Abstract

The quantity of writing on sustainable urban development continues to expand. Much of this writing, whether using a theoretical or empirical focus (or both), takes a strongly normative tone, exhorting actors in locations across the globe to make greater efforts to move development trends in more sustainable directions. This normative work is, of course, of vital importance, but in this paper, we argue for more attention to the context within which development takes place, particularly where that context imposes severe, perhaps crippling, constraints on opportunities for path-breaking actions. To explore this issue, we introduce the case study of the Indian hill station town of Darjeeling. We assess the sustainability issues faced by the town (including rapid population growth, limited availability of land, dynamic development arena) and analyse the ongoing attempts by local governmental and non-governmental actors to deal with those issues, within constraints of physical location and an intensely contested politico-governance framework that we suggest are examples of intense contextual constraints.

1. Introduction

The topic of urban sustainable development is one which has received a great deal of attention over many years – even before such a term was coined, many authors have wrestled with the problems of balancing economic, social and environmental issues when considering how best to manage the growth of settlements across the world (World Commission on Environment and Development Citation1987; Lélé Citation1991; Ekins Citation1993; Wheeler & Beatley Citation2008). In recent years, of course, this journal has hosted some of these debates, with a focus on interdiscipinarity and intersectionality of approaches to economic, ecological and social sustainability (Keivani Citation2010a). Whilst many of these contributions emphasise the “multi-faceted nature of the sustainability debate” (Keivani Citation2010b, p. 12) and acknowledge the “interplay between social and technical solutions” (Williams Citation2010, p. 131), there remains a tendency to downplay, if not ignore, the constraints put in place by the context in which development takes place. This context can, despite the best efforts of policy-makers, planners, NGOs and other stakeholders, effectively limit the opportunity for the sort of path-breaking innovations often necessary to achieve sustainable urban development.

To illustrate the nature of such binding constraints, this paper presents an analysis of the attempts at sustainability policy and practice within the development structures of governmental and non-governmental stakeholders in Darjeeling, India. Since its settlement as a centre for summer administration by the British, Darjeeling has continued to develop and expand, attracting migrants from across India, Nepal and Bhutan. As the largest urban centre in the uplands of West Bengal and Sikkim, Darjeeling acts as the financial, administrative and social confluence of the region (Munsi Citation1980; Portnov et al. Citation2007). Whilst development has enabled Darjeeling to position itself as an essential service centre, it has been less successful in addressing the demands of sustainable expansion. Such roles place greater pressures on Darjeeling compared to other uplands towns such as Gangtok, Shimla and similar-sized towns in Nepal.Footnote1 As a consequence, the growth of Darjeeling Municipality can be considered juxtaposed: it is a location that not only thrives on development but also struggles to manage this process sustainably due to a complex interplay of dynamic political and physical influences. Reflecting on the development constraints identified within Darjeeling provides a practice-based assessment of the difficulties involved in translating conceptual sustainable development discourses into effective delivery. It also highlights that comparable constraints are visible in a number of upland areas, i.e. Gangtok (Sikkim), Shimla (Himachal Pradesh) or Shillong (Meghalaya).Footnote2 In each of these locations, access to natural resources, population change and addressing the Indian growth agenda have each placed constraints on the application of sustainable development in the uplands. However, due to the importance of Darjeeling as a regional centre of commerce and political power, the barriers to sustainable growth could be considered to be more acute. What is apparent from the research literature is that the physical constraints placed upon upland areas magnify the problems of planning for sustainable urban development compared to India’s megacities (Ghosh Citation2012).

With reference to the wider development debates in India, and globally, a study of the barriers to sustainable development in Darjeeling illustrates that sustainability is not a linear process. As Wisner et al. (Citation2004) and Williams (Citation2010) argue, sustainability offers an evolutionary interpretation of growth. Darjeeling, despite its smaller scale compared to other locations, for example the capital of West Bengal State Kolkata, provides insights into this complexity. Over the past 30 years, the interplay of economic, environmental and social activities has become accepted as providing the foundations of sustainable development. This paper suggests, as Wisner et al. (Citation2004) and Middleton and O’Keefe (Citation2001) propose, that sustainability thinking can be reframed to contextualise development alongside political and geographical constraints. This paper explores this approach to debate whether macro-scale assessments of sustainability are the most appropriate forms of investigating in all contexts.

Darjeeling is a comparatively small settlement, in contrast to the “megacities”, which receive much focus in discussions of Indian development (Rangan Citation1997; Jain Citation2003; Rajvanshi Citation2003). However, despite India’s increasingly urban population, most of its citizens live outside megacities, so a renewed focus on other towns and cities in the country may be required (as advocated by Wheeler & Beatley Citation2008). Evaluating the development of smaller or marginal urban areas provides a microcosm of the interactivity of policy and practice within the politicised narrative of sustainability. It is therefore prudent to suggest that new forms of urbanisation in upland areas (and in smaller cities) are extending the knowledge of what is justifiably considered as sustainable urban development. It should also be noted that unlike India’s large urban areas, the Indian Government, and indeed the West Bengal State, has not legislated a specific planning policy for hill stations across the nation. The present study thus provides insights into how development pressures have diversified where neo-liberal growth policies have been applied to more marginal border and upland areas such as Darjeeling or Shimla (Bingeman et al. Citation2004; Dréze & Sen Citation2013).

Drawing on case study evidence generated in Darjeeling, the paper questions, through local stakeholder commentary, how sustainability has been integrated into local planning practice, whether such a process is possible and if, where policy exists, it supports effective and appropriate development. It goes on to evaluate how the governance of Darjeeling and its relationship with the West Bengal State and the Gorkhaland Movement, major landowners and the citizens of the Municipality frame sustainability debates and the subsequent implications of this complex relationship.

The paper concludes by suggesting that major contextual constraints limit the scope for actors to take the kinds of major steps required to deliver dramatically more sustainable development in the longer term. The paper therefore argues that although conceptual understandings of sustainable development are central components of a rational development debate, context-specific constraints need to be considered more explicitly if possibilities for smaller-scale innovations are to make a positive contribution to short- and long-term sustainability goals.

2. Conceptualising, representing and understanding urban sustainable development

Whilst it is generally agreed that the broad parameters of sustainability derived from the Brundtland report, i.e. “the prudent use of environmental resources and inter- and intra-generational equity” (Williams Citation2010, p. 130), still hold true, it has also been observed in the pages of this journal that “there is still a lack of consensus on precise conceptualisations” (Keivani Citation2010b, p. 14) around urban sustainable development. This is perhaps in no small part because the most common of these conceptualisations suggests that sustainable development involves the balancing of three (or more) aspectsFootnote3 of development to ensure that none dominates. Typically, these three are summarised as economic, social and environmental, with cultural often included as a fourth (Kirkby et al. Citation1995; Basiago Citation1999).

As noted by Campbell, this type of conceptualisation has strong normative tones, with a tendency for individuals (in this case, planners) to position themselves as advocates for one aspect or another – “In the end, planners usually represent one goal – planning perhaps for increased property tax revenues, or more open space preservation, or better housing for the poor – while neglecting the other two” (1996, p. 297). This emphasis of one aspect over another is, in itself, perhaps due to the difficulty inherent in attempting to deliver all three – or, as some would argue, because the growth (read capitalism) discourse is so strong that one either supports it, or sets oneself up in opposition to it (Basiago Citation1999; Walker & Salt Citation2006). A lack of understanding of the intersectionality associated within sustainability narratives can, in specific location, undermine the translation of conceptual ideas into practice (Ekins Citation1993; Jain Citation2003).

Although competing needs are commonly used as justifications to modify approaches to urban development, there is an assumption in some quarters that growth occurs in cycles and that it will return to a state of equilibrium. At this point, the tenets of sustainable development will once again be aligned to balance development needs with an understanding of environmental and social capacity (Guy & Marvin Citation1999; de Silva et al. Citation2012). Over the last 30 years though, there has been seen a shift away from a stasis in development towards a constant re-evaluation of the role performed by the urban realm. This leads to the view that development should be seen as a constantly shifting arena where hypotheses of balance are often invisible in development contexts (Boone Citation2010).

Attempts to balance such competing sustainability interests within a growth agenda have proved difficult to achieve in a number of locations in India (Drèze & Sen Citation2013). Questions are frequently raised querying whether sustainability and development are compatible, especially in marginal environments. Due to the divergent rationales that underpin each, Wisner et al. (Citation2004) suggested that there is a fundamental complexity to development agendas that often fails to balance growth and need. To comprehend the complexity of these interactions, it is necessary to understand the shifting nature of property rights and access arrangements in upland areas and how these are configured within the consciousness of local and meta-scale institutions (Subba Citation1999; Middleton & O’Keefe Citation2001). Whilst access to resources provides recourse for individuals and communities to shape development, government and economic institutions may undermine the development process, which then potentially becomes unresponsive to change (Chettri Citation2013).

Sustainable development is therefore conditioned by the interactions, relationships and conflicts that arise from a perceived need for growth (Middleton & O’Keefe Citation2001). Whilst developers, politicians or environmentalist hold solipsistic views, if an equitable approach to development is to occur, a more balanced process of integration is needed. Although a number of actors hold obstinate viewpoints, sustainable development thinking argues for a more reflective approach to growth. The role played by different actors, coupled with the interplay with the socio-economic environment, illustrates how shifts in responsibility (legislative, communal or environmental) can impact sustainability (Jepson Citation2001; Vidyarthi et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, there is a conceptual assumption that development can be framed as a collective and equitable process between actors. This implies that there is an overarching responsibility to ensure that sustainability principles are visible within development programmes (Munsi Citation1980). However, this process can become disjointed, depending on how and whether investment objectives are met; as evidenced in the continued development of informal or illegal settlements across many parts of the “developing” (and “developed”) world (Basiago Citation1999).

A normative approach to development suggests that actors and stakeholders should consider the sustainability credentials of a given investment prior to implementation. However, such debates do not necessarily reflect an understanding of sustainability principles, approaches or outcomes (Walker & Salt Citation2006). Discussions therefore rely upon expertise and engagement between stakeholders to ensure that projects move effectively from debate to implementation. Misappropriating sustainability rhetoric could, however, be deemed as damaging development in marginal locations, as it may lead to inappropriate or short-term growth strategies (Keivani Citation2010b). Whilst it is important to improve the visibility of sustainability within development debates, unless there is an engaged understanding of its implementation value, rhetoric can, in effect, outweigh the process of application.

Evaluating whether development in a given location can be considered sustainable raises a number of questions focussing on the roles of the economic, environmental and socio-political actors in this process. This debates whether the relationship between actors and the environmental resource base can be considered rational. It has also been argued that debating sustainable growth as an equitable process is flawed due to the complexity of influences that underpin development (Williams Citation2010). Such proposals can be considered to be intensified in geographically marginal areas, e.g. Gangtok or Darjeeling, where the availability of land and its geographical composition limit the viability of growth (Blaikie Citation1985). In response, the politicisation of development debates have focused predominantly on social or economic issues, undermining calls for greater conservation of environmental resources (Middleton & O’Keefe Citation2001). Furthermore, the lack of a normative urban development process in upland states, compared to cities in the plains, illustrates a potential gap in the identification of specialised investment programmes focussed on physically constrained landscapes.

Each application of sustainable development, especially in upland areas, where the geo-political context appears to intensify anomalies in growth, presents a spatial, temporal and socio-economic/politico-economic perspective on development (Portnov et al. Citation2007; Chettri Citation2013). This process has been identified within India’s Himalayan states exacerbating the tensions between growth and sustainable development debates (Peet & Watts Citation2004). Complexity exists between each of these influences and is a factor in subsequent interactions between current and future development (Wisner et al. Citation2004). Spatially, development reviews the capacity of the physical environment and the opportunities it provides to support development. Whilst growth agendas are inherently temporal, they do reflect the evolving relationship between people and the environment (Chettri et al. Citation2007). The spatial constraints of upland environments highlight the limitations of land availability due to a lack of accessible and structurally appropriate locations, at both local and regional scales.

Another aspect of the sustainability literature relevant to this context is an understanding of accountability for managing growth. Whilst development is reacting to growing service and infrastructure needs, there is a concomitant need to retain a strong governance structure to ensure that investment is managed effectively (Wisner et al. Citation2004). The influence of different socio-economic actors can lead to confusion over who is responsible for development. It can also be argued that development in environmentally marginal locations is subject to greater variation in the applications of legislative accountability because of the constraints placed upon urban growth by the physical environment (Campbell Citation1996).

Such constraints are rarely foregrounded in discussions about sustainable development – there can be a tendency to assume that if someone (whether this be planners, politicians, developers or other stakeholders) did their jobs better, or were more focussed on aspects of development other than economic growth, then (more) sustainable development could be achieved. The following paper does not suggest that the normative aspect of sustainable development literature should be downplayed, rather it sympathises with the difficulty faced by professionals, in locations around the world, who find themselves constrained by circumstances beyond their (and possibly anyone’s) control.

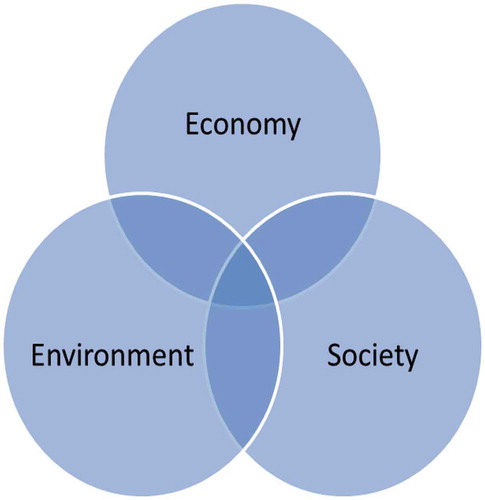

To illustrate this point, it is useful to return to the topic which opened this section – the conceptualisations of sustainability, specifically the representations of those conceptualisations. The “classic” conceptualisation of sustainable development is the “Venn diagram”, featuring three overlapping circles that represent economic, social and environmental aspects of sustainable development, with the “intersection” in the centre (see ).

There are of course many other ways of representing sustainability (Mann Citation2009, for other examples), and whilst some do include reference to a broader context, in the large part, they focus on the three aspects of sustainability and neglect what can be of critical importance – the context within which development occurs in a particular locale, specifically, the constraints imposed by that context. This is, of course, partly because such visualisations are intended to be both generalisations and, broadly, universally applicable. This itself is troubling, given some of the “culturally and geographically specific ideas” (Williams Citation2010, p. 130) around sustainability. This paper does not wish to add unnecessary complexity to the debate around the imposition of models from the “developed” to the “developing” world (Roy Citation2009), rather it argues for an increased focus on context/constraint in considerations of sustainable development. Therefore, whilst it is important to reflect on the evolutionary conceptualisations of sustainable urban planning, there is an equal, if not greater, validity in some locations, to concentrate on the practicalities of implementing such notions in localised planning.

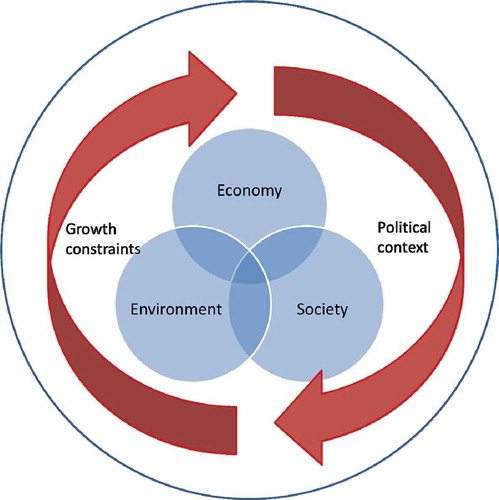

In the case of Darjeeling, the paper moves on to discuss, the important elements of context are political and physical (the latter in the sense of intense constraints on growth) – see for an illustration. Clearly in other cases, especially within India, the critical elements of context will vary, but as the paper illustrates, without a sharp awareness of these constraints, exhortations for a more “sustainable” approach to development can appear trite to those working on the ground (Jain Citation2003; Singh et al. Citation2010).

3. Darjeeling

The town of Darjeeling lies in the north of West Bengal in close proximity to the Sikkim, Nepalese and Bhutanese borders (see ) . It is located at an elevation of 2050m (6730ft) above sea level. The town was built by the British as a so-called “hill station”, a base for the colonial administration in Kolkata, capital of West Bengal State, to retreat to in the heat of the summer months.Footnote4 The value of Darjeeling as a hub of economic and social activity remains part of the dominate rhetoric of the Municipality’s government promoting its value locally and at a national level.

At the time of its development in the mid-nineteenth century, the town was intended to have a population of no more than 10,000, with the sewage and other infrastructure provision designed accordingly. The 2011 Indian census found the population of the Darjeeling “urban agglomeration” at that time to be 132,000 (Census of India Citation2011), but as discussed below, this is apparently a substantial underestimate, excluding as it does those living in temporary or unofficial/illegal homes. The paper will also propose that the provision of the town’s infrastructure has comprehensively failed to keep pace with this growth in population. The situation is further exacerbated by the substantial (up to 200%) growth in population during the tea and tourist seasons, as migrant workers travel to the town to work on tea plantations, act as drivers and porters, and support the town’s tourism industry (Bhattacharya Citation1992). This fluctuation in population, unsurprisingly, has major implications on the capability of the town’s infrastructure to cope.

The Municipality of Darjeeling is one of six towns (the others being Kalimpong, Kurseong, Matigara-Naxalbari, Siliguri and Phansidewa) in the District of the same name and is the commercial centre of the West Bengal uplands.Footnote5 The area is supported economically by military spending, revenue derived from tea gardens, seasonal tourism and taxation. Darjeeling’s growth as an area of economic prosperity is directly linked to the climatic and geographical distinctiveness of the uplands.

The District of Darjeeling covers an area of approximately 3149 km2; ranging from the plains of Siliguri to the hills of Darjeeling and Kalimpong. It houses a population of over 1.8 million. Its location close to the Nepalese, Bhutanese and Sikkim borders also makes the area strategically important for India’s military (Chettri Citation2013). Darjeeling can thus be considered to act as the primary urban conurbation of the region. As a consequence, its position is more important than a “standard” urban centre as Darjeeling transcends the economic and environmental boundaries of the Municipality and holds a regionally important position for the growth of upland West Bengal, Sikkim, Nepal and Bhutan.

Historically, Darjeeling has seen successive waves of immigration to support its economic growth. The resident population is therefore ethnically diverse and polarised in a number of its social and political conventions (Chakravti Citation1997; Chettri Citation2013). Demographic and ethnic diversityFootnote6 has led to the development of a range of politically engaged ethnic groups within the population of the District and Municipality of Darjeeling, and within their respective administrations, the most prominent of which are the ethnic Gorkha people. Distinctions are identifiable between upland and plain populations, as well as illustrating additional diversity between upland populations. The growth of the “Gorkhaland” autonomy movement has been linked to the multicultural nature of the region’s population (Acharya Citation2009).

The growth of calls for a Gorkhaland autonomous political unit or state has a long history in Darjeeling. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there were continued appeals for Darjeeling and the surrounding upland areas to separate from British India and post-independence West Bengal (Khawas Citation2009). The granting of self-autonomy was proposed to enable upland ethnic communities to gain a political voice through the transferal of funding and legislative power from the centre of the state and nation to Darjeeling and the periphery.

The rise of the Gorkhaland movement through the twentieth century focussed on the expression of the Gorkha people being “politically voiceless, culturally insecure and economically deprived” (Subba Citation1999, p. 302) within the structures of Indian and West Bengali politics. One element of this process was the notion that the British, and subsequently the West Bengal Government, had developed a discourse of governmental isolation actioned through segregationist policies towards Darjeeling (Sarkar Citation2012), the outcome of which has been a circular process of calls for autonomy in order to address territorial, linguistic and ethnic marginalisation within the decision-making process. Throughout the 1900s, calls were made for a “separate administrative set-up” to create a Gorkha-led administrative unit located within but legally autonomous from the West Bengal State (Subba Citation1999). This shift in power was seen as, a priori, the most significant mechanism to promote development. The establishment of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (1988), the Gorkhaland Autonomous Authority (2011) and the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA) (2012) have acted as recent conduits engaging the state in a dialogue regarding autonomy. The process is ongoing and has led to continued debate over the utility of such a process in creating the called-for autonomous political unit.

Attempts to establish sustainable development practices in Darjeeling are also subject to a cyclical process of engagement and disengagement with the West Bengal State (Ghosh Citation2009). The perceived marginalisation of the uplands by the state, as stated above, and despite the passing into law of the 74th Amendment Act,Footnote7 has embedded dissenting voices within the governance structures of Darjeeling Municipality, and its elected members (Economic and Political Weekly Citation2011). The implications of the above manifest themselves in the perception that an autonomous Gorkhaland State would facilitate a more prosperous and sustainable Darjeeling (Munsi Citation1980; Chettri Citation2013); there is little evidence, though, supporting this view within the academy or practitioner literature. It is also possible that the prolonged Gorkhaland agitation may be facilitating a weaker form of local governance, as the local development issues are subsumed into broader autonomy debates.

The outcomes of this research show that such debates have also been influenced by a perceived marginalisation of local populations, resulting in a lack of funding and services for the uplands by the West Bengal State, an issue that will be returned to below. The ethno-political dynamism of the area can therefore be considered to have been a central driver of urban development conflicts (Chakravti Citation1997). Furthermore, the lack of positive responses to growth from the West Bengal Government has fostered a sense of communal animosity towards the centre, which, some interviewees reported, appears to be reciprocated. This political context, as this paper goes on to argue, places a major constraint on the ability of the Municipality’s administration to deal with the issues it faces. A lack of specific policy focussed on the development, and subsequent management, of an upland hill station town is one element of this process. The focus of this paper though, is not to present an in-depth discussion of the governance issues calling for an autonomous Gorkhaland state. Rather, it uses the political complexity of West Bengal–Gorkhaland to illustrate how applying sustainability principles in Darjeeling is framed through four major pillars: economic, environmental, social and political.

A second major source of contextual constraint is the physical environment of the Municipality. Darjeeling was deliberately built in the hills of northern West Bengal to take advantage of the relatively cooler climate in comparison with the plains. The town is built on a ridge (see ), which severely restricts the room for physical expansion of the town’s built fabric. Further, it is surrounded by privately owned tea gardens, land owned by the military, and protected forests, so even if the topography was less hostile, there is little scope for the town to expand. These constraints have not stopped the population of the town growing, with the inevitable result of ever higher density in the existing developed area, leading to increased pressure on the already overstressed infrastructure network.

The political and physical context of Darjeeling sets the scene for an evaluation of attempts by a range of governmental and non-governmental actors to deliver a form of development which balances the social, economic and environmental aspects of sustainability (Chakravti Citation1997). It is worth briefly reflecting on the choice of Darjeeling from another perspective – that of scale. As noted in the introduction, discussions of urban sustainable development tend to focus on larger cities – this is understandable, given the impacts such settlements have on environmental, social and economic sustainability indicators and, by corollary, the potential for alternative development pathways to have more substantial effects. This is particularly the case in countries such as India, where the problems of unsustainable urban development in the megacities of Kolkata, Chennai, Delhi and Mumbai are so increasingly visible that they command the majority of government and academic attention. However, we must not forget that “small towns account for a significant fraction of the total population in many regions” (Mayer & Knox Citation2010, p. 1545).

In India, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of towns classified as urban, as the population density increases and the proportion of the population engaged in agriculture declines (Ghosh Citation2012). So, whilst the population of small towns, such as Darjeeling, is lower than those in India’s megacities, in aggregate, the proportion of the population living in such towns is large, and consequently, the implications of non-sustainable development similarly so.

4. Method

To evaluate the sustainability challenges faced by Darjeeling, a series of open-ended interviews were conducted with practitioners, environmental campaigners and government officials active in the planning and management of the District of Darjeeling.Footnote8 The breadth of interviews included individuals who directly influence planning legislation and practice, officers working for non-governmental agencies and environmental campaigners engaged with upland issues. highlights the background of each interviewee with specific reference to employers, development responsibilities and the date and location of each interview. The focus of the interviews varied depending on the specific expertise of each interviewee; however, the overarching topics covered were: the development issues facing the District/Municipality; the governance of urban development in the areaFootnote9; managing growth; local and regional influences on development; and possible solutions to the development issues faced by the District/Municipality. Interviews were conducted over a 7 day period (30 March–6 April 2013) in Darjeeling, Kalimpong and Siliguri. In the sections which follow, these interviews are quoted directly except in some cases where quotes could be considered controversial, so have been anonymised.Footnote10

Table 1. Interviewees and planning responsibilities.

5. Key sustainability issues in Darjeeling

Interviewees repeatedly identified two main concerns affecting the sustainability of development in the District and Municipality of Darjeeling. First, the degree of unchecked, informal and illegal development within the Municipality – since independence, the population of Darjeeling has escalated to at least 130,000, with a number estimating that during peak times, the transient population increases this to between 300,000 and 500,000.Footnote11. Second, the lack of adequate or efficient water, sanitation and electricity infrastructure – key issues in terms of public health, equity of access to services, and for the economic prosperity of the area, reliant as it is on tourism. Furthermore, it was proposed that addressing sustainability issues at a municipality scale may actually limit the scope of investment opportunities. Therefore, to achieve sustainability in Darjeeling, it may be necessary to conceptualise, and apply sustainable development practices, at a higher scale – whether this be the West Bengal State level, or, as interviewee 5 suggests, at the North Eastern Council level (see below for further discussion on these issues).

Individually, each of these concerns would represent a major challenge to administrations of the Municipality and District of Darjeeling as they attempt to pursue more sustainable urban development – even if there were no issues with infrastructure, controlling urban growth would be difficult; and even if the population of the town stopped growing, provision of infrastructure would remain problematic.Footnote12 However, when the two issues interact, as they clearly do, they present a cumulatively even greater test to the long-term future of the area. They also illustrate that dealing with development pressures cannot be considered to be a self-contained or static issue. Interactions between different influences indicate the prevalence of a complex socio-economic relationship between people and the environment in Darjeeling. They also suggest that an awareness of the environmental–political characteristics of development is required to ensure that growth is strategically planned at a municipal scale.

The next three subsections discuss these two concerns sequentially before summarising the overwhelming constraints faced by those promoting more sustainable development in Darjeeling. Each section presents interviewee commentary signposting the interplay between discussions of economic growth, the changing polity of Darjeeling’s development context and the constraints placed on expansion by the physical environment of the area. Within each section, the complexity of development builds an evidenced interpretation of growth, which is subsequently extended conceptually, and in terms of implementation, in Sections 5.3 and 6.

5.1. Unchecked/unplanned/informal development

As discussed above, there is effectively no space for the town of Darjeeling to expand, but this has not stopped the population growing, with consequent additional physical development. This is, in large part, due to the economic “pull” to Darjeeling of the employment opportunities available in the tourism and tea industries. Despite an active campaign led by the Chairman of the Municipality (Interview 6Footnote13) and local NGOs the Federation of Societies for Environmental Protection (FOSEP) and Darjeeling Ladlenla Road Prerna (Interviews 2,Footnote14 and 3Footnote15 and 4Footnote16) highlighting the vulnerability of the physical environment of the District as a whole, development in Darjeeling has continued.

One interviewee highlighted the dissonance between the presumption on the part of politicians and other stakeholders, including landowners and the military, that development is needed to grow the economy, whilst acknowledging the inability of the physical environment to cope with growth (Interview 8Footnote17). Darjeeling is thus exerting continuing pressures onto its natural resource base, which is considered by many as unsustainable (Interview 10 andFootnote18).

The Chairman of the Municipality (Interview 6) is acutely aware of the problems that development causes, stating that “[we] should not have heavy construction in an area like Darjeeling”. A further difficulty identified by the majority of interviewees was the challenge of balancing the needs of the current population with those of an expanding one, caused in part by continuing migration to the town.

It was reported by Interviewees 8 and 10 that due to continual migration from external locations, the Municipality found it difficult to manage environmental resources; as it could not limit migration, it was unable to meet the service and housing requirements of a growing population. Interviewees (No. 1,Footnote19 2, 6 and 7,Footnote20) also stated that the lack of funding allocated to Darjeeling from the West Bengal State Government was hindering progress. In part, this is because the fluctuating population (employed on a seasonal basis in tea gardens and the tourism industry) are not registered as residents in the Darjeeling census, so West Bengal State is not obliged to make financial resources available for additional service provision. Informal population growth was also identified as undermining the processes of tax collection, which pays for services, due to a disproportionate number of migrant workers who may not pay tax in the Municipality (Interview Nos. 4 and 6).

The growing population was therefore viewed by Interviewees 2 and 6 as failing to bring with it a corresponding level of financial support for Darjeeling – instead, it creates an additional need and demand for services. As a consequence, the Municipality and District has found it hard to implement an effective programme of control or formal urban planning, for two main reasons: first, the lack of institutional capacity to produce/implement a plan, and second, inadequate implementation of the regulations that do exist to control development (Interview 9,Footnote21). A local architect evaluated this scenario (Interview 7) noting, “[There is] no proper town planning in Darjeeling; no expansion programme despite the town bursting at the seams”. Each of the 10 interviews conducted noted that there was a lack of funding allocated to urban planning in Darjeeling. Critics of the West Bengal Government argued that the continuation of such financial constraints explicitly restricts the Municipality’s ability to plan sustainably. Although locations in the plains of West Bengal (i.e. Siliguri) have received proportionally greater levels of funding for personnel and development control systems, the same level of investment has not been replicated in Darjeeling (Interviews 1, 6 and 7). The Municipality also stated that despite repeated requests for additional funds, the state government has persisted in limiting its financial commitment to the planning of Darjeeling (Interview 6).

This, along with the lack of qualified planners in the area, means that no town planners are employed by the Municipality (Interviews 7 and 8). The lack of financial or human capital is restricting the Municipality’s capacity to develop a masterplan for the town. A draft plan was reportedly produced by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) at some point in the recent past (Interviews 2 and 3), but was never taken further. Awareness of the strategy was also limited within the Municipal government, which itself was criticised for a lack of input from local communities across the Municipality in the consultation stages (Interview 6).

The lack of a masterplan is exacerbated by the lack of capacity of the Municipality to enforce regulations, which, in theory, limit the height and density of new buildings in the area (Interview 5Footnote22 and 8). Regulations put in place at the State level dictate that new buildings should not exceed 11.5 m in height, but Interviewee 3 observed that politicians and officials routinely give permission for buildings of up to 30 m in height. This was ascribed to corruption and weak governance, with the ability for a “fine” to be paid to officials to “regularise” development which is not in accordance with regulations (Interviews 10).

At the same time, a form of “communal collusion” occurs to legitimise development not in accordance with another regulation – that requiring 1.2 m “setbacks” for new buildings to ensure space between them for health and safety reasons. It is possible for the developer/owner of a building to obtain a “No Objection Certificate” from neighbouring properties, which means that the Municipality has no legal rights to enforce demolition or remove an illegal structure (Interview 7). Interviewees also explained the prevalence of the “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” mentality to the issuing of these certificates – effectively a swapping of approval, so two or more neighbouring properties can dispense with the setback requirement, reducing the space between buildings and causing problems for access of emergency services. This has resulted in an increasing prevalence of fires, which cannot be controlled by the town’s fire service, as the street network has become too narrow to allow ingress of the fire engines.

Interviewee 3 also noted that Darjeeling is in an area potentially subject to earthquakes, so regulations were put in place by the British to limit building to slopes of <30°. Building now occurs on slopes of 60–70°, with obvious implications for safety.

Further examples were raised where development policies were interpreted as being undermined by local officials showing favour to specific ethnic groups or businesses by allowing illegal homes to be built (cf. Interview 10). The dominant rhetoric in the interviews (Nos. 2 and 4) suggested that the legitimacy of governing the Municipality was considered by some to be undermined by ethnic and economic interests, with Interviewee 4 specifically noting the ongoing power held by tribal leaders in Darjeeling. It was stated that a lack of transparency in how the Municipality controls development (and how it is viewed publically) weakens the trust between local people and elected politicians, thus encouraging informal or unregulated development (Interview 8). The result of this is the development of a complex set of interactions between the Municipality attempting to control development, and collusion between local people to facilitate growth (Interview 7).

As a consequence, although planners, NGOs and politicians promote the role of sustainable development, there is little official policy to enforce such rhetoric (Interviews 6 and 8). Sustainable development practices have, as a result, been actioned at a fairly small scale by local NGOs who have attempted to raise awareness and engage local communities to think more sustainably (Interviews 1, 2 and 4). The lack of formal input from the Municipality, however, undermines the development of a critical mass of exponents promoting sustainable development (Interview 3).

The result of these problems is a lack of mandated policy being produced by the Municipality, and limited authority to enforce sustainable development principles within the development arena, meaning that the development of Darjeeling continues in an unstructured manner (Interview 8). It was, however, considered possible to address this issue if the Municipality were to receive either greater funding for planning activities, or gain autonomy, from the West Bengal State (Interviews 3, 6 and 10).

5.2. Infrastructure provision

Interviewees working with community NGOs and the local administration (Nos. 1, 2 and 6) highlighted a disconnection between the need for, and provision of, service infrastructure and the availability of services across the Municipality. Much was made of the rate of population growth, although the main concern raised was the subsequent lack of investment to upgrade the existing service infrastructure in line with that growth (Interviews 2 and 3). Furthermore, it was highlighted that the infrastructure developed by the British in the nineteenth century had received little additional funding to extend its capacity (Interview 6). As a result, there was a variable provision of essential services across the Municipality, with the historic core of the town being fairly well served, and the periphery much less so (this difference described by interviewee 4 as “part of the colonial legacy”). One interviewee, who lived in the periphery, had access to mains tap water on the day of investigation after five days of service interruption – a common occurrence for the periphery.

In addition to a focus on the core at the expense of the periphery, there was a tendency to think in the short rather than long term, with one local NGO officer (Interview 3) commenting, “[infrastructure provision acts as a] band aid process and doesn’t offer long-term solutions”.

This illustrates that despite the continuing growth of the Municipality, services are acting beyond capacity. Consequently, the viability of Darjeeling to cope with additional development pressures is being undermined. A number of factors were identified as influencing this process, the most frequently noted were: a local population disenfranchised from the structures of planning, corruption in both development and political investment structures and a lack of appropriate policy (and funding) to programme development. Some landowners, specifically those of the military and tea gardens, hold substantial control over access to landscape resources and, subsequently, the provision of services. Such a tiered structure of access led to calls from interviewees for greater political intervention to facilitate service parity for the general population. More specifically, water supply and quality, provision of electricity and clear and solid waste disposal were noted as being major issues.

5.2.1. Water provision

A number of interviews (Nos. 2, 3 and 5) discussed the complexities of water ownership in the area noting that the major landowners (the military and tea gardens) restricted access to water sources (lakes, river channels and upland reserves) exacerbating the need to buy-in water. Interviewee 4 also noted the incompatibility between mainstream policy in India and the specificities of life in the hills – the “Million Wells” programme was a flagship anti-poverty programme in India, but in the Darjeeling area, freshwater springs, not wells, are the principal source of water.

Moreover, the impact of water shortages increases in the tourist season when the population rises to an estimated 300,000–500,000 (Interviews 3, 6, 7 and 8). Water quality was also raised as a major sustainability issue. Several interviews (Nos. 6, 8 and 10) stated that the impacts of informal development, coupled with transport pollution and existing water-intensive uses (i.e. growing tea), decrease the quality of the water across the district. Again, this limits the availability of potable water in the area, increasing the drive to invest in an external water supply.

One alternative to this approach proposed the instigation of, for example, more effective and small-scale rainwater harvesting. Interviewee 4 noted the potential for landowners such as the military, who manage large tracts of land, to take the lead in this regard. It was, however, reported from interviewees that they appear to have little inclination so to do. Instead, the Municipality has invested in an expensive infrastructure scheme to pump water up from the valleys.

As noted above, outside the core of the town, the impact of poor provision is seen in the majority of households in the Municipality, where water supplies are intermittent, becoming increasingly unpredictable during dry months and the tourist season (Interviews 2 and 3). One impact of this has been the need to import water from the valleys and transport it to upland areas (see ); a process described in many interviews as unsustainable (Nos. 1, 2, 8 and 10). Interviewee 5 was also of the opinion that in the town of Kalimpong, part of Darjeeling District, there should be enough water to meet the population’s needs, but there were many leaks in the pipe infrastructure which there was little interest in repairing because “a shortage of water is a good way of making money”. Predictably, the lack of formal water access across the District impacts most severely on the poor, who are forced to obtain water from wherever they can (see ).

5.2.2. Electricity supply

Due to the remoteness, lack of space and steep terrain of Darjeeling Municipality, the generation and supply of electricity is difficult. Whilst investment in water-generated power has occurred, there is still an intermittent supply requiring the local population to rely on generators or illegal power connections for a consistent supply (Interview 10). A lack of investment in infrastructure was identified as being central to this process, along with the continually increasingly population placing pressures on a limited system. A further issue raised linked the lack of investment with population change. With much of the increasing population living in informal/unregulated development, and/or not permanently resident in the town, the West Bengal State has resisted providing funding for new electricity infrastructure because census statistics showed only a small official rise in population (Interviews 6, 8 and 10). This results in increasing electricity prices as people attempt to legally, and in a number of areas illegally, gain access to electricity supplies (Interviews 2 and 3).

5.2.3. Waste disposal

A number of interviewees outlined the obvious issue that the growing population increases the need for solid (i.e. rubbish) and liquid (i.e. sewage) waste disposal facilities (Nos. 1, 2, 4 and 6). However, due to the lack of investment in upgrading and increasing the capacity of waste infrastructure, Darjeeling Municipality is failing to cope with the level of waste generated. The capacity of the existing sewage system, designed by the British at the time of the town’s foundation to meet the needs of 10,000 people, has been surpassed many times over, with several interviewees stating that “nobody knows” where sewage now goes – apparently into watercourses, with obvious implications for health (Interviews 2 and 4). Similarly, sewage from new buildings goes straight into open sewers/drains around the town.

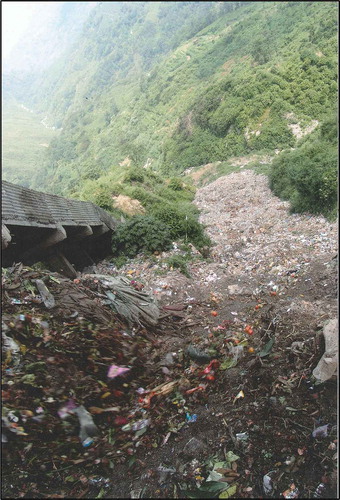

Solid waste disposal is also becoming a major issue. There is insufficient capacity within the Municipality at present to manage the disposal of solid waste, so rubbish is despatched down “the chute”, effectively an enormous pile of rubbish running down the side of the hill at one end of the town (Interviewees 2 and 4; see ).

Figure 7. The rubbish “chute” in Darjeeling town.

In many other parts of India, informal waste recycling is a substantial source of employment (cf. Jain Citation2003; Gill Citation2010), and NGOs have tried to promote a similar solution in Darjeeling (interviewees 1, 2 and 3). The Municipality, in contrast, are keen to develop a recycling treatment plant, with an obvious cost, which would also need additional road infrastructure to service it (Interview 6). There is, at present, little hope of the size of investment necessary to facilitate such development. Nevertheless, Interviewee 7 stated that “every 5 years”, projects to implement solid and liquid waste management were designed by expensive consultants from Delhi, Bengaluru or Mumbai, “with no knowledge of the local context”, meaning that implementation of these projects was impractical. One suggested response to the impact of the lack of waste infrastructure was to situate the dialogue for improvement at the regional level. However, it was suggested that, once again, such a debate would be subject to the marginalisation of the Municipality by the West Bengal State, who appear to characterise the development issues in Darjeeling as “rural”, and therefore less politically important, despite its role as a regional centre. Interviewee 5 stated that he had suggested that the Darjeeling area be included in infrastructure/disaster planning carried out by the North Eastern Council – the agency which manages economic and social development in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura (North Eastern Council Citation2013). This request was turned down “for political reasons”.

Across the different types of infrastructure provision, there appeared to be a substantial gap between the types of low-cost solutions (rainwater harvesting, small-scale recycling) advocated by NGOs and the solutions pursued by the Municipality (water pumped up the valley from rivers, large-scale recycling plant). This focus on large-scale, “flashy” schemes by politicians is perhaps a universal problem, but is a facet of the powerful political context that constrains opportunities for more sustainable development in Darjeeling (Interview 10).

5.3. The overwhelming constraint of context?

The preceding subsections discussed a range of issues identified by interviewees, centred on uncontrolled population growth (with concomitant development) and severe problems with infrastructure provision. If these issues are not addressed, the future development of Darjeeling will take it beyond the carrying capacity of the natural environment to support and supply services for the local population. Interviewees also identified possible solutions to some (though not all) of the issues in Darjeeling, so why is it that they persist? This paper argues that the twin contextual constraints of (1) a lack of room for expansion of the town, and (2) intense political contestation in the area; prevent more sustainable approaches from being implemented.

The location of Darjeeling on a ridge in the mountains of northern West Bengal, surrounded by privately owned tea gardens, military-owned land and protected forest areas, means there is essentially no land available for expansion. As discussed above, this has resulted in building at very higher densities and heights, on even steeper slopes, placing additional pressure on infrastructure and creating potential safety problems. One interviewee indicated that he had developed plans for satellite towns in the areas around Darjeeling Municipality, on tea gardens which are less economically viable and hence potentially available to purchase (Interview 7). These plans were rejected by administrators in the Municipality and District due to the lack of infrastructure to serve such towns, and the lack of funding to provide such. This lack of funding was ascribed by virtually all interviewees to the second, perhaps even more constraining, contextual issue – the political contestation in the area (Interviews 6 and 10).

Interviewees (Nos. 8, 9 and 10) told us that the Municipality of Darjeeling is a marginalised town within a marginalised district, within a marginalised state. It was felt although the years of Communist rule in West Bengal (1977–2011) had “changed the focus away from Kolkata [the State capital]” (Interviewee 5), at the State level influence and funding are (perhaps naturally) still focussed on Kolkata. It was also reported that Siliguri, the town in the plains within the District of Darjeeling, dominates. This led to very strong feelings, with one NGO fearing that if present trends continued “our [Gorkha] history will perish”. Strong sentiments were evident in a number of interviews (Nos. 3, 5 and 10) stating that there is a clear dislocation between the needs and priorities of Darjeeling as a Municipality and those of the West Bengal State and Darjeeling District. This manifests itself in a fissure between State and District mandated-policy that is considered unrepresentative of the needs of Darjeeling Municipality (Interviews 6 and 7).Footnote23

In addition to policy which is insufficiently cognisant of the area’s needs, the main effect of this marginalisation is a financial one – the Municipality is perennially short of funds for infrastructure and the recruitment of staff needed to prepare and implement urban planning strategies. In relation to the latter, even if the municipality can afford to take on new employees, the state government has to approve all new recruitment, something which they are apparently both reluctant and slow to do (Interview 6).

Frustration at the political marginalisation has manifested itself in the growing discontent with the West Bengal State and led to the periodic calls for a federal separation of the “Gorkhaland” hill area, centred on Darjeeling Town (Munsi Citation1980). Within this debate the lack of State funding is seen as a clear indication of the separation of development objectives between the state and Municipality. The most recent of these led, in 2011, to the creation of the GTA, a semi-autonomous body within the state of West Bengal. Interviewee 10 raised this issue on several occasions, indicating that a growing resentment towards the West Bengal State is increasingly manifesting itself across the uplands. The degree of autonomy remains insufficient in the view of a significant proportion of interviews, and indeed the wider population, as several demonstrations demanding full autonomy were witnessed during the process of data collection.

At noted in Section 3, this paper does not wish to comment on the desire of the people of the Darjeeling hills for independence, due to the complexity of the politicised nature of Darjeeling and the uplands (Subba Citation1999; Sarkar Citation2012). It is, though, of equal important to note that continued demands for autonomy cause, according to interviewees, two ongoing problems.

First, it limits opportunities for a positive dialogue to occur between the Municipality, the District, the State of West Bengal and major landowners (Interview 8). This means that Darjeeling Municipality has, thus far, had a limited influence on such plans as there is for future strategic development, so policies in place at the State level do not reflect the particular circumstances of the hill area. Second, one interviewee discussed how sometimes “the focus on autonomy takes over all other considerations – there is a view that statehood will solve all the area’s problems” (Interview 4). This pursuit of an autonomous federal unit within the Indian Union was seen as the primary aim of local politicians, meaning that, in the opinion of one NGO interviewee, they have not done as much as they could to encourage, for example, participation in governance by local people.

These issues notwithstanding, it seems that the demands for autonomy in the area are unlikely to subside in the immediate future – as one local politician told us, “you have to talk about Gorkhaland if you want to exist politically in Darjeeling”. This means that, returning to the conceptualisation of constraining contextual factors limiting the scope for more sustainable development (see ), the tight physical constraints on growth in Darjeeling, together with the political problems discussed hereto, effectively limit the scope for path-changing efforts in the town. This illustrates the difficulty in identifying how the various governmental, NGO and private actors seeking to effect change can be successful, suggesting that Darjeeling will continue on its present, unsustainable, path.

However, it is important to make a contribution to suggest how Darjeeling, or areas with similar powerful constraints, might ultimately break what has been called in this journal “a vicious cycle of poverty, sociospatial exclusion, irregular land use patterns and slum formation in environmentally sensitive areas” (Keivani Citation2010b, p. 11). As has also been observed in this journal, working towards more sustainable urban development requires that we as academics, practitioners and researchers answer “two key challenges... the challenge of ‘the vision’: do we know what ‘the sustainable city’ is? and the challenge of change: do we know how to bring about ‘sustainable urban development?’” (Williams Citation2010, p. 128–129).

First of course, the discussion presented in this paper is focussed not on a city but on a comparatively small town – but, as noted above, the majority of the world’s population continues to live outside of megacities, so there is a need to consider sustainability at a range of settlement scales. Second, these questions are clearly very well put, but for the purposes of this paper, it is important to nuance the second by adding ... within present constraints. There is clearly an important role for neutral observers to encourage long-term “free” thinking and to try and break out of existing paradigms, but we also believe that the academy and journals, such as this, have an important role in suggesting evidence-based solutions, which might be implemented in the short to medium term. To that end, in the following penultimate section, the paper tentatively suggests ways in which changes could be made in Darjeeling within the present constraining context. As will be seen, these suggested changes are of broader relevance, and could be seen as representing good practice for other areas where governance tends to be top-down, and where the institutional capacity for top-down urban planning and governance is lacking.

6. Is there a way forward for Darjeeling?

Darjeeling was established by the British colonial rulers as the summer administrative centre for the state of West Bengal, with an intended population of 10,000. The town now has a population in excess of 10 times this, which increases by more than 200% when seasonal populations are taken into account. To cater for this hugely increased population, a great deal of informal and unregulated built development has taken place, putting great strain on the infrastructure of the town. Darjeeling’s infrastructure is now considered to be unable to cope with such an increase, with resulting patchy provision of water and electricity and solid/liquid waste being disposed of in natural resources around the town. New strategies are therefore needed to help plan and accommodate the existing and growing population of the town in a more sustainable way and develop more sustainable approaches to infrastructure provision.

Despite the complex interactions and intersectionality of the barriers to sustainable development noted previously, it is possible to propose alternative approaches to urban development in Darjeeling, which could promote a more dynamic, and proactive, process of urban sustainable development. In light of this, the following recommendations are made with the caveat that institutional change, as reflected in the political context and attitude of key stakeholders is at best slow, and in practice, static in Darjeeling. This potentially limits the application of sustainable development in practice, but must not restrict the ability of agencies to continue to try and effect economic, social and environmental change.

The key recommendation of this paper is to suggest that there is a need to move from a top-down, professional/investment-led approach to planning and infrastructure provision towards a bottom-up, community-led approach. The successful application of the 74th Amendment Act provides provision for such a process, however, in reality, its application is subject to a number of the socio-economic and political influences discussed in this paper, with Interviewee 4 noting the politicisation of the ward committees introduced under the 74th Amendment. This would begin to address a problem in Darjeeling, which is common across the world: short-term thinking on the part of local people and politicians. Several interviewees also noted that a short-term perspective persists in the ways that the local community views development. Similarly, a number of interviews, including current and former members of the Municipality council (Nos. 6 and 10), raised doubts over the ability of the local government to manage the needs of the area. They questioned whether the cyclical nature of government (tied to elections) and the consequent timeframes of office for elected officials, especially when viewed along ethnic or tribal lines, actually facilitate a more effective form of governance. Giving the local community a greater say in the governance of Darjeeling could both foster more active engagement in thinking about the future, and help mitigate the problems of political churn.

Dealing with urban planning first, limiting unregulated urban development is of critical importance. The creation of a municipal plan for Darjeeling, along with the capacity to implement it, would be the ideal state. As noted above though, there is not the financial or institutional capacity to produce or implement a strategic plan for urban development in Darjeeling. Analysis of interviewee responses also suggests that a revised approach to policy production is needed that engages relevant NGOs, communities and political groups at the municipal level. It could also be noted that the creation of a sustainable programme of development would not address the full extent of growth issues seen in Darjeeling. A strategic plan would help to guide development, but it would also require effective buy-in from all relevant stakeholders.

To facilitate a shift from the existing top-down infrastructure provision approach, through the 74th Amendment Act, NGO and elected officials identified the prospect of developing programmes to improve community engagement and raise awareness of sustainability – several NGOs were working on schemes to encourage recycling or composting of food waste (Interviews 1, 3 and 4). However, to successfully broaden the scope of these initiatives, it was suggested that political will was needed to provide the legitimacy needed for local populations to become engaged (Interview 10). This is of course critical, given the constraints on the power of NGOs (particularly in Darjeeling, where the NGOs in operation are relatively small) to effect widespread change. If “the government” at local levels could be seen to support sustainability programmes and facilitate better planning, it was hoped that participation would become more effective (Interviews 2 and 4). To achieve this, an increased and more effective dialogue is needed between Municipality (and ideally State) officials, NGOs and local people. Willingness is also therefore needed from all actors to ensure this occurs. It has also been suggested that improved education, beyond the existing remit of NGOs, would enable a more explicit understanding of sustainability issues to be debated within local communities.

As implied above, the need for more community engagement in issues around urban development is not unique to Darjeeling, or indeed to India or the “developing” world. One interviewee noted, “the legislation for participation” in governance is in place in Darjeeling, in the form of ward committee, but “it is rarely followed through”. He observed that “resistance to participation comes from fear of transparency... there is a common view of participation – a focus on the middle-aged, male and wealthy”. These words will echo with many, as comparable phrases could apply to participation efforts on the part of many municipalities in the United Kingdom, for example. But there are examples of more meaningful participation in both theory (cf. Healey Citation2006) and practice (cf. Wainwright Citation2009), which provide ideas about possible alternative pathways, and the benefits thereof.

Returning to the proposed interactivity in and , the analysis presented above indicates that the growth and political constraints seen in Darjeeling have a greater influence of development than the established economic, environmental and social triumvirate. Conceptually, this paper thus suggests that a two-stage process of evaluation can be proposed to understand how sustainable urban development can occur. By factoring in the potential influence of the physical and political constraints to growth, we can move beyond the more simplistic assessment shown in . As Wisner et al. (Citation2004) and Williams (Citation2010) propose placing a greater emphasis on context, as reported in this paper, moves sustainability debates forward, providing academics and practitioners with a more nuanced capacity to first conceptualise, and latterly actualise, deliverable sustainable development programmes in situ.

7. Conclusions

Urban development in the town of Darjeeling, as everywhere, is subject to a number of complex and interacting influences, which make attempts to move to a more sustainable form of development challenging. Actors attempting to achieve such a move in Darjeeling, however, are additionally constrained by external contextual factors of such strength and complexity, that breaking out of current unsustainable development pathways can seem impossible.

Since the British first established Darjeeling as a “hill station” for its summer administration, it has been a focus for tourism and economic development, but there has not been a corresponding investment in infrastructure or service provision. Thus, the interaction of economic, environmental and social sustainability is somewhat undermining the progression from theory into practice (Ekins Citation1993; Kirkby et al. Citation1995; Williams Citation2010). Many of the interviews conducted in Darjeeling suggested that the lack of an autonomous Gorkhaland State is the largest obstacle to planning more sustainably in Darjeeling. The analysis presented in this paper suggests that this may appear to be the case as Darjeeling Municipality and District are marginalised within current governance arrangements, but whilst a lack of political autonomy is central to the perceived fractures between the State and local development in West Bengal, simply replacing one governance structure with an alternative does not address the underlying problems of sustainable urban development. Wisner et al.’s (Citation2004) re-conceptualisation of resilience in sustainability planning suggests that replacement is simply likely to lead to a replication of existing barriers and constraints. In order to fully understand the development context in Darjeeling, the interrelationship between the political arenas, the economic development of the area and the physical capacity of the landscape to cope with growth must be made clear. Establishing a Gorkhaland autonomous political unit may lead to a re-evaluation of how urban areas in the Darjeeling Municipality are developed, but this cannot be seen as the sole solution.

Darjeeling is a constantly evolving Municipality, and the ways in which it is changing provide guidance to other areas of how not to promote sustainability in upland areas. It also illustrates the dilemmas faced in upland areas of Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh or Nepal, where attempts to control the evolving development arena suggest that sustainable development is constrained across all Himalayan locales. State actors in Darjeeling therefore need to consider new solutions to the specific issues that are arising in the town. Lower-cost and smaller-scale interventions in the realm of infrastructure provision would go some way in promoting a more sustainable form of development. Moreover, they also need to engage more effectively with local landowners and communities to ensure that growth, that can be classed as appropriate and sustainable, is delivered. Rethinking the governance mechanisms at the local and State levels would assist this process but local populations also need to work with NGOs and landowners to formulate more efficient livelihood strategies (Wisner et al. Citation2004). If these barriers can be addressed, then the approach to sustainable development, suggested in , will provide a greater reflexivity for planners and government to effectively integrate evaluations of the physical and political contexts into development plans.

In a wider sense, the development constraints visible in Darjeeling replicate those seen in India’s growth debates, and specifically those present in discussions of mega-cities. The analysis presented above thus provides additional evidence that the politicised nature of development influences the interplay of economic, environmental and social sustainability. Addressing how urban form takes shape in Darjeeling therefore provides a useful insight into the complexities of expansion that can be translated to other upland or marginal areas. Expansion narratives may, therefore, attempt to integrate sustainability rhetoric, as described by Middleton and O’Keefe (Citation2001), yet the success of such applications should still be considered contextual. As a result, the evidence presented in this paper can be contextualised in two ways; first, it highlights the complexity of development at the local or site-specific scale, whilst, second, highlighting the need to reconsider the parameters of broader sustainable development debates.

Fundamentally, Darjeeling is at a critical point in its existence. As a location with a very specific colonial and post-independence history, and currently engaged with calls for further ethnic autonomy, the area has a legacy of change. The outcomes of the calls for autonomy could foster a renewed vision for a sustainable form of urban development. However, all those involved in the town should not identify this as the only solution for the future. Greater engagement and awareness raising, the development of a formalised strategic investment programme and greater dialogue between stakeholders would, potentially, offer more realistic prospects of achieving urban sustainability. Darjeeling must therefore draw on the knowledge of local populations to shift the emphasis of development away from simplistic assessments of economic, social or environmental value individually to ensure that development activities effectively encompass sustainability principles. There is also scope to apply such assessments to other upland areas to establish new sustainable investment processes across marginal landscapes. If this can be achieved, then opportunities will arise for more sustainable practices to become normalised in the development arena of Darjeeling.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Urmila Jha-Thakur (University of Liverpool) and Surman Rai (Life and Leaf) for their invaluable assistance in undertaking the primary research of this paper. Finally, we are grateful for the assistance of all the contacts and participants in Darjeeling, Kalimpong and Siliguri for their insightful commentary.

Funding

We would also like to thank the School of Environmental Sciences (University of Liverpool) for Pump Priming/Start Up financial support.

Notes

1. Comparable debates over ethnic autonomy, state funding for upland development and the overexploitation of resources are visible in each of these locations (Portnov et al. Citation2007).

2. The framing of development may differ in Sikkim or Himachal Pradesh compared to the constraints placed upon Darjeeling. This does not though imply that growth is sustainable across these upland regions. For a more in-depth discussion of the development of other hill stations, see Singh and Mishra (Citation2004), Bingeman et al. (Citation2004) and Peet and Watts (Citation2004).

3. These are also referred to, inter alia, as poles, factors, components, pillars, rings, and legs. For the sake of brevity, we use aspects from here onwards.

4. The position of executive power bestowed on Darjeeling by the British still permeates the identity of politicians and people in the uplands, and has been partially, at least, responsible for a section of the growing calls for autonomy from the West Bengal State.

5. Consequently, Darjeeling is placed under excessive development pressures compared to other upland towns, which do not act as the central administrative, economic and employment centres.

6. Other indigenous ethnic groups include the Gurung, Tamangs, Lepchars, Bhutias, Sherpas and Newars (Tamang et al. Citation1988).

7. The 74th Amendment Act (1992) established a statutory provision of Local Administrative Bodies as a third tier of administration in urban areas to ensure constitutional validity of urban local bodies (ULBs), and aims to broaden the range of powers and functions of municipal governments. Prior to the 1992 amendment, local governments in India were organised on the basis of the ‘ultra vires’ principle [beyond the powers or authority granted by law] and the state governments were free to extend or control the functional sphere through executive decisions without an amendment to the legislative provisions (Mathur Citation2007).

8. The paper does not draw on supplementary planning or development documents, except where specific reference has been made to such documentation by interviewees. There was also a lack of supplementary evidence as a fire in the municipal buildings in 1996 destroyed the archive of planning documents for the area. No digital copies were available. Interviewee commentary on the focus of development strategies is used throughout with triangulation from a number of interviewees.

9. Several interviewees made reference to the issues surrounding the calls for an autonomous Gorkhaland State. Where these issues are deemed relevant, they are reflected in the text; however, a broader assessment of the complexity of the calls for autonomy is not attempted in the paper.

10. Throughout the following sections, references to the numbered interviews, e.g. Interview 1, indicates commentary attributable to specific individuals. Where more than one number is shown this illustrates consensus between a number of interviewees.

11. Accurate figures are very hard to obtain, as the transient population is not counted in the census, which is an issue in itself.

12. Reference was made to the 74th Amendment Act by respondents who blamed development management constraints on the West Bengal Government’s reluctance to allow the Municipality to effectively manage its own resources.

13. Interview conducted on 1 April 2013 in Darjeeling.

14. Ibid.

15. Interview conducted on 31 March 2013 in Darjeeling.

16. Interview conducted on 1 April 2013 in Darjeeling.

17. Interview conducted on 5 April 2013 in Kalimpong.

18. Interview conducted on 4 April 2013 in Darjeeling.

19. Interview conducted on 30 March 2013 in Darjeeling.

20. Interview conducted on 4 April 2013 in Darjeeling.

21. Interview conducted on 6 April 2013 in Siliguri.

22. Interview conducted on 5 April 2013 in Kalimpong.

23. The historical contextualisation of the calls for an autonomous Gorkhaland political unit outlined in Section 3 frame these tensions.

Bibliography

- Acharya S. 2009. Consolidating Nepali identity: a cultural planning perspective. In: Subba TB, Sinha AC, Nepal GS, and Nepal DR, editors. Indian Nepalis: issues and perspectives. New Delhi: Concept Publishing; p. 185–195.

- Basiago AD. 1999. Economic, social and environmental sustainability in development theory and urban planning practice. Environmentalist. 19:145–161.

- Bhattacharya B. 1992. Urban tourism in the Himalaya in the context of Darjeeling and Sikkim. Tourism Recr. Res. 17:79–83.