Abstract

Little research examined how technical capacity contributes to smart growth applications. Therefore, this research paper applies case study analysis to investigate the effects of the technical capacity of city/town planning agencies on applications of smart growth policies to reduce urban sprawl. The case studies include 10 cities/towns located in different counties within the State of Maryland, USA. They represent four pairs/groups with comparable population size but different smart growth profiles.

First, the researcher conducted content analysis of city/town comprehensive plans to assess how they have embraced smart growth policies. Then, she interviewed city/town planners to explore factors contributing to policy applications. The analysis indicates that city/town technical planning capacity (PC) is the most important factor contributing to smart growth applications. It shows that county applications of anti-sprawl policies lead cities/towns to adopt smart growth policies to manage future growth. In addition, public preferences and concerns about rapid urban growth shape city/town land-use policies.

1. Introduction

Urban sprawl has been a major challenge facing planners and policymakers in the United States. It increases infrastructure costs, gas consumption, air pollution, traffic congestion, farmland loss, and environmental degradation. It has led to social segregation and the decline of central cities as a result of middle- and upper-class flights to suburbs (Carruthers Citation2002). To curb sprawl, several American states have adopted smart growth programmes that use governmental funds as incentives to direct development into designated areas, and to preserve environmentally sensitive lands (Hirt Citation2007). This incentive-based approach that rewards, but does not enforce, local compliance with state policies makes smart growth applications rely mainly on local government decisions to manage urban growth (Downs Citation2005).

Previous studies, mostly quantitative, provided mixed results of local factors contributing to smart growth applications. Moreover, little research examined the effects of technical capacity on local land-use planning. Brody et al. (Citation2006) point to needs for case study analysis of jurisdictions to demonstrate causes of local adoption of anti-sprawl land-use policies, while Edwards and Haines (Citation2007) call for research exploring the extent of integrating smart growth policies into local comprehensive plans. Therefore, this research paper applies case study analysis to investigate the impacts of technical capacity on city/town decisions to adopt smart growth policies.

The paper examines smart growth applications in 10 cities/towns located in the State of Maryland (USA), which has adopted a statewide smart growth programme since the mid-1990s. It explores effects of city/town technical planning capacity (PC) on applications of smart growth policies to reduce urban sprawl. Also, the paper investigates other local factors contributing to policy applications. The analysis depends on three sources of evidence: content analysis of city/town comprehensive plans, structured interviews with city/town planners, and secondary data. First, the paper reviews the literature on factors contributing to smart growth applications; then it explains the research methodology, Maryland’s smart growth programme, findings of the case study analysis, and research conclusions and policy implications.

2. Research on factors associated with smart growth applications

The American Planning Association (Citation2012) defines smart growth as the development that “supports choice and opportunity by promoting efficient and sustainable land development, incorporates redevelopment patterns that optimise prior infrastructure investments, and consumes less land that is otherwise available for agriculture, open space, natural systems, and rural lifestyles.” Downs (Citation2005) identifies six principles of smart growth: adopting growth controls, encouraging compact development and high residential densities, creating mixed land uses and pedestrian-friendly design, issuing impact fees to make new development pay for infrastructure costs, promoting public transit and multi-modal transportation, and revitalising old neighbourhoods. Smart growth policies to reduce urban sprawl can be divided into two major groups: (1) land preservation policies/programmes such as transfer of development rights (TDR), conservation easements, urban growth boundaries (UGBs), and greenbelts; and (2) inner city management policies including compact development, transit-oriented development, and planned unit development (PUD) among others (Brody et al. Citation2006; O’Connell Citation2009).

Several American states led by Maryland have adopted statewide smart growth programmes that usually consist of a package of incentives and mandates to guide local land-use planning. State incentives include, but are not limited to, tax credits and funds covering costs of infrastructure and public facilities in areas designated for future growth; in contrast, mandates focus on local comprehensive planning and measures to protect environmentally sensitive areas. Berke and French (Citation1994) found positive impacts of state mandates on the quality of local plans, while Dalton and Burby (Citation1994) indicated that municipalities subject to state mandates would use effective measures to implement their comprehensive plans. Burby et al. (Citation1997) and Carruthers (Citation2002) observed associations between state mandates of local comprehensive planning and applications of growth management policies. Yin and Sun (Citation2007) pointed to effects of state growth management programmes on promoting compact development in terms of high residential density and mixed land uses. Also, Hawkins (Citation2011) showed that local government dependency on state resources would affect smart growth applications.

Previous research provided mixed results of local factors contributing to smart growth applications. Baldassare and Wilson (Citation1996) found no correlation between population growth and adoption of land-use controls; however, Wassmer and Lascher (Citation2006) and Boarnet et al. (Citation2011) showed evidence supporting that correlation. Nguyen (Citation2009) emphasised that resident concerns about rapid urban growth and its unintended consequences would lead cities to apply smart growth policies to reduce sprawl. Educated residents tend to support smart growth policies, as Chapin and Connerly (Citation2004) suggested. Schneider and Kim (Citation1996) and Brody et al. (Citation2006) argued that communities with high incomes would support growth management policies, while O’Connell (Citation2009) showed negative associations between incomes and establishing land preservation programmes in large American cities.

In addition, Wassmer (Citation2001) indicates that local governments apply “imbalanced” land-use policies that favour commercial development to generate high tax revenues. Nguyen (Citation2009) explains how communities apply smart growth policies as a “strategic interaction” to growth spillover resulting from the adoption of growth controls by neighbouring jurisdictions.

Few studies investigated the effects of the technical capacity of local planning departments on adopted land-use policies. Brody et al. (Citation2006) found positive correlations between applications of anti-sprawl land-use policies and community technical PC in south Florida, and Ali (Citation2007) argues that the technical capacity of local planning agencies enables planners to involve the public in decision-making processes and to reorient planning policies towards growth management. This research re-examines the effects of technical capacity on local land-use policies to manage future growth.

3. Research methodology

This research paper applies case study analysis to address two major questions: does city/town technical PC contribute to applications of smart growth policies to reduce urban sprawl? and what are the other factors affecting policy applications? The research unit of analysis is a city/town that has 5000 or more inhabitants, is located in the State of Maryland (USA), and has authority for land-use planning.

The researcher conducted content analysis of the cities/towns’ most recent comprehensive plans to assess how they embrace smart growth policies. An evaluation protocol was developed to examine five categories of smart growth policies seeking to reduce urban sprawl: land-use policies to increase urban density, redevelopment and revitalisation policies, growth controls, infrastructure provisions, and land-conservation policies/programmes (see Downs Citation2005; Brody et al. Citation2006; O’Connell Citation2009; Litman Citation2012 among others). The researcher used a scheme proposed by Norton (Citation2008) to score levels of smart growth policy applications. A policy is scored 0 if it is not mentioned in the city/town comprehensive plan, 1 if it is proposed or encouraged, or 2 if it will be implemented. The maximum smart growth score a city/town could earn is 42. The preliminary analysis shows that city/town scores of smart growth applications range from 5 to 25 with an average of 17. Therefore, the adopted scale of smart growth applications is: low = less than 17 and high = 17 or more. The researcher was the sole coder of the content analysis.

The city/town technical PC is measured by an index expressing planner–population ratio and levels of planner education and years of professional experienceFootnote1 (the PC index is expressed as: low = less than 8 and high = 8 or more). Based on the literature review, four hypotheses were examined to address the research questions:

The technical capacity of city/town planning departments/divisions enables them to apply smart growth policies to reduce urban sprawl.

County adoption of growth management policies leads cities/towns to apply smart growth policies to combat sprawl. In other words, county land-use policies influence city/town land-use planning.

Public concerns about rapid urban growth and its unintended consequences motivate cities/towns to manage future development. Thus, cities/towns adopt land-use policies that meet residents’ development preferences.Footnote2

Applications of growth controls by neighbouring jurisdictions lead cities/towns to implement smart growth policies that address development pressures resulting from potential growth spillover.

The researcher conducted structured phone interviews with the cities/towns’ planners to examine the research hypotheses. The interviews had closed and open-ended questions. For confidentiality purposes, this paper does not indicate information about the interviewees. The researcher used secondary data obtained from the US Census Bureau, Maryland Department of Planning, and the cities/towns to support the case study analysis.

3.1. Selecting the case studies

The preliminary analysis identifies 33 cities/towns (excluding Baltimore City with over 600,000 people) that meet the criteria of the research unit of analysis: 16 cities/towns with 5000 to less than 10,000 people, eight cities/towns with 10,000 to less than 20,000 people, five cities/towns with 20,000 to less than 30,000, and four cities with 30,000 or more people. Out of the identified 33 cities/towns, the researcher selected 10 case study cities/towns that: (1) represent pairs/groups with comparable population size, which ensures similarities of municipal needs and problems, (2) vary in levels of smart growth applications, which enables examinations of factors contributing to policy variations, and (3) are located in different counties, which allows investigations of the effects of land-use policies adopted by counties and neighbouring jurisdictions (see showing the selected case studies).

As shown by , Frederick City is the most populace case study (65,239 people), while Walkersville is the least (5800 inhabitants) as of 2010. Interestingly, Salisbury has the highest percentage of labour working in place of residence (60%) but has relatively low median household incomes ($38,423), while Walkersville has the lowest proportion of workers inside the place of residence but the highest median household incomes ($82,891). In terms of land consumption and percentage of multi-unit housing structures, Laurel and Gaithersburg are the least sprawling while Walkersville is the most.

Table 1. Characteristics of the case studies.

The case study cities/towns represent four pairs/groups:

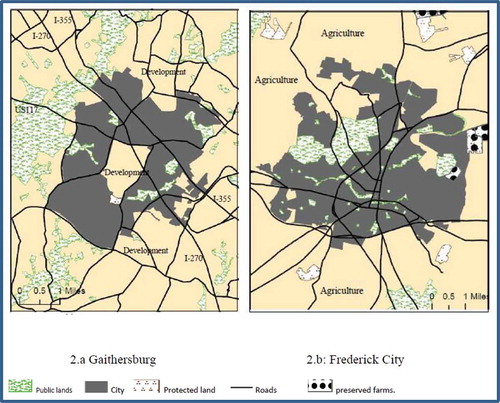

Gaithersburg and Frederick City (>30,000 people) are both located in the Region of Washington, DC, the US capital. Gaithersburg’s county (Montgomery) has applied smart growth policies to direct growth into existing communities, while Frederick City’s county (Frederick) has not adopted such policies.

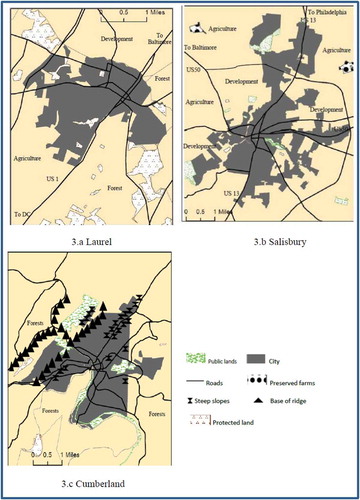

Laurel, Salisbury, and Cumberland (20,000 to <30,000 inhabitants) have different population growth patterns: Laurel and Salisbury are growing, but Cumberland is declining. Planning in Cumberland and Laurel is performed by city/town planning departments, while Salisbury’s planning is conducted by the county planning department through a city–county agreement.

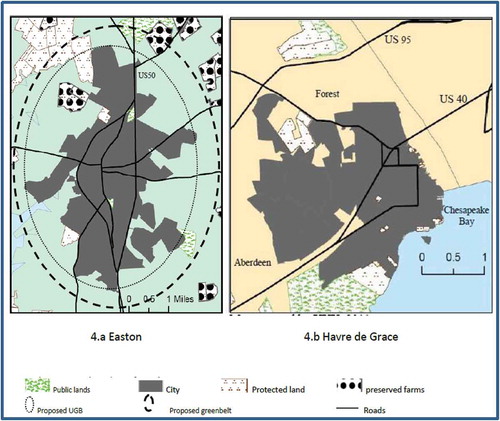

Easton and Havre de Grace (10,000 to <20,000 residents) are located in counties having different land-use policies. Easton is located in Talbot County that has adopted policies to discourage development outside incorporated areas, while Havre de Grace is located in Harford County that has not initiated growth management policies.

Taneytown, Brunswick, and Walkersville (5000 to <10,000 people) are small bedroom communities. Taneytown’s county (Carroll) attempts to contain urban growth within existing communities, while Walkersville and Brunswick’s county (Frederick) has not adopted growth controls.

4. Maryland’s smart growth

The State of Maryland has made serious efforts to reduce urban sprawl that led to converting thousands of acres of farmlands and forests into suburban development. It requires local governments to prepare comprehensive plans that guide future development decisions. Also, the State mandates plan elements such as land uses, transportation, sensitive areas, water resources, and municipal growth patterns among others. Local comprehensive plans should be reviewed and updated every six years.

In 1992 the State passed the Economic Growth, Resource Protection, and Planning Act that introduced eight planning visions, which were replaced with 12 new visions in 2009. The new State visions seek to concentrate growth in designated areas, promote compact development and mixed-use and walkable neighbourhood design, ensure the availability of infrastructure to serve new development, enhance multimodal and affordable transportation, offer a variety of housing types and densities, protect water resources including the Chesapeake and coastal bays, and conserve forests, farmlands, open space, natural systems, and scenic areas. The State visions should be addressed in local comprehensive plans, zoning ordinances, and land-use regulations (Maryland Annotated Code Article 66 B, S 1.01).

In 1997 Maryland adopted the Smart Growth and Neighborhood Conservation-Smart Growth Areas Act that aimed to contain urban growth inside Priority Funding Areas (PFAs).Footnote3 The State requires the residential density of new development within the PFAs to be 3.5 or more housing units per acre. Incentives in terms of State funds covering infrastructure costs are used to direct development into the PFAs. The State created the Job Creation Tax Credit, Live Near Your Work, and the Voluntary Brownfields Cleanup and Redevelopment incentive programmes to encourage business and people to locate inside the PFAs (Cohen Citation2002; Knaap Citation2005). Furthermore, Maryland established the Rural Legacy Program to preserve environmentally sensitive lands, and authorised local governments to adopt the TDR programmes in which the PFAs serve as receiving areas (Maryland Annotated Code Article 66 B Land Use § 11.01) and to establish purchase of development rights programmes to protect farmlands participating in the Rural Legacy Program.

In 2009 Maryland enacted the Smart Growth Goals, Measures, and Indicators and Implementation of Planning Visions Law that requires local planning commissions/boards to submit annual reports addressing smart growth measures and indicators including growth amounts, densities, numbers of new residential and commercial building permits issued, and amounts of farmland acres preserved. Also, localities should develop a percentage goal and a timeframe for achieving the state policies to concentrate development within the PFAs. Annual reports should indicate local regulations enacted or changed in order to implement the state planning visions (Maryland Annotated Code Article 66 B, S 3.10.c.1). In December 2011, the State adopted PlanMaryland, the state’s first comprehensive plan that guides future land-use planning to create smart and sustainable development.

5. Research findings

5.1. Smart growth applications in the cities/towns

The content analysis of the case study cities/towns’ most recent comprehensive plans shows variations in their embracement of smart growth policies (see ). Laurel has the highest smart growth profile, while Walkersville has the lowest. Most case study cities/towns adopt smart growth policies to accommodate future growth and reduce its potential negative impacts. Easton is the only town that applies several growth controls including UGBs, greenbelts, and phasing development. Historic preservation policies are widely adopted, and mixed-use development and downtown revitalisation policies are used to stimulate economic growth and reduce traffic congestion. About 60% of the cities/towns establish residential densities with more than 3.5 housing units per acre, while 70% have Adequate Public Facilities Ordinances (APFOs) or other provisions to ensure the adequacy of public infrastructure and services to support new development. Half of the cities/towns propose conservation policies to protect forests, open space, and other environmentally sensitive lands.

Table 2. Findings of the content analysis of city/town comprehensive plans.

The examination of the technical capacity of city/town planning departments produces two major groups of cities/towns: a group with high levels of both PC and another with low capacity levels. suggests positive effects of technical PC on city/town applications of smart growth policies to reduce urban sprawl, which supports the first research hypothesis. Easton, Frederick, Gaithersburg, and Laurel have high levels of PC and smart growth applications, while Brunswick, Cumberland, Havre de Grace, and Walkersville have low PC and smart growth profiles. Salisbury and Taneytown with no professional planners have formed city–county agreements that enable county planning departments to perform city land-use planning. Therefore, their smart growth applications are affected by the extent of their county embracement of anti-sprawl policies.

Table 3. City/town levels of technical planning capacity and smart growth applications.

Furthermore, demonstrates that historic preservation policies are adopted by all case study cities/towns, while Transit Oriented Development (TOD) and infill development are applied by cities/towns with high technical PC such as Easton, Frederick, and Laurel. Mixed-use development policies are used by Brunswick, Cumberland, Havre de Grace, and Walkersville that have low technical capacity and by Salisbury and Taneytown receiving county’s technical assistance in land-use planning. Cities whose planning is performed by county planning departments apply overlay zoning, downtown revitalisation, and cluster development to accommodate future growth.

The following narratives explain factors contributing to smart growth applications in four pairs/groups of cities/towns: (1) Gaithersburg and Frederick, (2) Laurel, Salisbury, and Cumberland, (3) Eason and Havre de Grace, and (4) Taneytown, Brunswick, and Walkersville. They address the research hypotheses exploring the effects of the technical capacity of city/town planning departments/divisions, county adoption of growth management policies, public concerns about rapid growth and its unintended consequences, and applications of growth controls by neighbouring jurisdictions.

5.1.1. Gaithersburg and Frederick

Gaithersburg and Frederick are the largest cities among the case study cities/towns (59,933 and 65,239 people, respectively). They witnessed steady population growth because of their location in the region of Washington, DC, the US capital. Their high smart growth profiles can be explained by the first three hypotheses. However, the case study analysis of cities/towns does not provide sufficient evidence to support the fourth hypothesis regarding the effects of growth control policies adopted by neighbouring jurisdictions.

Gaithersburg is surrounded by unincorporated areas that would be annexed in order to expand the city horizontally (). It has adopted smart growth policies such as high residential density with an average of 8.73 housing units per acre, cluster development, infill development, and mixed uses to accommodate future growth. Also, the city established an APFO to ensure that new development would meet city standards for traffic impacts, school, water and sewer capacity, and fire and emergency services provisions. Gaithersburg’s high technical PC (more than one-third of the planning staff has graduate degrees: two in planning and one in non-planning fields) has enabled it to apply smart growth policies. The city is located in Montgomery County that has established a TDR programme designating the city as a receiving area, which has motivated it to manage its future growth.Footnote4 As residents called for managing growth to address concerns about urban sprawl, the City Mayor appointed a Smart Growth Committee to study land-use issues, which led to the adoption of Gaithersburg’s Smart Growth Policy document in 1999.

Frederick City is adjacent to agricultural lands presenting an opportunity for future growth (); however, the insufficiency of water and sewer capacity has slowed down land annexations. The city has applied smart growth policies including high density with an average of 7.83 housing units per acre, compact development, and an APFO to accommodate growth and ensure the adequacy of public facilities. The city’s high technical PC (half of the planners have a graduate degree: three in planning and two in non-planning fields) has enabled it to manage future growth. Frederick County did not seem to have significant impacts on the city’s land-use policies till 2008 when the county adopted an initiative to update its comprehensive plan and designate growth areas. The county initiative stimulated development in existing municipalities including Frederick City. Residents are in favour of the city’s growth as a regional centre, but call for preserving its historic character and limiting sprawl that leads to traffic congestion and inadequate infrastructure.

5.1.2. Laurel, Salisbury, and Cumberland

Laurel, Salisbury, and Cumberland are medium-sized cities with 25,115, 28,925, and 20,859 inhabitants, respectively, as of 2010. Laurel has the highest smart growth profile and is the least sprawling, while Cumberland has the lowest profile and is the most sprawling. The City of Laurel supports the research hypotheses on the effects of technical PC, public concerns about growth, and neighbouring jurisdiction adoption of growth controls. Salisbury’s lack of public concerns about sprawl and focus on social problems seem to hinder potential land-use reforms (hypothesis three). On the other hand, Cumberland’s desire to reverse its declining growth has led to the use of revitalisation policies to stimulate economic growth.

Laurel applies smart growth policies to respond to rapid growth resulting from its midway location between Washington, DC, and Baltimore (). The case study analysis supports all, but the second, research hypothesis. There is no sufficient evidence showing effects of county applications of smart growth management policies. Laurel’s technical PC (four full-time planners with graduate degrees) and public preferences to manage future growth led the Mayor to support smart growth policies. Prince George’s County where the city is located was inactive in smart growth policies till the early 2000s.Footnote5 However, Laurel’s proximity to Montgomery County adopting a TDR programme has caused growth spillover. Therefore, the city adopted smart growth policies that encourage economic growth and reduce traffic congestion resulting from rapid growth. For example, it applied cluster development, PUD, mixed uses, and TOD. Also, it created a commercial village along the main street and an overlay zone for high residential densities. Laurel’s subdivision ordinance sets conditions for the availability of water resources and utilities to serve new development.

Salisbury has grown along highways US13 and US50 (). It has excessively annexed farmlands representing 14% (1270 acres) of its total land area as of 2007. Since the city does not have its own professional planners, it has formed an agreement with Wicomico County by which the County Department of Planning, Zoning and Community Development performs city planning functions. The county has not adopted growth controls and attempts to accommodate urban growth. Therefore, the city applies land-use policies such as medium residential density (an average of 3.98 housing units per acre) and infill development to accommodate growth. Elected officials’ disinterests in managing city growth and concerns with resolving problems of crimes, traffic jams, and unemployment reflect the public indifference to urban sprawl.

Cumberland provides different insights about the research hypothesis. It has low technical PC (one full-time planner with a master’s degree in planning), and receives technical assistance from both the county and state planning departments. The public has been concerned with the city’s steady decline as a result of the demise of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and railroad lines (City of Cumberland Citation2004). The city’s geographic features limit its ability to grow as it is surrounded by steep slopes and bedrocks in the northwest and by floodplains, forests, and agriculture lands preserved by State programmes in the south (). Therefore, Cumberland adopts smart growth policies that attract new business and improve its economy. The city applied policies of compact and infill development, and downtown and neighbourhood revitalisation, and created a conservation zone and a viewship protection ordinance to conserve natural resources.

5.1.3. Easton and Havre de Grace

Easton and Havre de Grace represent small communities (15,945 and 12,952 residents, respectively). Interestingly, Easton has a higher smart growth profile than Havre de Grace, but is more sprawling in terms of land consumption and percentage of multi-unit housing structures. The Town of Easton supports the research’s first three hypotheses. On the other hand, Havre de Grace provides insufficient evidence to support the first two hypotheses as its land-use planning is mostly influenced by public concerns about future growth (hypothesis three) and the technical assistance provided by the State department of planning.

Easton’s proximity to the Chesapeake Bay made it subject to development restrictions set by the Maryland Critical Areas Act. The town technical PC (three full-time planners with graduate degrees) has enabled it to apply growth controls. Also, its location in Talbot County adopting downzoning policies has stimulated the town’s rapid growth, which raised public concerns about urban sprawl. Therefore, Easton creates a UGB, limits future annexations to lands located in priority growth areas, and proposes a greenbelt formed mostly by farmlands preserved by State land preservation programmes and county agricultural easements (). The town applies mixed-use development, downtown revitalisation, and historic preservation policies to encourage economic growth and reduce traffic problems; and sets conditions for the availability of public facilities and services to permit new development. It issued an ordinance to conserve wetlands, forests, and open space. However, resident preferences led the town to allow low-density development (an average of 2.27 housing units per acre).

Havre de Grace’s growth is restricted by protected and public lands in the south and the Chesapeake Bay in the east (). The city’s low technical PC (none of the city’s staff has a planning degree) has limited its land-use planning. Its pro-growth county (Harford) does not seem to influence the city’s planning as it has not adopted land-use policies to curb urban sprawl. The city’s desire to accommodate future growth and maintain its small and historic town characters has led it to seek the State’s technical assistance in land-use planning, which enabled it to adopt smart growth policies such as high densities, mixed uses, downtown redevelopment, and historic preservation.

5.1.4. Taneytown, Brunswick, and Walkersville

Taneytown, Brunswick, and Walkersville are the smallest among the case study cities/towns (6728, 5870, and 5800 people, respectively). They have low levels of technical PC and smart growth applications. Public concerns about growth motivated Taneytown and Brunswick to apply smart growth policies (hypothesis three). The county’s technical assistance has enabled Taneytown to adopt land-use policies that address water problems and respond to local needs.

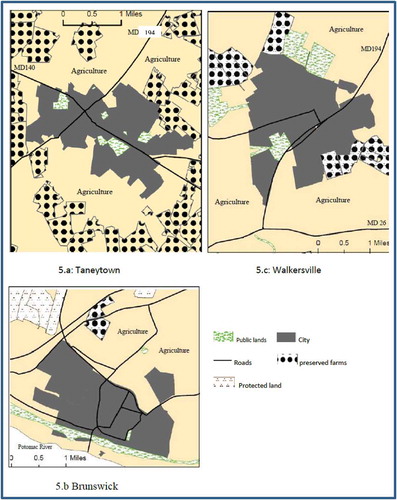

Taneytown has grown along highways MD194 and MD140 and is surrounded by agricultural lands (). Its lack of surface water, reliance on groundwater, and problems with water contamination have limited its growth capacity. Since Taneytown does not have a professional planner, but a Zoning and Code Enforcement Officer, it formed a city–county agreement through which Carroll County planning department performs the city’s land-use planning. The county promotion of anti-sprawl policies has led the city to apply compact development and traditional neighbourhood design; to set conditions for adequacy of schools, roads, fire, police, water, and sewer services in new development; and to create open space zones to preserve parks, forests, and other natural areas. Also, the city planning commissioners who are motivated by the public preferences have supported smart growth policies to maintain a small town character and address water issues.

Brunswick is surrounded by floodplains in the south and protected land in the north (). Despite its low technical PC, the city attempted to comply with the State’s PFA density requirements of 3.5 housing units per acre in order to receive state money to upgrade its infrastructure. Frederick County where the city is located does not seem to affect city land-use planning. However, the public desire to revitalise the city and attract new business has motivated it to adopt smart growth policies such as PUDs and main street redevelopment. It enacted an APFO to ensure the adequacy of public facilities and services to support new development, and passed a forest conservation ordinance to balance natural protection and urban development.

Walkersville grows along highway MD194 that connects it with Frederick City (). It has the lowest levels of both technical PC (one part-time planner) and smart growth applications among the case study cities/towns. The town has attempted to increase its tax revenue base by excessively annexing agricultural lands representing 40% (1196 acres) of its total land area as of 2010. Also, residents’ opposition of multifamily housing and concerns about crimes that may accompany high residential densities have led the town to establish low residential density with an average of 2.95 housing units per acre. However, Walkersville adopted an APFO to ensure the sufficiency of roads, water services, and schools to support new development.

5.2. Summary of the analysis findings

summarises major findings of the examination of the research hypotheses. The case study analysis agrees with the first three hypotheses, but does not provide sufficient evidence to support the fourth hypothesis as explained below.

Table 4. Factors contributing to city/town applications of smart growth policies.

1st Research hypothesis (effects of city/town technical PC on applications of smart growth policies) is evident by the research analysis. In general, cities/towns with high technical PC tend to have high profiles of smart growth applications, which agrees with Brody et al. (Citation2006) and Ali (Citation2007). The high technical capacity of the planning departments of Laurel, Gaithersburg, Frederick, and Easton has enabled them to apply land-use policies that balance economic growth and environmental protection. On the other hand, the low PC of Havre de Grace, Brunswick, and Walkersville has contributed to their low levels of smart growth applications.

2nd Research hypothesis (impacts of county adoption of growth management policies on city/town smart growth applications) is demonstrated by the case study cities/towns. For example, Montgomery County’s TDR programme designating Gaithersburg as a receiving area has motivated the city to adopt smart growth policies that address growth pressures. Also, Talbot County’s land easement programmes preserved farmlands around Easton, which enabled the town to adopt a UGB and propose a greenbelt to contain future growth. When Carroll County planning department performs Taneytown’s planning functions through city–county agreements, it shapes the city’s land-use planning according to the county’s anti-sprawl policies. Also, county technical planning assistance has helped Cumberland and Salisbury apply smart growth policies to accommodate future growth and address city problems.

3rd Research hypothesis (effects of public concerns about rapid urban growth and its unintended consequences on city/town applications of smart growth policies) is evident by most cities/towns. Agreeing with Nguyen (Citation2009), resident concerns about the negative effects of urban sprawl have contributed to Frederick, Gaithersburg, Laurel, and Easton’s applications of smart growth policies to reduce urban sprawl and mitigate its negative impacts. On the other hand, Walkersville’s resident preferences of low density have contributed to its sprawling development patterns. Similarly, the public disinterest in land-use reforms or growth controls led Salisbury to excessively annex farmlands.

4th Research hypothesis (impacts of adopting growth controls by neighbouring jurisdictions on city/town applications of smart growth policies to reduce urban sprawl) is supported by the City of Laurel. The proximity of Laurel to Montgomery County creating land preservation programmes has led to growth spillover that motivated the city to manage its future growth. However, other cities/towns do not provide sufficient evidence to support that hypothesis.

Furthermore, the case study analysis points to other factors contributing to city/town applications of smart growth policies to combat urban sprawl. State mandates make cities/towns adopt smart growth policies, as suggested by Carruthers (Citation2002). For instance, the state mandates of the preparation of water resource and municipal growth elements have led Gaithersburg and Havre de Grace to limit future annexations. In addition, farmlands and forests protected by State land preservation programmes enabled Easton to propose a greenbelt and contain the town’s growth. On the other hand, the State’s PFA incentive programme has not prevented Walkersville from establishing low-density residential development. This observation supports Downs (Citation2005) and Knaap (Citation2005) on the ineffectiveness of incentives to ensure local compliance with state land-use policies.

6. Conclusions and policy implications

This research paper investigates local factors contributing to city/town applications of smart growth policies to combat urban sprawl in the State of Maryland, USA. The case study analysis supports the first three research hypotheses regarding the effects of city/town technical PC, county adoption of growth management policies, and public concerns about growth patterns on city/town decisions to apply smart growth policies. However, the analysis does not provide sufficient evidence to support the fourth hypothesis on impacts of growth controls adopted by neighbouring jurisdictions.

Agreeing with Brody et al. (Citation2006) and Ali (Citation2007), cities/towns with high technical PC apply smart growth policies to manage future development. Therefore, it is important to increase city/town PC in terms of education and personnel in order to improve local land-use planning in general, and smart growth practices in particular. Both the State and the American Planning Association-Maryland Chapter can motivate city/town planners to seek further planning education, and provide them with professional training. The State should help small cities/towns generate revenues sufficient to hire professional planners who are able to reform local land-use policies. Also, the State’s regional planning offices should encourage cities/towns that lack the PC to seek the State’s technical assistance in smart growth applications.

Cities/towns located in counties adopting anti-sprawl policies are usually informed about the negative effects of urban sprawl and are introduced to a variety of land-use policies to manage urban growth through county plans, meetings, and technical assistance. Thus, they tend to apply smart growth policies to combat sprawl, as shown in Gaithersburg and Easton. This observation points to the importance of promoting county leadership in smart growth applications. Also, enhancing city–county coordination is required in land-use planning in order to design more effective policies that address local needs and growth challenges.

In addition, the research analysis demonstrates the effects of public concerns about urban growth on city/town land-use policies, which agrees with Nguyen (Citation2009). When residents are concerned with negative effects of urban sprawl, cities/towns attempt to manage future growth as shown in Frederick City. On the other hand, resident preferences of low residential density can contribute to urban sprawl as evident by the Town of Walkersville. Therefore, it is important to raise the public awareness of the negative effects of urban sprawl, and to introduce residents to a broad range of smart growth policies that can balance economic development and environmental protection.

Finally, the case study analysis indicates that state mandates lead cities/towns to adopt smart growth policies as suggested by Carruthers (Citation2002). However, State incentive programmes do not ensure local compliance with state policies, as Downs (Citation2005) and Knaap (Citation2005) argued. Therefore, further research is needed to explore effective state policies that can help increase local applications of smart growth to combat urban sprawl.

To conclude, the research findings point to needs for more state efforts to rebuild the technical capacity of city/town planning agencies and to promote smart growth applications. Counties can play leading roles in managing local growth as they influence municipal land-use planning through collaboration and technical assistance. Also, the State should create educational programmes to raise the public awareness of the negative effects of urban sprawl and to improve resident knowledge of how smart growth policies can help resolve city/town problems and improve the quality of life. Enhancing state–local partnerships will motivate cities/towns to reform their land-use planning. All of this would improve local applications of smart growth policies and reduce urban sprawl.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amal K. Ali

Amal K. Ali is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Geosciences at Salisbury University, USA. She teaches and conducts research in Land Use Planning and Smart Growth. She has published several articles examining smart growth applications to reduce urban sprawl and create sustainable communities.

Notes

1. Levels of the planner–population ratio are estimated as: 1 = 1:15,000 people or more; 2 = 1:10,000 to 1: <15,000; 3 = 1:5000 to 1: <10,000 people; and 4 = 1: <5000 inhabitants.

Levels of planner education are calculated as: 1 = less than BSc; 2 = BSc; 3 = MSc or higher degrees in non-planning disciplines; and 4 = MSc or higher degrees in planning.

Average years of professional planning experience are <2 years, 2–5, 6–9, 10–13, and 14 or more years.

2. Public concerns about rapid urban growth and its unintended consequences were identified in the interview as one of smart growth motivators. Planners were asked to indicate factors motivating their cities/towns to adopt smart growth policies, and to explain the extent of public concerns about sprawl and needs to manage future growth.

3. PFAs are defined as existing communities, areas designated for revitalisation by Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development, and enterprise zones established by the state or the federal government. Counties may identify other areas as PFAs including: communities existing prior to 1997 and having an allowed average density of 2.0 units per acre; areas outside existing communities with a permitted density of 3.5 units per acre; and undeveloped lands within designated growth areas and having a permitted residential density of 3.5 or more units per acre (Cohen Citation2002).

4. Montgomery County established a TDR programme in 1981, and a Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) programme in 1990 (Lynch & Lovell Citation2003).

5. Prince George’s County began to participate actively in the state incentive programmes to preserve farmlands and encourage development inside the PFAs in 2004.

References

- Ali AK. 2007. Understanding local planning agency power in Florida. J Archit Plann Res. 24:325–337.

- American Planning Association. 2012. Policy Guide on Smart Growth. Available from: http://www.planning.org/policy/guides/adopted/smartgrowth.htm?print=true

- Baldassare M, Wilson G. 1996. Changing sources of suburban support for local growth controls. Urban Stud. 33:459–472.

- Berke PR, French SP. 1994. The influence of state planning mandates on local plan quality. J Plann Educ Res. 13:237–250.

- Boarnet MG, McLaughlin RB, Carruthers JI. 2011. Does state growth management change the pattern of urban growth? Evidence from Florida. Reg Sci Urban Econ. 41:236–252.

- Brody SD, Carrasco V, Highfield WE. 2006. Measuring the adoption of local sprawl reduction planning policies in Florida. J Plann Educ Res. 25:294–310.

- Burby RJ, May PJ, Berke PR, Dalton LC, French SP, Kaiser EJ. 1997. Making governments plan: state experiments in managing land use. Baltimore (USA): Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Carruthers J. 2002. The impacts of state growth management programmes: a comparative analysis. Urban Stud. 39:1959–1982.

- Chapin T, Connerly C. 2004. Attitudes towards growth management in Florida: comparing resident support in 1985 and 2001. J Am Plann Assoc. 70:443–452.

- City of Cumberland. 2004. Comprehensive Plan.

- Cohen JR. 2002. Maryland’s smart growth: using incentives to combat sprawl. In: Squires G, editor. Urban sprawl: causes, consequences and policy responses. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

- Dalton L, Burby R. 1994. Mandates, plans, and planners: building local commitment to development management. J Am Plann Assoc. 60:444–461.

- Downs A. 2005. Smart growth: why we discuss it more than we do it. J Am Plann Assoc. 71:367–378.

- Edwards M, Haines A. 2007. Evaluating smart growth: implications for small communities. J Plann Educ Res. 27:49–64.

- Hawkins CV. 2011. Smart growth policy choice: a resource dependency and local governance explanation. Policy Stud J. 39:679–707.

- Hirt S. 2007. The mixed use trend: planning attitudes and practices in Northeast Ohio. J Archit Plann Res. 24:224–244.

- Knaap G. 2005. A requiem for smart growth? In: Mandelker D, editor. Planning reform in the new century. Chicago (USA): Planners Press.

- Litman T. 2012. Smart growth reforms changing planning, regulatory and fiscal practices to support more efficient land use. Victoria (Canada): Victoria Transport Policy Institute. Available from: http://www.vtpi.org/smart_growth_reforms.pdf

- Lynch L, Lovell SJ. 2003. Combining spatial and survey data to explain participation in agricultural land reservation programs. Land Econ. 79:259–276.

- Maryland Annotated Code Article 66 B Land Use.

- Nguyen M. 2009. Why do communities mobilize against growth: growth pressures, community status, metropolitan hierarchy, or strategic interaction? J Urban Aff. 31:25–43.

- Norton R. 2008. Using content analysis to evaluate local master plans and zoning codes. Land Use Policy. 25:432–454.

- O’Connell L. 2009. The impact of local supporters on smart growth policy adoption. J Am Plann Assoc. 75:281–291.

- Schneider M, Kim D. 1996. The effects of local conditions on economic growth, 1977–1990: the changing location of high-technology activities. Urban Aff Rev. 32:131–156.

- Wassmer R. 2001. An economist’s perspective on urban sprawl influences of the “Fiscalization of Land Use” and urban-growth boundaries. Sacramento (USA): Senate Publications.

- Wassmer R, Lascher E. 2006. Who supports local growth and regional planning to deal with its consequences? Urban Aff Rev. 41:621–645.

- Yin M, Sun J. 2007. The impacts of state growth management programs on urban sprawl in the 1990s. J Urban Aff. 29:149–179.