Abstract

This paper explores the complex roles of aspirations in relation to human development, drawing upon the capability approach. The paper examines the notion of feasibility of aspirations and the impact feasibility judgements have on aspiration formation and aspiration realization, in terms of both capabilities and functionings. In particular this paper extends existing theory by building on Hart's dynamic multi-dimensional model of aspiration and Hart's aspiration set (2012. Aspiration, Education and Social Justice - Applying Sen and Bourdieu. London: Bloomsbury). The theorization builds on empirical work, undertaken in the UK, seeking to understand pupils’ aspirations on leaving school and college at age 17–19 as well as reviewing wider empirical and theoretical literature in this field. The discussion contributes to capability theory by extending understanding regarding first, the way that aspirations are connected to capabilities and functionings, secondly, the processes by which aspirations are converted into capabilities and thirdly, how certain capabilities become functionings. The paper reflects on the criteria that inform choices about the cultivation and selection of different aspirations on individual and collective bases. In concluding the paper the question of, “how do aspirations matter?” is addressed. Ultimately, an argument is made for the need to “reclaim” a rich multi-dimensional concept of aspiration in order to pursue human development and flourishing for all.

Introduction

Drawing on the capability approach, this paper is focused on building understanding of the nature of aspirations in relation to human development (Sen Citation1992, Citation1999). Outside of the capability literature, measures of aspiration have mainly been linked to educational and career-related achievements (Sewell and Shah Citation1968; Marjoribanks Citation1998, Citation2002; Carter Citation2001; Appadurai Citation2004; Hart Citation2004, Citation2012; Fuller Citation2009; Rose and Baird Citation2013; Hoskins and Barker Citation2014). According to Carter, “educational aspirations have mostly been studied as a predictor of a variety of outcomes, most notably in relation to education attainment and/or attrition” (Citation2001, 11).Footnote1 For example, comparisons have been made between fathers’ education and income and offspring’s aspirations for their own education and working lives (Blau and Duncan Citation1967).

UK policy discourses have similarly tended to position aspirations solely in terms of educational attainment and employment (HEFCEFootnote2 Citation2003, Citation2005, Citation2012; DfESFootnote3 Citation2003, Citation2006; Watts and Bridges Citation2004; Watts Citation2006; Hart Citation2012). A recent report by the National Careers Council for England argues for the need to, “encourage ambition and meet the needs of an aspirational nation where opportunity is not blocked by self-doubt, ignorance or confusion” (Citation2013, 12). The report goes on to note the “misalignment of the British youth labour market” judging that, “the ambitions of two in five young people were unrealistic, with young people from disadvantaged backgrounds being nearly twice as likely to suffer from such confusion as their more prosperous counterparts” (ibid., 8). Here misalignment is framed as “confusion” rather than a difference of priority.Footnote4 This constitutes a kind of hi-jacking and limited framing of aspiration in policy. British Prime Minister, David Cameron (Citation2012, speech, 10 October) has spoken of an “aspiration nation” seeking to shift individual goals towards filling labour market gaps through promises of economic reward, and the fear of unemployment. This narrow economic instrumental positioning of aspirations can be viewed as corrosive as it erodes the possibility and value of wider aspirations.

Assumptions are made in government discourses about the possibility of ranking and raising aspirations, but aspirations can relate to many aspects of life. The following quotes indicate some of the young people’s aspirations from Hart’s research (Citation2012), “I want to be debt-free;” “I want to get out of this city;” “I want to be a drug dealer;” “I want to be a good Muslim;” “I want to go to university;” “I want to find inner peace.” These contrasting and diverse aspirations, from young people in UK schools and colleges, resonate with Arun Appadurai’s view that, “aspirations are never simply individual. They are always formed in interaction and in the thick of life” (Citation2004, 67). Hoskins and Barker (Citation2014) found evidence of five common aspirations in their study of 15–19 year olds in two UK state secondary schools (N = 88) including making a difference, personal happiness, job satisfaction, status and wealth, indicating that educational and career aspirations were not the only aspirations deemed important. Indeed, there are many forms of aspiration and their roots and purposes vary significantly. For example, on a broader social level, space exploration may be motivated by national priorities for international status and recognition, whereas social movements may be driven by desires to transform society in pursuit of justice in some way. Ladwig, in Unterhalter, Ladwig, and Jeffrey (Citation2014) has argued that in policy arenas, “the rhetoric of aspiration ultimately serves as a diversion from the reality of increasing social exclusion and inequality” (140). Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation2000), Skeggs (Citation2005), Allen and Hollingworth (Citation2013), Reay, David, and Ball (Citation2005) and Reay (Citation1998, Citation2001), among many other notable sociologists, have all identified the reproduction of class relations through education despite the policy rhetoric. Fuller (Citation2009) concluded from her study of gender, class and aspirations that, “whilst class may indicate what economic resources a family has available it cannot tell us what values and aspirations a family or student has or whether ambitions or dreams will be realised” (161). It is argued here that for fully human development we need a multi-dimensional view of aspiration and a deeper understanding of the combination of influences that precede and shape aspirations and their relationship to capabilities and functionings.

What Are Aspirations?

Are they akin to hopes, wishes, dreams, ambitions and goals? Do they signal optimism for the future or pessimism about the present? Do they portray longings and yearnings for that which we are not, or cannot do, or do not have? Are aspirations grounded in rationality, emotion, idealism or pragmatism? The answers are not at all straightforward since there are many interpretations and applications of the notion of aspiration (Sewell and Shah Citation1968; Ray Citation2003; Appadurai Citation2004; Watts and Bridges Citation2004; Burchardt Citation2009; Fuller Citation2009; Ibrahim Citation2011; Hart Citation2012). In different contexts it might be argued that aspirations can be all of these things and more. I would argue that aspirations are future-oriented, driven by conscious and unconscious motivations and they are indicative of an individual or group’s commitments towards a particular trajectory or end point.

shows that an individual’s agency with regard to their aspirations may vary from high to low depending on whether their aspirations are in conflict with significant others (such as parents, teachers or senior co-workers). Individuals may enjoy different degrees of agency and control in relation to their aspirations and this is echoed by Slack (Citation2003). Some aspirations may have come about with apparently little influence from others, whilst some aspirations may stem from the strong persuasion of others, or dominant discourses that encourage particular aspirations. also illustrates that individuals may have short, medium and long-term aspirations and these may vary in importance both to the individual and to significant others. Furthermore the wave models changing or oscillating aspirations over time.Footnote5

Figure 1. Dynamic multi-dimensional model of aspirations (Hart Citation2004, 66).

Hart’s research (Citation2004, Citation2012) found that aspirations are held concurrently and are relational, they are dynamic, often connected to other aspirations held by the individual as well as by others. Aspirations are multi-dimensional, varying in importance and timescale. Aspirations may be latent (unarticulated, evolving, abstract and uncertain) and can surface suddenly or emerge slowly. Aspirations may, for example, be institutional, political, legal and shared by family members. Aspirations may relate to home, school, work, national or international life. Whilst aspirations are future-oriented they may also pertain to the continuity of a present state of being. For example, “I want to stay young,” “keep fit,” “be with you forever … .” Aspirations change.Footnote6 Not all aspirations are in the interests of others and some individuals’ aspirations may provoke criticism, harm or offence. Not all can be condoned in a morally just society that wishes to preserve the dignity of all.

The Capability to Aspire

An individual might set their aspirations in relation to what they know they can achieve or they might set aspirations more ambitiously to strive for ways of being and doing they are not sure of realizing. Some individuals might aspire in a non-specified way in terms of wanting “a better life,” whereas others might strive for specific transformative social change, such as a change in the law.

Hart’s UK study of 580 male and female students aged 17–19 found that one in four individuals reported having aspirations they had never shared with anyone else and a third of the young people said they were sometimes afraid to tell other people about their aspirations (Hart Citation2012). An individual’s revealed aspirations therefore only give a partial view of an individual’s “aspiration set” (Hart Citation2012). I have proposed that concealed, or unshared, aspirations may also form important elements of an individual’s aspiration set.Footnote7 Furthermore, aspirations are shaped and constrained by many factors but this is not necessarily readily apparent. Nussbaum observes, “habit, fear, low expectations and unjust backgrounds deform people’s choices and even their wishes for their own lives” (Nussbaum Citation2005, 114). Hence, both revealed and concealed aspirations may also include a sub-set of “adapted aspirations.”

Aspiring is a sentient and emotive process. Indeed, we are sentient beings—imagining how we fit, what we are capable of and how we feel. Where an individual is able to identify one or more aspirations that they hold, revealed or concealed, this offers evidence of the capability to aspire. Most individuals will be able to demonstrate the functioning of aspiring through the expression of one or more aspirations. However, this tells us little about the full range of the individual’s capability to aspire and constraints or oppressive roots of aspiration may not be readily explicit. Aspirations are often born out of unequal power relations that constrain humans to mould themselves in ways that suit perceived expectations of normalcy and acceptability. Thinking about future-oriented goals requires at least a basic level of capability in relation to being able to anticipate and imagine the future and exercise practical reason.Footnote8 Martha Nussbaum’s list of Central Human Capabilities (Citation2005, Citation2011) is immensely helpful in this respect; several capabilities in her list support the development of the complex capability to aspire.

Aspiration and Contentment

Whilst many individuals aspire to futures that differ from the present, some aspire for stability and for a continuation of how things are in the present. However, it may be even more difficult to maintain things as they are than to look to change. Even if we could “stay the same” the world around us is in flux. We are in a state of organic change, whether we are growing from birth to adulthood or gaining weight, the earth rotates, the leaves fall, science and technology advance, we grow older, humans and other species are born and die and all the while the evolution as well as the extinction of species continues. What was thought impossible yesterday, tomorrow may become part of a new shared reality and way of life. Our evolution and survival is at least in part dependent on the actions and aspirations of others. Thus, the ideas of aspiration and contentment (or tranquility) in relation to the status quo, may not necessarily be diametrically opposed. Southgate (Citation2012) argues we should aspire to a synthesis of aspiration and acceptance, a continuing tension, or “oscillation” between acceptance and aspiration (ibid., xi). Southgate suggests our mindset would be one or the other, aspirational or contented although it may be more nuanced than that. It is not a simple choice of aspiration or contentment but a constant process of decision-making. Indeed contentment is an aspirational goal. There may be some areas of life where at times one is content but others where an individual aspires to change (possibly due to shifts elsewhere, maturity, relationships, change in wealth or status and so forth). The same may be the case vice-versa, at one point a person may value fast cars and aspire to own one, then later in life they may become content to cycle everywhere because it keeps them fit and is less expensive. There will be some aspects of life where individuals are variously aspiring, accepting or unsure of their future desires. Moreover, contentment may reflect a dormant status where aspirations in these aspects of life might develop later, perhaps when conditions are more favourable (or again linked to different life stages and so on). Though there may be different reasons why an individual opts for “contentment” not all of these are necessarily positive. It may be an adapted preference due to little perceived prospect of change. Aspiration likewise may be born of ambition or optimism but also out of pessimism, frustration or the need to escape a present way of life.

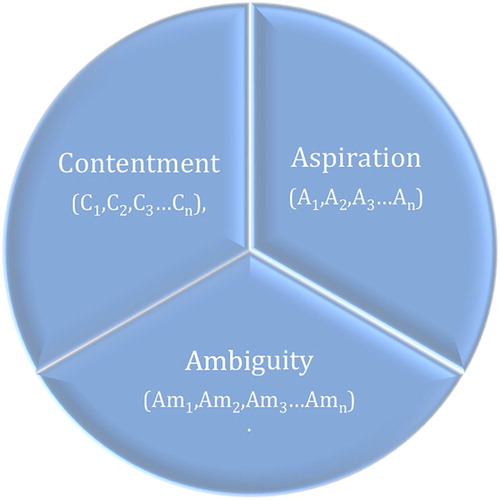

For example, Ray posits that failed aspirations may lead to fatalism (in other words, an acquiescent contentment). Someone may think it is impossible to change their social class and so does not aspire to do so. In another example, someone may reach what I term an “aspiration plateau” where they have no further aspirations perhaps due to significant accomplishments, past failure, ill health or other priorities. illustrates this conceptualization of the varying balance between aspiration, contentment and ambiguity that individuals may experience during their lives. The sets for contentment (C1, C2, C3, … , Cn), aspiration (A1, A2, A3, … , An) and ambiguity (Am1, Am2, Am3, … , Amn) aim to illustrate that there may be different roots of contentment, aspiration and ambiguity for different aspects of a given individual’s life.

Ray developed the idea of a multi-dimensional “aspiration window” and suggests that an, “individual draws her aspirations from the lives, achievements, or ideals of those who exist in her aspirations window” (Citation2003, 2). He argues that these aspirations may relate to many dimensions of life and that individuals might self-impose restrictions and/or weigh the odds of achieving certain goals, based partially on the observation of others. Hodkinson and Sparkes (Citation1996) have described “horizons for action” as another metaphor for the way in which individuals identify the zone of possible action in relation to the ways they might live their lives and the goals they seek to attain. The conceptualizations of Ray and Hodkinson et al. resonate with Bridges view that:

in choosing what they will do, how they will spend their time or resources or what kind of life they will lead people are affected by, or take into account, for example, what they can afford, the likely responses of others to their choice and the values and practices which shape them and the communities in which they live. (Bridges Citation2006, 1)

Ray also argues that the degree of social mobility in a society is likely to impact on the scale of the aspiration window, in other words if it looks like others similar to the individual succeed in achieving particular goals. Insightfully, Oyserman and Markus (Citation1990) concluded from their empirical studies that individuals imagine not only the future they want for themselves (aspirations) but also the “possible selves” they fear. They argue that avoiding certain kinds of futures is an important impetus for action alongside motivations to achieve desired “possible selves” (112).

Webb observes that, “there is no one definitive account of what it is to hope” (Webb Citation2007, 80). In his work on the nature of hope, Webb (Citation2008) has identified a typology of modes of hoping.Footnote9 Whilst hoping might be viewed as distinct from aspiring, I draw on just two of his modes of hoping to illustrate the way that individuals may enact aspiring based on different judgements of the possibilities of success. This is informative as I take the discussion forward in the next section to consider further how, as individuals and groups, decisions are made about what aspirations are developed in the first place, and whether these receive support in the phases of transition to first capabilities, and then functionings. Webb (Citation2008) describes “estimative hope” and “resolute hope” both as “hope directed toward an object of desire which is future-oriented and deemed to be of significance to the hoper” (203). The distinction comes in the behaviours associated with the two modes of hoping: estimative hopers identify, “some hopes may be worth the risk of actively pursuing if, on the basis of one’s probable estimate, these are deemed more than fair gambles” (ibid., 203). However, resolute hopers, “strive to realize goals that the estimative hoper would have dismissed as less than fair gambles” (ibid., 203). Whilst Webb’s modes of hoping are aligned with Ray’s idea of weighing up the odds it highlights that different individuals may approach the task in more or less risk averse ways. Indeed, Webb observes, “our hopes may be active or passive, patient or critical, private or collective, grounded in the evidence or resolute in spite of it, socially conservative or socially transformative” (Citation2007, 80). It is also the case, I suggest, that the same individual may be more or less risk averse in relation to different aspects of their life, or in relation to others, or in collective decision-making. Although I am not suggesting that aspiring is the same as hoping (though they bear similarities), this reflection becomes particularly significant when individuals are tasked with making judgements in relation to aspirations which affect individuals beyond themselves (a point to which I will return later).

Connecting Aspirations to Capabilities and Functionings

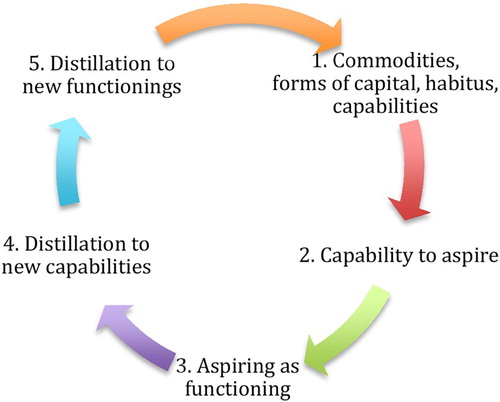

Having given a broad overview of my conceptualization of aspirations, I now move to consider how aspirations are connected to capabilities and functionings. It is not enough to look solely at the functioning of aspiring in order to understand an individual’s agency and freedom. It is also crucial to understand the degrees of freedom to aspire enjoyed by individuals, alongside the chances of transforming the aspiration into a capability. The functioning of aspiring arguably sits between the freedom to aspire and the capability to achieve the particular aspiration. Thus aspirations are powerfully situated as the forerunners to many capabilities ().

Aspirations widen the scope of understanding about what an individual has reason to value (beyond functionings and capabilities) but it still does not say much about the roots of values. Bourdieu argued that our (pre)dispositions may be strongly influenced by what he termed, habitus, cultural and other forms of capital, our interactions with others and the configurations of power relations in different fields that we encounter. Through processes of socialization individuals are inculcated with the traditions, customs, norms, values and practices of their families and communities. How deterministic these dispositions and influences are has been a question troubling sociologists for many years, but one that deserves attention as we think about aspiration and capability formation.

Bourdieu’s work complements Sen’s capability approach by offering a more dynamic interactive understanding of the conversion factors helping and hindering the development of aspirations and capabilities.Footnote10 The choice of aspirations might be influenced to varying degrees by what Bourdieu called the “habitus” of an individual. Habitus is related to the cultural and familial roots from which a person grows. Bourdieu explained that habitus, “operates below the level of calculation and consciousness” and that the, “conditions of existence” influence the formation of habitus which is manifested in the agent’s “tastes, practices and works thus constituting a particular lifestyle” (Citation2010, 167). “The habitus is necessarily internalized and converted into a disposition that generates meaningful practices and meaning-giving perceptions” (Bourdieu Citation2010, 166). This could impact on the kinds of aspirations that individuals, including those in roles of public office, find meaningful.

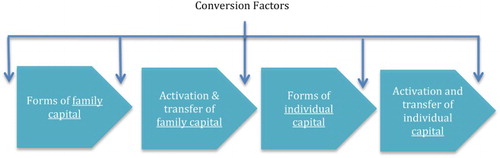

Bourdieu conceptualized different forms of capital rather than solely the economic form of capital used elsewhere (Citation1986). His conceptualization enriches understanding of the body of commodities and resources that may be converted into aspirations and capabilities.Footnote11 Bourdieu theorized that capital may be accumulated through intergenerational transfers of different forms of capital from adults to their offspring. This was linked to the possibility of a family drawing on one form of capital in order to generate another form. For example, economic capital might be converted into cultural capital through the purchase of books and immersion in culture-rich activities (e.g. music lessons). However it is important to note that access to, and activation of family capital varies among different individuals and is not guaranteed (Laureau and Horvat Citation1999; Marjoribanks Citation2002). In addition, Sen foregrounds the way that, “behaviour depends not only on our values and predispositions, but also on the hard facts of the presence or absence of relevant institutions, and on the incentives—prudential or moral—they generate” (Sen Citation2004, 43). He further argues that, “value formation is an interactive process” (ibid., 42) and, similarly, I would argue aspiration formation is an interactive process ().

Multiple conversion factors affect the freedom an individual has to aspire and the kinds of aspirations they develop. The conversion factors may include the interaction of an individual’s characteristics, values and dispositions, their forms of capital and resources, their social context and cultural influences as well as the physical setting with its structures and institutions, environmental features and location relative to other places and spaces of social action. Further conversion factors act to influence whether aspirations are transformed into capabilities and functionings. A distillation process occurs both from aspiration to capability and capability to functioning (). Whilst a large bundle of aspirations may be converted into capabilities for a given individual it will not necessarily be the case that all of these aspirations can be realized and certain functionings will preclude others. Ultimately, an aspiration set will include some but not all of the precursors to the capabilities an individual enjoys. Some capabilities will be enjoyed from birth or pre-aspiration—such as the freedom to live, to be treated with dignity, the freedom to play and so on.

The Judgement of Aspirations

Individual and significant others’ conscious and unconscious engagement in judgements regarding the feasibility of aspirations is pivotal in the development of capabilities, and it is to this matter that I now return. “Individual aspirations are born in a social context, they do not exist in a vacuum” (Ray Citation2003, 9). Some aspirations are mutually exclusive and do not affect anyone other than the aspirers but many others are mutually dependent or contrary to one another. These latter aspirations give cause to think further on how societies resolve which aspirations to support individuals and groups in pursuing at family, institutional, local, national and international levels. For example, in times of austerity, how should policy-makers cut public spending? What kinds of society do citizens aspire to support, and how can resources be channelled accordingly? Deciding which of multiple aspirations a community or society can, or should, pursue is complex. illustrates examples of different reasons why people may object to certain aspirations being pursued.

Table 1. Sample objections to the pursuit of aspirations

Ron Barnett, writing on the development of higher education, uses the concept of “feasible utopia.” He observes:

The real and the unreal, the concrete and the abstract, the here-and-now and the distant, the experienced and the imagined, the possible and the impossible: all these relationships, then, constitute the ground before us. And all these relationships and this ground are opened up by the idea of feasible utopias. A feasible utopia is just what is indicated by the phrase; a utopia that is also feasible. (Barnett Citation2013, 26)

This concept of feasible utopia is helpful in illuminating the space between here and there, between the present state of affairs and the transcendental sublime, perhaps idealistic future. The suggestion that we should reach far, but not too far is appealing. But who should decide where is far enough? What criteria are to be used? How are disagreements or uncertainties to be addressed? How do we make choices about aspiration formation, transformation to capabilities, and transformation of capabilities to functionings? Judgements of the feasibility of aspirations may impact on the formation of aspirations in the first place. They also impact on the way in which resources are mobilized, support and encouragement given, and the self-belief of individuals and groups of aspirers.

Sen has proposed that establishing mechanisms for democratic deliberation is vital (Citation1999) but thereafter what strategies might be advocated? There is a trend in the UK towards “evidence-based” practice and this is similar in many other national and international contexts. Thus the criteria for feasibility of, for example, funding a drug trial, medical intervention or medicine are dependent on robust clinical evidence, “value for money” and so on (NICEFootnote12 Citation2013). Such evidence-based criteria are responsive to demands for accountability in the way that limited financial, human and other resources are deployed for the perceived public good. This may make it difficult for individuals or collectives to act as “resolute hopers” as described earlier, drawing on Webb (Citation2008).Footnote13 Second-guessing is common at the pre-aspiration formation stage as well as in the stage between aspiration formation and the pursuit of conversion to capability and functioning. This happens at the level of the individual, and at the macro social level. Indeed, there are three crucial stages at which judgements about feasibility impact on aspiration formation, first, pre-aspiration, secondly, aspiration-capability conversion factors and thirdly, the combinations of functionings determined to be feasible. Who is making decisions, their statuses, the roles they play and the identification and cultivation of aspirations and capabilities are all crucial elements in the way societies develop and individuals are able to achieve well-being. The three stages are briefly summarized here before going on to further explore collective judgements regarding aspirations, feasibility and wider society.

Pre-aspiration

The cultivation of aspirations is dependent on the freedom individuals feel they have to aspire, who dares to share or voice their aspirations and how those individuals are judged by others. Work by Hart (Citation2012), Ibrahim (Citation2011) and others has shown that some individuals are much less likely than others to risk imagining or voicing their aspirations. For example, in a study of 29 law students in the first few weeks of their first semester, Carroll and Brayfield (Citation2007) report that they found disparities in aspirations based on gender. Women had lower expectations for their career trajectories than did men (225). Expectations of women continued to lower as they progressed through Law school, at the end of the first year. Another study by Mettler (Citation2014) found evidence that low-income high achievers less familiar in higher education performance and application strategies, did not apply to elite institutions in the same numbers as their more affluent peers.

Aspiration to Capabilities

One research participant in Hart’s (Citation2012) research talked about getting “a reality check” as they got older. There is a suggestion that there are boundaries for a given individual, and that over time one becomes more aware of where the boundaries lie. Different players have roles in the social construction of the boundaries of what might be possible and once lines are drawn in the sand about what is and is not possible they may be hard to change. But as James Baldwin so eloquently points out:

the impossible is the least that one can demand—and one is after all, emboldened by the spectacle of human history in general, and American Negro history in particular, for it testifies to nothing less than the perpetual achievement of the impossible. (Baldwin Citation1963, 104 in Johnson 2002)

Perceptions of feasibility are arguably subjective and we see pervasive racial, gendered and class-based inequalities in terms of who is seen to be suitable for senior roles and who gets chosen, for example, for the judiciary, senior academic roles or political office (Sutton Trust Citation2009).

Choosing Combinations of Functionings

Certain functionings may preclude others so that even where a wide degree of freedom exists, only particular combinations of functionings can be possible since, on the one hand, there is only so much one person, organization or nation can do with finite resources. On the other hand, combinations of functionings at the individual and macro levels ideally need to fit with wider social conditions and the aspirations of others.

Aspirations, Feasibility and Wider Society

Committees, community groups and democratically elected political representatives invoke different methods for determining policy in relation to public aspirations, including those of majority and minority groups. There is little evidence of how individuals or collectives give weight to different aspirations, or how they judge the potential of different combinations of functionings. The decision maker’s position and role are significant. Position refers here to title and function, for example as teacher, parent, chief executive, politician. Role refers here to the manner adopted by the individual to carry out the positional duties. So, for example, this might be as a compassionate (or dictatorial) leader or philanthropist (or mercenary), other-regarding (or self-regarding) on a local, national or international scale. Habitus is constituted by an individual’s embodied dispositions manifested in the way they view the world. Thus different individuals may judge different aspirations, and in turn different combinations of functionings, as more or less appropriate.

Magone in Vogel (Citation2012) observes that:

humanitarian action has always been trying to find a shared interest with the powers that be. In other words the manipulation of aid is not a misuse of its vocation but a necessary condition of its existence … [there is] little public discussion about the benchmarks against which to judge acceptable from unacceptable compromises. (1)

This illustrates that judgements about which aspirations to pursue may not be made in isolation but in relation to the perceived necessity to comprise. summarizes some of the criteria that might be used to inform such judgements, illustrating the idiosyncratic nature of the judgement process. It is argued here that the way that each individual reaches their judgement has to date been under-theorized in terms of the subjectivities and power dynamics at play. In addition, the social choice literature has foregrounded the difficulty in aggregating individually rationalized preferences (Sen Citation1977; Arrow, Sen, and Suzumura Citation1997).

Table 2. Examples of criteria used to judge aspirations

A crucial question is to what extent should criteria such as those outlined in influence judgements about the validity and choice of aspirations that are to be encouraged and supported? Even if it was thought that a set of criteria was helpful, Nussbaum argues feasibility should not determine aspirations (Citation2015) but that aspirations should drive action. I agree that aspirations can act as powerful engines of progress and that we should absolutely not be limited in relation to the current status quo. For example in relation to civil rights (e.g. African-American civil rights movement), human endeavor (e.g. landing on the moon), sporting achievement (e.g. the four minute mile), changing the law (e.g. abolishing slavery, equal voting rights for men and women) and so forth. Changes would not have occurred without pushing the limits of what was known to be possible. So asking whether an aspiration is “feasible” does not necessarily help in determining whether or not to support it. Similarly, in judging how “risky” an aspiration is, different individuals will potentially draw varied conclusions. So whilst the criteria in are offered as a model for reflection, it is by no means being suggested that they ought to be directive. Having said that Zak’s observation may be of concern to some that, “people will invest scarce cognitive resources in solving a decision problem only when the expected pay-off is sufficiently large” (55). Zak argues people are rationally rational in that they will only put the effort into rationalizing decisions when it is “worth” it (Zak Citation2011a). It might be that a greater awareness of the strategies, knowingly and unknowingly invoked, could reduce the often arbitrary nature of the judgement and pursuit of aspirations. It also might help decision-making bodies articulate the manner in which they have reached judgements about aspirations and related policies. For example, whether they are highly aspirational as Nussbaum advocates (Citation2015) or low-risk options that might bring limited change.

Negotiation and Trade-offs

We also need to understand what the “non-negotiables” (hard lines) are when looking at feasibility. When a parent says no, when an employer asks for a qualification we do not possess, when a post is advertised full-time and not as a job share—some might be better at negotiating than others, thus bending the boundary for feasibility. Here is how Medicin Sans Frontiers approaches negotiation:

Negotiation frameworks do not include universal markers indicating the line that must not be crossed: and MSF must therefore pay attention to the developing dynamic of each situation and to its own ability to revoke compromises that were only acceptable because they were temporary’ … for example, keeping silent about oppressive policies in the interests of gaining access to a population. (Magone in Vogel Citation2012, 1)

Trade-offs are common to secure what is perceived as the best possible combination of functionings even though this may result in a significant sacrifice.

An example of a political trade-off comes from Medicins Sans Frontiers who commented, “if you take sides in Somalia, for example, your operations in Pakistan and Afghanistan will certainly be affected” and they report that by not criticizing, “MSF was able to carry off a large-scale HIV treatment program that otherwise might not have been possible” (Vogel Citation2012, 2).

In another example Deprez and Butler (Citation2007) consider women’s access to higher education in the USA. They observe that welfare reforms have limited low-income access to higher education, particularly among females. In this case the trade-off for welfare reforms is that gender inequalities in access to higher education have been allowed to rise. It is possible that this is an unintended consequence of the policy change but nonetheless a trade-off occurs illustrating the interconnectedness of aspirations across different aspects of social life.

Fitzgerald asks, can we create a system, “within which cooperative stakeholders can interact while promoting the identification of mutually satisfactory and ‘fair’ solutions, ideally one that minimizes the ability of the participants to ‘game’ the system in their favor” (Citation2013, 344). An example is provided by looking at compromise solutions between conservation and road-building in the tropics. Tropical and sub-tropical countries, contain most of the world’s biodiversity and a wealth of other natural resources” (Caro et al. Citation2014, 1). But development projects requiring road-building and other structures can threaten the flora and fauna. Compromises to protect biodiversity whilst supporting economic development might include rerouting roads to, “bypass wildlife concentrations,” “travelling at slow speeds,” closing roads at night and having trucks travel in convoy to minimize disruption (ibid., 4). This might be one way to approach working to find a solution when there are multiple possibilities for combinations of functionings for a given community. Zak (Citation2011a) argues that, “we are indisputably interested in bettering our own conditions. At the same time, human beings show an enormous amount of care and concern to others, often at a cost to themselves” (53). In making judgements, Zak (Citation2011b, 212) argues that, “most people, most of the time behave morally” and that, “fellow-feeling or empathy appear to motivate us toward virtue and away from vice.” Indeed, Bendor, Mookherjee, and Ray (Citation2001) argue that cooperation will give the best return to two parties and that more progress is made through compromise than through occasional deviations to advantage oneself as it leads to retaliation on the part of the other. On the other hand, game theory concerns itself with “fully competitive self-interested behaviour” (Von Neumann and Morgenstern in Fitzgerald and Ross Citation2013, 344) and the way individuals or businesses operate driven by self-interest. It has been argued by Nyberg and Wright (Citation2013) that rather than protecting the environment, often corporate sustainability initiatives actually serve to, “facilitate the social corruption of the social good of the environment and its conversion into a market commodity” (405).

According to Zak it seems that the institutional context is also important since he argues that, “moral sentiments can be promoted or inhibited by the organizational environment in which one finds oneself” (Citation2011a, 62) and “designing institutions to foster trust and happiness is an important goal” (ibid., 63). So perhaps what this brief survey of the literature illustrates is that specific individuals may have a propensity to be self-interested, other-interested or be prepared to seek compromise. However, these individuals’ dispositions may be influenced both by long-standing habitus, and cultural preferences, as well as by the contemporaneous environment in which they find themselves.

How Do Aspirations Matter?

Aspirations matter as signifiers of what has come to have meaning and value for us, as individuals, or as social groups. They offer guidelines and navigational reference points, lode stars for action. However, aspirations in themselves tell us little about the histories, power dynamics and discourses, norms, values and cultures that have shaped, enhanced, diminished and adapted them. As Bourdieu reminds us our predispositions may be strongly influenced by habitus, cultural and other forms of capital, our interactions with others and the configuration of power relations in a given field or social context. Thus aspirations mean little without origins and location in existing power structures, legal entitlements, customs and social practices, institutional and national priorities. The individual’s position in the power structures will be significant alongside their role as philanthropist, judge, manager and so forth.

Aspirations matter because they are a manifestation of the freedom to aspire which is valuable for human flourishing in its own right. Aspirations also arguably constitute the kernels or precursors of many important capabilities which support human flourishing. The stifling or constraint of aspiration is ultimately linked to the constraint of at least some capability or other. The kinds of aspirations we have influence the kinds of capabilities for which we strive. Thus control in the development of aspirations can indirectly impact on an individual’s well-being freedom.

Group aspirations enable change to occur where individuals alone would falter. For example, by calling on governments to secure rights for minority groups, ensure legal protection and entitlements, offer foreign aid, act sustainably, refrain from developing or using nuclear weapons, pay the living wage, and to advocate for those unable to do so themselves. Social aspirations can set the course of public action, policy, investment, regulation, legislation or act as a rallying cry for justice and freedom. But whilst social aspirations can galvanize families, communities and nations, they can also polarize them. Communal or dominant social aspirations are not always good and we have seen this in relation to the persecution and subordination of minority or vulnerable groups in different societies throughout history. So not all shared aspirations have the public good or social justice at their heart and there may well be conflicting individual and shared aspirations within any given community. Thus group aspirations arguably matter for social justice only in as much as the benefits accruing in the pursuit and realization of the aspirations are distributed equitably, and the costs and risks borne are equitably shared. All too often corporate, civic, national and global dreams have been realized through the unjust hardship of particular sections of society. In turn those who have made the greatest sacrifice have not enjoyed the fruits of their labour.

Concluding Remarks: The Future of Human Development

This paper has provided a stimulus for reflecting on and evaluating individual and collective practices in aspiration formation, cultivation and transformation. How individuals approach their roles as educators, policy-makers, parents and lawmakers is influenced by how aspirations are conceptualized. Acknowledging that not all aspirations can be realized and that choices have to be made, the discussion presented here challenges policy-makers and other community representatives to be more explicit about the criteria by which aspirations are both judged and determined. Whose aspirations have the right to flourish above others? Who should have agency over children’s aspirations? How should judgements be made about which aspirations are to be constrained as not in the public interest? If governments take on the role of determining and shaping aspirations, then what is a just basis for that evaluation?

Feasibility is subjective, social situated (alongside other competing priorities of the individual, others known and unknown, institutions, governments and so forth). Feasibility varies according to the agent, for example, their know-how, contacts, ability to mobilize resources and different forms of capital, ability to trouble-shoot and problem-solve will differ. Thus in principle it is fine to set the aspiration bar high but we need to develop effective strategies,Footnote14 and milestones en route, to support the pursuit of those aspirations.

The capability approach enables us to articulate aspirations in a way that helps to counter narrow policy discourses on aspirations. In concluding this paper I suggest that aspirations are vital to human development and yet their complexity presents a number of challenges. There are challenges related to the development and protection of the freedom to aspire, the challenge of supporting the transformation of aspirations into capabilities, the dilemmas related to the judgement of feasibility and the roles of aspiring in relation to both capability and functioning.

Humans have achieved many seemingly impossible dreams underlining the difficulty of determining feasibility in a just manner. Indeed, the roles of science and technology are constantly challenging what may be possible in human endeavours. This may ultimately broaden the focus of attention on feasibility to include wider ethical issues, for example regarding artificial intelligence and the impact of our aspirations on other humans, other species and the natural world. Advances in science, medicine and technology call upon us to think cautiously about the consequences of our actions today and into the future. Although we may have the power to fulfil our own aspirations there is a moral question about the impact on the freedom of others to live long, healthy and flourishing lives.

(Re)claiming a rich conceptualization of aspiration may help to inform efforts aimed at the development of socially just societies where all individuals are able to flourish. Diverse academic disciplines, and multicultural perspectives, can contribute towards the enrichment of our understandings of the complex phenomenon of aspiration. Whilst aspirations have most often been judged against economic criteria, if we want to learn more about the social context of aspirations we need to look to other disciplines to strengthen our insights. Amartya Sen in Culture and Public Action, asked in a paper by the same name, “How does culture matter?” In that paper Sen argued against the “heroic over-simplification” (Sen Citation2004, 38) of the role of culture. Here I have endeavoured to argue against an over-simplification of the roles of aspiration in human development. I look forward to continuing the conversation.

Limitations

This paper presents a rich conceptualization of aspirations, their formation, and the processes by which they may, or may not, be transformed into capabilities and functionings. The work is informed by a range of literature within and beyond the capability approach and it draws on empirical work conducted in the UK with young people transitioning from school and college to the wider world. I have also proposed a model for reflecting further on the ways in which individuals and groups might think about the merits of particular aspirations and why they might favour some over others. This model is conceptual and unlikely to be exhaustive, but rather indicative of the strategies that inform common practices in decision-making, consciously and unconsciously. Further research is needed to test this reflexive model in different contexts but in the first instance the aim is to stimulate debate in an important yet under-researched field. I have not been able to give much needed attention to questions of weighting or aggregation of individual preferences during collective decision-making processes. Indeed, the problems of the aggregation, comparison and ordering of preferences, and choices, have been taken up in the social choice theory literature by others much better placed to do so (Sen Citation1977; Arrow, Sen, and Suzumura Citation1997). Suffice it to say here that if individuals and groups were to become more aware and reflexive about the means by which they arrive at aspiration preferences, both on an individual and collective basis (and pertaining to themselves as well as to others’ aspirations), this might have the possibility of reducing some of the prejudice in developing and realizing aspirations that often exists between social groups, across the life course and with regard to different national and international contexts. Human development might be the better for it.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on a keynote paper I presented at the Aspirations Symposium of the Human Development and Capability Association annual conference held at Georgetown University, Washington, DC on 10 September 2015. I am grateful to the many colleagues and friends who have discussed ideas in this paper, within the HDCA and beyond. Special thanks to Ollie, Jasmine and Martha.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

About the Author

Caroline Sarojini Hart is a Lecturer in Education Studies at the University of Sheffield, Affiliated Lecturer at the University of Cambridge and a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge where she began her research into the nature of aspirations. Her recent research has focused on the roles of aspirations, education and health in human development and the pursuit of social justice. Caroline is an advocate of inter-disciplinary approaches in addressing human development challenges in a dynamic global context. She is currently Education Officer of the Human Development and Capability Association.

Notes

1. Carter analysed over 50 studies of aspirations to examine the concepts and measurements used. She highlights disparities in the realization of aspirations particularly in relation to race and ethnicity.

2. Higher Education Funding Council for England.

3. Department for Education and Skills, a former UK government department.

4. Later in this paper the issue of who should judge aspirations and the criteria for such judgements will be further explored.

5. The dynamic multi-dimensional model of aspiration was developed in light of empirical work conducted in England in 2003–2004 (Hart Citation2004). The survey sample included 14–17 year olds in an 11–18 comprehensive school in Bradford (N = 238, 82% response rate).

6. In other work I have considered the implications of adapted preferences on the formation and conversion of aspirations. This issue has also been taken up by others, see for instance Bridges (Citation2006).

7. An aspiration set will include some but not all of the precursors to the capabilities an individual enjoys. Some capabilities will be enjoyed from birth or pre-aspiration, the freedom to life, to be treated with dignity, live in a Malaria-free country, etc.

8. Imagination and practical reason are both on Nussbaum’s list of central capabilities.

9. See Webb (Citation2007, Citation2008, Citation2009) for more detail on modes of hoping and the relationship of hoping to utopias. His work offers a fascinating insight into literature on these subjects with potential to inform thinking on the nature of aspiring, aspirations and capabilities.

10. See Hart (Citation2012, 49–64) for further elaboration.

11. Economic capital may be generated through inherited wealth, family income or engagement in the economy for financial return. Social capital is accrued through social networks, the family and wider community interactions. Symbolic capital is manifested as individual prestige and authority (Bourdieu Citation1986). In terms of cultural capital, Bourdieu explained:

Cultural capital can exist in three forms: in the embodied state, i.e., in the form of long-lasting dispositions of the mind and body; in the objectified state, in the form of cultural goods (pictures, books, dictionaries, instruments, machines, etc.), which are the trace or realization of theories or critiques of these theories, problematics, etc.; and in the institutionalized state, a form of objectification which must be set apart because, as will be seen in the case of educational qualifications, it confers entirely original properties on the cultural capital which it is presumed to guarantee. (Bourdieu Citation1986, 7)

12. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is a public body under the auspices of the UK Department of Health.

13. I was intrigued recently to hear how Sir David Attenborough had pursued his aspiration, in 1956, to film a Komodo dragon in its natural habitat. He was uncertain of how to get to the remote Indonesian island of Komodo, what means of transport might be available to get there and whether the film equipment and crew could survive the conditions. He recounted an incredible journey which on the face of it seemed unfeasible, risky and ethically questionable (Attenborough Citation2016).

14. See Hart (Citation2014) for further discussion of conversion factors and structures, processes and techniques of transition (scoping, mapping, planning and navigation). “Possible combinations of functionings are mediated by synchronous and asynchronous configurations of conversion factors that shape the degree to which the individual is able to convert resources and other forms of capital into aspirations, capabilities and, ultimately, functionings” (Hart Citation2014, 201).

References

- Allen, K., and S. Hollingworth. 2013. “Social Class Place and Urban Young People’s Aspirations for Work in the Knowledge Economy: ‘Sticky Subjects’ or ‘Cosmopolitan Creatives’?” Urban Studies 50 (3): 499–517. doi: 10.1177/0042098012468901

- Appadurai, A. 2004. “The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition.” In Culture and Public Action, edited by V. Rao and M. Walton, 59–84. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Arrow, K. J., A. Sen, and K. Suzumura. 1997. “Social Choice Re-examined Volume I.” Proceedings of the IEA conference held at Schloss Hernstein, Berndorf.

- Attenborough, D. 2016. “Zoo Quest in Colour.” BBC 4, M. Gunton (Executive Producer) & A. Schofield (Producer), BBC’s Natural History Unit, May 11, 2016.

- Baldwin, J. 1963. “The Fire Next Time.” In Acres of Aspiration—The All-black Towns in Oklahoma, edited by H. B. Johnson (2002), 104. Fort Worth: Eakin Press.

- Barnett, R. 2013. Imagining the University. London: Routledge.

- Bendor, J., D. Mookherjee, and D. Ray. 2001. “Aspiration-based Reinforcement Learning in Repeated Interaction Games: An Overview.” International Game Theory Review 3 (23): 159–174. doi: 10.1142/S0219198901000348

- Blau, P. M., and O. D. Duncan. 1967. The American Occupational Structure. New York: Wiley & Sons.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In A Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

- Bourdieu, P. 2010. Distinction. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P., and J.-C. Passeron. 2000. Reproduction in Education, Society & Culture. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Bridges, D. 2006. “Adaptive Preference, Justice and Identity in the Context of Widening Participation in Higher Education.” Ethics and Education 1 (1): 15–28. doi: 10.1080/17449640600584946

- Burchardt, T. 2009. “Agency Goals, Adaptation and Capability Sets.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 10 (1): 3–19. doi: 10.1080/14649880802675044

- Cameron, D. 2012. “Prime Minister’s Speech on Aspiration Nation.” Conservative party conference, Birmingham, UK, October 10.

- Caro, T., A. Dobson, A. J. Marshall, and C. A. Peres. 2014. “Compromise Solutions Between Conservation and Road Building in the Tropics.” Current Biology 24 (16): R722–R725. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.007

- Carroll, C., and A. Brayfield. 2007. “Lingering Nuances: Gendered Career Motivations and Aspirations of First-year Law Students.” Sociological Spectrum 27: 225–255. doi: 10.1080/02732170701202709

- Carter, D. F. 2001. A Dream Deferred?: Examining the Degree Aspirations of African American and White College Students. New York: Routledge Falmer.

- Department for Education and Skills. 2003. White Paper: The Future of Higher Education. London: DfES.

- Department for Education and Skills. 2006. Widening Participation in Higher Education. Nottingham: DfES.

- Deprez, L. S., and S. S. Butler. 2007. “The Capability Approach and Women’s Economic Security: Access to Higher Education under Welfare Reform.” In Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach and Social Justice in Education, edited by M. Walker and E. Unterhalter, 215–236. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fitzgerald, M. E., and A. M. Ross. 2013. “Guiding Cooperative Stakeholders to Compromise Solutions Using an Interactive Tradespace Exploration Process.” Procedia Computer Science 16: 343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2013.01.036

- Fuller, C. 2009. Sociology, Gender and Educational Aspirations: Girls and Their Ambitions. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hart, C. S. 2004. “A Study of Students’ Aspirations and Needs in Relation to Aim Higher Widening Participation Policy.” MPhil thesis, University of Cambridge.

- Hart, C. S. 2012. Aspirations, Education & Social Justice—Applying Sen & Bourdieu. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hart, C. S. 2014. “Agency, Participation and Transitions Beyond School.” In Agency and Participation in Childhood and Youth—International Applications of the Capability Approach in Schools and Beyond, edited by C. S. Hart, M. Biggeri, and B. Babic, 181–203. London: Bloomsbury.

- Higher Education Funding Council for England. 2003. HEFCE Strategic Plan 2003–2008. London: HEFCE.

- Higher Education Funding Council for England. 2005. Young Participation in Higher Education. London: HEFCE.

- Higher Education Funding Council for England. 2012. Statement on Widening Participation. Accessed January. www.hefce.ac.uk.

- Hodkinson, H., and A. Sparkes. 1996. Triumphs and Tears: Young People, Markets and the Transition from School to Work. London: David Fulton Publishers.

- Hoskins, K., and B. Barker. 2014. Education & Mobility—Dreams of Success. London: Trentham Press.

- Ibrahim, S. 2011. Poverty, Aspirations and Wellbeing: Afraid to Aspire and Unable to Reach a Better Life—Voices from Egypt. BWPI Working Paper No. 141, University of Manchester.

- Laureau, A., and E. M. Horvat. 1999. “Moments of Social Inclusion and Exclusion, Race, Class and Cultural Capital in Family School Relationships.” Sociology of Education 72: 37–53. doi: 10.2307/2673185

- Magone, C. quote in Vogel, L. 2012. “The Art of Necessary Compromise.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 184 (5): E252, 1–2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4131

- Marjoribanks, K. 1998. “Family Background, Social and Academic Capital and Adolescents’ Aspirations: A Mediational Analysis.” Social Psychology of Education 2: 177–197. doi: 10.1023/A:1009602307141

- Marjoribanks, K. 2002. Family and School Capital: Towards a Context Theory of Students’ School Outcomes. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Mettler, S. 2014. Degrees of Inequity. Philadelphia, PA: Perseus Books Group.

- National Careers Council. 2013. “An Aspirational Nation—Creating a Culture Change in Careers Provision,” June.

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). 2013. “Judging Whether Public Health Interventions Offer Value for Money (NICE).” https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/lgb10/chapter/introduction.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 2005. “Capabilities as Fundamental Entitlements: Sen and Social Justice.” In Amartya Sen’s Work and Ideas—A Gender Perspective, edited by B. Agarwal, J. Humphries, and I. Robeyns, 35–62. London: Routledge.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 2011. Creating Capabilities. The Human Development Approach. Harvard: Belknap, Harvard University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 2015. “Aspiration and the Capabilities List.” Aspiration Symposium, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, September 10.

- Nyberg, D., and C. Wright. 2013. “Corporate Corruption of the Environment: Sustainability as a Process of Compromise.” The British Journal of Sociology 64 (3): 405–424. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12025

- Oyserman, D., and H. R. Markus. 1990. “Possible Selves and Delinquency.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59 (1): 112–125. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.1.112

- Ray, D. 2003. Aspirations, Poverty and Economic Change. New York: New York University and Instituto de Analisis Economico (CSIC).

- Reay, D. 1998. “‘Always Knowing’ and ‘Never being Sure’: Familial and Institutional Habituses and Higher Education Choice.” Journal of Education Policy 13 (4): 519–529. doi: 10.1080/0268093980130405

- Reay, D. 2001. “Finding or Losing Yourself: Working Class Relationships to Education.” Journal of Education Policy 16 (4): 333–346. doi: 10.1080/02680930110054335

- Reay, D., M. David, and S. Ball. 2005. Degrees of Choice: Class, Race, Gender and Higher Education. Stoke on Trent: Trentham.

- Rose, J., and J.-A. Baird. 2013. “Aspirations and an Austerity State: Young People’s Goals for the Future.” London Review of Education 11 (2): 157–173. doi: 10.1080/14748460.2013.799811

- Sen, A. K. 1977. “Social Choice Theory: A Re-examination.” Econometrica 45 (1): 53–89. doi: 10.2307/1913287

- Sen, A. K. 1992. Inequality Re-examined. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sen, A. K. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. K. 2004. “How Does Culture Matter.” In Culture and Public Action, edited by V. Rao and M. Walton, 37–58. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Sewell, W. H., and V. P. Shah. 1968. “Socioeconomic Status, Intelligence and the Attainment of Higher Education.” Sociology of Education 40 (1): 1–23. doi: 10.2307/2112184

- Skeggs, B. 2005. “The Making of Class and Gender Through Visualizing Moral Subject Formation.” Sociology 39: 965–982. doi: 10.1177/0038038505058381

- Slack, K. 2003. “Whose Aspirations Are They Anyway?” The International Journal of Inclusive Education 7 (4): 325–335. doi: 10.1080/1360311032000110016

- Southgate, B. 2012. Contentment in Contention: Acceptance Versus Aspiration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sutton Trust. 2009. The Educational Backgrounds of Leading Lawyers, Journalists, Vice Chancellors, Politicians, Medics and Chief Executives. The Sutton Trust (Submission to the Milburn Commission on Access to the Professions).

- Unterhalter, E., J. Ladwig, and C. Jeffrey. 2014. “Decoding Aspirations: Social Theory, the Capability Approach and the Multiple Modalities of Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 35 (1): 133–145 ( Review Symposium: Aspirations, Education and Social Justice. Hart, C. S., London: Bloomsbury). doi: 10.1080/01425692.2013.856669

- Vogel, L. 2012. “The Art of Necessary Compromise.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 184 (5): E252–E253. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4131

- Watts, M. 2006. “Disproportionate Sacrifices: Ricoeur’s Theories of Justice and the Widening Participation Agenda for Higher Education in the UK.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 40 (3): 301–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9752.2006.00525.x

- Watts, M., and D. Bridges. 2004. Whose Aspirations? What Achievement? An Investigation of the Life and Lifestyle Aspirations of 16–19 Year Olds Outside the Formal Education System. Cambridge: Centre for Educational Research and Development, Von Hugel Institute.

- Webb, D. 2007. “Modes of Hoping.” History of the Human Sciences 20 (3): 65–83. doi: 10.1177/0952695107079335

- Webb, D. 2008. “Exploring the Relationship Between Hope and Utopia: Towards a Conceptual Framework.” Politics 28 (3): 197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2008.00329.x

- Webb, D. 2009. “Where's the Vision? The Concept of Utopia in Contemporary Educational Theory.” Oxford Review of Education 35 (6): 743–760.

- Zak, P. J. 2011a. “The Physiology of Moral Sentiments.” Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organisation 77: 53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2009.11.009

- Zak, P. J. 2011b. “Moral Markets.” Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organisation 77: 212–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2010.09.004