and the steps and all the principles of the exercise are there, or you can be completely wild, flying around becoming a tiger! So, the exercise itself has a pretty wide range.

(Monsalve, Citation2023)

It’s endless pleasure, this way of working with energy. From the very start, this was what I loved the most: to work with energy in a room with other people – that also means presence and how to work organically and dynamically. It is something you cannot put into words: it’s really a flow and it’s endless. You are just a medium of the energy – perhaps it’s the most important thing you can learn in life […] when the energy runs through you, something comes from somewhere and goes through you and then goes somewhere else – to the audience or into the room, but you don’t own it. (Thomsen, Citation2023)

Understanding means being economic within the training. We use up a lot of energy, and it’s something I’m mindful of, because you can explode at the beginning and then at the end you don’t have any reserves left. This demands a different level of care and subtlety within the training. I think that the more you practice the more you discover the subtleties. You move away from the purely physical towards a level of sensitivity. It’s a pathway that I can begin to perceive that is beginning now after nine years within the group. (La Selva, Citation2023)

Training and its (interdisciplinary) application

The work on the five energies within the training develops a very particular sensitivity to the incorporeal materiality at the core of the group’s practice, allowing members to map out something of a nascent metaphysics of presence as manifest within this small theatrical tradition, predicated on analogies between the rhythmic qualities of different exercises and the elemental constitution of the natural world. As Sandra Pasini (Italian actress, joined in 1993) reveals:

The energy is invisible, but it comes from something that is very visible: the body. This combination was very interesting to discover. The training makes me feel this energy in different ways […] the Samurai for me is connected to earth, the Wind Dance is connected to air; Slow Motion, water; Out of Balance for me is fire. All of these images of the energies that I had in my mind and my body helped me later in work on characters.

(Pasini, Citation2023)

In a similar fashion, Mika Juusela (Finnish actor, joined in 1999) has learnt to apply principles of the training in an array of professional contexts back home (including text-based Drama). He feels that the members of the Bridge of Winds are not followers of some ‘cult’: rather, they each want to bring something to the group that is uniquely theirs (Juusela, Citation2023). Whilst, in the beginning, he was influenced by the aesthetic and professional ethos of the group, today his own practice retroactively feeds the way he approaches the group’s work, following an idiorrhythmic flow of des/reterritorialization, similar to the one described by Rocca, above.

Miguel Jerez (Spanish actor and archivist, joined in 2016) suggests that the training is a never-ending process, and that this is the challenge:

When you feel that you are starting to ‘get it’, Iben will say ‘no, it is too fixed’. It is a process of constant searching. You are training energies, rather than the body. You need to be very present and precise, and these qualities influence every level of the group’s activities. (Jerez, Citation2023)

The Bridge of Winds is not just composed of actors: the group is interdisciplinary in nature and includes artists from different fields. Thus, the training can be idiorrhythmically transplanted beyond the schema of theatre to a range of different artistic contexts. Founder member Tippe Molsted (Danish folk singer, joined in 1989) suggests for example, that the training is ‘[…] like a song; it changes over time and becomes a part of who you are’ (Molsted, Citation2023). Year after year, new details emerge. This is not a conscious process; rather, the energy cultivated through the exercises appears to have a life of its own. Whilst age and bodily problems play a role, every single day of training is different. For Molsted, each year a different energy speaks to her in the sequence, offering opportunities for rhythmic exploration and discovery (ibid).

Antonella Diana (Italian set and costume designer, joined in 1993) speaks from her perspective as a visual artist collaborating with Iben and the ensemble. She believes that the training has changed over time due to the impact of age: before, the training was pure physical energy, now it is based on the impulse within, the power of experience and maturity. She can see the actors’ experience in the space, which she describes as ‘an invisible language’ (Diana, Citation2023). The actors’ training stimulates her imagination in terms of how to interact with the collective through visual media: for example, she works with the notion of resistance inherent to the Green exercise in terms of how scenic objects and costumes can offer the actors ‘resistance’ (understood in this context as creative challenges that lead to unique artistic responses). For Diana, Scenography thus becomes a laboratory investigation; working with the group has been a creative training that has taught her how to serve the needs of different montages, developing her sense of observation and ability to help ‘release’ characters (ibid).

Elena Floris (Italian musician, joined in 2006) became aware of her connection to the group through her violin playing: she realised that she could touch the collective and change the flow of the training through her musical accompaniment, pushing the actors through the repertoire of exercises. She could shift the ‘mood’ in the space and get the actors to move with different expressive qualities. She often starts the training with the others and then sits out and starts playing: her symbiotic, idiorrhythmic relationship with the energetic flow of the collective – cultivated by entering and exiting the training space at will - has taught her a different level of concentration whilst playing (Floris, Citation2023).

Expanded training

Training within the Bridge of Winds is a macro-practice, informing all levels of the group’s work beyond the schematic sequence of exercises encountered each morning. Marcos Rangel Koslowski (Brazilian actor, joined in 2018) observes that the expanded activities of the collective – such as their montages, concert and barters – are also forms of ‘training’ for the Bridge of Winds: creative processes that generate experiences (Koslowski, Citation2023). Watching Iben work as a director and achieve so much from the ensemble in so little time has been revealing – she has a great level of mastery and her way of generating and fixing materials has been an important reference, influencing his work with his own theatre group, Nuviar, back in Brazil (ibid).

Iza Vuorio (Polish actress, joined the group in 1999) suggests that working and cohabiting with the group for over three weeks every year is a form of training in and of itself. ‘How to function in a group and listen to one another?’, she asks (Vuorio, Citation2023). Thus, the training is not just muscular – it is social and ethical. Whilst the yearly encounters are extremely enriching for group members, it is also a challenge to find a way to live and work together again after 11 months spent apart. A complex process of negotiation is necessary to ensure the efficacy of the group’s annual encounters and to maintain alive the idiorrhythmic, nomadic dynamic of the group over time.

The utopic space activated by the Bridge of Winds is fruit of consistent hard work on the part of the collective: it is the result of an ensemble ethos that obliges members to engage in constant dialogue, finding constructive solutions to new situations quickly and efficiently. This coalition building, both within the group but also with members of the communities in which the residencies occur, is an essential aspect of the group’s expanded practice, indicating its political valency and importance.

Conclusion

A creative refuge, the members of the Bridge of Winds cultivate a very different way of living together, one that is nomadic and temporary, establishing an idiorrhythmity that flies in the face of the patriarchal, normative, proprietary tendencies of our capitalist, neo-liberal society. Iben and the group have paved the way for rethinking theatre laboratory praxis in a more fluid, generous and sustainable fashion, foregrounding a unique form of collective creation grounded on the importance of individual agency, a personal rhuthmos that transcends the schematic context of a fixed ensemble.

In many ways, the Bridge of Winds exemplifies Barthes’ (Citation2012) notion of idiorrhythmity, as defined above: the group members all live a life of ‘solitude with regular interruptions’ – every year, they make the pilgrimage to meet with Iben, gathering around her like a North Star before scattering and returning to their home contexts. The constellation of the collective embodies the ‘aporia of bringing distances together’: the arch-alterity that underscores the group is the secret of their lasting bond, as it is their complementary cultural, artistic and professional differences that strengthen and nourish the collective year after year. Barthes’ fantasy of a ‘socialism of distances’ is made manifest in this like-minded community of theatrical (re)searchers, who consistently reconnect and reconvene, transforming the field of laboratory theatre in their nomadic wake.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Patrick Campbell

Dr Patrick Campbell is Senior Lecturer in Drama and Contemporary Performance at Manchester Metropolitan University (UK). His academic work focuses on laboratory and Third Theatre practice in Latin America and Europe. He is co-author of Owning our Voices: Vocal Discovery in the Wolfsohn-Hart Tradition, written alongside Margaret Pikes, and A Poetics of Third Theatre: Performer Training, Dramaturgy, Cultural Action, written alongside Jane Turner. Both books were published by Routledge in 2021. He is a Core Member of Cross Pollination, a nomadic laboratory for the dialogue in-between practices (http://www.crosspollination.space/core-group/).

Notes

1 Barter is a specific form of performative exchange developed by Eugenio Barba and Odin Teatret, in which the Odin share their group culture, founded on their laboratory practice, with the local cultures in the places they travel to. Barter is an instrument for creating human relations through art and has been a mainstay of the Odin’s practice since the 1970s.

2 A range of excellent analyses of the Bridge of Winds’ training are available in English, Spanish and Portuguese, penned by members of the group (vide La Selva, Citation2018; Silva, Citation2019; Monsalve, Citation2021 and Alonso-Aude, Citation2021). A documentary film, directed by the group’s resident photographer Francesco Galli, also contains precious filmed footage of the five energies: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vNRf41soIDY

3 Odin Teatret has been an emblematic theatre laboratory the mid-twentieth century onwards. Founded by Eugenio Barba in Norway in 1964, the group moved to Holstebro, Denmark in 1966, changing its name to Odin Teatret/Nordisk Teaterlaboratorium. To date, Odin Teatret have produced 81 performances, performed in 65 different countries, and have generated an array of performative tactics for cultural engagement and social activation. The group was responsible for establishing autonomous actor training as a keystone of the performing arts, and developed an innovative, expanded approach to pedagogy and knowledge exchange.

4 I carried out qualitative ethnographic field research with a focus on the Bridge of Winds in December 2021, observing a group Encounter in Stendis, Denmark. I later complimented this in situ research with online interviews with group members in 2023. Due to logistic issues, I was unable to interview group members Jori Snell, Annemarie Waagepetersen, Katarzyna Kazimierczuk and Francesco Galli, who have made an invaluable contribution to the group in their respective roles of actress, actress-musician, Assistant Director and resident photographer. I was also unable to speak with Emilie and Frida Molsted, children of Tippe Molsted, who were born into the group and continue to be members to the present day. Galli has published an insightful chapter on his role with the group in the monograph Book of the Winds (Citation2020), co-written with Iben Nagel Rasmussen.

5 Interviews were carried out online in May 2023, in English, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian. All translations are my own.

6 The term ‘incorporeal material’ is used here following Massumi (Citation2002), to refer to the flow of movement, affect and sensation – energy – that transcends signification, pointing towards an embodied, intersubjective level of experience of being-in-the-world.

References

- Alonso-Aude, Luis. 2021. Corpo Zero: energia e presença na construção do corpo teatral. Sao Paulo: GIOSTRI.

- Alonso-Aude, Luis. 2023. Interview with Luis Alonso-Aude. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 17 May.

- Angeleli, Guillermo. 2023. Interview with Guillermo Angelelli. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 1 May.

- Barba, Eugenio. 2000. ‘The Deep Order Called Turbulence: The Three Faces of Dramaturgy.’ The Drama Review 44: 4.

- Barthes, Roland. 2012. ‘How to Live Together.’ Novelistic Simulations of Some Everyday Spaces. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cardoso, Tatiana. 2023. Interview with Tatiana Cardoso. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 9 June.

- Carinhana, Rodrigo. 2023. Interview with Rodrigo Carinhana. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 1 May.

- Diana, Antonella. 2023. Interview with Antonella Diana. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 20 May.

- Floris, Elena. 2023. Interview with Elena Floris. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 12 May.

- Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Jerez, Miguel. 2023. Interview with Miguel Jerez. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 10 May.

- Juusela, Mika. 2023. Interview with Mika Juusela. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 9 May.

- Koslowski, Marcos Rangel. 2023. Interview with Marcos Rangel Koslowski. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 4 May.

- La Selva, Adriana. 2018. ‘Bridging Monuments: On Repetition, Time and Articulated Knowledge at the Bridge of Winds Group.’ In Time and Performer Training, edited by Evans, Mark, Thomaidis, Konstantinos and Worth, Libby. Abingdon: Routledge.

- La Selva, Adriana. 2023. Interview with Adriana La Selva. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 25 May.

- Magalhães, Rafael. 2023. Interview with Rafael Magalhães. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 16 May.

- Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Molsted, Tippe. 2023. Interview with Tippe Molsted. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 19 May.

- Monsalve, Sofia. 2021. ‘El puente de los Vientos: una pedagogía de la presencia.’ Estudios Artísticos 7 (10): 19–47. https://doi.org/10.14483/25009311.17511.

- Monsalve, Sofia. 2023. Interview with Sofia Monsalve. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 22 May.

- Pasini, Sandra. 2023. Interview with Sandra Pasini. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 17 May.

- Rae, Gavin. 2020. Poststructuralist Agency: The Subject in Twentieth Century Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Rasmussen, Iben Nagel. 2023. Interview with Iben Nagel Rasmussen. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 30 April.

- Rasmussen, Iben Nagel, and Galli Francesco. 2020. Book of the Winds Holstebro: Odin Teatrets Forlag.

- Rocca, Lina Della. 2023. Interview with Lina Della Rocca. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 25 May.

- Silva, Tatiana Cardoso da. 2019. ‘Vindenes Bro: um acontecimento diante do tempo.’ Brazilian Journal on Presence Studies. 9 (3): 1–30.

- Simioni, Carlos. 2023. Interview with Carlos Simioni. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 16 May.

- The Bridge of Winds:International group of Theatrical research led by Iben Nagel Rasmussen. 2016. [film] Directed by Francesco Galli. Interviews conducted by Virginie Magnat. Holstebro: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and Odin Teatret.

- Thomsen, Signe Gravlund. 2023. Interview with Signe Gravlund Thomsen. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 23 May.

- Vuorio, Iza. 2023. Interview with Iza Vuorio. Conducted by Patrick Campbell, 5 May.