Abstract

Artists’ archives, typically a legacy trove rather than a site for public engagement, are not expected to encompass art. However, since the mid-twentieth century, factors like the ‘dematerialisation of art’, defiance against conventional art categorisations, and the prioritisation of the creative process over its outcomes, have all blurred the lines between artworks and their documentation. Consequently, a significant portion of art produced during the 1960s and 1970s still resides in archives, distributed in art objects and documents. By examining the archives of Ecart, an artistic collective that operated within the broader Fluxus network in 1970s Switzerland, this study proposes activation as an alternative strategy for caring for and securing the continuation of such art, which is often found scattered across various archival holdings. Ultimately, the research suggests activation as a way of expanding conservation beyond the exclusive domain of trained conservators, transforming it into a collective responsibility shared by diverse archive stakeholders.

Abstrakt

“Reinicjując witalność: Archiwa sztuki neoawangardowej jako miejsca jej aktywacji”

Oczekuje się, że archiwa artystów, zazwyczaj będące raczej zbiorem dokumentującym ich dorobek niż miejscem publicznego zaangażowania, nie zawierają sztuki jako takiej. Jednak od połowy XX wieku czynniki takie jak ‘dematerializacja sztuki’, sprzeciw wobec konwencjonalnych kategoryzacji sztuki i priorytetowe traktowanie procesu twórczego w stosunku do jego wyników, zatarły granice między dziełami sztuki, a ich dokumentacją. W rezultacie znaczna część prac powstałych w latach 60. i 70. nadal znajduje się w archiwach i jest rozdysponowana pomiędzy obiektami i dokumentami. Niniejsze studium, oparte na badaniach przeprowadzonych w archiwum Ecart, kolektywu artystycznego, który działał w Szwajcarii w ramach szerszej sieci Fluxus w latach siedemdziesiątych, proponuje aktywację jako alternatywną strategię opieki i gwarancję dalszego istnienie takiej sztuki, która często znajduje się rozproszona w różnych zbiorach archiwalnych. Ten artykuł postuluje aktywację jako sposób na rozszerzenie konserwacji poza wyłączną domenę wyszkolonych konserwatorów, przekształcając ją w zbiorową odpowiedzialność współdzieloną przez różnych użytkowników archiwów.

Resumen

“Infundiendo vitalidad: Los archivos de arte neo-vanguardista como lugares de activación”

No cabe esperar que los archivos de los artistas, que suelen ser un tesoro de legados más que un lugar de participación pública, incluyan arte. Sin embargo, desde mediados del siglo XX, factores como la ‘desmaterialización del arte’, el desafío a las categorizaciones artísticas convencionales y la priorización del proceso creativo sobre sus resultados, han difuminado las fronteras entre las obras de arte y su documentación. Por consiguiente, una parte significativa del arte producido durante las décadas de 1960 y 1970 aún reside en archivos, distribuida en objetos artísticos y documentos. Examinando los archivos de Ecart, un colectivo artístico que operaba dentro de la red Fluxus en la Suiza de los setenta, este estudio propone el proceso de activación como una estrategia alternativa para preservar y garantizar la continuidad de este tipo de arte, el cual a menudo se encuentra disperso entre diversos archivos. Finalmente, la investigación sugiere el proceso de activación como una forma de expandir la conservación más allá de la esfera exclusiva de los conservadores cualificados, transformándola en una responsabilidad colectiva compartida por diversas partes interesadas en los archivos.

الملخص

“غرس الحيوية: أرشيفات الفن الطليعي الجديد كمواقع للتنشيط ”

تعتبرالأرشيفات الخاصة بالفنانين، التي عادة ما تكون كنزًا للتراث عوضًا عن موقع للمشاركة العامة، و هي ليست متوقعة لتضمَّن الفن. ومع ذلك، منذ منتصف القرن العشرين، عوامل مثل 'تجريد الفن'، والتحدّي ضد التصنيفات الفنية التقليدية، وإعطاء الأولوية لعملية الإبداع على نتائجها؛ كل ذلك قد أدى إلى تشويش الحدود بين الأعمال الفنية وتوثيقها. ونتيجة لذلك، لا تزال نسبة كبيرة من الفن المنتج خلال الستينيات والسبعينيات موجودة في الأرشيفات، موزعة في أشكال الفن والوثائق. من خلال فحص أرشيفات إيكارت، وهي جماعة فنية عملت ضمن شبكة Fluxus الأوسع في سويسرا في السبعينيات. تقترح هذه الدراسة تفعيلًا كاستراتيجية بديلة لرعاية وتأمين استمرارية هذا الفن، والذي غالبًا ما يوجد منتشرًا عبر مجموعة متنوعة من مقتنيات الأرشيف. في النهاية، يقترح البحث التنشيط كوسيلة لتوسيع عملية الحفظ إلى ما هو أبعد من المجال الحصري للمرممين المدربين، وتحويله إلى مسؤولية جماعية يتقاسمها أصحاب المصلحة المتنوعين في مجالات مختلفة بالأرشيف .

Resumo

“Instilando vivacidade: Arquivos de arte neo-avant-garde como espaços de ativação”

Arquivos de artistas, tipicamente mais um tesouro herdado do que um local para envolvimento de público, não se espera que englobem arte. Entretanto, desde meados do século vinte, fatores como a ‘desmaterialização da arte’, o desafio às categorizações convencionais de arte e a priorização do processo criativo sobre seus resultados, todos têm embaçado as fronteiras entre obras de arte e a sua documentação. Consequentemente, uma porção significativa da arte produzida durante os anos sessenta e setenta ainda permanece em arquivos, distribuídos em objetos de arte e documentos. Ao examinar os arquivos do Ecart, um coletivo artístico que atuou no âmbito mais amplo da rede do Fluxus na Suíça dos anos setenta, este estudo propõe ativação como uma estratégia alternativa para cuidar e assegurar a continuidade de tal arte, que frequentemente é encontrada dispersa por vários fundos arquivísticos. Finalmente, a pesquisa sugere a ativação como uma forma de expandir a conservação além do domínio exclusivo de conservadores capacitados, transformando-a em uma responsabilidade coletiva compartilhada entre os diversos parceiros do meio arquivístico.

摘要

“注入生机:新前卫艺术档案作为激活场所”

艺术家档案通常被视为遗产的宝库,而非公众参与的场所,人们并不期望它包含艺术。然而,自二十世纪中叶以来,诸如"艺术的非物质化"、对传统艺术分类的蔑视,以及创作过程优先于创作成果等因素都在模糊艺术作品与其文献资料之间的界限。因此,上世纪六七十年代产生的艺术作品中有很大一部分仍然保存在档案中,分布在艺术品和文献资料里。本研究通过考察 Ecart(一个在 1970 年代瑞士更广泛的激浪派网络中运作的艺术团体)的档案,提出了激活作为一种替代策略,用以保护和确保此类艺术的延续,而这些作品往往散落在各种档案中。最后,研究建议将激活作为一种方式,将保护工作扩展到训练有素的保护人员的专属领域之外,将其转化为不同档案利益相关者共同承担的集体责任。

Introduction. Art in archives

Artists’ archives are essential both for understanding the artist’s oeuvre and writing art history.Footnote1 Not only do they document an artist’s practice but also provide insights into its societal, biographical and historical context. These repositories may include various materials such as preliminary drafts, notebooks, correspondence, press cuttings, receipts and invoices, as well as a diverse array of artistic tools and materials, both used and unused. This spectrum extends from paints and brushes to unrevealed film negatives, fragments of electronic equipment and gigabytes of digital remnants stemming from the creative process. In fact, artists’ archives can entail anything found in the artist’s studio except, usually, for the art itself. This deliberate omission stems from the archives’ purpose, which is not geared towards public appreciation. Instead, archives are intended to serve those with a vested interest in shaping and investigating the artist’s career, as well as preserving their legacy—a domain frequented by biographers, scholars, curators, conservators and researchers, among others.

Nevertheless, in an interesting turn of events, recent decades have witnessed a surge in the integration of archival material into exhibition spaces, fuelled by a heightened interest in the untapped potential value and use of art documents and documentation.Footnote2 These materials are employed not only to offer contextual information but, in some cases, to represent the art on display.Footnote3 Yet, there lingers a widespread belief, epitomised by prevailing collecting practices within the art world, that art should be kept away from the archival domain and live in collections.Footnote4 However, drawing a clear line between artworks and documents is not always a straightforward endeavour.

Since the mid-twentieth century, a confluence of factors, including what has been termed by Lucy Lippard and John Chandler the ‘dematerialization of art’,Footnote5 has contributed to the pervasive role of documentation as an essential component in diverse modes of artistic creation.Footnote6 These modes encompass, among others, processual, participatory, concept- and performance-based approaches. Additionally, commencing in the 1950s and reaching its apex in the 1960s, artists purposefully adopted practices that defied conventional classifications of artistic expression, merging domains of music, visual arts and performance, while simultaneously blurring the demarcations between art and life. Within this context, with the artistic process often assuming precedence over the final product,Footnote7 artists began to generate textual and visual materials closely associated with an underlying idea or event that constituted the crux of their creative endeavour. Consequently, in the legacies of artists, art collectives and art movements active during the 1960s and 1970s, any distinct separation between the artwork itself and its accompanying documentation is frequently elusive. Furthermore, the art produced during this period raises a question regarding the extent to which a document functions as a conduit for accessing an artwork or can stand as a manifestation of the artwork in its own right.

This is certainly the case with the rich legacy of Fluxus, an international network of artists that emerged in the late 1950s and at the beginning of the 1960s. As noted by conservation theorist Hanna Hölling, Fluxus art is distinguished by a ‘paradoxical coexistence of ephemerality and materiality’.Footnote8 This characteristic is best elucidated through the extensive employment of score-type instructions, which can be interpreted through performative gestures or playfully transformed into physical objects. Of particular interest in this context are what Fluxus scholar Natilee Harren refers to as ‘notational objects’, denoting objects whose form and appearance suggest performative engagement, often articulated in accompanying instructions.Footnote9 While possessing artistic value in their own right, in their ‘inactive’ state, these objects can be perceived both as documents that imply the potential for performative action or as evidence of past actions.Footnote10 Thus, while some creative practices may appear to be destined to produce conventionally understood and autonomous art works, they are actually based on techniques and traditions derived from music such as scores, composition and interpretation. Consequently, they have the potential to disrupt systems of value in the visual arts and confuse the distinction between their documentation and the artwork.

Besides more ‘traditional’ artmaking understood as the creation of objects, Fluxus’ activities included a variety of actions, events and gestures that, at the time, were not considered within the conventional boundaries of visual arts as art, per se. These activities were as diverse as organising and coordinating concerts, festivals and exhibitions that featured the work of both Fluxus and non-Fluxus artists realised by both Fluxus and non-Fluxus performers, as well as designing, publishing, promoting, distributing and networking. Notably, much of the Fluxus artists’ practice—variously classified as new music, happenings, actions and events—utilised live bodies and audience participation as primary materials. For many artists within Fluxus circles, all these endeavours were considered on an equal footing as art. Defying the notion that art must be self-contained, stable and finished, their practices often left behind only documents of various kinds, be they textual, visual or objectual.Footnote11 Not only do Fluxus’ intermedia, concept- and process-based artworks obscure the boundaries between art, documentation and archival material, but they also challenge our assumptions about what qualifies as the proper ‘site’ for art.Footnote12 In so doing, they also defy established practices associated with an artworks ‘afterlife’, such as archiving, collecting, preserving and conserving.

This article operates under the assumption that, due to its resistance to conforming to traditional collection practices,Footnote13 much of Fluxus art can be found in archives, including artist’s archives and those accumulated by collectors.Footnote14 The identities of these artworks are not confined to one or several discrete objects; instead, they are distributed spatially and materially across both art objects and documents.Footnote15 However, archives, in contrast to collections, generally lack the infrastructure and support needed to conserve artworks. Strategies within the conservation of contemporary art dedicated to works that are time-based, process-oriented, relational, participatory and include performative elements have been developed for the context of museum collections. In this setting, artworks are isolated, identified and catalogued accordingly, while in archives they exist as diverse disconnected items. An archive’s custodians rarely approach their holdings as consisting of artworks, rather concentrating primarily on preserving the documentary media as evidence of the art’s past existence.Footnote16 This approach, while undeniably necessary, remains distinctly different. Unfortunately, it often represents the extent of the capacity of the current guardians of much Fluxus art in regard to preservation. While documents and documentation evidence historical works involving performance,Footnote17 recent scholarship advocates for more active strategies that foster deeper engagement with—and transmission of—these works through repetition—staging, enactment or interpretation.Footnote18 As observed by Rebecca Schneider, within a culture that accords privilege to material objects, archives often assume the role of emphasising and subsequently regulating, sustaining and institutionalising loss.Footnote19

What is actually lost when artworks, whose identities are distributed across art objects, documents, processes and actions, are preserved only as the material evidence of their existence? Is there a way to sustain the agency of these artworks within the existing system of memory institutions when they have no alternative refuge except for the archives?

This article addresses these questions by examining the archives of Ecart, an artistic collective that operated within the broader Fluxus network in 1970s Switzerland. By scrutinising artworks encountered in the Ecart Archives, delving into the group’s artistic practices, and considering recent interactions with its legacy, the study explores the potential of ‘activation’ as a method for conserving art dispersed across archival records. The argument posits that the particularities of archival processes enable the preservation of what I call here an ‘artworks’ liveliness’—their inherent aspects that may have less room within the rigid structure of a collection, such as mutability, open-endedness, incompleteness, performativity and the ability to be performed. They could also be seen as an opportunity for us to acknowledge and embrace the gaps (in French écarts) in our understanding of what and where the artwork is.

This article draws from fieldwork conducted within the archives of a specific art collective housed at a particular museum. The unique work culture of Musée d’Art moderne et contemporain, Genève (MAMCO), along with the tightly knit local art community, shapes its idiosyncratic setting. Consequently, the scope and scale of the research presented here are constrained. Nevertheless, observations made during this specific fieldwork are complemented by the author’s broader experiences and theoretical engagements with diverse museum and archive contexts.Footnote20 The intention is to illuminate the potential for activation through a singular example, while acknowledging that further research across multiple archives would likely uncover additional complexities beyond this particular case study.

Ecart’s works, its archives, what’s left and what follows

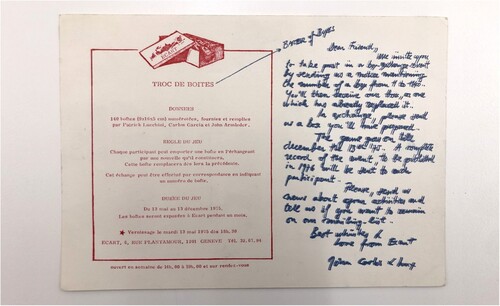

In late 1975 in the small town of Shimosuwa in Nagano province, the Japanese conceptual artist Yutaka Matsuzawa (1922–2006) received a postcard from Switzerland ( and ) which contained an invitation written in two different texts—one in French and the other in English—for an event called Troc de Boîtes, which translates as ‘barter of boxes’.Footnote21 The invitation asked for contributions for an exchange event where boxes would be swapped by participants. The English section (it is assumed here that Matsuzawa did not read French) asks the addressee of the letter to respond to the call in three steps: (1) choosing a box numbered from 1 to 140; (2) sending another box in exchange; (3) providing information about their current artistic practice; and (4) stating if they wish to remain on the mailing list. The game completion is set for the 13 December 1975 and the organisers informed participants that ‘the record’ of the project will be published the following year and sent to each of them. The postcard was signed ‘Best wishes & love from Ecart. John Carlos & Lux’.

Fig. 1 Ecart, Invitation card to Troc de Boîtes, 1975, print on paper, verso. Ecart Archives at MAMCO, Genève. © Archives Ecart, Genève.

Fig. 2 Ecart, Invitation card to Troc de Boîtes, 1975, print on paper, recto. Ecart Archives at MAMCO, Genève. © Archives Ecart, Genève.

The signatories of the postcard, John M. Armleder (1948–), Carlos Garcia (1949–) and Patrick Lux Luccini (1948–), are members of Ecart, the artistic collective active in Geneva in the 1970s. The Ecart members’ approach to art was highly influenced by Fluxus, which is evident through various characteristics that positioned the group within the broader Fluxus network. These included a critical stance towards traditional notions of authorship; a shift away from finished artworks in favour of realising artistic scores; embracing chance, indeterminacy and play; an interactive relationship with viewers; and a central focus on printed matter and multiples. The group became known predominantly as a host and organiser of events, including performance recitals and exhibitions, and as a publisher and distributor of artist books and magazines. Following the avant-garde call for integrating art into life praxis,Footnote22 Ecart rejected strict boundaries between organisational activities and collective or individual artistic practices. Like early Fluxus, Ecart deliberately chose to situate its activities outside of institutions and the market by creating their own physical and operational space. Ecart’s headquarters in Geneva functioned as a gallery, a concert venue, a bookshop, a library, a publishing house and a distribution centre for art by Ecart’s extended network. Furthermore, invested in experimenting with alternative models of distribution and dissemination, Ecart became a key node and facilitator in the international mail art network.Footnote23

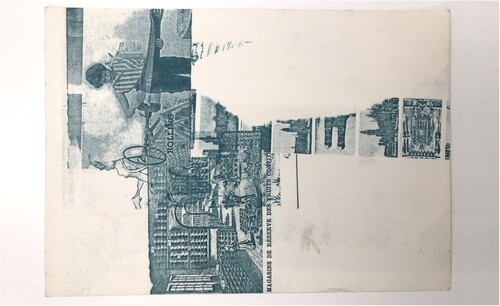

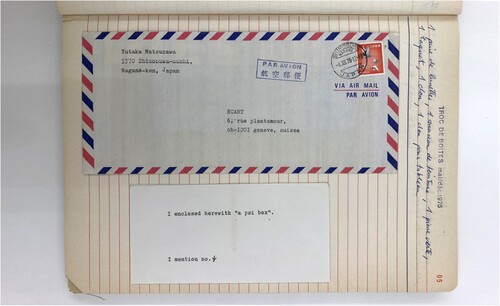

It was by means of mail art, a global trade of ideas through international postal exchange between neo-avant-garde artists that grew in popularity in the 1960s and the 1970s, that the postcard originating from Geneva found its way to Yutaka Matsuzawa. In response to the Ecart’s invitation to Troc de Boîtes, Matsuzawa sent a typewritten letter consisting of two lines of text and a signature: ‘I enclose herewith “a psi box”. I mention no. 4. Yutaka Matsuzawa’ ().Footnote24 In the Ecart Archives Matsuzawa’s letter, together with the original envelope lives between the pages of one of two elegant, red covered, lined notebooks that served Armleder to follow the correspondence and mail exchange related to Troc de Boîtes. The pages of the notebook hold a stamped heading with the title of the project, its date (mai/dec.1975), the number of the box and handwritten note listing the content of the box to be send by Ecart to Matsuzawa. According to this description, the box comprised 1 pair of glasses, 1 piece of dye, 1 green stone, 1 cleat, 1 nail and 1 picture nail.Footnote25

Fig. 3 Yutaka Matsuzawa, letter in response to Ecart’s invitation to Troc de Boîtes (1975) found between the pages of one of the notebooks which were used to trace the exchange. Ecart Archives at MAMCO, Genève. © Archives Ecart, Genève.

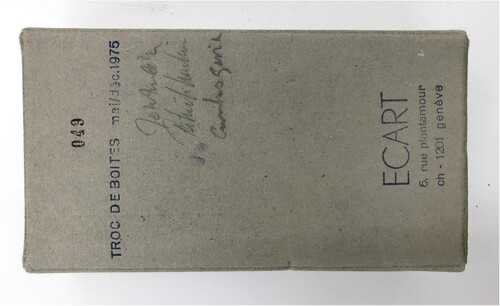

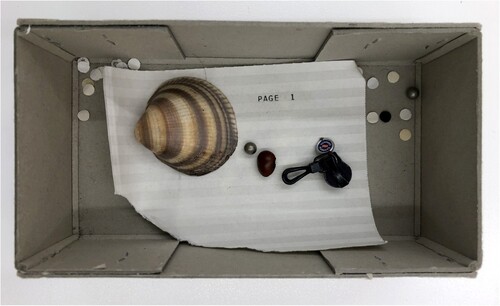

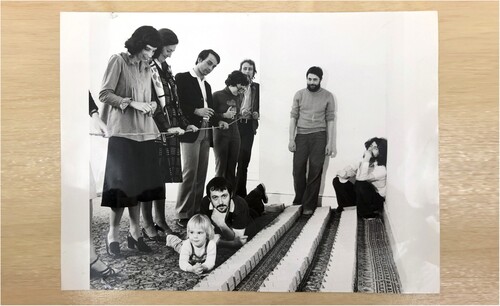

Other than the two notebooks, the Ecart Archives contain little information regarding Troc de Boîtes. Regrettably, it appears that only one from all the boxes received in exchange, whether by mail or by attendees of the event in person, have endured until the present time.Footnote26 However, several boxes assembled by the members of Ecart that never made it to participants have survived, allowing one to imagine what Matsuzawa received from the organisers of Troc de Boîtes. Each box, made from grey cardboard, numbered and signed by all three Ecart artists, contains ostensibly random, casual objects—from photographs, plant bulbs and candles to a squeaker balloon ( and ). Likewise, little is known about the actual event that took place on the 13 December 1975 on the Ecart premises. A lone photograph shows members of the group posing with rows of the assembled boxes displayed on the carpet covering the floor of the gallery ().Footnote27

Fig. 4 The bottom of one of the Troc de Boîtes boxes (no. 49) assembled by Ecart which remained in the Ecart Archives. Signed by John M. Armleder, Patrick Lux Luccini and Carlos Garcia. © Archives Ecart, Genève.

Fig. 5 The content of one of the Troc de Boîtes boxes (no. 49) assembled by Ecart which remained in the Ecart Archives. Signed by John M. Armleder, Patrick Lux Luccini and Carlos Garcia. Photo: © Archives Ecart, Genève.

Fig. 6 Ecart, boxes from Troc de Boîtes assembled on the floor of Ecart Gallery. © Archives Ecart, Genève.

The Ecart Group dissolved in the early 1980s, after losing the space to carry out their activities and after its members embarked on their own artistic and non-artistic projects.Footnote28 Armleder, whose artistic career flourished internationally in the decades that followed, took on the preservation of Ecart’s legacy. Following its dissolution, the Ecart material generated by the activities of group members, associates and collaborators throughout the decade of the 1970s was deposited in properties owned by Armleder’s family. Notwithstanding Ecart’s creative practice being primarily performative and concept-based, a remarkable abundance of material evidence chronicling the collective’s activities has endured until the present day.Footnote29 Yet it is only recently that the papers, photographs, magnetic tapes, finished and unfinished publications, ephemera, bills, and other materials, which accumulated over the course of Ecart’s activities throughout the decade, have coalesced into an archive. This transformation began in the early 1990s, when Lionel Bovier, then an art history student at the University of Geneva, decided to dedicate his master’s thesis to Ecart, thereby initiating a collaboration and a relationship with John Armleder that still persists.Footnote30 Bovier’s research resulted in an exhibition titled The Common Irresolution of an Equivocal Commitment, organised in 1997 at MAMCO and curated in collaboration with another Genevan art historian Christophe Cherix.Footnote31 To facilitate access to the material and the subsequent investigation into and selection of the items for the exhibition, the Ecart archive was deposited in Geneva’s Musee d’art et d’histoire, where Cherix worked as a curator.

While Ecart received considerable recognition and was showcased in numerous art spaces in the aftermath of the 1997 exhibition,Footnote32 the archives documenting the group’s activities has remained relatively neglected, with little curatorial or scholarly attention dedicated to its organisation and analysis. The archival material remained with Armleder until 2018, when it was temporarily moved to the newly opened building of Geneva University of Art and Design (HEAD-Genève).Footnote33 The relocation was triggered by a research project Ecart. Une archive collective, 1969–1982, instigated by Bovier, who in 2016 became the director of MAMCO.Footnote34 During this 2-year project, the Ecart Archives were not only rehoused, processed and analysed, but also tested in terms of its ability to communicate and support myriads of activities, including exhibitions, performances, public lectures and publications. One of the results of the project was the establishment of publicly accessible space dedicated to Ecart and integrated into MAMCO’s permanent display, which combines archival storage and a reading room together with an adjacent space for temporary exhibitions inspired by and based on the archive ().Footnote35

Fig. 7 The space hosting Ecart Archives at MAMCO that combines archival storage with a reading room. Photo: Aga Wielocha.

Although Ecart’s art defies categorisation and standardisation, Troc de Boîtes is to a certain extent representative of the artistic practice of the collective. It is a partially unfinished, process-oriented project, in which Ecart members acted as initiators and facilitators.Footnote36 The concept was based on principles of collaboration, chance and indeterminacy. The boxes assembled by Ecart comprised a collection of random objects, capable of eliciting spontaneous and arbitrary connections. Due to the loosely defined rules governing the game, the material received in return was likely to exhibit a similar degree of randomness. In the spirit of ‘intermedia’, the objective of the work was not to produce but to communicate, and the format of a game obliterated the division between creator, performer and audience.Footnote37

An isolated material artifact or remnant associated with Troc de Boîtes does not possess the ability to convey the impression of such a complex process-based project, nor does it preserve Ecart’s art.Footnote38 Instead, the project can be unveiled only through the collective presence of all artifacts and traces, where the artwork finds sustenance in the interplay between various elements. These elements are the objects (boxes), documentary traces of the project, both textual (letters, ephemera) and visual (the photograph), and all the tangible elements and intangible aspects lost or forsaken throughout the course of the project or after its termination, including human interaction. In a hypothetical scenario adhering to the rationale of segregating artworks and documents, where artworks are considered object-based entities, the boxes created and signed by the artists would be incorporated into MAMCO’s art collection. Conversely, the remaining materials associated with Troc de Boîtes, such as the notebooks, correspondence and the photograph, would find their place in the confines of the archive.Footnote39 Accordingly, the hypothetical treatment of the Troc de Boîtes project would categorise the boxes as artworks, while the archival material would serve as primary sources offering contextual information. While the physical remnants of the piece would be safeguarded and conserved as material entities, the artwork would remain in a dormant state, susceptible to the risk of fading into obscurity if its elements were to become disassociated in the future due to unforeseen circumstances. These circumstances may include alterations in the legal status of Ecart’s estate, modifications to the museum’s policies, or shifts in its curatorial or collection care strategies.Footnote40

If we return to the overarching concern that guides this article, on the fate of process-oriented, performative, participatory and instruction- or score-based artworks whose elements reside in archival holdings, the question is then how do we care for these kinds of artworks that derive their identity from the interconnectedness of textual, visual and object-based materials, as well as past processes and relationships? Is there a way to respect both their dependence on fragmented information dispersed among diverse records, encompassing various forms, shapes and media, and their reliance on the preservation of these elements together, mutually entangled with one another? How can one ensure not only the sustained existence of these artworks but also their liveliness and agency? To help answer these questions, I will turn to the concept of activation and trace its use and meanings across two different areas relevant to the current and future condition of the Ecart legacy—art conservation and archival studies.

Activating works, activating records and the ‘Archival Turn’ in art

Traditionally, art conservation, a field of study and practice, has been centred upon the examination, treatment and safeguarding of works of art, with a particular emphasis on tangible artifacts and their constituent materials. Its primary objectives have encompassed the repair, maintenance and overall preservation of artworks, thereby ensuring their protection against possible damage and gradual deterioration. The rapid transformation of art practices in the second half of the twentieth century led to the emergence of a specialisation within the field focussed exclusively on contemporary art. This specialisation arose primarily in response to the challenges presented by artists’ growing adoption of unconventional materials and new technologies throughout the twentieth century. While technical material-oriented research continues to be a vital component of knowledge production within contemporary art conservation, there has been a notable shift in focus since the beginning of the twenty-first century. The emphasis has now turned towards encompassing concepts, meanings and processes—the immaterial facets of artworks.Footnote41 The shift away from a focus on the physicality of art has been accelerated further with the growing presence of performance art within institutional art spaces. This shift has been accompanied by concerns surrounding the absence of adequate infrastructure and methodologies to ensure the continuity of this art form. Subsequently, it was primarily within the discourses concerning the conservation of performance art that the concept of activation gained prominence in the field.Footnote42

The verb ‘to activate’ inherently suggests the transformation of something from an inactive, or latent state to an active state. Within the realm of performance art, the notion of activation holds significant conceptual weight, as it encapsulates the fundamental essence of this art form. Performance art, by its very nature, operates as an agent of activation, dynamically energising spaces, objects and relationships. This includes the stimulation of interaction between the artist, viewer and the work itself.Footnote43 Within the context of art conservation, activation is comprehended as an action linked to the accessibility of a historical performance, despite the possibility that the timeframe in question may encompass relatively recent occurrences. To display a performance piece as live art it is necessary for it to be enacted, and the subsequent enactments of performance pieces are referred to as activations. Thus, the activation of an artwork, whether it belongs to the genre of performance or is created in any other medium such as kinetic art or installation art with time-based media components, involves transitioning it from a dormant state to an active one in which it can communicate with the public. Activation, occasionally employed as an alternative concept to reconstruction,Footnote44 is more than focussing only on a work’s recreation or replication, as it involves imbuing something with liveliness and vitality through contemporary modifications including its actualisation, updating or adaptation to a different context. These modifications might include migration, that is shifting between diverse materials, formats and media.

Within the context of archival science, the concept of activation takes on a distinct meaning. In the postmodern and post-Derridean understanding of the archive,Footnote45 it is no longer viable to perceive the archival record as a static artifact with predefined boundaries of content and context. Presently, there is a widespread recognition that narratives within an archive are shaped by the surrounding contexts, and archivists contribute to the archive and its constituent components through their practices, which encompass the creation of records, their processing, appraisal, and more. Additionally, according to Jacques Derrida, any interpretation of the archive itself becomes a means of enriching it, provided that the interpretive outcomes remain part of the archive.Footnote46 Furthermore, recontextualisation occurs at each stage of a record’s lifespan, resulting in the addition or subtraction of values to the record. Expanding upon this premise, Eric Ketelaar, a Dutch theorist of archives, asserts that every interaction, intervention, interrogation and interpretation carried out by creators, users and archivists can be deemed as an activation of the archival record. In addition, he posits that each activation leaves a lasting impression on the record, consequently altering the significance of prior activations.

This approach involves actively engaging with archival records related to a given artwork, drawing on established archival research methods like records analysis, close reading, interpretation and comparative study. By employing these techniques both within and beyond the archive, the goal is to develop strategies that effectively bring artworks into an active state where they can meaningfully communicate with the public. It is crucial to emphasise that this definition holds true only when one refrains from regarding the archive as a static domain solely preserving evidence of an artwork’s past changes. Instead, it should be viewed as a dynamic entity oriented towards the future, encompassing the potentiality for the activation of mutable artworks with their identities distributed among a constellation of documents.Footnote47

The notion of activation, as expounded in this context, bears some methodological resemblance to what has been identified as the ‘archival turn’ within the domain of contemporary art practice.Footnote48 This notion indicates a significant shift towards engaging with archives as sites for inquiry, intervention and artistic exploration, ultimately giving rise to a multifaceted body of art practices that activate the archives to establish meaningful connections between past and present.Footnote49 Within this context, artists scrutinise the archive as a symbolic framework for exploring societal memory and oblivion, and archives as a rich terrain for critical examination to denote manifestations of power, knowledge, authority, and the representation and formation of individual and collective identities. To render ‘historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present’, artists employ a diverse range of critical-aesthetic strategies with the purpose of re-evaluating historical narratives.Footnote50 Through techniques such as deconstruction, collage, juxtaposition, reconfiguration and even the fabrication of records,Footnote51 this engagement culminates in outcomes that hold inherent artistic value and often stand independently as works of art.

It is crucial to acknowledge that the activation of artworks, as described in this context, is not a novel concept and is often being employed within archives and collections. Such strategies are discernible in curatorial practices, either directly undertaken by curators or facilitated through artistic commissions. They serve purposes of actualisation, recontextualisation, display and mediation of historical pieces, including those pertaining to the legacy of Fluxus. The aim of this article is to discern and classify a range of practices that, albeit unfolding within diverse contexts, demonstrate comparable methodological approaches and converge towards a common outcome, specifically, the transformation of artwork into a state that enables its continued and active experience, appreciation and engagement by the public. Additionally, I argue that these activation strategies can potentially serve as valuable tools within the framework of expanded conservation, going beyond the physical art object to encompass broader aspects of the artwork’s potential existence.Footnote52 Keeping this in mind, we now turn to examining one of the activation strategies employed within the Ecart Archives and assess its alignment with conservation’s objectives, that is to protect, document and preserve artworks to ensure they can continue to be enjoyed, studied and understood

From continuation to completion: assessing activation as a conservation strategy

In 1974, Hervé Fischer, a French-Canadian artist, published an anthology aimed at documenting and cataloguing artist stamps—one of the myriad forms of artistic expression within the framework of mail art.Footnote53 In the same year, Ecart artists invited Fischer to their space and organised a presentation of the newly released book. The encounter sparked a collaborative proposal for a second volume of the anthology,Footnote54 and in order to gather material for the new book, contributors were contacted by mail and requested to send their stamp prints to Geneva, following the methodology established by Fischer for the first volume. The project, ambitious in its scale and complexity, overwhelmed the publishers with the sheer number of contributions. Despite adding two addenda to the initial collection, the launch of the book faced numerous delays. Eventually, due to the dissolution of the Ecart Group in the early 1980s, the project was abandoned.Footnote55 The offset printed pages,Footnote56 along with other Ecart traces, were stored by Armleder and subsequently became part of the Ecart Archives.Footnote57

In 2018, the printed pages were displayed in exhibition at MAMCO.Footnote58 After the show ended, Armleder, in agreement with Hervé Fischer, decided to bring the project to its culmination, albeit with a delay of four decades. In 2019, as part of the research project Ecart. Une archive collective, 1969–1982, the pages that had been printed around 1979 were bound, a new cover was added, and the book finally entered international distribution through Ecart Books—an online mail-order bookstore managed by Armleder’s studio.Footnote59 The printed pages underwent multiple transformations, transitioning from being a by-product of an art project involving the collaboration of hundreds of artists coordinated by Ecart and Fischer, to archival documents and an exhibit showcasing the phenomenon of mail art and the collective’s artistic practice. Finally, the pages assumed the form of a complete artist’s book, which, in turn, re-entered the Ecart Archives as a distinct artwork in its own right.Footnote60

This particular instance of engaging with archival materials, with the intention of bringing the artwork into an active state and facilitating its communication with the public, closely corresponds to the previously outlined concept of activation. Within this framework, the specific strategy employed in this case could be referred to as ‘completion’. However, can the act of binding pages printed decades ago into a book that previously did not exist be potentially considered a form of conservation? If so, what are the reasons behind this classification?

On the one hand, from the standpoint of established conservation thinking and standard modern museum practices, the idea of activation as a potential conservation strategy may raise concerns. In the case of the stamp anthology, the historical materiality of the artistic output, even if it was primarily created through the means of reproduction and exists in multiple versions, has been significantly altered. What is more, the intervention resulted in the relinquishment of control over the material remnants to private buyers for their personal enjoyment. The original concept of the book has undergone modifications, as the essays initially intended to accompany the stamp collection were ultimately omitted from the final version.Footnote61 Furthermore, the absence of any surviving remnants of the original cover design within the archive necessitated the creation of an entirely new cover, thereby introducing a creative element into the process.

On the other hand, in this specific case, conventional conservation practices are limited to regarding the pages as ‘prints on paper’, emphasising their material properties, which is a valid and necessary approach. However, solely focussing on materiality neglects the creative process involved in crafting the book, rendering it inactive or latent. To consider the delayed publication of the book itself as an act of conservation requires a shift in understanding, moving away from viewing the finished art object (the book) as the sole focal point. Instead, the activation revolves around the processes of publishing and distribution, recognising them as the primary objectives and acknowledging the process itself as a work of art.Footnote62

A creative gesture as a form of conservation can also be regarded as unconventional within established conservation principles. The field of conservation has been hesitant to embrace creativity due to its association with the contentious issues of subjectivity, agency and authorship in conservation interventions. The prevailing belief within the field has been to maintain the invisibility of the conservator, although this notion has become somewhat of a myth in conservation practice.Footnote63 In this context, the significance of invisibility resides in the ability to present knowledge or information without any interference or prejudice, and it is linked to the protection of a hierarchical structure of authorship in relation to the artwork. Nevertheless, a growing recognition and acceptance of agency and subjectivity within the field of conservation and a standpoint that each conservation intervention can be viewed as a creative act challenge the conventional perception of conservation as a purely technical, science-driven and neutral endeavour.Footnote64 This shift can provide an opportunity to embrace unorthodox strategies such as activation as complementary ways of perpetuating works of art.

What was achieved with the Ecart–Fischer volume through the process of activation and what was conserved? Arguably, activation transformed the pages into a book and facilitated their wider distribution, which was one of the principal aims of the art project. In this manner, the artworks, supplied by both the publishers of the book and the individual contributors to the stamp collection, were communicated to the public, albeit to a potentially different one due to the significant delay in its distribution over the course of decades. Furthermore, the process reignited certain relationships that were instrumental in the book’s inception, such as the relationship between Armleder and Fischer.

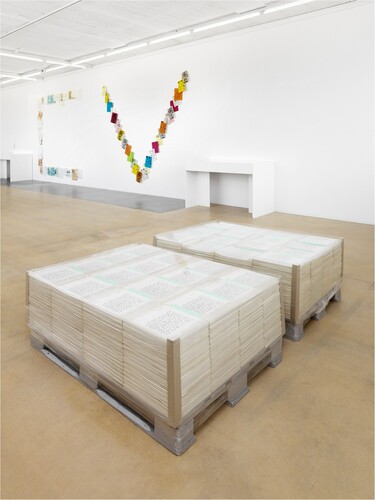

Certainly, completing the project through the publication of the book is not the sole method by which this work can be activated, just as there is no single approach to conserving a work of art. A set of the original pages remains in the archive, awaiting the engagement of another creative team or individual employing a distinct approach. Indeed, the recent history of the second volume of the stamp anthology already encompasses an exemplification of a different activation strategy, one that can be termed ‘display’. During the exhibition held at MAMCO in 2018, the 600 copies comprising the 310 offset printed pages were meticulously arranged on two wooden pallets, evoking the impression of being freshly delivered from the print shop (). Showcasing the set of pages in their transitional state, between remnant, document and an anticipated book, and transforming them into an exhibit that represents the project, can be understood as a form of activation within the framework defined earlier.

Fig. 8 Pages from Art & Comunication Marginale. Tampons d’artistes/Artist Rubber Stamps. Vol. 2, assembled on wooden pallets for the exhibition ‘Mail Art’ (MAMCO, Geneve, 12 September 2018–5 May 2019), curated by Lionel Bovier and Elisabeth Jobin. © Photo: Annik Wetter/MAMCO.

However, if one follows the premise that the process of publishing the book is the crux of the artwork in this instance, a static exhibit with its story conveyed through a wall label may feel somewhat inadequate in fully realising the objective of bringing the artwork to an active state in which it can communicate with the public. Although this display strategy can also be considered as activation and is entirely valid as such, it seems to lack the element of imbuing liveliness and reinstating the processual aspect of the piece. Therefore, there exist numerous diverse ways in which a work can be activated, and each activation can address distinct aspects or meanings inherent to the work.

The mobilisation of such a ‘completion’ as activation and a conservation strategy can raise significant ethical issues, particularly concerning the legacy of Ecart and other artists associated with Fluxus. The cases of Troc de Boîtes (1975) and the second volume of the stamp anthology, demonstrate that Ecart had a range of uncompleted projects within the scope of its endeavours. Various sources, including announcements in newsletters, indicate that there are multiple Ecart projects that have remained unfinished, at least up until the present time.Footnote65 As Elizabeth Jobin notes, Ecart deliberately favoured the incomplete as opposed to the finalised artistic outcome, actively ‘cultivating partial irresolution’.Footnote66 This approach served as a means for Ecart artists to distance themselves from the traditional economy of the unique, completed artwork within institutional circulation. By placing emphasis on the process rather than the ultimate result, Ecart embraced the concept of unfinishedness as a defining characteristic of their artistic practice, prioritising the process over the final outcome. This observation, however, raises a question as to whether this inherent incompleteness should be respected by the stakeholders of the Ecart legacy, as the inherent feature of Ecart’s works. Particularly relevant is the fact that the members of the group will eventually no longer be present to provide guidance or authorise any process of ‘completion’.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the concern raised in this context is not exclusive to activation as a conservation strategy. Instead, it aligns with the broader challenges faced by stewards of contemporary art, including both curators and conservators in their everyday decision-making processes and addressing such concerns necessitates diligent research conducted on a case-by-case basis. Despite the potential risks involved, these stewards often take the initiative to deviate from the ‘original intent’ and prioritise public access to art.Footnote67 In this regard, I contend that the value of activation within the archival realm lies in the fact that it alters the archive each time it is employed. But in doing so, it not only enriches the archival record but also secures traceability of interventions and contributes to the ongoing and future discussions about what constitutes the work of art and how to care for it effectively.

In the realm of museum studies and practice, the term ‘preservation’ typically refers to comprehensive safeguarding strategies encompassing the operations of collecting, documenting, conserving and managing collections. Preservation aims to be non-invasive, peripheral, and oriented towards protecting against deterioration and damage.Footnote68 In contrast, conservation entails both preventive measures and direct, hands-on intervention and it typically involves engaging with a singular ‘object of conservation’ with the objective of maintaining or restoring its state or appearance that effectively conveys its message to the viewer. Considering this perspective, if archives are regarded as sites of preservation, strategies for engaging with specific artworks through various types of documents denoted here as activation, may be considered as a conservation method.

However, it is crucial to interpret this comparison with some flexibility. While it has been arguably demonstrated that activation plays a role in the preservation of artworks, it should not be seen as a complete replacement for existing conservation practices. Rather, it presents a fresh and valuable addition to the toolkit used by stakeholders involved in the care of artworks. As such, activation can complement or expand upon the conventional methods associated with conservation practices.

Conclusions

Archives are widely recognised as sites dedicated to the preservation of archival records to extend their usable lifespan by safeguarding their material form. However, beyond the preservation of the physical medium, archives also serve to safeguard the content contained within, encompassing facts, events, memories, meanings and narratives. Within this context, this article proposes that artists’ archives, particularly those associated with performative, processual, participatory or concept-based art practices that may not culminate in physical, stable end-products, have the potential to serve as sites for the preservation of artworks.

With this in mind, let us revisit the postcard that was sent from Geneva to Shimosuwa during the autumn of 1975 and test what potential Troc de Boîtes, acknowledged as a process-based artwork, holds for activation as a conservation strategy. The process could commence by scrutinising the available knowledge concerning the piece and identifying any information gaps. This would be followed by fact-checking and conducting inquiries, such as interviewing participants and artists involved, locating current owners of remaining Ecart boxes, and conducting further archival research, among other relevant methodologies. The subsequent phase of the campaign would involve disseminating the collected data through means such as exhibitions or publications accompanied by a collaborative re-performance of the box barter, staged in either a physical or virtual space and carried out as an artistic commission. Irrespective of the chosen format, this undertaking holds the potential to re-contextualise Troc de Boîtes to address contemporary issues, thus rendering it both relevant and significant for present-day audiences. It also can reshape the archival content and structure, potentially revealing pertinent material that was previously unassociated with the archives or adjusting existing classifications. The knowledge generated throughout this process would become part of the archives, introducing fresh layers of meaning, contexts, perspectives and interpretations.

Within the framework of expanded conservation, this concept of activation might serve as a transformative tool, facilitating a further shift in the understanding of conservation from a series of actions centred solely on the materiality of an object and carried out exclusively by conservators with professional training. Instead, it encompasses a collaborative endeavour involving various stakeholders invested in preserving an artistic legacy, such as artists, curators, archivists, researchers, mediators, performers, community members and others who share a commitment in keeping art alive. By emphasising conservation as a shared objective and a collective responsibility, this approach seeks to counteract the exclusionary professionalisation of art care, thereby making it a more inclusive, diverse and attainable reality. This is particularly crucial considering that conservation is not a singular, isolated undertaking, but rather a continuous and enduring commitment that demands persistent dedication and recurring activations to keep an artwork alive and active.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was conducted within the project ‘Activating Fluxus’, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and based at the Institute of Materiality in Arts and Culture at Bern Academy of the Arts, Bern University of Applied Sciences. I am indebted to Hanna Hölling and Jules Pelta Feldman who read this article in a draft form and offered invaluable suggestions for its improvement. My gratitude goes to Elizabeth Jobin and Lionel Bovier for providing insights into Ecart’s artistic practice and the specificity of its Archives. Special thanks are extended to John Armleder, whose efforts have been instrumental in ensuring the continued preservation and activation of Ecart Archives up to the present day. I also acknowledge the considerate input of the anonymous reviewers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aga Wielocha

Aga Wielocha is a researcher, collection care professional and conservator specialising in modern and contemporary art. Her research interests revolve around the mechanisms and processes of institutional art collecting, with a focus on contemporary formats such as media art, art projects, participatory art and performance. Currently, she holds a postdoctoral position at the Bern Academy of the Arts, contributing to the research project ‘Activating Fluxus’. Previously, Aga worked at Hong Kong’s M+ Museum, where she devised efficient documentation strategies to support the care of expanding collections. Before that, she served as a conservator at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and worked for many years in private practice.

Notes

1 This article follows the pragmatic distinction between the notion of ‘the archive’ and of ‘an archives’ proposed in Michelle Caswell, ‘“The Archive” Is Not an Archives: Acknowledging the Intellectual Contributions of Archival Studies’, Reconstruction. Studies in Contemporary Culture 16, no. 1 (2016): 1–21.

2 For an overview of discourses related to archives of contemporary art see, for example, Beatrice Von Bismarck et al., eds, Interarchive: Archival Practices and Sites in the Contemporary Art Field (Cologne: Walther König, 2002); Judy Vaknin, Karyn Stuckey, and Victoria Lane, All This Stuff: Archiving the Artist (Faringdon: Libri Publishing, 2013). In 2014 the College Art Association (CAA) Annual Conference in Chicago hosted a session about artists’ archives before and after they move to institutions; see: Marcia Reed, ‘From the Archive to Art History’, Art Journal 76, no. 1 (2017): 121–8.

3 For an overview of the use of archival material for display within the context of modern and contemporary art see, for example, Nesli Gül Durukan and Kadriye Tezcan Akmehmet, ‘Uses of the Archive in Exhibition Practices of Contemporary Art Institutions’, Archives and Records 42, no. 2 (2021): 131–48.

4 This assertion is mainly pertaining to large collecting institutions, and in particular, to museums. For example, according to the description on Tate’s website, ‘an artist’s archive usually consists of documentation and “secondary material”. This includes material traditionally created alongside an artwork (…)’. Tate, ‘Art Term: Archive’, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/archive (accessed 30 March 2024).

5 Lucy Lippard and John Chandler, ‘The Dematerialization of Art’, Art International 12, no. 2 (1968): 31–6.

6 For a comprehensive examination of documentation as an artistic practice during the 1960s on an international scale, see, for example, Christian Berger and Jessica Santone, ‘Documentation as Art Practice in the 1960s’, Visual Resources 32, no. 3–4 (2016): 201–9.

7 The phenomenon of elevating artistic process over finished product in modern and contemporary was meticulously explained in Kim Grant, All About Process (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017).

8 Hanna B. Hölling, ‘Activating Fluxus’ (unpublished project proposal, Swiss National Science Foundation, 2020).

9 Natilee Harren, Fluxus Forms: Scores, Multiples, and the Eternal Network (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2020).

10 For a typology of Fluxus scores see Julia Robinson, ‘Parsing Scores: Application in Fluxus’, Oncurating.org, no. 51 (2021): 51–63.

11 For a discussion around documentation as both process and system within Fluxus as a social network, see Jessica Santone, ‘Documentation as Group Activity: Performing the Fluxus Network’, Visual Resources 32, no. 3–4 (2016): 263–81.

12 The term ‘Intermedia’ was put forward by Dick Higgins, artist and publisher associated with Fluxus in the mid-1960s, to characterise artworks that blend elements of multiple artistic genres. For instance, Higgins points to poetry presented visually through text arrangement (visual poetry), poetry that becomes a sound when read (sound poetry), theatrical works incorporating music and painting (happenings), and other hybrid arts that intersect traditionally distinct disciplines. See, for example, Dick Higgins and Hannah B. Higgins, ‘Intermedia’, Leonardo 34, no. 1 (2001): 49–54. For an understanding of the dilemmas arising from categorising Fluxus works in relation to the challenges encountered during the processing of the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Archive of Fluxus art donated to MoMA in New York in 2008 see, for example, Julia Pelta Feldman, ‘Perpetual Fluxfest: Distinguishing Artists’ Records from Artworks in the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives’, in Artists’ Records in the Archives: Symposium Proceedings (New York, 2011), 31–4.

13 These practices are traditionally object-based, as I argue elsewhere: Aga Wielocha, ‘Collections of (An)Archives: Towards a New Perspective on Institutional Collecting of Contemporary Art and the Object of Conservation’, in Conservation of Contemporary Art, ed. Renée van de Vall and Vivian van Saaze, vol. 9 (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2024), 259–79.

14 What has been called neo-avant-garde art, particularly Fluxus, with its unconventional mediums and formats, was at first primarily collected by enthusiastic individuals and some significant private collections of Fluxus art have now been integrated or transformed into institutions. Some notable examples of these include Archiv Sohm, Archivio Conz, Sammlung Andersh, Sammlung Feelisch, Sammlung Cremer, Sammlung Hahn, Luigi Bonotto Collection, and the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, among many others. For a comprehensive list of the public and private collections of Fluxus art, see: Activating Fluxus, ‘Collections and Archives’, https://activatingfluxus.com/collections-and-archives/ (accessed 6 June 2023).

15 The argument that many contemporary artworks consist of spatially and materially distributed gathering of elements that were conceived and might be perceived as one work has been explored in, for example, Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (London and New York: Verso, 2013); and Adam Geczy and Sean Lowry, ‘Where Is Art?’, in Where Is Art?: Space, Time, and Location in Contemporary Art (New York: Routledge, 2022), 4–34. The notion of identities of contemporary artworks being distributed between objects and documents and how this phenomenon affects the perpetuation of those artworks is explained further in Aga Wielocha, ‘Art Objects as Documents and the Distributed Identity of Contemporary Artworks’, ArtMatters International Journal of Technical Art History, Special Issue no.1 (2021): 106–13; Wielocha, ‘Collections of (An)Archives’, 202.

16 As described on the institution’s website, the activities performed by the Conservation Laboratory at National Archives Washington, DC ‘contribute to the prolonged usable life of records in their original format. The Conservation Lab repairs and stabilizes textual records (un-bound papers, bound volumes, and cartographic items) and photographic images […] and provides custom housings for these records as needed’. See: National Archives, ‘About Preservation’, https://www.archives.gov/open/plain-writing/examples/preservation-about-before.html (accessed 30 March 2024).

17 This article employs an expansive conception of performance art and follows the delineation that performance may encompass painting, sculpture, movement, character or role-creation, event staging, and production of experiences. For more detail on this definition see, for example, Gabriella Giannachi, ‘Performance at Tate: The Scholarly and Museological Context’, Tate Research Feature (December 2014), https://www.tate.org.uk/research/features/performance-scholarly-museological-context (accessed 14 June 2023). For the works analysed here, their collaborative and participatory qualities are regarded as the key performative elements.

18 Rebecca Schneider, ‘Performance Remains’, Performance Research 6, no. 2 (2001): 100–8; Rebecca Schneider, Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London and New York: Routledge, 2011).

19 Schneider, ‘Performance Remains’, 105.

20 See, for example, Aga Wielocha, ‘Collecting Archives of Objects and Stories: On the Lives and Futures of Contemporary Art at the Museum’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2021); Wielocha, ‘Art Objects as Documents’; Wielocha, ‘Collections of (An)Archives’.

21 The postcard was consulted in the Ecart Archives at MAMCO, Geneva, in the autumn of 2022.

22 See, for example, Hal Foster et al., ‘1962a’, in Art since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007), 456–62.

23 For a more in-depth analysis of the connections between Fluxus and Ecart see, for example, Aga Wielocha, ‘Ecart as Fluxus: Get Inspired and Inspire’, Activating Fluxus project website, 2022, https://activatingfluxus.com/2022/09/09/ecart-as-fluxus-get-inspired-and-inspire/ (accessed 14 June 2023). For an account on Ecart’s connection with Fluxus see, for example, Ecart and John Armleder, ‘Suisse Romande et Fluxus’, in Fluxus International & Co. A Geneve (Geneva: Association Musee d’Art Moderne, 1980).

24 Matsuzawa’s interest in parapsychology led him to formulate his own theory of Psi, which derived from non-sensory cognitive abilities. He employed this idea in multiple works created mainly in the 1960s: Reiko Tomii, Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016).

25 Originally in French as ‘1 paire de lunettes, 1 morceau de teinture, 1 pierre verte, 1 taquet, 1 clou, 1 clou pour tableau’. Translated by the author.

26 According to Armleder, the boxes may have been destroyed as a result of a leaking roof in one of the storage spaces hosting the material that later become the Ecart Archives. Personal communication with the author, October 2022. In the Ecart Archives, the sole ‘return box’ identified originated from Tony Ward of Arc Publications—a UK poetry publisher established in 1969, and renowned for its focus on contemporary poetry. The box contains an assortment of items, including a tea bag, a small cigar box, a miniature replica of a church, a postage stamp and a few other enigmatic objects that proved challenging for this author to identify.

27 The overall concept of Troc de Boîtes is described in Lionel Bovier and Christophe Cherix, eds, Ecart Geneva, 1969–1982 (London: Koenig Books, 2019), 72, 166.

28 Bovier and Cherix, Ecart Geneva, 1969–1982, 122.

29 In a conversation with the author, Armleder admitted to being the type of impulsive collector who takes home sugar cubes from restaurants, comparing this practice with his collecting the remnants from the heyday of Ecart.

30 Lionel Bovier, ‘Ecart’ (undergraduate dissertation, University of Geneva, Faculty of Literature, Department of Art History, Geneva, 1995), cited in Bovier and Cherix, Ecart Geneva, 1969–1982, 133.

31 The French title of the exhibition was L’irrésolution commune d’un engagement équivoque. For more information about the exhibition, see: MAMCO Geneva, ‘Exhibitions: Ecart’, https://www.mamco.ch/en/1212/ECART (accessed 14 June 2023). The exhibition was accompanied by the book in French with the same title authored by the curators; Lionel Bovier and Christophe Cherix, eds, L’irrésolution Commune d’un Engagement Équivoque—Ecart, Genève (1969–1982) (Genève: MAMCO and Cabinet des estampes, 1997). The second, English edition of this book was published in 2019 and is a main reference related to the Ecart trajectory included in this essay; Bovier and Cherix, Ecart Geneva, 1969–1982.

32 Bovier and Cherix, Ecart Geneva, 1969–1982, 123.

33 Bovier and Cherix, Ecart Geneva, 1969–1982, 8.

34 ‘Ecart. Une archive collective, 1969–1982’ (September 2017–April 2019) was an art practice-based research project led by HEAD-Geneva in collaboration with MAMCO and financed by the strategic fund of the HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland. For more information about the project, see HEAD-Genève, ‘ECART’, https://www.hesge.ch/head/projet/ecart (accessed 14 June 2023). See also Bovier and Cherix, Ecart Geneva, 1969–1982, 125.

35 MAMCO Geneve, Director’s Choice: Les Archives Ecart (Vimeo, 2022), https://vimeo.com/664169115?embedded=true&source=vimeo_logo&owner=14050988 (accessed 3 April 2024).

36 One of the anticipated results of the project, as indicated in the invitation postcard, was the publication of ‘the record’ of the event. However, upon thorough examination of the documents in the Ecart Archives by the author, no evidence of such a publication was found.

37 As Fluxus artist Eric Andersen noted ‘[The term intermedia] was first conceived in the period 1958–62 and has constantly changed form ever since. It cannot by definition be categorised as a thing, only as methods. Inter Media rejects art and communication as production. Instead, it seeks by means of constant innovation to conduct fundamental research in human articulation. The oeuvre here is not a demarcated unit. The work is open and undergoing constant change because it includes the spectator’. Eric Andersen, ‘What Is … ?’, in The Fluxus Constellation, ed. Sandra Solimano (Genova: Neos Edizioni, 2002), 24.

38 A similar observation regarding traces in the archives of performance art can be found in Irene Müller, ‘Preserving the Ephemeral’, in Performing Documentation in the Conservation of Contemporary Art, ed. Lúcia Almeida Matos, Rita Macedo, and Gunnar Heydenreich (Lisbon: Instituto de História da Arte, 2015), 19.

39 In fact, one of those boxes has been acquired as an artwork by Musee d’art at d’historie de Genève (MAH) and it is listed on its collection website. See: MAH, ‘Troc de boîtes’, https://collections.geneve.ch/mah/oeuvre/troc-de-boites-ecart-geneve/e-95-0035 (accessed 14 June 2023). According to the information on the website, the box was donated by artists Jean-Luc Manz. It is unclear if the artist participated in Troc de Boîtes himself.

40 In the case of the Ecart Archives, all those possibilities are viable. Legally, the archives, although deposited at MAMCO, are still the propriety of Armleder, who keeps one of the keys to the door to the archive. The agreement with Armleder on depositing the Ecart Archives in the museum is based on the trust built over the years and it implies that the status of the archive will not change while the artist is still alive. One repercussion for the scope of institutional responsibility is that as the archives are legally not part of the MAMCO collection the museum is not obliged to complete its full inventory. This unique condition allows the stakeholders to experiment with how Ecart’s changing work is represented in the archives and to maintain an ongoing collaboration with Armleder to decide what materials to keep, how to preserve them and where to store them for future use. Personal communication, Lionel Bovier in conversation with the author, October 2022.

41 Cf. for example, Lydia Beerkens, ‘Side by Side: Old and New Standards in the Conservation of Modern Art. A Comparative Study on 20 Years of Modern Art Conservation Practice’, Studies in Conservation: Saving the Now, Preprints of the International Committee of Conservation (IIC) 2016 Los Angeles Congress 61, Supp. No. 2 (2016): 12–6.

42 It is important to mention that similar notions have been used before in conservation scholarship with, for example, active versus deactivated media employed in Hanna Hölling, Paik’s Virtual Archive: Time, Change, and Materiality in Media Art (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2017). The notion of activation in the context of the conservation of performance art includes Pip Laurenson and Vivian van Saaze, ‘Collecting Performance-Based Art: New Challenges and Shifting Perspectives’, in Performativity in the Gallery: Staging Interactive Encounters, ed. Outi Remes, Laura MacCulloch, and Marika Leino (Bern: Peter Lang, 2014), 27–41; Louise Lawson, Acatia Finbow, and Hélia Marçal, ‘Developing a Strategy for the Conservation of Performance-Based Artworks at Tate’, Journal of the Institute of Conservation 42, no. 2 (2019): 114–34; Helia Marçal and Louise Lawson, ‘Unfolding Interactions in the Preservation of Performance Art at Tate’, Transcending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation. ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference Preprints, Beijing, 17–21 May 2021 (2021); Brian Castriota, ‘Object Trouble: Constructing and Performing Artwork Identity in the Museum’, ArtMatters International Journal of Technical Art History, Special Issue no.1 (2021): 1–10. In this context the notion of activation has been rigorously defined in Lawson, Finbow, and Marçal, ‘Developing a Strategy for the Conservation of Performance-Based Artworks at Tate’, 122.

43 Cf. for example, Daid Zerbib, ‘Performing, Participating: The Challenge of Activation’, Critique d’art, no. 52 (2019): 71–87; Catherine Wood, Performance in Contemporary Art (London: Tate Publishing, 2018).

44 Anna Schäffler, ‘Out of the Box: Preservation on Display’, in The Explicit Material: On the Intersections of Conservation, Art History and Human Sciences, ed. Hanna Hölling, Francesca G. Bewer, and Katharina Ammann (Leiden and Boston, MA: Brill, 2019), 167–85.

45 For a discussion on the impact of Derrida’s notion of the archiving see, for example, Tom Nesmith, ‘Seeing Archives: Postmodernism and the Changing Intellectual Place of Archives’, The American Archivist 65, no. 1 (2002): 24–41.

46 Jaques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz, ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression’, Diacritics 25, no. 2 (1995): 9. See also Caswell, ‘“The Archive” Is Not An Archives’.

47 Cf. Hanna B. Hölling, ‘Archival Turn. Towards New Ways of Conceptualising Changeable Artworks’, Acoustic Space 14, no. DATA DRIFT. Archiving Media and Data Art in the 21st Century (2015): 73–88.

48 See, for example, Cheryl Simon, ‘Introduction: Following the Archival Turn’, Visual Resources 18, no. 1 (2002): 101–7. The writings on this phenomenon have been compiled in Sara Callahan, Art + Archive: Understanding the Archival Turn in Contemporary Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022).

49 See Kathy Michelle Carbone, ‘Artists and Records: Moving History and Memory’, Archives and Records 38, no. 1 (2017): 100–18.

50 Hal Foster, ‘An Archival Impulse’, October 110, (Autumn 2004): 4.

51 Cf. for example, Carbone, ‘Artists and Records’. Charles Merewether, ed., The Archive (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2006) offers an exploration of the diverse artistic practices that engage with the theoretical concept of the archive and delve into archival content. The survey includes notable artists such as Susan Hiller, Ilya Kabakov, Thomas Hirshhorn, Renée Green and The Atlas Group.

52 The term ‘expanded conservation’ has been in use within the field of conservation and beyond for approximately a decade with an early mention in Annet Dekker, ‘Enabling the Future, or How to Survive FOREVER: A Study of Networks, Processes and Ambiguity in Net Art and the Need for an Expanded Practice of Conservation’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of London, 2014). The notion signifies that the scope of conservation has broadened, leading conservators and conservation theorists to incorporate a wider range of disciplinary perspectives. This expanded approach encompasses fields such as art history, anthropology, comparative literature, media theory, art and curatorial practice, philosophy, and others. See, for example, Caroline Fowler and Alexander Nagel, eds, The Expanded Field of Conservation (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2022).

53 Hervé Fischer, ed., Art et Communication Marginale: Tampons d’artistes/Art and Marginal Communication/Rubber Art, Stamp Activity/Kunst Und Randkommunikation: Künstlers Stempelmarken (Paris: Balland, 1974); Bovier and Cherix, Ecart Geneva, 1969–1982, 61.

54 Fischer's book was published during the peak of the phenomenon of mail art, when collecting and producing stamps was prevalent among those involved in the movement. Ecart, from its early stages, demonstrated a keen interest in stamps, with Ecart artists frequently creating their own. The selection of stamps by Ecart Group, Ecart Publications, Patrick Luccini, Carlos Garcia and John Armleder are featured in the second volume of the anthology: Hervé Fischer and Groupe Ecart, eds, Art & Comunication Marginale. Tampons d’artistes/Artist Rubber Stamps. Vol. 2 (Geneva: Ecart Publications et Mamco, 2019). For more information about the genre of artist stamps see: Elisabeth Jobin, ‘Le Livre d’artistes Mis En Réseau. Art et Communication Marginale Vol. II Par Le Groupe Ecart et Hervé Fischer’, Les Cahiers Du Mnam, no. 149 (2019): 84–103.

55 Jobin, ‘Le Livre d’artistes Mis En Réseau’, 84–103.

56 Before abandoning the project, Ecart team managed to print 310 out of 550 pages planned and announced in a newsletter to the subscribers. See: Jobin, ‘Le Livre d’artistes Mis En Réseau’, 87.

57 The determination of whether all the offset printed pages of the book were indeed included in the Ecart Archives is a nuanced matter that relies on locating the precise moment when Ecart’s legacy transitioned into an officially recognised archive. One could argue that these pages were excluded during the appraisal process carried out within the framework of the Ecart. Une archive collective, 1969–1982 project.

58 Exhibition Mail Art, MAMCO, Geneva, 12 September 2018–5 May 2019, curated by Lionel Bovier and Elisabeth Jobin.

59 Ecart Books, ‘Hervé Fischer & Groupe Ecart. Art & Communication Marginal/Artists Rubber-Stamps Vol_2’, https://ecart-books.ch/products/herve-fischer-groupe-ecart-art-communication-marginal-artists-rubber-stamps-vol_2 (accessed 14 June 2023).

60 Fischer and Groupe Ecart, Art & Comunication Marginale.

61 Jobin, ‘Le Livre d’artistes Mis En Réseau’, 84–103.

62 Or ‘the object of conservation’ in conservation parlance.

63 For an analysis of the notion of invisibility in the field of conservation see: Zoë Miller, ‘Practitioner (In)Visibility in the Conservation of Contemporary Art’, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 60, no. 2–3 (2021): 197–209.

64 Hölling, ‘Archival Turn’, 73–88; Jonathan Kemp, ‘Conservators, Creativity, and Control’, Studies in Conservation, (13 August 2023), 1–14, doi:10.1080/00393630.2023.2241246.

65 These include editorial projects by Nicole Gravier, Anthony McCall, Taka Imura, Al Souza, Jochen Gerz, Massimo Nannucci and Raúl Marroquin, see Jobin, ‘Le Livre d’artistes Mis En Réseau’, 103.

66 In French ‘cultiver une irrésolution partielle’ (Jobin, ‘Le Livre d’artistes Mis En Réseau’, 96).

67 In recent decades, the concept of original or artist’s intent as a pivotal reference point in decision-making processes regarding the preservation of artworks has been subject to scrutiny and criticism by numerous scholars and practitioners. It has been observed that this notion is often employed in a broad sense, encompassing not only the initial ideas that guided the creation of an artwork but also the subsequent opinions expressed by artists over the course of time. See, for example, Glenn Wharton, ‘Artist Intention and the Conservation of Contemporary Art’, AIC Objects Specialty Group Postprints 22 (2015). Moreover, it has been noted that the term is frequently utilised as a convenient means to resolve the complexities of an artwork’s identity and to establish a singular, uncontested interpretation; see, for example, Paolo Martore, ‘The Contemporary Artwork between Meaning and Cultural Identity’, CeROArt, no. 4 (2009). The artist’s original intent has also been characterised as a concept that is fluid and subject to change by, for example, Rebecca Gordon and Erma Hermens, ‘The Artist’s Intent in Flux’, CeROArt (2013), https://ceroart.revues.org/3527 (accessed 14 June 2023). For an in-depth exploration of the historical development, various meanings and contemporary applications of the notion of intent in the realm of art, see also a comprehensive study conducted by Nina Quabeck, ‘The Artist’s Intent in Contemporary Art: Matter and Process in Transition’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2019).

68 See: François Mairesse, Dictionary of Museology (London: Routledge, 2023), 440–3. It is important to acknowledge, however, that this understanding of preservation is not the only one that circulates in the field.