ABSTRACT

This paper critically analyzes how empty signifiers – demands which have been ‘tendentially’ emptied of meaning to represent an infinite number of demands – gain and lose credibility. I mobilize Laclauian discourse theory and a logics of critical explanation approach to examine the case of an English County Council and its Local Strategic Partnership (LSP) articulating ‘commissioning’ as an empty signifier in its new reform to address the Government’s post-2010 austerity agenda. The research characterizes how empty signifiers become formulated by discourses, gain appeal and lose credibility, demonstrating how such ‘universal’ demands require constant work from strategically placed individuals to avoid drifting into floating signifiers, i.e. becoming disputed. The paper makes two contributions: first to our understanding of how empty signifiers lose credibility; second, via its mobilization of concepts of empty and floating signifiers within a case study, into how ‘national’ signifiers such as commissioning have been mobilized by local authorities in diverse ways since the 2008 financial crash.

Introduction

As the 2008 financial crisis commenced, a new UK Liberal Democrat-Conservative Coalition government adopted a wide-ranging array of funding reductions which saw local government lose on average 27% of their budget. Simultaneously, the concept of commissioning became mobilized by many across public, private and voluntary organizations as a lauded solution to multiple local government problems of citizen participation, budget cuts, service delivery and collaboration (Bovaird, Dickinson, and Allen Citation2012; Cabinet Office Citation2010; Coulson Citation2004; Lowndes and Pratchett Citation2012; Murray Citation2009). Although commissioning did not have an accepted definition, it referred to models of service design and delivery, bringing together ideas of collaboration with the third sector, privatization and citizen involvement (cf. page 10 for longer discussion of commissioning). Commissioning thus looked ripe to become an empty signifier, which is why I selected it to discuss the question of empty signifiers, and particularly how they lose credibility and become floating signifiers.

To address this question, I mobilize Laclauian discourse theory and its discussion of empty and floating signifiers as key tools for discourses in mobilizing consent and achieving hegemony (Howarth Citation2010; Laclau Citation2005; Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985). In the last decade, empty and floating signifiers have been the subject of a series of studies which have examined how empty signifiers are formulated and gather consent (Griggs and Howarth Citation2000, Citation2013; Jeffares Citation2008; Wullweber Citation2014). Yet, little is known about how empty signifiers lose credibility or appeal and drift into floating signifiers. Credibility is here understood in reference to Griggs and Howarth’s (Citation2000) discussion of criteria for successful empty signifiers, itself building on Laclau’s (Citation1990, 66) which argues that credible empty signifiers are those which resonate with the historicity and tradition of ‘the basic principles informing the organization of a group’. In addressing this question, it is necessary to bring in the role of actors, and more precisely strategically-placed individuals constantly rearticulating empty signifiers in order to continuously and tendentially empty these, or, alternatively, ‘letting go’ of a signifier and moving on. By answering this question, I also suggest that it is possible to critically understand how local and central government have sought to renegotiate consent and redeploy control in the post-2010 context of austerity, seizing on concepts such as commissioning to appeal simultaneously to an array of demands around collaboration, citizen participation and efficiency.

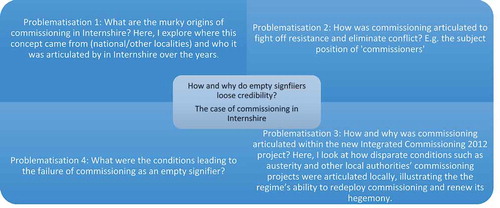

In order to analyze these questions, I deploy a logics of critical explanation framework, a five-step approach formulated by the Essex School of discourse to operationalize Laclauian discourse theory (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). A logics approach notably involves problematizing objects of study, characterizing social, political and fantasmatic logics or governing rules, of discourses, and situatedly and critically reflecting on past and present alternative practices. I deploy this framework in the case of an English County Council, anonymized as Internshire County Council and its Local Strategic Partnership (LSP), ‘Internshire Together’. From 2010, Internshire’s corporate center formulated a new project. Entitled ‘Integrated Commissioning 2012ʹ (IC 2012), this project articulated conditions such as austerity, localism, partnership disputes or Big Society as pressures, or dislocations, requiring two ‘solutions’: the ‘rationalization’ of partnerships and priorities, and the move to the vaguely defined ‘commissioning’ of services. Commissioning was a central tenet of this project, having been progressively mobilized by the corporate center from the early 2000s to appeal to demands as varied as privatization, collaboration, local delivery and outsourcing. It was argued at the time that this project would help Internshire Together remain an excellent locality, working better in ‘hard’ rather than ‘soft’ partnerships and achieving ‘more with less’ resources. Partners were for instance asked to draft ‘commissioning plans’, or planning documents outlining which three or four priorities they would work toward, how they planned to achieve them and how they would collaborate with other partnerships (known as ‘mutual asks’). Although the initial principles of IC 2012 were adopted by all partners in October 2011, by the summer of 2012, the project was a failure. This paper explains this failure by focusing on one of several conditions: commissioning and its mobilization as an empty signifier.

Based on 33 semi-structured interviews with key players, a documentary archive spanning four decades and 9 months of observations, I problematize the historical emergence and articulation of commissioning as an empty signifier. From a signifier gathering wide support, commissioning progressively occasioned mistrust and doubt among some players, leading to its abandonment by the corporate center. In this analysis, I notably focus on the role of agents in characterizing and renegotiating empty signifiers.

The paper first reviews how discourse theory discusses the question of empty and floating signifiers, highlighting current limitations regarding how empty signifiers become floating signifiers and the role of agents. Second, the logics approach and data collection tools are presented. Third, the case of Internshire and IC 2012 is analyzed, focusing on three phases of commissioning’s articulation. Finally, fourth, I discuss the findings and wider contributions to discourse theory and policy research.

Empty and floating signifiers: A review of the discursive literature

Empty and floating signifiers are primarily articulated by Laclauian discourse theory or similarly inspired research (Jones and Spicer Citation2005; Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985; Spicer and Alvesson Citation2011). Therefore, before I discuss these two concepts and their mobilization in the literature, it is important to outline some of the key tenets of discourse theory. However, as this theoretical family is complex, some aspects are overlooked (see Howarth Citation2000, Citation2013).

Discourse theory argues that reality – be it beliefs, identities, norms or objects – is not ‘real’ but is instead the product of discourse, understood as the articulation of meaning, or more specifically of demands into chains of equivalences, creating relationships between distinct elements. Phillips and Jorgensen (Citation2002, 26–7) illustrate this relationship as knots in a fishing net (also Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985, 105). For discourse theorists, reality is never fixed, suggesting that meaning remains subject to competing discourses or other nets. Thus the meaning of localism, democracy or fairness will always remain contested, even though at times they might appear set in stone, suggesting the working of powerful, or hegemonic, discourses able to fixate meaning, or at least maintain the illusion of this fixity. Hegemony is discourse theory’s conceptualization of power, always aiming to sediment meaning around selected demands. Another important concept is that of demands. Demands are at first grievances (Laclau Citation2006). For instance, an individual in a local authority may have a grievance relating to her/his lack of participation in the decision-making process or their professional title. Grievances are ever present, since individuals are conceived in discourse theory as inherently lacking, seeking fullness (e.g. happiness). Different individuals may advance different grievances across an organization, relating for example to a lack of control, a desire for more training, or increased collaboration between services. These disparate grievances become demands when articulated together by discourses into a chain of equivalence. Demands for better pay, greater decision-making power and independence may become linked together by a project/discourse as united against some common enemy such as the ‘lazy bureaucrat’, a competing organization or the Government (logic of equivalence) (Laclau Citation2006). In contrast, when mobilized according to a logic of difference, demands are articulated as equivalent or similar to other demands part of the same chain. Finally, a last aspect of discourse theory addresses the emotional question, concepts of fantasy, subject position and grip allowing to characterize how discourses appeal to individuals. The individual is understood dually: s/he occupies subject positions – e.g. woman, mother, civil servant – and is capable of acts of identification – i.e. as actor (Laclau Citation1996). Importantly for this paper, the individual is understood as lacking, his/her identity always remaining dislocated and in search of a ‘fuller’ – i.e. happier – self. In this search, s/he occupies subject positions – ‘ready-made’ identities articulated by discourses. To mobilize their consent or ‘grip’ individuals, discourses appeal to individuals’ fears and desires via ideological constructions articulating together disparate individual fears – e.g. a failing local authority being taken over by Government – and desires – e.g. a dream of an excellent organization, with all its services collaborating together – around a selected few demands, which is where empty signifiers come in.

I now wish to concentrate on the linking of disparate demands around specific ones as empty signifiers, to explore (discursive) conflicts at the local level. These are signifiers which are ‘tendentially’ emptied of meaning, representing/signifying an impossible fullness such as simultaneously excellence, stability/change, collaboration or performance in local government cases. By partially fixating meaning, empty signifiers are able to link together a vast array of demands, reducing differences and thus limiting possibilities for contestation (Laclau Citation1996, Citation2005). Research on empty signifiers has demonstrated how ‘Blackness’ (Howarth and Norval Citation1998), ‘sustainable aviation’ (Griggs and Howarth Citation2013), ‘entrepreneurship’ (Jones and Spicer Citation2005) or ‘governance’ (Offe Citation2009) have been mobilized as empty signifiers by political projects such as Aparthaid seeking hegemony. These studies emphasize how such emptying of particular signifier of specific meaning – i.e. they become ‘everything’ – to represent numerous demands can help to organize/stabilize a field of discourse and thus hegemonize it. Howarth, with Glynos (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007) and Griggs (Griggs and Howarth Citation2000, Citation2013; Howarth and Griggs Citation2006), develops five conditions for the emergence of empty signifiers based on their methodological and empirical studies (Jeffares Citation2008). First and second, a particular element of meaning must be available and credible. Is this signifier able to signify and interpellate a broad array of demands? To illustrate, reform projects such as IC 2012 will aim to signify something abstract and ambiguous such as a ‘better future’ or a ‘streamlined organization’ to ‘grip’ organizational players. A third condition relates to whether there are strategically placed individuals able to construct and articulate an empty signifier within their political project (Griggs and Howarth Citation2000). This third aspect is particularly interesting for the question of commissioning in local government. Fourth, an unequal division of power is needed for empty signifiers to accommodate multiple demands, this resulting from past hegemonic struggles. Fifth, a historical and empirical documentation of why and how a particular empty signifier emerged is necessary, a question discussed in the next section.

In this paper, empty and floating signifiers as formulated by Laclauian discourse theory are framed as central to understanding how different discourses gather consent and achieve hegemony within a given locality (Laclau Citation1996). For instance, in cases of crisis and austerity, where organizational practices (e.g. relations, identities, rules) are being overtly renegotiated, considering particular demands as empty or floating signifiers offers the possibility of critically explaining how and why such relations are being modified, concentrating notably on the power plays and beliefs surrounding the definition of those signifiers. Empty signifiers are demands ‘emptied’ of meaning to symbolize a multiplicity of contradictory demands. On the other hand, floating signifiers are signifiers which continue to see their meaning shift across context and perspectives, different demands fighting over their definition (Angouri and Glynos Citation2009, 11–12). Despite the numerous reforms taking place across local government mobilizing the same few signifiers of commissioning, partnership or localism, empty and floating signifiers have not been deployed by research as methodological tools in understanding the mechanics of these concepts (Bovaird, Dickinson, and Allen Citation2012; Coulson Citation2004; Murray Citation2009).

Based on these reviews, I believe that there is a case for analyzing in more details how empty signifiers lose credibility and become floating signifiers, and in particular considering the role of agents in such processes. Regarding Griggs and Howarth’s (Citation2000) third condition, how exactly do agents renegotiate the meaning of an empty signifier and make decisions as to its viability as a universal demand? I argue that it is necessary to explore in depth how these agents address these issues and negotiate meaning of empty signifiers over time, a quest helped by the methodological approach outlined in the next section.

A logics approach for analyzing empty and floating signifiers

In this section, I outline the logics approach of this research, notably the need to problematize signifiers such as commissioning and retroductively reflect on the fit between theory and empirical data, as well as the selection of Internshire and how the data was collected and analyzed.

Logics of critical explanation

I aimed to develop a methodological framework capable of critically analyzing the messy, contextual and conflictual negotiation of meaning in a given space, as suggested by the question of commissioning in Internshire. I needed to be able to interrogate where this concept came from, how it was negotiated and disputed over the years, and how it changed and gathered consent. These questions were addressed by a recently developed set of methods, which problematizes and characterizes the governing rules of chosen phenomena and draws on Laclauian discourse theory: logics of critical explanation (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). This five-step logics approach allows examining different dimensions of a same discourse by focusing on the social, political and fantasmatic governing rules – or logics – of a discourse. Thus this approach does not solely concentrate on ‘talk and text’ but explores the multiple ways in which discourses exercise power, analyzing the norms, actions, identities and other discursive practices they mobilize. These steps are now described.

The first step problematizes the phenomenon under study, mobilizing Foucault’s genealogy, to explore the ‘ignoble origins’ of given discourses, allowing to understand how consent is forged over time and interrogating the ‘reproduction and transformation of hegemonic orders and practices’ (Howarth Citation2000, 72–73; Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). For instance, organizational reform projects often single out ‘problems’ such as a lack of efficiency or bureaucracy. The second step (these steps are not successive but interlocking) uses retroductive explanation to make the problematized phenomenon more intelligible (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007, 19). This step implies ‘the generation or positing of hypotheses’, rather than explanation (Citation2007, 27). The third step involves three types of logics which are ‘indispensable in helping us to explain, criticize and evaluate’ problematized phenomena: social, political and fantasmatic logics. Social logics allow questioning what are the rules, values and norms in a given organization, for instance looking at ‘how things are done here’. Political logics allow characterizing how demands – identities, actions, beliefs, policies or other discursive practices – are brought in or excluded by a discourse. These can be characterized by searching for ‘us versus them’ constructions (logic of equivalence) or the building of wide alliances (logic of difference). Fantasmatic logics identify the emotive or affective dimension of discourses, examining how demands and particularly individuals’ identities, become ‘gripped’ by particular discursive practices. The fourth step of a logics approach involves articulation. This is a fundamental methodological ‘tool’ in explaining and critiquing problematized phenomena. It also implies that theoretical concepts (the ontological) and objects of study (the empirical) cannot be considered as immune from each other. Instead, both are modified by the intervention of the researcher. Fifthly, by making visible the moments of contestation, domination and excluded possibilities (i.e. the political and fantasmatic dimensions of a discourse), a logics approach offers space for a situated critique of governing discourses and hegemonic strategies such as commissioning in Internshire, highlighting possible alternatives in situ.

Selection of the case study

Internshire County Council and Internshire Together (the LSP) were selected for three key reasons. First, Internshire was formulating a reform, Integrated Commissioning 2012 (IC 2012), in a tumultuous context, thus a potential situation where conflict and the negotiation of meaning become more visible. From 2010, the UK local government and its future were being problematized by national and local discourses, echoing demands for the move to a more localized service design and delivery (the ‘localism’ agenda), the abolition of some services or the re-centralization of functions (Copus Citation2014). Furthermore, local government was overflowing with change projects, again a situation allowing to explore how change and thus power are renegotiated. Internshire was one of those articulating the need for radical change of its partnerships and service design and delivery. Second, this locality’s project of IC 2012 mobilized as one of its key demands an increasingly popular signifier: ‘commissioning’. Commissioning had been centrally mobilized since the 2000s by the Labour Government’s local government agenda, as well as by Internshire and other local authorities to link together and hegemonize contrasting organizational demands such as efficiency, performance, user empowerment, outsourcing and service closures. Hence, the centrality of this signifier in Internshire’s latest change project presented the opportunity to critically discuss empty and floating signifiers. What would be the demands articulated around commissioning? Could its varied articulations mute the local grievances that had been emerging since 2010? Finally, third, this locality was particularly suited because it was formulating a change project in an especially complex organizational context. As alluded to above, this LSP counted 27 organizations, some composed of elected members whilst others were private businesses or voluntary organizations. This case study could hence be beneficial for exploring the manufacturing of consent in overtly complex organizational contexts via empty signifiers. A preliminary exploration had also highlighted this locality’s disputed history of reorganizations and mergers, which emphasized the malleability of local frontiers and past struggles. In addition, as this locality wished for a researcher to document its reform, wide access to participants, meetings and sources was guaranteed.

This case can help inform other cases of other local communities thinking of or currently articulating commissioning as a solution to austerity, in the UK and abroad. This case is relevant because it can help highlight how particular signifiers become ceased upon and emptied in order to gather consent and reorganize control in changing times. It suggests, with its theoretical framework and research tools, how researchers may problematize and tease out hegemonic strategies at play.

Data collection and analysis

In order to capture the different dimensions of the mobilization of commissioning in Internshire, three types of data were collected. First, between November 2011 and May 2013, I conducted 33 semi-structured interviews with key players, averaging 45 min. These were transcribed and coded (more on this below). Second, I was present in the locality from September 2011 until April 2012, compiling fieldnotes and a reflective diary on the everyday practices of this organization, how things were done (social logics), how individuals and demands were organized and conflicted (political logics), as well as what were the local myths (fantasmatic logics) such as a long-standing rivalry between County and Districts. Third, Internshire documents since the 1970s were systematically compiled in an archive of different texts – from council minutes and reports to news cuttings – in order to help problematize the case (step 1) and highlight how politics worked over time (step 2).

I asked participants about their support of the project to interrogate the complex linking of demand and power plays. This data allowed me to explore the hegemonic strategies at play, or how social, political and fantasmatic logics were articulated by the corporate center in building alliances and framing enemies (step 3). Questions surrounding commissioning, its definition and emergence yielded particularly rich data which led me to hypothesize it as an empty signifier in the corporate center’s discourse. Ensuing from this, I sought to piece together how commissioning was constituted over time in Internshire, interrogating my archive. I looked at different documentary genres to characterize the different dimensions of commissioning: normalizing (social logics), linking together/excluding (political logics) and ideological (fantasmatic logics, all step 3) (Fairclough Citation1995; MacKillop Citation2014, Appendix 2).

The data were constantly reflected upon, following the problematization and retroductive steps of a logics approach. However, to summarize, the data were first coded, following the themes developed for the interview, this first step allowing to sift through a large amount of information. I looked for similarities and differences and progressively characterized key themes such as commissioning, austerity, County and Districts competition, following discourse theory’s understanding of discourse as linking together multiple demands via equivalence and difference. Then, the data were organized, formulating problematics allowing to develop the best possible explanation for the case.

Critically conceptualizing commissioning with empty and floating signifiers: the story of internshire and integrated commissioning 2012

This section articulates discourse theory within a logics approach in order to critically analyze the emergence of commissioning in Internshire, its articulation as an empty signifier, and, ultimately, its failure to mobilize consent. Before these three episodes are discussed, I briefly present Internshire and its history, following the genealogy/problematization step of a logics approach.

This is the case of ‘Internshire County Council’ and its LSP, anonymized as ‘Internshire Together’, a partnership structure (composed of 80 partnerships) created by the Blair Government in 2002. Following the problematizing step, it is argued that from the mid-1970s, this authority’s nascent corporate center, spearheaded by corporate managers and later the Chief Executive’s Department, mobilized shifting national and local demands as dislocatory conditions requiring change. Yet, between 1974 and 2010, similar solutions of corporate planning, performance management, centralization and unification were proposed, different strategies being deployed to gather consent (e.g. training, creation of sub-groups). Thus progressively, and despite changing Governments, shifting economic conditions or new organizational demands, this corporate center became and remained powerful, notably thanks to stories of efficiency and excellence, which continued to appeal to a wide array of local demands. National performance and excellence awards being granted to this locality during the late 2000s fuelled this fantasy, rendering its successes more ‘real’.

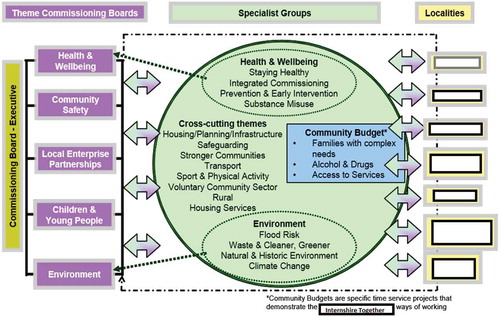

From 2010, this corporate center formulated a new project for the County Council and the partnership. Entitled ‘Integrated Commissioning 2012ʹ (IC 2012), this project articulated conditions such as austerity, localism, partnership disputes or Big Society as dislocations requiring two ‘solutions’: the integration of partnerships and priorities, and the move to the vaguely defined ‘commissioning’ of services. IC 2012’s new proposed structure is depicted in above (note the post-hierarchical horizontal structure and the renaming of groups as commissioning ones on the left). It was argued at the time that this project would help Internshire Together remain an excellent locality and achieve ‘more with less’ resources. Partners were for instance asked to draft ‘commissioning plans’, or planning documents outlining which three or four priorities they would work toward, how they planned to achieve them and how they would collaborate with other partnerships (known as ‘mutual asks’). Although the initial principles of IC 2012 were adopted by all partners in October 2011, by the summer of 2012, the project was a failure. This paper focuses on commissioning and its mobilization as an empty signifier to explain this failure (although there were additional conditions: cf. MacKillop Citation2014).

Figure 1. The adopted IC 2012 structure. Source: roadmap (Internshire County Council) 2011, 4 (The right-hand column, representing the Districts, has been anonymized).

Problematizing the murky origins of commissioning

Following step 1 of the logics approach, why was commissioning ‘chosen’ by the corporate center to form such as key part of its new project? (Problematization three, cf. below) It is necessary first to understand where this signifier came from and its fluctuating meanings (Problematization one). At the national level, commissioning had been mobilized since the Thatcher administration to open up health services to competition, with the creation of a ‘purchaser/provider split’ and the outlining of ‘GP commissioning’ (1990 NHS and Community Care Act; Compulsory Competitive Tendering policies). Between 1997 and 2010, under Labour Governments, commissioning continued to be mobilized to symbolize an ever greater array of demands, coming to mean ‘more than procurement’ (ODPM Citation2003), a ‘multi-dimensional link’ between different ‘styles’ of services (Knapp, Hardy, and Forder Citation2001, 293–94), a means of achieving ‘best value’ performance via the creation of a ‘commissioning cycle’, the recasting of local authorities into a ‘commissioning role’ (DCLG Citation2006, 109), a redefinition of ‘place’ and the reduction of costs via place-based commissioning (Lyons Citation2007, 12–20). By 2008, commissioning appeared to have ‘absorbed’ all public service activities, from design to delivery and evaluation, with the Government’s Creating Strong, Safe and Prosperous Communities guidance defining commissioning as ‘making use of all available resources without regard for whether the services are provided in-house, externally or through various forms of partnership’ (DCLG Citation2008, 49). Thus in different contexts, commissioning had been mobilized by successive Governments in redefining the role and practices of localities (Bovaird, Dickinson, and Allen Citation2012; Jones and Liddle Citation2011).

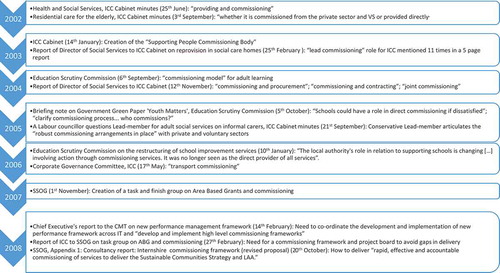

In Internshire, commissioning had been mobilized since the 1980s, in line with national policies already discussed. Although these were the first utterances, it was not until the 2000s that commissioning ‘took off’ as a central signifier in Internshire’s policy-making and organizational change, as illustrated by below, which outlines selected examples of the mobilization of commissioning between 2002 and 2008 (cf. Problematization two, above). This figure illustrates how commissioning evolved from a specific health demand in 2002, to being mobilized as a general signifier by 2008, in areas as varied as transport, education or partnership services. From 2007, commissioning was centrally mobilized by a corporate center project which sought hegemonizing meaning and practices linked to this signifier. Building on the 2006 Strong and Prosperous Communities White Paper and the anticipated budget (SSOG, 1 November 2007Footnote1), commissioning was mobilized in a new project of ‘strategic commissioning’. This project sought addressing grievances that had emerged across the partnership, demanding greater equality and inclusiveness, and thus challenging current leadership practices as too elitist and top-down.

Figure 2. Four problematizations for understanding how empty signifiers lose credibility: the case of commissioning in internshire.

Figure 3. Articulations of commissioning during the 2000s in the county council and internshire together. Source: ICC and IT minutes and report.

These grievances led to the mobilization of the new but indistinct subject positions of ‘commissioners’. Two key sets of grievances, ‘Members’ and ‘LSP partners’ were here represented. Yet, their representation is ambiguous. This depiction at the intersection between users/providers and commissioners may evoque a greater role being given to members and partners, thus addressing their grievances. But equally, one wonders why members and partners are not full ‘commissioners’’. Does this mean that these two groups are considered as part of the ‘users’ and ‘providers’ circles, respectively? That they are less powerful than other commissioners?

This new project renewed the central positions of corporate managers as ‘commissioning support’ and ‘Strategic Commissioning Unit’. It finally renewed established corporate management practices as ‘commissioning’ practices, as emphasized by the publication of a ‘Strategic Commissioning Handbook’ which was formulated by the corporate center in collaboration with a private consultancy. This Handbook defined commissioning as:

the process by which we, as a partnership, identify strategic outcomes and priorities in relation to assessed user needs, and design and secure appropriate services to deliver these outcomes. (IT, Handbook, September 2009, 2)

Here, we find the old corporate rhetoric of strategic definition of priorities, assessment of needs and appropriate (or efficient) delivery. Under the heading ‘[w]hat does [Intern]shire Together mean by strategic commissioning?’, this Handbook outlined a series of demands, linking austerity (‘reducing the public spend’), ‘place shaping’, community empowerment (‘empower the user’), joint working (‘work across organizational and service boundaries’), and efficiency (‘deliver[ing] high quality services’) to commissioning. Hence, commissioning linked together numerous demands around old corporate and performance management practices.

Commissioning was not only mobilized as a universal demand by the discourse but also needed to appeal, or ‘grip’, particular demands (Griggs and Howarth Citation2000). Participants interviewed recalled the ‘arrival’ of commissioning, and, illustrated by the multiplicity of their responses, its changing appeal across the decade. One District senior officer for instance remembered how commissioning ‘was linked to procurement. You commissioned: you procured a service that you wanted, be it by yourself or in a partnership’ (No 16). Another District participant explained how she went ‘on a course with [corporate center managers] [… in] the last couple of years’ (No 26).Footnote2 Then, commissioning echoed different demands of community empowerment (‘about an opportunity for the people to be involved in the design’ (No 26)), better services (‘creating the services that the people of [Intern]shire want’ (No 5)) and broadening service delivery (‘who provides it is irrelevant’ (No 20)). For others, commissioning had ‘always been there’, although the corporate center was now ‘trying to make it much more clinical and sort of much more defined’ (No 10; also 1; 17; 23; 26; 28; 29). Commissioning was also ‘a much broader concept’ than procurement or delivery (No 9), involving ‘pool[ing] money’ (No 22) and ‘money on the table’ (No 8; also 12).

Furthermore, a District senior officer recounted how commissioning had changed, being progressively linked to ‘this terminology, strategic commissioning’ and ‘banded about’ (No 16). Thus gradually, the term ‘bec[a]me a lot looser in terms of what does it actually mean’ (No 16) and had grown in ‘volume’ over the last ‘18 months’ (No 1, District Chief Executive). Another District Chief Executive illustrated this floating definition, stressing that, ‘[b]ack then [when the training course took place] it was strategic commissioning’, the ‘strategic’ being later on ‘dropped’ and replaced by another ‘word’, ‘integrated’ (No 26). These various articulations of commissioning as changing, losing meaning, being ‘more than’ and linking with a variety of demands illustrated how the key moves deployed by the corporate center in ‘emptying’ commissioning of specific meaning and linking it to integration. Once again, the end goal would require some group to oversee this whole-system project, renewing the position of the corporate center.

Alongside these empty and floating practices in Internshire, commissioning continued to be contested in national debates, signifying demands as diverse as personalization, community empowerment, privatization and social enterprise provision (Cabinet Office Citation2010; CLG Citation2011, 2–3). Commissioning was being mobilized by local authorities across the UK, councils rebranding themselves as ‘commissioning councils’, being defined in different localities according to different logics (Lambeth LBC Citation2010; Whitfield Citation2012), and being posited as a universal ‘solution’, a 2011 survey of ‘over 100 councils’ claiming that ‘81% of council leaders and chief executives surveyed consider[ed] taking on an even greater strategic commissioning role in the near future’ (White Citation2011, 6). These examples were discussed by participants in Internshire as impossible in the non-unitary context of Internshire Together (No 8; 13; 22), with its multiple identities and demands, the corporate center having to ‘bring everybody along’ (No 14), not ‘frighten the horses’ (No 22), and start a ‘slow revolution’ (No 8).

To summarize, commissioning had been tendentially emptied of meaning. Its emptying and multiple meanings allowed drawing together a set of contradictory demands and identities. By 2010–2011, according to participants, commissioning had ‘a hundred different meanings’ (No 23), illustrating the wide chain of equivalences that had been linked to this signifier. The hegemonic strategies deployed by the corporate center during the formulation of IC 2012 must now be discussed.

Integrated commissioning 2012: commissioning as a signifier out of control

The contents of the IC 2012 Roadmap, the central document outlining the reform adopted in October 2011, were organized around two key logics brought together by the corporate center: partnership and priorities rationalization, and the commissioning of services. The first logic of rationalization argued that, by reducing the number of partnerships from over 80 to about 30, and the number of priorities to 3 or 4, Internshire Together would be better able to deal with reduced funding and increased need (No 8; 14; 15; 22; 30). For example, the Roadmap stressed how partnerships ‘com[ing] together’ would ‘achieve more with collective resources than they [could] alone’ (Roadmap Citation2011, 8), a demand made more urgent by ‘tough financial times’ (Roadmap Citation2011, 1).

What is of more interest here is the second logic of IC 2012: commissioning, mobilized as an empty signifier, and consecrated in the Roadmap under the heading ‘What is Commissioning?’:

A common question raised in the development of this note was “what is commissioning”? At its most basic it describes a process by which we, as a partnership, identify strategic outcomes and priorities in relation to user needs, and obtain appropriate services to deliver these outcomes. Commissioning does not necessarily involve outsourcing services but instead involves considering a range of possible options including public, private and voluntary sector organisations. (Roadmap Citation2011, 9)

The openness and freedom of commissioning were highlighted here, stressing the ‘non necessary’ linking of commissioning and outsourcing and the ‘range of possible options’ offered by commissioning in satisfying varying demands. The second sentence even suggested that commissioning included the first logic of rationalization, with its identification of outcomes and priorities. Despite this declared open character of commissioning, following paragraphs of the Roadmap mobilized the work of the private consultancy in ‘develop[ing] a Strategic Commissioning Handbook’ in 2008–2009, setting out ‘our approach to joint strategic commissioning, and the expectations and practicalities’ for commissioning (Roadmap Citation2011). The Roadmap thus also sought ‘sedimenting’ commissioning, associating it to particular corporate management practices, a series of bullet points for instance summarizing the commissioning Handbook as ‘explain[ing] clearly what strategic commissioning is’, ‘the sequence of activities typically involved in doing it well’, setting out ‘the vision for what good strategic commissioning looks like’ and reproducing the commissioning cycle diagrams present in the Handbook (Roadmap Citation2011, 9–10). Despite a desire to picture commissioning as open to an array of practices, the corporate center was simultaneously reminding partners that commissioning already corresponded to practices established by the corporate center and the private consultancy they had hired.

The corporate center aimed for IC 2012 to be implemented by April 2012 at the latest. By September 2012, not all partnerships were formed nor were most commissioning plans implemented. By December 2013, the Chief Executive’s Department’s Commissioning Support team, in charge of the implementation of IC 2012 and other commissioning projects, was suspended and a key individual, the Assistant Chief Executive, took early redundancy (email exchange, 17 December 2013). Finally, in February 2014, the Leader of Internshire County Council announced a new change project of unitary authority, merging County and Districts (Source 14, 11 February 2014). It is thus possible to argue that IC 2012 was, at least in some parts, a failure (McConnell Citation2010, 36) (also No 31; 32; 33).

Even among those players remaining in the project, most of the 35 sub-partnerships developed commissioning plans according to their own demands. For instance, District plans tended to ignore the Roadmap’s recommendation of selecting three or four priorities. As the initial December 2011 deadline was missed, corporate managers ‘helped’ partners write their commissioning plans, occasioning ‘a lot of negotiation […] between the different partnerships’ (No 12; also 8). In practice, that negotiation involved corporate managers ‘look[ing] at [commissioning plans] alongside each other’ (No 12; also 13), ‘checking of the plan and making sure it was consistent with other things’ (No 12; also 3). In some cases, corporate managers even wrote the commissioning plans, asking relevant partnerships to agree a final version (No 12 and 22). This practice contradicted the ‘relatively light-touch process’ and ‘critical friend’ position of the corporate center suggested by the Roadmap (Roadmap Citation2011, 3).

The definition of commissioning plans was modified by some partnerships presenting ‘something but not quite what was expected’ (No 33). Most partners continued to do what they had done before, now ‘naming’ their strategy ‘commissioning plans’ and their practices ‘commissioning’. For instance, a partnership representative depicted how his partnership had ‘an economic growth plan’ which one could ‘interpret […] as a commissioning plan’ (No 17). A County Assistant Director added how his department had ‘a plan’ which ‘fit[ted] entirely with the view that [they] should be commissioning’ (No 2). These participants and others argued that commissioning plans were an unnecessary branding or bureaucratic exercise (e.g. No 1; 2; 26). One emphasized that her district had ‘been following that route for a long period of time’ whilst another one explained that they were ‘already doing it’ (No 26 and 15). Thus rather than IC 2012 becoming common practice, this project’s definitions were being modified and adapted to represent contradictory demands.

In summary, according to two corporate managers interviewed in autumn 2012, practice had not changed (No 31; 33). A presentation given by corporate center managers to County’s Corporate Management Team in October 2012 illustrated how the initial objective of IC 2012, ‘integrated commissioning propositions with joint use of budgets’, was only taking place in 3 out of the 35 partnerships (Crisis Meeting, 4 October 2012). This presentation added that participants linked integrated commissioning to their established practices. An analysis of County and partnership documents since September 2012 exhibited how ‘integrated commissioning’ had almost disappeared from the local policy literature (Strategic Commissioning Executive meeting, 22 November 2012, minute 114; 6 September 2012 meeting).

Commissioning: an empty signifier losing credibility

In explaining how IC 2012 failed, I now concentrate on commissioning and its progressive loss of credibility as an empty signifier (Laclau Citation1990).

At first, commissioning presented characteristics of a ‘successful’ empty signifier. Three aspects support this argument. First, commissioning appealed to an array of demands. The 33 interviews collected epitomized the multiple meanings, or practices, linked to commissioning, 317 responses being formulated when discussing the question ‘what is commissioning?’ These responses were collated into 39 themes as varied as the personalization of budgets in health (1 response) or changing relationships with communities (1 response), to more common responses such as commissioning being linked to the commissioning cycle (25 responses), to outsourcing and marketization of services (27 responses) or partnership integration and prioritization (34 responses). Specifically, themes such as commissioning as capable of dealing with issues of outcomes (17 responses), representing more than procurement (29 responses) and relating to something else than outsourcing (5 responses) illustrated how this signifier gripped the hopes of local players, symbolizing something ‘more than’ or different from outsourcing and procurement. Second, commissioning also symbolized a future still to come, once priorities and partnerships had been integrated (20). Once these steps were completed, commissioning would, for instance, allow greater trust (6), pooled budgets (5), early intervention (2), or better negotiation with providers (2). These multiple possibilities echoed the Roadmap’s own open definition of commissioning (Roadmap Citation2011, 9).

Commissioning was also identified locally with the corporate center’s own logics, with 59 responses illustrating how commissioning was linked to practices of partnership integration, priority setting and commissioning plans and the commissioning cycle (i.e. IC 2012’s own practices illustrated in the Roadmap). Commissioning was deliberately maintained as open by the corporate center, its managers emphasizing, as seen in the Roadmap, that commissioning would evolve (No 22), being ‘define[d] as [people went] along’ (No 2), with this Department helping to ‘interpret and share understanding’ (No 11). The corporate center insisted that local players ‘negotiate’ the meaning of commissioning, declaring that this definition should be a partnership exercise. Examples from other local authorities were mobilized locally in illustrating the diversity of practices that could be linked to commissioning (No 8; 12; 13; 14; 22), this signifier progressively replacing, in popularity, ‘[t]he other one that people use[d] a lot and have done for the last 10 years […] partnership’ (No 23). Some corporate managers were surprised how ‘everyone had kind of got a varying view’ on commissioning (No 8). This varying view or openness however represented a corporate center strategy to facilitate the adoption of the project by appealing to a wider array of demands, as illustrated by the following manager:

If we spent time going around speaking to people saying “this is commissioning”, I would have been going further than my Chief Executive wanted me to go. I would have lost the support of people if that’s a thing that they didn’t want to do. (No 33)

Thus commissioning was articulated ‘as a nudge’ to bring partners into thinking about their priorities and plans (No 8). For another one, ‘integration and commissioning work[ed] […] and it appeal[ed] at the same time’ (No 3). The corporate center was said to ‘try to move away from what was called the LSP […] and by using the word commissioning to make it much more focused […] instead of being a talking shop’ (No 10). In September 2012, as the project was stalling, another manager explained that ‘there [was] something necessarily fluid about that concept […] something necessarily fuzzy’ (No 33), this ‘fuzziness’ allowing one to draw equivalences between a wide array of demands, despite a context crisscrossed with grievances toward the corporate center.

Third, alongside this multiplicity and openness of commissioning, the corporate center sought re-sedimenting its old corporate and performance management logics via new control practices, which commissioning as an empty signifier dissimulated. One of them was for instance the review of all the commissioning plans (as ‘critical friends’ and ‘business partners’) (Roadmap Citation2011, 3–4). Managers from the corporate center became implicitly in charge of determining whether such documents could be called ‘commissioning plans’ (No 9). In practice, that negotiation involved corporate managers ‘look[ing] at [commissioning plans] alongside each other and […] look[ing] at what the connections [were]’ (No 12), evaluating ‘how well’ they worked and how they were ‘actually going to deliver’ (No 13), ‘checking of the plan and making sure it was consistent with other things like the Sustainable Community Strategy [strategic partnership set of priorities under labor]’ (No 12), ‘evaluation and then monitoring’ to ‘look to a plan for the next year’ (No 3). In short, the review of these plans offered the corporate center the opportunity to define each of them according to the corporate center’s own logics, subtly playing in-between the openness and particularity of commissioning.

However, from 2012, commissioning lost credibility as an empty signifier, especially with the staging of two events planned by the Roadmap: the challenge processes.Footnote3 Taking place at the beginning of February 2012, two initial challenge processes were organized for partners to discuss their commissioning plans and ‘negotiate’ where they could join up priorities (No 13; IT 2011, 6), as well as providing the corporate center with an opportunity to look at ‘information’ and partnerships’ ‘proposals’ (No 11). These events however failed to achieve the corporate center’s objectives, triggering more disputes and doubts from partners over commissioning. One of them, organized on 9 February 2012, epitomized this. Despite the corporate center controlling all aspects of this meeting, down to the seating arrangements to limit conflict, the event resulted in participants disputing what commissioning meant. One District Leader for instance thought ‘commissioning [was] different from a market led solution’ whilst a District Chief Executive suggested that where the money was, lay the ‘real commissioning’. Some participants defined commissioning as working better together, in line with the corporate center’s definition. Participants blamed the excessively mystified meaning of commissioning. For example, a District Chief Executive asked what was commissioned in an integrated way within the partnership, to which someone answered ‘health’. This led other participants to argue that example may actually be called ‘joint spending’ rather than commissioning. During the last minutes of this event, discussions became concentrated on commissioning’s meaning, a District Chief Executive warning of ‘the risk’ that partners would ‘end up thinking [they were] doing different stuff’. Where commissioning should have remained open to continue hegemonizing demands, participants were demanding particularity and clarity, a phenomenon that would worsen. As an object of conflict, commissioning was showing the first signs of becoming a floating signifier.

Corporate managers recognized that this issue was ‘something that as a partnership need[ed] to be clarified’ (No 11) and that there was a ‘problem with the word commissioning […] mean[ing] different things to different people’ (No 22; also 13). Nevertheless, no clarification or review of commissioning was formulated. It is striking that this signifier’s multiple interpretations and its difficult definition was the most articulated theme across the 33 interviews, 20 per cent of the 317 responses discussing this issue. Thus commissioning ‘seem[ed] to be an awful lot of things, from hard fast cash to […] do[ing] things more jointly’ (No 16). It represented a ‘danger’ if ‘becoming so broad that it did not mean anything’ (No 2). According to some, ‘the problem [was that] people use[d] the word commissioning and actually [were] never sure what it [was] when they talk[ed] to [each other]’ (No 23). Its lack of definition was problematic for some players who were losing confidence in commissioning to represent their demands (No 16; also 1; 2; 24). Commissioning was becoming increasingly disputed, a phenomenon understood in discourse theory as a floating signifier. A District Chief Executive explained for example that if ‘a hundred different people’ were asked, ‘a hundred different meanings’ would be given (No 23). These participants asked for ‘clarity of definition of commissioning’ (No 26; also 24). Rather than a credible empty signifier linking together different demands, commissioning was becoming a liability, hindering these players’ consenting to IC 2012, as illustrated by the following District Chief Executive:

People will always be very dubious about throwing themselves a hundred per cent into it because they are never quite sure of what it is they’re getting involved in. […] We need to strip it back to basics, about actually what it is we’re talking about when we’re talking about commissioning. (No 23)

From September 2012, corporate managers recognized that ‘people ha[d] a real problem getting their head around’ commissioning (No 31), ‘where people talk[ed] about commissioning and actually mean[t] procurement’, adding that it was ‘only [the Chief Executive’s Department] that [was] talking about it in a particular context’ (No 31). To the point where commissioning was seen as a hindrance, as illustrated by the following senior County officer:

Integrated commissioning was too abstract a concept. It wasn’t properly defined, certainly wasn’t understood and actually wasn’t that practical. (No 32)

Adding to this, a corporate manager considered that leaving commissioning without any clear definition in this late stage of implementation might have been a mistake:

I think your challenge of “is it clear?” given that people explained that it was unclear and have we sufficiently knuckled down and dealt with that, I think the answer is no and perhaps we should’ve and should’ve more. (No 33)

From the summer of 2012, a series of corporate decisions illustrated how commissioning as empty signifier for IC 2012 was being progressively abandoned, illustrating further the role of agents in articulating demands as empty or floating signifiers.

In short, commissioning had failed to remain a credible empty signifier for IC 2012, becoming instead the subject of disputes and suspicions by local players. The supposed universality of commissioning became increasingly contrasted with the particular practices that the corporate center was badging as ‘commissioning’ such as commissioning plans, the commissioning cycle, and specific priorities. This paradox between universality and particularity can sometimes remain covered over. But in the case of Internshire, other aspects of the project failed (MacKillop Citation2014, Citation2016).

Conclusion

Change in local government and the popularity of new ‘buzz words’ such as commissioning are not new phenomena. Past trends have included markets, partnerships, leadership or governance (Lowndes and Pratchett Citation2012). Consequently, the analysis of these trends – i.e. their origins, how they catch on, are disputed and lose appeal – is key. Such analyses can highlight how whole organizations – public as well as private – become enthralled to tantalizing ideas without often questioning the origins or consequences of such concepts for power relations, resources and the public. The literature has already examined similar phenomena, for instance via the concept of boundary objects (Sullivan and Williams Citation2012; Thompson Citation2015), at times mobilizing discourse (Metze Citation2008) but I wished to look at this question by deploying Laclauian concepts of empty and floating signifiers within a logics approach. This framework has helped examine in depth and critically how and why such popular ideas emerge and gain traction to the point of becoming ‘everything’.

This study demonstrates how a discursive and logics framework can add to our understanding of the power plays through meaning in organizations such as at the local government level. With its problematization step, the approach deployed here allows to analyze, in depth, the origins of such popular signifiers in situ, delving into council sources and interviewing key players to understand where commissioning came from and how it fluctuated in meaning since the 1980s, ebbing and flowing according to local demands, crises or national debates, all with the purpose of gathering consent and exercising power. Another step of this logic approach – that characterizing the social, political and fantasmatic logics at play in Internshire – also illustrates the different dimensions according to which power is yielded and consent gathered in an organization, commissioning being thus articulated to signify new rules and values (social logics) – e.g. following the commissioning cycle –, divide and make alliances (political logics) – e.g. the corporate center at the latter stage starting to exclude certain demands from commissioning –, and grip different individuals (fantasmatic logics) – e.g. with hopes of seamless collaboration and fears of austerity.

I have also highlighted how empty signifiers are central in redrawing the frontiers of a given discursive space and renegotiating consent during crisis. These signifiers help manage and link together these spaces and competing projects. Understood as particular demands tendentially emptied in order to be mobilized as universal demands, these signifiers emphasize the multiple possibilities available and signify an absent and impossible totality. Analytically, empty signifiers are crucial in understanding how alliances are built and consent is gathered across an organization. This was the case in Internshire with commissioning. Indeed, despite commissioning successfully linking together disparate demands for privatization, collaboration, social enterprise or localism in national and other local authorities’ debates, thus renewing given discourses, this signifier lost credibility in Internshire. Building on past studies (e.g. Howarth and Griggs Citation2006; Jeffares Citation2008), this research adds to current understandings of the complex and intricate processes via which signifiers are progressively emptied – thanks notably to the construction of genealogies of those signifiers. The frontier between universality and particularity must be constantly renegotiated by those seeking to hegemonize a given signifier, notably via techniques of negotiation, the articulation of demands as equivalent or different from this universal demand, and the necessary grip of the discourse’s fantasmatic narrative, or story, in covering over the contradictions between particular demands. The openness and particularity of those empty signifiers must constantly be attended to. Too much openness leading to mistrust rather than appeal, whilst too much particularity hinders the grip potentially exercised by such signifiers. This research has gone some way to document how empty signifiers lose credibility and move into a state of overdetermination and contestation of their meaning, i.e. how they become floating signifiers. Indeed, once a signifier mobilized as universal demand becomes overly identified with particular practices, the result may be one of conflict. In particular, Griggs and Howarth’s third condition for the emergence of empty signifiers (Griggs and Howarth Citation2000), regarding the agency of specific individuals in continuing to negotiate the openness and particularity of empty signifiers, was developed. In cases where the openness of empty signifiers is problematized, veering toward a floating signifier, strategically placed individuals can still continue to negotiate and influence the emerging particularities stemming from this empty signifier, developing separate new spaces and projects and dividing the negotiation of the meaning of that signifier across spaces (e.g. in the present case, how commissioning was developed in a series of new separate projects).

Overall, this paper helps actively apply discourse theory concepts to a case study and, in the case of Internshire, expose the political mechanisms and un/conscious play over meaning involved in organizing and policy-making in local government. These remarks contradict theses of implementation from the national level and what successive the UK national governments have attempted to do with English local government. If anything, this case and its analytical framework demonstrates the vivacity of local politics, making critical and detailed analyses of such phenomena even more urgent. With an extra £18 billion reductions announced for the UK local government since 2015 (Gainsbury and Neville Citation2015), localities are now facing the real prospect of whole service closures and even more stringent reorganizations. In this context, approaches such as discourse theory can offer a critical perspective as well as opportunities for situated critique, exploring excluded possibilities (e.g. in Internshire, commissioning as equal partnership or citizen involvement). As mentioned by some participants, commissioning was only a new manifestation of an old hegemonic strategy in local government, involving seizing on demands such as commissioning and articulating them as empty signifiers to appeal to as many people as possible (cf. partnership under New Labour or social enterprise and volunteering since 2010). What is thus necessary are more micro-studies exploring the cases, characterizing the strategies of hegemonies in the hope of learning from them and formulating new, more equal, alternatives.

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eleanor MacKillop

Eleanor MacKillop is a research associate in the Department of Public Health and Policy at Liverpool University where she is currently on a Wellcome Trust funded project examining the history of British health policy-making since 1948. Her interests cover government, local government, health and management problematics, mobilizing discursive and other critical approaches.

Notes

1. Apart from the Roadmap, other Internshire documents are not listed in the Bibliography as they were all anonymized (cf. MacKillop Citation2014)

2. A list of participants is provided in the Appendix.

3. There were two initial challenge processes organized in February 2012, discussing demand management and elderly services. Following the summer of 2012, a new challenge process was organized for the discussion of issues relating to 0–19 year olds.

References

- Angouri, J., and J. Glynos. 2009. “Managing Cultural Difference and Struggle in the Context of the Multinational Corporate Workplace: Solution or Symptom?” Working paper. Colchester, UK: University of Essex.

- Bovaird, T., H. Dickinson, and K. Allen. 2012. Commissioning across Government: Review of Evidence. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

- Cabinet Office. 2010. Modernising Commissioning: Increasing the Role of Charities, Social Enterprises, Mutuals and Cooperatives in Public Service Delivery – Green Paper. London: Cabinet Office.

- CLG (Communities and Local Government). 2011. Best Value Statutory Guidance. London: CLG.

- Copus, C. 2014. “’Councillors’ Perspectives on Democratic Legitimacy in English Local Government: Politics through Provision?” Urban Research & Practice 7 (2): 169–181. doi:10.1080/17535069.2014.910922.

- Coulson, A. 2004. “Local Politics, Central Power: The Future of Representative Local Government in England.” Local Government Studies 30 (4): 467–480. doi:10.1080/0300393042000318941.

- DCLG. 2008. Creating Strong, Safe and Prosperous Communities: Statutory Guidance. London: The Stationery Office.

- Department for Communities and Local Government. 2006. Strong and Prosperous Communities: The Local Government White Paper. London: DCLG.

- Fairclough, N. 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London: Longman.

- Gainsbury, S., and S. Neville. 2015. “Austerity’s £18bn Impact on Local Services.” Financial Times, July 19.

- Glynos, J., and D. Howarth. 2007. Logics of Critical Explanation in Social and Political Theory. London: Routledge.

- Griggs, S., and D. Howarth. 2000. “New Environmental Movements and Direct Action Protest: The Campaign against Manchester Airport’s Second Runway.” In Discourse Theory and Political Analysis: Identities, Hegemonies and Social Change, edited by D. Howarth, A. Norval, and Y. Stavrakakis, 52–69. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Griggs, S., and D. Howarth. 2013. The Politics of Airport Expansion in the United Kingdom. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Howarth, D. 2000. Discourse. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Howarth, D. 2010. “Power, Discourse, and Policy: Articulating a Hegemony Approach to Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 3 (3–4): 309–335. doi:10.1080/19460171003619725.

- Howarth, D. 2013. Poststructuralism and After. London: Palgrave.

- Howarth, D., and S. Griggs. 2006. “Metaphor, Catachresis and Equivalence: The Rhetoric of Freedom to Fly in the Struggle over Aviation Policy in the United Kingdom.” Policy and Society 25 (2): 23–46. doi:10.1016/S1449-4035(06)70073-X.

- Howarth, D., and A. Norval. 1998. South Africa in Transition: New Theoretical Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jeffares, S. 2008. “Why do public policy ideas catch on? Empty signifiers and flourishing neighbourhoods.” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, UK.

- Jones, C., and A. Spicer. 2005. “The Sublime Object of Entrepreneurship.” Organization 12 (2): 223–246. doi:10.1177/1350508405051189.

- Jones, M., and J. Liddle. 2011. “Implementing the UK Central Government’s Policy Agenda for Improved Third Sector Engagement: Reflecting on Issues Arising from Third Sector Commissioning Workshops.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 24 (2): 157–171. doi:10.1108/09513551111109053.

- Knapp, M., B. Hardy, and J. Forder. 2001. “Commissioning for Quality: Ten Years of Social Care Markets in England.” Journal of Social Policy 30 (2): 283–306. doi:10.1017/S0047279401006225.

- Laclau, E. 1990. New Reflections on the Revolution of Our Time. London: Verso.

- Laclau, E. 1996. Emancipation(s). London: Verso.

- Laclau, E. 2006. “Ideology and Post-Marxism.” Journal of Political Ideologies 11 (2): 103–114. doi:10.1080/13569310600687882.

- Laclau, E., and C. Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

- Laclau, E. 2005. “Populism: What’s in a Name?” In Populism and the Mirror of Democracy, edited by F. Panizza, 32–49. London: Verso.

- LBC (Lambeth London Borough Council). 2010. The Co-Operative Council - Sharing Power: A New Settlement between Citizens and the State. Lambeth: Lambeth LBC.

- Lowndes, V., and L. Pratchett. 2012. “Local Governance under the Coalition Government: Austerity, Localism and the ‘Big Society’.” Local Government Studies 38 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1080/03003930.2011.642949.

- Lyons, M. 2007. Place-Shaping: A Shared Ambition for the Future of Local Government, Executive Summary. London: The Stationery Office.

- MacKillop, E. 2014. “Understanding discourses of organization, change and leadership: An English local government case study.” Ph.D. Thesis, DeMontfort University, Leicester.

- MacKillop, E. 2016. “Emphasising the Political and Emotional Dimensions of Organisational Change Politics with Laclauian Discourse Theory.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management 11 (1): 46–66. doi:10.1108/QROM-11-2015-1334.

- McConnell, A. W. 2010. Understanding Policy Success: Rethinking Public Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Metze, T. 2008. “Keep Out of the Dairy Gateway: Boundary Work in Deliberative Governance in Wisconsin, USA.” Critical Policy Studies 2 (1): 45–71. doi:10.1080/19460171.2008.9518531.

- Murray, J. 2009. “Towards a Common Understanding of the Differences between Purchasing, Procurement and Commissioning in the UK Public Sector.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 15 (3): 198–202. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2009.03.003.

- ODPM (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister). 2003. Local Government Act 1999: Part 1 Best Value and Performance Improvement, Circular 03/2003. London: ODPM.

- Offe, C. 2009. “Governance: An ‘Empty Signifier’?” Constellations 16 (4): 550–562. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8675.2009.00570.x.

- Phillips, L., and M. Jorgensen. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London: Sage.

- Roadmap. 2011. The Integrated Commissioning Roadmap, Version 2. Internshire County Council, Internshire, October.

- Spicer, A., and M. Alvesson. 2011. “Conclusion.” In Metaphors We Lead By: Understanding Leadership in the Real World, edited by M. Alvesson and A. Spicer, 194–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sullivan, H., and P. Williams. 2012. “Exploring the Role of Objects in Managing and Mediating the Boundaries of Integration in Health and Social Care.” Journal of Health Organization and Management 26 (6): 697–712. doi:10.1108/14777261211276970.

- Thompson, E. A. J. 2015. “An Actor-Network Theory of Boundary Objects: The Multiple Misunderstandings of Crises.” Unpublished PhD Thesis, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK.

- White, L. 2011. Commission Impossible? Shaping Places Through Strategic Commissioning. London: Localis.

- Whitfield, D. 2012. “Costs and Consequences of a One Barnet Commissioning Council.” European Services Strategy. Accessed 14 January 2016. http://www.european-services-strategy.org.uk/news/2012/commissioning-council-plan-exposed/costs-and-consequences-of-commissioning-council.pdf.

- Wullweber, J. 2014. “Global Politics and Empty Signifiers: The Political Construction of High Technology.” Critical Policy Studies 9 (1): 78–96. doi:10.1080/19460171.2014.918899.

Appendix:

List of participants (anonymised)

1: DC Chief Executive, May 2012

2: ICC Senior Officer, January 2011

3: CED manager, January 2012

5: CED manager, December 2011.

8: CED manager, November 2011.

9: ICC Head of Service, February 2012.

10: CED manager, February 2012.

11: CED manager, February 2012.

12: CED manager, November 2011.

13: CED manager, February 2012.

14: CED manager, December 2011.

15: DC Chief Executive, November 2011.

16: DC Senior Officer, May 2012.

17: LEP Officer, May 2012.

20: ICC Director, February 2012.

22: CED manager, February 2012.

23: DC Chief Executive, February 2012

26: DC Chief Executive, March 2012.

28: ICC Conservative Councillor and Lead Member, February 2012.

29: Internshire Sports organisation Director, February 2012.

30: ICC Liberal Democrat Councillor and DC Leader, February 2012.

31: CED manager, October 2012.

32: ICC Senior Officer, May 2013.

33: CED manager, September 2012