ABSTRACT

Informal settlements are increasingly becoming a concern for many developing countries. Most of the people living in informal settlements do not have formal property ownership documents. As a result, properties in such settlements have relatively less value and security of tenure and thus can hardly be used as collateral for credit. Giving property owners formal land ownership documents through informal settlements regularisation is one of the measures to address the problem. Using six regularised settlements in Tanzania and employing institutional approach, this paper identifies and assesses factors affecting land title application and uptake. Findings show that title application rate and uptake are still low mainly due to inhibitive institutional constraints such as negative customs and beliefs; poverty; high lending rates; low financial literacy; land related taxes and charges and; outdated laws. These findings underscore the imperativeness of undertaking a comprehensive institutional environment analysis while designing and executing regularisation projects.

1. Introduction

Informal settlements are increasingly becoming a serious concern for many urban centres in developing countries. These settlements normally have poor basic infrastructure and most of them are densely populated, inhabited by poor people and associated with high crime rate. In Tanzania, it is estimated that more than 70% of the people living in urban areas reside in informal settlements (UN-Habitat Citation2012). Considering the population growth and urbanisation rates of about 2.7% and 3%, respectively, the problem of informal settlements is likely to compound over time (NBS Citation2016). Most of the people living in informal settlements do not have land titles or any other form of formal property ownership documents. As a result, properties in such settlements have relatively less value and security of tenure and thus can hardly be used as collateral for credit from conventional financial institutions.

In a bid to address the problem, different countries have been attempting several interventions including implementing property formalisation and informal settlements regularisation programmes. Such programmes have largely focused on issuing formal ownership documents such as land titles and residential licenses to property owners. For instance, in Tanzania, most of the informal settlements regularisation initiatives are carried out under specific programmes executed through several small projects in different parts of the country. The projects entail planning, surveying, and registering land owners and giving them land titles after paying statutory fees and charges. There are three notable programmes under which informal settlem-ents regularisation projects are undertaken. These are Unplanned Urban Settlements Regularisation Programme, Property and Business Formalisation Programme (MKURABITA) and the National Programme for Regularisation and Prevention of Unplanned Settlements. By March 2018, about 103,065 plots had been surveyed under regularisation arrangement (MLHHSD Citation2018). Some of the regularised settlements are in the following urban centres Kinondoni (7,153 parcels surveyed), Ubungo (33,371 parcels), Temeke (1,783 parcels), Moshi (2,290 parcels), Dodoma (5,651 parcels), Singida (2,710 parcels), Mwanza city (19,635 parcels), Ilemela (20,200 parcels), Iringa (1,750 parcels), Njombe (1,637 parcels), Makete (931 parcels), Morogoro (898 parcels), Bunda (3,252 parcels), Busega (3,874 parcels), Songea (4,150 parcels), Lindi (2,300 parcels), Musoma (3,017 parcels) and Tabora (4,400 parcels).

Informal settlements regularisation received widespread attention following the release of a book by De Soto (Citation2000) which, among others, strongly advocated for issuance of formal property ownership documents to property owners in informal settlements. The main argument advanced was that such documents would enable property owners to access credit, and thus be able to use their properties as capital. However, this proposition is widely criticised for being simplistic and not considering the diversity and dynamics of the different economies and society settings characterising developing countries. Using evidence from five regularised settlements in Tanzania, this paper identifies and assesses the factors affecting land titles application rate and uptake. The paper employs institutional approach in assessing the selected regularisation projects.

2. Literature review

There are many authors who have written about regularisation of unplanned settlements in developing countries. The debate and literature on the subject became more pronounced after the release of a book by De Soto (Citation2000) which, among others, strongly argues that if property rights are enhanced through issuance of land titles, property owners in informal settlements can use their properties to access credit thereby turning dead capital into live capital. This debate has been mindful of the fact that many urban property owners in developing countries are denied access to credit because they do not have formal property ownership documents (Nyamu-Musembi Citation2007; Domeher and Abdulai Citation2012; USAID Citation2012). Land titles are important because lenders are more comfortable advancing loans to property owners who have titles and are willing to use them as security for credit (Trebilcock and Prado Citation2011).

Whereas many authors generally support De Soto’s view, some of them have shown reservations by citing various reasons. Based on empirical studies carried out in different regularised urban settlements, some authors show practical challenges in turning dead capital into live capital which are far more complex than merely giving titles to property owners. For instance, Home and Lim (Citation2004) argue that if land titling is to be effective in leveraging poor residents out of poverty, the process needs to be supported by enabling policies, systems and services. Sjaastad and Cousins (Citation2008) criticise De Soto for not considering the cost associated with obtaining and sustaining land titles. The authors cite initial costs of acquiring a title and the costs associated with having a title. Such costs include increased exposure to multiple taxes and charges resulting from the increase in the value of the respective land and buildings. High cost of acquiring a title has also been reported by Ayalew et al. (Citation2013), who note that some property owners in Kinondoni, Dar es Salaam Tanzania were not willing to pay TZS 150,000 to cover cadastral survey cost, claiming that the amount was unaffordable for them. Nyamu-Musembi (Citation2007) also reports a similar experience in Kenya noting that many registered land owners had not collected their titles from the land registry several years after formalisation exercise partly due to outstanding fees. Underscoring the significance of the cost of obtaining a land title and all other costs associated with keeping the title has led Haas and Jones (Citation2017) to suggest that programmes aiming at providing land titles to millions of poor households may not be successful.

In some cases, property owners show little interest in land titles. Such observation is made by Chiwambo (Citation2017) who reports that, some property owners in informal settlements in Tanzania simply do not consider land titles to be important. Some of the reasons explaining this attitude, as noted by the author, include low financial literacy, fear of being exposed to land related taxes and lack of awareness on the importance and use of land titles. This can be further seen in the lacklustre response shown by some registered land owners in Dar es Salaam in collecting their titles from the land registry. The Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development (MLHHSD) has been urging property owners to go and collect their land titles from the land registry as more than 3,000 titles had not been collected for a long time despite their owners having paid all the fees (MLHHSD Citation2017). The same observation was made by Byamugisha (Citation2016) who reports that out of 8.4 million land titles that had been issued in Rwanda by 2013, only 6.1 million titles, which is 60%, had been collected by the property owners. The author further notes that despite low fees being charged, some property owners still showed little interest in land titles.

Availability of informal sources of capital not requiring a land title to access has also been cited as one of the reasons for some people not to consider borrowing money from formal financial institutions (Kyessi and Furaha Citation2010; Chiwambo Citation2017). For instance, FinScope (Citation2017) shows that a large number of borrowers in Tanzania still rely on informal sources of finance. The study shows that 69% of the people borrow money from family members and friends, 18% from informal saving groups, 4% from mobile money, 3% from banks, 2% from money lenders, 2% from micro lenders, 1% from religious organisations and 1% from employers. Durand-Lasserve and Payne (Citation2006) also note that, in Mexico people who have land titles show little interest in formal credit but they prefer borrowing money from friends and relatives. A similar study carried out earlier in Tanzania and Kenya by Ellis et al. (Citation2010) identifies three sources of borrowing in the two countries namely formal, semi-formal and informal. The authors note that in Tanzania, 62% of the borrowers borrow money from informal sources, 40% from semi-formal sources and 20% from formal sources. Further, the authors cite too low income, high interest rates, absence of financial institutions in the vicinity and lack of required documents, as some of the reasons hindering some people from borrowing money from formal lending institutions.

Against such a background, it is understandable why some people do not consider land titles as an important means of accessing credit. Besides, a land title alone does not make one qualify for a loan from a formal lending institution. Sheuya and Burra (Citation2016) note that banks have other requirements other than land titles which make loans only accessible to people with profitable businesses or stable income, in addition to having land titles. A large section of the population in developing countries does not qualify for bank loans due to stringent terms and conditions. For instance, Kyessi and Furaha (Citation2010) report that administrative procedures, terms and conditions set by banking institutions act as barriers for the poor to access loans in Tanzania. This has forced low income households to revert to alternative sources of capital which do not require borrowers to place land titles as collateral. Ahiakpor (Citation2008) emphasises that De Soto was not realistic about the real problems characterising developing countries. The author argues that lack of titles was not the reason for not being able to access credit; instead the problem was lack of saving to finance investment. Therefore, massive formalisation programmes may not necessarily address the problem.

A study carried out by Finmark (Citation2011) shows that only 3% of people in Tanzania qualify for mortgage loans because it is the only proportion of the population that earns at least TZS 200,000 per month, which is the least amount that mortgage lending institutions would normally require, as monthly income, from borrowers. Many of the borrowers only qualify for small loans whose lenders do not necessarily demand land titles; instead they normally require borrowers to use either vehicle ownership documents or property sale agreements as collateral (Chiwambo Citation2017). The author further notes that some people in Tanzania are averse to borrowing as they regard borrowing to be a shameful act in the society. This perception may be a reflection of culture or may have partly been aggravated by the suffering that some borrowers have endured as a result of losing their properties on foreclosure. Culture as one of the institutional pillars elements, plays an important role in constraining people’s behaviour. Samuelson (Citation2001) and Manders (Citation2004) also cite cultural differences as one of De Soto’s proposition oversights.

Besides, access to credit is not the only use of land titles; there are other factors that attract property owners to apply for land titles. One of the factors include property value enhancement. Okyere et al. (Citation2016) note that in Peru property owners with titles increased their income to about 20%–30% without getting access to credit. The authors further note that titles increased the value of people’s property. Therefore, people could rent and sell their properties and get capital to start businesses and generate income. Krishnan et al. (Citation2016) also observe that land titles in India help the government to raise revenue from property owners. The author further note that property owners also consider land titles to be important in vindicating land ownership but not necessarily for accessing loans. The case of India is similar to that of Tanzania where the law requires all land owners with titles or letters of offer to pay land rent. The law is however silent on land owners who do not have such documents.

More studies show that land titles particularly matter when it comes to sale transactions of the subject land. A study carried out in Tanzania by Sanga (Citation2017) shows that undeveloped land plots with titles have more value than developed land plots with titles. The author notes that for built plots, a title does not seem to attract premium when it comes to sale transactions. Another study conducted in Tanzania by Durand-Lasserve and Payne (Citation2006) also shows that lack of legal titles has complicated the process of selling and transferring a property. According to Dam (Citation2006), in Brazil and Indonesia, the price of land increased after land being titled.

De Soto argues that enhancement of property rights is necessary in turning dead capital into live capital. However, various authors have advanced varying ideas basing on empirical evidence from different studies testing out De Soto’s proposition in different settings. Although, in principle, many of the authors support the proposition, most of them consider it to be rather simplistic in the sense that it does not give due consideration to societal diversity and dynamics. It is considered in this study that, most of the arguments raised by different authors criticising, improving or supporting the proposition can be better explained using an institutional perspective.

The underlying argument of this paper is that for any regularisation programme to achieve its intended goals, it has to be designed and executed with the institutional environment of the respective setting in mind. Broadly, institutional environment refers to the system of formal laws, regulations and procedures, and informal conventions, customs and norms that broaden, mould, and restrain social-economic activity and behaviour (Becchetti and Kobeissi Citation2009). The institutional environment prevailing in a particular society defines the activities and actions of the members of the society in question (Kusiluka Citation2012). A property market exists within an institutional framework defined by political, social, economic and legal rules and conventions by which the society in question is organised (D’Arcy and Keogh Citation1999).

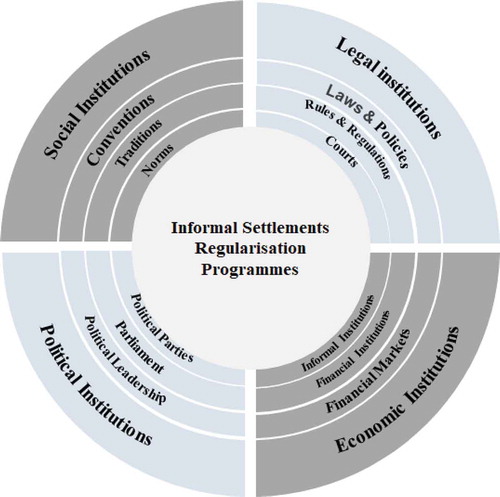

As shown in , the institutional environment is defined by four pillars namely, social, legal, political and economic institutions. Each of the pillars plays an important role in determining success or failure of any activity undertaken in a particular society. Political institutions, mainly covering political leadership, political parties and the parliament, are important in terms of assessing political risk and support in respect of regularisation programmes and in the enactment of relevant policies and laws. Social institutions, comprising mainly culture, norms and traditions, determine the attitude and behaviour of informal settlements dwellers with respect to the implementation and outcome of regularisation programmes. Economic institutions, covering financial markets, financial institutions and informal financial services arrangements, determine the supply and demand of capital and the cost of capital, which are central to economic empowerment of informal settlements dwellers. Legal institutions, comprising policies, laws, rules and regulations and courts, are linked to regularisation programmes in terms of physical planning, land tenure, property rights, land taxation, mortgage and land related courts.

Most of the existing empirical studies on property formalisation and informal settlements regularisation do not give a comprehensive critique of De Soto (Citation2000) proposition as they leave out some of the key institutional spectrum elements defining the settings under which the studies were carried out. This paper therefore contributes to the existing literature by introducing the institutional approach dimension to the assessment of informal settlements regularisation programmes. The approach is aimed at providing a more comprehensive understanding of the various factors that have to be taken into account when designing and executing such programmes. It is thus posited in this study that for any informal settlements regularisation programme to be effective, its design and execution have to be cognizant and reflective of the prevailing institutional environment.

3. Methodology

Five different informal settlements with significantly differing features were selected for this study. These settlements are Kimara and Makongo Juu both in Dar es Salaam city, Tuelewane in Morogoro Municipality, Idundilanga in Njombe Town and Tandala in Makete District. These settlements were purposively selected considering their diversity and information richness. Regularisation activities in these settlements were at different stages and were carried out under different arrangements, thereby providing room for comparison.

Although regularisation activities are normally undertaken in densely built-up and highly populated neighbourhoods, some of the settlements being regularised in Tanzania are defined by the opposite features. Cognizant of this fact, the selection of case examples for this study considered such diversity by including informal settlements accommodating both extremes. Both densely populated low-value property neighbourhoods and sparsely populated high-value property neighbourhoods were included for investigation. Kimara, Tuelewane, Indundilanga are typical of densely populated and generally low-value property neighbourhoods while Makongo Juu and Ikonda are less densely built-up and sparsely populated neighbourhoods. Makongo Juu is characterised by generally high-value properties.

For each settlement studied, key personnel from the MLHHSD and the respective Local Government Authorities (LGAs) who took a leading role in the design and execution of the particular project were interviewed. In total, 4 MLHHSD and 10 LGAs officials, were interviewed. In addition, 6 officials from different banks and a senior official from MKURABITA were interviewed. Thereafter, a questionnaire was administered to selected property owners in the regularised settlements in Njombe, Makete and Morogoro. The settlements were purposively selected because of their relatively large number of property owners who had already fully paid for their titles. A systematic random sample was drawn and a questionnaire was administered. A total of 89 property owners, 30 from Njombe, 30 from Makete and 29 from Morogoro returned a filled out questionnaire. The small sample size was necessitated by the questionnaire administration method employed, which entailed research assistants meeting each of the respondents personally and providing clarification whenever required. This approach was taken in order to eliminate chances of misinterpretation of questions and to increase response rate. Accordingly, 98.9% response rate was achieved. Although the number of respondents was 89, the total number of land parcels covered in the survey was 95 because some respondents had more than one land parcel. The survey was supplemented by the interviews with key informants from the MLHHSD, LGAs, selected banks and MKURATBITA. Thematic analysis was applied to analyse interview data while SPSS was used to analyse data collected using a questionnaire.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Respondents’ basic attributes

Out of 89 respondents, 65.2% were male and 34.8% were female. 36.8% of the respondents were aged between 46 and 55 years, 29.9% between 36 and 45 years, 16.1% between 56 and 65 years, 11.5% between 20 and 35 years, 4.6% between 66 and 75 years and 1.1% were aged above 75 years. 38.3% of the respondents were engaged in agriculture, 29.6% were engaged in small businesses, 7.4% were employed in the formal sector, 6.2% were retirees, 1.3% were engaged in livestock keeping, 1.2% were housewives and 16.0% had other jobs. 62.4% of the respondents earned a monthly income of below TZS 100,000, 30.6% between TZS 100,000 and 500,000, 5.9% between TZS 500,001 and 2,000,000 and 1.2% earned a monthly income of above TZS 2,000,000.

4.2. Planning, surveying and titling costs

Although regularisation is generally meant to assist poor people owning properties in informal settlements, it was noted that the cost of regularisation was relatively high which to a large extent discouraged some people from participating in the exercise. This was evident in some of the settlements covered in this study. Regularisation projects at Idundilanga (Njombe), Tandala (Makete) and Tuelewane (Morogoro) were carried out under MKURABITA programme. MKURABITA required property owners to pay only a portion of the total costs and the rest was covered by the programme. The respective LGAs were required to provide staff for planning, surveying and overseeing the exercise. For instance, it was noted that at Tandala, to get a land title, a land owner had to pay only TZS 200,000 for a residential land plot, TZS 250,000 for a residential cum commercial land plot and TZS 300,000 for a commercial land plot. At Tuelewane and Indundilanga, property owners were required to pay TZS 120,000 and between TZS 120,000 and TZS 350,000, respectively, for planning and surveying in addition to statutory fees and charges for titles.

On the other hand, regularisation activities at Kimara were directly executed by the MLHHSD which covered planning and surveying costs and land owners were required to pay some amount of money ranging between TZS 100,000 and 140,000 to cover some operational costs and basic infrastructure installation. At Makongo Juu, the regularisation exercise was community based. A committee, namely KAUMAMA, was formed by the community to oversee the exercise. The MLHHSD and Kinondoni Municipal Council had some technical staff stationed at Makongo Juu to guide the exercise and process land titles applications onsite. Land owners were required to pay for planning, surveying and all statutory title related costs namely premium, registration fee, title fee, deed plan fee, land rent and stamp duty. Each land owner was required to pay TZS 450,000 upfront to cover planning and surveying costs. Thereafter they had to pay for the land titles. This was noted to be too expensive and was one of the main reasons for low title application. For instance, a land owner of a plot measuring 1000m2 in Makongo Juu was required to pay a premium of TZS 875,000 to have a land title while the owner of a similar size plot in Kimara was required to pay TZS 375,000.

4.3. Extent and reasons for land title holding

It was noted that generally the rate of applying and paying for land titles was low. Observations made in January 2018 showed a wide gap between the number of surveyed plots and the number of land titles paid for in each of the selected settlements. At Kimara, 6,000 plots were demarcated and survey plans for 4,500 plots were registered. Whereas 2,000 invoices were prepared only 745 had been collected by property owners and 153 land titles were fully paid for, which is only 3% of the surveyed plots. At Makongo Juu, 3,200 plots were demarcated, survey plans for 2,800 plots registered and only 100 land titles had been fully paid for, which is only about 4% of the surveyed plots. At Tandala, 1,358 plots were demarcated, survey plans for 724 plots registered and 302 land titles had been fully paid for, which is about 42% of the surveyed plots. At Tuelewane, 558 plots were surveyed, 233 land titles had been fully paid for, which is about 42% of the surveyed plots. At Idundilanga, 1,845 plots were surveyed, 1,102 land titles had been fully paid for, which is about 60% of the surveyed plots.

Average title application rate in the 5 settlements was 30.4% of the surveyed land parcels available for titling. The rate differed among the settlements mainly because of costs, sensitisation campaigns, age of the regularisation project and involvement of potential lenders in project execution. For instance, Njombe had the largest percentage of land titles which were fully paid for followed by Makete and Morogoro. The regularisation project in Njombe started in 2009 and it is the oldest of the five projects selected. It was also noted that regularisation activities in Njombe were accompanied by aggressive sensitisation activities coupled with active participation of potential lenders including banks. As a result of that, out of 1,102 fully paid for titles, 1,060 titles had been collected and 56 titles had been used as collateral for loans.

Although regularisation project in Makete started in 2016, a relatively high percentage of fully paid for land titles was reported. This was mainly due to the fact that, the cost of a land title was the lowest compared to the projects in the other four settlements. Property owners in Makete were required to pay between TZS 200,000 and TZS 300,000 in total to get a land title. It was noted that the cost of getting a land title in Dar es Salaam was the highest mainly because property owners were required to pay for full planning and surveying costs (at Makongo Juu) and partial cost (at Kimara). Besides, land values in Dar es Salaam are higher than in the rest of the settlements implying that the amount of premium per unit of land is higher compared to the rest of the settlements. Premium was 2.5% of the market value of the land plot and it was charged upon granting a land title.

It was also noted in some settlements that although property owners were required to pay only a portion of the total cost, the rate of applying and paying for land titles was very low. For instance, at Kimara, property owners were only required to pay between TZS 100,000 and TZS 140,000 to cover some operational costs and basic infrastructure but only 3% of the land owners had paid for land titles. This was slightly different at Makongo Juu where land owners were required to pay TZS 450,000 to cover full planning and surveying costs, 4% of land owners had paid for their land titles. This suggests that the low rate of applying for land titles is partly contributed by lack of awareness amongst property owners on the importance of having land titles.

Out of the 89 respondents, it was also noted that there was a slight difference between the number of property owners who had land titles and those who did not have them. 51.7% of the property owners amongst respondents had land titles while 48.3% did not have. Those with land titles cited different reasons that motivated them to have titles. 47.8% of them wanted land titles to enhance security of tenure, 34.8% wanted titles for accessing credit, 8.7% for court bail, 4.3% for being recognised by the government and 4.3% for resolving conflicts. It is also worthwhile noting that the percentage of the respondents with titles was slightly lower than the proportion of titles that had been paid for. Out of 3,127 surveyed land parcels in the three neighbourhoods, titles for 52.3% of the land parcels had been paid for. The difference is likely due to delays in title processing.

On the other hand, those who did not have land titles cited different reasons for not having land titles. 24.3% of them cited inability to pay as the reason for not having land titles, 18.9% cited high cost of acquiring and maintaining land titles, 10.8% did not have land titles because they had not yet paid for them, 5.5% cited long and complicated procedures of getting a land title, 5.4% did not have land titles because they were not aware about the importance of land titles. In addition, 29.7% did not have land titles but they were in the process of getting them and 5.4% wanted to have land titles but they had a problem identifying their plots due to multiple allocation.

Analysis further shows that 79.1% of the respondents who had land titles had used them for some purposes. Respondents who had used their land titles cited different uses of land titles. 69.8% of them had used their land titles to borrow money from financial institutions and 9.3% had used as bail in courts. Out of 33 property owners who had borrowed money from financial institutions, 69.7% were male and the rest were female. Respondents who had borrowed money from financial institutions cited different purposes of borrowing money. 53.6% of them had borrowed money for starting businesses, 32.1% for expanding businesses, 10.7% for taking children to school and 3.6% for repairing houses. Whereas 75% of the respondents had used their land titles as collateral to access loans, 25% of the respondents had borrowed money without using their land titles as collateral. These property owners cited fear of foreclosure and high interest rates as the main reasons for not using their titles as collateral. Low financial literacy was also noted to be one of the factors accounting for the low title application and update. It was further noted that loan repayment term ranged between 1 and 3 years and the average loan amount was TZS 9,700,000. None of the respondents had taken a mortgage.

4.4. Institutional environment analysis

4.4.1. Policy and legal constraints

A review of pertinent policies shows that all policies are supportive in empowering property owners in informal settlements by enhancing the value of their properties in different ways. The National Land Policy of 1995, the National Human Settlements Development Policy of 2000 and the National Economic Empowerment Policy of 2004 recognise and support regularisation activities. Paragraph 6.3.1(i) of the National Land Policy of 1995, which is the basis of the Land Act Cap 113, states that all interests on land including customary land rights that exist in the planning area shall be identified and recorded. The policy, under paragraph 6.4.1(iv), further states that upgrading plans will be prepared and implemented by local authorities with the participation of residents and their local community organisations, and local resources will be mobilised to finance the plans through appropriate cost recovery systems.

The National Human Settlement Policy of 2000 is also categorical on the need for upgrading informal settlements. Paragraph 4.1.4.2(i) of the policy states that unplanned and unserviced settlements shall be upgraded by their inhabitants with the government playing a facilitating role. Most of the regularisation activities in Tanzania have been undertaken with the two policies spirit. In all the projects covered in this study, there has been considerable community engagement with project cost sharing or cost recovery arrangements being used.

The National Economic Empowerment Policy of 2004 also promotes the use of land titles in accessing loans. The policy (paragraph 4.9.2) states that, the government will use land as an important tool in empowering Tanzania citizens to participate fully in economic activities. The policy is also cognizant that using land as a means for accessing loans cannot achieve significant results without getting the land surveyed and registered. One of the policy strategies is ensuring that regulations made under the Land Act, 1999 are adhered to so that land titles are used as collateral for bank loans. Another strategy is speeding up land surveying in urban and rural areas and improving procedures for issuing land titles so that land is used as an investment tool.

Regularisation is also well covered in the Land Act of 1999 Cap. 113. Section 56 to 60 of the Land Act cover various aspects of regularisation. The Land (Schemes of Regularisation) Regulations of 2001 give details of the steps and procedures to be followed when carrying out regularisation activities. The Land Act came into force in 2001, around the time when De Soto’s work was released. Implementation of De Soto’s ideas became easier because the policy and legal environment was already accommodative. Section 57(2)(b) of the Land Act states that a scheme of regularisation should be declared where a substantial number of persons living in the area appear to have no apparent lawful title to their use and occupation of land. Section 57(2)(g) further provides that a scheme of regularisation may be declared if there is evidence that despite the lack of any security of tenure for the persons living in the area, a considerable number of such persons appear to be investing in their houses and businesses and attempting to improve the area through their own initiatives. The regularisation project areas covered in this study were all selected on the basis of the cited provisions of the Land Act.

Mindful of the existence of a large number of land related conflicts, especially in informal settlements, a special court system has been put in place to deal with land related civil matters. According to section 3(2) of the Courts (Land Disputes Settlements) Act of 2002, land related disputes may be determined by land courts, which exist in different levels, namely Village Land Council, Ward Tribunal, District Land and Housing Tribunal, the High Court (Land Division) and the Court of Appeal. These courts were noted to be important in expediting land conflict resolution. It was noted that for every ward there was a Ward Tribunal with pecuniary jurisdiction of TZS 3 million. By December 2017, there were 53 operational District Land and Housing Tribunals (DLHTs) in Tanzania. DLHTs handle appeals from Ward Tribunals and matters of pecuniary value of more than TZS 3 million but not more than TZS 300 million. The geographical jurisdiction of each DLHT is stated in its establishment instrument. The High Court (Land Division) handles appeals from DLHT and cases with pecuniary value of more than TZS 300 million. The Court of Appeal handles appeals from the High Court (Land Division).

Despite the fact that policies and laws explicitly recognise and support regularisation of informal settlements, review of laws and feedback from the respondents show that some laws inhibit title application and uptake. For instance, it was observed that some property owners did not apply for titles because of their inability to pay statutory fees and charges incidental to title application. The Land Act stipulates some fees and charges a property owner must pay when applying for a title. Furthermore, the Act requires that all land owners with granted land rights to pay land rent annually but it is silent on those who own land without titles. It has also been reported that some property owners were not willing to use their titles as collateral for loans for fear of foreclosure. Legalising foreclosure has made many lenders to apply it more often than not instead of using less harsh means of loan recovery in the event of default. It was also noted that planning and surveying costs were very high mainly because conventional surveying and mapping techniques were still being used. Addressing most of the problems highlighted above, would require a review of pertinent laws.

4.4.2. Social constraints

Regularisation projects are participatory as they entail people meeting and agreeing on matters of common interest such as earmarking areas for infrastructure and public uses. It is common for property owners amongst members of the community to voluntarily give away free of charge portions of their land for infrastructure and other public uses. In some cases, regularisation projects are entirely community based. The entire exercise is organised and financed by members of the community in the manner agreed. In such projects, the role of the government is minimal and normally advisory. Community buy-in is therefore important for any regularisation project to succeed. Out of the five projects covered, Makongo Juu was community based. KAUMAMA, a committee formed by the community, was responsible for overseeing regularisation activities.

It is clear from this study that social constraints played a role in the low title application rate and uptake. For instance, although women were noted to be increasingly getting actively involved in income-generating activities and providing for their families, men still dominated land ownership and decision making in most of the households. Women accounted for only 34.8% of the respondents who owned land. It was also noted that customs and traditions played an important role in discouraging the use of property as collateral. Some people strongly believed that borrowing from banks was shameful. There was also a widespread belief that land was one the most valuable family assets that should not be tempered with in anyway. For instance, 33.3% of the respondents who did not have titles indicated that they did not want them because it was against their norms and tradition to use family landed property for collateral. 60.8% of the respondents who had titles but did not use them for borrowing considered borrowing from banks to be a shameful act in the society. 5.3% of the respondents were not able to access bank loans due to failure to secure spouse consent, which is mandatory for borrowers using matrimonial properties.

The nature and level of education was also noted to be one of the factors affecting title application and uptake. Many property owners did not have basic business and entrepreneurship skills and had generally low financial literacy. Only 16.1% of the respondents possessed basic training on entrepreneurship. Due to limited education and awareness, some property owners believed that titles were largely meant to benefit the government. They believed that a title was nothing but a means of government revenue collection. It was also observed that some property owners were overly afraid of using their titles as collateral for loans. Many of them cited fear of foreclosure as one of the reasons for not borrowing from banks. The observed social constraints played a significant role in slowing down title application and uptake. To address the above-cited challenges, education and awareness campaigns on financial literacy, entrepreneurship, gender equality and land ownership are necessary.

4.4.3. Economic constraints

Tanzania has a GDP of US $ 49.2 billion, GDP per capita of US $ 979 and an average annual GDP growth rate of about 7%. With an estimated population of 50 million people, population growth rate of 2.7% and urbanisation rate of about 3%, pressure on resources is still high, leaving many people with limited means of livelihood. 62.4% of the respondents amongst property owners in regularised settlements fell under the monthly income category of below TZS 100,000. 25% of the respondents indicated willingness to borrow but cited their low monthly income, high lending rates and stringent lending terms and conditions as barriers to borrowing, especially from formal lending institutions. Out of the 25% respondents who had not borrowed money from formal lending institutions but were willing to do so, 66.7% of them cited low monthly income, 22.2% cited high lending rates and 11.1% cited difficult terms and conditions as the main barriers to borrowing from such institutions. As a result of this, many low income earners reverted to informal lending institutions.

Exposure to taxes was one of the deterring factors for some property owners to apply for land titles. It was apparent that some people enjoyed informality because it helped them to avoid some forms of taxes. For instance, a person who owned land without a land title did not have to pay land rent. It was further noted that when owners of untitled properties sold their properties did not have to pay transfer registration fee, stamp duty, application fee, and capital gain tax. Instead they had to pay some small amount of money to the respective local government office. Besides, by not applying for a land title, property owners avoided all payments associated with the issuance of a land title including premium, certificate preparation fee, registration fee, stamp duty, survey fee, and deed plan fee. These initial costs were also cited by both officials interviewed and respondents amongst property owners as one of the main reasons for the low response in land title application.

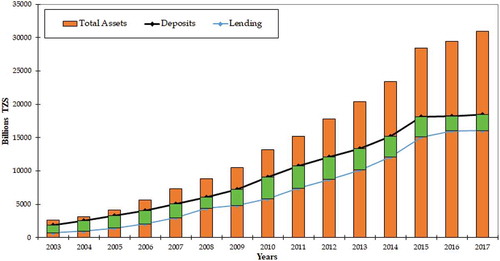

From the interviews and literature, it was clear that one of the reasons for low land title application rate and uptake was low financial literacy and inclusion. However, recent initiatives by the government to deal with the problem are showing some positive results. A study carried out by FinScope (Citation2017) shows that financial inclusion in Tanzania by July 2017 had reached 65%. Even bank borrowing using landed property as collateral was noted to be generally increasing. This may also have been contributed by steady growth of the banking sector and stable lending rates pattern over the recent years. As shown in , over the past two decades, Tanzania has recorded steady growth of the banking in terms of the number of banking institutions as well as the assets. By September 2017, the value of the total assets of the banking sector was about TZS 30.97 trillion. By June 2017, there were 40 commercial banks, 3 development financial institutions, 11 community banks and 5 microfinance banks operating in Tanzania (BOT Citation2017).

shows that over the past two decades the sector has grown markedly, from total assets valued at TZS 2.60 trillion in 2003 to TZS 30.97 trillion in September 2017. The trend also shows that the increase in deposits and lending has paralleled the growth of the sector. Average lending-deposit ratio over the period between 2003 and 2017 is 64.9%. However, high lending rates were cited as one of the deterrents for bank borrowing. It was also noted that some people shunned conventional bank borrowing not because they did not have land titles but rather due to high lending rates and stringent lending conditions.

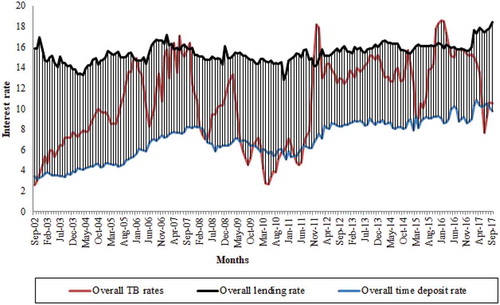

As shown in , between September 2002 and September 2017, overall lending rates averaged at 15.4%. The rate peaked at 18.5% in September 2017 and troughed at 12.8% in November 2010. Lending rates have generally mimicked deposit rates and have been consistently high, maintaining an average spread of 8.5% for the period. It is thus clear that the level of fixed deposit rates also explains the high lending rates. Another reason commonly cited for high lending rates is the overall high treasury bills rate, which averaged 10.8% for the same period. However, as seen in , treasury bills rates pattern does not show a clear causal relationship with both lending and deposit rates.

4.4.4. Political support

Regularisation of informal settlements was noted to be an important political agenda. For instance, the 2015 election manifesto of the ruling political party in Tanzania namely Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) indicated that 2,000,000 land titles would be issued within the period of five years from 2015. The manifesto further states that a special fund for funding district councils and urban LGAs to undertake different regularisation activities would be established. Political support for regularisation of unplanned settlements was also seen from the President’s office. MKURABITA, which undertakes regularisation projects, operates under the President’s office. Having regularisation aspects explicitly stated in the ruling party manifesto coupled with placing MKURABITA under the President’s office, signifies strong political will. This resulted into a strong political support for regularisation activities by both political and government leaders at both central and local government levels. Political buy-in of regularisation activities was also noted from opposition parties. For instance, although regularisation activities at Kimara, Makongo Juu and Idundilanga took place in the wards and sub-wards which were under the political leadership of opposition parties, there was still strong support from those leaders.

From the interviews with project officers, it was noted that there was high support from political leaders because they were involved from the early stages of the regularisation programmes. For instance, at Kimara, awareness campaigns carried out by the regularisation team entailed meetings with Dar es Salaam Regional Secretariat, Ubungo Municipality Full Council and all leaders of the respective sub-wards. Political leaders including ministers were actively involved in each of the five projects covered in this study. They visited all project areas and held public rallies urging people to participate in regularisation activities so that they could get land titles and use them to improve their livelihoods.

4.4.5. Institutional theory reflections

The noted steps being taken in Tanzania to improve the institutional environment, especially in the policy, legal and political areas are in line with various new institutional economics (NIE) theories. Property rights theory and transaction costs theory are two of the notable NIE theories that best explain the imperativeness of having, among others, policies, laws and systems that provide clarity of property rights and ultimately reduction of transaction costs (North Citation1994; Kusiluka Citation2012). Considering the multiplicity and complexity of interests associated with landed property, it is important to have in place a system that clearly defines property rights to ensure that land is effectively utilised for capital and income generation. Most of the initiatives taken in Tanzania, such as enactment of property rights-enhancing policies and laws, mainstreaming property formalisation activities in the government and political machinery, simplifying land title issuance process, are meant to enhance security of tenure, increase property value and saleability and enable land owners to use their land to access credit from formal financial institutions. More reforms are required to deal with deep-rooted inefficient institutions.

Informal institutions such as norms, taboos, customs, values, traditions and social code of conduct are noted to be equally effective in constraining human behaviour (Kusiluka Citation2012; Williamson Citation2009). For instance, the informal settlements neighbourhoods covered in this study have well-established social networks forged in the course of interactions through social gatherings, religious groups and many other kinds of informal interactions. Such social institutions play an important role in safeguarding, among others, property rights. This system has been useful in different ways including authenticating property ownership when properties change hands and settling land disputes. Reliance on this informal system was noted to be one of the reasons for some property owners interviewed not placing importance on land titles. However, it is also evident in this study that some of the cited informal institutions act as a barrier to using land in accessing capital due to unwillingness of some land owners to use their land as collateral for credit.

5. Conclusion

The paper has identified various factors affecting land titles application and uptake. Whereas some factors were noted to attract property owners to have land titles others discouraged them. Property owners considered titles to be important in enhancing security of tenure, accessing credit, conflict resolution, court bail and recognition by the government. Low land title application was mainly caused by a complicated application procedure, inability to pay statutory fees and charges, and limited knowledge of land title benefits and application procedure. Title uptake especially in accessing credit was hindered by difficult lending terms and conditions, high interest rates, fear of foreclosure, not having a business with regular income flow to be able to service the loan, negative borrowing perceptions, low financial literacy and lack of entrepreneurship skills.

The main factors identified can be grouped into four categories namely legal, economic, political and social. These factors define the broad institutional environment under which decisions are made. Social constraints such as beliefs, traditions and norms, in most of the cases deter property owners from applying and using land titles. Economic constraints such as low income, high interest rates, high professional services costs, land related taxes, fees and charges coupled with low financial literacy and entrepreneurship skills, play a significant role in impeding title application and uptake. Policy and legal institutional instruments are to a large extent, supportive of title application and uptake. However, some laws act as a barrier to title application as they impose fees and charges both of which are deterrents to title application and uptake. The use of contemporary technologies, especially in land surveying, mapping and registration is also hampered by some old laws and regulations. The political environment, on the other hand, was noted to be highly supportive of regularisation activities. These findings underscore the imperativeness of undertaking a comprehensive institutional environment analysis while designing and executing any regularisation project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Moses M. Kusiluka

Moses M. Kusiluka is a part-time lecturer in the Department of Land Management and Valuation at Ardhi University. He previously served as Head of the Department of Real Estate Finance and Investment at Ardhi University, Commissioner for Lands for Tanzania and Deputy Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development

Dorice M. Chiwambo

Dorice M. Chiwambo is a postgraduate student majoring in Public Policy Analysis and Programme Management at the Institute of Human Settlement Studies, Ardhi University

References

- Ahiakpor J. 2008. Mystifying the concept of capital: Hernando de Soto’s misdiagnosis of the hindrance to economic development in the Third World. Indept Rev. 13(1): 57–79.

- Ayalew D, Collin M, Deininger K, Dercon S, Sandefur J, Zeitlin A. 2013. Are poor slum dwellers willing to pay for formal land title? Evidence from Dar es Salaam. Washington DC: World Bank.

- Becchetti L, Kobeissi N. 2009. Role of governance and institutional environment in affecting cross border M&As, alliances and project financing: evidence from emerging markets. CEIS Working Paper. 7(156):1–30.

- BOT. 2017. Economic bulletin for the quarter ending December 2017, Tanzania, Bank of Tanzania. Report. No. XLIX. p. 4.

- Byamugisha F. 2016. Securing land tenure and easing access to land. Background Paper for African Transformation Report 2016: Transforming Africa’s Agriculture. p. 1–34.

- Chiwambo D 2017. Analysis of the factors affecting acceptability of residential licences in Tanzania. The case of Ubungo Municipality [master’s dissertation]. Tanzania: Ardhi University.

- Dam K 2006. Land, law and economic development. Working Paper prepared for book length study of the rule of law in economic development. 1–34.

- D’Arcy E, Keogh G. 1999. The property market and urban competitiveness: A review. Urban Stud. 36(5–6):917–928.

- De Soto H. 2000. The mystery of capital: why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else. New York (NY): Basic Books.

- Domeher D, Abdulai R. 2012. Access to credit in the developing world: does land registration matter? Third World Q. 33:1.

- Durand-Lasserve A, Payne G. 2006. Evaluating impacts of urban land titling: results and implications: preliminary findings. London. Draft Report Prepared for Geoffrey Payne and Associates

- Ellis K, Lemma A, Rud J. 2010. Investigating the impact of access to financial services on household investment. UK: Oversee Development Institute.

- Finmark. 2011. Housing finance in Africa: a review of some Africa’s housing finance markets. South Africa: The Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa.

- FinScope. 2017. Insights that drive innovation. Tanzania: Finscope.

- Haas A, Jones P. 2017. The importance of property rights for successful urbanization in developing countries. Int Growth Centre: Policy Brief. 43609:1–8.

- Home R, Lim H. 2004. Demystifying the mystery of capital: land tenure and poverty in Africa and the Caribbean. London: Glasshouse Press.

- Krishnan K, Panchapagesan V, Venkataraman M. 2016. Distortions in land markets and their implications on credit generation in India. Working Paper 005: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research. 1–27.

- Kusiluka MM. 2012. Agency conflicts in real estate investment in Sub-Saharan Africa: exploration of selected investors in Tanzania and the effectiveness of institutional remedies. Cologne: Immobilien Manager Verlag.

- Kyessi A, Furaha G. 2010. Access to housing finance by the urban poor: the case of WAT-SACCOS in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Int J Housing Market and Analysis. 2(3):182–202.

- Manders J. 2004. Sequencing property rights in the context of development: a critique of the writings of Hernando de Soto. Cornell Int Law J. 37(1):178–198.

- MLHHSD. 2018. Budget speech for MLHHSD for the year 2018/2019. Speech presented to the Parliament on May, 2018 in Dodoma.

- MLHHSD. 2017. Regularization of informal settlements in Tanzania in 2016/2017. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development Report.

- NBS. 2016. National economic situation in 2016. Dar es Salaam: National Bureau of Statistics.

- North DC. 1994. Economic performance through time. Am Econ Rev. 84(1):359–368.

- Nyamu-Musembi C. 2007. De Soto and land relations in rural Africa: breathing life into dead theories about property rights: De Soto and land relations in rural Africa. IDS Working Paper. 272:1–27.

- Okyere S, Aramburu K, Kita M, Nazire H. 2016. COFOPRI’s land regularisation program in Saul Cantoral informal settlements: process, results and the way forward. CUS. 4:53–68.

- Samuelson R. 2001. The spirit of capitalism. Foreign Aff. 80(1):205–211.

- Sanga SA. 2017. The value of formal titles to land in residential property transactions: evidence from Kinondoni Municipality in Tanzania. Int J of Housing Market and Analysis. doi:10.1108/IJHMA-04-2017-0033

- Sheuya S, Burra M. 2016. Tenure security, land titles and access to formal finance in upgraded informal settlements: the case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. CUS. 4:440–460.

- Sjaastad E, Cousins B. 2008. Formalization of land rights in the South: an overview. Land Use Policy. 26:1–9.

- Trebilcock M, Prado M. 2011. What makes poor countries poor? Institutional determinants of development. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- UN-Habitat. 2012. Zambia: urban housing sector profile. Nairobi: UN-Habitat Publishing.

- USAID. 2012. Land titling and credit access: understanding the reality. Property Rights Resour Governance Briefing Paper. 15:1–10.

- Williamson CR. 2009. Informal institutions rule: institutional arrangements and economic performance. Public Choice. 139:371–387.