Abstract

This paper intends to investigate the process through which the Tehran–Karaj urban region has come into being, tracing its development from a small-town status 200 years ago, to its current status as an urban agglomeration of about 13 million inhabitants. Having introduced the genesis and structure of this urban region, a short review of the main challenges raised by it will reveal the nature and character of interconnectivity between its different components. It will then be argued that unlike some leading examples such as the Randstad, this interconnectivity has never been taken seriously by policy-makers, and suffers from an inefficient sectoral governance system, although it calls for the introduction of an integrated management system in the region. Finally, it will be concluded that despite the urgency of establishing an Integrated Management and Monitoring Administration, there is a growing will to fragmentation which neglects any regional planning strategy.

1. Introduction

The urban region with a polycentric character reflects the very nature of the urbanization process in twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and is a response to the dynamics of urban territories characterized by a diverse spatial configuration, a decentralized economy, growing mobility and administrative complexity. Although this kind of large-scale urban accretion was first recognized and scientifically investigated in Western and European contexts, it rapidly became acknowledged as a universal phenomenon. Drastic changes to the urban pattern of some expanding non-Western cities, particularly in Latin America, the Middle East and Southern Asia, led to the emergence of diverse typologies of urban regions that were, in many aspects, different from those of Europe and North America. This new urban phenomenon generated new challenges to be confronted in different fields such as transportation, pollution, informal settlements, distribution of urban services and social segregation. Conventional and traditional forms of governance, including central municipal government, federal district authorities and township administration appear inadequate to address these emerging urban challenges (Laquian Citation1995), taking into account the socio-cultural and political background and other particularities of non-Western countries. Therefore, innovative governance and management systems have to be developed to meet the dynamics of the urban regions, address their multiple aspects and overcome their spatial fragmentation. However, proper governance systems for non-Western countries cannot be theorized and developed without regard to the Western or internationally recognized existing models and experiences; it underlines the importance of comparative studies and observations that any kind of place-specific system could emerge from a simultaneous reading and understanding of international knowledge and local potentiality.

This article takes the Tehran–Karaj urban region as a case study to show the connected problems of establishing and managing urban agglomerations in a Middle Eastern country, focusing on the crucial challenges of urban management. In this regard, the emergence and evolution of the concept of “urban region” in the scholastic sphere will be discussed, with a focus on the case of the Randstad, as a leading example of a place where different initiatives have been implemented towards developing a more efficient urban region. Following this, the genesis and foundation of the Tehran–Karaj urban region will be studied to show how a small town, which in the mid nineteenth century had a population of around 150,000, by the end of the twentieth century, had undergone transformation into an urban agglomeration of more than 13 million inhabitants. Subsequently, the structure of this urban region and its urban components is explained, followed by a discussion of its current problems with regard to urban management, which underlie the region’s essential inefficiency. This is followed by a discussion to show how this urban region has moved towards institutional and physical fragmentation, in the course of which, some exceptional plans which favoured greater integrity have been ignored. In conclusion, it will be argued that to tackle the region’s existing problems, it will be crucial to establish an integrated management and monitoring system.

2. Urban regions: background

In 1961, Gottmann argued that the urban agglomeration of the north-eastern seaboard of the United States is a new phenomenon, and calls for a new terminology. He used the term “megalopolis”, from an old Greek dream of building the largest city in the country, stating that this old dream appears to have been realized some thousands of years later in north-east America, an urban region in which city, suburb and countryside are structurally interwoven. He wrote: “It is hard to say whether they are suburbs, or ‘satellites’ of Philadelphia or New York, New Brunswick, or Trenton. The latter three cities themselves have been reduced to the role of suburbs of New York City in many respects, although Trenton belongs also to the orbit of Philadelphia” (Gottmann Citation1961, p. 5–6). For Gottmann, this megalopolis provides a new way of life; it is a “New Order of the Ages”, which proposes a “prototype” for every large-scale urban accretion where an extensive process of further urbanization is underway.

In fact, the urban region with a polycentric spatial pattern, as distinct from the monocentric urban system, is not an entirely new concept and can be traced back to the urban literature of the early twentieth century (Kloosterman & Musterd Citation2001; Hall & Pain Citation2006; Davoudi Citation2007). It addresses the dynamic nature of twenty-first century cities (Hall Citation2007), namely “decentralization of economic activities, increased mobility, complex cross-commuting and fragmented spatial distribution of activities” (Davoudi Citation2003, p. 994).

Although this phenomenon has been widely acknowledged by scholars, there is no terminological consensus, to the extent that a number of different expressions are in currency to explain this idea, such as the “post-industrial city” (Hall Citation1997), “polynucleated metropolitan regions” or the “polynucleated urban field” (Dieleman & Faludi Citation1998), “polycentric urban regions” (Kloosterman & Musterd Citation2001), “global city regions” (Scott Citation2002) and “mega-city regions” (Hall & Pain Citation2006). Moreover, there is no robust theoretical framework and definition for polycentric urban agglomeration; it may mean different things to different people, depending on their backgrounds and objectives (Kloosterman & Musterd Citation2001; Davoudi Citation2003).

Structurally, an urban region consists of a series of cities and towns, physically separated but functionally linked and networked by means of a well-organized transportation system, clustered around one or more large cities which are economically strong. This has been well reflected in the words of Hall and Pain (Citation2006), where they argue that the urban region with a polycentric pattern is “a new form” consisting of “a series of anything between 10 and 50 cities and towns, physically separate but functionally networked, clustered around one or more larger central cities, and drawing enormous economic strength from a new division of labour” (p. 3). Leading European examples of this kind are the Randstad in the Netherlands, the Flemish Diamond in Belgium and the Ruhrgebiet in Germany.

Although this phenomenon first appeared in the West, there is enough evidence to investigate a similar process of urban development taking place in non-Western countries all over the world, from Asia, and the Middle East, to Latin America. In fact, the traditional compact city with its mononuclear, dense, mixed-use pattern was unable to survive due to the rapid pace of urbanization over the last two centuries, and thus the establishment of new cores and centralities for meeting the daily needs of the inhabitants became a matter of urgency (Hall Citation1997; Champion Citation2001; Kloosterman & Musterd Citation2001). This issue is of particular note when the process of modernization and consequently the rapid urban growth of Middle Eastern cities is taken into consideration. In most of these cities, the new developments of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries followed western pre-modern and modern patterns and presented a less compact expansion, which contrasted with the existing city core, and consequently the low-rise, low-density pattern became overwhelmingly dominant (Bianca Citation2000). This led to an urban expansion that resulted in stark fragmentation in terms of wealth, the availability of urban facilities and social interaction, where the traditional core is no longer functional and new urban centres have not yet become properly established. This process has been accelerated by other factors such as rapid migration and intense urbanization, resulting in a plan-less suburbanization. Consequently, the surrounding small settlements and villages of the major cities are themselves transformed into new cities, mainly settled in an informal way, as in the cases of Cairo, Casablanca and Tehran. The outcome is an urban agglomeration with a multi-nuclear structure with considerable – although not necessarily efficient – economic, social and administrative interconnectivity.

However, a few crucial issues must be noted in this regard. While the phenomenon of the urban region in the Western context has been academically studied and adopted into urban development policy by policy-makers, its relevance, functionality and adaptability need to be investigated and examined in a non-Western context. As Davoudi (Citation2003, p. 996) states, a polycentric urban region in the western context “appears to be cropping up everywhere as an ‘ideal type’ and has been incorporated into planning policy objectives” (Faludi et al. Citation2002). This urban pattern has been included in the spatial policies of the European Union, such as the European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP) finally approved in Citation1999, and was further developed under the European Spatial Planning Observatory Network (ESPON), the Leipzig Charter and the Interreg IIIB programmes (Hall Citation2007). In these initiatives, polynuclearity was considered to be the essential prerequisite for the balance and sustainable development of local entities and regions (Sykora et al. Citation2009). However, in the context of developing countries, this phenomenon is, from the academic and policy-making points of view, very young and is predominantly viewed through the western literature and urban vocabulary which has been broadly developed and tested for the European–North American cases.

3. Urban regions and the question of governance: lessons from the Randstad experience

If an urban region consists of different components that are administratively independent but economically and structurally interconnected, how could integrated regional management be made feasible, and who would be responsible for its planning, implementation and monitoring? As Lefévre (1998) puts it, the governance of large urban areas came onto the agenda after the 1980s, because a new paradigm was needed to cope with the changing nature of urban areas influenced by the development of new information and communication technologies and globalization. Most national governments recognized the urgency of moving towards decentralized governing systems (Salet et al. Citation2003), since, as Laquian (Citation1995) argues, traditional modes of urban governance appeared essentially inadequate to address the multidimensionality of the problems and challenges which urban regions present. He writes that “Traditional forms of urban governance such as municipal government, township administration, federal district authorities, and so on have proved inadequate to govern and manage these very large regions” (p. 215). This is due to the wide expanse of territorial coverage, the multiplicity of local and national entities involved, the diversity of physical dimensions needed for development and the existing, sometimes conservative and solid tradition of governance rooted in the cultural and societal particularity of a given region. Therefore, a particular type of governance is needed to foster a correspondence between urban institutional systems and the characteristics of the urban regions within which they are situated. This governance model should possess a number of essential characteristics. It has to follow a process of defragmentation through which the disparate bodies of local government units are unified, merged or efficiently linked together. Additionally, this structure has to be powerful, autonomous, and legitimate, in the sense that it has to have sufficient authority in the affairs of the urban region, have the freedom to decide on territorial issues and be supported by a strong political legitimacy (Lefévre Citation1998). This awareness has generated a “renaissance of metropolitan governance” worldwide, whereby urban regions are looking for progressive modes of institutional modification that can create more efficient metropolitan authorities. Across Europe, regions have started to discover and develop their ability to enhance their governance capacities, for example, the Verband Region, Stuttgart and the Swedish experiments with regional parliaments (Lambregts et al. Citation2008). A short review of the case of the Randstad, Holland, as the best-renowned example of a working polycentric urban region, could be very informative here, since it shows how an urban region has programmed itself to move towards achieving a more cohesive spatial planning policy and a unified metropolitan authority.

Randstad Holland contains the western part of the Netherlands, including the major cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht, with plenty of small cities with a population of about seven million (almost 45% of the Dutch population) and about 50% of the country’s jobs and economic production, covering an area of roughly 80 × 80 km2. This urban agglomeration is “truly multi-nodal”, grown into one urban region by means of a well-established communication network (Dielman et al. Citation1999). However, there are no officially established boundaries. In the Randstad, the national government, the region’s four provinces and about 173 different municipalities are engaged in the governance of the region, with a dozen water management boards (Salet Citation2011). Public transport is provided by a mix of municipal, private and state transport companies and infrastructure providers. To achieve the goals of regional planning policy, an integrated efficient management system is undoubtedly urgent, a key prerequisite for which is “an effective strategic planning authority” at the regional level (Hall Citation1996).

In general, as Hendrik (Citation2006) puts it, all the urban regions in the world have complex governmental structures, and the Randstad is no exception, thus here, as elsewhere, an administrative crowdedness can be observed. In fact, “The Randstad is not and has never been an administrative unit nor has it been effectively governed by a regional or ‘Randstad’ authority” (Lambregts et al. Citation2008). However, the urgency of achieving a more integrated and efficient management and governance system at the regional scale has been widely affirmed and put onto the agenda since the 1990s. In this regard, new initiatives and programmes have been put on the agenda to enrich the “institutional integration” (governance) and “functional integration” of the entire region: while institutional integration intends to enhance governance capacity and reach a more cooperative unified body, functional integration tries to make the regional components structurally and physically integrated and well connected.

In 1998, the Deltametropolis Declaration was introduced, the aim of which was to develop a common vision for the region. This initiative resulted in the foundation of the Deltametropolis Association “to enhance the transformation of the ‘scattered’ Randstad into a more coherent ‘Deltametropolis’ through the initiation of research and design activities and by stimulating professional exchange between Randstad-based actors” (Lambregts et al. Citation2008, p. 50). A cooperative body called Regio Randstad was organized in 2002 to strengthen inter-province collaboration (Storm Citation2006). Despite a policy alteration in 2004 by which the Randstad was divided into four programme areas, in 2006 it was decided to establish a central Randstad authority or a single metropolitan government for which some institutional reforms were recommended.

In this regard, a decrease in the number of formal bodies as well as the creation of regional authorities has been put onto the agenda. Small municipalities have been merged together and the water management boards have been reorganized into four major water boards. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in its territorial review of 2007 proposed “merging the four provinces in the Randstad into one Randstad-province” to achieve a more functional regional government (OECD Citation2007). In Citation2007, the state decided to focus more on Randstad Holland as a whole, and, at the same time, to concentrate on priority investment projects. The idea of establishing a Randstad (Public) Transport Authority is again under study. The “Randstad Urgency Program” embraces 35 projects with high regional benefits, ranging from transport to urban development, and is governed by a cabinet minister accompanied by a regional politician, monitored by a supporting team including representatives from five ministries and the region. In the long term, “The Randstad 2040” vision project provides an umbrella under which can be included any future relevant projects.

4. The emergence and formation of the Tehran-Karaj urban region

In 1797, Tehran had only 15,000 inhabitants and even 125 years later, in 1922, its population was no larger than 200,000 people, who inhabited an area of around 24 km2. The first steps towards modernizing Iran through creating new street networks, a university, railway stations and so forth, attracted new migrants to Tehran and its population then grew to 500,000 in a period of less than 20 years, in an area that had expanded to 45 km2. From 1940 onwards, due to the concentration of capital, new economic investments and the growth of central governmental administration, Tehran was transformed into the main economic, as well as administrative centre of Iran. Consequently, the population of Tehran tripled in the period between 1940 and 1956, reaching a new peak of around 1,500,000 inhabitants.

To accommodate the swelling population, the lands surrounding the city core were built over in all directions, and thus the area of the city grew fourfold larger than before and reached 180 km2 by 1965. This enhanced the process of concentration in Tehran, so that “By the mid-1970s, Tehran – with less than 20% of the country’s population – had more than 68% of its civil servants; 82% of its registered companies; 50% of its manufacturing production; 66% of its university students; 50% of its doctors; 42% of its hospital beds; 72% of its printing presses; and 80% of its newspaper readers” (Abrahamian Citation2008, p. 142).

However, the 1968 Act prohibiting the establishment of new industrial units inside Tehran’s peripheral zone of 120 km forced new industrial development to take place outside of the city limits. This both generated new settlements and caused extensive expansion to already extant small settlements (Davoodpour Citation2009). Due to this rapid development as well as the construction of the Tehran-Karaj Highway in 1967, the population of Karaj, which was 44,000 in 1966, grew to 1 million by 1996. Islamshahr, only a small village of 1006 inhabitants in 1966 was transformed into a city of 270,000 inhabitants (Mashhadizade 2010), and some other cities with 100,000 inhabitants, such as Qods, Gharchak and Varamin were established.

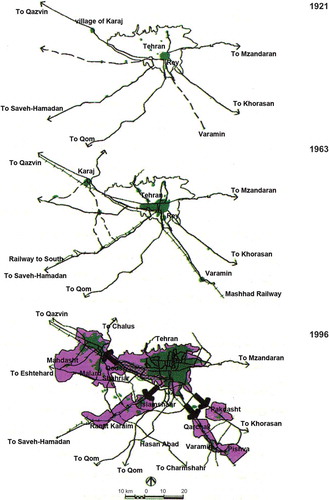

Ultimately, the originally compact and mono-nuclear region was transformed into a sprawling multi-nuclear structure, with Tehran at its centre, but with different urban cores expanding mainly in the western and southern parts of the province. However, in this polycentric formation, Tehran always was and remains the main core; other zones, with the exception of Karaj, suffer from under-development and are lower class residential settlements with insufficient urban facilities and low standards of life ().

Figure 1. Structural evolution of the Tehran–Karaj urban region, modified from Ghamami et al. (Citation2006).

The Tehran-Karaj urban region embraces Tehran and the newly established Alburz provinces, including two major cities of Tehran and Karaj and their surrounding settlements and industrial districts which are structurally combined with each other. It consists of 17 counties (Shahrestan): the 13 counties of Damavand, Islamshahr, Firuzkuh, Rey, Rabat-Karim, Shemiranat, Tehran, Varamin, Pakdasht, Pishva, Shahriar, Malard, and Qods, in Tehran province, and the 4 counties of Karaj, Nazarabad, Talegan, and Savejbolag in Alburz province.

The region is located in the central north part of Iran, on the southern fringes of the Alburz Mountains, and has an area of 18,800 km2 (of which 47% is mountainous, 18% is agricultural lands and forest and 15% is infertile lands). The limits are Mazandaran in the north, Qazvin in the west, Semnan in the east and the Qom and Markazi provinces in the south. Because of the particular location of the Tehran–Karaj urban region, it has a range of climates; the northern mountains are 1500 meters high with low temperatures and more humidity culminating in a southern plain and desert with high temperatures and low humidity. Therefore, more than 95% of the population of this urban region and its main industrial activities are concentrated in the 30% middle plain area, where the northern mountains and southern deserts are not well populated due to their natural conditions.

In 1966, the total population of this region was about 3,460,000, of whom 80% belonged to the city of Tehran. This figure had grown to 10,350,000 in 1996, by which time Tehran’s share had fallen to 65% (). The contribution of Tehran’s urban population to the urban population of the Tehran–Karaj urban region remains slightly greater, although it has decreased from 95.7% in 1966 to 92% in 1976, 83.9% in 1986, and 78.7% in 1996, and stood at about 50% in 2006 (Zanjani Citation2002). This fluctuation does not mean a decline in the population of Tehran, but indicates that a significant percentage of the total population of the Tehran–Karaj urban region has settled in the newly established or newly developed peripheral settlements, some of which, like Islamshahr, Gods and Gharchak, have transformed into middle-sized cities and created centralities within the urban region ().

Table 1. Population of the Tehran–Karaj urban region in different censuses.

Table 2. Contribution of Tehran’s urban population to the urban population of the Tehran–Karaj urban region.

In 1996, 86.2% of the entire population (10.3 million) of the Tehran–Karaj urban region was an urban population, and only 13.8% (1.43 million) was rural. In general, the growth of the rural population in this urban region was much greater than the average across the country, since new immigrants settled intensively into its small villages and rural areas for economic and social reasons. Thus, both over the period from 1976 to 1986, and in 1986–1996, the rural population doubled, while in the latter period, the entire population of Iran grew by only 3%. Over a 30 year period (1966–1996), while the rural population of Iran grew by 1.61 times, the rural population of the Tehran–Karaj urban region expanded by 4.95 times (ibid.), as a result of which the originally rural settlements burgeoned in size and population, mainly in an informal way, to the point where they were finally recognized as urban areas and cities. Average population density in this region in 2005 was 5.3 persons per hectare (pph), while in the city of Tehran, it was 92 pph, and in the region outside Tehran, it was 1.9 pph.

The Tehran–Karaj urban region can be divided into eight urban areas as follows ():

Figure 2. Tehran–Karaj urban region, administrative division modified from Habibi and Hourcade (Citation2005).

The Tehran urban area: the city of Tehran, with a population of 7.7 million in 2006 (6.8 million in 1996), includes 58% of the total population of the urban region, accounting for more than 10% of the country’s population. This city has the largest concentration of population as well as wealth in the country. It is divided into 22 districts and 112 sub-districts.

The Karaj–Shahriar urban area: this is located in the west of Tehran and includes Karaj and its surrounding cities and villages such as Shahriar, Qods, Andishe, Mohammadshahr and Malard. This urban area is very attractive for new developments and settlements, as well as industrial activities due to its vicinity and good access to Tehran, moderate weather and agricultural lands.

The Islamshahr–Robatkarim urban area: this is located in the south-west of Tehran and includes cities and villages along the Saveh Road, such as Islamshahr and Robatkarim. This urban area is in the vicinity of a number of industrial centres and hence very popular with low-income families.

The Varamin urban area: this area consists of the three urban zones of Gharchak, Varamin and Pishva, located along the Varamin road.

The Pakdasht urban area: this consists of the urban zones located along the Khavaran road. This urban area is located at the south-east of Tehran, 25 km away from Tehran, with Pakdasht at its centre.

The Hashtgerd urban area: this urban area is located in the west of Karaj, along the Karaj–Qazvin highway, and includes the cities of Hashtgerd, Nazarabad and Hashtgerd New Town. The New Town of Hashtgerd and the Industrial Region of Hashtgerd are intended to function as a very important and attractive residential as well as industrial centre.

The Damavand urban area: situated at the east of Tehran, this includes the cities of Rudhen, Bumhen and Pardis New Town. It is located on a highland with limited development possibilities, but is suitable for tourism due to its mountain-region climate.

The Eshtehard urban area: this is located at the south of the Hashtgerd urban area and is limited to the small city of Eshtehard.

5. Inter-urban connectivity, regional challenges

All of the above-mentioned urban areas are structurally and socially interconnected and interwoven through an inefficient transportation network, and together constitute an urban region with a high level of social and economic interactions. Nonetheless, because of the imbalanced distribution of urban facilities, it is a very heterogeneous region and hence essentially unsustainable in terms of its social, economic as well as ecologic aspects, suffering from some crucial problems and facing essential challenges. These challenges, however, neither originate solely within a particular urban zone nor is their influence limited to its boundaries; they are essentially interconnected within other surrounding zones.

To explore the nature and characteristics of this interconnectivity, it would be particularly informative to focus on three issues of migration, transportation and air pollution. Migration has played a vital role in the demographic fluctuation of this region. In the 1960s, economic growth attracted a large number of people from all over the country to live here, a trend which was intensified by the oil boom of the 1970s. After the Islamic Revolution, the revolutionary government’s promises of cheap housing and a lower cost of living, as well as large numbers of refugees from the Iran–Iraq war, meant a great influx of population to Tehran (Madanipour Citation1998). At a regional scale, between 1976 and 1986, more than 1.2 million people migrated to the Tehran–Karaj urban region. Over the next 10 years, this number increased to 1.9 million, 30.7% of whom went to Tehran, 23.1% to Shahriar and 18.9% to Karaj. Of these migrants, 68.2% settled in urban areas, while 31.8% chose rural areas (Zanjani Citation2002). Even for those settled in neighbouring cities and settlements, Tehran is the main location for employment. For example, a study conducted in 2000 shows that 76% of the workers living in the city of Bager-shahr (27 km south of Tehran), and 71% in the city of Salehiyeh (24 km south-west of Tehran), work in the city of Tehran (Zebardast Citation2000). Currently, 60–70% of those Iranians who change their place of residence move to Tehran (Habibi & Hourcade Citation2005).

The main tool for creating an efficiently connected polycentric urban region is the establishment of a working transportation network, although in this regard, the region has considerable deficiencies. The Tehran–Karaj urban region is networked through the conventional transportation systems of roads, railway and metro, but the predominant and most comprehensive of these is the road system. In 2006, a network of roads 4540 km in length was in service. Generally speaking, in this urban region traffic mainly consists of private cars (more than 65% of journeys), with an average number of passengers per private car at 2.23 (Labbafi Citation2002). The contribution made by public transportation is very low (bus, 5% and minibus, 8%). Although the railway network serves different urban zones, its contribution to the transportation system of the Tehran–Karaj urban region is very low. Currently extending to a length of 108 km distributed over four lines, the Tehran metro transports more than 800,000 passengers daily. However, it mainly functions on an intra-urban scale, except for line 4, which extends to Karaj in the west.

The major proportion of daily traffic is due to the distance between working place and place of residence, which results from an inefficient distribution of economic activities and their concentration in Tehran. A study conducted in 1993 shows that 45% of journeys to Tehran are for working purposes, while 26% are those returning to the place of residence. On the contrary, 31% of journeys from Tehran are for working purposes, and 44% to return to the place of residence (Sherkate Motale’te 1994). This indicates that Tehran is the main destination and that a major proportion of journeys are for the purpose of working in the city. Poor people, who for economic reasons attend a place of work at a considerable distance from their accommodation, suffer more than other inhabitants from the inefficiency of the transportation system. A field study shows that 50% of the inhabitants in marginal areas and outskirts of the city spend 3 hours on the daily commute, while the poorest 15% of them spend more than 4.5 hours getting to and from work, and the cost of this commuting comes to about 30% of their income (Ghamami Citation2004, p. 15).

This inefficient public transportation system encourages people to opt for the private car, which generates significant air pollution and congestion. In general, more than 95% of the air pollution in the Tehran–Karaj urban region is generated through the consumption of fossil fuels, either in industrial units (complexes or isolated) or urban and residential units. Industrial units, the biggest polluter being brickmaker units, produce toxic gases aggravated by the inversion phenomenon of the region’s semi-arid climate (Riazi Citation1998). In urban areas, air pollution is mainly generated by motorized vehicles (85–95%) and residential and commercial heating systems (5–15%). Despite a recent cut in energy subsidies at the national level, among them fuel and petrol, the inhabitants’ growing tendency to travel by private car has not diminished and air pollution remains one of the major challenges for the entire region.

This short review shows that the existing challenges are essentially interwoven, with the implication that any purely sectorally based observation and planning may fail to achieve its objectives. For instance, although the region’s larger cities, such as Tehran and Karaj, suffer from the problem of air pollution more than other areas, the origins and reasons for this are not only limited to these cities. In fact, air pollution in urban areas, generated mainly by vehicular traffic, is due to the unbalanced distribution of jobs, which exacerbates both inner-city and inter-city journeys; a further reason is the lack of sufficient public transportation at the regional scale; the lack of green space to mitigate urban pollution; and many other issues. Therefore, air pollution is generated by diverse sources, intensified by diverse problems, and necessitates diverse improvement policies, which are all essentially connected to each other at the regional scale, meaning that any purely sectoral effort may eventually fail. Thus, to tackle the existing problems, initiatives need to be developed which understand, analyse and plan the entire region as one agglomeration.

The next section will concentrate on the crucial problem of urban management and governance in this region to reveal and illuminate obstacles and difficulties which make efforts at regional planning and governance problematic.

6. Between fragmentation and defragmentation

The case of the Tehran–Karaj urban region shows that, like Randstad, it is managed by a range of local administrative bodies. For example, in 2004, 36 municipalities, 12 governmental units and a number of ministries were put into service without any organized cooperation or following any general comprehensive policy (Ghamami Citation2004). This figure rose to 30 governmental units and more than 50 municipalities by 2010 (Akhundi & Barakpour Citation2010). shows how the number of administrative divisions and consequently the number of responsible administrative bodies have been increased over recent decades. However, unlike the Randstad, there is currently no intention to create an integrated management system for the region, with the exception of a few past initiatives that have been totally forgotten. On the ground, the principal administrations, such as the ministries, advocate general policies that overlook sectoral aspects, while local institutions highlight narrowly delimited issues and ignore general prerequisites.

Table 3. Administrative division in Tehran–Karaj urban region in the last decades.

The lack of an integrated management system in this region is intensified because the existing framework for services is based on the three zones of “city”, “city boundary” and “beyond the city boundary” (). According to this framework, urban affairs inside a city and its boundary are managed by the municipalities, but issues relating to the “beyond the city boundary” zone are managed by different governmental units that include Ostandari (provincial governorship), Farmandari (urban governorship) and Bakhshdari (sectoral governorship). This system of service division disregards areas located in the immediate vicinity of the cities. Since municipalities do not take responsibility for providing the necessary urban services and integrating them into urban development and management programmes, their influence on and structural connection to the city is ignored and disregarded. This management system covers the whole country, but in an inefficient manner:

Since in this framework “city” and “city boundary” are separated from the “beyond the city boundary”, their management is also separated and independent. This division may work in small cities which are located far from each other, but in the case of urban regions, not only the “city boundary” but also what is located “beyond the city boundary” is affected by the development of the regional elements and their interactions. (Ghamami et al. Citation2006)

In other words, the zones between different “city boundaries” are no longer separated pieces of land, but form city-related zones; they necessitate an integrated and unified management system to tackle their problems and challenges.

Another crucial problem which hinders establishment of an integrated management and governance system is the lack of an appropriate regional administrative level in the existing governmental system of Iran. As can be seen is , governance hierarchy in Iran starts from the national level as the highest rank but immediately downs to the provincial level (now 31 provinces in sum). Other governance sectors are intra-provincial, each dealing with a part of the province. In this sense, the administrative level for an urban region with inter-provincial coverage (like the case of Tehran–Karaj which includes two provinces of Tehran and Alburz) remains undefined and ambiguous. This indeterminacy is also problematic for other urban regions such as Tabriz and Isfahan where they cover only a part of the province and its subdivisions.

Table 4. Levels of governance in Iran (Author).

The only attempt with regard to providing a comprehensive plan for the Tehran–Karaj urban region dates back to the end of 1990s, when the state submitted a “Plan for the Tehran Urban Region” together with some of the other major cities of Tabriz, Isfahan, Mashhad and Shiraz. This plan, finally approved by the government in 2002, considered the region in the light of a “polycentric complex” and applied a “decentralized concentration” approach, through which new urban zones would play a vital role in providing sufficient urban facilities and a high quality of life for their inhabitants. The aim of this plan was to introduce appropriate siting for future settlements as well as industrial units, to plan an efficient traffic system and enrich regional green spaces, through the decentralization of Tehran and dispersion of the population to other settlements of the region, aiming for an estimated population of 17.7 million by 2021 (Markaze Motale’t Citation2002). Moreover, it was suggested that the main prerequisite for creating a working urban region would be the establishment of a “Management Institution of the Tehran Urban Region”, the task of which was to provide the regional plan, collaborate with the top-level management institutions and the local administration and monitor the plan’s implementation. Unfortunately, this plan was never properly taken into consideration by the government and the region’s urban managers and remained on the shelf, to the extent that the Tehran Municipality, unmindful of the plan’s proposals and recommendations, and ignoring the necessity for a comprehensive management system, decided to go its own way and set about preparing a new master plan for Tehran which gained approval in 2006. Thus, the Tehran Municipality, as the greatest and wealthiest management institution with considerable fiscal and administrative independence, has been able to follow its own policies without concerning itself about the smaller cities; while the smaller cities try to work within the framework of some small-scale but separate short-term plans which mainly focus on tackling their own problems. Studies prove that the regional scale is given little recognition in the development plans for the Tehran–Karaj urban region; only 3 out of 15 existing plans show even slight attention to the regional aspects of this urban region (Akhundi et al. Citation2007).

A comparison between the two cases of Randstad and Tehran–Karaj urban region and the way these two urban regions deal with their problems shows that while the former has extensively recognized the question of interconnectivity and the urgency of an integrated management authority, has planned for a more efficient urban region and has implemented different initiatives and programmes to achieve its goals, particularly in the last 30 years, the latter has confirmed the process of interconnectivity, planned in some exceptional periods for an efficient urban agglomeration, but has never seriously implemented the plans or even provided necessary prerequisites for its realization. In other words, while an “institutional integration” and “functional integration” approach can be observed in the Randstad region, in the Tehran–Karaj Region, this approach has not been properly taken into account. In reality, unlike the case of Randstad in which concrete steps have been taken towards an integrated governance by means of progressive initiatives such as Deltametropolis Association, Regio Randstad, Randstad Transport Authority and Randstad Urgency Program, no single serious pace has been taken by the responsible administration in Tehran–Karaj urban region to make any regional planning and management feasible. Surprisingly, in 2010, this region which was limited to the Province of Tehran was divided into two provinces after the establishment of the new province of Alburz with the centrality of Karaj, and thus the governance of the entire region got more fragmented, any attempt towards an integrated management system, more unattainable. Thus, the two provinces may submit different plans and programmes for new development, handle their problems independently and without considering the interdependency of the issues they address. Obviously, this decision goes against the “institutional and functional integrity” needed for an efficient urban region, since dividing the region into two separate governmental bodies which necessitates two parallel provincial planning and management systems will exacerbate existing institutional disparity and functional disconnectivity. More recently, tensions have arisen between the state on the one hand and Tehran Municipality and Tehran City Council on the other, regarding the removal of Share-Rey from Tehran Municipality and its treatment as a separate city with an independent municipal government. Thus, a part of southern Tehran which is currently considered as “District 20”, was to be managed independently, despite its socio-cultural and structural connectivity with other districts of Tehran. The execution of this plan, which was politically rather than administratively inflected, was finally stopped and postponed by the Court of Administrative Justice.

Despite these facts, it has to be reaffirmed that to tackle the current multifaceted problems of the region in an effective way, the establishment of an “integrated management and monitoring administration” is a must. The main tasks of this centre could be categorized into two major fields: policy-making and monitoring. In the field of policy-making, the first step would be providing a “Comprehensive Sustainable Plan for the Tehran–Karaj Urban Region”, a regional master plan which takes into consideration the potentiality of all components in a systematic way and highlights their interconnectivity. This also necessitates some revisions to the existing national planning system, within which the regional scale has not, to date, been taken into account (Akhundi & Barakpour Citation2010). Consequently, all the existing master plans of the different component areas would be obliged to adapt themselves in conformity with the aims, objectives and proposals of the comprehensive plan. But to ensure the realization and implementation of this plan, a monitoring system must be designed for this integrated management administration to be able to control the extent to which the new initiatives and development plans are carried out in conformity with the framework of the comprehensive plan on the one hand, and to monitor fulfilment of the comprehensive plan by the local administration on the other. As long as there remains no awareness at the policy-making level for such a requirement, the Tehran–Karaj urban region will suffer increasingly from the current fragmented management system and administrative crowdedness, and its existing challenges and problems will gradually intensify.

7. Conclusion: an imprudent course of fragmentation

The emergence and formation of the Tehran-Karaj urban region was not based on a development programme, but rather emerged in the absence of any long-term plan and concomitant changes in policies and strategies. This formation was the result of an extensive urban growth of the city of Tehran, a small town before becoming the capital of Persia, to adapt itself to the prerequisites of modernization and industrialization. However, this rapid pace of modernization and industrialization was never limited to the city itself, but influenced the entire region; peripheral villages and settlements were absorbed into the growing city, farther settlements grew and grew as the affordable accommodation place for the new migrants. The outcome was an inefficient urban conglomeration that presents severe social, economic, ecological and governmental challenges.

One major issue is that the various components of this conglomeration are not isolated units, but are socially and physically interconnected. Therefore, any sectoral management approach in which each component is planned and considered separately would never be adequate to meeting the current challenges and problems. Despite this fact, there exists a severe governance fragmentation, each sectoral administrative mainly plans and acts isolated from the entire region. It has been internationally acknowledged that to cope with the multifaceted issues of an urban region, an integrated authority is required to bring all the administrative fragments under an all-encompassing umbrella, provide common frameworks and visions in the form of spatial strategies and plans for the entire region, but give the engaged administrative units enough space for their local actions and initiatives. In other words, institutional integrity will enable regional governance to plan for functional integrity and achieve an efficient urban region. A review of the case of Randstad showed how this concern has been recognized and seriously put onto the agenda in the last couple of decades. This will, however, is quite absent in the case of Tehran–Karaj urban region.

Two major problems in this region are the lack of efficient service coverage and regionally adaptive level of management in the existing governance system. On the one hand, there is an ambiguity of service area and multiplicity of responsible administrative unit. On the other hand, existing governance system has not recognized a mediatory level of governance between the national level and the provincial level, so that any inter-provincial planning and decision-making process may face crucial overlapping. The case of Tehran–Karaj urban region shows that these challenges are problematic enough to hinder any regional planning; the only attempt to think and plan for this polycentric region in the form of “Plan for the Tehran Urban Region” failed, its recommendations and suggestions remained unattended. In reality, one observes a growing will to fragmentation, for which recent division of the Tehran Province into two separate provinces is a clear hint.

Obviously, the establishment of an efficient integrated management system, as has been advocated for a number of prominent cases elsewhere, may provide a framework within which each unit is able to meet its own plans and priorities, but also taking into consideration its connectedness to the issues and priorities of the entire region. Without such a management system, every effort to remedy the current situation to an acceptable state may either remain on paper, or founder in achievements that are fragile and unsustainable.

References

- Abrahamian E. 2008. A history of modern Iran. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press.

- Akhundi A, Barakpour N. 2010. Rahbordhaie Estegrare Nezame Hokmravaii dar Mantageie Kalanshahrie Tehran. Rahbord. 57:298–324.

- Akhundi A, Barakpour N, Asadi I, Taherkhani H, Basirat M, Zandi G. 2007. Hakemiate Shahr-mantage Tehran: Chaleshha va Ravandha. Honarhaie Ziba. 29:5–16.

- Bianca S. 2000. Urban form in the Arab world: past and present. Zürich: Vdf.

- Champion AG. 2001. A changing demographic regime and evolving polycentric urban regions: consequences for the size, composition and distribution of city populations. Urban Stud. 38:657–677.

- Davoodpour Z. 2009. Ta’adol bakhshie Shahre Tehran. Tehtan: Vezarate Maskan va Shahrsazi.

- Davoudi S. 2003. Polycentricity in European spatial planning: from an analytical tool to a normative agenda. Eur Plann Stud. 11:979–999.

- Davoudi S. 2007. Polycentricity: Panacea or pipedream? In: Cattan N, editor. Cities and networks in Europe: a critical approach of polycentrism. Surrey: John Libbey Eurotext.

- Dieleman F, Faludi A. 1998. Polynucleated metropolitan regions in Northwest Europe: theme of the special issue. Eur Plann Stud. 6:365–377.

- Dielman F, Dijst M, Spit T. 1999. Planning the compact city: the Randstad Holland experience. Eur Plann Stud. 7:605–621.

- Faludi A, Waterhout B, Royal Town Planning Institute. 2002. The making of the European spatial development perspective: no master plan. London: Routledge.

- Ghamami M. 2004. Tarhe Rahbordie Tose’ie Kalbadi. Tehran: Centre for Iranian Urbanism and Architecture Studies.

- Ghamami M, Khatam A, Athari K. 2006. Modiriate Yekparche va Halle Mas’leie Eskane Geire-Rasmi. Tehran: Shahidi.

- Gottmann J. 1961. Megalopolis: the urbanized northeastern seaboard of the United States. New York (NY): The Twentieth Century Found.

- Habibi S, Hourcade B. 2005. Atlas of Tehran metropolis. Tehran: Pardazesh va Barnamerizie Shahri Publication.

- Hall P. 1996. From new town to sustainable social city. Town Country Plann. 65:295–297.

- Hall P. 1997. Modelling the post-industrial city. Futures. 29:337–355.

- Hall P. 2007. Delineating urban territories. Is this a relevant issue? In: Cattan N, editor. Cities and networks in Europe, a critical approach of polycentrism. Surrey: John Libbey Eurotext.

- Hall P, Pain K. 2006. The polycentric metropolis, learning from mega-city regions in Europe. London: Earthscan.

- Hendriks F. 2006. Shifts in governance in a polycentric urban region: the case of the Dutch Randstad. Int J Public Adm. 10:931–951.

- Kazemian G. 2009. E’tegad be Modiriate Yekparche Niazmande E’temade Motagabel Ast. Manzar. 3:44–45.

- Kloosterman R, Musterd S. 2001. The polycentric urban region: towards a research agenda. Urban Stud. 38:623–633.

- Labbafi A. 2002. Motaleate Haml o Nagl o Terafik. Tehran: Centre for Iranian Urbanism and Architecture Studies.

- Lambregts B, Janssen-Jansen L, Haran N. 2008. Effective governance for competitive regions in Europe: the difficult case of Randstad. GeoJournal. 62:45–57.

- Laquian A. 1995. The governance of mega-urban regions. In: MacGee TG, Robinson IM, editors. The mega-urban regions of Southeast Asia. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Lefèvre C. 1998. Metropolitan government and governance in western countries: a critical review. Int J Urban Reg Res. 22:9–25.

- Madanipour A. 1998. Tehran, the making of a metropolis. Chichester: Wiley.

- Markaze Motale’t. 2002. Tarhe Majmooeie Shahrie Tehran. Tehran: Markaze Motaleat.

- Mashhadizade Dehgani N. 2010. Barnamerizie Shahri dar Iran. Tehran: IUST Publishing Center.

- OECD. 2007. Territorial reviews: Randstad Holland, Netherlands. Paris: OECD.

- Riazi B. 1998. Kholase Gozareshe Motaleate Moihite Zist. Tehran: Centre for Iranian Urbanism and Architecture Studies.

- Salet W. 2011. Innovations in governance and planning, Randstad cooperation. In: Xu J, Yeh A, editors. Governance and planning of mega-city regions, an international comparative perspective. New York (NY): Routledge.

- Salet W, Thornley A, Kreukels A. 2003. Metropolitan governance and spatial planning. London: Spon Press.

- Scott AJ. 2002. Global city-regions: trends, theory, policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sherkate Motale’te Jame Haml o Nagl. 1994. Motale’te Jame Haml o Nagl va Terafike Tehran. Tehran: Tehran Municipality.

- Storm E. 2006. Randstad Holland synergy in perspective: position and history, ambition and policy. In: Salet W, editor. Synergy in networks? European perspectives and Randstad Holland. The Hague: Sdu Uitgevers.

- Sykora L, Mulicek O, Maier K. 2009. City regions and polycentric territorial development: concepts and practice. Urban Res Pract. 2:233–239.

- Zanjani H. 2002. Gozideie Motaleate Jam’iati. Tehran: Centre for Iranian Urbanism and Architecture Studies.

- Zebardast E. 2000. Barrasie Ertebate Amalkardi Sokoonatgahhaie Khodro Atrafe Kalanshahre Tehran. Honarhai Ziba. 8:65–73.