Abstract

The creative city is a city able to generate economies of innovation, culture, research and artistic production, and strengthen its own identity capital. Looking at the experiences of creative cities, it may be observed that they revolve around the design, promotion and activation of urban areas established due to their particular local characteristics. Those areas become creative clusters as a result of economic and structural innovation, which is related to the execution of innovative projects achieved with the help of local development strategies based on the economy of excellence and territorial qualities. The most mature experiences of creative cities show us two types of creative clusters: cultural, which are created around activities such as fine arts, music, cinema, architecture and design, and whose initiation is encouraged and planned by local administration; and events, whose development stems from the organisation of major events or different kinds of recreational and cultural manifestations. Starting from such premises, this paper aims to explore the concept of creative cities and the main factors conditioning creativity in cities. These topics are addressed most directly in the literature review, with two case studies deepening understanding of the pragmatic strategies and processes underlying redevelopments within creative city framework. The two examples of creative urban projects concern Arabianranta in Helsinki, for the events cluster framework and HafenCity in Hamburg, for the cultural cluster framework. These cases inform a more sustainable version of creative city that is anchored in local history and identity, local economic nourishment and participation in redevelopment process and emphasise this endeavour as a process, thus incorporating risk and uncertainty.

1. Premises

The concept of the ‘creative city’ (Florida Citation2002, Citation2005) has its origin in the research into reasons why several cities have become more attractive and competitive in recent decades. Such cities seem to have worked on how to improve the interaction between urban regeneration, economic development and social renewal in order to achieve more comprehensive development of the city (Carta Citation2004). The cultural resource, if appropriately inserted inside a suitable plan able to create employment and new occupations as well as economic development, constitutes the trigger of a process of evolution of the territorial system and of all social actors and, at the same time, a process of creation of a network of culturally sustainable development (Hall Citation1998; Evans Citation2001; Neil Citation2004). Indeed, a type of approach based on the acquisition of the cultural heritage in its meaning of creative resource represents a substantial change in the management of a territory because rather than being viewed as a commodity, ‘cultural heritage’, culture is seen as a resource able to offer added value to the territory (Sepe Citation2004, Citation2006). In the perspective provided by these approaches, culture in its broadest sense assumes a decisive role in constructing a system of interventions where employment, tourism, and social and sustainable development becomes the product of the integration of places, people, economies and traditions (Scott Citation2000).

Looking at the experiences of creative cities, it may be observed that they revolve around the design, promotion and activation of urban areas established due to their particular local characteristics. Those areas become creative clusters, in accordance with the evolving definition of clusters which has changed in recent years from the traditional view, which saw them as containers conveying production flows, to a broader definition which identifies new features, directly related to the history and culture of the areas in question (Caroli Citation2004). These clusters are a result of economic and structural innovation, which is related to the execution of innovative projects achieved with the help of local development strategies based on the economy of excellence and territorial qualities (Mommaas Citation2004; Roodhouse Citation2006; Bagwell Citation2008).

Starting from such premises, the aim of this paper is to investigate the concept of creative cities and the main factors conditioning creativity in cities. Two examples of creative clusters – in Helsinki and Hamburg – are illustrated. These examples were chosen because they are related to city projects which, starting from the regeneration of waterfronts, are changing the urban image in different ways, recovering entire areas of the city for residential, cultural and service uses. During the operations of urban transformation, particular attention was taken to achieve the right balance between place identity and innovation, attractivity and sustainability of the interventions, and urban policies and participation.

The study was part of a wider research project entitled ‘The transformations of the contemporary city: analysis and design of the place identity for the sustainable enhancement of Cultural Heritage’, coordinated by the author, carried out in the context of the research programme ‘Innovation and competitivity in the global economy’, in development by the Institute of Service Industry Research of the National Research Council. In particular, the study presented in this paper is related to the identification of the best practices of urban regeneration in Europe, which will be dealt with in Section 4 devoted to methodology.

We choose the cases of Helsinki and Hamburg, each related to one kind of cluster. These two operations of urban transformation illustrate both how to obtain a proper balance between place identity and innovation, attractivity and sustainability of intervention, ensuring the involvement of the population, and how the socio-cultural contexts affect the type of creative regeneration that is undertaken.

The paper, which presents both theoretical and practical aspects, is organised as follows: Section 2 shows the main factors which determine creative urban change; Section 3 shows the new policies to be activated in order to obtain creative regeneration; Section 4 illustrates the methodology; Section 5 illustrates two emblematic case studies; Section 6 draws the conclusions.

2. Factors determining creative urban change

The first two elements which were identified as fundamental in creative urban transformation are place identity and innovation. Although at a first glance they could seem quite different, if suitably mixed they actually constitute the main factor of success. As the cases of Helsinki and Hamburg – which respectively started their regeneration from the history of the place and the maritime identity – will show, recognising the value of place identity as a fundamental component in implementing urban change serves as a reference point both in terms of society’s wishes and in safeguarding and constructing the sustainable urban image (Carter et al. Citation1993; Castells Citation1997). Built heritage narratives facilitate the creation and enhancement of national identities by ‘denoting particular places as centres of collective cultural consciousness’ (Graham Citation1998). Cities have to find out how to reduce the risks inherent in the tendency of contemporary urban societies to fall back on their heritage and roots as they face up to an identity crisis. In this respect, innovation in urban space design represents an opportunity to construct an identity of places and give international scope to the urban form of European cities (Massey & Jess Citation1995; Gospodini Citation2004).

The creative city is a city able to generate economies of innovation, cultures, research and artistic production, strengthening its own identity capital. It is a question not only of boosting the economies of culture but also producing new economies, starting from cultural capital, which is seen as an element of the maximum expression of place identity – both tangible and intangible – and forming a system together with other urban capital (Hague & Jenkins Citation2005; Carta Citation2007).

Culture is a resource that occupies a pivotal role in socio-economic development. Indeed, the industry of culture covers a set of activities, such as cultural heritage services, fundamental to launch a country’s economy. Florida (Citation2002) has observed the relationship which exists between changes in the capitalist mode of production – in particular, those occurring at the urban scale including clusters of high-tech firms, the dissemination of leisure activities and urban economic networks – and changes in terms of identities of the actors involved. He argues that the more attractive cities are able to seem to the creative class of workers and managers in the various sectors of economy such as art, design, fashion and advanced technologies services, the greater are the chances that those cities can successfully face the challenges of competition among cities imposed by globalisation (Keivani & Mattingly Citation2007). Indeed, creativity is found not only in the typical characteristics of the entrepreneurial spirit but also in forms such as the spread of behaviour that is favourable to cultural exchange as well as the enhancement of lifestyle diversity.

One must also consider who are the promoters and beneficiaries of the creative city to prevent disadvantaged players being considered less influential in urban regeneration and, in general, in the success of the desired transformation. The most successful urban regeneration projects are those where there is a strong involvement of local pre-existing identity and where recovery of the sense of place, history and belonging to the local community is expected (Comunian & Sacco Citation2006; Sepe, Citation2013a, Citation2013b). In this way, the creative city recognises complexity and addresses the spatial, physical and land use conditions which help people to think and act with their imagination and live the city as a satisfying experience.

Attractivity and sustainability are the second pair of factors for which, although in apparent contrast, a proper balance assures the success of the creative process and results on the territory. In both the case studies which will be presented, the respect of the environment was interpreted as an occasion of development and improvement of liveability of the places, such as the creation of specific public spaces, the particular way of shaping the vegetation, and so on. As the literature shows us, the experiences of creative cities can lead to the promotion of areas of cities which base their competitiveness on local peculiarities related to the value of the ‘city brand’ and also highlight the possibility of guiding evolution of urban systems in the city (Anholt Citation2011). Such city areas become true creative clusters as a result of innovative economic and structural initiatives, implemented within appropriate local development strategies based on territorial quality and excellence (Caroli Citation2004).

The formation of creative clusters must be accompanied by the construction of lines of action to make the factors of development, enabled by the cluster, consistent with the identity and sustainable growth of the city (Nijkamp & Perrels Citation1994; Richards Citation1996; Sacco & Tavano Blessi Citation2005). Creative resources are usually more sustainable than physical ones: monuments and museums are inevitably subject to degradation, while creative resources are constantly renewable. Furthermore, creativity is more mobile, because it does not depend on concentration of cultural resources and can be produced anywhere. Furthermore, the development of a creative cluster has to be considered alongside sustainable development in the economic, social and environmental sense (Ferilli & Pedrini Citation2007; Keivani Citation2010), conditions which are equally important and interdependent for the sustainability of cultural resources.

The economic sustainability of culture as a resource depends on a complex system of balances and social actors which may become decoupled as a result of an overly instrumental attitude towards the economic potential of culture (Zukin Citation1995; Comunian & Sacco Citation2006). Although culture and cultural institutions have benefited from the recognition of its social and economic value, it must be borne in mind that when public policies primarily focus on the potential of developing culture, the result is a gradual loss of attention towards intrinsic motivation of the production and consumption of culture; particular emphasis is laid on its economic benefits. As Comunian and Sacco argue, the risk of this type of operation is to conclude that ‘all that is creative is good’, relegating to second place the quality of projects and initiatives.

Thus, economic sustainability can be defined as ‘the ability to generate income, profits and work within a system of equal opportunities for all the elements of society, inside a model which enhances and increases land resources, and furthermore does not produce a collapse of the same in quantity or quality’ (Ferilli & Pedrini Citation2007). The characteristics of territory, seen as a complex system where tangible and intangible cultural resources become elements of a chain of added value, assume a key role in developing the local system. In this way the cluster, starting from the elements of territory and their enhancement and promotion, will be economically sustainable in the long term.

Social sustainability is the ‘ability to ensure welfare conditions and growth opportunities equitably distributed in society’ (Ferilli & Pedrini Citation2007). Setting up a development model based on enhancing culture fosters social regeneration in the area, generating in people a perception of belonging, an increase in the social capital, the change in place image and an increase in the level of education. Cultural production and use perform functions of generation and dissemination of creative thinking. Furthermore, this use provides tools for the growth of individual opportunities by creating a process for socially sustainable development.

With respect to environmental sustainability, the area should be understood in its various historical and cultural values, and in its tangible and intangible capital. Territory is characterised by both types of capital and its identity cannot be considered separately from them. However, even if the consequences of resource depletion on the nature of territory are known, depletion of intangible capital is less evident, although just as important. It is therefore necessary to create a close relationship between production systems and central areas, so that companies interact in processes which generate value for the territory.

3. New polices

3.1. Urban policies and participation

The creation of suitable urban policies represents a fundamental element which enables the process of transformation to start. Participation, which has to be activated from the initial stages of the process, assures – as in the cases of HafenCity and Arabianranta – the good development of the project. Changes in the city can be seen in the strong role of culture and in the processes of social empowerment. Indeed, the engine of social change is no longer technology, but how you live, work and play, and the places where these activities take place.

The creation of an urban environment which encourages setting up innovative activities requires, at the local level, the construction of a specialised production system and the establishment of an urban environment which can support the testing of consensual practice of regional government (Scott Citation2006). In order to obtain this goal, new alternative strategies and urban policies should be considered. Traditional policies of urban renewal, mainly based on combating social exclusion and building physical constructions, must change. Indeed, cities are not just buildings and material structures, but also people, networks and intangible elements, such as memory, history, social relationships, emotional experiences and cultural identities. Indeed, the city is an organism; each element is inextricably interwoven and planning is based on how people feel the city from an emotional and psychological point of view. Its guiding principle is place-making rather than urban development (Landry Citation2008). The transformation of cities has been accompanied by changes in the urban design and planning tools, modifying those already existing and creating new ones. These tools must be suited to interpreting new processes and should not be guided by market forces.

The competitive factors of the city can be identified in three Cs (Carta Citation2007): Culture, Communication and Cooperation, all identifiable within the projects which will be presented. Culture is the primary factor of urban creativity. It indicates, in particular, cultural identity, which has its origins in history, and projects its image into the future. Communication – and so participation – is the ability of cities to inform and involve their inhabitants and various users in real time. Communication technologies have the potential to contribute to reducing travel, abating pollution, decentralising services and siting central services suitably. Cooperation is the ability of cities to explicitly accept the differences between inhabitants and between different parts of city, and to hold together the various components, in order to steer them towards communal objectives and results. Culture, communication and cooperation are therefore the resources which the creative city offers city administrators, planners and designers, the fundamental elements with which to generate innovation and quality.

The creative city is moving from a city where the creative class attracts new economies to cities where the creative class generates new economies, producing new identities and new geographies based on culture, arts, knowledge, communication and cooperation. The object is to nourish creativity within the city, to produce a creative class from inside rather than attract one from outside. In this framework, there is the creative milieu, intended as a place, which may correspond to the whole city or to a part thereof and which contains the characteristics necessary for generating a flow of creative ideas and innovations (e.g. the Cultural district created in Arabianranta and the creative industries in the Speicherstadt district of HafenCity).

3.2. Urban waterfront regeneration and creative clusters

Among the projects of urban transformation in development in Europe, the renewals of urban waterfronts are part of a series of complex creative operations currently under way in many cities (Sepe Citation2009). The main aim of these operations is to promote urban areas owing their competitiveness to distinctive local features with ‘symbol-city’ value, devoting special attention to opportunities to guide the evolution of urban systems (Florida Citation2002; Carta Citation2007). Indeed, the enhancement of urban waterfronts is increasingly becoming a starting point for implementing innovative urban redevelopment strategies which involve not only the waterfront but also the whole urban area (Guala Citation2002).

The most mature experiences of creative cities show us two types of creative clusters (Caroli Citation2004; Carta Citation2007). The first are the cultural clusters, which are created around activities such as fine arts, music, cinema, architectural works and design, and whose initiation is encouraged and planned by local administration. The second is the cluster of events, whose development stems from the organisation of great events or different kinds of recreational and cultural manifestations. Public support for the cultural cluster obtained in the start–up phase provides credibility for cultural investment to the project and allows visibility at the international level. In this case, the territorial policies must be devoted to creating the social and economic conditions to develop an urban environment that attracts actors interested in the cultural arena. At the same time, these policies should be devoted to promoting the cultural activities which already exist, organising events and cultural manifestations or building the infrastructure necessary to link them (Roche Citation2000). The Ciudad of Valencia, HafenCity in Hamburg, Lyon Confluence in Lyon, Bordeaux Les deux Rives in Bordeaux (Sepe Citation2010b; Martone & Sepe Citation2012), the Baltic of Newcastle, and the Albert Docks and the Tate of Liverpool are some examples, which, together with the City of Art, represent extensive cultural clusters. On the other hand, the clusters of events include the Expos (Sevilla 1992, Hannover 2000, Zaragoza 2008, etc..), the Venice Biennali, the European Capital of Culture (Helsinki, 2000; Marseille 2013, etc...) (Sepe Citation2010a) and the Olympic Games (Athens 2008, London Citation2012, etc...). Such gatherings are based on activities which are related to leisure and are bound together by the importance that the city gains in connection to these events. Indeed, organisation and realisation of the events concentrate firms, sponsors, users and tourists, which – in turn – influence the city brand. The manufacturing and services ‘machine’ which is built around the event is active throughout the year, while the event has a limited duration.

To enable a cluster of urban creativity, a system of governance must be created to support the network of players who cooperate with the objective both of enhancing the new resources as well as those already existing, and contributing to embedding the results in the territory. In this way, the danger is avoided that the positive effect which these operations have throughout the year could be lost at the conclusion of the event. Thus, the cluster should serve to transform the intangible energies connected to culture, art and leisure, into financial, productive and social resources both for the host city and the surrounding area, which may in turn transform them into structural resources (Landry Citation2000; Anholt Citation2007).

4. Methodology

The case studies reported in the paper are part of a broader research project entitled ‘The transformations of the contemporary city: analysis and design of the place identity for the sustainable enhancement of Cultural Heritage’, coordinated by the author, carried out in the context of the research programme ‘ Innovation and competitivity in the global economy’, in development by the Institute of Service Industry Research of the National Research Council.

The objective of the study is threefold: the research of new methodologies is aimed at identifying and designing the identity resources in emblematic areas of urban transformation; the identification of best practices of urban regeneration, mainly based on waterfront recovering and the creation of guide lines for sustainable urban regenerations. In particular, the study presented in this paper is related to the identification of the best practices of urban regeneration in Europe.

The research involved reading the specialised bibliography featuring regeneration projects, quantitative and qualitative secondary and primary qualitative data and using keywords to retrieve data not available in the works consulted. It also involved carrying out on-site inspections with photographic documentation, meeting participants in the process and gathering specific materials.

Each of the cases has been treated as a separate case (Yin Citation1984; Van Winden et al. Citation2012). After reviewing the scientific literature, this has been associated with quantitative and qualitative secondary data collected from: database concerning population, labour, economy, creative industries, tourism; the official websites of the respective regeneration programmes, from local magazine articles and press releases.

The primary qualitative data were collected through interviews with actors involved in the process and with users of the site in order to understand their satisfaction concerning the regeneration.

The cases were chosen with the purpose of obtaining a broad framework of new generation projects and identifying generalisable issues common to all cases (Van Winden et al. Citation2012). To this end, as explained below, the first organisation of the cases was carried out with respect to the start engine of the project: major cultural attractions, environmental policies, major events. The general themes which were considered common to all the programs include: urban projects – in turn subdivided in subthemes -, socio- economic regeneration and participation.

It was decided that the case studies concerning the whole research should focus on medium-sized cities in Europe where the regeneration process has meant redefining the identity not only of that particular place but of the city as a whole. This was the case of the Abandoibarra river in Bilbao, the new waterfront of Barcelona, the area between the old El Portillo station and the new Delicias station in Zaragoza, HafenCity in Hamburg – reported in the paper-, the new Liverpool waterfront, Arabianranta in Helsinki – reported in the paper, the old port in Genoa, Marseille Euromediterranée in Marseille, Lyon Confluence in Lyon, Bordeaux Les deux Rives in Bordeaux.

As a first step [in selecting the two case studies] the cases were divided up according to the project’s underlying motivation: great cultural poles, environmental policies, major events.

The cultural poles comprise buildings with a cultural use – museums, concert halls, aquariums, etc. – which become landmarks for the territory and are, in general, designed by internationally renowned architects. Such projects ensure that the part of the city undergoing regeneration gains in appeal and contribute to increasing the area’s economic value. Probably one of the most successful examples in Europe is the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, designed by Frank Gehry, which helped to transform Bilbao’s principal vocation from business to art. In the case of HafenCity in Hamburg, as we shall see in the next section, the Elbphilharmonie by Herzog & de Meuron is only one of the landmarks: there are a number of other initiatives which contribute to the area’s appeal and success.

Major events constitute another important factor in starting up a regeneration process, both for the financing they generate and for the international fame associated with the event. Many regeneration projects have begun from an international event: one emblematic example is Barcelona, where the 1992 Olympics were followed up by the 2004 Cultural Forum. Together they changed the face of the city’s coastal area, giving new vitality to various areas including the Ramblas. In many cases, the success of the event gives credibility to the local authorities and ensures subsequent funding. The case of Arabianranta in Helsinki, as we shall see, is linked to the event Helsinki: European cultural capital, with the associated themes of culture, innovation and multimedia resources, all factors of interest in the realisation of Arabianranta.

Environmental policies characterise many of the current regeneration projects in Europe and are practically a trait d’union. In some cases, however, attention to the environment and landscape becomes the prime feature, as in the French cases, where policies have long focused on the landscape also in social and economic terms. In this perspective, the cases of Bordeaux and Lyon are emblematic for their combination of urban and landscape projects to ensure a greater sustainability for the area in question and the city.

In all the case studies, materials have been gathered in order to verify urban projects, socio-economic regeneration and participation. The urban project is an important element in the process because it represents the objective physical transformation involved. The methodology used identifies the various phases, features, scheduled implementation times, objectives and measures adopted. The surface area of the operation and the designated uses in percentage terms – residential, public spaces, buildings for culture, vegetation – constitute an important factor in assessing the urban sustainability. It is useful to collect plans on the territorial scale which lie behind the projects, guidelines and strategic orientations. The investigation also seeks to identify the issues encountered and the state of advancement. Furthermore, the information on the urban projects can be extended by analysing three aspects of the area surrounding the city: geography, historical evolution, projected image and new identity.

The phases of the urban projects are closely linked to their financing and socio-economic regeneration. The public and private financing received for each project phase is registered, together with the institutions involved and the company set up to oversee the investments. In general, this company coincides with the institution that creates and manages the web portal containing the principal information on the project (Bilbao Ria 2000; HafenCity Hamburg, etc.). In addition, the research identifies the population sizes (original and planned) for the area, the number of jobs (original and planned), number of new residences, social policies put in place (rent subsidies, use of local knowhow in constructing districts, as in the case of Arabianranta), sectorial employment, new creative industries, cultural and creative districts.

Participation is another fundamental factor investigated. For the transformation process to be achieved with success, consultation with the various categories of stakeholders must be held from the outset and at each stage. The investigation looked at ad hoc or national legislation, preliminary and mid-term consultations, listening modalities, results of consultations and contribution to the construction process, newsletters, conmunication modalities, any ad hoc logos, etc.

While it was easy to acquire information about the initial phases, for the progress of a project it was necessary to rely on newsletters and websites. In some cases, such as Arabianranta, participation was the key element, and indeed the objective of the transformation project, as will be seen below. Similarly, the idea of Hamburg maritime city came from the local administration and could count from the outset on the consensus of the population. Some countries, such as France, have put in place legislation which regulates the whole listening process and safeguards its application.

5. The case studies

5.1. The Arabianranta Project in Helsinki

5.1.1. The start engines

The opportunity provided by an European Capital of Culture is to enhance, develop or transform its own cultural identity and gain international visibility. The proposed Arabianranta regeneration, in the framework of the cluster of events, although begun at least 10 years before, experienced most visibility in 2000 and beyond on the occasion of Helsinki European Capital of Culture. Helsinki is a city of about 600,000 inhabitants and the capital of Finland. In 2000, in addition to being designated European Capital of Culture, it also celebrated its 450th anniversary. The specific theme for the European City of Culture for 1998–2000 focused on the impact of society on urban development, while the topics for the anniversary were knowledge, technology and future. In the late 1990s, Helsinki strove to become a European model for the city, in terms of variety, quality and efficiency of services.

The project for the area of Arabianranta, based on integrating environmental regeneration of the waterfront, the creation of mixed-use housing and of a cluster for the arts within a ‘third-generation park’, can be considered as part of the broader objective of Helsinki for innovation and experimentation. The elements that inspired and guided the whole operation are based on the identity and nature of the place, social diversity, creativity and innovation.

5.1.2. History and environment in the urban transformation

The origin of the Arabianranta area lies in the Bronze and Iron Age. The name Arabia or rather ‘Arabian ja Kaanaan maa’ (the land of Arabia and Canaan) was given at a time – presumably before the eighteenth century –, when the area was considered far from the city centre.

The Arabianranta project covers an area of 305,000 m2 originally occupied by the Arabia ceramics factory founded in 1874. Indeed, the beginning of industrial activity in Helsinki is essentially related to Arabianranta, where in the 1800s the first water-power station and water refinery was built close to the Vanhakapunki torrent (www. www.arabianranta.fi).

The project area is built around a park along the shoreline (), which stretches from Sornainen to the mouth of the Vantaanjoki river (Somervuo Citation2007; Camerata Citation2008). The Department of Urban Planning of the City of Helsinki started planning the area in the 1990s. The design is by Maisemasuunnittelu Hemgård landscape planning office and the estimated costs of construction are 21€/m. The plan was designed in agreement with the municipal administration by Pekka Pakkala and Mikael Sundman. Construction started in 2000, with a completion date in 2013.

Figure 1. Arabianranta, residential blocks (from: http://www.arabianranta.fi).

The authors designed the area as a set of residential blocks around courtyards, with one side open towards the coastal park in order to allow the building to be wholly integrated with the landscape. To meet the concerns of the local community – which is one of the main objectives of the project – about a sustainable impact of the interventions, the designers decided to make a 1:1 scale model of the corners of buildings and place them in the area in order to study the effects in loco and to collect suggestions from residents.

The urban planning tradition in Finland mainly plays upon differences, an aspect that Sundman wished to take into particular account and consolidate. Realisation of the common courts was therefore conceived as a set of independent lots which, remaining the property of Arabian Palvelu Oy, could not be privatised by the construction companies. Suitable public spaces were created in order to improve the liveability of the inhabitants and visitors alike.

An element to be stressed is that the apartments targeted users and uses of various kinds, not only flats to be rented and sold at market prices, but also homes sold under the Hitas system, which guarantees – on the basis of a preliminary agreement between the City and the builder – the final sale price of houses built on public land. Furthermore, in Arabianranta there are loft buildings, Plus Koti (Plus Home) homes for groups with special needs such as Loppukiri (community housing for active elderly people), Käpytikka (residence for mentally disabled juveniles) and MS-Talo (MS House) (for people with MS) (www. www.arabianranta.fi).

5.1.3. Innovation and creativity in the Cultural District

The themes of knowledge, technology and the future established by the Helsinki European Capital of Culture have been achieved by building, along with other infrastructures, an experimental fibre-optic broadband network. The Art and Design City Helsinki Ltd company was founded to manage the project. The network is designed to allow the construction of low-cost connection services to residents, cultural institutions and businesses.

To ensure proper implementation of this operation, guidelines have been drawn up by the Art and Design City Helsinki Oy – ADC – and the Department of Public Works to install information technology in residential buildings, and have been included in the assessment criteria for the assignment of lots to builders.

Another factor of interest is the construction of the Cultural District Kumpula-Arabianranta that includes in itself all the strengths of the project. The construction of this district is in continuity with the creation of science parks such as Otaniemi, Oulu, Tampere and Viikki in recent years in Finland. The purpose of these parks is to attract capital to companies wishing to build their headquarters in areas close to the production of know-how, and offering opportunities for research and work as well as residences and services.

The Arabianranta district contains the University of Art and Design, the Arcada Polytechnic of Swedish language, the Polytechnic Stadia with the Pop and Jazz Conservatory and the Aralis library, and the Kumpula campus. The district is based on an image of culture and innovation well grafted onto the historical memory of the site’s industrial past. This is evoked by the old factory chimney () familiar to customers of the Iittala factory shop that still produces pottery under the Arabia trademark.

Figure 2. The Arabian old factory chimney (from: http://www.arabianranta.fi).

To promote in an integrated manner the presence of art within the site, the plan envisages that 1–2% of construction costs are reserved for the creation of art works to be included in the district during the construction process. An Artistic Director coordinates the integration of artists, architects and engineers for the creation of sculptures, installations, ceramics and photographs in the residential blocks ().

Figure 3. Arabianranta, art works in the district (from: http://www.arabianranta.fi).

5.1.4. The socio-economic regeneration and participation

As the description of the case has shown, the cultural identity of the neighbourhood has not been imposed from the top nor has it developed as a spontaneous process. The Administration has started to work from the place and its history, specific planning rules have been studied, and appropriate policies have been adopted which have been helpful as well as acting as an incentive to creativity (Camerata Citation2008). In 2006, 50% of homes were new and from that date all dwellings were equipped with an Ethernet network for free. In Arabianranta live most of the 7000 workers, 10,000 residents and 6000 students, which were foreseen in 2013, with the objective to realise a community which is as mixed and inclusive as possible, able to combine Finish and foreign students, workers, artists, researchers and residents with different social backgrounds (Vilhena Da Cunha & Selada Citation2009).

A Social Impact Assessment was carried out by the Helsinki city planning department for Arabianranta. The SIA report analyses different factors, including the social-demography, the social status and the place identity before and after the project (). As reported by Sairinen and Kumpulainen (Citation2006), ‘although the area has historically had a fairly low social status as a working class district, the status has improved slowly since the 1970s. Gentrification has been especially strong in the idyllic wooden house areas. (...) The main social objectives in building Arabianranta were to maintain and create a versatile social and housing structure, to create a positive image for the whole area, to cater for weak population groups and to provide adequate services’. Furthermore, although ‘an emphasis on private housing could have led to high property prices due to the closeness of both the city centre and the sea, with the construction of different kinds of housing, people with different means have the possibility to live in the area (...) and all residential buildings, city-subsidized or private, have the same high quality’.

Table 1. The social dimensions of urban waterfront planning (from: Sairinen & Kumpulainen Citation2006).

Considerable attention has been paid to communication and the care and enjoyment of public spaces, conceived not only as places for physical interaction but also for virtual communication. One of the clearest manifestations of this operation, communication and integration between the plan and the residents is the Helsinki Virtual Village, the local web managed by the ADC, which contains, thanks to a 10 Mb connection – included in the cost of building (condominio) –, an open area and an intranet area which is managed by real estate companies.

Community members can access an ‘ubiquitous’ system using cell phones, digital television and personal computers. The network is realised with the collaboration between ITC companies including Nokia, Ericsson, Matsushita, Psion, Motorola and Sonera. Most of the residents are newcomers to the area and are interested in meeting and building social networks with the other neighbourhoods (Shaw Citation2001).

The presence of art in the form of entertainment and viewed as a form of neighbourhood bonding is also ensured through events of applied theatre organised by the Faculty of Culture of Stadia Polytechnic. These events aim to raise awareness on common problems to the residents and how to face them, and the opportunities to influence social policy (Ilmonen & Kunzmann Citation2007).

5.2. The Hafencity Project in Hamburg

5.2.1. The influence of history and the start engine

History has played a fundamental role in the planning of HafenCity district. Although only a partial reconversion of the harbour warehouses is envisaged, the project is restoring the maritime vocation of the historical city and is strictly connected with the city. Hamburg is Germany’s main port and one of the major European ports. In the first half of the thirteenth century, the town joined the Hanseatic League and Hamburg played a key role in the League. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the South American states became important commercial partners of Hamburg’s shipping companies and merchants. The harbour’s cargo volume increased until the construction of the city’s first modern port basin, Sandtorhafen, became indispensable, built between 1863 and 1866. In the course of the nineteenth century, the port evolved into the current HafenCity. Other port basins were built in the wake of Sandtorhafen, namely, Grasbrookhafen (1872–81), Magdeburger Hafen (1872), Brooktorhafen (1880) and Baakenhafen (1887). To protect the port structures from flooding, the low marshes were gradually raised to 4–5 m above sea level. Great Fires and the World Wars caused many episodes of destruction in the port. Reconstruction began after 1945, and this entailed a significant growth in freight traffic.

Traces of the history are present in different places of the Hafencity area. The Speicherstadt warehouse () plays an important role, acting as an entrance and a joining element. With its impressive brick facade – left almost unchanged – the old warehouse is listed as a historic monument and is due to become a Unesco World Heritage Site in 2014. The Speicherstadt now has different purposes. Not only museums and traditional goods storage, but also new functions were established to serve as a bridge between the old and the renovated image. These include those involved in the art and culture sectors as well as multimedia agencies and creative business.

The old harbour basins with their buildings represent for HafenCity another important element in the recovering of its place identity. The quay walls and the tracts of water constitute a place of attraction for both locals and visitors. The historical buildings which were retained, including the Speicherstadt as a whole, the Elbphilharmonie Concert Hall on the rooftop of Kaispeicher A, the International Maritime Museum in Kaispeicher B and the old Port Authority building, have become the landmarks of HafenCity.

The tangible identity has been enhanced together with the immaterial heritage of traditions which are being revived and reinterpreted in various ways, as in the case of the Sandtorhafen basin, where traditional steamships, sailing ships and cranes have been reconstructed (HafenCity Hamburg Citation2010).

5.2.2. The process of urban transformation: mixed use, public spaces and sustainability

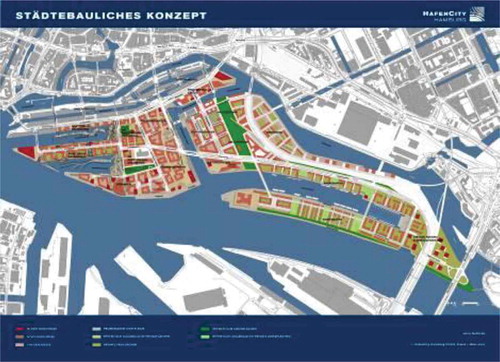

The Hafencity project was approved in 1998 after an idea competition that saw the victory of eight studies, one for each of eight macro-areas singled out. The aim of the project is to allow the city centre to expand and, at the same time, integrate with the port beyond the Elbe, which for decades has been increasingly relegated in the southernmost part of the town. The 155 hectares project area is subdivided into eight main areas ().

The land which is available for development of housing residences is subject to competitive procedures. The offer price is fixed before the start of the tender process. After the decision for a bidder, architectural competitions take place (Clark et al. Citation2010).

Figure 5. Development status diagram as of October 2013 (Illustration: Michael KorolSource: HafenCity Hamburg GmbH).

Three important aspects are planned: mixed use, public spaces and sustainability ().

Table 2. Key performance indicators for HafenCity Hamburg GmbH since project inception (from: Clark Huxley Mountford, Citation2010).

Mixed use is achieved by devoting 3% of the available land area to advertisement, 8% to culture, science and education, 33% to habitation (about 5500 apartments for 12,000 people are planned) and 56% to services, tertiary and tourism. Thirty five percent of the surface will be occupied by buildings, 25% by streets and transportation infrastructure and 36% by public spaces and private spaces accessible to the public. Only 4% of private spaces will not be accessible to the public (HafenCity Hamburg Citation2004, Citation2006, Citation2010; Hamburg Port Authority Citation2006; Tzortzis Citation2006; Falk Citation2008; Cavallari Citation2009; www.waterfrontcommunitiesproject.org). Access to private spaces, especially where the most friction may occur between visitors, residents and people who work in the area, has been defined by an agreement guaranteeing and regulating their use by the public. Except for the promenades, the streets and parks are between 7.50 and 8.00 m above the water level. This has created a new topography for the area, one that enhances its ‘port ambiance’ (Breckner Citation2009).

The starting point in the building of HafenCity was the Am Sandtorkai quarter, where the first residential and office buildings were erected. The choice of this neighbourhood was determined by its position between the Speicherstadt warehouse district and Sandtorhafen, the nineteenth-century port basin. The buildings erected here are isolated from one another to provide them with an exclusive view of the city centre and the harbour. The only structures extending beyond the waterfront and the partially roofed promenade are the moored barges. The new buildings, erected only a few blocks away from the brick warehouses – which still house the stores of Oriental carpet merchants, as they have ever since the nineteenth century –, were planned so as to harmonise with the historical buildings of the Speicherstadt.

On the other side of the Sandtorhafen is the Dalmannkai quarter, presently nearing completion. A total of 1300 people have already moved here. Dalmannkai houses the soon to be completed Elbphilarmonie Concert Hall, the result of an industrial reconversion project carried out by Herzog & de Meuron. The structure, shaped like a boat sail, will house a concert hall, a hotel, a conference centre, a delicatessen and several residential units.

The new Dalmannkai quarter is the most heterogeneous area of all of HafenCity, and has become a meeting point for residents, workers and visitors. A broad range of residential units, all facing the water, but differing in size, location and architecture, meet different needs. They range from luxury apartments – including, for example, some designed by Philippe Stark – to middle-priced ones. There are private apartments for sale at prices from 3000 € to 3800 € per square meter as well as reasonably priced ones available for rent. This variety is the result of an offer policy based on small-scale competitions to keep planning quality high.

Sandtopark, situated between Sandttorhafen and Überseequartier, is an integral part of the plan for the open spaces west of HafenCity. It was planned by the EMBT studio in Barcelona with materials and features matching those of the surrounding spaces and buildings, contributing to the project’s sustainability. The EMBT studio also planned Sandtopark’s two squares, the Magellan Terraces () at the end of Sandtorhafen and the Marco Polo Terraces at the end of Grasbrookhafen. Here, promenades and pedestrian paths run at different heights, alternating with green spaces and open spaces providing access to the wharves and the water (Breckner Citation2009).

On the south side of the area, at Elbtorquartier, is building Kaispeicher B, the oldest warehouse of HafenCity, now converted into a museum of navigation. A university for the study of architecture and the development of metropolises, the HafenCity Universität für Baukunst und Metropolenentwicklung, is currently being planned on the banks of the Elbe running along the quarter.

The core of HafenCity is the Überseequartier. This is a mixed function neighbourhood extending over 7.9 hectares. A projected 40,000 visitors will eventually come here daily through the new cruise terminal located on the neighbourhood’s waterfront. The Überseequartier extends parallel to Magdeburger Hafen. It is planned to develop towards the Elbe, connecting with the development in course elsewhere along the banks of the river. The objective is to make this part of the city people-friendly and connected to the historical city, a place where one can live, shop and have access to recreational and cultural opportunities. To this end, very detailed guidelines were set regarding buildings and their uses, and space distribution.

Finally, many buildings, including Katharinenschule primary school, the Spiegel group publishing building, the HafenCity University building, the Commercial Centre building and the NIDUS joint venture building, obtained the Ecolabel certification contributing to the sustainability of interventions.

5.2.3. The socio-economic regeneration and participation process

The socio-economic and participation processes are closely interwoven in HafenCity. The implementation of the master plan for HafenCity was preceded by a declaration of the strategic interest of the waterfront for the development of the Hamburg community.

To complement the master plan, a number of detail plans were drawn up, including a transport plan, a land-use plan, a plan for green areas and an evacuation plan in case of flooding.

The first stage focused on water as the element around which the town’s economy was intended to develop. This was followed by a stage when, as the shipyards declined, the city began to gravitate towards the opposite side – that is, towards the port, the waterfront and the river – and expand towards new sectors. In the subsequent stage, the growth of tourism played a fundamental role in the formulation of strategies to redefine the port system. Finally, there was a communication stage, in which a public debate was launched on the subject of the redesigning of the port. The local community was involved through exhibitions, lectures, competitions and publications.

This approaches to citizen participation include: ‘active involvement of citizens, authorities and different committees during the development process with the purpose of this was to generate confidence, political involvement and to implement the notion of self-help and self-responsibility; use of the already established Advisory Board for Urban development, which includes representatives of both formally constituted groups and institutions and informal, as well as ad hoc groups from different neighbourhoods, and has been working since 1994; setting up of an onsite office mechanism for close cooperation among all levels of government involved in the strategic development programme, including the Senate of Hamburg; organization of national and international conferences and workshops with a variety of focus themes’ (Smith & Garcia Ferrari Citation2012).

In the present stage, Hamburg is promoting an urban development based on new projects and investments aiming at high urban and architectural quality. The ongoing projects strive to combine new buildings with architectural quality, urban and environmental sustainability and marketing, communication and consensus.

The building of HafenCity is projected to increase the surface of the original Medieval city by 40% in 20 years. The 155 hectares of the Medieval city’s overall area comprise one third water and two thirds land. It is expected that 12,000 of the city’s residents will have moved to HafenCity by 2020. The area’s cultural structures are projected to eventually draw about 3 million visitors a year. The project – whose entire costs are roughly €7 billion – is expected to stimulate the creation of 20,000 new jobs in the service sector (Carta Citation2007). The investment from the public sector – about €1.53 billion – is being matched by that from the private sector (about €5.5 billion). Many multi-nationals are relocating their company to HafenCity using, beyond new efficient office spaces, specific high HafenCity standards such as sustainability and public spaces to create positive externalities (Clark et al. Citation2010).

The whole operation is coordinated by a limited liability private company, HafenCity Hamburg GmbH, owned by the Free Hanseatic City of Hamburg, which manages relations between the public and the private sector. The company’s principal functions are making available, developing, commercialising and selling the land. Furthermore, the company is responsible for communication, public relations, event management, advertising and the promotion of artistic events on the site, carried out also through a web site which documents the different stages and activities of the project.

Furthermore, as affirmed by the HafenCity Hamburg GmbH CEO Jürgen Bruns-Berentelg,‘Urban quality is characterised not just by physical quality, appeal or attractiveness of the place, but also inclusivity and diversity and its sustainability and mix. It should be open and accessible to lots of people’ (Clark et al. Citation2010) ().

Table 3. Social institutions and networks from www.hafencity.com/in (Clark et al. Citation2010).

The construction of a suitable website has represented a necessary step in order to allow the participation of the project in international networking.

6. Conclusions

This paper has illustrated the main factors which condition the creative city and two emblematic case studies of creative urban regeneration, namely Helsinki contextualised in the cluster of events and Hamburg in relation to the cultural clusters. In particular, the two case studies are related to the regeneration of urban waterfronts, which are increasingly becoming a starting point for implementing creative urban redevelopment strategies.

The restoration of an urban waterfront requires the integration of a complex system of actors, norms, processes and plans at different scales, and an equally complex time planning. If this is not combined with a strong and clear strategic vision of the city, and, especially, a shared one – at all levels –, one runs the risk of achieving only partial and unsatisfactory results that will not last through time. An important factor in a waterfront area is the diversification of activities, which need to be integrated into urban life cycles. The area must house public buildings such as universities, museums, etc. This allows its continuous use and full integration into the city, with a consequent increase of satisfaction for residents, visitors and tourists.

In the case of Arabianranta, many ingredients were used that seem to have had positive effects, from controlling the pressure of the real estate market to the promotion of activities not focused solely on consumption, from the involvement of architects and artists to the inclusion of local socio-cultural capital diversity. The balanced mix of historical memory and technological innovation seem to have already attracted many residents and students and created the workplaces, which were foreseen by the project.

Important factors of success are provided by creating the identity of the neighbourhood started from the place and its history, constructing the most suitable urban policies and strategies, and involving students and residents in many ways and occasions such as the Helsinki virtual village portal.

Arabianranta, constituting a new relevant urban pole and promoting an urban space of quality, developed a new centrality in Helsinki, far from the ‘suburb feeling’. Furthermore, enhanced the digital connectivity of the area with new broadband solutions, associated with digital platform in each building, it allowed the development of sense of community both in the building and in the whole area. A new figure of ‘e-moderator’ has emerged with a function of ‘broker and gatekeeper of sociability’, facilitating the development of Living Lab experiments and allowing new activities in the area which in turn lead to social innovation for Arabianranta. And also from a social point of view, this is a case of successful regeneration as regards the integrated planning: ‘it hosts a mix of social, ethnical and age groups in different housing schemes integrated in a location of growing charisma’. The process of developing of the area have helped the capacity of local government to institutionalise cooperation and integration between different kinds of partnerships such as developers, universities, firms and transversal departments such as planning, transport and economic development departments. Finally, Arabianranta ‘showed the need to develop communication plans and the importance of establishing dedicated entities and public-private structures to monitor the development of large projects overtime (ADC). Many of the lessons of Arabianranta are nowadays being used and considered in new thematic area based developments in other city locations’ (Van Winden et al. Citation2012).

In the case of HafenCity, in order to restore the maritime identity and determine the most adequate strategies for urban renewal, the planners’ starting point was the place itself and its history. The theme of water is central for the whole waterfront project and the economy has developed around it to create new productive sectors. The citizens have been involved in the project ever since its earliest stages, to make sure that this new piece of the city would fulfil the wishes of the collectivity. Many cultural activities are being organised the whole year round to create a feeling of community among residents as well as attract visitors (Richards & Wilson Citation2006; Kagan & Hahn Citation2010).

HafenCity has been catalysing the interest of the locals, many of whom have already moved there from other areas in Hamburg, and attracting the curiosity of tourists, who come to see the new planned areas. It is still early, however, to make a final assessment of the success of the operation and determine whether the right balance has been struck between economic interest, social well-being and respect for the area’s historical identity.

An important role in the project is the communication and marketing process which ensured the establishment of the regional and international awareness of the investment opportunities in HafenCity. Furthermore, the sustainability of the interventions is also certified by Ecolabel which were obtained for many buildings and surrounding spaces and by the ecological system of mobility. The introduction of this certificate has also enhanced the attractiveness of the project to investors.

Another important factor of success is represented by the ‘development sequencing’: ‘HafenCity was developed as a completely new urban district on the basis of a concept which delivered integrated urban quarters one-by-one in a strongly time-wise and co-ordinated process. This means that private investors can rely on their development being situated in an integrated urban environment and functioning quarter very soon after its completion’ (Clark et al. Citation2010). HafenCity Hamburg GmbH is playing a fundamental role in this sense, through the provision of public investments in infrastructures of mobility and public space which guarantee high quality.

Furthermore, private investments have operated in a ‘risk-aware’ manner allowing in this present period of financial crisis that the project’s business model remains solid through some measures: ‘the project is financed and supported by a diverse range of partners; the development is divided into small segments which can be developed sequentially when finance is available; and the development is mixed use’ (Clark et al. Citation2010).

For the time being, what we can say is that the area is proving attractive and is recreating a strong bond between the city and its waterfront and harbour, partly thanks to architectures evoking ship shapes, the ferries crossing HafenCity to show the new skyline to visitors, the promenades on the jetties of Sandtorhafen with its historical sailing ships and the residential buildings and entertainment facilities overlooking the harbour. Furthermore, the Speicherstadt district is due to be listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014.

As stressed in the more recent studies on the subject, planners should be aware that urban development based merely on physical and material aspects, disregarding intangible culture, threatens to produce repetitive places that fall an easy prey to globalisation. To support local identities and enhance the distinctiveness of a place, the accent must be placed on art and culture. The efforts to complete the project areas should thus be based on integrated strategies addressing different aspects of the city at different levels. For a successful long-term urban and cultural renewal benefiting all who frequent the area, it is important to constantly involve the population and consolidate place identity, while taking care to ensure the economic, social and environmental sustainability of the project.

In the two cases, it is important during the period of project completion not to place too much stress on tourist development where the term ‘cultural’ is an instrument rather than a quality; for sustainable development, a real engine of change, the ‘cultural’ element must offer quality to tourism not vice versa (Smith Citation2007). The more value is given to the local cultural peculiarities – such as cultural heritage and place identity – the more the operation of urban regeneration may be embedded within the local fabric and be attractive for residents and visitors.

Finally, as Landry (Citation2006, p.10) affirms: ‘To survive well, bigger cities must play on varied stages – from immediately local, through the regional and national, to the widest global platform. These mixed targets, goals and audiences each demand something different. Often they pull and stretch in diverging directions. (...) Working on different scales and complexity is hard: the challenge is to coalesce, align and unify this diversity so the resulting city feels coherent and can operate consistently’.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marichela Sepe

Marichela Sepe received the Laurea degree in Architecture and the Specialization School degree in Urban Design from the University of Naples in 1991 and 1996, respectively. Since 1995 she has been with the Italian National Research Council in Naples (www.cnr.it), where she has been a researcher since 2001. Since 2009 she has been with the Institute of Service Industry Research of Naples of the Italian National Research Council (www.irat.cnr.it). Since 2003, she has also been with the Department of Architecture of the University of Naples (www.unina.it). She is in the Research Doctorate Committee in Urban Design and Planning and Contract Professor of the University of Naples Federico II. In 2000 she was a visiting scholar at the Laboratorie Jardins, Paysages, Territories of the Ecole d’Architecture Paris La Villette, and in 2004 at the Department of Urban Studies and Planning of MIT, Cambridge. In 2013 she was a visiting professor at the Peking University and held lectures in Peking University, Wuhan University and Xi’an Jiaotong University. Her research interests include the following: urban landscape analysis and planning; urban design; territorial and environmental planning; creative urban regeneration. On these topics, she has published several national and international journal articles, conference papers, books and book chapters. Dr Sepe is in the Steering Committee of Inu – Urban Planning Italian National Institute, and member of the Urban Design Group, DO.CO.MO.MO and EURA.

References

- Anholt S. 2007. Competitive identity: the new brand management for nations, cities and regions. Houndmills. New York (NY): Palgrave MacMillan.

- Anholt S. 2011. The Anholt City Brands Index 2011 general report [Internet]. [cited 2012 May]. Available from: www.business.nsw.gov.au

- Bagwell S. 2008. Creative clusters and city growth. Creative Indus J. 1:31–46.

- Breckner I. 2009. Culture nello spazio pubblico: Hafencity ad Amburgo. Urbanistica. 139:98–101.

- Camerata F. 2008. Il quartiere creativo di Arabianranta; Rigenerazione urbana, cultura e identità. Urbanistica Informazioni. 221–222.

- Caroli MG, editor. 2004. I cluster urbani, Modelli internazionali, dinamiche economiche, politiche di sviluppo. Milano: Il sole 24ore Edizioni.

- Carta M. 2004. Next city: culture city. Roma: Meltemi.

- Carta M. 2007. Creative city. Barcelona: LISt.

- Carter E. Donald J. Squires J, editors. 1993. Space & place, theories of identity and place. London (UK): Lawrence & Wishart.

- Castells M. 1997. The power of identity. Malden: Blackwell.

- Cavallari U. 2008–2009. Amburgo: il futuro della città incontra il fiume. The Plan. 31:132–142.

- Clark G, Huxley J, Mountford D. 2010. Organising local economic development: the role of development agencies and companies. Paris: OECD.

- Comunian R, Sacco PL. 2006. ‘NewcastleGateshead: riqualificazione urbana e limiti della città creativa’, Working paper no. 2, Venezia: Università Iuav di Venezia.

- Evans G. 2001. Cultural planning: an urban Renaissance? London (UK): Routledge.

- Falk J. 2008. Vivere e lavorare sull’acqua: la HafenCity di Amburgo – Dossier sull’architettura [Internet], l’urbanistica, l’evoluzione e la ricerca urbana, Goethe-Institute [cited 2012 May 21]. Available from: www.goethe.de

- Ferilli G, Pedrini S. 2007. ‘Il distretto culturale evoluto alla base dello sviluppo sostenibile del territorio’. Pre Proc. of XII International Conference Volontà, libertà e necessità nella creazione del mosaico paesistico-culturale. Cividale del Friuli – UD, 25–26 Oct 2007.

- Florida R. 2002. The rise of the creative class. And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York (NY): Basic Books.

- Florida R. 2005. Cities and the creative class. London: Routledge.

- Gospodini A. 2004. Urban space morphology and place-identity in European cities; built heritage and innovative design. J Urban Des. 9:225–248.

- Graham B, editor. 1998. Modern Europe – place, culture, identity. London (UK): Arnold.

- Guala C. 2002. Per Una Tipologia Dei Mega Eventi. Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana. 12:743–754.

- Hague C, Jenkins P, editors. 2005. Place identity, participation and planning. Abingdon (UK): Routledge.

- Hall P. 1998. Cities and civilization: culture, innovation and urban order. London (UK): Weidenfeld & Wishart.

- HafenCity Hamburg. 2004. Focus on – the Überseequartier: pulsating centre on the Elbe River, March 2004 [Internet]. [cited 2012 May]. Available from: http://www.hafencity.com

- HafenCity Hamburg. 2006. The masterplan [Internet]. [cited 2012 May]. Available from: www.hafencity.com

- HafenCity Hamburg. 2010. Projects – insights in the current developments, Mar 2010 [Internet]. [cited 2012 May]. Available from: http://www.hafencity.com

- Hamburg Port Authority. 2006. Focus of dynamic growth markets, free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg [Internet]. [cited 2012 May]. Available from: http://www.hamburg-port-authority.de

- Ilmonen M, Kunzmann K. 2007. Culture, creativity and urban regeneration. In: Kangasoja J, Schulman H, editors. Arabianranta. Rethinking urban living. Helsinki: Helsingin City of Urban Facts.

- Kagan S, Hahn J. 2010. Creative cities and (un)sustainability: from creative class to sustainable creative cities. Culture and Local Governance/Culture et gouvernance locale. 3:1–2.

- Keivani R. 2010. A review of the main challenges to urban sustainability. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 1:5–16.

- Keivani R, Mattingly M. 2007. The interface of globalisation and peripheral land in developing countries: implications for local economic development and urban governance. Int J Urban Regional Res. 31:459–474.

- Landry C. 2000. The creative city: a toolkit for urban innovators. London (UK): Earthscan.

- Landry C. 2006. The art of city making. London (UK): Earthscan.

- Landry C. 2008. The creative city: its origins and futures. Urban Des J. 106:14–15.

- Martone A, Sepe M. 2012. Creativity, urban regeneration and sustainability: the Bordeaux case study. J Urban Regen Renewal. 5:164–183.

- Massey D, Jess P, editors. 1995. A place in the world? Place, cultures and globalization. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press.

- Mommaas H. 2004. Cultural clusters and the post-industrial city: towards the remapping of urban cultural policy. Urban Stud. 4:507–532.

- Neil WJV. 2004. Urban planning and cultural identity. New York (NY): Routledge.

- Nijkamp P, Perrels AH. 1994. Sustainable cities in Europe. London (UK): Earthscan.

- Richards G, editor. 1996. Cultural tourism in Europe. Wallingford (UK): Cabi.

- Richards G, Wilson J. 2006. Developing creativity in tourist experiences: a solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tourism Manag. 27:1209–1223.

- Roche M. 2000. Mega events and modernity. London (UK): Routledge Press.

- Roodhouse S. 2006. Cultural quarters, principles and practices. London (UK): Intellect.

- Sacco PL, Tavano Blessi G. 2005. Distretto culturale e aree urbane. Economia della cultura. 14:153–166.

- Sairinen R, Kumpulainen S. 2006. Assessing social impacts in urban waterfront regeneration. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26:120–135.

- Scott A. 2000. The cultural economies of cities. London (UK): Sage.

- Scott AJ. 2006. Creative cities: conceptual issues and policy questions. J Urban Aff. 28:1–17.

- Sepe M. 2004. Cultural resources and sustainability of development in the CSF 2000–2006. Architek Urban. 38:25–34.

- Sepe M. 2006. Distretti culturali e PIT: il caso studio nel territorio del Progetto Integrato Paestum-Velia. Archivio di Studi Urbani e regionali. 87:35–51.

- Sepe M. 2009. Creative urban regeneration between innovation, identity and sustainability. Int J Sustainable Dev. 12:144–159.

- Sepe M. 2010a. Urban policies, place identity and creative regeneration: the Arabianranta case study. Proceedings of 2010 14th international Planning History Society conference; 2010 Jul 12–15, Istanbul

- Sepe M. 2010b. Sustainable urban transformations in the contemporary city: a case of creative regeneration. Proceedings of inhabiting the future, Napoli, 2010 Dec 13–14. Napoli: Clean.

- Sepe M. 2013a. Places and perceptions in contemporary city, Editorial. Urban Des Int. 18:111–113.

- Sepe M. 2013b. Planning the city: mapping place identity. London (UK): Routledge.

- Shaw W. 2001. In Helsinki virtual village. Made in Arabianranta. New York (NY): Wired Magazine.

- Smith M, editor. 2007. Tourism, culture and regeneration. Cambridge (MA): Cabi.

- Smith H, Garcia Ferrari MS. 2012. Waterfront regeneration. Experiences in city-building. London (UK): Routledge.

- Somervuo H. 2007. Cooperation brings success. In: Kangasoja J, Schulman H, editors. Arabianranta. Rethinking urban living. Helsinki: City of Urban Facts.

- Tzortzis A. 2006. Hamburg’s harbor of hope – Ristrutturazione urbanistica a funzioni miste in aree portuali. HafenCity: Deutsche Welle, Industrial Chic. Reconverting Spaces.

- UNESCO. 2006. Tourism, culture and sustainable development. Paris: UNESCO.

- Van Winden W, de Carvalho L, Van Tuijl E, Van Haaren J, Van den Berg L. 2012. Creating knowledge locations in cities: innovation and integration challenges. London (UK): Routledge.

- Vilhena Da Cunha I, Selada C. 2009. Creative urban regeneration: the case of innovation hubs. Int J Innovat Regional Dev. 1:371–386.

- Yin RK. 1984. Case study research: design and methods. Newbury Park (CA): Sage.

- Zukin S. 1995. The culture of cities. Cambridge (MA): Blackwell.