Abstract

Delimiting conservation areas has been a vital policy influencing the security of the land. Regarding the construction undertaken in Taiwanese national land planning, most conservation areas are located in nonurban areas. However, numerous conservation areas exist in urban areas, particularly in Taipei, the capital of Taiwan. Because of the national parks in the city, abundant natural resources exist in Taipei. However, land is limited, and the level of stress on the environment is increasing in the city. Moreover, conservation policies are influenced by multiple stakeholders with distinct historical backgrounds. Conflicts have occurred during land development processes because of the related contradictory laws and policies and the unclear definition of urban conservation areas (UCAs). Thus, in this study, we traced the etymology of UCAs to establish an accurate definition, and by reviewing related news events and examples of ecological cities, we analysed the varying attitudes among stakeholders. Observing the land use and Taipei City public policy regarding UCAs enables connecting practical operations to relative definitions. Finally, we suggest that implementing a grading system for UCAs is necessary to avoid controversy and increase the practicality of public policy.

1. Introduction

From dispersed to nucleated settlements, the evolution of civilisation has progressed. People typically seek a more developed city. However, according to a review of urban theories from the nineteenth century, the concept of a garden city, which represents a type of utopia, prevailed during a key period of urban history, especially in the initial period of the twentieth century. In reality, examples of garden cities are few. In constructing of a garden city, green belts and agricultural areas are arranged around the city to prevent urban sprawl. However, the stress of population increase hinders the realisation of this idea. Nonetheless, green land and urban conservation are central to creating an ideal city. Responding to the appeals of the public, urban authorities in Taiwan have authorised the construction of additional parks and open spaces under the Urban Planning Act.

The traditional theory of urban planning regards urban conservation areas (UCAs) as a type of land use on which the population stress is low. According to the Urban Planning Act of Taiwan, UCAs are needed to protect Taiwan’s environment and maintain natural resources and ecological functions. Going by this definition, any development can potentially affect these goals by disturbing the environment, particularly large-scale developments established to promote the economy.

Restrictions on the private owners of lands coming under UCAs are unfair because the development right for privately owned land should not be taken away (Dowie Citation2009). Therefore, several provisos have been implemented to limit these restrictions. The Enforcement Rules of Land Use in Taipei City provide numerous approaches, including additional conditions to allow 17 types of land use in UCAs, such as the high-pressure storage of hazardous products and materials. In addition, land-use restrictions on military or religious property are less stringent. Because the land prices in Taipei continue to increase, construction companies have considered modifying conservation areas to increase the economic value of the land.

To prevent this trend, the local government of Taipei adjusted policies to convert the role of UCAs from passive land to active land, meaning that certain areas were defined as leisure areas. According to the Taipei Green Guide Plan, UCAs are connected to the public transportation system and equipped with hiking facilities and trails. Thus, the public can actively use these areas, which are a valuable resource for environmental education. However, the government has conceded ground in several key cases involving modifying numerous UCAs, a fact that has caused concern regarding the applicability of the policy. Thus, the question of how to accurately interpret the term ‘UCA’ arises. This article expounds on related policies, detailing in-depth interviews and a case study.

2. Literature review

2.1. The ideological trend of garden cities

In the book entitled Garden Cities of Tomorrow (Howard Citation1902), three approaches solving the problem of urban sprawl are offered: (1) disperse the urban population; (2) establish a new town that integrates the specialties of city and country; and (3) change the system of land use. After this book was published, a garden city was defined as a city designed for promoting health, life and industry, and one that is surrounded by a perpetual agricultural zone. In addition, it is specified that the scale of the city must be restricted to ensure that residents can conveniently access rural areas (Ahrentzen Citation2008; Yu Citation2010; Benton-Short & Short Citation2012).

Green town plans in the United Kingdom and North America were inspired by the concept of a garden city, in which a green belt was defined as the junction linking the city and country. Howard (Citation1902) conceived a novel city pattern that divided living and industrial areas but combined living and business areas to overcome environmental damage and urban sprawl (Ahrentzen Citation2008). Richert and Lapping (Citation1998) indicated that Howard’s key ideology was to develop a type of town plan that is markedly flexible and compliant with the demands of residents. The purpose of a garden city is to become an organic community.

The idea of the garden city was extended to the concept of a utopian city, which is a type of city merged with nature. The notion of bioregion areas is emphasised by the city planner, and it is regarded as the first step in planning a city by investigating the surrounding natural resources. All of these references indicate the value of integrating cities with nature and eliminating urban sprawl. A city must be improved to enable residents to live in the ambience and landscape of the countryside (Kendle & Forbes Citation1997; Benton-Short & Short Citation2012). These considerations have influenced the urban planning in Taiwan and the arrangement of protected areas within the city, which are called ‘second nature’, a space for transition between the city and the surrounding natural environment (Yang Citation2001). The concept of second nature leads to the beginning of an ecological city and may provide the platform for achieving urban sustainability (Keivani Citation2010).

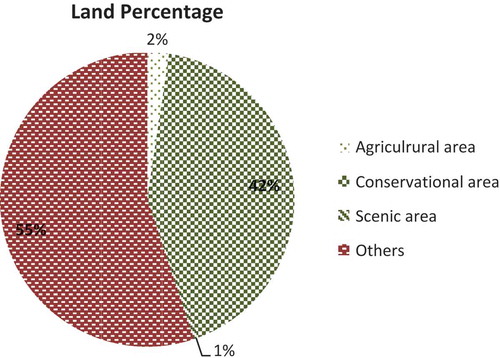

Most urban planning in Taiwan was originally initiated by the Japanese, who introduced the concept of the garden city to Taipei and the surrounding cities. Zhonghe and Yungho, satellite cities of Taipei, were both designed as garden cities; however, the actual land use there differs greatly from the initial plan in terms of population stress. Moreover, Taipei City, located in the Taipei Basin, is surrounded by hills, which may not be suitable for dense development. Thus, the Japanese designated the hills as UCAs, agricultural areas and scenic areas. Consequently, the percentages of UCAs, agricultural areas and scenic areas together account for almost half of the total land area in Taipei ().

2.2. The shape of protected urban areas

Policies for developing protected areas have been adopted worldwide. The reasons for designating protected areas might include protecting historical landmarks, maintaining an ecological environment and preserving particular species. The key intellectual development leading to establishing protected areas is the recognition that ecological dynamics cannot be separated from human dynamics (Liu et al. Citation2007; Folke et al. Citation2011; Kareiva & Marvier Citation2012). Through implementation of such policies within cities, the concept of urban conservation has emerged. Depending on the characteristics of different cities, the focus of UCAs may differ. For example, constructing greenway networks in the United States has been widely accepted as a system for establishing UCAs. Greenways emphasise the value of landscapes, public transportation, pedestrian systems, public spaces and the conservation of species (Bryant Citation2006). Furthermore, a study conducted in Seattle revealed that UCAs can restrain urban sprawl (Robinson et al. Citation2005). The Netherlands promotes Green Heart as the principle of urban construction. The concept of Green Heart opposes the idea that the urban centre is the core of the city, while conversely suggesting designation of farms as the core of the metropolis, maintaining an open space in the city and constructing an effective public transportation system and diverse space system (Bryant Citation2006). Urban planning theory, pioneered in the United Kingdom, presents a clear framework. Harrison and Davies (Citation2002) reported on the urban conservation policy of London established by the London Ecology Unit. Urban conservation was not only designed to protect wildlife habitats from development, but also to provide an accessible natural environment (Momm-Schult et al. Citation2013).

In addition to natural resources, the focus of UCAs has been extended to cultural heritage, particularly in Asia (Xi & Dong Citation2010). Xi’an, a city in inner China, exemplifies this phenomenon. Xi’an is located at the edge of a desert where desertification is a severe problem. Although the conservation policy of the city emphasises ecological aspects, the abundant cultural heritage of the city compels the urban conservation policy-makers to consider both cultural and ecological aspects. Policies concerning UCAs are often linked to the tourism industry. Lijiang, an old town in China, promotes its heritage as a tourist attraction and, thus, income derived from tourism provides the foundation for conservation (Su Citation2010). Singapore is an example of a garden city featuring an exemplary system in both natural and cultural dimensions (Brand Citation2013). The Singapore National Park Management Unit is responsible for the natural dimension and establishes regulations for developing the green land system. By respecting the original terrain and vegetation, the unit has maintained the diversity of species and landscape in Singapore (Weng & Gao Citation2007). The benefits of preserving cultural heritage have been valued since the 1980s, and therefore, additional financial support for maintaining these areas has been provided (Yeon Citation2006).

According to a review of policies concerning several UCAs, certain development policies in Taiwan are similar to those in Singapore, particularly in Taipei City. The development stress involves multiple areas, which include developing national parks, tunnels, religious areas, leisure areas, historical streets and military land. Conservation areas in the city involve the dilemma of development or conservation (Kareiva et al. Citation2008; Kareiva Citation2012), implying that effective measures and clearer orientation are necessary. UCAs in several cities worldwide incorporate concepts that transform resources maintained in the conservation areas into the energy for economic growth. Owing to the policies implemented to conserve such areas, the liveability in these cities has been enhanced. Consequently, the orientation of UCAs in Taipei is vague and the modification of UCAs should be reassessed.

3. Research method

This study was conducted to understand the historical background of UCAs in Taipei according to a literature review. By conducting interviews with the stakeholders, we can clarify the actual controversy and conflict. In addition, a review of public policies implemented throughout history can facilitate interpreting the conflict and determining a possible compromise. Therefore, a qualitative method was adopted in this study. Babbie (Citation2012) defined qualitative methods as the mode of observation that includes experiments, survey research, field research, unobtrusive research and evaluation research. This study involved a literature review (), a case study and in-depth interviews.

Table 1. Definition of the problem and sources.

The relevant literature reviewed primarily comprised news events and public policies, and the interviewees belonged to one of four groups: government authorities (code starting with G), environmental groups (code starting with E), community citizens (code starting with C), and construction companies (code starting with D) ( and ). The selection process for the interviewees comprised three steps. First, relevant news was collected to determine the organisations involved in UCA-related events. All environmental groups mentioned in the news that protested against governmental policies on developing UCAs were identified, as were the government authorities listed as the main policy-maker and executor. In addition, community citizens involved in the UCA protection and two construction companies that launched projects in the UCAs were included. Second, we ascertained whether the organisation was willing to be interviewed, and finally, we assessed whether the interviewees could describe the position of the organisation. After these three steps were completed, related questionnaires were posted to the participants.

Table 2. Interview targets.

4. History of conservation policies in Taipei City

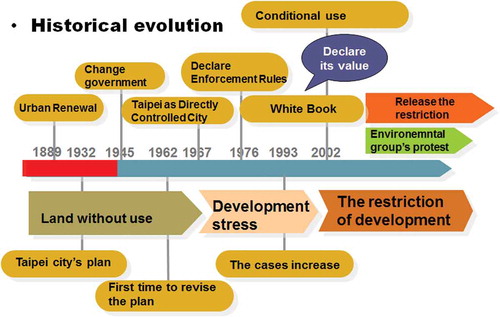

The history of Taiwan conservation policy was identified according to three periods: the period in which UCAs were considered useless land, the period in which the value of developing UCAs was recognised and emphasised, and the period in which UCA development was actively advocated ().

4.1. Abandoned lands

A conservation area in Taiwan is defined as a zone allocated for conserving land, soil and water; maintaining natural resources; and protecting ecological functions. This definition, as specified by law, describes the active goals of a conservation area. However, according to a review of zoning history, conservation areas are defined as abandoned areas that have high development costs. According to the opinion of one interviewee who had worked in urban planning area for several years,

The purpose of delimiting conservation areas is to protect the environment, a goal that can currently be accomplished using satellite maps and geological surveying. However, this was difficult in the past without the availability of advanced technology and also because of limited staff available for urban planning. How did [conservation areas] become localised? Considering that urban development is an irreversible process, unused lands could be designated as temporary conservation areas. These areas may be changed in the future if development is necessary. (G1)

The history of urban planning in Taipei can be dated to 1889, the Japanese colonisation period. The Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan established a committee to survey and draft plans that were announced in 1905. However, because of the rapid population increase caused by the relocation of Japanese to the island, the plan was revised in 1932. The scale of Taipei was expanded to four times the original scale, and the Urban Planning Act was subsequently enforced.

In 1945, following the relocation of the Republic of China government to Taiwan, the rapidly increasing number of political immigrants resulted in uncertainty regarding the urban planning in Taipei. The public facilities constructed during the Japanese colonisation period were unable to support the swollen population. Thus, methods for helping immigrants to settle in became the principal topic in urban planning in the 1950s after the amendment of the urban plan. The new version of the urban planning regulation master plan, conforming to the European urban planning concept and adopted in 1964, is described as follows.

On 1 July, 1967, Taipei was designated as a direct-control municipality; its boundaries were extended from 67 to 272 km2 and it contained a population of more than 1.5 million people. Because six new towns were included in Taipei, the master plan was revised, and new zoning policies were fully implemented in 1968. Subsequently, six new districts established their own land control rules (Chang Citation2007). The Enforcement Rules of Urban Planning Law for Taipei City were announced in 1976, and a land-use zoning rule was declared in 1983; thus, Taipei was the first city in Taiwan to implement zoning in urban planning policy and the first to adopt carrying capacity control. The rules were first adopted in the subareas of Taipei and subsequently extended to the city centre. The hills in Muzha, a district in the suburbs of Taipei, were the first target for which the concept of carrying capacity was introduced in the associated plan.

Taipei was more advanced than any other city in Taiwan. However, conservation areas had not been included in the rules or related laws established by the Japanese. The Japanese government used scenic, aesthetic and fire prevention areas to present the concept of conservation areas. In 1939, only cultural areas were included in the laws implemented by the ROC government. This raises the question as to why both authorities disregarded the importance of conservation areas. Perhaps the need for development was not pressing and, thus, restricting land use was not emphasised. By the end of the 1950s, the increase in population compelled the government to revise the Urban Planning Act and related regulations and develop standards. Chang (Citation2007) regarded the period between the beginning of Japanese colonisation and 1976 as the initial stage of urban planning in Taipei. During this period, the amount of land was sufficient for developers to ignore the increasing value of the Muzha hills. These lands were regarded as abandoned, and designating them as conservation areas was considered unnecessary. Between 1976 and 1983, increasing restrictions were applied and certain lands were gradually designated as conservation areas.

4.2. Increasing stress of urban sprawl

The rapid development of Taipei City occurred after World War II. The arrival of a large number of political immigrants and the establishment of labour-intensive industries between 1960 and 1970 attracted a large number of people to the Taipei metropolis. This was also the first period in which the stress of urban development became a problem in Taipei. After this period, because of the increase in the number of industries between 1960 and 1980, urbanisation resulted in adverse effect on environments in larger conurbations. Consequently, a policy for a new town was established in Linkou, a district in the suburbs of Taipei County (Zhou Citation1999). In 1990, the new town and public housing caused a fraction of the population to relocate from the inner city, which relieved the population stress temporarily.

All of the aforementioned policies were related to the population and infrastructure stress of urban development. However, Taipei remained the centre of consumption, culture and employment. In addition to the need for residential areas, vital economic activities required additional land within the city. Therefore, all of the unused land was surveyed, including the UCAs. Chang (Citation2007) mentioned that the period after 2005 was the ‘deregulation’ step during which the control of urban plans was reduced. The policy of deregulation was adopted and implemented thoroughly, from the central government to local governments. The central government revised the law to designate industrial areas as business areas, which rendered the management of industrial areas in Taiwan uncontrollable. The Taipei City Government also amended the ‘zoning ordinance’ to adopt a negative list for managing the industrial and business areas. In other words, because the level of stress had continued to increase, the government compromised by relaxing its restrictions. Compared with other types of land, UCAs were still subject to strict standards, and several appeals to change the use of UCAs emerged.

Table 3. History of the modification of conservation areas from 1995.

The rules and laws related to UCAs were instituted in 1973 and 1976, respectively. After 1993, revision of the Details of Urban Planning Law for Taipei City caused more organisations to apply for permission to change the manner in which UCAs could be used. According to , 2002 was evidently a key period because of the introduction of the White Book on urban sustainable development and the standard for the conditional use of zoning. From 1997 to 2002, restrictions on UCAs in Taipei were rigidly enforced. However, because of the deregulation policy, in 2004, UCAs belonging to a religious group were used for social welfare, and several universities were using UCAs for educational purposes. In 2010, an officer at a national park was accused of exploiting the land illegally. A construction company used a UCA to build luxury homes, and even building (previously illegal) hotels and restaurants in UCAs became legal. All of these events indicated that the public authorities were compromising in the face of development stress. However, construction companies were reluctant to build on these highly controversial areas, according to a delegate from a construction company. Time and money was required to investigate and stabilise the steep slope, generally defined as land with a slope angle of 20% or greater for a minimum of 30 feet horizontally. According to this delegate,

We may consider the UCA soil and water conservation plan and environmental impact analysis, which would increase the development cost. Therefore, UCAs are not excellent choices. In brief, we prefer to consider lands located by riversides or parks if we want to construct buildings with beautiful vistas. The forest in conservation areas may be a choice for our buildings, but building in the forest is not necessary. The government may agree that the forest should be transformed into a type of residential zone, but the transformation must involve low-density development. Such a situation would increase the cost substantially. (D1)

However, successful situations in which UCAs were developed and preserved do exist, as reported by the same delegate:

Take an example located in historical areas. We own land that does not belong to a heritage area, and therefore, we can cooperate with the nearby land owners to build dwellings according to the related building laws. However, a building on the land was designated as a historical attraction later. This decision was made to preserve local common memory by maintaining the building. We ran this event negotiating with the community for more than 8 years. As you know, that process promoting the case is really a kind of invisible pressure. We and the government both agreed to maintain the heritage area and we own the authority to shift the carrying capacity. (D2)

4.3. Restriction of development in UCAs

To solve the problem of the increasing development for which the land use in conservation areas had been changed, the government adopted positive lists for regulating land use. Furthermore, in 2001, the Taipei City Government invited experts to investigate the reason underlying mudslides caused by a typhoon. The experts concluded that the overexploitation of conservation areas and hillsides was the primary cause of the landslides and floods that occurred. In addition, they suggested that development in these areas be postponed. The following year, the White Book on urban development revealed that the effect on and destruction of natural ecologically sensitive areas were key ecological concerns. In addition, these sensitive areas, including conservation, scenic and flood areas that occupied more than half of the territory of Taipei, should be sustained constructively. However, the government also implemented a standard for the conditional use of zoning, which allowed conservation areas to be used for public benefit but not for commercial use. Allocating conservation areas for appropriate public use may be beneficial, but the definition of public benefit is too vague to delineate areas that may be developed.

However, because of the stress of urban sprawl, both the government and conservation advocates who insisted on environmentally justifiable policies were involved in the allocation process. Both sides presented distinct arguments, and tension occurred between them. One environmental writer urged for development in an urban wetland to be stopped, which prompted the media and the public to discuss the topic. In addition, the Tzu Chi Foundation attempted to transform one of their conservation areas into a social welfare area, which is for the establishment of the installation taking care of the child, disabled people, women and the elderly in 2004, and that decision caused several environmental groups to protest because the area was located in a potential dip slope, a topographic (geomorphic) surface that slopes in the same direction, and development could have destroyed the ecology and safety of the area. Following these events, arguments ensued between both sides.

As a result, the changes and legislation preventing development in UCAs were unsuccessful for two primary reasons. First, the legislation provided flexible content allowing conditional use and providing developers with loopholes. Second, the interest groups and the stress of urban sprawl compelled the government to compromise. The government had to assume more responsibility and clarify the position of different UCAs by using more appropriate assessment methods. Paavola (Citation2004) analysed the EU’s Habitats Directive and experiences and concluded that decision-makers should pay more attention to justice and governance, whereas Fairbrass and Jordan (Citation2001) asserted that supranational EU actors were the major reason for indecision over which level of governance has the most decisive influence on the integration process to protect biodiversity. This reveals that a clear responsible authority guarding the land justly is crucial for managing UCAs.

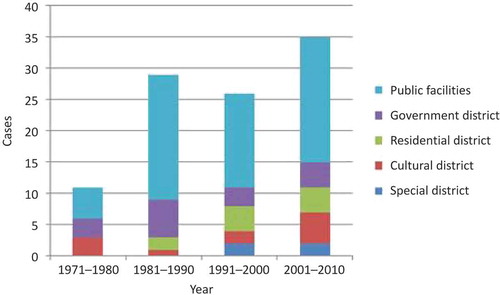

According to a comprehensive survey of the history of conservation areas in Taipei, the restrictions on development clearly tend to be more rigid and the related regulation control changed from negative to positive. Moreover, additional conditional uses, such as public facilities, residential districts and cultural districts, have been accepted by the public. However, one contradictory finding from the statistics indicated that the government converted more UCAs into developing use than any other developer when additional ecological concepts were adopted in 2001 and the White Book for urban sustainable development was announced ().

Figure 4. Number of UCAs in Taipei changed for various uses.

To respond to the expectations of environmental groups, the sustainable development report for Taipei included ecological and sustainable management based on seven perspectives, including the appropriate use for UCAs. Plans for four suburban areas in the hills were included to integrate all conservation areas by using a natural walkway system. All of the plans were attempts to provide areas for leisure use in low-development sections of the city without conforming to the aims of conservation areas. Thus, conservation areas can be supervised by the public by guiding more people into UCAs.

According to one delegate from an environmental group,

‘I completely agree that people should become immersed in nature, meaning they should use the hill walkway instead of the artificial park’. (E1) One governmental delegate said,

One of the directors who oversees the walkway reported that some walkways introduced into the conservation areas will guide people to use the resources effectively. One hill was used illegally, but the situation has been resolved by constructing the walkway. (G1)

All of the interviewees reported that walkways or natural parks may be a suitable use for UCAs. Natural walkways are established according to the natural paths and in consideration of natural corridors and landscapes. Natural walkways may provide several functions, including relief from physical and mental stress, local industry promotion, information for scholarly research, leisure activities and ecotourism, and environmental education (Lin & Qiu Citation2006). However, these potential functions depend on whether UCAs can satisfy both leisure and educational purposes.

5. Results

The conservation areas of Taipei City depend on role transition in the development process. In this study, we explored and reviewed relevant literature and studies. Critical events involving the conservation areas in Taipei during the developmental process were listed based on an annual statement derived from related news (). Furthermore, various opinions of stakeholders were collected in this study to understand and determine the expectations for UCAs in Taipei. The following results were derived from the interviews and the literature review.

5.1. UCAs can be successfully transformed into recreational areas under urban development pressure

The interviewees included environmental group representatives, competent authorities in the public sector and representatives from a community development organisation. The majority of the interviewees agreed with transforming conservation areas into recreational areas. However, they indicated that the degree of transformation should be constrained to prevent interpretations based on public interest. According to one interviewee,

People define development differently. The degree of development is also debated. When development is allowed by law, some people may take advantage of it. This is what environmental groups worry about the most. Legislation for land development will be misused if no overall values or limitations are established, even though the intent itself is good. Therefore, we should conduct zoning planning instead of random planning. (E1)

The zoning concept suggested by environmental groups is an additional challenge in the current zoning of conservation areas. For example, according to present urban planning, a residential area is divided into various levels with distinct plot ratios. The coverage ratio is correspondingly used to control the development strength of the area. However, conservation zones are not subdivided. Certain interviewees reported that the simple conservation zoning conducted in the past was understandable because few environmental databases existed. However, current improved environmental databases can be used to review gentle slope or even flatland conservation zones. For conservation zones, various development norms based on distinct geological and ecological environments must be adhered to. According to one interviewee,

Several environmental groups have proposed a thorough examination of conservation areas. However, conservation areas are among the minimally used urban lands. In many conservation areas, even a low level of development is not permitted. What could be inspected when we visit a conservation area? If development is not allowed, what is the meaning of inspection? A thorough examination was conducted in Taipei and revealed that the conservation areas are flat lands with slope gradients of less than 30%, for which 200 development applications had been submitted. Should all these applications be approved? In my opinion, conservation areas should be divided into several types: natural terrain, hills, and those that were used before the statute. Simply put, conservation areas cannot be treated merely according to their definition, which causes the usage pattern of conservation areas to be simplified. (G1)

The proposal to transform a conservation area into a recreational area was accepted by both environmental group representatives, who had been opposed to numerous development plans over the years, and public sector representatives, who assisted in the legalisation of previously illegal construction in conservation areas. The acceptance by both parties was because they considered recreation as a process of environmental education that requires a low level of development, reducing the conflict between humans and their environment. The problem is that different stakeholders have different understandings of development. Most of the interviewees supported investigating conservation areas and properly introducing recreational activities into a conservation area without affecting conservation zoning.

5.2. Possible tension between urban developers and conservationists can be eased by suitable negotiation

Considering the aforementioned viewpoints of various stakeholders, the conflict between urban development and ecological conservation can be resolved. Buffering factors for easing the tension between them should be increased, particularly for stakeholders who lived in conservation areas prior to zoning. These buffering factors are constrained by regulations governing conservation areas, and the people’s quality of life is directly affected in UCAs. Thus, the regulations for conservation areas should accommodate both urban development and ecological conservation. According to two interviewees,

The conservation area in Xishan is mainly restricted by the National Park Act and Hilly Land Protection Act. For example, many residents have lived in this area for generations. They used to live in small houses, but the number of family members increased, causing housing problems. (C1)

Thus, compromises should be achieved to resolve problems such as indigenous autonomy. Many indigenous people live in conservation areas and may need to hunt, but territorial planning, government decisions, ignore their traditional culture by forbidding their hunting activities. The situation is the same as the question, ‘Should a conservation area be developed or not?’ In my opinion, time is needed for communication and planning before any development or ecological conservation can occur. Without full coordination and mutual respect, no good solution can be determined. (C2)

Numerous residents have realised the value of conservation areas, and their primary concern is guaranteeing their rights and interests established before zoning. The most critical problem in conservation area development is protecting the rights of landowners while not affecting the zoning plan. Historical sites or buildings can be relocated to reduce the pressure of public policy enforcement. However, this solution is ineffective in conservation areas, which primarily consist of natural resources. According to one officer,

We have two conservation areas in Taipei, namely Maokong and Xingyi Road. Maokong is where the development permission system was first adapted. How can I make it legal if I know that certain people are misusing a conservation area? This must be prevented. Nevertheless, we should admit that problems do exist, and we have to find solutions. Environmental groups hope that I can do 100% of the job, which is idealistic. I can do only 30% of the job, and the people in charge can continue. We will complete 80% of the job eventually. I established a new set of game rules. Every owner should follow the rules once they are set. The rules say you have to demolish your house if you are located in environmentally sensitive areas because we must maintain the safety of the residents. Moreover, many problems should be eliminated, including problems concerning drinking water, sewage treatment, garbage disposal, geologic structures, and water and soil conservation. The same system is used for Xingyi Road. We implemented a system and a pattern, but environmental groups stand in our way. They will just impede the problem-solving process. They are not really solving the problems. (G1)

In practical terms, specific methods should be applied because conservation areas exhibit distinct features and are zoned at different times. Moreover, the tension between urban development and ecological protection should be eliminated. The contradiction between urban development and ecological protection has created conflicts between the public sector and environmental groups. The public sector seeks to implement related legalisation, whereas environmental groups question the local city government. To resolve the contradiction and conflict, guaranteeing the rights and interests of existing landowners is necessary.

We observed from the interviewees that both parties are attempting to resolve the problem and improve the quality of urban environments; the problem lies in their differing perspectives. In this study, the pragmatism of the public sector representatives, who relentlessly attempted to achieve gradual improvement, and the earnestness of environmental groups, which endeavoured to protect conservation areas, were demonstrated. Therefore, public policies for conservation areas must be applied in a more dynamic fashion because spaces in a city change over time.

5.3. UCAs protect the environment and connect people and nature

Before public policies are established, the common viewpoint of multiple stakeholders should be determined and the definition of conservation areas should be revised. We interviewed environmental groups, public sector representatives, community citizens and developers. All interviewees agreed that the function of conservation areas is not only to protect the land and environment, but also to benefit society and enhance the relationship between people and nature. Based on the opinions and expectations of the environmental group representatives regarding conservation areas, understanding the main reason for their conflict with the public sector is crucial. According to one interviewee,

Considering the current problems in Taiwan, we must protect the environment if we have to make a choice to address development stress. Protecting conservation areas also means protecting the people. There is a relationship between a host and a guest. The hosts are the environment, whereas the guests are the people. We protect the environment because we want to protect ourselves. We want water and fresh air. As long as we protect conservation areas, they will benefit us one day. This is actually very utilitarian. Although we have to choose conservation over development according to the current rigid system in Taiwan, I think that equilibrium could actually be reached between development and conservation, based on a good resource investigation, if the amount of development does not affect the sustainable development of a conservation area. (E3)

A conservation area, according to environmental group representatives, is to be defined from an anthropocentric viewpoint, meaning that the purpose of protecting conservation areas is to protect people. In their opinion, without a complete environmental resource survey database, such as an overall environmental review, no scientific evaluation of conservation areas can be conducted. However, the cost of developing a complete database is high: the public sector most likely will not agree to create a complete database. Several environmental group representatives adhered to the legal definition of a conservation area, but they also agreed that a new definition is necessary. According to one such representative,

When we talk about conservation areas in Taipei City, we are referring to things like territory security, water conservation, soil conservation, and natural resource maintenance. Is transforming the role of a conservation area possible? I think the answer is yes. For example, you will find that you can actually classify the agricultural land in a certain village of a certain county if you know the planning and mechanism of agricultural land resources, such as priority agricultural land. We have to establish a clear definition. (E2)

Construction companies are aware that conservation areas have development restrictions and value, but they assert that the land surrounding conservation areas is their primary target, because securing land in Taipei is increasingly difficult. When the land surrounding a conservation area is used for development, landowners in conservation areas protest. The originally planned conservation areas are also modified gradually. Regarding the definition of a conservation area, construction company representatives reported that conservation areas should be defined in a manner that benefits the public. According to one construction company representative,

I think the point is that minimal operation should be guaranteed, the operation of the entire ecosystem should be maintained, and human development activities should be restricted. Conservation areas are created according to ecological viewpoint. The cultural point of view involves historical value and considers the public. If the public thinks a place should be conserved, the executive system is obliged to propose a corresponding plan. The meaning of conservation areas is based on public interest. As a constructor, I know that conservation areas cannot be developed directly because they are unsuitable for development. However, we carefully assess whether the land surrounding them has development potential. Both cultural and natural impacts on the environment will be considered. (D1)

We can deduce from the aforementioned interview responses that attention cannot be paid to the value of a conservation area. Instead, additional aspects should be considered, such as the harmony of conservation areas with their surroundings, the conservation of biodiversity in such areas, urban development, and the advantages and disadvantages that might be created during the role transition of a conservation area.

Several basic tasks should also be considered when revising conservation zoning, including the construction of an environmental resource database, the practice and planning of an overall review, the provision of information transparency, and public participation. Generally, the interviewees agreed that conservation areas could operate more flexibly and that balance can be achieved between ecology and urban development or recreation. However, they also indicated that an environmental assessment and review should be conducted first, and the rule of protecting the environment should be strictly followed.

6. Conclusion

Since conservation areas were first established in Taiwan in the 1970s, many proposals for assessing and developing the conservation area assessment methods have been presented. However, few overall assessments have focused on operation management. Nevertheless, numerous relevant studies have been conducted in recent years. For example, Lu et al. (Citation2011) conducted a case analysis of five conservation areas in Taiwan. By observing the adjustment of the operation management performance assessment of these conservation areas, they determined that hardware facilities were frequently emphasised and that labour management was disregarded. In listing the critical events in the development of conservation areas in Taipei, we focused on investigating and clarifying various aspects of urban nature conservation. The following conclusions were drawn from the results of this study.

6.1. The purpose of conservation should be to protect the people

Currently, urban land is mainly divided into residential, business, industrial, agricultural, recreational and protection zones. Most of these zones were created because of human activity and are named after human behaviour patterns. Only protection zones and conservation areas are not reflective of notable human activity. According to relevant laws and regulations, conservation areas are zones with the functions of territory security; water and soil conservation; natural resource maintenance; and ecological protection. The Cultural Heritage Preservation Act indicates that conservation areas were defined to protect historical sites and preserve environmental landscapes. Thus, conservation areas do not correspond to human activities alone; conservation is adopted to protect natural resources and landscapes as well as historical sites. However, laws and regulations are established according to the concept of anthropocentrism. The purpose of natural resource conservation is to achieve the continual political stability of the country. Although maintaining biodiversity is mentioned repeatedly in the literature, the human right to subsistence remains the primary reason for establishing conservation areas. Natural conservation areas are not zoned to benefit other species or ecological resources but to protect human safety. This is the reason that several of the interviewees mentioned ‘public interest’. The purpose of zoning conservation areas is preserving areas where people reside – not only are historical buildings in these areas protected, but specific cultural patterns are also preserved. Therefore, we define the purpose of UCAs as protecting the existence of human life in a city.

6.2. A grading system for conservation areas should be implemented

The contradiction between the interests of the majority and minority has become a common problem in conservation areas. If specific regulations based on the features of conservation areas can be established, this contradiction could be reduced dramatically. According to the Taipei Land Zoning Ordinance, nine types of residential zones, four types of business zones and two types of industrial zones are currently used. The various plot ratios and coverage ratios of these zones are provided in the regulations. However, a single plot ratio and coverage ratio were designated for other zones, such as administrative districts, institute and college districts, warehouse districts and scenic districts. Three types and five types of construction standards were established for agricultural and conservation zones, respectively. Regarding water and preservation zones, the Water Resource Act and the Cultural Heritage Preservation Act, respectively, were implemented. The five construction standards for conservation areas were defined according to the type of land use permitted under certain conditions. For example, community safety facilities, public facilities and public affairs agencies have the highest coverage ratio, whereas agriculture and agricultural buildings have the lowest coverage ratio. The highest coverage ratio is applied after the original buildings have been newly and legally constructed, extended, reconstructed or repaired.

Although the Taipei Land Zoning Ordinance is the most complete law for land-use zoning in Taiwan, no standard grading system based on natural features, such as UCA topography and geology, is used. The conditional use of UCAs without a complete supervisory system may negatively affect the protective function of the original conservation zoning.

6.3. Protection mechanisms should be included in the practice of public policies for conservation areas

Our in-depth interviews revealed that no marked contradiction occurred between the understanding and expectations of conservation areas among the representatives from various units, including environmental protection groups, public sector representatives and community citizens. All interviewees expected UCAs to serve as a barrier or shield during urban development and maximise public benefit. However, in reality, we discovered that the environmental protection groups, public sector representatives and even construction companies often ignore or blame each other for problems related to conversation areas. For example, the process of legalising hot spring areas in Taiwan has created considerable controversy. However, the public sector representatives wish to solve rather than postpone problems. During the regulation of political economics, integrating opinions and balancing the authority of all parties is critical. However, when no event threatens the immediate safety of the people, the public sector has no intention of strictly implementing current legal regulations. The controversy regarding the base of Ciji Enclosed Lake in Taipei City is an appropriate example. The original base is no longer a conservation area, but the public sector cannot prevent developers from using it as a social welfare facility because human safety is not threatened. However, the legalisation of the Maokong Leisure Agricultural Park and the Beitou Hot Springs Hotel indicates the value of local culture. Environmental protection groups seek to implement regulations rigidly, whereas the public sector pursues the possibility of improving the environment in a more flexible way. Methods for reducing the gap between the expectations of these two groups in environmental controversies should be investigated in future studies.

Although the evidence from the policy sector supports the contentions made by various stakeholders, a more complete theory should be subjected to considerably more empirical testing. Reformation of urban planning and legislation related to UCAs is ineffective when the property of the land cannot be understood. In this situation, if the authority cannot manage with disputes, then the importance of renovation and justice may become redundant. Furthermore, the policies used to shape a city should include valuing UCAs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yi-Yen Wu

Yi-Yen Wu is an urban development planner and assistant professor at the Department of Travel and Ecotourism, Tungnan University, Taiwan. He received his BA degree from Chung Yuan Christian University, his master’s degree in Taipei University and his Ph.D from Chaoyang University of Technology. Current research focuses on urban strategic sanitation planning and sustainable urban tourism.

Ching-I Wu

Ching-I Wu is an adjunct assistant professor at the Department of Landscape Architecture, National Chin-Yi University of Technology and also responsible for a Landscape Consulting Corp.

References

- Ahrentzen S. 2008. Sustaining active-living communities over the decades: lessons from a 1930s Greenbelt Town. J Health Polit Policy Law. l33:430–453.

- Babbie E. 2012. The practice of social research. Belmont (CA): Wadsworth Publishing.

- Benton-Short L, Short JR. 2012. Cities and nature. London (UK): Routledge.

- Brand R. 2013. Facilitating sustainable behavior through urban infrastructures: learning from Singapore? Int J Urban Sustain Dev. 5:225–240.

- Bryant MM. 2006. Urban landscape conservation and the role of ecological greenways at local and metropolitan scales. Landsc Urban Plan. 76:23–44.

- Chang GW. 2007. The enforcement and change of zoning institution in the perspective of property rights [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. National Chengchi University. Chinese.

- Department of Urban Development, Taipei City Government. 2014. The query system of urban plan in Taipei [Internet]. [cited 2014 Nov 20]. Available from: http://163.29.37.171/planMap/cityplan_main.aspx

- Dong ZS. 2004 July 9. The first type residential district is attempted to be changed into the conservational area in Yangmingshan. United Daily News, B01. Chinese.

- Dowie M. 2009. Conservation refugees: the hundred-year conflict between global conservation and native peoples. London (UK): MIT Press.

- Fairbrass J, Jordan A. 2001. Protecting biodiversity in the European Union: national barriers and European opportunities? J Eur Public Policy. 8:499–518.

- Folke C, Jansson Å, Rockström J, Olsson P, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, Crépin A-S, Daily G, Danell K, Ebbesson J, et al. 2011. Reconnecting to the biosphere. Ambio. 40:719–738.

- Gian ZY. 2008 April 16. The legalization of hot spring in Yangmingshan. United Daily News. C01. Chinese.

- Harrison C, Davies G. 2002. Conserving biodiversity that matters: practitioners’ perspectives on brownfield development and urban nature conservation in London. J Environ Manage. 65:95–108.

- Howard E. 1902. Garden cities of tomorrow. London (UK): Faber and Faber.

- Kareiva P. 2012. Dam choices: analyses for multiple needs. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 109:5553–5554.

- Kareiva P, Chang A, Marvier M. 2008. Environmental economics: development and conservation goals in World Bank projects. Science. 321:1638–1639.

- Kareiva P, Marvier M. 2012. What is conservation science? Bioscience. 62:962–969.

- Keivani R. 2010. A review of the main challenges to urban sustainability. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 1:5–16.

- Kendle T, Forbes S. 1997. Urban nature conservation: landscape management. Land. 189:4–15. Chinese.

- Lin HZ, Qiu QH. 2006. Public participation and the renovation of walkways-taking the forest in Luodongas example. Taiwan For J. 32:17–24. Chinese.

- Liu J, Dietz T, Carpenter SR, Alberti M, Folke C, Moran E, Pell AN, Deadman P, Kratz T, Lubchenco J., et al. 2007. Complexity of coupled human and natural systems. Science. 317:1513–1516.

- Liu KY. 2007 June 13. The residents protest the hiking way destroyed by the construction company. United Daily News. p. C09. Chinese.

- Liu Z. 2006. March 12. To take a great picture of 101 tower in the hill. Liberty Times. Local version. Chinese.

- Lu DJ, Chao CL, Chuen HC, Kao CW, Chang YL, Chang HY. 2011. Evaluating the management effectiveness of the protected area in Taiwan. J Geographical Sci. 62:73–102. Chinese.

- Momm-Schult SI, Piper J, Denaldi R, Freitas SR, Fonseca MDLP, Oliveira VE. 2013. Integration of urban and environmental policies in the metropolitan area of São Paulo and in Greater London: the value of establishing and protecting green open spaces. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 5:89–104.

- Paavola J. 2004. Protected areas governance and justice: theory and the European Union’s habitats directive. Environ Sci. 1:59–77.

- Richert ED, Lapping MB. 1998. Ebenezer Howard and the garden city. J Am Plann Assoc. 64:125–127.

- Robinson L, Newell JP, Marzluff JM. 2005. Twenty-five years of sprawl in the Seattle region: growth management responses and implications for conservation. Landsc Urban Plan. 71:51–72.

- Su X. 2010. Urban conservation in Lijiang, China: power structure and funding systems. Cities. 27:164–171.

- Weng SF, Gao W. 2007. A Garden City that human being harmonious with the nature: Singapore. The Window of Global Landscape. l30:65–67.

- Xi BJ, Dong J. 2010. Conservation and development of urban space characteristics of Xi’an. J Civ Eng Manag. 27:121–126. Chinese.

- Yang PR. 2001. Landscape ecology in city planning: urban development, landscape change and hydrological effect in Taipei’s Keelung River Basin 1980-2000 [ PhD dissertation]. Graduate Institute of Building and Planning, National Taiwan University. Chinese.

- Yeon B. 2006. Reclaiming cultural heritage in Singapore. Urban Aff Rev. 42:823–850.

- Yu N. 2010. Howard’s tomorrow garden city [Internet]. [cited 2010 Sep 7]. Available from: http://scnews.newssc.org/system/2010/02/05/012572635.shtml

- Zhou ZL. 1999. The issues and law in Taiwanese new town. Human and Land. 189:4–15. Chinese.