ABSTRACT

Drawing from the capabilities approach (Sen Citation1999; Nussbaum Citation2000) and reflecting on Fricker’s (Citation2007) epistemic (in)justice, this paper seeks to explain how a participatory oral history project enabled youth researchers in Palestine to increase their capabilities to participate in political and social life in their communities by fostering their attachment to the land and by increasing understanding of their cultural heritage. Due to the occupation, Palestinian youth researchers have been exposed to epistemic inequalities. They have been systematically prevented from exercising their political functionings; they cannot voice their ideas on freedom, heritage and land. Findings show that through participatory research, the youth researchers took an active role in their communities to cultivate their epistemic abilities to be the narrators of their own stories and to create public advocacy. Whilst acknowledging the intersectional power dynamics and oppression that govern their lives, the paper explores the possibility of participatory research in redressing epistemic injustices caused by structural inequalities and in disrupting colonial relations of domination. The research indicates that even in politically fragile contexts, participatory research can promote critical reflection, challenge the social imaginaries stigmatising the youth, and provide opportunities to develop political capabilities for social and public advocacy.

Introduction

This research draws on a participatory video study conducted between 2017 and 2019 with more than 30 youth researchers between the ages of 18–28 years old in the South Hebron Hills (SHH), Area C in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt). The youth researchers, who were young people from local villages and who participated in research training as part of the project, documented intangible cultural heritage (ICH) by conducting over 100 h of intergenerational oral history interviews. Due to the political and geographical fragmentation imposed by the Israeli occupation, the communities in SHH have limited opportunities to practice their political capabilities, defined by Nussbaum (Citation2000) and Cin (Citation2017) as the ability to engage in politics, express ideas freely, or the ability to be free from state repression. Drawing from the capabilities approach (Sen Citation1999; Nussbaum Citation2000), and reflecting on Fricker’s (Citation2007) epistemic (in)justice, which refers to a particular group of people being systematically neglected, discredited and silenced, we examine how a participatory oral history video project “On Our Land”Footnote1 enabled the youth researchers in SHH to increase their capabilities to participate in political and social life in their communities, which allowed them to stay connected to their land (Darweish and Sulin Citation2021), increasing the resilience of their communities and fostering cohesive relations between youth. We further conceptualise Fricker’s (Citation2007) epistemic (in)justice as a political capability (Cin and Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm Citation2020) while critically exploring how the participatory research created an epistemically inclusive process that led to the expansion of youth researchers’ valued capabilities and functionings (Sen Citation1999).

Most of the people living in Area C are doubly marginalised due to the occupation and due to the limitations of the Palestinian Authority’s ability to provide investments or infrastructure to the area. The creation of Israeli closed military zones, demolition of houses, forcible evictions, and the imposition of severe restrictions of movement have threatened people’s livelihoods which are mostly based on pastoral and agricultural activities (B’tselem Citation2019). It is not easy for youth researchers in SHH to exercise their political functioning due to the lack of a viable, safe, and democratic environment that could enable them to voice their values and ideas. We argue that participatory research, accompanied by collecting oral history stories, helps redress epistemic injustice caused by structural inequalities; raises youth researchers’ voices and challenges the prejudices and unequal power relations created by the Israeli occupation. Based on evaluation interviews, field notes and reports from the project, the paper explains how the youth researchers have taken a more active role in their communities, continuing to record oral histories. We argue that a participatory research strategy enabled the youth researchers to develop key skills (communication, filming and photographing, networking, presenting, conducting interviews) and gain knowledge (about their history, communities and injustices) that are essential epistemic resources to practice their political capabilities. This process also enabled their access to communities and residents’ histories to create epistemic spaces and take a more active role in bringing change to their communities going beyond just protecting their cultural heritage, therefore, contributing to greater epistemic justice. In the next section, we discuss the importance of cultural heritage for nation-building and how and why developing political capabilities are central to the advocacy for one’s national identity and belonging to a political community in highly contested contexts.

The Importance of Cultural Heritage for Nation-building

Heritage includes both tangible (such as material artefacts) and intangible (such as social practices) heritage. It can be a legacy of the past that exists in the current society that people wish to preserve to benefit the present and pass on to future generations (Muzaini Citation2013). It is crucial to question not only what we remember but also how and in what form in terms of memory and heritage (Said Citation2000). Constructing memories and their representation touches upon nationalism, identity, power, and authority (Said Citation2000). Despite the international protocols throughout history to protect tangible and intangible heritage during wars,Footnote2 Palestinian heritage struggles to survive and exist under the Israel regime.

The residents of the SHH area have been facing cultural, social, and economic changes, due to the occupation, that have forcibly displaced them to areas closer to Area A and B, which are under Palestinian control (Soliman Citation2019). The Israeli authorities have built settlements in the area, which have restricted the movement of the SHH communities’ residents as this has narrowed down the area where shepherds used to graze their sheep and plough the land with crops for their livestock. The Israeli authorities created closed military zones in the SHH area to evict the residents during military training and to prevent any construction or infrastructure or future developments in the SHH (B’tselem Citation2013).

People in South Hebron Hills live in 33 hamlets and villages, primarily engaged with pastoral and agricultural activities and are tribe-based. SHH communities own a rich social capital and cultural heritage, however the ongoing Israeli occupation has severely impacted the transmission of Bedouin and non-Bedouin cultural heritage between generations and communities in SHH. Due to the displacement caused by the occupation the people in SHH are prevented from engaging with their traditional cultural heritage practices, such as raising livestock, farming the land, and sharing their cultural heritage with younger generations. Abandoning these traditional practices further strengthens the Israeli government’s attempts to claim the land and diminish the rights of Palestinians to stay on the land. However, as the findings of this paper demonstrate, cultural heritage protection can support the resistance in the communities in SHH and grow their sense of ownership and identity to their land and heritage.

Through the oral history interviews, youth researchers collected the intangible cultural heritage of SHH. UNESCO Convention 2003 on “Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage” recognises ICH as practices, representations, knowledge, expressions, and skills that communities and individuals recognise as part of their cultural heritage (UNESCO Citation2003). Oral history is based on the recording and interpretation of historical information, based on the personal experiences and stories of the speaker. It is particularly used to capture stories from more marginalised groups or smaller communities whose stories might not be otherwise represented in the more formal histories of states (University of Leicester Citationn.d). As in the case of Palestine, oral history is particularly useful to capture evidence if there is generally a lack of either written or visual documentation. Storytelling, the Arab tradition called hakawati, was used immediately in the years after Nakba of 1948Footnote3 to defend the erasure of Palestinian culture and memory. Oral history in Palestine has had a prominent role since then to provide a counter narrative in the context of the Israeli occupation (Al Shabaka Citation2016). Collecting oral history stories, which constitutes intangible cultural heritage, shows the importance of ICH as a “tool that instils in communities a feeling of identity and continuity, promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity” (Nebot-Gómez de Salazar, Morales-Soler, and Rosa Jiménez Citation2020, 84).

Intangible cultural heritage is valuable to the SHH communities as it is a means to preserve their distinct cultural identity during the occupation, and a valuable resource due to the wealth of knowledge these communities hold (i.e. agricultural practices and knowledge of medicinal plants). Heritage provides the communities with a sense of ownership and togetherness in the midst of the Israeli occupation and it also enables the construction of collective and cultural memory, a form of expression and a means for a cohesive group identity (Hoelscher and Alderman Citation2004). However, the formation of collective memory is often linked to power and questions of domination. Memory is “inherently instrumental” as groups and individuals form their past not only for their own sake but also to promote different aims and agendas (Hoelscher and Alderman Citation2004, 349). Collective memory is not a passive concept, but it is continuously modified, edited, and imbued with political meaning (Said Citation2000a). As Said writes (Citation2000b), one of the most significant struggles for Palestinians has been the right to remember their presence and the right to process and reclaim their collective historical reality since the conflict began to overtake their land and scattered people from their communities. This is an experience for all people that have been colonised and whose past and present have been dominated by outside powers that took over their land and rewrote the history of people to make the colonisers or occupiers appear as the true landowners (Said Citation2000).

Given this political role of heritage and collective memory in building a national identity and sense of belonging, protecting and practicing one’s own heritage and culture, along with transferring it to next generations, contributes to the well-being of the community. It is fundamental to the capability of people to live and to be what they value. In conflict situations, being excluded from conservation of your own heritage damages the shared values and interests of communities and causes an epistemic injustice that could be hard to redress. The political capability of being able to record one’s own heritage through oral history and intergenerational knowledge transfer becomes more salient to foster tolerance and recognition among the communities in conflict situations. This political capability requires a peaceful environment and safe epistemic spaces from colonial intervention where cultural heritage is not manipulated and invented, because “geography can be manipulated, invented, characterised quite apart from a site’s merely physical reality” (Said Citation2000, 180). We argue that it is this very basic epistemic injustice of not having access to one’s own heritage, not being able to develop a feeling of place and belonging or being misrepresented, with which we are primarily concerned. The political capabilities we refer to speak to this idea of having the freedom and opportunities of advocating, sharing, and living with and through the shared values of a community.

Using Participatory Video to Protect Palestinian Cultural Heritage and Enhance Political Capabilities

The “On Our Land” research project was an intergenerational study, where youth researchers between the ages of 18–28 years old interviewed elderly people from their communities in SHH and interacted closely with them. The research project consisted of three components: (1) cultural heritage protection, (2) training and capacity-building, and (3) advocacy and education. The project aimed to further enable the youth researchers’ capabilities by using PV methods to preserve and protect their lived cultural heritage and its relationship to the land. This combination of PV and oral history enabled the youth researchers to aim to create social change through the combination of the scholarly approach of oral history and the activist enterprise of PV (Armitage and Gluck Citation1998). We recognise how the core elements of participatory video of reflection on the process and collaboration followed by action, means that PV can be also situated as a tool within the methodological framework of Participatory Action Research (PAR) (Plush Citation2013; Walsh Citation2016). Plush (Citation2013), following similar elements to that of Gaventa and Cornwall’s (Citation2008) Participatory Action Research framework, offers a conceptual framework of three elements (awareness and knowledge; capacity for action and; people-centred advocacy) for conducting PV research. This framework uses PV as a means to raise awareness in order to build knowledge as power, emphasising how this can help to change inequalities. As argued in this paper, to increase their political capabilities the youth researchers need to increase their knowledge about their own cultural heritage to face epistemic (in)justice. Plush (Citation2013) argues that this conceptualisation of PAR builds on the strengths of local communities by using PV to ensure the knowledge which is generated is done in a participatory manner. We claim the PV process enabled the youth researchers and SHH communities to create an archival record of their own historical narratives, which further contributed to their knowledge regarding their rights to their own cultural heritage and land. As one youth researcher said: “I think all young people from all areas should be motivated to document their areas, prove their right on this land and face the occupation … ”.Footnote4

Designing the PV Process

The participatory oral history research project was initially designed by the project team from a UK university. The research has been conducted in different phases due to external funding cycles and the design of the latter phases of the project was developed in cooperation with the youth researchers, local coordinator and community members from SHH. The project included establishing a local advisory group consisting of the mayors, activists, and heads of the communities in the SHH, which aimed to foster unity and increase local participation, and to also advance local ownership to the project and protection of the cultural heritage of the area.

The selection and recruitment of the youth researchers for the project was based on a transparent process through identifying youth members from the different villages and hamlets in the SHH, with the mayors and key local activists advising. In cooperation with the local councils, information sheets about the project were distributed to the different villages, targeting the young members of the communities. More than 60 youth applied and filled the applications. Members of the project team from the UK, the local project coordinator and the local advisory committee, consisting of key stakeholders from the communities, interviewed the applicants and selected 30 youth researchers based on criteria, such as their availability to attend training, willingness and interest to learn about cultural heritage, and knowledge about the area. These criteria had been decided with the oral history trainer, the local project coordinator and the advisory committee. One of the core aims of the recruitment was to ensure not only a gender balance but also that there were youth researchers represented from all villages and communities from the area.

Training and Conducting Oral History Interviews as Part of the PV Process

The youth researchers from the 33 village and hamlet communities from the area participated in training and workshops on oral history methodology, interviewing techniques, videography, advocacy, and presentation skills. The group consisted of both male and female youth researchers in equal numbers. The youth researchers conducted interviews on topics such as agriculture, resistance and occupation, popular songs, (living in) caves, weddings, traditional tools, and celebrations. The meetings with elderly people in the SHH communities during the initial mapping of each village and hamlet, as well as the youth researchers’ own experiences, enabled the youth researcher as a group to decide which on which themes of cultural heritage they wanted to focus. The project coordinators assisted the youth researchers to build their skills to map the villages, decide on the initial themes, and how to conduct the interviews.

Due to the occupation, this heritage is in danger of being lost as most of the area’s cultural heritage is passed down orally rather than in paper documentation (Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Citation1999). The Israeli occupation has repeatedly targeted the SHH area causing damage to their heritage, which made the connection between tangible and intangible heritage difficult to document. For example, the land of the Palestinian village of Susya in SHH, whose residents lived in caves and made a living from shepherding, was declared an archaeological site by the Israeli Civil Administration in 1986. The land was confiscated and the residents evicted from their homes and the caves, along with property, were destroyed (B’tselem Citation2018). Israel designated most of the SHH as a firing zone which put the residents’ existence at risk, including their cultural heritage. In addition, the Israeli government inhibited any documentation of the cultural heritage of Palestinians with the aim that the new generation will forget, and the Israelis will write their own history (Ibrahim Citation2000). However, while the rich history of the area has not been documented, it has lived on in the elderly generations and through the stories passed from one generation to another.

By utilising a participatory research process, combined with an intergenerational aspect, the PV process allowed the younger generations to learn about their own heritage from primary sources, that is, from the older community members who have lived through it and for the older generations to pass on the knowledge they had acquired (Darweish and Sulin Citation2021). It was a vital part of the project to record these oral histories and traditional practices that would otherwise be lost when older generations pass away. The youth researchers became the experts on this knowledge which they created; as one reflected: “Now I know how important this is for my country, for South Hebron and how important it is to protect it. I am from the youth in this area, so I have to work to save my cultural heritage”.Footnote5

The videos captured oral histories and traditional practices in all the different villages in SHH, ensuring that also the uniqueness of the different places were recorded. The youth researchers conducted interviews in pairs, depending on the interests they had shared to the different themes of cultural heritage which were decided earlier. Throughout the project it was ensured that there was a gender balance amongst the people being interviewed so that both men and women were able to share their stories. Some of the women interviewed shared how this was the first time they were able to tell stories of their heritage, further contributing to the notion of how using participatory video can help to overcome epistemic injustices by creating a space to listen to people and communities whose stories are marginalised.

After conducting the interviews and producing the “On Our Land” film, the youth researchers attended training sessions before a UK speaking tour to understand how to develop public presentation skills, showcase the research they had conducted and how to make a convincing argument (Darweish and Sulin Citation2021). Two UK speaking toursFootnote6 were organised in 2019 and early 2020 in which five of the youth researchers participated. During the tour the youth researchers showcased the film and presented research findings to a range of audiences from university students and academics to members of public and policy makers in the UK.Footnote7

The youth researchers have since then also participated in different events showing the film both in Palestine and abroad via virtual screenings, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote8

Power Asymmetries Within the Research Team

As part of a PV process, reflection and discussion on power asymmetries within the project team members are critical, especially so when the project funding and lead were located in the UK, and project partners, including smaller, marginalised communities and young people, in Palestine. It has been argued by Walsh (Citation2016) that in order for PV to be a truly emancipatory tool, “a reflexive approach to how power and agency work within participatory video is essential if the method is going to effect change and not merely manage social conflict” (406). Participation within PAR is in principle a group activity, but as McTaggart (Citation1997) writes, it can become problematic when the group consists of different people with different power, influence and status. Our research project involved different partners and stakeholders, which meant that consideration of power relations and asymmetries was needed at several levels. The formation of a local advisory group enabled more balanced power relations within the research team by bringing the voices and opinions of local stakeholders to the design and execution of the process. The local project coordinator is also an insider and one of the authors of this article. He has been involved in the communities of SHH for more than 12 years and has built long, strong and transparent relations with the residents of the SHH communities, which has facilitated the relationship between the communities and the team at the UK university. The local project coordinator has also been acting as a facilitator to address issues regards to power asymmetries. Still, even though the process of conducting the research aimed to be participatory, this was often hindered by the competing external demands such, reporting and budget deadlines by the institution and funder.

As discussed earlier in the paper, the initial research project was designed by a team from a UK university. The team members had developed trust over the years with the communities in SHH (Darweish and Suln Citation2021). For the consecutive funding applications, the youth researchers and local advisory group were involved in the development of the funding application from the early stages of writing the proposal, which helped to facilitate a more equitable partnership. By collecting the oral history stories, the youth had become the experts and owners of this knowledge, which meant they were able to share their thoughts on what the priority areas should be for the next stages of the research. This became especially relevant with regard to the outreach and output activities of the project. Being involved in the planning of the research from beginning to end offered the youth researchers access to socially constructed knowledge, which could help address topics that are often not spoken about (Mitchell and De Lange Citation2011). However, limitations were imposed on this process by tight timelines, priorities and demands by the different funding calls, which meant that it was not always possible to include every stakeholder in the process.

Epistemic Justice and Political Capability: Voices of the Palestinian Youth

We draw from the capabilities approach (Sen Citation1999; Nussbaum Citation2000) and reflect on Fricker’s (Citation2007) epistemic injustice to address the testimonial and hermeneutical injustices that the Palestinian youth researchers face. Testimonial injustice refers to giving a group of people less credibility due to prejudices such as race, class, and gender (Fricker Citation2007, 108). The knowledge produced by the marginalised group and their opinions, views, voices would become obsolete or illegal, and as a result, this group would face systemic injustices. Hermeneutical injustice, on the other hand, refers to structural injustice. This happens when a society cannot recognise or comprehend an individual/ a group’s experience because they belong to a social group that has been prejudicially marginalised (Fricker Citation2007). The Palestinian youth in this research are located at the intersection of these two forms of injustice of being discredited and being trapped in structural relations of colonialism and dominance. They cannot get their voices heard or their identities recognised, and they are the victims of misrepresentation by the outside world. Most importantly, they are denied spaces to be vocal about their everyday experiences of colonialism and political violence, to learn about their cultures, traditions, and values and carry these on to future generations. The hermeneutical inequalities in their lives arise from social and political inequality from living under oppression by Israel which prevents them from exercising their voices. There is little collective understanding on the importance of constructing a collective history, and Palestinian efforts to rewrite their history have had disastrous effects on the quest for Palestinian self-determination (Said Citation2000). The youth also experience testimonial injustice as Israel controls the narrative as the only actor on the ground and the only one who decides the future of the area. Under these different layers of epistemic injustice, unequal power relations and dominating structures that produce colonial authority, the youth in this research highly valued the participatory, reflective and dialogical nature of participatory photography. Being able to record their cultural heritage and the oral life histories of the elder generations were identified as an act of epistemic resistance and an opportunity for enhancing their political capabilities.

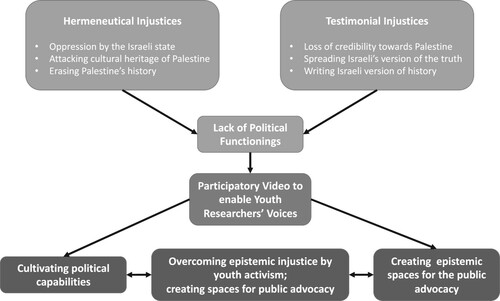

Our understanding of political capability expands the conceptualisation of Cin (Citation2017) who defines it as “one’s freedom to express political ideas and to engage in politics; to protest and to be free from state repression” (44) to add Bohman’s (Citation1996) idea of political poverty to argue for the necessity of “political equality of access, skills, resources, and space to advance capacities for public functioning and knowledge production” (Cin and Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm Citation2020, 172–173) for a fully functioning political freedom. In this research, we showcase how participatory video first enabled the youth to develop key political functionings and then investigate the process of how these were converted into capabilities which enabled the youth to build epistemic relations and resistance to redress the epistemic injustices they have experienced (see ).

Community engagement with cultural heritage through a participatory video process had mutually reinforcing ties between the various dimensions (functionings, conversion factors and opportunities) that comprise political capabilities. First, we assert that the cultural heritage recorded and disseminated through participatory video production in this research has contributed to advancing the capacities, and creating spaces essential for political capabilities of Palestinian youth by enabling them develop key functionings and by opening epistemic platforms both nationally (within their communities) and internationally (the screenings in the UK) to develop a political voice. In particular, the participatory, artistic and cultural means of the research process created spaces for new learning opportunities for their political functionings to flourish, such as developing self-esteem, building collective agency, narrating (communicating) their stories, networking, and also developing narrative imagination and developing good reasoning. These functionings are key to one’s well-being and ability to craft a political voice. This political voice also has the redistributive effect of raising wider political awareness about the stories of Palestinian youth. Secondly, the deliberative and collective nature of the participatory video deepened youth’s knowledge about their culture and challenged political discourses that silence Palestinian youth, made unseen heritage visible, and thus unlocked structures for political capabilities. The national and transnational spaces created through the project for disseminating their stories collectively and the functionings developed across the participatory process were all part of the process of building political capability through the participatory approach.

While critically exploring how the participatory research created an epistemically inclusive process that led to the expansion of youth researchers’ valued capabilities and functionings (Sen Citation1999), we also note that youth researchers manifested the epistemic inequalities created by the hermeneutical and testimonial injustices that misrepresent their communities. This approach allowed them to exercise their freedom of political participation, created a representative process, empowered participants to speak out against perceived epistemic silencing, but also reshaped their political and social network by forming alliances with more powerful actors outside their societies (e.g. UK based researchers, NGOs, universities, Palestinian and international governmental actors and stakeholders) (Mkwananzi, Cin, and Marovah Citation2021). Therefore, in the next section, we elaborate on how PV built political functioning,s and then we showcase how participatory research enabled the youth to use their political capabilities for social advocacy and to be epistemic contributors to their communities.

Cultivation of Political Capabilities to Face Epistemic Injustices by Using Participatory Video

The youth researchers acquired several functionings during the project that contributed to epistemic justice. They developed their political functionings by improving their self-esteem in developing the voice to narrate their stories; building their critical reasoning; and also building a collective agency to share their stories with a wider network. For example, for many of the youth researchers, especially for the women, this was the first time they had used professional cameras, presented to external audience and participated in formal advocacy training to learn to voice their opinions and knowledge about their heritage.

The process of participatory video strengthened the political capabilities of the youth researchers through generating their own knowledge of their cultural heritage, as opposed to the knowledge that has been imposed on them. This allowed them to develop a deeper understanding of their heritage, place, and space (). The PV approach found common ground for both generations to talk about cultural heritage, one generation equipped with the knowledge about their past lives, and the other equipped with the technology and skills to document these stories. The PV interviews were designed for a purpose that enabled the youth to learn and the older generation to share their stories – this knowledge exchange was a powerful experience for both the interviewee and the interviewer. Through the PV interviews, youth researchers discovered new issues about the lives of the older generation, thus developing the youth functionings and enabling them to see the future through the lenses of the past inspired by their grandparents and elderly community members’ stories. The youth researchers were able to challenge existing testimonial injustices by making the people of SHH’s voices and experiences visible. The participatory video approach combined with recording of oral histories enabled youth researchers to debate about their cultural heritage and their history in the area through the stories told to them by elderly people. This has made the youth researcher value their cultural heritage and act to protect it:

The project opened my eyes to new understanding of the importance of cultural heritage and not to allow our history to be erased … The documentation is a very effective and powerful way to show and present our history and heritage.Footnote9

Many things have changed, developed, or been forgotten but when we go back in time and learn about how those before us lived -like how ploughing the land was difficult for them but yet how much they enjoyed it, this is really important. When we can bring a tangible item from our past forward, it proves that we owned this land, and it brings us closer to our land. We need to protect this land that has been inherited to us.Footnote10

This is our culture, Palestine is for us, the occupation might steal our culture and they might tell us tomorrow that this village does not belong to you, and it belongs to us, that this is our land.Footnote11

Another youth researcher highlighted how they have understood how important it is to document your history to show that you have the right to live on this land:

All the communities have the right to document their heritage. My comments are for the youth from those communities: “Care about being a researcher for your community. You must document your ancestors and their lives here in this village before the occupation. You have the right, and you must prove that the occupation does not have the right to be here – they want to displace you. Defend your rights about being here by giving evidence that documents your heritage”.Footnote12

When we can bring a tangible item from our past forward, it proves that we owned this land, and it brings us closer to our land. We need to protect this land that has been inherited to us, because this is the life of our parents and grandparents.Footnote13

This section was built on the knowledge of the youth researchers through PV that led to political and social awareness. This increased the youth’s capabilities to see injustices through wider lenses that empowered them to take an active role in their communities. By cultivating their political capabilities to advocate the area of the SHH to Palestinian international audiences, the youth researchers tried to overcome the testimonial injustices they all have been exposed to. The next section presents the active involvement of the youth researchers in bringing justice, protecting their heritage, advocating for their rights and fostering public advocacy to discredit epistemic inequalities.

Creating Epistemic Spaces for the Public Advocacy

The oral histories expressed through the videos advanced public advocacy on two levels: First, by developing political capabilities, the participants learnt to express political voice and formed spaces to collectively raise their aspirations in public. Second, the participants gained functionings to disseminate their research to wider audiences, and this is how they addressed the epistemic injustice that they had to face.

Generating their own knowledge on the South Hebron Hill’s heritage, increased the youth researcher’s awareness of their right to stay on the land and further contributed to political functionings. Developing the political capabilities of the youth researchers enables them to deny the Israeli claim that this land was not populated. The mayor of the SHH used some of the data from the project in court against the claim that some areas of Jenba hamlet did not have anyone living there. Through the collected stories, the youth researchers were able to demonstrate that Palestinian people living there cannot go unrecognised and to convey the message that the land was not empty. Heritage formed the cornerstone for their rights, strengthened solidarity with the SHH residents and, most importantly, fought against hermeneutical injustice.

The participatory video approach enabled the youth to own the knowledge, become the experts of this history and the materials that they need in their debate not only about what happened in the past but also how life was before the occupation (Darweish and Sulin Citation2021). This approach has enabled them to develop the confidence and voice functionings through participation, presenting their videos, and by being included in public deliberation and discussion (Cin and Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm Citation2020).

Realising and developing their political capabilities enabled the youth researchers to become politically active in their communities by taking a more active role in their villages, continuing to document their history, sharing, and debating this knowledge with a wider audience. Due to the SHH being part of Area C, one could argue that the youth researchers need to be more politically assertive of their rights and demands than the youth living in for example in Ramallah, which is under the Palestinian Authority’s jurisdiction.

The youth researchers attended seminars and events in universities and museums in the UK, and a photography exhibition in London sharing their photos and work, as well as showing the film produced as part of the research to different national and international audiences. The number of international events the youth have been able to attend virtually to present their research has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic as Zoom events have become part of everyday reality. This has meant the youth researcher have been able to connect with a broad range of audiences around the world, without the hindering travel restrictions Palestinian youth from Area C usually have to deal with. The continuation of organising activities, especially advocacy by the youth researchers, reflects the development and advocacy of their political capabilities.

The Palestinian people have suffered from a lack of political participation, which is a crucial part of being socially excluded. The SHH communities have been under threat of displacement, therefore the history of the area is important to challenge Israeli policies and protect people’s existence in the SHH. Through building the capabilities of the youth they have produced detailed data about their cultural heritage in the SHH, that is the first of its kind. This has advanced the debate among locals about protecting their cultural heritage as they discovered the importance of their cultural heritage. In other words, their belonging and attachment to their land and communities has increased.

The youth researchers’ involvement in the project has changed their opinions about protecting their own cultural heritage; as one of the youth researchers said:

I was not very interested in culture. I never really thought about researching my heritage, documenting, or presenting it in an exhibition. Our community never really talked about heritage. Now that has changed. Now as soon as I hear someone reference to the past, I think about interviewing them and learning more […]Footnote14

Developing the political capabilities of the youth researchers enabled them to create public spaces to address different people. Firstly, to the residents of the SHH who have reflected on valuing their cultural heritage and protecting it as part of their collective identity through the research. In such case the collection of oral histories has fostered the resilience of the residents to challenge occupation policies, which aim to forcibly displace them. The second audience is the Israeli settlers and soldiers. Youth researchers gained the ability to debate with the settlers and the army. Through the project, the youth researchers developed their debate when they included cultural heritage as a tool to defend their rights against the occupying power. This was also reflected on with the international audience when youth researchers denied the Israeli claims through cultural heritage, as happened when they took part in a variety of UK seminars.

Concluding Thoughts

This paper has argued how a participatory video approach created an epistemically inclusive research process where youth researchers, through knowledge production, fostered epistemic abilities, increased awareness, and became more active politically in their communities. This led to the expansion of their valued capabilities and functionings. Lack of hermeneutical and testimonial justice among youth researchers affected their capability to function with regard to their political freedoms. By creating their own knowledge through the collection of oral history stories and hence understanding of the economic, political, cultural, and social heritage of the area, allowed them to develop a more critical understanding of their right to stay on their land and to resist the Israeli occupation. Understanding one’s own cultural heritage can further strengthen one’s identity, sense of belonging and claim to the land. As Said (Citation2000b) notes: “It is what one remembers of the past and how one remembers it that determine how one sees the future” (29). PV in this project helped youth researchers to produce knowledge and become experts of this knowledge. The youth researchers gained credibility which had an impact on expanding testimonial and hermeneutical justices. This provides a good example of a bottom-up approach on bringing change at an individual and community level and increasing the political capabilities of the youth researchers for them to have the opportunity to participate in political and social life on a broader level.

We have contributed to the literature on epistemic justice and political capabilities by presenting how researchers use PV to develop their voices and critical reasoning to participate in discussions concerning their land. The youth researchers’ lived experiences have transformed into knowledge and created opportunities for them to challenge the epistemic injustices they have been facing. Though the occupation continues to generate testimonial injustices every day, by documenting the cultural heritage of the SHH, the youth researchers not only increased their awareness but also acted collectively and resisted testimonial marginalisation. Testimonial injustices can become systematic and if persistent can lead to hermeneutical injustice (Fricker, Citation2016; Walker and Boni Citation2020). The interviews, photos and recordings collected by the youth researchers can now be used to evidence the Palestinian people’s right to live and stay on the land in South Hebron Hills, for example, in court and to advocate against the occupation. This strengthens their argument and improves their testimonial credibility. We also contribute to the literature on heritage by arguing how protecting histories and passing histories on to generations are important tools to address and overcome epistemic inequalities imposed by dominant actors.

Although this paper has discussed how the participatory video process combined with oral history interviews increased the youth researchers’ capabilities, the process is not without its own issues. Participatory video has been shown in this case as a good method to bring change amongst the youth in South Hebron Hills communities. However, as Walsh (Citation2016) argues, PV always takes the individual as a site of change rather than larger societal structures. As in the case of the Israeli occupation, the larger structural injustices cannot be solved just by using PV as a method (Walsh Citation2016). Yet, despite the challenges the youth researchers have faced as part of the project, they have become active ambassadors for their villages, engaging with communities nationally and locally sharing their knowledge and history of the area. By recording these oral histories, these Palestinians from the South Hebron Hills are creating and transmitting knowledge: redressing epistemic inequalities in this way is a powerful way to counter act the Israeli narrative of a land without a people for a people without a land.

Acknowledgements

Mahmoud Soliman and Laura Sulin were members of the On Our Land project team at Coventry University. The team was led by Marwan Darweish and included Patricia Sellick, Aurélie Broeckerhoff and Elly Harrowell. The project was conducted in partnership with the Palestinian Popular Struggle Coordination Committee This research is a collaborative effort between the youth researchers and local leaders in South Hebron Hills, oPt, and the On Our Land teams in the UK and Palestine. The On Our Land project was funded by the British Council Cultural Protection Fund (2017-2019) in partnership with the Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport. The fund aims to protect cultural heritage which is at risk due to conflict in the Middle East and North Africa. For more information, please visit the project website www.onourland.coventry.ac.uk.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mahmoud Soliman

Mahmoud Soliman is a Palestinian nonviolent activist and academic. He completed his PhD in Peace and Conflict Resolution Studies from Coventry University in April 2019. His thesis focus was on Social Movements mobilisation. He is one of the cofounders of a popular nonviolent resistance network called the Popular Struggle Coordination Committee (PSCC). He is a visiting fellow at Coventry University. Also, he is a Sociology department faculty affiliate and a member of the Resistance Studies Initiative (RSI), at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He has been the local coordinator of the On Our Land project in the South Hebron Hills in occupied Palestine.

Laura Sulin

Laura Sulin is a researcher at the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University. Her research interests lie in the field of gender, peace and conflict research. Currently Laura is part of the research team working on British Council funded research project “On Our Land” (2017-2022), an intergenerational oral history project working with young Palestinian researchers in the occupied Palestinian territory. Laura’s PhD focused on the implementation of the United Nation’s Agenda on “Women, Peace & Security” in South Africa and the occupied Palestinian territory.

Ecem Karlıdağ-Dennis

Ecem Karlıdağ-Dennis holds a PhD from the University of Nottingham, School of Education. She works as a Senior Researcher at the University of Northampton, at the Institute for Social Innovation and Impact. She is experienced in working on educational projects involving underrepresented young people. Her research interests include global education policy, social justice and gender.

Notes

1 The research project was applied through a UK university in partnership with a Palestinian NGO and local stakeholders of the SHH communities.

2 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and Geneva second protocol of 1977.

3 A war began on 14 May 1948 when the State of Israel was born. Palestinians refer to this day as “the Nakba”. By 1949, the creation of Israel had resulted in the displacement of 750,000 people and a refugee problem (Soliman Citation2019)

4 Interview with male youth researcher, September 2018.

5 Interview with a female youth researcher July 2019.

6 The aim of the UK speaking tours was to provide opportunities for the youth researchers to present their research and cultural heritage to an international audience and to create networking opportunities.

7 On Our Land film link: https://vimeo.com/396678574.

8 The videos collected showcasing the culture heritage and oral histories of the area are in the process of being currently archived. A detailed data management plan was constructed to ensure the safeguarding of the data.

9 Interview with youth researcher, August 2018.

10 Interview with male youth researcher, September 2018.

11 Interview with female youth researcher, September 2018.

12 Interview with male youth researcher, September 2018.

13 Interview with male youth researcher, September 2018.

14 Interview with female youth researcher, September 2018.

15 This is when the research project officially concluded with the end of funding.

16 The three projects were the ideas of the youth researchers and are aiming to increase Palestinians and international awareness about the SHH area geography, politically and historically through cultural heritage paths, guest houses and a community museum.

References

- Al Shabaka. 2016. “Palestinian Oral History as a Tool to Defend Against Displacement”, September 15, 2016, via https://al-shabaka.org/commentaries/palestinian-oral-history-tool-defend-displacement/, accessed 25th June 2021.

- Armitage, S., and S. Gluck. 1998. “Reflections on Women’s Oral History: An Exchange.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 19 (3): 1–11.

- Bohman, James. 1996. Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: MIT Press.

- B’tselem. 2013. “The South Hebron Hills”. B’T https://www.btselem.org/south_hebron_hills. [December 2021].

- B’Tselem. 2018. “Khirbet Susiya – a Village under Threat of Demolition”. https://www.btselem.org/south_hebron_hills/susiya. [7 December 2021].

- B’Tselem. 2019. Settlements [online]. https://www.btselem.org/settlements [21 April 2021].

- Cin, F. M. 2017. Gender Justice, Education and Equality: Creating Capabilities for Girls’ and Women’s Development. London: Palgrave.

- Cin, F. M., and R. Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm. 2020. “Participatory Video as a Tool for Cultivating Political and Feminist Capabilities of Women in Turkey.” In Participatory Research, Capabilities and Epistemic Justice, edited by Boni, A. Walker, M. 165–188. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Darweish, M., and L. Sulin. 2021. “Re-connecting with Cultural Heritage: How Participatory Video Enabled Youth in Palestine to Protect Their Cultural Heritage.” In Post-conflict Participatory Arts and Socially Engaged Development, edited by M. Cin and F. Mkwananzi, 96–116. Routledge.

- De Sousa Santos, B. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. London: Paradigm.

- Fricker, M. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fricker, M. 2016. The epistemic dimensions of ignorance. In The epistemic dimensions of ignorance, edited by R. Peels, 160–177. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

- Gaventa, J., and A. Cornwall. 2008. “Power and Knowledge.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research, edited by P. Reason and H. Bradbury, 172–189. London: Sage.

- Hoelscher, S., and D. Alderman. 2004. “Memory and Place: Geographies of Critical Relationship.” Social & Cultural Geography 5, (3): 347–355.

- Ibrahim, B. 2000. The Palestinian Narrative: A Look at the Palestinian Narrative in the 20th Century. Syria: Al Tariq.

- McTaggart, R. 1997. “Participatory Action Research: International Contexts and Consequences.” SUNY Series.

- Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation. 1999. “Endangered Cultural Heritage Sites in The West Bank Governorates.” Ramallah.

- Mitchell, C., and N. De Lange. 2011. “Community-based Participatory Video and Social Action in Rural South Africa.” In The Sage Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by E. Margolis and L. Pauwels, 171 –185. London: Sage.

- Mkwananzi, F., M. Cin, and T. Marovah. 2021. “Participatory Art for Navigating Political Capabilities and Aspirations among Rural Youth in Zimbabwe.” Third World Quarterly 42 (12): 2863–2882.

- Muzaini. 2013. “Heritage Landscapes and Nation-Building in Singapore.” In Changing Landscapes of Singapore, Old Tensions, New Discoveries, edited by E. Lynn-Ee Hoo, C. Yuan Woon, and K. Ramdas, 25–42. Singapore: Nus Press.

- Nebot-Gómez de Salazar, N., E. Morales-Soler, and C. Rosa Jiménez. 2020. “Participatory Methods and Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Neighbourhoods.” Universitas 33: 83–102.

- Nussbaum, M. 2000. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Plush, T. 2013. “Fostering Social Change Through Participatory Video: A Conceptual Framework,” Development Bulletin, no. 75, August 2013.

- Said, E. W. 2000a. “Invention, Memory and Place.” Critical Inquiry, Winter 2000 26 (2): 175–192.

- Said, E. W. 2000b. Reflections on Exile and Other Essays. New York: Harvard University Press.

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Soliman, M. 2019. “Mobilization and Demobilization of the Palestinian Society: Towards Popular Nonviolent Resistance from 2004-2014.” Unpublished PhD, Coventry University, Coventry, UK.

- UNESCO. 2003. “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage”, https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention, accessed 23rd June, 2021.

- University of Leicester. n.d. “What is Oral History”, School of History, accessed via file:///C:/Users/ab6996/Downloads/OH%20Intro.pdf, 23rd June, 2021.

- Walker, M., and A. Boni. 2020. Participatory Research, Capabilities and Epistemic Justice. Cham: Palgrave.

- Walsh, S. 2016. “Critiquing the Politics of Participatory Video and the Dangerous Romance.” Area 48 (4): 405–411.