Abstract

This article concerns the nature of landlordism and landlord–tenant relations in Kenya’s smaller towns and cities and takes as its case studies Kisumu and Kitale. There is a pressing need to understand the variable ways in which rental tenure is produced in low-income areas and the interaction between inequality and the private provision of housing. This article contends that rental tenure has a long and complex history in Kenyan cities and remains the dominant mode of housing production in low-income areas. The article critically examines the ways in which different forms of landlordism, such as absentee landlordism, have different connotations when applied to smaller Kenyan town and cities. Moreover, the article analyses the symbiotic relationship between landlords and tenants, particularly regarding tensions surrounding the extraction of rent. Lastly, the wider socio-spatial significance of landlordism is discussed through an examination of the significance of life-quality differences between landlords/tenants.

1. Introduction

According to a wide-reaching report produced for the UN-Habitat most national governments across the globe (in the preceding 30 years at least) have encouraged private property ownership at the expense of rental tenure (UN-Habitat Citation2003). The result is that most national government housing policies simply do not mention or neglect rental accommodation as a viable housing option when it is, in fact, a lived reality for many people across the planet. They also quote themselves to suggest that ‘almost nothing is known about those who provide rental accommodation’ (2003, p. 1).

This article aims to contribute towards this gap in knowledge by reasserting the importance of landlordism in the low-income settlements of Kenya’s smaller towns and cities. There is a growing body of research concerned with rental tenure in Nairobi’s low-income settlements (Amis Citation1984; Otiso Citation2003; Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008; Hendriks Citation2008; Huchzermeyer Citation2008; Rigon Citation2014), however, comparative research in other Kenyan cities is lacking. Research in Nairobi has documented the different categorical forms of landlordism such as ‘absentee landlords’ (Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008) and that renting remains profitable despite the absence of widespread housing improvements (Amis Citation1984; Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008).

This research builds upon the political economy analysis of low-income landlordism developed by Kumar (Citation1996) through a focus on the wider social relations in which landlordism is produced. Such a perspective provides insights into the diverse forms that landlordism takes, the nature of landlord–tenants relations, and the implications of such relations for poorer tenants. This perspective develops through an analysis of the gender and familial dynamics of landlordism, the expanded role of landlords in economic development and the ways in which the ‘symbiotic relationship’ (Cadstedt Citation2010, p. 15) between landlords and tenants affects tenure security.

Following the methodology, the article starts by giving a brief historical trajectory of low-income landlordism in Kenya. Literature concerning low-income landlordism will then be discussed including Kumar’s (Citation1996) pretty commodity production model. The first results section contends that production of landlordism is not only determined by the motivations of landlords but also relies on the composition of landlord families and ways in which property is acquired. This is highlighted through the examination of the different forms that landlordism takes revealing a much expanded concept of ‘absentee landlordism’. This arises from an analysis of gender dynamics within landlord families. Life-quality comparisons between tenants and landlords are then presented to examine social differentiations between landlords and tenants and how such differentiations influence landlord–tenant relations. The final section discusses the effects of such differentiations upon the lived reality of tenure security. The article concludes by discussing the policy implications of these findings.

2. Methodology

Kisumu is the 3rd largest city in Kenya with a population of 409,928, while Kitale is the 18th largest town with a population of 106,187 (ROK Citation2010). UN-Habitat has previously identified six major low-income settlements across the city of Kisumu (UN-Habitat Citation2005), while approximately 65% of the population of Kitale lack access to decent shelter and safe water (Chege & Majale Citation2005). The dominant land use pattern in Kisumu’s low-income settlements is private residential tenure (predominantly rental) although the rate of officially documented land ownership ranges from 42% to 92.6% across different areas (Karanja Citation2010) .

Figure 1. Map of Kenya showing the location of Kisumu and Kitale in relation to Nairobi, the capital and largest city.

The general theme of this research was the relationship between land tenure and service delivery within the low-income settlements of Kenya’s smaller towns and cities. A key aim was to critically examine the nature of landlordism and landlord–tenant relations and the findings presented here refer predominantly to this subject. A questionnaire survey of 104 respondents was conducted in 2013 across five sample locations in Kisumu and Kitale. The questionnaire survey addressed five key themes, namely, background information, housing conditions, landlord–tenant relations, service use, and perceptions of service delivery. Life-history questions were posed to 64 respondents and qualitative interviews were also conducted with 28 respondents.

The survey approach was to target landlords and tenants for interview and, at certain points, landlords and tenants living on the same plot. The sample locations in Kisumu were; Manyatta A (29 interviews), Manyatta B (36), and Nyalenda (25), and in Kitale; Migosi and Grasslands, which, due to the small sample number of 14 interviews, have been grouped together under the heading ‘Kitale’. The sampling strategy was non-random as initial interview locations were chosen in discussion with research assistants who lived at the respective sample sites. Further respondents were gathered through their geographical proximity to, or by association with, the previous interview. As such, a broad cross-profile of both landlords and tenants were interviewed, however, decisions were also made to target large/small landlords at certain points when it became clear that more respondents in either categories had been interviewed.

As such, the findings presented may not be fully representative of the sample locations as the sampling strategy was non-random and, at times, targeted. The gender balance of respondents is also not fully representative partly because most interviews were conducted during the day (due to practical and logistical reasons) when more women were available for interview.

3. History of low-income landlordism in Kenyan cities

The following section gives a brief historical overview of low-income landlordism in Kenya and its relation to wider urban development. Low-income landlordism had developed in Kenyan cities as early as 1913 (van Zwanenberg Citation1972). This history is a shared history with Kenyan urbanisation more generally. The colonial system created increased labour demands while simultaneously failed to provide widespread public housing. This was expressed in a constant tension between employers and colonial authorities over housing the African population (Hay & Harris Citation2007) and also saw the emergence of landlordism both within the European ‘excluded’ zones (in various quasi-public and private guises) and the surrounding areas in which Africans were permitted (or in many cases reluctantly accepted) to live.

For example, the Nairobi Sanitary Commission report of 1913 states that ‘those up-country natives who are not provided with quarters within the compound of their employers, have been forced to rent miserable quarters in insanitary localities of the town and at excess rates’ (quoted in van Zwanenberg Citation1972, p. 25). As van Zwanenberg continues to highlight ‘many of the poorest Africans obtained their housing from so-called “lodging housekeepers”. These paid rent to the municipality of 5/. a month for their homes, of which they proceeded to rent rooms, verandahs and any other available covered space for sleeping’ (Citation1972, p. 27). As early as the 1910s and 1920s colonial authorities implicitly accepted the emergence of landlordism among the African population both within and outside colonial areas (even though legal land rights were absent). Moreover, much of this housing comprised rudimentary one room dwellings – a trend continuing in Kenya today (Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008).

The emergence of landlordism fed into the racist colonial system which meant that ‘from the beginning the so-called races – “Europeans”, “Asians”, and “Africans” – lived separate lives from each other’ (van Zwanenberg Citation1972, p. 17). As van Zwanenberg also asserts ‘within each racial division, however the market was free to segregate rich and poor as in Western cities’ (pp. 17). This separation was achieved through exclusionary colonial laws and policies (such as prohibition on the ownership of land (Hay & Harris Citation2007)) and in many cases through brute force such as police night-raids. Crucially, wages among African labourers were typically too small to permit them to rent the little formal housing that did exist.

Ethnic distinctions have played an important role in the development of landlordism. For example, what is now known as Kibera was originally settled by Nubians of Sudanese origin who were permitted to live in the area by colonial authorities. As Amis details ‘the Nubians were able to profit from their privileged position within the colonial administration by beginning to construct additional rooms explicitly for rental purposes’ (Amis Citation1984, p. 89). This remains a prevailing characteristic of landlordism in Kenya today. Namely, many landlords are afforded the opportunity to buy or construct rental housing through their links with the ruling elite or employment within government institutions (Syagga et al. Citation2002).

The link between ethnicity and land possession in Kenya, however, is long and complex (Anderson Citation2005). What can be said in a cautionary sense is that the dictates of political patronage have produced a constantly shifting landscape of land dispossession and reallocation between different ethnic groups. Klopp (Citation2008) interprets this history through a concurrent discussion of slum demolitions. He contends that slum demolitions have often been a pretext for land grabbing and what he terms the ‘reprivatisation’ of land for commercial purposes (including landlordism) as in the case of Muoroto in Nairobi in 1990.

In the late and early postcolonial period, the urban population in Kenya continued to grow – as did the rate of rental tenure. By 1972, 50% of the total adult population of Kibera were tenants (Temple Citation1974). Temple conducted a large-scale survey among the population of Kibera and found that ‘rents are as important a source of income as employment’ (pp. 6). He also found that landlords generally lived in bigger houses with less crowding whereas tenants lived almost exclusively in one-room dwellings.

The development of landlordism in low-income settlements was fuelled by an increasing deficit in the provision of public housing. As Mwangi highlights ‘according to the 1976–1982 urban housing survey, average annual housing production was only 6,400 units per year’ (Citation1997, p. 143). He continues to mention that ‘by 1989, demand had risen to 65,800 units … in the nine years from 1986–1994, only 5,568 units were built’ (pp. 143). Low-income landlordism emerged to address this deficit while successive Kenyan administrations neglected rental tenure in policy and legislative terms (ibid.)

It would be wrong, however, to think that all low-income landlordism in Kenya was fuelled by rapid urban growth of predominantly squatters migrating to labour centres. Although this is a strong feature of the Nairobi case study (Amis Citation1984; Lee-Smith Citation1990), the picture in other Kenyan cities is more diverse. In Kisumu and Kitale the progressive outward expansion of the towns (Otiso & Owusu Citation2008) was met by a predominantly rural population of landholders (UN-Habitat Citation2005; Huchzermeyer Citation2009). Many of these landholders became landlords in what are now low-income areas. This process was not linear or consistent, however, in that some rural land parcels had already become subdivided through inheritance whereas others still maintained agricultural practices (Huchzermeyer Citation2009).

Nevertheless, by the 1980s fully commercial rental markets had developed in Nairobi’s low-income settlements (Amis Citation1984). Landlords and tenants in such markets came from diverse backgrounds and lived in divergent living conditions. As such, rental markets have produced a great deal of inequality among residents of so-called low-income settlements (ibid.). Contemporary research in Kenyan cities continues to point to the diversity of landlordism evident (Macoloo Citation1994; Mwangi Citation1997; Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008). In 2004, Gulyani and Talukdar (Citation2008) conducted a large-scale survey in Nairobi’s low-income settlements and found that while some landlords were highly commercial and ‘absentee’, others were extremely poor and rented only one-room dwellings to tenants.

4. Contemporary rental tenure and literature

Landlordism is a contemporary feature of low-income urban areas in Kenya. In a 2004 World Bank Survey conducted among 1,755 low-income households in Nairobi, it was estimated that 92% of residents were rent-paying tenants (Gulyani et al. Citation2012). An enumeration exercise carried out in one low-income settlement in Nairobi found the proportion of tenants to be 81% (Rigon Citation2014). Large-scale survey research in Kisumu has estimated the percentage of tenants across the city to be 69% (Karanja Citation2010) and estimates for similar sized cities such as Nakuru suggest a tenancy figure of 87% (Mwangi Citation1997).

The importance and implications of such findings have remained under-examined, however, due to a wider focus in some literature on the informal–formal binary, the fear of explosive urban growth (Hall & Pfeiffer Citation2000), and the valorisation of slum-dwellers/informal traders as self-realising entrepreneurs (de Soto 2000). As Lee-Smith has stipulated in relation to the Korogocho slum of Nairobi, ‘the image of the squatter as independent self-builder has tended to obscure the fact that this type of settlement usually has more tenants than owners’ ('Lee-Smith Citation1990, p. 176).

While such an obscuration has emerged as a by-product of academic research on ‘informality’, it must also be acknowledged that such views developed because of neo-liberal policy and discourse in the 1970s which ascribed ‘agency’ to slum-dwellers as a pretext for non-action or creating a favourable macroeconomic environment for the poor to realise this agency (Turner Citation1972; Hart Citation1973; de Soto Citation1989). Tenure relations such as landlordism did not necessarily feature heavily in such approaches – neither have they featured strongly in debates surrounding land tenure security and land titling (Payne et al. Citation2009).

The political imperative for shifting the focus to private rental tenure is emphasised by Davis who claims that ‘despite the enduring mythology of heroic squatters and free land, the urban poor are increasingly vassals of landlords and developers’ (Citation2007, p. 82). By reasserting the debate over landlordism, ‘the poor’ can be brought back into the arena of capitalist reproduction and not ideologically othered as the outside or excess of the city. Gilbert has stressed the failure of international institutions and national governments to consider rental housing as a serious part of housing policy. He argues that ‘most government housing programmes omit any mention of renting’ (Citation2008, p. ii). The direct result of this is the failure of tenants (and indeed landlords) to emerge as meaningful political actors (Gilbert Citation2008) and the partitioning of landlordism as ‘private’ matter due to the ‘absence of collective action among tenants’ (Cadstedt Citation2006, p. 182).

Various processes have been used to explain the emergence of landlordism in low-income areas including commercialisation of land previously held illegally or squatted upon (Aina Citation1990; Doshi Citation2013), site and service (or latterly slum-upgrading) schemes where housing is ‘poached’ for rent (Werlin Citation1999; Jones Citation2012; Rigon Citation2014) or population increases which produce a ‘race to the bottom’ to sell tiny spaces for relatively high amounts of rent (Archer Citation1992). As the previous section detailed, however, low-income landlordism has a much longer (and complex) history in Kenya and more commonplace is landlords who are long-term inhabitants of an area who have gradually come to rent out accommodation over an extended period (Aina Citation1990; Lee-Smith Citation1990; Cadstedt Citation2010).

Literature suggests that landlordism varies considerably across the globe (Gilbert Citation2003; Kumar Citation2011). Despite some accounts of exploitative ‘slumlords’ (Davies Citation2007) it appears that landlords in both rich and poor countries generally own few properties (Rakodi Citation1995) and may not necessarily be exploitative of tenants (UN-Habitat Citation2003). Research in Ghana has found that practices of advanced rent payment have emerged as a response to wider housing shortages – practices which simultaneously create tensions between landlords and tenants (Arku et al. Citation2012). In Tanzania, Cadstedt (Citation2010) has similarly found a lack of political imperative concerning rental tenure but landlord–tenant relations in Mwanza City are shaped by the mutual experience of poverty.

Some have contended that public discourses have led to the propagation of stereotypes which disregard the multiplicity of different landlord and tenant identities (Bierre et al. Citation2010.). Categorising landlordism is therefore problematic but attempts do so have often used distinctions ranging from ‘small’ landlords to ‘large property developers’ (Hoffman et al. Citation1991). As Kumar has contended, however, the ‘classification of landlords on the basis of the number of rooms let or the nature of the construction process is clearly of limited use’ (Citation1996, p. 324). Instead, Kumar (ibid.) has proposed a triadic conceptualisation of landlordism based on a Marxist framework of petty-commodity production.

The three categories Kumar forwards are ‘subsistence landlordism’, or landlordism based on housing production to satisfy use-values, ‘petty-bourgeois landlordism’, where income from rental accommodation is not essential to satisfy use-values, and ‘petty-capitalist landlordism’, which is the production of housing primarily for the realisation of exchange value (through the reproduction of rental income). Movement can occur between each category as different landlords use capital extracted from rent for different purposes.

An interesting aspect of Kumar’s framework is that he considers the role landlordism plays as one of the means of production and as a determinant of the labour process. However, Kumar approaches this subject by focussing on the production of landlordism (i.e. its motivation and form) and not necessarily by analysing the latent effects of the diversity of different forms of landlordism. Here, there also seems an opportunity to analyse how familial, gender, and inheritance relations interact to produce variable landlord–tenant relations and subsequently shape more general labour processes. For example, the nature of landlordism often affects the way in which small-scale businesses operate – and whose labour is invested in such activities. A further important example discussed is access to, and the use of, services.

As such, there may be a crucial interaction between landlord–tenant relations and labour that needs to be understood in greater depth. This paper attempts to analyse this relationship by examining the ways in which different forms of landlordism shape the capabilities of tenants and landlords alike and how the nature of landlord–tenant relations adapts due to the diverse production of landlordism. Secondly, the paper will also consider how the character of landlordism in low-income areas is ‘symbiotically’ produced between landlords and tenants, particularly in the context of the tensions surrounding rent extraction.

5. The type and character of landlordism in Kisumu and Kitale

The following section presents findings concerning the diversity, character, and motivations for landlordism among the sampled landlords. shows that the average landlord surveyed rents slightly over ten houses and that the majority of landlords (61%) own only one plot of land. A small number of landlords (22%) were found to own three or more separate plots of land. UN-Habitat has previously used the figure of 10 houses as a point at which to classify landlords below this level as ‘non-commercial’ and above as ‘commercial’ (UN-Habitat Citation2003). The landlords surveyed for this research generally seem to hover between this level.

Table 1. Average number of houses and plots owned by landlords across all sample sites.

That most landlords surveyed own one plot of land, often means that many such landlords live on the same plot of land as their tenants. Where this is the case, a set of relations develop which perhaps undermine some common conceptions surrounding landlordism. Firstly, some surveyed landlords did not necessarily perceive renting as a profit-seeking strategy. This was the case with one landlord interviewed, PAO a 50-year-old female who lives in Manyatta B, who at the time of interview stated that she rented six houses charging 600 KSh ($7.14) per month for each house. This is a particularly low rent amount compared to other rental houses in the same area and when asked about collecting deposits she replied that ‘I initially charged people a deposit – but if you tell people you are charging a deposit, you scare them away’. In similar cases, it is generally evident that bureaucratic rules surrounding rent (such as contractual agreements and deposits) are lacking in such locales. The majority of both tenants (68%) and landlords (55%) interviewed gave indication that no (written) contract was present.

Many such ‘landlords’ should more correctly be categorised as ‘landlord families’ as many viewed rental tenure as an inherently familial activity. SA, for example, a landlord in Manyatta B, inherited his one plot of land from his parents, which he now collectively owns with his brothers and sisters. When asked to describe his life history he explained that when he inherited his land he had very little income so decided to progressively build houses around his own house on what he described as ‘just a homestead’. SA was almost reluctant in his acceptance of renting as a livelihood strategy claiming that ‘tenants are difficult to live with as each comes with his/her own habits’.

It is apparent that for others, however, rental housing does become a more overtly capitalist strategy such as for those landlords outlined above who own 20 or more houses. It was found that many such landlords could buy land and build rental accommodation through holding jobs within the government, municipal council, or extra-state institutions. One landlord, MO, commented that he used his salary from his position in the Ministry of Forestry to pay for the construction of rental housing. Retired since 2008, he now earns 30,000 KSh ($357) per month from the rental business, which is a relatively higher income than most tenants and landlords alike.

It would be easy to label such landlords as ‘outsiders’ (or as ‘expansionist’) as many were not born in the areas in which they rent houses. Yet, the periods in which such landlords bought land were (often) found to be many decades in the past. Moreover, their investment often mirrors the most common spatial form of landlordism, namely, an original house around which rental houses are built over a prolonged period. Through life-history interviews it was found that the label ‘outsiders’ mostly emerges through the nature of their employment, in which they travel around the country (predominantly to other large cities such as Nairobi and Mombasa). Many such landlords view their investment as a concurrent base for their (future) family and as an income source during their retirement.

Furthermore, the family dynamic must be understood as key when characterising landlordism at the sample sites. As in the case of SA, the landlord quoted above, many landlords were found to have inherited their plot(s) and rental businesses from their parents or deceased spouses. This included a particularly high number of widows. The high proportion of female and widowed landlords in low-income areas has been noted by previous empirical research in Latin America and Africa (Datta Citation1996; Crankshaw et al. Citation2000; Gilbert Citation2008). The results of this research also support the general conclusion that rental accommodation is an important livelihood for many single and widowed women.

Therefore, the characteristics of landlord households (gender, family size, etc.) and the social relations of inheritance are particularly important factors in the form that landlordism takes. For example, many of the widowed landlords interviewed inherited only a small plot of land due to subdivision between co-wives and/or other family members. Such women typically own fewer houses compared to other landlords and rely on rental accommodation as their primary source of income.

Comparable research in Mwanza, the second largest city in Tanzania, has found many similar characteristics to that detailed above (Cadstedt Citation2010). Cadstedt states that ‘the relationship between tenants and landlords in my study is not characterised by rich landlords exploiting poor tenants. Instead, it is a symbiotic, interdependent relationship in which many small-scale landlords need the rental income and many tenants find the payment of rent a burden in an insecure economic situation’ (Citation2010, p. 50). The results presented so far tentatively suggest that similar conclusions can be made in relation to Kisumu and Kitale. However, there is a need to expand upon the notion of a ‘symbiotic’ landlord–tenant relation and this will be done in the following sections.

6. Absentee landlordism in smaller Kenyan towns and cities

The following section examines further the different forms of landlordism and contends that landlordism in smaller Kenyan cities often takes on different forms to that of Nairobi. In particular, it will be argued that ‘absente landlordism’ may have different connotations in Kisumu and Kitale when compared with Nairobi. As shows, more females in both the ‘landlords’ and ‘tenants’ categories were interviewed for the questionnaire survey. This does not necessarily mean that females comprise most residents or, indeed, landlords. On the contrary, due to reasons of practicality, most interviews were conducted between 9am and 5pm on weekdays; meaning the results are perhaps more representative of this time of day and week – a time at which more women were available for interview.

Table 2. Gender composition and average age of respondents across all samples sites.

In poorer settlements in Kisumu and Kitale, many men at such times travel to employment, businesses, and transport centres looking for, or engaging in, (often casual) work. Moreover, it is not necessarily a time of day when landlords are available for interview. Arguably, this methodological observation presents an immediate problem for the term ‘absentee landlordism’, considered as a particularly important category in Nairobi’s (Amis Citation1984; Mwangi Citation1997; Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008) and Mombasa’s (Macoloo Citation1994) low-income settlements.

In Kisumu and Kitale, as previously outlined, many male landlords are technically ‘absent’ due to the nature of their employment. Such landlords often reside on multiple plots at different times and for different purposes. For example, one particular landlord interviewed, a 67-year-old male in Manyatta A called EW, owns five plots of land. Only two of these plots are in Kisumu and at the time of interview he resided on one of those plots which he considered to be his family home. He also owns a shop and butchers in Kakamega, a smaller town 50 km north of Kisumu, at which he resides for most of the week to supervise and work on his businesses.

The high percentage of female respondents () and time of interview also presents an added dynamic to this issue. This is because the literature often considers absenteeism to be permanent and embodied in a particular person (Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008). Yet, whether absenteeism is permanent (or categorically final) may hinge on such methodological considerations. Many male landlords may indeed be ‘absent’ from the daily life of ‘the slum’ but present at certain other times to collect rent, engage in businesses, or to meet their wife (or wives in polygamous marriages). Secondly, the majority of those women present (i.e. engaged in labour in or around the homestead) were found to be wives or partners of those landlords who were temporarily/permanently residing on other land plots but who nevertheless controlled rent money. In such situations absenteeism is much more fluid and contingent than a simple binary between ‘absent’ and ‘in situ’.

Intuitively, although the proportion of female landlords in the sample is indeed relatively high (due partly to inheritance outlined previously), it is perhaps surprising to find that women comprise the majority of landlords in the sample (16 out of 27 or 59% according to ). In one sense, this may not be peculiar given that previous studies in African cities have found a higher proportion of female landlords (Datta Citation1995). One finding from the survey is that many wives of husbands who own land claim they are the landlord (or household ‘head’) in common. So, the question arises as to which measure is used to determine who the landlord is (as embodied in a person). If judged by names on title deeds, then the results reveal that most landlords (82%) are men. However, viewed in terms of the day to day running of rental businesses – such as living on plot or the collection of rent – then the gender balance becomes more equal.

Regarding settlements in Nairobi, Gulyani, and Talukdar claim that ‘the fact that the majority of the landlords are “absentee” – in that they do not live on site – means that they neither suffer from the appalling living conditions nor gain any of the prestige associated with owning and living in a good-quality and well-functioning home’ (Citation2008, p. 1931). The results of this research show that this claim needs to be tempered by family and gender dynamics and the nature (and degree) of absenteeism evident.

Moreover, the way in which Amis (Citation1984) originally draws out ‘absentee’ landlords in his research in Nairobi is as a (nationally) well-connected business and political elite who maintain wealth and power by holding property in low-income settlements. Such a situation is perhaps not representative of smaller urban centres in Kenya such as Kisumu and Kitale where political ties are less. Therefore, ‘absentee landlordism’, applied as a distinct category to smaller towns and cities in Kenya, needs to be revaluated as a much wider social concept and not solely considered a distinct class of landlordism.

7. Socio-economic differences between landlords and tenants

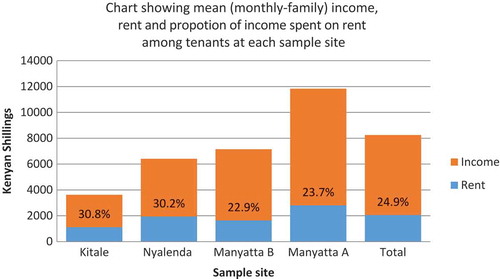

The following section will show that the production of landlordism responds not only to variations in the household structure and motives of landlords but also to social dynamics that arise from differences in the socio-economic standing of landlords and tenants. To do this, such differentiations will first be outlined. shows that tenants in the survey generally do not pay particularly large proportions of their incomes on rent (at an aggregated 24.9%). However, there are key differences between each subsample location. Interestingly, among the sample in the relatively poorer settlements, Kitale and Nyalenda, where average incomes are typically lower and which are generally more poorly serviced, tenants appear to be paying a higher proportion of their incomes on rent (30.8% and 30.2%, respectively). In the relatively wealthier subsample locations, Manyatta A and B, tenants are paying relatively smaller proportions of their incomes on rent (23.7% and 22.9%, respectively).

This result may portray a dynamic of the rental economy in low-income settlements in smaller Kenyan cities. As outlined in previous sections, some landlords see renting as a ‘necessary evil’ whereas others perceive it as a profit-seeking strategy. Landlords among the sample residing in Kitale and Nyalenda tended to have the lowest incomes and therefore the least capacity to expand their housing stock. At the same time, they tended to be among those who were least committed to renting as a livelihood strategy.

Put differently, there may be a stagnation at the bottom of the rental market, similar to that described by Huchzermeyer (Citation2009), where landlords are often unable to invest in new (and the quality of) housing but where tenants are paying a higher proportion of their income on rent. In the case of Kitale and Nyalenda this can partly be explained by the high proportion of widowed landlords surveyed, and by the high number of landlords surveyed who were previously rural landowners whose plots have gradually been incorporated into the urban area. Such landlords typically have lower incomes than other classes of landlords. Although the sample size is small, when service delivery is disaggregated by income, the results also reveal that the mean income of landlords providing services is approximately twice as high of those not (21,213 KSh compared with 9,133 KSh in the case of electricity and 20,467 KSh with 11,000 in the case of sanitation).

As such, there is a dynamic between minimum housing conditions, rent levels and the capabilities of particular landlords. The survey suggests that because low-income landlords provide housing among a general absence of public housing provision, and that such landlords rely heavily on that income, rents are not always commensurable with the (minimum) quality of housing. While this stagnation has differentiated landlordism and the quality of housing, there is also much more general social differentiation evident across all sample sites. As shows, there are substantial differences in income levels between different sample sites in Kisumu with residents in Nyalenda, for example, having mean monthly family incomes of 6,405 KSh ($76.22) which is almost half that of residents living in Manyatta A (at 11,831 KSh ($140.79)).

Figure 2. Income of tenants and percentage of income spent on rent across different sample locations.

Through observations made during the research it is apparent that certain pockets of previously low-income areas in Kisumu have become gentrified to house a growing middle-class population. Such housing is increasingly well-connected to services on a private basis. Evidence from the survey revealed it costs as little as 2,000 KSh ($23.80) to install an individual water connection, 200 KSh ($2.38) for monthly waste collection and as little as 500 KSh ($5.95) per month to receive a rudimentary connection to electricity. This means housing within certain low-income areas is increasingly in demand from certain middle-income tenants – particularly in areas adjacent to main roads or town centres. As an example, a small proportion of tenants were found to pay between 6,500 and 8,500 KSh ($77.35 to $101.15) in monthly rent payments.

There are also key differences between Kitale and the sample sites in Kisumu, suggesting much wider differences in material wealth and housing conditions exists in and between Kenya’s ‘secondary’ cities themselves. The complexity of landlords and tenants living in such divergent circumstances means objectifying ‘slums’ as homogenous becomes extremely problematic. Wider research has indeed acknowledged the rupturing of wealth levels within low-income settlements themselves (Roy Citation2005; McFarlane Citation2008, Citation2012; Doshi Citation2013).

It is also apparent that different forms of landlordism have emerged in response to the variable demand for housing. In some cases, certain landlords have constructed housing solely aimed at specific sections of the market. What is also evident is that many individual land plots contain houses which range substantially in terms of build conditions and rent levels. For example, it is increasingly common that self-contained apartment blocks (i.e. services within the house) are built alongside mud-brick houses (typically sharing services) on the same plot. Such differentiations have arisen due to the minutiae of how landlords have developed particular plots of land but are also a response to high but differentiated demand for housing.

An example of the above can be seen from JO, a 40-year-old female in Manyatta A who rents houses on land which is registered in her husband’s name. Between them they rent 12 separate tenanted dwellings, however, the rent amount for those houses ranges substantially from 1,000 KSh ($11.90) to 10,000 KSh ($119) per month (as does the build quality of the houses). When asked about sanitation and electricity services corresponding to rent amounts she replied that some houses had services whereas other didn’t. When asked further about such variations she replied that ‘I have to provide services for both classes’ As such landlords provide a range of housing options, this often means a ‘different’ set of relations develop between the landlord and different tenants living on that same plot. It is to these issues that the remaining sections now turn.

8. The wider socio-spatial importance of life-quality indicators

It is interesting to compare differences in life quality which have emerged between tenants and landlords. This section analyses the wider socio-spatial significance of such life-quality indicators and their effects on the wider production of landlordism. The results in show that landlords surveyed have a better quality of life in comparison to tenants in most measures including income, house size, and length of stay. Landlords have a mean monthly household income which is over twice as high as the mean household income of tenants (17,792 KSh ($212) compared with 8,056 KSh ($95.87)).

Table 3. Differences in life-quality indicators between tenants and landlords at all four sample sites.

Another measure of life quality is the ‘length of stay’ or how long the current occupant has lived in that dwelling. reveals a large discrepancy between landlords who were found to have lived 23 years on average (mean) in their current dwelling and tenants who were found to have lived 4.4 years on average in their current dwelling. Such divergent tenure patterns have previously been explained because of the age gap and life cycle choices of tenants in comparison to landlords (UN-Habitat Citation2003 Influence and invisibility:). Although not easily generalisable, tenants (as in this research) may typically be younger than landlords (Crankshaw et al. Citation2000; Arku et al. Citation2012) and therefore view renting as advantageous to access employment or education in urban areas. Another contributing factor evident from life-history interviews is the large number of women who had recently migrated from rural homesteads to live with their (new) husbands already in situ. What seems to be apparent is that landlordism affords a luxury of continuity to both the landlord and their family and that there is an important socio-spatial dynamic to be understood as a result of this continuity.

The ‘people per room’ (PPR) (shown in ) was a further life-quality measure gathered by the survey. PPR is essentially a measure of crowding. Although there are methodological issues surrounding PPR, such as extremely small rooms distorting the figure downwards, the results show one striking conclusion. Although landlord families generally have larger incomes than tenants (although, such differences become lower when considered per person in the family), the results reveal that the PPR figure is slightly higher for landlords (2.08) than it is for tenants (2.04). This suggests landlords are living in slightly more crowded conditions than tenants.

Separate research in Nairobi and Dakar has revealed overall PPR figures of 2.6 and 2.8, respectively, for low-income areas in the two cities (Gulyani et al. Citation2012). The average for Kenya is estimated to be 1.55, which is much lower than the findings of this research due to the incorporation of rural areas (Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008). The figures for Nairobi and Dakar are much higher than the figures collected during this research which seems to suggest that residents of Kisumu’s (and perhaps Kitale’s) poorer settlements are living in better living conditions in comparison to those of Nairobi.

What is arguably more interesting about similar crowding levels for both tenants and landlords, however, is that such figures have been formulated from a decidedly different grounding. As shown in , landlords in the sample generally live with bigger families in bigger houses, whereas tenants live with smaller families in smaller houses. The PPR figure in many ways hides this differentiation. Landlords who reside in slightly worse living conditions to maximise income from better constructed rental housing is not conceptually new to the literature (Kumar Citation1996). Whereas Kumar uses this point to categorise the production of landlordism, it also raises critical questions regarding the spatial forms of advantage and social effects that bigger landlord families have upon wider urban development.

The spatial significance of larger families living longer in the same place develops from the fact that such families are often spread across more than one house on the same plot. Therefore, not only are landlords residing in different ‘living conditions’ relative to tenants but are also living in slightly different socio-spatial configurations. In cases where a more traditional (rural) spatial-familial structure has been maintained, rental accommodation follows an enduring pattern of a central courtyard area – around which houses (for rent or otherwise) are built. In instances where outside/expansionist investors in rental tenure (loosely defined) have invested in renting, this spatial-familial structure tends to break down, increasingly in the direction of self-contained houses (which are typically built with different spatial-aesthetics in mind such as security) and 2–4 story apartments buildings.

The reality of larger landlord families holding to a particular familial-spatial structure, increasingly interspersed with rental houses, has had a systematic influence on the formation of low-income settlements in Kenya’s smaller urban centres. For example, many services, such as electricity and sanitation have essentially followed this ‘communal’ pattern of land management and control. A subsequent set of relations has therefore emerged regarding the communal installation, appropriation, and management of services at the level of the plot.

The social significance of larger landlord families is firstly that landlords can, and the results reveal frequently do, take on ‘dependents’ to live on the same plot as tenants. Previous research has preferred to describe such people as ‘sharers’ and has noted the difficulty of distinguishing such people from tenants (UN-Habitat Citation2003). The term dependent is used by this research as it implies a relation most commonly based on the concession of rent (i.e. dependents are charged no or a reduced rate of rent) and in some cases on the provision of labour in return for shelter.

Dependents were typically found to be relations of landlords, however, are sometimes people who come to adopt roles in the community such as ‘caretakers’, ‘rent-collectors’, and/or managers of businesses based from the homestead (such as those based on the use of electrical appliances such as fridges). The ability to grant concessions to dependents and therefore land use patterns can be interpreted as a form of spatial power. Moreover, as determinants and holders of control over the communal delivery of services, landlords have substantial control over how businesses are run from the homestead. The results reveal a general trend in this regard for landlord family members (and their dependents) to derive greater benefit from such forms of advantage.

Such businesses are characteristically small in nature including food sellers, clothes sellers, ice sellers (using fridges), hairdressers, and tailors. The literature often describes such businesses as ‘informal traders’ (de Soto Citation1989) in that they may not be registered, recognised or pay taxes to the state. Yet, while such businesses may be informal from a regulationist perspective, viewed through the lens of landlordism such businesses are structured both socially and spatially by the concessions that landlords can grant due to monopolistic control of land (and therefore access to the means of production (Kumar Citation1996)).

While landlord families were found to have disproportionate control over small-scale businesses, larger landlord families were also found to be used as an apparatus of power in other circumstances. This is particularly evident where landlords live close to their tenants. For example, when asked about her relationship with the landlord, JO a tenant, replied ‘at times we get problems from the landlord – if we ask for renovation from the landlord, the landlord and daughters come and abuse use’. The results also show that this phenomenon can be extended to family members of the landlord who put informal pressure (often to the extent of verbal abuse) on tenants to pay for rent and/or services when they are otherwise unable.

In a small proportion of cases, then, the landlord’s (larger) family acts as a form of both social advantage and social control. The landlord also begins to exert increasing control over the tenants ‘personal’ and ‘financial’ situations as both a spatial form of advantage and as a means to extract rent reliably. As an example, MOO, a landlord in Manyatta B, claimed that ‘domestic problems are why I am here – I have to deal with them a lot’. A second example is that of PAO a 50-year-old female landlord (of 8 houses) in Manyatta B who when asked about domestic disputes replied that ‘Yes, I get involved in domestic disputes. When I am called to respond, I go and make a fair judgment for both parties – those in the wrong are made to move’.

In such a way, landlords in Kisumu and Kitale’s low-income settlements have developed a much more expanded (social) role than that solely defined by the extraction of rent. This expanded role, however, shares a key relationship (and tension) with the economic function of landlordism. The final sections of this article will analyse this tension closer. It will be argued that the social ‘control’ detailed above, is in some cases used as a means by landlords to maintain ‘peace’ on their property as an instrumental (but often contradictory) way to ensure the reliability of rent extraction.

9. Symbiotic landlord–tenant relations

For many, the relationship between landlords and tenants is defined by the extraction of rent from a commodity (i.e. housing) which is being produced and sold to tenants (Kumar Citation1996). As this section will aim to show, many landlords among the sample (particularly at the lower end of the rental market) are failing to extract rent reliably. This fact often alters the terms upon which the relationship between landlords and tenants is defined. In certain cases, landlords have become intimately involved with the ‘personal’ (and financial) lives of tenants and have initiated various ‘tactics’ to extract rent reliably. One such tactic is to maintain generally good relations with tenants – even though the need to extract rent produces periodic (and suppressed) conflicts.

Firstly, the results reveal that 79% of landlords claim that their current tenants are not paying rent on time. The four landlords who indicated that their tenants ‘always paid on time’ typically rented only a small number of houses in which they had maintained close control over who those tenants were. When asked about late rent payment, a landlord called PA said ‘that’s normal – they do it frequently. Some owe 2 months’ rent’. This suggests that not only are many tenants failing to pay rent reliably but also that landlords seem to accept late rent payment as a normal occurrence.

Tenants () were also particularly open about not paying rent on time with 77% claiming that they had made late rent payments in the recent past or were currently behind in rent payments. Moreover, 19% of tenants said they were paying rent late on a ‘frequent’ basis. Many tenants stated the reasons were to do with a lack of (or intermittent) employment paid on a non-salaried basis. A small number of both tenants and landlords quoted ‘familial problems’, ‘illnesses’, or ‘death in the family’ as reasons why rent was not paid on time.

Table 4. Percentage of tenants making late rent payments.

When asked to stipulate for how long they missed rent payments, varied responses were received from tenants (). About 70% of those behind in rent payments indicated that they had fallen behind for 1 month or longer, with some suggesting that they had failed to pay for up to 3 months. There were no tenants who admitted to falling behind in rent payments for longer than 3 months but many landlords claimed this was a regular occurrence.

Table 5. How long are tenants behind in rent payments.

As an example, PA is a 58-year-old female landlord who inherited her one plot of land from her father, who is now deceased. The title deed for the land is still registered in the name of the father. At the time of interview, she rented six houses which varied in rent levels ranging from 600 KSh ($7.14) to 3,500 KSh ($41.65) per month. When asked about late rent payments she stated that ‘the payment is very poor. Some owe three months, some owe two. I usually talk with them. This is happening because I have a disability’.

Similarly, DA, a 50-year-old female landlord in Nyalenda, who owns one plot of land which she inherited from her husband (now deceased), rents four houses and stated that ‘they pay as they wish – some even go for one year without paying – one even went for two years without paying’. These results suggest that rent is often not paid on the times and in the way it is intended. That is to say, rent is not defined by the moment of its collection but rather by a buffer period of (typically) 3 months in which rent can become compartmentalised into piecemeal payments, contested by tenants and/or shaped by the specificity of the landlord–tenant relationship.

When DO, a 31-year-old male landlord in Manyatta B, was asked about late rent payments, he replied with the following comments:

I have never had to evict anyone. Because those problems are so frequent it is just normal … Delay in rent payment is there, even defaulting. When a relative in a house dies or when there is a job shortage. Sometimes violence between husband and wife means the husband does not pay rent. The majority of tenants do not pay rent regularly – only 2 are reliable. We have stayed with them for so long that we have a relationship – they are suffering we know.

DO was not the only landlord to have maintained such a sympathetic relationship with tenants in the face of difficulties in rent payment. When SM, a 30-year-old male landlord who also lives in Manyatta B, was asked how many tenants made late rent payments he replied ‘nearly all of them’. Yet, when asked about the relationship he had with tenants he claimed it was ‘very warming, when you are lacking something you just get it from each other’. This was also despite further questions revealing that SM had evicted a tenant in the recent past.

In some senses, therefore, the ‘good’ relationship between tenants and landlords (as described by landlords and tenants themselves) is seemingly contradictory because rent is not, in fact, being extracted reliably. Such a relationship is supplemented by the mutual experience of poverty and the close spatial proximity of many tenants and landlords. In other senses, however, such seemingly ‘good’ relations are constantly in tension with the need to extract rent reliably, particularly as rent is the primary source of income for many landlords.

It is the contention of this article that the accepted norm of a 3-month buffer period is the outcome of a ‘good’ relationship which is mutually advantageous for both tenants and landlords to create. In the case of tenants such concessions are advantageous given the uncertain socio-economic circumstances in which many live. Yet, given such poor conditions (which many landlords also share), it is also advantageous for landlords to provide such concessions. Such a development is reflected in the ways in which both tenants and landlords describe (i.e. verbally propagate) late rent payment as a lived, everyday reality.

As a further example, when JO, a tenant living in Manyatta B, was asked whether she made late rent payments she commented that ‘yes, quite frequently. I just have a peaceful dialogue with the landlord. After, I agree to pay in instalments. After every two weeks I pay’. When JO, a landlord living in Nyalenda, was asked what happened when his tenants made late rent payments he replied that ‘we just sit and talk – maybe there is a late salary or an urgent need’.

Both tenants and landlords, such as those quoted above, conceive of the buffer period as a ‘talking’ or ‘dialogue’ period. Such a ‘talking’ period is mutually created by landlords and tenants as peaceful because it can be used as a means by both parties to pay/not pay rent. Yet, the creation of this peaceful possibility simultaneously points to the fragility upon which the relationship is built. To be sure, such claims are not made to deny the possibility that landlords and tenants can have genuinely good relations. Rather ‘rent’, more broadly conceived, assimilates these, often contradictory, tensions.

Rent also becomes contested via landlords who increasingly intervene in tenant’s family and domestic circumstances. This is particularly evident in the quote from the landlord DO, above, who highlighted some of the common ‘domestic’ problems which landlords mediate including husbands who abandon their families. In a particularly long interview, DO described himself as a ‘community mobiliser’ rather than a landlord and viewed it as his responsibility to manage such situations once they occurred.

Therefore, the landlord–tenant relationship in Kisumu and Kitale’s low-income settlements is not solely defined by the extraction of rent. At the lower end of the rental market (in particular) the role of the landlord surpasses the collection of money and becomes extra-economic. In many ways, this appears to be common sense. However, the argument this section has forwarded is that this extra economic relationship incorporates several economic tensions. Put differently, the relationship between landlords and tenants is predicated on being peaceful as an instrumental norm to extract rent in a context of socio-economic instability.

10. Conclusion and policy implications

Landlordism among the sample in Kisumu and Kitale is diverse, and in certain ways subtly different to that of low-income settlements in Nairobi. The survey found most landlords were small-scale while a minority owned multiple plots and multiple houses. One key differentiation is that larger-scale landlords are typically more mobile in terms of their landholding, employment, and business activities. A feature of smaller scale landlords is the lack of a profit-seeking motive, with renting commonly viewed as a demanding and an unreliable income source. While this is true, there is a class of landlords, including a high number of widows, who are simply unable to expand or improve their housing stock.

Such differentiations are cross-cut by the familial nature of landlordism. For example, many landlords who own multiple plots have family members and/or dependents residing on those different plots. The findings suggest that the term ‘absentee landlordism’ has been narrowly framed methodologically and conceptually when applied to Kenyan cities. A closer analysis of absenteeism reveals characteristics of the relative power balance within landlord families, control over rent money, and the gender dimensions of mobility and inheritance. The results suggest that while husbands in landlord families are often absent, women are often present to run rental businesses; yet, control of rental income and property deeds often remains with men.

The diversity of landlordism is partly a product of the variable demand for housing but is also reflected in the production of landlordism itself. At the lower end of the rental market, landlords and tenants often have a more interlinked socio-spatial relationship. Conflicts over rent are overcome through mutual agreements and ‘good’ relations which are a form of tenure security of last resort as they simultaneously point to the fragility of economic relations.

These at once economic tensions produce outcomes which widen the function of landlordism into other aspects of everyday life – domestic, financial and, above all else, spatial. Landlord–tenant relations can therefore rightly be described as ‘symbiotic’ but also multidimensional. Crucially, that landlord–tenant relations are mutually produced has not precluded the emergence of certain forms of social (dis)advantage. Landlord families typically live much longer in the same place and are generally larger in comparison to tenanted households. This differentiation is particularly advantageous to landlord families in terms of social control over rent extraction, small-scale business opportunities, and control over plot-level services.

The diversity of landlordism evident, distortions at the bottom of the rental market, and the symbiotic relation between tenants and landlords mean that policy interventions will impact landlords and tenants differently. The recently implemented tax policy (January 2016) to charge landlords (below a certain income) a flat rate 10% residential tax is a case in point. While some landlords in Kisumu and Kitale’s low-income settlements can afford this amount, others cannot. The likely outcome at the lower end of the rental market will be an increase in rents for substandard housing and an increase in tensions among landlords and tenants.

In the context of severe shortages of affordable public housing and insufficient controls on private housing standards, there has developed in Kenya a class of poor landlords unable to service or improve their rental houses. Rather than punish such landlords through punitive measures, national and municipal government should pursue subsidised service delivery projects and improved access to financing for housing upgrades. Such measures would help to reduce poverty among both landlords and tenants and equalise rent rates. In the long term, Kenya should address the shortage of adequate housing through increased public provision and more robust regulations on landlords, which take proper account of the diversity of landlordism evident.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shaun Smith

Shaun Smith recently completed his PhD in geography at Royal Holloway, University of London. His research focuses on service delivery and land tenure issues in low-income settlements of developing countries. He is currently visiting lecturer in geography at Royal Holloway.

References

- Aina TA. 1990. Petty landlords and poor tenants in a low-income settlement in metropolitan Lagos, Nigeria. In: Philip A, Peter L, editors. Housing Africa’s urban poor. Manchester (UK): Manchester University Press; p. 87–101.

- Amis P. 1984. Squatters or tenants: the commercialization of unauthorised housing in Nairobi. World Dev. 12:87–96.

- Anderson D. 2005. History of the hanged. London (UK): Weidenfield and Nicolson.

- Archer RW. 1992. An outline urban land policy for the developing countries of Asia. Habitat Int. 16:41–77.

- Arku G, Luginaah I, Mkandawire P. 2012. You either pay more advance rent or you move out”: landlords/ladies’ and tenants’ dilemmas in the low-income housing market in Accra, Ghana. Urban Stud. 49:3177–3193.

- Bierre S, Howden-Chapman P, Signal L. 2010. Ma and Pa’ landlords and the ‘Risky’ tenant: discourses in the New Zealand private rental sector. Housing Stud. 25:21–38.

- Cadstedt J. 2006. Influence and invisibility: tenant in housing provision in Mwanza City, Tanzania [dissertation]. Department of Human Geography, Stockholm University.

- Cadstedt J. 2010. Private rental housing in Tanzania – a private matter? Habitat Int. 34:46–52.

- Chege P, Majale M. 2005. Building in Partnerships: Participatory Urban Planning in Kitale, Kenya Journal Article in Basin news.

- Crankshaw O, Gilbert A, Morris A. 2000. Backyard Soweto. Int J Urban Reg Res. 24:842–857.

- Datta K. 1995. Strategies for urban survival? women landlords in gaborone, botswana. Habitat International. 19:1–12.

- Datta K. 1996. The organisation and performance of a low income rental housing market. Habitat Int. 13:237–245.

- Davis M. 2007. Planet of slums. London: Verso.

- de Soto H. 1989. The other path: the invisible revolution in the third world. New York, USA: Harper and Row.

- de Soto H. 2001. The mystery of capital: why capitalism triumphs in the west and fails everywhere else. London. Black Swan.

- Doshi S. 2013. The politics of the evicted: redevelopment, subjectivity, and difference in Mumbai’s slum frontier. Antipode. 45:844–865.

- Gilbert A. 2003. Rental housing: an essential option for the urban poor in developing countries. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- Gilbert A. 2008. Viewpoint: slums, tenants and home-ownership: on blindness to the obvious. Int Dev Plann Rev. 30: i–x.

- Gulyani S, Bassett EM, Talukdar D. 2012. Living conditions, rents, and their determinants in the slums of Nairobi and Dakar. Land Econ. 88:251–274.

- Gulyani S, Talukdar D. 2008. Slum real estate: the low-quality high-price puzzle in Nairobi’s slum rental market and its implications for theory and practice. World Dev. 36:1916–1937.

- Hall P, Pfeiffer U. 2000. Urban future 21: a global agenda for 21st century cities. London: E&FN, Spon.

- Hart K. 1973. Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. J Mod Afr Stud. 11:61–89.

- Hay A, Harris R. 2007. ’Shauri ya Sera Kali’: the colonial regime of urban housing in Kenya to 1939ʹ. Urban Hist. 34:504–530.

- Hendriks B. 2008. The social and economic impacts of peri-urban access to land and secure tenure for the poor: the case of Nairobi, Kenya. Int Dev Plann Rev. 30:27–66.

- Hoffmanm ML, Walker C, Struyk RJ, Nelson K. 1991. ‘Rental housing in urban Indonesia’. Habitat Int. 15:181–206.

- Huchzermeyer M. 2008. Slum upgrading in Nairobi within the housing and basic services market: a housing rights concern. J Asian Afr Stud. 43:19–39.

- Huchzermeyer M. 2009. Enumeration as a grassroots tool towards securing tenure in slums: insights from Kisumu, Kenya. Urban Forum. 20:271–292.

- Jones BG. 2012. Civilising African cities: international housing and urban policy from colonial to neoliberal times. J Intervstatebuild. 6:23–40.

- Karanja I. 2010. An enumeration and mapping of informal settlements in Kisumu, Kenya, implemented by their inhabitants. Environ Urban. 22:217–239.

- Klopp JM. 2008. Remembering the muoroto uprising: slum demolitions, land and democratization in Kenya. Afr Stud. 67:295–314.

- Kumar S. 1996. Subsistence and petty capitalist landlords: a theoretical framework for the analysis of landlordism in third world urban low income settlements. Int J Urban Reg Res. 20:317–329.

- Kumar S. 2011. The research–policy dialectic: a critical reflection on the virility of landlord-tenant research and the impotence of housing policy formulation in the urban Global South. City: Anal Urbantrend Cult Theor Policy Action. 15:662–673.

- Lee-Smith D. 1990. Squatter landlords in Nairobi: a case study of Korogocho. In: Amis P, Lloyd P, editors. Housing Africa’s urban poor. Manchester: University Press, Manchester.

- Macoloo GC. 1994. The Changing Nature of financing low-income urban housing development in Kenya. Housing Stud. 9:281–299.

- McFarlane C. 2008. Sanitation in Mumbai’s informal settlements: state, ‘slum’ and infrastructure. Environ Plann. 40:88–107.

- McFarlane C. 2012. From sanitation inequality to malevolent urbanism: the normalisation of suffering in Mumbai. Geoforum. 43:1287–1290.

- Mwangi IK. 1997. The nature of rental housing in Kenya. Environ Urban. 9:141–160.

- Otiso KM. 2003. State, voluntary and private sector partnerships for slum upgrading and basic service delivery in Nairobi City, Kenya. Cities. 20:221–229.

- Otiso KM, Owusu G. 2008. Comparative urbanization in ghana and kenya in time and space. Geojournal. 71:143-157.

- Payne G, Durand-Lasserve A, Rakodi C. 2009. The limits of land titling and home ownership. Environ Urban. 21:443–462.

- Rakodi C. 1995. Rental tenure in the cities of developing countries. Urban Stud. 32:791–811.

- Republic of Kenya. 2010. The 2009 Kenya population and housing census: volume 1A: population distribution by administrative unites. Nairobi: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

- Rigon A. 2014. Building local governance: participation and elite capture in slum-upgrading in Kenya. Dev Change. 45:257–283.

- Roy A. 2005. Urban informality: toward an epistemology of planning. J Am Plann Assoc. 71:147–158.

- Syagga P, Mitullah W, Karirah-Gitau S. editors. 2002. Draft nairobi situation analysis supplementary study: a rapid economic appraisal of rents in slums and informal settlements. Government of Kenya and UN-HABITAT Collaborative, Nairobi Slum Upgrading Initiative. Nairobi: Development Studies, University of Nairobi.

- Temple NW. 1974. Housing preferences and policy in Kibera, Nairobi. Discussion Paper No. 196, Institute for Development Studies, University of Nairobi.

- Turner JFC. 1972. Freedom to build. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company.

- UN-Habitat. 2003. Rental housing, an essential option for the urban poor in developing countries. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- UN-Habitat. 2005. Situation analysis of informal settlements in Kisumu. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- Van Zwanenberg R. 1972. History and theory of urban poverty in Nairobi: the problem of slum development, Discussion Paper 139, Nairobi: Institute for Development Studies, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

- Werlin H. 1999. The slum upgrading myth. Urban Stud. 36:1523–1534.