Abstract

Social sustainability is gaining importance in the international urban development context; however, in India, the concept is unclear and under-represented. New approaches and tools at the level of urban policy, design and implementation are highly biased towards environmental sustainability focussing on “smart” technological innovations. This scant focus, coupled with massive and inequitable urban growth, is resulting in social crises that not only pose danger to the country’s stability but also represent some of the fundamental challenges to its sustainable future. Based on a detailed review of the literature on social sustainability, this paper explores its meaning and sets out its core components. It calls for humanising Indian cities and argues that a more comprehensive approach to the constituent but neglected “social” dimension of sustainable development which goes beyond the technical aspects of solving infrastructure-focused social issues to creating built environments that nurture strong urban communities is necessary. Analytical findings are translated into the social sustainability framework, which suggests a combination of (micro-level variables of) bottom-up and (macro-level variables of) top-down approaches in its implementation, because nurturing social sustainability in cities needs both, planned context and emergent actions.

1. Introduction

Cities play a vital role in the realisation of a sustainable future. This is particularly relevant to the developing world with its rapid urban growth and severe sustainability challenges due to lack of resources, increasing poverty, inequity and susceptibility to climate change. With an influx of another 350 million people, fast developing nations such as India will witness its cities becoming home to more than half of its total population by 2050 (more than 875 million people). Such vast scale and speed of urban growth will put tremendous pressure on the existing infrastructure, land and other natural resources as well as traditional sociocultural settings that support a particular quality of life of its citizens, hence making Indian cities more vulnerable to non-sustainable design and development practices.

Sustainable urban development, which is now widely accepted as achieving a balance between the social, economic and environmental dimensions, is therefore, forming the basis of the country’s new development guidelines. Yet, environmental performance and technological innovations have come to dominate the thinking on sustainable cities in India (e.g. the Indian Green Building Council’s rating systems (LEED India Citation2011) or the Government of India’s (GOI) more recent National Mission on Sustainable Habitat (NMSH Citation2010)). Much thinking, effort and investment is focused on reducing energy consumption, developing sustainable transport, greening buildings to address the challenges of climate change through a combination of modern planning, technological infrastructure and smart designs. The social dimension is highly under-represented, focussing narrowly on infrastructural development and poverty alleviation through slum upgradation programmes (see, e.g., Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY) and other GOI’s social development policies in urban areas). This narrow focus is at best ignoring and, at worst, destroying the social infrastructure that makes Indian cities work and indeed is fundamental to their character (Hemani et al. Citation2012). Despite it being the fastest growing economies of the world, India’s Human Development Index ranks 136th amongst a total of 187 countries (Human Development Report Citation2013, UNDP). This re-emphasises the fact that design for social sustainability in cities is not just a technical matter of solving hard social issues through infrastructure provision, but also about enabling urban environments to build and nurture strong communities for a cohesive society and sustained inclusive growth of our cities. A more comprehensive approach to social sustainability that looks at all its elements in an integrated manner is, therefore, the need of the hour.

This paper does not intend to provide solutions to social sustainability in India but assesses the “need for it” in the current urban development context and presents a detailed “understanding for it”. To do so, Section 2 (Sustainable urban development – a global issue) of this paper puts the above arguments in the global and national urbanisation context, followed by an in-depth examination of the concept of social sustainability. before an in-depth examination of the concept of social sustainability. Section 3 explores the social nature of sustainability and reviews it in the urban development policy context. Here it focuses on two aspects “social” and “urban” policies in India. Section 4 discusses the meaning of social sustainability and conducts an exhaustive review of its themes presented so far by various authors. Based on this, key dimensions and components of social sustainability are identified. In Section 5, the paper considers the role of bottom-up approaches at the scale of neighbourhood in achieving the wider sustainable development goals. In Section 6, the key dimensions of social sustainability, their components and their relationship to the built environment are discussed. These form the building blocks that contribute to the social sustainability assessment framework laid out in Section 7.

2. Sustainable urban development: a global issue

2.1. An urban world: continuing challenges and opportunities

Cities, since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, have grown rapidly in both, size and power. The twentieth century, however, saw a new and more striking era of global urbanisation. Presently, over half of the world’s population of 6 billion lives in cities, as compared to 10% of 1.6 billion in 1900 and about 3% of the 900 million in 1800. By 2050, over 70% (6.3 billion) of the projected 9 billion world population is expected to be urbanised (UNFPA Citation2007). A closer look not just at the scale but also at the nature of contemporary trends in urbanisation reveals that this demographic forecasting does not simply imply that most of the world population will be living in cities, but that intense urbanisation does and will continue to have a significant impact on global sustainability, as cities today not only concentrate majority of the earth’s environmental problems but also compound intense social issues such as poverty, inequity, water and food insecurity, increasing crime, weakening social ties and deteriorating quality of life, to name a few.

This shift towards an urban world will be driven by urbanisation in developing countries, whose population will be more than double, increasing from 2.5 billion in 2009 to almost 5.2 billion, by 2050 (UN-HABITAT Citation2008). With a projected gain of 70 million new urban residents each year, this massive urbanisation will bring about even greater challenges. On one hand, these cities command an increasingly dominant role in the global economy as centres of both production and consumption while on the other, their rapid growth and transition gravely outstrips the their capacity to provide adequate and affordable basic services and infrastructure for their citizens, also altering their physical forms, which further contributes to unsustainable urban living (e.g. travel behaviour and accessibility, social patterns and equity, economic viability and resource efficiency, etc.).

From such a perspective, intense urbanisation may be seen as a negative phenomenon challenging global sustainability. Yet, paradoxically, it is also anticipated to create solutions for a sustainable future. Cities are seen not only as engines of economic acceleration, with greater opportunities for growth and development, but also physical manifestations of diverse cultures, centres of innovation, industry, creativity, knowledge as well as materialisations of peoples’ ideas, ambitions and dreams (UN-HABITAT Citation2008). Cities concentrate resource consumption and pollution into a small area, making it more visible but not necessarily increasing it on a per-capita basis. They can, instead, be highly efficient because of the advantages of scale and proximity, making provision of sustainable infrastructure, service and amenities less costly and more widely available. One of the great advantages of cities is that they are also huge engines to improve the standard of living of their citizens and are thus seen as major force behind poverty reduction and progress towards other Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). For a given standard of living, opportunities for advancement and multiplicity of choices, cities may be the most benign form of human settlement environmentally, socially and economically. Urban experts and policymakers are increasingly viewing cities optimistically, thereby inquiring into ways of harnessing the benefits of urbanisation.

2.2. An urbanising India: towards a majority in the cities

India, a very “reluctant urbanizer” so far, at around 377 million people in towns and cities, represents less than a third of its total population. Yet, it is the sheer size of the country’s population that puts it on the global urbanisation map. India’s large rural population means that it is likely to experience a huge process of urbanisation in the coming decades. It is estimated that by 2050, India’s urban population will represent more than half of the entire population of the country, around 54.2%, constituting more than 875 million people. This will be one of the largest rural–urban migrations the world has seen, creating not only huge economic opportunities but also great sustainable development challenges ().

Urban growth in India, geared to the needs of global capital, has been an unbalanced process. The country’s economic growth (rise in Gross Domestic Product) is coupled with great (economic, social and spatial) inequalities in cities, which are not only related to income and consumption expenditures, but reflect entrenched patterns of urban development and ownership of physical space that limits certain segments of the society from gaining the full benefits of city life (Feitosa et al. Citation2007) also evidenced and reinforced by the phenomenon of urban sprawl. The country’s growing urban areas, which compete for “world-class” and “global” tags, further fail to accommodate Indian traditional sociocultural structures, which are constantly being reframed, giving new meaning to urban communities that are becoming more individualistic and fragmented. Such social crises in cities are also associated with other grave issues including isolation and social disorder, crime and fear of crime; cultural and religious tensions; lack of community and civic participation; poor health and education; low social capital and poverty as well as social exclusion and inequity, all of which are inter-related and may be formed as a function of spatial design. Social conditions manifested in the urban environments today, and perhaps even more importantly in the years to come, remain one of the greatest global challenges facing the world today and are indispensable requirements for sustainable development.

According to a McKinsey Global Institute 2010 report, India’s rapid urbanisation over the next three decades cannot be contained within the existing stock of cities. As a response, India is building new urban centres, some even larger than 350 km2, with the introduction of ‘smart’ concepts that leverage information and communications technology (ICT) to greatly improve the productivity, lifestyle and prosperity of its citizens. The GOI has allocated a budget of USD 1.2 billion to revolutionise the country’s urban landscape with the development of two smart cities in each of India’s 29 states including seven along the 1500 km industrial corridor, thereby attracting foreign investments. The key features of a smart city, as per the vision of the Ministry of Urban Development’s “smart cities – Transforming Life, Transforming India” lie at the intersect between Competitiveness, Capital and Sustainability. It states that “The smart cities should be able to provide good infrastructure such as water, sanitation, reliable utility services, health care; attract investments; transparent processes … and various citizen-centric services to make citizens feel safe and happy”.

The development of 100 smart cities and the new urban renewal mission for 500 cities are two most ambitious schemes of the new government. In addition, several other new-generation large and small greenfield cities are being created across many Indian states to deal with overcrowding and to cater to India’s growing middle class. Such initiatives may be seen as a positive way forward to engulf the massive Footnote1urban growth; however, as clearly evident from the three case studies in , despite the fact that the proposed new cities concentrate a great deal on smart governance, smart energy, smart environment, smart IT and communication, smart transportation and smart buildings, there is little or no focus on aspects of social sustainability, such as fostering social capital, cohesion, equity and inclusion through design and policy. Smart cities are not just technologically renovated eco-cities but also people-oriented human-scale cities that acknowledge the importance of different voices, reduce social inequalities by ensuring equal opportunities in all spheres of social and collective life as well as improve overall well-being of all its citizens. As India is all set to give shape to its futuristic smart cities, there is clearly a pressing need to develop a stronger conceptual understanding of the social dimension of sustainable development that links to and is grounded in real-life policies and practices, just as the recognition of physical, environmental and economic challenges in building these new cities.

Table 1. Case examples of planned liveable and smart cities in India.

3. The social dimension of sustainability

3.1. Exploring the social nature of sustainability

Today, adopted as a common political goal and everyday axioms, the concepts of “sustainable development” and “sustainability” have emerged over an extended period of international discourse since the 1960s (UNEP Citation1972; IUCN Citation1980; Carlson Citation1962) as a result of the growing awareness and concern, particularly for environmental issues. However, this environmental disquiet that began in the 1960s, slowly became a broader movement that recognised the interconnected ecological, social and economic consequences of development (McKenzie Citation2004; Littig & Grießler Citation2005; Cuthill 2010). Sustainable development entered the global political arena in 1987 following the Brundtland report by the United Nations Commission on Environment and Development (UNCED). In this report, the concept appeared as a balance between social, economic and environmental objectives and was defined as the “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED Citation1987). Although there was much criticism about the Brundtland definition, mainly in relation to the vagueness and lack of clarity associated with its meaning, there was a general agreement that all the three dimensions of sustainability should be incorporated into the development context from the beginning and on an equal footing. In 1992, the programmes outlined in “Agenda 21”, an action plan adopted at the Conference on “Environment and Development” (also known as “Earth Summit”) held at Rio-de Janeiro also went beyond ecological sustainability to include other dimensions of sustainable development, such as equity, economic growth and participation. The concept further evolved through international discourses such as the Kyoto Climate Change Conference (1997) and the more recent World Summit on Sustainable Development at Johannesburg (2002) and Rio+20 (2012).

During the 1990s, sustainable development also became interlinked with the term “sustainable cities”. While initial interpretations in this context concentrated on a narrower “ecological perspective” (Blowers & Pain Citation1999) focussing on the minimising of pollution, resource depletion and condition of living environment (Weingaertner & Moberg Citation2014), the early debates on “sustainable cities” were also simply associated with limiting the ecological footprint through efficient infrastructure, such as waste management and recycling, reduced car dependency and greater use of alternative modes of transport (Bromley et al. Citation2005). The social issues were taken into account (Colantonio Citation2007) when contemporary approaches to development led to inequitable outcomes and, in some cases, even “breakdown” of community (Greider Citation1997; Saul Citation1997). This further emphasised the fact that social sustainability cannot be merely seen as social tolerability of environmental policy measures. Hence, the term “brown agenda” (besides the “green agenda”) was coined to deal with issues relating to environmental conditions in which the urban population, especially the urban poor, were living. Further discussions revolving around issues of equity and environmental justice (Haughton Citation1999; Polese & Stren Citation2000) and topics such as “people-centred development” or “sustainable human development” and, more recently, “social design” strengthened the relevance of social aspects in this debate and has hence gained increasing acceptance, especially over the last 10 years. Internationally, therefore, issues such as social cohesion, cultural values, economic stability, equal opportunities, accessibility, health and well-being are increasingly becoming more relevant (ODPM Citation2003) to deal with sustainability crises. Similarly, within companies, social sustainability goals are being mandated through the corporate social responsibility programmes. Sustainable development is thus slowly gaining recognition in global and local sustainability agendas, development goals and planning policies. It is being seen more as a complex social process rather than a straightforward technical or technological issue. As Omann and Spangenberg (Citation2002) argue, emphasis on the social dimension is essential for two reasons; first, it is a constitutive dimension of sustainable development (from the outset of the definition of Brundtland Commission, WCED Citation1987) and hence, important in its own right as much as in its interaction with the other dimension; second, it is a necessary precondition to achieve the environmental and economic sustainability objectives as urban environmental challenges are primarily social issues and largely a function of human behaviour and economics, which is meant to serve people, rather than the view that people serve economic interests.

3.2. Situating social sustainability in the Indian policy context

For India, the idea of sustainability is not new and existed long before its formal adoption as a political and ethical concept. It was embedded in many age-old religious philosophies and indigenous practices that promoted a culture of social justice and environmental consciousness. Even Gandhian thought, although criticised for being romantic idealist like those of Schumacher (in his book “Small is Beautiful”, 1973), emphasised human-scale development as an ethical response to the stewardship of the environment and humanity. The modern concept of sustainability was later adopted in 1970s out of a politically organised assertion of environmental protection and development of sustainable development theories. India has consistently played an important role in the evolution of an international consensus to tackle major global environmental issues. In 1972, the then Prime Minister of India, Mrs. Indira Gandhi, emphasised, at the UN Conference on Human Environment at Stockholm, that concepts of a shared plane and of global citizenship cannot be restricted to environmental issues alone, but apply equally to the shared and interlinked responsibilities of environmental protection and human development. The country was also an active participant in the process leading up to, and culminating in the convening of the UNCED (1992) and the Earth Summit (2002). India has worked for securing a renewed political commitment for sustainable development, in particular the Rio principles, and to situate Green Economy in the context of Sustainable Development, poverty eradication and inclusive growth during the RIO+20 Summit (2012).

The Indian Government’s commitment to sustainable development is also reflected in specific and monitorable targets for human development and conservation of natural resources, which became part of the country’s Five-Year Plans since the 1990s. Building upon the platform created by the Eleventh Plan (2007–12), the Twelfth Plan (2012–17) aims at faster, sustainable and more inclusive growth. Sustainable development concerns, in the sense of enhancement of human well-being, therefore seem to be a recurring theme in India’s development philosophy, where policies and programmes aim at achieving sustainable development efforts to fulfil its commitment towards social progress, accelerated economic growth and increased environmental conservation.

Yet, an in-depth and critical review of various existing policy documents () suggests that there exist various parallel, but ad hoc, slow-moving and fragmented social, urban and sustainable development policies that barely keep pace with the rapid pace of growth of Indian cities. As a result, there is no synergy between these various efforts, and the lack of convergence in thinking and in action has reduced their cumulative impact.

4. Building the social pillar

4.1. Meaning and interpretations

While there is now a general consensus that all three dimensions, or pillars, of sustainability are equally important and need to be integrated into sustainable urban development initiatives right from conception, the meaning and associated objectives of the social pillar remain vague (Dempsey et al. Citation2011), conceptually the most elusive (Thin Citation2002; McKenzie Citation2004; Littig & Grießler Citation2005), and not given the same treatment as the other two pillars (Cuthill Citation2009; Vavik & Keitsch Citation2010). Colantonio (Citation2007) argues that the concept of social sustainability has been under-theorised or often oversimplified in existing theoretical constructs and there have been very few attempts to define social sustainability as an independent dimension of sustainable development. It is a complex and multifaceted concept, which has often been studied through the lenses of various disciplines and theoretical perspectives (Dixon & Colantonio Citation2008). Chiu (Citation2003, p. 66–67) provides an important analysis of various interpretations of social sustainability and argues that it is usually interpreted from three perspectives: (1) the development-oriented interpretation, which emphasises that development is socially sustainable when it keeps to social relations, customs, structures and values; (2) the environment-oriented perspective, which suggests that development is sustainable when it meets social conditions, norms and preferences required for people to support ecologically sustainable and just actions; and finally (3) the people-oriented interpretation, which emphasises maintaining levels of social cohesion and preventing social polarisation and exclusion.

Defining the social pillar presents a number of challenges, as there are various meanings associated with the term “social” itself. Littig and Grießler (Citation2005) argue that these difficulties in conceptualising social sustainability are due to the fact that there is no clear differentiation between analytical, normative and political aspects thereof and hence people may prioritise one over the other. There are several definitions put forth by different authors from various perspectives; however, there is no single agreed definition, which causes difficulties to interpret its core elements. One of the widely accepted definitions of social sustainability is one by Polese and Stren (Citation2000, p. 15–16), which discusses the concept in terms of both the collective functioning of society and individual quality-of-life issues:

development (and/or growth) that is compatible with harmonious evolution of civil society, fostering an environment conducive to the compatible cohabitation of culturally and socially diverse groups while at the same time encouraging social integration, with improvements in the quality of life for all segments of the population.

While Yiftachel and Hedgcock (Citation1993, p. 140) have defined urban social sustainability in terms of a city’s ability to function as “a long-term, viable setting for human interaction, communication and cultural development”.

In the current sustainable urban development context, Colantonio (Citation2007) recognised that social sustainability is becoming increasingly associated with sustainable community discourse. For example, Davidson and Wilson (Citation2009) identify social sustainability as a life-enhancing condition within communities, and a process within communities that can achieve that condition. The Bristol Accord, 2005, defines sustainable communities as:

places where people want to live and work, now and in the future. They meet the diverse needs of existing and future residents, are sensitive to their environment, and contribute to a high quality of life. They are safe and inclusive, well planned, built and run, and offer equality of opportunity and good services for all. (ODPM Citation2006, p. 12)

Such a definition highlights the physical context in which communities exist and reinstates the importance of physical design for social sustainability. Two other common definitions of social sustainability within the context of built environment or design of cities are put forth by Oxford Institute of Sustainable Development (OISD) and Young Foundation. Based on their work at OISD, Colantonio and Dixon (Citation2009) argue that at a more operational level, “… social sustainability blends traditional social policy areas and principles, such as equity and health, with emerging issues concerning participation, needs, social capital, the economy, the environment, and more recently, with the notions of happiness, well being and quality of life.” The Young Foundation defines social sustainability as,

A process for creating sustainable, successful places that promote wellbeing, by understanding what people need from the places they live and work. Social sustainability combines design of the physical realm with design of the social world – infrastructure to support social and cultural life, social amenities, systems for citizen engagement and space for people and places to evolve.

Thus, recent years have seen notable efforts from academicians and practitioners in various sectors to address the often neglected social aspects of sustainability in terms of defining the concept, developing theoretical frameworks to operationalise social sustainability, and to empirically investigate it in relation to sustainability projects and initiatives. The concept, however, still remains vague. So far, it has no agreed definition, its measurement is problematic and is highly context-dependent; yet, it is gaining increasing resonation as an indispensable pillar of sustainability and thus cannot be ignored or dismissed.

4.2. Key themes and components

In the notion of urban social sustainability, despite of the lack of a common definition, numerous key themes have been identified by many authors. For example, Barbier (Citation1987) states that social sustainability must rest on social values such as culture, equity and social justice; Bramley et al. (Citation2010) focus on equity and community, while Torjman (Citation2000) suggests poverty reduction, social investment and building of safe and caring communities as three priority directions. Colantonio (Citation2008a, Citation2008b) puts forward a comprehensive list of key themes for the operationalisation of social sustainability and argues that more intangible and less measurable emerging concepts, such as identity, sense of place, quality of life and benefits of social networks, are gaining importance as opposed to traditional themes such as equity, poverty reduction and livelihood. In the past few years, the concept of social sustainability in urban settings has shifted toward being seen as depending on social networks, community contribution, stability and security, as well as a sense of place (Glasson & Wood Citation2009).

Based on a comprehensive literature review, the building blocks of the dimensions of social sustainability, which later provide the basis upon which the core social sustainability components are elaborated upon, have been tabulated in . From this, it is evident that while the literature highlights the relatively limited treatment to the social pillar, wide-ranging social objectives, strategies and measurement instruments have been developed, but with little regard to the physical reality and sustainability perspective (Metzner Citation2000) except for a few recent studies (e.g. Woodcraft Citation2011; Dempsey et al. Citation2011). This results in difficulties to present the available knowledge in a way suitable for integration into sustainable development design and policies. Social sustainability aspects are generally “added-on” to promote the message of other disciplines (i.e. economics, ecology) (McKenzie Citation2004) or, in some cases, dismissed altogether, not only because sustainable development originated out of the synergy between 1960s environmental movement and 1970s “basic needs”, but also because they are difficult to define more so to quantify (Burton Citation2000; Colantonio Citation2007). Dempsey et al. (Citation2011) argues that, social sustainability is neither an absolute nor a constant. It is a dynamic concept that will change over time in a place. All these ambiguities associated with the meanings and interpretations of the concept, despite the extensive body of literature therefore, suggest that a greater understanding of the social dimension of sustainable development is indispensable.

5. (Re)Constructing the community: the role of bottom-up approaches and neighbourhood scale

Social sustainability depends upon the spatial scales at which the built environment is studied and the relative strength of various forces operating at each scale. In recent years, neighbourhoods, as an important unit of social organisation and locus of action, have gained increasing attention as a setting for citizens’ experience of urban life. It is seen as an arena for social change, where local communities can effectively participate in meeting sustainability objectives through formulation of collective goals, action and communal support (Young Citation1990) on which larger decisions may be based. The increased research and place-based development policies on neighbourhoods and local communities can be ascribed to several reasons.

Rising concerns regarding change in the social fabric of cities such as decline in traditional social bonds, solidarity (Giddens Citation2009) and a gradual loss of cultural identities (Zetter & Watson Citation2012) under the influence of globalisation and rapid urbanisation.

The increasing concerns about the quality of life in rapidly transforming cities leading to a growing interest in the measurement of different aspects of neighbourhood social sustainability as they provide a useful scale for studying the social relations of ‘everyday life-worlds’ (Meegan & Mitchell 2001).

Overall reassertion that neighbourhoods or local arenas can influence both individual and collective well-being as well as achieve wider societal goals.

Increasing significance of sustainable “local community” as a means to deal with spatially manifested deprivation, inequity and social exclusion (Forrest & Kearns Citation2001), which threaten the social stability and economic competitiveness of cities.

Increasing interest in the processes of self-organisation and bottom up approaches and recognition that macro-level sustainability actions are influenced by micro-level efforts.

In India, the concept of neighbourhood is not as established and defined as in the western world context. Yet, there does exist the concept of communities defined within physical spaces and the notion of localities to which almost every resident of a city somehow apprehends a sense of neighbourhood and ascribes some meaning to it or draw intense emotions than any other space in the city. Indian urban neighbourhoods, where once traditional ties, close kinship links, shared religious and moral values represented a cohesive structure in a physically bound space, are gradually being replaced by anonymity, individualism and virtuality, questioning the importance of neighbourhood as a social and physical entity in our everyday lives. Social and spatial exclusion is also on the increase as the new high security luxury apartments and exclusive residential areas are being reshaped to create less public space and are sold as new neighbourhood type. The extent to which ideal tight-knit harmonious neighbourhoods ever existed is a matter of some debate, and although there are continuing trends associated with the decline of the conventional role and meaning of neighbourhood as a focal point of everyday lives or arenas for extended domestic activities, literature review suggests that there are several contemporary factors that reinforce as well as reshape the role of neighbourhoods as communally experienced geographical spaces (Arundel Citation2011).

Different elements of neighbourhoods may be important to people at different life stages, and their significance may be higher for some people than for others, most often for people with limited incomes, limited mobility, age groups and those who rely more on their local arena as a source of social networking and use services close to where they live. In the face of global capital, information flows and lifestyles, contradictory re-emphasis of neighbourhood can be made based on its importance in the social and psychological well-being of individuals (Bridger & Luloff Citation2001; Kearns & Parkinson Citation2001) as well as technology-led reintegration of work and home space for the future generation. This clearly points to the need to think in terms of “neighbourhood redefined” rather than “neighbourhood lost”. Sustainable development actions at this local scale can ultimately be the most effective means of showing the potential for long-term improvement on a larger scale, thus increasing the likelihood for the concept of sustainability to acquire the widespread legitimacy that has so far proved elusive. Donner and Neve (Citation2006) have argued that for long, research on urban issues in India has been left to policymakers, economists, geographers and urban planners, who quantitatively explore the processes of urbanisation and related issues of governance, infrastructure and livelihoods, along with social scientists, who are interested gaining insights into the changing patterns of inequity, segregation mobility and morality. Centrality of urban spaces in the lives of ordinary Indians and the role of neighbourhoods as socially constructed places across the subcontinent have, in general, been ignored.

6. Strengthening the 4 “S”

We have seen that regardless of its anthropocentric focus and general conformity that social sustainability is significant, there has been little investigation of what it exactly means in theory and more so, in practice. The ongoing problems of lack of confirmed definition of the construct, its relation to other variables, and how best to measure it continue to impede the application of social sustainability, as theory, research and practice are inevitably intertwined and shortfall in one area results in a deficit in another. Despite the apparent lack of consensus on the scope and meaning of social sustainability, different authors have brought forth several social components in order to operationalise the concept. And, even with the fact that the concept of social sustainability is complex, because it includes a multitude of contributory facets, one can identify at least four broadly accepted and overlapping social sustainability dimensions within which these components can be grouped. Building on the review of social sustainability literature so far, one can argue that social sustainability in built-environment is “a combined top-down and bottom-up process for creating spaces that nurture the 4 “S”, social capital, social cohesion, social inclusion and social equity, that appreciates the people’s diverse needs and desires from the places they use”. Although there is little information specifically on social sustainability, there exists broader literature on these four dimensions. Social capital and social cohesion relate more directly to the concept of social sustainability as a set of social conditions that “enable” reaching collective goals while social equity and social inclusion represent actual end-goals.

6.1. Social capital and social cohesion

The role of social capital and social cohesion in promoting sustainable development has received increased attention in both sustainable development theory and practice in recent years. Social capital is referred to as “features of social organisation such as networks, norms and trust that facilitate co-ordination/co-operation for mutual benefit” (Putnam Citation1993, p. 67). Viewed “not just as the sum of the institutions which underpin a society; but glue that holds them together” (The World Bank Citation1998, p. 1), it has at-least two dimensions, trust and cooperative ability (Paldam Citation2000). Social capital has also been defined as the ability of people to work together for common purposes in groups and organisations (Coleman Citation1988). It is, therefore, seen as a fundamental component of many social institutions such as the sets of rules, processes and norms that guide human behaviour and is a contributor to community strength and well-being, which can be accumulated when people interact with one another formally and informally. Advances in social capital research also imply that social capital is a multidimensional construct (Woolcock Citation1998; Paldam Citation2000), with bonding (associations among homogeneous group of people), bridging (associations among heterogeneous group of people) and linking (vertical associations) social capital being most commonly discussed in the literature. As a contested concept in itself, social capital, on one hand has been linked to increased community cohesion (Paldam Citation2000), better psychological health (Ziersch et al. Citation2005) and lower crime (Salmi & Kivivuori Citation2006), while on the other, it is also claimed to have negative outcomes such as exclusion and social isolation (Harper & Kelly Citation2003), especially in relation to very high bonding capital.

The overlapping concept of social cohesion has also become a key concept in social policy discourse and debates. It has been promoted by organisations such as United Nations (Citation1995), The World Bank (Citation1998) and has become central to EU Sustainable Development policy (in particular Eurostat Citation2005, 2007; ODPM Citation2005). There is no commonly accepted definition of social cohesion in international literature. It is variously described as the “affective bonds between citizens” (Chipkin & Ngqulunga Citation2008), “local patterns of cooperation” (Fearon et al. Citation2008), and “quantity and quality of interactions among people in a community” (Cochrun Citation1994). Recently, Chan et al. (Citation2006) defined social cohesion as

a state of affairs concerning both vertical and the horizontal interactions among members of society as characterized by a set of attitudes and norms that includes trust, sense of belongingness and the willingness to participate and help as well as their behavioural manifestations.

The term “social cohesion” is often used interchangeably with “social capital”, where the conflicting notions of interpersonal and inter-group social cohesion bear similarity to the notions of “bonding” and “bridging” social capital (King et al. Citation2010). Yet, it is central to the concept of social sustainability and is linked to the need to promote tolerance (Cuthill Citation2009), solidarity and integration (Jörissen et al. 1999 as cited in Murphy Citation2012), harmony and a sense of community (Colletta et al. Citation2001), to foster a shared sense of social purpose (Baker Citation2006) and civic and community participation (Omann & Spangenberg Citation2002), and to reduce conflicts (Munasinghe Citation2007) as well as promote stability, safety and place attachment (Dempsey et al. Citation2011).

Social capital and social cohesion, as dimensions of social sustainability, are vast concepts and subject to further research; this analytical study proceeds with the study of five components that are considered fundamental and sensitive to the design of built environment (). Studies on their significance and association with built environment further suggest that all the selected five components of social capital and social cohesion are interrelated in very complex and often mutually reinforcing ways ().

Table 2. Five key components of the overlapping concepts of social capital and social cohesion.

Although social capital and social cohesion, and many of their corresponding components, are contested concepts in terms of their importance in the achievement of wider social goals, there is consensus, in theory and policy, that both concepts are positive and desirable social goods (Forrest & Kearns Citation2001; Bramley & Power Citation2009). They knit communities together, laying down the negotiated basis of social life in which people support and work together, which in turn, provides the grounding for general economic productivity and growth, good governance, health and social security (Stanley Citation2003). They provide both direct and indirect benefits and has therefore, gained significant theoretical ground and are becoming central to public policymaking. Yet, there are no empirical studies that would relate the levels of social capital/cohesion and development in India, whose vast geographical area, huge ethnic and cultural diversity and immense economic and social inequality calls for the utmost need to consider social cohesion in policymaking (Mukherjee & Saraswati Citation2011). Nowhere are these questions about social capital and cohesion more compelling than in highly heterogeneous rapidly developing economies such as India, where the keys to development are often sought in the informal and institutional relationships necessary for modern social life.

6.2. Social equity and social inclusion

Social equity and inclusion are strongly associated with the notion of justice and imply enabling people to share in economic, environmental and social benefits, damages and costs as well as to participate in governance. They are described as “powerful political and policy concerns” (Jenks & Jones Citation2010, p. 108) as growing inequalities and exclusion are identified as major and structurally threatening costs to the governments, including social security, health, education, law and order and housing and environment outlays. An equitable society rejects any “exclusionary” or “discriminatory” practices that may hinder individuals from participating economically, socially and politically in society (Ratcliffe Citation2000; Pierson Citation2002). In the urban context, exclusion and inequalities are seen to have serious spatial consequences that get manifested into areas of deprivation and poverty, excluding certain segments of the society from access to resources and opportunities offered by the city (Chalmers & Colvin Citation2005) to both survive and fulfil their development potentials. Dempsey et al. (Citation2011) argues that within an urban context, social equity and inclusion are also critical at the local scale, where it relates to everyday experience of the built environment. This refers to a wide spectrum of policy areas ranging from “availability” to “accessibility” of basic services and facilities as well as opportunities for personal development and growth. In terms of measuring social equity, accessibility is commonly cited as a fundamental measure (Burton Citation2000). Movement barriers may occur in different forms, physical and mental leading to social injustices and socio-spatial inequities especially in relation to area, class, and people with special needs (Boschmann & Kwan Citation2008; Stjernborg Citation2014).

Indian cities and their urban forms today are one of the most visual expressions of these inequalities and deteriorating social conditions. While the country’s growing urban areas are showcased by the increasing power of the “middle class” and the emergence of a new urban political economy, the exclusion of certain segments of the people from enjoying the urban advantage to the fullest remains less in focus from a development imagination. The ever-widening urban gap in the era of world-class cities is symbolised by the stark disparity in the quality of the living environment, reflected in the contrasting forms creating a patchwork of distinct urban forms such as the formal “defensive city” (fear of crime and a desire for exclusiveness is leading to new wealth enclaves linked by motorways and with privatised public spaces, fortress-like hotels, malls and office complexes), the traditional “forgotten city” (these are dense, mixed-use urban quarters, perceived as lacking in modern amenities and infrastructure but, on the whole, socially thriving places) and the informal “slum city” (these are built without permission, lacking all services and infrastructure and characterised by extreme poverty, ill health and deprivation) (Hemani et al. Citation2012, p. 784).

Assessment of the urban space in many cities indicates that this urban spatial segregation is not just a physical expression of income inequalities among households but a social, cultural and economic divide that poses a danger to social stability and sustained economic (Beall & Fox Citation2007; UN-HABITAT Citation2008, Citation2010). Several international studies have claimed that the increasing number of defensive urban forms are not merely a response to growing concerns with security or even the desire for privacy, but represent more innate social conditions, such as the intensity of prevalent social inequality, patterns of segregation and exclusion, distribution of power and access to participation and, more importantly, the availability of choices and opportunities to “urban advantage” (Soja Citation2000; UN-HABITAT Citation2008, Citation2010; Bagaeen and Uduku Citation2010). Such an “urban divide” further threatens the social stability of the city thus, increasing insecurity, and fear among the citizens that shape the sprawling city through the growth of citadel communities in demand for “safe” neighbourhoods further reinforcing the divide leading to a so-called “spiral of decline” (Van Ham & Clark Citation2009), which is a combination of both physical and social problems that reinforce one another. Thus, growth itself can be destabilising if it is not inclusive.

The above-mentioned facts emphasise the need to design inclusive cities in order to ensure their sustainability by incorporating a long-term social dimension into urban policy. Although, exclusionary processes operate along and interact across different dimensions (economic, political, social, cultural and physical) and work at different levels, in the Indian urban context, social equity and inclusion may refer to “availability of” and “access to” the following three aspects within built environment:

Basic services: They are the “non-negotiable musts” that refer to the provision of basic infrastructure and services such as water, sanitation and decent shelter for all.

Basic facilities: They are the intra-neighbourhood facilities such as medical, banking, educational and open recreational facilities as well as “daily domestic-do” that must be readily available to all for everyday their sustenance and enhancement. Such facilities should be provided within a person’s immediate neighbourhood.

Basic amenities: They are the intra-neighbourhood amenities such as leisure shopping, clubs, sports facilities, community centre, places of worship and faith, cultural centres, library, restaurants should be easily accessible to all. Such amenities should be provided within the wider neighbourhood or city scales ().

7. Summary: a framework for social sustainability

Urbanisation, coupled with technological advancements and globalisation over the last century, has highlighted the economic potential along with the social and environmental cost of growth. And as more and more countries in the developing world enter into the high-growth and rapid-transition phase of the urbanisation process, their impact will bring major global and local change not only due to their huge population size with increasing levels of consumption, production and waste but also because they are particularly vulnerable to lack of resources and climate change in the foreseeable future. As a result, a majority of the developing world cities are advocating planning mechanisms and growth management approaches that emphasise on sustainable urban development.

However in India, environmental concerns have come to dominate the design and planning policies for cities despite the country’s consistent efforts towards dealing with the planet’s sustainability crisis. Investigations in the field have shown that of the three, the social dimension so far, has remained the weakest pillar and has received the least attention in sustainable development research, policy and practice. As a consequence, Indian cities face, coupled with deep spatial segregation, grave social issues such as acute poverty, crime, inequity and deteriorating quality of life, which are some of the fundamental challenges to sustainable development. Just as the country prepares for the influx of another 350 million people by developing a number of new greenfield cities, whilst improving the condition of it’s existing urban population, there is clearly a pressing need to develop a stronger conceptual understanding of the social pillar of sustainable development that cannot be ignored or dismissed. Since the effects of “social” climate change are becoming more obvious today, any discourse on “smart” city planning and urban design that does not address the entire complexity of social sustainability issues in an integrated manner, combined with environmental and ecological concerns, has little meaning at a time when India’s urban areas are rapidly growing and altering in complex and unsustainable ways.

Through a detailed review of literature, this paper therefore provided theoretical insights into the indispensable concept of social sustainability, which may be easy to sympathise with but difficult to comprehend. This research enabled us to come very close to the understanding of the concept and its constituent dimensions – the 4 S, social capital, social cohesion, social equity and social inclusion. However, the next level of the understanding concerning the social sustainability outputs – “what a socially sustainable neighbourhood looks like” was found to be non-existent in both, the social and sustainable urban development theories. To this void, the concept suffers in practice, where it acts as a meaningless label attached to sustainable development which is not substantiated by ground research. The question: “how social sustainability can be incorporated into the planning of Indian cities?” remains unanswered despite several efforts towards understanding the concept and developing theoretical frameworks to operationalise it, in addition to recent attempts of empirically investigating it in relation to sustainable cities.

This is because the intangible and context-dependent nature makes it difficult to define, measure and thus design social sustainability. Even when a definition is agreed, this is seen to be framed within self-fulfilling outputs without clear understanding of what types of urban environments nurture or deter social sustainability. As a result, Indian urban development and planning policies are likely to threaten and replace established communities with new developments claimed as smart and sustainable. This perhaps leads to the argument that in the absence of a clear and agreed theory and evidence-based planning policies, a social sustainability framework may be a necessary intervention, for rapidly urbanising Indian cities, which can act as a trellisFootnote2 upon which the concept grows and allows sustainable communities to emerge.

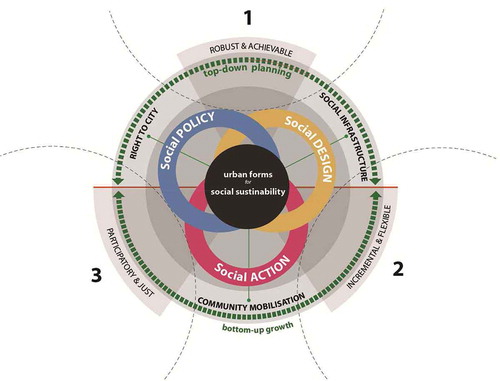

An integrated social sustainability framework for urban built-environment focusing on social policy, design and action () suggests that a combination of both (micro-level variables) bottom-up and (macro-level variables) top-down approaches may be necessary because social sustainability in cities is likely to benefit from both, planned context and emergent actions. Such a framework enables different levels to interact regularly, depending on the extent of conflict and the strength of implementation of strategies in a particular context.

Figure 4. Social sustainability framework for policy, design and action in spatial design of cities.

The framework systematically defines and translates the characteristics of social sustainability into sets of:

Robust and achievable social policies (top-down) ()

The social policies intend potential change for challenges related to the social dimension of sustainability through top-down regulatory frameworks. Although criticised for its statutory approach as an initiation for social change, such an approach involves immense strength to plan large-scale development programmes and develop generalisable policy advice as well as monitor consistent behaviour patterns across those policies. However, imposed top-down policies without consultation of various stakeholders can result in conflict and question its long-term effects. This framework therefore proposes development of participatory social planning policies which are robust and achievable. It focuses on four aspects: right to shelter, access, space and decision.

Incremental and flexible “social design” principles (linking top-down and bottom-up) ()

The combination of bottom-up and top-down approaches constitutes a long-standing challenge in the sustainable development application; however, a mixed complimentary framework such as this provides a unifying framework for combining the broader planning policies with more specific and contextual local actions. Synergies are created between the two using social design principles. It is significant that design principles are incremental and flexible so that they can adapt to local difficulties and contextual factors.

Inclusive and empowering social actions (bottom-up) ()

Local actors and their needs, desires and actions should be understood for effective implementation and long-term success of the social sustainability framework. Bottom-up social actions do not present prescriptive advice, but rather describe what factors have caused difficulty in reaching social goals. Local-level resources such as neighbourhood parliaments, institutions, forums and websites play a key role in community mobilisation, empowerment and participation. Bottom-up social actions not only increase efficiency of the framework but also enable communities to transform their choices into desired actions and outcomes. It is important that the social actions are inclusive and are led by elected representatives.

A framework such as this may not be taken as a blueprint for social sustainability in all cities; rather it may act as a trellis upon which the social change is enabled, one which secures flexibility, adaptability and liveability of a constantly evolving society. It is not a rigid set of rules, but principles that aim to humanise the current urban development in India.

Table 3. Robust and achievable social policies (top-down).

Table 4. Incremental and flexible social design principles (linking top-down and bottom-up).

Table 5. Inclusive and empowering social actions (bottom-up).

8. Limitations and future scope of work

This paper is solely based on secondary data sources. For all of the research mentioned, the answer to the question of how social sustainability can be incorporated into the planning of Indian cities has not emerged through academic work. There is therefore a great scope to further harness and empirically investigate the identified components of social sustainability – social capital, social cohesion, social equity and social inclusion – in the country’s urban development model and sustainability goals in order to deal with the issues of humanising urban development in India.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shruti Hemani

Shruti is an architect/urban designer currently pursuing PhD at the Department of Design, Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, India. Her undergraduate design thesis was awarded the best thesis Gold Medal by The M.S. University of Baroda, India. She also won the “Developing Solutions Scholarship” at the University of Nottingham, UK, where her M.Arch Design Project was awarded the students’ joint first prize for the RIBA’s INREB International Design Ideas Competition. In 2010, she was awarded commendation for the National Design and Planning Competition Surat Safe Habitat – Theme 2 as part of Rockefeller Foundation’s ACCCRN Program. As an Associate Project Engineer, she has worked on developing design education modules under the project entitled “Creating Digital Learning Environment for Design in India, E-Kalpa” sponsored by the Ministry of Human Resources, Government of India. Since 2012, her research work has been published and presented at a number of national and international conferences. With more than eight years of experience, the main focus of her work has been planning, design and research in the area of sustainable cities as well as running community consultation and design training programmes.

Amarendra Kumar Das

Dr Das is Professor and Ex-head at the Department of Design, IIT, Guwahati. He is actively involved in Design Research and Product Design and Development activities. Dr Das has been responsible for a number of projects and consultancies for private, public and defence organisations. He has been a consultant to KVIC for policy decision and infrastructure development for the north eastern region and has prepared DPR for Khadihaat for Guwahati. Dr Das has published a number of papers in National and International forums in diverse areas. He has received the National Award of Excellence for Designing Dipbahan tricycle rickshaw, an award instituted by the Institute of Urban Transport, Delhi, and Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. His current activities involve Design and Technology Transfer for contextual socially relevant design, Concept to Market – Innovative products for socially relevant products, Appropriate Technology including crafts, cane and bamboo and textiles, Transportation Design, Rapid Prototyping and Tooling, Support to small and medium industries including grass root innovators through GIAN-NE, NIF. He is presently a member of Expert Committee for DST, CSIR, Central Silk Board, and is a consultant for non-conventional and renewable sources of power for selected African countries.

Notes

1. There is no simple definition for smart cities. The term encompasses a vision of an urban space that is ecologically friendly, technologically integrated and meticulously planned, with a particular reliance on the use of information technology to improve efficiency. The Smart Cities Council, an industry-backed set-up that advocates the concept in India, describes them as cities that leverage data gathered from smart sensors through a smart grid to create a city that is liveable, workable and sustainable.

2. The word trellis was coined in the book, the Sustainable Urban Neighbourhood (Rudlin & Falk 2009, p. 268), which described a master plan as “a trellis on which the vine of the city can grow”.

References

- Arundel R. 2011. Neighbourhood urban form and social sustainability [unpublished thesis]. Amsterdam: Urban and Regional Planning, University of Amsterdam.

- Bagaeen S, Uduku O. editors. 2010. Gated communities: social sustainability in contemporary and historical gated developments. London: Earthscan.

- Baines J, Morgan B. 2004. Sustainability appraisal: a social perspective. In: Dalal- Clayton B, Sadler B, editors. Sustainability appraisal: a review of international experience and practice. London: International Institute for Environment and Development. First Draft of Work in Progress.

- Baker S. 2006. Sustainable development. New York: Routledge.

- Barbier EB. 1987. The concept of sustainable economic development. Environ Conserv. 14:101–110.

- Barron L, Gauntlett E. 2002. Stage 1 report – model of social sustainability. Housing and sustainable communities’ indicators project. Perth: Murdoch University, Western Australia.

- Beall J, Fox S. 2007. Urban poverty and development in the 21st century: towards an inclusive and sustainable world. Oxfam GB Research Report.

- Blowers A, Pain K. 1999. The unsustainable city?. In: Brook C, Mooney G, Pile S, editors. Unruly cities? Order/disorder (understanding cities). London: Routledge; p. 222–267.

- Boschmann E, Kwan M-P. 2008. Toward socially sustainable urban transportation: progress and potentials. Int J Sust Transport. 2:138–157.

- Bramley G, Power S. 2009. Urban form and social sustainability: the role of density and housing type. Environ Plann B: Plann Des. 36:30–48.

- Bramley G, Brown C, Dempsey N, Power S, Watkins D. 2010. Chapter 5, Social acceptability. In: Jenks M, Jones C, editors. Dimensions of the sustainable city. London: Springer; p. 105–128.

- Bramley G, Power S, Dempsey N. 2006. What is ‘social sustainability’, and how do our existing urban forms perform in nurturing it? In: Global places, local spaces, planning research conference; 5–7 Apr. London: The Bartlett School of Planning, University College London.

- Bridger JC, Luloff AE. 2001. Building the sustainable community: is social capital the answer?. Sociol Inq. 71:458–472.

- Bromley RDF, Tallon AR, Thomas CJ. 2005. City centre regeneration through residential development: contributing to sustainability. Urban Stud. 42:2407–2429.

- Burton E. 2000. The compact city: just or just compact? A preliminary analysis. Urban Stud. 37:1969–2006.

- Carlson R. 1962. Silent spring. In: Ravitch D, editor. The American reader: words that moved a nation [Internet]. New York: Harper Collins, 1990; pp. 323–325. [cited 2013 Nov 20]. Available from http://www.uky.edu/Classes/NRC/381/carson_spring.pdf

- Chalmers H, Colvin J. 2005. Addressing environmental inequalities in UK policy: an action research perspective. Local Environ. 10:333–360.

- Chambers R, Conway G. 1992. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. IDS Discussion Paper 296. Brighton: IDS.

- Chan E, Lee GKL. 2008. Critical factors for improving social sustainability of urban renewal projects. Soc Ind Res. 85:243–256.

- Chan J, To H, Chan E. 2006. Reconsidering social cohesion: developing a definition and analytical framework for empirical research. Soc Indic Res. 75:273–302.

- Chipkin I, Ngqulunga B. 2008. Friends and family: social cohesion in South Africa. J South Afr Stud. 34:61–76.

- Chiu R. 2003. Social sustainability, sustainable development and housing development: the experience of Hong Kong. In: Forrest R, Lee J, editors. Housing and social change: east-west perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Cochrun S. 1994. Understanding and enhancing neighborhood sense of community. J Plann Lit. 9:92–99.

- Colantonio A. 2007. Social sustainability: an exploratory analysis of its definition, assessment methods, metrics and tools: best practice from urban renewal in the EU. Oxford: Oxford Brooks University.

- Colantonio A. 2008a. Social sustainability: linking research to policy and practice. Headington: Oxford Brookes University .

- Colantonio A. 2008b. Traditional and emerging prospects in social sustainability. Measuring social sustainability: best practice from urban renewal in the EU. Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development (OISD). Headington: Oxford Brookes University.

- Colantonio A, Dixon T. 2009. Measuring socially sustainable urban regeneration in Europe. EIB Final Report. Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development (OISD). Oxford: Oxford Brookes University.

- Coleman J. 1988. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 94:95–120.

- Colletta NJ, Lim TG, Kelles-Viitanen A, editor. 2001. Social cohesion and conflict prevention in Asia: managing diversity through development. Washington (DC): The World Bank.

- Cuthill M. 2009. Strengthening the “social” in sustainable development: developing a conceptual framework for social sustainability in a rapid urban growth region in Australia. Sustain Dev. 18:362–373.

- Davidson K, Wilson L. 2009. A critical assessment of urban social sustainability. Adelaide: The University of South Australia.

- Dempsey N, Bramley G, Powers S, Brown C. 2011. The social dimension of sustainable development: defining urban social sustainability. Sustain Dev. 19:289–300.

- [DFID] Department for International Development. 1999. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. London: DFID.

- Dixon T, Colantonio A. 2008. Submission to EIB consultation on the draft EIB statement of environmental and social principles and standards. Oxford: Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development.

- Donner H, Neve G. 2006. Space, place and globalisation: revisiting the urban neighbourhood in India. In: Donner H, Geert De N, editors. The meaning of the local: politics of place in urban India. London (UK): Taylor & Francis; p. 1–21.

- Empacher C, Wehling P. 1999. Indikatoren sozialer Nachhaltigkeit, ISOE Diskussionspapiere 13. In: Omannn I, Spangenberg JH, editors. Assessing social sustainability. The social dimension of sustainability in a socio-economic scenario, paper presented at the 7th biennial conference of the international society for ecological economics; 2002 Mar 6–9; Sousse.

- Eurostat. 2005. Measuring progress towards a more sustainable Europe: sustainable development indicators in the European union. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Eurostat. 2007. Measuring progress towards a more sustainable Europe: 2007 monitoring report of the EU sustainable development strategy. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Fearon JD, Humphreys M, Weinstein J. 2008. The behavioral impacts of community-driven reconstruction: evidence from an IRC community-driven reconstruction project in Liberia. In: Samii C, editor. Interventions to promote social cohesion in sub-saharan Africa, 3ie Synthetic Reviews No. 2 Protocol [unpublished thesis]. Department of Political Science Columbia University, New York (NY). Available from http://www.3ieimpact.org/media/filer_public/2012/05/07/18.pdf

- Feitosa FF, Camara G, Monteiro A, Koschitzki T, Silva M. 2007. Global and local indicators of urban segregation. Int J Geogr Inf Sci. 21:299–323.

- Forrest R, Kearns A. 2001. Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 38:2125–2143.

- Fukuyama F. 1995. Trust: the social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York (NY): Free Press.

- Giddens A. 2009. Sociology. 6th ed. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Glasson J, Wood G. 2009. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess Project Appr. 27:283–290.

- Greider W. 1997. One world, ready or not: the manic logic of global capitalism. New York (NY): Simon and Schuster.

- Hans-Boeckler-Foundation, editor. 2001. Pathways towards a sustainable future. Düsseldorf: Setzkasten.

- Harper R, Kelly M. 2003. Measuring social capital in the United Kingdom. London: Office for National Statistics.

- Haughton G. 1999. Environmental justice and the sustainable city. In: Satterthwaite D, editors. Sustainable cities. London: Earthscan.

- Hemani S, Das AK, Rudlin D. 2012. Influence of urban forms on social sustainability in case of Indian cities. In: Pacetti. M, editors. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Urban Regeneration and Sustainability, Vol. 2. Ancona: WIT Press; pp. 783–797.

- Human Development Report. 2013. The rise of the south: human progress in a diverse world [Internet]. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), NY. [cited 2013 Dec 20]. Available from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/14/hdr2013_en_complete.pdf

- [IUCN] International Union for Conservation of Nature. 1980. World conservation strategy: living resource conservation for sustainable development. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

- Jenks M, Jones C. 2010. Dimensions of the sustainable city. London: Springer.

- Kearns A, Parkinson M. 2001. The significance of neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 38:2103–2110.

- King E, Samii C, Snilstveit B. 2010. Interventions to promote social cohesion in sub-Saharan Africa. J Dev Effect. 2:336–370.

- Koning J, 2001. Social sustainability in a globalizing world. Context, theory and methodology explored. Paper prepared for the UNESCO/MOST meeting; 2001 Nov 22–23; The Hague.

- LEED India. 2011. Indian Green Building Council rating systems [Internet]. [cited 2013 Nov 20]. Available from https://igbc.in/igbc/redirectHtml.htm?redVal=showLeednosign

- Littig B. 2001. Zur sozialen Dimension nachhaltiger Entwicklung, Strategy Group Sustainability. In: Omannn I, Spangenberg JH, editor, Assessing social sustainability. The social dimension of sustainability in a socio-economic scenario, paper presented at the 7th biennial conference of the international society for ecological economics; 2002 Mar 6–9; Sousse.

- Littig B, Grießler E. 2005. Social sustainability: a catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int J Sust Dev. 8:65.

- McKenzie S. 2004. Social sustainability: towards some definitions. Working Paper Series No 27. Magill: Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia.

- Meegan R, Mitchell A. 2001. “It’s not community round here, it’s neighbourhood”: neighbourhood change and cohesion in urban regeneration policies. Urban Stud. 38:2167–2194.

- Metzner A. 2000. Caring capacity and carrying capacity – a social science perspective. Paper presented at the INES 2000 Conference: Challenges for Science and Engineering in the 21st Century. Stockholm

- Mukherjee P, Saraswati LR (2011) Levels and patterns of social cohesion and its relationship with development in India: a woman’s perspective approach. International Conference on Social Cohesion and Development, OECD, Paris. [cited 2014 Oct 20]. Available from http://www.oecd.org/dev/pgd/46839502.pdf.

- Munasinghe M. 2007. Sustainable development triangle [Internet]. [cited 2012 Dec 6]. Available from http://www.eoearth.org/article/Sustainable_development_triangle

- Murphy K. 2012. The social pillar of sustainable development: aliterature review and framework for policy analysis. Sust: Sci, Pract Pol. 8:15–29.

- NMSH, Ministry of Urban Development Report. 2010. National mission on sustainable habitat [Internet]. Government of India [cited 2012 Oct 18]. Available from http://www.ielrc.org/content/e1018.pdf.

- [ODPM] Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. 2003. Sustainable communities: building for the future. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

- ODPM. 2005. Bristol accord: conclusions of ministerial informal on sustainable communities in Europe UK presidency [Internet]. London: ODPM. Available from http://www.eib.org/attachments/jessica_bristol_accord_sustainable_communities.pdf

- ODPM. 2006. UK presidency EU ministerial informal on sustainable communities: policy papers [Internet]. [cited 2011 Oct 16]. Available from http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/regeneration/pdf/143108.pdf

- Omann I, Spangenberg J. 2002. Assessing social sustainability: the social dimension of sustainability in a socio-economic scenario [Internet]. Presented at the 7th Biennial conference of the international society for ecological economics, Sousse. [cited 2012 Nov 24]. Available from http://seri.at/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Assessing_social_sustainability.pdf

- Paldam M. 2000. Social capital: one or many? Definition and measurement. J Econ Surv. 14:629–653.

- Pierson J. 2002. Tackling social exclusion. London: Routledge.

- Polese M, Stren R. 2000. The social sustainability of cities: diversity and management of change. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Putnam RD. 1993. Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

- Ratcliffe P. 2000. Is the assertion of minority identity compatible with the idea of a socially inclusive society?. In: Askonas P, Stewart A, eds. Social inclusion: possibilities and tensions. Basingstoke: Macmillan; p. 169–185.

- Rudlin D, Falk N. 2009. The sustainable urban neighbourhood: building the 21st century home. London: Routledge.

- Sachs I. 1999. Social sustainability and whole development: exploring the dimensions of sustainable development. In: Egon B, Thomas J, editors. Sustainability and the social sciences: a cross-disciplinary approach to integrating environmental considerations into theoretical reorientation. London: Zed Books.

- Salmi V, Kivivuori J. 2006. The association between social capital and juvenile crime. Eur J Criminol. 3:123–148.

- Saul J. 1997. The unconscious civilization. Ringwood (Australia): Penguin.

- Schumacher EF. 1973. Small is beautiful: economics as if people mattered. New York: Harper & Row.

- Sinner J, Baines J, Crengle H, Salmon G, Fenemor A, Tipa G, editors. 2004. Sustainable development: a summary of key concepts. Ecologic Research Report No. 2. Nelson: Ecologic Foundation.

- Soja E. 2000. Postmetropolis. In: Critical studies of cities and regions. Cornwall: Blackwell.

- Stanley D. 2003. What do we know about social cohesion: the research perspective of the federal government’s social cohesion research network. Can J Sociol. 28:1.

- Stjernborg V. 2014. Outdoor mobility, Place and Older People: Everyday Mobilities in Later Life in a Swedish Neighbourhood. Unpublished PhD thesis, Media-Tryck, Lund University.

- Thin N. 2002. Social progress and sustainable development. London: ITDG Publishing.

- Torjman S. 2000 Social dimension of sustainable development. In: Paper Prepared for the Commissioner of Environment and Sustainable Development at the Office of Auditor General. Caledon Institute of Social Policy, p. 1–11.

- Tuan YF. 1974. Topophilia. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice-Hall.

- [UNEP] United Nations Environment Programme. 1972. Report of the United Nations conference on the Human Environment. Jun 5–16, Stockholm; United Nations Environment Programme.

- UNFPA. 2007. State of world population: unleashing the potential of urban growth [Internet]. [cited 2013 Dec 21]. Available from http://www.unfpa.org/swp/2007/presskit/pdf/sowp2007_eng.pdf.

- UN-HABITAT. 2008. State of the world’s cities: bridging the urban divide 2010/2011. Earthscan Available from http://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/listItemDetails.aspx?publicationID=2917

- UN-HABITAT. 2010. Planning Sustainable Cities, UN-HABITAT Practices and Perspectives. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT.

- United Nations. 1995. Report of the world summit for social development [Internet]. Copenhagen. Sales No. E. 96.IV.8. [cited 1995 Mar 6–12]. Available from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/wssd/index.html

- Van Ham M, Clark WAV. 2009. Neighbourhood mobility in context: household moves and changing neighbourhoods in the Netherlands. Environ Plann. 41:1442–1459.

- Vavik T, Keitsch M. 2010. Exploring relationships between universal design and social sustainable development: some methodological aspects to the debate on the sciences of sustainability. Sust Dev. 18:295–305.

- WCED. 1987. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: our common future (Brundtland Report). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weingaertner C, Moberg Å. 2014. Exploring social sustainability: learning from perspectives on urban development and companies and products. Sust Dev. 22:122–133.

- The World Bank. 1998. Social Capital Initiative (SCI): the initiative on defining, monitoring and measuring social capital [Internet]. Overview and programme description. Social capital initiative working paper, No. 1. Washington (DC). [cited 2011 Jul 8]. Available from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTSOCIALCAPITAL/Resources/Social-Capital-Initiative-Working-Paper-Series/SCI-WPS-01.pdf

- Woodcraft S. 2011. Design for social sustainability: a framework for creating thriving new communities, homes and communities agency [Internet]. Young Found. 1 [cited 2013 Nov 3]. Available from http://www.social-life.co/media/files/DESIGN_FOR_SOCIAL_SUSTAINABILITY_3.pdf

- Woolcock M. 1998. Social capital and economic development: toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory Soc. 27:151–208.

- Yiftachel O, Hedgcock D. 1993. Urban social sustainability: the planning of an Australian city. Cities. 10:139–157.

- Young I. 1990. Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton (NJ): The Princeton University Press.

- Zetter R, Watson GB. 2012. Designing sustainable cities in the developing world. London: Ashgate Publishing.

- Ziersch AM, Baum FE, MacDougall C, Putland C. 2005. Neighbourhood life and social capital: the implications for health. Soc Sci Med. 60:71–86.

Appendix 1. List of key sustainable development “urban” and “social” policies reviewed for this research

Appendix 2. Building blocks for dimensions of social sustainability