Abstract

The issue of geographical scale in implementing sustainable urban development has not received much attention in sustainability research. Is it possible to locate sustainability efforts to one part of the city and by creating a spatial imbalance expect that these efforts gradually spread to the rest of the city? For this purpose this paper proposes a model of unbalanced sustainable development. The model is based on an old theory in development economics, namely unbalanced growth. The author contends that such a model should be suitable for many cities where the opportunities for more comprehensive city-wide sustainable development strategies are limited.

Introduction

With an ever-increasing share of the world’s population living in urban areas, the role of cities is crucial in responding to global environmental changes. In reality the situation is such that cities seem to continue displacing themselves environmentally. In the current competition for international investments, cities have been described as growth machines and as a crucial premise for a nation’s successful participation in the global competition for rapid economic growth (Molotch Citation1976). Current transference of manufacturing industries to the cities in the less developed world is taking place without paying adequate attention to ecological consequences. The most draconic example is the historically unparalleled industrialisation in China which entails enormous environmental costs.

As a result of immense increases in per capita energy and material consumption and growing dependencies on trade, the ecological locations of cities no longer coincide with their geographical locations. Cities as growth machines prosper by appropriating the carrying capacity of an area vastly larger than the space they physically occupy. Their consumption of nature, defined in terms of their ecological footprint, is quite substantial (see Wackernagel & Rees Citation1996; Rees Citation2004). As global urbanisation gathers pace, and through increasing commercial trade, cities, regardless of their location, appropriate the ecological output and life support functions of distant regions all over the world.

Under these circumstances, we require imaginative approaches in order to disentangle cities that are snarled in an increasingly faster roundabout of economic competition so as to enable them to get away from their resources-consuming practices. A major issue at hand is how to achieve the operation of policies towards more sustainable development across a whole city region?

Many past initiatives for more sustainable urban development put emphasis on engendering greater environmental responsibility on behalf of the people. Greater environmental responsibility is one constituent part of the solution to current day urban ecological problems. However, structural factors that engender and interact with individual behaviour are equally important. Placing responsibility on the individual deflects attention away from the broader economic and social factors that encourage lifestyles harmful for the environment (Jackson Citation2005).

Urban sustainability initiatives can be very broadly classified in three categories:

specific policy measures, e.g. energy efficient homes, more public transportation, etc. (e.g. May et al. Citation2006);

compaction or increasing the density of urban development (e.g. Breheny Citation1997);

new “eco-towns” or “eco suburbs” (e.g. Jenks & Jones Citation2010).

Therefore a relevant question is: can sustainability efforts be concentrated to a part of the city with the expectation that the results would spread throughout the entire city region? This question involves the geographical scale which has not received much attention in urban sustainability literature. Much of the literature dealing with spatial aspects discusses the nature of the global economic system and the competition between urban regions making it difficult to focus on environmental issues (Zuindeau Citation2006; Xu et al. Citation2008). In this paper we present a model that makes use of the economic theory of unbalanced growth in order to explore the possibility of achieving sustainable development in an entire urban region with the help of spatial imbalance.

This paper is divided into four sections besides this introduction. In the second section we discuss the theory of unbalanced growth and then reinterpret it to develop an unbalanced model for urban sustainable development. In the third section we discuss existing urban sustainable development models from the perspective of unbalanced growth. In the fourth section we briefly discuss existing urban sustainability initiatives and their spatial dimension. The final section includes reflections on the relative merits of the unbalanced model.

Unbalanced model for sustainable development

Theory of unbalanced growth

Albert Hirschman’s (Citation1958) unbalanced growth model (henceforth UBG) received substantial attention in development economics during the 1950s and 1960s. The model challenged the prevailing notions of stable equilibrium and balanced growth involving comprehensive large-scale and simultaneous investment policy as advocated by mainstream economists like the Nobel Laureate, Arthur Lewis (Citation1954). Similarly, Gunnar Myrdal’s (Citation1957, Citation1968) theory of circular cumulative causation rejects the idea of automatic self-stabilisation, which is a key assumption in the neo-classical equilibrium model, and locates the failure of virtuous growth circles in lees developed countries in social and institutional relations that are inimical to economic development. Structural factors are also central to the centre-periphery model where the relationship between advanced centre and less developed periphery are triggered by economic, social and political inequalities (Friedmann & Alonso Citation1975). There is a logical continuity between these models – underdevelopment is a result of cumulative social and economic processes that can be best countered by approaches that target specific sectors or places in an economy or region.

Hirschman explains underdevelopment in terms of the failure of virtuous growth circles in developing countries because social and institutional relations are inimical to economic development; he specially dwells on coordination failures that are a result of the inability to exploit external economies and increasing returns. Underdevelopment is a result of cumulative social and economic processes that can be best countered by step-by-step approaches that target specific directly productive activities (DPAs) in agriculture and manufacturing.

Hirschman proposes that in order to further industrialisation in developing countries, investments could be directed to one or a few DPAs, which could in turn stimulate the supply of inputs from the primary sector, e.g. agriculture as well as demand for DPAs’ output from another DPA or consumers. There are technical complementarities between economic activities that manifest themselves in the form of “shortages, bottlenecks and obstacles” which in turn induce investment in other sectors. Complementarities call forth a “never-ending series of inducements” and external economic effects (Hirschman Citation1958, p. 69–71). Hirschman distinguishes between two forms of inducement mechanisms within the DPA sector

backward linkages that bring about production of inputs that are needed by DPA in question, i.e. inducement in earlier stage of production;

forward linkages imply induced effects that utilise the output from the DPA as an input in some new activities (Hirschman Citation1958, p. 110–119).

The growth in the DPA sector triggers pressure with regard to the construction of social overhead capital (SOC), e.g. physical and social infrastructure. A minimum level of SOC is a prerequisite for the initial growth in the DPA sector. However, Hirschman rejects the idea that the expansion of SOC “must under all circumstances precede an expansion of DPA”. In fact he contends that development in DPA is likely to take place because of a shortage rather than excess of SOC. While a shortage of SOC creates a compulsive sequence, an excess of SOC may create a permissive and therefore weaker sequence (Hirschman Citation1958, p. 94–97).

Hirschman’s model was path-breaking because it serves as a conceptual tool to break the vicious circle of poverty caused by a variety of factors that reinforce one another. It identifies the rigidities leading to the inability to make use of external economies and increasing returns, low elasticity of supply and demand of factors and other structural characteristics of developing countries that affect development policies. Hirschman rejects the idea of automatic self-stabilisation which is a key assumption in the stable equilibrium model, as well as the notion that one factor per se is exclusive, but instead stresses that both economic and non-economic factors are central to the initiation and continuity development process. According to UBG, limits in the supply of domestic managerial and entrepreneurial decision-making capacity and the inelasticity of factor supply are two major reasons why balanced growth involving comprehensive programmes of large-scale simultaneous investments is untenable (Hirschman Citation1958, p. 63). Since developing countries lack resources to simultaneously create an integrated economy, Hirschman proposes a sequence of development stimuli which result in a chain of disequilibria; that is an economic stimulus creates disequilibrium that requires a further stimulus and so on. At each stage, an economic activity takes advantage of external economies created by previous expansion and at the same time creates new external economies to be exploited by other operators. Thus, by creating strategic imbalances within the DPA sector, as well as between the DPA sector and SOCs, Hirschman’s model provides the necessary impetus to break down the inertia that exists in developing countries.

These are the major tenets of Hirschman’s UBG model. The model provides interesting ideas for cities where we can also discern an inertia whereby structural and behavioural factors reinforce each other and move the urban system away from the path of sustainability. However, the UBG model focuses on imbalance between economic sectors whereas its reinterpretation for urban sustainable development involves territorial or spatial imbalance together with specific policy initiatives.

Reinterpreting UBG theory for an urban sustainable model

Sustainable development is often viewed as a process of mediation between production and consumption needs on the one hand and environmental goals on the other. Failure to attain sustainable development is a result of a vicious circle stemming from attitudes, public policies and socio-economic structures. The vicious circle stems from the failed attempts to recognise the dangers of continued appropriation of the carrying capacity, to exercise civic responsibility, and the fragmentation of socio-economic structure and consumerism that is constantly fed by advertisements and the media (Carley & Christie Citation2000, p. 181–183).

The main resistance to change comes from attitudes and socio-economic structures; their mutual reinforcement triggers cumulative effects of non-sustainable practices. The interplay between individual behaviour, socio-economic and political factors is responsible for this development and these factors cannot be arbitrarily separated. For example, decreasing the consumption of passenger car transport does not only depend on individuals taking greater environmental responsibility but also on mitigating structural factors that have increased the distance between home, work and shopping (see e.g. Jackson & Papathansopoulou Citation2008; Söderholm Citation2010). However, an implementation of a city-wide, comprehensive programme that requires simultaneous changes in various policy sectors and mobilisation of urban citizens for sustainable development is not feasible owing to the scale and fragmentation of most cities and the amount of resources that would be necessary. The application of a selected number of sustainable development policies in a target area in the city would mean an economising of scarce resources including “genuine decision-making” (Hirschman Citation1958, p. 63), allowing city authorities to learn from the success and failure and in fact applying gains obtained from a particular policy (say sustainable public transport policy) with the same or lower costs to other parts of the city. Sustainable development could thus proceed as a series of uneven advances in one part of the city and with the help of linkages it would hopefully work its way to other parts of the city.

The goal of unbalanced model is to develop forward and backward linkages at inter-personal, individual, and group-structure levels in order to create an interdependent socio-economic structure in the target area in the city. For example, forward linkage could be created through environmental education in schools and thereby inducing school children’s family members to adopt environment friendly habits. Economic and other incentives for local food stores to buy locally produced foodstuffs could create a backward linkage inducing local producers. The application of the UBG model requires careful selection of a target area as well as a set of policy areas and projects.

In order to define a target area for the application of the unbalanced model, we need to apply spatial imagination in which place is not merely a surface with boundaries around it, but it is also shaped by multiple networks and social and power geometries (Massey Citation2005). Consequently the target area need not coincide with one of the city’s administrative districts in order to avoid the risk of traditional “area-based” programme. The space so identified is not only characterised by a vicious circle of structural and behavioural non-sustainability but also contains an embryo of concern among the people living in the area about improving the area. A central notion is that the target area adopts local spatial dynamics as the starting point to develop green actions that hopefully can produce spin-off effects in the entire city. Therefore the target area has some strategic premises potentially favouring the emergence of forward and backward linkages.

The choice of policy fields and projects depend on the contextual factors that have bearing for the chosen target area. We can here suggest a few such fields in order to show the possible linkages and inducement mechanisms.

Education is one such policy field. Schools in the selected target area, which are attended by children in the target area, can introduce environmental education with practical features. School children can act as “eco-ambassadors” and induce family members to adopt environmental friendly habits (see e.g. Loukola et al. Citation2001; Gyberg Citation2003) about the impact of environmental education). The emergence of forward linkages from school children to parents, family friends and others can have significant effect on the environmental behaviour. This in turn may also lead to backward linkages such as in the form of purchase of locally produced foodstuffs and other daily necessities and recycling of household waste.

Another policy field is transport. Compaction in the form of higher density in building is not a sufficient condition for sustainable travel behaviour (see e.g. Jenks & Jones Citation2010; Söderholm Citation2010). Moreover, Söderholm (Citation2010) shows that state housing policies, rationalisation of retail, distribution of foodstuffs and other household necessities have increased the distance between home, work and shopping. Undoing this at the city level is a formidable process. However, step-by-step measures can be introduced in order to make residents in the target area choose more sustainable modes of travel such as walking, cycling and increased use of public transport. Constructing safe pedestrian and cycling paths, improving accessibility and reducing fares in public transportation can be accompanied by increasing parking costs, encouraging location of work places and providing incentives for local food stores. In this case, there are both forward and backward linkages in the form of reduction in air pollution, health improvement, increased social interaction and local production of food.

A third policy field is the greening of the target area. According to Jenks and Jones (Citation2010, p. 249), public green space in cities “is generally designed and managed to support the recreational activities of the people with little or no reference to the ecological benefits”. They suggest that the latter depends on how green spaces are distributed and constructed as well as what actions are taken to make people more conscious of various aspects of biodiversity. Designing new parks or improving the existing ones, and planting trees and shrubs in the streets could be accompanied by information to households, as well as making use of parks and green areas as pedagogical sites for school children and other target groups. Given the complementarities between recreation, health, sense of “belonging” and other aspects of social sustainability (Williams et al. Citation2010), greening policy has significant impact on structural aspects of the local community.

Exemplification of policy areas and projects can be extended. The advantage of the unbalanced model is to create an inducement sequences with the help of efforts that can transform the target area and valorise residents’ struggle to (re)appropriate places and regenerate local environments that have been deprived from their being a common good (see Carley and Christie (Citation2000) for examples of regeneration through the Groundwork Programme in the UK).

The application of the UBG model as outlined above involves constructing a social infrastructure that intervenes at the individual as well as collective level. The unbalanced model provides an alternative perspective that recognises socially grounded nature of human behaviour (Heiskanen et al. Citation2010). It may help to break the current impasse in the cities whose addiction to ecological resources is becoming vastly larger than the space they occupy and may help a small part of the urban society to face collectively issues concerning the use of natural resources that are not only local but also global common good.

In so far as the unbalanced sustainable approach influences structures and behaviours, the crucial question is not whether to create unbalances but what is the optimum degree of unbalance, where to unbalance and by how much? Of course the effort to concentrate sustainable development efforts to one target area in a city does not automatically lead to spin-off effects. There is always a danger that such districts remain showpieces of sustainable development without further spread-effects. It is therefore important to carefully think out the choice of the target area, the timetable showing the sequence of actions, obstacles and inhibitions to sustainable development including resistances induced by unbalanced growth measures.

Models of urban sustainable development

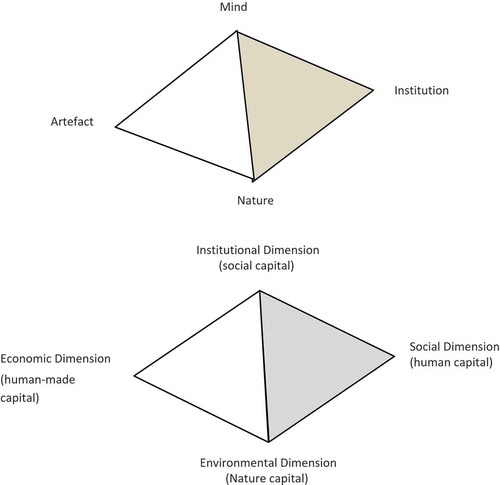

The term “sustainable development” has provided premises for developing models of the sustainable city connecting economic, ecological and social dimensions. However, the vague definition of the concept has not really helped to develop models that can be used for finding practical solutions to further sustainable development in the cities. Moreover balancing the three dimensions has been far from easy. For example, Campbell (Citation1996) argues that connecting economic, ecological and social problems results at a later stage in the failure to handle ecological and social problems. She maintains that in addressing these three fundamental priorities the resulting conflicts with regard to property, resources and development should be exposed (see ).

Various models of urban sustainable development have attempted to integrate the three dimensions of sustainable development and can be broadly classified in two categories: visionary and procedural models, respectively.

At the basis of the visionary models is the so-called “three-pillar” or “prism” of sustainability. In one version of the prism model, indicators are developed in order to show how social, human, human-made and natural capital is used to achieve an overall vision of sustainability (Valentin & Spangenberg Citation1999). In criticising this version of the model, Kain (Citation2000) argues that the economic dimension tends to contain assets from all the three dimensions. In his alternative prism model, Kain designates four dimensions: mind, artefact, nature and institution (see ).

The various versions of the prism model have been generally criticised for their lack of emphasis on the ecological dimension and underestimating the difficulty in achieving sustainability in all three dimensions (Stenberg Citation2001). The International Union for the Conservation of Nature proposed the “Egg of Sustainability” model in order to focus on the interdependency between human beings and the ecosystem (Guijt & Moiseev Citation2001). This model implies that sustainable economic and social development can only take place if the environmental carrying capacity forms the fundamental basis of the model (see ).

Trade-off between the three dimensions of sustainable development has, for example, inspired Haughton (Citation1997) to distinguish between four different visions of sustainable cities. These visions are then expected to lead towards strategies and policies for sustainable development:

Self-reliant cities that make “greater use of local environmental resources” minimise and redirect “waste flows…with minimum ecosystem disturbances”, reduce “external dependence” of resources and change “moral values…towards decentralised and cooperative forms of human endeavour” (Haughton Citation1997, p. 190; see also Morris Citation2008).

Compact, energy efficient cities that favour “higher residential density”, encourage “people to travel less by private transport” with the help of an “extensive and viable public transport system” and “seek to alter the environmentally damaging” urban behaviour (Haughton Citation1997, p. 191; see also Jenks & Burgess Citation2000).

Externally dependent cities which aim to reform “market mechanisms” so that they “work more effectively towards environmental goals, in particular by addressing the issues of externalities” but at the same time buy in “additional carrying capacity” from external areas (Haughton Citation1997, p. 192; see also Newman & Jennings Citation2009).

Fair share cities that examine “the environmental value of the resource and pollutant streams that enter and leave city systems” in order to arrive at agreements “between city and hinterland areas with surplus carrying capacity, provided that no environmental damage is done in the process” (Haughton Citation1997, p. 192–193; see also Kemp & Stephani Citation2011).

In order to meet the dramatic changes in the Earth’s climate, cities can be innovative agents to meet this challenge. For this purpose alternative visions of “low carbon cities” have been developed (Ruth & Coelho Citation2007). These visions show alternative strategies to alter urban behaviour, make structural changes in the built environment and introduce newer technologies. Many of these visions include policy changes that are outlined in self-reliant and fair share cities (see e.g. Feng et al. Citation2005).

These models of sustainable city address the spatial issue in the sense that they mention the relationship between the city and the hinterland, changes in urban design in order to promote compaction, and in location policies in order to reduce, for example, private transport and energy consumption. However, the models are primarily for the city as a whole, but naturally the ideas provided in these models can be used in unbalanced sustainable urban development.

With the increasing acceptance of “governance” to imply the management of a country’s or a city’s economic and social resources for development, involving public–private partnerships or with the collaboration of community organisations, procedural models for sustainable development have received increasing attention. Procedural models emphasise different aspects of governance. For example, Carley and Christie (Citation2000) have proposed the “action-networks” model for environmental management.

The action-networks model redefines environmental management as a “mediation process between economic/industrial needs and the maintenance of the biosphere with the objective of an increased level of integration” (Carley & Christie Citation2000, p. 177). The action network focuses on:

fostering “an ongoing political process of mediation and the building of consensus even where (environmental-economic) conflict is bound to be pervasive”;

promoting “new partnerships between government, business and non-governmental groups”;

developing “multilayered ‘nested’ networks, as a means of integrating efforts at sustainable development from the local to the international level” (Carley & Christie Citation2000, p. 176).

“flat, flexible organizational structure involving teamwork or participation;

equality of relationship among all relevant stakeholders;

vision and value-driven leadership;

an emphasis on participation and organizational learning;

undertaking continuous performance review and improvement; and

a method of network development in which events progress at a pace which is politically and culturally sustainable given local conditions” (Carley & Christie Citation2000, p. 176).

Similarly collaborative and deliberative models for sustainable urban regeneration have been developed by Healey (Citation1997) and Innes and Booher (Citation2010). For example, the US ecosystem management approach emphasises the inclusion of as a wide set of stakeholders as possible in order to have an effective planning for sustainability (Hall Citation1999). Collaborative efforts are not only limited to existing networks and interests but also informal links between individuals and between individuals and networks. Collaborative models in general, and action-research model in particular, provide many relevant ideas for carrying out the UBG model in a target of a city.

Some procedural models put emphasis on a specific part of the policy process, e.g. problem-structuring, evaluation and implementation. Examples of problem-structuring models involve, for example, “strategic choice” or “strategic option and development analysis” for sustainable development of urban infrastructure (see e.g. Rosenhead & Mongers Citation2001). In the case of evaluation, models have been developed in order to integrate Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) into more holistic decision-making. For example, the Commission of the European Communities has advocated the use of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for a “systematic and structured consideration of environmental concerns” as part of “harmonized planning procedures” (Commission of the European Communities Citation2009, p. 11). As a result, several attempts have been made to integrate environmental assessment and strategic planning (see e.g. Fundingsland Tetlow & Hanusch Citation2012). In ex poste evaluation of, or monitoring outcomes of, environmental policies indicators are frequently used. Environmental indicators are therefore useful to

“supply information on (particular) environmental problems”;

“support policy development and priority setting”;

“monitor the effects of policy responses” (Smeets & Weterings Citation1999; see also Organisation for Economic Development and Co-operation Citation2004).

Urban sustainability initiatives

There is an extensive literature on past responses and attempts to introduce urban sustainability initiatives (see e.g. Lafferty & Meadowcroft Citation2000; Jordan & Lenschow Citation2008). As we have mentioned earlier, urban sustainability initiatives are either limited to specific policy measures or focus on urban design or attempt to be more comprehensive.

By far the largest number of these initiatives are single policy initiatives, e.g. recycling of household and industrial waste (Berglund et al. Citation2010), renewable building material in housing (Söderholm Citation2010), greening cities (Werquin et al. Citation2005), increasing efficiency in energy supply and consumption (Carlsson-Kanyamma & Linden Citation2007) and environmentally sound transportation (May et al. Citation2006). They are pragmatic solutions, with recourse to “ecological rationality”, focusing on market incentives and attempting to change environmental behaviour in specific policy areas. Wherever households perceive economic benefits without too many encroachments in the daily life, there is a general willingness to participate in such activities. Households are reluctant to participate in activities that make greater demands on daily life, e.g. car use. Households’ mobility depends on structural factors that have brought about greater distance between home, work and shopping. Economic crises and subsequent rises in the price of fuel have not decreased the consumption of private car transport (see e.g. Jackson & Papathanasopoulou Citation2008; Söderholm Citation2010). Such a decrease is possible only through structural changes combined with raising taxes to make car use less attractive and reducing ticket prices in public transport.

Another set of urban sustainability initiatives emphasises changes in urban design, especially through compaction. Increasing building density is perhaps the most common initiative. Other examples are “sustainable new urbanism”, “concentrated decentralization” and “containing urban sprawl” (Jenks & Jones Citation2010). There are very few comprehensive studies evaluating the behavioural impact of sustainable urban design. One exception is a UK study edited by Jenks and Jones (Citation2010) which, with the help of 15 case studies from five UK cities, examines how more compact, high-density and mixed use urban forms affect energy saving, green space, travel behaviour, social interaction, community spirit, cultural vitality, range and quality of local services and economic innovations. They show that these sustainable urban design initiatives affect the behaviour of households with respect to home-based resource efficiency such as water and energy use but have negligible impact on travel behaviour, consciousness about biodiversity, social participation and economic viability (Williams et al. Citation2010, p. 183–214). Their conclusion is that sustainable built environments can only bring about sustainable lifestyles if measures are taken in order to change the structural premises that have locked people in unsustainable living environments.

The third category of urban sustainability initiatives are variations of eco-city model. Many of these initiatives are either in the form of proposals that have not been carried out, e.g. Dongtan in the Shanghai metropolitan region or eco-city projects that are underway – as in the United Arab Emirates or eco-towns in the UK (Jenks & Jones Citation2010, p. 5). Jenks and Jones (Citation2010, p. 6) feel that “There is a danger that these ‘models’ will become eco-theme parks, functioning in the similar way as carbon offset schemes, salving the conscience, and freeing the neighbouring cities to continue business as usual development” (see, also Jordan Citation2008).

The eco-city model is also a part of government rhetoric in sustainability policies, such as the Shenzhen Declaration on EcoCity Development (http://www.urbanecology.org) and the “eco-cities” model in the 10th Indian National Development Plan (Indian Ministry of Environment and Forests Citation2002). Here the officially stated objective is to optimise energy performance, creating sustainable industries, promoting social equity and involving all levels of the community in replenishing entire urban environments. According to Jordan and Lenschow (Citation2008), such objectives represent wishful thinking around the possibility of “socio-ecological cohesion” that are impossible to turn into effective action.

The above critique raises the question of how can urban sustainability arguments be turned into effective responses? Are there alternatives to the urban-design focussed or the more comprehensive eco-city approaches that pay attention to the everyday, messy reality of cities and towns that already exist? As we mention above, if individuals or civil society are to be true implementers of sustainable development, then behavioural aspects cannot be separated from structural factors. Against the backdrop of the above arguments, a pertinent question is if it is possible to achieve a change towards sustainable social practice, if behavioural and structural efforts in order to bring about such a change are limited to a specific part of the city, and hope that the spatial imbalance so created would bring about a momentum for a city-wide sustainable development? Is the unbalanced model for sustainable urban model outlined above appropriate for this challenging task?

Spatial imbalance for sustainable urban development: concluding reflections

In this paper we have argued, with the help of the theory of unbalanced growth, that spatial imbalance could provide a feasible approach for cities to carry out city-wide sustainable development. The unbalanced sustainable urban development model as proposed in this paper could be applied taking into consideration the messy, everyday reality in the city.

Bearing in mind the scarcity of resources including genuine decision-making in the field of environment and long established structural development that has resulted in cities as major resource consumers, we have, in this paper, argued that if sustainability efforts are concentrated to a part of the city they could gradually produce spin-off effects in the entire city.

The original theory of unbalanced growth was designed for creating imbalances in the economic sector for bringing about economic development in developing countries. We have reinterpreted the UBG model to focus on spatial imbalances in order to bring about sustainable development in cities. A major argument in the original theory was that creating strategic imbalances in the DPAs (industries) in developing countries, caught up in the vicious circle of underdevelopment, was a more plausible approach to bring about economic development rather than simultaneous industrialisation and infrastructure developed as advocated by the balanced growth model. The major aspect of this theory, to paraphrase in our case, is to propose policy measures in order to break the prevailing socio-political impasse in urban societies characterised by consumerism, increasing appropriation of ecological resources and to enable cities to develop and implement sustainable development policies.

Bearing in mind the prevailing socio-political and economic impasse in urban societies, we need alternative models to break this impasse in order to develop and implement sustainable development policies. The UBG model involves a shock therapy for urban societies that exhibit a large variety of social and economic contexts that makes city-wide comprehensive sustainable development programmes quite difficult. The unbalanced approach to sustainable development through its emphasis on linkages and demonstration effects could help to break down the inertia of attitudes and institutions.

A few carefully selected measures in an appropriate target area may hopefully bring about necessary reactions in order to enable sustainable changes in the entire urban society. However, the same factors that hinder comprehensive city-wide efforts may also obstruct the implementation of the unbalanced model. There is also a danger that the unbalance created in one area remains an isolated case without generating the desired spin-off effects. The model may seem a huge leap of faith and optimism but it may be worthwhile trying to break the current economic, social and political malaise prevailing in cities.

Acknowledgements

The editor and the three anonymous referees of this journal have provided many useful comments and suggestions that have been crucial in preparing the final version of the paper. The author would also like to thank Professor Valeria Mono for valuable comments on an earlier draft of the paper.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abdul Khakee

Abdul Khakee is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Planning and Environment, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. He researches the theory and practice of urban planning investigating planning evaluation, relationship between futures studies and planning, planning ethics and public participation.

References

- Batty M. 2008. The size, scale and shape of cities. Science. 319:769–771.

- Berglund C, Hage O, Söderholm P. 2010. Household recycling and the influence of norms and convenience. In: Söderholm P, editor. Environmental policy and household behaviour: sustainability and everyday life. London: Earthscan; p. 193–210.

- Breheny M. 1997. Urban compaction: feasible and acceptable? Cities. 14:209–217.

- Campbell S. 1996. Green cities, growing cities, just cities? Urban planning and the contradiction of sustainable development. J Am Plan Assoc. 62: 296–312.

- Carley M, Christie I. 2000. Managing sustainable development. London: Earthscan.

- Carlsson-Kanyamma A, Linden A-L. 2007. Energy efficiency in residences – challenges for women and men in the North. Energy Policy. 35:2163–2172.

- Carter N. 2001. The politics of the environment, ideas, activism, policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Commission of the European Communities 2009. On the application and effectiveness of the directives on strategic environmental assessment. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

- Feng H, Yu L, Solecki W. 2005. Urban dimensions of environmental change. Manmouth (NJ): Science Press USA Inc.

- Friedmann J, Alonso W, editors. 1975. Regional policy. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press.

- Fundingsland TM, Hanusch M. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment: the state of the art. Imp Assess Proj. 30:15–24.

- Guijt I, Moiseev A. 2001. IUCN resource kit for sustainability assessment. Gland: The World conservation Union.

- Gyberg P. 2003. Energi som kunskapsområde. Om praktik och diskurser i skolan [Energy as an area knowledge. On practice and discourses in schools] [PhD thesis]. Linköping: Linköping University, Department of Technology and Social Change.

- Hall MC. 1999. Rethinking collaboration and partnership: a public policy perspective. J Sustain Tourism. 7:274–289.

- Haughton G. 1997. Developing sustainable urban development models. Cities. 14:189–195.

- Healey P. 1997. Collaborative planning. Shaping places in fragmented societies. London: MacMillan Press.

- Heiskanen E, Johnson M, Robinson S, Vadovics E, Saastamoinen M. 2010. Low-carbon communities as a context for individual behavioural change. Energy Policy. 38:7586–7595.

- Hirschman AO. 1958. The strategy of economic development. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press.

- Indian Ministry of Environment & Forests. 2002. Ecocities in making, report by the central pollution control board. Delhi: Ministry of Environments & Forests.

- Innes JE, Booher DE 2010. Planning with complexity: an introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. Oxford: Routledge.

- Jackson T. 2005. Prosperity without growth: economics for a finite planet. London: Earthscane.

- Jackson T, Papathanasopoulou E. 2008. Luxary or “lock-in”? An exploration of unsustainable consumption in the UK: 1968–2000. Ecol Econ. 68:80–95.

- Jenks M, Burgess R. 2000. Compact cities: sustainable urban form for developing countries. London: Spon Press.

- Jenks M, Jones J. 2010. Dimensions of the sustainable city. Berlin: Springer.

- Jordan A. 2008. The governance of sustainable development: taking stock and looking forward. Environ Plan C. 26:17–33.

- Jordan A, Lenschow A, editors. 2008. Innovation in environmental policy? Integrating the environment for sustainability. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Kain J-H. 2000. Urban support systems: social and technical, socio-technical or sociotechnical? Göteborg: Chalmers University of Technology, School of Architecture.

- Kemp RL, Stephani CJ. 2011. Cities going green: a handbook of best practice. Jefferson (NC): McFarland & Co.

- Lafferty W, Meadowcroft J, editors. 2000. Implementing sustainable development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis AW. 1954. The theory of economic growth. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Loukola M-L, Isoaho S, Lindström K. 2001. Education for sustainable development in Finland. Helsinki: Ministry of Education.

- Massey D. 2005. For space. London: Sage.

- May AD, Kelly C, Shepherd S. 2006. The principles of integration in urban transport strategies. Trans Policy. 13:319–327.

- Molotch H. 1976. The city as a growth machine: towards a political economy of space. Am J Socio. 82:309–332.

- Morris D. 2008. Self-reliant cities: energy and the transformation of Urban America. Washington (DC): Institute of Local Self-Reliance.

- Myrdal G. 1957. Economic theory and underdeveloped regions. London: Duckworth.

- Myrdal G. 1968. Asian drama. Harmondsworth: Pelican.

- Newman P, Jennings I. 2009. Cities as sustainable ecosystems: principles and practices. Washington (DC): Island Press.

- Organisation for Economic Development and Co-operation 2004. Key environmental indicators. Paris: Organisation for Economic Development and Co-operation.

- Peters BG, Pierre J, editors. 2007. Handbook of public administration. London: Sage.

- Rees WE. 2004. The ecological footprints of cities: urban sustainability and vulnerability in the 21st Century. Paper presented at: Final Workshop of the US-Japan Urban Ecosystem Initiative, New York, Nov 22–24.

- Rosenhead J, Mongers J, editors. 2001. Rational analysis in a problematic world revisited. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley.

- Ruth M, Coelho D. 2007. Understanding and managing the complexity of urban systems under climate change. Clim Policy. 7:317–336.

- Smeets E, Weterings R. 1999. Environmental indicators: typology and overview. Copenhagen: European Environmental Agency.

- Stenberg J. 2001. Bridging gaps: sustainable development and local democratic processes [masters thesis]. Göteborg: Chalmers University of Technology, School of Architecture.

- Söderholm K. 2010. Policy-driven socio-technical structures and Swedish households’ consumption of housing and transport since the 1950s. In: Söderholm P, editor. Environmental policy and household behaviour: sustainability and everyday life. London: Earthscan; p. 149–172.

- Söderholm P, editor. 2010. Environmental policy and household behaviour: sustainability and everyday life. London: Earthscan.

- Valentin A, Spangenberg J. 1999. Indicators for sustainable communities. Paper presented at: International Workshop on Assessment Methodologies for Urban Infrastructures, Stockholm, Nov 20–21.

- Wackernagel M, Rees WE. 1996. Our ecological footprint: reducing human impact on the earth. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

- Werquin AC, Duham G, Lindholm G, Oppermann B, Pauleit S, Tjallingii S, editors. 2005. Green structure and urban planning. Final report of COST action CI, cost programme. Brussels: COST Office.

- Williams K, Dair C, Lindsay M. 2010. Neighbourhood design and sustainable lifestyles. In: Jenks M, Jones J, editors. Dimensions of the sustainable city. Berlin: Springer; p. 183–214.

- Xu L, Yang Z, Li W. 2008. Modelling the carrying capacity of the urban eco-system. Paper presented at: 2nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Wuhan University, Wuhan, May 16–18.

- Zuindeau B. 2006. Spatial approach to sustainable development: challenges of equity and efficiency. Reg Stud. 40:459–470.