Abstract

Previous studies have shown that limited understanding of the social needs and capabilities of specific places and communities present limitations in the progression of public policy and strategic response to climate change risks. Social capital, a mutually beneficial collective action found in communities to different extents, has the potential to facilitate urban vulnerability reduction necessary for climate change adaptation. This article explores how the notion of social capital can attain new relevance by motivating the initiation and accomplishment of measures to overcome climate change risks facing coastal East African cities. Building on the existing conceptualization of social capital and associated concepts in climate change theory and policy, this article demonstrates how, within a social capital framework, the analysis of risk and adaptation can move away from a purely top-down focus on formal organizational capacity towards an acknowledgment of the importance of informal social networks in the final directing of flow of activities as well as policy enactment. This article finds that a strong tradition of collaboration, trust and reciprocal relationships between local resource-oriented groups in the cities of Mombasa and Dar es Salaam can be leveraged to generate material interventions directed at reducing vulnerability to climate variability and change.

1. Introduction

Projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicate that developing countries and their cities are among those regions at greatest risk to the impacts of climate change (Parry et al. Citation2007). However, the governance dimensions of these cities indicate a limited capacity to deal with the impacts as well as a limited potential to perceive climate change as a salient risk issue that warrants immediate action. African cities, especially those situated along the coast, are expected to be affected in numerous ways by climate change (Ibe and Awoski Citation1991, Mahongo Citation2006, Dossou and Dossou Citation2007). In view of these impending risks, individuals as well as city decision-makers will have to identify and implement adaptation strategies to deal with the impacts of a warming climate (see Scott et al. Citation2001, Moser Citation2006), albeit with only a limited capacity to do so. One of the most common and practical resources that would contribute to the design and facilitation of adaptation responses that are specific to the needs and circumstances of cities is the concept of social capital.

There has been a rapid growth in reference to the term ‘Social Capital’ in recent years. The term captures the idea that social bonds and norms are important for sustainable livelihoods. Coleman (Citation1990) describes it as ‘the structure of relations between actors and among actors’ that encourages productive activities, but it is Putnam (Citation1995, Citation2000) who brought it into wider use. It has been shown to have relevance for facilitating the effective application of a range of public policies in communities and places. For example, a comparative study of the role of local institutions in Bolivia, Burkina Faso and Indonesia demonstrated empirically that social capital embedded in local associations makes significant contributions to household welfare and poverty reduction (see Grootaert Citation2001).

This article explores the significance of social capital and its potential in providing practical resources that can be used to generate material interventions for building adaptive capacity in the coastal cities of Mombasa and Dar es Salaam. The allure of social capital is premised on the fact that any group of people or community that can organize themselves to work together to meet new challenges has a precious resource called ‘social capital’, which they can use to realize mutual benefits. The application of social capital in this study takes into account its conceptual confusion (see Mohan and Mohan Citation2002). I use the concept here to refer to the resource of collective action found in those associations that are embodied in resource-oriented groups with the capacity to deliver on mutual environmental benefits, but not that which are embodied in groups such as sports clubs, denominational churches, parents–teachers associations and other similar groups.

In exploring the significance of the social capital concept in the context of climate change, the article first brings into focus some of the conceptual issues that are relevant to climate change adaptation. It then discusses the importance of adaptation strategies and opportunities created by social capital as well as the reasons for privileging the social capital resource over other adaptation options. The study is based on an extensive fieldwork conducted in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam in 2008 and 2009. This fieldwork entailed qualitative research including interviews with local community group members, key informants and documentary review. Key informants interviewed included national and city-level officials, Non-Governmental Organization representatives and representatives from the Semi-Autonomous Government Agencies.

2. Conceptual terms in climate change adaptation science

The study of climate change and its implications has acquired the use of concepts such as adaptation, vulnerability, adaptive capacity, risks and resilience, whose array of sometimes loose definitions is frequently lost in the course of growing multidisciplinary discourses. These concepts have real inter-relationships and not just juxtapositions in their application to climate change and the way in which its implications are shaped through social relations as I show in this section. I further show that social capital has the potential to build resilience and adaptive capacity resulting in reduced vulnerability of the city systems to climate change.

2.1. Defining vulnerability and adaptation

A summarized definition of climate change vulnerability from literature is given by Dodman et al. (Citation2009a) as the measure of the degree to which a human or natural system is unable to cope with adverse effects, including climate variability and extremes. On the other hand, the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report emphasizes that adaptation comprises actions that reduce vulnerability or enhance resilience (Adger et al. Citation2007). Similarly, adaptive capacity has been defined as the ability of countries, communities, households and individuals to adjust in order to reduce vulnerability to climate change, moderate potential damage, cope with and recover from the consequences and the ability of a system to evolve in order to accommodate environmental hazards or policy change and to expand the range of variability with which it can cope by [Tyndall Centre for Climate change research (Citation2006), Lim (Citation2005) and Adger (Citation2006), respectively].

It is important to note that in some instances, adapting to climate changes may even exacerbate vulnerability. For example, if the needed adaptation actions to food insecurity for the coastal urban poor will lead to dependence of credit schemes to practice mari-culture,Footnote1 aquaculture, silvo-fisheriesFootnote2 or engage in other livelihood activities, coastal flooding will not only leave people without any source of income but will also leave them in debt. Therefore, some adaptation measures may solve one problem while creating another, and it might be necessary to ‘adapt to the adaptation’ (Mertz et al. Citation2009). According to Smit and Wandel (Citation2006), when extreme events go beyond the coping range, the adaptive capacity may be surpassed and the system threatened. At this point, required adaptation is beyond the capacity of the people experiencing the threat and assistance is needed. In this case, adaptation becomes the means by which adaptive actions necessary for establishing the coping range take place, eventually reducing vulnerability to climate change risks.

Understanding the difference between taking adaptation measures and building adaptive capacity is very crucial for city decision-makers, not only in East Africa but also in developing countries, where adaptive capacity is limited by resources, weak institutions, poor/inadequate infrastructure and poor governance. The extent to which adaptation measures can be adopted by vulnerable groups depends on their adaptive capacity. It may therefore be useful to view adaptation along a continuum from discrete adaptation measures undertaken by various stakeholders but geared towards building adaptive capacity ().

These very diverse set of adaptation actions are stimulated by policy influences originating from many sectors. The key benefit of using social capital in this case is the legitimacy aquired by the whole process of planning, management and implementation of these discrete actions.

2.2. Defining risk and resilience

Risk in climate science has been defined as the probability of a particular climate outcome multiplied by the consequences of that outcome (Pittock Citation2003). Climate change risks may result from hazards acting on their own or together with other factors and can be addressed through mitigation and adaptation. It must however be remembered that the relationship between vulnerability and risk is not cumulative, which means that while reduced vulnerability always means reduced outcome risk, reducing outcome risk does not always reduce vulnerability (Sarewitz et al. Citation2003). For example, building strong structures and living in safer areas in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam cities will reduce losses from flooding, but reducing losses from flooding does not necessarily reduce vulnerability of the cities' residents. In other words, vulnerability to climate risks is related to the social frailties of the vulnerable communities.

Godschalk et al. (Citation1998) simply describe resilient communities as being capable of bending but unable to break when disasters strike. Adger (Citation2000), on the other hand, defines social resilience as the ability of groups or communities to adapt in the face of external social, political or environmental stress and disturbance. However, the ecological literature has moved to using the term adaptive capacity subsuming resilience in the definition.

Resilience is enhanced by reducing vulnerability. For example, when a group of people living in a slum built on a flood plain are collectively involved in undertaking embankment or building drainage channels they are enhancing their resilience. In this case, climate change offers an opportunity for the community to build resilience to adapt to stressors. Viewed through the social capital frame, community resilience is underpinned by individual community members acting collectively to achieve a mutually beneficial outcome. The emergent action from such community action has the ability to positively alter the outcome of major external perturbations such as flooding (see Gibbs Citation2009). At the same time, while vulnerability reduction enhances resilience, vulnerability signifies low levels rather than lack of resilience as each system has some inherent capacity to recover from perturbations (Siambalala Citation2006). For example, despite the enormity of obstacles in East African cities, the inhabitants continue to exhibit exceeding resilience in adapting survival strategies. However, this resilience will have its limits (low level) in the phase of predicted climate change impacts, hence the need to identify measures to facilitate adaptation. Dodman et al. (Citation2009a) sum up the relationship between the three concepts by stating that vulnerability is the basic condition that makes adaptation and resilience necessary.

3. Why are adaptation strategies for Mombasa and Dar es Salaam cities necessary?

Adaptation to climate change is considered especially relevant for coastal cities in developing countries, where societies are already struggling to meet the challenges posed by the existing climate variability (Gibbs Citation2009). In this article, the significance of the development of adaptation measures in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam has been grouped into the following five categories:

3.1. What climate impact science says about East African coasts

East Africa is predicted to warm by 2–4°C by 2100. In the coastal areas, rainfall is predicted to increase by 30–50%. This increased mean rainfall coupled with its cyclical variations is likely to result in more frequent and severe flooding. Sea level is predicted to rise by 0.10–0.90 m, and this is further expected to aggravate flooding (see ) with the adaptation bill rising to 10% of the gross domestic product (GDP) (see Hulme et al. Citation2001, IPCC Citation2001, Dodman et al. Citation2009b). The implication of this to the cities along the East African coast would be to pose a great risk to infrastructure, erosion of beaches, flooding of wetlands, and salt-water intrusion into fresh water aquifers causing salinization of water, thus affecting fresh water supply as well as peri-urban agriculture and fishing activities. These adverse effects would impose pressure on the already struggling economies of Kenya and Tanzania.

Figure 2. Ocean street in Dar es Salaam city will be inundated by a slight rise in sea level (e.g. 18–59 cm by 2100). Photo: Justus Kithiia.

According to current estimates, 17% or 4600 ha of land in Mombasa will be submerged with a sea level rise of 0.3 m. The city's low altitude, especially the coastal plain covering 4–6 km and lying between 0 and 45 m above sea level is an area of high vulnerability to sea level rise (Mahongo Citation2006, Awour et al. Citation2008). However, accurate data on sea level rise are complicated by the fact that tidal gauge records in the East Africa Coast region are not long enough to give conclusive evidence. For example, some of the old stations such as Mombasa have significant gaps, whereas others have been relocated, making it difficult to examine trends with certainty (Mahongo Citation2006). Huq et al. (Citation2007), citing an IPCC report on the regional impact of climate change, allude to the lack of local analysis of the scale of risks of sea level rise and storm surges in the Africa region, adding that the scale of these risks has yet to be documented.

The East African region is the least urbanized of the world but is urbanizing rapidly. It has the world's shortest urban population doubling time, from 50.6 million in 2007 to a projected 106.7 million in 2017 in less than nine years (UN Habitat Citation2008). A greater proportion of this population is expected to settle in coastal urban areas placing greater stress and impacts on social and biophysical systems as well as having serious implications for climate change ().

Table 1. African region's urbanization rates, urban and total population and growth rates. (Adapted from UN Habitat (2008).)

3.2. Recent events exposing vulnerability

The East African coastal zone is already experiencing some coastal degradation because of erosion along some sandy and low-lying beaches. In Dar es Salaam, accelerated marine erosion and flooding in the past is reported to have uprooted settlements and resulted in the abandonment of luxury beaches (see Ibe and Awoski Citation1991). In May 2008, media houses reported that strong winds had ripped off roofs of several houses in Shelly Beach with numerous houses in Magongo, Likoni and Kisauni being submerged in rainwater in Mombasa (Nation News June Citation2008). Exactly one year before this destructive event, in May 2007, similar destructions had been reported in the same city where strong winds and rain blew away roofs of 30 houses, killing five people and displacing 20 others (Kenya Television Network News May Citation2007).

In Tanzania, the 1997/1998 El Niño phenomena was associated with floods and increased sea surface temperatures; more than 100 deaths were reported and over 155,000 people were left homeless (UNEP/DGIC/URT/UDSM Citation2002). Similarly, in 1947, 1961 and 1997/1998, El Niño rains are reported to have led to loss of human lives, increased disease incidents (e.g. cholera), loss of property and destruction of houses in Mombasa. The most affected areas were those estates located near the ocean and lacking proper drainage structures. These disturbances have had significant negative implications for local economies and although they may not necessarily be linked to climate change, they expose the inherent vulnerabilities of the cities.

Recently, the National Environment Management Council in Tanzania received reports that farmers in Pemba, Pangani and Rufiji areas in greater Dar es Salaam were abandoning their farming activities because of increased water salinity. Maziwa Island located about 8 km South East of the mouth of Pangani River completely disappeared in 1978. According to Fay (Citation1992), the island was originally famous for being the most important of East Africa's nesting grounds for three endangered marine turtles.Footnote3 The island with its casuarina trees vanished because of sea level rise and/or destructive human activities. In 2001–2002, there was additional damage to the coastal reefs from threats that may be related to climate change, some of which included harmful algae blooms in both Tanzania and Kenya and unknown fungal disease of corals in Kenya and northern Tanzania (Obura et al. Citation2002)

The current framing of climate change adaptation in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)Footnote4 and in policy discourses is largely impact-driven. Even under UNFCCC, adaptation responses address the marginal impacts of climate change rather than the existing or potential climate risks. Tanzania, which is classified as a least developing country, followed the UNFCCC's approach in developing the National Adaptation Programs of Action (NAPA) in 2006. Ford (Citation2008) further explains the weaknesses of this approach by asserting that it has a tendency to under-emphasize the complex socio-economic dynamics that shape vulnerability to climate change. It is therefore unsuitable in helping to fill the gaps that exist in understanding the nature of urban vulnerabilities and the existing opportunities for adaptation. Understanding city-wide adaptive capacity means understanding the generic capacity existing in a society that enables self-protection and collective action to avert or cope with climate stressors such as flooding, temperatures changes, droughts (see Pelling and High Citation2005b). Therefore, even with the presence of UNFCCC's prescribed NAPAs in Tanzania, protecting Dar es Salaam from the impacts of climate change will require additional strategies that address the vulnerability-shaping socio-economic dynamics.

3.3. Risk in the face of socio-economic development

Mombasa and Dar es Salaam are port cities and therefore they represent important national and regional engines of economic development. They serve as major conduits of commerce between the interior regions and the rest of the world. The two cities are faced with various types of environmental impacts because of rapid development activities mostly associated with tourism, industry, urban agriculture and fishing. As a result of these economic activities, the whole East African coastal zone is heavily populated. In Tanzania, the coastal area supports approximately 25% of the population with the majority of the people living in Dar es Salaam city (Sallema and Mtui Citation2008). On the other hand, over 70% of the coastal population in Kenya relies on fisheries for their livelihood (MacClanahan Citation2007). Global sea level rise is therefore a key concern for both cities as they also contain important infrastructural facilities, e.g. ports, roads and airports.

Coastal tourism in East Africa accounts for a big proportion of the countries' GDP. In Kenya, it accounts for 10% of the GDP making it the third largest contributor to Kenya's GDP after agriculture and manufacturing (KNBS Citation2007). In Tanzania, income from the tourism sector grew from US$822 million in 2005 to US$1.3 billion in 2008 (Mwangunga Citation2009). Tourism has been identified as one of the key drivers in achieving visions of 2030 and 2025 in Kenya and Tanzania, respectively.Footnote5 But as mentioned earlier, developments associated with tourism activities have exposed these cities to various types of climate change impacts. Economic considerations have placed coastal tourism above the well-being of the coast. However, building the cities' adaptive capacity will require that the pursuit of this economic goal go hand in glove with initiatives aimed at reducing vulnerability.

3.4. Risk in the face of governance disorder

We are more concerned with cross-cutting issues such as environment and physical planning. However our roles clash with those of our colleagues in the municipalities. Well, we have similar qualifications and do the same jobs in the same city. Municipal directors in the 3 municipalities in Dar es Salaam are not obliged to follow instructions from my city director; he is not their boss. It's a little bit confusing but we are working on proper structure. (Dar es Salaam city official during the interview.)

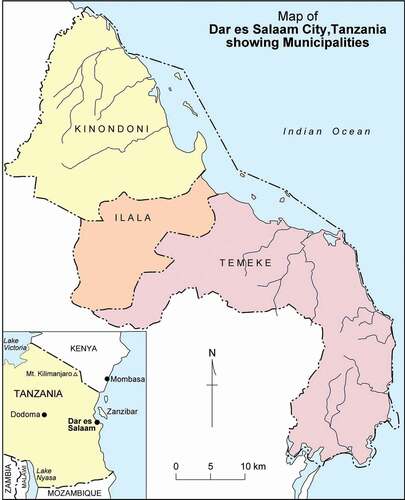

The institutional arrangements and policy instrumentation and implementation in East African cities generally reflect city systems in ‘organized’ chaos, where decisions are delayed, correspondences lost in bureaucratic black-hole and ascription of responsibility is obfuscated. The above statement by a Dar es Salaam city council official is such an example. City governance consists of institutions whose roles are either overlapping or present problems in the implementation of assigned functions. This has resulted in institutional weakness and lack of enforcement and regulation. For example, Dar es Salaam city is divided into three municipalities, namely, Kinondoni, Ilala and Temeke (), with each municipality complete with a Mayor and Director. However, there is also Dar es Salaam city council which has a Mayor and a Chief Executive Officer (Director). Although the city council is mandated to deal with cross-cutting issues, e.g. waste management and transport management, in practice the municipalities also claim responsibility for these functions. The municipalities are autonomous and are able to deal directly with the central government and other collaborators without reference to the city council. A similar scenario can be found in Mombasa where responsibilities and accountability for climate change issues among many other issues are straddled between several institutions including National Environment Management Authority, municipal Council and other government departments. Such institutional arrangements and weaknesses undermine efforts to even begin to pay attention to adaptation.

Authorities in poorly governed cities are unable to initiate and motivate measures necessary for accomplishment of climate change adaptation. For example, in both cities, local authority plans do not link changing climatic conditions with housing programmes, city development and land use management. There is little effort to address the plight of the poor living in informal settlements who are likely to experience the greatest impacts of climate change. City authorities have limitation in providing the needed protective infrastructure and services to low-income populations, yet the quality of housing and overall infrastructure is an important determinant of people's vulnerability to flooding or storms and failure to device precautionary measures through adaptation puts the population at risk. The settlement of the urban poor in some of the risky areas of the city can be attributed to poor housing programmes and lack of enforcements and regulations. Attempting to correct these failures by relocating settlers from the risky area may be a difficult task, especially if they have settled in the area for a long time. A good example is the unsuccessful eviction of squatters from the flood-prone area of Jangwani in Dar es Salaam by the city authorities. Settlers have strongly resisted eviction, with some seeking court injunctions. Therefore, risk reduction amidst climate change requires long-term holistic planning as opposed to ad hoc decisions meant to correct past mistakes.

The proliferation of local environmental action groups in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam cities may be because of government stalling on environmental issues and may have forced communities to take matters into their own hands. For example, according to records from the Mombasa district culture and social services office, there were 855 registered environmental management groups in 2008 alone. Other groups involved in garbage collection in the city were registered with the municipal council, which is symptomatic of the government's/council's inability to effectively manage environmental issues. Where government interventions in managing city systems are largely absent or ineffective, usually depicting a system in chaos, social groups in effect could take over as a substitute for external intervention (see also Bhattarai and Haming Citation2001).

3.5. Risk in the violation of human rights

Modern society has an obligation to ensure that citizens live in homes and that communities provide a basic level of protection from the threat of climate change. Therefore, the governments of Kenya and Tanzania have the responsibility to monitor the vulnerabilities of those whose rights are most at risk by addressing their vulnerabilities, e.g. those living in informal settlements, flood plains as well as those who depend on coastal resources for their livelihoods. This is in line with the international covenant on civil and political rights which state in part, ‘… in no case should a people be deprived of its own source of existence’ (UN ICCPR, Part 1 article 2 section 2, Citation1966). Failure to address both climate change mitigation and adaptation is doing exactly that; i.e. depriving people in poor countries of water, soil and land on which they subsist.

4. Rationale for using the social capital resource in facilitating climate change responses in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam cities

Although cities in the high-income countries can allocate huge resources to building their resilience to climate change effects and therefore concentrate on the ‘green agenda’ issues, those in East Africa have to simultaneously deal with the brown,Footnote6 grayFootnote7 and green agenda issues.Footnote8 At the moment, finding the best means of developing and financing urban environmental initiatives that address these agenda issues remain a major challenge for both the national governments and the local authorities. The situation in the cities is not helped by the fact that time- and space-related impacts have transformed the timing, speed and sequencing of environmental transitions such that challenges are appearing sooner, growing faster and emerging more simultaneously than those previously experienced by industrialized cities (see Keiner et al. Citation2005).

The key issue for climate change adaptation in these cities will be how well to demonstrate the links between the green, brown and gray agendas as well as other socio-economic issues so that the implications of climate change are not just seen as ‘green issues’ but also as social and economic well-being of the city residents. This will require innovative city planning keen on adopting policy trends that value the knowledge and capacities of local people and build on resources that include social capital. These are likely to be more facilitative of development initiatives leading to sustainable cities because the problems that impede socio-economic development are often the same as those that increase vulnerability to climate stress.

City planners and decision-makers in East Africa seem to view climate change through the lens of the global policy agenda, whose consequences will be in the long-term. This is evidenced by the lack of climate change response planning and/or failure to provide for climate change adaptation planning within the overall municipal development planning. Indeed, the low funding priority given to climate-related activities in both the national and the municipal budgets is a significant sign of its low political significance. The challenges posed by climate change are viewed as marginal compared with other socio-economic problems facing city planning and development, e.g. infrastructure, public health, education, housing and energy, all of which feature prominently in the municipal plans. Similarly, shifting attention from the politically correct mitigation frame to adaptation is seemingly a source of ambiguity for both the national and the city-level decision-makers with respect to guidance for city planning. However, what is important is that whatever the drivers of urban development are, these should be adjusted to make them take into account climate change risks and hence manage their growth in a manner that enhances their resilience to climate variability and change (Huq et al. Citation2007). This can only be done through robust policy instrumentation and planning processes, both at the national and at the city levels that view adaptive capacity as an emergent property of social systems, which is continuously being shaped through social relationships.

At the municipal/local authority levels, environmental planning is still aligned with models of economic efficiency and rationalization, whereas in some other instances, it is conservation at all costs. However, adaptation measures will most likely require decisions that fall outside this paradigm (see Gibbs Citation2009), mainly because adaptation processes are slow, are multi-scalar, have long time scales and involve multiple players, all of which are inconsistent with neo-liberal planning. However, social capital perspectives use endowments inherent in ‘non-state agents’ or what others have called ‘civic virtue’ thus operating outside the markets forces as well as government control mechanisms. For this reason, social capital perspectives could function as enablers to avoid static bureaucratic conceptions of administrative scale and sector to indicate the importance of social networks acting across boundaries for vulnerability reduction.

National and city governments in East Africa lack the resources to invest in infrastructure that would minimize climate change impacts. For example, according to a report from the Vice President's Office (VPO Citation2003) in Tanzania, the cost of protecting the whole coastline of Dar es Salaam (about 100 km) by building a sea wall would be US$270 billion, far beyond what the national economy can afford. It has been suggested by Thomalla et al. (Citation2006) that well-accumulated social capital has the potential to help minimize the cost of adaptation thus offering some savings to the state, although in the real sense, social capital should never be reduced to the function of saving costs. Hence, enhancing adaptation would be more successful, if it were to use pre-existing local capacities operating at an appropriate scale to address climate change risks. This calls for the initiation, support and sustenance of locally driven adaptation initiatives that seek to engage social groups and their networks as critical loci of city development.

Data describing the changing environmental conditions of places in East Africa are limited because of lack of local analysis. Moreover, even the most comprehensive climate change models provide local decision-makers with little information about the most efficient or effective way to adapt to climate change. Such information can only be based on local knowledge, and development of local knowledge requires different associations, methods and tools (Pelling and High Citation2005a, Patwardhan Citation2006). Besides, some local groups could be more resilient than modeling studies can suggest because many aspects of adaptive capacity are known to reside in networks and social capital of groups that are likely to be affected (Adger Citation2003). Therefore, using social capital in adaptation measures will mean allowing for local community initiatives to generate material interventions directed at vulnerability reduction or response to climate stressors in the city.

Already, there are many local groups in Dar es Salaam and Mombasa working on different aspects of environmental conservation/management including mangrove regeneration, solid waste management, marine protection, greening of open city spaces, seaweed production, turtle conservation, etc. The strong tradition of collaboration within and among groups and their federations, which is sustained by bonds of trust, reciprocity and connectedness existing mostly among the urban poor, can be used to facilitate the launch of an effective city-wide adaptation strategy. The Turtles Conservation Group in Kigamboni in Dar es Salaam searches and protects sea Turtle nests. The group has developed a sense of ownership of the area and maintains surveillance to ensure that Turtle nesting areas are protected. The Mtoni Kijijini Conservation Group in Temeke, Dar es Salaam, checks the illegal harvesting of mangroves trees and is active in replanting more mangroves to restore the coastal ecosystem. In Mombasa, local Beach Management Units work collaboratively to ensure sustainable use of coastal resources in their areas of operation. All these collective group actions indicate the existence of social capital.

5. Building adaptive capacity through opportunities created by social capital

Literature is replete with examples where social capital has provided the exploratory power specific in the area of environmental management, especially where common property resources (water, forests, grazing areas, etc.) are concerned (Adger Citation2001, Citation2003, Grootaert Citation2001, Salick and Byg Citation2007). However contribution of social capital in providing critical material support for environmental management elsewhere cannot be generalized to include East Africa. Instead, successful implementation of adaptation options using social capital in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam will require an understanding of the groups, association and/or networks involved, i.e. the location and activities of those groups or units that serve as loci for mutually beneficial activities. From the start, the most important attributes of these groups, association and networks should be their functional capacity to collectively identify problems, take decision and act by allocating resources.

It is of course possible to achieve coordinated actions among groups of people possessing no social capital. The problem with this is that it almost always entails offering incentives,Footnote9 additional transaction costs in monitoring and regulation, as well as in enforcing formal agreements. Incentives, regulations and enforcements may change the behavior of group members but fail to change their attitude. Community groups normally revert back to old ways when incentives are not forthcoming or regulations enforced (see Fukuyama Citation2001, Pelling and High Citation2005a). Besides, the low-income countries of Eastern Africa lack financial resources to offer incentives and have weak urban governance structures incapable of undertaking effective monitoring and regulation.

In Mombasa and Dar es Salaam, the poor urban population lives in the riskiest parts of city. In Dar es Salaam, this category of the population accounts for about 70–75% of the city's total population (United Republic of Tanzania Citation2004, Dodman et al. Citation2009b) whereas in Mombasa, the number of poor people is known to have increased by 38.82% between 1994 and 1997 (Republic of Kenya Citation2002). One of the most important lessons learnt from the devastation of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was that even where risks have been reduced through decades of investment in housing, infrastructural design, flood defences and well-resourced emergency services, these can still be overwhelmed by the forces of disruption, with the poor households being the most affectedFootnote10 (see Huq et al. Citation2007, Dodman et al. Citation2009a). Engaging resource-oriented marginalized groups is a fundamental form of encouraging the participation of the poor and enablement of community education about the value of adaptation, as well as providing an empowerment and compelling mechanism for transmission of ideas and claims from the bottom-up (Allen Citation2006).

The adaptation measures initiated by low-income cities like Mombasa and Dar es Salaam should be underpinned on the premise that both the local groups and the city-level policy-makers have the motivation, but generally lack the capacity to implement more ambitious adaptations strategies to address uncertain climate change. Even so, this has to begin with the planners/authorities accepting the central role of local groups and networks in the process of city development and economic growth first (Revi Citation2008). The potential for social capital to deliver material interventions for adaptation lies not in the number of associations involved but in their ability to create and maintain linkages that would enable them to achieve resources and access to power necessary to shift the rules of the game in their favor. Synergistic interactions with governing institutions cause them to evolve in a process often characterized as policy learning. These can then build trust and legitimacy and help promote long-term decisions on adaptation even when there are urgent and divisive conflicts over short-term interests (Narayan Citation1999). For example, assisted by a local Non-Governmental Organization, the Majaoni Youth Group in Mombasa has teamed up with the departments of Fisheries and Forests to rehabilitate and protect mangrove forests in the areas, as the group practices silvoculture. The group has helped to stop loggers from further destroying the mangroves by keeping vigil as well as eliminating illegal farming activities that previously took place close to the highest water mark.

Examples of such activities in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam that are undertaken without regard to adaptation but have great potential to contribute to adaptation include regeneration and protection of mangrove forests along the coastlines, seaweed farming, beach protection/embankment, garbage collection, etc. Giving an example of the importance of mangrove forests in building adaptive capacity, Kliver (Citation2008) explains how researchers from the World Conservation Union (IUCN) compared the death toll from two villages that were hit by the giant tsunami wave in December 2004. Whereas two people died in the settlements with dense mangrove and scrub forests, up to 6000 people lost their lives in a nearby village without similar vegetation. The mangrove forests served as bio-shields for the coastal settlements and reduced their exposure to the effects of the wave. Similar messages were reported in the 2008 Burma catastrophe where the removal of mangroves ecosystem played a part in increasing vulnerability of communities to storm surge and floods (Kliver Citation2008).

In addition to achieving adaptation through city-wide environmental management initiatives, social capital's relationships of trust, reciprocity and connectedness can be drawn upon in responding to non-climate-related stressors. For example, Weru (Citation2004) explains how exchange visits between group-saving schemes in Nairobi slums helped in coping with a fire disaster. When fire burned down one of the informal settlements, it was the savings scheme members who first responded, bringing money and food. Resource groups and their networks can act also as a political force to mobilize for policy changes at the city level and higher levels of government. As consumers of material goods and resources found in the coastal cities, e.g. fish, urban agricultural products and mangroves/their products, they can collectively enact behavioral changes that are consistent with the needed adaptation measures (see Moser Citation2006). Further, the groups' strong local opinion can secure conservation gains by resisting inappropriate development. For example, in Mombasa one of the Beach management groups successfully prevented a wealthy private developer from erecting a wall that would have blocked access to a public beach.

There are indeed compelling reasons to believe that, if the centrality of local resource-oriented groups is accepted in the city development processes, these will be able to provide the necessary policy and knowledge continuity.Footnote11 Provided that there is strong social capital within the groups, it obviates the problem of opportunists out to make use of the policy gaps and ineffective regulatory mechanisms to undermine adaptation efforts. This way, the social capital resource can be mobilized to resist unsustainable vulnerability increasing forms of development or livelihood practices and to raise local concerns more effectively with political representatives.

6. Conclusion

In this article, the discussion of social capital in the context of climate change has shown that both the city authorities and the national governments in East Africa have a key role to play in planned adaptation to climate change. However, they lack the necessary capacity to do so and are not in a position to provide adequate resources and infrastructure for adaptation. For this reason, they should seek to implement adaptation in partnership with local resource-oriented groups, thus utilizing the social capital resource found within them. These local capacities can provide a foundation for effective climate change adaptation. In effect, this will not only ensure acceptability and effectiveness but also build the much needed adaptive capacity at the range of urban scales. Furthermore, to operate at an appropriate scale, these groups/associations have to become part of wider networks. This will provide a stronger source of support and ensure a meaningful engagement with the state institutions in a synergistic mutually supportive state–community relationship.

The Mombasa and Dar es Salaam case study has also shown that the use of social capital resource in climate change adaptation will succeed if viewed as an element in the wider processes of sustainable development and not as stand-alone local projects concentrating on climate change. This means embracing local development initiatives that are taken without reference to climate change but that can help minimize climate risks while enhancing economic and political development. It further means choosing adaptation options in the context of poverty-driven economic survival urbanization, as is currently the case for the two East Africa coastal cities. This vulnerability reduction approach also helps in addressing present day climate events (including climate variability), therefore making it easily communicable to relevant stakeholders.

New and existing policies should also be aimed at linking climate conditions with urban development, housing, land use management and information dissemination with deliberate efforts being directed at developing important information communication tools such as hazard maps, vulnerability assessment tools and early warning systems. Using these tools in the context of social capital would greatly contribute towards the improvement of adaptive capacity of the coastal urban communities and facilitate their adaptation to climate change. Indeed, the need to identify ways and means by which to transcend social divide and build both horizontal and vertical social cohesion and trust in addressing the effects of uncertain changes in climate cannot be overemphasized.

The findings of this study add to the existing knowledge on the significance of social capital in facilitating the effective application of a range of public policies in communities and places. As many contributors have shown that social capital embedded in local associations makes significant contributions to household welfare and poverty reduction, the study aimed at attaching new relevance to this hidden resource in helping to provide material interventions to build adaptive capacity in coastal East Africa cities.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Justus Kithiia

Justus Kithiia is completing his Ph.D at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. His higher degree research area of concentration is climate change risk responses in coastal urban areas in East Africa. He also possesses postgraduate qualifications in Disaster Management studies from the United Kingdom.

Notes

1. Involves the cultivation of marine organisms in ponds filled with seawater.

2. Integrated mangroves-shrimp/fish production.

3. The endangered marine turtles were Olive ridley turtle, Green turtle and Hawksbill turtle.

4. Under the UNFCCC agreement, all least developing countries should develop NAPAs.

5. Visions 2030 and 2025 are blue prints aimed at transforming the Kenyan and Tanzanian's economies to offer high quality life to their citizens.

6. Brown agenda issues include environmental health and local issues such as inadequate water and sanitation, urban air quality and solid waste disposal.

7. Gray agenda issues are associated with industrialization and urbanization, e.g. chemical pollution of air and water sheds.

8. For further understanding of environmental transition and agenda issues, the reader is referred to the works by Marcotullio et al. (Citation2005) and McGranahan et al. (Citation2007).

9. Some of the incentives given to voluntary groups in Africa include food, cash or tools for work.

10. Wealth generally allows individuals and households to reduce risks, e.g. by building safer houses, choosing safer jobs, insuring assets.

11. Unlike other forms of capital, social capital increases with use and decreases with disuse.

References

- Adger, N.W., 2000. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related?, Progress in human geography 24 (3) (2000), pp. 347–364.

- Adger, N.W., 2001. Social capital and climate change. School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia; 2001, Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research working paper no. 8.

- Adger, N.W., 2003. Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change, Economic geography 79 (4) (2003), pp. 387–404.

- Adger, W.N., 2006. Vulnerability, Global environmental change 16 (2006), pp. 268–281.

- Adger, N.W., et al., 2007. "Assessment of adaptation practices, options, constraints and capacity". In: Parry, M.L., et al., eds. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 717–713, Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change.

- Allen, K., 2006. Community-based disaster preparedness and climate adaptation: local capacity building in the Philippines, Disaster Journal 30 (1) (2006), pp. 81–101.

- Awour, C.B., Orindi, V.O., and Adwera, A.O., 2008. Climate change and coastal cities: the case of Mombasa, Kenya, Environment and urbanization 20 (1) (2008), pp. 231–242.

- Bhattarai, M, and Haming, M., 2001. Institution and the environmental Kurnets curve for deforestation: a cross country analysis for Latin America, Africa Asia, World Development 29 (2001), pp. 995–1010.

- Coleman, J., 1990. Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1990.

- Dodman, D., Ayers, J., and Huq, S., 2009a. "Building resilience in 2009". In: State of the world: into a warming world. Washington, DC: The Worldwatch Institute; 2009a, Ch. 5.

- http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2011 Last accessed 20Sep2009. , Dodman, D., Kibona, E., and Kiluma, L., 2009b. Tomorrow is too late: responding to social and climate vulnerability in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Case study prepared for cities and climate change: global reports on human settlements 2011..

- Dossou, K.M.R., and Dossou, B.G., 2007. The vulnerability of climate change of Cotonou (Benin): the rise in sea level, Environment and urbanization 19 (2007), p. 65.

- Maziwa Island off Pangani (Tanzania): history of its destruction and possible causes. Patent number Regional sea reports and studies no. 139, UNEP, 88. 1992.

- Ford, J., 2008. Emerging trends in climate change policy: the role of adaptation, International public policy review 3 (2008), pp. 5–15.

- Fukuyama, F., 2001. Social capital, civic society and development, Third world quarterly 22 (1) (2001), pp. 7–20.

- Gibbs, M.T., 2009. Resilience: what is it and what does it mean for marine policymakers, Marine policy 33 (2009), pp. 322–331.

- Godschalk, D., et al., 1998. Coastal hazard mitigation: public notification, expenditure, limitation and hazard areas acquisition. Capital Hill, NC: Centre for Urban and Regional studies; 1998.

- Grootaert, C., 2001. "Social capital: the missing link?". In: Dekker, P., and Uslaner, M., eds. Social capital and participation in everyday life. London: Routledge; 2001. p. 19.

- Hulme, M., et al., 2001. African climate change: 1900–2100, Climate research 17 (2001), pp. 145–168.

- Huq, S., et al., 2007. Editorial: reducing risks to cities from disasters and climate change, Environment and urbanization 19 (1) (2007), pp. 3–15.

- Ibe, A.C., and Awoski, L.F., 1991. "Sea-level rise impact in African coastal zones". In: Omide, S.H., and Juma, C., eds. A change in the weather: African perspective on climate change. Nairobi, Kenya: ACTS; 1991. pp. 105–112.

- [IPCC] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, , 2001. Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

- 2005. Keiner, M., Koll-Schretzenmayr, M., and Schmid, W.A., eds. Managing urban future: sustainability and urban growth in developing countries. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Company; 2005.

- http://www.tourism.go.ke/ministry.nsf/doc/Facts%20&%20figures%202007.pdf/$file/Facts%20&%20figures%202007.pdf, [KNBS] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2007. Update on tourism statistics [online]..

- http://www.sudnet.org/mediapool/65/651506/data/CC_and_cities-Mombasa.doc Last accessed 27Jun2008. , Kenya Television Network News, May 2007. In: C.B Awour, V.A. Orindi, and A. Adwerah, Climate change and coastal cities: the case of Mombasa, Kenya.

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7385315.stm Last accessed 24Jun2008. , Kliver, M., 2008. Mangrove loss ‘Put Burma at risk’ [online]. BBC news..

- 2005. Lim, B., ed. Adaptation policy and frameworks for climate change: developing strategies, policies and measures. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

- MacClanahan, T.R., 2007. Achieving sustainability in East Africa coral reefs, Journal of the marine science and the environment C5 (2007), pp. 1–4.

- Mahongo, S., 2006. Impacts of sea level change. Presented at A paper presented at the ODIAAFRICA/GLOSS training workshop on sea-level measurement and interpretation. Oostende, Belgium, .

- Marcotullio, P.J., Rothenberg, S., and Nakahara, M., 2005. "Globalisation and urban environmental transitions". In: Richardson, H.W., and Bae, C.-H.C., eds. Globalization and urban development: advances in spatial science. Berlin: Springer; 2005.

- McGranahan, G., Balk, D., and Anderson, B., 2007. The rising tide: assessment of the risk of climate change and human settlements in low elevation coastal zones, Environment and urbanization 19 (2007), p. 17.

- Mertz, O., et al., 2009. Adaptation to climate change in developing countries. Special feature, Environmental management 43 (2009), pp. 743–752.

- Mohan, G., and Mohan, J., 2002. Placing social capital, Progress in human geography 26 (2) (2002), pp. 191–210.

- Moser, S.C., 2006. Talk of the city: engaging urbanites on climate change, Environmental research letters 1 (2006), p. 10.

- http://www.safarilands.org/docs/ministry_tourism_tz_budget_09-10.pdf Last accessed 02Aug2009. , Mwangunga, S., 2009. Hotuba ya waziri wa Maliasili na Utalii wakati akiwasilisha bungeni makadirio ya matumizi ya fedha Mwaka, October 2009 [online].

- Narayan, D., 1999. Bonds and bridges: social capital and poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1999, World bank policy research working paper 2167.

- http://allafrica.com/stories/200806170166.html Last accessed 17Jun2008. , Nation News, June 2008. Man dies as heavy rain pounds coast [online]. Nationmedia..

- Status of coral reefs in Eastern Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa. Patent number Status of coral reefs of the World: 2002, Ch. 4. GCRM report. 2002, InC.R. Wilkinson, ed.Australian report of Marine science, Townsville63–78.

- 2007. "International panel on climate change 2007; climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability". In: Parry, M.L., et al., eds. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the international panel on climate change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 433–467.

- Patwardhan, A., 2006. Assessing vulnerability to climate change: the link between objectives and assessment, Current science 90 (3) (2006), pp. 376–383.

- Pelling, M., and High, C., 2005a. Understanding adaptation: what can social capital offer assessments of adaptive capacity, Global environmental change 15 (2005a), pp. 308–319.

- Pelling, M., and High, C., 2005b. Social learning and adaptation to climate change. (2005b), Benfield Hazard Research Centre, Disaster studies paper 11.

- 2003. Pittock, B., ed. Climate change: an Australian guide to the science and potential impacts. Canberra: Australian Greenhouse Office; 2003.

- Putnam, R.D., 1995. Turning in, turning out: the strange disappearance of social capital in America, Political science and politics 28 (1995), pp. 667–683.

- Putnam, R.D., 2000. Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2000.

- Pretty, J., 2003. Social capital and connectedness: Issues and implications for Agriculture, rural development and natural resource management in ACP countries. (2003), Review paper for CTA. CTA working document Number 8032.

- Republic of Kenya, , 2002. Ministry of Planning and National Development Mombasa District Development Plan. Nairobi: The Government Printer; 2002.

- Revi, A., 2008. Climate change risks: a mitigation and adaptation agenda for Indian cities, Environment and urbanization 20 (1) (2008), pp. 207–230.

- Salick, J., and Byg, A., 2007. Indigenous people and climate change. Oxford: University of Oxford and Missouri Botanical Garden; 2007.

- Sallema, R.E., and Mtui, G.Y.S., 2008. Review. Adaptation technologies and legal instruments to address climate change impacts to coastal and marine resources in Tanzania, African journal of science and technology 2 (9) (2008), pp. 239–248.

- Sarewitz, D., Pielke, R., and Keykhah, M., 2003. Vulnerability and risks: some thoughts from political and policy perspectives, Risk analysis 23 (4) (2003), pp. 805–810.

- Scott, M., et al., 2001. "Human settlements: energy and industry". In: Climate change impacts 2001. Impacts adaptation and vulnerability. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 381–416, Ch. 7. Contribution of working Group II to the third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change.

- Siambalala, B.M., 2006. The concept of resilience revisited, Disasters 3 (2006), pp. 433–450.

- Smit, B., and Wandel, J., 2006. Adaptation, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability, Global environmental change 16 (2006), pp. 282–292.

- Thomalla, F., et al., 2006. Reducing hazard vulnerability: towards a common approach between disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation, Disasters 30 (1) (2006), pp. 39–48.

- Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, , 2006. Research strategy 2006–2009. Norwich, UK: University of East Anglia; 2006.

- UNEP/DGIC/URT/UDSM, , 2002. Eastern Africa atlas of coastal resources. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Programme; 2002. p. 111, ISBN 92 807 20619.

- [UN Habitat] United Nations Human Settlements Programme, , 2008. The state of African cities. Nairobi: UN Habitat; 2008.

- [UN ICCPR] United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, , 1966. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (1966), The United Nations.

- United Republic of Tanzania, , 2004. Dar es Salaam city profile. Kobe, Japan: WHO centre for development; 2004, A document prepared by Dar es salaam City Council with advice from Cities for Health programme.

- [VPO] Vice President's Office Report, , 2003. Initial national communication under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2003), p. 141.

- Weru, J., 2004. Community federations and city upgrading: the work of Pamoja Trust and Muungano in Kenya, Environment and urbanization 16 (1) (2004), pp. 47–62.