ABSTRACT

The Scottish Government’s policy of minimum unit price (MUP) for alcohol has received significant scholarly attention. Much of the focus of this literature has been on the efforts by sections of the alcohol industry to oppose the policy, including attempts to ‘frame’ key terms of the debate and an understanding of its legitimacy and effects within the wider field of interpretative policy analysis. The present article builds on these studies by re-conceptualizing the MUP debate through the lens of post-structuralist discourse theory and the logics of critical explanation that emerge from this. It argues that the success and failure of MUP (as a projected social logic) can be understood through the shifting coalitions of actors that emerged (political logics) and the affective hold that industry narratives were able to exert (fantasmatic logics) in this context. While focused on UK alcohol policy, the article speaks to a wider research agenda on the ‘commercial determinants of health’ and, through the application of the critical logics approach, offers new analytical insights beyond those provided by existing models of industry influence. Similarly, it contributes to the field of post-structural policy analysis through its novel focus on the role of commercial entities as health policy actors.

Introduction

Since the publication of the Scottish Government’s (Citation2008) alcohol strategy, significant attention has been paid by policy scholars to developments in UK alcohol policy (Holden and Hawkins Citation2012; Hawkins, Holden, and McCambridge Citation2012; Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020; Katikireddi et al. Citation2014, Citation2014; Katikireddi and Hilton Citation2015). The commitment to introduce a minimum unit price (MUP) for alcohol represented a decisive rupture in the prevailing equilibrium in UK alcohol policy and was vehemently opposed by sections of the alcohol industry (McCambridge, Hawkins, and Holden Citation2014; Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020).

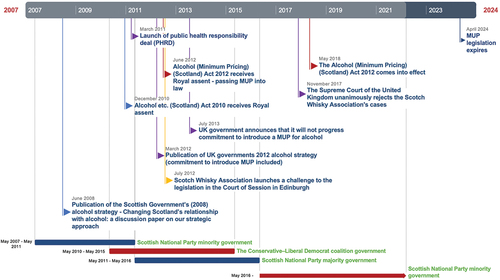

Under the 2007–2011 Scottish National Party (SNP) minority government industry actors succeeded in lobbying the opposition parties to remove MUP from the Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act 2010. MUP was eventually enacted in the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 under the majority SNP administration elected in 2011, however, its implementation was delayed until 2018 as a result of legal action led by the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020). Concurrently, a commitment to introduce MUP in England had been included in the UK Government’s 2012 alcohol strategy, only for the government to abandon plans for its implementation just over a year later (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019a) (see ).

Studies of MUP in the UK can be situated in the wider literature on the political strategies of health-harming industries and their influence on policy-making. Building on seminal work on trans-national tobacco companies’ strategies to prevent the regulation of their products and shape the evidential content of policy debates (Hurt et al. Citation2009), previous studies have examined the efforts of the alcohol industry – defined as all entities involved in the commercial production, distribution, sales and marketing of beverage alcohol (Jernigan Citation2009) – to influence policy (McCambridge, Mialon, and Hawkins Citation2018; McCambridge and Mialon Citation2018; Mialon and McCambridge Citation2018) as part of a wider focus on ‘the commercial determinants of health’ (Mialon Citation2020; De Lacy-Vawdon and Livingstone Citation2020).

A key component of corporate political strategy involves attempts to shape perceptions among policy makers, the media, and the wider public about the effects of their products and business models; whether these represent a ‘policy problem’ warranting governmental intervention; and, if so, the specific form these interventions should take (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). To date, scholars have mainly approached this aspect of corporate political strategy through the concept of ‘framing’ (Van Hulst and Yanow Citation2016; Koon, Hawkins, and Mayhew Citation2016). For example, McCambridge, Mialon, and Hawkins (Citation2018) identify ‘policy framing’ as a key component of global alcohol industry strategy alongside ‘policy influencing’ (e.g. lobbying activity and financial contributions). Hawkins and Holden (Citation2013), meanwhile, examined how public health advocates and civil society organizations advocating for MUP recognized the need to ‘reframe’ alcohol policy debates away from the industry’s preferred focus on individual responsibility, public order issues, and targeted policies toward a public health framing that emphasizes the need for population-level interventions (see also Katikireddi et al. Citation2014).

For harmful commodity industries, such as alcohol and tobacco, policy changes like MUP are seen predominantly as threats to be managed (Proctor Citation2011; Michaels Citation2020; Holden and Hawkins Citation2012). Consequently, the political communications strategies of industry actors in these sectors seek to play down the extent and nature of harms associated with their products; to deny the need for policy responses or, where policy change cannot be avoided, to influence the content of measures to minimize their impact on commercial interests (McCambridge, Hawkins, and Holden Citation2013; McCambridge, Mialon, and Hawkins Citation2018; Lauber, Mcgee, and Gilmore Citation2021; Fooks et al. Citation2019; Van Schalkwyk et al. Citation2021; Ulucanlar et al. Citation2014).

In their analysis of the global tobacco industry, Ulucanlar et al. (Citation2016) identified what they term a ‘policy dystopian model’ (PDM) to capture the structure and content of industry discourses. In order to resist (unfavored) policy development, industry actors construct and disseminate ‘a metanarrative to argue that the proposed policies will lead to a dysfunctional future of policy failure and widely dispersed adverse social and economic consequences […] in order to secure preferred policy outcomes'. The concept of ‘policy dystopia', and the catastrophizing tendency of industry narratives in sectors beyond tobacco, signals the importance of emotion in explaining policy change and policy stasis (Howarth Citation2013; Durnova Citation2022). However, the affective dimension of these policy debates remains under-explored in the literature on the commercial determinants of health.

In contrast to framing approaches, post-structuralist discourse theory (PSDT) (Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985), and the critical logics approach (CLA) developed by Glynos and Howarth (Citation2007), are able to theorize the emotive dimension of policy debates through their engagement with the Lacanian concepts of fantasy and enjoyment. Moreover, these approaches provide scholars with a sophisticated conceptual vocabulary, which situates attempts to articulate policy problems and their solution – the focus of framing scholars – within wider networks of political alliances and affective investment that are able to explain policy outcomes at specific places in time and how to conceptualize the exercise of power.

Framing analyses of UK alcohol policy have formed part of a wider research agenda into policy developments in Scotland and England (McCambridge, Hawkins, and Holden Citation2014; Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019a, Citation2020, Citation2021), which can be situated within the fields of hermeneutical analysis and interpretative policy studies (see Yanow Citation2007). Drawing on interviews with, and analyses of documents produced by, relevant policy actors, these studies seek to explain policy outcomes in terms of the ‘contextualized self-interpretations’ of these actors (see Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). While they present persuasive, theoretically informed understandings of the alcohol policy process, from a post-structuralist perspective it is possible to identify limits to the explanatory power of these accounts and the wider epistemological tradition from which they emerge.

To date, there has been no explicit application of PSDT and the CLA to study the political strategies of harmful commodity industries, such as the alcohol sector, although the framework has been deployed in the analogous context of gambling policy (Van Schalkwyk, Hawkins, and Petticrew Citation2022). Yet important additional insights into the field – in terms of the structure and power of policy discourses – can be derived from the application of this approach. This article seeks to demonstrate how our understanding of UK alcohol policy, and corporate political activity more generally, can be strengthened through the application of the CLA (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). The article synthesizes existing empirical accounts of MUP in Scotland and England, reinterpreting their findings through the lens of the CLA. It argues that this approach offers additional analytical depth beyond framing analyses and ‘contextualized self-interpretations’ in which previous studies are grounded (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007).

By introducing the Lacanian concept of fantasy, this article builds on existing accounts of the framing strategies of health-harming industries and offers additional insights into their affective power compared to current frameworks such as the PDM. In addition, by rearticulating accounts of the UK alcohol pricing debates in terms of the ontological assumptions and conceptual vocabulary of the CLA, it is possible to present an account of policy change and policy stasis, in Scotland and England, respectively, which transcends the explanatory power of the ‘contextualized self-interpretations’ of policy actors, which form the basis of existing studies. In so doing, it contributes not only to a deeper understanding of UK alcohol policy debates, and the wider research agenda on the commercial determinants of health, but also to the development of post-structural policy analysis through the application of the CLA to study new policy areas and actors.

The critical logics approach and policy-making

The CLA is now a well-established approach within PSDT and the wider field of critical policy studies (Howarth, Glynos, and Griggs Citation2016). Consequently, the current article assumes readers’ prior familiarity with the conceptual vocabulary of the CLA (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007), as well as PSDT more generally (see Howarth Citation2000), but will summarize briefly the main theoretical tenets of the approach. Within the conceptual vocabulary of the CLA, logics function at both the ontological and the ontic levels. They are ontological categories, which describe the conditions of possibility for the explanation and critique of social phenomena (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). At the same time, these logics manifest themselves at the ontic level in their application to specific regimes, processes, and practices in the social world. Thus, we can speak about social logics as a general critical-explanatory category and, in examining certain policy cases, may identify a logic of nationalism as a particular feature of a specific policy discourse (Hawkins Citation2015, Citation2022).

Logics, therefore, chart a middle way between the universalist pretensions of positivist social science – which seeks to explain individual cases in terms of subsuming causal laws or mechanisms – and the particularism of hermeneutic approaches, which seek to explain these social events and processes in terms of particular, contextual factors and the self-understandings of actors embedded within these (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). While attentive to the importance of situated, meaningful practices, the CLA provides a set of epistemological tools able to transcend the self-conscious rationalizations of policy actors and to explain social phenomena and policy outcomes in terms of constitutive logics, which may not be evident to, understood or problematized by, policy actors themselves (Howarth Citation2013). Furthermore, the recognition of radical contingency of social relations opens up space for examining both the ethical-normative choices implied for political subjectivities in aligning themselves with competing discourses, and the role of power in mobilizing popular support for these – ‘interpellating’ actors into subject positions – via hegemonic practices (Laclau Citation2005).

Social logics seek to establish what the ‘rules of the game’ are within a particular social context, outlining the dominant norms, values, and identity positions within a discursive formation. More recently, Glynos, Klimecki, and Willmott (Citation2015) introduced the concept of a ‘projected social logic’ to capture attempts to present alternative visions of society to the prevailing order. Political logics meanwhile seek to capture the establishment, maintenance, and challenges of such discursive formations through the sub-logics of equivalence and difference. They detail how a political project emerges through the construction of effective equivalential chains, binding disparate elements together through their common rejection of an externalized ‘other’. Political logics also chart how these chains can be expanded to domesticate and defuse potential challenges to its organizing unity and political dominance (Howarth Citation2010; Griggs and Howarth Citation2019; Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985). This leads to the formation of (at times) unlikely allegiances between different actors and interest groups, with varying demands, within discursive formations bound together in terms of their shared rejection of a common ‘other’ – for example, the ‘minority’ of consumers who lack personal responsibility or the ‘prohibitionist’ public health advocates in the context of health policy debates.

Finally, fantasmatic logics account for the emotional investment in political or policy projects by their adherents and thus the hold these discourses are able to maintain over individual subjects (Glynos and Stavrakakis Citation2008; Glynos Citation2021; Behagel and Mert Citation2021). The Lacanian concept of fantasy, as employed within the CLA, functions through the promise of an absent communitarian fullness capable of providing the subject with a fully constituted identity associated with the Real, described by Glynos and Howarth (Citation2007) as the ‘enjoyment of closure’. Fantasmatic logics serve the ideological purpose of masking over the impossibility of a fully reconciled social order through the production of fantasy objects. Consequently, they are essential for understanding the dynamic force of both movements for political change and the efforts to resist change by the adherents of established social orders.

The CLA has been widely deployed to study the emergence of particular social logics in the context of contemporary capitalism, and their constitution and maintenance via political and fantasmatic logics (Glynos and Speed Citation2012; Howarth and Griggs Citation2006; Clarke Citation2012; Speed and Mannion Citation2020; Runfors, Saar, and Fröhlig Citation2021; Van Schalkwyk, Hawkins, and Petticrew Citation2022; Quennerstedt, McCuaig, and Mårdh Citation2021; Papanastasiou Citation2019.; Remling Citation2018). These studies demonstrate how the CLA offers a powerful conceptual framework for explaining policy change by rendering visible the contingent nature of even highly sedimented social relations. At the same time, they demonstrate the utility of critical logics, and the wider conceptual vocabulary of the CLA, for theorizing and critically explaining counter-hegemonic strategies designed to head off dislocations in prevailing policy regimes and maintain the status quo. Given the wide range of policy areas in which the CLA has been deployed, the absence of studies examining the political strategies of harmful commodity industries, within the expanding literature on the commercial determinants of health, appears anomalous.

The CLA provides not only a set of analytical concepts for analyzing social and political phenomena but also implies a particular logic for conducting research, in keeping with the ontological assumptions of PSDT (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). From this perspective, the research process can be understood to follow a retroductive logic, which proceeds through the problematization, articulation, and critique of the social objectivities to which it is applied (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). Retroduction implies breaking down the distinctions that exist in mainstream, ‘positivist’ research between the contexts of ‘discovery’ and ‘justification’, and between theory and data, as well as a rejection of the idea that social phenomena can be explained with reference to universal, decontextualized ‘covering laws’ or causal mechanisms (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). At the same time, it questions the ability of ‘thick description’ or ‘contextualized self-interpretations’ – i.e. researchers’ interpretations of policy actors' own understanding of their situated practices – which are the currency of the hermeneutical tradition to fully exhaust the explanatory potential of post-positivist approaches to social and political research. Retroduction thus shifts the mode of thinking from proving causality or capturing the uniqueness of a social setting, toward charting and critically explaining the complex processes and practices that constitute the social world (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007).

That is not to say that post-structuralist approaches reject the importance of actors’ accounts or the study of inter-subjective meaning in specific policy spaces out of hand (Howarth Citation2013). Indeed, the opposite is true. Post-structuralist analysis starts from precisely such actor-centered accounts, but seeks to move beyond this by offering novel and persuasive explanations of social phenomena through the applications of its distinctive ontology and related analytical concepts. This begins with the problematization of existing (and often highly sedimented) policy regimes, practices, and identity positions, exposing their historical and political origins (Howarth Citation2010). This facilitates the articulation of new and insightful explanatory accounts of these policy spaces in terms of social, political, and fantasmatic logics and their associated conceptual vocabulary.

However, the process of critical explanation implies not only an analytical but also an ethical impetus to reveal both the contingent nature of the status quo ante and the power relations embedded within a policy space, thereby facilitating its (potential) replacement by alternative social imaginaries. This in turn implies a normative impulse to the explanatory process whereby the predominant values of the policy consensus can be challenged by alternative priorities in keeping with the fundamental, motivating values of a competing discursive project (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007).

In the case of alcohol policy – and wider research on the commercial determinants of health – this would see the replacement of a logic of (industry) partnership with a pluralist logic of democratic openness to all policy actors regardless of economic resources (Hawkins, Holden, and McCambridge Citation2012). The criteria for evaluation of these analyses are the extent to which they are able to render social phenomena comprehensible or offer new insights into previously vexed questions, in ways that are plausible to the relevant community of scholars studying, and practitioners embedded within, the relevant policy space (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007).

Research strategy

This article presents a secondary analysis of previously published studies of MUP in Scotland and England, reinterpreting these through the conceptual architecture of PSDT and the CLA. These studies and the methods and data sources on which they draw are set out in . No further analysis or coding of the primary datasets on which these studies draw was undertaken. The aim of the article is to offer deeper insights into a complex, multi-jurisdictional policy process through the problematization of existing, interpretative analyses of alcohol pricing debates in England and Scotland and their rearticulation in terms of social, political, and fantasmatic logics, as well as the wider conceptual architecture of the CLA.

Table 1. Methods and data sources of previous UK alcohol policy studies.

The analysis below begins by setting out the predominant social logics of the UK alcohol policy consensus prior to 2008. It then examines how this was successfully problematized, and an alternative policy discourse articulated, by health policy advocates in the context of a new and receptive administration in the Scottish Government. This formed the basis of a successful hegemonic project leading to the establishment of a new Scottish alcohol policy regime. In England, meanwhile, while MUP came onto the policy agenda, it was resisted by industry actors who were able to prevent policy change through successful counter-hegemonic practices. While much of the focus is on the contribution of fantasy in understanding the emotive hold of different policy discourses in different contexts, additional insights can be derived from the application of social and political logics. The latter aid understanding of the embedded nature of policy regimes and practices, their resistance to change in England, and their openness to rearticulation in Scotland.

Policy equilibrium and the social logics of the industry-favorable discourse

The story of UK alcohol policy since 2008 has been one of both radical change, in terms of the enactment of MUP in Scotland, and a successful counter-political strategy by the alcohol industry to delay its implementation, mitigate its effects, and prevent the extension of the policy to other parts of the UK. While the alcohol industry is not monolithic, there was a vociferous anti-MUP position, which emerged as the dominant industry voice in this debate (Holden, Hawkins, and McCambridge Citation2012). Industry actors promote a particular account of alcohol, its effects, and the appropriate policy regime to regulate the sale, marketing, and consumption of alcoholic beverages (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013; McCambridge, Mialon, and Hawkins Citation2018).

This industry-favorable discourse was reflected in the UK-wide policy consensus prior to 2008 and is characterized by specific social logics (Hawkins, Holden, and McCambridge Citation2012). Industry discourses are based on a logic of diminution, whereby they claim that the scale of alcohol-related harms is overstated by public health actors and a sensationalist media, pointing, for example, to falling levels of population-level consumption to support this (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013; McCambridge, Hawkins, and Holden Citation2013). In addition, harms must be seen in the context of the contribution, which the industry makes to the economy (as a source of employment and taxation), and consumers’ enjoyment (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013).

Industry discourses are also based on the logic of individualization. The responsibility for overconsumption is placed on individual consumers, their lack of awareness or understanding and/or their inability to exercise moderation and self-control. Industry actors play down the idea of societal-level harms, arguing that the effects are limited to an allegedly small minority of consumers (McCambridge, Mialon, and Hawkins Citation2018; Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). In addition, via a logic of circumscription, they focus only on particular forms of harm, such as underage drinking, drinking in pregnancy, drink-driving, and heavy episodic (‘binge’) drinking versus chronic health harms associated with long-term alcohol consumption (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). At other times, it is claimed that harms are limited to certain groups and contexts, such as those experiencing high levels of unemployment and economic deprivation. Alcohol-related harms are thus a symptom of underlying social problems that governments should seek to address instead of their narrow focus on regulating alcohol (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). Elsewhere, industry actors claim that it is cultural factors that shape alcohol consumption patterns in the UK, calling for a change in the UK’s ‘drinking culture’ as the solution (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). This focus on macro-social and cultural factors contradicts industry attempts to underplay the scale of the UK’s alcohol problems and their focus on individual irresponsibility in ways that indicate the existence of ideological practices (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007).

Alcohol industry actors identify a series of favored policy measures in keeping with their definition of alcohol problems (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013; McCambridge, Mialon, and Hawkins Citation2018). Following a logic of diminution, they argue that new policy measures are not needed and call instead for more effective implementation of existing regulations (particularly those on underage sales and drivers’ blood alcohol content). In keeping with the logic of individualization, they favor targeted interventions that focus on specific sub-populations experiencing harms (e.g. treatment programs for heavy or dependent drinkers) as opposed to population-level measures, such as tax increases, restrictions on sales, or advertising bans. From their perspective, the role of government is to support individuals to moderate their consumption through the provision of information and behavioral advice via industry-funded outlets, such as Drinkaware (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013; Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2014; McCambridge et al. Citation2013).

Their favored policy programs are also characterized by a logic of partnership based on co- and self-regulatory regimes that found its apotheosis in the UK government’s Public Health Responsibility Deal (PHRD) between 2011 and 2015 (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019b). Similarly, the alcohol industry is identified as a key ‘stakeholder’ that must be involved in policy-making processes to avoid the adoption of ineffective, unworkable, or counter-productive policies. This positions the industry as part of the solution to, not the cause of, alcohol-related harms (McCambridge, Hawkins, and Holden Citation2013). At the same time, the logic of partnership challenges the idea that public health actors – i.e. health bodies, academic researchers, and non-governmental organizations [NGOs] – should have privileged access to policy makers since these organizations represent just another interest group of equivalent status to the industry (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019b). Thus, the concept of social logics and their particular ontic manifestations within the industry-favorable discourse enable us to capture the political equilibrium in UK alcohol policy prior to the dislocatory events in Scotland.

Policy dislocation and the political logics of counter-hegemonic discourse

The industry-favorable discourse, which represented the UK-wide alcohol policy consensus prior to 2008, emerged through the construction of an equivalential chain connecting relevant policy actors and entities. This included not only industry bodies but also ministers who wanted to be seen to be addressing alcohol-related harm and civil society actors whose agendas were served by the status quo (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020, Citation2021; Holden and Hawkins Citation2012). This consensus was also underpinned by a unionist logic in which the UK, despite the formal devolution settlement, functioned de facto as a shared political space in the field of alcohol policy (Holden and Hawkins Citation2012; Hawkins, Holden, and McCambridge Citation2012).

The hegemony of the industry-favorable discourse was broken by the publication of the Scottish Government’s (Citation2008) alcohol strategy. This was, in turn, the product of political developments post-devolution, including the emergence of a network of public health and alcohol-specific NGOs, which promoted an alternative understanding of alcohol-related harms as requiring population-level responses, including price increases (Holden and Hawkins Citation2012). This public health discourse constituted a ‘projected social logic’ (Glynos, Klimecki, and Willmott Citation2015) which challenged the key assumptions of the hegemonic industry-favorable discourse.

The SNP Government committed to tackling health inequalities in Scotland and sought to instrumentalize policy divergence with England as part of a wider strategy to gain independence from the UK. By engaging with public health actors’ policy discourse, the Scottish Government signaled its intention to prioritize public health over commercial interests (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013; Katikireddi et al. Citation2014, Citation2014). In discourse theoretical terms, the political interests of the SNP administration could no longer be domesticated within the industry-favored discourse, and it began to articulate its agenda in terms of alternative public health discourse. Public health advocates, for their part, explained the change as the result of successful efforts to ‘reframe’ alcohol policy debates away from public order issues and problematic sub-populations (such as binge) drinkers toward an explicitly health-oriented and population-level account of alcohol-related harms and policy responses (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013).

Unsurprisingly, these dislocatory events gave rise to a forceful response from the alcohol industry, which sought to challenge the government’s agenda through a range of counter-hegemonic practices (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020, Citation2021). Initially, industry actors sought to prevent the adoption of MUP as government policy by reinforcing the central tenets of the industry-favorable discourse (Holden and Hawkins Citation2012; Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). However, as the political terrain shifted, and some form of price-based intervention became inevitable, industry actors shifted their emphasis to mitigating the potential commercial effects of the SNP’s policy agenda. To this end, they sought to rearticulate the key aspects of the emerging public health discourse, absorbing them as differential positions with an expanded and adapted industry-favorable discourse, and thereby suturing together the emerging dislocations in the policy equilibrium (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020, Citation2021). This strategy enjoyed some success, including the decision by Scottish Labour MSPs to vote against the government to remove MUP from the Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act (2010). Labor’s decision to oppose the policy resulted from the direct challenge that the SNP’s articulation of the public health discourse posed to their identity as the progressive force and champions of public health in Scottish politics.

Recognizing the SNP’s focus on the need to provide Scottish solutions to what they articulated as Scottish problems, industry actors also adopted a specifically ‘Scottish frame of reference’ in which the SWA played a leading role (Holden and Hawkins Citation2012). This emphasized the vital importance of the whiskey industry for the Scottish economy and employment, including in many poor and rural communities. In addition, they sought to rearticulate MUP from being a purely domestic, health-focused policy to a principally economic and trade-related issue for a key export product, such as whiskey (Holden and Hawkins Citation2012). Political logics came to the fore in industry attempts to create ‘internal’ opposition to the policy, and to play ‘divide and rule', between both different departments in the Scottish Government and between the Scottish and Westminster polities – including between SNP MSP and MPs – by highlighting the different implications of the policy for those not primarily focused on domestic health issues (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2021). In addition, they highlighted correspondence from the governments of other alcohol producing states concerned about the issues raised by the industry (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2021).

This strategy culminated in the initiation of legal proceedings by the SWA against the Scottish Government on the grounds that it infringed the freedom of movement principles on the basis of the EU’s internal market. Here, a logic of difference sought to disarticulate these actors from the equivalential chain binding disparate actors within the public health discourse and to domesticate the interests within the industry favorable discourse through a process of ‘rhetorical redescription’ (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007; Skinner Citation2002). The latter involved changing the ‘evaluative-descriptive’ (Skinner Citation2002) tenor of alcohol policy to position the latter as being a trade or constitutional issue – relating to Scotland’s position within the Union – rather than an (explicitly Scottish) health issue.

Aware that some form of intervention on price was becoming politically more likely, industry actors sought to shift the policy from MUP to other forms of price-based interventions such as taxation (Holden and Hawkins Citation2012). The motivation for this was twofold. Firstly, fiscal measures such as bans on the sale of alcohol below the level of duty and VAT were likely to lead to less significant increases in product price across a smaller number of products than MUP and therefore lower reductions in sales. Second, taxation remained a reserved competence decided at Westminster and the industry made the calculation that it would be less likely that the Conservative-led coalition government would introduce such measures for the entire UK (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2021). As with the SWA’s legal challenge, this represented an attempt to rearticulate the boundaries of the relevant policy community from Scotland to the UK level.

Attempts to emphasize the place of Scotland within the UK, and the effectiveness of collective UK-wide decision-making, had a wider significance in the context of the constitutional politics of the post-devolution UK and the SNP’s decision to hold an independence referendum in 2014. While it was widely believed the electorate would vote to remain within the UK, the issue of independence became (and remains) a key fault line in Scottish politics. Thus, whilst the SNP government’s attempt to position alcohol policy as a wedge issue – emphasizing the rationale for Scottish independence and the effectiveness of autonomous policy action to address deeply sedimented social problems – the alcohol industry counter-discourse attempted to domesticate both positions by subordinating a logic of nationalism to a logic of economic rationality and efficiency.

Policy ‘spillover’: MUP in England

The adoption of MUP in Scotland created normative pressure for administrations elsewhere in the UK to follow suite and adopt similar measures (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019a). In a widely unexpected move, the UK Government included a commitment to introduce MUP in England in its 2012 alcohol strategy. The ministerial statement to parliament in July 2013, which indefinitely delayed the measures, cited a lack of evidence in support of the policy and the need to resolve outstanding legal issues related to the Scottish legislation before moving forward. Thus, the counter hegemonic strategies of the industry, which managed to delay MUP in Scotland, appeared to play an important role in preventing policy ‘spillover’ to the most populous and economically significant part of the UK by removing a potential source of real-world evidence for the policy and creating doubt about its legality, until the political momentum for the policy had dissipated and window of opportunity for its introduction closed (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019a).

Understanding the dynamics of the MUP debate south of the border, however, requires us to take into account the wider alcohol policy context in England at the time (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019a). The PHRD, and within it the Responsibility Deal Alcohol Network (RDAN), created a co-regulatory framework that brought together government, civil society, and industry actors around a series of voluntary commitments designed to address diet, obesity, physical inactivity, and alcohol-related harms (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019c). This had a structuring effect on the entire policy space and served to buttress key tenets of the industry-favorable discourse (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019c). It reinforced the idea that policy solutions should be the product of co-decision between government and policy stakeholders and placed the industry in the subject position of being a policy actor as opposed to the object of policy. In addition, it created an equivalence between participants from the public health arena and the industry, placing them on an equal footing as partners within a government-sanctioned network and assigning them specific public health competencies.

The voluntary nature of the RDAN reduced the scope for action to a highly circumscribed range of policy alternatives amenable to self-regulation, such as commitments to labeling, public education, and product reformulation. Discussion of price interventions, for example, were off the agenda as these could lead to accusations of collusion in anti-competitive practices (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019c). The result was a policy program in which industry-amenable measures were rearticulated as comprehensive actions to meet public health priorities, while unfavored measures were deemed to be out of scope (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019c).

Although health bodies were placed formally on an equal footing with industry actors, the reality of the RDAN was that the key concerns of the former were largely ignored, while their presence in the network conferred vicarious legitimacy on industry actors (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019c). Following the government’s decision to indefinitely delay the introduction of MUP in England in 2013, the public health organizations withdrew from the network (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019a). Outside of its structure, health bodies were further marginalized from policy development and governmental engagement, while industry actors continued to enjoy structured and formalized channels of governmental engagement, which reinforced their claimed position as legitimate policy actors committed to public health (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2019c).

The concepts of dislocation, projected social logics, and the logic of equivalence were employed to explain the emergence of a hegemonic public health discourse in Scotland to challenge the preceding policy equilibrium. Political logics were further employed to capture and explain how the counter-hegemonic practices of industry actors – domesticating insurgent demands within the dominant industry-favorable discourses via a logic of difference – where employed to stymie challenges to the status quo.

New policy regimes and the fantasmatic logics of the industry-favorable discourse

Industry discourses are underpinned by fantasmatic support structures, which serve to recruit and hold adherents to their particular articulation of the social world. The fantasmatic component of discourse may have both ‘beatific’ and/or ‘horrific’ dimensions (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). The former functions by offering an account of an ideal future to come once a particular obstacle to its realization is overcome, or an opponent vanquished. The latter functions in terms of a loss, tragedy, or humiliation, which will come to pass if the political project is not realized. Given that the industry's objective in the MUP debates was to oppose the introduction of new measures, the fantasmatic logics underpinning them took the form of horrific projections of the potential future.

Industry opposition to MUP is often articulated in terms of fairness and social justice, most notably that the increases in price would unnecessarily penalize the ‘moderate majority’ of drinkers, and particularly those on low incomes (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013; Holden and Hawkins Citation2012). Because these groups were apparently not experiencing personal harm or contributing to social problems, the industry argued, they did not deserve to be punished by a catch-all policy. This narrative within the industry-favorable discourse projects a horrific scenario in which ordinary people will be impoverished or denied their simple pleasures in life through the introduction of a poorly thought-out and untargeted policy.

This argument was linked to the idea that MUP would be ‘the thin end of the wedge’ or a ‘slippery slope’ leading to similarly inequitable policies to be adopted in other areas (e.g. food products), or more draconian forms of intervention in the alcohol sector, which would further undermine individuals’ freedom (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013; Dobson and Hawkins Citation2016). Instead, better enforcement of existing laws – particularly those associated with drunk driving and underage consumption – was promoted as being sufficient to address alcohol-related harms. A similar argument was that MUP constituted an unacceptable intervention in the functioning of the market economy that prevents competition, and thus reduces innovation and consumer choice (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). At times, it was suggested that this reflected an anti-capitalist and illiberal tendency among many public health advocates and policy-makers. The idea that MUP represents a threat to personal liberty reinforces the horrific dimension of industry-favored discourse by presenting MUP as facilitating a dystopian future in which individual choice and autonomy are eroded by the state.

Glynos and Howarth (Citation2007) identified internal contradictions as a key marker of fantasmatic logics within a discursive formation. There appears to be a number of tensions between the different industry claims. For example, they argued that MUP was unacceptably illiberal while at the same time advocating more robust enforcement of existing laws, which would require significant additional powers to intervene in citizens’ lives (e.g. the increased ability for police to stop and test motorists’ blood alcohol level). Moreover, the costs of enforcement would need to be paid through public funds thus placing further obligations on taxpayers.

Elsewhere, it was argued that MUP was a ‘blunt instrument’ which would be ineffective in addressing alcohol-related harm while leading to negative externalities (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). The alleged unintended consequences of MUP included an increase in contraband alcohol or the use of online and cross-border shopping to circumvent the restrictions and so the UK needed a single pricing. This was seen as an attempt to shift the locus of decision-making from Edinburgh to London (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). The contradiction here is evident as the policy is argued to be both ineffective in shifting purchasing and consumption and, at the same time, so effective that people would shift to other sources of alcohol to circumvent the (relatively modest) price increases resulting from the policy to such a degree that an alternative policy regime is needed to mitigate these effects.

The example of Scandinavia was cited by industry actors since these countries have high alcohol prices – secured through the tax regime and national distribution monopolies – but experience enduringly high levels of alcohol-related harm and external purchasing from neighboring states with lower alcohol prices (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013). At other times, however, industry actors suggest that data generated from other settings, such as the US, but also Scandinavia, cannot be used to justify MUP because of important cultural and historical differences between these countries and Scotland (Hawkins and Holden Citation2013).

While industry actors frequently articulate a firm commitment to the ideal of evidence-based policy-making, they are highly selective in their use of evidence and their appraisal of the strength of evidence depending on whether it supports their favored measures (McCambridge, Hawkins, and Holden Citation2013). Concerns about the effectiveness of MUP and the supporting evidence base gained significant currency within the MUP debate and the Scottish Government felt the need to counter these directly in the development of its legislation. This led to the establishment of robust evaluation mechanisms, with industry participation, and the inclusion of a ‘sunset clause’ in the legislation to enact MUP, whereby the MUP needs to be renewed by a vote of the Scottish Parliament 5 years after its legal commencement (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020, Citation2021). The mere existence of a sunset clause in the MUP bill – an infrequent component of Scottish and UK legislation – had great symbolic importance for the policy debate. It signaled both the abnormal or exceptional nature of the measures enacted and the potential dangers it posed, which required a ‘safety net’ such as this.

The argument that the government may legislate in haste but repent at leisure was also associated with claims that MUP may be illegal or open to challenge. From the very outset, the likelihood of a legal challenge to MUP was openly discussed by the industry and had a structuring effect on the policy debate (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020). The implications this would have for government resources and the potential to divert attention from other policy concerns created additional pressure to drop or delay the proposals. However, these were not inevitable consequences of the policy and only existed because the industry themselves chose to oppose the legislation in the most robust way possible. The prospect of litigation was also relevant to the inclusion of a sunset clause in the legislation as it was felt that it may offer additional protection for the policy when scrutinized in court (Hawkins and McCambridge Citation2020, Citation2021). As such, industry discourses sought to paint a ‘horrific’ picture of the effects of MUP that sought to undermine the political acceptability of the project. While it failed to prevent the policy’s introduction in Scotland, it succeeded in weakening policy through the inclusion of a sunset clause and contributed to its abandonment in England.

Conclusions

The analytical lens provided by the CLA contributes potentially important new insights into our understanding of UK alcohol policy debates. The article began by problematizing the contribution of previous interpretative studies of the policy process and the framing strategies of industry actors. Through the concepts of social, political, and fantasmatic logics, it then articulates an alternative account of the policy process informed by the ontological assumptions of PSDT. Social logic was employed to define the contours of an industry-favorable discourse that represented a highly sedimented policy equilibrium across the UK up to 2008. The concept of an emerging social logic was used to chart the emergence of an alternative public health discourse, which was contested by alcohol industry actors who sought to reassert the status quo ante through counter-hegemonic practices. Through the application of political logics, it was possible to capture the new equivalences constructed between actors within the emerging public health discourse, and the countervailing attempts by industry actors to undermine these equivalential chains, and to domesticate actors’ demands and identity positions within the prevailing order through a logic of difference. Fantasmatic logics, meanwhile, help account for the emotive force of their arguments and the hold they establish over policy makers and other adherents, allowing for a greater understanding of why change did or did not occur.

The application of the CLA seeks to deepen our understanding of the corporate political activities of the alcohol industry during a period of great dislocation, and the emergence of new policy regimes that posed significant potential threats to its business interests. It sought to highlight the synergistic and adaptive aspects of industry strategies – how they interact and exploit specific contexts and developments – and, in so doing, to provide a more comprehensive explanation than can be derived from previous, more static interpretative and framing analyses. CLA is not just an analytical toolkit. The underlying ontology provided by PSDT enables discourse-theorists to move beyond ‘thick descriptions’ of the policy space to offer explanatory accounts of policy change and policy stasis. While framing accounts are able to capture different policy actors’ interventions in the policy process – their account of the policy problem and their favored solutions – from a CLA perspective, these are reconceptualized as forms of articulatory practice in which these policy actors shape contours of the policy spaces in which they are embedded. As such, it offers a more theoretically developed account of policy influence and policy change than that offered by framing approaches.

In addition to the explanatory power of the CLA, it opens up space for critique of the prevailing social order and power relations embedded within these. The ethical dimension of the CLA serves to reveal the contingency of even highly sedimented policy discourses and thus the potential for their rearticulation via competing discursive formations, as occurred in Scotland. At the same time, it offers the conceptual vocabulary to understand how potentially dislocatory forces can be offset or subsumed into the prevailing social order as occurred in England, suturing over the fissures emerging in the dominant policy discourse and maintaining the previous policy equilibrium.

The relevance of this article is not limited to the specific case of UK alcohol policy, but seeks to contribute to the wider field of research on the commercial determinants of health and corporate political activity in health policy-making (Mialon Citation2020; De Lacy-Vawdon and Livingstone Citation2020). This paper aims to introduce public health scholars to the potential contribution of PSDT and the CLA to understanding the political dynamics and opening potential spaces for challenges and contestations in other policy areas. The example of Scotland underlines that it is possible to challenge the apparent inevitability and necessity of even deeply sedimented policy discourses through the reactivation of political logics in ways that reveal their contingency and facilitate the articulation of alternative agendas (see Quennerstedt, Mccuaig, and Mårdh Citation2021; Papanastasiou Citation2019.). However, the failure to implement MUP in England offers a note of caution, underlining the ‘stickiness’ of established policy regimes and their constitutive ideas, such as self-regulation, as well as the effectiveness of conservative counter-hegemonic practices (see Glynos and Howarth Citation2008; Glynos, Speed, and West Citation2014; Remling Citation2018). The concept of fantasmatic logics, meanwhile, contributes to the development of existing theoretical frameworks, providing a deeper explanation of the power and effects of ‘dystopian narratives’ (Ulucanlar et al. Citation2016) and how these may be contested.

The current article represents a starting point for the deployment of the CLA in this area and raises a number of issues for further analysis, which cannot be adequately discussed within the confines of the current article. For example, CLA can strengthen the explanatory power of future studies in this area by challenging the reductionist and overly rationalist conceptualizations of policy-making, which informs much of the commercial determinants of health literature. The underlying assumptions of PSDT raise questions about how we should theorize corporations as political actors and the origins of industry interests within an anti-foundationalist ontology. What implications does this have for the assumed immutability of these interests – grounded in an implicit economic determinism – that informs much public health scholarship and the inevitable conflicts of interests this implies for industry involvement in policy-making? These questions require careful engagement between these bodies of scholarship to develop more nuanced and theoretically rich accounts of public health, policymaking, and the role of power than current conceptual frameworks permit. Much more can also be said about the ethical-normative dimension of policy debates and the critical insights, which can be derived by public health scholars from post-structuralist approaches.

In summary, this article offers important insights into recent developments in UK alcohol policy through the application of a new theoretical and analytical lens. Moreover, it demonstrates how PSDT and the CLA can provide important insights and explanatory ‘tools’ for those researching policy stasis and policy change and in other highly sedimented policy spaces involving powerful commercial interests while expanding the application of the CLA to a new policy context: the commercial determinants of health. It is hoped to serve as a catalyst for further reflection on the relevance of PSDT for this field of studies and the additional insights it may bring.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Benjamin Hawkins

Benjamin Hawkins is Senior Research Associate at the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge. His work focuses on the political economy and regulation of alcohol and tobacco at the national, regional, and global levels, including the implications of international trade and investment agreements and European single market laws for national health policies. His work uses qualitative research methods including semi-structured interviews and documentary analysis and draws on a range of theoretical approaches including frmaing and discourse theory.

May CI van Schalkwyk

May CI van Schalkwyk is a medical doctor and entered specialty training in August 2016 as a Public Health Specialty Registrar and NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow. She has conducted research on trade governance and health, and the commercial determinants of health. She has published on Brexit, trade policy governance, as well as on the tobacco, alcohol, and gambling industries, including on the activities of industry formed and funded organizations.

References

- Behagel, J. H., and A. Mert. 2021. “The Political Nature of Fantasy and Political Fantasies of Nature.” Journal of Language and Politics 20 (1): 79–94. doi:10.1075/jlp.20049.beh.

- Clarke, M. 2012. “Talkin’‘bout a Revolution: The Social, Political, and Fantasmatic Logics of Education Policy.” Journal of Education Policy 27 (2): 173–191. doi:10.1080/02680939.2011.623244.

- DE Lacy-Vawdon, C., and C. Livingstone. 2020. “Defining the Commercial Determinants of Health: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 20 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09126-1.

- Dobson, L., and B. Hawkins. 2016. “The Idea of Freedom in the Policy Debate on the Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol.” Journal of Social Philosophy 47 (1): 41–54. doi:10.1111/josp.12142.

- Durnová, A. 2022. “Making Interpretive Policy Analysis Critical and Societally Relevant: Emotions, Ethnography and Language.” Policy & Politics 50 (1): 43–58. doi:10.1332/030557321X16129850569011.

- Fooks, G. J., S. Williams, G. Box, and G. Sacks. 2019. “Corporations’ Use and Misuse of Evidence to Influence Health Policy: A Case Study of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation.” Globalization and Health 15 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1186/s12992-019-0495-5.

- Glynos, J. 2021. “Critical Fantasy Studies.” Journal of Language and Politics 20 (1): 95–111. doi:10.1075/jlp.20052.gly.

- Glynos, J., and D. Howarth. 2007. Logics of Critical Explanation in Social and Political Theory. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Glynos, J., and D. Howarth. 2008. “Critical Explanation in Social Science: A Logics Approach.” Swiss Journal of Sociology 34 (1) : 5–35 .

- Glynos, J., R. Klimecki, and H. Willmott. 2015. “Logics in Policy and Practice: A Critical Nodal Analysis of the UK Banking Reform Process.” Critical Policy Studies 9 (4): 393–415. doi:10.1080/19460171.2015.1009841.

- Glynos, J., and E. Speed. 2012. “Varieties of Co-Production in Public Services: Time Banks in a UK Health Policy Context.” Critical Policy Studies 6 (4): 402–433. doi:10.1080/19460171.2012.730760.

- Glynos, J., E. Speed, and K. West. 2014. “Logics of Marginalisation in Health and Social Care Reform: Integration, Choice, and Provider-Blind Provision.” Critical Social Policy 35 (1): 45–68. doi:10.1177/0261018314545599.

- Glynos, J., and Y. Stavrakakis. 2008. “Lacan and Political Subjectivity: Fantasy and Enjoyment in Psychoanalysis and Political Theory.” Subjectivity 24 (1): 256–274. doi:10.1057/sub.2008.23.

- Griggs, S., and D. Howarth. 2019. “Discourse, Policy and the Environment: Hegemony, Statements and the Analysis of U.K. Airport Expansion.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 464–478. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2016.1266930.

- Hawkins, B. 2015. “Fantasies of Subjugation: A Discourse Theoretical Account of British Policy on the European Union.” Critical Policy Studies 9 (2): 139–157. doi:10.1080/19460171.2014.951666.

- Hawkins, B. 2022. Deconstructing Brexit Discourses. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hawkins, B., and C. Holden. 2013. “Framing the Alcohol Policy Debate: Industry Actors and the Regulation of the UK Beverage Alcohol Market.” Critical Policy Studies 7 (1): 53–71. doi:10.1080/19460171.2013.766023.

- Hawkins, B., and C. Holden. 2014. “‘Water Dripping on stone’? Industry Lobbying and UK Alcohol Policy.” Policy & Politics 42 (1): 55–70.

- Hawkins, B., C. Holden, and J. McCambridge. 2012. “Alcohol Industry Influence on UK Alcohol Policy: A New Research Agenda for Public Health.” Critical Public Health 22 (3): 297–305. doi:10.1080/09581596.2012.658027.

- Hawkins, B., and J. McCambridge. 2014. “Industry Actors, Think Tanks, and Alcohol Policy in the United Kingdom.” American Journal of Public Health 104 (8): 1363–1369. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301858.

- Hawkins, B., and J. McCambridge. 2019a. “Policy Windows and Multiple Streams: An Analysis of Alcohol Pricing Policy in England.” Policy & Politics 48 (2): 315–333. doi:10.1332/030557319X15724461566370.

- Hawkins, B., and J. McCambridge. 2019b. “Public-Private Partnerships and the Politics of Alcohol Policy in England: The Coalition Government’s Public Health ‘Responsibility Deal’.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 1477. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7787-9.

- Hawkins, B., and J. McCambridge. 2019c. “Public-Private Partnerships and the Politics of Alcohol Policy in England: The Coalition Government’s Public Health ‘Responsibility Deal’.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7787-9.

- Hawkins, B., and J. McCambridge. 2020. “‘Tied Up in a Legal mess’: The Alcohol Industry’s Use of Litigation to Oppose Minimum Alcohol Pricing in Scotland.” Scottish Affairs 29 (1): 3–23. doi:10.3366/scot.2020.0304.

- Hawkins, B., and J. McCambridge. 2021. “Alcohol Policy, Multi-Level Governance and Corporate Political Strategy: The Campaign for Scotland’s Minimum Unit Pricing in Edinburgh, London and Brussels.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 23 (3): 391–409. doi:10.1177/1369148120959040.

- Holden, and B. Hawkins. 2012. “‘Whisky gloss’: The Alcohol Industry, Devolution and Policy Communities in Scotland.” Public Policy and Administration 28 (3): 253–273. doi:10.1177/0952076712452290.

- Holden, C., B. Hawkins, and J. McCambridge. 2012. “Cleavages and Co-Operation in the UK Alcohol Industry: A Qualitative Study.” BMC Public Health 12 (1): 483. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-483.

- Howarth, D. 2000. Discourse. Buckingham: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Howarth, D. 2010. “Power, Discourse, and Policy: Articulating a Hegemony Approach to Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 3 (3–4): 309–335. doi:10.1080/19460171003619725.

- Howarth, D. 2013. Poststructuralism and After. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Howarth, D., J. Glynos, and S. Griggs. 2016. “Discourse, Explanation and Critique.” Critical Policy Studies 10 (1): 99–104. doi:10.1080/19460171.2015.1131618.

- Howarth, D., and S. Griggs. 2006. “Metaphor, Catachresis and Equivalence: The Rhetoric of Freedom to Fly in the Struggle Over Aviation Policy in the United Kingdom.” Policy and Society 25 (2): 23–46. doi:10.1016/S1449-4035(06)70073-X.

- Hurt, R. D., J. O. Ebbert, M. E. Muggli, N. J. Lockhart, and C. R. Robertson. 2009. “Open Doorway to Truth: Legacy of the Minnesota Tobacco Trial.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 84 (5): 446–456. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60563-6.

- Jernigan, D. H. 2009. “The Global Alcohol Industry: An Overview.” Addiction (Abingdon, England) 104 (Suppl): 6–12. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02430.x.

- S. V. Katikireddi, L. Bond, and S. Hilton. 2014. “Changing Policy Framing as a Deliberate Strategy for Public Health Advocacy: A Qualitative Policy Case Study of Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol.” The Milbank Quarterly 92 (2): 250–283. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12057.

- Katikireddi, V., and S. Hilton. 2015. “How Did Policy Actors Use Mass Media to Influence the Scottish Alcohol Minimum Unit Pricing Debate? Comparative Analysis of Newspapers, Evidence Submissions and Interviews.” Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 22 (2): 125–134. doi:10.3109/09687637.2014.977228.

- S. V. Katikireddi, S. Hilton, C. Bonell, and L. Bond. 2014. “Understanding the Development of Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol in Scotland: A Qualitative Study of the Policy Process.” PLoS One 9 (3): e91185. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091185.

- Koon, A. D., B. Hawkins, and S. H. Mayhew. 2016. “Framing and the Health Policy Process: A Scoping Review.” Health Policy and Planning 31 (6): czv128. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv128.

- Laclau, E. 2005. On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

- Laclau, E., and C. Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

- Lauber, K., D. Mcgee, and A. B. Gilmore. 2021. “Commercial Use of Evidence in Public Health Policy: A Critical Assessment of Food Industry Submissions to Global-Level Consultations on Non-Communicable Disease Prevention.” BMJ Global Health 6 (8): e006176. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006176.

- McCambridge, J., B. Hawkins, and C. Holden. 2013. “Industry Use of Evidence to Influence Alcohol Policy: A Case Study of Submissions to the 2008 Scottish Government Consultation.” PLoS Medicine 10 (4): e1001431. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001431.

- McCambridge, J., B. Hawkins, and C. Holden 2014. The Challenge Corporate Lobbying Poses to Reducing Society’s Alcohol Problems: Insights from UK Evidence on Minimum Unit Pricing. Addiction [Online]. Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.12380/full.

- McCambridge, J., K. Kypri, P. Miller, B. Hawkins, and G. Hastings 2013. Be Aware of Drinkaware. Addiction [Online]. Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.12356/full.

- McCambridge, J., and M. Mialon. 2018. “Alcohol Industry Involvement in Science: A Systematic Review of the Perspectives of the Alcohol Research Community.” Drug and Alcohol Review 37 (5): 565–579. doi:10.1111/dar.12826.

- McCambridge, J., M. Mialon, and B. Hawkins. 2018. “Alcohol Industry Involvement in Policymaking: A Systematic Review.” Addiction 113 (9): 1571–1584. doi:10.1111/add.14216.

- Mialon, M. 2020. “An Overview of the Commercial Determinants of Health.” Globalization and Health 16 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1186/s12992-020-00607-x.

- Mialon, M., and J. McCambridge. 2018. “Alcohol Industry Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives and Harmful Drinking: A Systematic Review.” European Journal of Public Health 28 (4): 664–673. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky065.

- Michaels, D. 2020. The Triumph of Doubt: Dark Money and the Science of Deception. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Papanastasiou, N. 2019. Revealing Market Hegemony through a Critical Logics Approach: The Case of England’s Academy Schools Policy. In Education Governance and Social Theory: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Research editetd by Wilkins, A., & Olmedo, A., 123–138.

- Proctor, R. 2011. Golden Holocaust: Origins of the Cigarette Catastrophe and the Case for Abolition. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ of California Press.

- Quennerstedt, M., L. McCuaig, and A. Mårdh. 2021. “The Fantasmatic Logics of Physical Literacy.” Sport, Education and Society 26 (8): 846–861. doi:10.1080/13573322.2020.1791065.

- Remling, E. 2018. “Depoliticizing Adaptation: A Critical Analysis of EU Climate Adaptation Policy.” Environmental Politics 27 (3): 477–497. doi:10.1080/09644016.2018.1429207.

- Runfors, A., M. Saar, and F. Fröhlig. 2021. “Policy Experts Negotiating Popular Fantasies of ‘Benefit Tourism’policy Discourses on Deservingness and Their Relation to Welfare Chauvinism.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 20 (4): 1–14. doi:10.1080/15562948.2021.1933670.

- Scottish Government 2008. Changing Scotland’s Relationship with Alcohol: A Discussion Paper on Our Strategic Approach [Online]. Available: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/227785/0061677.pdf.

- Skinner, Q. 2002. Visions of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Speed, E., and R. Mannion. 2020. “Populism and Health Policy: Three International Case Studies of Right-wing Populist Policy Frames.” Sociology of Health & Illness 42 (8): 1967–1981. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.13173.

- Ulucanlar, S., G. J. Fooks, A. B. Gilmore, and T. E. Novotny. 2016. “The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity.” PLoS Medicine 13 (9): e1002125. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002125.

- Ulucanlar, S., G. J. Fooks, J. L. Hatchard, A. B. Gilmore, and W. D. Hall. 2014. “Representation and Misrepresentation of Scientific Evidence in Contemporary Tobacco Regulation: A Review of Tobacco Industry Submissions to the UK Government Consultation on Standardised Packaging.” PLoS Medicine 11 (3): e1001629. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001629.

- van Hulst, M., and D. Yanow. 2016. “From Policy “Frames” to “Framing” Theorizing a More Dynamic, Political Approach.” The American Review of Public Administration 46 (1): 92–112. doi:10.1177/0275074014533142.

- van Schalkwyk, M. C., B. Hawkins, and M. Petticrew. 2022. “The Politics and Fantasy of the Gambling Education Discourse: An Analysis of Gambling Industry-Funded Youth Education Programmes in the United Kingdom.” SSM-Population Health 18: 101122. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101122.

- van Schalkwyk, M. C., N. Maani, M. Mckee, S. Thomas, C. Knai, M. Petticrew, and Q. Grundy. 2021. ““When the Fun Stops, Stop”: An Analysis of the Provenance, Framing and Evidence of a ‘Responsible Gambling’campaign.” PLoS One 16 (8): e0255145. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255145.

- Yanow, D. 2007. “Interpretation in Policy Analysis: On Methods and Practice.” Critical Policy Analysis 1 (1): 110–122. doi:10.1080/19460171.2007.9518511.