?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Access to improved toilets can enhance physical and mental security among women. Therefore, it becomes critical to incorporate and understand their decisions on household toilet construction. Using survey data from 2528 households across urban slums, peri-urban and rural areas from the state of Bihar in India, we study two particularly relevant aspects surrounding women's decision making in sanitation. First, we examine if exclusive usage of toilets is systematically higher when the decision of its construction is taken solely by a woman. Secondly, we assess the potential household-level factors associated with women-led decision making. The findings, after accounting for the unobserved heterogeneity surrounding the selection of households with toilets, indicate a statistically insignificant increase in the likelihood of its exclusive usage in households where decision of its construction had been solely led by women. When we look at the settlement types individually, this relationship is found to be significant in the peri-urban areas. Additionally, among households with toilets, poorer women are more likely to take sole decisions about its construction. This, we argue is potentially because of sanitation interventions over the years that have been relatively successful in motivating poor women to influence toilet construction.

Introduction

One of the key indicators of women's empowerment and agency is their ability to make strategic decisions within their household as well as outside it (Kabeer Citation2001; Ibrahim and Alkire Citation2007; Sharaunga, Citation2019). These are commonly known as the instrumental empowerment indicators and are largely means to attain enhancement in an individual's or a group of individual's ability to make effective choices and then transform them into desirable outcomes (Petesch, Smulovitz, and Walton Citation2005; Alsop, Bertelsen, and Holland Citation2006). As discussed in Malapit et al. (Citation2019), a set of indicators pertaining to instrumental empowerment include those related to women's freedom of movement, financial autonomy, and the ability to make household decisions. Among these, women making toilet construction decisions within the household remain relevant in the sanitation domain. This becomes especially important in settings where resources are scarce and the returns to having access to toilets among women are disproportionately high.

Literature indicates inadequate access to sanitation systematically affects women to a greater extent due to loss of safety, privacy, psychosocial stress, and adverse health impacts such as premature birth and urinary tract infection symptoms (Baker et al. Citation2017; Baker et al. Citation2018; Sclar et al. Citation2018; Kuang et al. Citation2020). Studies have highlighted its impact on women and young girls, who are unable to use public sanitation facilities freely, and thereby the consequent reproductive health risks, poor menstrual hygiene management, harassment, and risk of violence (Caruso et al. Citation2017; Mahon and Fernandes Citation2010; Sahoo et al. Citation2015). In addition, these can be further complicated by individual-level factors, context-specific gender norms, and caste inequalities (Hirve et al. Citation2015; Sclar et al. Citation2018). Women's role in sanitation also extends to their gendered household caregiving roles in maintaining a clean toilet, taking care of children and disposal of child faeces, as well as taking care of older household members (Ray Citation2007; Sahoo et al. Citation2015). Therefore, overall benefits of having access to a toilet for a woman may be higher relative to the male counterparts within the households. This is especially relevant to low and lower-middle income countries like India which scores low in terms of gender parity.Footnote1

The problem of poor access to toilets and household sanitation in India is massive. In 2015, about 60% of the world's population, who openly defecate, were estimated to be residents of India (WHO/UNICEF, Citation2014). Further, existing literature has pointed out that poor access to sanitation contributes to enteric diseases, soil-transmitted helminths, poor cognitive growth in children, and adverse wellbeing (Saleem, Burdett, and Heaslip Citation2019; Strunz et al. Citation2014). National sanitation promotion programmes, the most recent of which was the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan led a wide range of behaviour change interventions and subsidies to encourage toilet construction and later toilet usage.Footnote2 These intervention activities aimed to increase the access to sanitation markets and lower the cost of toilet construction through targeted subsidies as well as enhance usage. Nevertheless, while an increase in access to toilets in India has been documented, concerns remain about its exclusive usage (Bicchieri et al. Citation2018; Coffey, Spears, and Vyas Citation2017; Coffey and Spears Citation2017). Notably, these studies indicate that due to a considerable proportion of households without toilets, a high prevalence of women continues to defecate in the open.

Despite disproportionately higher returns of toilet construction among females coupled with lower access of households to toilets in India, a limited number of studies have formally investigated aspects related to women taking decisions of household toilet construction. One study by Routray et al. (Citation2017) discussed qualitative insights into the barriers of women's participation in sanitation decision making. However, they do not assess determinants of female-led decisions on household toilet construction and its variation across types of geographic settlements. In this paper, using data from 2528 households across three settlements (urban slums, peri-urban and rural areas) of Bihar, we aimed to study two aspects pertaining to women decision making in sanitation. First, we examined if exclusive toilet usage for defection is higher when the decision of its installation is taken solely by a woman. Secondly, we assessed the individual and household level factors that predict women decision making in household toilet construction.

There are several justifications of our research aim. Firstly, Bihar is among the poorest states in India and lags massively in terms of health outcomes, gender equality and access to improved sanitation. This allows us to better investigate the determinants of toilet construction decisions by women regarding policy implications in low-income or underdeveloped settings, where economic constraints for private investments in toilets are high. Secondly, we study the association of household-level factors on women's decision making across different settlements to include a large variation in socio-economic characteristics. In terms of policy implications, this study will specifically help inform considerations for targeting of gendered interventions across different types of settlements to improve sanitation access and curb open defecation.

Methods

Study Site, Sampling and Data Collection

We use primary survey data administered as a part of the Longitudinal Evaluation of Network and Norms Study (LENNS) conducted in Bihar from April to June 2018 (Bicchieri et al. Citation2018). The sample was stratified into three types of administrative settlements: rural, peri-urban, and notified slums in urban areas in accordance with the Census of India, 2011.Footnote3

For the rural sample, we randomly selected one district from three broadly divided regions of Bihar: East, Middle and West. These regions were purposively chosen as socio-cultural environments with respect to variations in language and general societal practices might vary across them. The chosen districts from these three regions are Purnia, Munger and Paschim Champaran. One community development block is then randomly selected from the list of blocks in each selected district. Within this block, one Gram Panchayat (GP) was chosen at random, and another GP was systematically chosen, matched on socio-economic characteristics that include population size and proportion of individuals in Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe groups, illiterate individuals, agricultural labourers, and households with toilets based on the 2011 Census.

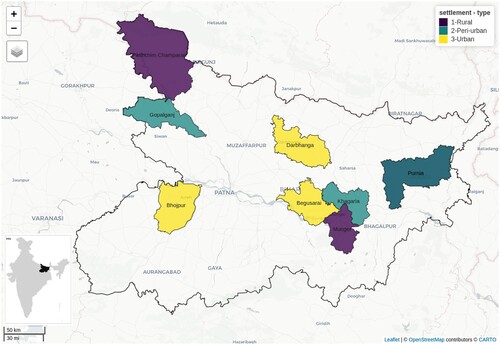

Similarly, for the peri-urban sample, we randomly selected three districts from each of these three regions (Purnia, Khagaria and Gopalganj). One peri-urban town called the Nagar Panchayats (NP) from each district was chosen at random and then another systematically matched NP was chosen from that same district.Footnote4 From the selected NPs, three census wards, which are subdivisions within the NP, were randomly chosen and surveyed. For the sample of urban slums, one Municipal Corporation (MC) was selected randomly from each of the three regions. The surveyed MCs include Arra (from Bhojpur district), Begusarai and Darbhanga. From the chosen MCs, two notified slums, defined as all notified areas in a town or city classified as “Slum” by a government authority, were chosen randomly. Of note is the fact that this survey does not include individuals living in non-notified slums and therefore this should be counted as an important limitation of our study. The location of the districts where we conducted the survey is presented in . A complete listing of dwelling units/households in the selected areas was conducted prior to the selection of individuals.

Figure 1. Location of the districts within Bihar where the survey was conducted.

Note: The state of Bihar with the surveyed districts is shown in the figure. The settlement types surveyed from each of the district is indicated using different colours.

The Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) consist of the GPs from rural areas, the census wards from the peri-urban areas and the slums from the urban areas. Within each of these selected PSUs, we randomly selected individuals from the list of all eligible individuals that include all members in the age group 16–65 years from each household within the PSUs. This selected individual is the respondent of our survey.

Field workers collected cross-sectional data in selected rural, peri-urban and urban slum sampling units from April to June 2018. The survey was translated into local language (Hindi) by a group of bilingual researchers and back-translated to English to ensure its validity. We conducted training sessions for the surveyors to ensure the standardised survey collection procedure. During the household visit, field workers first obtained oral consents prior to the survey administration. The data was collected by Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) on hand-held tablets. Anonymity was ensured by deleting the names recorded during data collection and conducting the analysis using individual and household unique identification numbers.

We collected data on toilet access within the household and its usage among the household members from the respondent. In addition, for households with a private toilet, we gathered information on who within the household led the decisions regarding the construction of the toilet. We also collected information on various individual level and household level characteristics, and perceived social norms and community sanctions on issues surrounding sanitation.

Variables

There are two objectives of the paper: (i) examine if exclusive toilet usage is higher in households where the decision to construct the toilet was taken by a women member; (ii) assess the individual and household level correlates associated with women decision making related to construction of household toilets. To address these objectives, we used the following variables:

Examining Exclusive Toilet Usage

The outcome variable is whether the respondent uses the household toilet exclusively for the purpose of defecation. To create this variable, we use the following question: “In the past week, how often have you used a toilet to defecate?” The responses were recorded as: never; occasionally, frequently and always. A binary outcome variable is generated, which takes the value of 1 if the response is “always” and 0 otherwise.

The main variable of interest is whether the decision of toilet construction within the household has been solely taken by a woman or not. We asked the respondent “Who in your household got the family to build a toilet?” Notably, this decision making did not merely involve those overseeing the construction or deciding the location of the toilet but rather taking the financial decision of construction of toilet within the household.Footnote5,Footnote6 The answer options included male, female, mutual decision. We coded women solely participating in household sanitation decisions as a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if the response is female (sole decision) and 0 if it is male/mutual (joint decision). Literature indicates that treating sole and joint decision making together may not appropriately reflect the true female autonomy and joint decision making does not always imply both genders had equal say in the final decisions (Seymour and Peterman Citation2018; Acosta et al. Citation2020). As these studies acknowledge, this becomes particularly relevant in our study context (the state of Bihar) which has a large gender equality gap.Footnote7 Accordingly, we group sole female decision making as a separately category though we also examine the three categories (male, mutual/joint, female decision making) separately later in the paper.

The following covariates are used:Footnote8

Individual characteristics: Since our outcome variable is exclusive toilet usage of the respondent, we include respondent level characteristics that may be correlated with the defecation behaviour such as age and gender (Coffey and Spears Citation2017). Other individual attributes that include occupation, education and marital status dummy have been incorporated as independent variables in the model.Footnote9

Caste/Religion: In our survey, self-reported data on the sociocultural groups that the households self-identified with (religion and social caste groups) were collected. Studies have indicated religion and caste are important determinants of toilet usage. For example, toilet usage is found to be higher among Indian Muslims (Geruso and Spears Citation2018). Similarly, it is also found that barriers to toilet usage are largely linked to purity notions entrenched in caste (Coffey and Spears Citation2017).

Socio-economic status: Studies have indicated that household socio-economic status (SES) is a strong predictor of toilet usage (Bicchieri et al. Citation2017). Accordingly, we utilise data collected on possession of assets which is in accordance with what the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) conducted by the Government of India collects.Footnote10 Our analysis indicates substantial discriminatory variation in the possession of only four assets: colour television (44%), internet (27%), motorised two-wheeler (22%) and refrigerator (11%). Other relevant indicators such as owning a computer or laptop (3%), a car (0.8%) or owned an air-conditioner/cooler (1.3%) have not been included. Hence, we consider possession of these four assets to categorise household SES into three groups (low, medium and high). Low SES households own none of these assets, medium SES households own at least one of these four assets and those in high SES own at least two among these. Additionally, we incorporate whether the corresponding household owns a Below Poverty Line (BPL)/Antodaya card or not. Households possessing this card are likely to be the poorest ones and can potentially receive financial support from the state.Footnote11

Factors Related to Women’s Participation in Household Sanitation Decision Making

The outcome variable for this part of the analysis is whether the decision of toilet construction within the household has been solely taken by a woman or not as defined earlier. The factors we study are the following:

Socio-economic status: Since the outcome variable is defined at the household level, we only consider household characteristics. It is possible that women from households with higher socio-economic status may take more financial decisions within households because of lesser economic constraints. Therefore, we include the SES variables in the regression model.

Caste/Religion: Caste and religion are closely related to restrictive cultural and religious norms that influence women's ability to take financial decisions (Borooah and Iyer Citation2005).

Women's autonomy proxy: Studies support that women's education and employment status are associated with their ability to take decisions (Routray et al. Citation2017). Therefore, we constructed household level measures as women's autonomy proxy. These include having at least one adult woman (≥18 years old) with high secondary education in households and having at least one adult woman with earnings. Those two variables were both coded as dummy variables.

Other variables: In our survey, we collected information on the gender, age, education level, occupation and marital status of all the household members. We use these variables to construct other household level measures. Because studies have indicated that women are more responsive to the children's needs within the household, we include the number of children aged between 0 and 14 years within the household (Duflo Citation2012; Singh, Gaurav, and Das Citation2013). Further, number of young and middle-aged women aged between 14 and 45 years old is incorporated in the model since women in this age group are more likely to make decisions about building a household toilet. Further, we include the number of married females within the household along with the household size. In addition, in both the regression models, we introduce fixed effects for geographical settlement (rural, peri-urban and urban) and PSU to capture the heterogeneity across these levels.

Analysis

To answer both the research questions raised in this paper, we should consider only households with access to a toilet. This is because women making toilet construction decisions and family members’ exclusive toilet usage are conditioned only on whether the household ever constructed one. However, only assessing outcomes in households/individuals with access to toilets would lead to the classic case of “sample selection bias” (Heckman Citation1979). This is because a set of unobserved factors can be correlated with both: women making sanitary decisions and access to a toilet. This would also be true for exclusive toilet usage and toilet access. For instance, a household with motivated and knowledgeable women may have a higher likelihood of having access to toilets even after controlling for all other observable factors like education or economic characteristics. Accordingly, it is possible that the decision of toilet construction in this household may have come from these women in the household. Household members under the influence of these women may be more likely to use a toilet than others. If these unobservable characteristics (for example, motivation and knowledge in this case) are not controlled for, naïve logistic/probit regressions may yield biased estimates. To account for this endogeneity led by sample selection bias, we use the Heckman two-stage estimation procedure or a bivariate probit regression model with sample selection. Here, the probability of women taking sole toilet construction decisions and then exclusive toilet usage of the respondents is estimated by fitting a probit regression model with selection by maximum likelihood. The model is formulated in terms of two equations: firstly a selection regression, which is a probit regression (dependent variable: binary in nature that takes the value of 1 if the household has access to a toilet; 0 otherwise) to explain whether the household has access to a toilet and secondly an outcome probit regression to explain whether the women in the household took the sole decision of construction of the toilet in the first case and exclusive usage for defection in the second case.

More formally, the probit model to estimate the likelihood of households having access to a toilet (selection equation) is given by:

Here

denotes access to a toilet for household,

which takes the value of 1 if the household owns a toilet and 0 otherwise.

is the vector of explanatory variables that are correlated with the likelihood of household,

owning a toilet.

is the parameter to be estimated and

is the error term.

The probit model to estimate the likelihood of women making toilet construction decision solely or respondent exclusively using a toilet for defecation assume that there exists an underlying relationship through the following outcome equations respectively:

and

Here

and

represent women decision making in terms of toilet construction in household,

and whether individual,

uses the toilet exclusively for the purpose of defecation. The vector,

are the independent variables that affect the probability of women making sole decisions on toilet construction in household,

. The vector,

are the independent variables for individual,

affecting its probability of exclusive toilet usage.

and

are the coefficients and

and

represent the error terms. Please note that

,

,

;

and

where

represents the standard normal distribution.

Also, note that and

are observed only if

. If

, standard probit regression estimates with only households/respondents who have access to a toilet would yield biased results. The Heckman probit model that adjusts for sample selection would then provide consistent and asymptotically efficient estimates for all the parameters in the model. This Heckman selection regression modelling was conducted in STATA 16 with the heckprob command. Importantly, this framework has been used to study a range of different issues in varied contexts (Rubb Citation2014; Das Citation2015).

These two-step selection models require the exclusion of at least one among the independent variables used in the selection regression for estimation of the outcome equation (Cameron and Trivedi Citation2005). The model would then otherwise be identified by the functional form and the coefficients would have no structural interpretations. Therefore, this exclusion restriction demands one or multiple variables which are correlated with households having access to a toilet to be included in the selection regression, but not feature in the outcome regression. They should not directly influence the women's toilet construction decision or individual toilet usage, conditional on whether the household owns one.

Accordingly, we incorporate three exclusion variables (all binary variables) for estimating the selection equation, which are not incorporated in the outcome regression model: whether there is a separate kitchen in the household, whether the household is fully cemented and whether the household members have to travel outside the household premise for collecting water. We argue these three variables would be highly correlated with the likelihood of households having access to a toilet. Studies have shown that water availability is one of the key considerations in constructing a toilet in the household (Fry, Mihelcic, and Watkins Citation2008). Qualitative interviews conducted prior to this survey also indicated that water availability to clean and maintain toilets were among the primary concerns for households before constructing toilets. The respondents argued that they did not have water connection to their households and had to travel some distance and spend time to collect water for the purpose of drinking, washing and cooking. With a toilet inside the household, a significant part of that collected water would be “wasted” during the toilet usage.

Having a separate kitchen in the household, which indicates adequate space, can also be highly associated with the decision to construct a toilet within the household premise. As indicated across literature in the Indian context, having latrines close to the kitchen in the household may exacerbate concerns related to purity (Coffey and Spears Citation2017). However, a separate kitchen may also indicate that there is enough space within the household that can accommodate a toilet within the household premise. Hence even after controlling for household SES, the secular association of having separate toilets with household access to toilets is likely to be significant. Similarly, cemented households may have enough space to accommodate a toilet and hence it is highly likely that these households would have a toilet inside. Therefore, cemented households are more likely to have access to a toilet.

These factors are not likely to influence the error terms in the outcome equation; that is the unexplained part of whether a woman takes a sole decision on household construction of toilets. In our regression model, we control for SES through possession of assets and possession of BPL and Antodaya cards along with socio-religious groups, which as well are likely to be correlated with economic characteristics of the household. To the extent we control for these characteristics, conditional correlation of these variables with a woman led decision making is likely to be insignificant among households with toilet access. However, when we consider exclusive toilet usage, water scarcity (proxied by not having water supply within the household premise) might discourage toilet usage even if the household owns one. Therefore, it is likely that having access to water supply is positively correlated with exclusive usage of toilets for defecation. Hence for this part of the estimation, we take only the first two as exclusion variables: having a separate kitchen in the household and residing in a cemented household and argue that these variables are not likely to be correlated with error terms in the outcome equation conditional on whether the households have access to toilets.

We present the regressions for a full sample of respondents that indicate average conditional correlation across those taken from all the three geographical/administrative units: urban slums, peri-urban and rural areas. Studies have shown a high level of rural-urban divide across dimensions including socio-economic, culture, education and health among others (Jain Citation2005; Hnatkovska and Lahiri Citation2014). Further, in terms of the landscape as well, urban slums and peri-urban areas differ. While urban slums come under the jurisdiction of the Municipal Corporations, peri-urban and rural areas come under the Nagar Panchayat and Gram Panchayat offices, respectively. All these three bodies are governed by different sets of rules and protocols and interventions including those pertaining to behavioural change are often decentralised catering to the local needs and variations. We repeat the regression for each settlement type to understand the heterogeneous correlations at the administrative/geographical units that remains pertinent for decentralised policy prescriptions and understanding.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

The demographic characteristics of the respondents and the characteristics of their households are described in . The average age of sampled respondents is 35 years. Among them, 49% are Hindus and belong to the upper caste category. About 18% have received higher secondary education or above. 56% of the respondents are from households that possess either a BPL or Antodaya card. As one would expect, these varied across the administrative units. For example, the proportion of low SES households is highest in rural areas (63%), followed by peri-urban areas (44%) and then urban slums (42%). The proportion of respondents without formal or below primary education is also high in rural areas (55%).

Table 1. Characteristics of study population in urban slum, peri-urban and urban areas, Bihar, 2018.

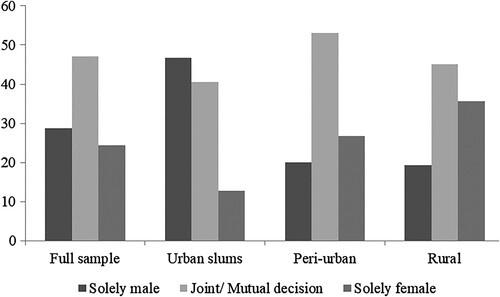

Among 1395 respondents who own a toilet (urban slum n = 473, peri-urban n = 586, rural n = 336), about 23.5% reported that women household members took the sole lead in the toilet construction decision. In peri-urban and rural areas, 26% and 35% of the household toilets constructions decision are solely made by women, respectively (). Comparatively, in urban slums, which are economically better off on average, only 12% of the toilet construction decision is solely taken up by a female.

Figure 2. Decision makers of getting a household toilet built by settlement types, Bihar, 2018.

Notes: The figure shows the proportion of toilets whose decision of construction have been taken either by men/mutually or solely by women. The break-down of decision making by solely males and mutual is given in Appendix Figure A1.

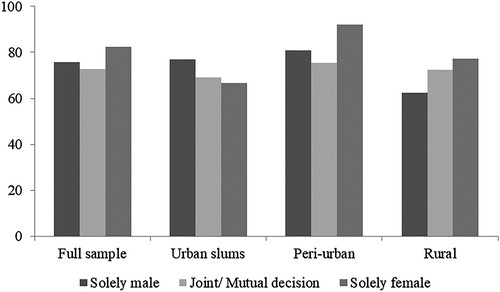

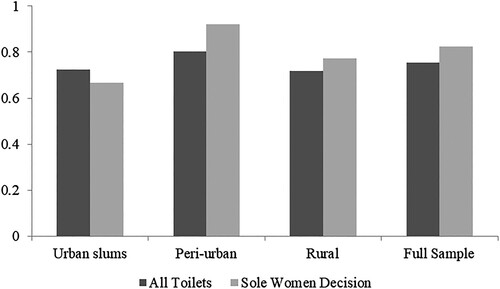

presents the proportion of respondents reporting exclusive toilet usage for defecation in the past week prior to the survey across the three administrative units among those who have access to a toilet. We also report this proportion for households where the toilet construction decision has been taken by a woman solely. We find reported exclusive usage of toilets, which were constructed by women, is higher by close to 7 percentage points than that for the full sample of toilets. This is found to be true in peri-urban and rural areas, where exclusive usage of toilets constructed solely by women is close to 12 and 5.4 percentage points higher respectively than that for all the toilets in that settlement.

Figure 3. Reported exclusive toilet usage in the past week across administrative types, Bihar.

Notes: The figure above shows the proportion of respondents reporting exclusive usage of all toilets and then of toilets whose decision of construction was solely taken by a woman. The breakdown of exclusive toilet usage of toilets whose decision is taken by solely male, solely female and mutually across the three administrative types is given in Appendix Figure A2.

Association with Exclusive Usage

We first assess if the chances of exclusive usage are systematically higher for those toilets whose construction decision has been solely taken by a woman in the household. The estimates from a simple probit regression for households with a toilet along with that from the Heckman sample selection model account for selection bias are shown in . Here, we also present the regression estimates from the selection model. The exclusion variables are found to be statistically significant in the selection regression at the 1% level. This implies cemented houses and those with separate kitchens inside the household are significantly more likely to have access to a toilet. This ensures a high association of the exclusion variables with the likelihood of households owning toilets, which as mentioned, is the key condition for using Heckman models. The Wald test that examines if the correlation between the error terms from the outcome and selection equation is statistically significant at 1% level indicates that the two equations are not independent. This implies that the regression estimates from the simple probit regression, taking only the sub-sample of households with access to toilets would yield biased estimates. Nevertheless, we report the estimations from these naive probit models.

Table 2. Estimates of exclusive usage of toilets.

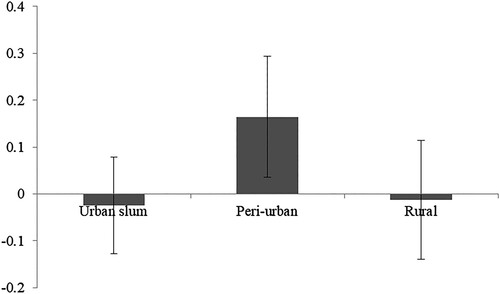

The main results indicate no statistically significant association between exclusive toilet usage and women taking sole decisions on its construction. This is consistent with the inference from simple probit regressions. The marginal effects from the outcome regression of the Heckman model separately for respondents from urban slums, peri-urban and rural areas are given in . The insignificant relationship holds for respondents from urban slums or rural areas. However, for peri-urban areas, we find a positive and statistically significant relationship. In terms of the effect size, toilets whose decision of construction within the household premises had been taken solely by a woman are 16.4 percentage points more likely on average to be used exclusively for defecation purpose. Therefore, we argue having women take sanitation decisions not only has implications on their empowerment but also can potentially lead to higher toilet usage especially in peri-urban areas.

Figure 4. Probability of exclusive usage of toilets by settlements, Bihar India, 2018.

Note: The marginal effects along with the 95% Confidence Intervals from heckprob regressions are plotted for each type of settlements.

As mentioned, in our analysis, we consider sole female decision making and do not include joint or mutual decision making as it is not clear as to how much role did the female had in the decision. Accordingly, we combined it with sole decision making by men and compared this category with that by females solely. However, we now separate the respondents who reported joint decision making about toilet construction and those who reported sole decision making by male members in the household about toilet construction. Next, we compare the probability of exclusive toilet usage in these two categories of toilets relative to those whose construction decision has been solely taken by a female. Appendix presents the associated marginal effects from the probit regression, which gives similar findings. In peri-urban areas, significantly lower toilet usage is observed for those whose construction decision has been reported to be taken solely by males and jointly by males and females when compared to the women-led constructed household toilets.

Determinants of Women-led Decision Making

Following observed some gains of women-led decision on toilet construction, we now discuss its correlates. presents the marginal effects from the outcome regression of the Heckman model for the full sample of respondents as well as separately for the administrative/geographic units. For the full sample, we find that in economically poor households, women were more likely to take sole decisions on their construction.Footnote12 We find close to 8 percentage points increase in the likelihood of women making decisions about construction of the toilet that the household owns among those who possess a BPL/Antodaya card. While we did not find significant association of economic status in urban slums, this effect size is found to be significant and close to 7.5 percentage points for those from peri-urban and more than 17.6 percentage points for those from rural areas. Controlling for other potential confounders, we also observe a 13.3 percentage point drop for households in the highest SES category as compared to the poorest category. This effect is found to be the strongest in rural areas. Notably, we find similar findings have been found by Routray et al. (Citation2017) as well where they document that women participation in household toilet installation is systematically higher among families with lower income in rural coastal areas in the state of Orissa.

Table 3. Determinants of women-led toilet construction decision (Heckman model).

Next, we assess the determinants of the variable which captures toilet construction decision as follows: 0 if the decision making is solely taken by men; 1 if it is taken jointly with women in the household and 2 if women took sole decision about its construction. Since it is ordinal in nature that indicates the extent of female autonomy in decision making about toilet construction, we employ an ordered probit regression with sample selection. The results are shown in Appendix . The main finding remains similar as presented in : the decision to construct a toilet in a poor household in rural area is more likely to be taken by a female. In peri-urban areas, as well, we observe that the construction decision of toilets in economically deprived households is more likely to be taken by females though the relationship is not statistically significant. This indicates that our inferences are largely robust.

Discussion

The Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the member countries of the United Nations called for “adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations” by 2030. In addition, it also aimed at ensuring “women's full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision making in political, economic and public life.” In the light of these two pertinent goals, this paper focuses on women solely making decisions regarding household toilet construction. We especially look at two issues: first, whether household toilets whose decision of installation has been solely led by a woman are more likely to be used exclusively for defecation purpose and secondly, determining the individual and household correlates that are associated with women's decision in toilet construction. We use primary survey data for 2528 respondents from across Bihar and examine these questions separately for three settlement units: urban slums, peri-urban and rural areas.

Overall, we find a modest increase in the likelihood of exclusive toilet usage where women are involved in its construction decisions, significantly more so in peri-urban areas. This suggests improved sanitation practices in households with higher autonomy among women manifested through toilet construction decisions. In addition, active roles of women in important household decisions may also augment their role in maintaining clean, functional private toilets that can impact usage among other household members. National sanitation programmes like SBM among others may have potentially engaged and empowered women to effectively participate in financial decisions relating to sanitation. Future research should consider assessing the role of women's role in financial decision making on household improvements in sanitation.

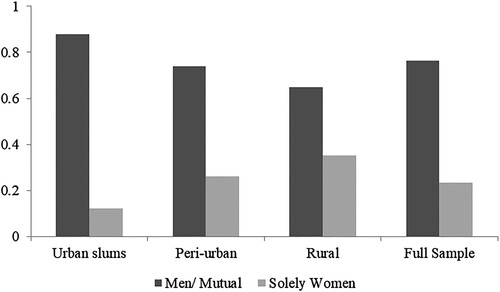

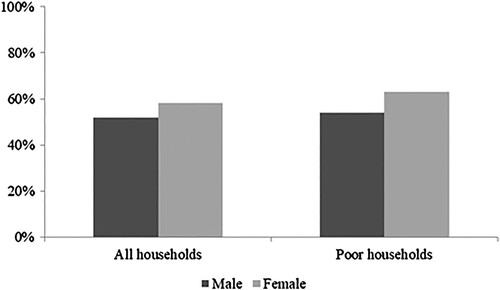

Next, we found that in poorer households with a toilet, women are more likely to take sole decision on its construction. As argued by Banerjee and Duflo (Citation2007), poorer households face significant economic constraints with respect to expenditure patterns. Under this context, this would indicate that women seem to have a higher opportunity cost of having toilets because of which they take decisions about its construction possibly putting other expenditure decisions on hold. Similar evidence is found from a previous large-scale survey in the same study region (Bicchieri et al. Citation2017). Specifically, women respondents on average were more likely to prefer spending money on construction or improving the existing toilet than men with this difference being statistically significant. Interestingly, when comparing males and females among households possessing an Antodaya or BPL card, we observe that females were even more likely to prefer spending money on toilet construction (). Anecdotes from the interviews conducted during this study indicate that women from poor households with latrines had to bargain with other members to ensure money was being spent on toilets over other assets. This appears to indicate about the higher importance women in general give to toilets. However, our inference is based on stated preference and further investigation is required to understand whether women prioritise toilet construction over other amenities by examining the household expenditure data.

Figure 5. Percentage of respondents reporting they would want to spend money on construction or improving toilets.

Note: Survey data from August to October 2017 (Bicchieri et al. Citation2017) is used. Poor households are defined as those who possess the BPL/Antodaya card.

This paper has multiple contributions. Firstly, we examine the issues separately for three settlement levels: urban slums, peri-urban and rural areas. This remains one of the main contributions of the paper as studies examining these issues on sanitation, to our knowledge, have not delved into these disaggregated levels simultaneously. Methodologically, the study can be claimed robust as we account for endogeneity that may bias the estimates. Since exclusive toilet usage and decision making on toilet construction by a woman is observable only for respondents from households with a toilet, simple binary dependent variable regressions may have given biased estimates. Using Heckman selection models, we are able to present unbiased estimates as we account for the unobserved heterogeneity due to self-selection. This remains one of the main contributions of the paper. In terms of policy, our study indicates that the government interventions on sanitation may have been successful in imbibing the need for household toilets among women. In particular, this potentially signifies the positive role of increased focus of sanitation often promulgated through behavioural change campaigns in women since the last few years through Nirmal Bharat Abhiyaan (NBA), Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (SBA) and the state level interventions through the Lohia Swachh Bihar Yojana (LSBY).Footnote13 However given the data paucity, we are unable to assess the effects of these interventions on women ability on intention of constructing toilets. We flag this as an agenda for further research.

The paper has several limitations that should be considered while interpreting the results. First, we asked participants to recall the gender of household members who involved in taking decisions about toilet construction. We use the response as the main variable of our analysis but acknowledge that this could be subject to recall bias. Second, we did not ask everyone in the household about their involvement in toilet construction decision. Therefore, we are not able to identify the specific household members who make the toilet construction decision and their family roles (for example father, mother-in-law). Further investigation is needed to reveal the dynamics within a family on sanitation and financial decision making. Next, the cross-sectional nature of our data does not allow us to make causal predictions. We limit ourselves in examining the sole decision making in toilet construction by a woman and its association with variation in toilet usage. Fourth, exclusive usage of toilets is determined through the reported toilet usage pattern in the last one week prior to the survey. Hence two measurement errors can come in: (i) the social desirability bias, where respondents can report of having used the toilet whereby in reality, he/she may not have used it and (ii) additional measurement error coming in through the definition of exclusive usage, which we measure through its usage in the past one week. It is possible that the toilet may have been used in the one week prior to the survey but in reality, respondents may engage in open defecation practices. However, since we are looking at marginal effects of decision making on toilet construction by a woman, there is no reason to believe that this measurement error would have been systematically different for respondents from households where toilet construction decision has been taken by men versus solely by women. To that extent, we argue our estimates are unbiased. Finally, it should be noted that our study is representative only in the survey areas but not for the entire state of Bihar or even the corresponding district. Nonetheless, inferences drawn from the paper should give deep insights for designing context-specific interventions.

Conclusion

In this paper, we study sole female decision making for household toilet construction across urban slums, peri-urban and rural areas of the Indian state of Bihar. The context of Bihar is important as it is among the most backward states with high levels of gender inequality. We offer two findings. We observe significantly higher usage of toilets for defecation in the peri-urban areas if the decision of its construction within the household premises has been taken solely by a woman. Overall, across all settlement types, this relationship is positive though not statistically significant. Secondly, among poor households having a toilet, women are more likely to have taken sole decisions on toilet construction in peri-urban and rural areas. This potentially underscores the importance that they put on toilets even under economic constraints. Having said this, we find that for construction of close to 69% of household toilets, the decision has been reported to be made mutually. Despite the possibility of reporting bias, we highlight the gains made not only from the perspective of gender equality but also from the efforts to ensure sanitation facilities for women. Interventions that encourage women to engage in decisions to build toilets in India may contribute to curbing open defecation practices by empowering them to motivate other household members to use toilets.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Erik Thulin, Peter McNally and Hans Peter Kohler for their suggestions and help while setting up the project along with all the respondents and the investigators of the survey work. The data collection instruments, datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available in the OSF repository [https://osf.io/rq4c3/].

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Upasak Das

Upasak Das is a Presidential Fellow of Economics of Poverty Reduction at the Global Development Institute at the University of Manchester. He is also an affiliate of the Centre for Social Norms and Behavioral Dynamics at the University of Pennsylvania. His primary research interests include Development Economics, Health, Education, Social Norms and Social Protection Programmes.

Jinyi Kuang

Jinyi Kuang is a Ph.D. student in Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, advised by Dr. Cristina Biccheri. Her research interest is in social norms, social reasoning, and women’s empowerment. She holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Maryland, College Park, and is a member of the Center for Social Norms and Behavioral Dynamics.

Sania Ashraf

Sania Ashraf is a public health researcher trained in mixed-method research with over 10 years of experience working in low and middle-income countries. Her interests include gender norms, collective and individual behaviour change, childhood infectious diseases, and cross-cutting research avenues for climate, health, and social science. She did her postdoctoral training at the University of Pennsylvania, a Ph.D. in Global Disease Control and Epidemiology from Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, MD, and a Masters in Public Health from the Emory School of Public Health, GA.

Alex Shpenev

Alex Shpenev is a data scientist with a Ph.D. in demography and sociology. His interests include social determinants of health and well-being from a cross-cultural perspective, the impact social welfare systems have on social ties, and formal demographic methods. He did his postdoctoral training and his Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania and his MA in statistics at the Wharton School. He is currently a senior data research scientist at the Center for Social Norms and Behavioral Dynamics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Cristina Bicchieri

Cristina Bicchieri is the S. J. Patterson Harvie Professor of Social Studies and Comparative Ethics at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the Founding Director of the Center for Social Norms and Behavioral Dynamics and the Master of Behavioral and Decision Sciences, and also the Director of the Philosophy, Politics & Economics Programme. Her research interests lie at the border between philosophy, game theory and psychology, focusing especially around the nature, evolution and measurement of social norms.

Notes

1 According to a report published in 2021 by World Economic Forum, India ranks 140 among 156 countries in terms of gender parity. The report can be accessed from https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2021.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2022).

2 For more information https://swachhbharatmission.gov.in/sbmcms/index.htm (accessed on 7 September 2020).

3 For more information, please visit https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-common/censusdata2011.html (accessed on 15 December 2020).

4 Since the district Khagaria has only one NP, which is Gogri Jamalpur, we choose Kharagpur NP from the nearby district to Khagaria, which is Munger.

5 Appropriate instructions were given to the surveyors to ensure that by decision making, we mean taking financial decisions regarding toilet construction within the household.

6 In qualitative research based on similar population in the study site, it is found that women generally led to demand generation and agreement within the family, whereas the men typically led the construction and technical decisions regarding toilet type, placement and costs (Ashraf et al. Citation2022).

7 In a report by Government of India (Citation2021), Bihar is among the worst performer among all states in India in terms of achieving gender equality (Goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals).

8 Since this is an individual level outcome, along with the household level factors, we also include potential individual correlates.

9 List of all the variables used along with how they are constructed have been detailed out in Appendix .

10 Please refer to http://rchiips.org/nfhs/nfhs4.shtml for more information (accessed on 10 December 2020).

11 For more information on this, visit https://dfpd.gov.in/pds-aay.htm (accessed on 6 October 2020).

12 The exclusion variables are found to be statistically significant in all the four regressions.

13 Information on NBA, SBA and LSBA can be obtained from https://jalshakti-ddws.gov.in/sites/default/files/swajal_nirmal_bharat_enewsletter_0.pdf, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/major_initiatives/swachh-bharat-abhiyan/ and http://lsba.bih.nic.in/sbmj/sbmjeevika/default.aspx, respectively (accessed on 28 September 2020).

References

- Acosta, M., M. van Wessel, S. Van Bommel, E. L. Ampaire, J. Twyman, L. Jassogne, and P. H. Feindt. 2020. “What Does It Mean to Make a ‘Joint’Decision? Unpacking Intra-Household Decision Making in Agriculture: Implications for Policy and Practice.” The Journal of Development Studies 56 (6): 1210–1229.

- Alsop, R., M. Bertelsen, and J. Holland. 2006. Empowerment in Practice: From Analysis to Implementation. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Ashraf, S., J. Kuang, U. Das, A. Shpenev, E. Thulin, and C. Bicchieri. 2022. “Social Beliefs and Women’s Role in Sanitation Decision Making in Bihar, India: An Exploratory Mixed Method Study.” PLoS One 17 (1): e0262643. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262643.

- Baker, K. K., B. Padhi, B. Torondel, P. Das, A. Dutta, K. C. Sahoo, B. Das, et al. 2017. “From Menarche to Menopause: A Population-Based Assessment of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Risk Factors for Reproductive Tract Infection Symptoms Over Life Stages in Rural Girls and Women in India.” PLoS One 12 (12): e0188234.

- Baker, K. K., W. T. Story, E. Walser-Kuntz, and M. B. Zimmerman. 2018. “Impact of Social Capital, Harassment of Women and Girls, and Water and Sanitation Access on Premature Birth and low Infant Birth Weight in India.” PLoS One 13 (10): e0205345.

- Banerjee, A. V., and E. Duflo. 2007. “The Economic Lives of the Poor.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (1): 141–168.

- Bicchieri, C., S. Ashraf, U. Das, M. Delea, H. P. Kohler, J. Kuang, P. McNally, A. Shpenev, and E. Thulin. 2017. Phase 1 Project Report. Social Networks and Norms: Sanitation in Bihar and Tamil Nadu, India. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/pennsong/16 (accessed on August 13, 2022).

- Bicchieri, C., S. Ashraf, U. Das, M. Delea, H. P. Kohler, J. Kuang, P. McNally, A. Shpenev, and E. Thulin. 2018. Phase 2 Project Report. Social Networks and Norms: Sanitation in Bihar and Tamil Nadu, India. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/pennsong/17 (accessed on August 13, 2022).

- Borooah, V. K., and S. Iyer. 2005. “Vidya, Veda, and Varna: The Influence of Religion and Caste on Education in Rural India.” The Journal of Development Studies 41 (8): 1369–1404.

- Cameron, A. C., and P. K. Trivedi. 2005. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Caruso, B. A., T. F. Clasen, C. Hadley, K. M. Yount, R. Haardörfer, M. Rout, M. Dasmohapatra, and H. L. Cooper. 2017. “Understanding and Defining Sanitation Insecurity: Women’s Gendered Experiences of Urination, Defecation and Menstruation in Rural Odisha, India.” BMJ Global Health 2(4): e000414.

- Coffey, D., and D. Spears. 2017. Where India Goes: Abandoned Toilets, Stunted Development and the Costs of Caste. New Delhi: Harper Collins.

- Coffey, D., D. Spears, and S. Vyas. 2017. “Switching to Sanitation: Understanding Latrine Adoption in a Representative Panel of Rural Indian Households.” Social Science & Medicine 188: 41–50.

- Das, U. 2015. “Does Political Activism and Affiliation Affect Allocation of Benefits in the Rural Employment Guarantee Program: Evidence from West Bengal.” India.” World Development 67: 202–217.

- Duflo, E. 2012. “Women Empowerment and Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Literature 50 (4): 1051–1079.

- Fry, L. M., J. R. Mihelcic, and D. W. Watkins. 2008. “Water and Nonwater-Related Challenges of Achieving Global Sanitation Coverage.” Environmental Science & Technology 42 (12): 4298–4304.

- Geruso, M., and D. Spears. 2018. “Neighborhood Sanitation and Infant Mortality.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10 (2): 125–162.

- Government of India. 2021. SDG India Index and Dashboard 2020-21 Partnerships in the Decade of Action. Niti Aayog and United Nations, New Delhi. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/SDG_3.0_Final_04.03.2021_Web_Spreads.pdf.

- Heckman, J. J. 1979. “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error.” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 47 (1): 153–161.

- Hirve, S., P. Lele, N. Sundaram, U. Chavan, M. Weiss, P. Steinmann, and S. Juvekar. 2015. “Psychosocial Stress Associated with Sanitation Practices: Experiences of Women in a Rural Community in India.” Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 5 (1): 115–126.

- Ibrahim, S., and S. Alkire. 2007. “Agency and Empowerment: A Proposal for Internationally Comparable Indicators.” Oxford Development Studies 35 (4): 379–403.

- Jain, S. C. 2005. Education and Socio-Economic Development: Rural Urban Divide in India and South Asia. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

- Kabeer, N. 2001. “Conflicts Over Credit: Re-Evaluating the Empowerment Potential of Loans to Women in Rural Bangladesh.” World Development 29 (1): 63–84.

- Kuang, J., S. Ashraf, A. Shpenev, M. G. Delea, U. Das, and C. Bicchieri. 2020. “Women are More Likely to Expect Social Sanctions for Open Defecation: Evidence from Tamil Nadu India.” PLoS One 15 (10): e0240477.

- Lahiri, A., and V. Hnatkovska. 2014. Structural Transformation and the Rural-Urban Divide. University of British Columbia, typescript. Society for Economic Dynamics Meeting Papers, 746. Retrieved from https://economicdynamics.org/meetpapers/2014/paper_746.pdf (accessed on August 13, 2022)

- Mahon, T., and M. Fernandes. 2010. “Menstrual Hygiene in South Asia: A Neglected Issue for WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) Programmes.” Gender & Development 18 (1): 99–113.

- Malapit, H., A. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, G. Seymour, E. M. Martinez, J. Heckert, D. Rubin, et al. 2019. “Development of the Project-Level Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (pro-WEAI).” World Development 122: 675–692.

- Petesch, P., C. Smulovitz, and M. Walton. 2005. “Evaluating Empowerment: A Framework with Cases from Latin America.” In Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, edited by Narayan-Parker D, 39–67. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Ray, I. 2007. “Women, Water, and Development.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 32: 421–449.

- Routray, P., B. Torondel, T. Clasen, and W. P. Schmidt. 2017. “Women’s Role in Sanitation Decision Making in Rural Coastal Odisha, India.” PLoS One 12 (5): e0178042.

- Rubb, S. 2014. “Factors Influencing the Likelihood of Overeducation: A Bivariate Probit with Sample Selection Framework.” Education Economics 22 (2): 181–208.

- Sahoo, K. C., K. R. Hulland, B. A. Caruso, R. Swain, M. C. Freeman, P. Panigrahi, and R. Dreibelbis. 2015. “Sanitation-related Psychosocial Stress: A Grounded Theory Study of Women Across the Life-Course in Odisha, India.” Social Science & Medicine 139: 80–89.

- Saleem, M., T. Burdett, and V. Heaslip. 2019. “Health and Social Impacts of Open Defecation on Women: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 158.

- Sclar, G. D., G. Penakalapati, B. A. Caruso, E. A. Rehfuess, J. V. Garn, K. T. Alexander, M. C. Freeman, S. Boisson, K. Medlicott, and T. Clasen. 2018. “Exploring the Relationship Between Sanitation and Mental and Social Well-Being: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Synthesis.” Social Science & Medicine 217: 121–134.

- Seymour, G., and A. Peterman. 2018. “Context and Measurement: An Analysis of the Relationship Between Intrahousehold Decision Making and Autonomy.” World Development 111: 97–112.

- Sharaunga, S., M. Mudhara, and A. Bogale. 2019. “Conceptualisation and Measurement of Women’s Empowerment Revisited.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 20 (1): 1–25.

- Singh, A., S. Gaurav, and U. Das. 2013. “Household Headship and Academic Skills of Indian Children: A Special Focus on Gender Disparities.” European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie 29 (4): 445–466.

- Strunz, E. C., D. G. Addiss, M. E. Stocks, S. Ogden, J. Utzinger, and M. C. Freeman. 2014. “Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PLoS Medicine 11 (3): e1001620.

- WHO/UNICEF. 2014. Progress on drinking water and sanitation: 2014 update. Retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/resources/progress-on-drinking-water-and-sanitation-2014-report/ (last accessed August 13, 2022).

Appendix

Table A1. Variables used in the analysis.

Table A2. Estimates of exclusive usage of toilets for toilet construction decision taken by solely men and mutually by men and women.

Table A3. Estimations of toilet construction decision (ordered heckprobit regression).