ABSTRACT

Our analysis addresses innovation processes that shape public policy and the engagement of state and non-state actors in environmental management. Public sector organizations increasingly invest resources in collaborative temporary endeavors – i.e. projects – to explore new ideas and exploit the results. We analyze the environmental project portfolio of the European Commission LIFE program in Estonia for the period 2008-2018 from the viewpoint of interfaces between project teams and permanent organizations. Our analysis of project design, administration, and practices reveals that project interfaces structure opportunities for achieving technical and institutional change through temporary organizations. Adaptive strategies of actors inside projects and in the established organizational fields producse shifts in interfaces across the project life cycle. These shifts enable and constrain knowledge production and application.

Introduction

There is a wide consensus that institutional innovation is needed to respond to environmental decline and associated social pressures. In principle, incumbent actors in established policy communities as well as outsiders – actors potentially positioned to catalyze disruptive innovation – can play key roles. To these ends, short-term projects are increasingly applied to in the EU and elsewhere (Munck Af Rosenschöld and Wolf Citation2017; Sjöblom, Löfgren, and Godenhjelm Citation2013; Sjöblom and Godenhjelm Citation2009). Enthusiasm for projects stems from their potential to accelerate knowledge creation (innovation surplus) and bolster legitimacy through expanded social inclusion (democratic surplus) (Godenhjelm Citation2016).

We seek to investigate the potential contributions of projectified environmental governance – that is, expanded reliance on temporal organizations to advance policy objectives – because we identify a central tension or contradiction (Godenhjelm and Johanson Citation2018; Munck Af Rosenschöld Citation2019; Munck Af Rosenschöld and Wolf Citation2017; Tukiainen and Granqvist Citation2016). Projects need some distance, or buffering, in order to deliver new knowledge. Because micro-managing projects eliminates opportunities for creativity and fortunate accidents, knowledge discovery requires a certain amount of autonomy and remove from dominant cultures, routines, and oversight (van Buuren and Loorbach Citation2009; Kapsali Citation2011). At the same time, application of new knowledge requires a degree of embeddedness in dominant organizational structures and cultures in order to become institutionalized. If projects are poorly connected to actors and dialogs that structure existing policy communities, important knowledge generated in projects can ‘fall through the cracks’ and opportunities for durable policy change can be lost (Sjöblom, Andersson, and Skerratt Citation2016; Torre and Zuindeau Citation2009). This tension between embeddedness and autonomy leads us to focus on interfaces that structure interaction between short-term, temporal organizations (TOs) and permanent organizations (POs)

Considering the historical nature of social relations and knowledge making that structure policy processes and policy analysis, we take a critical approach to study of projects as platforms for learning and for policy change. Specifically, we advance a relational analysis of projects. We focus on interactions between established actors at the core of policy networks (Rhodes Citation2008) and localized actors — i.e. outsiders — who advance projects as part of efforts to introduce new values, new knowledge, and new interests into environmental management and policy processes. By focusing on project interfaces – mechanisms of interaction between temporal organizations (TO) and quasi-permanent organizations (PO) – we advance understanding of how projects can advance institutional change (i.e. regulative, normative, and cognitive shifts that last beyond the projects’ time horizon) through policy learning and adaptive governance (Dunlop and Radaelli Citation2013, Citation2017).

Our empirical work relies on in-depth study of the portfolio of projects in The European Commission’s ‘LIFE’ program in Estonia between 2008 and 2018. The LIFE program is the principal funding mechanism for environment and climate action in the EU with a budget of €5.5 billion for the studied period. LIFE projects support interaction across levels of social organization (national, regional, local), sectors (public, private, civil society), and knowledge domains (engineering, sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities). These projects address practical questions such as how to manage habitats of endangered species, how to create, test, and implement clean energy technologies, and how to expand public ecological literacy. We choose this portfolio of projects and the case of Estonia because, on the one hand, the LIFE program specifically expects projects to demonstrate an explorative nature by addressing a problem in a specific location in order to produce new knowledge, but on the other hand there is also an explicit expectation that projects result in institutional change that extends beyond the lifespan of the project. Estonia presents an especially suitable opportunity to study projectified environmental governance because new EU member states from Eastern enlargement in 2004 and 2007 are significant recipients of EU project funding, which aims explicitly to create positive and durable change in these countries’ public administration.Footnote1

EU-funded projects support interplay between central EU authorities, member states, and local actors. These interactions have the potential to disrupt authoritative knowledge claims and patterns of resource allocation in policy networks (Fairclough Citation2013; Forester Citation2009). Some aspects of environmental policy and management are hotly contested in Estonia, and there are tensions regarding technical practices, resource allocation, and representation in policy decision-making. The Estonian Ministry of Environment and the broader policy network is struggling to respond to fragmented and conflicting demands applied to environmental management from environmental NGOs, industry, and diverse groups of private landowners and citizens (Vihma and Toikka Citation2021). These tensions play out through the LIFE program as some actors aim to disrupt existing practices, policies, and policy networks through these projects. Our study of projects as vectors for bringing new voices, values, and ideas into policy processes can inform the wider debate on stakeholder participation in environmental governance and in shaping environmental outcomes (Varumo et al. Citation2020, Young et al. Citation2013).

We suggest that this ‘long-leash, short-leash’ problem is central to efforts to advance institutional innovation through projects (c.f. Riis, Hellström, and Wikström Citation2019). Therefore, we focus our analysis on the autonomy and the embeddedness of TOs in relation to established actors in policy fields (POs). Research focused on interfaces between TOs and POs can advance understanding of project forms, innovation, and environmental governance. As expressed by Munck Af Rosenschöld and Wolf (Citation2017, 288), ‘We identify a need to maintain a critical stance in studying innovation through projects, and we must situate projects within a broader organizational context. Rather than characterizing project forms as a distinct alternative to bureaucracies, (we) focus on relations between project forms and more permanent organizations’. We respond to this call by pursuing a critical analysis of practices at project interfaces and the challenges of advancing policy learning through projects.

Two types of projectification and institutional change

Researchers are increasinlgy focusing on questions regarding how governance arrangements can generate and respond to new information (Dryzek and Pickering Citation2019). Concepts such as experimentalist, adaptive, and agile governance describe new principles organized around distributed and relational approaches to governance (Hodge and Adams Citation2016; Mergel, Gong, and Bertot Citation2018; Sabel and Simon Citation2011; Soe and Drechsler Citation2018). While the terminology differs, each of these approaches emphasize two things: the value of learning and a focus on dynamism (i.e. adaptation and restructuring of governance).

Our interest lies in understanding if and how projectification — increased reliance on short-term organizational forms — can advance institutional change defined here in terms of policy learning. Institutions are persistent regulative, normative, and cognitive structures that enable and constrain social interaction and societal development (G. M. Hodgson Citation2006). Policy learning is a general reference to processes of shifts in narratives and discourses linked to new cultural expressions of values that support adaptation of governance arrangements (Dryzek and Pickering Citation2019) and public sector routines (Dunlop and Radaelli Citation2013, Citation2017). Institutional innovation occurs in tension with existing structures, knowledge, and practices. Incremental approaches generally build on what exists, in which case path dependency and lock-ins limit scope for novel departures, and innovation serves to reinforce dominant relations (see Citation2018 Tukiainen and Granqvist Citation2016). On rare occasions, new approaches can disrupt existing arrangements (Repetto Citation2006, Michaud Citation2019). Alternatively, a distinction is made between managerial change (‘how things are done’) and more substantial policy change (‘what is done’) (Suškevičs et al. Citation2018).

Innovation is a two-part process of creating or discovering new knowledge, and then applying it through practices, products, or policies. These two processes have distinct logics and require different types of coordination. These differences can be formulated as two ideal types of projects: mechanistic and organic (Munck Af Rosenschöld Citation2019). Weak projectification is characterized by mechanistic projects in which POs define the expectations for TOs and exert significant control (kept on a ”short leash”) over the composition of the project team, resource allocation, and the implementation of results. Under such arrangements, project interfaces curb the autonomy of TOs and allows POs to deploy projects as an implementation strategy or as a performative gesture toward curiosity and openness. As mechanistic projects have close proximity to existing organizational routines, and management structures (Boschma Citation2005), ‘out of the box’ thinking is hampered (van Buuren and Loorbach Citation2009; Kapsali Citation2011). Hence, mechanistic projects are likely to be weak vehicles for advancing transformative institutional change (Jensen, Johansson, and Löfström Citation2018; Munck Af Rosenschöld Citation2019). Public procurement projects (e.g. for building a wastewater facility) with rigid guidelines and strict reporting requirements serve as an example of this ideal type.

Under conditions of strong projectification, TOs have significant autonomy to specify their goals, organize the team, allocate resources, and specify methods and the evaluation criteria applied to project outputs. These bottom-up initiatives exhibit the logic of organic organizations (Burns and Stalker Citation1961), which have the capacity to specify problem definitions and then adapt to the task at hand. While organic projects can emerge from grassroots organizations as a challenge to dominant actors and practices, POs can launch a program of strong projectification to discover new approaches and catalyze development of new capabilities.Footnote2 However, the autonomy of organic projects and lower proximity to the established policy network (”long leash”) suggests more friction in knowledge transfer (Bakker et al. Citation2011; Wehn and Montalvo Citation2018). When a PO does not participate actively in project activities, their absorptive capacity (Song et al. Citation2018) is maladapted and new knowledge produced in projects is less likely to be institutionalized. EU’s LEADER program focused around rural economic revitalization exemplifies organic projects (Papadopoulou, Hasanagas, and Harvey Citation2011).

Project interfaces

The two ideal types of projects discussed above are distinguished by the nature of linkages between TOs and POs, which structure the origins and operations of projects. We theorize these linkages as interfaces: constituting organizational elements that enable and constrain input and output (Morris Citation1997; Sjöblom, Andersson, and Skerratt Citation2016). Interfaces structure flows of resources, such as money, knowledge, data, people, access, and legitimacy between TOs and POs. Interfaces can be composed of texts (e.g. contracts, rules, budgets, schedules, and reports), media (e.g. web-based portals, databases, archives, and surveillance mechanisms), and people (e.g. staff, auditors, liaisons, and intermediaries).

Project interfaces are relational, but these relations are generally not symmetrical due to the resources available in established policy networks. Interfaces are a key arena where collaboration and/or conflict between leaders of projects and dominant actors in policy networks plays out (O’Mahony and Bechky Citation2008). For champions of projects, a project can be an opportunity to influence and maybe even disrupt the existing institutional order. For established actors in policy networks, projects may be perceived as threats due to their potential to advance competing knowledge claims and threatens the legitimacy of established cultural conventions and practices. These ambitions and concerns are reflected in project interfaces. Interfaces can bolster the autonomy of TOs by constraining oversight by POs, and they can also allow POs to anticipate and disrupt challenges emerging from TOs. Of course, interfaces can also reflect collaboration and mutual interest in exploration and adaptation.

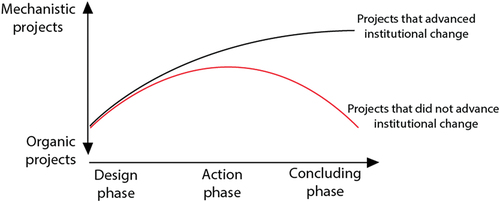

While the concept of interface is not explicitly addressed in the theory of temporal organizations (Bakker Citation2010; Jacobsson, Burström, and Wilson Citation2013; Jacobsson, Lundin, and Söderholm Citation2015), the theory defines projects through reference to a set of concepts that characterize the tensions between external (PO) and internal (TO) interests. These concepts refer to goals, methods, and evaluation criteria that structure projects. As projects can be analyzed through reference to a project lifecycle, the nature of relations between TOs and POs can shift across sequential developmental phases, and these changes are reflected in project interfaces. Typically, project phases include design, action, and conclusion (Burke and Morley Citation2016; Jacobsson, Lundin, and Söderholm Citation2015; Lundin and Söderholm Citation1995; Tukiainen and Granqvist Citation2016) (see ).

The TOs we study depend on permanent organizations (POs) as key partners in the project team and as key sources of funding (Kronsell and Mukhtar-Landgren Citation2018; Mats Citation2015; Sabel and Simon Citation2011; Soe and Drechsler Citation2018). We recognize that this treatment does not exhaust the diversity of types of TO, as grassroots organizations can rise and create societal change independently (Bakker Citation2010; Burke and Morley Citation2016). However, we analyze projects as elements of a broader organizational field and policy network. While projects can be substantially detached from or embedded in policy networks, ‘no project is an Island’ (Engwall Citation2003).

Seen through this relational lens, project interfaces are more than administrative, managerial domains. The rules and practices that structure interfaces influence innovating through projects and reflect the differential interests, power, resources, and knowledge management strategies of actors that engage projects. Interfaces may sustain the independence of TOs to explore and, sometimes, to fail. At the same time, project interfaces can allow POs to maintain control over TOs in order to align innovation activities with organizational priorities and absorptive capacity as well as to anticipate and deflect challenges. This conceptual framework position us to examine the following specific research questions:

If and how can short-term organizational forms (i.e. projects) advance institutional change in the field of environmental policy and management?

How does attention to project interfaces advance understanding of the implications of different modes of projectification — i.e. weak/mechanistic and strong/organic?

Methods for empirical study

How projects function depends on both formal design and situated social practices. For example, while a project sponsor may mandate a particular reporting protocol, actors in projects have room to maneuver and must adapt the protocols based on specific circumstances.

Accordingly, our empirical analysis relies on document analysis and qualitative data derived from personal interviews. First, we studied the LIFE program official documentation and program design. The overall aims of the program are to protect endangered species and their habitats; climate change adaptation; advancement of environmental technology and governance. Annually, national and sub-national actors (government agencies, NGOs, companies) submit project proposals. Evaluation and funding decisions are structured by formal program guidelines. Projects have budgets ranging from 0.5 to 15 million Euros and they last for 2–7 years. Funding supports collaborative engagement of diverse public and private sector actors to advance coordinated effort toward a set of specified work plans and objectives.

We then focused attention on LIFE projects in Estonia. We studied project documentation in order to understand the relevant objectives, activities, and results. There have been 39 LIFE projects in Estonia since 1992. We contacted all project managers from last 10 years (N = 17) with an invitation for a semi-structured interview. Nine of them agreed to be interviewed. The problem foci and the lead organizations of these nine projects encompass the diversity characteristic of the Estonian LIFE projects.Footnote3 We also interviewed the program administrator from the EU financing agency (1), relevant personnel within Estonian public authorities (3), project monitors (1), and consultants (1) engaged with these projects. In total, we conducted interviews with 15 people, some of them several times.

Interviews addressed 1) the inception of the project, and how the problem/opportunity was identified and developed into a project proposal; 2) development of the project team and interactions between organizations internal to the project and the broader organizational field; 3) how the project activities were implemented; 4) durable outcomes of the project including policy changes. Interviews lasted from 30 minutes to 2 hours, they were transcribed and analyzed using NVivo software. Throughout our work, we followed Cornell and Helsinki Universities’ ethical codes of conduct.Footnote4

Coding followed the theoretical framework of our study (Guest, MacQueen, and Namey Citation2012). We structured the interview data based on concepts from literature and our research questions (such as ‘project design’, ‘oversight’, ‘institutional/policy change’) and applied close reading to detect descriptive and normative passages that correspond to these themes. We then coded these passages using concepts derived from the interviews (such as ‘bottom-up design’, ‘indicator for success’, ‘continuous evaluation’). Our analytical strategy was to assess interactions between TOs and POs and how project interfaces enabled and constrained institutional change.

We collected evidence of institutional change from interviews and gray data (reports, policy briefs) because, as noted in other research done on LIFE program, standardized data on environmental outcomes of the projects is not available (Pisani et al. Citation2020). We are, however, able to detect project implications on environmental management from our data. In the following, we structured our findings according to the project phases, as this approach allows us to highlight the development and the significance of project interfaces.

Empirical findings

Designing the project: defining aims and expectations

The formal structure of the LIFE program influences the formation, structure, and orientation of the TO and its contributions to innovation. The general objectives of the program – ‘to contribute to the shift towards a resource-efficient, low-carbon, and climate-resilient economy, to the protection and improvement of the quality of the environment and to halting and reversing biodiversity loss’Footnote5 – leave the definition of specific objectives and means of achieving them to actors who develop project proposal. Local actors and NGOs outside the core policy network often play an important role in initiating LIFE proposals. Therefore, the initial project ideas are often bottom-up initiatives that respond to local conditions and interests. During the project design, because interaction with national policy actors is favored by the project selection criteria, the project-to-be draws from and builds linkages with the existing policy network. Specifically, evaluators award bonus points to proposals that demonstrate potential to be sustained after the project funds are exhausted and to realize synergies with established government programs. The EU provides 55–60% of the project budget, and the project team is responsible for securing the other funds, presumably from domestic sources including Ministries. Requiring matching funds is a direct means of ensuring that projects support interaction between civil society or commercial actors who present ideas for project proposals, and national authorities who control budgets, land, and other key resources. This co-financing approach requires cooperation and breeds inter-dependence. These dynamics play out within the project team and at the project interface where TO-PO interactions unfold.

The EU office that funds LIFE projects engages at ‘arm’s length’. It hires external evaluators to assess project proposals, local liaisons that facilitate administration, and, on occasion, external auditors. All of these experts are a good example of members of the ‘project class’ theorized by Kovach and Kucerova (Citation2006) that circulate within and across projects. These intermediaries support interaction between the funding agency, national authorities, and local actors without contributing to aims, methods or implementation of the results of projects. While templates and schedules for reporting to the funder are provided, the most important benchmark is the project proposal, which specifies project practices and the relevant accountability criteria. As represented by these arrangements, the projects enjoy substantial autonomy at their inception and in relation to the EU funding agency.

Because project proposals are comparatively lengthy and complicated documents that take months to write, the design phase can last for months, if not years. This phase includes discussing aims and objectives, identifying key stakeholders, and formalizing the required collaboration agreements. The design phase involves:

Contracting with project partners to form the temporary organization (TO)

Principles for forming the project Steering Group that supports the work of the project team and the dissemination of project outputs. This includes agreements from national authorities where project activities take place on public land or require permits.

Preliminary budgeting to identify how project partners will withdraw funds to support wages, indirect costs, and project activities

Co-finance agreements to support matching funds that complement EU investments.

In Estonia, the Ministries are quasi-indispensable partners for most LIFE projects because they control critical resources in the environmental field (e.g. data, budgets, land, and administrative authority). Although co-funding could be theoretically secured from other sources, private or corporate funding for environmental projects is virtually non-existent in Estonia. The need to secure cooperative agreements and co-financing with national authorities gives rise to cooperation and tensions. For example, TOs look to POs as a pathway for realizing and institutionalizing their innovative ideas, and POs are interested in securing access to EU funds in order to advance existing commitments. Importantly, according to program guidelines, strategies for policy learning must be specified in the design phase in order to ensure changes in national policies, regulations, and practices before the end of the project. Therefore, this is a moment when collaborative and conflictual relations between TOs and POs are expressed through formalization of the project proposal, the specification of work plans, and the administrative structure. The EU authorities describe this as balance of ‘push and pull’ factors that advance institutional change:

[In some projects] a public authority is bound by contractual agreement to carry out more ambitious conservation activities because the NGO was the driver. Money becomes the catalyzer of the push and pull exercise by the NGO. Projects allow NGOs to overcome some inherent or explicit resistance that limits ambition of the public authority. (LIFE administrator, EASME)

The program design gives rise to project interfaces that structure interactions at several levels of organization (i.e. EU, national, local). The EU does not seek a hands-on relationship with projects, which imparts an organic character to LIFE projects at the initial stage.Footnote6 However, relationships, expectations, and administrative controls between projects (TOs) and national and sub-national national POs emerge in the early design phase and become formalized in subsequent negotiations. In case of two-stage application procedure of LIFE projects, in the early design phase, the concept note of the project is approved by the EU. By the end of the design phase, the TO has written and submitted the final project proposals, signed the contracts with the Agency, and received funding. Crucially, this is the phase when the project Steering Group – a network of organizations including Ministries, national agencies, and local governments – is finalized. Once formed, members of the Steering Group actively participate in designing, developing and administering the project.

Regarding tension between implementing centrally defined goals versus targeting new problem definitions, we identify variation depending on whether the project takes place in a hotly contested policy domain. In less contentious policy domains, POs are more open to experimentation and new ideas. For example, innovation applied to the management of semi-natural habitats enjoys wide support across a broad range of actors. In the project focused on restoring coastal meadows (project #5), environmental NGOs, and university scientists approached the LIFE project as an opportunity to conceive, test and institutionalize improved grassland restoration techniques and increase the ambition in restauration volumes in Estonia. This plan was supported by local landowners, commercial firms that possessed relevant expertise and equipment, and state agencies positioned to restore and maintain grasslands after project also elsewhere (see ).

Table 1. Estonian LIFE projects under investigation, their interfaces, and institutional change.

When projects address hotly contested policy domains, such as forestry where commercial and conservation interests collide (Vihma and Toikka, Citation2021), we observed shifts in interfaces (project #1). TOs often champion disruptive ideas and express a vision in line with strong projectification at the early stage of engagement in LIFE. Over time, POs use their power to rein in TOs. As a result, weaker projectification is obtained as the projects tasks are aligned with national or organizational goals and expectations. As highlighted in the following quotation, innovative and routine goals were juxtaposed or sequenced in LIFE projects.

The more the Environmental Board came on board, the more formal and routine (the project) became. I think it is now something that could be done without a project. It is basically just an additional source of income for them. They interact with landowners and think about how to keep the forest where the flying squirrels need it./…/It may be innovative for them, but for me it has lost its attraction even though the influence of the project might be quite big in the end. If they actually come up with solutions that suit everyone and do not harm the flying squirrel, I think the influence could be very big (Project manager, projects no 2 and 4)

Note how the project manager admits that domesticating the project by finding agreeable management solution for a broad range of national policy actors both curbs innovation but may eventually result in wider implementation. Thus, interfaces based on ‘letters of agreement’ for later implementation and shared budgets allow POs to impose their ambitions and goals on projects at the design phase. Project proposals may be rejected by the Ministry and re-written for years before they are approved.

Hence, in the multi-level governance system (Hooghe and Marks Citation2001) of the EU, the European Commission seeks to fund critical and independent projects for stimulating institutional changes in order to advance reforms and harmonize policy across member states. Non-governmental and commercial actors use this opportunity to advance organic projects that seek to influence institutions in their field of interest. Estonian national regulators tend to coopt these attempts, resulting in somewhat ‘tamer’ and more mechanistic projects. But TO-PO relations and project interfaces cannot be completely reduced to strategic interplay. We observe convergence between TO and PO’s aims and expectations in the design phase, as the LIFE program funding is predicated on evidence that POs seek to learn from anticipated project results.

Project implementation: control of resources and engagement in activities

After a TO has been approved and received funding, the action phase begins with negotiating the details of activities and commitments with the Steering Group . The negotiations between the TO and POs at this stage are centered on the allocation and control over resources, attracting attention of people in a position to effect change, and dealing with unexpected developments. While TOs strive to establish their aims and course of action, because of their contribution of matching funds, POs are able to play an active role in shaping the distribution of project resources and prioritizing activities through the Steering Group .

In the implementation phase, we observed two distinct pathways for development of project interfaces. In some projects TOs and POs established stronger cooperation by successfully securing attention of high-level decision-makers within the POs, who are interested in aligning project activities and expectations with wider organizational aims. These projects were deemed ‘successful’ by participants and, analytically, these can be linked to durable institutional change. For example, a project manager (project #5) highlights how the PO’s growing engagement in the project supports efficient coordination and presents opportunities for changes in policy and practice by stating: ‘The higher-ranking person you get [to the meetings], the better it functions.’

Conversely, in other projects TOs and POs grew distant from one another as projects were ‘abandoned’ by POs. These projects were deemed ‘unsuccessful’ by participants, although this judgment was not unanimous. High-level decision makers did not participate in Steering Group meetings, express their expectations, or show interest in project results. This happened in project# 1, and partially in projects #4, 7, 8, and 9. Interviews suggest that disengagement sometimes reflect PO’s reluctance to become associated with controversial or potentially disruptive results. POs in the Steering Group also expressed concerns about the ‘burden’ of sustaining unexpected and non-conforming project results after project financing has ended. For example, in project #4, targeting environmental communication to advance conservation, it was not possible to obtain managers’ attention at the state agency, as they sought to avoid positioning themselves between empowered critical voices in the Project Team and the goals of upper-level management in the Ministry. Most notably, in project #1, when it became evident that the initially planned flying squirrel-friendly forest management techniques were not viable and an alternative course of action would be required, the TO was effectively abandoned.

What you immediately notice is the difference between [forest owners union] and [state environmental agency]. We have different ideas and speak even a different language at times. I have to be very careful how I express myself. Some issues are very sensitive, so all generalizations have to be quite careful. They are very tense and in a defensive position. /. …/But I hope that once we get the management plans done and get some interest from private owners, we could actually create a new practice out of it. This could be a service that [commercial consulting foresters] could provide to forest owners (Project manager, project # 1)

The project manager recognizes that the new forest management is unlikely to be institutionalized through policy learning by public authorities. Entrepreneurship and commercial consultancy are regarded as a path forward. This broad conception of how projects can advance institutional change and reshape governance is important. Clearly, not all shifts in management of natural resources emerge out of actions by public authorities.

Generally, POs’ control of resources and their position as gatekeepers to the wider policy network resulted in TO’s seeking to cultivate a degree of embeddedness within the POs in order to expand operating capacity and exercise wider influence. Reciprocally, engagement of POs in project activities created pathways for knowledge transfer. This kind of alignment is premised on cooperation between TOs and POs. Lundin and Söderholm’s (Citation1995) observed that projects tend to ‘guard’ themselves from outside influence in ‘planned isolation’ during the action phase. In our observations, isolation of TOs from POs occurred in policy domains characterized by contradictory expectations or conflicts. In these cases, loose project interfaces provide opportunities for TOs to experiment, however this room to maneuver comes at the expense of resources and POs’ willingness to invest in knowledge creation and learning.

Concluding the project: evaluation and continuation of results

In the concluding phase of the project interfaces focus on communicating and instiutionalizing project results. We identified two main vectors: Europe-directed and nation state-directed. From the EC side the projects are evaluated relying on benchmarks specified in the project proposal and a set of predetermined indicators by the EC. We identify weak connectivity between TOs and EU agencies. The EU funding agency provides occasional policy feedback to EU policy units based on ex post evaluations of LIFE projects, however the effect of this input on EU-level policies is unclear. Also, while LIFE projects could ostensibly trigger changes in EU Best Available Technology specifications, which inform legislative and administrative rule making, the funding agency does not have a role in this process. There are no formal linkages in place to allow projects to have direct influence on EU policies and practices.

Hence, PO-TO interfaces within individual nations shape the pathways and scope for institutional change. The EC requires that project practices continue or new knowledge is incorporated into public policies or regulations after LIFE funding ends. . In cases where the PO representative was interested in the project results, the status of the project liaison in the hierarchy of the PO influences the impact of project outputs. Projects that are able to establish a durable and high-level link to a PO have higher opportunity to influence policy learning. When the liaison has authority over the issue at hand, such as in mire conservation project (#3), project outputs resulted in update policies. In contrast, project #7 had little influence on municipal water resources management because the project and the PO project liaison failed to attract the attention of the department head of the city where the action was centered.

Projects that yielded durable institutional change featured ambitious and integrated evaluation efforts, which is consistent with participatory evaluation literature (Plummer et al. Citation2017). Personal engagement is further stressed in interviews that emphasize practice-oriented connection to civil servants as a precondition for institutional change. This is relevant both during the action and concluding phases. For example, while on-site visits of representatives of POs are time consuming and must be carefully planned, they are efficient ways to create engagement. This finding resonates with the situated and practice-based learning literature (Westberg and Polk Citation2016).

Of course, the reliance on personnel as interfaces has obvious limitations. In several interviews, project managers expressed concerns about pathways to impact because of historical conflicts within or across organizations. Additionally, respondents noted high turnover among civil servants in state agencies and general lack of adaptive capacity (Plummer and Armitage Citation2010) as factors that frustrate the ambitions of projects. It was noted that policymakers and state agencies are rarely motivated by statistics alone (e.g. declines in wildlife habitat or populations), and storing project reports in databases has low significance for policy learning.

While project managers and civil servants stressed the importance of LIFE project interfaces as a platform for catalyzing institutional change, they tended to have diverging ideas about who should learn, echoing the conflict between ambitions of TOs and interests of POs. For example, while the Ministry sees projects as helping other POs learn new practices and create new durable relationships in an expanding policy network, TOs expect the Ministry to engage in learning, as well. Therefore, in the projects we studied, direct institutional change manifests mostly as managerial change (new techniques developed and adapted by projects 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) and more seldom as more substantial policy learning (new direction or rationale for action). Only projects 3 and 5 resulted in increased ambition regarding conservation and restoration policies by the Ministry of Environment and State Forest Management, and project 8 resulted in new hazardous material policies from the Ministry of Social Affairs.

In addition to knowledge flows from TOs to POs, we identified more subtle and indirect knowledge transfer through project-to-project linkages (see Grabher (Citation2004a, Citation2004b) for similar accounts). Project managers gave accounts of visits to and from similar projects in other countries as contributing to knowledge exchange. For example, a mire restoration project from Latvia visited project #3 to discuss emerging techniques. Second, knowledge dissemination in meetings and conferences on both national and European level is both encouraged and frequent by LIFE project participants. Third, even when there is no immediate, identifiable institutional change, these organizational/professional networks potentially serve as repositories of knowledge and vectors for learning that can support future institutional change.

Discussion and conclusion

We observed how project interfaces are the terrain where cooperation, strategies, and conflict between actors engaged in LIFE projects play out. EU’s interest in advancing environmental regulation and practices in nation states is reflected in flexible interfaces that allow adaptation to local conditions. Local actors, mostly environmental NGOs, but also commercial actors and some public authorities, see the LIFE program funding as an opportunity to create disruptive change by initiating or joining a project. However, financing and implementation requirements require TOs to establish working relationships with national authorities, who tend to yoke the project to mesh with established priorities (see Munck af Rosenchöld and Wolf (2017) for a similar result in USA). Project interfaces that support embeddedness of projects into POs are pathways to institutional change. While actors engaged in projects may have different interests and theories of change, the interdependent relationships created by the project funding structure and shared interest in expanded investment in their subject area produce at least a basic level of cooperation . Interfaces in cool policy areas, domains that are not characterized by conflict, are cooperative and allow more opportunities for substantial policy learning. In hot areas, policy learning remains questionable. In such situations, when TOs are not tightly connected to POs, projects may function as vessels for experimentation and they may plug into alternative pathways for institutional change.

Our study found that project interfaces are dynamic (see ). Successful LIFE projects, those that result in durable institutional change, start with an independent, organic orientation, and, over time, become more tightly tethered to the existing policy network. Tighter connections with POs and more rigid interfaces with bureaucratic channels, reduce autonomy, but produce access to decision makers. We identify this as a process of domestication. The projects emerge as challenges to the established order, and they are animated by supra-national funds. Through a process of alignment with national authorities, the challenges/challengers are tamed. This process of domestication creates opportunities for incremental reforms, and at the same time suggests reduced likelihood of restructuring of policy networks and practices. In those cases where projects failed to produce expected results or generated outputs that contradicted the aims of incumbents in the existing policy network, POs disengaged from projects. Consequently, loose oversight and noncommittal participation of the project Steering Group diminished potential for knowledge transfer (Chen, Hsiao, and Chu Citation2014; Kang, Rhee, and Kang Citation2010).

Interdependent relationships among TOs and POs premised on harmonized objectives and shared funding are shown to yield incremental institutional change. Of course, all projects do not produce innovation, and we observe instances in which national authorities fend off challenges and potential disruption by abandoning projects that they deem unfavorable. Even in these instances where TOs are ultimately rebuffed by POs, the LIFE program provided a platform for local actors to interact with dominant actors in the policy network. n this sense, projects hold potential for advancing inclusion and stimulating debate in environmental governance. The model of projectified governance exhibited in the LIFE program can be contrasted with that of the LEADER, a large and long-running EC program focused on rural development that has been characterized as a bottom-up initiative agenda composed of projects that are largely independent from central authorities (Ray Citation2000, Papadopoulou, Hasanagas, and Harvey Citation2011). We cannot comment on how functional linkages between projects and established policy networks contribute to the LIFE program’s political support, but we can report that the EU has increased funding for the LIFE program by 60% for the period 2021–2027 to €5,45 billion. This is the largest proportional increase across all EU programs.Footnote7

Analysis of project interfaces draws attention to the role of proximity in enabling and constraining innovation through temporary endeavors. Cognitive and institutional alignment, or organizational proximity (Torre Citation2014; Torre and Zuindeau Citation2009), reduces transaction costs and supports a distributed model of production and innovation. Due to heavy reliance on projects, in some parts of the EU in some specific policy domains, public administration has become ‘porous’ as a function of deeply intruding projects (Godenhjelm, Lundin, and Sjöblom Citation2015; Mats Citation2015). This stream of critical analysis within the field of public administration highlights the potential for bureaucracies to struggle in adjusting to working with and through projects.

Securing contact with high-level administrators can allow projects to collaborate with organizations in the absence of proximity. As highlighted in our empirical material, these contacts are the result of the efforts individual members of the project Steering Group. From a structural point of view, policy innovation through projects requires that personnel at multiple levels in public agencies engage project ideas and build relationships with the project team, and this can be difficult to achieve in a bureaucratic, hierarchical organization (see Young-Hyman Citation2017). Several interfaces derive directly from program design, stressing the importance of policy input to the functioning of innovative projects (Buffart et al. Citation2020). How to integrate bureaucratic procedural controls with post-bureaucratic principles is an open puzzle (D. E. Hodgson Citation2004). Several strands of governance research address the dynamics of innovation. Within the field of public administration, innovation is often characterized as an open process of collaboration across various organizations (Bekkers & Tummers, Citation2018; de Vries, Bekkers, and Tummers Citation2014). Concepts of experimentalist, adaptive, and agile governance highlight the value of short-term projects in conceiving and testing interventions in order to inform policy and development (Hodge and Adams Citation2016; Mergel, Gong, and Bertot Citation2018; Sabel and Simon Citation2011; Soe and Drechsler Citation2018). Political actors increasingly use projects for various innovative practices (Lundin et al. Citation2015; Sjöblom, Löfgren, and Godenhjelm Citation2013). The contemporary focus on policy learning and on openness (i.e. indeterminacy) in governance regimes demands critical reflection informed by an understanding of the relational, historical, and cultural aspects of policy processes and policy analysis (Leta et al. Citation2020; Li Citation2016). As Munck Af Rosenschöld and Wolf (Citation2017) emphasize, incumbents in policy networks may seek to co-opt innovation processes to defend their privileged status and authoritative knowledge claims. As Li (Citation2016) argues, projectification normalizes underlying power imbalances. Our study validates these diverse and contradictory accounts of the significance of projects in relation to policy innovation dynamics. We argue that practice and research of institutional change through projects would benefit from focusing on interfaces between permanent bureaucracies and temporary organizations because these dynamic, relational structures shape the outcomes of project-based governance (c.f. Riis, Hellström, and Wikström Citation2019).

While our attention is focused mainly on policy learning, we recognize that public policy is not the only pathway to institutional change and improved environmental conservation. In several of the projects we investigated, institutional change emerged through engagement of commercial or academic actors, or through horizontal dissemination of professional knowledge from one temporary organization to others. As we consider shifts in policy goals through projects, in addition to studying if and how incumbents in policy networks absorb new knowledge there is value in examining how knowledge production can be cumulative through a process of ‘remembering’ across sequential temporary organizations (Grabher Citation2004a). Additionally, as we seek to critique and advance learning through projects, we should examine the ‘project class’ (Kovach and Kucerova Citation2006) – semi-autonomous consultants and intermediaries – as a potential vector for learning.

Reflecting critically on our work, we recognize that we treat projects as homogenous, fully integrated units whereas they are often complex organizations themselves. Future work must look inside projects, across the project life cycle, to understand how internal dynamics shape relations with external actors and prospects for innovation. Learning through projects remains an important area of research in innovation studies and in policy studies. Applications to policy learning and environmental conservation highlight the stakes attached to this academic and practical puzzle.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Peeter Vihma

Peeter Vihma is a PhD candidate at the Department of Sociology at the University of Helsinki University. He seeks to advance a critical analysis of how short-term projects intersect with durable policy networks to support innovation and policy learning. His latest publication used network methods to show congruence between relationships of trust and relationships of learning in Estonian forest policy and management. He is also engaged with Academy of Finland finance LONGRISK project which aims to develop a new decision-making mechanism to manage environmentally induced multi-hazard risks in urban areas.

Steven A. Wolf

Steven A. Wolf is Associate Professor in the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment at Cornell University. Through engagement with concepts from environmental sociology and heterodox economics, he studies environmental governance from an institutional perspective. Empirical engagement in US, Europe, China and India support critical analysis of feedbacks between sociotechnical change, environmental change, and policy debates.

Notes

1. Since 2005, EU sources have contributed to roughly 10% (up to 20% in 2010–2013) of Estonia’s state budget.

2. The theory of experimentalist governance is premised on incumbents in policy networks spawning potentially disruptive initiatives.

3. See https://ec.europa.eu/environment/life/project/Projects/index.cfm for the complete list of projects.

4. https://www.dfa.cornell.edu/sites/default/files/policy/vol4_6.pdf; https://www.helsinki.fi/en/research/services-for-researchers/research-ethics

5. Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/210 of 12 February 2018 on the adoption of the LIFE multiannual work programme for 2018–2020: annex.

6. This approach stands in contrast to EU Structural Funds projects that advance very tight control over aims and monitoring of activities.

7. EC press release from 13 March 2019: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_1434

References

- Bakker, R. M. 2010. “Taking Stock of Temporary Organizational Forms: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda: Temporary Organizational Forms.” International Journal of Management Reviews 12 (4): 466–486. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2010.00281.x.

- Bakker, R. M., B. Cambré, L. Korlaar, and J. Raab. 2011. “Managing the Project Learning Paradox: A Set-theoretic Approach toward Project Knowledge Transfer.” International Journal of Project Management 29 (5): 494–503. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2010.06.002.

- Bekkers, V., and L. Tummers. 2018. “Innovation in the Public Sector: Towards an Open and Collaborative Approach.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 84 (2): 209–213. doi:10.1177/0020852318761797.

- Boschma, R. 2005. “Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment.” Regional Studies 39 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1080/0034340052000320887.

- Buffart, M., G. Croidieu, P. H. Kim, and R. Bowman. 2020. “Even Winners Need to Learn: How Government Entrepreneurship Programs Can Support Innovative Ventures.” Research Policy 49 (10): 104052. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2020.104052.

- Burke, C. M., and M. J. Morley. 2016. “On Temporary Organizations: A Review, Synthesis and Research Agenda.” Human Relations 69 (6): 1235–1258. doi:10.1177/0018726715610809.

- Burns, T., and G. M. Stalker. 1961. The Management of Innovation. London: Tavistock.

- Chen, C.-J., Y.-C. Hsiao, and M.-A. Chu. 2014. “Transfer Mechanisms and Knowledge Transfer: The Cooperative Competency Perspective.” Journal of Business Research 11 2531–2541.

- de Vries, H., V. Bekkers, and L. Tummers. 2014. “Innovation in the Public Sector: A Systematic Review and Future Research.” Public Administration 320090(320090). doi:10.1111/padm.12209.

- Dryzek, John S., and Jonathan Pickering. 2019. The Politics of the Anthropocene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198809616.003.0001.

- Dunlop, C. A., and C. M. Radaelli. 2013. “Systematising Policy Learning: From Monolith to Dimensions.” Political Studies 61 (3): 599–619. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00982.x.

- Dunlop, C. A., and C. M. Radaelli. 2017. “Learning in the Bath-tub: The Micro and Macro Dimensions of the Causal Relationship between Learning and Policy Change.” Policy and Society 36 (2): 304–319. doi:10.1080/14494035.2017.1321232.

- Engwall, M. 2003. “No Project Is an Island: Linking Projects to History and Context.” Research Policy 32 (5): 789–808. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00088-4.

- Fairclough, N. 2013. “Critical Discourse Analysis and Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 7 (2): 177–197. doi:10.1080/19460171.2013.798239.

- Forester, J. 2009. Dealing with Differences: Dramas of Mediating Public Disputes. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Godenhjelm, S. 2016. Project Organisations and Governance – Processes, Actors, Actions, and Participatory Procedures. Helsinki: University of Helsinki, Department of Political and Economic Studies.

- Godenhjelm, S., and J.-E. Johanson. 2018. “The Effect of Stakeholder Inclusion on Public Sector Project Innovation.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 84 (1): 42–62. doi:10.1177/0020852315620291.

- Godenhjelm, S., R. A. Lundin, and S. Sjöblom. 2015. “Projectification in the Public Sector – The Case of the European Union.” International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 8 (2): 324–348. doi:10.1108/IJMPB-05-2014-0049.

- Grabher, G. 2004a. “Learning in Projects, Remembering in Networks?” European Urban and Regional Studies 11 (2): 103–123. doi:10.1177/0969776404041417.

- Grabher, G. 2004b. “Temporary Architectures of Learning: Knowledge Governance in Project Ecologies.” Organization Studies 25 (9): 1491–1514. doi:10.1177/0170840604047996.

- Guest, G., K. MacQueen, and E. Namey. 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. Online: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781483384436.

- Hodge, I., and W. Adams. 2016. “Short-Term Projects versus Adaptive Governance: Conflicting Demands in the Management of Ecological Restoration.” Land 5 (4): 39. doi:10.3390/land5040039.

- Hodgson, D. E. 2004. “Project Work: The Legacy of Bureaucratic Control in the Post-Bureaucratic Organization.” Organization 11 (1): 81–100. doi:10.1177/1350508404039659.

- Hodgson, G. M. 2006. “What Are Institutions?” Journal of Economic Issues 40 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/00213624.2006.11506879.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2001. “Types of Multi-Level Governance.” European Integration Online Papers 5 (11). doi:10.2139/ssrn.302786.

- Jacobsson, M., T. Burström, and T. L. Wilson. 2013. “The Role of Transition in Temporary Organizations: Linking the Temporary to the Permanent.” International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 6 (3): 576–586. doi:10.1108/IJMPB-12-2011-0081.

- Jacobsson, M., R. A. Lundin, and A. Söderholm. 2015. “Researching Projects and Theorizing Families of Temporary Organizations.” Project Management Journal 46 (October/November): 9–18. doi:10.1002/pmj.21520.

- Jensen, C., S. Johansson, and M. Löfström. 2018. “Policy Implementation in the Era of Accelerating Projectification: Synthesizing Matland’s Conflict–ambiguity Model and Research on Temporary Organizations.” Public Policy and Administration 33 (4): 447–465. doi:10.1177/0952076717702957.

- Kang, J., M. Rhee, and K. H. Kang. 2010. “Revisiting Knowledge Transfer: Effects of Knowledge Characteristics on Organizational Effort for Knowledge Transfer.” Expert Systems with Applications 37 (12): 8155–8160. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2010.05.072.

- Kapsali, M. 2011. “Systems Thinking in Innovation Project Management: A Match that Works.” International Journal of Project Management 29 (4): 396–407. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.01.003.

- Kovach, I., and E. Kucerova. 2006. “The Project Class in Central Europe: The Czech and Hungarian Cases.” Sociologia Ruralis 46 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2006.00403.x.

- Kronsell, A., and D. Mukhtar-Landgren. 2018. “Experimental Governance: The Role of Municipalities in Urban Living Labs.” European Planning Studies 26 (5): 988–1007. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1435631.

- Leta, G., G. Kelboro, K. Van Assche, T. Stellmacher, and A.-K. Hornidge. 2020. “Rhetorics and Realities of Participation: The Ethiopian Agricultural Extension System and Its Participatory Turns.” Critical Policy Studies 14 (4): 388–407. doi:10.1080/19460171.2019.1616212.

- Li, T. M. 2016. “Governing Rural Indonesia: Convergence on the Project System.” Critical Policy Studies 10 (1): 79–94. doi:10.1080/19460171.2015.1098553.

- Lundin, R. A., N. Arvidsson, T. Brady, E. Ekstedt, C. Midler, and J. Sydow. 2015. Managing and Working in Project Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lundin, R. A., and A. Söderholm. 1995. “A Theory of the Temporary Organization.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 11 (4): 437–455. doi:10.1016/0956-5221(95)00036-U.

- Mats, F. 2015. “Projectification in Swedish Municipalities. A Case of Porous Organizations.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration 19 (2). http://ojs.ub.gu.se/ojs/index.php/sjpa/article/view/3143.

- Mergel, I., Y. Gong, and J. Bertot. 2018. “Agile Government: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research.” Government Information Quarterly 35 (2): 291–298. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2018.04.003.

- Mettler, Suzanne, and Sorelle, Mallory. 2018. ”Policy Feedback Theory” In Weible, Christopher M., Sabatier, Paul A.Theories of the Policy Process, 4th Edition. New York: Routlege. 416 pages. 9780429494284

- Michaud, G. 2019. “Punctuating the Equilibrium: A Lens to Understand Energy and Environmental Policy Changes.” International Journal of Energy Research 43 (8): 3053–3057. doi:10.1002/er.4464.

- Morris, P. W. G. 1997. “Managing Project Interfaces—Key Points for Project Success.” In Project Management Handbook, edited by D. I. Cleland and W. R. King, 16–55. New York: John Wiley & Sons, . doi:10.1002/9780470172353.ch2.

- Munck Af Rosenschöld, J. 2019. “Inducing Institutional Change through Projects? Three Models of Projectified Governance.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (4): 333–344. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1606702.

- Munck Af Rosenschöld, J., and S. A. Wolf. 2017. “Toward Projectified Environmental Governance?” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (2): 273–292. doi:10.1177/0308518X16674210.

- O’Mahony, S., and B. A. Bechky. 2008. “Boundary Organizations: Enabling Collaboration among Unexpected Allies.” Administrative Science Quarterly 53 (3): 422–459. doi:10.2189/asqu.53.3.422.

- Papadopoulou, E., N. Hasanagas, and D. Harvey. 2011. “Analysis of Rural Development Policy Networks in Greece: Is LEADER Really Different?” Land Use Policy 28 (4): 663–673. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.11.005.

- Pisani, E., E. Andriollo, M. Masiero, and L. Secco. 2020. “Intermediary Organisations in Collaborative Environmental Governance: Evidence of the EU-funded LIFE Sub-programme for the Environment (LIFE-ENV).” Heliyon 6 (7): e04251. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04251.

- Plummer, R., and D. Armitage. 2010. “Integrating Perspectives on Adaptive Capacity and Environmental Governance.” In Adaptive Capacity and Environmental Governance, edited by D. Armitage and R. Plummer, 1–19. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12194-4_1.

- Plummer, R., A. Dzyundzyak, J. Baird, Ö. Bodin, D. Armitage, L. Schultz, and A. Belgrano. 2017. “How Do Environmental Governance Processes Shape Evaluation of Outcomes by Stakeholders? A Causal Pathways Approach.” PLOS ONE 12 (9): e0185375. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185375.

- Ray C. (2000). Editorial. The eu leader Programme: Rural Development Laboratory. Sociologia Ruralis, 40(2), 163–171. 10.1111/1467-9523.00138

- Repetto, R. ed. 2006. By Fits and Starts: Punctuated Equilibrium and the Dynamics of US Environmental Policy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. 2008. “Policy Network Analysis.“ In The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy, edited by Goodin, Robert E., Moran, Michael and Martin, Rein, 425–443. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Riis, E., M. M. Hellström, and K. Wikström. 2019. “Governance of Projects: Generating Value by Linking Projects with Their Permanent Organisation.” International Journal of Project Management 37 (5): 652–667. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.01.005.

- Sabel, C. F., and W. H. Simon. 2011. “Minimalism and Experimentalism in the Administrative State.” SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1600898.

- Sjöblom, S., K. Andersson, and S. Skerratt. 2016. Sustainability and Short-term Policies: Improving Governance in Spatial Policy Interventions. New York: Taylor and Francis. http://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=4468597.

- Sjöblom, S., and S. Godenhjelm. 2009. “Project Proliferation and Governance-implications for Environmental Management.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 11 (3): 169–185. doi:10.1080/15239080903033762.

- Sjöblom, S., K. Löfgren, and S. Godenhjelm. 2013. “Projectified Politics – Temporary Organisations in a Public Context.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration 17 (2): 3–12.

- Soe, R. M., and W. Drechsler. 2018. “Agile Local Governments: Experimentation before Implementation.” Government Information Quarterly 35 (2): 323–335. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2017.11.010.

- Song, Y., D. R. Gnyawali, M. K. Srivastava, and E. Asgari. 2018. “In Search of Precision in Absorptive Capacity Research: A Synthesis of the Literature and Consolidation of Findings.” Journal of Management 44 (6): 2343–2374. doi:10.1177/0149206318773861.

- Suškevičs, M., T. Hahn, R. Rodela, B. Macura, and C. Pahl-Wostl. 2018. “Learning for Social-ecological Change: A Qualitative Review of Outcomes across Empirical Literature in Natural Resource Management.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61 (7): 1085–1112. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1339594.

- Torre, A. 2014. “Proximity Relationships and Entrepreneurship: Some Reflections Based on an Applied Case Study.” Journal of Innovation Economics 14 (2): 83. doi:10.3917/jie.014.0083.

- Torre, A., and B. Zuindeau. 2009. “Proximity Economics and Environment: Assessment and Prospects.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 52 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/09640560802504613.

- Tukiainen, S., and N. Granqvist. 2016. “Temporary Organizing and Institutional Change.” Organization Studies 37 (12): 1819–1840. doi:10.1177/0170840616662683.

- van Buuren, A., and D. Loorbach. 2009. “Policy Innovation in Isolation?: Conditions for Policy Renewal by Transition Arenas and Pilot Projects.” Public Management Review 11 (3): 375–392. doi:10.1080/14719030902798289.

- Varumo, L., Paloniemi, R. and Kelemen, E. 2020. “Challenges and solutions in developing legitimate online participation for EU biodiversity and ecosystem services policies.“ Science and Public Policy 47 (4): 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scaa036

- Vihma, P., and A. Toikka. 2021. “Limits of Collaborative Governance: The Role of Inter-group Learning and Trust in the Case of the Estonian “Forest War”.” Environmental Policy and Governance 31 (1): 403–416. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/eet.1952

- Wehn, U., and C. Montalvo. 2018. “Knowledge Transfer Dynamics and Innovation: Behaviour, Interactions and Aggregated Outcomes.” Journal of Cleaner Production 171: S56–S68. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.198.

- Westberg, L., and M. Polk. 2016. “The Role of Learning in Transdisciplinary Research: Moving from a Normative Concept to an Analytical Tool through a Practice-based Approach.” Sustainability Science 11 (3): 385–397. doi:10.1007/s11625-016-0358-4.

- Young-Hyman, T. 2017. “Cooperating without Co-laboring: How Formal Organizational Power Moderates Cross-functional Interaction in Project Teams.” Administrative Science Quarterly 62 (1): 179–214. doi:10.1177/0001839216655090.

- Young, J. C., Jordan, A., Searle, K. R., Butler, A., Chapman, D. S., Simmons, P. and Watt, A. D. 2013. “Does stakeholder involvement really benefit biodiversity conservation?“ Biological Conservation 158 (February): 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.08.018.