ABSTRACT

This article contributes to the literature on environmental policy controversies. We utilize an Argumentative Discourse Analysis (ADA)-based approachto analyze the struggle for discursive hegemony that took place between competing story-lines in the context of the acid mine drainage (AMD) environmental policy problem, located in the gold mining areas of greater Johannesburg, South Africa. With this article we make a theoretical contribution by presenting and applying an adapted ADA framework strongly focused on the operationalization of key ADA concepts. Our empirical contribution lies in providing a rich and deep analysis of an environmental policy controversy that has not yet been studied from an ADA perspective. In particular, we demonstrate and discuss the complex path to discourse institutionalization followed by the dominant emergent AMD story-line. In conclusion , we recommend steps for updating the ADA approach and developing an accompanying set of guidelines to further enable the operationalization of its concepts.

Introduction

Modern environmental policy controversies are characterized by complex cause and effect chains (Feindt and Oels Citation2005) and political and scientific complexity (Keller Citation2009). Contestation typically centers on tensions arising from conflicting framings of the problem (Dodge and Metze Citation2017), which contributes to the emergence of opposing story-lines that compete to influence potential policy solutions (Hajer Citation1995; Feindt and Oels Citation2005).

A stimulating example of an environmental policy controversy is the contentious acid mine drainage (AMD) problem, set in the Witwatersrand’s gold mining areas of the greater Johannesburg region of South Africa. Following the dwindling of South Africa’s remarkable gold reserves, which once made up 50% of the world’s gold production, the cessation of much of the area’s gold mining activities resulted in massive acidic mining water discharges from abandoned mine shafts on the West Rand from August 2002 onwards. This soon presented a considerable threat to environmental, animal and human health (Funke, Nienaber, and Gioia Citation2012; Bobbins Citation2015). Over time, competing narratives emerged amongst key role-players in reaction to the AMD problem, characterized by different stances on the cause and who is to blame, the severity of its observed and potential impacts, the urgency with which it should be addressed and how it should be managed.

From the perspective of in-depth case study research, we argue that the AMD case, characterized by both powerful and interesting ‘text’ and ‘practice’ elements, is ideally suited to an analysis using the Argumentative Discourse Analysis (ADA) approach. This approach investigates the influence of discourses on socio-political practices, structures and institutions and vice versa when analyzing the struggle for discursive hegemony between competing story-lines (Hajer Citation1995). Over time, the ADA approach has proven itself as a powerful heuristic approach to understanding why a particular interpretation of an environmental policy controversy becomes embedded in policy approaches, and by so doing achieves discursive hegemony, while other interpretations are discredited (Asayama and Ishii Citation2017).

According to Yin (Citation2018), a critical case is critical to testing the theory and theoretical propositions one wishes to apply. After conducting the case study analysis, the researcher can determine whether the theory’s assumptions hold or whether an alternative set of explanations may be more relevant, thereby confirming, challenging, or extending the theory. In line with this classification, we argue that the AMD policy controversy can be used as a critical case using the ADA and its associated assumptions. An in-depth analysis is merited given the richness of the emergent narratives, the stark divergence of opinions about the AMD problem’s perceived severity, and the complex dynamics marking the path to dominance of one proposed policy solution over others.

Based on this contextual background, our research questions are as follows:

Who were the competing knowledge coalitions that mobilized in response to the AMD environmental policy problem over time, and what are the different story-lines they adhered to?

Did any of the story-lines emerge as discursively hegemonic by fulfilling Hajer’s (Citation2005) criteria of discourse structuration and discourse institutionalization?

If so, how can this discursive hegemony be explained?

We begin our article with a summary of the key arguments and assumptions underpinning the Interpretive Policy Analysis (IPA) tradition and explain our article’s contribution to it. We then proceed to presenting our analytical framework before summarizing the data and methods used. This is followed by an overview of the AMD case and addressing the first research question through a discussion and linguistic analysis of the two emergent competing story-lines we were able to identify. We then proceed to addressing the second and third research questions by analyzing the struggle for discursive hegemony that took place between the story-lines. In conclusion we reflect on the learning and significance of this article’s contribution and suggest a way forward.

Situating our analysis within the IPA tradition

Policy analysts, governments and other relevant actors are increasingly being faced with the limitations of tools and approaches that are based in naturalism, which is accompanied by a rigid separation of facts and values (Glynos, Howarth, Norval, and Speed Citation2009). Naturalistic approaches have been criticized for their lack of recognition of the argumentative progressions, political values and power relations underlying policy development processes (Bartels, Wagenaar, and Li Citation2020), therefore making it difficult to provide substantive accounts of such processes (Glynos et al. Citation2009).

IPA aims to address these shortcomings by contributing a set of approaches which focuses on the contingency and holistic complexity of the meanings that make up social reality (Bevir and Blakely Citation2018). A key assumption of these approaches is that researchers cannot remain objectively removed from the analyses they conduct, but actively participate in them as meaning-makers (Yanow Citation2007). While the number and types of approaches that have emerged under the IPA umbrella are varied and complex (Glynos et al. Citation2009), making it impossible to speak of a unified field guided by a single theoretical perspective (Bevir and Blakely Citation2018; Bartels et al. Citation2020), they are nonetheless united by their rejection of mainstream positivist models of policy analysis (Glynos et al. Citation2009; Bevir and Blakely Citation2018).

One of the main types of IPA approaches focuses on language or discourse with the aim of critically explaining the initiation, formation, implementation and evaluation of public policies (Glynos et al. Citation2009). Based on the work of Michel Foucault, Hajer (Citation1995, 44) defines discourse as ‘an ensemble of notions, ideas, concepts and categorizations through which meaning is allocated to social and physical phenomena, and which is produced and reproduced in an identifiable set of practices’ (Hajer Citation1995, 44). Given their ability to influence reality and to be shaped by it in return, discourses can therefore determine which suggested policy solution is deemed acceptable, and which is rejected (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002). It is precisely this struggle for discursive hegemony which our chosen theoretical approach, ADA, aims to explain (Hajer Citation1995, Citation2005).

Our contribution to IPA is two-fold. Firstly, we make a theoretical contribution by improving the methodological rigor and user-friendliness of ADA, one of IPA’s key analytical tools. Based on an extensive review of existing ADA applications, we have developed a detailed analytical framework explaining how to combine and operationalize the full suite of concepts proposed by Hajer (Citation1995, Citation2005). Such a detailed framework is necessary because while Hajer (Citation1995, Citation2005) provides several useful concepts (for example story-lines) in his ADA approach, he does not provide clear guidelines for operationalizing these concepts (for instance, how to construct a story-line) (Nielsen Citation2016; Van Ostaijen Citation2017). The need for a more detailed framework is also supported by Ramcilovic-Suominen and Nathan (Citation2020) who argue that clearer directions are needed for analyzing the complexity of contextual factors that determine how and why certain story-lines, discourses and discourse coalitions prevail.

Secondly, we make an empirical contribution by presenting a richer understanding of the complex AMD problem which has not yet been studied from an ADA perspective, thereby shedding light on important elements of the problem that might previously have gone unexplained. Analyzing the AMD problem from a ‘discourse in practice’ perspective yields insights about the power dynamics shaping the discursive struggle between competing perspectives, which other more positivist modes of analysis simply cannot (Bevir and Blakely Citation2018). Our application of ADA is also expected to determine which aspects of the case can be explained by its theoretical assumptions and which aspects require alternative or additional explanations (Yin Citation2018). Some of our analytical insights may also prove relevant for other country contexts where AMD has caused substantial damage to water bodies, including the United States, Patagonia, Chile, Papua New Guinea and Spain (Tuffnell Citation2017).

In addition, our analysis augments a handful of other ADA applications focused on environmental policy controversies in the South African context, namely the shale gas controversy (Gommeh, Dijstelbloem, and Metze Citation2021); renewable energy policy (Rennkamp Haunss, Wongsa, and Casamadrid Citation2017); national coastal policy (Colenbrander Citation2019) and co-management and conservation efforts on South Africa’s Wild Coast (Masterson, Spierenburg, and Tengö Citation2019). Gommeh et al. (Citation2021) and Rennkamp et al. (Citation2017) make valuable theoretical contributions, while Colenbrander (Citation2019) and Masterson et al. (Citation2019) both come to interesting empirical conclusions. Specifically, Masterson et al. (Citation2019) demonstrate the unexpected dominance of a seemingly less influential narrative over an apparently powerful and well-resourced narrative. Our contribution to this collection of ADA applications lies in our comprehensive analytical framework, which, in combination with our rich case study, has enabled us to come to deeper explanatory insights on why discursive hegemony is achieved. This can offer additional clarifications to findings such as those of Masterson et al. (Citation2019), both in the South African context and beyond.

Analytical framework: presenting our enriched version of Hajer’s ADA

This section presents the different components of our ADA-based approach and explains how they fit together into a coherent analytical framework.

Story-lines

One of ADA’s key analytical concepts that simultaneously simplifies and operationalizes discourses is that of story-lines, which, according to Hajer (Citation1995), summarize complex narratives by combining contributions from many different domains to produce meaningful and compelling accounts of a policy issue with a view to achieving problem closure. While we specifically focus on the scientific arguments embedded in the emergent AMD story-lines, we also emphasize the issue’s social and economic impacts, as well as arguments around liability and financing.

Following Hajer (Citation1995), we argue that it is especially important to analyze how knowledge providers made use of rhetorical and discursive strategies to persuade and influence their audience (Van Ostaijen Citation2017). According to Hajer (Citation1995), examples of rhetorical devices include metaphors (a figure of speech that suggests resemblance between essentially unrelated phenomena) (Lakoff Citation1993), emblems (a single evocative picture that if mentioned can invoke the gist of an entire story-line) (Arnoldussen Citation2016) and characters such as victims (someone suffering from harm), villains (someone causing harm) and heroes (someone attempting to fix or prevent harm) (Hajer Citation1995; Kroepsch Citation2016). Examples of discursive strategies include the de-legitimation of opposition coalition actors by belittling them and their institutions (Dodge Citation2017) and/or labeling them as standing in the way of future progress (Atkins Citation2019).

Regarding the strategic use of language in the context of story-lines, we follow Bomberg (Citation2017), who has elaborated on Hajer’s (Citation1995) criteria of credibility (which she refers to as plausibility), acceptability and trust, as core elements of the argumentative game (Hajer Citation1995). Firstly, Bomberg (Citation2017) states that powerful story-lines are plausible, backed up by compelling claims (Hajer Citation1995). Secondly, Bomberg (Citation2017) states that for story-lines to be acceptable, they must appear attractive and necessary (Hajer Citation1995) to the audience they are targeting. Thirdly, according to Bomberg (Citation2017), story-lines need to inspire trust in their underlying claims, while simultaneously de-bunking counter claims from opposing knowledge coalitions.

Knowledge coalitions

In addition, it is important to establish who contributed to and made use of the different story-lines that emerged in the context of the AMD problem. Hajer (Citation2005) defines discourse coalitions as ‘a group of actors, that in the context of an identifiable set of practices, shares the usage of a particular set of story-lines over a particular period of time’. Given the focus of our article on the role of scientific knowledge and by implication the scientists who produce it, we have chosen to complement Hajer’s discourse coalition concept with that of knowledge coalitions, a term coined by Van Buuren and Edelenbos (Citation2004) and later adopted by Kurki, Takala, and Vinnari (Citation2016). The concept of knowledge coalitions who play off knowledge claims against each other through the strategic use of argumentation also includes details about coalition members, namely knowledge providers (e.g. researchers, consultants and advisors) and knowledge users (e.g. policy-makers, interest groups and citizens) (Van Buuren and Edelenbos Citation2004; Kurki et al. Citation2016). We furthermore consider how agency, or the ‘capacity to act’ by agents or actors (Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy Citation2015) in the AMD policy controversy, was distributed within the knowledge coalitions both in a vertical manner and in a horizontal manner across the coalition members.

Institutional context and resources

In accordance with ADA, we also analyze the context of existing institutional practices within which discursive struggles between competing knowledge coalitions are situated, and which may enable certain perspectives to become more influential than others (Hajer Citation1995). According to Orhan (Citation2006), the domain of institutions can be defined as the political, bureaucratic and legal arrangements that govern and shape the policy process, while also embodying the rules that govern the values, norms and views of the world. Institutions therefore determine what governments and societies deem legitimate and correct (Orhan Citation2006). While a multitude of institutional practices characterizes water resources management in South Africa, for the purposes of this article, we restrict our focus to the official government-led process to identify, develop and implement an intervention to the AMD problem.

In addition, following Kaufmann, Mees, Liefferink, and Crabbé (Citation2016), we focus on the influence of resources, such as financial resources, expertise, support from government or access to the media, which can enable certain framings to become more powerful than others (Kaufmann et al. Citation2016).

Discursive hegemony

To analyze the potential discursive hegemony of one story-line over another in the AMD case, we employ the criteria of discourse structuration and institutionalization. According to Hajer’s (Citation2005, 303) ‘two step procedure for measuring the influence of a discourse’, both of these criteria need to be met for a discourse (or in our case story-line) to become hegemonic. According to Hajer (Citation2005), discourse structuration takes place when a ‘discourse starts to dominate the way a social unit (a policy domain, a firm, a society – all depending on the research question) conceptualizes the world’. If the same discourse furthermore solidifies in institutional arrangements (Hajer Citation2005), then discourse institutionalization has taken place.

Assembling the elements of the analytical framework

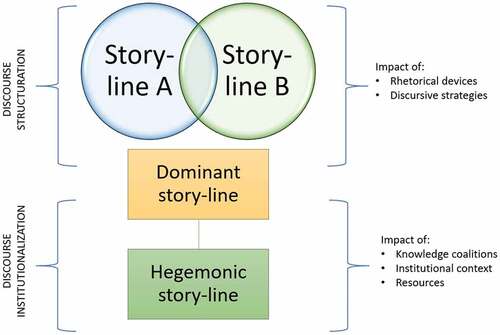

In assembling the story-lines we pay particular attention to the use and impact of rhetorical devices and discursive strategies. For our discussion of the struggle for discursive hegemony, we focus on evidence of discourse structuration and discourse institutionalization, the role of competing knowledge coalitions, and the influence of institutional context and resources (see ).

Figure 1. ADA-based analytical framework (adapted from Dang, Turnhout, and Arts Citation2012).

Data and methods

Data collection for this article consisted of a literature search and 19 semi-structured interviews with key actors involved in the AMD policy problem. We searched for literature between August 2002 and September 2018 using the search terms (‘AMD’ OR ‘acid mine drainage’) AND (‘South Africa’) on the Google, Google Scholar, SACat, EBSCOhost and Scopus databases. We selected sources discussing and analyzing different elements of the AMD issue and that were comprehensible to a generalist audience (particularly in the case of peer-reviewed articles and technical reports). These included media reports, popular articles, transcripts of a South African investigative television program, technical reports, academic articles, policy documents, official communications detailing the South African government’s official response to the AMD problem, and the transcripts of Parliamentary Portfolio Committee hearings on the AMD problem.

The 19 semi-structured interviews complemented the data assimilated from the literature search as they contained respondents’ first-hand narrative accounts of the contribution of experts to the AMD policy domain. Such accounts constituted a key input to our construction of the emergent AMD story-lines. The interview questions focused on the roles of experts in developments in the AMD policy domain; actors’ collaboration with experts; the existence and degree of influence of different proposed technical solutions to the AMD problem; different beliefs about the AMD issue; the nature and extent of coalition formation, activity and cross-coalition interaction; and actors’ views on the government’s response to the AMD problem. The interviews were conducted face-to-face or telephonically and were held with government officials from two government departments, a representative of a state-owned water treatment implementation agency, a representative of a mining company, academics, scientists, consultants and environmental activists. All interviews were voice recorded and transcribed.

The literature and interview data were consolidated and analyzed using the cross-sectional code and retrieve method, which involves identifying and describing key themes and sub-themes (Spencer, Ritchie, and O’Connor Citation2003). The themes identified were problem definition and causal interpretations, the potential impacts of the AMD problem on society and the environment, different management options to resolve the problem, apportionment of liability and financing the implementation of the long-term AMD intervention.

We subsequently molded these descriptive thematic accounts into the emergent story-lines which we extracted and assembled from the data at hand to examine if one of them emerged as hegemonic. We did so following Hajer’s (Citation2005) statement that story-lines are not self-evident but need to be constructed by researchers through an analytical process. Informed by other ADA applications, we chose to construct the AMD story-lines, as presented in the Analysis section, according to plotlines, consisting of a beginning: problem definition and causal interpretation, middle: potential impacts of the problem on society and the environment, and end: management options to solve the problem (Keller Citation2009; Williams and Sovacool Citation2019).

Case study application

Background: AMD – The City of Gold’s toxic mining legacy

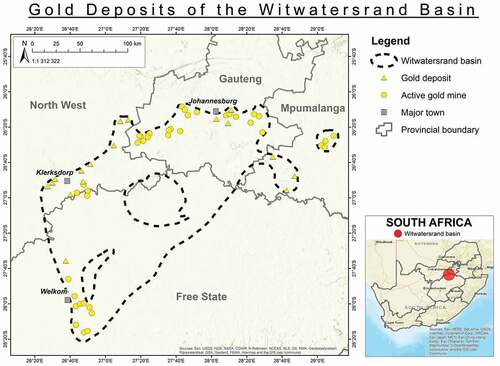

The setting of our case study is the Witwatersrand’s gold mining areas of the greater Johannesburg region of South Africa (see ). While operational, the once prolific gold mines in this area pumped water to the surface to enable them to access underground gold deposits, but when dwindling gold reserves resulted in the cessation of much of the gold mining operations in the late 1990s, the underground voids started refilling with groundwater. From a hydrogeological perspective, this rising groundwater interacts with exposed sulfide bearing minerals in the rock formations to form AMD, characterized by a low pH and a very high concentration of dissolved metals and sulfate salts (Team of Experts Citation2010). AMD subsequently began discharging from abandoned underground gold mine workings close to Krugersdorp on the West Rand in August 2002 at an average of 15 to 20 mega liters (ML) per day (Team of Experts Citation2010).

Figure 2. Simplified geological map of the Witwatersrand Basin depicting the location of the primary gold deposits, active gold mines and major towns (Council for Geoscience Citation2017).

The Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF), as the government department tasked with responding to the AMD problem by the South African Presidency, tried to bring the AMD discharge on the West Rand under control, but only managed to implement ad hoc pump and treat methods together with some of the mining companies between 2005 and 2010 (Bobbins Citation2015). Although DWAF issued a series of directives to the Rand Uranium mining company to pump water from affected mine shafts, these were successfully appealed in courts of law and could ultimately not be enforced (Bobbins Citation2015; Strydom; Funke, and Hobbs Citation2016).

In 2010, once underground gold mining on the Witwatersrand had almost completely ceased, the realization dawned that underground water levels were also rising in the Central and Eastern Basins, but with much uncertainty about the dates, volumes, locations and potential impacts of the inevitable uncontrolled AMD discharge (DWA Citation2013a). In response, the South African government began adopting a more structured and systematic response to identifying, developing and implementing an intervention to the AMD problem. The Inter-Ministerial Committee on AMD was set up by the Executive branch of government in July 2010. This was followed by the appointment of the Expert Team of the Inter-ministerial Committee on AMD (hereafter referred to as the Team of Experts), consisting of prominent experts from state affiliated institutions and government representatives, which was instructed to develop a proposed short-term intervention to the AMD problem (Bobbins Citation2015).

As short-term AMD treatment, the team proposed a combination of improved pumping facilities and neutralizing the acidic mine water through high density sludgeFootnote1 (HDS) treatment (Team of Experts Citation2010), which the government began implementing in April 2011. In January 2012, the Department of Water Affairs (DWA), having changed its name from DWAF in 2009, appointed the consulting firm Aurecon to commence with a feasibility study to determine options for a long-term intervention to the AMD problem. Upon completion of the study, Aurecon recommended the construction of reverse osmosisFootnote2 (RO) treatment plants as reference projects in the three basins (DWA Citation2013b) against which other potentially suitable long-term AMD treatment technologies would be tested. The Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS), previously DWA, officially included this recommendation in the official policy response to the AMD problem, which was announced in mid-2016. By September 2018, short-term HDS treatment plants were running successfully in all three basins (TCTA Citation2018) (see ).

Figure 3. Timeline of events (based on information from Strydom et al. Citation2016).

Analysis

The ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line

The ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line, which emerged between 2009 and 2013, centered on adopting a pragmatic explanation regarding the cause of the AMD problem and who should be held liable, the severity of its impacts, the imminence and seriousness of the impending AMD discharges in the Central and Eastern Basins and the implementation of a low risk, tried and tested long-term management intervention. In addition, the story-line held that the long-term intervention should not be financed by the mining sector alone.

Knowledge coalition

Knowledge providers to this story-line included the government affiliated scientists and private consultants that were tasked with developing the short-term and long-term AMD interventions, scientists that had participated as advisors and/or stakeholders in the development of the government’s proposed AMD solutions, representatives of the gold mining sector, and analysts interpreting the AMD issue. Knowledge users included the South African government, an environmental activist and the authors, readers and viewers of the many media exposés that brought attention to the AMD issue, particularly in the period between 2009 and 2013.

The beginning: causal interpretation

From the rather pragmatic point of view of the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line, the AMD problem was framed as a legacy issue brought on by 120 years of gold mining (Staff Staff Reporter Citation2010) for which one cannot hold the already financially constrained ‘last men standing’ (Prinsloo Citation2009), who had taken over mining operations from previously operating companies, solely accountable.

Drawing form historical knowledge, geologist Terence McCarthy (Citation2010) explained that the 1880s saw the start of more than a century of easy profits made by the gold mining industry in the so-called City of Gold. This resulted in spectacular wealth creation for some companies and shareholders, considerable revenue collection for the government through taxation of mining companies, and growth and development of infrastructure and transport routes across South Africa. Not only was gold mining very profitable, but also carried few financial risks for mining bosses as the government exonerated them from remediating any social or economic damage caused by their activities. Several knowledge providers have called this practice the ‘externalization of costs’ (Bega Citation2009; Bobbins Citation2015).

However, so the story-line continues, following a decline in mining profits from the 1950s and subsequent mine closures, groundwater began accumulating in the underground mine shafts of closed mines and flowing into neighboring mines. Consequently, still active mines were forced to take up the pumping responsibility of mines that had closed, which raised their costs and in turn contributed to their closure. With the closure of an increasing number of mines, less and less pumping took place and AMD started rising to the surface at an increasing rate, culminating in the AMD discharge on the West Rand in August 2002 (DWA Citation2013a; Bobbins Citation2015).

Middle: potential impacts of the problem on society and the environment

Knowledge provider and environmental activist Mariette Liefferink has described AMD in strong emblematic terms as the ‘single most significant threat to South Africa’s environment’ (Naidoo Citation2009), while political scientist Anthony Turton has called it ‘South Africa’s own Chernobyl’ (Sunday Independent Citation2011), leaving no doubt as to the perceived severity of its impacts. Another component of the framing of this story-line is the longevity of the environmental impacts of AMD, which ‘can take centuries to reverse, if at all’ (Respondent 4).

Throughout the government’s process of developing the short-term and long-term AMD interventions, Liefferink, on the basis of environmental, economic, cultural and human health-based knowledge claims, emphasized the severe environmental and socio-economic impacts caused by AMD. These included ‘surface and groundwater pollution, soil degradation, destruction of aquatic habitats’ and the seepage of heavy metals into the environment (Costella Citation2012). Such impacts were expected to pose substantial risks for domestic, industrial and agricultural water users (Bobbins Citation2015), health risks, such as increased rates of cancer (Bega Citation2009), and potential risks to the paleoanthropological World Heritage Site, the Cradle of Humankind (Bega Citation2010a).

At the same time, Liefferink worked to defend the credibility of her views and instill trust in her arguments, stating that the adverse impacts of AMD had been ‘proven’ and were not ‘fanciful opinion’, thereby invoking the scientific authority of her claims (Bega Citation2010b).

Another important theme that formed part of this story-line was the impact of AMD discharges on the Vaal River System, which supplies water to South Africa’s economic hub, the densely populated province of Gauteng. The authors of the recommendation reports for both interventions, dated 2010 and 2013 respectively, stated that the high salt load of an untreated or even partially treated AMD discharge requires large dilution releases from the Vaal Dam, thereby threatening assurance of supply from the Integrated Vaal River System (Team of Experts Citation2010); (DWA Citation2013a).

Arguably the most controversial component of the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line focused on the imminence and severity of the impending AMD discharges in the Central and Eastern Basins, a topic under heavy discussion from approximately 2009 to 2013, with McCarthy likening the relentless progress of the rising mine water levels to ‘watching the hand of a clock move’ (Bega Citation2010c). Despite the strong scientific and technical knowledge underpinnings of this theme, considerable scientific uncertainty existed about the exact dates and locations of the expected discharges, which were adjusted over time as more information became available. The short-term intervention report finalized in December 2010, stated that the water level in the Central Basin was rising at an average rate of 0.59 meters per day since July 2009, and that it would reach the surface by March 2013 (Team of Experts Citation2010). By July 2013, the consultants running the long-term intervention feasibility study had adjusted the predicted date for discharge in the Central Basin to the second half of 2015, and to late 2016 for the Eastern Basin, and stated that the AMD discharge in the Central and Eastern Basins would likely occur at several identified and unexpected points (DWA Citation2013a).

Despite this uncertainty, knowledge providers to this story-line agreed that the expected potential impacts of the impending discharges, when they occurred, were likely to be sufficiently severe to warrant immediate preventative action. In November 2010 a scientist contributing to this story-line predicted, in almost apocalyptic terms, that rising AMD levels in the Central Basin, on which Johannesburg is situated, could amount to the equivalent of ‘water from 24 Olympic pools’ or 60 million liters ‘hitting the city’s streets daily’ (Kardas-Nelson Citation2010). Some of the more dramatic consequences that were predicted included the corrosion of the foundations of certain buildings in Johannesburg’s city center (Team of Experts Citation2010) and damage to electricity cables situated in underground tunnels that could ‘plunge the city into darkness’ (Bega Citation2010c).

The end: management options

The ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line emphasized the need for urgent action because, according to one of our interview respondents (Respondent 6), the ‘cost of doing nothing would far outweigh the cost of acting’. The preference of DWA for tried and tested treatment solutions became evident in the choice of two ‘proven’ technologies: HDS for short-term partial AMD treatment (Team of Experts Citation2010) and RO treatment plants as reference projects or base cases for long-term treatment (DWA Citation2013b). The long-term intervention feasibility study also recommended that promising alternative AMD long-term treatment technologies, that might be more cost-effective than RO in the long run, should be tested against these reference projects for potential selection as long-term AMD treatment (DWA Citation2013b).

Various potential funding mechanisms were listed as part of the long-term intervention feasibility study, supporting this story-line’s emphasis on finding a pragmatic financing solution (DWA Citation2013a). Identifying suitable financing mechanisms also went hand in hand with the pragmatic argument made by various knowledge providers to this story-line that it was very difficult to apportion liability to specific mining companies (SAPA Citation2011) given the long and messy history of mining on the Witwatersrand.

The ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line

The ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line, which also emerged between 2009 and 2013, was characterized by blaming the gold mining industry and the government for having caused the AMD problem, the suggestion of alternative treatment options based on a critique and rejection of the tried and tested HDS and RO methods and the suggestion that the remaining mine owners operating on the Witwatersrand, as polluters, should be forced to pay for long-term AMD treatment.

Knowledge coalition

The main knowledge providers to the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line were the scientists of the university-based research group who had been commissioned by private sector financial institutions to conduct a study to investigate the accuracy of the claims that their buildings were threatened by rising AMD levels. Other knowledge providers included scientists who were critical of the way the AMD issue had been interpreted and handled, an activist law group, and members of the main opposition party in the South African Parliament. Knowledge users included the financial institutions who had commissioned the study in question, an environmental activist, the media who published the findings of the study and the readers of the resulting newspaper reports.

The beginning: a causal interpretation

Knowledge providers to the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line framed the cause of the AMD problem as something which had been predicted long before the first discharge took place, and laid the blame squarely at the feet of the gold mining sector and the South African government for not holding the sector accountable.

Liefferink, for instance, depicted the gold mining companies as brutal story-line villains who had ‘raped the earth for its gold and uranium’, leaving behind ‘gaping holes in the ground’, ‘polluted river sources’ and ‘unenriched communities’ (Bega Citation2010b). Similarly, knowledge providers to this story-line critiqued the South African government for being in cahoots with the mining sector and not taking appropriate action to address the problem.

To illustrate, Garfield Krige, one of the scientific contributors to the 1996 Strategic Water Management Plan which predicted the AMD discharge accused DWAF of ‘not taking proper decisions over that period’, despite being ‘completely aware that the voids would start filling up’ (Kardas-Nelson Citation2010). This, according to Krige, gave the mines ‘sufficient time to get rid of their liability’ (Kardas-Nelson Citation2010). Relatedly, Turton, with a clever use of metaphor, labeled the inability of the government to switch from collaborator to regulator of the mining industry after South Africa’s democratic transition a ‘hangover from the apartheid era’ (Naidoo Citation2009).

The middle: potential impacts of the problem on society and the environment

In their study to investigate the impacts of rising AMD levels on certain building in Johannesburg’s city center, the Mine Water Research Group (Citation2011, 10) stated that ‘after the initial flush of highly polluted water’, ‘cleaner water’ might begin discharging from the mine voids. This suggested that the impact of untreated AMD discharge on the quality of receiving streams was much less severe than had been argued in the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line. A related argument made by university governance professor Mike Muller was that the heavy focus on the ‘exaggerated’ impacts of AMD ‘distracted’ from other, more pressing water quality issues in the country (News24 Archives Citation2010).

In addition, the same group refuted the assumptions that had been made about the rate of rise, volume, and impacts of underground acidic mine water in the Central Basin. Specifically, the Mine Water Research Group (Citation2011) claimed that even if no action was taken to contain the rising AMD water levels, these would peak at levels well below the point at which they might start to impact building foundations. The report also identified a slower rate of rise of underground water levels resulting in a later predicted date of discharge of September 2013 (about six months later than what the Team of Experts report had predicted in Citation2010) and a single discharge point for the Central Basin due to the ‘sufficiently high interconnectivity between different sub-voids’ (as opposed to discharge occurring at several identified and unexpected points) (Mine Water Research Group Citation2011, 7).

Using the strategy of unambiguously attacking the credibility and acceptability of the scientific arguments made by the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line, the Mine Water Research Group (Citation2011) strongly questioned the thoroughness and scientific rigor of the Team of Experts (Citation2010) report, and, implicitly, the trust that should be placed in its authors. This was done by starting that the Team of Experts (Citation2010) report ‘lacks a thorough analysis of available data and leaves many crucial aspects superficially covered’.

The end: management options

Linked to downplaying the seriousness of the impacts of AMD, knowledge providers to the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line disagreed with the need for urgent action and instead proposed to let things ‘bleed a bit’ (Respondent 19). This would involve letting a natural ‘flushing effect’ run its course, which was eventually expected to result in ‘perfectly good spring water’ (Respondent 4). As an alternative AMD treatment option and based on the scientific and technical knowledge of its members, the Mine Water Research Group (Citation2011) proposed using large volumes of untreated AMD to aid nitrate digestion in municipal sewage works, which, it argued to emphasize the credibility and acceptability of this assumption, had already previously been implemented on the Central Rand (Mine Water Research Group Citation2011). Such a ‘sustainable, low-cost, low-energy solution’ was contrasted with ‘the currently proposed high-cost, high-energy, pump-and-treatment-option likely to be subsidized ad infinitum by society’ (Mine Water Research Group Citation2011, 12), thereby discrediting the proposed treatment technologies that underpinned the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line.

In contrast with the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line’s pragmatic argument that the remaining players in the gold-mining sector should not be financially overburdened, various knowledge providers to the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line argued on the basis of legal knowledge that the villainous gold mining industry should take prime responsibility and be made to pay for, as Liefferink put it (Bega Citation2011), the ‘immoral’ act of leaving South Africa with ‘aquifers polluted with acid drainage’ (Bega Citation2011). This might require more extreme and innovative legal approaches, for example, by going back to historical legal precedents (Majavu Citation2011) or appointing a team of seasoned lawyers to pursue future litigation processes (SAPA Citation2011).

Discussion: the struggle for discursive hegemony

The struggle for discursive hegemony began in 2011 when the thus far dominant ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line, which had been implicitly supported by policy-makers with the commissioning of the short-term AMD intervention, started being challenged by the considerably more radical and unconventional ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line launching an attack on its main tenets. Despite this challenge, the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line attained a strong measure of discourse structuration by dominating the recommendations to the government on how the AMD problem should be conceptualized and addressed. This was especially evident in the continuing implementation of short-term HDS treatment and the recommendation to the government to construct RO treatment plants as reference projects in the three basins (DWA Citation2013b).

After several years of delay, discourse structuration was followed by discourse institutionalization, when in 2016, the Minister of Water and Sanitation, Nomvula Mokonyane, announced the government’s official long-term policy response to the AMD problem, strongly reflecting the recommendations of the long-term intervention feasibility study. The main aim of the planned intervention was to turn the AMD problem into a long-term sustainable solution by producing fully treated water and significantly increasing water supply to the Vaal River System, instead of polluting it (South African Government News Agency Citation2016), thereby addressing one of the main concerns of the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line. Also, in line with this story-line’s pragmatic approach that cautioned against financially overburdening the mining sector, Mokonyane stated that only 67% of the implementation of the combined AMD short-term and long-term intervention would be funded by the mining sector, and that South African water users would be funding the remaining 33% of the cost because the entire country had benefited from mining (South African Government News Agency Citation2016).

Having achieved both discourse structuration and discourse institutionalization, the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line therefore achieved discursive hegemony, though not quite on the straightforward path predicted by Hajer (Citation1995, Citation2005). This is because the story-line exhibited a degree of hybridity (drawing on more than one discourse/story-line to inform a policy response) (Pascoe, Brincat, and Croucher Citation2019) as the plan for the long-term intervention drew on elements of the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line. This was done by making provision for the testing and piloting of promising alternative AMD long-term treatment approaches, while the initial RO reference technology treatment plants would be operational, and ultimately selecting the process with the ‘lowest lifetime costs’ (DWA Citation2013b). Incorporating some elements of the opposing discourse/story-line also corresponds to Dang et al.’s (Citation2012) observation that sometimes a dominant coalition incorporates elements of the competing discourse/story-line, without giving into its demands completely, thereby depriving the opposing coalition of a chance to structure the debate (Dang et al. Citation2012).

We now offer some reflections on why the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line emerged as dominant on the basis of our analytical framework structure, by considering the influence of the use of language, knowledge coalitions, institutional context and resources.

One of the most noticeable aspects regarding the use of language in the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line was the ‘show-stopping’ use of descriptions and metaphors. Such extreme yet memorable use of language provided attractive material to South Africa’s journalists, and the resulting media attention proved instrumental in pressuring government to formulate a considerably more decisive response to the AMD problem (Funke et al. Citation2012). Substantially more serious and academic language was used to emphasize the scientific rigor and authority of the data, methods, findings and recommendations of the short-term and long-term intervention reports (Team of Experts Citation2010; DWA Citation2013a).

The knowledge coalition affiliated to the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line also played a strong role in helping it emerge as dominant. This can in part be attributed to the horizontal agency of the scientists and private consultants forming part of this coalition as influential and respected members of South Africa’s research community. Furthermore, these scientists and consultants had considerable vertical agency as they were able to act with the confidence that the recommendations of their study, which had been commissioned by the South African government, would carry substantial weight and be backed by the necessary resources for implementation because the AMD problem had been recognized as a policy priority. Vertical agency amongst the ‘Threat is Serious’ knowledge coalition members was also reflected in the authority of the South African government to make final decisions on the implementation of the short- and long-term AMD solutions.

In contrast, the main contributors to the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line were scientists who had been excluded from the short-term intervention development process, and were only consulted amongst many stakeholders as part of the process of developing the long-term intervention. Their horizontal and vertical agency was considerably more limited as they were only accountable to their clients who had commissioned the desktop assessment to investigate the potential risk of flooding to their buildings. While the more radical suggestions of members of the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ knowledge coalition were not included in the final policy response, their critique of HDS and RO was addressed in the final recommendations of the AMD long-term intervention feasibility study process, as provision was made for the testing and piloting of technologies that might prove more cost- and energy-effective in the long run (DWA Citation2013b).

The influence and agency of the ‘Threat is Serious’ knowledge coalition members were closely connected to the institutional context of the official government-led process to identify, develop and implement a sustainable intervention to the AMD problem. Furthermore, this process was supported by various resources including the necessary decision-making authority, expertise, human resources and financial provisions to develop the interventions and implement HDS as the short-term solution. We can contrast this considerable institutional prowess and substantial resources with the absence of any such support for the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line, whose influence was limited to that of commentator, and ultimately perhaps potential bidder for the testing of alternative treatment options as part of the long-term intervention process.

Conclusion

In conclusion we reflect upon the learning of having applied our adapted ADA-based approach in terms of its ‘user-friendliness’, its ability to provide a rich analytical understanding of the AMD case, and the potential of its theoretical assumptions to explain the battle for discursive hegemony between the competing story-lines. We end off with some suggestions to strengthen the epistemic authority of both the ADA and IPA traditions.

In terms of the application of our chosen analytical framework, we found the plotline format to be useful in constructing the story-lines as it helped us to give structure to a somewhat vague concept. Constructing the story-lines according to plotlines enabled us to combine thematic focus areas (cause, impact and management options), with the idea of chronological progression from the start of the problem to its attempted resolution. Our focus on the role of scientific arguments embedded in the story-lines proved to be crucial as such arguments played an integral part in the impact and management components of the story-lines, and also helped explain the eventual hegemony of the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line. Our analytical framework’s focus on an array of creative rhetorical and discursive devices helped illustrate how these devices were used to persuade and influence knowledge users, while also enhancing the credibility, acceptability and the arguments underpinning the different story-lines.

Subsequently, we were able to show evidence of both discourse structuration and institutionalization of the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line. This was complemented by valuable insights into, amongst others, the influence of powerful ‘show stopping’ descriptors to raise awareness about the impacts of the AMD issue, the horizontal and vertical agency of influential and strongly-positioned knowledge coalition members, particularly when acting within the official government-backed institutional context of developing the short-term and long-term AMD interventions, and the various resources at the disposal of the ‘Threat is Serious’ coalition to achieve this. Overall, we found our adapted ADA approach to be user-friendly, which we believe also helped us to formulate a rich and deep analysis of the AMD case by illustrating the nuanced and symbiotic relationship between text and practice.

While most of the ADA’s theoretical concepts proved to be useful tools for explaining the story-lines that unfolded as part of the AMD case, we found the path to discourse institutionalization to be considerably more complex than predicted by the ADA approach (Hajer Citation1995, Citation2005). In featuring elements of hybridity, the AMD long-term intervention reflected some level of consensus between the opposing story-lines despite the ‘Threat is Exaggerated’ story-line having strongly criticized every element of the ‘Threat is Serious’ story-line. We now turn to some concluding thoughts on the potential refinement and expansion of ADA theory, which by implication would also contribute to the IPA tradition.

Providing additional guidance on the operationalization of ADA’s conceptual elements requires the development of an updated ADA framework based on a systematic review of all peer-reviewed literature that has used ADA as a primary analytical tool. This framework should consist of an updated and clearly defined set of analytical concepts and guidelines on how to operationalize these concepts. Based on our analysis of the AMD case study, a particularly important component of such an updated ADA framework is a reconceptualization of the possible paths to discourse institutionalization. Having demonstrated the usefulness of our own adapted ADA approach, we believe that our analysis takes an important first step in this direction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nikki Funke

Nikki Funke is a Senior Researcher in the Smart Places Cluster at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research in Pretoria, South Africa. She is currently studying towards a Doctorate in the Policy Sciences at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Nikki’s main research interest is to critically analyze the role of experts and expert-based information from different theoretical perspectives.

Dave Huitema

Dave Huitema is a Professor of Environmental Policy who works at the Open University of the Netherlands and at the Institute for Environmental Studies (IVM) at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Dave's training is in public administration and policy, and he is particularly interested in the causes and reasons for policy dynamics in the field of environmental governance.

Arthur Petersen

Arthur Petersen is Professor of Science, Technology and Public Policy at University College London (UCL) and Editor of Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science. From 2001–2014 he was a scientific adviser on environment and infrastructure policy within the Dutch Government, latterly Chief Scientist of the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. Most of his research is about dealing with uncertainty.

Notes

1. HDS treatment neutralizes acidic mine water and separates this mixture into alkaline water (i.e. HDS effluent) and a salt and mineral rich sludge waste product which has to be disposed of (INPA Citation2014). This HDS effluent water has a significantly lower salt and slightly lower metal load than untreated mine water but requires additional treatment (TCTA Citation2012).

2. Reverse osmosis is a technology that is used to remove a large majority of contaminants from water by pushing the water under pressure through a semi-permeable membrane (Puretec Water Citation2016).

References

- Arnoldussen, T. 2016. “The Social Construction of the Dutch Air Quality Clash.” PhD Dissertation, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam.

- Asayama, S., and A. Ishii. 2017. “Selling Stories of Techno-Optimism? the Role of Narratives on Discursive Construction of Carbon Capture and Storage in the Japanese Media.” Energy Research & Social Science 31: 50–59. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.06.010.

- Atkins, E. 2019. “Disputing the ‘National Interest’: The Depoliticization and Repoliticization of the Belo Monte Dam, Brazil.” Water 11 (103): 103. doi:10.3390/w11010103.

- Bartels, K. P. R., H. Wagenaar, and Y. Li. 2020. “Introduction: Towards Deliberative Policy Analysis 2.0.” Policy Studies 41 (4): 295–306. doi:10.1080/01442872.2020.1772219.

- Bega, S. 2009. “Turton Throws a New Water Bomb: Ex-CSIR Scientist Launches Campaign against Plan to Recycle Mine Water for Human Consumption.” Saturday Star, 21 November 2009.

- Bega, S. 2010a. “Close Mines, Expert Says of Looming Water Crisis.” Saturday Star, 28 August 2010.

- Bega, S. 2010b. “Where Poison Water Seeps from the Earth.” Saturday Star, 30 January 2010a.

- Bega, S. 2010c. “Rising Acid Mine Water Crisis Looms.” Saturday Star, 7 August 2010.

- Bega, S. 2011. “Acid Crisis Keeps Flowing.” Saturday Star, 28 February 2011.

- Bevir, M., and J. Blakely. 2018. Interpretive Social Science: An Anti-Naturalist Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bobbins, K. 2015. Acid Mine Drainage and Its Governance in the Gauteng City-Region. Occasional Paper 10. Johannesburg: Gauteng City-Region Observatory.

- Bomberg, E. 2017. “Shale We Drill? Discourse Dynamics in UK Fracking Debates.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19 (1): 72–88. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1053111.

- Colenbrander, D. 2019. “Dissonant Discourses: Revealing South Africa’s Policy-to-Praxis Challenges in the Governance of Coastal Risk and Vulnerability.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62 (10): 1782–1801. doi:10.1080/09640568.2018.1515067.

- Costella, G. 2012. “Greater Intervention Needed to Tackle Acid Mine Drainage.” Mining Weekly, 23 March 2012.

- Council for Geoscience. 2017. Downloadable Material. http://www.geoscience.org.za/index.php/publication/downloadable-material.

- Dang, T. P., K. E. Turnhout, and B. Arts. 2012. “Changing Forestry Discourses in Vietnam in the past 20 Years.” Forest Policy and Economics 25: 31–41. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2012.07.011.

- Dodge, J. 2017. “Crowded Advocacy: Framing Dynamic in the Fracking Controversy in New York.” Voluntas 28 (3): 888–915. doi:10.1007/s11266-016-9800-6.

- Dodge, J., and T. Metze. 2017. “Hydraulic Fracturing as an Interpretive Policy Problem: Lessons on Energy Controversies in Europe and the U.S.A.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2016.1277947.

- DWA (Department of Water Affairs). 2013a. Feasibility Study for a Long-term Solution to Address the Acid Mine Drainage Associated with the East, Central and West Rand Underground Mining Basins: Implementation Strategy and Action Plan. DWA Report No.: P RSA 000/00/16812. Pretoria: Department of Water Affairs.

- DWA (Department of Water Affairs). 2013b. Feasibility Study for a Long-term Solution to Address the Acid Mine Drainage Associated with the East, Central and West Rand Underground Mining Basins. Newsletter, Edition 3. Pretoria: Department of Water Affairs.

- Feindt, P. H., and A. Oels. 2005. “Does Discourse Matter? Discourse Analysis in Environmental Policy Making.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 7 (3): 161–173. doi:10.1080/15239080500339638.

- Funke, N., S. Nienaber, and C. Gioia. 2012. “Interest Groups at Work: Environmental Activism and the Case of Acid Mine Drainage on Johannesburg’s West Rand.” In Public Opinion and Interest Groups Politics: South Africa’s Missing Links?, edited by H. Thuynsma, 193–214. Pretoria: Africa Institute of South Africa.

- Funke, W. N., and P. Hobbs. 2016. The Witwatersrand Acid Mine Drainage Conundrum Contextualised. Pretoria: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research.

- Glynos, J., D. Howarth, A. Norval, and E. Speed. 2009. Discourse Analysis: Varieties and Methods. Swindon: ESRC National Centre for Research Methods.

- Gommeh, E., H. Dijstelbloem, and T. Metze. 2021. “Visual Discourse Coalitions: Visualization and Discourse Formation in Controversies over Shale Gas Development.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 23 (3): 363–380. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2020.1823208.

- Hajer, M. A. 1995. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hajer, M. A. 2005. “Coalitions, Practices, and Meaning in Environmental Politics: From Acid Rain to BSE.” In Discourse Theory in European Politics, edited by D. Howarth and J. Torfing, 297–315. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan.

- INPA (International Network for Acid Prevention)2014. Global Acid Rock Drainage Guide (GARD Guide). http://www.gardguide.com.

- Jørgensen, M., and L. Phillips. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London: Sage.

- Kardas-Nelson, M. 2010. “Rising Water, Rising Fear: SA’s Mining Legacy.” Mail & Guardian, 12 November 2010.

- Kaufmann, M., H. Mees, D. Liefferink, and A. Crabbé. 2016. “A Game of Give and Take: The Introduction of Multi-layer (Water)safety in the Netherlands and Flanders.” Land Use Policy 57: 277–286. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.05.033.

- Keller, A. C. 2009. Science in Environmental Policy. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: MIT Press.

- Kroepsch, A. 2016. “New Rig on the Block: Spatial Policy Discourse and the New Suburban Geography of Energy Production on Colorado’s Front Range.” Environmental Communication 10 (3): 337–351. doi:10.1080/17524032.2015.1127852.

- Kurki, V., A. Takala, and E. Vinnari. 2016. “Clashing Coalitions: A Discourse Analysis of an Artificial Groundwater Recharge Project in Finland.” Local Environment 21 (11): 1317–1331. doi:10.1080/13549839.2015.1113516.

- Lakoff, G. 1993. “The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor.” In Metaphor and Thought, edited by A. Ortony, 202–225. Second ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Majavu, A. 2011. “Acid Water No One’s Fault – Mines.” Sowetan, 29 June 2011.

- Masterson, V. A., M. Spierenburg, and M. Tengö. 2019. “The Tradeoffs of Win–win Conservation Rhetoric: Exploring Place Meanings in Community Conservation on the Wild Coast, South Africa.” Sustainability Science 14 (3): 639–654. doi:10.1007/s11625-019-00696-7.

- McCarthy, T. 2010. The Decanting of Acid Mine Drainage in the Gauteng City-Region. Analysis, Prognosis and Solutions. Provocations Series. Johannesburg: Gauteng City-Region Observatory.

- Mine Water Research Group. 2011. Desktop Assessment of the Risk for Basement Structures of Buildings of Standard Bank and ABSA in Central Johannesburg to Be Affected by Rising Mine Water Levels in the Central Basin. Volume I of III. 19 May 2011.

- Naidoo, B. 2009. “Acid Mine Drainage: Single Most Significant Threat to SA’s Environment.” Mining Weekly, 8 May 2009.

- News24 Archives. 2010. “Time to Panic about Water – Expert.” News24, 19 February 2011.

- Nielsen, T. D. 2016. “From REDD+ Forests to Green Landscapes? Analyzing the Emerging Integrated Landscape Approach Discourse in the UNFCCC.” Forest Policy and Economics 73: 177–184. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2016.09.006.

- Orhan, G. 2006. “Coalitions in the Case of the Bergama Gold Mine Dispute.” Policy and Politics 34 (4): 691–710. doi:10.1332/030557306778553123.

- Pascoe, S., S. Brincat, and A. Croucher. 2019. “The Discourses of Climate Change Science: Scientific Reporting, Climate Negotiations and the Case of Papua New Guinea.” Global Environmental Change 54: 78–87. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.11.010.

- Prinsloo, L. 2009. “Clashing Views on How Treated Mine Water Should Be Used.” Mining Weekly, 9 October 2009.

- Ramcilovic-Suominen, S., and I. Nathan. 2020. “REDD+ Policy Translation and Story-lines in Laos.” Journal of Political Ecology 27: 437–455. doi:10.2458/v27i1.23188.

- Rennkamp, B., S. Haunss, K. Wongsa, A. Ortega, and E. Casamadrid. 2017. “Competing Coalitions: The Politics of Renewable Energy and Fossil Fuels in Mexico, South Africa and Thailand.” Energy Research & Social Science 34: 214–223. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.07.012.

- SAPA (South African Press Association). 2011. “Mines Can’t Absolve Responsibility for AMD – De Lange.” Mining Weekly. 28 June 2011. https://www.miningweekly.com/print-version/mines-cant-absolve-responsibility-fro-amd-de-lange-2011-06-28.

- South African Government News Agency. 2016. Long-term Solution for Acid Mine Drainage, 19 May 2016.

- Spencer, L., J. Ritchie, and W. O’Connor. 2003. “Analysis: Practices, Principles and Processes.” In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, edited by J. Ritchie and J. Lewis, 199–218. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

- Staff Reporter. 2010. Staff Reporter 2010 Johannesburg on Acidic Water Time Bomb. Mail & Guardian, 21 July 2010.

- Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. 2015. Agency. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/agency/Strydom

- Strydom, W., N. Funke, and P. Hobbs. 2016. The Witwatersrand Acid Mine Drainage Conundrum Contextualised. Pretoria: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research.

- Sunday Independent. 2011. “Playing Russian Roulette with Our Water.” Sunday Independent, 28 February 2011

- TCTA (Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority). 2012. Annual Report 2011/2012.

- TCTA (Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority). 2018. Annual Report 2018/2019.

- Team of Experts (Expert Team of the Inter-ministerial Committee on Acid Mine Drainage). 2010. Mine Water Management in the Witwatersrand Gold Fields with Special Emphasis on Acid Mine Drainage (Pretoria: Government of South Africa).

- Tuffnell, S. 2017. “Acid Drainage: The Global Environmental Crisis You’ve Never Heard Of.” The Conversation, 5 September 2017.

- Van Buuren, A., and J. Edelenbos. 2004. “Why Is Joint Knowledge Production Such a Problem?” Science & Public Policy 31 (4): 289–299. doi:10.3152/147154304781779967.

- Van Ostaijen, M. 2017. “Between Migration and Mobility Discourses: The Performative Potential within ‘Intra-European Movement’.” Critical Policy Studies 11 (2): 166–190. doi:10.1080/19460171.2015.1102751.

- Water, P. 2016. What is Reverse Osmosis? https://puretecwater.com/reverse-osmosis/what-is-reverse-osmosis

- Williams, L., and B. K. Sovacool. 2019. “The Discursive Politics of ‘Fracking’: Frames, Storylines, and the Anticipatory Contestation of Shale Gas Development in the United Kingdom.” Global Environmental Change 58: 101935. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101935.

- Yanow, D. 2007. “Interpretation in Policy Analysis: On Methods and Practice.” Critical Policy Studies 1 (1): 110–122. doi:10.1080/19460171.2007.9518511.

- Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.