ABSTRACT

Childhood poverty matters—not only because of the disturbingly high number of children affected, but also because of the deleterious impact on their human flourishing, both now and in the future. Effectively addressing child poverty requires clear identification of the nature and causes of the problem, as well as an understanding of how it is experienced. This paper aims to deepen understanding of child poverty, by drawing on key elements of a capability approach, rights-based approaches, and feminist standpoint theory, and empirical research. It is grounded in the findings of rights-based, participatory research with children aged between 7 and 15 years in Indonesia and in Australia, which cast new light on the dimensions of poverty that are most egregious from a child-driven standpoint. It presents a three-dimensional typology of material, opportunity, and relational poverty.

1. Introduction

Child poverty is an issue of global concern; not only because of the disturbingly high number of children affected (Alkire Citation2019, 35–36; World Bank Citation2016, Citation2020), but also because of the deleterious impact on their human flourishing and wellbeing, both now and in the future. White, Leavy, and Masters (Citation2003, 80) argue that child development is foundational to all aspects of future human welfare and well-being. While childhood poverty may lead to poorer outcomes for individuals in terms of physical health, cognitive ability, and educational attainment, it also has deleterious implications for societal well-being. When a high proportion of the child population lives in poverty, as is the case in many countries today, the prospects for overall human development are bleak. Thus, Vandermoortele (Citation2012) has argued that “No [poverty reduction] strategy will be more effective and efficient than to give each child a good start in life”.

Effectively addressing poverty, for both children and adults, requires clear identification of the nature and causes of the problem, as well as an understanding of how it is experienced. The way in which poverty is conceptualised matters, and should be the basis for appropriate measures to inform responses and track progress or lack thereof. Yet, very often, measurement drives definitions and conceptualisations of poverty (Lister Citation2004). The availability of existing data, rather than a justifiable conceptualisation, is often at the core of measurement decisions. Despite increasing debate about the definition of poverty, income-based measures of poverty continue to be highly influential (Main Citation2019), in large part due to the availability of data and comparability over time and place.

In recent decades, multidimensional approaches have become increasingly prominent, challenging income-based measurement. The multidimensional turn has led to innovation in the measurement of both child (e.g. Alkire Citation2019; Gordon et al. Citation2003; Saunders and Brown Citation2020) and adult poverty (e.g. Alkire and Foster Citation2011; Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen Citation2018; Waglé Citation2008; Whelan et al, 2014). Multidimensional approaches to poverty measurement often draw on a capability approach (Alkire and Foster Citation2011). Yet, as Hick (Citation2014, 296) observes there remains a need for greater attention to conceptualising, as well as measuring, poverty. Multi-dimensional approaches broaden understandings of poverty but remain limited, particularly in the extent to which they reveal the ways non-material poverty undermines children’s human rights and capabilities (e.g. Fonta et al. Citation2020; Qi and Wu Citation2015).

This paper seeks to contribute to the growing literature around child-focused conceptualisations of multidimensional poverty (e.g. Noble, Wright, and Cluver Citation2007; Main Citation2019; Saunders and Brown Citation2020; see also Bessell, et al. Citation2020 for a review of the literature in the global South). It begins from the position that to effectively measure and address child poverty it is necessary to develop a justifiable conceptualisation that is grounded in the relevant theory and responds to the experiences and priorities of children living in poverty. It is not morally justifiable to conceptualise, define or measure poverty without taking serious account of the experiences and priorities of those who live it daily.

This article proceeds in three broad sections. The first provides an overview of current debates around poverty and outlines the multidimensional turn that has taken place in recent decades. Here I argue, that despite the value of understanding child poverty as multidimensional, there is a need for a justifiable conceptualisation of multidimensional child poverty that takes account of children’s priorities and experiences. Moreover, current multidimensional approaches tend to neglect non-material poverty. The second section draws on key elements of the capability approach; feminist standpoint theory; and principles of children’s human rights to provide the foundations for conceptualising child poverty. The final section introduces a framework for assessing multidimensional child poverty, comprising three dimensions: material poverty, opportunity poverty, and relational poverty. These three dimensions have been developed from the findings of two research project—one in Australia and in Indonesia—with children aged between seven and thirteen years. Each of these projects adopted a rights-based participatory approach and was informed by feminist standpoint theory. Each casts new light on the dimensions of poverty that are most egregious from a child standpoint.

I argue that material and non-material poverty intersect to shape and deepen children’s experiences of deprivation. It is not possible to evaluate—or respond to—childhood poverty without understanding its non-material dimensions. It is these non-material dimensions that are missing in current measures of child poverty.

2. Conceptualising and Defining Poverty

While poverty is both deeply understood and experienced viscerally by those who live it, among social scientists and policy-makers there is ongoing debate definitions and measurement (Spicker Citation2007; Townsend and Gordon Citation2001; World Bank Citation2017). Definitional clarity is important in determining both how poverty is measured and the responses adopted (see Lister Citation2004). Yet, as Spicker (Citation2007, 3–6) demonstrates, poverty has meanings ranging from the material need to exclusion. Some (see Townsend et al. Citation1997) have argued for the desirability of a “cross-country and … more scientific operational definition of poverty” based on “criteria independent of income”. Townsend et al (Citation1997) argue that international agreement on a basic concept would improve “accepted meanings, measurement and explanation of poverty, paving the way for more effective policies”. More than two decades after Townsend’s call for international agreement on how poverty is defined, a consensus has not been achieved. Sustainable Development Goal 1, to end poverty, adopts several targets, which draw on both income-based and broader definitions of poverty.

A key debate relates to the breadth of definitions: should poverty be understood as a relatively narrow material core, or should it encompass a wider range of deprivations, including non-material, relational, or emotional elements. The concept of absolute or extreme poverty, reflected in the International Poverty Line (currently set at $1.90 per day), is based on a very narrow definition, whereby poverty is the inability to buy the food and non-food items that are essential for subsistence (see Ravallion Citation2010; Jolliffe and Prydz, Citation2016). This approach provides for international comparison and is the basis for assessing progress towards the first target of Sustainable Development Goal 1. However, it not only sets poverty at a very low—barely subsistence—level, it does not provide a sufficient information base for action to end poverty.

Most definitions move beyond absolute poverty to include not only what is essential to sustain life, but also what is necessary for a minimum level of participation in society. In arguing for definitions to include both consumption and participation in society, Nolan and Whelan (Citation1996, 193) have argued for a narrow definition that is able to reveal the absence of financial resources that are the distinctive core of poverty. Lister (Citation2004, 13) has also argued for a narrower definition of poverty, to identify what is unique to the condition of poverty, rather than the result of discrimination or exclusion that arises from other factors (such as racism or gender-based discrimination). While these definitions are clear and justifiable definition, they do not capture the ways in which systematic discrimination and marginalisation create and deepen poverty.

Poverty is most commonly defined as lack of income or low consumption expenditure, and measurement is based on data that are regularly collected and relatively easy to gather. The OECD (Citation2019) defines poverty as “the ratio of the number of people (in a given age group) whose income falls below the poverty line; taken as half the median household income of the total population”. Poverty is assessed according to household income, meaning that while the poverty of given age groups can be calculated, that calculation is premised on the assumption that resources are shared equally across the household. The OECD definition, and that adopted by many countries, is based on a conceptualisation of poverty as relative, drawing on the influential work of Townsend (Citation1979, 31).

Income has dominated poverty measurement and has driven definitions (Spicker Citation2007, 232). Lister highlights the problem of a measurement-driven understandings of poverty, arguing that measurement must be informed by conceptualisation and definition if the causes, patterns and impacts of poverty are to be understood and addressed (see also Oyen Citation1996). The dominance of income has been a particular problem in analysing the causes and understanding the nature and impact of child poverty. This, in turn, has shaped and limited the nature of policy responses which have tended to focus on household income, rather than being child-centred.

Over recent decades, there has been a shift towards a multidimensional conceptualisation of poverty. The multi-dimensional poverty index (MPI), influenced by Sen’s capability approach and building on the Human Development Index, had been instrumental in moving poverty measurement beyond income to assess key areas of human development (Alkire Citation2005; Alkire and Foster Citation2011). Composed of 3 dimensions (education, health and standards of living), and 10 associated indicators, the MPI focuses primarily on the material aspects of poverty and on access to key services. Developed to measure the poverty of adults and largely based on existing data collected at the household level, MPI data have recently been analysed to assess child poverty (Alkire et al. Citation2019).

The adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 reinforced the shift towards multidimensional definitions of poverty, with Goal 1 aiming to end poverty in all its forms everywhere. While the first target of Goal 1 focuses on eradicating income poverty, the second target calls for the end of poverty “in all its dimensions”. Although SDG1 does not define multi-dimensional poverty, but defers to national definitions, it has served to legitimise the place of multi-dimensional poverty on the global policy agenda. Significantly, the second target of SDG1 aims, by 2030, to “reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions”. The explicit reference to children raises the question of whether child poverty has characteristics that are different from adult poverty, thus requiring a specific definition and distinct approach to measurement. The three-dimensional framework of material poverty, opportunity poverty, and relational poverty that is introduced later in this article aims to contribute to developing the definition of multidimensional child poverty, required under SDG 1.2.

2.1. The Shift to Multi-dimensionality and Child Poverty

The shift toward multi-dimensionality has been important in expanding and deepening understanding of child poverty. As Chzhen, Gordon, and Handa (Citation2018, 707) note, money, while necessary, is not sufficient to fulfil all that is needed for children to live free from poverty. While health care or education can be purchased if adequate financial resources are available, good quality services may not be available to some social groups even if incomes increase. Moreover, despite the global prevalence of market economies, some items that are essential for children to flourish may not be subject to markets at all. Chzhen, Gordon, and Handa (Citation2018, 707) identify protection as one such good; so too are the opportunity for play and caring relationships. UNICEF’s (Citation2004, 18) definition of “children in poverty” moves considerably beyond income to “deprivation of the material, spiritual and emotional resources needed to survive, develop and thrive, leaving them unable to enjoy their rights, achieve their full potential or participate as full and equal members of society”. While the narrowness of the World Bank’s definition of extreme poverty can be criticised, the breadth of this UNICEF definition is equally problematic. Defining child poverty as more than lack of household income is essential in addressing the concerns raised by Chzhen, Gordon, and Handa (Citation2018), but the lack of specificity makes it difficult to use this UNICEF definition as a basis for action.

Recent decades have brought important developments in efforts to assess child poverty across multiple dimensions. The Bristol Approach, developed by David Gordon and colleagues (Citation2003), is one of the earliest efforts to develop a measure of child poverty based on internationally agreed definitions. Gordon et al. (Citation2003, 6) drew on the definition agreed at the 1995 World Summit for Social Development, whereby absolute poverty is “a condition characterised by severe deprivation of basic human needs”. Drawing on a subset of human rights enshrined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), Gordon et al measure child poverty in eight dimensions: food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education, information and access to services. For each of these, poverty is assessed across a continuum—from no deprivation to extreme deprivation.

UNICEF has further developed an assessment of child poverty through Multiple Overlapping Deprivation Analysis (MODA). MODA draws on the UNCRC to determine the dimensions assessed, which may vary according to national context (see Hjelm et al. Citation2016). Data analysed through MODA are taken from a range of surveys, including the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS). Some features of MODA result in it being more child-responsive than many other measures. Notably, MODA recognises that poverty is experienced differently for children within the broad age-based category of birth to 18 years; thus, differentiating between age cohorts within the broad category of “child”. Second, MODA recognises that children are rarely able to determine the distribution of resources within a household. Thus, the individual child, rather than the household, is the “unit of analysis”. However, there are shortcomings. First, despite focusing on the individual child, MODA is often reliant on household data to calculate individual poverty. The surveys on which MODA draws, such as MICS and DHS, are developed by adult experts without attention to the dimensions or indicators of poverty that are important to children. Thus, while MODA’s approach is child-responsive, it is arguably not child-centred.

Applications of MODA have produced important insights into the nature of child poverty. Chzhen and Ferrone’s (Citation2017) study in Bosnia and Herzegovina found that children in households defined as “consumption poor”, where income was low, were more likely to be deprived across all dimensions assessed and in a greater number of dimensions at once. However, they found only moderate overlap between consumption poverty and multidimensional deprivation. This is an important finding, leading Chzhen and Ferrone (Citation2017, 1012) to conclude that “child deprivation cannot be eradicated solely by increasing households’ consumption capacity”. MODA is also able to demonstrate where deprivations overlap to deepen poverty, and to highlight multidimensional poverty within specific groups (Chzhen et al. Citation2016).

3. (Re)theorising Child Poverty

In this section of the paper, I draw on principles of children’s human rights, feminist standpoint theory, and key elements of a capability approach to progress how child poverty might be theorised. In doing so, my aim is not purely theoretical. Rather, I aim to contribute to knowledge that results in action. To study child poverty as a theoretical endeavour without the intent to bring positive change would be an immoral exercise (see Lister Citation2004; Piachaud Citation1987). Thus, my aim is to contribute to a deeper understanding that not only contributes to but moves beyond, measuring the extent and depth of child poverty (see Oyen Citation1996), to providing information for child-centred responses.

3.1. Children’s Human Rights and Child Poverty

Both the Bristol Approach and MODA draw on children’s rights, and particularly the UNCRC, for their dimensions. While poverty is not explicitly referred to in the UNCRC, a number of articles are directly relevant, including Article 6 on the right to life, survival and development, Article 24 on the child’s right to the highest attainable standard of health and health care; Article 27 on the right to an adequate standard of living, Article 32 on protection from economic exploitation. Moreover, the right to an adequate standard of living enshrined in Article 11 of the International Covenant of Social, Economic and Cultural Rights must be understood as including children (despite the language of male breadwinner adopted by ICSECR).

This is an important development, for as Alston (Citation2005) observes, there has historically been a disconnect between child poverty and human rights. Townsend (2009, 155) makes the case for understanding poverty as a human rights issue, arguing that the language of rights “ … shifts the focus of debates from the personal failures of the ‘poor’ to the failures to resolve poverty of macro-economic structures and polices of nation states and international bodies … ”. Similarly, Morrow and Pells (Citation2012, 912) argue that child poverty must be understood according to the social, political and economic structures that create and perpetuate it—and fail to address it, and also in terms of the consequences for individual children. Understood in such terms, poverty represents the non-fulfillment of rights, with identifiable lines of accountability, and associated moral claims, to the coercive social institutions (globally, nationally, and locally) that enable violations to occur (see Pogge Citation2008).

Despite their strengths, some critiques have suggested that rights-informed measures of child poverty—such as those discussed earlier—have “selected isolated articles, focusing on provision rights, [while] other rights are not considered” (Morrow and Pells, Citation2012, 912). The segregation of individual rights embodied in specific articles of the UNCRC and the focus on provision rights is problematic from a capability approach, as this neglects children’s ability (or right) to live a life they have reason to value. Further, as Morrow and Pells (Citation2012) argue, human rights, and the UNCRC specifically, have been used by child poverty specialists in ways that “contradict the spirit of human rights conventions, that is, rights as indivisible and interdependent”.

Among the most significant rights guaranteed by the UNCRC are “participation rights”, and particularly Article 12, which entitles children to express their views on matters affecting them, and to have those views taken seriously. Participation rights are essential to the spirit of the UNCRC (Bessell Citation2015), and there are important examples of participatory research with children on poverty (Bessell Citation2009; Main, 2018; Skattebol et al. Citation2012). Yet, measures of child poverty—including those that ostensibly draw on the UNCRC—have remained largely impervious to children’s views. This is not only a contradiction of principles of children’s rights, but a deficiency that becomes clear when considered from a child standpoint.

3.2. Child Poverty from a Child Standpoint

The experience of poverty shapes every aspect of a child’s life. The consequences are “embodied and experienced by children in subtle or acute ways” (Morrow and Pels, 2012, 912). While some consequences may be common to most—or even all—children, others differ between individual children and according to social and cultural context. Feminist standpoint theory has demonstrated how one’s social position shapes the ways in which one experiences and understands the world. In drawing on feminist standpoint theory, I do not make a case for the epistemic privileging of poor children’s views in ways that exclude any other knowledge claims. Rather, I begin from Harding’s (Citation1993, 62) argument that marginalised groups should

[P]rovide the scientific problems and the research agendas—not the solutions—for standpoint theories. Starting off thought from these lives provides fresh and more critical questions about how the social order works than does starting off thought from the unexamined lives of members of dominant groups.

The Deweyan principle that those who bear the consequences of decisions should have a proportionate share in making them has been suggested by some feminist standpoint theorists as valuable (Harding Citation2006; Janack Citation1997). Strikingly, this principle has often been explicitly denied to children—for example Harding (Citation2006, 118), in advocating such an approach, claims that children (and “other very carefully identified groups”) should be excluded from this principle because they “cannot be expected to make decisions or to make them wisely”. Here, the unquestioned biases of some feminist scholars explain why feminist theory has generally failed to address either age-based structures of discrimination and marginalisation or the specific problems that children encounter. The social studies of childhood, with its focus on and demonstration of children’s agency, has much to contribute in challenging such off-hand dismissals of children as able to provide legitimate socially situated knowledge. Yet the social studies of childhood, with some importance exceptions (i.e. Alanen Citation2003; Qvortrup Citation1987) has tended to overemphasise agency at the expense of recognising the ways in which social structures position children (see Spyrou, Rosen, and Cook Citation2018 for discussion).

Combining key elements of feminist standpoint theory with key innovations of the children’s rights and the social studies of childhood is a useful way forward. It is also a starting point for reconceptualising child poverty in ways that are child-centred, and in identifying policy solutions that are child inclusive. A child-standpoint on childhood poverty would enable, indeed demand, research based on three principles. First, genuine engagement with children living in poverty to establish a responsive research agenda and a child-centred methodology. The result should be research that enables children’s socially situated knowledge of poverty, and age-based experiences of it, to be understood in ways that are collaborative rather than extractive. Second, research should be action-oriented, aiming to identify solutions to the problem of child poverty that are deeply informed by children’s unique knowledge. Third, research should move beyond epistemic privilege and epistemic authority, to epistemic inclusiveness. Such an approach recognises the limits of children’s knowledge, but nevertheless respects that knowledge as essential in conceptualising, defining, measuring and responding to child poverty.

3.3. Ethical Individualism and Child Poverty

A feminist-informed child standpoint shifts the focus from the general to the specific, from poverty broadly to poverty as experienced by a specific cohort of people, and from the group to the individual. Yet, it maintains recognition of the structural causes and nature of poverty. In facilitating such transformational thinking, a capability approach has much to offer the conceptualisation of child poverty—and resulting efforts to reduce it. The concept of ethical individualism, which underpins the capability approach, is informative. Ethical individualism “makes a claim about who or what should ultimately count in our evaluative exercises and decisions. It postulates that individuals, and only individuals, are the ultimate units of moral concern” (Robeyns Citation2008). Social structures and institutions are not unimportant, and should be evaluated, but “ethical individualism implies that these structures and institutions will be evaluated in virtue of the causal importance that they have for individuals” well-being” (Robeyns Citation2008).

Children, perhaps more than any other social group, are positioned within social structures and institutions: most notably, the family and the school (see Abebe and Waters, Citation2017; Biggeri and Santi, Citation2012). When children lives are lived (permanently, temporarily or sporadically) outside these institutions they are often viewed with a mix of pity and opprobrium; they are considered to be “out-of-place” (Ennew and Swart-Kruger, Citation2003). When children’s lives are lived within these institutions, they are often subsumed by them. The focus on household income or school enrollment rates, for example, renders invisible the knowledge, experiences and priorities of individual children. Indicators such as household poverty or enrollment rates also shift the evaluative focus to the institution, thus preventing an evaluation of children’s lives and poverty. Main (Citation2019, 32) has demonstrated the problems associated with the dual assumptions that resources are shared equally among all household members and that individuals are “easily assignable to a single, relatively stable household”. Ethical individualism removes the veil of the institution, including the household, enabling us to recognise—and evaluate—the lives of children within. Importantly, applying an evaluative lens of ethical individualism necessarily engenders children’s lives and recognises stages with childhood—essential steps if evaluation is to reflect lived experiences of poverty and enable appropriate responses. Thus, child poverty, and children’s well-being more broadly, can only be assessed from the starting point of the individual.

Clearly, children’s relationships and connections matter—as do the institutions that structure childhood, and both bind and support children. Thus, ontological individualism, which fails to recognise these relationships, connections and structures, should be rejected as unhelpful and unrealistic, and often culturally insensitive. Nor is methodological individualism helpful—indeed, it is only by assessing the justice or injustice, inclusion or exclusion, of societal structures that we can understand the position of individual children.

By adopting a position of ethical individualism, we place the child at the centre of concern and evaluation—and, consequently, responses. In rejecting methodological and ontological individualism, we recognise the importance of uncovering the nature of social structures, and the ways in which they may alleviate or deepen child poverty. Such a position offers a means of progressing child-centred approaches to addressing child poverty.

4. Towards a (New?) Conceptualisation of Child Poverty

Based on the discussion to date, addressing child poverty requires five important steps:

recognising poverty as a violation of children’s human rights, and the importance of the participation rights in addressing this violation;

moving beyond a recognition of children’s right to express their views to (re)conceptualising poverty from a child standpoint;

developing epistemic inclusiveness that allows for children’s knowledge to be illuminated;

adopting ethical individualism that demands a focus on the individual child, while rejecting ontological and methodological individualism; and

assessing the ways social structures and “structures of living together” (Deneulin Citation2008, 111–112) alleviate or deepen child poverty.

In this final section, I aim to demonstrate how the weighty concepts discussed here can be used to inform research with children in order to co-construct child-centred conceptualisation and assessment of poverty. I draw on the findings of two projects, each of which used participatory methods, underpinned by principles of rights-based research, to co-construct knowledge with children and contribute to a child standpoint (see Bessell Citation2013, Citation2015). The first project, “Children, Communities and Social Capital in Australia”, took place in six urban communities in eastern Australia. Four communities were identified as “disadvantaged” on key socio-economic indicators used by the Australia Bureau of Statistics. The children who participated from these communities had personal experience of poverty, and of living in communities identified as disadvantaged and sometimes stigmatised by outsiders.

The second project, “Assessing Child Poverty in Indonesia”, took place in one rural and four urban communities. The rural community included a mix of people experiencing significant levels of poverty and those who were better off. The urban communities were characterised by high levels of poverty (based on rates of consumption expenditure), which visibly translated into a lack of public and private resources and public infrastructure.

In the Australian project, children were aged between 7 and 13 years; in Indonesia between 7 and 15 years. Each project was approved by the Australian National University’s Human Research Ethics Committee, and the project in Indonesia was also approved by the Atma Jaya University (Indonesia) Ethics Review Board.

Each of the projects explicitly aimed to develop a child standpoint, and to take seriously the idea of epistemic inclusiveness. Thus, the approach of each was to create spaces in which children could share their knowledge and experiences of poverty. This involved seeking to co-construct conceptualisations with children, through a range of participatory methods designed to enable them to engage on their own terms and share their ideas in a safe environment. Both projects used the concept of child-centred research workshops, which aim to combine group-based and individual research methods in a supportive environment (see Bessell Citation2013).

4.1. The Multidimensionality of Child Poverty

A significant finding of both research projects is that children’s experience of poverty is multidimensional. A lack of income is essential to poverty, but is not the only dimension. In the Australian project, 11-year old Ellie described the experience of many of the children when she said “We barely have enough money to pay for food in my house.” She went on to explain that she rarely asked her mother for anything that would cost money. As a result, she did not engage in any activities in her community and often missed school excursions and other activities that she worried her mum could not afford. While Ellie’s friends were important to her, she also isolated herself in an effort to avoid the opprobrium she felt would be targeted at her if others knew about her family’s circumstances. Ellie’s school offered support to students unable to afford the excursions and other activities that Ellie often missed. She did not know the support was available and was too embarrassed to seek help. Ellie’s material poverty meant that she missed many opportunities, both in school and beyond. It also impacted her relationships. Within her family, she felt loved and cared for, but also spoke of the stress her mother was under. She also explained that her mother’s work burdens meant there was little time for them to be together as a family. Ellie felt excluded from the community around her and tried to keep her problems to herself. Like many children in this research site, Ellie was acutely aware that people living in other parts of the city considered people in her suburb with disdain. Loneliness and shame characterised Ellie’s life as powerfully as the dire lack of money.

In Indonesia, too, children described poverty as multidimensional. Significantly, some of the boys in urban sites were able to earn money busking and taking on various “odd jobs”. As a result, many did not describe themselves as income poor and were able to buy (usually high sugar, low nutrition) snacks to avoid hunger, and other items. Many gave some of their money to their families, usually mothers. Yet, the context of poverty in which they and their families lived impacted on them in other ways: their schools often had few resources; they were often targeted by police and private security agents; they were aware of the contempt with which they were often viewed by others; they saw daily the inequality between themselves and children living in expensive, modern apartments that towered over their kampung (neighbourhood). Dimensions other than income characterised their poverty.

4.2. Individual Assessment of Individual Experiences

This article has argued for ethical individualism to develop a child-centred conceptualisation of poverty, based on a child standpoint. Ethical individualism is not without contention, particularly in societies such as Indonesia, where collective wellbeing and mutual obligation are valued. Yet, our research with children highlights the importance of beginning with the individual when understanding and assessing poverty. This is most clearly highlighted in the gendered nature of child poverty in Indonesia and the vastly different life experiences of girls and boys.

Our research sought to understand children’s individual—as well as collective—views and experiences of poverty. This proved essential in uncovering the ways gender shapes experiences of poverty from a young age. While boys described their ability to earn money and to be on the streets, girls described a highly domestic life. Girls were responsible for fetching water, cleaning the house, helping with the cooking—all of which, in the context of poverty, are time-consuming and arduous. As one girl explained ‘Here, boys play, girls work.” Both boys and girls experienced poverty as multidimensional, and both experienced violations of their human rights in multiple, interrelated ways—but all such experiences are gendered. Without a focus on the individual as the starting point, the ways in which gender shapes experiences of poverty is lost. Similarly, the ways in which age, ability/disability, ethnicity, geographic location and other social characteristics intersect with gender to shape experiences of poverty are likely to be invisible if the individual is not the unit of moral concern.

5. Dimensions of Child Poverty

By co-constructing a conceptualisation of poverty with children, we sought not only to understand how poverty shapes their lives and undermines their human rights, but to put into practice children’s right to express their views on matters affecting their lives. We drew on feminist standpoint theory as a means of moving beyond “hearing children’s voices” to a position of epistemic inclusiveness whereby children’s unique knowledge genuinely informed the research process and the findings. In adopting a position of ethical individualism, our research moved beyond “children” as an undifferentiated group, to uncovering the ways in which individual children, and specific social groups of children, experience poverty. In doing so, the gendered nature of multidimensional child poverty was illuminated.

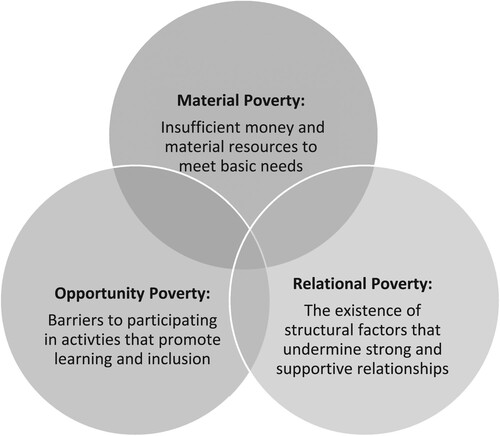

From a child standpoint, drawn from research with children in these two projects, three distinct dimensions of poverty emerged as important: material poverty, opportunity poverty, and relational poverty (see ).

5.1. Material Poverty

Lister (Citation2004) describes the “material core” of poverty, which is bound up with low income and manifests in the lack of a range of material goods that are essential to life, including food, water, shelter. The material core of poverty may extend to the absence of essential services such as health care and education (see also Spicker Citation2007). Here, material poverty can be closely associated with basic needs. Children in each of the research projects spoke of material poverty in detail. In Australia, for example, children were able to detail the cost of rent, food, electricity and other essential goods and services; and to describe the trade-offs that resulted when parents’ incomes were insufficient to pay for these items. Housing insecurity was described by children as a consequence of material poverty, while children described food rationing within the family as a coping strategy in, especially difficult times.

Similarly, in Indonesia, children knew the cost of kerosene and water to the rupiah. While children were aware of household-level coping strategies, in both Australia and Indonesia, children spoke of the strategies they employed themselves to respond to poverty. As discussed, in Indonesia, boys were able to engage in income-generating opportunities. As a result, while all family members experienced material hardship, boys were able to buy goods that other family members (particularly their sisters) could not. In Australia, where children have very few opportunities to earn money, they described limiting requests for school, sporting or other resources because they knew their parents could not afford to provide them. A common strategy described by children was to throw away school permission slips about excursions, sports or other activities that cost additional money. Children explained that they did not want to create additional stress for their parents in already financially distressed circumstances. While children experienced material poverty in ways that are similar to adults and other household members, there are some important distinctions. Moreover, children pro-actively engaged in strategies to cope with their own and their families’ financial/material hardship.

5.2. Opportunity Poverty

While children clearly articulated the nature and consequences of material poverty, their lives were structured and constrained by other dimensions of poverty. A second theme emerging from these research projects is what we describe as “opportunity poverty”. White, Leavy, and Masters (Citation2003, 380) have argued that “[From] a rights perspective, measures are needed that reflect the things that matter most to children. And from a child development perspective, we need to be sure that our approach encompasses the primary factors in attaining positive developmental outcomes.” Opportunity poverty, as the concept emerged from children’s knowledge, encompasses both children’s human rights and development outcomes. Opportunity poverty impacts markedly on children’s capability to live the lives they value in the present and on their future choices and options. Education represents the most immediately apparent opportunity for children—and is valued and prioritised in global and national policy rhetoric because of the promise it offers to individuals and to societies and economies. While other resources, services and activities fall within the category of opportunity poverty (notably play), the focus here will be on education, which is highly illustrative.

In our research, children had complex knowledge of formal schooling, most commonly associated with education. Material poverty shapes both the nature of the schools that children can access and the experience of individual children. Often, schools serving disadvantaged communities receive fewer resources than those serving the advantaged. This was clearly apparent in the way that children in one site in Indonesia described and categorised schools, whereby private schools were described as offering far less than public schools. The private schools open to children living in poverty in Indonesia are far from elite. They are, however, fee for service, often charging fees that are difficult for poor families and children to meet. The quality of education is low, and teachers are often under-trained and have few resources. Public education is generally of a somewhat higher standard, but requires a minimum level of academic attainment. Children explained that meeting the requirements for public school is often difficult, and their only option is to pay comparatively high fees for low-quality private education. Children generally valued education, which they considered to offer the promise of a better future, even as they spoke of poor quality, boredom and harsh discipline. Ironically, education for children living in poverty is both poor quality and expensive. Many boys who described their income-generating activities said that part of their money goes to paying for education. When education is included in measures of poverty, it is generally in terms of enrolment or years completed. From a child standpoint, these indicators reveal very little, either about children’s right to quality education or to the development outcomes produced.

Children in Australia described the ways in which they hoped the school would create future opportunities, but also current experiences of exclusion and marginalisation. In some cases, social exclusion was a collective experience, with children describing the ways in which their school was stigmatised by others. Very often exclusion and marginalisation were individual experiences, resulting from a child’s (and her family’s) material deprivation and low social status. The strategies children adopt to cope with poverty and to protect their families from stress, discussed above, reinforce their experiences of marginalisation as they opt out of a range of activities. Children described employing these strategies with a combination of sadness and pride. Sometimes, their decision was driven by shame and stigma as much as by material poverty. These children were enrolled in, and regularly attended, school—nevertheless, the opportunities offered by school were impoverished.

There exists a vast literature documenting the complexity of children’s experiences of school, and problematising the assumption that education necessarily expands children’s opportunities and choices in both the present and the future (see Abebe and Waters, Citation2017). The findings from the research projects discussed here illuminate children’s knowledge of the ambiguities and tensions inherent in education for children living in poverty. These findings are hardly unique or novel. Yet, they do speak to the importance of conceptualising poverty from a child standpoint, in ways that take seriously well-being achievement and the ability to lead a life one values. An important dimension of child poverty is opportunity poverty, which undermines children’s well-being in the present as well as limiting their future choices. Opportunity poverty cannot be assessed by enrolment rates alone, but must go further to assess and illuminate the value of education, based on children’s unique knowledge of schooling.

5.3. Relational Poverty

The third and final dimension of child poverty emerging from the two research projects is one that was described by children as especially important: relational poverty. That poverty is characterised by shame and stigma is well known (see Walker Citation2014; Chase and Bantebya-Kyomuhendo Citation2014; Lister Citation2004; Spicker Citation2007). The shame and stigma that children experience as a result of poverty are also documented, but less so than for adults.

Children who participated in this research spoke of shame and stigma. The inability to afford school created a deep sense of shame for some children, manifesting physically at times as they slumped and cast their eyes downward—used to being the target of social opprobrium. This contrasted dramatically with children’s sense of pride or excitement when they described positive relationships or their hopes for the future. Shame and stigma shape an individual’s social positionality and sense of self—and shape and constrain social relationships. However, from a child standpoint, relational poverty is more—and more complex—than shame and stigma.

Two aspects of relational poverty are important to draw out. First, relationships with parents/family are fundamentally important to children. Familial and parental relationships were highly valued by children in the different contexts of Australia and Indonesia. Children indicated the ways in which poverty impacts on relationships—resulting in relational poverty. Notably when parents are under severe stress, parent–child relationships are negatively affected. In Australia, children described the ways in which low paying, difficult, and dangerous work impacted on their parents (particularly fathers)—and resulted in their fathers being both exhausted and angry, sometimes retreating from their children or behaving in aggressive (sometimes violent) ways (Bessell, Citation2017b). Children understood their fathers’ behaviour as resulting from the stress of eking out an income and the insecurity and harshness of their work—but they suffered from it. In both Australia and Indonesia, children spoke of their mothers being extremely time poor and exhausted, meaning they had limited time for their children. Children often described time with parents as the resource they valued most, but one that was in very limited supply (Bessell Citation2017a).

Children also described the importance of strong and supportive relationships with others, including adults, in their communities. Children did not explicitly weigh relational poverty against material poverty, but they did describe the ways in which their sense of disadvantage and deprivation could be lessened by strong and supportive intergenerational relationships not only within, but beyond, their families (Bessell Citation2019).

Children also described the ways in which contexts of deprivation interplay with their sense of safety. In Australia, the excessive use of alcohol and drugs (not only within the home, but within their communities) created intense feelings of vulnerability. Strikingly, in contexts of poverty, neither children nor their parents were able to employ effective protective strategies to mitigate this sense of vulnerability and insecurity. However, children described how strong social relationships with both peers and unrelated adults in their communities (as well as with parents) helped them to feel safer and more supported. In Indonesia, children described the ways in which contexts of poverty are structured by violence. While the pressures of material hardship often erupted as violence within the home, children also described violence at school from both peers and teachers, violence within their communities, violence within their workplaces, and violence from security forces. In such contexts, relational poverty is acute—but rarely assessed as an essential dimension of multidimensional child poverty.

6. Towards a Typology of Child Poverty

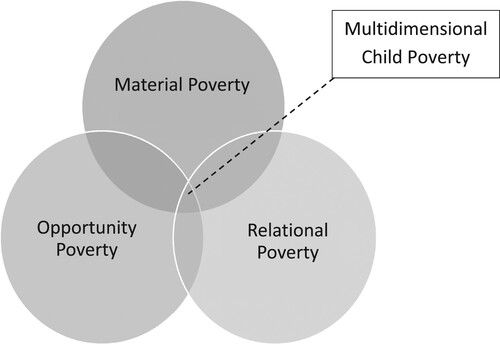

Based on children’s knowledge of poverty emerging from the two research projects discussed above, it is possible to (re)conceptualise child poverty as a multidimensional phenomenon. Material poverty is indeed, as Lister (Citation2004) argues, at the core of poverty. It is not, however, the only fundamentally important aspect of poverty from a child standpoint. Also essential is an assessment of opportunity poverty and relational poverty. It is critical to note that these dimensions of child poverty do not operate in isolation from one another, and understanding the nexus between them is necessary to addressing child poverty. Indeed, deprivation in a single dimension (for example relational poverty) may not equate to poverty, while deprivation in all three dimensions creates multidimensional child poverty (see ).

A three-dimensional typology—material, opportunity, and relational—provides a means of assessing poverty from a child standpoint. It also provides a means of furthering understanding of the elements of poverty that undermine the lives children value and wish to live. This emerging typology is based on rights-based participatory research with children, designed to understand poverty from a child standpoint and to co-construct knowledge, in two different contexts: Australia and Indonesia. It cannot be claimed to be universally applicable. Yet, given the strength of the themes emerging from the research, the three-dimensional typology provides the beginnings of a child-centred conceptualisation and tool for assessing child poverty that progresses SDG1.2. In proposing this typology, I am cognisant of Sen’s disinclination to provide a definitive list of basic functionings or capabilities because different groups in particular contexts will value different sets (Sen Citation2005, 157–160). Sen argues against “one pre-determined canonical list of capabilities, chosen by theorists without any general social discussion or public reasoning” (Sen Citation2005, 158). Yet, without agreed capabilities—or in this case, without agreed dimensions of child poverty—both understanding and action are constrained. While lists chosen by theorists are subject to criticism, lists (or dimensions) determined on the basis of participatory, rights-based research are arguably both just and justifiable. As Nussbaum (Citation2000) argues, for a capability approach to have traction in ways that influence policies and laws, a degree of the specification is necessary. In proposing this three-dimensional typology, I aim to further discussion—and hopefully action—on child poverty, but without demanding a level of detail that is over-specified.

7. Concluding Comments

The three-dimensional typology mapped here provides a practical framework, grounded in a child standpoint, while leaving scope for indicators for each dimension to be developed on the basis of further, context-specific deliberation with children. In proposing such deliberation, however, it is important to note that children are very often systematically excluded from such processes. Indicators for each dimension of child poverty—material, opportunity and relational—can only be justified if they genuinely emerge from a child standpoint, and are indicators that children have reason to value. Within this process, the emphasis must remain on individual children, in keeping with the principle of ethical individualism. As demonstrated through the research presented here, and through a robust and growing body of literature, children are holders of knowledge and are capable to articulating that knowledge if supportive, facilitating contexts are provided. This body of literature directly challenges the idea of epistemic authority, but the role of expert knowledge should not be discarded entirely. In arguing for children’s knowledge to be the basis of assessing and responding to child poverty, it is not necessary to fall to epistemic privilege. Rather, the principle of epistemic inclusiveness provides a means by which to conceptualise and measure poverty in ways that acknowledge children’s experiences, knowledge, and priorities. The aim, ultimately, must be to then move from a deeper understanding of child poverty to policies and services that are genuinely child-centred.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Jan Mason, Tahira Jabeen, Hannah McInness, and Yu Wei Neo for their contribution to the research with children in Australia and to Angie Bexley and Clara Siagian for their contribution to the research with children in Indonesia. Deepest gratitude goes to the children who participated in each of the research projects. All mistakes are author’s. The author thanks the two anonymous reviewers for excellent, extremely helpful comments on the earlier version.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sharon Bessell

Sharon Bessell is a professor of Public Policy at the Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University, where she is Director of the Poverty and Inequality Research Centre and Director of the Children’s Policy Centre. Her research revolves around issues of (in)equality, social justice and human rights, with a focus on the gendered and generational dimensions of poverty and social policy for children.

References

- Abebe, T., and J. Waters. 2017. “Laboring and Learning Volume 10.” In (Editor-in-Chief) Geographies of Children and Young People, edited by T. Skelton. Singapore: Springer: 1–548.

- Alanen, L. 2003. “Childhoods: The Generational Ordering of Social Relations.” In Childhood in Generational Perspective, edited by B. Mayall and H. Zeiher. London: University of London, Institute of Education: 27–45.

- Alkire, S. 2005. “Why the Capability Approach?” Journal of Human Development 6 (1): 115–135.

- Alkire, S. 2019. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index: Illuminating Inequalities. New York: UNDP and OPHI.

- Alkire, S., and J. Foster. 2011. “Understandings and Misunderstandings of Multidimensional Poverty Measurement.” The Journal of Economic Inequality 9: 289–314.

- Alkire, S, R Ul Haq, and A Alim. 2019. The state of multidimensional child poverty in South Asia: A contextual and gendered view. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Alston, P. 2005. “Ships Passing in the Night: The Current State of the Human Rights and Development Debate Seen Through the Lens of the Millennium Development Goals.” Human Rights Quarterly 27 (3): 755–829.

- Bantebya-Kyomuhendo, C. 2014. Poverty and Shame: Global Experiences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bessell, S. 2009. “Indonesian Children’s Views and Experiences of Work and Poverty.” Social Policy and Society 8 (4): 527–540.

- Bessell, S. 2013. “Child-centred Research Workshops: A Model for Participatory, Rights-based Engagement with Children.” Developing Practice 37: 10-20.

- Bessell, S. 2015. “Rights-based Research with Children: Principles and Practice.” In Methodological Approaches and Methods in Practice, Volume 2, in Skelton, T. (Editor-in-Chief) Geographies of Children and Young People, edited by Ruth Evans and Louise Holt. Singapore: Springer: 1-15.

- Bessell, S. 2017a. “The Capability Approach and a Child Standpoint.” In Capability Promoting Policies Enhancing Individual and Social Development, edited by Hans Uwe Otto, Melanie Walker, and Holger Ziegler. Bristol: Policy Press: 201–218.

- Bessell, S. 2017b. “The Role of Intergenerational Relationships in Children's Experiences of Community.” Children and Society 31 (4): 263–275.

- Bessell, S. 2019. “Money Matters … but so do People: Children's Views and Experiences of Living in a ‘Disadvantaged’ Community.” Children and Youth Services Review 97: 59–66.

- Bessell, S, C Siagian, and A Bexley. 2020. “Towards child-inclusive concepts of childhood poverty: The contribution and potential of research with children.” Children and Youth Services Review 116: 105–118.

- Biggeri, M., and M. Santi. 2012. “The Missing Dimensions of Children's Well-being and Well-becoming in Education Systems: Capabilities and Philosophy for Children.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 13 (3): 373–395.

- Chzhen, Y., C. de Neubourg, I. Plavgo, and M. de Milliano. 2016. “Child Poverty in the European Union: The Multiple Overlapping Deprivation Analysis Approach (EU-MODA).” Child Indicators Research 9: 335–356.

- Chzhen, Y., and L. Ferrone. 2017. “Multidimensional Child Deprivation and Poverty Measurement: Case Study of Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Social Indicators Research 131: 999–1014.

- Chzhen, Y., D. Gordon, and S. Handa. 2018. “Measuring Multidimensional Child Poverty in the Era of the Sustainable Development Goals.” Child Indicators Research 11: 707–709.

- Deneulin, S. 2008. “Beyond Individual Freedom and Agency: Structures of Living Together in Sen’s Capability Approach to Development.” In The Capability Approach: Concepts, Measures and Applications, edited by Sabina Alkire, Flavio Flavio Comim, and Mozaffar Qizilbash, 105–124. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ennew, J., and J. Swart-Kruger. 2003. “Introduction: Homes, Places and Spaces in the Construction of Street Children and Street Youth.” Children, Youth and Environments 13 (1): 81–104.

- Espinoza-Delgado, J., and S. Klasen. 2018. “Gender and Multidimensional Poverty in Nicaragua: An Individual Based Approach.” World Development 110: 466–491.

- Fonta, C. L., T. B. Yameogo, H. Tinto, T. van Huysen, H. M. Natama, A. Compaore, and W. M. Fonta. 2020. “Decomposing Multidimensional Child Poverty and its Drivers in the Mouhoun Region of Burkina Faso, West Africa.” BMC Public Health 20: 149: 1–17.

- Gordon, D., S. Nandy, C. Pantazis, S. Pemberton, and P. Townsend. 2003. Child Poverty in the Developing World. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Harding, S. 1993. “Rethinking Standpoint Epistemology: What Is ‘Strong Objectivity’?” In Feminist Epistemologies, edited by Linda Alcoff and Elizabeth Potter. New York, NY: Routledge: 49–82.

- Harding, S. 2006. “The Political Unconscious of Western Science.” In Science and Social Inequality: Feminist and Postcolonial Issues. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press: 113-132.

- Hick, R. 2014. “Poverty as Capability Deprivation: Conceptualising and Measuring Poverty in Contemporary Europe.” European Journal of Sociology 55 (3): 295–323.

- Hjelm, L., L. Ferrone, S. Handa, and Y. Chzhen. 2016. Comparing Approaches to the Measurement of Multidimensional Child Poverty, Innocenti Working Paper 2016-29. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research.

- Janack, M. 1997. “Standpoint Epistemology Without the ‘Standpoint’? An Examination of Epistemic Privilege and Epistemic Authority.” Hypatia 12 (2): 125–139.

- Jolliffe, D., and E. B Prydz. 2016. “Estimating International Poverty Lines from Comparable National Thresholds.” Journal of Economic Inequality 14 (2): 185–198.

- Lister, R. 2004. Poverty. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Main, G. 2019. “Child Poverty and Subjective Well-being: The Impact of Children’s Perceptions of Fairness and Involvement in Intra-household Sharing.” Children and Youth Services Review 97: 49–58.

- Morrow, V., and K. Pells. 2012. “Integrating Children’s Human Rights and Child Poverty Debates: Examples from Young Lives in Ethiopia and India.” Sociology 46: 906–920.

- Noble, M., G. Wright, and L. Cluver. 2007. “Conceptualising, Defining and Measuring Child Poverty in South Africa: An Argument for a Multidimensional Approach.” In Monitoring Child Well-being: A South African Rights-based Approach, edited by Andrew Dawes, Rachel Bray, and Amelia van der Merwe. Cape Town: HSRC Press: 53–71.

- Nolan, B., and C. T. Whelan. 1996. “Measuring Poverty Using Income and Deprivation Indicators: Alternative Approaches.” Journal of European Social Policy 6 (3): 225–240

- Nussbaum, M. 2000. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OECD. 2019. Poverty rate (indicator), August 17. doi:10.1787/0fe1315d-en.

- Oyen, E. 1996. “Poverty Research Rethought.” In Poverty: A Global Review: Handbook on International Poverty Research, edited by Else Oyen, S. M. Miller, and Syed Abdus Samad. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press: 4–17.

- Piachaud, D. 1987. “Problems in the Definition and Measurement of Poverty.” Journal of Social Policy 16 (2): 147–164.

- Pogge, T. 2008. World Poverty and Human Rights: Cosmopolitan Responsibilities and Reforms. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

- Qi, D., and Y. Wu. 2015. “A Multidimensional Child Poverty Index in China.” Children and Youth Services Review 57: 159–170.

- Qvortrup, J. 1987. Childhood as a Social Phenomenon: Introduction to a Series of National Reports. Vienna: European Centre.

- Ravallion, M. 2010. “Poverty Lines across the World”, Policy Research Working Paper 5284, World Bank. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1597057.

- Robeyns, I. 2008. “Sen’s Capability Approach and Feminist Concerns.” In The Capability Approach: Concepts, Measures, Applications, edited by Sabina Alkire, Flavio Comim, and Mozaffar Qizilbash. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 82–104.

- Saunders, P., and J. E. Brown. 2020. “Child Poverty, Deprivation and Well-Being: Evidence for Australia.” Child Indicators Research 13: 1–18.

- Sen, A. 2005. “Human Rights and Capabilities.” Journal of Human Development 6 (2): 151–166.

- Skattebol, J., P. Saunders, G. Redmond, M. Bedford, and B. Cass. 2012. Making a Difference: Building on Young People’s Experiences of Adversity. Sydney: Social Policy Research Center. www.australianchildwellbeing.com.au.

- Spicker, P. 2007. The Idea of Poverty. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Spyrou, S., R. Rosen, and D. Cook. 2018. Reimagining Childhood Studies. London: Bloomsbury.

- Townsend, P. 1979. Poverty in the United Kingdom. London: Allen Lane and Penguin Books.

- Townsend, P., and D. Gordon. 2001. Breadline Europe: The Measurement of Poverty. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Townsend, P, D Gordon, J Bradshaw, and B Gosschalk. 1997. Absolute and Overall Poverty in Britain: What the Population Themselves Say: Bristol Poverty Line Survey. Bristol: Bristol University Statistics Monitoring Unit.

- UNICEF. 2004. State of the World’s Children 2005 – Children Under Threat. New York: UNICEF.

- Vandermoortele, J. 2012. “Equity Begins with Children.” In Global Child Poverty and Well-being: Measurement, Concepts, Policy and Action, edited by Alberto Minujin and Shailen Nandy. Bristol: The Policy Press: 39–53.

- Waglé, U. R. 2008. “Multidimensional Poverty: An Alternative Measurement Approach for the United States?” Social Science Research 37 (2): 559–580.

- Walker, R. 2014. The Shame of Poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- White, H., J. Leavy, and A. Masters. 2003. “Comparative Perspectives on Child Poverty: A Review of Poverty Measures.” Journal of Human Development 4 (3): 279–396.

- World Bank. 2016. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2016: Taking on Inequality. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/25078/9781464809583.pdf.

- World Bank. 2017. Monitoring Global Poverty: Report of the Commission on Global Poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25141.

- World Bank. 2020. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34496/9781464816024.pdf.