Abstract

The objective of the Algerian government was to build two million housing units by 2014 to overcome housing shortage. But little consideration has been given to achieve sustainable design and construction within new buildings, where flexibility and variety are necessary to allow residents to make changes and adaptations to their homes. This article reports on a study of two government-provided housing settlements in Constantine, Algeria. Eighty dwellings from social collective housing were analysed to evaluate their sustainability by examining two indicators: satisfaction with spatial organisation and level of flexibility in design. It was shown that many modifications were made, both small and large, to attempt to accommodate changing needs, size of families, and to satisfy new lifestyle aspirations. However, where alterations were made, the consequences were potentially hazardous to buildings and led to rapid degradation. It was suggested that to achieve buildings with longer useful life, future designs should build in more flexibility and better space standards.

1. Introduction

Achieving sustainability for urban development and the built environment is very difficult to do, particularly in Algeria. For many years, the concentration of effort in Algeria has been to address the crisis of an acute housing shortage. Policies and debates have been more about quantity than quality of dwellings. The attempt to address the crisis has been done by producing large numbers of standard stereotypical housing units with designs that are far from meeting user’s changing needs.

As a result, most of these new buildings are subject to alterations made by inhabitants, either before or after moving in, to meet their social and technical needs and give them an appropriate life style. These alterations have led to a rapid deterioration and degradation of buildings and their structure, and have exposed the housing to the risk of collapse that could be brought about by different natural disasters. But the authorities continue to provide these stereotypical dwellings in large quantities, without thought for their durability and the sustainability of the built environment. No attempt has been made to search for better housing design and construction systems, which might help to keep traditional culture, while using new technologies.

During the last 50 years, the Algerian government has made an enormous effort to overcome the housing crisis through large-scale housing construction, in particular by providing collective dwelling units. The rate of these buildings doubled from 1966 to 1998, rising from 7.8% to 16.7%, and many more have been programmed since (Organisme Nationale des Statistiques Citation2008). The approach of the government to housing construction during these last periods focused particularly on social dwellings (residential housing buildings) and supported low-income families to gain access to property. This strategy brought about the delivery of more than one million dwellings during the last 5 years (2005–2009). Moreover, the delivery of another million units is projected up to 2014 (Ministère de L’Habitat et de L’Urbanisme Citation2009). But the new objectives of policy for housing were no different from the preceding, because they concentrated on quantitative and economic aspects. The new housing programs and designs are no different from the former in either spatial design or size, despite changing lifestyles and requirements for housing. Moreover, demographic, socio-cultural, economic, and other changes mean that these dwelling types no longer meet the requirements of users (Hamidou Citation1989).

Some researchers on housing construction and social aspects have highlighted the “discordance” between multi-storey dwellings as a planned built framework and inhabitants’ requirements (Lezzar Citation2000; Benrachi Citation2004; Tebbib Citation2008). Results of their researches showed that this kind of dwelling and its size and layout of spaces did not respond to family sizes and the way they lived, nor were the technical services and building systems flexible or adaptable enough for modern living. However, findings of these studies had no impact on the Algerian government’s decision-making and did not lead to readjustment of programming and design methods for the future housing programs. Thus, these stereotypical apartments continue to be regarded as a single solution to overcome the housing crisis and as a single means to provide shelter for the people. As a result, because inhabitants of these dwellings cannot afford to buy larger homes and have to live with the negative effects of space constraints, they make changes to adjust them to their requirements without expert advice and help. Consequently, these alterations do not conform to building regulations and result in serious technical and aesthetic problems. And of course these actions do not help to achieve the sustainability of the buildings.

1.1. Housing flexibility and sustainability

It is clear that while the Algerian government has provided housing in large quantities, the result is a widespread housing provision that is not necessarily fit for purpose, nor is it sustainable in the long term. Of course, sustainability can be very broadly defined, from the Brundtland definition (Gallent et al. Citation2010) of balancing environmental, social, and economic factors together, through many means of reducing carbon and energy use (Drury et al. Citation2006) to the sustainability of communities and lifestyles (Drury Citation2009). While recognising this, this article here uses the term to refer to one specific aspect of sustainability and that is to extend the useful life of buildings, and housing in particular, and argues that flexibility may be one way to achieve it.

In contrast to designing an individual house, the design of housing comprising multiple dwelling units cannot be so clearly defined. Designers rarely know or understand future users’ preferences, and this lack of knowledge is particularly common amongst designers in Algeria. Yet, it should be noted that many studies carried out in other countries have suggested that including flexibility principles in building design, and particularly in multi-storey housing buildings, can provide many options for changes over the lifetime of a building without altering the quality of the construction.

Lans and Hofland argued that, in the context of housing, consumers’ behaviour is changing and consequently so are requirements for dwellings. Because household requirements change over time, and different types of households have different requirements, housing must be flexible in its design and adaptable to user’s behavioural changes (Ozsoy & Gokmen Citation2005). For that, different levels of design flexibility within a building’s lifetime can define the extent of adaptability, taking into account the difference between space flexibility and technological flexibility (Lans & Hofland Citation2005). According to Edwards and Jovanovic, flexibility could be considerable if it is within a room in an apartment (room furniture), but at the level of apartment (floor plan), the structure should have the capacity to allow for different layouts, although it is much less flexible (Edwards Citation2000; Jovanovic Citation2007).

Flexibility needs also to be considered when aiming for sustainability as buildings may have a lifetime of up to 200 years or more. The structure and façades may need to last for a long time and be difficult to alter to meet changing requirements. In this case, Lans and Hofland stated that requirements are related to about 13 types of flexibility used to measure the extent of building design, including furnishing, floor plan changes, wheelchair adaptability, finance, identity, modernization, expansion, shrinkage (Lans & Hofland Citation2005).

However, to meet present and future users’ requirements, flexibility makes high demands on building plans and forms, and consequently, the investment could be considerable. Nevertheless, in the long term, it is worthwhile to think about sustainable buildings through the use of flexibility. It should be noted that, if the principles of flexibility were considered in earlier Algerian housing design, the buildings might have better satisfied users’ housing aspirations and helped to minimize unsuitable alterations and diminish the rapid degradation of their housing.

This article reports the results of a survey into sustainability in building, which evaluates housing by examining two indicators: residents’ satisfaction with the spatial organisation of their apartments and level of flexibility the buildings offer. Two examples of social collective housing settlements in Constantine city were analysed to point out levels of satisfaction, the extent to which these dwellings are flexible, the changes users have made and how these affected their traditional living, and the impact of changes on the building structure.

2. A case study of Algerian social collective housing

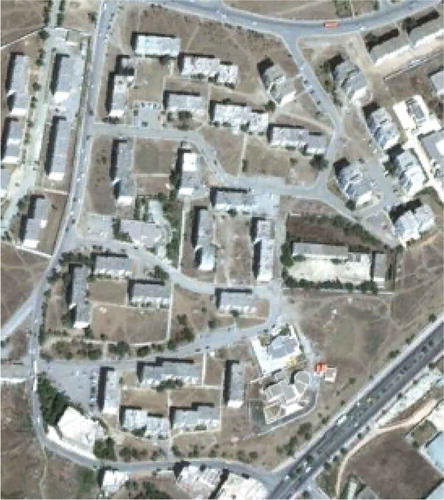

The findings of this study are based on the results of research carried out in two social collective housing settlements in Constantine, where transformations were made by inhabitants to respond to their social needs. The investigation was based on the analysis of data collected from interviews with users and observations of space used to determine changes made in the dwellings. The areas studied are the most important government-built housing developments in Constantine (20 Août 55 & Boussouf). The first district was built in the 1970s with a precast concrete structural system and the second one in the 1980s with a tunnel formwork structural system ( and ).

The methodology in the field involved interviews with residents, observations and survey drawings of the changes and alterations people had made to their dwellings. The plan layouts and the space utilization of the dwellings and the social status of the users were examined to make a comprehensive evaluation about residents’ lifestyles. Based on the techniques used, the relationship between the use of space and satisfaction with layouts were evaluated and the level of flexibility of dwelling plans and rooms investigated. Eighty dwelling units from these two settings were examined in detail by analysis of interviews, drawings, and photographs.

2.1. Family characteristics

These dwelling units were originally allocated to families of state employees of the university and companies. Most of these people have subsequently moved and sold their apartments to other families, usually of a larger size. So the majority (60%) of families occupying the dwellings in 20 Août 55 has three or four persons and the majority (60%) in Boussouf has five, six, or even more persons living in the dwellings. The profile of the respondents is 70% women who are housewives and 30% state employees. Of the men, 50% are state employees, 30% are employed in low-income jobs, and the remaining 20% are retired.

2.2. Plan types

The two main plan types examined in the two different settlements have a similar block size and form. They are rectangular in shape, and the dwelling units examined are of a standard total area of around 65 m2. All of the plan types have two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, and a bathroom with a separate WC. As can be seen from and , the general layout and spatial organisation of the plan types are similar.

2.3. Transformations and flexibility

Changes and alterations made by families have been examined and grouped according to the plan types.

The plan types examined showed that there were two kinds of transformation made by the families to satisfy family needs. The first were light works and made to improve space use, security of the dwellings, for maintenance and repair, and to enhance the aesthetic quality; these alterations were made by all families. The second were substantial and weighty alterations for the internal extension of spaces by removing of load-bearing walls. They were made by 90% of families. These latter changes are shown for each plan type in and described further.

2.3.1. First plan type (20 Août 55)

60% of families had expanded their kitchen and living room spaces by addition of a loggia space. This involved removing load-bearing walls ().

25% had converted their kitchen space by addition of an entrance hall and storage spaces into a living room and changing drying and loggia spaces into a kitchen by removing part of load-bearing wall ().

5% had converted the kitchen space into a bedroom and had converted their loggia and drier spaces into a kitchen by removing part of load-bearing wall ().

2.3.2. Second plan type (Boussouf)

30% of dwellings had the kitchen space extended by addition of a bathroom space, with conversion of the drying space into a bathroom, with consequent reduction of toilet space. Also part of load-bearing wall had been removed ().

60% made significant changes by adding a loggia space, enlarging bedroom spaces, changing the kitchen space into a bedroom, changing bathroom and drier space into partly a kitchen and partly a bathroom with integrated toilets. Load-bearing and façade walls have been partially removed ( and ).

The circles/ovals in show walls or parts of walls that have been removed and those considered as dangerous are shown in dark black. Because these are part of the structure, they are crucial to support the building and live loads of occupants, and if they are removed, particularly in the lower levels as the case in our studied examples, they create cracks in floors, compromise the structure, and put the building at risk of collapse in case of earthquakes.

2.4. Space use

The research showed variations in the use of space and activity patterns occurring in the case study dwellings, and the changes recorded on the plans and presented in are as follows:

10% of families of 3 or 4 persons with children of the same gender are generally satisfied with the number of rooms. Spaces are used normally. The living room, which is the family room, is used for sitting, dining, watching TV, and hosting guests. The parents’ bedroom is used for sleeping and watching TV at night. The children’s bedroom is used for sleeping and studying.

90% of families with more than 4 persons with children of similar or different gender are not satisfied with the dwelling size. Spaces are used for multiple functions.

Table 1. Variations in the use of space and activity patterns

The living room is used for sitting, dining, watching TV, hosting guests, and sleeping. The parents’ bedroom is used for sleeping, watching TV, and sitting. Children’s bedrooms are used for sleeping, studying, sitting, watching TV, and hosting guests. In this case, living room and children’s bedrooms are used for other tasks than those intended. Larger kitchens are needed to house a lot more housework such as cooking, eating, and making traditional food (couscous) and bread.

In some dwellings, a hall space is added to the kitchen to be used as a living room to free living space room for children. Loggias’ have their facades closed in and are used as a kitchen to free the former kitchen space for other functions, such as living space.

2.5. Resident satisfaction

When asked whether they were satisfied with the spatial organisation of their dwelling, 10% of the interviewees – families of three or four people – responded positively about their dwellings, while 90% – families of more than four persons – were not satisfied. The reasons for the dissatisfaction were an insufficient number of rooms (30% in 20 Août 55 and 60% in Boussouf) and the size of the dwelling (i.e. the number and size of rooms – 60% in 20 Août 55 and 30% in Boussouf) (). When they were asked what they thought about the quality of their dwelling and what they would need to have, most of them emphasized the need for a sufficient number of rooms, while the rest indicated the need for a larger dwelling size.

The most used spaces by the family members, and which have been modified in size, are kitchen and living room. The kitchen is used for a lot of traditional functions like preparing home bread and couscous, celebrating religious feasts for the family, like mutton feasts and others, which needed a large size for this space. Also, large living rooms and bedrooms can host a lot of people (at night) during religious feasts, weddings, and even funerals, which constitute traditional values that are being eroded by the time and actual conditions of life.

For both samples, their rooms (living room, bedrooms, kitchen, and bathroom) look to be very flexible, because their furniture can be easily moved and the shape of the rooms does not hinder this. But, because of the rigidity of the construction system, there is virtually no flexibility of their floor plan. Changes to façades and internal walls, which are part of the structure, are very difficult and even dangerous to adjust or remove.

However, these works had been carried out without expert’s advice or help, and according to building engineers, they endangered the stability of the building structure.

3. Discussion

Our study on space appropriation for plan types of social collective housing by inhabitants showed that the socio-cultural dimension of users in terms of space is one of the more determining elements for housing programming and design.

That is, the users did not lose all their traditional values, and the values conveyed by imported housing model are not all assimilated by the users. Indeed, and in reality, interior spaces initially intended for precise functions are invested by other functions and meanings. At the same time, the forms are found to be subverted and transformed. Spaces whose purposes have been transformed, mostly in size, are kitchens, bathrooms, and bedrooms. Larger bedrooms and living rooms will accommodate many more tasks, such as sleeping, relaxing, studying, eating, and so on. In addition, sleeping spaces are separated by gender (boys and girls) and by family members (children and parents). In some cases, and depending on the household size, a separate living room is mainly for visitors. In this case, family privacy and intimacy are preserved. As a result, the remaining space is reduced and some kitchen tasks flow over into bedroom spaces, like food preparation, which accords with Algerian traditions.

Internal dwelling spaces are the most transformed, because they have undergone not only light changes but also weighty ones, often with the removal of load-bearing walls. These changes allowed either the addition of one bedroom or the extension of various spaces to accommodate larger family sizes or with children of different gender. Where they altered the building structure (demolition of load-bearing walls and/or facades), they completely modified the aspect of the building elevations and created uncontrolled cracking in building joints ( and ). The structural changes made by residents put all the occupants at risk and could result in loss of life if the buildings collapsed in an earthquake. But further, such unsafe modifications could mean that even if the buildings did not collapse, they might prove dangerous enough to need to be demolished. This would be costly, unsustainable, and necessitate replacement homes being built.

Given the building types and their structure, the level of flexibility is very low. Changes within the dwelling made by users were generally just space extension in bedrooms and modernization of kitchens and bathrooms to satisfy lifestyle changes. It should be noted that dwelling unit type, size, the positioning of technical services, and building structure – factors that most affect the dwelling flexibility – were not investigated.

4. Conclusion

The findings show that most social dwellings in multi-storey buildings are designed and built in a way that does not respond to present and future users’ needs. If they are subjected to many weighty changes over their lifetime, they will be unsustainable in future and cannot be integrated within a sustainable built environment. Yet, it is the meaningful touches of the individual users in their homes that increase their satisfaction and show their tendencies and preferences. If these are understood and accommodated, then this should throw some light on the future design for mass housing.

The study has shown that both the form of construction and types and sizes of dwellings provided through the Algerian mass housing provision is rigid and inappropriate to lifestyles and changing needs. This form of mass housing does not work well in Algeria, and it is doubtful if it would work elsewhere in the region or beyond. It needs to change.

Therefore, it was suggested that introducing flexibility in housing design and increasing the space and number of rooms are the main elements needed to meet present and future social demand and for achieving more sustainable housing for Algeria in the long term. This would have the added benefit of removing the need for residents to make alterations and ensure that dangerous structural changes are discouraged

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bouba Benrachi

Bouba Benrachi: Born on 28 May 1961 at Constantine, Algeria, D. Arch, M.Phil, Ph.D, is a full-time graduate and postgraduate associate professor at the Department of Architecture and Planning, Constantine Mentouri University. She is a principal investigator of four research succeeding projects and is author of many research papers and has refereed national and international conferences. Her subjects of interest include architectural and housing design, building technologies and regulations, and cities and urban risks.

Samir Lezzar

Samir Lezzar: Born on 8 December 1953 at Mila, Algeria, D.Arch, M.Phil, worked as an architect in a national building company from 1978 to 1988. He is a full-time graduate lecturer, preparing a Ph.D at the Department of Architecture and Planning, Constantine Mentouri University. He is a member of four research succeeding projects and is author of many research papers and has refereed national and international conferences. His subjects of interest include architectural and housing design, building technologies and regulations, and building restoration.

References

- Benrachi B. 2004. Evaluation de le Relation entre les Exigences Techniques et le Coût de Construction des Logements Collectifs: Cas de Constantine [Thèse de Doctorat d’Etat]. Constantine: Université Mentouri de Constantine.

- Drury A, Welch G, Allen N. 2009. Resident satisfaction with space in the home. A report for CABE by HATC Ltd & Ipsos MORI. 27 July. [Internet] London: Greater London Authority. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118095356/http:/www.cabe.org.uk/files/space-in-new-homes-residents.pdf

- Drury A, Watson J, Broomfield R. 2006. Housing space standard. A report by HATC Ltd. London: Greater London Authority.

- Edwards B. 2000. Sustainable housing: architecture, society and professionalism. In: Edwards B, Turrent D, editors. Sustainable housing: principles and practice. London: E & FN Spon; p. 12–35.

- Gallent N, Madeddu M, Mace A. 2010. Internal housing space standards in Italy and England. Progress in Planning. 74:1–52.

- Hamidou R. 1989. Le Logement: Un Défi. Co-Edition: ENAP-OPU-ENAL. Alger.

- Jovanovic G. 2007. Flexible organisation of floor composition and flexible organization of dwelling space as a response to contemporary market demands. Facta Universitatis – Series: Architecture and Civil Engineering [Internet]; 5, p. 33–47. Available from: http://journaldatabase.org/articles/flexible_organization_floor.html. ISSN 0354–4605.

- Lans W, Hofland CM, Jr. 2005. Flexibility, how to accommodate unknown future housing requirements. XXXIII IAHS World Congress on Housing: Transforming housing environments through design [Internet]; University of Pretoria, South Africa. September 27–30. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/2263/10355

- Lezzar S. 2000. Le Vieillissement Prématuré du Patrimoine d’Habitation : Construction, Entretien et Législation [Thèse de Magister]. Constantine: Université Mentouri de Constantine.

- Ministère de L’Habitat et de L’Urbanisme. 2009. Programme quinquennal 2010–2014 [Internet]; Edition, MHU. Alger. Available from: http://www.mhu.gov.dz/pdf/pq.pdf

- Organisme Nationale des Statistiques. 2008. 5ème Recensement général de la population et de l’habitat : les résultats préliminaires. Données Statistiques, 496, Editions ONS, Alger.

- Ozsoy A, Gokmen GP. 2005. Space use, dwelling layout and housing quality: an example of low cost housing in Istanbul. In Garcia-Mira R, Uzzell DL, Eulogio Real J, Romay J, editors. Housing, space and quality of life. England: Ashgate; p. 17–27.

- Tebbib EH. 2008. L’Habiter dans le Logement Social à Constantine: Manières et Stratégie d’Appropriation de l’Espace [Thèse de Doctorat En Science]. Constantine: Université Mentouri de Constantine.