Abstract

We are in a new landscape in performer training in the UK in 2024. Student and staff well-being has been seriously impacted by five years of covid-related and socio-political tension. This context has resulted in increased incidents of mental distress, and increased complaints concerning training techniques, peer oppression and materials covered. Moreover, we are working in a field where the students’ bodies and positionalities are the basis for their ‘work’. Actor Trainers are charged with developing the performance techniques of students by centring their identity and agency, whilst navigating the particular tension between wellbeing, comfort, and individual boundaries. Aligning myself with Thompson and Carello’s guide for ‘Trauma Informed Pedagogy’ (Citation2022); I reflect upon some practical approaches that may be taken to celebrate students’ positionality, recognise the impacts of trauma (in tutors and students) and seed self-awareness and agency for both through knowledge, understanding and resistance.

Keywords:

It is March 2023.

Last night I met with a Masters student online.Footnote1 They were clearly uncomfortable; they have up until now refused to have meetings with me, they have sent long, reactive, critical emails; they are struggling to work with their peers, arriving to class moments before the session starts to avoid having to converse with anyone; they are smiling broadly at everyone and being effusive in praise of their teachers, speaking very loudly or not at all. Like many students, this one has faced barriers to getting in the training room. The socio-economic pressure from the cost of a Masters qualification means that they are regularly working a 2 pm–10pm or 8 pm–4am shift in a supermarket to pay the bills. They have faced familial opposition to them being in Higher Education, and taking a qualification in an arts-related discipline that will ‘not lead to a specific job’. They battled a difficult application and audition process compounded by being a neurodivergent learner who experienced violent bullying at the hands of previous teachers. They are here at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama studying for a Masters in Actor Training and CoachingFootnote2 (ATC); they want to change the field to ensure their past experience doesn’t happen again. Now they are on the course, however, they are finding the discomfort and pressure exhausting and stressful: they are blocked, and flip between saying how much they want to be here and refusing to participate. As the Course Leader, I have been personified as the ‘institution’, and as the solution to their inner conflict: enemy and saviour.

Conversely, this morning I have been on the phone talking to a colleague about the way they teach Hedda Gabler. They say that the classes are making some students uncomfortable, and these students (some 3 or 4 in a group of 18) are refusing to engage with the text. The students say that they are ‘triggered’ by Ibsen. We discuss the fact that none of the students have reported or documented PTSD, and that the tensions appear to be surrounding characters that enact archaic ideologies. The complaints are causing a schism in the group between students who are excited to explore and understand patriarchal narratives and others, who feel they may be perceived as racist or misogynist if they say/do the wrong thing, some want to shut down the conversation because it is making them uncomfortable. My colleague and I spend an hour reflecting upon whether ‘the canon’ should/could/must be erased from the conservatoire curriculum, and what that would solve. We talk through the numerous ways this teacher has framed the text critically and how their approach doesn’t appear to ameliorate the emotions in the room; rather it compounds them. Pitting students against each other and creating a ‘hierarchy’ of outrage, which silences them all.

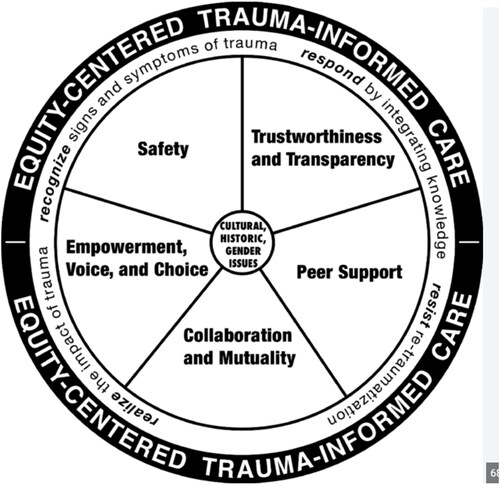

This essay looks at discomfort and trauma to consider the ways we may ‘scaffold’ learning for students and actors in such a way as to both ‘recognise the possibility of trauma in our [rehearsal] rooms’, and ‘develop pedagogical awareness’ of its patterns within students (Thompson and Carello Citation2022, 179). I frame my own teaching as one that benefits from constant and conscious engagement with Carello and Thompson’s Trauma informed Principles as a Wheel of Practice (see ). I argue that the language and recognition of trauma may become a new point of departure in Actor Training, and embodied knowledge of behaviours and biology can be woven into a student’s learning outcomes, so that they may have agency for their own learning, articulation and experience. The pedagogy discussed within this work can be applied with students of all types, the students I work with are trainee teachers, however, the ideas apply equally to actors, or undergraduates of many programmes. I invite you to recognise the students you teach, your own practice and the behaviours of your own teachers within this piece.

Figure 1. Trauma Informed Principals as wheel of practice (Thompson and Carello Citation2022, 17).

There has been a useful wave of ‘Trauma Informed Pedagogy’ articles, texts and blogs over the past three years (Brunzel, Stokes, and Waters Citation2019; Harrison, Burke, and Clarke Citation2023; Reddig and VanLone Citation2022), which propose that, (1) 66–75% of students report exposure to potentially traumatising events before they arrive in Higher Education,Footnote3 (2) Trauma impairs learning and therefore student agency, (3) courses that pertain directly to cultural identity are particularly vulnerable to students’ trauma being reawakened during training, (4) materials which cover difficult or uncomfortable themes in HE programmes need to be approached in a trauma informed manner, (5) people with protected characteristics are increasingly likely to have struggled with trauma and (6) college staff are increasingly experiencing burnout due to the increasing demands of pastoral care. Moreover, as articulated by Peter Zazzali (Citation2022), Lisa Peck (Citation2021), Anna McNamara (Citation2022), Amy Mihyang Ginther (Citation2023) and Roanna Mitchell (Citation2022), this is of particular concern for those who train actors because the actors’ hearts, bodies and minds are the ‘instrument’ through which they practice, and actors’ identities are ‘forever marked by their training’ (Spatz Citation2015, 158). Any conversation about agency, therefore, necessitates a consideration of trauma.

I align my approach alongside the one developed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and adapted by Thompson and Carello as a ‘wheel’ of practice (see ) (2022, 17). I allow the themes therein to destabilise my expectations of the conservatoire training context in which I train actor trainers. In so-doing I hope to highlight key points of tension within the fields of teaching and actor training and raise awareness of ways we might respond to students within this present time of change. I focus primarily on Thompson and Carello’s terms ‘resist, recognise and respond’ (the outer circle of the diagram) and then work through the tensions inherent when ‘safety, trustworthiness and transparency, peer support, collaboration and mutuality, and ultimately empowerment’ (the inner segments of the diagram) become live discursive and reflexive provocations within our pedagogy. My article forwards the premise, that a teacher supports a student to ‘recognise’ the signs and symptoms of trauma as a first step towards agency; and that a community, which is conscious of the difference between trauma and fear, who builds an atmosphere of transparency, can ‘respond’ to and sustain that agency through a career that ‘resists’ re-traumatisation (2022, 17).

Recognise, realise, respond

The parasympathetic nervous and adrenal systems regulate the embodied responses to being afraid, or in danger; they cannot be pre-empted or predicted. The five adrenal responses to fear are:

Fight, Flight, Freeze, Flop and FriendFootnote4. (PTSD UK Citation2023)

trauma is much more than a story about something that happened long ago. The emotions and physical sensations that are imprinted during the trauma are experienced not as memories but as disruptive physical reactions in the present (Citation2014, 206).

The adrenal responses are all present with the student I exemplified within the first paragraph. These cycles of high emotion and discomfort exhaust the student and exacerbate the pre-existing tiredness of managing paid work alongside studying. The responses go beyond quotidian adrenal system mechanisms and are a reaction to past experiences brought into the classroom. As soon as I recognised these as behaviours that typify a trauma response, I was able to look at ways to support myself and all the students moving forward. The behaviours impact upon us all in a myriad of subtle and dehumanising ways. The first tension that I must reconcile in my practice is that their trauma is not about me, and that I therefore need to reflect upon ways my teaching can amplify, validate, raise awareness of or diminish their stress and resist re-traumatisation in a move towards their agency. Recognising that one student is experiencing this reaction allows me to question the way I create an environment of safe, individuated community practice in response to their requirements.

Safety

According to Mays Imad, a key premise of a trauma-informed approach is to ‘work to ensure your students’ emotional, cognitive, physical, and interpersonal safety’ (Imad in Thompson and Carello Citation2022, 40). She advocates for a transparent conversation about what ‘safety’ means for the whole group, including the teacher/trainer, and for some responsive, and individuated oversight mechanisms to be put in place thereafter. Actor training, and its associated disciplines are particularly demanding; actor trainer Bella Merlin put it this way:

That [actors’] bodies, imaginations, feelings, intuitions and spirits are all part of the performative instrument as actors means that [actor training] is arguably one of the most vulnerable of all the performing arts (Merlin Citation2022, n.p.)

Moreover, I want to recognise the impossibility of a safe creative space. Angela Pao (Citation2010) and Claire Syler and Daniel Banks (Citation2019) discussed the way that the dramaturgical aspects of theatre can become the mechanisms for actor’s dehumanisation, especially within the aesthetic hierarchies of directors and teachers. Ben Spatz further suggests that discourses of power permeate training and teaching spaces, bolstered by the custom and practice of teachers who uncritically enact the regimes and systems that they were taught. He reflects upon the ‘powerlessness actors may experience when alignment of hegemonic acting technique and hegemonic cultural values allows… [teachers] to enforce stereotypes through the language of training or craft’ (2015,161). These insights recognise that there is no ‘safe’ space in theatre for students because ‘who determines what is safe and harmful dynamics of power get replicated in the request for safe space’ (Syler and Banks Citation2019, 213). Syler and Banks, and Angela Pao both advocate for a ‘brave’ rehearsal room. Without doubt, learning and especially embodied learning requires students to face elements that make them feel nervous or uncomfortable. A demand for bravery may, however, imply that students need to cross boundaries or submit to unequal treatment due to an unconsciously biased approach from a teacher or trainer.

For some, primarily for those with protected characteristicsFootnote5, the bravery needed to be in the room, and/or to enact specific tasks is different. Tema Okun’s Characteristics of White Supremacy asserts that ‘the right to comfort’ is a strategy for claiming power, Okun suggests that an antidote to this is to:

understand that discomfort is at the root of all growth and learning; welcome it as much as you can; deepen your political analysis of […] oppression so you have a strong understanding of how your personal experience and feelings fit into a larger picture; don’t take everything personally (2021, 8.)

One of the most powerful inhibitors to safety is desire. The students’ desire to learn, the students’ desire to please, and the students’ desire to succeed as an actor inhibit their ability to take time to recognise and check-in with their comfort and adrenal levels; be cognisant of how to process the biological information that is part of their training experience; be able to advocate for the time it needs to regulate their responses, or be able to advocate for a change in practice for fear of being seen as ‘difficult’ and therefore unprofessional. Moreover, the teacher’s own desire, born from their aspiration for ease, aesthetic or technique will also inhibit the ability of a student to check-in with their adrenal systems.

So, I start the ATC programme with the assertion that there is ‘no such thing as a wholly safe space’. I create a transparent political discourse within teaching and rehearsal rooms about the way people are identified, stratified, welcomed, or erased within culture and therefore training regimes; and the ways that desire brings us together, and can silence us. We create a reflexive dialogue around everyone’s safety. The student teachers become aware of what is making them feel nervous, and the way this may inhibit participation. Exercises can be framed towards individually conscious awareness of the desire to participate, and the fears associated with failure, judgment or memories of past experiences can be noticed, affirmed and attended to.

I set writing/articulation tasks for students to allow engagement with the tensions that they experienced within sessions. Robert Barton suggests that ‘[a] specific brief time period might be reserved each week for the entire class to voice concerns, identify fears, and acknowledge mind traps’ (1994, 115). Whilst I agree with Barton about the necessity for ‘voiced’ reflection, the curation of this needs to be attentive to the dynamics of a pluralist ensemble who will have a range of neurotypes, positionalities and cultures. Students must have time and space for concerns to be identified, and then be given choices as to how and when it is revealed, and to whom.

Trustworthiness and transparency

Mays Imad articulates the need to ‘foster trustworthiness and transparency through connection and communication amongst students’ (Imad in Thompson and Carello Citation2022, 40). Traditional actor training is a routine-driven space, where students are regularly asked to ‘check-in’ with how they are feeling, or where their bodies are holding tension. It is important for a trauma-informed practice that this scanning leads to students ‘taking what they need’ and advocating for themselves within the practice. Whilst it is important to scan for physical tension, it is also important to begin to check into adrenal system regulation or parasympathetic nervous systems and have a practical/practicable way of navigating this awareness within the sessions to cultivate communication between students and teachers. If students have been taught about the autonomic nervous system, then there is a clear lens through which to understand some of the feelings they may be having.

Moreover, there is a need for transparency and articulacy in relation to the community, and the different ways that ‘cultural, historic and gender issues’ (the centre of Thompson and Carello’s wheel) have been experienced by the group. This is where I differ from Thompson and Carello slightly, whilst I agree that positionality and past experience are at the centre of any pedagogical practice, I reject them being called ‘issues’. The term issues renders those of us with protected characteristics as ‘othered’ within their formation, and whilst stated above, the intersections of culture, history and gender directly correlate to a person’s likelihood of trauma; the issue is not at the heart of our pedagogy, their humanity is. An empowerment framework would place the recognition of someone’s positionality at the heart of the diagram. The first reading I mandate on the programme is David Takac’s essay How does your Positionality Bias your Epistemology? (Takacs Citation2003). This text promotes the way insights from peers from different backgrounds can support students to value what Kimberlé Crenshaw would call the ‘particularity’ of experiences in relation to cultural, historical and gendered positions without pathologising them (Crenshaw Citation1991).

As Maria Teresa Huar puts it; ‘educators must proceed from a shared understanding of how our spaces for performance training have been shaped by non-consensual relations’ (Huar in Ginther Citation2023, 102). Actor trainers can reflect upon the expectations they bring into their training and rehearsal rooms:

The expectations of compliance considered to be ‘professional’.

To what extent discomfort is mandated or celebrated in the work.

How the texts used in training may circulate around themes that may retraumatise students from specific backgrounds.

If the techniques of acting may demand a ‘blurring’ of boundaries in the actor.

In 1999, Burgoign, Poulin and Rearden studied the way that the job of acting creates an artificial blurring of boundaries between the actor and the character they are playing. They interviewed actors about this phenomenon, and suggested that there needed to be what they call ‘optimal’ blurring for ‘authentic’ work to be made:

there may be an optimal degree of blurring that facilitates both artistic effectiveness and personal growth, while minimizing emotional distress. Two important conditions for the actor’s achieving such optimal blurring may be, (1) awareness that the life/theatre feedback loop may operate in acting experiences, and (2) development of strategies for boundary control that give the actor the ability to choose how and when to blur and reclarify boundaries (1999 165).

In 2013 I articulated that ‘the process of building trust is one that develops through every interaction with a student. It is never a finalised endpoint but is a journey of negotiations, honesty and tact’ (Hartley Citation2013, 178). I develop this point further by suggesting that:

trust is temporary and spatially dependent. It is defined as a process to be uncovered and worked with. The pedagogic relationship is one of tactful negotiation upon the nature of trust… Trust is an act that unites participants temporarily in agreement (Hartley Citation2013, 179.)

Bessel van der Kalk writes that ‘at the core of [trauma] recovery is self-awareness. The most important phrase in trauma therapy is ‘notice that’ …becoming aware of how your body organises particular emotions or memories opens up the possibility of change’ (Citation2014, 216). Simple side-coaching moments in my classroom come from ‘What are we/you noticing?’ ‘How are your bodies responding?’ I give students time to speak, write, draw or chat to a peer, at the end of classes. It is time to process and recognise the impact of the practice, and their learning. I become curious and create a culture of gnostic curiosity concerning how the pedagogy, the materials chosen, the techniques of training and the school we are in, impact upon theirs and consequently their students’ capacity to learn and upon acting epistemology.

Peer support

The rhetoric of some teachers in Actor Training, like much of HE has been that students in 2023 are ‘difficult’ to teach; in fact the teacher who rang me in the anecdote above began the conversation with that exact premise. Actor trainer Mark Seton hypothesises that ‘much of the literature in contemporary pedagogy regards student resistance to learning as a response due to a ‘deficiency’ within the student’ (2020, 134). Furthermore, he suggests that ‘many acting teachers believe that unquestioning submission will provide their student with three important and interrelated desires: acting ability, industry recognition and both social, and hopefully, financial reward’ (136). Whilst it is true, that resilience and comprehensive technique are vital to actors, Seton declares a tension between educational discomfort, and individual cultural, historical social and gender experiences. Moreover, if we consider the vital insights of Sara Ahmed, we can understand that being ‘difficult’ can be a symptom or behaviour that manifests out of the desire to fight a system that has, and still disadvantages particular students (Ahmed Citation2014). It is part of my practice to give peer support to teachers struggling with behaviours of resistance, and to centralise the experiences of their students in every situation. I do this to emphasise the importance of discourses of complaint as insurgent acts to end oppression, and moreover a necessary part of facilitating students’ agency.

I make sure that I am available for each student as they arrive to class, curating the learning space, moving chairs, looking up and greeting everyone by name. For the scared student of the introduction, I attend to their posture on arrival and meet them with a gentle welcome without asserting myself into their kinaesphere until I am clear of their adrenal regulation. My activity will move me through the space, and I take the appropriate time, before saying ‘good morning’ with a smile of welcome, I make sure that they are not the first person I speak to, nor are they the last. I pause to see if they impulse to respond, or if they cannot listen right now and then move to the next student. Later in the session, I will draw my attention to their breath to see what level of regulation they are at, and affirm their contribution when they are breathing in a grounded manner; a welcome comment, diligent notetaking, brave volunteering, or by saying ‘take the time you need to process, and silence is often helpful’ to the group. I try to validate each student in some way before the end of the session or day.

In so doing, I am reminding students that they are welcome in the space whatever their contribution to the work is, and regardless of their capacity. I may catch a moment of privacy to tactfully ask ‘you ok?’ or ‘late shift?’ and wait for the attention to ‘land’ in whichever way it does. Many times, this has resulted in an effusive apology, and my subtle reflection that ‘you don’t need to apologise for fighting to be here on time and fighting to pay the bills’ can result in a relaxation and a wry smile; sometimes it prompts an earlier arrival the following day or a different level of contribution in the afternoon class.

However, a tension arrives when behaviour impacts on the group’s learning. Students may feel uncomfortable when a student speaks too loudly; and they may be upset when a student refuses to engage with Ibsen. Mays Imad suggests that ‘cultivating a sense of purpose’ can potently support students to attend to the goals they have in the short and medium term and may invite both those terrified to participate, and those who are late for different reasons, to take responsibility and generate self-awareness in relation to their own power (2022, 43). It is the combination of shared understanding of fear, and a shared purpose towards compassion that sets the tone/environment of reparative (rather than defensive) recognition of difference (Sedgwick Citation2003). Peer support can also be seen as a fluid and reflexive dynamic that everyone within a group is responsible for; which resists homogenisation and welcomes the wilful; a trauma informed pedagogy provides support for each student as well as the teacher to recognise the symptoms of trauma, alongside a resistance to normativity.

Landon-Smith (Citation2023) advocates for ‘[p]lacing the actor at the centre, by positioning the actor as the expert in her own cultural context and allowing her to apply that expertise’ and has, through direct engagement witnessed:

that once their individuality and identity was positioned as a legitimate tool in the creative process, they were able to discover a pleasure to play and a consequent ease and openness in their performances. This potential power and impact must be explored by actors in their training, in order that they move into the professional industry carrying this power and able to show their best profile in audition, rehearsal and performance (2020, 349.)

I employ a Health Care Professions Council and British Association of Dramatherapists, registered drama therapist who runs sessions alongside the academic work of the programme. I first brought Christina Anderson into the programme in 2020 when the students experienced the life-changing impacts of COVID and were removed from their expected learning journeys into isolation and fear of the disease. Furthermore, the challenges faced by students of colour after BLM and all students after MeToo, manifested some enhanced emotional discomfort for students about power, responsibility, and care. Anderson works with the students in a group and one-to-one to reflect upon the challenges of being a trainer, and the narratives that are held within their different positions, biases and cultures. Her non-confrontational sessions amplify and provide space for students’ unique development as trainers. Christina’s sessions sit outside the curriculum, assessment and teaching frameworks of the programme in order to allow students to present as messy, upset or angry without worrying about their grades and to give students time and a space to process the challenges that acting, teaching and studying bring. Students are welcome to attend or not, and report that access to this support ensures a rapid and care-driven response to their wellbeing needs, which the institution cannot consistently provide for all studentsFootnote8. These interconnected layers of pedagogical individuation, peer support and therapeutic guidance allow the students to work more comfortably within the discomfort of a pluralist ensemble. By making the frameworks visible, I invite the students to celebrate, validate and permit each other to be unique, and also to resist when needed: they become curious of one another’s boundaries rather than judgmental of them. Whilst a full impact study of the way this impacts upon trainee teachers is necessary to make a broader claim, students regularly state how transformative this approach has been upon their confidence to teach, and upon their self awareness. This year’s exigent cohort emphasised how the permission to create boundaries and individuate their approaches, allowed them to really bond as an ensemble.

Collaboration and mutuality

Whilst I have excellent support from the school, and from a carefully chosen team, there is an emotional labour to this type of pedagogy. This labour is increased if the teacher has protected characteristics, and/or has experienced their own trauma:

Staff with protected characteristics are often at increased risk of exposure to trauma. Be that in their childhoods, personal lives, or professional lives. This is because they are often exposed to prejudice, discrimination, and endemic injustices. Certainly, in a way which more privileged groups in society are not (JD Citation2022).

Conclusions

Practitioners need to be aware of the impact of some training exercises and regimes to retraumatise students who come with existing trauma and create secondary trauma in others. Carello and Butler suggest that ‘[a]s educators we undoubtedly need to teach about trauma; at the same time, we must also be mindful of how we teach it as well as how we teach trauma survivors’ (Citation2014, 163). They recommend that encountering work about trauma, as well as working from personal stories that might recognise narratives of trauma will involve a recapitulation to positions of disempowerment for some students, and risk reinforcing hierarchies of privilege in those who resist discomfort. We must therefore be asking questions about the students we bring to the room, the texts that we are exposing the students to (why these students, why this text at this time) and the ways that learning as well as developmental stages may differ according to the positionalities of the students in the room. The Wheel of Trauma Informed Principles (2022) can be used to articulate, contain and shape the questions we ask of actors and actor trainers alike; foregrounding students’ agency as the fulcrum to destabilise hegemonic systems.

A trauma informed training practice allows teachers to work alongside students and colleagues to recognise the impacts that discomfort and trauma have on the learning journeys of our students. In the current climate the effects of trauma, and the socio-political battlegrounds of equality mean that we must reframe our pedagogy towards the knowledge and therefore agency of the students. Taking a non-judgemental audit of our expectations of the professional skills needed to be an actor, and reflecting upon our own positionality and regulatory responses, enables teachers to create a transparent and responsive pedagogy. This pedagogy can support students’ regulation of themselves and their use of appropriate language to articulate their experiences. I further suggest that equipped with the knowledge of the nervous system, and an understanding of their own boundaries, actors are able to demand changes in an often-negligent industry. Building a supportive team of educators with different positionalities and expertise, helps me to dialogue with the ways I am changing practice to meet the needs of contemporary actors. I am not alone in my desire to destabilise hegemonic systems that remove actors’ agency, students are demanding it, the industry is expecting it, and my colleagues are championing it. Together, we can reimagine a rehearsal room in which wellbeing, trauma knowledge and agency emerge as conscious affects of our practice alongside the skills needed to be a performer.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jessica Hartley

Dr Jessica Hartley is Course Leader for the MA/MFA in Actor Training and Coaching at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama in London. After a successful career as a secondary school drama teacher, she ran away with the circus, specialising in static trapeze. Her PhD research questioned the ethics and tact-filled practices that are used when working with adolescent students in circus. She foregrounds her neurodivergence, feminism and class as a political intervention when considering radical equality within academia and conservatoire training, and is focussing upon wellbeing and trauma informed practice in her recent work.

Notes

1 The anecdotes shared here are an amalgamation of a number of student-teacher interactions I have had over the past 5 years. They do not pertain to any one individual, although characteristics may be shared.

2 The MA/MFA Actor Training and Coaching at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama is one of only two programmes in the world which focusses on the way we teach and train actors. https://www.cssd.ac.uk/courses/actor-training-and-coaching-mamfa?gad=1& gclid=CjwKCAjwwb6lB hBJEiwAbuVUSrMSEad FYlMWIsOZFntS0JMAl KFcSe-V8DGjLOMoffW qPBuJkZvZthoCH2oQ AvD_BwE

3 This is data collected from students within higher education institutions in the US HE context by Thompson and Carello (Citation2022).

4 There is debate around the term friend, you may see it written as ‘Fawn’.

5 Within the UK equality Act 2010, there are nine characteristics protected under the law. These are: age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. In my practice, I also advocate for care experienced individuals to be similarly protected.

6 ‘There is a somatic norm whose contours are undeclared and firmly entrenched in space and time, even while the tenuous nature of those boundaries is constantly under risk of eruption’ (Puwar Citation2004, 13).

7 There is an emotional labour when a student brings their identity directly to their acting, particularly if their body is ‘disruptive’ to a hegemonic system because a student may feel they have to explain or identify themselves in the work (Puwar Citation2004). Expecting a disabled student to constantly speak about disability, or when the parts they are offered are always about disability is one example. Another may be when a student is expected to adopt an accent that is associated with their colour/culture or race; or peers looking at a specific student for approval when race is mentioned. These elements subtly and overtly ‘other’ students.

8 The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama has excellent support services for staff and students. However, these services are stretched and need-driven. Students can have up to six sessions of counselling if there is a specific mitigation to their learning journey, waiting lists are long, and the turnaround can be months. Our drama therapist Christina can refer students to the service, or to the NHS for further support if she feels it is necessary.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014. Willful Subjects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Barton, Robert. 1994. “Therapy and Actor Training.” Theatre Topics 4 (2): 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2010.0081.

- Brunzel, Tom, Helen Stokes, and Lea Waters. 2019. “Shifting Teacher Practice in Trauma-Affected Classrooms: Practice Pedagogy Strategies Within a Trauma-Informed Positive Education Model.” School Mental Health 11 (3): 600–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-09308-8.

- Carello, Janice, and Lisa D. Butler. 2014. “Potentially Perilous Pedagogies: Teaching Trauma Is Not the Same as Trauma-Informed Teaching.” Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 15 (2): 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.867571.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. Volhttps://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

- Ginther, Amy (Ed.). 2023. Stages of Reckoning: Antiracist and Decolonial Actor Training London: Routledge.

- Hartley, Jessica. 2013. “Guided Practices in Facing Danger: Experiences of Teaching Risk.” PhD Thesis., University of London.

- Harrison, Neil, Jacqueline Burke, and Ivan Clarke. 2023. “Risky Teaching: Developing a Trauma-Informed Pedagogy for Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (1): 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1786046.

- Imad, Mays. 2021. “Transcending Adversity: Trauma-Informed Educational Development.” Educational Development in the Time of Crises 39(3): 1–23.

- JD. 2022. Trauma Informed Systems and Organisations – ED&I Evolution not Revolution. The Equality Blog. https://theequalityblog.co.uk/2022/02/15/trauma-informed-systems-and-organisations-edi-evolution-not-revolution/#:∼:text=Staff%20with%20protected%20characteristics%20are,%2C%20discrimination%2C%20and%20endemic%20injustices.

- Landon-Smith, Kristine. 2023. in Ginther, Amy, Stages of Reckoning: Antiracist and Decolonial Actor Training. London Routledge.

- Merlin, Bella. 2022. Unpublished Testimonial upon the MA/MFA Actor Training and Coaching at RCSSD.

- Mitchell, Roanna. 2022. “Not Doing Therapy: Performer Training and the ‘Third’ Space.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 13 (2): 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2022.2052173.

- McNamara, Anna. 2022. Be the Change: Learning and Teaching for the Creative Industries. Guildford: Nova Science Publishers Inc.

- Okun, Tema. 2021. Characteristics of White Supremacy Culture. dRworks. www.dismantlingracism.org.

- Pao, Angela. 2010. No Safe Spaces: Re-Casting Race, Ethnicity and Nationality in American Theatre. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Peck, Lisa. 2021. Act as a Feminist: Towards a Critical Acting Pedagogy. London: Routledge.

- PTSD UK. 2023. Trauma: It’s More Than Just Fight or Flight. Accessed July 07, 2023. https://www.ptsduk.org/its-so-much-more-than-just-fight-or-flight/.

- Puwar, Nirmal. 2004. Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place. Oxford: Berg.

- Reddig, Nicole, and Janet VanLone. 2022. “Pre-Service Teacher Preparation in Trauma-Informed Pedagogy: A Review of State Competencies’.” Leadership and Policy in Schools 23 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2022.2066547.

- Sedgwick, Eve K. 2003. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Seton, Mark Cariston. 2010. “The Ethics of Embodiment: Actor Training and Habitual Vulnerability.” Performing Ethos: International Journal of Ethics in Theatre & Performance 1 (1): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1386/peet.1.1.5_1.

- Seton, Mark. 2020. Immunity to Change. Fusion Journal | Issue 17. www.fusion-journal.com.

- Spatz, Ben. 2015. What a Body Can Do. London: Routledge.

- Syler, Claire, and Daniel Banks. 2019. Casting A Movement: The Welcome Table Initiative: London: Routledge.

- Takacs, David. 2003. “How Does Your Positionality Bias Your Epistemology?” Thought & Action Summer: 27.

- Thompson, Phyllis, and Janice Carello. 2022. Trauma-Informed Pedagogies: A Guide for Responding to Crisis and Inequality in Higher Education. Switzerland: Palgrave McMillan.

- van der Kolk, Bessel. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

- Zazzali, Peter. 2022. Actor Training in Anglophone Countries. London: Routledge.