Abstract

This paper examines the asset vulnerability and livelihood strategies of refugees and the urban poor in slum settlements of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The Asset Vulnerability Framework is used as the analytical framework of how household’s assets are affected by vulnerability. Using qualitative analysis, factors which impact on the livelihood assets of both groups are examined. The paper focuses on the five main assets as indicated by Moser, while conceptualising further the assets which both populations aspire to accumulate, and which are necessary for them to prosper – rights, in this case the Right to the City. The paper, therefore, attempts to develop linkages between these areas: asset vulnerability, displacement and the Right to the City.

1. Introduction

The Great Lakes crises of the 1990s had many repercussions for the populations of East African countries (Young Citation2006). Hundreds of thousands were displaced, both internally and externally as refugees fled to neighbouring states (UNHCR Citation1997a). In the intervening period a considerable number also settled permanently in other countries, including Tanzania, historically one of the most generous countries for refugee hosting in Africa (Milner Citation2009). With the resurgence of violence in Burundi in 2015 due to the controversial re-election of President Nkurunziza for a third term (BBC News, Citation2015), and the ongoing violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (UNHCR Citation2016), a new wave of forced migrants is making their way across borders and into Tanzania (UNHCR Citation2015a).

This paper examines the coping mechanisms which the refugeesFootnote1 in Dar es Salaam use to develop sustainable livelihoods strategies through the accumulation of assets, in order to try and protect against vulnerability. Their assets are compared to the Tanzanian population whom they live adjacent to in the informal settlements/slumsFootnote2 of Dar es Salaam – the indigenous group with whom they compete with for resources. The city of Dar es Salaam was chosen for this case study for the following reasons: first, several previous small scale studies have been conducted on urban refugees in the city, by both Asylum Access Tanzania (AATZ) (AATZ, Citation2011) and Ezra Ministries of Tanzania (Citation2008), which confirm the existence of this population. Such research had not been conducted on any other city in Tanzania before the fieldwork period, and so given the research topic, it was prudent to choose a city where a known refugee population already existed.

Furthermore, the existence of organisations such as AATZ and the Tanganyika Christian Refugee Society (TCRS) which both work with refugees in Dar es Salaam made data collection feasible. Without these partnerships the fieldwork would have been severely restricted as conducting the interviews alone in slum settlements would not have been possible. In addition, as Dar es Salaam is the largest city in one of the more stable countries in East Africa, the policy implications for refugees in the region extend beyond its borders. As a host country of refugees from Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo and in the past Rwanda, how Tanzania copes with its refugee population will have implications for all of the neighbouring states. The comparison of the two groups is intended to give a snapshot of the relative poverty experienced by the refugees and to consider their position within the wider context of vulnerable populations. As Jacobsen (Citation2006) notes, urban refugees are ‘subsets of two larger populations; other foreign born migrants, and, because they live amongst them and share their challenges, they are also a subset of the national urban poor’ (p. 276).

This paper is divided into sections: first, an overview is presented on the changing trends in displacement, followed by an examination of the methodology and the asset vulnerability framework, linking this to the concepts of displacement and the Right to the City. This is followed with a discussion on the findings of the research and the development of the nexus linkages going forward in the concluding section.

2. Changing trends in displacement

The encampment policy for refugees adopted throughout sub-Saharan African countries has resulted in numerous camps mushrooming across the continent (Crisp Citation2010), an example being the Daadab camp in North Western Kenya, the largest refugee camp in the world (UNHCR, Citation2015b). This camp was created in 1992 and now holds a population of 263,036 (as of 15th September 2016) and three generations of Somali refugees ([UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Citation2015a). When camps such as this were established, it was not envisioned that they would develop into the permanent structures that they have become (Crisp & Jacobsen Citation1998; Zetter & Long Citation2012; Crawford et al. Citation2015), with thousands of children being born inside the camps never knowing any other life. However, this trend is resulting in more and more refugees seeking independence and better opportunities in cities, with 58% of all refugees now residing in urban areas (Urban Refugees 2016).

The challenges for refugees arriving in new cities is enormous, and many end up living in the informal settlements alongside the established urban poor (Crisp et al. Citation2012). Their displacement leaves them vulnerable, as often they leave behind valuable assets when fleeing. They are also without traditional social networks to depend on in times of crisis – they are stripped of not just financial but social and physical assets (Maria Pinto et al. Citation2014). Surveys conducted in various cities to date (such as the Sanctuary in the City Series conducted by the Overseas Development Institute) have uncovered that refugees and urban poor encounter many of the same problems due to lack of services and adequate infrastructure (Pavanello et al. Citation2010; Haysom Citation2013). However, the growing urban population of refugees have to contend with added difficulties regarding legal status and problems such as racism, and so often remain hidden within the wider population in attempts to avoid detection.

Over the years, UNHCR has attempted to tackle urban refugee issues through the introduction of several policies and subsequent addendums (Citation1997b, Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2011, Citation2012). Criticism of the 1997 Policy on Urban Refugees which was considered to be biased towards camps and lacking in practical suggestions on how the implementation of the policy would be achieved were not completely addressed in the revised 2009 version (Edwards Citation2010), the UNHCR Policy on Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban Areas. These have been highlighted (Morris & Ben Ali Citation2015) in particular UNHCR’s lack of attention to the protection of human rights of refugees. In addition, the 2009 policy document acknowledges that issues have existed in the past regarding a fraught relationship in some instances between UNHCR staff and refugees, which may in part explain the reluctance to push the urban refugee agenda; paragraph 84 noting that ‘UNHCR’s relationship with refugees in urban areas has on occasion been a tense one, characterised by a degree of mutual suspicion’ (UNHCR Citation2009a, p. 14). This discourse within UNHCR has historically also been compounded by the strong preference of governments to keep refugees in remote parts of countries, forcing them to remain separate from the host society (Kibreab Citation2007) as well as allowing the responsibility of their care to fall firmly on the shoulders of UNHCR. It is a case of ‘out of sight out of mind’ to a certain extent, noting that refugees are often seen as ‘a factor that exacerbates the urban condition’ (Kibreab Citation2007, p. 29).

3. Methodology and analytical framework

The research for this paper was conducted between March 2014 and June 2015 in three settlements across Dar es Salaam city. A research permit was granted prior to beginning the fieldwork by COSTECH, the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology. The three settlements were chosen after lengthy discussions with both the refugee and urban settlement organisations working in Dar es Salaam. They were chosen on the basis of the following: (1) the settlements were known to have a sizeable refugee population based on previous research work conducted; (2) they were accessible during times of flooding; (3) they had significant numbers of potential participants from both partner organisations living in the area; and (4) the cooperation of the local mtaa (sub ward) office for entering the settlement areas was available (this was confirmed through the research assistants who made contact with different ward offices). The research was qualitative in nature, with the data collection consisting of 94 semi-structured interviews and 2 focus groups in total; 30 interviews with refugees, 30 with Tanzanian urban poor and 34 with various UNHCR, UN-HABITAT, NGOs, INGOs, local government and academic staff. One focus group was conducted with refugees and one with the Tanzanian urban poor. Interviews were conducted in English, Kiswahili, French, Kibembe and Lingala.

The interviewees from both the refugees and Tanzanian urban poor group were chosen with the assistance of AATZ and Community Centre Initiatives. Both organisations work with the groups being researched across Dar es Salaam. Participants were chosen on the basis of gender and age in order to attempt to get a wider cross section of both groups. They were contacted by the research assistants and given a clear briefing of what the interviews would entail – the topics, length and confidentiality clause.

The focus groups conducted were done so with participants from the interviews, and the research assistants acted as facilitators/translators for the sessions. Given the relatively small sample size of this research, the authors believed it would be more beneficial to go further in-depth with this known population than to recruit new participants for the focus groups. The focus group participants were chosen on the basis of their language, gender, age and income in order to get a wider range of views from both groups. The focus groups were limited to discussing a small number of key themes that had come to light during the interview stages that the authors wanted to explore in more depth.

The sample size for both groups is relatively small, and so the representativeness of the data to the wider refugee and Tanzanian urban poor populations as a whole cannot be claimed to be generalisable and that is not the intention of this research. It is intended to 'generate an intensive examination of a single case ... to then engage in a theoretical analysis' (Bryman Citation2012, p. 71) Nevertheless, certain trends can be acknowledged and give a partial and insightful snapshot of the needs of both communities. Therefore, this case study attempts to further the discussion on the linkages between displacement, asset vulnerability and the Right to the City that will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

4. The asset vulnerability framework

There exists a large body of work on the related topics of asset accumulation, sustainable livelihoods, social protection and vulnerability,Footnote3 beginning with the work on entitlements of Sen (Citation1981), and developed and supplemented by later work including Chambers and Conway (Citation1991), Chambers (Citation1995), DFID (Citation1999) and Rakodi and Lloyd Jones (Citation2002). This approach has also been adopted in humanitarian practise, with international NGOs such as Oxfam linking its sustainable livelihoods analysis to a rights-based approach since 1994 (Moser & Dani, Citation2008), most recently updated with its Rights in Crisis campaign (Oxfam Citation2015). This large body of work has led to ‘conceptual confusions’ (Moser Citation1998, p. 3) and an increasingly complex and interlinked plethora of conceptual frameworks regarding these topics. For the purposes of this research and for the sake of clarity, the development of theory in this paper is focused on the asset vulnerability framework developed by Moser. Moser’s asset vulnerabilityFootnote4 framework was chosen for this research as it ‘represents a livelihoods approach to systematically analysing the relationships between the assets and vulnerabilities relevant to the urban poor in the Global South’ (Parizeau Citation2015, p. 162). It is appropriate for this type of research as the framework ‘emphasises the relationship between assets, risks and vulnerability. At the operational level, this relationship is at the core of social protection policy and programs’ (Moser Citation2006, p. 9).

The framework is a useful tool to examine further the strategies adopted by urban refugees, a subset of the urban poor. Much work has already been completed on the livelihoods strategies which have been adopted by the urban poor, and the concept is being considered more frequently in the context of urban refugees (see Campbell Citation2006; Metcalfe et al. Citation2011; Pantuliano et al. Citation2012; Haysom Citation2013). The potential benefits and reframing of refugee crises as development opportunities are also linked to this creation of effective livelihoods strategies, as can be seen in the work of academics such as Jacobsen (Citation2002) and Zetter (Citation2014). A caveat is necessary at this point to clarify that in choosing the asset vulnerability framework, and so focusing on the assets defined by Moser, the authors are limiting the scope of issues that will be discussed in relation to other urban populations. However, this approach does not assert that the themes examined in this framework are the only relevant issues for the two populations, or even the most important. Given the plethora of concerns which affect the urban poor, some limits were required to allow a more in-depth discussion on the Right to the City in this context, and for the reasons outlined above the asset vulnerability framework was considered to be fit for this purpose. However, the issues addressed in this paper are not intended to represent the apogee of the challenges facing the urban refugees and Tanzanian groups, nor do they purport to be.

Nonetheless, urban refugees do possess a unique set of vulnerabilities (Crisp et al. Citation2012) and arguably face greater challenges than indigenous populations in reducing vulnerability, and so a more complete understanding of the complexities regarding their difficulties may help develop better programmes to meet their needs. In this paper, the focus will remain on the five main assets as indicated by Moser (Citation1998) – physical, financial, social, human and natural capital,Footnote5 but it will also conceptualise further the Right to the City which both urban refugees and Tanzanian urban poor aspire to accumulate. Political capital is not part of Moser’s asset vulnerability framework; however, it is an important factor in asset vulnerability. Those who are asset poor often lack this key ingredient in pressuring institutional structures to allow or assist them to accumulate assets (e.g. planning departments providing easier methods of land registry, or banks which provide loans to those without formal paperwork).

This is the crucial connection between the asset vulnerability framework and the Right to the CityFootnote6; without political capital asset poor individuals can be actively or passively hindered from full inclusion in city life by urban institutions and governance structures. This capital becomes even more important for two reasons: (1) political capital is often a requirement for ‘contesting claims related to other assets’ (Moser & Norton Citation2001, p. 19); (2) much responsibility for social policy has been placed on traditional institutions in developing countries, despite their sometimes considerable limitations (Moser & Dani, Citation2008) such as staff capacity, corruption or limited funding.

The paper, therefore, attempts to develop linkages between these areas; asset vulnerability, displacement and the Right to the City. In attempting to link these three concepts, this research hopes to build on the extensive body of work which already exist on the topics of livelihoods, including refugee livelihoods (De Vriese Citation2006; Omata Citation2012) and the Right to the City paradigms, in addition to discussions on political capital. While the asset vulnerability framework views the issues at a household level and day-to-day survival strategy, linking this with the Right to the City connects this household level to the relationships between the state and the citizen; the ‘long-term growth of people’s social, political and human capabilities and freedoms’ (Moser & Norton Citation2001, p. 37).

5. Integrating asset and rights-based approaches

Conway et al. (Citation2002) notes that there exists ‘considerable overlap in the basic principles underpinning livelihoods and rights approaches to poverty reduction’ (pg 3; Moser & Norton Citation2001). This paper acknowledges this and attempts to expand on the existing body of work on both topics, through the specific prism of asset vulnerability, displacement and the Right to the City. However, first, the different scales at which these concepts operate at must be acknowledged. Asset-based approaches tend to focus attention on the dynamics of well-being at the household level, while rights-based approaches often focus at the more macro, institutional scale (Moser & Norton Citation2001; Moser Citation2007).

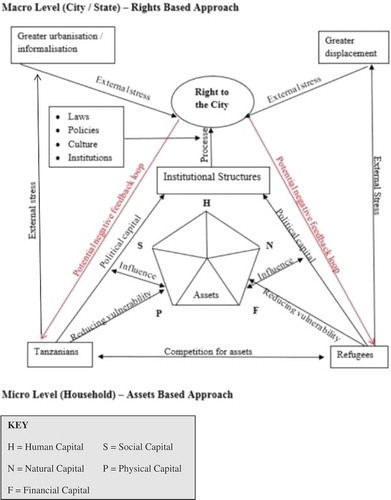

In essence the difference lies in the way risk is considered; at the household level risk is a danger, while at the macro level risk can be regarded as an opportunity (Moser Citation2007). However, in recent years, academics have begun to recognise that this dichotomy is not beneficial to examining the needs of low-income populations, and that in reality, there is not a clear cut separation between the two approaches; power at both levels is inevitably interlinked (see ), and so both the macro and micro level factors must be considered when developing effective policies in addressing the needs of vulnerable groups.

Figure 1. The nexus linkages.

Source: Authors, pentagon from DFID (Citation1999).

As Conway et al. (Citation2002) notes, rights analysis can ‘provide insights into the distribution of power’, while asset vulnerability frameworks can highlight areas where this power is lacking at the household level. The importance of rights which can be realised cannot be understated, indeed ‘the capacity to make claims effectively is a significant livelihood capability for most people’ (Moser & Norton Citation2001, p. 40). These claims can vary from claims for land, to voting rights, or in this case, the claim to the Right to the City.

The establishment of rights by the state at the macro level is not sufficient as this does not automatically translate into rights being realised at the micro level. While rights may exist on paper, they are worthless if people cannot claim them. In the case of refugees, Tanzania is a signatory of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its Related Protocol (Chiasson Citation2015), which affords refugees the right to freedom of movement. However, in reality refugees are not permitted to exercise this right and are forced to reside in camps in Western Tanzania. Those refugees that make their way to Dar es Salaam are attempting to exercise their Right to the City in spite of the fact that on paper this right is a given.

The framework of rights which have been established in Tanzania must exist alongside a space where populations can accumulate assets and be permitted to assert their rights. If these two pillars do not exist in tandem, then it is likely that these populations will remain vulnerable. As Moser and Norton (Citation2001, p. ix) note, ‘the underlying logic is that a rights/livelihoods perspective enhances social justice, through the application of non-discrimination and emphasis on ‘equitable accountability’ of the state to all citizens’. It is important to see rights as one mechanism to address the imbalance of power which exists to prevent vulnerable people from acquiring or accumulating assets (Moser & Norton Citation2001). From a broader perspective, it can act as a mechanism to move vertically the power between micro- and macro levels (see ), to gain access to important institutions, as rights do not always equate to power – ‘Rights seek to contain the flow of power like a bottleneck … but power leaks out, and flows around rights’ (Wilson Citation1997, p. 17).

6. The right to the city

The ‘right’ in question in the case of this research is the Right to the City, a concept originally constructed by Henri Lefebvre in his 1968 book Le Droit á la Ville, which examined urban dwellers freedom and access to urban life. Marcuse (Citation2009, p. 190) describes Lefebvre’s right to the city as ‘a cry and a demand, a cry out of necessity and a demand for something more’, stating that the demand of the Right to the City comes ‘from the directly oppressed, the aspiration from the alienated’ (Marcuse Citation2009, p. 191). In order to explore the urban populations of Dar es Salaam within the context of the Right to the City, the meaning of the phrase must first be clarified.

The idea has become quite amorphous, in some cases co-opted and expropriated by various groups claiming that it espouses their claims to the city, and Marcuse (Citation2014) identifies no less than six different readings of Lefebvre’s original work, each with quite diverse interpretations. The phrase itself has become ‘contested territory’ (Boniburini Citation2013, p. 17) as competing factions adopt the concept as an endorsement of their own ideals, often from quite different perspectives. For example, organisations such as UN-HABITAT have incorporated the concept into their programmes as a rights-based approach; however, reactions to this direction have been mixed with some viewing the loss of Lefebvre’s original radical concept in order to achieve a broad consensus as a weakening of the concept (Boniburini Citation2013).

Marcuse notes that Lefebvre’s own thoughts on the right to the city are indeed more radical than others interpretations; they are a call for a revolution of the urban. This approach is also radical in the sense that Lefebvre acknowledged that rights are viewed by many as a ‘bourgeois project’ (Purcell Citation2013, p. 146) and so separate from the disadvantaged groups discussed in this paper. However, Marcuse decries the use of the term ‘right’ as the concept is ‘not a Right in the sense of a legal claim enforceable through the judicial system, but a moral right, an appeal to the highest of human values’ (Marcuse Citation2014, p. 5). The two key tenets of Lefebvre’s original idea remain that (1) the city is an oeuvre, a projection of society, where inhabitants have the right to physically occupy space (the right to appropriation) and (2) all inhabitants (not just citizens) of the city participate in the construction of the city (Boniburini Citation2013). Many academics have contributed to the growing literature which exists on the Right to the City, forming their own definitions of what this means – Harvey (Citation2008) sees it as ‘a right to change ourselves, by changing the city’, while Balbao (Citation2013) highlights the importance of urban inclusion and the acceptance of a plurality of values within communities.

For the purposes of the discussion of the Right to the City, this paper will focus on a ‘strategic reading’ of Lefebvre’s work, as noted by Marcuse (Citation2014). The strategic reading was chosen as it identifies with groups (such as those researched in this study) that are the underprivileged and suffering in urban society, prohibited economically or socially from real inclusion in the City. They are simply seeking ‘to obtain the benefits of existing city life from which they have been excluded’ (Marcuse Citation2014, p. 6). However, the concept is not a simple contest for hegemony as it may first appear. In this instance, it serves as a useful starting point to examine the theory in the context of the research conducted in Dar es Salaam. This development of the theoretical framework will be furthered by Marcuse’s reading of Lefebvre which helps to break down the radical nature of the concept by forming three questions which need to be answered – whose right, what right and what city (Marcuse Citation2009).

In this instance, Marcuse’s interpretation of Lefebvre also helps to bridge the theoretical/practical divide which often exists in urban studies – the interaction of the sometimes quixotic Right to the City and the more concrete asset vulnerability framework will help to allow theory to develop in tandem with practical application in the ‘real city’, not independently of it (Marcuse Citation2009). Indeed, the authors would argue that this dyad of theory and practice, these nexus linkages, are key to the usefulness of the concept of the Right to the City – although Lefebvre’s radical idea is ground breaking, it is not enough on its own, it must create a city where not just material needs but where ‘aspirational needs’ are met (Marcuse Citation2009, p. 193). So, it is not sufficient for a refugee to live in a one-room house today – they must be able to aspire one day to own their own home. This in turn answers the question of what city? It must be a city of the future to cater for the aspirations of its inhabitants, a point which Lefebvre and Marcuse are both insistent on. In addition, it must also be a city that, according to the prevailing analyses of the Right to the City, rejects the capitalist system (Marcuse Citation2009). It is not possible within the scope of this paper to adequately address this point and the surrounding discourse on neoliberalism in relation to the Right to the City, but the connection between the two issues must be acknowledged here nevertheless.

What changes can the city of Dar es Salaam make in the present day to allow this aspirational vision to be realised? Herein lies the usefulness of asset vulnerability viewed through the lens of the Right to the City – it can begin, in some small measure to answer this question, as noted by Boniburini – ‘material practise need imaginaries to envisage comprehensive and complex counter-hegemonic projects, and imaginaries need the experience gained by material practices if eventually they want to materialise these’ (Citation2013, p. 27). The nexus linkages of displacement, asset vulnerability and the Right to the City (Figure 1) discussed in this paper, the authors contend meet this need.

In the case of this paper, the question of whose right is clearly defined – the authors examine the rights of the urban refuges and urban poor of Dar es Salaam; in other words, this paper focuses on not everyone’s rights, but those who do not have it now (Marcuse Citation2009). For refugees, their exclusion is compounded and linked directly to their original displacement and resulting erosion of assets. In the case of the Tanzanian population, while they have not suffered the difficulties of forced migration, they too are denied as their asset vulnerability prevents them from exercising their right to obtain the benefits of the city such as secure income (Marcuse Citation2014). In the following analysis, the vulnerabilities and assets that influence the refugee population and Tanzanian urban poor of Dar es Salaam are presented, as is the interplay between the two groups.

7. Research findings and discussion

7.1. Overview of the vulnerability context of the urban refugee population in Dar es Salaam

Refugees reside in informal settlements throughout the city, which make up to 80% of the residential urban area (UN-HABITAT Citation2010). The vast majority of Dar es Salaam remains informal despite continuing efforts from the government to reduce the level of slums. The combination of an increase in population, 2.9% nationally since the last census, with an increase of 5.6% in Dar es Salaam (NBS Citation2013b), in addition to high levels of migration from rural areas (Kombe Citation2010), has resulted in the rapid growth of the urban space and the inability of the government to effectively provide services for the population influx.

Officially, all refugees are required to reside in camps in Western Tanzania where three camps accept refugees: Nyarugusu, Ndutu and Mtendeli. A very small number are given permits to live in other areas, including Dar es Salaam, usually for medical reasons or due to security and protection concerns (AATZ Citation2011). Until recently, the Government of Tanzania had not publicly acknowledged the existence of the considerable number of refugees in Dar es Salaam; and in an interview with UNHCR staff in 2014, it was confirmed that the number of officially registered refugees residing in the city at the time totalled less than 100.

In 2014, the UNHCR commissioned a scoping exercise on persons of concern in urban areas with a focus on Dar es Salaam, to be conducted by TCRS between September and December of 2014. The scoping exercise was to focus on a sample size of approximately 1000 refugees and asylum seekers, incorporating the three municipalities of Dar es Salaam; Kinondoni, Temeke and Ilala in addition to Morogoro and Bagamoyo. The report intended to gather information on the current situation of urban refugees for the purpose of advocating for the Government of Tanzania to reconsider its strict encampment policy. To-date, the results of this scoping exercise have not been published, and it appears that there is no impetus on the part of the UNHCR or the Refugee Services Department to release this data.

Notwithstanding, the recent survey undertaken suggests a change in Government policy in the coming years as indicated from an interview with a Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) official, who explained the reasons for Tanzania’s continued encampment policy and the Government’s thoughts on urban refugees:

Its simply because over the years we were worried about security, its the over ridding factor, because of the huge numbers involved. But now that we know that we have many refugees we want to document them, and legalise the stay, legalise those who have reasons to justify to stay in any of our cities.

This emphasis on security by Government officials provides some insight into the challenges the authorities perceive to be connected with allowing refugees into urban areas. However, many refugees leave the camps without permission to come to Dar es Salaam in any case, so this is not a reasonable excuse for preventing more refugees from settling in the city. provides information on the interviewee profiles.

Table 1. Comparison of refugee and Tanzanian respondents.

7.2. Physical capital

7.2.1. Housing

Housing is a crucial asset for the urban refugee population for several reasons: First, refugees are not allowed to own property in Tanzania, so even if the group had the means to purchase property, they would not be legally allowed to do so. It must be acknowledged that Moser’s framework identifies physical assets as not just housing, but other materials such as consumer durables (e.g. televisions, bicycles etc.) (Moser Citation2007). However, for the purposes of this paper and limited space the focus will remain on housing. As noted by Moser (Citation2007, p. 41), ‘housing is the first-priority asset, and while it does not necessarily get households out of poverty, adequate housing is generally a necessary precondition for the accumulation of other assets’. Therefore, the prevention of the refugee population in acquiring this asset is a serious obstacle to them pulling themselves out of poverty and also establishing firm roots in the city.

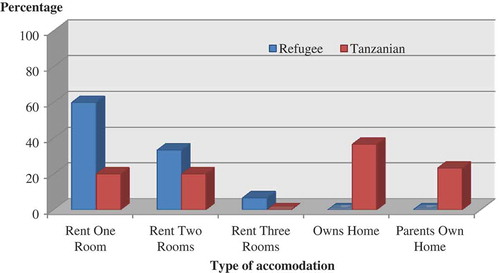

In addition, the lack of secure accommodation generates a host of other problems for the refugees: it results in regular moving of house (and a continuing of the displacement cycle) due to rent increases, poor environmental conditions or disagreements with landlords and neighbours. It also means less ability to earn income as they are not able to rent out rooms as are their Tanzanian neighbours (55.5% of home owners rented rooms) and reduces their abilities to get loans considerably due to lack of collateral (Parsa et al. Citation2011). Furthermore, the housing quality of many of the refugee respondents was very poor; only 56.6% had electricity access at any time and 60% of families lived in one room (see ). Only 13.3% of the refugee population had their own toilets, in comparison to 23.3% of the Tanzanians, and 50% of the refugee respondents were sharing toilets with 5 or more other families, which could be in excess of 24 people as the average household in Tanzania is currently 4.8 persons (UNFPA Citation2015).

It is also important to consider the knock-on effects of not having access to proper housing. As Arun et al. (Citation2013) note, this further stunts households’ ability to exploit the potential of this physical asset, through income diversification strategies such as using the space for setting up a small business. Indeed, it is a key factor in developing resilience against shocks, as it is ‘23% less likely for a household that owns any form of physical asset to experience an adverse shock than for a non-ownership house’ (Arun et al. Citation2013, p. 294).

7.2.2. Housing and the nexus linkages

Housing is an excellent example of where the linkages between asset vulnerability, the Right to the City and displacement are clear to see: at the micro level, the asset vulnerability of all refugees in securing home ownership leaves them vulnerable on several fronts: they are vulnerable to eviction, rent hikes, and to further displacement. They are also forced to live in sub-standard conditions with large families often living in one or two rooms which raise issues of privacy, health concerns but also safety; several of the participants interviewed expressed concern about living in buildings where large numbers of families were sharing but did not know each other.

This is compounded by government failures at the macro level to implement planning policies that will provide adequate housing for these urban poor. While these programmes purport to give poor residents the opportunity to exert their Right to the City, in reality they do the opposite. The adherence to neoliberal policies advocated by De Soto and adopted by the Tanzanian Government which emphasised formalisation of ownership and proper plots has not resulted in the availability of housing for the majority of urban dwellers, it has simply facilitated the accumulation of property of the more financially stable cohort which may currently be living in informal settlements due to lack of available land in the city centre settlements. The stress exerted by the refugees and Tanzanian urban poor at micro level pressures state institutions at the macro level to respond to their needs, the desired outcome being access to the Right to the City for these groups.

Despite the rapid growth of Dar es Salaam as a city, almost 80% of the housing of the urban area is informal settlements (UN HABITAT Citation2009). One could argue that the real ‘City’ then, exists only in the other 20%, which excludes even those Tanzanians who are relatively well off but due to the quite profound failure of the planning and housing systems are unable to get housing in these parts of Dar es Salaam. If even those who have some financial power are not able to force change in the system quickly, it highlights deep institutional limitations.

7.3 Human capital

7.3.1. Education

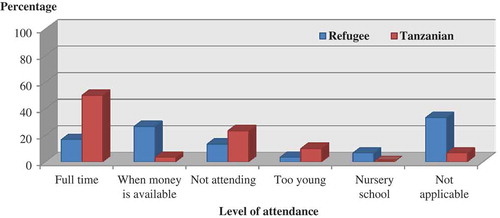

Human capital is a vital part of the assets portfolio of vulnerable groups for one reason in particular – it is required to make use of all other types of assets ([DFID] Department for International Development Citation1999). The development of human capital amongst the urban refugee population is restricted due to several reasons: first the education system in Tanzania, while technically free throughout primary school, in reality places a considerable financial burden on households through daily ‘contributions’. These are payments which can be required for anything from sitting an exam to providing school security, ranging from a few hundred TZS to several thousand TZS per day. This immediately presents a barrier to some children attending primary school fulltime. In addition, should students fail their final exams in primary school (Standard 7), they will not be allowed to proceed to public secondary level education (All Africa Citation2015). If children are lucky enough to pass exams and attend a public secondary school, the location of the school is decided by the Government, and is often considerably distanced from their home settlement, which incurs further burdens of cost and time spent travelling.

It is evident from the research conducted that removing children from school (see ) is often adopted as a coping mechanism when income streams decline or are temporarily stopped. In this instance, the children’s human capital is being traded off for financial capital (Parizeau Citation2015), to their detriment in the longer term. However, it is not so clear cut a choice, as indicated by one refugee, stating she could afford to feed her children or send them to school but not both.

There are several reasons for the poor level of attendance at school and these include, as attested to by Arun et al. (Citation2013) and supported by this research, expenses towards book and uniforms, distance to school, cost of transport, lack of awareness amongst parents and concurrently the lack of role models to demonstrate the benefits from education. In the case of refugee children, school registration was an added difficulty as without official refugee status and a permit to reside in the city they were not permitted to attend school in Dar es Salaam. Therefore, those that do register children mostly do so by pretending that they are Tanzanian citizens. This is a stark example of how they have no Right to the City – once again refugees are forced to adapt to fit the requirements of institutions which they lack the political capital to change.

From the current school attendance of the refugee children one can suppose that they will achieve a lower educational attainment than the Tanzanian group if they continue with this level of attendance. This phenomenon is also evidence of the erosion of assets that their parents had accumulated through their own education in their respective countries of origin (see ). From the data collected, it appears unlikely that the children of refugees will achieve the level of education that many of their parents possess. Social mobility through inter-generational asset accumulation is decisively hampered due to the displacement of the populations from their home areas. This is supported by Moser (Citation1998) whose research indicates that households who chose to keep children in school were financially more limited but in the long term less vulnerable as they reduced their vulnerability through the accumulation of human capital.

Table 2. Education level of respondents.

In addition, the relationship between education level, type of employment and income level of the refugee population all demonstrate that in spite of the human capital assets which they possess, their lack of political capital and rights in Tanzania mean that the potential of many of these assets are not realised, and many are forced to work in very low paying, precarious jobs for which they are over-qualified.

7.3.2. Education and the nexus linkages

The nexus linkages between education, asset vulnerability and the Right to the City are evident in several forms, as is the effect of displacement on increasing this vulnerability. At the macro level the state has imposed education policies which by their very nature will exclude the majority of the urban poor population, either through exam failure, cost or distance to schools. These policies are denying children access to the Right to the City, as they remain excluded from gaining assets which allow them to actively participate in the formal sector. Their exclusion to the slums is further compounded in the case of refugees by their displacement. Many refugees are not even allowed the opportunity to begin the very difficult process of completing their education because of registration difficulties and are forced to resort to forms of deceit which also leave them vulnerable to prosecution and deportation if their true identities are uncovered.

This is an enormous risk for a family to bear just for their children to receive a basic standard of education. In addition, the negative feedback loop (see ) in the case of schooling is clear to see in the informal settlements: thousands of disaffected, unemployed youths who have little hope of escaping from poverty and in some cases will turn to crime, thereby ensuring the perpetuation of the slums. The incoherent educational policy of the state actively reinforces many of the reasons why the informal settlements continue to exist, rather than alleviates them. The examination and location systems currently in place for schools need to be re-examined in order to accommodate the many students who will never finish school if the system remains the way it is.

7.3.3. Health issues (vulnerabilities of human capital)

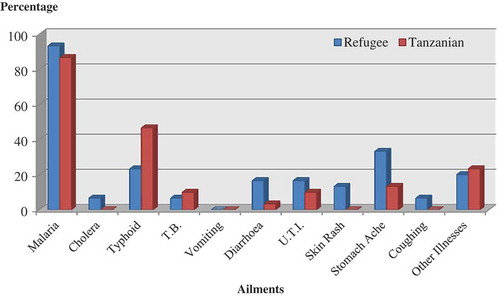

During interviews, all refugees reported suffering from at least one health problem (see ). The literature on livelihoods acknowledges that ill-health and health-related expenses are the primary cause of descending into poverty (Moser Citation2007). Malaria is clearly one of the most serious concerns; 93.3% of the refugees interviewed having contracted the disease at some point along with 86.6% of the Tanzanian group. However, other significant issues present included urinary tract infections, typhoid and stomach aches which can all be attributed to unsanitary living conditions and lack of access to clean water.

Tanzania currently has a health system where both public and private hospitals are available; however, one needs to be a Tanzanian national in order to access public health centres at a low cost; if you are found to be foreigner you may be ‘charged double or triple’ the price of citizens. The Household Budget Survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics in 2007 indicated that 74.9% of the population of Dar es Salaam lived less than 2 km from the nearest dispensary/health centre, and 17.9% lived less than 2 km from the nearest hospital (NBS Citation2009, p. 32). As Chambers (Citation1995) notes, the importance of a strong, healthy body is underestimated by those in developed countries who often rely more on their brains than bodies to generate income, but sickness or disability greatly hamper the ability of low-income people to develop sustainable livelihoods (Moser Citation2007; Helberg et al. Citation2015), and so this is a crucial asset for both populations to possess.

As also indicates, the refugee interviewees appear slightly less susceptible to illness than their Tanzanian counterparts in the findings, for example in the instance of contracting T.B. and typhoid. The causes for this are unknown; however, reasons could be due to the small sample size in this instance or misdiagnosis.

7.3.4. Health and the nexus linkages

Health is a key asset to the urban poor as without it, the development of a robust asset portfolio is considerably more difficult. As the majority of both the Tanzanians and refugees rely on their labour as their primary source of income, the loss of this due to poor health can have a devastating effect on the financial affairs of the household. The links between this asset vulnerability at the household level, and those at the macro level of the city institutions are clear: the urban environment due to lack of sufficient planning on the part of the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlement Developments has fostered a breeding ground for mosquitos which will not be easily removed. The inability of the state organisations to adequately address flooding in the informal settlement areas means that the rate of malaria infection will continue to remain high for the foreseeable future. Both groups are denied their Right to the City in different forms here: in the case of Tanzanians, while they elect local councillors to address issues, their power is restricted by an apathetic government, as they discuss councillors before elections:

They will come and promise us – I am going to improve the infrastructure, good roads, good streams, and everything but they didn’t do anything. That is the issue for a long time ago.

For refugees, their status restricts them on a daily basis and requires them to conceal their true identities – their existence in the city is almost always incognito. Therefore, their accessing of health services is not exercising their Right to the City, but co-opting the right of Tanzanians for their own benefit as a coping mechanism strategy.

A National Malaria Strategic Plan 2014–2020 has been adopted by the Government with optimistic projections for large reductions during the period of the programmes. The results of this endeavour will take several years to be properly evaluated. In addition, the distance to and cost of hospitals remains prohibitive for a significant proportion of residents, who will forgo treatment as a coping mechanism during times of financial hardship. Coupled with this, the lack of sufficient nutrition for those on lower incomes serves to increase the negative feedback loop at the household level, causing further illnesses and perpetuation the cycle for poor health.

7.4. Social capital

7.4.1. Conceptualising social capital

Social capital, often cited as an ‘intangible asset’ (Moser Citation2007, p. 30), requires clarification in order to discuss the various assets which people may accumulate through the course of their life cycle. Moser (Citation1998 p. 4) defines social capital as ‘reciprocity within communities and between households based on trust deriving from social ties’. It is a key asset to low-income groups (Mitlin Citation2003; Jacobsen Citation2006), in particular vulnerable groups such as urban refugees where increased security from support networks may at least partly offset having less access to financial capital.

The refugees interviewed for this research had received no counselling, and the toll of being forced to begin their lives again in a foreign country was extremely challenging. Having a support network of some sort available could be of great benefit in such instances, in particular for those refugees who were facing occurrences of xenophobia and racism in Dar es Salaam. It is important to note that in other studies such as Arun et al. (Citation2013), social capital in the form of networks was the most important form of asset to emerge from the research findings. Social capital is also important because as Conway et al. (Citation2002) notes without some form of community organisation and social mobilisation, the poor will most likely neither have rights or be able to realise them through their interactions with the government or other institutions.

7.4.2. Social capital and vulnerabilities

The results indicate that 43.3% of the refugees in the study did not know anyone on arrival in the city. In addition, due to the illegal status of many of the group, some chose purposely not to expand their networks too widely, in case of trouble with the authorities (see quote below). However, 66.6% stated that everyone in their area knew that they were a refugee, some explaining that their accent and dialect of Swahili made it impossible to avoid detection. Thirty per cent reported experiencing problems with their neighbours, ranging from racist comments to being forced to sell their goods in another settlement as all of the neighbours refused to buy anything from them. One of the refugees described how they tried to reduce contact in order to avoid detection:

So I’m really fearful of totally integrating with or getting used to them because if I start with my Swahili, I don’t have good Swahili, they would identify who I am. So my friends come from the church in [Location 1], and my ethnicity.

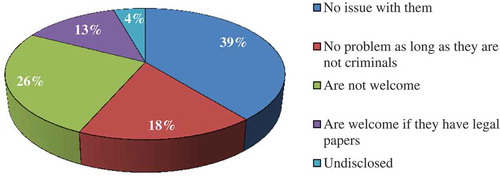

On discussing the topic of refugees with the Tanzanian group, it is interesting to note that only 26% (see ) stated categorically that refugees were not welcome in the city, which counters some of the experiences of the refugee population themselves. What this finding suggests is that there is a genuine willingness and a well of social capital on the part of a large proportion of the Tanzanian population to welcome refugees, and exploiting this capital will be crucial to the development of coherent refugee policies and programmes in the future. The fact the most Tanzanians claim to have no problem with refugees suggest that with the help of well-developed programmes through participation with the local communities, refugees could be integrated with the indigenous population.

Arguably, the most pertinent point to emerge from the Tanzanian interviews was the importance the group placed on official refugee status – if a refugee had received this status they were considered in a more favourable light than those who may have been just as entitled to refugee status but for whatever reason had never secured it. The conferring of this, albeit limited, ‘right’ by a known institution appeared to have a profound effect on the Tanzanian’s view of refugees – that by securing refugee status they had been vetted and legitimised in some way and therefore were likely to be less dangerous and more deserving of living in Dar es Salaam.

7.4.3. Stigma, discrimination and conflict (vulnerabilities of social and human capital)

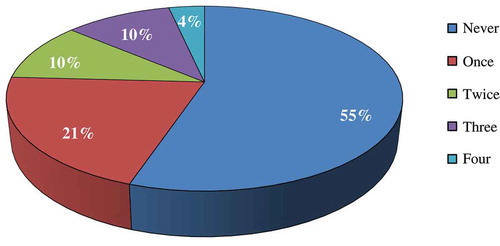

Discrimination and prejudice against urban refugees is widespread in the Global South (Pantaulino et al. Citation2012) and one of the main reasons that these populations go to such extremes to hide their true identities in urban space. Many of the respondents reported repeated incidents with police during which they were arrested () and were kept incarcerated until they paid substantial bribes (usually between 50,000TZH and 150,000TZH/$22.81USD and $68.42USD), often to have the process repeated several weeks later. This is important as the example of how public officials treat migrants, forced or otherwise will have a great impact on either fostering inclusion (Balbo Citation2013) or increasing alterity. Several had also experienced conflict associated with their living arrangements (either through arguments with neighbours or landlords). A refugee described how, when waiting in line to take her turn drawing water at a local well she often faced discrimination, and was reminded that she had no right to be there:

They will tell you ‘step aside you are a refugee. We need citizens to get the water first – sometimes they can just be rude at you because you are just a refugee, so you step aside.

7.4.4. Social capital and the nexus linkages

At the micro level of assets as shown in and in the example above, the Tanzanian group have a small advantage in that they are citizens, and so feel free to exercise their rights above those they deem to be outside this category. However, at the macro scale of the overarching Right to the City, as the example indicates, both groups should have access to running tap water in their homes, and yet neither do.

The lack of legal status of many refugees is also very unfortunate, as the results from the Tanzanians focus group indicate if forced migrants had legal refugee status they would for the most part not have a problem with them living in Dar es Salaam. By allowing urban refugees to legally live in the city, and educating the local population about their existence, it would undoubtedly reduce the level of discrimination against the refugees who currently are perceived to not have the right to be there.

The current situation is also unhelpful as it actively prevents proper integration of refugees into the urban sphere of Dar es Salaam – they are always wary of making friends with their Tanzanian neighbours and so this results in many lost opportunities for friendships and joint business ventures, in addition to a wider support network for the refugees which could provide assistance to them in times of hardship. This is evidenced by the fact that none of the Tanzanians interviewed stated they knew a refugee; however, it is quite possible that some of them in fact did know of one, but just were not aware because of refugees’ desire to remain inconspicuous.

7.5. Financial capital

7.5.1. Low-income work and precarious earnings (vulnerabilities of labour)

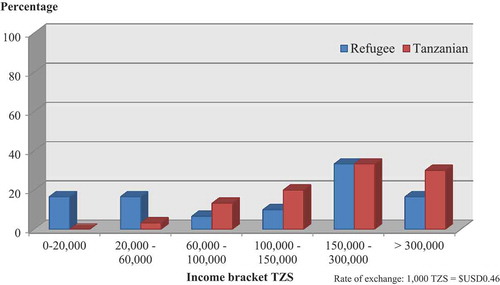

The urban refugees and Tanzanians interviewed for this research find work in the informal sector mostly as food sellers, statue carvers and hairdressers (). As can be seen in , the majority (N25/83.3%) of urban refugees survive on less than 300,000TZS/$136.85USD per month.

Table 3. Distribution by main occupation.

One-third of the group survive on less than 60,000TZS/$27.37USD) and are in some cases the only breadwinner in the family. This can be attributed to both their status preventing them from taking positions in the formal sector, and also in some cases due to lack of education and skills (please see Section 7.3.1 for further discussion on education). What is most significant in the case of income level is that the Tanzanian inhabitants of informal settlements are also poor by Tanzanian standards – the latest Tanzanian census conducted in 2012 states that the average monthly cash earnings for private sector workers is 307,026TZS, while for the private sector it is 671,639TZS (NBS Citation2013a, p. 38).

Informal work is very inconsistent and so the figures shown are an average for what the two groups most likely earned in the course of a month; it is not a given that they always earn this amount. Variations in income depended on several factors from health – there is no sick pay in the informal sector – to the weather, as Dar es Salaam is subject to severe flooding, which exacerbates the vulnerability of low-income populations (see Kabisch et al. Citation2015) and makes the city notoriously difficult to navigate during the rainy season, hampering effort to sell goods on stalls or gain access to local markets. This can limit the income generating activities of the groups in several ways: as some sell produce from their homes, if they are affected by flooding this will affect their level of customers. In addition, traveling to other areas of the city to markets to sell their goods will take longer due to traffic delays and possibly cost more as travel will have to be via motorbike or Bajaj rather than Dala dala minibuses, both of which are more expensive. Due to the space constraints, this issue is not addressed in more depth in this paper, but for a more detailed discussion, see Kabisch et al. Citation2015).

7.5.2. Financial capital and the nexus linkages

In this instance, both groups are vulnerable and unable to exercise their Right to the City for several reasons: in the case of refugees they do not have the right to work in Tanzania and so cannot exploit to their full potential any skills or qualifications they may possess and are limited to informal work. In the case of the Tanzanian group, failure in several areas on the part of the state has led to their predicament: the failure to formalise large parts of the economy to afford workers basic protection in terms of minimum wage and regular working hours, and provision of drainage services throughout the city to cope in times of flooding. This is also compounded by the level of education which many Tanzanians receive which is not sufficient for them to access well-paid stable jobs. The vulnerabilities at this household level have considerable knock on effects for Dar es Salaam as a city at the macro level. First, the existence of such a large informal economy results in not just poor regulation and registration of businesses, but a huge missed opportunity for the state in claiming unpaid taxes by all these businesses. These uncollected taxes could be put to good use in developing the infrastructure of the city and providing the much needed services both groups need. The government has made some headway with this, through its MKURABITA (Property and Business Formalisation Programme), the aim of which is to formalise properties and businesses in Tanzania; however, more development is needed in this area.

Having a large proportion of the workforce in the situation where they are living at a subsistence level or just above will also inevitably lead to greater crime and corruption as people seek to supplement their income in whatever manner they can. In this case, the linkages between displacement, vulnerability and the Right to the city become apparent – refugees are more disadvantaged than their Tanzanian counterparts for the reasons outlined above, all of which are directly related to their status as an outsider. They fact that they do not legally have a right to reside in the city almost negates many of the positive attributes they possess which should normally lessen their level of vulnerability, such as education. Their exclusion from access to this right is validated at the state level, but has the negative feedback loop of not just affecting them, but also their Tanzanian counterparts negatively by increasing both competition and animosity between the two groups.

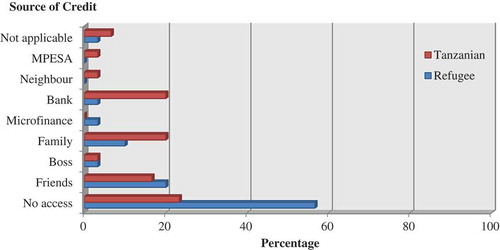

7.5.3. Access to credit

The research conducted indicates that urban refugees have very limited access to any type of formal financial institutions from national banks to small-scale microfinance groups (see ). For example, only 20% of the refugees interviewed had a bank account, in comparison to 40% of their Tanzanian counterparts. In addition, 60% of the refugee population stated that they were unable to save any money, in comparison to 36.6% of the Tanzanian cohort. Low-income groups are notoriously risk averse and generally view access to credit as a risk rather an opportunity and so the ability to save is of particular importance to these groups.

The inability of the vast majority of the refugee population to access any form of savings and credit, formal or otherwise, places them in a very perilous state. As for the most part they rely solely on their labour to generate income, any disruption to this source such as sickness can result in the refugees becoming destitute very quickly as they have no or a very limited support network to assist them through the crisis.

This lack of ability to save coupled with very limited access to credit makes refugees considerably more vulnerable in terms of financial assets overall in comparison to their Tanzanian counterparts. In addition to increasing their vulnerability, it also hampers any efforts they make towards building capital for business ideas or job creation, as they are often living day to day. The nexus linkages between asset vulnerability, displacement and the Right to the City are also clear in the case of financial capital: both groups are denied access to ‘the City’ institutions by virtue of being too poor, but refugees are considerably more disadvantaged overall for the reasons outlined above.

When considering an overview of the five major assets as outlined by Moser, having such a weak financial portfolio as many of the refugees leaves them open to serious risk. This is supported at the macro level in Dar es Salaam with strict criteria regarding the opening of bank accounts that require identification and other documents which many refugees do not have.

7.6. Refugee status

7.6.1. Legal status

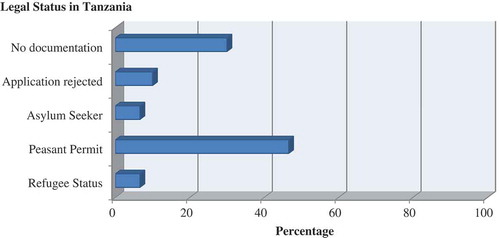

Arguably, the most basic of rights is the right to existence itself, and it is one that is currently being denied to the urban refugees, at least within the confines of the legal context and the cityscape. As Smith and Jenkins question, should the right to the city (under certain circumstances) primarily be a right to inhabit the city? (Citation2013, p. 141). Is this demand of the urban refugee populations in recent years just the latest in ‘the strong legacy of control of urban residency rights induced by colonialism, which is found throughout Sub-Saharan Africa?’ (Citation2013, p. 141). It is an important question because as can be seen from , while almost 47% of the refugees interviewed had acquired peasant permits,Footnote7 the remainder were in various states of precariousness regarding their refugee status, with 30% having no documentation of any kind.

The refugee group emphasised repeatedly how important the peasant permits were in making their day-to-day lives easier. Released from the constant fear of arrest or deportation, they were allowed some stability to begin to rebuild their lives.

It is not just the lack of political capital available to the refugees what increases their difficulty, but also the lack of powerful organisations championing their issues on their behalf. Although AATZ provides free legal aid to refugees in Dar es Salaam and has been of great help as attested to by the interviewees, UNHCR appears less concerned with the undocumented urban displaced. While there had been some attempts to draft an urban refugee policy to submit to the MHA (as confirmed by interviews conducted with UNHCR, TCRS and AATZ), since the development of the Burundian crisis in Western Tanzania UNHCR appears to have shifted its properties elsewhere.

8. Conclusion

The livelihood strategies adopted by the urban refugee population of Dar es Salaam acknowledges the complexities of managing complex asset portfolios, but their choices are limited in comparison to their Tanzanian counterparts, who are themselves quite vulnerable. Refugees’ ability to accumulate the five main assets as noted by Moser (Citation1998) is seriously curtailed by their lack of another asset: political capital, and as Chambers and Conway (Citation1991) notes, their lack of rights means that the assets they do have such as labour and education can, and indeed are, being significantly eroded, while those assets which they aspire to accumulate (such as housing) will likely never be realised due to Government policies which do not recognise them as having any Right to the City.

The insecurity of their lives and their dependence on often one single asset, their labour, to survive means than any shocks or negative occurrences has an extremely adverse effect on their ability to survive let alone prosper. Their vulnerability is deep seated and inter-generational, as their lack of political capital is often passed on to their children, who will also be excluded from accessing many of the rights of their Tanzanian counterparts. provides a summary of their challenges and coping strategies as a group. The important linkages to emerge from this research are the connection between the different levels of power: how the development of a framework of rights at the state level can have an impact on the asset vulnerability at household level and vice versa. Legitimising the existence of the urban refugee population in the city is the first step required to allow them to begin reducing their vulnerability. Without the regularising of their status, it will be extremely difficult for refugees to develop any of the other main assets discussed. Findings also indicate the potential for income generation and the salutary contribution refugees could make to the economy of the city. The human capital assets of the group are being vastly underutilised, and with the implementation of effective policies the skills, education and experience which the refugees possess could not only create sustainable livelihoods for them, but also be of benefit to their Tanzania hosts for the foreseeable future.

Table 4. Summary table of challenges and coping strategies of urban refugees

This paper also highlights how the asset vulnerability framework, viewed through a Right to the City lens is useful in providing further understanding for the both inductive and deductive nature of this type of research. Further research is required to fully understand the implications of the linkages between these concepts. The small sample size and qualitative nature of this study are limiting, and larger scale quantitative surveys on urban populations will be required to gain a deeper more nuanced insight into their asset vulnerabilities. However, the potential to explore this nexus further, particularly in light of its ability to consider the theory of the Right to the City from a different perspective is considerable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aisling O'Loghlen

Miss Aisling O'Loghlen, Ph.D. Researcher in Urban Studies in the Department of EGIS, Heriot-Watt University. Research interests include urban displacement, forced migration and development planning.

Chris McWilliams

Dr Chris McWilliams, Lecturer in Urban Studies in the Department of EGIS, Heriot Watt University. Research and teaching interests include critical urban theory, state responses to contemporary restructuring and urban problems/policies in contemporary society.

Notes

1. In this study, the term ‘refugee’ is used not only for people with official refugee status, but asylum seekers who are still waiting for their refugee status determination, and unregistered forced migrants, who live in refugee-like situations but have not applied for refugee status. Clear distinctions will be made between these legal categories when necessary throughout the text.

2. See [UN-HABITAT] United Nations Human Settlements Programme (Citation2006, pg 21) for comprehensive definition of the term slum as it is adopted for this paper.

3. For a detailed overview of the development of these concepts, see Lampis (Citation2009).

4. Vulnerability is defined here as ‘insecurity and sensitivity in the well-being of individuals, households and communities in the face of a changing environment, and implicit in this, their responsiveness and resilience to risks that they face during such negative changes’ (Moser Citation1998, p. 3).

5. Natural capital is defined here ‘as the sock of environmentally provide assets such as soil, atmosphere, forests minerals, water and wetlands’ (Moser Citation2007, p. 84). Natural capital will not be discussed independently of the other assets in this paper, but as an addition to the four other assets.

6. For the purposes of this paper, the concept of the Right to the City is defined based on the writings of Marcuse (Citation2014) and his strategic reading of Lefebvre’s (Citation1996) work which identifies with groups (such as identified by this research) which are the underprivileged and suffering in urban society, prohibited economically or socially from real inclusion in the City. They are simply seeking ‘to obtain the benefits of existing city life from which they have been excluded’ (Marcuse Citation2014, p. 6). More in-depth discussion on this point can be found in Section 6 of this paper.

7. Applicants who can apply for a peasant permit is a defined by the Government of Tanzania Department of Immigration as ‘Persons who have resided for a long time in the country as peasants, pastoralist and other legally recognised small scale activities’ (Department of Immigration Citation2016). This permit was available to Congolese nationals only, and was used by agricultural workers crossing the border between Tanzania and DRC regularly. However, some Congolese refugees also received peasant permits while in Dar es Salaam. Currently, these permits are under review by the Government.

References

- All Africa. 2015. Tanzania: Tuition in Private Schools ‘Unaffordable’; [cited 2016 Mar 2]. Available from: http://allafrica.com/stories/201512212817.html

- Arun S, Annim SK, Arun T. 2013. Overcoming household shocks: do asset-accumulation strategies matter? Rev Soc Econ. 71:281–305.

- [AATZ] Asylum Access Tanzania. 2011. No place called home—a report on urban refugees living in Dar es Salaam. Dar es Salaam: Asylum Access.

- Balbao M. 2013. Cities with migrants: rights and fears. In: Boniburini I, Le Marie J, Moretto L, Smith H, editors. The city as a common good: urban planning and the right to the city. Brussels: La Cambre Horte; p. 84–100.

- Boniburini I. 2013. As a way of introduction the “right to the city”: practices and imaginaries for rethinking the city. In: Boniburini I, Le Marie J, Moretto L, Smith H, editors. The city as a common good: urban planning and the right to the city. Brussels: La Cambre Horte; p. 14–43.

- [BBC] British Broadcasting Corporation News. Burundi President Pierre Nkurunziza sworn in for third term. 2015; [cited 2016 Feb 16]. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-34000420

- Bryman A. 2012. Social research methods. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell EH. 2006. Livelihoods in the region: Congolese refugee livelihoods in Nairobi and the prospects of legal, local integration. Refugee Surv Q. 25:93–108.

- Chambers R. 1995. Poverty and livelihoods: whose reality counts? Environ Urban. 7:173–204.

- Chambers R, Conway G 1991. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. Discussion Paper 296. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies.

- Chiasson S 2015. The State of Freedom of Movement for Refugees in Tanzania: An Overview; [cited 2016 Feb 2]. Available from: http://rightsinexile.tumblr.com/post/128143318377/the-state-of-freedom-of-movement-for-refugees-in

- Conway T, Moser C, Norton A, Farrington J. 2002. Rights and livelihoods approaches: exploring policy dimensions. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Crawford N, Cosgrave J, Haysom S, Walicki N. 2015. Protracted displacement uncertain pats to self-reliance in exile. London: Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute.

- Crisp J. 2010. Forced displacement in Africa: dimensions, difficulties, and policy directions. Refugee Surv Q. 29:1–27.

- Crisp J, Jacobsen K. 1998. Refugee camps reconsidered. Forced Migr Rev. 3:27–30.

- Crisp J, Morris T, Refstie H. 2012. Displacement in urban areas: new challenges, new partnerships. Disasters. 36:S23–S42.

- [DFID] Department for International Development. 1999. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheet. London: Department for International Development.

- Department of Immigration. 2016. Residence Permits Class A; [cited 2015 Sep 4]. Available from: http://www.immigration.go.tz/module1.php?id=45

- De Vriese M. 2006. Refugee livelihoods: a review of the evidence. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- Edwards A. 2010. “Legitimate” protection spaces: UNHCR’s 2009 policy. Forced Migr Rev. 35:48–49.

- [EMOT] Ezra Ministries of Tanzania, Refugee Self- Reliance Initiative. 2008. Report on the survey of urban refugee population in Dar es Salaam. Dar es Salaam: Ezra Ministries of Tanzania.

- Harvey D. 2008. The right to the city. New Left Rev. 53:23–40.

- Haysom S. 2013. Sanctuary in the city? Urban displacement and vulnerability, final report. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Heltberg R, Oviedo AM, Talukdar F. 2015. What do household surveys really tell us about risk, shocks, and risk management in the developing world?. J Dev Stud. 51: 209–225.

- Jacobsen K. 2002. Can refugees benefit the state? Refugee resources and African state building. J Mod Afr Stud. 40:577–596.

- Jacobsen K. 2006. Refugees and asylum seekers in urban areas: a livelihoods perspective. J Refug Stud. 19:273–286.

- Kabisch S, Jean-Baptiste N, John R, Kombe WJ. 2015. Assessing social vulnerability of households and communities in flood prone urban areas. In: Pauleit S, Coly A, Fohlmeister S, Gasparini P, Jørgensen G, Kabisch S, Kombe WJ, Lindley S, Simonis I, Yeshitela K, editors. Urban vulnerability and climate change in Africa; [cited 2016 Mar 15]; p. 197–228. Available from http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-03982-4_6

- Kibreab G. 2007. Why governments prefer spatially segregated settlement sites for urban refugees. Refuge. 24:27–35.

- Kombe WJ 2010. Land conflict in Dar es Salaam: who gains? Who loses? Crisis State Working Paper Series 2. London: London School of Economics.

- Lampis A 2009. Vulnerability and Poverty: An assets, resources and capabilities impact study of low-income groups in Bogota [dissertation]. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Lefebvre H. 1996. The right to the city. In: Kofman E, Lebas E, editors. Writings on cities. London: Blackwell; p. 63–184.

- Maria Pinto G, Attwood J, Birkeland N, Solheim Nordbeck H. 2014. Exploring the links between displacement, vulnerability, resilience. Procedia Econ Finance. 18:849–856.

- Marcuse P. 2009. From critical urban theory to the right to the city. City. 13:185–197.

- Marcuse P. 2014. Reading the right to the city. City. 18:4–9.

- Metcalfe V, Pavanelloa S, Prafulla M. 2011. Sanctuary in the city? Urban displacement and vulnerability in Nairobi. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Milner J. 2009. Refugees, the state and the politics of asylum in Africa. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mitlin D. 2003. Addressing urban poverty through strengthening assets. Habitat Int. 27:393–406.

- Moser C. 1998. The asset vulnerability framework: reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Dev. 26:1–19.

- Moser C, Dani A, editors. 2008. Assets, livelihoods and social policy. Washington (DC): World Bank.

- Moser C. 2006. Asset-based approaches to poverty reduction in a globalized context: an introduction to asset accumulation policy and summary of workshop findings. Washington (DC): The Brookings Institution.

- Moser C, editor. 2007. Reducing global poverty: The case for asset accumulation. Washington (DC): The Brookings Institution.

- Moser C, Norton A. 2001. To claim our rights: livelihood security, human rights and sustainable development. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Morris T, Ben Ali S 2015. UNHCR Reviews it Policy: an Air of Complacency? [Internet]; [cited 2015 June 6]. Available from: http://urban-refugees.org/debate/unhcr-reviews-urban-policy-air-complacency/

- [NBS] National Bureau of Statistics. 2009. Household Budget Survey main report 2007. Dar es Salaam: National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance, Government of Tanzania.

- [NBS] National Bureau of Statistics. 2013a. Employment and Earnings Survey 2012 analytical report, mainland Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance, Government of Tanzania.

- [NBS] National Bureau of Statistics. 2013b. 2012 Population and Housing Census. Dar es Salaam: National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance, Government of Tanzania.

- Omata N 2012. Refugee livelihoods and the private sector: Ugandan case study. Working Paper Series No. 86. University of Oxford: Refugee Studies Centre.

- Oxfam. About the Rights in Crisis campaign c. Oxford: Oxfam. 2015; [cited 2016 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.oxfam.org/en/rights-in-crisis/about

- Pantuliano S, Metcalfe V, Haysom S, Davey E. 2012. Urban vulnerability and displacement: a review of current issues. Disasters. 36:S1–S22.

- Parizeau K. 2015. When assets are vulnerabilities: an assessment of informal recyclers’ livelihood strategies in Buenos Aires, Argentina. World Dev. 67:161–173.

- Parsa A, Nakendo F, Mccluskey WJ, Page MW. 2011. Impact of formalisation of property rights in informal settlements: Evidence from Dar es Salaam city. Land Use Policy. 28:695–705.

- Pavanello S, Elhawary S, Pantuliano S. 2010. Hidden and exposed: urban refugees in Nairobi, Kenya. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Purcell M. 2013. Possible worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the right to the City. J Urban Aff. 36:141–154.

- Rakodi C, Lloyd Jones T, editors. 2002. Urban livelihoods a people centre approach to reducing poverty. London: Earthscan.

- Sen A. 1981. Poverty and famines: an essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith H, Jenkins P. 2013. Urban land access in Sub-Saharan Africa: the right to the city in post-war Angola. In: Boniburini I, Le Marie J, Moretto L, Smith H, editors. The city as a common good: urban planning and the right to the city. Brussels: La Cambre Horte; p. 139–157.

- [UN-HABITAT] United Nations Human Settlements Programme. 2010. Citywide action plan for upgrading unplanned and unserviced settlements in Dar es Salaam. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- [UN-HABITAT] United Nations Human Settlements Programme. 2009. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam city profile. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- [UN-HABITAT] United Nations Human Settlements Programme. 2006. State of the World’s Cities 2006/2007. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- [UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 1997a. Refugees Magazine Issue 110 (Crisis in the Great Lakes) - Cover Story: Heart of Darkness [Internet]; [cited 2015 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/3b6925384.html

- [UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 1997b. UNHCR policy on urban refugees. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- [UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2009a. UNHCR policy on refugee protection and solutions in urban areas. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- [UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2009b. UNHCR policy on alternative to camps. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- [UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2011. Promoting livelihoods and self—reliance operational guidance on refugee protection and solutions in urban areas. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- [UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2012. The implementation of UNHCR’s policy on refugee protection and solutions in Urban Areas Global Survey—2012. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- [UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2015a. Burundi Situation – Displacement of Burundians into neighboring countries; [cited 2015 Jul 12]. Available from: http://data.unhcr.org/burundi/download.php?id=199

- [UNHCR] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2015b. UNHCR battles cholera at world’s largest refugee complex; [cited 2016 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/5685137c9.html