Abstract

In Egypt, between 1982 and 2004, agricultural land was being lost at an estimated annual, daily and hourly rate of 54,545, 149.4 and 6.22 feddan, respectively. In early 2006, the General Organization for Physical Planning introduced a programme, based upon a participatory approach, for setting up General Strategic Urban Plans (GSUP) for 231 Egyptian cities; as an attempt to prevent further urban sprawl on agricultural land. Detailed Plans for Urban Expansion Areas (DPUEA) as a main outcome of the GSUP of the city of Kotor is examined. This article examines two aspects; first it looks at the process, and the various challenges, of carrying out the DPUEA as the main outcome of the GSUP. Second, it investigates the process of collective planning; by which the stakeholders’ participation played a major role to facilitate/improve the outcome from a guided land development plan. Accordingly, this article sheds light on the assumption that abolishing obstacles of the DPUEA process, with ‘technical enablement’ at the local level, combined with a collective planning process would facilitate land delivery system for the urban poor and eradicate further urban sprawl on agricultural land. It concludes that a collective planning process with ‘technical enablement’ would facilitate land delivery system for the urban poor in a sustainable manner. Furthermore, the government should play the role of an agent for urban sustainability in order to magnify the political goal of saving and rescuing agricultural land and to encourage a guided sustainable urban development in the back desert in Egypt.

1. Introduction

Informal rapid urbanisation, a lack of an overall urban planning framework, and increasing housing demand for the urban poor were among the causes that led to the appearance of urban informality on agricultural land. Upon which such informality expanded throughout Egyptian cities without any regard to zoning and construction regulations. Between 1982 and 2004, an estimated 1.2 million feddan (one feddan is equivalent to 0.42 of a hectare) of agricultural land has been decimated through urban informality, which has come to account for 35–40% of the total housing production (General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP) Citation2006). Agricultural land is being lost at an estimated annual, daily and hourly rate of 54,545, 149.4 and 6.22 feddan, respectively. In the year 2014, the value of informal housing was worth around US$360.0 billion (De Soto Citation2014). As of 2007, there were an estimated 8.5 million informal housing units with at least 21.2 million Egyptians living in urban areas. Of the estimated 8.5 million informal housing units 4.7 million of them are on agricultural land; within or outside municipal boundaries. Of the estimated units, 0.6 million are located on government-owned desert land within municipal boundaries and 3.2 million units are outside administrative village boundaries (Egypt Human Development Report Citation2010). During the inter-census period (1996–2006), the annual urban housing production reached 263,838 units. Of these, 55.6% are formal and 45.4% are informal (CAPMAS, Citation2006). In Cairo, 81% of informal units sit on privately owned agricultural land, with 10% on government-owned desert land and the remainder on state-owned agricultural land (Cities Alliance Citation2008; UN-HABITAT Citation2012).

The GSUP for 231 cities, 4632 villages and 27,000 hamlets indicate expansion on adjacent agricultural area. Accordingly, it is expected that by the year 2027, Egypt will formally lose around 113,300 (Soliman Citation2010), 207,860 (Toth Citation2009) and 13,500 feddan of agricultural areas surrounding Egyptian cities, villages and hamlets, respectively. This expansion adds up to a total loss of agricultural land of 334,660 or 23,904 feddan per year. Despite the fact that the political context in Egypt has radically changed after the January 2011 and June 2013 revolts, nothing has been done on the ground. Three years after the two revolts of January 2011 and June 2013, Egypt has lost around 150,000 feddan of agricultural land to housing informality.

In 2014, the total population of Egypt approached the figure of 83 million, the largest population in North Africa (CAPMAS Citation2012; UN-HABITAT Citation2012); this figure does not take into account the further 8 million Egyptians living abroad. About half of the urban population is concentrated in two major urban centres: Cairo and Alexandria. The remaining populations are scattered in 229 small and intermediate urban cities along the Nile river valley and Delta. The total population of Egypt will reach around 151 million by 2050 (CAPMAS Citation2012), of which 62.4% will be urbanised (UN-HABITAT Citation2008). With this rapid growth of population, it is expected that agricultural land conversion to housing informality will perpetuate (Soliman Citation2012) unless an appropriate policy is formulated.

This article examines two aspects; first it looks at the process of, and the various challenges of, carrying out Detailed Plans for Urban Expansion Areas (DPUEA) as a main outcome of the GSUP. Second, it investigates the process of collective planning by which the stakeholders’ participation played a major role to facilitate/improve the outcome from a guided land development plan.

Accordingly, this article sheds light on the assumption that abolishing obstacles to the DPUEA process, with ‘technical enablement’ at the local level, combined with a collective planning process, would accelerate the implementation process on the ground for preparing concrete Action Plans (i.e. land allocation, land readjustment, etc.) (Soliman Citation2015), as well as facilitating the land delivery system for the urban poor in a sustainable way to eradicate further urban sprawl on agricultural land. It concludes that the collective planning process with ‘technical enablement’ would facilitate land delivery system for the urban poor in a sustainable manner, and that the government should play the role of an agent for urban sustainability in order to magnify the political goal of saving and rescuing agricultural land and to encourage a guided sustainable urban development in the back desert in Egypt.

The articles utilises the above two arguments through two sources; first, the examination of reports of the GSUP of selected Egyptian cities, and the DPUEA of Kotor city and second, the examination of derived information based on Kotor city as a case study, in which the author was involved in the preparation of the GSUP and the DPUEA (GOPP Citation2006). The study goes beyond the quantitative statistical results and intends to understand the behavioural conditions through the stakeholders’ perspective. Therefore, the exploration and understanding of complex issues are highlighted. By including both quantitative and qualitative data, the case study helps explain both the process and outcome of a phenomenon through participant observation, and analysis of the cases under investigation (Tellis Citation1997).

The rest of this article is organised as follows: Section 2 presents literature review and Section 3 briefly examines the process of GSUP and the research setting. The process of the DPUEA is explored in Section 4, while the collective process is formulated in Section 5. The concluding section summarises the main issues and provides directions for a future policy as a way for tackling the implementation process of the DPUEA.

2. Social networks and the collective process

Community’s participation in the housing process was explored in several classical books by John Turner (Turner & Fichter Citation1972; Turner Citation1976), Hasan Fathy (Citation1972) and Pierre Bourdieu’s (Citation1977), all of which elaborated more on organisational studies. The principle of participation can mean any process by which the users of an environment participate together to shape it (Alexander et al., Citation1975). Turner (Citation1976) identified the role of social networks in sustaining the production of informal housing in the form of three laws of freedom to build. Those laws are, first, when dwellers control the major decisions and are free to make their own contribution to their own environment; both the process and the environment produced stimulate individual and social well-being. Second, the important thing about housing is not what it is, but what it does in people’s lives. The third law is that any deficiencies and imperfections in your housing are infinity more tolerated if they are your responsibility than somebody else’s. Arif Hasan (Citation2001) argued that the capacity and capability of government institutions can never be successfully built without pressure from organised and knowledgeable groups at the grassroots. Social networks, through which stakeholders access the necessary resources or ingredients to acquire housing, result in housing networks. Understanding how social networksFootnote1 contribute to the economic and social fabric of life in developing countries is important (Woolcock & Narayan Citation2000; Collier Citation2002), and social cohesion is critical for societies to prosper economically and for development to be sustainable (Adler & Kwon Citation2002). The interdependent nature of actors (where actors are the individuals within a network) are a key distinguishing characteristic of a social network, and their structures and connectivity and the distribution of power are key components of marketing systems (Layton Citation2009; Jackson Citation2010). Fawaz (Citation2008) stated that without systematically resorting to the terminology of social networks, the abundant literature that documented the formation of informal settlements during the 1970s and 1980s challenged their condemnation as ‘spontaneous’ by revealing that these neighbourhoods were organised and managed through thick webs of social relations (Collier Citation1976; Perlman Citation1976; Ward Citation1982; De Soto Citation1989).

On the other hand, social networking depends on symbolic capital, which in turn depends on publicity and appreciation; it has to do with prestige, reputation, honour, etc. It is economic, cultural or social capital in its socially recognised and legitimized form. There are symbolic as well as material dimensions of all three types of capital. Symbolic capital is a ‘capital of honour and prestige’ (Bourdieu Citation1977). Therefore, social networks within informal areas are playing a crucial role in; first, creating organisations of their own so they can negotiate with government, traders and NGOs; second, directing assistance through community-driven programmes so that they can shape their own destinies; and finally, they sustain their own command on local funds, so that they can eradicate corruption (Narayan et al. Citation2000). Hamdi (Citation2004) argued that the guru of urban participatory development is looking for ways of connecting people, organisations and events, to seeing strategic opportunity. It means thinking and acting practically (locally, nationally and globally); and thinking and acting strategically (locally, nationally and globally). It is not doing either/or but doing both, and doing it reflectively, collectively and progressively. A special issue of Habitat International (Citation2010, 34:3) presented that the poor relied mainly on their own efforts and their social networks (Tunas & Peresthu Citation2010). Thus social networks played a major role in negotiating better deals with landowners for the lease or purchase of land (Yap & De Wandeler Citation2010). The poor also relied on housing microfinance, community-based finance savings (Landman & Napier Citation2010), loan groups and consumer credit for building materials (Ferguson & Smets Citation2010).

As Engels (Citation1970) puts it, ‘The “working people” remain the collective owners of the houses, factories and instruments of labour, and will hardly permit their use by individuals or associations without compensation for the cost.’ However, the individuals are often viewed as negative modification resulting in increased fear and isolation, while the association is a collective response in which individuals act jointly to undertake activities that they could not accomplish on their own (Barker & Linden Citation1985). The stakeholders as members of a ‘community’ can be part of productive, non-capitalist social processes, which lays the basis for a collective consciousness and a cooperative ethic (Barton Citation1977). The collective planning and administration of social production requires that not only the means of production but also the distribution of the total product be subject to explicit social control. Thus, social control in the physical environment is dominating the right of ways, pattern and everyday urban life. The collective planning or process would require trust, transparency, accountability and responsibility among all the stakeholders for certain activities to be achieved.

However, the provision of property rights to residents of low-income settlements became a central theme for social networks, as it is the best strategy to transform their corporation into a complete housing system. This paradigm has become so significant within multilateral agencies that housing and land issues are mentioned in the Millennium Development Goals as one part of Goal 7. Perhaps the most positive aspect of the changes in the World Bank policy (Buckley & Kalarickal Citation2006) since the mid-1990s is that the Bank has learned much about the composition of a more appropriate policy environment. The environment entails a strong reliance on an active role of the private sector, recognition of the high speed at which market-based housing finance flows, treating land as an important input into the provision of housing services, accounts for a large fraction of total economic development and emphasises the importance of collective action. This paradigm has become so significant within multilateral agencies that not only securing of land has become the single indicator, but also market mechanisms that facilitate land delivery systems have become a crucial factor.

In the field of shaping the environment, Soliman (Citation1985) found that informal settlements operate at least partly outside the official system through three aspects of social networks in squatters’ settlements in Egypt. First, the presence of a hierarchy of use, meeting spaces and physical layout are significantly related to social, economic and climatic considerations. Second, the pattern and the space form were created by the residents themselves without government or professional intervention. The settlers were their own architects and they formed their settlement according to their needs and requirements. The residents constituted self-reliant communities, where people decide together how to shape their common destinies. All decisions about what to build and how to build it were in the hands of the users (Alexander et al. Citation1975), which represents the principle of the social networks. Third, the hierarchy of circulation systems within informal housing areas reflected the citizens’ cultural and traditional ties. The result was a traditional rural pattern, similar to the citizens’ area of origin, with a variation of spatial proportion relating to street widths, building facades and a hierarchy of space with limited access. On the other hand, the government thinks the above system operates in a certain way but in practice it operates according to its own social networks and the government’s system fails to engage and therefore fails to work.

In the field of delivering goods, it is necessary to distinguish between the responsibility for ‘provision’, which might be the government’s concern, and ‘production’ which might be done through the social networks. Informal land market has provided housing plots at reasonable prices for the majority of population and accelerated land delivery processes for the urban poor. Whereas official programmes of land delivery system have been consistently ineffective because of their financial incoherence, and laissez-faire policies have led to the near-complete breakdown of the formal land delivery system, manifested in the rapid growth not only illegal settlements, but also the establishment of informal land markets within most of large cities.

Scholars (Dasgupta & Beard Citation2007) and practitioners analysing community-level collective action have become increasingly interested in how relationships based on trust, reciprocal exchange and social networks, i.e. social capital, affect outcomes. The idea that development plans as such could be directly ‘implemented’ reflects a very traditional conception of a plan as a spatial blueprint, which would steadily be translated into built form on the ground (Healey Citation2003). The underlying idea is to create an applicable sustainable environment at the right time and in the right place in which all the stakeholders in housing process, through a collective process, are actively cooperating to manage the process positively for their own benefits without harming others. The relationships among the three independent systems, state, market and social network, are correlated. The latter reflects strong social ties, which would formulate local finance customary, as well as working on creating, directing and sustaining cultural identity.

3. Official planning process: does it prevent or accelerate informality?

Recognising that many cities in Egypt lack a vision for urban development and possess limited capacities for good urban management, in early 2006 the GOPPFootnote2 introduced an official planning process through setting up a General Strategic Urban Plan (GSUP) for Egyptian Cities. GSUP is an attempt to involve the various stakeholdersFootnote3 in drawing up new boundaries for those cities to meet the future requirements of its citizens the next two decades, and to prevent further urban sprawl on agricultural land. The following is a brief examination of the GSUP and a background on the research setting.

3.1. General Strategic Urban Plan (GSUP)

The GSUP objective was to create a future vision of the integrated development of a city that utilises available assets and resources, especially in facilitating land delivery systems to accommodate the growing population and to fulfil different amenities for the city until the target year.

The GSUP adopted a decentralised and integrated approach to address four main substantive areas: shelter, social services (SS), basic urban services (BUS) and local economic development (LED); environment, governance and vulnerability are additional cross-cutting areas that continued to inform the process. Through a participatory process, local stakeholders participated in preparing the GSUP with priority actions to improve housing conditions, urban services and local economy. The GSUP provided a roadmap for developing the city for the next two decades. In addition, the project delivered land and urban information systems (in GIS format), and training on land regularisation to enhance urban management. The project also supported urban observatories to contribute to the effective management of urban policy. According to the Planning and Building Law No. 119 of 2008 (PBL119), the GSUP in itself does not initiate new developments, unless the DPUEA is prepared and implemented on the ground. In the case of having a final approval of the GSUP then it is possible to carry out the DPUEA.

As illustrated in , the methodology of the GSUP was divided into three phases: milestone one covers field survey and data collection and analysis; milestone two covers a city consultancy, and a preparation of a future plan for a city; and milestone three covers the approval and final submission of the GSUP. During these phases, subsequent workshops were held with the stakeholders to hear their responses to the questionnaires and to review the outcomes of data through analysis. The timing for implementation and plans to finance investment projects were settled. Investment plan was reached to the needed social amenities (school, health centres, public space, etc.), economic activities (commercial areas, small scale industrial activities, etc.) and basic infrastructure (local road network, sanitary services, drinking water, etc.). As a result, funds and the required land for such amenities were secured so as to facilitate economic and social development in the current process. As will be illustrated later, several complicated and long procedures occurred during all the three phases of the plan. Also, during preparation of the DPUEA, it passed through long and complicated procedures and might take more than one year to be finalised. illustrates the progress of the GSUP for six cities, four cities in Lower Egypt and two cities in Upper Egypt. Out of the six cities, only one city is in progress of DPUEA, and another city is under study, while the other four cities are not eligible for DPUEA yet. It appears that the GSUP might take between 2 and 7 years to be finalised due to many reasons that will be discussed latter.

Table 1. Progress of the GSUP for six cities.

According to the PBL119, decree no. 14, the General Departments for Planning and Urban Development (GDPUD) in the governorates have to prepare the DPUEA for cities and villages, based on the GSUP for the city or the village. The GDPUD has the right to pledge the preparation of the DPUEA to the experts, consultants, authorities, engineering offices and specialised consultancy registered with the GOPP and according to the rules and procedures prescribed by the regulations for the PBL119.

3.2. Research settings

This research covers the city of Kotor, as a small city, located in the middle of the Delta region. Kotor is located to north of Tanta City (the capital of El Gharbeyhia Governorate), at a distance of 20 km. The GSUP of Kotor city, within a scope of Terms of Reference (TOR), was accomplished as a cooperation programme between the GOPP and UN-HABITAT. The city was chosen because it illustrated the history of agricultural land conversion to housing informality, the processes of landownership transaction and the relationship between urban growth and land reform laws. It also possessed desirable characteristics for the urban poor such as legality of tenure, access to job opportunities and access to cheap transport. It reflects the process of a proper development that would alleviate further loss of agricultural land into urban informality. The GSUP for Kotor city started in early 2009, and it was approved according to Ministerial Decree No. 306 of the year 2011, published in the Official Gazette issue No. 216 dated 20/09/2011.

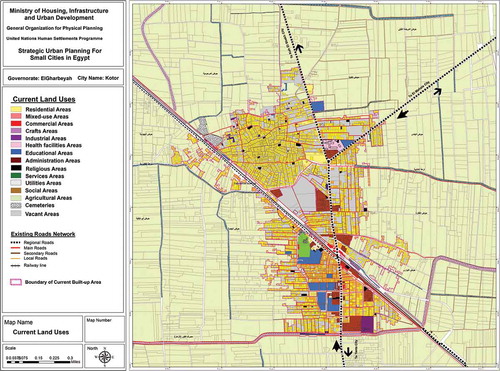

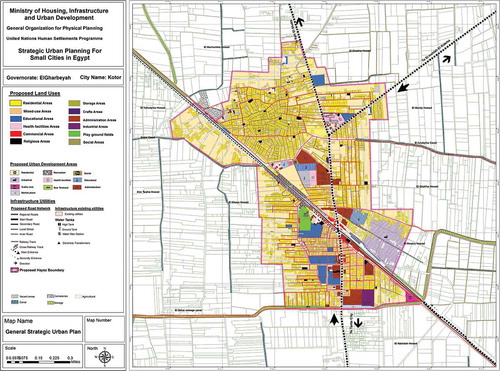

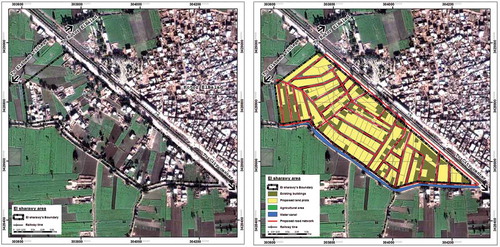

Kotor city has expanded informally in all directions on adjacent agricultural land with no limitation for urban growth, and far exceeded the official city cordon (Hayez) of 2000 (see , and ). All informal residential buildings that have been built outside the city cordon (Hayez) safely enjoy their security of tenure (in the form of de jure recognition), and therefore they are not exposed to the risk of eviction. Within the scope of the GSUP, a new Hayez with an area of 460.79 feddan has been drawn up, adding 129.32 feddan to Kotor’s current built-up area of 331.47 feddan. As illustrated in , this addition of land will meet the future requirements for housing and other social amenities until the target year.

Table 2. The development of Kotor city between 1946 and 2010.

As illustrated in and , there are three challenges facing the approval of the GSUP and the DPUEA for Kotor city and other cities in Egypt: spatial, institutional and legalisation challenges. Spatial challenges are summarised as follows: first, lack of cadastral maps of the status quo of urban expansion areas. Second, the current status of the new added urban expansion areas is completely different from what the scheme has been adopted for in the GSUP. Third, fragmentation of agricultural property, thus creating many obstacles to tracing land transaction. Fourth, the difficulty in determining the real landowners and various official documentation of land tenure. Fifth, mismatch between the property lines, the current territory boundary and registered/or unregistered land documentation. Finally, the spreading of urban sprawl areas on the proposed scheme of the GSUP.

Table 3. Generalised time frame for the GSUP and the DPUEA.

Table 4. Summary of the main challenges facing the approval of the GSUP and the DPUEA.

Institutional challenges are summarised as follows: first, with each phase of the GSUP processes, a revision and evaluation must be fulfilled. This includes complicated procedures that take a long time to be officially approved. All of the evaluation processes in the GOPP offices are being reviewed entirely on the desktop without questioning what is going on the ground. Second, during the final stage of the GSUP, the Hayez committee had to approve the new added area to the city. Several meetings were held between the Hayez committee and members of the GOPP to agree on the proposed city boundary and its limitation. These meetings might take up to one year to reach a conclusion for the proposed Hayez. Third, the Operations Department in the Ministry of Defence (ODMD) reviewed – for final security approval – Kotor city’s GSUP and approved it under no. 1440 of 13 May 2010, but this was conditional on certain heights for the buildings in each sector in the city. The ODMD is asked for a cadastral map of the city as well as the proposed Hayez of the city. The ODMD reviews the surrounding area in light of military camps, and many meetings with members of the GOPP have to be carried out to discuss the actual outline of the proposed city boundary. A team of the ODMD has to pay several visits to the city and its surrounding area to mark any Military bases. Nearly two years have passed since the application of the plan was handed to ODMD until gaining the final approval to implement the GSUP for Kotor city. Some other cities are still waiting for the approval of the ODMD for more than three years. In the case of having official final approval of the GSUP by the responsible Ministry, then it is possible to carry out the DPUEA. Also, the preparation of the DPUEA is passed through long and complicated procedures that might take more than one year to be finalised.

Legalisation challenges are summarised as follows: first, the responsible consultant has to obtain the consent of the local People’s Council of the City on the project after initial approval by the Regional Office of the GOPP. Second, inability of the Planning and Urban Development departments in the governorates to proceed with the final accreditation procedures in accordance with the legislation and rules applicable only after the approval of the Regional Office of the GOPP in these procedures. Third, according to the PBL 119, there are multiple administrative authorities that are reviewing the final outline of the project. Fourth, there are conflicting decisions issued by the Ministry of Housing, for determining the re-planning, unplanned and informal areas, and lack of clear interpretation of the PBL 119 for the definition of slums and how to deal with. Fifth, inability to make decisions on water and sewage irrigation canals that could be inside/or perimeter-scale of the DPUEA. It is worth mentioning that raising a controversy about the legality of reusing or including water and sewage irrigation canals within the project always occurred, even after the ministerial approval of the overall strategic plan of the city. Finally, inability in the decision-making in the adoption of detailed plans measures.

4. The planning process of the DPUEA

At the beginning of 2012, the DPUEA was launched. The DPUEA planning sequence in Kotor city was divided into three phases. A meeting with the City Leader was conducted to present the methods to have the political approval, followed by the field surveys and interviews at the site, through examinations for availability of maps and spatial survey for land uses, basic surveys including existing utilities and collecting indicators to determine the current situation. Interviewing the stakeholders and several individual meetings coincided with the field survey. These processes analysed the existing situation, consulted the stakeholders through workshops and meetings to clarify the potentialities, constraints and drew a clear picture about the current status of the DPUEA.

4.1. Main principles

In order to carry out the DPUEA, several principles were introduced by the consultant to implement the DPUEA and to promote the collective process in Kotor city. First, looking at the norms that determined the source of the legalisation and formalisation procedures of the DPUEA was a prime concern. It was necessary to observe and get involved in how the process of land acquisition, between land occupants (contracting parties, landowners, private developers, public powers, middlemen, etc.) and land purchasers, was operated within the machinery of legal and illegal land market. Second, it was relevant to go deeper into the relationship between the law, which confers ownership, and the right of occupant use (land holder, Hayza). Also, to observe the effects of the procedures of regularisation or adjustment of the right of land use when these procedures ignore the prevailing legal system, which is based on an admixture of customary and its positive law. The idea was to examine the impact of the DPUEA on formal and informal land markets in Kotor. Third, the linkage between the legality and land systems governing the right of land use was studied as it constituted the driving force of the urban growth in each zone of the DPUEA. Fourth, it is vital to examine, sustain and encourage peoples’ process within their environment and how they managed to accelerate the delivery of land plots. Thus, a new mode of urban management has been established among the stakeholders and the consultant. This mode relied on transparency, trust, efficiency and accountability. Consequently, a bridge of trust was built between the consultant and the stakeholders through which a collective planning process was established. Within this context, the preparation of the DPUEA was carried out.

4.2. Main stakeholders in the DPUEA preparation

Five actors were associated with the preparation of the DPUEA: members of public agencies, small farmers, landlords of agricultural areas, middlemen and private developers, all of whom participated in one way or another in preparing and accelerating the mechanisms of the DPUEA.

The public bodies’ representatives were formulated from members of the GOPP, GDPUD and engineering officers in the local municipality. The latter contributed side by side with stakeholders in all stages of the DPUEA. The other two bodies were engaged in monitoring and evaluation process of the DPUEA. Due to the variation of the background of public bodies in planning process, and a lack of awareness of what is going on the ground of the DPUEA, their contributions were limited and considered as impediments in finalising the DPUEA. The reviewing processes of the DPUEA had to pass through several departments in the GOPP and its regional office by which it was treated as desk work, regardless of either what is going on the ground or the time consumed. The landlords were the second actors, who owned small land parcels on the DPUEA. Those landlords had helped the consultant in identifying the physical boundary of their land parcels and expressed how they would like to see their land sub-divided. The DPUEA areas were revisited by the landlords to ensure that their land parcels’ boundaries were correct, to measure the proposed local road network and to link them with the rest of the city. The third actor was the private enterprises who bought large land parcels in key locations of agricultural areas inside the city’s official boundaries. They had a future vision for the processes of formal urbanisation on agricultural areas, as a natural output, and/or as a dynamic process of the increasing demand of housing plots close to the city. These private enterprises had found a good chance for land speculation and accelerated illegal land subdivision inside the boundary of the DPUEA. The fourth actor was salesman, broker or middleman who was accelerating the purchase of land plots on agricultural areas and encouraged further invasion to agricultural land. Those people have a very astute knowledge of landlords and how much land he/she possesses; even more, they knew the exact measurement of landowners land parcels. Also, they knew how the land will be allocated within the proposed local road network.

4.3. The process of the DPUEA

The DPUEA was prepared only after the ministerial approval of the GSUP of the city. The city was revisited in early 2012 and identified different areas of the DPUEA; consequently, it was divided into six zones (see ).

In order to prepare the DPUEA, the following studies were undertaken. The first step revisited the outputs of the GSUP, and planning regulations for each zone of the DPUEA were identified, including: land uses, social services, road network and access to public utilities. Since the GSUP was prepared in 2010, many illegal housing developments had taken place on the DPUEA. These illegal housing developments followed the planned internal roads and followed the layout jointly developed. The second step was the identification and collection of data of the current situation of each zone of the DPUEA, including; land ownership, natural landmarks (canals/ drainage), existing utilities (drinking water, sewage stations) and road networks. The third step was the examination of planning regulations for each zone, such as; land use and activities, organisational lines for buildings, front side and back recessions of land parcels, size of land plots, floor area ratio, building heights and main and secondary road networks (paths and widths). Several meetings were held between the consultant and the stockholders. Specific results were reached in this way: first, the building local capacity, which strengthened the participatory approach in the city for land allocation plans; second, the identification of land transaction, official and unofficial land’s documents, inheritance land, physical administration and security of tenure; and finally, the linkage of old urban areas of the city with the DPUEA. This has helped in measuring the land value before and after the implementation of the DPUEA. It calculated that the land value has risen to around 200% over its price before the preparation of the DPUEA.

Depending on a GIS model that was provided in the TOR for the DPUEA, the land uses of the DPUEA were surveyed and recorded ( and ). The output data of the existing situation of the DPUEA covered the following aspects: city administrative boundaries, land aspects (land parcels, land tenure, land prices), scattered residential building aspects, non-residential buildings and finally basic urban utilises (water, sewerage, roads and electricity network). The output maps analysed agricultural lands and land plots in terms of assessment of the driving forces for housing growth, assessment of new urban expansion areas, assessment of actual land values and the identification of a future local road network. The location of various social amenities, as were stated in the GSUP, was secured. The idea was to create a database for the DPUEA as well as to use this data for facilitating the land delivery system for the city. During this stage, the stakeholders were consulted.

5. Collective process

The collective process depended on the main principles of the DPUEA, and the involvement of the main stakeholders in the planning process. A collective action was lunched to reach a final decision and an appropriate plan to satisfy the various needs and requirements of all the stakeholders, as well as to fulfil the requirements of the PBL119 of 2008. This collective action had several phases: the analysis phase, the role of the stakeholders’ phase, the decision-making phase and finally the preparation of the DPUEA plan.

5.1. Process of participation and analysis

The consultant had to set up several meetings with the stakeholders to reach a common vision that would satisfy the wishes of all stakeholders involved in the DPUEA according to the GSUP and its regulations. Conducting interviews and several individual meetings with the stakeholders coincided with the field survey. The fieldwork helped analyse the situation of the DPUEA, and consulted the stakeholders through workshops and meetings to obtain a clear view of the potentialities and constraints of the DPUEA. Registration and transformation of data were set into layer images with grid and vector data within a coordinate system. Data analysis was conceptually divided into two categories: traditional and object-oriented. A wide range of applications were based on each category. Applications based on traditional analysis used query tool for determining distance, proximity, direction, adjacency and connective relationships between mapped features. Using the query tools available in ArcGIS, the output maps were drawn in spatial format to reflect the DPUEA and to present a plan for each zone, which were then discussed with the stakeholders. A comparison was made between the proposed plan and proposed road network (see ). The DPUEA was analysed from the following perspectives, the physical boundary of agricultural land, types of land tenure, land ownership, land parcels size, streets width and road network.

Applications based on oriented analysis were used to make a comparison between different areas of the DPUEA by analysing the following variables: net area for housing blocks, percentage of land to be allocated for road network, purposed ratio of built-up area to total zone’s size, and various amenities according to the PBL119. Other variables include replacement of deficit land plots not matching with the proposed road network, finding the expected number of land plots needed to relieve overcrowding, upgrading deficient land plots to become economically feasible at start of planning period, determining the expected number of population and density for the proposed built up area (number of persons/Feddan) and finally estimating what types and standards of housing plots could be obtained for given levels of affordability to bring it up to a defined standard. Complex relationships between various variables were reached. and present a summary of statistics (housing blocks areas, size of road network, road network size as percentage of the total area of each zone of the DPUEA etc.) of a field or fields from the related database, based on a selected set of geographical features that were achieved and discussed with the stakeholders.

Table 5. The main targets of the GSUP for Kotor city.

Table 6. Various indicators for each zone of the DPEA.

5.2. The role of the stakeholders

The field survey recorded all land and housing plots with their characteristics (land size, physical boundaries between land parcels, land ownership, types of services), the existing layout pattern and all of this information had been recorded in GIS-base maps. Initial layout pattern of the DPUEA drawn by the residents was provided to the consultants and compared with the field survey; some amendments were made on the ground to fit with the current status of each zone. Several meetings were conducted with the stakeholders to elicit their opinion on how they would like to see their area developed, and thus the zone’s layout pattern was agreed upon among the stakeholders and the consultants (see ). This agreed layout pattern was based on conserving the existing situation, avoiding any destruction of landownership and protecting traditional neighbourhoods and streetscapes to preserve existing amenities. It also enabled the installation of local road networks, even though the subdivision of land parcels was carried out according to the wishes of the landowners, allowing mixed activities, preserving real estate assets, improving the standard of living and thereby alleviating poverty levels.

The process of collective process for the DPUEA was formulated as follows. First, the stakeholders identified a range of options that gave residents the flexibility in choosing the setting or the size of the land plots to construct their housing, the way in which their resources are invested, or a combination of these. Second, stakeholders introduced arrangements among themselves that accelerated illegal/semi-legal land subdivision. They acted freely outside the official legislation and they exercised their own control over their environment, building when and what they liked without regulation or any restrictions imposed by the local authority. Third, the stakeholders not only embody the local knowledge to be accessed, but their participation presents an important entry point to the political decision-making needed for exploring differing viewpoints and initiating negotiations leading to coordination if not cooperation. Fourth, the stakeholders have relied on the great autonomy in their environment, with enhanced participation in the land allocation process, in the timespan for determining their housing plots and in protecting the environment. Fifth, the stakeholders have relied on their culture and their talent and the symbolic aspects of their lifestyle by which land allocation and settlement form was formulated within each zone of the DPUEA. Thus, the project encouraged culturally valid, homogeneous neighbourhoods, locating people in physical and social space reflecting the resident’s identity.

To achieve sustainability, the DPUEA structurally utilised participation in the decision-making process; decentralised decision-making at the national level, effectively takes advantage of stakeholders’ participation as a well-informed source on local situations. The consultant was required to provide the technical know-how and assumed the role of facilitator in enabling local voices to be heard. The question of the sustainability of the idea of the stakeholders’ participation (see ) with slight modifications to meet the PBL119 requirements, the installation of utilities and the needs of the urban poor emerged. This led to a semi-formal institution of building procedures and planning regulations, in which a form of balance among creativity, sustainability and maintenance of a well-built environment was achieved to meet the needs and requirements of the residents and what they were willing to play, was reached. The goals were to reduce central control, to increase economic, social and personal development and self-determination, and to increase personal and stakeholders integration based on the satisfaction of vital needs rather than on the misdistribution of basic goods and services for an artificial reaction to consumer’s needs.

The final output of each zone of the DPUEA offered a plan that tied up the organisational loose ends and specified the role of each stakeholder in the implementation process (who does what, when, how and where: see ). It identified financial responsibilities and ensured that each contributor had agreed to his or her role within this sphere before implementing the plan. It was apparent that impediments arising within the collective process are readily traced to deficiencies in the establishment process or academic planning process. Land allocation in the DPUEA facilitated by being released from the complexity of institutional and legalisations control of the official bodies, allowed the stakeholders to design their own urban pattern to match their financial status, keeping within the modesty of their tradition. The layout pattern drawn by the stakeholders had become more sensitive internally, sustainable and climatically appropriate. The circulation systems within each zone of the DPUEA have reflected the social ties of the residents with three types of streets: the cell boundary streets forming the boundaries of residential cells, the major intra-settlement arteries serving the third level in this hierarchy, and the passages within the cells, which were public and semi-public (known as hara-darb-atfah).

5.3. The process of decision-making

Based on the principles of working with the stakeholders, several output maps were produced from GIS and presented and discussed with the stakeholders. There were three categories of decisions that GIS contributed to the planning process of the DPUEA. The first group was in the traditional areas of application of GIS, in disciplines such as land use. In this field, GIS was initially used as a means of speeding up the processing of spatial data, for the completion of activities that contribute directly to land allocation. In this context the automated production of maps had a role similar to that of data processing in planning. The second group of decisions was in the fields of a new area for housing blocks analysis. Although the spatial components of such decisions were emphasised on housing blocks analysis, it obtained a clear visual image about a new area for housing location. In the future these analyses would be incorporated into GIS, providing superior interface and database components to work with the housing plots typologies. The third group of decisions included those where the importance of both spatial data and modelling were somewhat neglected at present. In disciplines such as land market, additional possibilities for analysis were provided by the availability of increasing amounts of spatially correlated information; for example, relationship between housing blocks and local road networks. Furthermore, the geographic convenience of land delivery supply relative to customers’ affordability was an important tool of land market driven competition. The main output was visualisation of data, model specification and spatial statistics in a study of new areas for the DPUEA in Kotor city (see ).

5.4. The impediments of the DPUEA

The preparation of the DPUEA took around one and a half year, and it has yet to be approved. The technical work was finished within a period of 6 months, while the evaluation and reviewing processes are still under way. Due to these long procedures, the public bodies helped indirectly in pushing the DPUEA into accelerating the mechanisms of urban illegality within the city. Also, because of the complicated procedures and long time frame to approve the DPUEA, the agricultural areas adjacent to the city’s boundary had attracted further intruders to the city who were seeking affordable illegal housing sites close to the city. This had led to flourishing a new urban informality outside the city’s approved boundary.

The delaying of approving the DPUEA had encouraged the landlords in increasing their land prices. These attitudes of the landlords had accelerated the processes of informal urbanisation of adjacent agricultural lands located outside the city’s boundary. The main premises for this growth were the rapid land speculation, and the increasing demand for such plots. Unfavourable farming conditions were another factor accelerating illegal subdivision of agricultural lands. In cases where the farmers pursue cultivating their plots, their propinquity to urbanising areas raises problems: children and domestic animals from neighbouring dwellings spoil their crops, shadows cast on crops by adjacent dwellings, etc. All of these reasons have initiated and encouraged the formulation of informal land markets on the periphery of the city’s boundary.

In the case of the DPUEA is completed and approved, citizens of the DPUEA will face many legalisation obstacles. First, in order to apply for a building license according to the PBL119, the applicant has to obtain a Validity Certificate of the location according to the PBL119 (VCLPBR) for his/her own land plots from the engineering department at the municipality, stating the location and characteristic of the land plot and its planning regulation. To issue this certificate, the land parcel has to have an official land sub-division by which it should indicate organisational building lines (Khotoot Tanzeem) between the different land parcels. Most of the development lands newly added to the city do not have a legal land sub-division; therefore, the applicant would not be able to obtain a VCLPBR, nor a building license.

Second, in order to officially apply for a land sub-division project, all land plots within a large land parcel should apply to the Property Declaration Department (PDD) (Shahar el Aquary), and must present official documents stating the size and location of land plots and the names of their original owners (official registration documents), as stated in the PBL119. In Kotor city, 80–90% of land tenure has de jure tenure recognition, which is not acceptable in the PDD. Therefore, the citizens would not be able to obtain the permission for an official land subdivision, nor a VCLPBR for their own land plots.

Given that four years have apparently passed since the initial planning exercise was handled out, revisiting the city in the late 2014 was essential to interview some of those involved on the ground. Some stakeholders in the city are suffering from not being able to access neither official building licenses nor legal land sub-division due to several emerging institutional obstacles. First, the continuation of lengthy procedures and the lack of awareness of the importance of accelerating the urban development in the city have forced the citizens to act informally. This delay is an open invitation for speculators to illegally subdivide agricultural land recognized as a new urban expansion area, and land prices have risen to a degree beyond the affordability of the urban poor. Second, illegal land sub-division and informal housing development inside the GSUP occurred (see and , and ). This process of illegality has followed the main road network as recommended in the GSUP. However, people who bought land in illegal land sub-division areas are not able to obtain a building license as they must apply, according to the PBL119, officially for a land sub-division project, and this would not be allowed until the DPUEA can be implemented and approved from the responsible governor. Third, arbitrary informal housing development are stretched vertically; where many floors are informally clinging to the existing buildings (around 0.4 thousand housing units in Kotor city). Finally, because the land prices inside the official Hayez rose, more agricultural lands, outside the official Hayez, are illegally converted into informal housing development. It estimated that around 65 feddan are informally developed outside the official Hayez of Kotor city, upon which informal land markets flourish.

6. Lessons learned

Throughout the previous discussion, it appeared that the GSUP was a blue print plan and neither it met its objectives nor did it prevent further urban sprawl on agricultural areas adjacent the official city boundary. This failure was due to a mismatch between what is done on the ground and what can be theoretically gained out of the prevailing law of 2008. Slow performance of the public bodies in the implementation of urban plans cannot compete with the speed of urbanisation on the ground. Therefore, there was a big gap between the application of the PBL119 and urban planning practice. This gap was activated through the conflicts between institutional and legalisation guidelines, which resulted in long complicated procedures, dense evaluation processes that passed through a long timespan, which caused delays in the final official approval for both the GSUP and the DPUEA. Also, the restrictions that were imposed on the land subdivision project have prevented the citizens from obtaining official building licenses. Alternatively, the residents were forced to illegally construct their housing on the proposed DPUEA as well as conquering agricultural land adjacent to the official Hayez of the city. The delayed and complicated procedures in approval of the Kotor’s GSUP have prevented the starting of the DPUEA. In summary, the GSUP did not succeed in its objectives nor did it preserve the agricultural areas. It could be said that two types of urban informality have flourished, one inside and the other outside, the official approved Hayez, by which more agricultural lands were converted into urban informality. Also, the GSUP of the city has given rise to new obstacles for people to obtain a license for building and/or for land subdivision projects. Furthermore, preparing GSUPs for Egyptian cities cost more than US$ 25 million, all of which are considered squandering of public fund.

Despite the failure of the GSUP in meeting the residents’ needs for housing and other amenities, the stakeholders’ involvement in the DPUEA have managed to communicate with each other in determining their destiny by which a collective process flourished. The collective process was to scale up the development process on affordable basis at a faster rate than the government can achieve. By ‘scaling up’ the aim was to reach the greatest possible number of poor people, and to motivate and empower the greatest number of stakeholders to take control of their own development. Collective processes in Egypt have offered two advantages for the majority of the urban poor: the first was that the collective process in land markets encouraged the urban poor to obtain a legal and/or an illegal house site with reasonable basic services and suitable access to income-earning possibilities. The second advantage of the collective process in land markets was operating outside the official building and planning regulation, by which freedom was offered to the urban poor to act in and formulate the housing processes according to their needs and requirements depending upon their incremental change of their socio-economic status.

Social networks have created collective processes, between individuals or among the members of a community, by which the complex relations among stakeholders, planning interventions, land and property development processes and distributive outcomes could be explored, are robustly grounded. In the context of social networks, the collective process achieved and provided greater flexibility within the physical environment than what was found in organised areas. Also, the formulation of informal urban land markets is due to inefficient government delivery system of reasonable sites compatible with the socio-economic status of the urban poor. These markets have been formulated through various bodies, of which some are attributed to public and others to private developers. The formulation of the informal urban land markets has been encouraged or at least facilitated – directly and/or indirectly – through various governmental bodies, which accelerated the mechanisms of these markets to be a part or integrated with land market of a given environment. The focus of this article is ultimately on achieving large-scale, sustainable impact of the collective process. Such a focus necessarily includes the environment/context within which such initiatives would emerge and would grow.

In practice, it is up to the decision-makers, city authorities and stakeholders to work together to identify what is of critical importance to them, and to utilise the capacity of community members to provide what is required. Lower-income groups can no longer wait to solve the complicated procedures, nor can afford the new high prices and they have to look elsewhere for cheaper housing plots in younger settlements at other further locations. Their savings are usually channelled to: starting a business to ensure continued improved economic status and securing a dwelling; sometimes both are combined in the same structure, a simple equilibrium that the majority of the urban poor are looking for. The experience of Kotor’s residents demonstrated their capacity to initiate, organise and manage their own development process with little or no support from either central government or local authorities.

Understanding the process of the DPUEA of the city, collective process and the stakeholders’ roles, would enable the state and housing professionals to alleviate urban informality within formal planning zones, and would accelerate land delivery system to promote socioeconomic development and alleviate poverty. Reviewing the GSUP, the institutional and legalisation guidelines have become vital, from the perspective of local powers desiring control, as various potentialities, constraints and Egypt’s magnified political goal of saving and rescuing agricultural land have arisen. Furthermore, a clear understanding of a collective process and people’s needs and requirements for housing plots must be accomplished in order to achieve a sustainable urban development within the DPUEA. The collective planning process with ‘technical enablement’ should be encouraged, and, the government should play the role of an agent for urban sustainability in order to magnify the political goal of saving and rescuing agricultural land and to encourage a guided sustainable urban development in the back desert in Egypt.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed M. Soliman

Ahmed Soliman is currently working as an emeritus professor of urban planning and housing studies and formerly was the Chairman of Architecture Department in the Faculty of Engineering at Alexandria University (2007–2012). He has published widely on issues of urban planning and informal housing settlements in several distinguish international journals and contributed in chapters in various books. He is the author of A Possible Way Out: Formalizing Housing Informality in Egyptian Cities (2004), University Press of America, USA.

Notes

1. For further debate on social capital, see Adler and Kwon (Citation2002) and Jackson (Citation2010).

2. The General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP) is the official planning organisation in Egypt responsible for establishing and approving planning projects for both urban and rural areas. There is a committee within the GOPP for reviewing and approving planning projects submitted, after which the GOPP has to send the approved plans to the Ministry of Defence to get the final approval. Nobody in Egypt can discuss or review the decision of the Ministry of Defence, as its decision concerns the National Security of the country.

3. The stakeholders were involved in and dealt with all phases of the project and of the DPUEA, and constituted seven groups as follows: representatives from the local municipality headed by the Mayor; representatives from the Popular Council headed by the Chairman; representatives from planning departments of the Governorate; representatives from NGOs; representatives from the real land developers; representatives from local citizens (farmers, semsar, etc.), representatives of landlords; and representatives from the GOPP who were acting on behalf of the central government and were reflecting the planning policies of the GOPP.

References

- Adler P, Kwon S. 2002. Social capital respective or a new concept. Acad Manage Rev. 27:17–40.

- Alexander C, Silverstein M, Angel S, Ishikawa S, Abrams D. 1975. The Oregon experiment. New York (NY): Oxford University Press.

- Barker I, Linden R. 1985. Community crime prevention. Ottawa: Ministry of Solicitor General Canada.

- Barton S. 1977. The urban housing problem: Marxist theory and community organizing. Rev Radical Polit Econ. 9:16–30.

- Bourdieu P. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buckley R, Kalarickal J, editors. 2006. Thirty years of World Bank shelter lending what have we learned? The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Washington: World Bank.

- CAPMAS. 2006. General statistics for population and housing: population census. Cairo: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics.

- CAPMAS. 2012. General statistics for population and housing: population census. Cairo: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics.

- Cities Alliance. 2008. Slum upgrading up close: experiences of six cities. Washington: City Alliance.

- Collier D. 1976. Squatters and oligarchs. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Collier P. 2002. Social capital and poverty: a microeconomic perspective. In: Grootaert C, Van Bastelaer T, editors. The role of social capital in development: an empirical assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dasgupta A, Beard V. 2007. Community driven development, collective action and elite capture in Indonesia. Dev Change. 38:229–249.

- De Soto H. 1989. The other path: the invisible revolution in the third world. London: I.B. Taurus.

- De Soto H. 2014. Formalization of business and real estate in Egypt. Paper presented at: Egyptian Center for Economic Studies (ECES); 2014 Jan 18; Cairo.

- Egypt Human Development Report. 2010. United Nations Development Programme, and the Institute of National Planning, Egypt.

- Engles F. 1970. The housing question. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Fathy H. 1972. The architecture for the poor, a phoenix book. Chicago (IL): The University of Chicago Press.

- Fawaz M. 2008. An unusual clique of city-makers: social networks in the production of a neighborhood in Beirut (1950–75). Int J Urban Reg Res. 32:565–585.

- Ferguson B, Smets P. 2010. Finance for incremental housing; current status and prospects for expansion. Habitat Int. 34:288–298.

- GOPP. 2006. Terms of reference for strategic urban plan for Egyptian cites. Cairo: The General Organisation for Physical Planning.

- Hamdi N. 2004. Small change: about the art of practice and limits of planning in cities. London: Earthscan.

- Hasan A. 2001. Working with communities. Karachi: City Press.

- Healey P. 2003. Collaborative planning in perspective. Plann Theory. 2:101–123.

- Jackson L. 2010. Influences on financial decision making among the rural poor in Bangladesh [ unpublished PhD thesis]. Penrith (NSW): School of Marketing, The University of Western Sydney.

- Landman K, Napier M. 2010. Waiting for a house or building your own? Reconsidering state provision, aided and unaided self-help in South Africa. Habitat Int. 34:299–305.

- Layton RA. 2009. On economic growth, marketing systems, and the quality of life. J Macro Mark. 29:349–362.

- Narayan D, Chambers R, Shah M, Petesch P. 2000. Voices of the poor: from many lands. New York (NY): The World Bank and Oxford University Press.

- Perlman J. 1976. The myth of marginality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Soliman A. 1985. The poor in search of shelter: an examination of squatter settlements in Alexandria, Egypt [ unpublished PhD thesis]. Liverpool: The University of Liverpool.

- Soliman A. 2010. Rethinking urban informality and the planning process in Egypt. J Int Dev Plann Rev. 32:119–143.

- Soliman A. 2012. Tilting at pyramids: informality of land conversion in Cairo. Paper presented at: Sixth Urban Research and Knowledge Symposium 2012 World Bank; Washington (DC).

- Soliman A. 2015. Breaking with the past to unleash urban informality potential: illegal/legal approach for land readjustment in Egypt. Paper presented at: 2015 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty; Mar 23–27. Washington (DC): The World Bank.

- Tellis W. 1997. Introduction to case study. Qual Rep. [Internet]. [cited 2013 Apr 17] 3. Available from: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR3-2/tellis1.html

- Toth O. 2009. Strategic Plan for an Egyptian village: a policy analysis of the loss of agricultural land in Egypt. M.Sc. urban environmental management submitted to the School of Planning of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning, Wagering University.

- Tunas D, Peresthu A. 2010. The self-help housing in Indonesia: the only option for the poor? Habitat Int. 34:315–322.

- Turner J. 1976. Housing by people. London: Marion Boyars Publishers.

- Turner J, Fichter R. 1972. Freedom to build: dwellers control of the housing process. New York (NY): The Macmillan Company.

- UN-HABITAT. 2008. The State of African Cities 2008: a framework for addressing urban challenges in Africa. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- UN-HABITAT. 2012. The State of Arab Cities 2012: the Challenges of urban transition. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- Ward P, 1982. Self-help housing: a critique. London: Mansell Publishing.

- Woolcock M, Narayan D. 2000. Social capital: implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Res Obser. 15:225–249.

- Yap K, De Wandeler K. 2010. Self-help housing in Bangkok. Habitat Int. 34:332–341.