?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Urban redevelopment projects persist predominantly within the Downtown central business district of the Kingston metropolitan area. This narrow spatial focus of redevelopment projects and efforts ignores the implication for development of the wider metropolitan area and the national urban structure. Evidence suggests that the efforts put in urban redevelopment have achieved moderate success in a few areas and have failed, in others, to provide the revitalisation and renewal energy needed t\o manage contemporary socio-demographic, spatial and economic dynamics and ensure urban sustainability. Compressing data and information collected over the last 10 years from various pertinent sources the research also draws upon a large volume of intellectual literature. The myriad of negative consequences of the redevelopment efforts since 1907 to date have all ultimately linked to ineffective urban management, lacking both philosophical and technical base. The experiences are valuable tools in improving the future relationship between urban redevelopment and urban development.

Introduction

This article is one of the few versions on the interpretations of redevelopment in Downtown Kingston (DTK), Jamaica. What sets this interpretation apart from the others is its assessment of the consequences of redevelopment in DTK and its association with the development of the wider Kingston metropolitan area (KMA). This is done by undertaking a critical evaluation of the cumulative effects of urban redevelopment projects from 1907 to 2013 and their implications for urban development. Cognisant of contemporary urbanisation dynamics, this article posits a shift from the current city management approach to metropolitan urban management (MUM). The philosophical basis of MUM appreciates the interrelated issues of community participation, property tenure, taxation, capital and resource migration, sustainability and most importantly, the bourgeoning of multiple urban nodes and other non-traditional urbanisation dynamics. Evidence presented suggests that redevelopment efforts within the KMA have been concentrated within the small central business district (CBD) of DTK, ignoring contemporary urbanisation dynamics within the KMA.

The tripartite division of this article begins with a conceptual and contextual background to the development of Kingston, a methodological outline, focus on the locale and socio-spatial morphology. Some empirical data from field research, sequential observation and secondary information are presented and critically discussed. This article concludes with some conceptual and technical recommendations.

Background

Conceptually, this article argues that urban development and redevelopment facilitate primacy by concentrating demographic, socio-spatial and economic investments, dramatically increasing the city’s relative value. Additionally, as the city’s dependency increases, it crosses the threshold for higher level services. Consequently, it should start offering richer opportunities for development, plus an increasing imperative in recognising its ecological importance and position within the national and global urban structure. However, the viability of any one urban centre should not be dependent on, and reinforced by the continuing concentration and reinvestment of development energies at the expense of the national urban structure or economy. If so, then the city is unsustainable, and the resources that support it should be redirected to potentially better uses elsewhere.

Traditional urbanisation forces within the KMA and Jamaica are similar to those observed by Jenkins et al. (Citation2007) in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). They warn that urban primacy within LAC may be slowing to an end, as primates lose their advantage over smaller cities due to new production trends and to environmental and economic problems created by their sheer size. The concentration of economic and political power within the KMA assures its primacy, despite evidence of population decline relative to other urban centres, emergence of second-tier cities and multiple urban nodes. This primacy is assured by multiple urban nodes within the KMA, and not by redevelopment investments within DTK-CBD. The rise in informal economic and spatial activities within the KMA and second-tier cities, concomitant with rising crime, general insecurity and environmental degradation are some of the many threats to the KMA’s dominance. This rise in informal activities in developing countries such as Jamaica is the general trend observed by Keivani (Citation2010) in arguing that the vast majority of the urban populations in these countries are making a living through various forms of informal employment. Informal agents step in to fill the gaps left by the state in various socio-economic sectors. Currently, Jamaica’s informal economic and financial activities contribute ~40% to the gross domestic product (GDP) (ILO Citation2002; De La Roca et al. Citation2006; WB Citation2011; Wedderburn et al. Citation2012). However, other local institutions (PIOJ Citation2012) estimate that this may be as much as 43.5%.

Since 1907, the city of Kingston (1872 to 1923) and later the KMA (1923 to present) have increased in importance as the Caribbean’s largest English speaking city and metropolitan areas. Kingston’s economy and growth were based on port activities (the port is the world’s seventh deepest anchorage). The relaxation of import laws, by the colonial government, saw increases in new business. Between 1921 and 1943 more than 2000 people migrated to Kingston annually, as the plantation economy slowly ended. The economic base has since then been diversified into bauxite and tourism at the beginning of the 1950s and later expanding financial and logistic services since the 1980s.

With a landmass and population of 0.97 km2 and 50,000 in 1907 to the current 475 km2 and 584,627, respectively (Clarke Citation2006; STATIN Citation2011), undoubtedly, the city has grown. Settlement development became more structurally focused after a devastating earthquake and fire in 1907, mainly in the DTK-CBD. Since then, Kingston’s growth has been undermined by poor governance, weak enforcement of planning regulations, mushrooming of squatter settlements, resource transfer, crime and political garrisonisation inter alia. Growth and contemporary socio-demographic dynamics have outpaced socio-physical infrastructure provision, increasing vulnerability to multiple hazards. Consequently, continued investments in physical and socio-economic infrastructure have contributed to primacy and increasing vulnerability. This development paradox is exacerbated by infrastructure works that continue to ignore serious sensitive ecological considerations. The earthquake was but one of a series of hazards that thwarted the development of Kingston during its embryonic stage. It was in 1907 that the first official Downtown Kingston Redevelopment Project (DKRP) was launched by the Mayor and Council of Kingston, Parochial Board of St. Andrew and Kingston General Commission. The plan valued at JMD1.6millionFootnote1 (USD$16,000) included DTK-CBD and involved the implementation of the island’s first building code. This plan saw the retrofitting of structures with reinforced concrete and other modern construction and engineering methods.

Over the past century, the redevelopment of DTK-CBD and the KMA, respectively, has been of growing importance for three reasons; firstly, increasing dependence on its supporting infrastructure and services to sustain other activities in peri-urban space, placing pressure on an ageing infrastructure. Secondly, there is growing concern over socio-spatial expansion of KMA into surrounding residential communities and on agricultural lands. Finally, there is increasing concern about the rise in multiple urban nodes within the KMR and second-tier cities (PIOJ Citation1991; STATIN Citation2011) within the national urban hierarchy. These nodes located north of the DTK-CBD redefine DTK’s primacy by providing broader base alternative urban services. Similarly, second-tier urban centres start to siphon off potential investments from the KMA and other traditional centres.

The burgeoning of second-tier centres and multiple-nodes is of concern for continuing redevelopment of DTK for four main reasons. Firstly, redevelopment efforts since 1907 have targeted the DTK-CBD. However, there has only been growth in northern urban nodes. It is perceived that these nodes owe their rise to capital flight from DTK. Secondly, national economic diversification has accounted for investment in northern tourism base centres. Thirdly, urban crime, fuelled by drugs and political tribalism, coupled with chronic increase in the urban land prices and other urban services make other areas more attractive. Finally, the sustainability of DTK is being threatened by imbalanced government incentives.

These and other urban degeneration processes escalate within the KMA contributing to informality and commercial importance of non-traditional urban nodes. These exist within an environment of ineffective urban governance and management, lacking relevant philosophical base directing development and redevelopment. Though these and other negative contemporary urbanisation effects are symptomatic of the wider KMA, redevelopment and revitalisation efforts and even improved and innovative urban management and governance are concentrated within the DTK-CBD ignoring the wider KMA. This article posits that if these trends are reversed, then the benefits of redevelopment will be inclusive and sustainable. The relationship between redevelopment of DTK and the KMA needs understanding and substantive articulation within development plans, to arrest urban blightedness and promote sustainability within the KMA and its viability as a metropolitan space. MUM, like city management, recognises the city as a coherent whole, but extends this as being an amalgam of different mini cities, with intertwining functions. Their individuality and unique position in contributing to group dynamics are appreciated. Within this philosophical base, primacy is defined in the context of the entire KMA, relative to Jamaica.

Methodology

This article uses archival information, sequential and direct observation, expert and professional interviews, field research and professional discussions to garner pertinent secondary information and primary data. Data collection commenced in 2000, under a consultancy agreement between the United States Aid for International Development (USAID) and the Kingston Restoration Company (KRC) when the first pilot area of the King Street was evaluated. Additional data and information, regarding the redevelopment and development efforts were collected and collated from 2010 to 2012. The Access to Information Act 2004 was used to secure some sensitive financial and security information. Reports and research, maps and project documents were obtained from related agencies and institutions.

A socio-demographic survey of 200 randomly selected households within the KMA and “persons-in-the-street” within DTK-CBD was administered. The questions were a mixture of coded and open-ended items and were administered from January to August 2011. A second pre-coded survey instrument was administered to 50 stakeholders, in August 2011. These stakeholders included 30 private businesses selected randomly (). The other 20 surveys were administered as shown in . These persons and interest groups have been involved in the redevelopment of Kingston in various capacities, the information and data collected from them represent their cumulative response. This represents a total of over 80% of the plans and programmes implemented in DTK (). Additionally, a building survey of 200 buildings was undertaken within the Downtown Kingston management district (DKMD) and the remainder of the gridiron, excluding the waterfront ().

Table 1. Distribution of survey instrument to private business.

Table 2. Distribution of survey instruments to professionals and agencies.

Table 3. Building inventory survey distribution.

The researcher has over 20 years interactive experience and understanding of urban planning within Jamaica and KMA in particular. One key set of information related to history and must not be seen merely as the recollection of events and facts. This is a substantive attempt to understand the past development forces of Kingston, as a precursor to appreciating the present and prepare for the future. Such historical focus ensures the importance of interconnecting events (Harman Citation2008). The urban landscape of Kingston today is a product of historical events and decisions not its cause. It is on this premise that the two last sections of the research are based. The research applied a general critical analysis of all redevelopment plans, with periodic reference to specific projects.

The study area

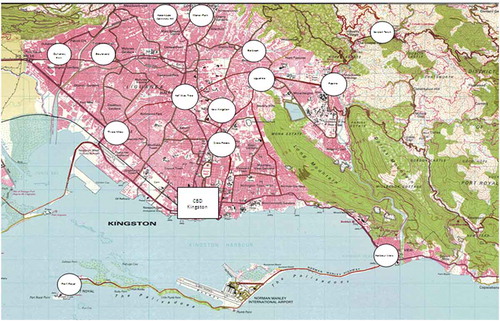

Jamaica is located in the North Caribbean Sea (, lower left). The triangular shape north-south profiled island rises from the sea level to 2256 m in the Blue Mountains (, top). With a land mass of 10,830 km2, and a population of 2.8 million, Jamaica is the third largest English speaking island of the Greater Antilles. The KMA and the KMR have 54% and 60% of the island’s population, respectively. Kingston is located on the south-eastern Liguanea plains, forming a horse-shoe with the surrounding mountains to the east, north and west and the Kingston Harbour opening to the south. The harbour is a major transhipment centre for the Latin America and the Caribbean and encompasses ~26 km2 of navigable water with depths of up to ~20 m, making it the seventh deepest natural anchorage in the world.

Figure 1. The Island of Jamaica showing its parishes and capitals (top), regional location (bottom left) and Kingston and the harbour (bottom right). The KMA is the area shaded as Kingston (bottom right), while the Kingston metropolitan region (KMR) includes all of Kingston, Spanish Town and Portmore. Source: Leslie (Citation2010).

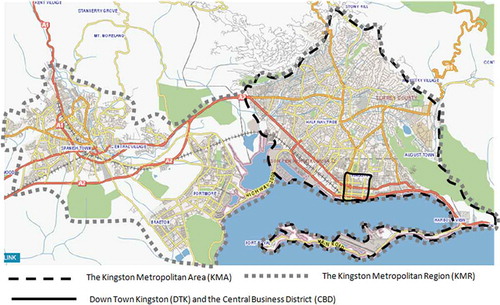

Throughout this article, Kingston and the KMA are used synonymously, unless otherwise stated, while the CBD refers to the CBD of DTK and the KMA (). The KMA has a population of 661,862 within 198,076 households and 190,864 dwelling units (STATIN Citation2011). The KMR () is not legally recognised and include the area classified by the Kingston and St. Andrew Corporation (KSAC) Act of 1923 as the KMA, the Spanish Town urban area and the Portmore Municipality (, bottom right). Together, they constitute an area of approximately 30,000 acres (46.875 km2) with close to 223 squatter and ~65 slum or inner-city communities accounting for close to 36% of the KMR’s population. The changes in the coast line (compare and ) were due to land reclamations to create Portmore (, bottom right and , bottom centre) and the construction of the highway (causeway), linking KMA with Portmore.

Figure 2. The spatial association between the Kingston metropolitan region (KMR), the Kingston metropolitan area (KMA) and the Downtown Kingston central business district (DTK–CBD). Source: Base map from Google Earth and overlay by research

What distinguishes the CBD from the rest of the KMA is its British designed (1733 and 1751) gridiron layout (, and ). The area was planned around Central Parade, an open area in the centre of the CBD reserved for communal and recreational activities. The gridiron measured three quarters (¾) mile in length, half (½) mile in width and covered ~240 acres (0.375 sq. miles). The pre-1700 plan () was further extended in the 1800s () in the north-east and eastern directions in response to increasing urbanisation.

Figure 4. The expansion of the original gridiron (compare and ) of the 1700s to 1897 plan. Source: T. Harrison.

Figure 5. The Kingston CBD gridiron 1702. Source: Clarke Citation2006)

Presentation of findings

Historical dimension of urban development and redevelopment of Kingston

After the Port Royal earthquake in 1692, a pig farm in Kingston was cleared as a resettlement site for earthquake victims. Efforts to rehabilitate and reconstruct the Port Royal city were thwarted in 1703 by a disastrous fire. This was the first effort in urban resettlement. In a series of political and legislative power manoeuvring between 1693 and 1755, Kingston eventually emerged as the capital town (Clarke Citation2006) over Spanish Town. Historical accounts (e.g. Sherlock & Bennett Citation1998; Tortello Citation2006) and archival evidence will implicitly suggest and explicitly show that all political, legislative, physical, economic and financial resources were brought to bear on legitimising the city status of Kingston.

In 1802, King George III granted Kingston Charter as a Corporation, formalising its city status (Bryce 1946) and making it the country’s capital in 1872. In 1923, the parishes of Kingston and St. Andrew (, main image) were merged,Footnote2 making Kingston both a parish and city. Under the Kingston and St. Andrew Corporation Act of 1923,Footnote3 the limits of the city except where otherwise specifically provided by any enactment, by-law or regulation, are divided into four legal boundaries: (1) corporate area, (2) urban boundary, (3) sub-urban district and (3) rural district boundary. Additionally, the spatial limits of KMA are defined in the Town & Country Planning Act 1957, the Parochial Roads Act 1900, the Public Health Act 1985 and the Kingston & St. Andrew Building Act 1908 inter alia. All these legislations differ in their definition of the city limits. The implications of this for urban planning and management are frustrating for local planners in making plans and policies.

Socio-spatial morphogenesis

The physical expansion of Kingston has been restricted by its surrounding step and rugged topography (). This is further exacerbated by building systems, which makes it costly to build on hilly upland terrain and thwarted the rate of physical infrastructural investment. These natural and socio-economic conditions were also contributors to socio-spatial stratification (Anas et al. Citation1998), along ethnic and wealth lines (Sherlock & Bennett Citation1998; Clarke Citation2006) within the KMA. Under these conditions, the urban poor and lower middle classes (mainly African and Asian descendants) were confined to the mangrove plains and less hilly areas, while the rich (European descendants), who could afford to, occupy hilly areas.

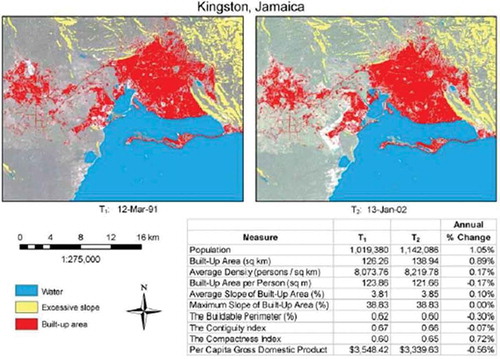

Figure 6. 1991 and 2002 Comparative growth of Kingston metropolitan region. Source: WB (Citation2011).

The pace of Kingston’s growth has been phenomenal () even though modest in the global scale. The World Bank (WB) has identified two concerns surrounding the KMA’s growth. Firstly, the growth is limited by international standards, since other world metropolises are confronting problems of a 6% annual growth which comes to an almost 100% growth in a decade. Secondly, the growth is manageable and can be easily confronted with a general vision for the structure of the Metropolis. A decade of WB Data (Dynamics of Global Urban Expansion, ‘1991–2002) presents population growth of 12% and 10% expansion in built area (), with a decrease in density and domestic product. Further works by Clarke (Citation2006), Tortello (Citation2006) and Sherlock and Bennett (Citation1998), etc. take a more comprehensive look at the historical and demographic dynamics of Jamaica and Kingston in particular. Still, others (Gilbert Citation1996; Brennan Citation1999; Njoh Citation1999; Hardoy et al. Citation2001; Davis Citation2004; Cohen Citation2006; Jenkins et al. Citation2007; and the Un-Habitat Citation2003) present similarities of urbanisation and urban development with similar ex-colonial countries in LAC and Sub-Sahara Africa.

After 280 years of socio-spatial morphogenesis, the area of the KMA is now over 118,592 acres (185.3 sq. miles). Its current spatial form is a mixture of a freeform organic; resulting from a predominantly informal and unregulated bottom-up socio-spatial settlement and a uniform grid (); the consequence of regulated top-down (Al-Sayed et al. Citation2010) rational spatial planning decisions. The freeform organic land use dominates the northern portions of the KMA, as the gridiron that dominates the CDB region dissipates outwards radially.

Primacy and redevelopment

Jamaica’s urban structure follows the rank size rule as defined by Fry (Citation1983), Gabaix (Citation1999), Rashid and Khairkar (Citation2012), Galiani and Kim (Citation2008) and Portnov and Benguigui (Citation2010). The population rank of the urban areas follows the curve, convex to the origin (), as defined by the rule. However, this adherence to primacy rules does not follow that of Zipf, which states, that the size of the primate city (Kingston) must be twice that of the second largest (Portmore) and, three times larger than the third largest (Spanish Town). The KMA is 3.63 times larger than the other three largest cities and 1.5 times larger than the largest 4 and 1.5 times larger than the largest 5 cities. It is also more than 100 times larger than the smallest city and 5, 9 and 11 times larger than the other 3rd, 4th and 5th centres, respectively (). Within the tenets of Zipf’s rule the KMA is described as inhomogeneous (Portnov & Benguigui Citation2010), since its size is so much greater than its neighbours. Nonetheless, both indices support the KMA as being the primate city of Jamaica. Note that the calculations included both figures for the KMA and not Kingston. The KMA comprises the parishes of Kingston and St. Andrew ( and ), which is 100% and 88% urban, respectively. While there has been continuous increase in the population of St. Andrew over the last 50 years, the population of Kingston has been declining. Demographically and commercially and by virtue of its multiple urban nodes (); the KMA contributes more to primacy than DTK and Kingston. As such the KMA needs to be a major consideration in urban redevelopment and development projects.

Figure 7. Distribution of population per urban centre (2011 figures). The shape of the parabola adheres to the Rank Size Rule of urban primacy.

While all redevelopment projects have taken place within the CBD, capital development projects (e.g. sewage works, utility upgrades, new commercial plazas, recreational areas, up-scale residential constructions, educational facilities upgrades and improvements in health care and security facilities) have all occurred north of DTK-CBD. This has contributed to the expansion of the northern nodes (). This expansion phenomenon continues to facilitate dependency and consequently reinforces multiple urban nodes. Urban redevelopment should accept this trend in ‘internal urban restructuring’ and discontinue promoting the CBD approach.

Cost of urban management in the KMA

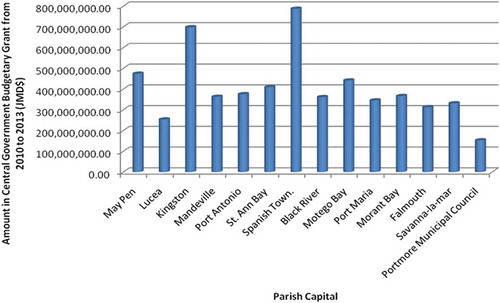

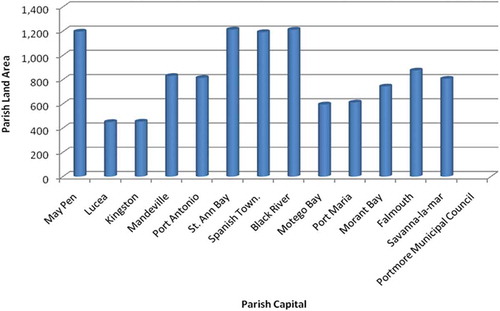

The cost of operating the KMA’s infrastructure and services is mainly borne by the central government. Examination of budgetary allocations to Ministries Departments and Agencies revealed that the costs of operating the KMA’s essential services are a drain on the national budget. KSAC’s financial records revealed that its subvention from the central government is proportionally larger than those to other local authorities (, compare ). Additionally, there are inefficiencies in urban governance within the KMA. Urban management is central to the success of urban redevelopment. The majority of problems plaguing cities results directly from inadequate responsiveness, accountability and management of municipal governance (UN-HABITAT II). This creates gaps between proper infrastructural provision and the effectiveness of urban governance and management.

Figure 9. Distribution of the central government grant to regions 2010 to 2013. Source: Ministry of Finance and Planning.

Figure 10. Regional land area supported by each urban centre. Source: STATIN (Citation2012).

In the area of urban public transportation, the Jamaica Urban Transit Company (JUTC) received subsidies of approximately JM$5.7 billion from 2005 to 2012. This is despite JM$3 billion in financial support and the waiving of $320 million in compulsory taxes. JUTC’s services are only available within the KMA and partly within the KMR. Project financial reports from the UDC, Auditor General (AG) and the Contractor General (CG), disclosures that the major transport centre located in DTK was completed for over JM$400 million, though the initial budget was JM$161 million. Cost overruns were blamed on; design errors, project mismanagement issues and political interference (AG Report, 2009). Since completion in 2008, the facility is still non-functioning, with a cost of JM$2 million (JM$95 K monthly) for electricity. Similar records from the Port Authority of Jamaica reveals that another transport centre in the Half Way Tree node is also plague with financial losses costing central government over JM$100 million to operate annually. For financial year 2011–2012 this facility lost approximately, $2 million monthly (AG Report, 2013). The 2012/13 AG Report reveals similar trends in many other state managed entities within the KMA.

Quoting from the Un-Habitat (Citation2003), Keivani (Citation2010) reiterates that cities contribute up to 55% of GNP in low-income countries, 73% in middle-income countries and 85% in high-income countries (Un-Habitat Citation2003). Figures for Jamaica show similar patterns. According to the Bank of Jamaica (Citation2012), WB (Citation2011), PIOJ and STATIN (Citation2012), the country’s service sectors (located mainly in KMA) accounts for over 64% of GDP as of 2005. This is reverse to what it was two decades ago, when bauxite and aluminium accounted for over 50% (WB Citation2011). Additionally, Keivani (Citation2010) argued that the concentration of people and activities at high densities in cities enables more efficient use of resources than in rural areas. It is on this point that Jamaica and the KMA differs. Political corruption is blamed for high levels of inefficiencies in use of resources within the KMA. Not only have the AG reports over the last 20 years been confirming this trend but international watch dog agencies have also confirmed this. Jamaica has consistently scored lowFootnote4 on the Transparency International corruption index with a 3.3 from 2010 to 2013 or an average of 84 out of 178 countries. High level of informal economic and physical activities (WB Citation2011 and GOJ, 1996 – 50% to 73%) within the KMA is a major contributor to inefficient resource use. The presence of widespread corruption in various arms of government compromises good urban governance.

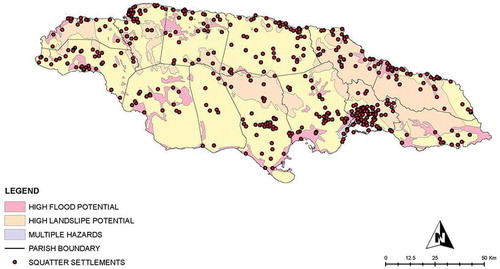

While housing the largest concentration of population (54%) and receiving the largest contribution from the annual budget, the KMA has the potential to contribute to over 80% to GDP (WB Citation2011). However, from 2002 to 2007 this contribution was 56% (PIOJ Citation2012). The KMA also has the largest percentage of squatter settlements in the country (). Studies (Da Costa Citation2003; UTech, 2004; Ministry of Housing Transport and Works Citation2008; STATIN Citation2011; MWLECC Citation2012) have all highlighted that squatting conditions within the KMA and KMR distort the urban property market. Estimates of the KMR’s squatter population (MWLECC Citation2012; USAID 2010; and UTech 2004) vary from 20% to 40% of the population, mainly due to the transient nature of squatters.

Figure 11. National distribution of squatter settlements and their relationship to natural hazard vulnerability.

Additionally, the services operated by the KSAC, central government and quasi-state entities such as water, sewage and electrification face tremendous challenges. The Jamaica Public Service Company, which provides light and power to the country, estimates that approximately US$14million is lost annually to electricity ‘theft’ (JPS 2011). Over 130 urban slum communities, mainly in the KMA, are responsible for this (JPS 2010/11). Similarly, the National Water Commission (NWC Citation2011) reports that water loss; due to illegal connections for financial year 2010–2011 was over US$37 million. The entity operates more than 1000 water-supplies and over 100 sewerage facilities island-wide, mostly are in urban areas. NWC earns for only 30% of its generation and distribution. Both companies are looking to reduce their loss of service due to theft, which is prevalent in the KMA. It is now becoming clear that some of these costs are borne by legitimate paying customers, not necessarily living in the KMA.

The KMR represents the most criminal active area in Jamaica. Of the reported 250 to 300 violent gangs operating nationally over 74% operate within the KMR (JCF Citation2009, Citation2010). Another 7% operate in proximity to the KMR, while 15% operate within the urban areas of the North Coast. The KMR communities provide shelter for over 3000 gang members distributed in over 16 of the 19 police divisions (idem). Over 80% of serious crimes within the KMR and St. James is gang motivated and related. Similarly, gangs are accused of being responsible for as much as 80% of all major crimes in Jamaica (Leslie Citation2010). The national crime rate fell by over 40% in 2009 (JCF Citation2009, Citation2010) after a major security operation, in a political garrison within DTK, lead to the USA extradition of a local gang leader.

One major spin-off from urban crime, which presents challenges to urban management and governance within DTK, is the state’s loss of credibility as a fair reliable provider and protector. Accordingly a parallel informal, philosophical and legal system has evolved. Don-man-ship thrives and proceeds from criminal activities are used to deliver welfare services to communities in the KMA and DTK. DTK and not the KMA has become the haven for government’s support through various forms of redevelopment, reconstruction and revitalisation projects. Krumholz (Citation2009) notes that these programmes, with political motives, mainly benefit private investors and have no real social benefit to the receiving communities and continue to yield no real local economic, social and spatial benefit to the majority of society. Downtown Kingston redevelopment Agencies and Projects

Redevelopment efforts (), since 1907, have been managed by multiple stakeholders, focusing mainly on multiple taxes and investment incentives for commercial, financial and social regentrification. The gap in the table from 1907 to 1960 is credited to urban governance challenges (inter alia) which plagued the city council. The council was dissolved in 1889 and 1891, over financial and responsibilities conflicts, between the Kingston and the St. Andrew Parish Councils. Its reconstitution in 1893 eventually led to the merger of the two councils in 1923.

Table 4. Major urban redevelopment efforts in Downtown Kingston.

The renovation of the Kingston Waterfront from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s was spearheaded through specially created state agencies (e.g. UDC and KRC) and private consultancy (Shankland Cox and Associates and Paul-Cheng Young and Associates). Inner-city slums upgrade was attempted through the Inner-City Renewal Project (ICRP) from the 1980s and 1990s and revisited in 2012/13. The ICRP was to stimulate employment and arrest socio-physical decline. The programme also seeks to empower specific communities by fostering community participation and development (Da Costa Citation2003). Apart from the physical component of rehabilitating and renewing 48 inner-city communities and the market area of DTK, the plan also have a socio-cultural and economic focus. The three phase plan should have been completed in 2005. The ICRP recorded moderate spatial success but fails to deliver socio-economically. The difficulty of agencies to wean the dependency syndrome of inner-city communities is evidence of the lack of plan sustainability. Ironically, many of the inner cities that the plan is supposed to rehabilitate are the results of previous inner-city redevelopment projects (). Osei (Citation2009) has identified a number of factors contributing to dereliction of these housing projects, among them are inability of the residents to afford the maintenance costs, political violence contributing to out-migration and inability of government to continue to subsidise some services. In the Prime Minister’s 2013/14 budget presentation, plans were announced to resuscitate the Inner-city Housing Project once again.

The TIP was implemented in the mid-1990s to attract investment. Other projects were implemented, targeting specific areas including the ongoing port expansion (). Since 2000, there have been a number of piece-meal projects but still no a clear Comprehensive Master Plan for the KMA, KMR or GKMR.

There has been a trend towards broader stakeholder involvement in urban redevelopment by expanding the agencies in column 2 () since the 1980s. Some have had general redevelopment objectives (e.g. KSAC, MOLG and PDC), while others have been project specific (e.g. UDC, SDC, KRC and JSIF) with central government support. Additionally, international agencies such as Cities Alliance, EU, DFID, USAID and UN-HABITAT as well as Non-Government Organisations and private interest groups (e.g. JCC) have all been involved. In many cases, these agencies have been given special legislative powers and granted waivers under the TIP, DKMD, DKRP, KWRC and IKDP (). These have frequently clashed with the operations of traditional agencies (i.e. KSAC, SDC and TPD-NEPA), who have had to deal with the negative side-effects, felt within the KMA and the national economy and urban structure.

The UDC was given legislative powers through the UDC Act of 1968, to bypass the traditional development and planning approval process agencies. Since its inception, the UDC has broadened its operations to include all urban centres nationally. It is also involved in housing provision and tourism development, not necessarily within urban areas. The UDC’s initial development plans for DTK were divided into four phases, namely;

Phase 1: Construction of a multimodal transport centre, redevelopment of the city centre park and revitalisation of the market district;

Phase 2: Establish a space for regular Festival marketplace, construction of a 200-room hotel and conference centre, business centre for Kingston, foreign-affair headquarters and diplomatic district and a new parliament building;

Phase 3: Renewal of the Justice Square and Ward Theatre Square areas making them more pedestrian friendly and along the path of heritage conservation;

Phase 4: Revitalisation of the old railway facilities into an economically viable Railway museum and trade centre.

With the exception for phase 4 all others have been moderately realised. The multimodal transport centre is now underutilised and partially abandoned, as its design and operation were not integrated into the transport pattern of the wider KMA. The construction of the other facilities in phases 2 and 3 has resulted in wastage of potentially valuable commercial space. The hotel has since closed and the conference centre has failed to continuously attract international events. The Ward Theatre is in ruins despite efforts of the UDC and the Ward Theatre Foundation to resuscitate it. At the time of writing, the areas in phase 3 are used for solid waste and sewage and shelter for vagrants. Moreover, the DTK management institutions have done little to dispel the wider perception of DTK as a crime infested area.

The first modern redevelopment plan, VISION 2020, was prepared by Shankland-Cox and Associates (). Discussions with key stakeholders and perusal of MDA documents (obtained under the Access to Information Act, 2004) reveal that the returns expected from the Waterfront Redevelopment Project (KWRP) did not materialise within DTK. The reasons included uncertainties in the national economy during project implementation, influences of urban sprawl, International Monetary Fund structural adjustment and the consequent development of other nodes; the changes in the national tourist industry and finally exclusion of social and economic issues in adjacent inner-city communities. The research has identified that the lacklustre economic performance of the KWRP can be blamed for poor urban governance, which saw reduction of the KSAC to a spectator and other stakeholders (e.g. SDC, NEPA and Civil Society) excluded. The re-establishment of the KRC in the mid-1990s revived the VISION 2020 Plan. Consequently, the KRC evolved into an economic development organisation undertaking many projects and producing ~600,000 sq. ft of commercial space, resulting in a 4.5% and 3.5% employment growth from 1987–1990 and 1990–1994, respectively. For both periods, the growth was higher than that experienced in KMA and Jamaica (Walker et al. Citation1994).

The major goal of urban redevelopment; to foster economic growth, formalise property tenure, halt social decay, dismantle political garrisons and revitalise the city’s cultural and commercial life has not materialised. The moderate successes do not compare to the large scale capital injections. The slow rate of harnessing the energies of contemporary urbanisation dynamics to transform DTK and the KMA into a modern metropolis points to a complex web of forces that must be overcome before the goals of redevelopment are achieved.

Notably, project modifications for addressing contemporary socio-demographic dynamics must include at least five important concerns identified by the extant research ( and ); security in property tenure (26%), physical and economic bias of plans, within a proper philosophical framework, with legislative and institutional backing (26%), broad base participation (24%), capital transfer (13%) and sustainability (11%)

The National Land Policy (1996) and the Land Administration and Management Programme (2003) have both identified property tenure anomalies as major contributing factors to realise the full economic potential for lands. Financial institutions involved in land transactions (Building Societies and Mortgage Banks etc.) have no facility to recognise tenure relationships that do not fall under the law. As such many persons who occupy land and property without formal (legal) proof of ownership or occupation (e.g. leasehold) are not able to enjoy any benefits from these institutions. This land/property ownership and urban development correlation have also been explored by Jenkins (Citation1987), Kombe and Kreibich (Citation2000), Brueckner and Selod (Citation2008) and Walker et al. (Citation1994) in relation to DTK. The business survey and discussions with personnel from the DTK Chamber of Commerce has verified that low rates of property ownership or formal tenure relationships continue to marginalise large segments of the commercial and retail stakeholders from participating in specific redevelopment programmes. Formal tenure is necessary for the membership of the DKMD, where there are more and better benefits (e.g. TIP and special waivers). The alternative is for amendments to existing legislations allowing for the most common form of property tenure to be somehow recognised. The extant paper supports the critical rational approach as the philosophical basis for planning. This involves recognition of the need to mix the formal with the indigenous socio-economic and spatial expressions through institutional and legislative amendment. This recognition will increase social and economic inclusion, and put a major dent in the high level of spatial and economic informality. Works by Al-Sayed et al. (Citation2010) support this approach in an effort to capitalise on the complex socio-spatial dynamics that are inevitable in urban areas. The business survey also revealed that normatively defined tenure relations, will increase the levels of personal investments commercial proprietors are willing to make in the space (physical) to convert it to a place (social). High levels of capital transfer are directly related to high incidences of tenure insecurity. Businesses transfer their earnings to other urban nodes.

Broad based participation is an essential component in the beginning to break the cycle of violence associated with garrison politics, which threatens to further dislocate valuable social and cultural resources. By proportionately involving all stakeholders at relevant stages within the non-linear redevelopment process, there can be a better appreciation for each enclave of stakeholders, and their evolving niche and responsibilities. There is also the added advantage of achieving greater plan success in other areas, such as crime reduction and stemming vandalism of public and private infrastructure. Other spatial projects, undertaken by the government to formalise land and property tenure in squatter communities and on agricultural lands, have yielded such results (UTech 2003; Hall Citation2003; GOJ Citation2009).

Further discussion and critical evaluation

Accepting that the urbanisation pattern of developing countries today is similar to the experience of developed countries from 1875 to 1900s (Preston Citation1979; Brennan & Brockerhoff Citation1998) and that morphologically, most cities in the developed countries were firstly centralised then decentralised (Anas et al.Citation1998), then this is a good starting point on which to assess the relationship between urban redevelopment in DTK and the KMA. Redevelopment promoting the primacy of the DTK-CBD can be equated with centralisation, while multiple urban node and growth in second-tier urban centres can be seen as a movement towards urbanisation by decentralisation. However, given differences in culture and political economy, there is no guarantee that urbanisation, in Jamaica, will unfold in a similar manner to that in developed countries.

From the household survey, 87% of stakeholders and community residents criticised the plans for ignoring community participation and focus, which are important ingredients in sustainable community planning, echoing similar results from Ben-Zadok (Citation2010) and Majee and Hyot (Citation2011). Residents and individuals also expressed concerns of the plan’s failure to; incorporate small businesses (93%) into the economic objectives, and lack of environmental sustainability considerations (78%). These related mainly to property tenure, financial resource transfer and reinvestment.

Most redevelopment projects were conceptualised ignoring the wider implications for the KMA’s development. The projects and efforts to redevelop DTK-CBD are many but not varied enough to represent the multiple complexities of the KMA. They should not have been implemented as permanent solution, but as ‘band aid’ measure pending greater more substantive, integrated and comprehensive solutions. In these scenarios the narrow interest of political, economic and financial stakeholders, received precedence over the interest of local communities, civic groups and the KMA. In the following section a number of key issues relating to a more integrated approach that were examined in the field work are discussed.

Property tenure security

The aim of expanding the commercial sector of DTK through redevelopment depended on the participation of property occupants. The business survey () revealed that 66% are renters, 2% lessee, 17% are owners and 9% have ‘questionable’ property tenure relationship. The low level of owner occupation made it difficult for plan managers to coordinate and make concrete decisions with businesses within the DKMD. Renters and lessees, unlike property owners cannot participate in the range of financial benefits under programmes such as the TIP and façade renewal. In particular, the TIP is a 25% first-year investment tax credit, 10 year exclusion of rental income from taxation and tax-free bond authority. Having formal and legal interest in property is indispensible for participating in this scheme. Similarly, the DKMD is a scheme for property/business owner to make payments into a fund for downtown security enhancement, street clean up and marketing and promotional activities. Studies (Redstone Citation1976; UTech Citation1994; Jacobs Citation2009; Foglesong Citation2009; Krumholz Citation2009) have shown that there is direct positive relation between property tenure and the level of commitment to urban redevelopment projects. Throughout DTK, there are low levels of owner occupier buildings and an 18% absentee ownership of potentially commercially viable premises. Similarly, they have also stressed the importance of broad-based stakeholder consensus and participation as precursors to the success of urban redevelopment. Walker et al. (Citation1994) suggested that there is the potential for an increase in administrative and commercial property rental in DTK if certain conditions are met, chief among them are the reduction in crime and increased infrastructural services to potential clients. Similarly, the area still has a lure for government administrative services for the middle and lower economic class, which constitute the largest portions of the population. The business survey revealed that government administrative, banking and financial services accounts for 8% and 11% of building use, respectively, while religious-spiritual and other uses account for 2% and 5% correspondingly.

Owner-occupier businesses (84%) are located outside of the major redevelopment areas where less redevelopment projects are implemented. This area is occupied by over 60% blacks (Jamaicans of African descendants) and small locally owned businesses, compared to the areas within the CBD, where the business owners are composed of 23% blacks and mostly Asians (Chinese, Indians etc.) and Jamaicans of a closer European ancestry. The issue of ethnicity is yet to be addressed in redevelopment and development of the KMA and DTK.

Physical biased redevelopment

All plans have had strong physical components (33%), comprehensive (33%) and 32% being socio-physical or physical and economic focused (). The main elements of redevelopment has been façade renewal, building renovation and retrofitting, streetscapeing, landscaping, road surface repairs, storm-water drain improvements, garbage receptacles and street signage. No sanitation works have been undertaken, and there is no infrastructural maintenance plan in place. Interview with experts from the UDC and field research revealed that the KWRP has seen over 90% of new building construction in the form of high rise structures since 1965. Apart from the 74% new buildings constructed between the 1920s to the mid-1960s, the other buildings were basically renovated and refurbished after 1907. There are opportunities for heritage building infilling. Similarly, high rates of property abandonment and absenteeism can provide opportunities for infill development.

Community participation

Low levels of public participation correlates with low levels of involvement and ignorance of the plans, by some potentially important stakeholders. Among respondents, 63% felt that the plans cannot be replicated (16% – yes and 21% – no response). This compares to 93% who are disgruntled with the present spatial and socio-economic conditions of DTK, given the high level of financial commitments and fanfare surrounding redevelopment. This level of dissatisfaction exists while 72% are aware of redevelopment efforts (12% not aware and 16% had no response). The potentials for community involvement in the redevelopment plans have been stymied by institutional weaknesses and cumbersome legislations. Experts from the SDC and the KRC, with responsibility for community development within the redevelopment plans, consistently complain of lack of resources and autonomy to develop community projects within the plans. They also criticise the disparity in resources given to community development projects compared to those given to economic and commercial projects.

The mid-1990’s redevelopment efforts realised over 80% of their objectives, particularly at attracting potential investors (Walker et al. Citation1994). This was concomitant with the launch of the Vision 2020 Plan, which initially targeted the revitalisation of the older and more socio-spatially marginalised DTK. However, since then, the support and participation of the business community fell from 87% to 45% (DTK Chamber of Commerce 2001). Many merchants have identified security concerns, low sales and competition from street vendors and other informal commercial activities for their withdrawal from the DKMD projects. Others point to changes in the socio-economic and spatial composition of the local community, low confidence in reinvesting and the competition from other urban nodes. This low level of reinvestment correlates highly with the low levels of involvement in successive plans. Generally, participation in the plans are better realised by being members of the DKMD, requiring formal property ownership. Merchants who are members of the DKMD are 29%, while 64% are non-members. The remaining 7% had undisclosed reasons for non-participation. Small businesses, pedestrians, taxi operators, hand-cart operators, street vendors and inner-city communities were excluded. The perception from plan proponents is that inner-city communities within the vicinity of the DTK-CBD are from the lower socio-economic strata. The only middle to upper class settlement is an apartment block (Ocean Towers) located on the waterfront.

Until recently, local government (KSAC) structures for civil society participation in governance did not exist. In 1999 the Ministry of Local Government launched the multi-stakeholder Parish Development Committees in each Parish. Their primary role is to build consensus and monitor local planning and development efforts, while advising local authorities. Within the KSAC there is no evidence of the PDC’s involvement in redevelopment efforts at any level, especially since the UDC and not the KSAC is the lead agency. Civil society groups continue to demand increased involvement in governance, and in the case of KMA implementing a deliberate process to build a solid foundation for the partnership.

Capital transfer

During the late 20th and so far in the 21st century, high crime rates coupled with high perception of crime and insecurity resulted in capital flight, leaving behind abandoned buildings, unemployment and social dislocation. This phenomenon resulted in general socio-physical deterioration (CFMR Citation2012–2013); squatting and increase in gang activities. The pattern was repeated in sections of the KMR leading to decline in property values and blightedness. Capital flight started on a large scale in 1902, with the construction of a major horse racing facility (race course), which evolved into New Kingston. Some sources (Shankland Cox and Associates Citation1968; and Seymour Citation1983) predicted the potential for capital flight from the TIP, if financial regulations were not implemented. This capital flight took place, as confirmed by Walker et al. (Citation1994), Clarke (Citation2006) and Cummings (Citation2009). The financial investment into the development of the new northern urban nodes () came from the profits of DTK redevelopment, in referring specially to the TIP and monies made from property rental. Therefore the expected windfall effect of the capital reinjection into King Street and other sections of the CBD did not materialise in the rest of DTK and eastern and western urban nodes of the KMA. Residential communities (e.g. Franklyn Town, Norman Gardens, Jones Town and Trench Town – the birthplace of Bob Marley) in these areas quickly became inner-city ghettos and slums.

The rapid rates of financial migration from DTK to other urban nodes as well as the high rental rates in properties compromise and frustrate the efforts of stakeholder’s participation in redevelopment efforts. The business survey and interview with personnel from the DTK Chamber of Commerce revealed that 70% of the original business community, who were present at the commencement of any one redevelopment project, did not participate for the entire project duration. Most of these businesses have now relocated, while still retaining property ownership. Further investigation has traced approximately 50% of these businesses to the northern nodes, accounting for an overall permanency rate of 17%.

Sustainable urban redevelopment

Investment in ‘physical security systems’ can ensure sustainable urban redevelopment. The redevelopment of DTK and KMA was at the expense of ignoring serious principles of carrying capacity of infrastructure and services, ecology, communities and people. Sanitation is a major infrastructural asset of any urban area. Walker et al. (Citation1994) cited serious infrastructural deprivation within DTK as a hindrance to private investment. The lack or inefficient provision of urban amenities such as sanitation, within DTK, was among the most important ones they highlighted. Similarly, Lüthi et al. (Citation2010) argued the importance of urban sanitation as one of the most important service delivery related to, inter alia, sustainable development in South Africa’s townships. They reiterated that ‘the challenges of sanitation service delivery are exacerbated by the fact that many poor urban residents live in the unplanned and underserved informal settlements…’ Sanitation in the KMA and specifically within the DTK is far from functional with 80% DTK’s population living in inner-cities slum conditions. Untreated sewage flowing directly into the harbour and on the streets in poor communities, contributes to the decline in the coastal and marine ecosystem and health and safety.

The sustainable urban redevelopment should accommodate socio-demographic and spatial dynamics, without compromising ecological processes and resources. Citizen’s reaction to redevelopment programmes is an indication of this. More than 73% of households surveyed, reasoned that the plans could not be replicated and have all failed to withstand the tests of time. This view is associated with the concerns of the projects in contributing to increasing overall natural hazards vulnerability, social exclusion and cultural blightedness etc. However, among the experts interviewed, 16% felt that some replication was possible with major modifications (11% had no response). Concerns over ecological sustainability identified include; improper waste management and sanitation, ineffective local governance, low to weak levels of people/community participation, overburdened and decrepit infrastructure and exclusion of social welfare services. Storm water drains are on average over seventy (70) years old. At the time of their construction Kingston had a population of just over 100,000 people and covered a much smaller space.

Conclusion

The research identified some major limitations to redevelopment of DTK; failure to define and ingratiate redevelopment of DTK with development of the wider KMA, lack of philosophical basis for urban redevelopment and the lack of sustainability considerations are all consequences of weak urban governance. Contemporary urbanisation dynamics are not captured, interpreted and substantively integrated in metropolitan management. These are all made worse by partisan politics in all facets of urban management.

The spatial morphogenesis of the KMA is showing signs of multiple urban nodes, moving away from a CBD, despite all efforts to maintain this tradition. This urban market determined morphogenesis is a direct consequence of a mixture of development control over the years plus exclusive land use management, not necessarily lead by the formal urban management institutions (KSAC, NEPA and UDC etc.), but my private developers operating outside of the formal system out of bureaucratic frustration. Urban redevelopment under the ambits of Metropolitan Urban Management (MUM) is a more feasible approach, where each node will be appreciated for its resource endowment and competitive advantage. Moreover it will allow for the capture of the myriad of informal developments activities, bringing them under the umbrella of the formal system.

MUM will give greater returns on investment dollars by integrating DTK into the urbanisation dynamics of the KMA, reducing its drag on the KMA and on the national economy. MUM will enhance and promote social inclusion and justice, by systematically removing spatial and socio-economic prejudices attached to DTK. There exists no policy or strategy to retrofit urban nodes outside of the KMA or second tier cities with the requisite physical, administrative, legislative and institutional resources to attract investments. Despite a defunct CBD the KMA with its multiple-nodes has proven to be much more sustainable and resilient. These nodes have naturally morphed to provide urban services contributing to the primacy of the KMA. The legitimisation of these services simultaneously enhances DTK’s competitiveness.

The government TIP should be sector tailored and extended to the KMA. This, sector-focus TIP backed by legislative and institutional support should serve a philosophical and technical basis for urban redevelopment. By virtue of its multiple commercial mixtures DTK has the potential to positively contribute to the symbiotic interrelationship that exists among the KMA’s multiple urban nodes. TIP supporting commercial and other investments in other nodes and second tier cities is the natural course of planning action, given their already natural effect of spurring growth.

There is need for a National Urban Redevelopment Policy and National Urban Policy encapsulating urban reconstruction, modernisation, renewal and revitalisation. Similarly, urban modernisation philosophies must embrace respect of the ecological sensitivities of urban areas. Thus in redefining the scope of urban redevelopment, the incorporation of sustainability principles should be the desired end of reconstruction, modernisation, renewal and revitalisation.

Principles of new urbanism fostering pedestrianisation, community based resource management and citizens participation have tremendous potential for application within the KMA. Accordingly, the role of Community Based Organisations as they impact on the manner and-or potential to make everyday socio-economic and political decisions must be revised. The task is to rethink the structure and function of the KMA and its supporting institutions, making them responsive to demands imposed by contemporary and emerging urbanisation dynamics. More efforts must be made for development of the infrastructure and facilities of the KMA and allow those to fuel investments and reinvestment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

earl bailey

earl bailey undertook PhD research in Urban Planning and Land Resources Management in the School of Resources at the China University of Geosciences, Wuhan. His dissertation focused on urban spatial development planning for Jamaica. He earned a BSc degree in Urban Planning and a postgraduate diploma in Education from the University of Technology, Jamaica (UTech) and an MSc degree in Natural Resources Management and Urban Planning from the University of the West Indies (Mona). He is a past president of the Jamaica Institute of Planners and a practicing planner in Jamaica and the Caribbean. He has been a lecturer in the Urban and Regional Planning Department of the Faculty of the Built Environment of the UTech for over 20 years.

Misilu Mia Nsokimieno Eric

Misilu Mia Nsokimieno Eric comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). He attended the school of building and public works, Kinshasa, where he received his BA in Urban Planning. His senior essay topic was “The rehabilitation of public spaces: the case of railroad property”. In 2010, he received his master’s degree in Cartography and Geography Information Systems at the China University of Geosciences, Wuhan. He is currently doing his doctorate in Environmental Planning and Management in China University of Geosciences, Wuhan. His research so far includes intellectual insight on sustainable urbanisation’s challenge in DRC, investigation into informal settlement dynamics in DRC and urban policy.

Notes

1. USD$1 = JM$115 as of February, 2015

2. Forming the Kingston Metropolitan Area (KMA)

3. Part II, Section 8 and First Schedule (Sections 3, 7 (1)

4. The CPI measures it corruption score from one to 10, with 10 being perceived to be least corrupt and one as most corrupt. In 10 years, Jamaica has never scored higher than 4.0 on TI’s CPI.

References

- Al-Sayed K, Turner A, Hanna S. 2010. Modelling the spatial morphogenesis in cities: the dynamics of spatial change in Manhattan. London (UK): University College London.

- Anas A, Arnott R, Small KA. 1998. Urban spatial structure. J Econ Lit. 36:1426–1464.

- Bank of Jamaica. 2012. Monetary policy and foreign exchange rate developments – 1984 to present [Internet]. [cited 2015 May 11]. Available from: http://www.boj.org.jm/uploads/pdf/interest_rates.pdf

- Ben-Zadok E. 2010. Process tools for sustainable community planning: an evaluation of Florida demonstration project communities. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 1:64–88.

- Brennan EM. 1999. Population, urbanization, environment, and security: a summary of the issues. Environmental change and security. Project report, Issue 5. Washington (DC): Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Scholars (Comparative Urban Studies Occasional Papers Series, 22).

- Brockerhoff M, Brennan E. 1998. The poverty of cities in developing regions. Popul Dev Rev. 24:75–114.

- Brueckner JK, Selod H. 2008. A theory of urban squatting and land-tenure formalization in developing countries. Irvine: Department of Economics, University of California; Paris: Paris School of Economics (INRA), CREST and CEPR.

- Clarke CG. 2006. Kingston, Jamaica: urban development and social change, 1962–2002. 3rd ed. Kingston: Ian Randle.

- Cohen B. 2006. Urbanization in developing countries: current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability. Technol Soc. 28:63–80.

- Commonwealth Finance Ministers Report (CFMR). 2012–2013. The renaissance of downtown Kingston. Economic rebirth of a city and Downtown Kingston: the cultural renaissance begins. Henley Media Group Ltd in Association with the Commonwealth Secretariat. London: Trans-World House.

- Cummings V. 2009. The problem of squatting in Jamaica, Jamaica Daily Gleaner Online, May 24.

- Da Costa J, 2003, Jamaica: land policy, administration and management: a case study, Paper presented at Workshop of Land in the Caribbean: Issues of Policy, Administration and Management in the English Speaking Caribbean, 19–21 March, 2003 in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. Edited by Dr. Allan Williams.

- Davis M. 2004. Planet of slums: urban involution and the informal proletariat. London: Verso.

- De La Roca J, Hernandez M, Robles M, Torero M, Webber M. 2006. The informal sector in Jamaica [ Economic and Sector Study Series, RE3-06-010]. Kingston: Inter-American Development Bank.

- Foglesong RE. 2009. Planning the capitalist city. In: Campbell S, Fainstein S, editors. Readings in planning theory. 2nd ed. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing.

- Fry GW. 1983. Bangkok: the political economy of hyper-urbanized Primate City. Hong Kong J Public Administration. 5:1983.

- Gabaix X. 1999. Zipf’s law for cities: an explanation. President and fellows of Harvard College and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Q J Econ. 114:739–742.

- Galiani S, Kim S. 2008. The Law of the Primate City in the Americas. Washington University in St. Louis Conference Proceedings

- Gilbert A. 1996. land, housing and infrastructure in Latin America’s major cities. In: Gilbert A, editor. The mega cities in Latin America. Tokyo: UN University Press.

- Government of Jamaica (GOJ), Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) Department of Local Government. 2009. Final report of the national advisory council on local government reform. Kingston: Government Printing Office.

- Hall DH. 2003. Restructuring urban squatter settlements in Jamaica: a case study of selected communities - Barrett Hall (St. James) and Riverton Meadows (St. Andrew) - unpublished research.

- Hardoy J, Mitlin D, Satterthwaite D. 2001. Environmental problems in an urbanizing world: finding solutions for cities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. London: Earthscan.

- Harman C. 2008. A people’s history of the world – from stone age to the new millennium. London (UK): Bookmarks Publications Ltd, 1999, 2002. Verso 2008.

- [ILO] International Labour Organisation. 2002. Decent work and the informal economy. International Labour conference Report VI 90th session 2002. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Jacobs J. 2009. The death and life of great American cities. In: Campbell S, Fainstein S, editors. Readings in planning theory. 2nd ed. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2003.

- [JCF] Jamaica Constabulary Force. 2009. Gang threat assessment survey. Statistical Department. Kingston: JCF.

- [JCF] Jamaica Constabulary Force. 2010, Jamaica Constabulary Force Crime Review 2007. Kingston: Jamaica Constabulary Statistical Department.

- Jenkins DP. 1987. Peri-urban land tenure: problems and prospects. Dev South Afr. 4:582–586.

- Jenkins P, Smith H, Wang PY. 2007. Planning and housing in the rapidly urbanising world. In: Gallent N, Tewdwr-Jones M, editors. Housing, planning and design series. London (UK): The Bartlett School of Planning, University College London.

- Keivani R. 2010. A review of the main challenges to urban sustainability. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 1:5–16.

- Kombe W, Kreibich V. 2000. Reconciling informal and formal land management:. Habitat Int. 24:231–240.

- Krumholz N. 2009. Readings in planning theory. In: Campbell S, Fainstein S, editors. Equitable approaches to local economic development. 2nd ed. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2003.

- Leslie G. 2010. Confronting the Don: the political economy of gang violence in Jamaica. Geneva: Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

- Lüthi C, McConville J, Kvarnström E. 2010. Community-based approaches for addressing the urban sanitation challenges. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 1:49–63.

- Majee W, Hoyt A. 2011. Cooperatives and community development: a perspective on the use of cooperatives in development. J Community Pract. 19:48–61.

- Ministry of Housing Transport and Works. 2008. Annual report 2007 to 2008. Kingston: Government of Jamaica Ministry.

- [MWLECC] Ministry of Water, Land Environment and Climate Change. 2012. Annual Report: partnership for sustainable development 2001/12. Kingston: Government of Jamaica.

- Njoh A. 1999. Urban planning, housing and spatial structures in Sub-Saharan Africa: nature, impact and development implications of exogenous forces. SOAS Studies in Development Geography. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

- [NWC] National Water Commission. 2011. Annual report. Kingston: Copyright National Water Commission.

- Osei P. 2009. Managing urban regeneration in Jamaica: the cluster implementation approach and outcomes. Local Government Studies. 35:315–334.

- [PIOJ] Planning Institute of Jamaica. 1991. Jamaica survey of living conditions 1991. Kingston: PIOJ Jamaica.

- [PIOJ] Planning Institute of Jamaica. 2012. Jamaica survey of living conditions 2012. Kingston: PIOJ Jamaica.

- Portnov BA, Benguigui L. 2010. Does Zipf’s law hold for primate cities? some evidence from a discriminant analysis of world countries. 50th Anniversary European Congress of the Regional Science Association International “Sustainable Regional Growth and Development in the Creative Knowledge Economy” 19–23 August 2010 - Jonkoping, Sweden

- Preston SH. 1979. Urban growth in developing countries: a demographic reappraisal. Popul Dev Rev. 10:127–133. used in Brockerhoff, M., & Brennan, E.M., (1998).

- Rashid W, Khairkar VP. 2012. Declining city-core of an Indian primate city: a case study of Srinagar city. Int J Environ Sci. 2:2012.

- Redstone LG. 1976. The new downtowns: rebuilding business districts. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill; p. c1976.

- Seymour M. 1983. Cast study: Kingston Restoration Company. Regaining the balance downtown through public private partnership for renewal, economic growth, social and cultural re-engineering in Jamaica’s Capital City.

- Shankland Cox and Associates. 1968. Vision 2020. London: Shankland Cox and Associates.

- Sherlock P, Bennett H. 1998. The story of the Jamaican people. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers.

- STATIN. 2011. Population and housing survey of Jamaica 2011. Kingston: STATIN.

- STATIN. 2012. Population and Housing Census 2011 Jamaica. General report Volume I. Kingston: STATIN.

- Tortello R. 2006. Pieces of the past: a stroll down Jamaica’s memory lane. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers.

- Un-Habitat. 2003. The challenge of the slums: global report on Human Settlements 2003/United Nations Human Settlements Programme. London: Earthscan Publications.

- [USAID] United States Aid for International Development. 2010. Jamaica country profile: property rights and resources governance. Kingston: USAID.

- [UTech] University of Technology. 1994. Inner-city redevelopment: the case of Jones Town in Kingston Jamaica.

- Walker JC, Boxall P, Stoppi M, Cheng-Young P and Associates. 1994. Financial feasibility analysis Downtown Kingston waterfront development.

- Wedderburn C, Chaing EP, Rhodd R. 2012. The informal economy in Jamaica: is it feasible to tax this sector?. J Int Business Cult Stud. 6.

- [WB] World Bank. 2011. Jamaica Country economic memorandum: unlocking growth. Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit, Caribbean Countries Management Unit, Latin America and the Caribbean Region. Report No. 60374-JM