Abstract

‘In foreign affairs, Japan is often thought of as a big country acting like a small one. Yet that is to miss the significance, range and effectiveness of Japan’s economic statecraft, in which the country not only acts its true size but also does so with much more autonomy and agency than it does in classic diplomacy. Yuka Koshino and Robert Ward shine a truly illuminating light on how Japan thinks and behaves as a geo-economic actor, whether through trade, investment, aid, rule-setting or, crucially, technology. This Adelphi book deserves to be widely read, for it adds greatly to our understanding of a much neglected and under-appreciated aspect of Japanese strategy.’

Bill Emmott, Chairman of the IISS Trustees; Chairman of the Japan Society of the UK; and author of Japan’s Far More Female Future (Oxford University Press, 2020)

‘Groundbreaking work and a penetrating analysis of the geo-economic challenges facing Japan, a frontline country in the age of US–China rivalry and economic statecraft.’

Dr Funabashi Yoichi, Chairman of Asia Pacific Initiative

Geo-economic strategy – deploying economic instruments to secure foreign-policy aims and to project power – has long been a key element of statecraft. In recent years it has acquired even greater salience, given China’s growing antagonism with the United States and the willingness of both Beijing and Washington to wield economic power in their confrontation. This trend has particular significance for Japan, due to its often tense political relationship with China, which remains its largest trading partner. While Japan’s post-war geo-economic performance often failed to match its status as one of the world’s largest economies, more recently Tokyo has demonstrated increased geo-economic agency and effectiveness.

In this Adelphi book, Yuka Koshino and Robert Ward draw on multiple disciplines – including economics, political economy, foreign policy and security policy – and interviews with key policymakers to examine Japan’s geo-economic power in the context of great-power competition between the US and China. They examine Japan’s previous underperformance, how Tokyo’s understanding of geo-economics has evolved and, given constraints on its national power projection, what actions Japan might feasibly take to become a more effective geo-economic actor. Their conclusions will be of direct interest not only for all those concerned with Japanese grand strategy and the Asia-Pacific, but also for those middle powers seeking to navigate great-power competition in the coming decades.

Geo-economic strategy is not new: deploying economic instruments to secure foreign-policy aims and to project power has long been a core part of many countries’ statecraft even before the advent of the term itself.Footnote1 Analysts, meanwhile, have often sought to explain the link between economics and power. Writing in 1938, philosopher Bertrand Russell called economics an element in the ‘science of power’.Footnote2 In his seminal 1945 study of Germany’s use of trade policy in the run-up to the Second World War, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade, Albert O. Hirschman wrote of how ‘foreign economic relations can be used … as an instrument of national power policy’.Footnote3 Writing in the 1970s, political scientist Joseph S. Nye spoke of ‘the two-edged sword’ nature of economic interdependence in international relations, citing the ‘economic aspect’ of national security.Footnote4 In his 1987 study, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, historian Paul Kennedy, analysing imperial overstretch and the economic limits to national power, wrote: ‘all of the major shifts in the world’s military-power balances have followed alterations in the productive balances … where victory has always gone to the side with the greatest material resources.’Footnote5 The practice of geo-economics has an inseparable relationship with what might be termed ‘economic security’ – the safeguarding of national economic prosperity. Without a thriving national economy that is resilient to potential hostile measures by international adversaries, no state can use economic power effectively in order to achieve its geopolitical goals.

In 1990, as the Cold War ended, the historian Edward N. Luttwak provided the urtext of modern geo-economics, coining the term in his piece in the magazine The National Interest, ‘From Geopolitics to Geo-Economics: Logic of Conflict, Grammar of Commerce’, in which he assumed a ‘steadily reducing importance of military power in world affairs’ as ‘states … reorient themselves toward geo-economics in order to compensate for their decaying geopolitical roles’.Footnote6 The end of the Cold War in 1990, which coincided with the peak of Japan’s extraordinary post-Second World War economic rise, appeared indeed to have ‘ushered in a new era of geo-economics’.Footnote7

Concern about the link between economics and national power waned, however, during the 1990s.Footnote8 In part this reflected the United States’ emergence as the apparently unchallenged superpower and the benign growth environment for much of the rich world, which together bred complacency regarding the relationship between economics and security. The economic interdependence that followed the take-off of globalisation in the 1990s was seen in the West as an agent for promoting not just economic growth, but also liberal economic and political values. This was reinforced by the global economic boom that followed China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and which lasted until the global financial crisis of 2008. In June 2001, on the eve of China’s joining the WTO, The Economist newspaper forecasted that membership would ‘bind China to international rules that will further diminish the role of government in the economy’, citing those ‘more optimistic Chinese intellectuals [that] believe that economic globalisation will, over time, transform China politically as well’.Footnote9

Interest in geo-economics, however, has returned with a vengeance since the global financial crisis of 2007–08. China’s rise has been less benign than disruptive for the West. Beijing has developed its ‘own theory of “exceptionalism” to define its external engagement’, thereby upsetting the global balance of power.Footnote10 Moreover, China is a geo-economic power. As the world’s second-largest economy and with a 1.4 billion-strong continental-sized domestic market, Beijing boasts significant geo-economic endowments, which it deploys to project Chinese power onto its neighbourhood and beyond. It does this through a mixture of economic inducements and coercion. A good example of the former is its multi-billion-US-dollar global development programme, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), while the latter is exemplified in the country denying access to its vast domestic markets to interlocutors that fail to toe Beijing’s line on certain policy issues. Australia, Japan, Lithuania, the Philippines, South Korea and Taiwan have all been on the receiving end of Chinese economic coercion since 2010.

The economic interdependence fostered by globalisation and the resulting central position of China in the world’s supply chains have strengthened Beijing’s geo-economic hand. A study from McKinsey Global Institute in 2019 found that China was embedded in the global value chains of the highly traded electronics, machinery and equipment sectors, accounting for 17–28% of global exports of these goods, 9–16% of global imports and 38–42% of total output.Footnote11 ‘Manipulating the asymmetries of interdependence’ is thus a key means by which Beijing wields power internationally.Footnote12 This has opened new avenues for Chinese statecraft to challenge economic ‘rules, norms, standards and protocols’, which as one observer notes ‘is where the Great Game of geo-economics is at play’.Footnote13

Geo-economic strategy may be an eternal feature of international affairs, but its character thus evolves alongside the changing nature of the international economic system and the relative economic interdependence of its major powers. Those concerned with geo-economics, and economic security, are no longer primarily preoccupied with natural resources and territory, but also with international supply chains, leading-edge technologies and their associated standards, as well as with the interaction between the civilian and military sectors frequently driving innovation.

China’s rise and its propelling of geo-economics to the centre stage of contemporary international relations raises issues for all countries subscribing to the liberal international order, but perhaps particularly so for Japan. From the 1980s, Japanese official development assistance (ODA) and direct investment by Japanese companies helped to lay the foundations for China’s economic modernisation, with Japan overwhelmingly having had the upper hand over China in terms of economic size and sophistication. But China’s rise has transformed the dynamics of the bilateral relationship. By many measures, China is now Japan’s most important economic partner. In 2002, China overtook the US as Japan’s biggest source of imports and, by 2009, as its largest export market. China’s demand for Japanese goods to fuel its rapid growth after WTO accession undoubtedly accelerated Japan’s economic recovery after the bursting of its asset-price bubble in the early 1990s. Japanese firms have also been major investors in China, particularly since the 2007–08 financial crisis. Before the coronavirus pandemic started in 2020, China was also Japan’s largest source of inbound tourists, accounting for one-third of the total during 2019. This drove the growth of Japan’s domestic tourism sector, one of the success stories of then-prime minister Abe Shinzo’s economic reforms, providing significant economic stimulus to Japan’s cities and prefectures.Footnote14 Although China still needs access to both Japanese technology and management know-how to raise the value added by its industry, Japan’s economic relationship with China has become asymmetric. An important implication of this is that Tokyo cannot easily afford to antagonise Beijing and risk losing access to China’s vast market and resources.

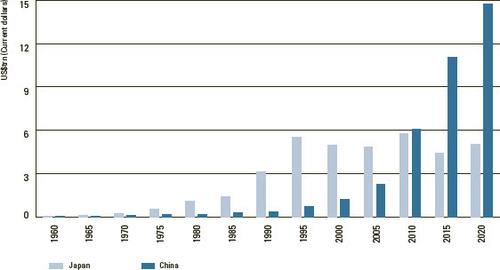

China also presents Japan with its most acute security challenges. Beijing has been outspending Tokyo on defence and out-investing Japan in emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum computing, that have military as well as civil applications. In 2000, the defence budgets of China and Japan were of broadly similar size; by 2020, China’s defence budget was four times larger than that of Japan. Beijing’s spending on research and development (R&D) rose by a factor of ten from 2000 to 2017, while Japan’s failed to even double.Footnote15 The Japanese government now also frequently accuses China of ‘revisionism’, which it says is displayed in Beijing’s ‘unilateral attempts to change the status quo’ in the region.Footnote16 China’s extensive territorial claims in the South China Sea on the basis of its ‘nine-dash line’ demarcation and its construction of artificial islands there, both of which infringe international law, are examples of this.Footnote17 There are grounds for believing that Beijing has defined the South China Sea as a national ‘core interest’, meaning that it will not negotiate its claims and may use force to defend them.Footnote18 The South China Sea – as well as the closer East China Sea – are of particular concern to Tokyo given Japan’s economic reliance on long sea lines of communication (SLOCs) that traverse both seas, sustaining its large resource needs and carrying its exports. Tokyo’s and Beijing’s SLOCs overlap in the South China Sea, and indeed elsewhere, making Beijing’s territorial claims in the South China Sea a direct economic and security concern for Japan.Footnote19 Beijing’s increasing shrillness regarding its intention to absorb Taiwan serves only to further fuel Tokyo’s strategic anxiety.

Japan’s ‘strange existence’

The rising importance of geo-economics in international relations should play to Japan’s strengths. Economically, it has long been a giant. Accelerated by factors including the Korean War (which catalysed Japanese export growth), the ‘“Great Leap Forward” of the capitalist world economy’ during the 1950s and 1960s, and by favourable national demography resulting from a post-Second World War baby boom, by the 1960s Japan already had the status of a ‘great power’ in economic terms.Footnote20 By the early 1970s Japan had overtaken France, West Germany and the United Kingdom to become the world’s second-largest economy.Footnote21 Given the economic trauma and stagnation of the 1990s after the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble – the largest asset-price collapse of the twentieth century – and the strengthening headwind of an ageing and then-shrinking domestic population, it was not surprising that in 2010 Japan’s economy was overtaken by the rapidly growing Chinese economy for the global number-two position.Footnote22 Although faster-growing and more populous emerging markets in the region such as India and Indonesia are now closing the gap in size with Japan’s mature economy, it will remain in the top economic tier for several decades in terms of both its absolute size and the wealth of its market. Its economy will also remain larger than that of any other Western country, apart from the United States, into the second half of this century.Footnote23

Japan’s size has made it an important global economic actor. A founding member of the Group of Seven (G7) group of industrialised economies in 1975, it has also long been the world’s largest creditor and, after the US, a leading contributor to the Bretton Woods institutions.Footnote24 Despite China’s GDP having overtaken Japan’s in 2010, the latter remains the second-largest financial contributor to the IMF and the World Bank Group, the third-largest to the UN, and, along with the US, the largest to the Asian Development Bank (ADB).Footnote25 It is also one of the largest providers in cash terms of ODA, which is dispersed via the state development agency, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and the state policy bank, the Japan Bank of International Cooperation (JBIC).Footnote26 Japan is the largest sponsor of infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia despite China’s efforts to expand its presence in the region through the BRI.Footnote27 As of mid-2021, Japan’s stock of investment in uncompleted projects in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam stood at US$259bn, compared with China’s at US$157bn.Footnote28 Japanese banks lend more to Southeast Asia’s five largest economies (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam) than those of France, the UK and the US combined. Japan also remains one of the world’s largest portfolio investors.Footnote29

Despite its economic size and influence, Japan’s ability to exercise military statecraft – and therefore hard power – is constrained. This deprives it of the full spectrum of tools with which to project national power, giving rise to what Kosaka Masataka, one of Japan’s leading post-Second World War international-relations thinkers, called Japan’s ‘strange existence’ on the world stage.Footnote30 This is partly the result of deliberate policy. Japan’s constitution, promulgated in 1947 and now the world’s oldest unamended such document, was drawn up against the backdrop of Japan’s catastrophic defeat in the Second World War and the victorious Allies’ desire to block any re-emergence of Japanese militarism. The preamble to the constitution pledges that ‘never again shall [Japan] be visited with the horrors of war through the action of government’, and Article 9 of the document states that ‘the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes’.Footnote31 One lingering result of this has been the long-term conceptualisation of Japanese security thinking around an ‘exclusively defence-oriented policy’ (senshū bōei), meaning that ‘defensive force is used only in the event of an attack’.Footnote32 This has left a number of defence anomalies for Japan. Although by political convention Japan only spends around 1% of its GDP on defence, its large economy means that the absolute size of its defence budget is still considerable and was the world’s eighth largest in 2020.Footnote33 The constitution’s provision that ‘land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained’ means that for some observers the Self-Defense Forces (SDF, Japan’s de facto armed forces) occupy a constitutional grey zone, or are ‘simply unconstitutional’.Footnote34 Japan therefore lacks a clearly delineated and agreed constitutional basis for ensuring its national security against external threats.

Given its parallel history of twentieth-century militarism, Germany is the main comparator for Japan’s security predicament. The German constitution, however, puts no limits similar to Japan’s on maintaining war potential, although Article 87a stipulates that the Federal Republic’s armed forces are ‘for [the] purposes of defence’.Footnote35 In 2005, Germany also introduced a law to both allow and regulate the deployment of armed forces abroad.Footnote36 Germany’s membership of NATO is a further differentiator from Japan. As noted in a IISS Adelphi book on German security policy published in 2021, during the Cold War the German armed forces were ‘optimised for collective defence within NATO, which, due to Germany’s geographical position, was equivalent to territorial defence’.Footnote37 At the end of the Cold War in 1990, Germany had more combat battalions in active service than either the UK or France. In contrast, Japan counts the US as its only formal security ally under the terms of the 1951 Japan–US Security Treaty.Footnote38 There is, of course, no NATO equivalent in Asia, reflecting the United States’ post-Second World War preference for a ‘hub-and-spokes’ system of bilateral alliances in the region that gave the US ‘more leverage, while depriving allies of other rule makers or mediators’.Footnote39 The closest equivalent in the region, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), was disbanded in 1977 just over 22 years after its founding, having displayed neither ‘a viable political purpose, [n]or a military function’.Footnote40

Yoshida Shigeru, the pivotal prime minister of Japan’s early post-Second World War years who was in office in 1946–47 and 1948–54, built on the ‘peace constitution’ with what later became known as the Yoshida Doctrine.Footnote41 This doctrine had three pillars: Japan was to rely militarily on the US, while maintaining a ‘low posture’ in global affairs and an ‘economics above all’ domestic policy stance that focused on domestic growth and foreign trade, and while spending minimally on armaments. Yoshida did not rule out the possibility of Japan eventually rearming and regaining its status as an independent military power.Footnote42 But the immediate priority was the need for economic growth to heal the pressing post-Second World War divisions in Japan.Footnote43 This ‘low posture’ stance, or ‘passive internationalism’, guided Japanese policy for much of the Cold War.Footnote44 For most of this period, Japanese economic statecraft was often deployed with one eye on buttressing Japan’s security alliance with the US amid frequent bouts of bilateral trade friction. There were also US voices who accused Japan of being a reactive and mercantile free-rider of the international order.

During the Cold War, the main challenge to the Yoshida Doctrine came from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) prime minister Nakasone Yasuhiro, who held office from 1982–87. Nakasone wanted to turn Japan into an ‘international state’ (kokusai kokka Nihon e zenshin) and a world technology leader, which would help propel Japan’s broader global ambitions.Footnote45 He also sought to bind Japan more closely into the security alliance with the US in order to counter the Soviet threat by agitating for Japan’s ‘autonomous defence’ (jishu bōei ron). An early example of this was his cabinet’s approval in January 1983 – just before Nakasone’s visit to Washington that month – of the transfer of purely military technology to the US, and only to the US.Footnote46 This was a significant tweak to the ban on exports of arms and military technology introduced in 1967 under prime minister Sato Eisaku (in office from 1964–72) and tightened in 1976 under prime minister Miki Takeo (in office 1974–76), and was intended to boost US–Japan security-alliance inter-operability. In 1986, Tokyo approved Japan’s participation in US president Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative – dubbed ‘Star Wars’ by the press – which was aimed at developing a spacebased missile-defence capability.Footnote47 In 1987, Nakasone also secured cabinet approval to raise defence spending – albeit by a tiny amount – above the self-imposed cap of 1% of GNP. Nakasone was also voluble in his support for constitutional revision, which included amending Article 9 and clarifying the constitutional status of the SDF, although pragmatically he recognised the political difficulties of achieving this.Footnote48 For all Nakasone’s activism, however, it is difficult to discern a specifically geo-economic element to his policy. Indeed, much of his administration’s energy with regards to economic policy was consumed with placating increasing tensions with the US over the size of Japan’s trade surplus.Footnote49

Since the end of the Cold War, three LDP-led administrations have sought to challenge Japan’s post-Second World War security trajectory. Externally, in addition to a desire never to repeat the diplomatic trauma of the first Gulf War (in which constitutional and political wrangling saw Japan’s response limited to a financial contribution to the coalition), the first North Korean nuclear crisis of 1992–94 and the third Taiwan Strait crisis of 1995–96 were also a major trigger for fresh security-policy initiatives after the LDP’s return to power in 1996, particularly for upgrading Japan’s security relationship with the US.Footnote50 Domestically, power shifts within the LDP provided further momentum for change. The discrediting and weakening of the LDP’s long-dominant dovish wing, which had presided over the party’s 1993 fall from power as well as the bursting of the asset-price bubble, and the parallel rise of its hawkish, revisionist wing, which sought to free Japan from its post-Second World War constitutional constraints, provided an important political tailwind for this.Footnote51

The first of these administrations was that of Hashimoto Ryutaro in 1996–98. The major foreign-policy achievement of the Hashimoto premiership was to preside over the first revision to the Guidelines for Japan–US Defense Cooperation since they were first issued in 1978.Footnote52 The new guidelines envisaged greater burden-sharing by Tokyo through allowing it to respond militarily to contingencies arising from ‘situations around Japan’. This was an important evolution from the 1978 guidelines, which had focused largely on the defence of Japan itself. But Hashimoto’s window of opportunity was short. Economic instability following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, which damaged Japan’s interests in the region, and increasing problems in Japan’s own financial sector following the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the early 1990s contributed to the brevity of his premiership. Hashimoto resigned in July 1998, taking responsibility for a disastrous showing by the LDP in the mid-year Diet (parliament) upper-house election.

Another external shock, the 11 September 2001 terror attacks on the US, triggered a further step change in Japan’s security policy under the 2001–06 administration led by Koizumi Junichiro. In 2004, Christopher Hughes accurately referred to the Koizumi administration’s response to the US-led ‘war on terror’ as ‘unprecedented’.Footnote53 A desire in Tokyo to avoid repeating the reputational trauma of the first Gulf War was a strong catalyst for the focus and speed of Koizumi’s response. In October 2001 the Diet passed the Anti-Terrorism Special Measures Law, and in November 2001 Japan sent the Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF, Japan’s de facto navy) to the Indian Ocean to provide logistical support for the US-led coalition’s operations in Afghanistan.Footnote54 In 2004, the Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF) and the Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF) were deployed in Iraq and Kuwait under the ‘Special Measures on Humanitarian and Reconstruction Assistance in Iraq’ Law passed by the Diet in December 2003.Footnote55 This was the first international deployment by the SDF that was not under a UN mandate. Other changes under the Koizumi administration included a decision in December 2003 to build a ballistic-missile-defence (BMD) system, which in effect committed Japan to technological and strategic alignment on missile defence with the US, and revisions in 2004 to Japan’s basic defence policy (the National Defense Program Guidelines) and the five-year implementation plan for this policy (the Mid-Term Defense Program).Footnote56

Thanks in part to Japanese support given to the US after the 2001 terror attacks, US–Japan economic relations were relatively smooth during the Koizumi years – certainly in comparison with the strains of the 1980s and early 1990s. By contrast, relations with China and South Korea cooled under the Koizumi administration. A particular cause of this was the prime minister’s visits to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, where the spirits of Japan’s military war dead are enshrined, including those of 14 officers convicted of being ‘Class-A’ war criminals after the Second World War.Footnote57 Cooler relations with Beijing and Seoul impeded Japan’s ability to project broader influence into much of the region.Footnote58

Abe’s structural break

Building on the Hashimoto and Koizumi reforms, the second administration of Abe Shinzo (2012–20) ushered in some of Japan’s most far-reaching security-policy changes since 1945. The pace of these reforms is striking even in an international context and reflected both the lessons learned by Abe from the policy failures of his 2006–07 administration as well as the ideological urgency of wanting to restore the Japanese autonomy (‘Nihon ga dokuritsu wo torimodosu’) that he believed was lost after the Second World War, thus reforming the ‘post-war regime’ (sengo rejīmu kara no dakkyaku)Footnote59 and allowing Japan to return to global ‘Tier 1’ status.Footnote60 Related to this was his identification of China, and its widening sphere of influence in the region and drive for great-power status, as the biggest strategic threat to Japan.Footnote61 In some respects, Abe was just the latest in a long line of Japanese leaders for whom China was a ‘political obsession’ in one way or another.Footnote62 Given its size, impact on the region and the two countries’ shared history and geographical proximity, China has unsurprisingly exerted a strong gravitational pull on Japanese politics and even national identity.Footnote63 But Abe’s desire to confront a rising China from a position of reinvigorated national strength as a way of preserving regional stability – which reflected his view that underestimating the strength and resolution of one power by another is a major cause of conflict – was new.Footnote64 The approach made strategic sense for Japan given both its geographical proximity to China and what Australian international-relations scholar Coral Bell, writing in the late 1960s, aptly and presciently termed China’s ‘tenacity’:

China has been a very tenacious power: tenacious of its people … ; tenacious, at least in intention, of territory acquired (an area won for civilization – that is for China – was not to be considered permanently lost, even if temporarily out of control); tenacious of old scores … Footnote65

Despite his political dominance in his second administration, and his implementation of a flurry of significant security reforms, Abe still failed to achieve his signature ambition of changing Article 9 of the constitution.Footnote66 This reflected both the very high procedural hurdles to revision and the lack of a clear public majority in favour of it.

Abe’s overall vision also contained economic underpinnings for reinforcing national strength. Domestically, this found expression in his ‘Abenomics’ internal balancing policy platform, announced in 2013. While enjoying some success, Abe’s domestic economic policies have had a mixed legacy. Abe had more success with his economic foreign policy and diplomacy. His bid to restore ‘Japanese autonomy’ saw a step change from previous administrations in the deployment of Japanese economic statecraft overseas. One change involved a concerted effort to build coalitions of like-minded partners with a view to supporting the rules-based international order. The importance of rules in Abe’s policy strategy was underscored in the title of his keynote address to the 13th IISS Shangri-La Dialogue in June 2014: ‘Japan for the rule of law. Asia for the rule of law. And the rule of law for all of us.’Footnote67 Leading examples of this coalitionbuilding included: the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, in collaboration with the ADB and announced shortly after Chinese President Xi Jinping’s 2013 BRI launch (2014); the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), which provided, among other things, an organising framework for Japan’s economic statecraft in the region (2016); Japan’s successful rescue of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) regional trade mega-deal after US withdrawal and its rebirth as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) (2017); and the securing of G20 support at the Osaka Summit for Japan’s quality infrastructure policy and the launch of the Osaka Track to promote the Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) concept to, respectively, counter China’s BRI and push for ‘internet sovereignty’ (2019). The addition of an economics unit to the new inter-agency National Security Secretariat (NSS) to coordinate economic security affairs in 2020 marked an important institutional strengthening of the Japanese government’s ability to coordinate responses to economic security challenges, which overlapped with geoeconomic concerns such as supply-chain security.

Externally, Abe was able to use Trump’s hard line against China as a cover for rallying support for Japan’s efforts to build China-balancing coalitions, combining openness to China in order to help preserve the liberal international order (through, for example, FOIP – which Tokyo views as being open to Beijing, at least in theory – and the CPTPP) with an implicit message of deterrence (through, for example, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, known as the Quad, with Australia, India and the US, and Japan’s own security reforms).Footnote68

The activism of Abe’s foreign policy was thus partly a response to China’s rise and its impact on the balance of power in Asia. In this he was an early mover by the standards of, for example, his G7 peers – his identification of the threat China posed to Japan was already apparent at the time of his first, short-lived 2006–07 administration, notwithstanding China’s then generally benign global posture and the still favourable world economic environment. For example, in his de facto 2006 manifesto, Utsukushii Kuni E (‘Towards a Beautiful Country’), he wrote at some length on China, citing the uneven domestic distribution of China’s rapid economic growth and Chinese antagonism towards Japan, while acknowledging the ‘inseverable’ interdependence of the Sino-Japanese economic relationship in a striking phrase: ‘Nihon to Chūgoku wa kitte mo kirenai “gokei no kankei” ni aru no ron wo matanai’ (There is no arguing that Japan–China relations are unseverable and reciprocal).Footnote69 All this did not, however, prevent him from remaining open to improving relations with Beijing – witness his first term wherein he tried to repair the damage done to bilateral relations during the Koizumi administration by visiting China on his first overseas trip in October 2005, or during his second term, when, for example, in November 2014 Japan and China were able to agree on four underpinning principles for future dialogue, or towards the end of his premiership when he sought to secure a state visit by President Xi to Japan in 2020, despite Tokyo’s concerns about China’s territorial probing around the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.Footnote70

Abe’s interrelated internal and external balancing and coordination of Japanese foreign policy across the economic and security spheres to position Japan as a protector of the rules-based order, thus supplementing US power in Asia to balance a rising, revisionist China, already marks him out as one of Japan’s most consequential post-Second World War prime ministers, despite the patchy record of ‘Abenomics’.Footnote71 Although his immediate successor, Suga Yoshihide, did not enjoy anything like the same degree of political dominance as Abe, there was little deviation under Suga from the broad course set by his predecessor, notwithstanding his politically pragmatic downgrading of the urgency of constitutional reform. Initial signals from the succeeding administration of Kishida Fumio, who became prime minister in October 2021, also suggested broad foreign-policy continuity. Although the pace of innovation may slow in the absence of a leader as electorally dominant and secure as Abe was during his second administration, geo-economics as a key ingredient in Japanese statecraft looks as if it is here to stay.

Considering Japan’s geo-economic effectiveness

This Adelphi book will, however, attempt to answer a larger and, for Japan’s partners, more consequential question than that of the durability of Japan’s geo-economic activity – that of how effective Tokyo can be as a geo-economic actor given the constraints on Japan’s full-spectrum power projection; or, phrased differently: although Abe recognised Japan’s responsibility to support the rules-based order, to what extent did he enhance Japan’s ability to act in support of this goal? To answer this question, it is important to consider the triggers for Japan’s refining of its geoeconomic strategy. We will look at the means by which Japan has sought to pursue geo-economic power and how its conceptualisation of economic statecraft has changed since 1945, and we will offer an assessment of how successful this pursuit has been.

This assessment will also examine a number of Japanesespecific obstacles, in terms of institutions, domestic ideological tensions, capabilities and resilience, to Tokyo’s employment of geo-economic power. Japan’s ability to facilitate military– civil interaction, given the tight ring-fencing of its defence sector from the civilian economy, will be an important focus of our consideration of Japan’s geo-economic power-projection capabilities. Civilian emerging technologies increasingly have military applications, while also being critical for economic growth. Coupled with the military–civil fusion strategy pursued under Xi Jinping in his drive to secure great-power status for China, this has forced the issue to the centre of Japanese geo-economic policymaking.Footnote72 Japan’s ongoing difficulty in employing all the militarily-related policies available to a ‘normal’ state, including greater military–civil interaction, hampers its pursuit of economic security which is, in turn, a key ingredient in geo-economic effectiveness.

Ultimately, the question is whether Japan can become a more effective geo-economic power despite the headwinds. We assume that the changes implemented under Abe’s second administration are robust enough to withstand a degree of domestic political fluctuation. Japan is unlikely to revert to being a ‘quietist’ state in which Tokyo pursues only minimum power-projection capabilities and remains static and reactive to a changing geopolitical and geo-economic environment.Footnote73 Indeed, to do so would suggest acquiescence by Tokyo in Chinese regional hegemony, which looks unlikely given the challenge this would pose politically and economically to the traditional supporters of Japanese prosperity and the rise (according to public-opinion surveys) in voters’ concerns about China’s behaviour in the region.Footnote74

We also view as unlikely a revolutionary scenario in which Japan increases its ability to project autonomous power by, for example, acquiring offensive capabilities. This scenario would have the greatest potential for accelerating developments in the technology sector, and hence Japanese geo-economic effectiveness. It would, however, require Japan to dismantle its ‘peace constitution’ and possess ‘normal’ military powerprojection capabilities as well as to revitalise its defence industry. This could not be done without significant domestic political backlash.

More likely is a scenario in which Japan projects geoeconomic power in coordination with the US and Tokyo’s close partners through the enhancement of economic interoperability and plays an active role in setting rules, standards and norms for regional and global trade agreements and new domains such as digital, cyber and space. Under this scenario Japan would, in effect, be duplicating its military-alliance management activities with the US in the economic realm. We argue that Japan can be both evolutionary and effective as a geo-economic actor, albeit less effective than it would be under the less plausible revolutionary outcome.

Finally, we intend this Adelphi book to contribute to the literature on Japan’s ‘grand strategy’ in several ways. Firstly, it draws on diverse disciplinary areas, including economics, political economy, foreign policy and security policy, thereby filling what is in our view a gap in the existing literature. Secondly, this book will be one of the first to examine Japan’s geo-economic power in the context of great-power competition between the US and China. Underpinning this is a recognition that Japan requires a different strategy from that of the Cold War, because China as a revisionist power is fully embedded in the global economy. Thirdly, Japan boasts a rich seam of analytical literature going back decades which considers global ‘power economics’ and Japan’s place in the world. This includes a number of distinguished Japanese scholars who have written over the years for the IISS Adelphi series. This, together with interviews with senior Japanese policymakers and experts, has informed our research. We hope that this book will also serve to highlight some of Japan’s own thinking on this important subject and inform policymakers elsewhere as they grapple with similar issues. In addition, we believe that Japan’s path towards geo-economic effectiveness, in an international environment increasingly dominated by the US and the emerging economic superpowers of China and India, can provide useful insights for other ‘middle powers’ in the coming decades.

Notes

1 This forms the core of our definition of geo-economics. In our definition, geoeconomics is different from mercantilism, in which economic advantage is the goal. See also Robert D. Blackwill and Jennifer M. Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft (Cambridge, MA and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016), pp. 30–2, for a detailed discussion of why geo-economics is not ‘some repurposed form of mercantilism’.

2 Cited in David A. Baldwin, Economic Statecraft (Princeton, NJ and Chichester: Princeton University Press, 1985), p. 51. In describing the evolution of the relationship between Japanese economic and foreign policy since the end of the Second World War, we will use the term geo-economics where applicable even where activity predates Edward N. Luttwak’s coining of the term (see below).

3 Albert O. Hirschman, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1945/1980), p. 58. Despite its age, Hirschman’s book repays study in light of his prescient comments on the difficulties of ‘having purely economic relations with the totalitarian states’ (p. 78).

4 Joseph S. Nye, ‘Collective Economic Security’, International Affairs, vol. 50, no. 4, October 1974, pp. 584–98, especially p. 588.

5 Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (New York: Random House, 1988), p. 439. Emphasis in original.

6 Edward N. Luttwak, ‘From Geopolitics to Geo-economics: Logic of Conflict, Grammar of Commerce’, National Interest, no. 20, Summer 1990, pp. 17–23.

7 Sanjaya Baru, ‘Geo-economics and Strategy’, Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, vol. 54, no. 3, June–July 2012, pp. 47–58.

8 The first oil shock of 1973, which was triggered by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ (OPEC) decision to impose an oil embargo on the US and other countries supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War, threw this link into sharp relief. It was thus a major geo-economic turning point and forced Western governments to rethink policies around economic security. Writing in 1978, Japanese commentator Dr Funabashi Yoichi describes this new era as one of ‘power economics’ in which ‘economic power is substituted for military power’ [gunji pawā no ‘daiyaku’ toshite keizai pawā ga kakkō no dōgu toshite mukaeirerareyō toshite iru to miru beki na no ka]. See Funabashi Yoichi in his 1978 book Keizai Anzenhoshō Ron – Chikyū Keizai Jidai no Pawā Ekonomikkusu [Economic Security – the Era of Power Economics in the Global Economy] (Tokyo: Toyo Keizai Shinposha, 1978), pp. 292–5.

9 ‘Intimations of Mortality’, The Economist, 30 June 2001, https://www.economist.com/special-report/2001/06/28/intimations-of-mortality.

10 ‘Prospectives’, Strategic Survey 2019: The Annual Assessment of Geopolitics (Abingdon: Routledge for the IISS, 2019), pp. 11–18, especially p. 12.

11 McKinsey Global Institute, ‘China and the World: Inside the Dynamics of a Changing Relationship’, 1 July 2019, p. 9, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/mgi-china-and-the-world-full-report-feb-2020-en.pdf.

12 Joseph S. Nye, Jr, The Future of Power (New York: Public Affairs, 2011), p. 55.

13 Interview with Dr Funabashi Yoichi, Chairman, Asia Pacific Initiative, July 2021.

14 JTB Tourism Research & Consulting Co., ‘Japan-bound Statistics’, https://www.tourism.jp/en/tourism-database/stats/inbound/.

15 ‘Bei Chū 2 Kyō, Shikinryoku Tosshutsu, Nihon wa Gijitsu Kyōsō Taiba no Kiki’ [US and China Leading in Spending Power, Danger of Japan Lagging Behind in Technological Competitiveness], Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 18 February 2020, https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXM-ZO55791350Y0A210C2MM8000/.

16 Japan, Ministry of Defense, ‘Defense of Japan (Digest)’, p. i, 2021, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/publ/w_paper/wp2021/DOJ2021_Digest_EN.pdf.

17 Oriana Skylar Mastro, ‘How China Is Bending the Rules in the South China Sea’, Interpreter, The Lowy Institute, 17 February 2021, https://www.low-yinstitute.org/the-interpreter/how-china-bending-rules-south-china-sea. See also Japan, Ministry of Defense, ‘Defense of Japan 2015’, p. 119, https://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11591426/www.mod.go.jp/e/publ/w_paper/pdf/2015/DOJ2015_1-2-3_web.pdf, for an example of the Japanese government’s articulation of its concerns about China’s land-reclamation work in the South China Sea.

18 Sarah Raine and Christian Le Mière, Regional Disorder: The South China Sea Disputes, Adelphi 436–7 (Abingdon: Routledge for the IISS, 2013), p. 58.

19 Ibid., p. 12.

20 Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991 (London: Michael Joseph, 1994), p. 268; and Michio Royama, The Asian Balance of Power: A Japanese View, Adelphi Papers, no. 42 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1967), p. 2.

21 Kosaka Masataka, A History of Postwar Japan (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1982), p. 223; and World Bank, ‘GDP (Current US$) – Japan’, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?contextual=similar&locations=JP.

22 Christopher Wood, The Bubble Economy: The Japanese Economic Collapse (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1993), p. 1. At the bubble’s peak the land occupied in Tokyo by the Imperial Palace was notionally worth more than the entire state of California – see Bill Emmott, The Sun Also Sets: The Limits to Japan’s Economic Power (New York, Toronto, Sydney, Tokyo and Singapore: Simon & Schuster, 1991), p. 118.

23 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), ‘Real GDP Long-term Forecast, Total, Million US dollars, 2060 or Latest Available’, Quarterly National Accounts, 2018, https://data.oecd.org/gdp/gdp-long-term-forecast.htm.

24 The G7 includes Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US. ‘Japan Still World’s Top Creditor at End of 2019’, Japan Times, 26 May 2020, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/05/26/business/japan-worlds-top-creditor/.

25 See IMF, https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/quotas/2020/1027.htm; World Bank Group, https://finances.worldbank.org/Shareholder-Equity/IDA-Voting-Power-of-Member-Countries/v84d-dq44/data; and United Nations Secretariat, https://undocs.org/en/ST/ADM/SER.B/1023; Asian Development Bank, https://www.adb.org/documents/adb-annual-report-2020.

26 OECD, ‘Aid by DAC Members Increases in 2019 with More Aid to the Poorest Countries’, 16 April 2020, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/ODA-2019-detailed-summary.pdf.

27 Brad Glosserman, ‘In the Competition for Southeast Asia Influence, Japan Is the Sleeper’, Japan Times, 22 January 2020, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2020/01/22/commentary/japan-commentary/competition-south-east-asia-influence-japan-sleeper/.

28 ‘A Glimpse into Japan’s Understated Financial Heft in South-East Asia’, The Economist, 14 August 2021, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/08/14/a-glimpse-into-japans-understated-financial-heft-in-south-east-asia.

29 Mike Bird, ‘Finance and Foreign Policy Mix When China and Japan Lock Horns’, Wall Street Journal, 22 October 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/finance-and-foreign-policy-mix-when-china-and-japan-lock-horns-11603356707?page=1.

30 Kosaka Masataka, Options for Japan’s Foreign Policy, Adelphi Papers, no. 97 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1973), p. 7. It is worth quoting the whole sentence as Kosaka, writing in the early 1970s, captures the oddness of Japan’s position in international relations well: ‘For one thing, it is difficult to understand a strange existence like Japan’s at all adequately. In psychological terms it is probably not too difficult to deal with a country which is powerful in a general sense, or even with one which is weak in a general sense, but Japan belongs to neither category.’

31 Japan, Cabinet Secretariat, ‘The Constitution of Japan’, 3 November 1946, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/constitu-tion_and_government_of_japan/constitution_e.html.

32 ‘Other Basic Policies’, Japanese Ministry of Defense, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/d_policy/basis/others/index.html.

33 IISS, The Military Balance 2021 (Abingdon: Routledge for the IISS), p. 23.

34 Tanaka Akihiko, Japan in Asia: Post-Cold-War Diplomacy (Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2017). Japan’s SDF grew out of the National Police Reserve Force, which was formed in 1950 after US troops were moved out of Japan to fight in the Korean War. As Muraoka Kunio writes: ‘Thus the initial step for the rearmament of Japan was made without the Japanese people realizing it.’ The SDF was formed in 1954. See Muraoka Kunio, Japanese Security and the United States, Adelphi Papers, no. 95 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1973), p. 2.

35 Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/englisch_gg.html#p0723.

36 Germany, Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz [Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection], ‘Gesetz über die parlamentarische Beteiligung bei der Entscheidung über den Einsatz bewaffneter Streitkräfte im Ausland (Parlamentsbeteiligungsgesetz)’ [Act on Parliamentary Participation in Decisions on the Deployment of Armed Forces Abroad (Parliamentary Participation Act)], 18 March 2005, http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/parlbg/BJNR077500005.html.

37 Bastian Giegerich and Maximilian Terhalle, The Responsibility to Defend: Rethinking Germany’s Strategic Culture, Adelphi 477 (Abingdon: Routledge for the IISS, 2021), p. 43.

38 Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘Japan–U.S. Security Treaty’, 19 January 1960, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/n-america/us/q&a/ref/1.html.

39 Victor D. Cha, Powerplay: The Origins of the American Alliance System in Asia (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), p. 30.

40 Michael Leifer, The ASEAN Regional Forum: Extending ASEAN’s Model of Regional Security, Adelphi Papers, no. 302 (Oxford: Oxford University Press for the IISS, 1996), p. 9.

41 See chapter one in Christopher W. Hughes, Japan’s Re-emergence as a ‘Normal’ Military Power, Adelphi 368–369 (Abingdon: Routledge for the IISS, 2004), for a detailed discussion of the Yoshida Doctrine. Yoshida was also leader of the Liberal Party until its merger with the Japan Democratic Party in 1955 to form today’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

42 Hughes, Japan’s Re-emergence as a ‘Normal’ Military Power, p. 22.

43 Yoshida referred to this domestic split as a ‘38th parallel’, referencing the line of division between North and South Korea: ‘Nihon wa kokudo koso futatsu no Nihon ni bunkatsu sarenakatta keredo, kokumin no naka ni futatsu no Nihon ga umare, kokumin no aida ni sanjūhachi dosen ga hikareteiru to itte yoi’ [Although Japan has not been physically divided, two Japans have emerged within its people, and a 38th parallel has been drawn between them]. See Yoshida Shigeru, Ōiso Zuisō: Sekai to Nihon [Random Thoughts from Ōiso: The World and Japan] (Tokyo: Chūokōron-Shinsha, 2015), p. 214.

44 Akihiko Tanaka, ‘Rhetorics and Limitations of Japan’s New Internationalism’, Japanese Studies Bulletin, vol. 14, no. 1, 1994, pp. 3–33, especially p. 4.

45 Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘Kokkai ni Okeru Naikakusōridaijin Oyobi Gaimudaijin no Enzetsu’, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/bluebook/1987/s62-shiryou-101.htm; and Kenneth B. Pyle, ‘In Pursuit of a Grand Design: Nakasone Betwixt the Past and the Future’, Journal of Japanese Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, Summer 1987, pp. 243–70, especially p. 254.

46 Henry Scott Stokes, ‘Japanese Decide to Permit Export of Military Technology to the US’, New York Times, 15 January 1983, https://www.nytimes.com/1983/01/15/world/japanese-decide-to-permit-export-of-military-technology-to-the-us.html.

47 Clyde Haberman, ‘Japan Set to Join “Star Wars” Plan’, New York Times, 18 July 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/07/18/world/japan-set-to-join-star-wars-plan.html.

48 See Mayumi Itoh, ‘Japanese Constitutional Revision: A Neo-liberal Proposal for Article 9 in Comparative Perspective’, Asian Survey, vol. 41, no. 2, March–April 2001, pp. 310–27, for a detailed comparative analysis of Nakasone’s views on Japanese constitutional reform.

49 For example, Japan’s acquiescence to the 1985 Plaza Accord, described in the Introduction, and the US–Japan semiconductor trade agreement of 1986, which is described in more detail in Chapter One. See also Michael J. Green, By More than Providence: Grand Strategy and American Power in the Asia Pacific Since 1783 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), pp. 408–11.

50 Tanaka, Japan in Asia: Post-Cold-War Diplomacy.

51 This is well illustrated by the rise of the LDP’s Seiwa Seisaku Kenkyūkai faction in the late 1990s. Between 2001 and 2020, the faction produced four of the LDP’s six prime ministers in the period – Mori Yoshiro (2000–01), Koizumi Junichiro (2001–06), Abe Shinzo (2006–07 and 2012–20) and Fukuda Yasuo (2007–08). The faction traces its lineage back to the faction led by Abe Shinzo’s grandfather, Kishi Nobusuke, who was LDP prime minister in 1957–60, and it was founded in 1962 by Fukuda Takeo (prime minister in 1976–78). See also Christopher W. Hughes, Japan’s Foreign and Security Policy Under the ‘Abe Doctrine’ (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 9–11 for a detailed discussion of the rise of this faction.

52 Japan, Ministry of Defense, ‘The Guidelines for Japan–U.S. Defense Cooperation’, 23 September 1997, https://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11591426/www.mod.go.jp/e/d_act/us/anpo/pdf/19970923.pdf. See https://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11591426/www.mod.go.jp/e/d_act/us/anpo/pdf/19781127.pdf for the 27 November 1978 guidelines.

53 Hughes, Japan’s Re-emergence as a ‘Normal’ Military Power, p. 9.

54 Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘Campaign Against Terrorism: Japan’s Measures’, February 2002, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/n-america/us/terro0109/policy/index.html.

55 Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘The Issue of Iraq: Japan’s Assistance Measures’, December 2003, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/middle_e/iraq/issue2003/assistance/2003.html.

56 Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, ‘National Defense Program Guideline, FY2005’, 10 December 2004, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/policy/2004/1210taikou_e.html; Japan, Ministry of Defense, ‘Chūki Bōeiryoku Seibi Keikaku (Heisei 17 Nendo–Heisei 21 Nendo) Ni Tsuite’ [About the Mid-term Defence Plan, FY2005–FY2009], 10 December 2004, https://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11591426/www.mod.go.jp/j/approach/agenda/guideline/2005/chuuki.html.

57 ‘Explainer: Why Yasukuni Shrine Is a Controversial Symbol of Japan’s War Legacy’, Reuters, 15 August 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/why-yasukuni-shrine-is-con-troversial-symbol-japans-war-leg-acy-2021-08-13/.

58 The failure, owing partly to Chinese opposition, of Japan’s efforts in 2005 to expand the ‘ASEAN + 3’ grouping (which involved China, Japan and South Korea as well as the ten ASEAN member states) to include Australia, India and New Zealand was a good example of this. Tanaka, Japan in Asia: Post-Cold-War Diplomacy. ASEAN’s members are Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Fraught relations between Japan on the one hand and China and South Korea on the other also hindered preparations for the first East Asian Summit (involving the leaders of the ASEAN states, Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea) in 2005.

59 Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, ‘Policy Speech by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to the 166th Session of the Diet’, 26 January 2007, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/abespeech/2007/01/26speech_e.html.

60 Abe Shinzo, Utsukushii Kuni E [Towards a Beautiful Country] (Tokyo: Bunshun Shinsho, 2006), p. 28; and Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘Japan Is Back: Policy Speech by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo at the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS)’, 22 February 2013, https://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/pm/abe/us_20130222en.html.

61 ‘Milestone Congress Points to New Era for China, the World’, China Daily, 24 October 2017, https://www.china-daily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-10/24/content_33648051.htm; and Giulio Pugliese, ‘Kantei Diplomacy? Japan’s Hybrid Leadership in Foreign and Security Policy’, Pacific Review, vol. 30, no. 2, March 2017, pp. 152–68, especially p. 160.

62 Royama, The Asian Balance of Power: A Japanese View, p. 6.

63 See Robert Hoppens, The China Problem in Postwar Japan: Japanese National Identity and Sino-Japanese Relations (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 5–7, for a discussion of how Chinese policy has had an impact on Japanese national identity.

64 H.R. McMaster, ‘Japan: The Legacy of Japan’s Longest Serving Prime Minister’, Hoover Institution, 21 July 2021, https://www.hudson.org/research/17135-japan-the-legacy-of-japan-s-longest-serving-prime-minister. At around 9:25 minutes: ‘When we look back at history we see many instances and cases where one side had a misunderstanding and underestimated the will and capability of the other side, and that eventually led to confrontation or disputes. So, in that context I do believe that it remains very important for us to make China realise Japan’s determination and also have correct understanding about Japan’s capability, and that will remain the key.’

65 Coral Bell, The Asian Balance of Power: A Comparison with European Precedents, Adelphi Papers, no. 44 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1968), pp. 2–3.

66 Abe, Utsukushii Kuni E [Towards a Beautiful Country], p. 29. ‘Masa ni kempō no kaisei koso ga “dokuritsu no kaifuku” ga shōchō de ari’ [Constitutional revision is a symbol of ‘regaining independence’]; see also pp. 123–44.

67 Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘The 13th IISS Asian Security Summit – The Shangri-La Dialogue Keynote Address by Shinzo Abe, Prime Minister, Japan’, 30 May 2014, https://www.mofa.go.jp/fp/nsp/page4e_000086.html.

68 Robert Ward, ‘Japan’s Security Policy and China’, in Asia-Pacific Regional Strategic Assessment 2021: Key Developments and Trends (Abingdon: Routledge for the IISS, 2021), p. 39. The advantages conferred by Trump’s abrasive policy towards China were evident in an anonymous piece written by ‘Y.A.’, a Japanese official, in American Interest in April 2020. As Y.A. notes: ‘For countries on the receiving end of Chinese coercion, a tougher U.S. line on China is more important than any other aspect of US policy.’ Y.A., ‘The Virtues of a Confrontational China Policy’, American Interest, 10 April 2020, https://www.the-american-interest.com/2020/04/10/the-virtues-of-a-confrontational-china-strategy/. Henry Kissinger’s description of the role of a ‘balancer’ is also worth quoting in the context of the Japan–China–US triangle: ‘a balancer cannot perform his function unless the differences among the other powers are greater than their collective differences with the balancer’. Henry Kissinger, A World Restored (London: Phoenix Press, 1957), p. 31. See also Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew’s ‘isosceles triangle theory’, which held that ‘relations between Japan, the US and China are most stable when they take the form of an isosceles triangle. This means maintaining a triangular configuration in which US– Japan ties are closer than either Sino– Japanese relations or Sino–American relations.’ Cited by Funabashi Yoichi in ‘Foreign Policy Requires a Keen Sense of Balance’, Japan Times, 10 February 2017, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2017/02/10/commentary/japan-commentary/foreign-policy-requires-keen-sense-balance/.

69 See Abe, Utsukushii Kuni E [Towards a Beautiful Country], pp. 146–56 for discussion of his views on China. The quotation is from p. 151.

70 Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘Regarding Discussions toward Improving Japan–China Relations’, 7 November 2014, https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/c_m1/cn/page4e_000150.html; and Tsukasa Hadano, ‘Xi Jinping Set to Make First State Visit to Japan in April’, Nikkei Asia, 7 December 2019, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Interna-tional-relations/Xi-Jinping-set-to-make-first-state-visit-to-Japan-in-April.

71 Robert Ward, ‘Abe Shinzo’s Consequential Premiership’, 9 Dash Line, 10 September 2020, https://www.9dashline.com/article/abe-shin-zos-consequential-premiership.

72 See ‘Military–Civil Fusion Under Xi’, The Military Balance 2021 (Abingdon: Routledge for the IISS, 2021), pp. 19–21, for a detailed discussion of Chinese military–civil fusion policy. See also Meia Nouwens and Helen Legarda, ‘Emerging Technology Dominance: What China’s Pursuit of Advanced Dual-use Technologies Means for the Future of Europe’s Economy and Defence Innovation’, IISS–MERICS China Security Project, December 2018, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/181218_Emerging_technology_dominance_MERICS_IISS.pdf.

73 Bell, The Asian Balance of Power: A Comparison with European Precedents, p. 12.

74 ‘Poll: China Viewed Unfavourably by Most in Japan’, NHK World– Japan, 24 November 2020, https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/backstories/1390/.