ABSTRACT

As a consequence of the rapid, government-led and globally fuelled urban development that is occurring within China, an unplanned form of urbanization is emerging, whereby landless farmers and economic migrants are resettling and occupying both public space and housing in ways that deviate from the community development plan.

The paper will use both historical and contemporary urban theory, together with a case study of Zhangjiing in Suzhou Industrial Park, China as means of critiquing and learning from these consequences and the planning and policy instruments in place. The case of Zhangjing can be critically reviewed in the context of Christopher Alexander’s argument that when a new urban development is created which is modelled or predicated on a tree structure to replace the semi-lattice that was there before, the city takes a step towards dissociating itself from its geographical and cultural context.

Introduction

The Chinese Government has defined access to affordable housing of a reasonable quality for all of its citizens by 2030 as a primary target and indicator of China’s evolution towards a ‘well-off society’ (www.cs.com.cn, 2012). As part of this assessment, in 2012, the China Academy of Urban Planning and Design initiated an academic research project to devise a set of Quality of Life (QoL) indicators. One conclusion from this research was that the growing cost of living and inflation in China’s growing cities, including increased housing prices, has become an important factor that can lead to lower available income and a reduced quality of life.

The prolonged period of urbanization that China is currently experiencing is expected to continue, with the total urban population likely to peak at around 70–75% of the current population by 2050. The rural village to the city is the main direction of mobility, with approximately 80% of economic migrants holding rural household registration (Hukou) (Meng Citation2012).

Given the scale of this transition, it is important to consider the implications for housing design and provision in the migration of rural Chinese communities to a more urban context. In order to better understand this, the paper critically reviews an area of farmland formerly named Wuxian within the city of Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) in China, using a case study undertaken from September- December 2012 by a research team of Xi’an Jiaotong – Liverpool University staff and students. The development of SIP commenced in 1992 as part of an urbanization project within Suzhou that also includes Suzhou New District. Zhangjing is an urban community on the west of Weiting Town in SIP, the construction of which was completed in December, 2004 (Suzhou Development and Reform Commission, Citation2008). To relocate the landless farmers within this formerly agricultural area, a series of resettlement communities were established, with Zhangjing Community being one of these. Zhangjing covers 3.2 Km2 and consists of two parts, the East (first phase), and the West (second phase).

Within this context of migration and resettlement, the purpose of this paper is to examine the new types of urban communities that are arising, referring particularly to the settlement of relocated households where urban planning and land development have been conducted. The emerging reality of these urban communities, and the issues that they highlight, will be used to appraise both the planning process and whether this transformation can be seen as illustrating an informal and unanticipated shift from urbanism as an artificial set of design prescriptions, to a more ‘natural’ and self-regulating system which in practice takes on a life of its own. This question has its origins in the work of Alexander (Citation1972), who made the distinction between the city as an ‘artificial’ tree to the city as a ‘natural’ semi-lattice, with overlapping and complex interdependencies. The robustness of Alexander’s metaphor and its application in theorizing the practice of urban design and urbanism is attested to by the number of urban theorists who continue to find his ideas useful (see for example Vaughan and Griffiths (Citation2013), and Partanen (Citation2015))

Considered within the context of a theoretical review of how urban expansion occurs, the aim of the case study summarized in this paper is to provide a better understanding of how urban neighbourhoods are evolving in contemporary Chinese cities, both within the particular context of Zhangjing and as a more general and transferable lesson for urban development.

Research methods

Practice-oriented research methods and time-lapsed, site-based analysis are used in order to address the research questions outlined in the introduction. This includes an assessment of the public space, residential and urban typologies of Zhangjing, in order to better understand the implications for housing design and provision for the migration of rural Chinese communities to a more urban context. An analytical model, derived ultimately from Alexander and based on the research questions outlined in the introduction the analytical plan, is used to assess both the context and the evolving nature of the wider social, cultural, spatial and architectural implications. This empirical research approach is used to explain and describe how the social and cultural structures of the neighbourhood are beginning to integrate and overlap with elements of built form in unexpected ways, hence showing signs of a semi-lattice, in deviation from the planned tree structure.

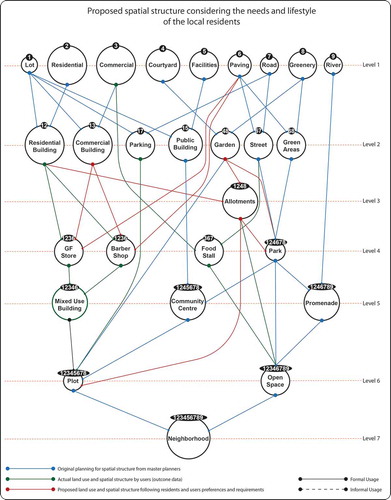

Data collection methods and quantitative modelling are used and include direct field observations to document adaptations to housing form and use from September until December 2012. The questionnaires and interviews were administered together with 100 residents. For the findings, Space Syntax and Grasshopper software has been used to create the evolving social and cultural structure as a model, based on Alexanders’ semi-lattice theory.

Using the case of Zhangjing and the survey data gained from it, findings from the research are presented in three parts in this paper. The first part describes and illustrates the residential housing types and usages in order to demonstrate the basic structure of the tree as a planning model. The second part describes the key unplanned variables that now exist within the community, evidencing social and cultural diversity, together with the actual characteristics of the transformation that is occurring to the form and occupation of the built environment. The final part takes on board Alexander’s prescription of the semi-lattice type to propose how at both a policy level and through physical change the needs of a local community may be better reflected and provided for.

Theoretical background

Based on a review of relevant contemporary urban theory (Friedmann Citation1973; Collier and Ong Citation2005; Zhang and Tong Citation2006; Gadanho et al. Citation2014; Robinson Citation2013), urban development in Zhangjing can be interpreted as a cross-sectional framework with diverse public and private usage, particularly housing, public open space, and commercial activities, while neighbourly social relations are represented through physical and social structure and reciprocal exchange. The paper also assesses the capacity within Chinese urban planning for reflective practice, the context of which was framed by Giddens some 20 years ago (Citation1994) in a way that still resonates:

The global experiment of modernity intersects with, and influences as it is influenced by, the penetration of modern institutions into the tissue of day-to-day life. Not just the local community, but intimate features of personal life and the self become intertwined with relations of indefinite time-space extension. We are all caught up in everyday experiments whose outcomes, in a generic sense, are as open as those affecting humanity as a whole. Everyday experiments reflect the changing role of tradition and, as is also true of the global level, should be seen in the context of the displacement and reappropriation of expertise, under the impact of the intrusiveness of abstract systems.

Marshall (Citation2009) also argues for an ‘evolutionary paradigm’ whereby the organic quality of cities can be acknowledged in the design and evolution of a planned community by not attempting to conceive of the end-product as a unified whole but as a ‘collection of interdependent, co-evolving parts.’

Trees and semi-lattices; a by-product of the development of Zhangjing community, Suzhou

Alexander’s distinction (Alexander Citation1972) between tree structures and semi lattices were drawn from observations of the evolution of social and village life and as such they offer parallels with how the district of Zhangjing has evolved from village to urban life, and from something resembling a tree structure to something that should be considered as a semi-lattice (see figure 1).

These urban changes highlight the difference in occupation between a newly planned and a traditional city and draws attention to the manner in which urban expansion occurs. Collier and Ong (Citation2005) use the contemporary Asian city to offer a somewhat different interpretation of Alexander’s ‘semi-lattice’, arguing that the city is now a ‘global assemblage’ of capital, politics and ethics, requiring an anthropological, and fine-grained assessment of the emerging urban situation and consequences. Robinson (Citation2013) also cites the importance of external influences, be they the global market or multiculturalism, in defining the contemporary make-up of cities. In contemporary China, the question of the effect of the transition from state regulated to a more informal system of housing management and provision, is particularly pertinent (Wu Citation2007) to understanding the match between users’ needs and design under these contrasting paradigms.

As a product of the process of urbanization and resettlement, rural-to-urban migration in particular can create complex, unplanned and unregulated outcomes within both the building and public space typologies. Countering Alexander’s thesis, Burdett (Citation2014) proposed that it is not that the planned community and ‘tree’ structure is fundamentally flawed per se, but rather that the rigid, unidimensional urban models that tend to be adopted lack the flexibility and robustness to adapt to the varied nature of occupation and usage that is becoming the norm within new urban communities. Robinson (Citation2006) further argued that the modernism that emerged in mid-twentieth century urban planning, and survives in some interpretation within planning offices and on drawing boards today, is no longer truly modern as it does not reflect or provide for the ‘newness’ of this complexity, and the importance of the local context and local requirements.

In the case of China, during the rapid urban transformation from the spatial and social landscape, one of the most important and visible products of this is the ‘urban village’ effect. While this urban transformation from villages to the urban cities, housing has been provided for the displaced residents from surrounding villages who have given up farming and have instead built or expanded housing to rent to migrants. To these villagers, rent has replaced agriculture as the main source of income. Urban villages can be found most commonly on the fringes of cities that have experienced significant expansion and received large number of migrants. These urban fringes surrounding Chinese cities have been referred to variously as urban outskirts, peri-urban areas, and suburban areas (McGee et al., Citation2007; Zhou and Logan, Citation2008). Hundreds of urban villages exist in large cities such as Guangzhou and Shenzhen. According to You-tien Hsing (Citation2009), there were 139 urban villages in Guangzhou in 2006, and urban villages in Guangzhou and Shenzhen make up more than, respectively, 20 and 60% of their planned areas providing homes to 80% of migrants in these cities.

Extending from Alexander’s tree structure and semi lattice theories, this evolution of social and village life offers parallels with how the urban village has evolved from a sustained rooted structure to something that should be considered as a semi-lattice.

Group-oriented leasing

The resettlement community of Zhangjing includes an adaptation of existing apartment buildings through the partitioning off of larger rooms within apartments into several small rooms (www.zhsw.gov.cn, 2012). The large floating migrant population that have arrived with a relatively low income have brought with them strong demand for low cost housing to areas that are experiencing high rates of inflation to the cost of rental housing in Chinese cities, with the group-oriented leasing offered by private landlords in response to this. The example of Zhangjing reflects a wider characteristic within China; according to local government statistics (www.zhsw.gov.cn, 2012), in 2011 the migrant population had grown to 78 million people, with 350,000 within the Suzhou and Suzhou Industrial Park area alone.

describes the area and the rural, sparsely populated context of small villages, towns and farmland surrounding Zhangjing prior to urban development. Zhangjing was originally designed for the permanent relocation of approximately 17,000 landless farmers from these surrounding rural villages and towns (Lee Citation2012). However currently, according to preliminary statistics recorded by a local community leader in Zhangjing (Lee Citation2012), the population of permanent residents within Zhangjing community is just over 5,000, whereas the temporary migrant population exceeds 20,000. A key driver for this population growth is the employment opportunities within the surrounding industrial and enterprise zones, and the entrepreneurial tendencies of many residents seeking to gain additional income through renting out their own apartments.

Figure 1. Diagrams of a semi-lattice and a tree.

A collection of sets forms a semilattice (to left) if and only if, when two overlapping sets belong to the collection, the set of elements common to both also belongs to the collection. A collection of sets forms a tree (to right) if and only if, for any two sets that belong to the collection either one is wholly contained in the other, or else they are wholly disjointed. Alexander argued that modern town planning, including the examples of le Corbusier’s Chandigarh, from 1951, and Lucio Costa’s Brasilia, from 1960, were based on this form of tree structure (source: Alexander Citation1972).

Figure 2. Before the urbanization of Zhangjing resettlement residential development area, dating back to1996 (source: Mr. Ma Jingbo, a Shengpu local photography enthusiast).

The Zhangjing original neighbourhood plan was completed in 2004, where displaced farmers from ten separate villages and a town were relocated together into a neighbourhood of 113 residential apartment blocks, within the urban area of Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) (see and ).

Figure 3. Location plan and aerial view showing the setting and layout of Zhangjing (source: Author, based on Google maps).

Resettlement residential development near the Zhangjing area. The overall development commenced in 1994, with the construction of Zhangjing commencing around 2000.

Each apartment block within Zhangjing has five floors, with two-bedroomed residential apartments on the upper four floors. The ground floor of each block was originally divided into six or eight garages for car parking. The present use has been informally changed into a range of convenience shops, hairdressers, repair shops of various kinds and more dwellings. The neighbourhood is located at the centre of the original town that was situated on the site, with a supermarket, entertainment functions, a public square and other services within walking distance. Zhangjing is one of 10 similarly planned and constructed neighbourhoods surrounding it.

In addition to the landless farmers from the surrounding area that have been resettled within Zhangjing, the community has also seen the arrival of economic migrants from across China, coming to work in the local construction and manufacturing industries. ‘Upgrading from village to neighbourhood’, a government-led approach to city planning that has contributed significantly to the urbanization rate in China (Zhang and Tong Citation2006), includes two objectives: first, to relocate landless farmers into resettlement neighbourhoods; and second, to change the Hukou (household registration) residency permit title of those resettled from an agricultural district to a non-agricultural district, in order for residents to be eligible to receive pensions and other forms of state support and subsidy of a similar level to the rest of the urban population.

With a long-term agriculture tradition, and a residency permit that is linked to a specific district, China’s government has never supported mobility; the policy of registering residents and forbidding migration date back to 200 A.D. in China (Deng, Hoekstra, Elsinga, Citation2014). Every citizen registers himself as a rural resident (nongcun Hukou) or non-rural resident (feinong Hukou) to a certain territory based on his mother’s Hukou category, with migration only by permission of their work units (Wu and Treiman, Citation2004; Huang and Dijst et al., Citation2014). The purpose of launching this system was to prevent rural-urban migration and to ensure that the limited production at that time can be allocated to specific groups of people; the local urban residents. This was a strategy to support modern industry development by giving less priority to agriculture and promoting construction in urban areas.

From the commencement of the socialist period in 1949 until 1978, the planned economy system, financial and physical resources were allocated within sectors. For example, a new industrial project was either planned and financed by industrial departments in the city government, or the provincial government, or for major projects with national importance, by the industrial ministry in central government (Wang, Citation1995). A factory, planned by the province or national government is usually more connected to the provincial or national government department than to the local city government where it is located. The larger part of the profit of these work units had to be submitted to provincial or national government and therefore local authorities felt no responsibility to provide accommodation for the employees of these organizations. Thus, work units set up housing offices that built and managed housing for their own employees.

Under the work unit system, the housing provision and allocation, along with other public services such as education and health care, became a means to realize a socialistic ideology. There are four main features of housing policy in this period. The first one is low rent policy, which demonstrates the ideal that housing should be affordable for every worker. By the end of 1950s, most big cities had managed to limit the rent-income-rate under 10%. The second is public provision and management; work units and local governments were both owners and managers of this welfare housing. The third is the collective form of public housing. Urban planners designed multi-story dormitories in which several families had their own bedrooms but shared kitchens and bathrooms. The fourth feature is to strengthen the linkage between work units and housing services. The authorities promoted work units to design, build and allocate housing to their workers according to the workers’ contribution to the society. The larger the contribution to society, which is most effectively measured by the work unit, the more living space they were allocated.

From the start of the housing reform in 1978 to the official termination of this reformed housing system in 1998, China was in a dual housing provision period. Two kinds of housing tenure were provided during this period: the Reformed Housing (fanggai fang or the privatized housing), and Commodity Housing (shang pin fang).

Reformed housing implied those dwellings that had been developed by work units or governments and sold to households usually at a subsidized price. During the reform, almost all the apartments owned by work units and local governments had been sold to households. These included former welfare housing referred to those dwellings built on leased urban construction land, developed by real estate developers, and sold in the open market.

Reformed housing and commodity housing are two different forms of homeownership. The main difference between them is the price and the property rights. Reformed housing was strongly subsidized and its price was much lower than commodity housing. Therefore, any for-profit actions such as letting or selling are forbidden. Later on, these regulations had been reduced to promote second-hand housing provision. After 1994, owners of reformed housing were allowed to sell the dwelling after 5 years of purchase, and they need to return part of the profit, usually 30% to the local governments or their work units.

After the housing reform decree in 1998, central government has officially forbidden work units to provide reformed housing to their employees, although they continued to do so at a smaller scale. China came into the market-dominant period of housing provision. Commodity housing was the main housing tenure promoted through government policy during this period.

In the late 2000s, the discussion about housing policies, both among scholars and decision makers, no longer focused on economy and real-estate industry only, but also on how to secure the equal housing rights of citizens and improve social inclusion. After 2011, the central government focuses more on subsidized housing provision and even more regulation towards commodity housing speculation. Large-scale subsidized housing schemes operated after 2011 and their focus shifted from low-income home ownership to rental housing. Currently, there is no clear data about the effects of these schemes on the housing tenure distribution. But in terms of new completions, the Chinese government constructed 19.5 million affordable dwellings from 2010 to 2013 (Liu, Citation2013).

The case of Zhangjing provides a good example of this housing, social and cultural reform. According to statistics supplied by the chairman of the local management committee (Lee Citation2012), the residents whose ’Hukou’ (household registration) is registered within this area number 5,071. However, this figure for the registered population is far smaller than the actual population. Lee estimated that there are more than 20,000 people whose household registered is elsewhere, mostly in other provinces of China.

The survey, led by Dr Ying Chang and conducted by a group of students from Xi'an Jiaotong - Liverpool University in 2011, also considers the demographic split of the community (sample size: 100). The outcome from the site analysis is presented in and .

Table 1. Survey of family size with each apartment and the number of generations living under one roof (source: Author).

Table 2. Survey assessing where each household previously resided (source: Author).

indicates that, if compared with the same community 10 years ago (Lee Citation2012), when landless farmers were the only social group within the resettlement neighbourhood, the socio-economic background of the residents has become much more diverse. The family households from elsewhere have become the biggest group in this community, followed by collective households.

These collective households are an unexpected social group that have arisen in what can be interpreted as a consequence of the low salary paid to economic migrants. An economic migrant in Zhangjing, Chan, responded to the survey, responded to a survey by stating ‘Governments and employers are reluctant to promise us public service and welfare foods. Without secure employment and access to public service such as formal housing and education, we workers just maintain a limited life here and try to bring as much savings as we can back to our rural home.’

A consequence of this has been the introduction of group-orientated leasing, whereby multiple occupants and families are living within apartments intended for one family. The leasing system is informal and led by individual landlords or apartment owners, who often allow agents to handle multiple leasing arrangements within one apartment, or in other cases landlords let out their apartment to an employer who subdivides it into dormitory style accommodation for employees from one company.

Between 30 and 50% of the households in Zhangjing are rented to migrant workers in this way, with each apartment divided up to accommodate up to 13–20 migrants, with those on night shifts often using the same bed during the daytime as those on day shifts. The way in which the typical apartment block floor plan has been adapted from the typical apartment arrangement shown earlier in . The spatial usage of one of these apartments is shown in .

Figure 4. Photographs that illustrate the farmhouse typology that previously existing in this area, in contrast with the new urban high-rise typologies being developed in their place (source: Author).

Figure 5. Adaptation of the existing floorplan (top) into the current arrangement of high density, group orientated leasing (bottom). (source: Author).

Figure 6. View of the occupation of an apartment fitted out as a dormitory group orientated leasing arrangement (source: newsela.com).

The survey indicates a number of general characteristics of the group-oriented leasing within Zhangjing. These can be summarized as follows:

In general, 2–4 people live in an 8–12-square metre apartment that are divided up from larger apartments of 40–60 square metres.

The majority of tenants are men and women in the18–40-year age range, of which a large proportion are migrant workers

Together with the survey, in an interview with a local government officer he stated that ‘although a new urban village may change over time, the planned layout of the apartments applies to a model of apartment occupation, size and family structure that does not reflect the current situation and adaptation. As such, the actual population of economic migrants is unaccountable. Regarding the usage of the public areas and the safety of the each household, we try are best but we cannot adapt to this changing density and unexpected pattern of usage. The demographics and inability to quantify the actual number of the shifting population within this area is a serious issue.’

Another government officer also stated ‘government-built housing was strongly subsidized and its prices were much lower than commercial housing. Therefore, any for-profit actions such as letting or selling are forbidden. But so many houses are renovated for sub-letting to economic migrants.’

An interview with residents of these group-leased apartments highlighted two points:

Although the local government officers are visiting and overlooking our neighourhood from time to time, they don’t address the actual problems we face, such as a lack of electric, inadequate water and fire alarm systems, safety issues and so on.

… they never invite us to speak about our needs and concerns. A couple of government officers came and checked the condition of our household and community centre and made some notes but they never come back with any suggestions for how we can live better here with consideration for the lifestyle of all of the different residents … it seems like they just ignore our problems …

From the site observation, the group leasing trend recognizes and reacts to the economic realities facing economic migrants and whittles down each unit of accommodation to its very basic functions of cramped sleeping quarters, minimal storage and shared bathing facilities.

Neighbourhood built environment

Informal usage of built form – economic characteristics

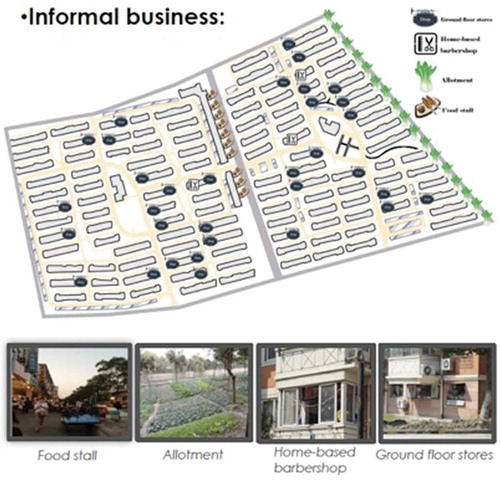

The commercial activities and usage of the Zhangjing neighbourhood can be divided into three types; first, outlets within the community shopping centre, second, outlets occupying the ground floor of apartment blocks and positioned along the street, and finally, so called ‘scatter businesses’.

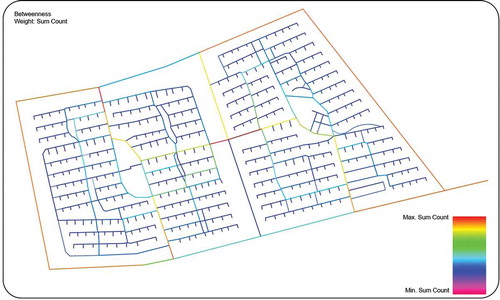

These outlets are located within a planned commercial cluster to the north of Zhangjing (see ). Space syntax modelling was conducted for the analysis of the urban configuration of Zhangjing to indicate density of traffic flow and usage (see ).

Figure 7. Zhangjing neighbourhood plan showing commercial and community facilities (source: Suzhou Industrial Park Surveying, Mapping and Geoinformation, CO., Ltd).

‘Scatter business’ is a Chinese term that refers to a style of informal, unplanned commercial activity. There are two types of scatter business that have been established in Zhangjing. First, there are small informal shops, hairdressers, and washhouses that have been set up in people’s homes or are run from the ground floor of the apartment blocks. Second, a series of street stalls primarily preparing food have been set up along the primary transport route; Huiling Street ().

Figure 9. Zhangjing neighbourhood plan showing informal commercial activity (source: Cong et al. Citation2012).

A survey of the three commercial outlet types within Zhangjing show that the dominant commercial type are the formal streetside outlets occupying the ground floor of the apartment blocks, the second-most common type is scatter businesses, and the outlets within the community shopping centre being the least common type. Evidence in terms of the number and type of commercial operation suggests that the unplanned scatter businesses have become an important part of the neighbourhood of Zhangjing. Likewise, evidence gathered from the questionnaires indicates residents’ use of the scatter businesses is relatively high. Results from discussions as part of a focus group meeting along with these questionnaires with local residents and migrant workers in the area highlighted the perceived benefits and popularity (in their view) of the scatter businesses (see ). The benefits included the fact that they are conveniently located, provide cheaper services and goods in comparison with other local restaurants and retailers, and are open for long hours, which makes them more convenient for migrant workers whose day often starts at 5am. The disadvantages of these businesses relates to the fact that they are unregulated, meaning that the waste they produce is not properly disposed of, and the fact that they have no safety or hygiene certificates.

In contrast to the scatter businesses, the ground floor commercial units (see ) appear to be more permanent and are officially regulated as well as offering products of a higher quality and cost and greater variety than those found in the scatter businesses. Findings from the focus group meeting and the survey indicate that users perceive two key benefits or positives to these commercial units: first they are seen as flexible to support different functions because of their small scale; and second they are more regulated in terms of hygiene and safety standards. On the other hand, they are seen as less convenient because of their shorter operating times.

Figure 10. Scatter businesses (source: Liu B, Liu C, Zhang L, Geng R. Citation2012).

Informal usage of built form – social characteristics

According to the Property Law of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国物权法) adopted in 2007, any common land within a residential neighbourhood belongs to all owners, with any behaviour or activity that impedes the right of use for all being forbidden.

In Zhangjing, the field work revealed that a number of residents are displaced and rehoused farmers, who without farming land are attempting to replicate a version of their former rural life (see ) by using the common land to grow shrubs and to dry vegetables in the sun. According to the 2007 Property Law, this activity is illegal as it reduces the area that others can use for recreation.

Figure 12. Informal use of green space and public areas within Zhangjing (source: Liu, B., Liu, C., Zhang, and Geng Citation2012).

The field work also showed that residents prefer sitting under buildings with their own chairs to sitting on the public benches provided, echoing the rural traditions in their home villages, in a setting approximating to where the majority of social activities would have occurred.

Moreover, there is an evident lack of communication and a clear divide in the community between the resident groups of landless farmers, the longer standing tenants of the community and the newly arrived migrant workers. This is partly due to the language barrier resulting from the difference in the dialects used by the local community to that used by migrant workers from other regions. The survey revealed that one of the only communal activities shared between these groups was informal outdoor evening dance sessions. One respondent said ‘both local residents and migrant workers are dancing together now’. Within the population of migrant workers, there are also clear social divisions in line with where the different groups originated. For example, when one migrant worker was asked whether he socializes with other migrant workers he responded ‘Seldomly. I only keep in touch with those coming from my hometown’.

Discussion

The emergence of urban villages is an outcome not only of rapid urbanization but also of the persistent divide between rural and urban citizenships and between rural and urban administrations in China (Zhang and Song Citation2003; Song Citation2008). From the demand side, millions of rural immigrants working in cities have generated enormous demand for inexpensive housing. Most rural migrants are excluded from the formal housing market because: (1) without urban Hukou (household registration), they are not eligible for low-cost affordable housing subsidized by city governments; and (2) they cannot afford ‘commodity housing’ in the private housing market. Therefore, migrant most commonly live in employer-provided housing such as factory dorms or rented rooms in urban villages.

From the supply side, as cities expand, municipal governments are motivated to acquire farmland for urban use. To minimize compensation for villagers’ housing and relocation and to ease the process of land acquisition, city governments tend to acquire farmland only and leave or return the land designated for housing – ‘reserved housing sites’ – to village collectives (Hsing Citation2009). Typically, these ‘rural’ land parcels are spatially scattered and receive no public service from city governments. However, since villagers are not required to pay a land lease fee for using these parcels, the cost and rent of housing built on such land is low and especially attractive to migrant workers who cannot afford high rent. To maximize rental income, villagers build high-density houses and add floors and structures haphazardly and even illegally, resulting in slum-like living environments (Tang and Chung Citation2002).

Urban villages in Chinese cities are not a result of land invasion and self-constructed housing by migrants (Mobrand Citation2006). Rather, they represent a match between migrants’ demand for cheap housing and the supply of low-cost housing in villages encroached upon by urban expansion.

However, high crime rates, inadequate infrastructure and services, and poor living conditions are just some of the problems in urban villages that threaten public security and management (Zhang, Zhao, Tian, Citation2003). Yet eliminating urban villages altogether is not a sustainable solution, unless provisions to re-house migrants are in place. Therefore, a better understanding of the housing demand and housing choice behaviours of migrants is crucial for developing effective strategies to better house migrants.

Designing places in the right order has a major impact on the quality of community life, but the right order for a place is often unexpected. To discover the right order of a particular place, we should begin by implementing any tiny improvements that are feasible. Specific spots or segments in a city that work well do so for a reason, and because they are naturally used by the community, these spaces form the ‘spine’ of the area and making good starting points for wider improvements. According to Alexander, small incremental changes will enhance the spirit of the place and encourage the accumulation of further changes. Using this approach, the case of Zhangjing neighbourhood can connect new spaces to allowing for change and adaptation through lived experience, especially, how a rural farmland community can evolve into an urban environment, and how the multi-cultural influences that come with this transformation can influence the local population who remain in residence

B.Chen, an architect and planner attending the case study workshop, argued that there are always new situations that urban planners and designers need to face, and that cities need to be able to adapt to meet the needs of a continually evolving society. Zhangjing provides a good instance of how the local government may need to adapt their policy and planned approach to this new community in order to foster ties between the local residents and the new floating population, thereby improving the quality of community and creating a shared sense of belonging.

The case of Zhangjing can also be critically reviewed in the context of Alexander’s argument that when a new urban development is created which is modelled or predicated on a tree structure to replace the semi-lattice that was there before, the city takes a step towards dissociating itself from its geographical and cultural context, or breaking that link altogether. In the context of the Zhangjing community, the dissociation in question can be seen in the way in which the former farming community has been replaced with a new urban model. An interesting development to the theory in Zhangjing’s case is that, the semi-lattice structure of this former farming community is attempting to reform and become enmeshed within the new urban tree, as can be seen from the survey findings and space syntax (see ) through the informal allotments and the inhabitant’s use of their own furniture within the public space and parking areas of Zhangjing neighbourhood. Extending the multi-tiered complexity Alexander’s theory for the semi-lattice refers to, this development can be seen as an example of a bottom-up attempt at community self-arrangement through community-led urbanism (Gadanho et al. Citation2014).

Judging from the research data, the social and cultural structures of this neighbourhood is showing signs of a semi-lattice, in deviation from the planned tree structure as defined by Alexander. The model also represent how at both a policy level and through physical change the needs of a local community may be better reflected and provided for. As a result, the influence that economic migration has on the planning of a community, its urban form and social fabric, can be considered in this evolving planning model. This might suggest that the lifestyle of the farmers and the nuanced social structures of the past cannot be simply erased or replaced by the new construction and rehousing. Instead, the social structures and farming habits of the rehoused farming community are asserting themselves through endeavours to adapt the new urban neighbourhood to old ways.

In addition to the former farming community, the economic reality of the floating population of economic migrants who have arrived in Zhangjing seeking employment is also effecting a transformation in the planned urban tree. The market rental value of the standard residential apartments that were planned and constructed in Zhangjing has proven to be unaffordable for this section of the community, such that the planned residential model and typology of the area cannot be sustained by those who live in them. As a consequence, unlegislated group-leasing of multiple occupants and families within single dwellings has emerged. This group also finds the planned provision of shops and eating establishments within the community unaffordable, and not meeting their needs. As a consequence, we see the emergence of scatter businesses, appropriating the public space of Zhangjing in an unplanned and unregulated manner. The residential dwellings and public space of Zhangjing are undergoing an unplanned transformation as the community seeks to adapt the urban environment planned and provided for them so that it better meets their needs.

Conclusion

In summary, this research paper can highlight the following three theoretical issues and design strategies.

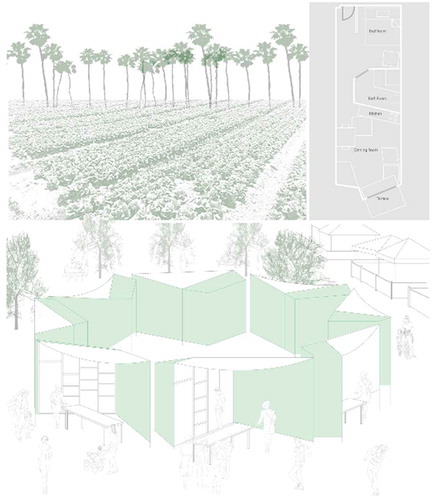

First, in relation to the future rapid development of neighbourhoods, the potential for designing more robust and flexible housing types merits attention. For example, the demographic of a growing workforce illustrated in the case of Zhangjing that is supporting the expanding local economy can be predicted and planned for, as can the fact that the typical housing typology of a multi-room family apartment that has been constructed en-masse will not necessarily suit (or be affordable to) these occupants. It can also be argued – as suggested by Alexander, and as inferred from the case study here – that neighbourhoods adapt more organically when construction is more evenly distributed over time, than when there is large and rapid urban change (see figure 13). For example, there is evidence of forms of architectural design and community engagement, in non-planned economies in the West, which at least echo the experience in Zhangjing, such as micro-living, pop-up restaurants and retail, and urban farming (see )

Figure 13. Evolving model for Zhanging neighbourhood social and physical structure) (source: Author).

Figure 14. Clockwise from top left- community urban farming in Singapore, micro living in London (streetview and plan), pop-up retail and restaurant in Paris (source: author).

Second, the findings from the different users’ opinions and needs from the case study interviews and workshop can provide practical clues for user-responsive, formally legislated and protected solutions to the needs of new (hybrid) Chinese communities. These might include community and rooftop allotments to provide landless farmers a rooted sense of place as well as a greater sense of ownership and pride to currently neglected landscape areas. A more formal system for scatter business could allow for newly designed, designated areas and refuse collection, cleaning and management systems. A review of existing building types might consider ways to better utilize currently neglected landscape areas and roof spaces.

shows a collage of these ideas and how they might be retrofitted into a planned community such as Zhangjing, to show how the ‘semi-lattice’ tendencies that are occurring within Zhangjing could be enmeshed as an additional planned layer within the ‘tree’, in a way that perhaps adds a level of adaptability and robustness to the urban plan by embracing the uncertainty and vitality of urban change.

This form of alternative urbanization challenges certain traditions of urban communities in China by creating a new permeable urban space that would arguably promote interactive relations and encourage encounters between residential, commercial and recreational users. Taken together, the different elements of the housing complex, including shared public space, might act as a catalyst for a richer and culturally responsive urban life.

Such a design response would be consistent with the studies reported in this paper that suggest the potential for social integration and democratic engagement of otherwise socially excluded urban residents is often realized through forms of small-scale, community-led architecture projects – implemented by inhabitants who are recognizing both the need and the commercial potential in providing for a diverse community in ways that formal planning processes have so uniquely failed to do.

In sum, when considering in practice how the production of new built form is operationalized by reflecting on some of the current conditions of urban planning and social structure, it can be argued that the social and cultural diversity that results may not follow the transition pattern from tree to semi-lattice as Alexander argues, and may instead be capable of other interpretations. Social and cultural diversity may arise in neighbourhoods that contain more local physical or social barriers to urban development than Alexander’s model anticipates, barriers that somehow foster social interactions. What is happening to local physical or social barriers not only brings into question the role that urban designers and planners have in terms of what is designed, but it also shifts the focus of analysis. For a city to remain receptive to life, social interaction, and human prosperity, it should unite the different strands of life within it. Planners and designers must therefore allow for a mix of functions and be open-minded to organic change.

It can be argued that Zhangjing’s particular circumstances and outcomes cannot simply be seen as an example of ‘top-down vs. bottom-up’, or of Alexander’s polemic ‘tree versus semi lattice’, but rather as an instance of a more subtle balancing of the processes of growth and disconnection.

The Zhangjing experience illustrates how the long-term empowerment of people and the appropriation of local resources are an important supplement to the master plan that invites people to take part. This is an example of a community-based approach to neighbourhood planning and re-planning that has been adopted and as a consequence has emerged as a defining characteristic of Zhangjing life. The group-oriented leasing phenomenon exemplified in this case, shows the structural contradictions in the supply and demand of housing in the urbanization process in China, and raises questions regarding the unregulated nature of the housing rental market and many other social and cultural issues of the disassociation between largely rural lived cultures and urban planned expectations.

The community dimension of this experience has to be carefully understood. The adaptation of built form along with its appropriation seems to follow not from a collective and co-ordinated response to a need, but from the needs of individuals acting independently in the same way. In other words, this experience should be characterized as entrepreneurial rather than political.

Third, highlights the alternative urbanization and occupation that is occurring within Zhangjing challenges certain traditions of planned urban communities in China. There is an opportunity to embrace this challenge and supplement the current planning and construction process by adapting to the needs of residents in a regulated manner. This could be in the form of a new or hybrid residential typology which might include the adaptation of secure micro apartments for those seeking lower cost accommodation, through landscape design in the allocation of a proportion of green space for urban allotments, or through the regulation of the ‘scatter-businesses’ that have emerged across the public realm with the provision of ‘pop-up’ al fresco dining areas. Developments to the urban plan such as these have, arguably, the potential to promote interactive relations and encourage encounters between residential, commercial and recreational users. Taken together, the different elements of the housing complex, including shared public space, might act as a catalyst for a richer and more culturally responsive urban life. At a policy level, this form of semi-regulated adaptation creates an argument for policy mobility within the central planning process that is not currently occurring, based on the experience of and consultation with the local community at the level of local government.

In light of this, it is important to identify more equitable and sustainable design and policy solutions to improve the lives of both migrant tenants and villagers within the rapid urban redevelopment in China. This would require a better understanding of the mechanisms of urban informality and a more inclusive approach to urban governance in terms of social and spatial sustainability which can represent the urban landscape of contemporary China.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hee Sun (Sunny) Choi

Hee Sun (Sunny)Choi Following higher education at RMIT in Melbourne, the AA School and UCL in London, Dr Sunny Choi completed her PhD in urban design at Oxford Brookes University and conducted Post-doctoral research at Oxford University. A specialist in digital infrastructure, cultural identity and environmental sustainability, she has practiced as an urban and interior designer in the UK, Hong Kong and in Seoul, South Korea, and within the design and master planning department of the United Nations Headquarters in New York. Together with professional practice, Sunny has held teaching posts at Oxford Brookes, Liverpool University, the AA Summer schools programme and as visiting lecturer to various universities in London and South Korea. In addition Sunny has undertaken research work and achieved funding at the University of Oxford, Seoul University and Liverpool University. Sunny has published a large number of publications and regularly presents papers in international conferences.Currently she is a lecturer at Hong Kong Design Institute and co-director at CHOI-COMER ASIA Limited (Architecture and Urban design Practice and Research Lab) in Hong Kong.

Alan Reeve

Dr Alan Reeve is Reader in Planning and Urban Design in the Joint Centre for Urban Design and the School of the Built Environment at Oxford Brookes University. His particular research and teaching interests lie in townscape analysis and evaluation, town centre management and conservation-led urban regeneration. He is currently involved in a number of research projects for the Heritage Lottery Fund and Transport for London. He is also part of a team from the Joint Centre for Urban Design engaged in delivering training in all aspects of urban design to both public and private sector clients.

References

- Alexander C, 1972. “The city is not a tree”, in Human Identity in the Urban Environment Eds Bell G, Tyrwhitt J (Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middx) pp 401–428.

- Burdett, Ricky 2014. Lecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design, 25th February 2014. Accessed via internet on 12th December 2014 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wm-dB_D0FLk&list=PL9GhDDeOvyXJGrHNQCI4A2uitLebfhwhn&index=5

- Collier, S. J. and Ong, A. 2007. Global Assemblages Anthropological Problems, in Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems (eds A. Ong and S. J. Collier), Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK.

- Cong C, Yinian Z, Xiaoxiao H, Dan L. 2012. Neighbourhood planning for large scale resettlement community of landless farmers in Zhangjing. Suzhou, China: Planning Methodology coursework, Urban Planning and Desing, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University. Unpublished.

- Deng Hoekstra 2014. Conference paper, Proceedings of New Researchers Colloquium ENHR 2014 Conference, Beyond Globalisation: Remaking Housing Policy in a Complex World, Edinburgh (United Kingdom), 1-4 July, 2014; ENHR

- Friedmann J. 1973. The spatial organization of power in the development of urban systems. Dev Change. 4(Issue 3):12–50.

- Gadanho, Pedro and Burdett, Richard and Cruz, Teddy and Harvey, David and Sassen, Saskia and Tehrani, Nader 2014. Uneven growth: tactical urbanisms for expanding megacities. . The Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA.

- Giddens, A. 1994. Living in a Post-Traditional Society. In U. Beck, A. Giddens, & S. Lash (Eds.), Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order (pp. 56–109). Cambridge, England: Polity.

- Hsing Y. 2009. Urban housing mobilizations. In: Hsing Y., Reclaiming chinese society: the new social activism. London: Routledge. p. 17-41.

- Huang, X., Dijst, M., van Weesep, J. et al. J Hous and the Built Environ 2014. 29:615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-013-9370-5

- Lee X 2012. Zhangjing neighbourhood commiittee leader, Personal Interview note.

- Liu B, Liu C, Zhang L, Geng R. 2012. Neighbourhood planning for large scale resettlement community of landless farmers in Zhangjing. Suzhou, China: Planning Methodology coursework, Urban Planning and Desing, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University. Unpublished.

- Liu Z, Wang YTao R. 2013. Social capital and migrant housing experiences in urban china: a structural equation modeling analysis. Housing Studies. 28(8):1155-1174.

- Marshall S. 2009. Cities design & evolution. London: Routledge.

- McGee T. G., et al. 2007. China’s urban space: development under market socialism. London, UK and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Meng X. 2012. Labour market outcomes and reforms in China. J Econ Perspect. 26:75–102.

- Migration data for China and Suzhou, [ accessed 2012 Sep 14]. www.zhsw.gov.cn.

- Mobrand E. 2006. Politics of cityward migration: an overview of china in comparative perspective. Habitat International. 30(2):261-274.

- Partanen, J. 2015. 'Indicators for self-organization potential in urban context' Environment & Planning B: Planning and Design, vol 42, no. 5, pp. 951-971.

- Robinson, J., 2006. Ordinary cities: between modernity and development (Vol. 4). Psychology Press.

- Robinson J. 2013. ‘arriving at’ urban policies/the urban: traces of elsewhere in making city futures. In: So ̈ derstro ̈ m O, Randeria S, Ruedin D, et al. (eds) Critical Mobilities. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 1–28.

- Song Y. 2008. Case study of the community development of neighbourhoods of landless farmers (in Chinese). City Issues (009). 73–76.

- Suzhou Development and Reform Commission. 2008. Suzhou Community Special Plan Note. Accessed online on 13.12.2014 at http://www.is.xinhuanet.com/xin%20wen%20zhong%20xin/2008-12/03/content%2015087507.htm.

- Tang W.-SChung H. 2002. rural-urban transition in china: illegal land use and construction. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. 43:43–62.

- Vaughan LS, Griffiths S. 2013. A suburb is not a tree. Urban Des. 125(Winter):17–19.

- Wang Y.P. 1995. Public sector housing in urban china 1949–1988: the case of xian. Housing Studies. 10(1):57-82.

- Wu F. 2007. Urban development in post-reform China. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Wu XTreiman D. 2004. The household registration system and social stratification in china: 1955-1996. Demography. 41:363-384.

- Zhang H, Tong X. 2006. The social adaptation of landless farmers in the urbanisation process in China. Soc Sci Stud (In Chinese) 1). 128–134.

- Zhang K.HSong S. 2003. Rural–urban migration and urbanization in china: evidence from time-series and cross-section analyses. China Economic Review. 14(4):386-400.

- Zhang L.S.X.B, Zhao Simon X. BTian J.P. 2003. Self‐help in housing and chengzhongcun in china's urbanization. International Journal Of Urban And Regional Research. 27(4):912-937.

- Zhou Y.Logan J. R. 2008. Growth on the edge: the new chinese metropolis, in urban china in transition (ed j. r. Logan), Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK. doi:10.1002/9780470712870.ch6