ABSTRACT

Juxtaposed against literature that views mothers’ role for their daughters’ education as a human capital this paper reimagines their role by foregrounding Pakistani mothers’ agency in contexts with limited opportunities. This is achieved by theorising negative capability (NC) as an analytical framework drawing on available theorisations of the concept and define it as an agentive passive refusal to be intellectually paralysed by disadvantage. We demonstrate how the concept can be applied for empirical analysis. The paper takes an ethical stance that researchers should acknowledge that regardless of contextual difficulties people’s agentive and intellectual faculties remain intact. Structural inequalities need to be challenged but their agentive potential also recognised. With a firm commitment that opportunities need to be made equal this paper builds on the second point to argue that even in the face of extreme disadvantage mothers’ intellectual capacities to progress towards goals remain functional. We challenge the objectification of the marginalised and propose an analytical approach to understand difficulties faced as well as agency exercised by mothers facing socio-economic constraints. This work has implications for the capability approach that falls short of addressing issues of power, and policy that fails to understand the context.

Introduction

Over the past two decades research in Pakistan has identified that when mothers are educated or have greater control on household decisions more resources are spent on their daughters’ education and their daughters are more likely to be enrolled in school and achieve better educational outcomes. Little is known about the mothers’ own experiences and perceptions.

We address this gap by adopting a qualitative approach to explore the capabilities of mothers in achieving their aspirations for their daughters’ education.

The article is organised into four sections. In the first section we provide a review of relevant empirical literature followed by a theoretical framing of the article. Secondly we discuss methods used for the data collection together with a summary of the sample and site of the research. In the third section we apply the theoretical framework to analyse a mothers’ story and show how she exercises her agency in a context of socio-economic constraints. In the fourth section we conclude by discussing the nuances uncovered through the application of the framework and the insights that have emerged from the analysis.

Understanding Mothers’ Influence on Their Daughters’ Education Through Literature

A number of previous studies in Pakistan have explored mothers’ influence on their daughters’ education finding that children of mothers who have some education spend more time on educational activities (Andrabi, Das, and Ijaz Citation2012), perform better at school (Faize and Dhar Citation2011), are more likely to be enrolled in school (Seshie-Nasser and Oduro Citation2016) and complete secondary school (Mukherjee and Das Citation2008), are less likely to drop out from school (Andrabi, Das, and Khwaja Citation2008; Hazarika Citation2001), and exercise greater freedom to make choices (Bano and Ferra Citation2018). Other studies have identified that with increased education mothers’ control over household decisions increases (Shoaib, Saeed, and Cheema Citation2012) giving them more control over their lives (Humala and Mujahid-Mukhtar Citation2002) with increased participation in household decision-making (Anwar, Shoaib, and Javed Citation2013; Meraj and Sadaqat Citation2016). Consequently mothers are more likely to allocate resources more equitably amongst their children (Davis, Drey, and Gould Citation2009; Duflo Citation2012;) with a larger effect on their daughters’ enrolment (Kingdon Citation2005). Some research in Pakistan has looked deeper into the power relations and gendered dynamics within which Pakistani mothers are situated (Ali Citation2018; Naz et al. Citation2013; Rehman and Azam Roomi Citation2012), practice their agency by resisting the hegemonic norms through indirect contestations (Bhatti and Jeffery Citation2012), passively transforming gendered norms (Malik and Courtney Citation2011; Noureen Citation2015) and gain control over their children’s education decisions (Ashraf and Farah Citation2007). The literature shows that mothers are more likely to support their daughters “enabling them to realise their capabilities” (Warrington and Kiragu Citation2012, 307) and encouraging them at key points (Guinée Citation2014).

Earlier work has been undertaken to find associations between mothers’ education and their daughters’ education outcomes. Such an approach considers mothers’ role as a means to an end, an improvement in human capital and investment in future outcomes for their daughters in the future. Analysis done in this regard shows that an increase in the education of mothers causes a positive shift in the health outcomes and an increase in school enrolments and achievement (King and Hill, Citation1997). Quantitative research has also shown that lower parental educational attainment is linked to less education for children (Dreze & Kingdon, Citation1999). This body of work also includes other aspects associated with mothers such as children’s health outcomes with mothers’ education. The issue is that evidence also shows that regardless of attributes (having received education for example), wherever possible, mothers support their daughters’ education (Nakajima et al., Citation2019) so there needs to be a different way of understanding a mothers’ role. The capability approach provides such a lens, to understand mothers’ support as an “end in itself”, not just a mode of reaching an outcome for their daughters. The assumption is that when mothers’ efforts are valued this way there is a higher likelihood that social outcomes will automatically emerge.

It is evident from the literature reviewed so far that the mothers’ role for their daughters’ education has been either explored by measuring the human capital of mothers in the shape of education and/or autonomy, without going deeper into the processes and relationships that reflect the true nature of the agency inherent in the efforts of mothers, or focusing on the structural constraints that inhibit their ability to exercise their influence. What is missing in both approaches is a clear conceptualisation of a mothers’ role that allows for their voices to emerge as they engage with the structures of domination and enact their agency to achieve their daughters’ wellbeing. Amartya Sen’s CA allows the theoretical space for exploring mothers’ own experiences as central, therefore an end in itself.

Exploring Mothers’ “Beings and Doings”: Mothers’ Role and Their Capabilities

CA allows for the exploration of these dynamics through the eyes of mothers. Sen (Citation1999) explains that the CA is focused on “the substantive freedom of people to lead lives they have reason to value and to enhance the real choice they have” (294). Translating this into the present study, if mothers value education for their daughters and wish to support them, then the analytical lens will seek to understand whether mothers have the freedom to achieve this. It is important to note that the CA allows for much more than a value-laden understanding of capabilities as “freedom enhancing” (Robeyns Citation2005). There is space to negotiate whether capabilities can be envisioned in contexts of “unfreedoms”. There is a possibility to bring into the fold the idea of capability in contexts of “unfreedoms” if we understand capabilities as value neutral. In this case however, NC emerges in contexts of unfreedom. Thus, the paper supports Robeyn’s argument on the value neutral nature of capabilities to allow “unfreedoms” as an existing condition within capability analyses. This is controversial because from a social justice perspective the contexts are capability restricting. However if we value people's subjective struggles it is possible to imagine agency within a context of unfreedom. NC thus does not connote to conditions and contexts of “freedom” but rather something emerging from the absence of freedoms. To further explore capabilities as an approach I engage with some key ideas of the approach.

Mothers’ Aspirations (Beings) and Their Actions (Doings) to Support Their Daughters’ Education

Mothers’ valued doings (things a person wants to do) and beings (the physical states in which a person would prefer to be) are collectively called functionings. If mothers value education for their daughters then their aspirations and actions in support of their daughters’ education may be seen as their functionings. In the capability approach literature (hereafter CA) aspirations are central because they are not only indicative of people’s striving (Nussbaum Citation2016) but also show patterns of how people exercise agency in order to fulfil their aspirations (Hart Citation2016). Aspirations have been defined as “vague, from dreams and fantasies to concrete ambitions and goals” (Gutman and Akerman Citation2008, 2). In Pakistan parental aspirations have been associated with greater educational achievements of children (Ashraf Citation2016). Aspirations are conceived in a social context and the agency to execute these aspirations is important since conditions may require prioritisation of certain aspirations.

Mothers’ Agency to Enact Their Aspirations

Sen (Citation1999, 18 & 19) describes an agent as someone “who acts and brings about change, and whose achievements can be judged in terms of her own values and objectives, whether or not we assess them in terms of some external criteria as well”. This has indeed been a key concern in empowerment research, where women are deemed to be knowledge bearers in their stories (Kabeer Citation1999). Thus, a concern for agency acknowledges mothers as central to the process of social change (Sen) and authenticates their perspectives as legitimate (Kabeer). But what of mothers’ environment? Something needs to be said about the context in which these mothers live.

Pakistan gained the status of an independent state in 1947. This occurred after remaining a colony for nearly a century. The history of struggle for independence predates the birth of Pakistan. Under the period of colonisation, the people of the sub-continent (now called Pakistan, Bangladesh and India) fought and organised under the banner of freedom for their country. Women were at the forefront of the struggle for independence. Patriarchy works in similar forms in different parts of the world. Just like the post-world war experiences of women in the West, women in Pakistan were also pushed to the margins once the nascent state was created (Malik Citation2017). Women in Pakistan have responded to patriarchy in both overt and covert ways. Overt activism emerged at important historical turning points, such as Zia’s dictatorship, which introduced anti-feminist laws in the 1980s, or women’s marches in the present. Other more covert ways have been documented elsewhere (for example Critelli’s Citation2010 work). Alluding to this Jafar (Citation2005) in the opening of her article quotes:

With chains of matrimony and modesty You can shackle my feet; The fear will still haunt you; That crippled, unable to walk I shall continue to think. (Kishwar Naheed, a contemporary poet, quoted in Mumtaz andShaheed Citation1987, 77)

(A)agency [appears] not as a synonym for resistance to relations of domination but as a capacity for action that historically specific relations of subordination enable and create … agency whose meaning and effect are not captured within the logic of subversion and resignification of hegemonic norms. (Mahmood Citation2006, 33 & 34)

In these discussions of agency women’s attempts to exercise agency seem to be in relation with structural affordances. One way of conceptualising structure is by exploring it through Bourdieu’s concept of field which has been applied by capability scholars to investigate aspirations and their dependability on social structures (Hart Citation2012). The connections between aspirations, agency and structure need to be established before focusing on the form of agency that has been emerging in the literature about women/mothers in diverse contexts like Pakistan.

Aspirations have been discussed as an important concern in the capability literature. Conradie (Citation2013) from her action research with women from Khaylitsha, South Africa explored their voicing of aspirations and later the achievement of their aspirations through agency within existing cultural constraints. Despite the understanding that aspirations are negatively adapted/adjusted (Khader Citation2009) scholars like Conradie and Robeyns Citation2013) demonstrate through their research that depending on the context “women have aspirations, are very willing to reflect upon and voice their aspirations, and indeed find that a valuable process” (569). In some cases aspirations may leverage an agency-unlocking capacity. From this work there are a few learnings that are important for this paper. The agentive capacity of aspirations is “context” dependent and that aspirations are temporally conceived and are dynamic.

DeJaeghere (Citation2018) in her longitudinal research of young girls’ aspirations for education in vocational centres in Tanzania argues that aspirations for education have the potential to expand opportunities. However in contexts of structural inequalities such aspirations can also go unfulfilled. DeJaeghere shows “how aspirations and agency are dialectically related and socially situated, allowing for openings in agency to occur even when faced with gendered constraints to aspirations” (237).

Bringing together these discussions one may argue that aspirations have the potential of what Conradie and Robeyns call “agency-unlocking”. Furthermore, aspirations and agency exist in a dialectic relationship with each other in contexts of oppression and inequality (DeJaeghere). These together leave “openings” for agency to occur even in conditions marked by gendered inequalities and oppression. We extend this work further by connecting it with Unterhalter’s (Citation2017, Citation2018) theorisation of “negative capability”.

Drawing on Unterhalter we define NC as the ability of people, historically living in complexity and inequality, to pursue their goals and produce something creative for themselves or others. The way that we use NC does not put the burden of responsibility on people to become “able”, “achieve”, “exist”, “persevere” or “survive” structures of oppression and inequality but rather holds researchers, policy makers and practitioner responsible for, on the one hand strive towards equality and social justice for all, and on the other hand, acknowledge and respect people as agents in their own lives regardless of the difficulties they navigate. The core of this understanding is to move away from the objectification of people living in inequalities and reimagine them as agents in their own lives. In the section below we elaborate on how Unterhalter uses and introduces the concept.

Negative Capability (NC): Mothers’ Agency to Achieve Wellbeing in Highly Constrained Circumstances

Unterhalter (Citation2017) presents NC as the capability of a person to live in uncertain, possibly precarious conditions, without being paralysed psychologically, and to be able to generate something creative from it. There is an element of temporality involved in this idea. One may be affected in the present and may take a decision to withdraw from aspirations and actions (as I discussed in my related work, Khalid, Citation2022) in the immediate moment but the potential to strategise and to maintain intellectual capacities is key to this understanding. Acknowledging this means that an active process goes on where agency is realised but is also responsive to structural affordances. The importance of these negotiations can be understood from the perspective of relationalities between agency and structure. Unterhalter and Conradie (Citation2019) argue that sometimes a dialectic relationship between the structures of domination and agency allows people to engage and disengage from their contexts to escape the disabling implications of oppression. In some associated work, the first author argues that contexts are dynamic and so are people’s aspirations, therefore any imagining of context as static runs the risk of objectifying people living in oppressive conditions (Khalid Citationforthcoming). How do we describe this potential of Pakistani mothers within this context to reach their aspirations by exercising their agency? This question is positioned to the researcher to unsee an object in oppression and instead reimagine an actor living in unique conditions and navigating their contexts to achieve their aspirations. This does not mean that such efforts be taken as what some call “heroic condition (s)” (Hansen, Citation2019, 28) and expect that one needs to have these to succeed, rather a sensitive acknowledgment by the researcher/practitioner/policymaker of a sensible, rational, and agentic “other” existing in contexts that are unique to their situation. Going forward we focus on this ability of the mothers to explore how this can be examined with the help of Unterhalter’s theorisation of NC.

Unterhalter (Citation2018) connects NC with education and the vital role it plays in generating the ability to accept complexities and be generative of creativity. She demonstrates this by conducting a detailed analysis of the stories of three revolutionaries which during their imprisonment developed educational projects for themselves and their prison inmates who were kept under extreme privations on island prisons. The agency in pursuing education protected them from the immediate consequences of their unbearable conditions, until an educational space was created, which they all valued. These prisoners demonstrated a form of NC that allowed them to escape the mental detriments of living with sustained oppression. Although in a different context and form, one may explore mothers’ aspirations and their actions of support to develop an understanding of how some of them create value existing within conditions of oppression. We further unpack how Unterhalter theorises NC in her work.

Deconstructing the ‘Negative’ in Negative Capability (NC) and Proposing a Conceptual Framework

Unterhalter (Citation2017) gives three interpretations of the term “negative” in the concept of NC which can be related with the situation of mothers in this study. First, it can be translated simply as unpleasant and unlikeable. In that sense it signals the presence of something disagreeable. It is a form of disadvantage that is persistent, ongoing, and to some extent, normalised; and is similar to the disadvantage endured by many women, including mothers. The second refers to the capacity of someone to “negate” in other words refuse, to abide by some predefined constructs. This can be linked to Keats’s idea of refusing to be psychologically harmed by insecurity, where an individual faces problem but refuses to be intimidated by them. In the third interpretation, Unterhalter invites a deeper understanding of people’s efforts and contexts (Citation2017). The second and third meanings refer to the ability of mothers to shield themselves from the despair of their situation, and to pursue something creative (education for their daughters).

Moving Beyond: Negative Capability (NC) as an Analytical Framework

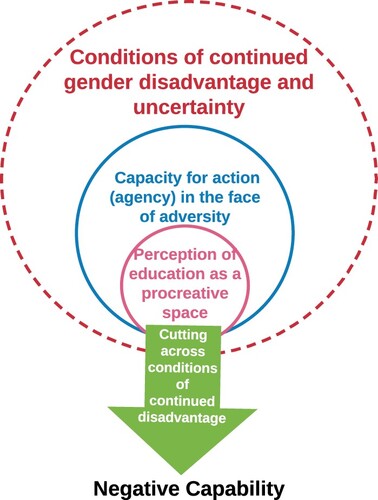

In this section, we extend Unterhalter’s work by extracting three analytical themes which have helped us develop the conceptual framework for this paper (see ): (i) the prevalence of continued and persistent disadvantage and uncertainty which coincides with Unterhalter’s first meaning of NC, which is repression (outer dotted circle in ). In the case of mothers, it refers to the conditions of continued gender disadvantage and uncertainty. (ii) developing the capacity for action (agency) even in the face of extreme conditions. In this context rejecting the paralytic effects of oppression and continue to pursue goals (middle circle in the figure). Mothers show great strength in the face of adversity to ensure their daughters receive an education; and (iii) the importance of pursuing education as something creative which motivates mothers to move past the despair towards something creative (inner circle in ).

Methods

The data for this paper comes from a bigger PhD project for which 30 families from Rural Pakistan were interviewed in 2017.

The participant mother, Bushra (pseudonyms being used to ensure anonymity) – whose story is being told in this paper – and her sister Basma live together in a house in a rural neighbourhood we call Chak-Ameeran. Analysis of the social and environmental factors at the rural neighbourhood and community level revealed that participants in Chak-Ameeran perceived that there were good schools (imparting quality education) with easy access for children. Bushra very enthusiastic about education, had never attended school. In comparison, her husband Basheer had completed eight years of education. At the time of data collection Bushra’s family was doing well. They owned a house where she lived with her sister Basma and kept some cattle. This had not been the case in the past when Bushra was struggling to provide her daughter with an education. The demographics for Bushra’s household are given in .

Table 1. Demographics of the participants.

To improve the quality of interpretation, the participants were asked to rephrase their responses, or to confirm or reject the interviewer’s understanding of their response, during the interview. Two versions of transcriptions one by the interviewer and the second by the research assistant were compared, and discrepancies were discussed. The final version was translated into English. Bushra’s family was selected for the newly introduced NC analysis based on her difficult past and a transformed future.

Application of the Framework

Bushra clearly articulated the value she placed on education to improve her daughter’s life and had consistently worked towards achieving this goal. This represented her refusal to be affected by an oppressive system, to achieve a more secure and prosperous future.

Applying Negative Capability to Interpret the Story of Bushra and her Sister Basma: An Exploration of how People Gain the Ability to Break out of Oppression

We feel that telling stories is about reconstructing and reconciling what is told and what is felt when stories are shared in temporal, social, and physical spaces. Therefore, going forward the first author who met these mothers will take charge and be the narrator and (re) teller of the stories. For the sake of clarity we will note where the voice of the first author, and the collective voices of both the authors appear.

First author (the interviewer): Before I begin, I want to acknowledge two things. Firstly, the power of the teller over the subject of the telling. I believe that the ways in which stories are told says a lot about who tells them. The very decisions for sequencing the events to bring the story together are also selective. I therefore make no claims about the objectivity of observed experience. On the contrary, I acknowledge that I am a source of bias not only because of the power I hold to “tell” somebody’s story but also because of who I am (my identity and experiences), what intentions I have (“collecting data”) and how I benefitted from the experience (being awarded a doctorate in a European University and being acknowledged as an academic after publishing these stories). I am very aware of the harm that a “North” educated researcher may bring to such contexts regardless of their good intentions and have cautioned against it elsewhere. I also acknowledge the fallacies that we (as researchers) bring with us through the education that we receive in parts of the world where diverse ways of knowing are very rarely recognised. Elsewhere I have argued for a self-critical reflexivity in which we make ourselves conscious as researchers, and the inadequacy of our own knowledge to make sense of the world of knowledge we gain access to through our interactions (Khalid Citation2022). I approach these stories acutely aware of my biases and fallacies and make no claims on “truth”.

Secondly, I am even more mindful of what Hansen (Citation2019) calls “the Ventriloquist charge” (32). Drawing on Dingli’s Citation2015 work, she argues that in search to “give” voice one becomes a ventriloquist by imposing their thought frames onto the subject. I find intentions of giving “voice” problematic. I do, however, take pride in identifying myself with the mothers I interviewed, not only by virtue of being born and raised in the same country as them but also as a woman and a mother just like them navigating a gendered world. As much as I wish to, I understand that I can only dream of being a semblance of an insider regardless of my intentions (Khalid Citation2018). I will always be someone from bahar-mulk (“outside” country).

Both authors: In conclusion, we see limitations but also some strengths in being closer in proximity to “otherness” and therefore re-tell stories that I experienced. Coming back to the power in re-telling stories we acknowledge that this is not the only way, and perhaps for some, not even the best way of capturing such richness in written text. Again, like Hansen we invite the reader (s) to remain open to challenge what we write and how we interpret, but also attempt to connect with the protagonists of these stories as intellectual equals. With these confessions we proceed and re-construct the stories we collected in 2017

First author (the interviewer): I met Bushra on one warm summer evening in a rural neighbourhood that we call Chak-Ameeran in Sargodha in the year 2017. As I crossed their entrance gate I walked in a roof-less foyer with a hay shade on one side propped up with the help of dried tree branches. Under the shade, I saw two cows and a few goats tied to their posts munching on freshly chopped fodder. The floor was mud plastered and right across at the end were two quarters (squared rooms) built with a mix of permanent and corrosive materials like bricks, cement, and mud. The rooms had doors and a small window, just enough to allow some sunlight inside. I saw the two sisters sitting on a “Charpai” (bedstead woven with jute-rope) right outside the two rooms. Their house was modestly built but the prosperity was noticeable. They seemed very excited and keen to offer a cold beverage and some bread. Both the sisters were composed, listened intently, and spoke often.

First author (narrator): Bushra and her sister Basma had never attended school, though their brothers had. The sisters lived in the house together and were good friends and confidantes. Basma was married to Bushra’s husband’s brother – two sisters married to two brothers. There were seven children in the house, six were Bushra’s (including two daughters) and Basma had one son. Chak-Ameeran was their ancestral rural neighbourhood which had access to good schools and transportation links to the main city for higher education. Some relatives still resided in the rural neighbourhood so the sisters had plenty of support though they themselves had only moved back here a few years ago. What made their story stand out was their shared commitment to their children’s education, and their demonstrated ability to withstand difficulties to achieve this goal. Today, aspiring to study medicine and become a doctor, Bushra’s daughter Bilquis was enrolled in a college, studying science, and hoping to get admission in a medical school.

Bushra shared with me (the first author) the journey that had helped her fulfil her aspirations for her daughter Bilquis’s education to become a doctor. At the time things were difficult because Bushra lived in another rural neighbourhood with her abusive in-laws. This rural neighbourhood lacked even basic facilities like clean water, and there was just one school nearby which was rarely attended by teachers. Unfortunately, unlike Bushra, her in-laws did not see the value in education. She explained:

Actually; my husband's family despise women getting education because they think that women get married and take their income to somebody else's house, so to them there is no point of spending on daughters. My husband takes after his family and resists our efforts to have our children study.

Bushra was convinced that her daughter’s future opportunities would expand with education, so it was not something she was ready to give up so easily. She often discussed the lack of opportunities for herself and Basra, because they were uneducated: “Our father believed that daughters should not be sent to school”. Their brothers were sent to school, but this opportunity was not provided for the daughters. However, they received moral as well as financial support from their family and remained on good terms with them. Bushra’s history makes her’s an ideal story for exploring achievement under conditions of inequality, not just because of the situation that she faced as a child or mother, but also due to the historic gender inequality inherent in many traditional societies like Pakistan.

After marriage, Bushra moved in with her husband’s family, as is the norm in Pakistan. Her husband and his family were extremely harsh, and she sometimes suffered physical abuse as a result of small arguments. When Bushra’s father died she felt responsible for her sister Basma’s future. Out of concern, Bushra convinced her parents in law to bring Basma into their family by marrying her to their younger son. She thought with two sisters serving the family the environment would become safer for both. Wishing to provide her sister with a socially acceptable future, Bushra found that she had brought her into an abusive relationship. Now the abuse was directed towards Basma too. The birth of Bushra’s daughter forced them to think about the future. Though the circumstances were oppressive, Basma was able to foster a postive feeling of hopefulness (almost as if she was able to retain a sense of creativity in the midst of depravity) giving her the energy and optimism to see beyond the current dismal situation, and to hope for something better (“reimagining alternative futures”, Dejaeghere Citation2020) for her daughter.

The mothers were not the only ones who valued education; Bushra’s eldest daughter, Bilquis, was a motivated student who did well in every class that she attended. Despite the conflict that this must have created, Bushra deligently sent her children to school. The sisters saw Bilquis’s potential as a beacon of light for the other children to follow. As Bushra commented,

We believe that if my daughter pursues a successful career, all the younger siblings and cousins will follow suit … See, by giving them education we want to ensure that after we die our children are strong enough to support each other.

Bushra and Basma’s determination to have their children – particularly the girls – educated, stemmed from their belief in the transformative power of education, a capability with the potential to change Bilquis’s life. Their efforts were calculated and effective. For example, they focused on Bilquis, hoping that once she was older and mentally stronger, she would lead the way for the younger children. Bilquis came across as a bright, thoughtful, and hardworking girl. She discussed how she had always wanted to become a doctor. Bilquis’s thoughtfulness was quite visible in her attitude towards her mother. Bushra said once, “You know as I scramble to pay her [Bilquis’s] fees, my daughter keeps encouraging me that the expenditure will keep getting less as she progresses with her education”. In trying to reduce other costs so that her mother could pay for her education, Bilquis never asked for anything. Bushra said, “My daughter [Bilquis] has no other interest besides education. She has never asked for any items that girls usually fancy like clothing, jewellery etc”. This shared motivation between the mother, daughter and aunt contributed to the success they had achieved today. However, it cannot be ignored that initially, when Bushra fought to support her daughters’ education, it had required enormous personal strength to face oppression.

Bushra and Basma’s lives were constrained with curbs on their freedom, and the right to express their views. The two sisters were able to imagine alternative ways in which to achieve a treasured goal (the daughter’s education) while living in insecure conditions.

Bushra’s husband, Basheer, worked and lived in Lahore, a city some distance away, and only occasionally visited his family. These short encounters almost always ended in a brawl, in which Bushra suffered physical abuse and often Basma also got dragged into the disagreements. Basma shared a story of the time her brother-in-law (Bushra’s husband) tried to choke her. Each sister became an emotional and psychological refuge for the other.

Bushra reached her tipping point one day, when Basheer suggested that Bilquis, who was studying in a secondary school at the time, be taken out of school. He thought that it was time to stop spending money on the girl’s education, and to marry her off instead. The quote shared below captures Bushra’s commitment,

We look ahead where his [my husband’s] thoughts never reach. He planned that our daughter should be taken out from school when she completed year 10 and by that time, he will retire so will spend some money and marry her off. He does not realise that if she has a difficulty in her life, she will be at the mercy of others. There was a marriage proposal for my daughter, he wanted to accept it and be done with her responsibility. In his mind he was trying to get rid of the burden of a child, little does he know that if things go wrong, the burden only multiplies (apnay-walo-bojh-laanda-ae, ye-koinai-pata-kay-bojh-wadhda-janda). I resisted and fought against the idea. That is when my husband said that if I didn’t give in, he would no longer support financially. (Bushra)

Bushra believed it was unwise to send a young girl, with no means to support or fend for herself, into a new family. This event was the catalyst, spurring the women on to develop their capacity for action, to try and break the cycle of oppression. They found the strength to devise strategies, and negotiate with the established norms, until they found a way to reshape their lives and those of their children.

In the argument Bushra had with her husband, he made clear that he would cut off any kind of financial support for Bilquis’s education if they did not listen to him. Bushra stood firm and told Basheer that she would not let her daughters be deprived of an education. Basheer kept his word and stopped providing support for Bilquis as well as her younger sister, Seema. The importance and implications of Bushra’s decision cannot be overstated. For a woman who had lived in an abusive environment for so long, without the capacity to earn for herself, Bushra’s bold decision made the survival of her family uncertain. For her, though, the pursuit of education was worth this price. The benefits that she saw in education outweighed all the difficulties that she would have to endure. Her life thus far had been challenging, but she had at least financial security but this decision would make her life more precarious than before. However, both sisters were steadfast in their pursuit of their goal.

Fate intervened one day when the sisters had gone out to fetch fodder for the cattle. They met an old man who convinced them to buy a calf from him. When they said they did not have any money to pay him, he said they could pay him later. When the sisters brought the calf home, Basheer was furious, and told them to return it immediately. The old man refused to take the calf back so the sisters borrowed some money from a friend and paid for the animal. Since they could not take the calf back home they decided to keep it with their neighbours. The income that they had raised by the time of the interview started with this calf they’d bought on that serendipitous day.

With some income now being generated by selling dairy from their cow, the sisters began saving money. They sold the jewellery their parents had given them when they married, and soon, saved enough money to buy a plot of land in their ancestral rural neighbourhood, Chak-Ameeran. Bushra and Basma knew that moving here would bring several benefits. They would escape some of the trauma inflicted upon them regularly by their in-laws, they would need to spend less on transport because the rural neighbourhood had good state schools which were free, and they had family members, including their brothers, living in the rural neighbourhood. This meant that in times of difficulty they would have support.

Bushra and Basma sent their savings to their brothers, who bought them the land. As soon as the purchase was complete, the sisters gathered their belongings and migrated there with their children. Their in-laws and husbands spent many years approaching their rural neighbourhood elders to force the sisters to return, but when they failed they eventually accepted this decision. The move changed their lives forever, but it did not happen overnight. It was the result of careful planning, and the sisters were lucky to have the support of their other siblings. “When we moved here, we just had this piece of land. We slowly built the walls around it and then constructed these two quarters. People used to ask us, aren’t you scared? We used to laugh and say, what is there to be afraid of? Slowly and gradually as we saved enough, we kept building now we have bought a place where our children had a roof over their heads to call their own” (Bushra).

Their enthusiasm for, and faith in education, was a ray of hope in the darkest periods, and the sisters never wavered in their pursuit of a better life, and their children. These actions came with a price. They had flung themselves into uncertainty by moving out of a place they had called home for many years, where the household was run with income produced by their husbands. Now that they had moved, what lay ahead was as uncertain as their past lives, but they knew they had better support mechanisms in place (their family). When Aliya, one of the authors met the sisters Basma’s husband who had developed a disabling illness in the past years lived with the sisters peacefully and Bushra’s husband Basheer occasionally visited his children.

Bushra and Basma demonstrated a calculated, rational and informed approach to changing their situation. This included making alliances with each other, their neighbours, and finally, relying on their extended family, to achieve their aspirations. Once the immediate threat to the girls’ education was eliminated, they continued to find ways to maximise their gains. For example, Bushra asked her nephew to save his old books for Bilquis; and she sent the younger daughter, Seema, to a state school, so they could save for higher education. Bushra said “I pay for everything by taking care of cattle and earning from it. We cannot feed our children fancy food, but we feed them butter and milk”. Their relatives are also supportive and contribute when they can, but Bushra is determined to make her own way.

At the time of this interview, Bilquis was studying sciences at Year 12 in college, which is commonly known as pre-medical course in Pakistan. The admissions tests are highly competitive, and only the highest scorers gain admission to medical school. Basheer pays for his sons’ education and visits them occasionally. The sisters’ situation is better now, because their relatives live nearby and can intervene if the husbands try and physically abuse them. Overall, the women succeeded in securing a better future for themselves and their children.

Bushra and Basma’s experiences fit the three themes that we identified in the execution of NC. They lived in conditions of historical gender disadvantage and oppression. Despite this, they exposed themselves to greater physical risk, and financial uncertainty, in pursuit of a better life. They gained the capacity to look beyond their present constraints and focus on their goals. Their faith in the life-changing potential of education gave them strength in the face of adversity. It is also possible to see how agency pushed the mothers to take specific steps that culminated in their ability to gain control over their lives.

The threat to Bilquis’s education instigated them to assume a more agency-driven approach to achieve their goals, enabling them to break free from psychological, physical and financial oppression. To summarise it is noted that out of necessity people learn to shield themselves from the adversities. It almost seems like a rejection of debilitating circumstances. This sometimes leads them to develop a certain agency-driven behaviour with which they preserve their intellect and abilities.

Discussion

The capability approach has long been critiqued for paying little attention to power relations leading to a thin understanding about the struggles of marginalised groups that live in conditions of “unfreedoms”. This is especially problematic for work that seeks to transform and challenge gender disadvantage. This paper addresses this concern by providing conceptual resources to account for and explore the situations of some Pakistani mothers who live in highly gendered spaces. In this regard the paper makes three main contributions. Firstly, it situates NC within the capability literature through discussions around aspirations, agency, and structural constraints. To this end this paper agrees with a value-neutral perspective of capability and proposes NC as a value-neutral approach. Secondly, it develops an innovative analytical framework based on the present theorisations of NC. Thirdly, it provides some resources for researchers, practitioners and policy makers for a sensitised approach towards marginalised groups.

The first contribution is related to providing grounds for agent-led discussions about contexts that are reproductive of gendered inequalities. This paper aligns itself with Dejaeghere’s (Citation2020) consideration of capabilities as value neutral for redressing gendered inequalities. Informed by our own research we also stray away from a value laden approach to capabilities. For contexts characterised by unfreedoms it is possible for capabilities to be imagined as deficient in opportunities. The concept of NC supports such an understanding of value neutral perceptions. If NC is the ability to continue to seek creative pursuits in relations with education, remaining within intensely gendered terrains, then it has the potential to be seen as “negative” but generative of creativity. For furthering an agenda for achieving gender equality in education it is important to recognise contexts that are characterised by unfreedoms. It is also important to not lose track of the agency potential of people so that the people are not reduced to objects existing within oppressive structures. In such considerations the unfreedoms/negative may dominate in a capability evaluation but must remain within the ambit of social justice.

Secondly, pulling together the present theorisation of NC this work has proposed an analytical framework for evaluating people’s potential for agency in highly constrained conditions. There is a thin line that we do not wish to cross, one that proposes an unethical stance of expecting “resilience” and “resistance” from the marginalised. We do not support any such suggestions. For us the main concern is to celebrate the dignity and the struggles of people who live in and negotiate intensely unequal structures. We urge researchers, policy makers and practitioners like us to always begin with the acknowledgement that people living in oppressive conditions are not objects without agency and logic.

Based on our ethical stance we contribute to the ongoing discussions on gender and education especially the recent commitments towards girls’ education and women’s empowerment. What does it mean to seek gender justice in and through education when contexts are dynamic, even more so in times of COVID, and the agency and aspirations of women remain in a dialectic relationship with each other and the context? Our proposed framework has use for such explorations. The key purpose of this framework is to conduct a nuanced scoping exercise which is sensitive to the issue, the context, but more importantly the gendered agent of concern. There is much space for the concept to be developed further through applications in diverse contexts. We do not present this as a completed project, rather a starting point for further explorations that allow a sensitive approach to people’s struggles and their dignity and agency in the face of hardships.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aliya Khalid

Aliya Khalid has a PhD in gender, education, and development from the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. Aliya teaches on the Comparative and International Education MSc programme at the Department of Education. Her research focuses on how women in the South navigate their agency in highly constrained circumstances. Her specialised areas of interest are the capability approach, negative capability, epistemic paradoxicality and justice, and the promotion of knowledges (plural) and Southern epistemologies. Aliya actively engages in issues around the politics of representation and knowledge production in the academe.

Pauline Rose

Pauline Rose joined Cambridge University in February 2014 as Professor of International Education, where she is Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre in the Faculty of Education. Prior to joining Cambridge, Pauline was Director of UNESCO’s Education for All Global Monitoring Report. Pauline’s research focuses on issues that examine educational policy and practice, including in relation to inequality, financing and governance, and the role of international aid. She has worked on large collaborative research programmes with teams in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia examining these topics.

References

- Ali, Forkan. 2018. “The Dynamics of Islamic Ideology with Regard to Gender and Women’s Education in South Asia.” Asian Studies 6 (1): 33–52.

- Andrabi, Tahir, Jishnu Das, and Asim Khwaja Ijaz. 2012. “What Did You Do All Day? Maternal Education and Child Outcomes.” Journal of Human Resources 47 (4): 873–912. http://economics-files.pomona.edu/andrabi/research/MotherChildJHRresubmitNov11.pdf.

- Andrabi, Tahir, Jishnu Das, and Asim Ijaz Khwaja. 2008. “A Dime a Day: The Possibilities and Limits of Private Schooling in Pakistan.” Comparative Education Review 52 (3): 329–355. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/588796.

- Anwar, Behzad, Muhammad Shoaib, and Saba Javed. 2013. “Women’s Autonomy and Their Role in Decision Making at Household Level: A Case of Rural Sialkot, Pakistan.” World Applied Sciences Journal 23 (1): 129–136.

- Ashraf, A. 2016. “‘Parental Aspirations and Schooling Investment: A Case of Rural.” Pakistan Journal of Applied Economics 26 (2): 129–152.

- Ashraf, D., and Iffat F. 2007.“Education and Women’s Empowerment: Re-Examining the Relationship.” Education, Gender And Empowerment: Perspectives from South Asia, 15–31. http://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_ied_pdck/97

- Bano, Masooda, and Emi Ferra. 2018. “Family Versus School Effect on Individual Religiosity: Evidence from Pakistan.” International Journal of Educational Development 59: 35–42.

- Bhatti, Feyza, and Roger Jeffery. 2012. “Girls’ Schooling and Transition to Marriage and Motherhood: Exploring the Pathways to Young Women’s Reproductive Agency in Pakistan.” Comparative Education 48 (2): 149–166.

- Conradie, Ina. 2013. “Can Deliberate Efforts to Realise Aspirations Increase Capabilities? A South African Case Study.” Oxford Development Studies 41 (2): 189–219.

- Critelli, F. M. 2010. “Beyond the Veil in Pakistan.” Affilia 25 (3): 236–249. doi:10.1177/0886109910375204.

- Davis, K., N. Drey, and D. Gould. 2009. “What Are Scoping Studies? A Review of the Nursing Literature.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (10): 1386–1400.

- DeJaeghere, Joan. 2018. “‘Girls’ Educational Aspirations and Agency: Imagining Alternative Futures Through Schooling in a Low-Resourced Tanzanian Community’.” Critical Studies in Education 59 (2): 237–255.

- Dejaeghere, Joan G. 2020. “Reconceptualizing Educational Capabilities: A Relational Capability Theory for Redressing Inequalities.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 21 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1080/19452829.2019.1677576.

- Dingli, Sophia. 2015. “‘We Need to Talk about Silence: Re-Examining Silence in International Relations Theory.” European Journal of International Relations 21 (4): 721–742.

- Dreze, Jean, and Geeta Gandhi Kingdon. 1999. “School Participation in Rural India.” Review of Development Economics 5 (1): 1–24.

- Duflo, Esther. 2012. “Women Empowerment and Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Literature 50 (4): 1051–1079.

- Faize, Fayyaz Ahmad, and Muhammad Arshad Dhar. 2011. “Effect of Mother’s Level of Education on Secondary Grade Science Students in Pakistan.” Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fayyaz_Faize/publication/255983607_Effect_of_Mother's_Level_of_Education_on_Secondary_Grade_Science_Students_in_Pakistan/links/0046352fd9db06586b000000/Effect-of-Mothers-Level-of-Education-on-Secondary-Grade-Science-Students-in-Pakistan.pdf.

- Guinée, Nerine. 2014. “Empowering Women Through Education: Experiences from Dalit Women in Nepal.” International Journal of Educational Development 39: 173–180.

- Gutman, Leslie Morrison, and Rodie Akerman. 2008. “Determinants of Aspirations.” Research Report 27. Institute of Education, University of London. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Leslie_Gutman/publication/265356277_Determinants_of_Aspirations/links/5704ecd408ae74a08e267236.pdf.

- Hansen, Lene. 2019. “Reconstructing the Silence/Speech Dichotomy in Feminist Security Studies.” In Rethinking Silence, Voice and Agency in Contested Gendered Terrains. New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Hart, Caroline Sarojini. 2012. Aspirations, Education and Social Justice: Applying Sen and Bourdieu. A&C Black.

- Hart, Caroline Sarojini. 2016. “How Do Aspirations Matter?” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 17 (3): 324–341.

- Hazarika, Gautam. 2001. “The Sensitivity of Primary School Enrollment to the Costs of Post-Primary Schooling in Rural Pakistan: A Gender Perspective.” Education Economics 9 (3): 237–244.

- Humala, Shaheen, and Eshya Mujahid-Mukhtar. 2002. “The Future of Gils’ Education in Pakistan: A Study on Policy Measures Abd Other Factors Determinings Girls’ Education.” Programme and Meeting Document. UNESCO.

- Hussain, S. 2020. “Bhal Suwali, Bhal Ghor: Muslim Families Pursuing Cultural Authorization in Contemporary Assam.” Gender and Education, 1–17.

- Jafar, A. 2005. “Women, Islam, and the State in Pakistan.” Gender Issues 22 (1): 35–55. doi:10.1007/s12147-005-0009-z.

- Kabeer, Naila. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment.” Development and Change 30 (3): 435–464. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00125.

- Khader, Serene J. 2009. “Adaptive Preferences and Procedural Autonomy.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 10 (2).

- Khalid, Aliya. 2018. “Gender and Education: Maternal Aspirations in a Rural Village in Pakistan.” Conference Presentation Presented at the 25th European Conference on South Asian Studies, Paris, France, July 24. https://www.ecsas2018.org/.

- Khalid, Aliya. 2022. “The Negotiations of Pakistani Mothers’ Agency with Structure: Towards a Research Practice of Hearing “Silences” as a Strategy.” Gender and Education 1–15.

- Khalid, Aliya. Forthcoming. “The Dynamism of Mothers’ Aspirations in “Contexts of Change”: The Contexting of Support for Daughters’ Education in Pakistan.” Comparative Education.

- King, Elizabeth M., and M. Anne Hill. 1997. Women’s Education in Developing Countries: Barriers, Benefits, and Policies. World Bank Publications.

- Kingdon, Geeta Gandhi. 2005. “Where Has All the Bias Gone? Detecting Gender Bias in the Intrahousehold Allocation of Educational Expenditure.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 53 (2): 409–451.

- Mahmood, Saba. 2006. “Feminist Theory, Agency, and the Liberatory Subject: Some Reflections on the Islamic Revival in Egypt.” Temenos-The Finnish Society for the Study of Religion 42 (1): 31–71.

- Malik, A. A. 2017. “Gender and Nationalism: Political Awakening of Muslim Women of the Subcontinent in the 20th Century.” Strategic Studies 37 (2): 1–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48537543.

- Malik, Samina, and Kathy Courtney. 2011. “Higher Education and Women’s Empowerment in Pakistan.” Gender and Education 23: 1. doi:10.1080/09540251003674071.

- Meraj, Muhammad, and Mahapara Sadaqat. 2016. “Gender Equality and Socio-Economic Development Through Women’s Empowerment in Pakistan.” Ritsumeikan Journal of Asia Pacific Studies (34): 124–140.

- Mukherjee, Diganta, and Saswati Das. 2008. “Role of Parental Education in Schooling and Child Labour Decision: Urban India in the Last Decade.” Social Indicators Research 89 (2): 305–322.

- Mumtaz, Khawar, and Farida Shaheed. 1987. Women of Pakistan: Two Steps Forward.

- Nakajima, Nozomi, Amer Hasan, Haeil Jung, Sally Brinkman, Menno Pradhan, and Angela Kinnell. 2019. “Investing in School Readiness: A Comparison of Different Early Childhood Education Pathways in Rural Indonesia.” International Journal of Educational Development 69: 22–38.

- Naz, Arab, Umar Daraz, Waseem Khan, Tariq Khan, Muhammad Salman, Muhammad Asghar Khan, and Muhammad Hussain. 2013. “A Paradigm Shift in Women’s Movement and Gender Reforms in Pakistan (A Historical Overview).” Global Journal of Human-Social Science Sociology Research 13 (1): 21–26.

- Noureen, Ghazala. 2015. “‘Education as a Prerequisite to Women’s Empowerment in Pakistan’. Routledge.” Women’s Studies 1 (44), doi:10.1080/00497878.2014.971215.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2016. “Introduction: Aspiration and the Capabilities List.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 17 (3): 301–308. doi:10.1080/19452829.2016.1200789.

- Rehman, Sumaira, and Muhammad Azam Roomi. 2012. “Gender and Work-Life Balance: A Phenomenological Study of Women Entrepreneurs in Pakistan.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 19 (2): 209–228.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2005. “The Capability Approach: A Theoretical Survey.” Journal of Human Development 6 (1): 93–117. doi:10.1080/146498805200034266.

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Commodities and Capabilities: Amartya Sen. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Seshie-Nasser, Hellen A., and Abena D. Oduro. 2016. “Delayed Primary School Enrolment among Boys and Girls in Ghana.” International Journal of Educational Development 49 (July): 107–114. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.12.004.

- Shoaib, Muhammad, Yasir Saeed, and Shahid Nawaz Cheema. 2012. “Education and Women’s Empowerment at Household Level: A Case Study of Women in Rural Chiniot, Pakistan.” Academic Research International 2 (1): 519.

- Unterhalter, Elaine. 2017. “Negative Capability, Island Prisons, Education and Hope.” Paper presented at the Human Development and Capabilities Association Conference, Cape Town.

- Unterhalter, E. S. 2018. “Equity Against the Odds: Three Stories of Island Prisons, Education and Hope.” In . Brill| Sense.

- Unterhalter, Elaine, and Ina Conradie. 2019. “Agency, Structure, Freedoms and Negative Capability: Reflections on Understanding Conditions of Possibility in Higher Education in Four African Countries.” Presented at the HDCA Conference 2019, London.

- Warrington, Molly, and Susan Kiragu. 2012. ““It Makes More Sense to Educate a Boy”: Girls “Against the Odds” in Kajiado, Kenya.” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (2): 301–309.