ABSTRACT

This article considers how useful measurement and indicators are in developing insight into a problem as complex as gender injustice and education. It poses the question about what we ought to evaluate with regard to individuals, institutions, discourses and countries when we make assertions about gender inequality in education and how to address this. The paper provides a way of thinking about gender and education that highlights how inadequate existing measures are. It sets an agenda for future work outlining the AGEE (Accountability for Gender Equality and Education) Framework. This draws on the capability approach and identifies domains where indicators can be deployed. The discussion highlights how multiple sources of information can be used in a well-organised yet adaptable combination, taking account of the complexity of the processes in play, to develop guidance on practice for transformational and sustainable change that can support work on women’s rights and gender equality in education.

Introduction

Girls’ education and gender inequalities associated with education were areas of major policy attention before the COVID-19 pandemic, and remain central to the agendas of governments, multilateral organisations and international NGOs in thinking about agendas to build back better, more equal or to build forward (Save the Children Citation2020; UN Women Citation2021; UNESCO Citation2021, Citation2022a). The concern with climate change, galvanised through discussions at COP26 (the United Nations Climate Change Conference, held in Glasgow in 2021), underlined the urgency and significance of this work (Pankhurst Citation2021; UNESCO Citation2022a). But this area presents many challenges in thinking about indicators for analysis, planning, monitoring, evaluation and learning to improve practice. When we make assertions about gender injustice in education and how to address it, what ought we to evaluate with regard to individuals, institutions, discourses and countries? Given many debates concerning definitions of gender and intersecting inequalities, how can we draw on existing indicators to evaluate initiatives to improve girls’ education, gender equality and attend to concerns with intersectionality, helping to steer improvements in policy and practice?

Many aspects of gender injustice and issues around how we identify, understand, and address gender inequalities in education have become acute due to the profound impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the worsening climate crisis on communities worldwide, especially the poorest or most vulnerable (UNESCO Citation2020, Citation2021, Citation2022a; Okwuosa and Daimond Citation2021; Parkes et al. Citation2020; Equal Measures Citation2022). But data to monitor these processes is uneven, not always comparable across settings, and appears in many disparate kinds of publication. The Equal Measures 2022 report on progress with regard to gender and SDG indicators highlights both the uneven level of change, and the resources needed to document this in more depth (Equal Measures Citation2022). A lack of data is compounded by some clashes on definitions of the problem regarding gender inequalities and education and the nature of the solution (Unterhalter Citation2016, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Monkman Citation2021). Developing policy and practice to support substantive and sustainable gender equality in and through education requires concepts that can be used to review a wide range of relationships between individuals, institutions, networks and discourses, looking at what is distinctive about education systems as well as the ways in which education connects with other areas of human development.

Designing and building an indicator framework for measuring gender equality and education is not a simple or uncontroversial process. Among some who engage with education statistics, there has been an assumption that existing metrics constitute a good enough indication of performance in an education system. Gender parity, which comprises the ratio of girls to boys or women to men in a given aspect of education, such as enrolment, progression, attainment, teacher training, or adult literacy levels is the most commonly used measure. An alternate view, however, is that metrics always construct forms of distancing, distortion and deformation of democratisation. Grek (Citation2020) charts how practices of quantification and standardisation in large scale comparative literacy and numeracy surveys have reshaped the work of international organisations concerned with education, leading them to focus on regulating the management of learning outcomes, rather than more substantive concerns with rights or social justice. This critical view considers metrics particularly damaging when they are used as part of UN-supported global gender policy frameworks (such as the Millennium Development Goals) and present relationships that are unmeasurable or challenging to measure in numeric form (Sen and Mukherjee Citation2014; Merry Citation2016; Grek, Maroy, and Verger Citation2021). Somewhere between the two camps is a body of work that has developed more complex approaches to thinking about gender inequality and equality than gender gaps or gender parity, and which has worked with communities involved with policy and practice to think about indicators of gender inequalities associated with institutions and relationships that produce them (Branisa et al. Citation2014; Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen Citation2018; Bessell Citation2020; Equal Measures Citation2022). To date, however, much of this work has not focussed on education. To better understand gender inequalities in education and assess relevant data for identifying appropriate indicators, a wide range of discussion is important. While many sources of data are needed in describing the relevant inequalities, there are many problems associated with how to organise this and support action for change.

This article aims to develop thinking about indicators and measurement for gender equality in education that shift the focus beyond gender parity. It considers how to deploy data that are currently collected in developing insight into the complex problem of gender injustice and education and how to link this with a process for selecting useful indicators that can help support and sustain change. The article discusses how to build some conceptual architecture, drawing on the capability approach, to navigate through some differences in theory, policy and practice and lay the ground for a course of action through which the selection of indicators contributes to critical reflection on the processes of analysis, strategic planning, monitoring and evaluation. In recognising how inadequate existing metrics and measures for gender equality and education are, the paper suggests an approach to using multiple sources of information in well-organised, holistic yet adaptable combination, taking account of the complexity of processes in play, to develop guidance on processes for transformational and sustainable change.

The first part of this paper provides contextual background and sets out some of the debates around metrics and indicators associated with gender and education, situating these in relation to global policy frameworks. The second part of the paper introduces some conceptual distinctions from the capability approach and presents an analytic framing for indicators of gender equality and education that have been used in developing the AGEE (Accountability for Gender Equality and Education) Framework.Footnote1 The AGEE Framework is then presented in the third part of the paper, where we describe the processes that led to the generation of the Framework, and some of the initiatives that have begun to consider how to use it to select indicators for cross-national comparison, engaging with the gendered effects for education of the climate crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and large scale displacements of people through war. In the final part of the paper, we return to the problem of the multifaceted nature of gender equality in education and pose some critical questions for the AGEE Framework in its next phase.

Assessments of Gender Inequality in Education: Metrics, Systems and the SDG Agenda

Gender parity has been the main metric used to assess levels of gender inequalities in education for nearly three decades.Footnote2 It is used in the indicators for the targets for the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) associated with education – SDG4 – and in national Education Sector Plans (ESPs). Gender parity is also used by UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS), which provides data for the annual Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Reports (e.g. UNESCO Citation2018a, Citation2020), and in assessments of learning outcomes including the Evaluation of Educational Achievement’s framework PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study) or the OECD’s PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment). From a statistician’s perspective, gender parity is an excellent metric because it is conceptually clear and can be applied across education systems, institutions and countries without deploying complex methodologies. Work is required to collect and validate data, but this is done through existing processes, including education management information systems (EMIS), national statistical offices’ household surveys, or examination boards. These routine processes of data collection do not require large investments in data manipulation and can be fully transparent. Gender parity, as an indicator of gender equality in participation, progression and achievement in education, has thus been enormously useful for planners working at district and school levels as well as for governments developing national education sector plans.

Nonetheless, gender parity has inherent weaknesses. While it is methodologically straightforward, it is also conceptually problematic because it locates the question of gender as primarily a question of social roles mapped onto biology. Critical readings of gender inequalities abound when gender is understood as a concept that is historically mutable evoking consideration of power, representation, forms of structure and agency, performance, and reflection on or rejection of binary categories (Cranny-Francis et al. Citation2017; Khoja-Moolji Citation2021). The multifaceted nature of gender is discussed in work on intersectionality (Crenshaw Citation1989; Yuval-Davis Citation2006; Hill Collins and Bilge Citation2016), which highlights how gender inequalities intersect with other inequalities relating to, for example, class, race, ethnicity, location, disability, the terms in which these are cast and the institutions which maintain them (Unterhalter, Robinson, and Ron Balsera Citation2020). Critical reflection on how to understand gender and education is evident in writings on African feminism (Decker and Baderoon Citation2018; Kwachou Citation2020), decoloniality (Frost Citation2011; Bhambra Citation2014), new materialism (Harding Citation2017) and queer theory (Butler Citation1990; Martino and Cumming-Potvin Citation2018; McCann and Monaghan Citation2020). Further inadequacies of gender parity are linked with difficulties with interpreting gender in contexts where definitions of sex and gender have been highly polarised and conflicted (Cooper Citation2019; Żuk and Żuk Citation2020; Biroli and Caminotti Citation2020). Yet four comprehensive literature reviews of interventions for girls’ education and gender equality (Unterhalter et al. Citation2014; Sperling and Winthrop Citation2015; Pereznieto, Magee, and Fyles Citation2017; Unterhalter, Robinson, and Ron Balsera Citation2020) highlight how this critical scholarship regarding definitions of gender, has, for some decades, been largely unreferenced by the gender and education policy community. UNICEF (Citation2022) has recently argued for gender transformatory work in education, but not discussed critical gender scholarship in any depth. The 2020 GEM Gender Report engages with work around inclusion and intersectionality, and adopts an understanding of gender that moves beyond the male-female binary (UNESCO Citation2020, 6). The report argues that inclusive education systems, supported by policies that address issues of intersectionality as well as trained and well-informed actors, can support gender equality in and through education. Assessing these processes, however, requires measurement and evaluation that go beyond gender parity.

The popularity and usefulness of gender parity as a concept and a metric for policymakers has been associated with a widespread, but narrow, policy and programme focus on getting girls into school, assuming a host of beneficial social, health and economic outcomes will follow (Unterhalter Citation2016; Unterhalter, Howell, and Parkes Citation2019). Girls’ education can be used in ways that are concerned to isolate and depoliticise one thread of social policy, rather than addressing a range of interconnected inequalities (Unterhalter Citation2016, Citation2017a; Mjaaland Citation2021). The emphasis on girls’ education has sometimes provoked the response that boys out of school or failing to progress is also a challenge. This masks and undermines the complexities of gender inequalities suggesting gender equality is a zero-sum game in which two groups that suffer discrimination need to be lined up against each other in a struggle for resources or esteem (Unterhalter Citation2018; Longlands Citation2020). A problem with the limited focus on girls’ education is that girls and women may be present in equal proportions or even outnumber boys and men in schools or other education institutions, examination passes or those completing education cycles. Yet these girls may have few opportunities in relation to reproductive rights, employment, social security and political participation.

A focus on gender parity cannot indicate whether girls at school or women who work in education may be learning how to tolerate gender inequalities rather than gaining confidence and opportunities to challenge and change them; nor can it indicate whether boys or men have been enabled to do the same. As many scholars have noted, gender injustice in education takes many forms relating to public and private relationships (Stromquist Citation1995; Salo Citation2001; Fennell and Arnot Citation2009; Maslak Citation2008; UNESCO Citation2015a; Parkes Citation2015; Stromquist, Klees, and Lin Citation2017; DeJaeghere Citation2017, Citation2020; Unterhalter and North Citation2017; Mjaaland Citation2021). Gender parity measures, however, portray individuals as detached from relations in schools, households, communities, polities, economies or discursive framings. The widespread existence and everyday forms of school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV), for example, have been acknowledged in recent years (UNICEF Citation2014; Parkes Citation2015), and a number of studies find an association between violence and poor educational outcomes (Guedes et al. Citation2016; Fry et al. Citation2018). As many scholars have noted, institutions may generate or perpetuate gender inequalities associated with education through laws, policies, financing arrangements, norms, curricular frameworks, learning materials, pedagogic approaches, leadership structures or work practices (Fennell and Arnot Citation2009; Maslak Citation2008. Unterhalter and North Citation2017; Mjaaland Citation2021).

A host of critics, ranging from the present back to the early days of UNDP’s Gender and Development Index (GDI), have noted that gender parity provides insufficient information to understand what substantive gender equality in education would entail (Bardhan and Klasen Citation1999; Tisdell, Roy, and Ghose Citation2001; Unterhalter Citation2005, Citation2015; Gaye et al. Citation2010; Plantenga et al. Citation2009; UNESCO Citation2015a, Citation2018). Moreover, some perverse effects associated with the use of gender parity metrics, such as increasing access for girls and boys to low-quality schooling, further illustrate that while gender parity may be a necessary condition for gender justice in education and enable some indication of progress toward gender equality, it is not sufficient (Unterhalter Citation2014).

Measures have been developed for cross-country comparison of complex inequalities related to education systems (see ). However, with some recent exceptions, these yield little information about either the forms of institution that bear on education or the opportunities and outcomes for particularly located individuals. Some more complex measures of some of the institutional and contextual forms of gender inequalities have been developed outside education (see ) but these have been criticised for offering inadequate insight into forms of inequality associated with education and for inadequate treatment of individual experience (Unterhalter Citation2015; Unterhalter Citation2017b).Footnote3 A few individual/household level metrics of gender inequality (e.g. the Individual Deprivation Measure (IDM)Footnote4 and the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI)) allow for more nuanced considerations and indicate ways in which individual engagements with education could be analysed more complexly than simply assessing learning outcomes through gender parity. Yet existing instruments for examining gender inequalities in education do not draw on these approaches. Current complex measures of the multifaceted nature of gender inequalities point to many sites where gender injustice and how it impacts on individuals needs to be examined, notably institutions and norms, as documented by the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) and European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), and households, as tracked through indicators assembled for the IDM and WEAI. Each of the measures shown in allows for comparisons across countries. While some of these measures require data from specially commissioned surveys, others draw on existing sources. Nonetheless, all use data on school enrolment or completion, and do not further consider the nature of education institutions and systems and their gender effects on individuals or the discourses that frame them. There is thus a problem in understanding how individuals, institutions, and national formations of gender and other intersectional inequalities connect with the processes of education. This raises issues about how one might be able to identify paths toward enhanced support for social and economic rights, equality and equity taking on board the many facets of education.

Table 1. Metrics and measurement initiatives relating to education.

Table 2. Metrics outside education.

Gender parity as the key metric used in assessing forms of gender inequality and equality in education is thus problematic on three counts. It is based on a limited assumption of what gender is and debates regarding how to define gender. When used in analyses of education systems it presents an inadequate connection of education systems with other social relations and institutional formations that form gender inequalities and injustices. When used as denoting a measurement across countries, it suggests gender can be equated with something constant, like purchasing power parity, and does not acknowledge the complex ways in which gender is differently defined and negotiated in education settings by distinctive histories for individuals, institutions, communities and countries.

Opportunities to address these weaknesses associated with gender parity are presented by both the SDG framework and the centrality of gender equality in the Education 2030 Agenda agreed by the global education community in 2015. These have been rearticulated in the policy documents of major institutions such as UNESCO (Citation2018c), the United Nations Girls Education Initiative (UNGEI) (Citation2018), and the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) (Citation2016). The demands of thinking about the climate crisis and monitoring some of the gender effects of COVID-19 have been noted by the Gender Flagship of the Global Education Coalition formed in 2020 (UNESCO Citation2021, Citation2022a).

SDG4 expresses a vision to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (United Nations Citation2015). This is a shift from the narrow focus on universal primary education in the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) framework. The targets for SDG4 comprise expanding opportunities across all phases of education – pre-primary, primary, secondary, vocational, higher and adult education. These targets not only broaden the scope of education but also broaden the focus on enrolment and progression in earlier global frameworks to encompass outcomes in literacy, numeracy and wider learning, including global citizenship, sustainability and gender equality. Education is also noted in other SDG targets, including SDG3 on good health and wellbeing, SDG5 on gender equality and women’s empowerment, and SDG8 on decent work. A wide range of participants contributed to the formulation of the SDGs, with education and women’s rights campaigners a key constituency (Gabizon Citation2016; Unterhalter Citation2019). Since 2015, a technical committee – the UN Inter-Agency and Expert Group (IAEG) – have taken the decisions about metrics, although a process of annual refinement is ongoing to 2025 (United Nations Citation2020a). Twelve global education indicators agreed by the IAEG are obligatory for all countries to collect data and report on progress towards SDG4. Thirty-one optional thematic indicators, developed by the UNESCO Technical Cooperation Group (TCG), are a more comprehensive set of internationally comparable indicators that countries may also use to report on progress. The IAEG classified the SDG global indicators as Tier 1, 2 or 3, depending on whether they have conceptual rigour, cross-country comparable data or still require methodology to be developed. As of November 2020, there are no longer any Tier 3 indicators, although newly updated indicators are provisional until a comprehensive data review has been completed (United Nations Citation2020b).

One critique of this process of global indicator development and validation is that technical committees, like the IAEG, stand outside debate around rights, justice or equalities, and instead focus on the task of comparing trends across countries. King (Citation2017), Unterhalter (Citation2019) and Wulff (Citation2020) have looked at ways in which substantive concepts of quality and equality become lost in the transition of SDG4 from targets to indicators. King (Citation2017) has termed this a loss associated with translation between levels. Unterhalter (Citation2019) has discussed some of the reasons for this, showing how prevailing discourses and institutional arrangements gave authority to numbers associated with counting inputs or outputs, rather than indicators portraying inclusion, equity and quality opportunities. Indicators that might help develop better understanding of forms of institutions and the relationship of individuals to education systems were initially grouped together in the “difficult to measure” Tier 3 category, but from November 2020 are now all in Tier 2.Footnote5 However, the indicators for the majority of targets associated with gender equality still draw on a gender parity approach. Just two targets – 4.7 and 4a – have scope for a deeper engagement with gender equality that allows for thinking through the relationships of institutions and individuals, although the current selected indicators still fall short of capturing these complexities and engaging with tensions between global, national and local contexts (Unterhalter Citation2019; Durrani and Halai Citation2020).

Some conceptual connection is therefore needed to help develop indicators for gender equality and education that move beyond gender parity. The need to understand the multi-facetedness of connections between individuals, institutions, contexts and countries is underscored in work on climate change in East Africa (Rao et al. Citation2019a, Citation2019b), which highlights how droughts, floods and other effects of climate change, not yet sufficiently recognised in education planning, are playing out in relation to girls being taken out of school. The differential gender effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have been noted by a number of studies, which draw out the intensification of women’s care responsibilities both in supporting education of children at home and as part of teaching or care work for the most vulnerable (e.g. de Paz et al. Citation2020; UN Women Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2022a). The pandemic has dramatically revealed how crises interconnect and global processes are experienced in local settings. This, in turn, highlights how the challenges of measurement associated with gender inequality in education are both conceptual and operational, and require particular kinds of collaborations (UNESCO Citation2021, Citation2022a).

The problems with gender parity as a metric of injustice in education systems are thus partly conceptual, partly operational and partly political. In our view, the capability approach provides a useful and flexible framework for addressing some of the conceptual and practical problems with the “thinness” of gender parity through its recognition of the effects of social, environmental, institutional and cultural structures on an individual’s agency, choices and wellbeing. In the next section we consider some of the analytic perspectives the capability approach provides for addressing the problem of understanding gender and intersecting inequalities in education, and for evaluating the policy and practice that seeks to address this.

Measurement, Gender Justice and the Capability Approach

The capability approach builds on work in philosophy, economics and many applied disciplines, and has been a particularly generative interdisciplinary engagement with forms of individual, environmental and institutional inequalities and how these can be analysed in making evaluations about what people are able to do and the lives they are able to lead (Sen Citation1999, Citation2011; Comim, Qizilbash, and Alkire Citation2008; Crocker Citation2009; Nussbaum Citation2011; Robeyns Citation2017; Prah Ruger Citation2018; Chiappero Martinetti, Osmani, and Qizilbash Citation2021). Scholarly work on measuring gender justice that draws on the capability approach discusses how deploying the concept of capabilities has the potential to construct an evaluative frame that both depicts and contributes to change (Robeyns Citation2003; Peppin Vaughan Citation2007; Loots and Walker Citation2016; Wilson-Strydom and Okkolin Citation2016; Robeyns Citation2017; DeJaeghere Citation2020). Some of the scholarship on the capability approach, gender and education has generated nuanced accounts of individual and interpersonal inequalitiesFootnote6, and the approach has also informed metrics utilised at a country level, such as the Human Development Index (HDI), the Gender Inequality Index (GII), the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), SIGI and the WEAI. While this body of work is connected through its use of the capability approach, some of the difficulties we noted in the previous section with measuring inequalities have not been overcome. Documenting the complex relationships between the individual, the institutional and the national and taking account of intersectional inequalities remains a challenge in many of the indicator frameworks. The MPI, for example, analyses data on poverty within households, but cannot make comments on individual male and female members. SIGI deals with norms and institutions and considers some issues of intersecting inequalities but not yet in relation to education as a specific domain (Ferrant et al. Citation2020). Nevertheless, drawing on all the resources of the capability approach together provides a line of travel to attempt to address these difficulties, and, more specifically, to expose some of the problems of developing a framework and measures to evaluate progress on gender equality in education.

Robeyns (Citation2017, 24) provides key insights in her synthesising overview of the capability approach, pointing out that drawing on the capability approach enables evaluation of: (i) individual levels of achieved wellbeing, and freedoms to achieve wellbeing; (ii) evaluation and assessment of social arrangements and institutions; and (iii) design of policies and practices for change. The conceptual elements Robeyns identifies as core elements of the capability approach can be deployed when creating an indicator framework for education that incorporates information at the social and institutional level to give a clearer picture of inequalities in educational capabilities. These conceptual underpinnings can therefore be interlinked to help develop a theoretically engaged framework for gender equality in education that goes beyond gender parity.

Robeyns (Citation2017) emphasises that a key element of any analysis that draws on the capability approach entails evaluation that distinguishes between functionings and capabilities. Functionings are what an individual achieves (for example, a state of being healthy or educated), or something a person does (such as reading a book or passing an examination). Capabilities, meanwhile, are the real opportunities to achieve functionings. One of our critiques of gender parity being used as a sole measure of gender in education is that it captures elements of functionings (such as enrolments, completion rates, or exam achievement) but omits insight into the conditions that underpin these functionings, which may vary for different groups. Deploying the concepts of functionings and capabilities to education enables us to ask questions such as: are there gender differences in the capability to participate in learning? If girls are not achieving educational functionings, is it by choice, or through lack of capability (due to either resources or conversion factors, or both) – that is, is there a gender imbalance in capability to participate in education? Moreover, as this perspective entails a focus on the intrinsic importance of freedoms in education, it prompts concern with whether there is a gender difference in freedoms in educational experiences.

We thus consider it important to have a framework that takes into account functionings, which would describe the achievements in education of children who need compulsory education, as well as some measure of capabilities, that is, the diverse forms of freedom to achieve functionings. A metric of gender equality in education would thus need to both evaluate functionings or outcomes (such as literacy, numeracy, passing an examination, or achieving work, health or wellbeing), and highlight the importance of looking at dimensions of freedoms and opportunities that underlie these (such as opportunities to choose within the curriculum and options to participate in different forms of learning, without incurring prejudice). These freedoms and opportunities can be constituted, constrained or expanded by institutions, norms or the relationships and ideas which frame national education systems. Taking account of both functionings and capabilities in an indicator framework gives a richer informational base and also allows for some assessment of the locatedness of an individual in both institutional and non-institutional relationships. The context is thus not viewed as an arbitrary set of cross-national socio-economic markers but is closely related to the link or dislocation between functionings and capabilities in particular settings.

To date, existing metrics used in evaluating aspects of gender and schooling are not able to do this. The gender parity measure associated with some SDG4 targets might be able to capture proportions of girls and boys from different demographics who have access to both education opportunities for enrolment and learning outcomes, but it is not able to assess whether being educated or passing an examination is associated with the presence or absence of underlying conditions of freedom and opportunity. While the more individual-level datasets compiled by large international development projects on girls’ education could look at these freedoms and opportunities for individual girls, there is not yet a measurement framework which connects them to institutional processes.

A further core idea in the capability approach, as delineated by Robeyns (Citation2017, 45–47), is that people have different abilities to convert material resources (e.g. goods or money) and non-material resources (e.g. educational qualifications) into capabilities and functionings – individual attributes and contextual processes bear on conversion. Therefore, applying the concept of conversion factors to gender and education, we would need to take into consideration that even where there is gender equality in resources (e.g. the same number of school places or textbooks for boys and girls), gender may affect the ability of children to convert these resources into capabilities. Girls may have to perform household chores at specified times or poor boys may have to engage in work in the informal sector to earn additional income. These may have different impacts on how or whether students are able to undertake homework, develop interest in a school subject, or prepare for an examination. We, therefore, need to ask what are the conversion factors relating to participating in education, and how might they be affected by gender? Some conversion factors are institutional: for example, inadequate school water and sanitation. Some are relational, as a culture of shame and derision can prevent girls attending school during their period. Some are individual, as the length of time a girl takes off school during her period may rest on aspects of physical and emotional health. Some conversion factors are social: for example, expectations around care for older or younger members of a household may mean girls have less time and energy for school work. Some are environmental: for example, distance and lack of transport infrastructure may mean the journey to school is more dangerous for girls than boys. Many are intersectional: for example, boys from an indigenous community may have work opportunities linked to travel to large cities and opportunities to learn a national language, while girls from the same community are required to remain in a local neighbourhood where there are only opportunities to learn a local language. Currently, in the SDG indicator framework and the data collected by UIS, there is no accepted range of variables to capture this wide range of conversion factors and process freedoms. Only limited attention is given to human diversity and conversion, by shorthand markers associated with socio-economic status and rurality.

The current SDG4 range of global indicators associates gender equality only with policies, curriculum and assessment (Target 4.7) and with facilities for sanitation (Target 4a). Thus there is limited value pluralism, which Robeyns (Citation2017, 55–57) stresses to be a key element of the capability approach. Robeyns argues that capabilities are value-neutral (capabilities are capabilities, and we cannot label them as bad or good). But values comprise a considerable area of discussion in education, framing debates about the aims of education, and whether this is concerned with, for example, rights, equalities, economic efficiency or personal and social wellbeing (e.g. Peppin Vaughan and Walker Citation2012; Waghid, Waghid, and Waghid Citation2018; Brighouse et al. Citation2018; Curren and Ryan Citation2020; Biesta Citation2020; McCowan and Unterhalter Citation2022). Some scholars show how gendered experiences within learning environments can be negative, with formal aspects of schooling, and ways of acquiring literacy and numeracy, intermixed with restrictions on other capabilities (Greany Citation2012; Okkolin Citation2018; Nussey Citation2019; Adamson Citation2021). Expanding an indicator framework for gender equality that engages with values allows for a range of different interpretations of rights, equalities and gender sensitivity, and helps to counter criticisms associated with global frameworks that they smuggle in Western values and norms under claims of universality (Horner and Hulme Citation2019; Scott and Lucci Citation2015; Abu Moghli Citation2020; Khalid Citation2022).

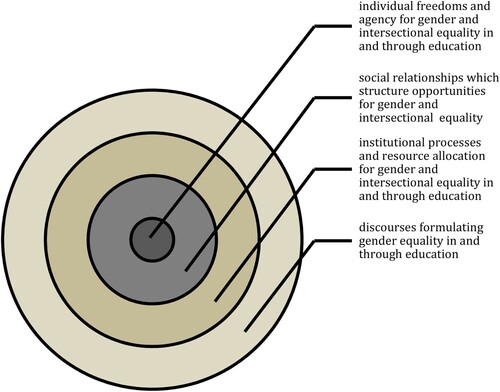

Framing gender inequalities in education in terms of capabilities requires paying attention to the complexities of the physical, political and social environment and the distribution of resources, and the differences in how these can be converted into individual freedoms and opportunities in relation to education. Gender impacts these complexities, distributions and conversions in several forms: as a feature of the social, economic and political environment; through the processes of distribution of resources; in discourses around freedoms and opportunities; and in individual values and interests and how these may be shaped by society. Working through the capability approach to understand gender inequalities in education thus requires a focus on freedoms and how these are constrained by gender and other inequalities rather than a simple focus on gender inequalities as a facet of education outcomes. portrays these interconnected layers of analysis which require any framework for measurement to look at individual freedoms and agency for gender and intersectional equality in and through education, social relationships and institutions which structure these opportunities, and the ideas through which these are described, which contribute to shaping these processes.

Figure 1. Layers of focus for analysis, monitoring and evaluation on gender equality and intersectional opportunities in and through education.

We turn now to illustrate how we have developed the AGEE Framework. Our aspiration is that the Framework can be used to compare gender inequalities in educational capabilities and functionings across national and local contexts.

Operationalising the Capability Approach in Developing an Indicator Framework for Gender Equality in Education

Work on the AGEE project has drawn on reviews of conceptual and empirical literature; and consultation with stakeholders in Malawi, South Africa and international organisations. Building on Robeyns’ key points, and literature on gender, education and capabilities, we identified a number of areas or “domains”, which we considered would be important to have represented in a framework that documented gender equality in educational capability. An initial position paper (Unterhalter Citation2015) was developed in partnership with UNGEI and discussed in a series of meetings. We also drew on theoretical literature concerning measuring capabilities, and operationalising the capability approach through evaluation frameworks (e.g. Alkire et al. Citation2009; Anand et al. Citation2009; Burchardt and Vizard Citation2011; Comim Citation2008; Ibrahim and Alkire Citation2007) and initiatives that had put this into practice in demography (e.g. Chiappero-Martinetti and Venkatapuram Citation2014), gender (e.g. Anand et al. Citation2020; Greco Citation2018; Richardson et al. Citation2019), public health (e.g. Lorgelly et al. Citation2015), education (e.g. Vos and Ballet Citation2018) and child rights (e.g. Biggeri and Mehrotra Citation2011; Yousefzadeh et al. Citation2019).

From a capability approach perspective, measures of educational inequalities and equalities needs to consider both the functionings achieved (both educational functionings and other functionings enabled through education), and the level of freedom and opportunity individuals have to convert specific resources into capabilities and functionings. This requires indicators of the social context, which affects both the distribution of resources, the conversion factors, and the choices that an individual makes from the set of capabilities available to them. In thinking how to organise this information we have identified a number of interconnected but distinct “domains” that we consider need to be represented within a framework, that distil the layers outlined in (above).

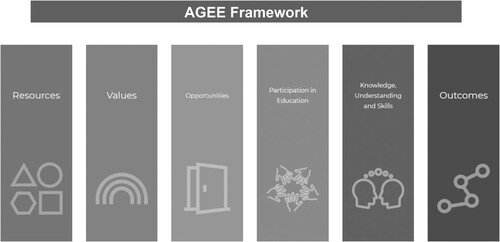

Six domains are proposed for the AGEE Framework ().

Two domains – Resources and Opportunities – aim to capture information relating to capabilities. Three domains focus on functionings – Participation in Education; Knowledge, Understanding and Skills; and Outcomes. The domain of “Values” covers additional normative information concerned with rights, equalities and adaptive preference. Combined, these domains are intended to allow us to portray through the Framework causes of gender inequality and equality in an education system, how much inequality there is, what forms it takes, and how much equality there is. The AGEE Framework allows for an assessment on whether forms of inequality are horizontal (relating to groups, and concerned with cultures and forms of belonging), vertical (associated with distribution of income, qualifications, wealth and health) or process (concerned with learning and teaching interactions), and also to see how successful solutions for problems have been (Unterhalter Citation2021). Assembling a dashboard of indicators linked to the domains of the Framework is intended to look at how successful solutions have been to addressing the injustices associated with the multiplicity of forms of gender inequality in education.

In developing the AGEE Framework, consultations have been held with stakeholders and commentators to gain insight into what constitutes gender inequality in education in different locations and contexts, what data is perceived to be key to evaluating these inequalities, and how data and indicators might be used to bring about change. Our initial focus was an attempt to improve the indicators for SDG4 associated with Targets 4.7 and 4a (Unterhalter Citation2015, Citation2018, Citation2019; Unterhalter and North Citation2017). Subsequently, working with UNESCO’s GEM Report team, we focussed on a framework for monitoring gender equality in education and a possible composite indicator (UNESCO Citation2017, Citation2018b). Since 2016, the GEM Report has adapted some of our ideas for use, including in the 2019 GEM Gender Review (UNESCO Citation2019, 4). Through a series of iterative discussions, we have built an audience for our work amongst a range of practitioners concerned to analyse, monitor and evaluate initiatives for gender equality in education. As outlined on the AGEE websiteFootnote7 this global community of practice works with multilateral, bilateral and international governmental and non-governmental organisations and partnerships, and in national and local organisations.

Our process for selecting the domains, as well as initial steps in exploring the dimensions and indicators associated with gender equality and education that may be included in an indicator dashboard, is participatory, and has entailed extensive and multi-layered consultations and debate. After initial exploratory meetings with experts in 2015, we have since invited report-backs via scholarly work, concept notes, expert discussions and consultations. Between 2018 and 2021, we have held structured discussions with key stakeholders in Malawi, South Africa and internationally in which initial drafts of the Framework have been circulated and discussed. We have engaged with a wide group of practitioners and decision-makers from government, civil society (including some organisations of young people and advocacy groups), multilateral organisations, academics and students.

In , we provide more detailed description of how conceptual ingredients and methods from the capability approach have been utilised in delineating the different domains of the AGEE Framework.

Table 3. Domains of the AGEE framework.

The AGEE Framework remains at present as a conceptual outline that needs further work in order to populate associated indicator dashboards for each domain. This work is the focus of AGEE 2.

AGEE 2: Selecting Indicators for Measuring Gender Equality and Education

AGEE 2, the current phase of the project (2022–2023), will see work on identifying criteria and a selection of indicators for the different domains drawing on routinely collected data. Drawing on literature detailing the development of other measurement frameworks, such as SIGI and the EHRC equality measurement framework (Alkire et al. Citation2009; Burchardt and Vizard Citation2011; Branisa et al. Citation2014), the first stage of this phase of the work entails consultations establishing a list of criteria for selecting indicators. Potential candidates for these criteria, include (i) relevance of the data collected to the domain in the AGEE Framework; (ii) data quality, regularity of collection and burden in assembling data; (iii) usefulness of the data in supporting action on addressing gender inequalities.

In two national contexts (South Africa and Malawi), in addition a longlist of potential indicators that can be used to populate the major domains on the dashboard will be reviewed through a consultative process. Five different strands of work are envisaged using the AGEE Framework to think about measuring and evaluating gender equality in education in the following settings:

International cross country comparison of gender equality in education using a set number of common indicators across countries; this process will underpin steps to develop a composite indicator

National dashboards to be used supporting work on gender equality linked to Education Sector Plans or other national accountability processes; indicators for domains in the AGEE Framework will be developed through national consultations and reflections

Project dashboards to be used drawing on the AGEE Framework for diagnostic, monitoring or evaluation work on projects concerned with girls’ education and gender equality in education

Dashboards for use with mobile or displaced populations, supporting work with a focus on emergencies, conflict and peacebuilding

Dashboards for diagnostic, monitoring or evaluation work in neighbourhoods looking at addressing gender and intersecting inequalities in and through schools.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have used arguments about the multifaceted nature and unmeasurability of gender in education to critique gender parity – the existing widely used metric for gender equality. But we have not eschewed the usefulness of some kind of indicator frame to guide education sector plans or cross-country comparisons. We acknowledge that one indicator cannot do all the work needed to analyse gender inequalities in education, but we have outlined how a suite of indicators can be assembled to do some of this work. We have drawn on the capability approach to develop the AGEE Framework, which we envisage being used to guide a dashboard of indicators which we argue, in contrast to gender parity, better describe the range of relationships associated with gender inequalities within and through education. It is these relationships we hope policy and practice can change and that indicators on the dashboard we propose would keep track of. In looking closely at some conditions of intersecting inequalities in Malawi and South Africa, we have considered how to translate the conceptual language of the capability approach to a language of policy and practice, delineating some of the available data sources and some that still need to be developed or modified.

In concluding, we want to highlight some of the work still to be done and pose some critical questions for the AGEE Framework. Gender parity was a measure developed and used by experts. We do not want to minimise the importance of expert review and validating methods and data, or the usefulness of gender parity as a measure for some aspects of gender equality and education. In line with the capability approach’s emphasis on collective deliberation, our proposed Framework and associated indicator dashboard need critical commentary both from experts as well as from users concerned with activism around gender equality in education, and professional work to make it happen. This commentary concerns the selection of the capability approach, its utilisation, adaption to particular domains, fields and indicators, and the selection and weighting of these. Some assessment needs to be made of what has been left out, the adequacy of the data sources we propose to use, and how feasible the Framework may be in particular countries. The connection of the AGEE Framework with other multi-faceted metrics such as SIGI, WEAI, IPM and EIGE, and the work that has been done on substantive gender equality, human rights and the SDGs (Fredman Citation2016), all need exploring. This remains a large agenda. Engaging with this does not mean we turn away from many critics. We do not engage with the turn to metrics as an evasion of a politics of change committed to women’s rights and gender equality in and through education, but in the hope that documenting more complex relationships, which better accord with what the nuance of qualitative research tells us, will help guide the building of alliances and more thoughtful and appropriately situated change than was possible with only gender parity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elaine Unterhalter

Elaine Unterhalter is a Professor of Education and International Development at UCL (University College London) and Co-Director of the Centre for Education and International Development (CEID). She has published widely on gender, education, international and national policy and practice, with a special focus on intersecting inequalities, the capability approach and approaches to change. Recently published books include Education and International Development. An Introduction (co-edited with Tristan McCowan) and Measuring the Unmeasurable in Education.

Helen Longlands

Helen Longlands is a Lecturer in Education and International Development at the IOE, University College London's Faculty of Education and Society, and Programme Leader for the MA Education, Gender and International Development. Her research interests are interdisciplinary and concerned with gender, inequalities and social justice, with a particular focus on masculinities, transnational relationships of power, and the interconnections between the spaces of education, gender, work and family.

Rosie Peppin Vaughan

Rosie Peppin Vaughan is a Lecturer in Education and International Development at the IOE, University College London's Faculty of Education and Society. Her research focuses on transnational advocacy on girls’ and women’s education, and also draws on the capability approach and the concept of human development to explore the measurement of educational equality and social justice.

Notes

1 The Accountability for Gender Equality in Education (AGEE) project is funded by the ESRC as part of the Raising Learning Outcomes in Education Systems Research Programme (grant number 172694). We gratefully acknowledge the discussions of all members of the AGEE research team and our Advisory Committees in contributing to our insight on the issues reviewed in this article.

2 The first path-breaking study was King and Hill (Citation1993); later key initiatives were signalled by UNESCO’s Education for All Global Monitoring Reports (UNESCO Citation2004, Citation2010, Citation2015a).

3 The OECD SIGI team held a consultation in late 2020 on including education in expanded work on the index.

4 The IDM methodology literature notes that issues around educational equality, the intersection of education with other areas of deprivation, and a number of other issues are not captured by the current methodology (Hunt Citation2017, 30).

5 For details of the indicators and their classification, see: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/tier-classification/.

6 Although no book-length treatment of all features of gender, education and the capability approach exists, recent work has examined how schooling can negatively affect capabilities for some groups of girls (Adamson Citation2021; Nussey Citation2019), gendered experiences within learning environments in higher education (Walker Citation2018), policy level considerations (Manion and Menashy Citation2012; DeJaeghere Citation2012) and female teacher capabilities (Buckler Citation2015; Cin Citation2017; Tao Citation2019).

References

- Abu Moghli, M. 2020. “Reconceptualising Human Rights Education: From the Global to the Occupied.” International Journal of Human Rights 4 (1): 1–35.

- Adamson, L. 2021. “Language of Instruction: A Question of Disconnected Capabilities.” Comparative Education 57 (2): 187–205.

- Alkire, S., F. Bastagli, T. Burchardt, D. Clark, H. Holder, S. Ibrahim, and P. J. M. E. A. F. Vizard. 2009. Developing the Equality Measurement Framework: Selecting the Indicators. December 2021. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20100203020130/http:/www.equalityhumanrights.com/fairer-britain/equality-measurement-framework/.

- Anand, P., G. Hunter, I. Carter, K. Dowding, F. Guala, and M. Van Hees. 2009. “The Development of Capability Indicators.” Journal of Human Develoment and Capabilities 10 (1): 125–152.

- Anand, P., S. Saxena, R. Gonzales Martinez, and H.-A. H. Dang. 2020. “Can Women's Self-Help Groups Contribute to Sustainable Development? Evidence of Capability Changes from Northern India.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 21 (2): 137–160.

- Bardhan, K., and S. Klasen. 1999. “UNDP's Gender-Related Indices: A Critical Review.” World Development 27 (6): 985–1010.

- Bessell, S. 2020. “The Individual Deprivation Measure: A Gender-Sensitive Approach to Multidimensional Poverty Measurement.” In How Gender Can Transform the Social Sciences, edited by M. Sawer, F. Jenkins, and K. Downing, 137–145. Cham: Palgrave Pivot.

- Bhambra, G. K. 2014. “Postcolonial and Decolonial Dialogues.” Postcolonial Studies 17 (2): 115–121.

- Biesta, G. 2020. Educational Research: An Unorthodox Introduction. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Biggeri, M., and S. Mehrotra. 2011. “Child Poverty as Capability Deprivation: How to Choose Domains of Child Well-Being and Poverty.” In Children and the Capability Approach, edited by M. Biggeri, J. Ballet, and F. Comim, 46–75. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Biroli, F., and M. Caminotti. 2020. “The Conservative Backlash Against Gender in Latin America.” Politics & Gender 16(1): 1–38.

- Branisa, B., S. Klasen, M. Ziegler, D. Drechsler, and J. Jütting. 2014. “The Institutional Basis of Gender Inequality: The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI).” Feminist Economics 20 (2): 29–64.

- Brighouse, H., H. F. Ladd, S. Loeb, and A. Swift. 2018. Educational Goods: Values, Evidence and Decision-Making. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Buckler, A. 2015. Quality Teaching and the Capability Approach: Evaluating the Work and Governance of Women Teachers in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Burchardt, T., and P. Vizard. 2011. “Operationalizing’ the Capability Approach as a Basis for Equality and Human Rights Monitoring in Twenty-First-Century Britain.” Journal of Human Develompent and Capabilities 12 (1): 91–119.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Center for Global Development. 2020. Introducing the Girls’ Education Policy Index. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/introducing-girls-education-policy-index.

- Chiappero-Martinetti, E., and S. Venkatapuram. 2014. “The Capability Approach: A Framework for Population Studies.” African Population Studies 28 (2): 708–720. doi:10.11564/28-2-604.

- Chiappero Martinetti, E., S. Osmani, and M. Qizilbash, eds. 2021. The Cambridge Handbook of the Capability Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cin, F. M. 2017. Gender Justice, Education and Equality: Creating Capabilities for Girls’ and Women’s Development. Johannesburg: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Comim, F. 2008. “Measuring Capabilities.” In The Capability Approach: Concepts, Measures and Applications, edited by F. Comim, M. Qizilbash, and S. Alkire, 157–200. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Comim, F., M. Qizilbash, and S. Alkire. 2008. The Capability Approach: Concepts, Measures and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cooper, D. 2019. “A Very Binary Drama: The Conceptual Struggle for Gender's Future.” King's College London Law School Research Paper (2019-34).

- Cranny-Francis, A., W. Waring, P. Stavropoulos, and J. Kirkby. 2017. Gender Studies: Terms and Debates. London: Macmillan.

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139-168.

- Crocker, D. A. 2009. Global Development: Agency, Capability, and Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Curren, R., and R. M. Ryan. 2020. “Moral Self Determination: The Nature, Existence and Formation of Moral Motivation.” Journal of Moral Education 49 (3): 295–315.

- Decker, A. C., and G. Baderoon. 2018. “African Feminisms: Cartographies for the Twenty-First Century.” Meridians 17 (2): 219–231.

- DeJaeghere, J. 2012. “Public Debate and Dialogue from a Capabilities Approach: Can it Foster Gender Justice in Education?” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 13 (3): 353–371.

- DeJaeghere, J. 2017. Educating Entrepreneurial Citizens: Neoliberalism and Youth Livelihoods in Tanzania. London: Routledge.

- DeJaeghere, J. 2020. “Reconceptualizing Educational Capabilities: A Relational Capability Theory for Redressing Inequalities.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 2 (1): 17–35.

- de Paz, C., M. Muller, A. M. Munoz Boudet, and I. Gaddis. 2020. Gender Dimensions of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33622

- Durrani, N., and A. Halai. 2020. “Gender Equality, Education, and Development: Tensions Between Global, National, and Local Policy Discourses in Postcolonial Contexts.” In Grading Goal Four, edited by A. Wulff, 65–95. Leiden: Brill Sense.

- Equal Measures. 2022. ‘Back to Normal’ is Not Enough: the 2022 SDG Gender Index (Woking: Equal Measures 2030).

- Espinoza-Delgado, J., and S. Klasen. 2018. “Gender and Multidimensional Poverty in Nicaragua: An Individual Based Approach.” World Development 110: 466–491.

- European Institute for Gender Equality. 2022. Gender Equality Index. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/about.

- Fennell, S., and M. Arnot. 2009. Gender Education and Equality in a Global Context: Conceptual Frameworks and Policy Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Ferrant, G., Fuiret, L. and Zambrano, E. (2020). “The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) 2019: A Revised Framework for Better Advocacy.” OECD Development Centre Working Papers 342, Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Fredman, S. 2016. “Substantive Equality Revisited.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 14 (3): 712–738.

- Frost, S. 2011. “The Implications of the New Materialism for Feminist Epistemology.” In Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science: Power in Knowledge, edited by H. E. Grasswick, 69–83. New York: Springer.

- Fry, D., X. Fang, S. Elliott, T. Casey, X. Zheng, J. Li, L. Florian, and G. McCluskey. 2018. “The Relationships Between Violence in Childhood and Educational Outcomes: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Child Abuse & Neglect 75: 6–28.

- Gabizon, S. 2016. “Women’s Movements’ Engagement in the SDGs: Lessons Learned from the Women’s Major Group.” Gender & Development 24 (1): 99–110.

- Gaye, A., J. Klugman, M. Kovacevic, S. Twigg, and E. Zambrano. 2010. “Measuring key Disparities in Human Development: The Gender Inequality Index.” Human Development Research Paper, 46, 41.

- Global Partnership for Education (GPE). 2016. Gender Equality Policy and Strategy, 2016-2020. Washington, DC: Global Partnership for Education.

- Greany, K. 2012. “Education as Freedom?: A Capability-Framed Exploration of Education Conversion Among the Marginalised: The Case of Out-Migrant Karamajong Youth in Kampala.” PhD Thesis, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Greco, G. 2018. “Setting the Weights: The Women’s Capabilities Index for Malawi.” Social Indicators Research 135 (2): 457–478.

- Grek, S. 2020. “Prophets, Saviours and Saints: Symbolic Governance and the Rise of a Transnational Metrological Field.” International Review of Education 66 (2): 139–166.

- Grek, S., C. Maroy, and A. Verger. 2021. World Yearbook of Education 2021. Accountability and Datafication in the Governance of Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Guedes, A., S. Bott, C. Garcia-Moreno, and M. Colombini. 2016. “Bridging the Gaps: A Global Review of Intersections of Violence Against Women and Violence Against Children.” Global Health Action 9.

- Harding, S. 2017. “Latin American Decolonial Studies: Feminist Issues.” Feminist Studies 43 (3): 624–636.

- Hill Collins, P., and S. and Bilge. 2016. Intersectionality. Cambridge: Polity.

- Horner, R., and D. Hulme. 2019. “From International to Global Development: New Geographies of 21st Century Development.” Development and Change 50 (2): 347–378.

- Hunt, S. 2017. The Individual Deprivation Measure: Methodology Update 2017. Melbourne: Australian National University, Canberra and International Women’s Development Agency.

- Ibrahim, S., and S. Alkire. 2007. “Agency and Empowerment: A Proposal for Internationally Comparable Indicators.” Oxford Development Studies: The Missing Dimensions of Poverty Data 35 (4): 379–403.

- International Food Policy Research Institute. 2022. Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI). Accessed 22 June 2022. https://www.ifpri.org/project/weai.

- Khalid, A. 2022. “The Negotiations of Pakistani Mothers’ Agency with Structure: Towards a Research Practice of Hearing ‘Silences’ as a Strategy.” Gender and Education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/09540253.2022.2027888.

- Khoja-Moolji, S. 2021. Sovereign Attachments: Masculinity, Muslimness, and Affective Politics in Pakistan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- King, K. 2017. “Lost in Translation? The Challenge of Translating the Global Education Goal and Targets Into Global Indicators.” Compare 47 (6): 801–817.

- King, E. M., and M. A. Hill. 1993. Women’s Education in Developing Countries: Barriers, Benefits and Policies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kwachou, M. 2020. “Cameroonian Women’s Empowerment Through Higher Education: An African-Feminist and Capability Approach.” Doctoral Thesis, University of the Free State, South Africa.

- Longlands, H. 2020. Gender, Space and City Bankers. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Loots, S., and M. Walker. 2016. “A Capabilities-Based Gender Equality Policy for Higher Education: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 17 (2): 260–277.

- Lorgelly, P. K., K. Lorimer, E. A. L. Fenwick, A. H. Briggs, and P. Anand. 2015. “Operationalising the Capability Approach as an Outcome Measure in Public Health: The Development of the OCAP-18.” Social Science & Medicine 142: 68–81.

- Manion, C., and F. Menashy. 2012. “The Prospects and Challenges of Reforming the World Bank’s Approach to Gender and Education: Exploring the Value of the Capability Policy Model in The Gambia.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 14 (2): 214–240.

- Martino, W., and W. Cumming-Potvin. 2018. “Transgender and Gender Expansive Education Research, Policy and Practice: Reflecting on Epistemological and Ontological Possibilities of Bodily Becoming.” Gender and Education 30 (6): 687–694.

- Maslak, M. A. 2008. The Structure and Agency of Women’s Education. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- McCann, H., and W. Monaghan. 2020. Queer Theory now: From Foundations to Futures. London: Red Globe Press/ Springer.

- McCowan, T., and E. Unterhalter. 2022. Education and International Development: An Introduction (2nd edition). London: Bloomsbury.

- Merry, S. E. 2016. The Seduction of Quantification: Measuring Human Rights, Gender Violence, and Sex Trafficking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mjaaland, T. 2021. Revolutionary Struggles and Girls’ Education: At the Frontiers of Gender Norms in North-Ethiopia. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Monkman, K. 2021. “Gender Equity in Global Education Policy.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, edited by G. W. Noblit. Oxford: Oxford University Press (online resource).

- Nussbaum, M. 2011. Creating Capabilities. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Nussey, C. 2019. “Adult Education, Gender and Violence in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa”. Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London).

- Nussey, C. 2019. Unpublished PhD thesis, University College London.

- OECD. 2022. Social Institutions and Gender Index. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://www.genderindex.org.

- Okkolin, M.-A. 2018. Education, Gender and Development: A Capabilities Perspective. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Okwuosa, M., and G. Daimond. 2021. “The “shadow pandemic”: What’s in a Narrative?” Blog post UNGEI UN: UNGEI. https://www.ungei.org/blog-post/shadow-pandemic-whats-narrative.

- Pankhurst, C. 2021. “What Do We Know About the Links Between Girls’ Education and Climate and Environment Change?” Blog post AGEE website: https://www.gendereddata.org/how-does-climate-change-relate-to-gender-equality-in-education/.

- Parkes, J. 2015. Gender Violence in Poverty Contexts: The Education Challenge. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Parkes, J., S. Datzberger, C. Howell, L. Knight, J. Kasidi, T. Kiwanuka, R. Nagawa, D. Naker, and K. Devries. 2020. “Young People, Inequality and Violence During the COVID-19 Lockdown in Uganda.” COVAC Working Paper, http://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/2p6hx.

- Peppin Vaughan, R. 2007. “Measuring Capabilities: An Example from Girls’ Schooling.” In Sen's Capability Approach and Social Justice in Education, edited by E. Unterhalter, and M. Walker, 109–130. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Peppin Vaughan, R., and M. Walker. 2012. “Capabilities, Values and Education Policy.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 13 (3): 495–512.

- Pereznieto, P., A. Magee, and N. Fyles. 2017. Evidence Review: Mitigating Threats to Girls’ Education in Conflict-Affected Contexts: Current Practice. New York: UNGEI and ODI.

- Plantenga, J., C. Remery, H. Figueiredo, and M. Smith. 2009. “Towards a European Union Gender Equality Index.” Journal of European Social Policy 19 (1): 19–33.

- Population Council. 2022. Research: The Evidence for Gender and Education Resource. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://www.popcouncil.org/research/eger.

- Prah Ruger, J. 2018. Global Health Justice and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rao, N., E. T. Lawson, W. N. Raditloaneng, D. Solomon, and M. N. Angula. 2019a. “Gendered Vulnerabilities to Climate Change: Insights from the Semi-Arid Regions of Africa and Asia.” Climate and Development 11 (1): 14–26.

- Rao, N., A. Mishra, A. Prakash, C. Singh, A. Qaisrani, P. Poonacha, and C. Bedelian. 2019b. “A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Women’s Agency and Adaptive Capacity in Climate Change Hotspots in Asia and Africa.” Nature Climate Change 9 (12): 964–971.

- Richardson, R., N. Schmitz, S. Harper, and A. Nandi. 2019. “Development of a Tool to Measure Women’s Agency in India.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 20 (1): 26–53.

- Robeyns, I. 2003. “Sen’s Capability Approach and Gender Inequality: Selecting Relevant Capabilities.” Feminist Economics 9 (2–3): 61–92.

- Robeyns, I. 2017. Wellbeing, Freedom and Justice: The Capability Approach re-Examined. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

- Salo, E. 2001. “Talking About Feminism in Africa.” Agenda (Durban, South Africa) 16 (50): 58–63.

- Save the Children. 2020. The Global Girlhood Report. London: Save the Children. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/18201/pdf/global_girlhood_report_2020_africa_version_2.pdf

- Scott, A., and P. Lucci. 2015. “Universality and Ambition in the Post-2015 Development Agenda: A Comparison of Global and National Targets.” Journal of International Development 27 (6): 752–775.

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred Knopf.

- Sen, A. 2011. Peace and Democratic Society. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

- Sen, G., and A. Mukherjee. 2014. “No Empowerment Without Rights, No Rights Without Politics: Gender-Equality, MDGs and the Post-2015 Development Agenda.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 15 (2-3): 188–202.

- Sperling, G., and R. Winthrop. 2015. What Works in Girls’ Education: Evidence for the World’s Best Investment. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Stromquist, N. 1995. “Romancing the State: Gender and Power in Education.” Comparative Education Review 39 (4): 423–454.

- Stromquist, N. P., S. J. Klees, and J. Lin. 2017. Women Teachers in Africa: Challenges and Possibilities. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Tao, S. 2019. “Female Teachers in Tanzania: An Analysis of Gender, Poverty and Constrained Capabilities.” Gender and Education 31 (7): 903–919.

- Tisdell, C., K. Roy, and A. Ghose. 2001. “A Critical Note on UNDP's Gender Inequality Indices.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 31 (3): 385–399.

- UNDP. 2022. Gender Inequality Index. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematic-composite-indices/gender-inequality-index#/indicies/GII.

- UNESCO. 2004. “Gender and Education for All: The Leap to Equality.” EFA Global Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2010. “Reaching the Marginalized.” EFA Global Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2015a. ‘Gender and EFA 2000-2015: Achievements and Challenges.” EFA Global Education Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2017. “Accountability in Education: Meeting Our Commitments.” Global Education Monitoring Report 2017/18. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2018a. “Migration, Displacement and Education.” Global Education Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2018b. ‘Meeting Our Commitments to Gender Equality in Education.” Global Education Monitoring Report Gender Review. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2018c. Education and Gender Equality. Accessed 3 March 2021. https://en.unesco.org/themes/women-s-and-girls-education.

- UNESCO. 2019. “Migration, Displacement and Education.” Global Education Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2020. “A New Generation: 25 Years of Efforts for Gender Equality in Education.” Global Education Monitoring Report Gender Review. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2021. When Schools Shut: Gendered Impact of COVID 19 School Closures. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379270).

- UNESCO. 2022a. Evidence on the Gendered Impacts of Extended School Closures: A Systematic Review. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2022b. Global Education Monitoring Report: World Inequality Database on Education. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://www.education-inequalities.org.

- UNESCO. 2022c. Global Education Monitoring Report: PEER. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://education-profiles.org.

- UNESCO. 2022d. Global Education Monitoring Report: PEER. Accessed 22. June 2022 https://education-profiles.org.

- UNGEI. 2018. UNGEI Strategic Directions, 2018-2023. New York: UN Girls Education Initiative. https://www.ungei.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/UNGEI-Strategic-Directions-2018-2023-plan-eng.pdf.

- UNICEF. 2014. Hidden in Plain Sight: A Statistical Analysis of Violence Against Children. New York: UNICEF.

- UNICEF. 2022. Gender Transformative Education: Reimagining Education for a More Just and Inclusive World. New York: UNICEF.

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations. 2020a. “SDG Indicators: Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” Accessed 14 December 2020. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/.

- United Nations. 2020b. “IAEG-SDGs: Tier Classification for Global SDG Indicators”. Accessed 14 December 2020. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/tier-classification/.

- University of Oxford. 2022. RISE. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://riseprogramme.org.

- Unterhalter, E. 2005. “Fragmented Frameworks: Researching Women, Gender, Education and Development.” In Beyond Access: Developing Gender Equality in Education, edited by S. Aikman, and E. Unterhalter, 15–35. Oxford: Oxfam Publishing.

- Unterhalter, E. 2014. “Measuring Education for the Millennium Development Goals: Reflections on Targets, Indicators, and a Post-2015 Framework.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 15 (2-3): 176–187.

- Unterhalter, E. 2015. “Measuring Gender Inequality and Equality in Education.” Concept Note for UNGEI Workshop, London & New York: UN Girls Education Initiative.

- Unterhalter, E. 2016. “Gender and Education in the Global Polity.” In Handbook of Global Education Policy, edited by K. Mundy, A. Green, B. Lingaard, and A. Verger, 111–127. New York: Wiley.

- Unterhalter, E. 2017a. “Negative Capability? Measuring the Unmeasurable in Education.” Comparative Education 53 (1): 1–16.

- Unterhalter, E. 2017b. “A Review of Public Private Partnerships Around Girls’ Education in Developing Countries: Flicking Gender Equality on and Off’.” Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy 33 (2): 181–199.

- Unterhalter, E. 2018. “Silences, Stereotypes and Local Selection: Reflections for the SDGs on Some Experiences with the MDGs and EFA.” In Global Education Policy and International Development: New Agendas, Issues and Policies (2nd Edition), edited by A. Verger, M. Novelli, and H. Altinyelken, 75–96. London: Bloomsbury.

- Unterhalter, E. 2019. “The Many Meanings of Quality Education: Politics of Targets and Indicators in SDG 4.” Global Policy 10: 39–51.

- Unterhalter, E. 2021. “Addressing Intersecting Inequalities in Education.” In Education and International Development: An Introduction (2nd edition), edited by T. McCowan, and E. Unterhalter, 19–38. London: Bloomsbury.

- Unterhalter, E., C. Howell, and J. Parkes. 2019. Achieving Gender Equality in and Through Education. Washington: Global Partnership for Education. https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/achieving-gender-equality-and-through-education-knowledge-and-innovation-exchange-kix-discussion-paper.

- Unterhalter, E., and A. North. 2017. Education, Poverty and Global Goals for Gender Equality: How People Make Policy Happen. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Unterhalter, E., A. North, M. Arnot, C. Lloyd, R. Moletsane, E. Murphy-Graham, J. Parkes, and M. Saito. 2014. Girls’ Education and Gender Equality: Education Rigorous Literature Review. London: DfID.

- Unterhalter, E., L. Robinson, and M. Ron Balsera. 2020. ‘The Politics, Policies and Practices of Intersectionality: Making Gender Equality Inclusive and Equitable in and Through Education.” Background Paper prepared for the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report 2020. Paris: UNESCO.

- UN Women. 2020. COVID-19 and the Care Economy: Immediate Action and Structural Transformation for a Gender-Responsive Recovery. New York: UN Women.

- UN Women. 2021. G7 Working Group on Education Recommendations to Action Coalition Leaders. New York: UN Women. https://forum.generationequality.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/G7%20Working%20Group%20on%20Education%20-%20papers%20on%20Action%20Coalitions.pdf.

- Vos, R., and J. Ballet. 2018. “Formal Education, Well-Being and Aspirations: A Capability-Based Analysis on High School Pupils from France.” In New Frontiers of the Capability Approach, edited by F. Comim, S. Fennell, and P. B. Anand, 549–570. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Waghid, Y., F. Waghid, and Z. Waghid. 2018. Rupturing African Philosophy on Teaching and Learning: Ubuntu, Justice and Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Walker, M. 2018. “Aspirations and Equality in Higher Education: Gender in a South African University.” Cambridge Journal of Education 48 (1): 123–139.

- Wilson-Strydom, M., and M. A. Okkolin. 2016. “Enabling Environments for Equity, Access and Quality Education Post-2015: Lessons from South Africa and Tanzania.” International Journal of Educational Development 49: 225–233.

- World Bank. 2022. Human Capital Project: 2020 Human Capital Index. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/human-capital.

- World Economic Forum. 2021. Global Gender Gap Report 2021. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021/.

- Wulff, A., ed. 2020. Grading Goal Four: Tensions, Threats and Opportunities in the Sustainable Development Goal on Quality Education. Leiden: Brill Publishers.

- Yousefzadeh, S., M. Biggeri, C. Arciprete, and H. Haisma. 2019. “A Capability Approach to Child Growth.” Child Indicators Research 12 (2): 711–731.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2006. “Intersectionality and Feminist Politics.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 13 (3): 193–209.

- Żuk, P., and P. Żuk. 2020. “‘Murderers of the Unborn’ and ‘Sexual Degenerates’: Analysis of the ‘Anti-Gender’ Discourse of the Catholic Church and the Nationalist Right in Poland.” Critical Discourse Studies 17 (5): 566–588.