ABSTRACT

To shed light on fair blue urbanism, we studied the demands, obstacles and opportunities as well as knowledge needs of various citizen groups living in Helsinki Metropolitan Area. The perspectives were identified and explored by experts using an innovative ‘role chair’ method of opinion elicitation. The responses, aggregated as clusters, highlight the multiple roles of urban blue infrastructures and demonstrate that they constitute important parts of cultural processes and environmental justice. Commonalities and differences found between clusters of age and ethnic groups, challenged groups and groups engaged in particular forms of water-related activity suggest paths to inclusive actions for fair use of ecosystem services. Important unrecognized knowledge needs were also discerned. We conclude that environmental justice within engagement with water areas involves wide diversity. Facilitating the recognition of such diversity by experts and then by authorities, stakeholders and citizens concerned through interactive group methods is key to fair blue urbanism.

1. Introduction and objectives

Environment, especially in cities, has become a key area of societal concern and activity, and of controversy, contestation and conflict (McGranahan and Marcotullio Citation2005). This is due to the physical process of urbanization, to the vital importance of natural environments and resources for human sustenance, and to the intensified use of them and to new pressures (da Silva et al. Citation2012). An important aspect in urbanization is the quality and functions of green and blue infrastructure, that is, the fabric of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems including water bodies and shore areas.

Societal transitions toward (or away from) urban sustainability extend beyond the ecological and physical to social and cultural dimensions such as urban life-style. Such extensions take place as environment, sustainability, resilience and ecosystem services have become boundary objects (Star and Griesemer Citation1989; Abson et al. Citation2014) or bridging concepts (Baggio et al. Citation2015) and thereby also symbols for many other concerns and social movements.

All these aspects of urban living environments are prominent in the increased attention to environmental justice (Ernstson Citation2013; Banerjee Citation2014). In order to improve environmental justice, it needs to be investigated and pursued in concrete cases and in practical processes of urban development (Hampton Citation1999), but it also needs to be analyzed in more depth with regard to its theoretical foundations, conceptual frames and representations (Floyd and Johnson Citation2002); its contents, relations and contexts; and its general methodological aspects (Schlosberg Citation2013).

Water is a key element in environmental justice, regarding the physical and biological as well as the societal aspects of its use. It has particular importance in urban environments which have often grown near water bodies and require access to water to thrive (Blake Citation1956; IHP Citation2006). Much research on environmental justice related to water has consequently addressed the right to potable water and its restrictions due to pollution or lack of access (Debbané and Keil Citation2004). On the other hand, justice in providing access to water bodies in a land-use planning and recreational use contexts has often been studied (e.g. Dahmann et al. Citation2010), reflecting the importance of water bodies and how they are governed. This is a common theme in studies of the influence of blue space on human health (Depledge and Bird Citation2009; White et al. 2013; Finlay et al. Citation2015).

In many studies of ecosystem services, water has been treated almost purely as a physical substance (e.g. de Groot et al. Citation2010). Gómez-Baggethun and Barton (Citation2013), in analyzing ecosystem services in urban planning, address water more extensively but also from a biophysical and technical angle. And yet, ‘blue space’ is a highly coveted urban amenity, prompting studies of valuation (Sander and Zhao Citation2015) and preferences (Hayden et al. Citation2015) which begs the question of who are the beneficiaries of these values.

Water in relation to environmental justice is not only about the right of access. Due to the fundamental sociocultural roles of water, it is at once an object of contestation and a carrier of justice, and a facilitator of processes in providing justice and in governing societies. This is conspicuous in urban settings where the needs for water are pronounced and simultaneously the formative societal processes are most intense. Nevertheless, in the growing literature on environmental justice aspects of urban green space, the particular importance of water has not been addressed very often, especially from a social and political point of view (Kabisch and Haase Citation2014; Wolch et al. Citation2014).

During recent years, such aspects and processes of social ecology and of environmental justice have, however, been noted in so-called blue urbanism, a wide concept referring to the cultural role of water in urban environments (see Section 3). Blue urbanism has a background partly in social philosophy (Beatley Citation2014) and in the politics of emancipation (Gandy Citation2004), that is, political ecology, though other and more general readings of the concept are also called for and can shed new light on the interactions between urban citizens and waters, and on the social factors and tensions involved.

Empirical studies on environmental justice in relation to blue infrastructure have analyzed citizen perceptions (e.g. Brown and Kyttä Citation2014). When opinions of experts on urban water have been analyzed, the focus has been on their own perceptions about equitable access to blue infrastructure, with only some studies of how they identify perspectives of other groups (e.g. Scholz et al. Citation2013). There is thus a gap in the analysis of expert perceptions of needs from the point of view of citizens. Also the methodologies for eliciting recognitions and opinions of experts identifying themselves with citizen groups are only emerging (Jorgenson and Steier Citation2013; Brouwer et al. Citation2017; Preller et al. Citation2017).

We set out to fill this gap by a methodology where experts are led to reflect on the roles and conditions of lay groups to identify and characterize their needs, obstacles and opportunities. Specifically, our goal was to understand how experts frame and take into account the perspectives of various groups of citizens with regard to procedural and distributive environmental justice.

Focusing on Helsinki Metropolitan Area, we thus posed the principal research questions: (1) How do experts recognize demands, obstacles and opportunities of various citizen groups to access and engage with water elements or blue infrastructure in the region?; (2) How do expert perceptions of the demands, obstacles and opportunities of interaction vary between different citizen groups, and what clusters of citizen groups can be discerned?; (3) What are the implications of these perceptions on urban resilience and environmental justice fused into the notion of blue urbanism, specifically for deliberation and collective learning?

2. Theoretical constructs and conceptual models

2.1. Blue urbanism as a transcendent sociocultural construct

Blue urbanism combines spatial and substantive dimensions. In spatial terms, cities are linked with nearby water bodies, including sweet water in lakes, ponds, rivers, streams and groundwater aquifers, with adjacent terrestrial and wetland systems, and with nearby or even more remote areas in seas and oceans. The substantive dimension involves sociocultural, economic and political as well as biophysical and technological perspectives. Besides the modern roles of water in urbanism, its historical aspects are relevant. Blue urbanism has also been interpreted as an emancipatory phenomenon (Gandy Citation2004).

Blue urbanism as a cultural phenomenon is an extension of the concept of blue infrastructure. We use blue infrastructure as a concept to designate the physical and technological entities composed by water bodies and flows, forming a basis of blue urbanism. However, blue infrastructure, like green infrastructure (see Falkenmark and Rockström Citation2010; Young et al. Citation2014), often carries a natural scientific or technical interpretation which involves some limitations in perspective. We refer here to blue urbanism instead of infrastructures, in order to emphasize the sociocultural aspects and dynamic processes in the facilitation of environmental justice, including the relational values of blue infrastructure and associated ecosystem services (see Section 1) (Chan et al. Citation2016). Using the concept of blue urbanism we aim to capture city-wide social practices, necessary for the articulation, production and distribution of urban ecosystem services (Ernstson Citation2013) produced by blue infrastructure.

Studies of blue urbanism or of ecosystem services from blue infrastructure have been reported from many regions, including Europe (Ashley et al. Citation2013; Kabisch Citation2015), the USA (McPhearson et al. Citation2014), and beyond (Muñoz-Erickson et al. Citation2014). Many studies have focused on coastal cities (Depledge and Bird Citation2009; Earle Citation2010; Edwards et al. Citation2013), and the term blue urbanism has been mainly applied to city–ocean relations (Beatley Citation2014). Studies of ecosystem services from blue-green infrastructures in inland cities have also been published (Korpela et al. Citation2010; Völker and Kistemann Citation2011), while blue urbanism as an urban design challenge has been linked to water management and climate concerns (Hviid Citation2015). Besides literature explicitly on blue urbanism, relevant sources have been published under other terms such as blue space geographies (Foley and Kistemann Citation2015) or urban water more generally. We posit that blue urbanism is conceived differently due to local conditions, as shaped by nature as well as the cultures involving urban blue infrastructure.

Taking such a broad social-ecological view, blue infrastructures provide multiple ecosystem services: provisioning services (such as aquaculture), supporting services (such as living space for organisms), regulating services (e.g. local climate regulation by cooling), and cultural services including recreation, education, spiritual and aesthetic functions (Burkhard et al. Citation2010). These services are regularly twofold: for instance, fishing can provide food for sustenance as well as recreation, and ‘blue health’ benefits involve several of the above categories of services, especially as mental and social health and recreation are included. However, the ecosystem services are often not clearly and explicitly articulated, or cannot even be due to their indirect and ambiguous nature, which limits their role in many processes, also those striving to ensure environmental justice (cf. Ernstson Citation2013).

Like Beatley (Citation2014), we adopt a broad perspective on blue urbanism, emphasizing the role of blue structures especially through the possibilities to form a strong nature relationship in urban areas. We also consider that even small water bodies may have strong impacts on urban life and recreation, and remind of a connection to larger-scale water systems, not only in water-rich regions such as Nordic countries and coastal areas but even elsewhere.

2.2. Resilience and sustainability as societal properties

The concept of resilience has developed in ecology since the influential work of Holling (Citation1973) and is in common use within environmental management (McPhearson et al. Citation2014). Resilience has been defined generally as the time for a system to return to its original state and as the amount of disturbance a system can endure before shifting to an alternative state, in line with the dictionary definitions referring to ‘elasticity’ and ‘flexibility’ as synonyms.

Resilience as a social property has also been addressed for long (Lee Citation1980; Abson et al. Citation2014) and from varied angles, such as resilience to stress (Parker et al. Citation1990) and resilience thinking (Folke et al. Citation2010). In urban systems, resilience in social terms has been often analyzed in relation to social health (Wallace and Wallace Citation1997). Social resilience has been defined by Adger (Citation2000) as ‘ability of groups or communities to cope with external stresses and disturbances as a result of social, political and environmental change’, stressing the links between ecological and social resilience. An integral part of social resilience is encouraging open deliberation on perceived spaces and on underlying values, tied to specific locations in the urban landscape.

In this study focusing on blue urbanism in the context of environmental justice, we adopt a broad concept of resilience and sustainability. We emphasize the social-cultural dimension in the ecosystem services provided to its citizens (Burkhard et al. Citation2010; Dempsey et al. Citation2011), including service cascades, indirect impacts, multiple services and co-benefits (Primmer et al. Citation2015).

2.3. Environmental justice and the guiding concept of the others

We approach environmental justice as a socially construed principle, property or process consisting of procedural and distributive justice in being endowed with ecosystem services (Dobson Citation1998; Schlosberg Citation2004, Citation2013). We further conceive justice as recognition (a subject being recognized and having the right to recognize, as an autonomous agent).

(In)justice is contextually dependent, being shaped by the society and cultural region or epoch in question, even though they can be also claimed to have universal meaning and aspects (Rawls Citation1971). We similarly conceive of justice as something that has objective as well as subjective or intersubjective interpretations (see also Sen Citation2009).

Our notion of justice in more concrete and functional terms includes the enabling sequence of demands–obstacles–opportunities–knowledge. These situate justice in aspirations, empowerment and processes of engagement. As such, justice is a general principle underlying and emanating from the process of acknowledging demands, removing obstacles, and providing opportunities, as well as providing (options for gaining) knowledge ().

Figure 1. Simplified conceptual model of the key contents in the role chair exercise, structured according to the sequence of role chair questions and to their relationships with knowledge gaps.

Environmental justice involves the ethical and political question of reconciling special group needs with those of a broader community, and even those of humans in relation to non-human agents, which requires consideration of relational values (Chan et al. Citation2016) and of the multiple dimensions of environmental justice (Banerjee Citation2014). On the other hand, efforts to provide environmental justice can lead to contradictions if not seen from a broader perspective and thoughtfully merging social justice into the perspective, as explored by Dobson (Citation1998). For instance, reconciling sector interests and future and present needs, and resolving the trade-offs involved, requires such consideration (see Nesshöver et al. Citation2017).

2.4. Recognition, non-recognition and (un)knowns

We define knowledge as a context-dependent entity of multiple forms and origins (experts and lay) and multiple functions, and one overlapping with value judgments. As such, it involves societal and cultural processes of collective co-creation and interpretation, contestation and negotiation, in interaction with belief systems. This is particularly the case with knowledge which is based on subjective opinion, and with justice which is by definition value-dependent even in its universal principles. The importance of the values underlying facts (Putnam Citation2002) depends on the context and type of knowledge; in some cases objectivity is achievable to a higher degree (Assmuth and Hildén Citation2008).

Recognition is, quite literally, about cognition. We therefore distinguish several interacting levels of recognition, ranging from neutral ‘cognitive’ identification of agents and their interests and related issues, over evaluative reflection and increasingly ethical considerations such as allowing people a voice, to normative recognition which has to do with formal rights, as defined in Section 2.3.

These are key factors when blue urbanism is considered in a social context and in the interpretation of expert opinions. In essence, these opinions are then taken as tentative and relative recognitions or indications of the actual beliefs and core values of the experts, and still more so regarding the beliefs and values and of the population groups that these experts are set out to simulate and evaluate (cf. Section 3.) Gaps of knowledge thus exist both in the form of identified and expressed uncertainties and ambiguities as well as unstated but perceivable voids (unknown unknowns, .

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Involving experts to encourage and enrich recognition: a heuristic approach

There is a pronounced need to gain richer information on the ways experts and other actors recognize or do not recognize the needs, obstacles and opportunities of citizens to engage in the planning and management of their environment. Various participatory and involving methods have been developed in order to improve the recognition of various social and societal actors and actor groups (e.g., Preller et al. Citation2017). These methods have a key role to play in environmental justice due to the potential (though relative) neutrality of experts and the associated freedom from prejudice (as compared, for example, with groups having direct economic and other such stakes), coupled with their understanding of the conditions and needs of citizens in relation to blue structures.

It needs to be acknowledged that the neutrality and objectivity of experts and thus the insights and outputs they can provide are limited. They are often also members of groups of citizens of interest; their affiliations may cause (vested) interests and (unconscious) preferences, and even responsibilities for action; and like everyone (though presumably to a lesser degree) their opinions are conditioned by their values, being shaped by character, upbringing and the sociocultural environment, and reducing objectivity (cf. Putnam Citation2002).

On the other hand, the methodological challenges due to these traits also allow opportunities: rather than chasing illusory objectivity, expert opinions can be used on a heuristic approach as a means of framing issues and reflecting on their meaning, in a key step of open-ended knowledge co-creation. They can offer a powerful mix of neutrality and engagement. In particular, interaction with experts from other areas may broaden and revise framings.

In keeping with this approach, we used an exploratory heuristic expert opinion elicitation methodology to frame issues and allow recognition of the needs, obstacles and opportunities (‘the voice’) of citizen groups to engage with blue structures. The methodology aims at giving a voice to agents to improve and, initially, to clarify aspects of environmental justice. The method does so indirectly: rather than inviting the people concerned to give their voice, experts are employed to recognize their voices (‘echoes’). The difference between the voice and the echo is reduced by facilitating the recognition of citizen needs and conditions.

The starting point for the study was not that the experts would be easier to access or understand than the general public (though this may be the case in some respects), but rather that experts as a key group in environmental governance, planning and implementation can be led in new ways to reflect and communicate on opportunities for engagement with blue structures from the point of view of various groups. The underlying hypothesis was that experts usually tend to think of average users, instead of the variety in communities and contexts, whereby important aspects for environmental justice may be left aside. It was believed that experts on the other hand are able to generate insights in a process of collective learning that are not usually brought up, based on their experience. This is related to the goal of identifying deficits in the usual ways of issue recognition by experts.

Expert opinion elicitation also aims at drawing a representative, or at least a multifaceted and balanced, picture of the needs and conditions of citizen groups, without directly aiming at improvement of their rights. Thus, an ‘inward echo’ of the perceived voices of people toward the expert-driven processes of planning, decision-making, implementation, follow-up and R&D is also an important output. This represents an extension of the concept of recognition from the direct and normative to the indirect and cognitive level (cf. Section 2.4).

Such methods can also be used to channel the voice of various groups first only to authorities and by paying attention to the recognition of these actors make it possible to give them a say in future planning and decision-making. Expert opinion elicitation can thus act as an intermediary in dynamic multidirectional knowledge brokering and rights negotiation, feeding in to institutionalized processes to achieve feedback also to the relevant publics.

3.2. Role chair method

The material for the study was collected by a role chair experiment, a semi-structured, loosely guided and dynamic method of interactive expert opinion elicitation. It represents an informal brainstorming approach that deviates, for example, from conventional Delphi, focus group and other standard methods of human subject studies (Sackman Citation1974; cf. Wilkinson Citation1998; Parker and Tritter Citation2006). The role chair method has not been explicitly mentioned previously; methods that resemble it in some respects include ‘empty seat’ (Paivio and Greenberg Citation1995), ‘Fish Bowl’, ‘thinking hat’ (De Bono Citation1985) and ‘World Café’ (Aldred Citation2011; Ritch and Brennan Citation2010). Also drama and gaming techniques are increasingly used to enable identification with and recognition of the roles of others (Brouwer et al. Citation2017). We chose an innovative title to highlight the key function of facilitating a circulating and simulating ‘out-of-the-bubble’ recognition and representation.

We invited 22 experts with various backgrounds into the experiment in order to cover a wide range of opinions (). The experts were selected based on information on important organizations and other actors in the study area from the point of view of water-related ecosystem services. In some cases, such information was obtained in previous collaboration, in others by information searches. In yet other cases experts were suggested by the organizations themselves (cf. Müller et al. Citation2012). Organizations from public and private sectors and the civil society at large were approached, including specific (e.g. divers, boaters) as well as general-purpose organizations engaged in many aspects of blue infrastructures. Experts affiliated with various levels of governance from local to international and various substantive sectors were invited (). There is some overlap especially between sectors, and also some of the experts may be affiliated with or familiar with several levels and sectors, even presently and especially considering their entire professional career. Altogether 12 experts were present at the workshop.

Table 1. Characterizations of the expert group invited and employed by the level of governance and the primary sector of affiliation. The principal organizations have been underlined. From some organizations or categories of organizations, several experts were invited and participated.

The study focused on Helsinki Metropolitan Area that includes urban centers and peri-urban areas extending to a broader region, and blue structures in and around lakes and riparian environments as well as seaside settings (Laatikainen et al. Citation2015; Hietanen Citation2016).

The experts were asked to step into the shoes of population groups that are important for water-related uses of ecosystem services in the study area, and based on their prior knowledge interpret the positions of the groups while ‘sitting in a chair’ for the respective group addressed. This concrete symbol and mental image makes it easier to identify with the group in a similar way as, for example, the ‘hot seat’ or ‘empty chair’ techniques are designed to do.

The experts were prepared for the role chair session by giving a series of short presentations on (1) objectives of the research project, (2) aspects of environmental justice, (3) definitions of blue infrastructure and cultural ecosystem services, and (4) general contents and targets of marine spatial planning. Thereafter, the role chair experiment and its goals were explained.

In the role chair experiment, 12 partly overlapping segments (subpopulations) of the general population were assessed by the experts divided in smaller groups. These citizen groups represented a variety of important user groups for urban waters, based on their numbers and their special needs, capacities and roles: (1) School or kindergarten groups; (2) Youth; (3) Families with children; (4) Elderly persons; (5) Physically disabled; (6) Unemployed persons on welfare; (7) Dog-owners; (8) Recreational fishers; (9) Recreationists without cars (some of these may travel by bicycle); (10) Immigrant families; (11) Those not fluent in Finnish; (12) Artists. The idea was to stimulate thinking by bringing also less obvious user groups, such as artists, under discussion. The affiliation of an individual may change and frequently does so, for example, during their life course, while other group belongings are more static in their nature.

To structure the recognition exercise, the experts were asked to collectively identify and characterize (1) demands of subpopulation groups with regard to recreational uses of and engagement with blue infrastructure; (2) possible obstacles to using water areas equally with other population groups; (3) opportunities or means in improving the fulfillment of these demands; and (4) related knowledge needs to enable tackling the special demands or obstacles of use of the group. The experts were tasked to identify and discuss issues within these thematic entities for each group in turn. Altogether the discussion lasted for ca. 5 min per group in each thematic entity. As the discussion time was 5 min per each of the 12 groups of citizens addressed and the 4 thematic entities, 20 min (minimum) altogether for each group. While also this is short, such a pace was chosen to inspire rapid identification ‘off the top of the head’ and lively many-sided identification and discussion of issues. It should be noted that, as with many similar methods such as the World Café (Haywood et al. Citation2015), the total length of time devoted by the experts to reflection and discussion on any one citizen group and associated topics is deliberately kept small in order to stimulate rapid and unbridled ‘out-of-the-bubble’ elicitation of views.

Results were written in bullet points on flap boards (one for each of the 12 groups) during solicitation, and subsequently synthesized and digitalized by the facilitators. A list of different features of the blue infrastructure and cultural ecosystem service classes (according to CICES v.4.3) were attached on wall as a reminder during the role chair exercise to keep the focus of participants on the same topic throughout the exercise.

It should be emphasized that the role chair experiment was undertaken to encourage experts to brainstorm about key citizen groups in Helsinki Metropolitan Area potentially using its aquatic environments. The primary goal was thus to identify and frame issues and to generate and discuss ideas of demand, obstacles and opportunities in a collective process of deliberation and learning. We acknowledge that the results may not be the ‘truth’ about the roles and positions that these groups have, but are indirect and uncertain indicators for them, reflecting to a considerable extent the perceptions of the experts involved. This however constitutes the strength of the method. As these experts are key players in developing and applying the planning and decision-making processes for blue structures, their perceptions and opinions are essential. By combining the experts’ own insights with facilitated consideration of the particular conditions of citizen groups, we can potentially gain benefits from both perspectives.

3.3. Analysis of data and additional information

Based on the basic thematic entities (demands–obstacles–opportunities–knowledge gaps, ), we formed subcategories in an inductive manner, ensuring sensitivity to the articulated local conditions. The coding structure allowed for alternative and dynamic hierarchies and examination of relations between thematic entities, between different topics and between subpopulation groups. The digitalized results from the role chair session were coded for analysis by the NVIVO v.10 (QSR International Pty Ltd.) software for qualitative and mixed methods data analysis. In NVIVO, we developed a structured coding model (). The digitalized results from the role chair session were then thematically coded according to this structure. Each text segment responding to a code under the corresponding thematic entity was assigned to this code. The same text segment was also allowed to associate with several themes, although not to a code under a different thematic entity.

Table 2. Expert views on the demands, obstacles, opportunities and knowledge needs of the groups addressed with regard to blue-green infrastructure (BGI) use. The most commonly identified items have been underlined.

Table 3. Categorization of the main contents presented by the experts related to demands, obstacles and opportunities based on the primary data, including structuring subcategories defined by the authors. Note that knowledge gaps are included in all these categories. Identified links between various aspects have been indicated by lines.

This coding resulted in a numerical and binary matrix of codes, with the three thematic entities, demands, obstacles and opportunities, on one axis, and the 12 subpopulation groups on the other. Cluster analysis was then used to facilitate interpretation by reducing the expert opinions into themes, and by finding thematic association between groups.

The subpopulation links were examined by hierarchical cluster analysis. We ran complete-linkage clustering in NVIVO v.10, based on coding similarity using Pearson correlation coefficient as a tentative measure of similarity, acknowledging the limitations of such statistical criteria in the case of small qualitative datasets. The outcomes of the analyses were visualized in dendrograms. We used the dendrograms in combination with the similarity metrics as well as the source data in further interpreting the expert opinions, particularly regarding the ways they approached and recognized various citizen groups in relation to other groups.

We carried out this analysis of group closeness separately for each main thematic entity (demands, obstacles, opportunities) as well as for the three thematic entities as a whole. We chose not to analyze knowledge gaps as part of the whole data because of the different but embedded nature of this entity (see ). Aided by this structure, we additionally analyzed links between the thematic entities (demands, obstacles, opportunities and including the knowledge gaps).

4. Results

4.1. Recognition of demands, obstacles and opportunities to engage in blue-green infrastructure

We sum up the findings received by the role chair experiment in . We classify here the perspectives of experts according to the various subpopulation groups and to the thematic entities of demands, obstacles, opportunities and knowledge needs which the experts expressed the groups to have.

Overall, the importance of water and shore areas and blue infrastructure was considered, explicitly or implicitly, to be great for all groups and in many ways, such as by providing social cohesion, aesthetic pleasure, creativity and culture, touristic attraction, educational value, health benefits, potential sustenance (such as by edible fish), and direct or indirect economic benefits. It was also clearly considered a basic right of the citizens to engage with such blue infrastructure in ways suited to their needs.

4.2. Categorizing identified topics and clustering groups

For the analysis of the expert opinions, we additionally used a coding structure () that reflects the topics in the expert opinions, as well as in the literature on blue urbanism (see Section 2).

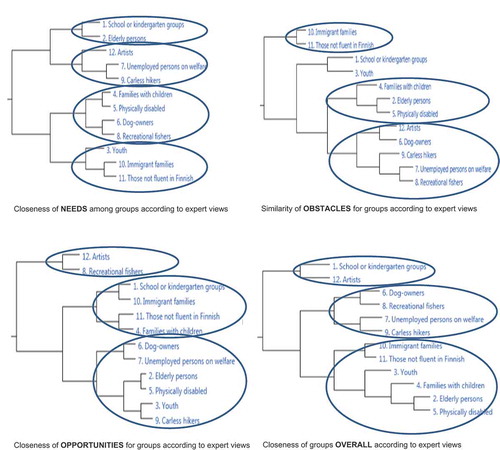

Subcategories under the four main entities related to facilitation and recognition of demands and opportunities were formed in a manner that could be expected based on a priori premises, such as for physical or basic needs, social and psychological needs, and general or hybrid needs; collective, personal and external obstacles; and ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ opportunities. The subpopulation groups in role chair data were clustered according to topic similarity of the expert opinions on the groups (). Additionally, we identified groups not having strong similarities with any other subpopulation groups, or only showing strong similarities with one or two subpopulation groups within its own cluster.

Figure 2. Clustering analysis of closeness between the groups based on expert opinions regarding the process stages in proving environmental justice in engagement with blue infrastructure, and overall (across all stages).

Considering the demands of various groups according to the experts (), we were able to arrange the responses to four clusters consisting of: (i) school and kindergarten children and elderly people (‘Tender-Agers’); (ii) artists, unemployed and carless recreationists (‘Wanderers’); (iii) a more ambiguous cluster consisting of two challenged groups and two active recreational groups (‘Special Needy’); (iv) another heterogeneous cluster which however has an obvious common trait (‘Relation Needy’, or ‘Guidance Needy’). Additionally, we identified the following particular groups: artists, the unemployed and immigrant families.

As to the perceived obstacles, we similarly obtained the following clusters: (i) ‘Strangers’ (to local blue urbanism, including recent foreigners and non-Finnish speakers, two heterogeneous clusters with various challenges); (ii) ‘Immobile’ and (iii) ‘Hindered’. Additionally, we identified the following particular groups: school and kindergarten groups and youth.

Regarding the opportunities identified for the groups, we obtain the following clusters: (i) ‘Freewheelers’ (fishers and artists); (ii) ‘Challenged’ (those challenged by age, ethnicity or language); (iii) again, a heterogeneous cluster with groups having various hindrances (cf. the clusters for obstacles, above) which may also be termed ‘Hindered’. For opportunities we also found that within the ‘freewheelers’ cluster the subpopulation groups have least in common with any of the other subpopulation groups.

It can be seen that these clusters overlap and thus also reinforce each other. This is reflected in the clusters for the whole sequence of demands–obstacles–opportunities (i.e. disregarding distinctions in these stages of enabling) for which the following aggregate groups could be discerned: (i) ‘Creative’ (children and artists); (ii) a cluster of four groups with various particular needs but also varying obstacles and reduced opportunities (‘Loiters’); (iii) ‘Challenged’, with more numerous and varied challenges.

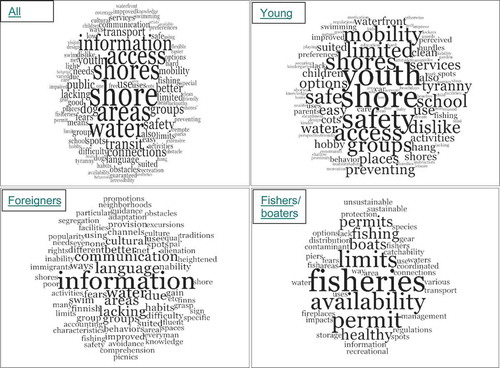

We further examined the occurrence of key words written by the experts on flap sheets using the world cloud technique to find out which terms were among the most common and central, for three clusters that repeatedly clustered together throughout the sequence, or that proved to be sensitive subpopulation groups, as well as for the whole data (). The results indicate that while there were shared terms used for all these groups, there were also marked differences. Safety considerations came up mainly for the aggregated group children and young; information was pronounced in the case of immigrants and non-Finnish speakers; and, fishing-related items were among the most common in the case of fishers and boaters.

4.3. Relationships between the topics identified and specific groups

The analysis reveals patterns of consistencies in demands, obstacles and opportunities as well as in knowledge gaps identified for the different groups. We present here qualitative findings for important aggregate groups clustering together throughout the sequence from demands to opportunities.

4.3.1. Age

Children were included in several of the subpopulation groups, most explicitly in school or kindergarten groups and in families with children. Particular needs, challenges and opportunities of children were consequently recognized by the experts on several occasions.

As expected, the experts also identified similar topics and issues in environmental justice for elderly people as for the physically disabled, such as handicapped persons or persons with disabling diseases or conditions.

Second, relationships between the different age groups were an important topic identified. The demands, obstacles and opportunities for children (kindergarten age), children in families, youth and elderly persons differed due to their particular conditions and abilities and to the environmental and social characteristics influencing their use of blue infrastructures. However, also some shared demands and opportunities were identified.

In the overall coding, issues identified by the experts for families with children were most closely related with those of the physically disabled, mostly due to similarities in the demands and obstacles of these groups. The need for built facilities (e.g. trails, bathing huts, toilets) to strengthen the quality of cultural ecosystem services is also present in both these groups. School and kindergarten groups tended not to form a strong correlation to any other group, while also having a diverse set of needs, such as those for play, guidance and elementary education, and not an extensive set of opportunities. They can therefore be identified as a group demanding special attention to receive just treatment and varied opportunities for engagement with blue structure.

4.3.2. Estrangement

The topics addressed in many cases tended to be similar for the group of immigrants and those not fluent in Finnish, as compared with the groups in the general population. However, also some particular aspects were discerned for these groups defined by origin, language or ethnicity.

The need for further information on present uses of blue infrastructure was identified for both immigrant families and non-Finnish speakers. However, it was acknowledged by the experts that there might be cultural differences affecting the use of blue infrastructure that others are not aware of. Also the heterogeneity within the groups was recognized. It seems that the experts assumed a bidirectional knowledge gap, that is, that immigrant families are unaware of native culture in relation to blue infrastructures. It also seems that the experts assumed this for all non-Finnish speakers, even if they could have their human–nature relationship formed in the study area. For both immigrants and non-Finnish speakers the experts recognized a need for recreation, and more commonly than for most other subpopulation groups (school and kindergarten groups aside) identified needs that are social. This included needs for guidance in the use of blue infrastructure.

The obstacles for both of these groups also span over more topics than for most of the other groups (again, schools and kindergarten groups aside). Within this entity we classified the responses based on three categories: inner, outer and collective (cf. ). The obstacles for immigrant families and non-Finnish speakers are mostly found in the collective category and not in the outer, the environment.

In the clustered data on the subpopulation groups, the immigrant families were perceived to be closest to non-Finnish speakers in recognized topics for the overall coding. Regarding opportunities, the closest subpopulation was that of school and kindergarten groups, not that of families with children as might be expected. Other issues than those related to children tended to shift the expert focus when immigrant families were addressed. Even if heterogeneity within the group was acknowledged, the age perspective was not evident.

4.3.3. Specific groups and types of recreational activities

Some of the sub-population groups are, according to the experts, conceptually far from each other. One group besides the school and kindergarten groups that merits special recognition with respect to access to and use of blue infrastructure are carless recreationists. Though active, they have limitations and challenges in access to and engagement in blue infrastructures and natural areas in general.

Among the groups engaged in recreational activities, fishers were identified in all thematic entities as an important group. Obstacles and opportunities for fishing were mentioned repeatedly, and also the importance and recognition of the quality of water bodies (and of fish stocks and fisheries) among this group was considered to be high. Foreigners were recognized as potential recreational fishers, and such groups may provide means to tap into knowledge and appreciation of ecosystem services and in environmental conservation even more influentially (cf. above, ethnicity).

It was interesting to note that some popular or particular recreational ways of engaging with blue-green infrastructure such as bird-watching and winter-time skiing on ice were not specifically mentioned by the experts.

Bicycles are a common way of reaching water in the Finnish context, both in recreational and commuting transport, and walking and biking are seen as the principal means of transport promoting environmental justice in Finnish cities. On the contrary, needing to have a car or another motorized vehicle except public transport to reach blue structure does not in our view meet the overall requirements of environmental justice (disabled people with, for example, electric mopeds are a different issue). We referred particularly to people without motorized vehicles in order to make the participants to take into account that accessibility and environmental justice need to be assessed based on people’s ability to reach the place on foot or by bicycle or by public transport. With regard to ‘carless people’ the point was that the respondents needed to live in a situation in which they were able to get to a wished place.

5. Discussion

5.1. Recognized and non-recognized demands, obstacles and opportunities

When analyzing expert opinions on demands, obstacles and opportunities of various citizen groups, we found that commonly mentioned topics include general items (such as access) and more abstract items (such as belonging) as well as specific (such as entryways) and concrete items (such as picnics). Overall, social-cultural as well as physical aspects were identified. Some items such as information were brought up commonly by the experts in all thematic entities, while others were more seldom recognized.

Some items, explicitly or rephrased, came up in several of the main thematic entities from demands to opportunities, reflecting their conceptual and functional linkages. Thus, what is seen as a demand (e.g. for information) is also mentioned, logically, among obstacles (lack of information) and among opportunities (provision of information), as well as in this case naturally among knowledge needs. Such repetitive or complementary perspectives serve to identify boundary concepts (Baggio et al. Citation2015) and internal consistencies between expert opinions. They may specifically function as control devices helping to form a coherent picture of the expert opinions which are limited by subjectivity as well as groups effects. They are also crucial in developing action strategies (including strategies for generation and use of information), even explicitly and directly for the development of a blue urbanism.

While some items (e.g. information) were recognized in the responses for several groups, some (e.g. permits for water area use) were recognized only in the connection with one or two groups. Items may be genuinely group-specific, although the so called everyman’s rights in Finland (MOE Citation2014) guarantee everyone the right to freely move and recreate in both public and private lands except in the immediate vicinity of buildings (thus also on shores), and national water legislation allows everyone to use water areas for swimming, rowing, etc. The sole exception is fishing where only angling and ice fishing are allowed free of charge and permit.

Synthesizing the results from the primary analyses (see Section 4), a progression was constructed through operational stages from demands over obstacles to opportunities, including identified and unidentified gaps of knowledge (). Knowledge needs are partly included in the other categories (especially those of demands and obstacles).

Figure 4. Results summarized and clustered according to the operational stages in fulfilling needs for blue structure, with recognized (explicit) and non-recognized (implicit) knowledge gaps in each. The former knowledge gaps are based on the role chair experiment, the latter have been identified by the authors. The items are generalized, combined and prioritized from those in .

While many demands, obstacles and opportunities for recreational uses of blue infrastructure were recognized and discussed in some detail by the experts, others were mentioned sporadically and superficially. This may be due in part to the time constraints in the experiment but may also suggest a more pervasive lack in recognition (cf. Lyytimäki et al. Citation2011). It is interesting that demands, obstacles and opportunities of quite different kinds came up, depending in part on the particular traits of the group considered. For instance, among obstacles for increased utilization of blue infrastructure the exaggerated demands for safety (of children) as well as for quietness (from the perspective of young people) were mentioned. These involve political questions of distributive justice, but differ from regulatory obstacles, being related to relations between different uses and user groups.

The information needs identified leave out some knowledge gaps which can be identified based on other premises, both within demands (e.g. the demand for broader social movements) as well as obstacles (e.g. economic and other such structural hindrances) and opportunities (the most efficient and acceptable means to promote blue urbanism). The identification of knowledge gaps apparently was not very extensive and analytical, since the experts were mainly concerned with practical measures and systematic production and use of knowledge was rather embedded in the practical aspects of demands, obstacles and opportunities.

5.2. Recognition of particular groups and their environmental justice issues

The role chair method focused on the recognition of demands and capacities of sub-populations. This included demands that are universal or specific, placing the groups in different constellations of commonalities for possibilities to achieve environmental justice and societal resilience. At the end of the continuum of diversity are individual traits (Raphael et al. Citation2001). There are subjective and group-induced limitations in framing and approaches and in resultant information and views, causing obstacles for recognition, but the lively brainstorming pace, the intense interaction between experts from different areas, and the object-oriented (citizen group oriented) mode of recognition and discussion in the role chair method helped to reduce such limitations.

The experts strove to identify themselves with the particular conditions of subgroups and also their roles in the community as a whole. Recognition of group needs and of their relations with others was therefore inherent, even if the relations, for example, in the form of conflicting interests were not systematically addressed (cf. Sander and Zhao Citation2015). Rather, the variability of water area users and of their needs was taken as a given, and this multiplicity including group relations was seen as something natural and valuable to uphold, and also as something providing opportunities for all in the region.

It was possible to discern aggregate clusters of citizens on the basis of the groups in focus by analyzing similarities and differences in the expressed needs and opportunities for them (). For instance, the linkages between the identified issues for the aged and the disabled suggests the possibility that by considering the latter it could also be possible to anticipate the needs and opportunities of the former, and vice versa.

The particular demands, obstacles and opportunities of foreigners, linguistically or ethnically or otherwise alienated from the main population and still in the process of integration, constituted an important finding (cf. Dahmann et al. Citation2010; Banerjee Citation2014). The challenges with such groups of blue-space users include information and guidance, sociocultural barriers to overcoming estrangement, as well as economic and physical factors. This has been noted also in Berlin (Kabisch and Haase Citation2014), with regard to the importance of small water bodies. On the other hand, immigrants and multicultural mixes may provide new approaches to and appreciations of blue space and new ways to manage it. The results in several cases suggest the harnessing of their particular resources for the whole population, such as providing cultural variety, complementary perspectives, mutual services and inputs for social learning.

The clusters are composed based on the experts’ perceptions, not iterated by representatives of social groups in questions, and thus are tentative and not definite. In addition, the clusters are not distinct but overlapping. Yet, despite uncertainties about their veracity and representativeness, they are able to highlight key characteristics with regard to the facilitation of environmental justice in their engagement with blue structure, and to guide processes of further reflection, communication and interaction, for example, as working simplifications. Complementing these broad clusters, particular traits of some specific groups were also evident, for example, with regard to demands and opportunities of age groups (cf. Finlay et al. Citation2015) and language or ethnic groups and are equally important in addressing the development of fair blue urbanism for these communities.

Many opportunities recognized are found in categories we classified as ‘soft’, for example, relations and information, and not among ‘hard’ opportunities. In addition to this, it was evident (though often not explicitly stated) that also ‘hard’ such as legal and economic realities define the demands and opportunities for these groups. The responses indicate that the experts were able to address environmental justice issues broadly. The experts also managed to articulate a sequence where specific distributive environmental issues were addressed. These included, for instance, the demand for picnic spaces for large groups; the lack of suited nearby shores; and the solution to avoid regional segregation and to facilitate group excursions.

In addition to the groups included in the role chair exercise, other groups engaged in recreational activities in or near water might be included, and were also represented by some of the organizations from which the experts were enlisted and even mentioned in the responses. Such groups include canoe paddlers and boaters, and swimmer and sun-bathers. Some of these, especially the bathers, are included in the general population as this is a very common water-related recreational activity, while others such as paddlers constitute a more distinct group and activity. Thus, the experiment forms a basis for processes of communicative governance (Skollerhorn Citation1998).

5.3. Meanings, goals and means of fair blue urbanism

The meaning of blue urbanism was seen in the context of the importance of blue space for affective and restorative environments (White et al. Citation2016), as well as an activating urban element, and thus for social welfare generally. The notion of blue urbanism traced in our study supports the view of ecosystem services as bundled entities involving complex relationships in space and time (Foley and Kistemann Citation2015), and complex relational values (Chan et al. Citation2016). An inclusive notion of blue urbanism is linked with environmental justice but also expands it to other areas of justice.

Justice and fairness in the engagement with blue infrastructure was addressed mainly indirectly by the experts, through the access to blue infrastructure that they considered the different population groups to have presently, with respect to what they considered to be needed and justified. This reference level of access would often be a standard for the subpopulation in question (such as an age group). Likewise, normative aspects in the distribution of the ecosystem services provided and in the affinity to water areas, which are not equal to the distribution of access, were often addressed by reference to equal rights to enjoy nature. Consideration of reasonable distribution was mainly inherent in the responses, and trade-offs between different goals, means and rights were not much addressed.

Based on the structure of the expert opinion solicitation, justice in the access to and engagement with blue structures was construed largely through the guiding themes of demands, obstacles and opportunities. Therefore, the normative aspect of what is fair was approached by considering what demands (physical, social and hybrid) are legitimate, what obstacles are unfair and surmountable, and what opportunities are reasonable to provide. In any case, there was reflection on blue-green justice instead of just blue-green environment (cf. Pearsall and Pierce Citation2010; Kabisch and Haase Citation2014). Regarding knowledge, the equal right to know, for example, about restrictions and opportunities to access water areas was mentioned, while responsibilities with regard to knowledge (including privacy) were more seldom implied.

The expert responses in general reflect a continuum from narrow, technical and administrative approaches to a broader and more open view where the concrete representations of citizen’s needs and opportunities are embedded in and conducive to a societal development process of blue-green urbanism. A part of that is the insight that unlike in traditional top-down steering, a bottom-up, experimental and multi-actor approach to the development of urban citizen society is increasingly needed to better achieve environmental justice in a sustainable society. These insights challenge also the traditional notion of expert as authoritative gatekeepers. Thus a role chair experiment requires but also allows that experts depart from their zone of familiarity, and recognize the importance of multiple perspectives, forms of knowledge, and ways of engagement (Vierikko and Niemelä Citation2016).

5.4. Contextualization and generalization of the results

According to the expert responses, Helsinki Metropolitan Area seems to offer rich and varied opportunities for access to and engagement with blue-green infrastructure, also for particular groups of the population, but also significant limitations and challenges to utilize and to preserve opportunities for such engagement. The balance of obstacles and opportunities has been studied in this region also using GIS methods (Laatikainen et al. Citation2015). These challenges correspond to the multiple layers of accessibility noted elsewhere in planning contexts by Ferreira and Batey (Citation2007).

Comparison of the region with others was not a goal of the experiment, and neither was a discussion attempted of how great the obstacles in engagement with blue-green infrastructure are with respect to other problems in the region or elsewhere (see e.g. Korpela et al. Citation2010). The particular characteristics of the Helsinki Metropolitan Area with regard to both blue-green structures and to socioeconomic and legal factors such as everyman’s rights (see above) should be taken into account in international comparisons. It can however be said in general terms that our results support the notion that especially for some deprived groups improved contact with blue infrastructure may be an important factor of well-being (Foley and Kistemann Citation2015; Völker and Kistemann Citation2011).

As to the time dimension, while the assessment of trends in the provision of ecosystem services by blue infrastructure was not an explicit task of the experts, some positive as well as negative developments were identified, also with regard to environmental justice in such provision, for example, with regard to increased demand from the elderly and from immigrant populations. The time dimension is important also with regard to the dynamics of blue urbanism as a sociocultural and urban development process. It has been shown in other studies that the place attachment is influenced by the sense of urban change (von Wirth et al. Citation2016). A balance between healthy change and one which feels uncontrollable and detrimental is essential.

The representativeness of the expert opinions elicited by the role chair method cannot be established through comparison with other methods or with direct information on the opinions of the citizen groups concerned, which limits the generalizability of the results. The aims of the present study were more modest, being focused on the framing, identification and initial exploration of issues. Nevertheless, the structure of the inquiry, being based on a sequence of engagement from needs to opportunities and allowing internal checks, as well as the sample of experts and the mode of group interaction do allow initial general conclusions, as discussed in Sections 5.1 and 5.5 in relation to methodological aspects.

5.5. Methodological considerations and future possibilities

The collective reflection on others makes the experiment different from the ‘empty chair’ method used in individual psychology (Paivio and Greenberg Citation1995). The method also differs from the hot seat or Fish Bowl methods where individual participants in turn take on the task of simulating some person, group, reality or issue. The difference is even greater from regular focus groups consisting of actual members of the groups whose conditions and choices are under study (Wilkinson Citation1998). While our participants reflected on the position of others, they interpreted such positions from their expert perspective.

The results were based on the experiences of the participating experts, reflecting their perceptions, values and traits and their interactions (cf. Hollander Citation2004; Parker and Tritter Citation2006). In a role chair method emphasizing envisioning and emotional engagement, it is important to avoid prejudices about the demands of the groups emulated, as well as overly specific notions of demands that are universal for humans. In this regard, the representativeness of the results could be evaluated only partly. On the other hand, in such an exploratory and semi-open method much of the point is achieving free and unconditioned (as far as possible) brainstorming and also a link with other (future) activities of the participants, instead of a representative psychological study.

The lay and expert views and in-group and collective views were mixed, as the experts identified themselves with the various groups and also with their own backgrounds and affiliations which may strongly influence the views, for example, among advocacy groups or sector authorities. This causes ambiguity but also enables a variety of views, broad communication and interaction, and learning from other fields (Skollerhorn Citation1998), and interactive cogeneration of knowledge (Preller et al. Citation2017). In essence, the role chair approach may thus strike a balance between the detached quasi-objective expert view on citizen groups and a deeper recognition and understanding of ‘first-hand’ views and realities of these groups.

As we did not document what accounts or responses were produced by which expert, the consistency and other relations of opinions could not be analyzed rigorously (cf. Kidd and Parshall Citation2000). Likewise, more detailed information on the communication process, including nonverbal communication, was not recorded. Thus, how things were said could be elusive and the collective process of opinion formulation was fuzzy. Further, as specific information on the participating experts was not systematically collected, analysis of their traits and backgrounds could not be investigated, also restricting studies of the motivations and bias of experts. Such identifiable gaps can be filled in by follow-up studies, including besides repeated and in-depth group (and individual) discussions using a similar methodology, other approaches such as regular Delphi, World Café, affinity diagramming (Yasuhara et al. Citation2015), as well as, notably for the purposes of representation and identification, drama and gaming (for a recent extensive evaluation of such and other participatory and interactive methods, see Brouwer et al. Citation2017).

There are notable strengths in the method used, too. In essence, it allows an open, creative and dynamic process where the insights and capacities of participants are well utilized and where a collective learning process can come into its own. For instance, the limited amount of experts allowed more interaction, which was further enabled by dividing them in smaller groups. In an exploratory and action research study, this is more important than statistical rigor. In general, it seems that many of the weaknesses and limitations of the method, such as its rapid, open and informal conduct, carry some of its main strengths, potentials and benefits. Using the heuristic-discursive method, the objective is not to let the experts extract representative and invariant truths, but plural interim views and interpretations in a collective deliberation process. For this end, the method can also be flexibly combined with other approaches and objectives such as brainstorming in learning, planning and negotiation contexts, where the key is to initiate a non-egocentric deliberation process sensitive to the condition of particular groups, as well as with more rigorous also quantitative methods of expert (and stakeholder or decision maker) opinion elicitation. Overall, it seems as an interesting possibility to develop further in the elicitation of opinions of experts as well as other groups.

Future needs and opportunities thus include the following:

further analysis of the results, such as more extensive and detailed clustering across groups and themes;

follow-up studies and experiments with the experts enlisted, including inquiries into their backgrounds, motives and values as well as analysis of the potential learning process regarding recognition encouraged by the role chair experiment;

complementing the initial modified World Café style role chair method with other facilitated group learning methodologies, both formal and informal;

combining local studies based on expert opinions with representative surveys (see e.g. Schipperijn et al. Citation2010); and, in a more applied way;

comparing discovered expert perceptions of the demands, obstacles and opportunities with the perceptions of the representatives of the recognized social groups themselves, and exploring the reasons for potential discrepancies between the two and their reflections on participation in planning and decision-making;

linking the present study in relevant communication, planning, management and other collaborative processes in the case area (cf. Metzger and Lendvay Citation2006; Ashley et al. Citation2013).

in-depth studies of the distributional, procedural and relational justice of urban blue-space, theoretical as well as empirical (cf. Walker Citation2010).

In all these areas, attention to the particular demands, opportunities and conditions of specific population groups and their relations with the overall community are crucial for socially grounded and truly sustainable environmental justice; and therefore improved recognition of the knowledge and experiences of these groups as legitimate actors is equally crucial.

Acknowledgments

We would like to particularly thank M.Sc. Riina Pelkonen for participating in the empirical part of the work. We also acknowledge the Academy of Finland for funding the project ENJUSTESS (263403) as a part of the Academy Program on Sustainable Governance of Aquatic Resources (AKVA) and the BRO project (304515) as a part of the Key project funding ‘Forging ahead with research’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timo Assmuth

Timo Assmuth is environmental scientist and works as senior researcher in Finnish Environment Institute, specializing in wastes, chemicals and risks, health, water, psychology, communication, policy and science studies. He also serves as docent at the University of Helsinki.

Daniela Hellgren

Daniela Hellgren is environmental planner and works an spatial analyses of urban infrastructure, now in municipal administration. She has a background in geo-informatics, natural resources management and regional development.

Leena Kopperoinen

Leena Kopperoinen is geographer and environmental scientist and works as senior researcher at SYKE where she leads and conducts projects in urban blue and regional blue-green infrastructure and ecosystem services, specializing in ecosystem services mapping and assessment especially in relation to sustainable land use and spatial planning.

Riikka Paloniemi

Riikka Paloniemi works as leader of SYKE's Green Infrastructure Group. She is environmental scientist and specializes in forest policy and nature protection.

Lasse Peltonen

Lasse Peltonen is professor of environmental conflict resolution at the University of Eastern Finland. He has a PhD degree in regulatory studies. He worked previously in the University of Tampere, Aalto University and Finnish Environment Institute. He is also the founder of Akordi Oy specializing in environmental conflict management and negotiation.

References

- Abson DJ, von Wehrden H, Baumgärtner S, Fischer J, Hanspach J, Härdtle W, Heinrichs H, Klein AM, Lang DJ, Martens P, et al. 2014. Ecosystem services as a boundary object for sustainability. Ecol Econ. 103:29–37.

- Adger WN. 2000. Social and ecological resilience: are they related? Prog Hum Geogr. 24:347–364.

- Aldred R. 2011. From community participation to organizational therapy? World Cafe and Appreciative Inquiry as research methods. Commun Dev J. 46(1):57–71.

- Ashley R, Lundy L, Ward S, Shaffer P, Walker L, Morgan C, Saul A, Wong T, Moore S. 2013. Water-sensitive urban design: opportunities for the UK. Proc Inst Civil Eng Municipal Eng. 166:65–76.

- Assmuth T, Hildén M. 2008. The significance of information frameworks in integrated risk assessment and management. Environ Sci Pol. 11:71–86.

- Baggio JA, Brown K, Hellebrandt D. 2015. Boundary object or bridging concept? A citation network analysis of resilience. Ecol Soc. 20(2):2.

- Banerjee D. 2014. Toward an integrative framework for environmental justice research: a synthesis and extension of the literature. Soc Nat Resour. 27:805–819.

- Beatley T. 2014. Blue urbanism: exploring connections between cities and oceans. 2nd ed. Washington (DC): Island Press; 214 p. ISBN-13: 978-1610914055.

- Blake NM. 1956. Water for the cities: a history of the urban water supply problem in the United States. Syracuse (NY): Syracuse University Press; x+341 p.

- Brouwer H, Brouwers J, Hemmati M, Gordijn F, Mostert RH, Mulkerrins J. 2017. The MSP tool guide: sixty tools to facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships. Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen University and Research; 148 p. http://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/409844.Accessed date 29 August 2017.

- Brown G, Kyttä M. 2014. Key issues and research priorities for public participation GIS (PPGIS): a synthesis based on empirical research. Appl Geogr. 46:122–136.

- Burkhard B, Petrosillo I, Costanza R. 2010. Ecosystem services – bridging ecology, economy and social sciences. Ecol Complex. 7:257–259.

- Chan KMA, Patricia Balvanera P, Benessaiah K, Chapman M, Díaz S, Gómez-Baggethun E, Gould R, Hannahs N, Jax K, Klain S, et al. 2016. Opinion: why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 113:1462–1465.

- da Silva J, Kernaghan S, Luque A. 2012. A systems approach to meeting the challenges of urban climate change. Int J Urban Sust Dev. 4:125–145.

- Dahmann N, Wolch J, Joassart-Marcelli P, Reynolds K, Jerrett M. 2010. The active city? Disparities in provision of urban public recreation resources. Health Place. 16:431–445.

- De Bono E. 1985. Six thinking hats. Boston (MA): Little, Brown and Company. See also: Toronto (ON): MICA Management Resources, 1985.

- de Groot RS, Alkemade R, Braat L, Hein L, Willemen L. 2010. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol Complex. 7:260–272.

- Debbané A-M, Keil R. 2004. Multiple disconnections: environmental justice and urban water in Canada and South Africa. Space Polity. 8:209–225.

- Dempsey N, Bramley G, Power S, Brown C. 2011. The social dimension of sustainable development: defining urban social sustainability. Sust Dev. 19:289–300.

- Depledge M, Bird W. 2009. The Blue Gym: health and wellbeing from our coasts. Mar Pollut Bull. 58:947–948.

- Dobson A. 1998. Justice and the environment: conceptions of environmental sustainability and dimensions of social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Earle S. 2010. The world is blue: how our fate and the ocean’s are one. Washington (DC): National Geographic.

- Edwards PET, Sutton-Grier AE, Coyle GE. 2013. Investing in nature: restoring coastal habitat blue infrastructure and green job creation. Mar Pol. 38:65–71.

- Ernstson H. 2013. The social production of ecosystem services: a framework for studying environmental justice and ecological complexity in urbanized landscapes. Landsc Urban Plann. 109:7–17.

- Falkenmark M, Rockström J. 2010. Building water resilience in the face of global change: from a blue-only to a green-blue water approach to land-water management. J Water Resour Plann Manage. 136:606–610.

- Ferreira A, Batey P. 2007. Re-thinking accessibility planning: a multi-layer conceptual framework and its policy implications. Town Plann Rev. 78:429–458.

- Finlay J, Franke T, McKay H, Sims-Gould J. 2015. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health Place. 34:97–106.

- Floyd MF, Johnson CY. 2002. Coming to terms with environmental justice in outdoor recreation: a conceptual discussion with research implications. Leisure Sci. 24:59–77.

- Foley R, Kistemann T. 2015. Blue space geographies: enabling health in place. Health Place. 35:157–165.

- Folke C, Carpenter SR, Walker B, Scheffer M, Chapin T, Rockström J. 2010. Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol Soc. 15:Art. 20.

- Gandy M. 2004. Water, modernity and emancipatory urbanism. In: Lees L, editor. The emancipatory city? Paradoxes and possibilities. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications; p. 178–191.

- Gómez-Baggethun E, Barton DN. 2013. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol Econ. 86:235–245.

- Hampton G. 1999. Environmental equity and public participation. Policy Sci. 32:163–174.

- Hayden L, Cadenasso ML, Haver D, Oki LR. 2015. Residential landscape aesthetics and water conservation best management practices: homeowner perceptions and preferences. Landsc Urban Plann. 144:1–9.

- Haywood K, Brett J, Salek S, Marlett N, Penman C, Shklarov S, Norris C, Santana MJ, Staniszewska S. 2015. Patient and public engagement in health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes research: what is important and why should we care? Findings from the first ISOQOL patient engagement symposium. Qual Life Res. 24(5):1069–1076.

- Hietanen M. 2016. The diversity of recreational opportunities in Helsinki based on the recreation opportunity spectrum method [ M.A. thesis]. Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki. 120 p. Finnish.

- Hollander JA. 2004. The social contexts of focus groups. J Contemp Ethnogr. 33:602–637.

- Holling CS. 1973. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Ann Rev Ecol Syst. 4:1–23.

- Hviid C. 2015. Blue urbanism: rethinking rain conference notes. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/blue-urbanism-rethinking-rain-conference-notes-christian-hviid-cfa. Accessed date 29 August 2017.

- IHP. 2006. Urban water conflicts. An analysis on the origins and nature of water-related unrest and conflicts in the urban context. Geneva, Switzerland: UNESCO. ICP (International Hydrological Programme) – UNESCO, Coll. Working Series SC-2006/WS/19.

- Jorgenson J, Steier F. 2013. Frames, framing, and designed conversational processes: lessons from the World Café. J Appl Behav Sci. 49(3):388–405.

- Kabisch N. 2015. Ecosystem service implementation and governance challenges in urban green space planning—the case of Berlin, Germany. Land Use Pol. 42:557–567.

- Kabisch N, Haase D. 2014. Green justice or just green? Provision of urban green spaces in Berlin, Germany. Landsc Urban Plann. 122:129–139.

- Vierikko K, Niemelä J. 2016. Bottom-up thinking—identifying socio-cultural values of ecosystem services in local blue–green infrastructure planning in Helsinki, Finland. Land Use Pol. 50:537–547.

- Kidd PS, Parshall MB. 2000. Getting the Focus and the group: enhancing analytical rigor in focus group research. Qual Health Res. 10:293–308.

- Korpela KM, Ylén M, Tyrväinen L, Silvennoinen H. 2010. Favorite green, waterside and urban environments, restorative experiences and perceived health in Finland. Health Promot Int. 25:200–209.

- Laatikainen T, Tenkanen H, Kyttä M, Toivonen T. 2015. Comparing conventional and PPGIS approaches in measuring equality of access to urban aquatic environments. Landsc Urban Plann. 144:22–33.

- Lee TR. 1980. The resilience of social networks to changes in mobility and propinquity. Soc Netw. 2:423–435.

- Lyytimäki J, Assmuth T, Hildén M. 2011. Unrecognized, concealed, or forgotten – the case of absent information in risk communication. J Risk Res. 14(6):757–773.

- McGranahan G, Marcotullio P (coordinating lead authors). 2005. Millennium ecosystem assessment, current state & trends assessment (condition working group co-chairs Rashid Hassan and Robert Scholes). Washington, DC: Island Press for UNEP. Chapter 27, Urban systems; p. 797–825.

- McPhearson T, Hamstead ZA, Kremer P. 2014. Urban ecosystem services for resilience planning and management in New York City. Ambio. 43:502–515.

- Metzger ES, Lendvay JM. 2006. COMMENTARY: seeking environmental justice through public participation: a community-based water quality assessment in Bayview Hunters Point. Environ Pract. 8:104–114.

- MOE. 2014. Everyman’s right. Helsinki: Ministry of the Environment; [published 2013 Aug 1; accessed 2014 Dec 9]. http://www.ym.fi/en-US/Latest_news/Publications/Brochures/Everymans_right(4484).

- Müller MO, Groesser SN, Ulli-Beer S. 2012. How do we know who to include in collaborative research? Toward a method for the identification of experts. Eur J Oper Res. 216(2):495–502.

- Muñoz-Erickson TA, Lugo AE, Quintero B. 2014. Emerging synthesis themes from the study of social-ecological systems of a tropical city. Ecol Soc. 19:23.

- Nesshöver C, Assmuth T, Irvine K, Rusch G, Waylen K, Delbaere B, Haase D, Jax K, Jones-Walters L, Keune H, et al. 2017. The science and practice of nature-based solutions: an interdisciplinary perspective. Sci Total Environ. 579:1215–1227.

- Paivio SC, Greenberg LS. 1995. Resolving “unfinished business”: efficacy of experiential therapy using empty-chair dialogue. J Consult Clin Psychol. 63(3):419–425.

- Parker A, Tritter J. 2006. Focus group method and methodology: current practice and recent debate. Int J Res Method Educ. 29:23–37.

- Parker GR, Cowen EL, Work WC, Wyman PA. 1990. Test correlates of stress resilience among urban school children. J Prim Prev. 11:19–35.

- Pearsall H, Pierce J. 2010. Urban sustainability and environmental justice: evaluating the linkages in public planning/policy discourse. Local Environ. 15:569–580.

- Preller B, Affolderbach J, Schulz C, Fastenrath S, Braun B. 2017. Interactive knowledge generation in urban green building transitions. Prof Geographer. 69(2):214–224.

- Primmer E, Jokinen P, Blicharska M, Barton DN, Bugter R, Potschin M. 2015. Governance of ecosystem services: a framework for empirical analysis. Ecosystem Serv. 16:158–166.

- Putnam H. 2002. The collapse of the fact/value dichotomy and other essays. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

- Raphael D, Renwick R, Brown I, Steinmetz B, Sehdev H, Phillips S. 2001. Making the links between community structure and individual well-being: community quality of life in Riverdale, Toronto, Canada. Health Place. 7:179–196.

- Rawls J. 1971. A theory of justice. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

- Ritch EL, Brennan C. 2010. Using World Café and drama to explore older people’s experience of financial products and services. Int J Consum Stud. 34(4):405–411.