ABSTRACT

This article examines land readjustment program as a tool to alleviate the arbitrary development of New Urban Land Expansion in Egypt. Also, it explores Participatory and Inclusive Land Readjustment (PILaR) as a mechanism to shorten the gap between the current Egyptian planning policy with its regulations and requirements and the existing reality of people’s needs and demands. Draw from a case study in Benha city, this article assumes that PILaR can be formulated and implemented on the ground with ‘technical enablement.’ The gap between the government policy and the capacity of the community should be narrowed to identify what is of critical importance and what is required for people concerned. The government should adopt PILaR and act as an agent for the avail of local citizens and for the compatibility and sustainability of rescuing agricultural lands and encourage the urban development in the back desert of Egypt.

1. Introduction

In early 2006, the Egyptian government introduced an official planning process through setting up a General Strategic Urban Plan (GSUP) for Egyptian cities. GSUP is based upon a participatory approach in drawing up a new urban boundary for those cities to fulfill the citizens’ future needs and to avoid further encroachment on agricultural land within the next two decades (GOPP Citation2006). The main output of this scheme is the Detailed Plan for New Urban Land Expansions (DPNULE) in the Egyptian cities. Subsequently, with the implementation of the GSUP for 331 cities, 4632 villages, and 27,000 hamlets, it is expected that Egypt will formally lose a total of 334,660 feddan (Toth Citation2009; Soliman Citation2014) (one feddan is equivalent to 0.42 ha) of agricultural areas within the next two decades. If this trend continues, Egypt will formally lose two-thirds of its agricultural land, around five million feddan in Delta, within nearly 200 years.

In the late of 2013, UN-Habitat in cooperation with the General Organization of Physical Planning (GOPP) at the Ministry of Housing has formulated a technical team (TT)Footnote1 to apply land readjustment program (LRP) for the DPNULE. Within this scope, the TT has been trying to understand the underlying issues in developing the LRP, using Geographic Information System (GIS) tools. The main objective of this research is to examine LRP as a tool to alleviate the arbitrary development of New Urban Land Expansion in Egypt. Also, it explores Participatory and Inclusive Land Readjustment (PILaR) as a mechanism to shorten the gap in current Egyptian planning policy, its regulations, and its requirements from one side and the existing reality of people’s interests, needs, and demands from other side. State’s regulations, market, and social network are discussed to investigate the link between social networks and LRP, by which inclusive serviced land can be achieved. The aim was to propose recommendations to reform Egyptian planning policy.

Accordingly, this article sheds light on the assumption that LRP can be formulated through a participatory inclusive process at the local level with ‘technical enablement’ that facilitates the implementation of the DPNULE based on LRP if the main obstacles could be solved. This would highlight everyone’s rights to own property, through semiformal security of tenure, which is a fundamental component in the LRP. Applying LRP process would also eliminate informal housing development inside and outside formal planning zones and promote guided formal urban development in the Egyptian desert.

This article focuses on El Rezqa area, located in the northwestern part of Benha city which is located approximately 45 km north of Cairo, Egypt’s capital. This case study is the first project to be implemented in Egypt based on LRP. It helps explain both the processes and the outcomes of the LRP through the author’s engagement in the process, participant observation, community participation, reconstruction, and analysis of the data obtained through several meetings held with the stakeholders.

The planning methodology depended on various methods, principles, and values. To test a participatory inclusive process based on LRP for the DPNULE, as a possible approach for creating serviced land, the study set out to develop three scenarios. The idea here is to demonstrate using scenario analyses that there are ‘quality of life gains and financial wins’ with LRP. In the former, landowners could be willing to have an urban pattern that would match their needs and reflect their cultural identity and everyday urban life. In the latter, landowners would have the privilege of having an official serviced land plots that obey the prevailing law by which land value would increase. It became clear that while landowners could be willing to swamp their land for a smaller piece of serviced land, they simply would not take ‘land value’ for a commodity exchange or capital exchange. On the other hand, formal non-comprehensive land to land readjustment (LR) is realizing the potential development value of landowners’ land, and landowners are eager to build and capitalize on this value. However, landowners also realized the importance of planning a better-built environment.

The rest of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 explores the research methodology. Section 3 briefly examines social networks, LRP, and PILaR. Section 4 examines Egyptian context, while Section 5 explores the participatory inclusive processes. A concluding section summarizes the key issues and directions for tackling the challenges of the DPNULE. The article concludes a participatory inclusive process with ‘technical enablement’ that would facilitate LRP for the urban poor in a sustainable manner. The government should act as an agent for the sake of local citizens and for compatibility and sustainability to magnify the political goal of rescuing agricultural land and to encourage the sustainability of urban development in the back desert in Egypt.

2. Research methodology

Knowing the challenges of the government-sponsored detailed plan and landowners’ initiated subdivision, this study aimed to find a way in which the only goal is not profit maximization but building healthy neighborhoods rich in services instead. This would provide a better quality of life. It is important to understand this framework to develop a methodology that could challenge the illegal construction on urban land expansion. Since the building and planning law number 119 of 2008 (BPL119) does not provide a functional way for transforming the lands into ‘buildable plots,’ landowners attempt to take the matter into their own hands and, consequently, they build informally. Also, semiformal DPNULE has managed to develop and transfer farmland use to urban use and is taking place, extensively, in the peri-urban interface of Egyptian cities, by which AshwaiyyatFootnote2 flourished and constituted more than 50% of the Egyptian landscape (Sims Citation2010; Soliman Citation2014).

This research applies a deductive methodology to test concepts and patterns known from theory using new empirical data. Theoretically, there is a huge literature questioning the LRP, the level of informal land development, and the role of social networks within informal areas. Practically, the author examines the linkages between informal land development, with some sort of security, treating land as a use and/or an exchange value or both, and the way it has created, developed, and invested. The differentiations between cost, value, and benefits of serviced planned land are essential on the ground. The research covers a case study of El Rezqa area in Benha city, north of Cairo. Through case study method, using GIS tools, the TT understands the spatial conditions through participant observation, and the exploration and understanding of complex issues are raised. Case study method helps to explain both the process and the outcome of LRP through complete observation, evaluation, comparison, and analysis of the case under investigation.

A field survey was carried out to investigate the spatial status quo of the site, formal/informal land markets’ mechanisms, the number of landowners, the number and size of land parcels, the available cadastral maps, the available planning draft maps of the site, and official/unofficial documentation for land title. The process took 18 months (December 2013 to June 2015) and was managed through field survey, desk work, 4 workshops, and around 25 meetings with the stakeholders. Forty-eight landowners participated, and 17 experts were attending various meetings. Nine of whom were experts in the local academia, six from the local authority, and extra two experts from the GOPP. A spreadsheet was designed to organize and track the process of data collection, analysis, and any comments given by experts and stakeholders.

The field survey consisted of two rounds. Round 1 conducted physical land surveys in which the number of landowners and their properties were identified. Several trips were made to the site to identify the main physical features, size, and number of existing land parcels; vacant or agricultural land; existing residential buildings; various land tenure documentations, registered/none registered; and available cadastral maps. All information and documentations were recorded in CAD and GIS format by which several maps and layers of the existing situation of the site were produced.

Round 2 conducted the verification of the parcel sizes with the government’s cadastral documents in which relevant paperwork was filled out at the Segel Ainy Department within the Real Estate Publicity Authority (REPA). One of the main challenges at this stage was that the REPA does not have parcel maps that show ownership of the entire area. Instead, the REPA has individual files for each superblock and parcel. Thus, tracing ownership and transactions of a property has been quite difficult, as the data at the REPA is outdated. Ninety percent of lands in Egypt are not officially registered with the REPA. A comparison between what are really existed on the ground and what is officially recorded at the REPA has been fulfilled. The latest cadastral map that the Land Survey Authority (LSA) in Benha that could be provided was from 1933, at a 1:2500 scale in which the entire site was still one piece of agricultural land or superblock (Hoaad).

3. Social networks, inclusive processes, LR, and PILaR

The community participation in housing process was explored in several classical books by Turner and Fichter (Citation1972), Turner (Citation1976), Fathy (Citation1972), Alexander et al. (Citation1975), and Hasan (Citation2001), while organization studies were elaborated in Bourdieu’s (Citation1977) work. Turner (Citation1976) expressed social networks in the form of three laws of freedom to build in accelerating informal housing production. Understanding how social networks contribute to the economic and social fabric of life in developing countries is important (Woolcock and Narayan Citation2000; Collier Citation2002). Social solidity is essential for societies to flourish economically and for development to be sustainable (Adler and Kwon Citation2002). The interdependent nature of stakeholders or users (where stakeholders are the individuals within a network) is a key distinguishing characteristic of a social network, while stakeholders’ structures, connectivity, and the distribution of power are key components of marketing systems (Layton Citation2009; Jackson Citation2010). It is argued that (Collier Citation1976; Perlman Citation1976; Ward Citation1982; De Soto Citation1989; Fawaz Citation2008) the formation of informal settlements during the 1970s and 1980s was organized and managed through wide webs of social networks. Also, social networks depend on symbolic capital by which reflects a ‘capital of honor and prestige’ (Bourdieu Citation1977). Hamdi (Citation2004) argued that the guru of urban participatory development is looking for ways of connecting people, organizations, and events of seeing a strategic opportunity. This means acting practically (locally, nationally, and globally) and thinking strategically and acting strategically (locally, nationally, and globally) and thinking practically. While, it is not doing either/or but doing both, and doing it perfectively, participatory, and progressively. It is argued (Soliman Citation2012) that social networks have assisted the poor in relying on their own efforts, participation, and local savings that have facilitated the purchase of housing plots at reasonable prices. Social networks also have assisted the formulation of their urban setting at the affordable basis. This was argued by Engles’s (Citation1970) statement: ‘The “working people” remain the participatory owners of the houses, factories, and instruments of labor, and will hardly permit their use … by individuals or associations without compensation for the cost.’ The former has often been viewed as a negative modification resulting in increased fear and isolation, while the latter has been viewed as a participatory response in which individuals act jointly to undertake joint activities that they could not accomplish on their own (Barker and Linden Citation1985).

The provision of property rights to residents of low-income settlements became a central theme for a social network, as the best way is to accelerate their corporation into the completely housing system or land market system. This paradigm has become so significant within multilateral agencies that housing and land issues are mentioned in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in relation to part 1 of Goal 7 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. However, not only security of land tenure has become the sole pointer, but also land market mechanisms that facilitate land delivery system became crucial.

In the field of shaping the environment, Soliman (Citation1985) found that informal settlements operate at least partly outside the official system through local planning convention that depended on four aspects of social networks in squatters’ settlements in Egypt. First, the presence of a hierarchy of use, meeting spaces, and physical layout are significantly related to social, economic, and climatic considerations. Second, the pattern and the space forms were created by the residents themselves without government or professional intervention. The settlers were their own architects who formed their settlement according to their needs and requirements. Third, the residents constituted self-reliant communities, where people decide together how to shape their common destinies which are representing the principles of the social networks. Fourth, the hierarchy of circulation systems within informal housing areas is reflected the citizens’ cultural and traditional ties. The result was a traditional rural pattern that matches the citizens’ area of origin with a variation of spatial proportion relating to street widths, building facades, and a hierarchy of space with limited access. On the other hand, the government’s thought was that the above system operates in a certain way. While in practice, it operates according to its own social networks and the government systems fail to engage and consequently fail to work. As a result, the development pattern of informal areas on agricultural land in Egypt has changed from being a demand-driven to a capital investment.

In the field of delivering goods, it is necessary to distinguish between the responsibility for ‘provision,’ which might be the government’s concern, and ‘production,’ which might be done through the social networks. It appears that private sectors have managed, through an informal land market, to produce housing plots at reasonable prices for most population in a record time. While official programs of the land delivery system have been consistently ineffective because of their financial incoherence and laissez-faire policies. These policies have led to almost the total breakdown of the formal land delivery system. This breakdown manifested not only as rapidly growing illegal statements but also as an establishment of informal land markets in most of the large cities. The following part examines briefly the concept of LRP, participatory inclusive process, PILaR, and how this process will lead to win-win process.

In a short report, Home (Citation2007) summarized the origins of LR in Germany that are often attributed to the 1902 Lex Adickes of Frankfort-am-Main. German legislation was translated into Japanese and adapted in “the 1919 City Planning Act. ” In Japan, since the 1960s, LR operations have been less frequent and are increasingly contested by the citizens (Sorensen Citation1999). Its use has been particularly widespread in Japan where it is responsible for about 30% of the existing urban area and is commonly referred to as ‘The Mother of City Planning’ (Sorensen Citation2000). Following the apparent success of LR in Japan, LR has now been applied to other Asian countries including Korea, Indonesia, Nepal, Thailand, and Malaysia. LR has since been widely used in various other developed countries including Spain (UN-Habitat Citation2016) and France (Turk Citation2007), where land administration systems are comprehensive and legal systems are well established. In Turkey, LR is a potential tool for providing solutions to the problems occurring in traditional urban renewal processes (Turk Citation2008), but it is contingent upon the availability of some basic conditions (Turk Citation2007). In the Middle East countries, the British administration applied it in Palestine in the 1921 Town Planning Ordinance LR provisions (called ‘parcellation’). After the end of the civil war in Lebanon (1991), the city center of Beirut was extremely fragmentation of property rights between multi-generational family ownerships, and by complex tenancy structures. The Solidere, as a private company, has redeveloped the city center based on LR. Since then, LR becomes a land development technique to converse urban-fringe lands into specific land uses and offers the potential to replan areas without the costs of compulsory land acquisition. However, the basic concept of LR began to appear in widely read publications of the United Nations Development Program, the World Bank, and similar organizations by the 1980s. Moreover, LR was recognized by knowledgeable professionals everywhere (Hong and Needham Citation2007).

LR facilitates development in three diverse ways: First, it combines the assembly and re-parceling of land for better planning. Second, it provides financial mechanisms to recover infrastructure costs. Finally, it distributes the financial benefits of development (also known as betterment levy or the added value that can be created by planning permission) between landowners and the development agency (Home Citation2007). LR is an approach or a technique (Archer Citation1989; Soliman Citation2014) that others considered as a method of urban planning or program (Masser Citation1987; Turk Citation2007). LR is a mechanism through which land ownership and land use of fragmented adjoining sites are rearranged or shared for unified planning and servicing. This mechanism also reallocated lands with project costs and benefits that are equitably shared between and among landowners. LR also provides land for development purposes such as slum upgrading and regularization, orderly development of new residential areas, and planned development of vacant areas that are expected to turn into proper land uses. In post-conflict or post-crisis situations, LR or land pooling may be an effective mechanism for responding to population distribution changes. It can be adapted to the re-blocking and regularization of customary land developments in the form of Participatory Slum Upgrading Programme, as it was applied in Benin, West Africa (UN-Habitat Citation2015a).

LR has shown its value for, first, the servicing and subdivision of urban-fringe landholdings. Second, it provides the government with the land required for public roads and open spaces at no cost. Also, it affords the cost of the road and public utility service networks in the project. This is achieved out of the concomitant land value increase (Archer Citation1987) with the sale of some new building plots for cost recovery and redistribution of the other plots to the landowners (Archer Citation1989). Third, LR has social benefits that impose a kind of betterment levy on landowners who are compelled to sacrifice some of their property to reap the capital gains resulted from comprehensive development (Masser Citation1987). Fourth, LR plays a significant and very successful role in responding to the problems created by rapid urbanization (Tae-Il Citation1987). Another form of LR is the land sharing (Archer Citation1999). This is of interest for informal settlement upgrading and regularization (UN-Habitat, Citation2015a). The owner of land occupied by an informal settlement is given incentives to lease or sell part of his property to the occupants below market price, as well as to recover and develop the remaining part of the land. In short, LR is a win-win process that involves various stakeholders by which all of them gain some sort of benefits either social or financial or both. In addition, the whole process is under the responsibility of a public agency, with all rights holders in a compulsory partnership.

LR has some sort of limitations. First, the need for a more critical evaluation of existing practice than what has often been used so far. Second, the need for careful consideration to be given to the institutional context in which potential applications in developing countries should take place (Archer Citation1987; Tae-Il Citation1987). Third, LR may not lead to an equitable solution for all those involved. Fourth, some small landowners may be effectively excluded from the process. Fifth, LR associations are often coercive in nature and seen to be a city as the political arm of public bodies. Sixth, it requires strong community organization and the coordinated intervention of several stakeholders, community, landowners, credit institution, land development agencies, and government land administration institutions. Seventh, LR has not really benefited low-income occupants, whose tenure status is fragile, and drastic increases in land prices following LR have accelerated gentrification in the areas concerned. Finally, in more expensive urban areas, relocation is based on the value rather than the size of the land, and the principle of virgin land against serviced land occurred. LR is particularly difficult to implement in developing countries where public participation is not integrated into urban planning or where there is limited capacity to maintain ownership records and resolve competing land claims (Land Lines Citation2011), as well as to maintain a proper technical know-how for LR.

It is argued (Masser Citation1987) that to avoid the above limitations, certain basic prerequisites must be kept in mind. First, it is essential that an appropriate legislative framework should take account of the considerable differences that exist between property rights in different countries. Second, there is a need for an effective system of cadaster and title registration operated by a body of well-trained and objective real estate appraisers. Third, there is a need for dedicated and energetic staff. Finally, there is a need for a supportive and consolidated partnership among all the stakeholders involved in LR.

However, PILaR uses the same idea as conventional LR (swapping land for improved services), and it does so in a participatory and inclusive way. Participatory processes mean that all beneficiaries involved in the planning process and have a say in decisions that affect them, as well as in what happens in the project from initiation to implementation. It means engaging with the local community to help them get organized and informed of the project possibilities. Also, to make sure they know their rights, and build their capacity, so they can express their interests and interact with other stakeholders (UN-Habitat Citation2016). Eventually, they have the freedom to build a better environment.

On the other hand, inclusive processes mean ensuring that all stakeholders share in both the costs and the benefits in a fair and equitable manner. It identifies the formally recognized rights of each stakeholder, where the needs, interests, and requirements of all people are met. The principal way of ensuring participation and inclusiveness is through close engagement with the community affected by the project (UN-Habitat Citation2016). Solomon (Citation2014) argued that ‘local citizens have something to offer, and that will be realized through equitable sharing of benefits and costs among all the stakeholders,’ and we should not treat people as investors but as beneficiaries. However, it could be argued that the output of PILaR is a serviced commodity that can be bought and sold in the market. Consequently, it would have a use value, an exchange value, or use/exchange value; moreover, people should not be treated as beneficiaries but also as investors. What matters the most is the land value rather than the land size. That’s why it is a continuous process of ‘win-win and not a static process of lose and-gains.’

PILaR differs from conventional LR in various ways. PILaR is a land assembly mechanism in which land parcels, with different claimants, are combined in a participatory and inclusive way into a contiguous area for more efficient use, subdivision, and development. However, it emphasizes a participatory process rather than only the technical or financial results, for inclusive outcomes that benefit all, including the poor and vulnerable. It is based on human rights to distribute burdens and benefits more equally among the private and public sectors. This is through public–private partnerships (Payne Citation1999), legal reforms, and capacity building. It also strengthens governance and improves land administration. Moreover, it integrates PILaR with other urban development and planning initiatives (UN-Habitat Citation2016).

PILaR projects are undertaken to meet the broader economic, social, and environmental objectives of the country, including poverty reduction (UN-Habitat Citation2016). A successful PILaR is directly linked to social networks. The stronger the social networks in the form of homogeneous community structures, social capital, and connectivity, the better distribution of power among a group of people.

Therefore, the relationships between the three independent systems, State, market, and social network, are correlated. The latter is reflecting strong social ties that would formulate local finance customary and sustain a cultural identity. The idea that proper plans could be directly implemented reflects a very traditional conception of a spatial blueprint plan. This would steadily be translated into a built form on the ground (Healey Citation2003). Therefore, PILaR is a mechanism to convert unusable land, or brownfields, into a serviced land, as well as to create an applicable sustainable environment at the right time, by the right people, and in the right place. In light of this mechanism, all the stakeholders in a planning process, through a participatory inclusive process, are actively cooperated to manage the process positively for their own benefits without harming the others. Thus, a social network in the physical environment is dominating right of ways, pattern, and everyday urban life, all of which are reflecting human rights. The participatory inclusive process would require trust, transparency, accountability, and responsibility among all the stakeholders for a certain activity to be achieved.

4. Egyptian context

Below is briefly highlighted the major efforts that were made to control or at least to eliminate the spontaneous expansion of the Egyptian cities.

4.1. Egyptian planning efforts

During the last six decades, the lack of a proper future planning vision, the absence of a precise planning policy, and the possess limited capacities for good urban land management have forced the state to regulate the urban growth and to redistribute the rapidly growing population outside the Nile Valley. These attempts have followed the blueprint plan that implemented in the late 1950s. However, urban sprawl continued to spread on the periphery of the major urban centers by which Ashwaiyyat became the major phenomena of the Egyptian landscape (Soliman Citation2014).

In mid-2000s, the Egyptian government introduced the GSUP for 331 Egyptian cities aimed to control the arbitrary urban land expansions and to prevent further conversion of agricultural land into urban informality. This scheme was involving a participatory approach and using GIS tool for analysis and planning (for details, see Soliman Citation2010, Citation2011). As illustrated in , the methodology of the GSUP was divided into three phases. During these phases, subsequent workshops were held with the stakeholders to hear their responses to the questionnaires and to review the outcomes of data and analysis. The timing of implementation and planning to finance investment projects were settled. The DPNULE is the main output of this scheme.

illustrates the progress of the GSUP for seven cities, five cities in Lower Egypt and two cities in Upper Egypt. Out of the seven cities, only two cities are in progress of DPNULE, another city is under studying, while the other four cities are not eligible for DPNULE yet. It appears that the GSUP might take between 2 and 7 years to be finalized due to many reasons. It seemed that the GSUP was a blueprint plan that neither met its objectives nor prevented further urban sprawl on agricultural areas adjacent the official city boundary (Toth Citation2009; Soliman Citation2014). This failure was due to the mismatch between what to be done on the ground and what can be theoretically gained from the PBL119 of 2008. The difficulties suffered by the landowners and the challenging planning system lead to a slow performance of public bodies in the implementation of the output of the GSUP. This slow performance cannot compete with the rapid informal urbanization progress on the ground. As a result, more agricultural lands have been converted into urban informality. Urban planning in Egypt is still tied down to old modernist paradigms. The current challenges and the future urban sustainability rise the worry of the ongoing State’s attitude. What comes to mind while thinking of the Egyptian cities is informality, informal rapid urbanization, a housing crisis, climate change, lack of infrastructure, etc.

Table 1. Illustrates the progress of the GSUP for seven cities.

In 2017, the total population of Egypt approaches the figure of 100 million, of whom 93 million live inside the country, while the remaining life abroad. Whereas two major urban centers (Cairo and Alexandria) accommodated about half of the urban population, the remaining population are scattered in 331 small and intermediate urban cities along the Nile River Valley and Delta. The total population of Egypt will reach around 151 million by 2050 (CAPMAS Citation2017) when 62.4 percent will be urbanized. In light of this present trend of creating new spaces, it is expected that agricultural land conversion into housing informality will be perpetuated (Soliman Citation2014), unless an appropriate policy is achieved. Therefore, below is a demonstration project based on PILaR to facilitate the progress of the DPNULE. For the first time in the Egyptian urban history, the project has introduced PILaR as a tool that enables cities to significantly increase the supply of serviced land at the urban fringe, through orderly and negotiated processes of LR (UN-Habitat Citation2015b).

4.2. Research settings

The city of Benha is located approximately 45 km north of Egypt’s capital, Cairo. The city has expanded, like all Egyptian cities, to all directions with urban sprawl surrounding both edges of the river Nile and on surrounding agriculture lands. In 2007, the GSUP set forth a vision for Benha for the next 20 years and therefore projected population growth and needs until 2027. It created a new urban boundary with an area of 944 ha of the city, for a projected density of 54 person/hectare. The city’s population is projected to a total population of 211,200 by 2027. In 2011, the GSUP was officially approved by the responsible minister according to the BPL119 of 2008, making a way for the ‘detailed planning process’ for the new ‘urban expansion areas.’

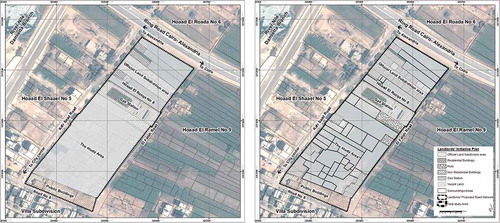

As a part of the proposed urban land expansion, El Rezqa area was chosen as a demonstration pilot project using PILaR scheme to prepare and implement the DPNULE on the ground. As illustrated in , the site is rectangular in shape and situated in the northeastern part of the city with an area of 4.5 ha. It is surrounded by four main streets ranging between 10 and 28 m. A gas company, with an area of 0.42 ha, subdivides the site into two parts: the southern part of an area of 2.8 ha and the northern part of an area of 1.28 ha. At the southern west edge, there is a services amenities area of 0.37 ha, which includes several governmental buildings such as a library and a court house. There are also a few scattered residential buildings, but most of the site is on agricultural and vacant land. The illegality stems from the site has not officially approved as a detailed plan project and the illegality of building heights and violations of building code.

Originally, the entire site was owned by two persons; however, as soon as the GSUP was introduced, informal urban land subdivision expansion was taken place and an informal land subdivision was introduced. This illegal subdivision followed the irrigation pattern of the agricultural land subdivision and separated into small liner narrow strips. These strips with an average area varied between 0.04 and 0.5 feddan perpendicular to a small canal, which is currently formed Kafr Saad Street. There are four typologies of land development in the site: amenities land development, informal housing development, semi-official land subdivision development, and landowners’ informal land subdivision development. Each of which has its own circumstances for the development. illustrates the site’s current land uses, in which vacant and agricultural land and formal and informal residential buildings constituted around 61.87% and 17.41% of the total area, respectively, while road network and open spaces represented 3.02% of the total area.

Table 2. Illustrates the site’s current land uses.

The implementation of PILaR scheme has passed through three distinct stages. First, a field survey stage to examine the initial possibility of carrying out the project. Second, planning principle stage to prepare the scheme. PILaR options are considered and discussed with the landowners and occupants, by which plots are reallocated. Finally, the implementation stage, in the form of a participatory inclusive process, to implement the project on the ground and to deal with administrative arrangements relating to a land subdivision, road network, various licenses, and land registration.

4.3. The field survey

For PILaR implementation, the TT should understand land ownership and know the number of landowners, as well as the current spatial status of the site. Several meetings were held with the landowners. In the first meeting, the TT explained the key objectives and the purpose of the project. It was clear from the first meeting that although the landowners themselves had attempted to subdivide their own lands, they had not been able to find a viable plan for many reasons. They were unable to find a solution works for all. Even though the landowners had been in negotiations for 3 years.

At the next meeting, the TT informally found out that the LSA had what is known as parcel map at a 1:1000, which includes parcel numbers from the REPA. But this map is not for public view. Through an informal channel, the TT obtained this map and superimposed it on the site. The TT now had four maps presenting different information:

Land parcels mapping as per the TT physical land survey effort.

Land parcel histories as per information at the REPA.

A land parcel map from the LSA.

Informal land subdivision proposed by the landowners.

The TT took this information and worked to come up with potential lands for land swap scenarios (as will discuss later) that could have higher allocations for services and reach consensus from the landowners simultaneously.

4.4. Planning principles

The TT began to develop a series of plans for the area over a period of 6 months. Each alteration was taken in a different consideration that was either raised by the landowners or by the governorate urban planning department. The TT wanted to provide a number of land parcels matching the landowners’ number and corresponding to their land sizes and value criteria. On the other hand, the landowners wanted to maximize buildings heights for higher profit. Furthermore, the allocation of land parcels within the site faced great disputes among the landowners and the TT. These sorts of negotiations and disputes were the main reason for several alterations of the plan as displayed below.

Consequently, the TT initiated a set of basic principles and choices to get a preliminary agreement before assigning any new reparcelation of the plots to reach a consensus among the landowners. Throughout the entire process with the landowners, the TT initiated a set of basic principles, which has prioritized the following five values: transparency, equity, trust, credibility, and efficiency. Through these values, the TT could establish a sort of social network and a bridge of trust to ensure that all landowners would participate and find a sort of compromise among all participants. The TT tried to minimize the loss and maximize the gain to reach a communal compromise among all landowners. One meeting after another, the landowners became convinced to accomplish a groundwork agreeable plan. Eventually, when the landowners agreed to a plan, they signed a preliminary agreement consenting to the concept of land to a land swamp. The agreement included the following planning principles for which the reparcelation would be based on.

All landowners would give up the same percentage of their land for road network and services according to the BPL119.

In reassigning a plot of land to a landowner, the TT would do its best to make sure it would be in the closest physical proximity to the landowners’ original parcels.

The TT would also respect any specific advantages that a parcel had and make sure the ‘new parcel’ provided for those advantages. For example, if one person had a corner parcel prior to the reparcelation, he would also have a corner parcel after the land to land swap albeit smaller.

The minimum street’s width will be 10 m.

The minimum land parcel’s size will be 120 square meters.

In the case that land parcel’s size is less than 120 square meters, a landowner will reimburse his exact land size in another land plot to be shared with others.

The minimum land plot’s facade will be 10 m

5. Participatory inclusive planning process

To achieve sustainability, the DPNULE structurally utilized participation in the planning process and took advantage of landowners’ social network on local situations (see ). The TT required to provide the technical know-how and assumed the role of facilitators in enabling local voices to be heard. Sustainability of the thoughts of the landowners’ participation, the installation of utilities, and the needs of a proper layout road network emerged. This led to a semiformal institution of building procedures and planning regulations, in which a form of balance between needs and requirements, responsibility, and duties of the landowners, and what landowners were willing to play, was reached.

Figure 3. The top six shots illustrate some meetings with the landowners, left bottom shot illustrates a meeting with the Mayor of Benha’s city, middle bottom shot illustrates a meeting with landowners’ representative during signing up a preliminary agreement, right bottom shot illustrates the approval of the project by the governor of the Qaloubia governorate.

5.1. Planning scenarios

One of the key objectives of the project is to test PILaR as a possible methodology/mechanism for implementing DPNULE. The project also evaluated the pros and cons of building illegally at the landowners’ level. The idea here is a demonstration project using scenario analyses. It illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of the PILaR to stress on the strengths and to eliminate the weaknesses. This is to reach a better quality of life besides financial wins with a formal planning process.

To transform attitudes at the landowners’ level, the project set out to develop the following five scenarios: government-sponsored detailed plan; landowners’ initiated land subdivision; comprehensive land to LR; integrated land to commodity exchanges; and privately initiated land subdivision to capital exchange.

The TT realized that the privately initiated land subdivision to capital exchange and the land for commodity exchanges scenarios would not be successful. In terms of both scenarios, after several consultations with local experts and landowners, it became clear that while landowners could be willing to swamp their land for a smaller piece of serviced land, they simply would not take ‘land value’ for either commodity exchanges or a capital exchange. These scenarios were rejected by the landowners as they preferred to keep possessing their landownership as a collateral asset for securing their kids’ future and as a matter of future capital investment. For them, land value is too risky. It requires a bridge of trust between the government and landowners, which many of them do not feel guaranteed their lifelong investment.

5.1.1. Government-sponsored detailed plan

According to the BPL119, it is the responsibility of every governorate to prepare a DPNULE as identified in every city’s strategic urban plan. This exercise fails for several reasons. One of the key reasons is that land ownership data is not available for the consultants who are developing the plan. As a result, consultants’ plan on a large-scale level, without a framework for how the roads and services they are adopting, will be implemented. Thus, the urban planning department in the governorate is unable to implement a plan which they see inapplicable for the city ‘a dead process.’ The real impact here is that without the approval of a detailed plan, any person who builds on an urban expansion area is building illegally.

The TT preferred to showcase this scenario as it not only highlights the bottlenecks with the law but also shows how urban expansion areas cannot be developed if developers are to abide by the BPL119. This is one main reason why there is rapid informality on urban expansion areas. Landowners are aware of their land’s potential development value and that a governmental sponsored detailed plan is not likely to be approved or implemented. A sample of this plan shows that a consultant divided the urban land expansion into ‘superblocks,’ without taking into consideration the exact boundaries of existing land ownership. Also, superblocks should apply for a project for a land subdivision to the REPA, in which all land parcels should have officially registration documents at the REPA. The main issue here is that these superblocks neither lead to buildable lots nor conserve the land ownership. As a result, this leaves landowners with few options other than building illegally. With regard to the government scenario, due to the issues with the BPL119, owners would build illegally in all cases as it is virtually impossible for them to get legal building licenses as will be described in the next section.

5.1.2. Landowners’ initiated land subdivision

In addition to realizing the potential development value of the landowners’ land in which they would be willing to build and capitalize on this value, they realize the importance of planning a road network. This is crucial because otherwise one or more landowners could end up landlocked if they both do not agree on a road network. To do this, the landowners typically hire a local engineer or an architect to subdivide their land for them. This was the case in the southern part of the site. illustrates the landowners’ efforts on subdividing their site. Even if they agreed on the land subdivision plan, they should apply this plan to the REPA, as in the previous scenario, to have an official approval according to the BPL119.

During this process, the landowners accept that a portion of their land will be taken for the road network (it was around 31% of the total area). Yet, the goal is to keep this portion as minimal as possible. That is why entire neighborhoods all over Egypt, have come up with the characteristics, that are considered not healthy neighborhoods from the planning and public health perspective.

One of the main challenges for the landowners is that they could not simply get the participation of all landowners in the site. The landowner, who already has a property that faced the street, did not feel the need or the desire to participate in the process. Another problem was that the site has no access to the main road, and the landowners negotiated to purchase a land parcel from an owner who has the accessibility to the main road. This negotiation took around 3 years; however, all landowners could not manage to collect the needed money for this acquisition. Nevertheless, it was necessary to find another way out to solve this problem. Moreover, as previously mentioned, no space was left for services, and the primary goal for this subdivision is to simply ensure that each land parcel can have entry/exit access.

This Landowners’ initiative was planned according to each landowners’ property size. It has consisted of 35 land parcels varied in size between 120 and 450 square meters. Land plots were arranged in a back-to-back concept to allow each land parcel to have a facade on the designed road network. The total area allocated for road network was around 31% of the total area of the site. Challenges with this plan were as follows:

Landowners’ plan did not include the entire site from the public premises to the gas station.

The street that served as a gate for the entire site and specifically for this group of landowners’ plot was owned by one person whose solution was to offer his piece of land for sale. Yet, the landowners could not afford the asking price.

The proposed three streets were dead ends which would not allow for vehicle movements and would not meet the requirements of the BPL119.

The proposed entrance area is less than 10 m, which is not applicable with the BPL119.

The plan does not meet the requirements of the BPL119, as the road network is less than 33% as well as there is some land parcels size less than 120 square meters.

The proposed subdivision plan should apply to the REPA by which all land plots should be officially registered at the REPA according to the BPL119.

These challenges as well as sponsored detailed plan challenges represent the outcomes of a failed legal process. Since the law does not provide a functional way for transforming the land into ‘buildable plots,’ landowners attempt to take the matter into their own hands. Yet with the participation of other stakeholders such as government or civil society, not only landowners face challenges that are hard to overcome, but also the entire process is monopolized by one group of stakeholders. The result is that landowners subdivided their land informally.

5.1.3. Land to LR

After evaluating the previous two scenarios and other options, strengths and threats were questioned (see ). It was important to understand this framework to develop a methodology that could challenge the illegal subdivision on urban land expansion. The TT determined that to achieve that, a three-level approach would take place.

Table 3. Illustrates strengths/threats of illegal building.

At the national level, it is a good chance to demonstrate how a guided plan development could enhance the built environment of the Egyptian landscape.

At the policy level, a continued lobbying effort to reform the law to develop a process that encourages legal building, legal land subdivision, and discourages informality.

At the developer level, a rethink in a perception of the cost and benefits of building illegally.

The TT decided to assess whether PILaR could be a mechanism to achieve this or not. One key strength of this specific site is that the landowners were already amenable to giving up portions of their land in design road network and to sign on an agreed plan confirming their willingness to cover the cost of infrastructure or to pay betterment levy for their land plots. Our question was: Can we push this thinking to allocate serviced land while creating a legal framework that would address the challenges posed by PBL119?

Knowing the challenges of the governmental sponsored detailed plan and landowners’ initiated informal subdivision, this project aimed to find a third way, a way in which the only goal is not profit maximization, but building healthy neighborhoods rich in services instead. Building upon the previous planning principles, the TT persuaded an owner, who owned a land strip crossing the site from the west towards east, to participate in the project. This piece of land was the only part that has accessibility to the main road. Accordingly, a preliminary plan was introduced and discussed with the landowners. The advantages of the plan were clarified and the main idea was accepted by all the landowners.

Depending on the previous planning principles and strengths/threats analysis, the consultant sketches up a preliminary plan. This plan was to include the southern part of the site in one package and to convince the landowner, who owns a strip of land crossing the site from the west towards east, to include this land into the scheme. The strengths of this plan were as follows:

The plan did include the whole site from the public premises to the gas station.

The person who owned the land strip that could be used as a street to be a gate for the entire site was offered land to serviced swap land. Yet, the landowners would not be asked to pay any extra money.

The proposed road network depended on loop pattern that could allow for vehicle movements, and it has two entrances, by which the whole site formulated a gated community.

The proposed entrance width is 10 m, which is applicable with the BPL119.

The plan does meet the requirements of the BPL119, as the road network is within a range of 33%, as well as there are two land parcels allocated as a clinic center, and as a mosque to serve the community.

The minimum land size, 120 square meters, is within the specification of the BPL119.

The plan will be signed by all landowners with commitment and acceptance of the proposed road network as a public utility and their willingness to cover the cost of infrastructure according to their land shares.

5.2. Process of participation and analysis

The role of landowners for the DPNULE was formulated as follows. First, the TT was convinced to identify a range of options that would give the landowners the flexibility to choose their urban setting, the location of land parcel, the size of the land plots, and/or the way in which their resources were invested. Second, the landowners introduced arrangements among themselves that accelerated illegal/semilegal land subdivision. They acted freely outside the official legislation and applied their control over their own environment. Also, they were convinced to waive a part of their shares in the land to achieve the requirements of the road network according to the BPL119. Third, in addition, that landowners embodied the local knowledge to be accessed and their participation presented an important entry point to the political decision-making needed for exploring differing viewpoints and initiating negotiations leading to a positive coordination if not a consolidated cooperation. Fourth, the landowners have relied on a great autonomy in their environment, with enhanced participation in the land allocation process, in a record time that created a sustainable environment. Fifth, the landowners have relied on their culture, their talent, and symbolic aspects of their lifestyle by which land allocation and settlement form was formulated within the site. Sixth, the social network was formulated on the ground through positive negotiations among the landowners themselves as well as the TT. Thus, the project encouraged culturally valid, homogeneous neighborhoods, locating people in physical and social space reflecting the residents’ identity.

The TT had to set up several meetings with the landowners to reach a common vision that would satisfy the wishes of all stakeholders involved in the PILaR, as the output of the DPNULE, according to the GSUP and its regulations. The TT also analyzed the situation of the PILaR and consulted the stakeholders through workshops and meetings to obtain a clear view of the potentialities and constraints of the PILaR. As a result, several plans were drawn and presented to the stakeholders.

A comparison was made between several proposed plans, Segal Ainy plan, and proposed roads network (see ). The PILaR was analyzed according to the following indicators: the number of land plots, types of land tenure, land ownership, land parcels’ size, land allocation, streets width, and road network. A comparison between different road networks of the DPNULE was made through analyzing the following variables: a net area for housing blocks, a percentage of land to be allocated for the road network, the purposed built-up area to total area’s size, and various amenities according to the PBL119. Replacement of deficit land plots not matching the proposed road network was made. Expected number of land plots needed to cover all landowners’ shares and expected number of population and density for the proposed built-up area (number of persons/hectare) were reached.

Figure 5. Represents various scenarios by the TT to reach a land readjustment scheme. Right bottom drawing illustrates the final agreement on the scheme by all the stakeholders.

represents a comparison between the three scenarios and illustrates before and after the proposed plan. It also illustrates the landowners’ initiated land subdivision scenario that yields the highest number of residential units. This is because, in the landowners’ initiated subdivision, building heights are not obeyed. To maximize their profit, landowners build above the permissible heights which leads to a higher number of residential units. Also, landowners’ land subdivision plan does not include any public facilities, while the PILaR plan includes a clinic center and a mosque with an area around 700 squares meters. Total percentage of land devoted to roads, green spaces, public facilities in landowners’ initiated plan, and proposed LR plan is 32.9% and 31.98%, respectively.

Table 4. Illustrates financial analysis of government-sponsored detailed plan, landlords’ initiated land subdivision, and land to land readjustment.

Based on the principles of participatory inclusive process, several output maps’ proposals were produced from GIS, presented, and discussed with the stakeholders. The output was a variety of scenarios in a visualized form, with excel sheets for determining the various variables of the reached scenarios for the DPNULE in Benha city (see ).

The preliminary plan was presented to the landowners to have their feedback, as well as to start redistributing land to land swap according to each landowners’ land size after subtracting the road network and utility percentages from each. The next task was the land allocation, as each landlord want to have the most privilege to his own new land location to maximize his own benefits. This was a challenging task to be solved and was left for further negotiations with the landowners. Several maps for land plot’s allocation, within the agreed road network, were presented to the landowners to have their final approval and to agree on land to swap land. In addition, each of landowners should compromise to reach an agreeable plan. After several meetings and various amendments made on a land allocation plan, around 98% of landowners agreed on a final proposed plan (see and ).

Figure 6. Top two shots represent the situation before applying LRP, bottom two shots illustrate the situation after applying PILaR

The preparation of the PILaR took around 18 months. It was approved by the governor of the Qaloubia governorate in 15 October 2014 (see , the bottom three shots, and ), and the official decree for the project issued in Egyptian Gazette, No 160, 12 July 2015. The technical work was finished within a period of 6 months, while the evaluation, negotiations, reviewing, and official approval processes took around another 12 months. In the meantime, the implementation process is taking place on the ground.

6. Conclusion

Despite the failure of the GSUP in meeting the residents’ needs for housing plots and other amenities, the stakeholders involved in the LRP as the output of the DPNULE have managed to communicate with each other in determining their destiny, by which a participatory inclusive process was flourished. The PILaR was for ‘scaling up’ the development process on an affordable basis at a faster rate than that can be achieved by the government. PILaR in Egypt has offered three advantages for most of the landowners. First, PILaR in the land markets encouraged the landowners for obtaining a legal and/or an illegal house site with reasonable basic services and suitable access to income-earning possibilities. Second, it has operated outside the official building and planning regulations that offered freedom to the landowners to act in and formulate PILaR according to their needs and requirements depending upon their incremental change of their socioeconomic status. Third, social networks have created a participatory inclusive process, among individuals or a group of a community, by which, PILaR and distributive outcomes were robustly grounded. It achieved and provided a great flexibility within the physical environment than what was found in a government-sponsored detailed plan.

During the process of PILaR, the TT has learned many lessons; first, the involvement of governorate institutions in PILaR cannot be reached without a productive social network and technical support from knowledgeable staff. Second, the governorate can respond positively if project findings meet the prevailing laws and are conducted by positive community involvement. Third, the experience of PILaR of Benha’s landowners demonstrated the landowners’ ability to commence, categorize, and handle their own development process with little or no support from either central government or local authorities, but with a positive technical support from the TT. Fourth, a knowledgeable expert (preferably architect or urban planner) is essential in this process. By this expert, the plan would accelerate gentrification through an urban planning pattern that matches the landowners’ needs and requirements, reflecting their cultural identity and economic capability. This pattern would also provide a semi-gated neighborhood that reflects a privacy in the environment. Fifth, understanding the process of the PILaR as the outcome of the DPNULE of the city, participatory inclusive process, social network, and the stakeholders’ roles would enable the State and housing professionals to alleviate urban informality within formal planning zones and accelerate land delivery system to promote sustainable socioeconomic development.

The main limitations of PILaR are as follows: first, there is an urgent need to reform legislative process to match the status quo that most of the peri-urban areas have not official documentation for land tenure. Second, reviewing the GSUP, the DPNULE, and the PBL119 has become vital, from the perspective of local powers desiring control, as various potentialities, constraints, and Egypt’s magnification of rescuing agricultural land have arisen. Third, a clear understanding of LRP, participatory inclusive process, social network, and people’s needs and requirements for housing plots must be accomplished. Fourth, the LSA and the REPA seem to be the most burden for the project’s implementation; therefore, an urgent amendment or modification of their procedures is essential. Moreover, tools, mechanism, and rearrangement are urgently needed to provide compatibility between cadastral maps and maps serving as a base of development plans. Fifth, time-consuming and recurrent changes of the municipality’s representative are main obstacles in delaying the implementation of the project. Sixth, all costs for the TT covered by UN-Habitat and the local municipality have no fund to cover such costs. In addition, the LR model in Egypt does not accommodate the opportunity of providing low interest-bearing loans from banks for project self-financing. Seventh, the smaller the size of the area, the greater the success of PILaR and vice versa.

In practice, lower-income and middle-income groups can no longer wait to solve the complicated procedures or afford the new soaring prices. They have to look elsewhere for cheaper housing plots in younger settlements at other further locations. Their savings are usually channeled to starting a business, securing a dwelling, or both combined in the same structure. This is a simple equilibrium that most of the urban poor are looking for to ensure a better way of life.

The gap between the government policy and the capacity of community members should be narrowed. This is to identify what is of critical importance and what is required for people concerned, as well as what the government can provide and what people can afford. To shorten this gap, LRP associated with the participatory inclusive process should be encouraged. Also, the government should act as an agent for the avail of local citizens and for the compatibility and sustainability. Moreover, it should amplify political goal of rescuing agricultural land and encourage the sustainability of urban development in the back desert of Egypt.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Mrs. Salma Mousallem of UN-HABITAT, Cairo office, for her time, energy and support during the process of the project, and for her constructive comments throughout the process of building scenarios of this paper. I am also grateful to both Mrs. Clarisa Bencomo, for her continuous support, and for the Ford Foundation in Cairo, for securing the necessary fund to attend the 2015 World Bank conference in Washington DC, USA, in which an early draft of this paper was presented The two anonymous reviewers’ comments were helpful for improving the paper, for whom I appreciate their valuable comments. The valuable comments and positive support of Prof. Ramin Keivani are very much appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed M. Soliman

Ahmed Soliman received his Ph.D. in Social Sciences, Urban Planning and Housing studies from the University of Liverpool, UK from 1981 to 1985. He is currently working as an emeritus professor of urban planning and housing Studies and was a former Chairman of Architecture Department in the Faculty of Engineering at Alexandria University (2007-2012), Egypt. He was the Dean of the Faculty of Architectural Engineering at Beirut Arab University, Lebanon from 2000 until 2004. He has published widely on issues of urban planning, urban housing, and informal settlements in several distinguish international journals and contributed in chapters in various books. He worked with Hernando De Soto twice, the first time was in 1997 and the second time was in 2000, studying the informal settlements in Egypt. He is the author of A Possible Way Out: Formalizing Housing Informality in Egyptian Cities (2004), University Press of America, USA.

Notes

1. Technical team (TT) consisted of UN-Habitat’s members, Mrs Rania Hedeya, Dr M. Nada, Mrs Salma Mousallem, and a private consultant, who is the author of this research. Mrs Mousallem has played an important role in communicating with female landowners, as well as helping to set up the three scenarios. All opinion in this research is the sole responsibility of the author, and it does not imply any opinion whatsoever on the part of either the GOPP or UN-HABITAT.

2. Ashwaiyyat the plural for ashwaiyya (literally meaning ‘half-hazard’) is the term used in public to refer to the informal settlements in Egypt and is referring to illegal arbitrary housing development on the periphery of urban centers.

References

- Adler P, Kwon S. 2002. Social capital respective or a new concept. Acad Manag Rev. 27(1):17–40.

- Alexander C, Silverstein M, Angel S, Ishikawa S, Abrams D. 1975. The Oregon experiment. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Archer R. 1987. The possible use of urban land pooling/readjustment for the planned development of Bangkok. Third World Plann Rev. 9(3): 235–253.

- Archer R. 1989. Transferring the urban land pooling/readjustment technique to the developing countries of Asia, Third World Plann Rev, 11(3):307–331.

- Archer R. 1999. The potential of land pooling/readjustment to provide land for low-cost housing in developing countries. In: Payne G, ed. Making common ground; public-private partnerships in land for housing. London: Intermediate Technology Publications Ltd; p. 113–133.

- Barker I, Linden R. 1985. Community crime prevention. Ottawa: Ministry of Solicitor General Canada.

- Bourdieu P. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- CAPMAS. 2017. General statistics for population and housing: population census. Cairo, Egypt: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics.

- Collier P. 2002. Social capital and poverty: a microeconomic perspective. In: Grootaert C, Van Bastelaer T, eds. The role of social capital in development: an empirical assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Collier D. 1976. Squatters and oligarchs. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- De Soto H. 1989. The other path: the invisible revolution in the third world. London: I.B. Taurus.

- Engles F. 1970. The housing question. Moscow: Progress publishers.

- Fathy H. 1972. The architecture for the poor. A Phoenix Book: the university of Chicago Press, USA.

- Fawaz M. 2008. An unusual clique of city-makers: social networks in the production of a neighborhood in Beirut (1950–75). IJURR. 32(2):565–585.

- GOPP. 2006. TOR for general strategic urban plan for Egyptian cities. Cairo, Egypt, The General Oragnization of Physical Planning, Egypt.

- Hamdi N. 2004. Small change: about the art of practice and limits of planning in cities. London: Earthscan.

- Hasan A. 2001. Working with communities. Karachi, Pakistan: City Press.

- Healey P. 2003. Collaborative planning in perspective. Plann Theory. 2(2):101–123.

- Home R. 2007. Land readjustment as a global land tool: focus on the Middle East. London, UK: The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

- Hong Y, Needham B. 2007. Analyzing land readjustment: economics, law, and collective action. USA: the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Jackson L. 2010 Influences on financial decision making among the rural poor in Bangladesh, Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, School of Marketing, The University of Western Sydney, Australia

- Land Lines. 2011. Volume 23, issue 1 (January), Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, USA.

- Layton RA. 2009. On economic growth, marketing systems, and the quality of life. J Macro Mark. 29(4):349–362.

- Masser I. 1987. Land readjustment: overview, Third World Plann Rev. 9, (1):205–210.

- Payne G. 1999. Making common ground: public-private partnership for housing. UK: Intermediate Technology Publication Ltd.

- Perlman J. 1976. The myth of marginality. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Sims D. 2010. Understanding Cairo: the logic of a city out of control. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- Soliman A. 1985. The poor in search of shelter: an examination of squatter settlements in Alexandria, Egypt, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, the university of Liverpool, England.

- Soliman A. 2010. Remodel urban development in Egypt: a future vision, Paper presented at US-Egypt Workshop on Space Technology and Geo-Information for Sustainable Development, Cairo, Egypt 14–17 June, 2010

- Soliman A. 2011. Building bridges with the grassroots: housing formalization process in Egyptian cities. J Housing Built Environ. 27(2):241–260.

- Soliman A. 2012. Tilting at pyramids: informality of land conversion in Cairo, Paper presented at Sixth Urban Research and Knowledge Symposium 2012 World Bank, Washington DC.

- Soliman A. 2014. ‘Nothing more to lose’: Ashwaayat and land governance in Egypt, paper presented in Integration Land Governance into the Post-2012 Agenda Harnessing Synergies for Implementation and Monitoring Impact, Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington DC, March 24–27, USA

- Solomon H. 2014. Participatory and Inclusive Land Readjustment (PILaR): a primer, securing land and property rights for all, XXV FIG conference, 16–21 June, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Sorensen A. 1999. Land readjustment, urban planning and urban sprawl in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Urban Stud. 36(13):2333–2360. December 1999.

- Sorensen A. 2000. Land readjustment and metropolitan growth: an examination of suburban land development and urban sprawl in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Prog Plann. 53(2000):217–330.

- Tae-Il L. 1987. Land readjustment in Seoul: case study on Gaepo project. Third World Plann Rev. 9(3):211–233.

- Toth O. 2009. ‘Strategic plan for an Egyptian village: a policy analysis of the loss of agricultural land in Egypt,’ M.Sc. urban environmental management submitted to the School of Planning of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning, Wagering University.

- Turk SS. 2007. An analysis on the efficient applicability of the land readjustment (LR) method in Turkey. Habitat Int. 31(2007):53–64.

- Turk SS. 2008. An examination for efficient applicability of the land readjustment method at the international context. J Plann Lit. 22(3):229–242. (February 2008).

- Turner J. 1976. Housing by people. London, England: Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd.

- Turner J, Fichter R. 1972. Freedom to build: dwellers control of the housing process. New York, USA: the Macmillan Company.

- UN-Habitat. 2015a. SLUM ALMANAC 2015 2016: tracking improvement in the lives of slum dwellers. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

- UN-Habitat. 2015b UN-Habitat global activities report 2015: increasing synergy for greater national ownership, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi, Kenya, 31.

- UN-Habitat. 2016. Remaking the urban mosaic: participatory and inclusive land readjustment. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

- Ward P, ed. 1982. Self-help housing: a critique. London: Mansell Publishing Ltd.

- Woolcock M, Narayan D. 2000. Social capital: implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Res Obs. 15(2):225–249.