ABSTRACT

Urban infrastructure investment needs in the developing world are immense, particularly when the additional costs associated with lower carbon, more climate-resilient options are considered. These cannot possibly be financed from fiscal sources and ODA flows alone; private financing will need to be accessed. Focusing on the ability of city governments and subnational urban utilities to mobilize private finance, this paper makes two core arguments. First, private investment in municipal infrastructure requires robust institutional, fiscal and regulatory systems that are often absent in developing countries. Establishing such systems often requires policy and institutional reform, much of which lies beyond the competence and control of city governments themselves. Second, while the marginal investment needs related to climate mitigation and adaptation complicate and aggravate the picture, they do not alter the fundamental requirements of private investors. Put simply, municipalities and utilities will need to satisfy the requirements of regular private finance before they can attract green private finance. This paper looks across the main avenues for city governments to mobilize private finance – municipal borrowing, public–private partnerships, and land value capture instruments – and identifies four broad factors that determine the potential size and scope of city leveraging activity. It then offers a new framework to understand where the most pressing constraints to private investment readiness lie and proposes priority measures that local and national governments, together with development partners and other stakeholders, can take to address them.

1. Introduction

Two and a half billion people will be added to the world’s urban population by 2050 (UN DESA Citation2018). Driven by sustained city growth and the need to adapt to and mitigate climate change, global urban infrastructure financing needs are massive. The most comprehensive assessment of these provides a conservative estimate of over USD 4.1–4.5 trillion per annum for ‘business as usual’ requirements (CCFLA Citation2015). Mitigation costs add another USD 0.4–1.0 trillion each year (9–24 per cent), and adaptation costs add a further USD 120 billion each year (3 per cent) – although this could be much greater if the average global temperature increases by more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels. While there is no reliable disaggregation of this requirement across developed and developing countries, most is likely to be concentrated in the latter where historical infrastructure deficits are most pronounced and the world’s urban transition is still underway.

Funding and financing this infrastructure is a massive challenge, and there is accordingly a growing body of literature and practice devoted to financing climate-compatible infrastructure in cities. In this article, we focus specifically on the role of city governments and utilities in raising and steering private finance.

The expenditure assignments of city and municipal governments vary widely across developing countries. In most cases such governments, together with state-owned utilities, have substantial responsibilities for funding, building and operating core municipal infrastructure in areas such as roads, drainage, solid waste management, sanitation and water supply.Footnote1 Yet, it is clear that these infrastructure investment needs cannot be satisfied from existing city budgets alone. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, many city governments have per capita budgets of less than USD 20 per annum, much of which is committed to ongoing operating expenses such as salaries rather than available for capital expenditure (Cartwright et al. Citation2018). Domestic public budgets will be insufficient even if blended with ODA flows, which totaled around USD 146.6 billion in 2017 (OECD Citation2018) – far short of global urban infrastructure investment needs. A substantial scale-up in mobilization of domestic financial resources and extensive private sector investment will be required to meet this shortfall. A step-change of several orders of magnitude above current levels is necessary.

Too often, work on this topic understands constraints to private financing primarily or exclusively in terms of weak ‘project bankability’. We argue that this perspective does not recognize the underlying reasons that city governments and utilities in developing countries are unable to leverage private investment for urban (climate) infrastructure. This article responds to the gap in the literature by making two core arguments.

First, private investment in municipal infrastructure rests on robust institutional, fiscal and regulatory systems which are often absent in developing countries. Accountable, transparent and efficient frameworks are a precondition for attracting private investment, regardless of financing modality (e.g. municipal borrowing, public–private partnerships (PPPs)). Establishing such systems often requires policy and institutional reform, much of which lies beyond the competence and control of city governments themselves. Both the immediate and longer term ability of city governments and utilities to leverage and attract private finance are constrained by the appetite for and substantive approach to reform on these fronts by national government agencies.

Second, the climate imperative does not change these fundamental realities nor does it greatly alter the requirements of private investors. Certainly, the emergence of the new technologies, business models and greater capital needs related to climate mitigation and adaptation complicates and aggravates the picture. Ultimately, however, the same prosaic agenda needs to be tackled to mobilize finance at scale for either conventional or climate-oriented urban infrastructure.

In the next section, we explain our methodology. In Section 3, we outline the ways that municipalities and utilities can mobilize private finance for urban infrastructure investment and consider the extent to which these instruments are deployed. In Section 4, we consider the preconditions for using these different financing instruments for any urban infrastructure projects. In Section 5, we explore whether these preconditions might be different in light of the urgent need for ambitious action on climate change. We offer concluding thoughts and recommendations in Section 6.

2. Methods

The article draws on our individual and collective experiences with urban finance across the global South over 30 years.

The World Bank is the largest multilateral development bank active in the urban space, with a global portfolio of support to cities and local governments. The Bank’s urban portfolio, excluding investment in sectoral systems such as mass transit and water supply, stands at about $25bn and commits approximately $5 billion of new funding annually. The World Bank Group is increasingly involved in enabling cities and sub-national entities to directly access finance for urban infrastructure projects. The following are some of its relevant activities, particularly those with a climate orientation:

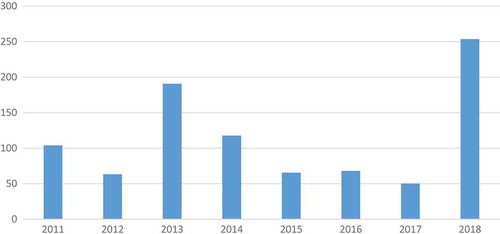

Lending directly to cities, utilities and other sub-national entities without sovereign guarantees (see );

Offering guarantees against political risk or the non-honouring of sovereign financing obligations to de-risk urban infrastructure projects;

Providing technical assistance to identify and implement different financing modalities to leverage private capital;

Providing technical assistance to city governments to strengthen their creditworthiness and, in some cases, follow-up support to facilitate access to credit and generate PPPs;

Providing technical assistance to national and city governments to analyse regulatory constraints to private financing modalities and introduce appropriate reforms;

Providing technical assistance to develop a pipeline of bankable capital investments, mainstreaming climate resilience considerations into all prospective projects; and

Participating in global partnerships to propel progress in this area, such as the City Climate Finance Leadership Alliance.

Figure 1. Municipal commitments by the International Finance Corporation by financial year, USD million (data source: IFC)).

Within the Bank, we have led multiple analytic and policy advisory efforts in the urban finance space, the design, delivery and evaluation of both municipal finance strategies and large infrastructure projects, and supported partners in comparable efforts. Our deep and long-term exposure to the perspectives and work of local governments and prospective investors has enabled us to develop a rich understanding of their objectives, responsibilities and capabilities, as well as the critical constraints that they face. This article offers insights from this experience, bringing the perspective of a large-scale, global financier into the academic literature. It draws on data both held within the World Bank and available from secondary and published sources.

3. Options to mobilize private finance

Financing and funding are two different things. Finance refers to the raising of money for investment; funding refers to the payment for the investment, including the financing cost, over the long term. Finance thus does not obviate the need for funding. In fact, because finance comes at a price (interest or return on equity), it aggravates the funding need. If municipal governments and utilities are to mobilize finance, they need to demonstrate the ability and commitment to pay for that finance with funding which, in a municipal (or utility) environment, comprises either local (‘own source’) revenues (taxes and service charges) or fiscal transfers (including aid grants). The greater the volume of private finance, the greater the need for funding. In order to finance more, one needs to fund better. This points to the importance of ‘fixing the fiscal fundamentals’ of municipalities and utilities as a core part of the urban – and climate – finance agenda.

Once a robust funding base is established, state agencies can deploy a range of mechanisms to crowd in private investment. The avenues through which private finance may be leveraged into urban infrastructure investment may be divided into three basic categories: debt financing, contracting and land value capture (PPPs) instruments.

Debt financing encompasses instruments through which funds are borrowed by a government agency. Repayments and returns are secured by the general balance-sheet of the borrowing entity (general obligation borrowing) or by particular revenue flows which are dedicated to this purpose. Contracting or PPP arrangements are those in which either (a) private funds are secured as equity contributions and/or debt for infrastructure projects and the returns are secured through the future revenue streams directly attached to those projects, or (b) where funds are indirectly borrowed for projects and repaid from the general revenues of the city government/utility through dedicated fee arrangements.

LVC instruments describe mechanisms whereby governments partially capture the appreciation in the value of urban land, which may be catalysed in part by investment in infrastructure adjacent to or otherwise linked to that site. LVC instruments range from relatively straightforward mechanisms, such as the imposition of impact fees or development charges on private developers, to much more complex approaches, such as Tax Increment Financing which leverages capital for public infrastructure investment on the basis of future increases in property tax revenues.

For decades, even centuries, cities in developed countries have received significant inflows of private finance into urban infrastructure through all these channels. The municipal bond market in the United States, which originated in the early 1800s, grew to USD 2.8 trillion by 2010 (Farvacque-Vitkovic and Kopanyi Citation2014, Chapter 7) and is around USD 3.9 trillion today. PPPs have long been used to finance urban infrastructure projects, including parts of such iconic projects as the London Underground and Sydney Harbor Bridge. Land-based financing is perhaps the oldest of all: property taxes were used in Babylon, China, Egypt and Persia. Leveraged land value capture approaches are newer and, have been utilized extensively in larger and more capacitated cities such as New York, Washington DC, London, and Hong Kong (Suzuki et al., Citation2015). In the United States alone, Tax Increment Finance bonds issued totaled over USD 39 billion between 2000 and 2015 (Layton Citation2016).

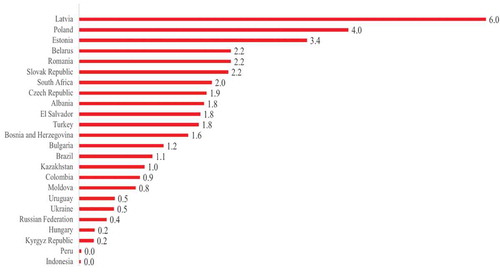

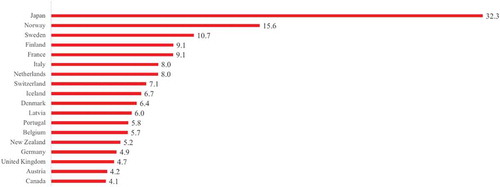

Such activity is much more limited across both middle and low-income countries in the developing world. The difference is clearly illustrated in and , which show total municipal borrowing liabilities accumulated in a spectrum of countries from the developed and developing world. Note that the scales are different in the two figures.

Figure 2. Stock position of municipal debt liabilities (per cent GDP) of various developing countries, 2016 (data source: IMF 2018).

In terms of debt financing, there are really only a few countries across the global South where cities can effectively access credit for infrastructure investment. Foremost among these are the emerging markets of East/Central Europe, and particularly those at higher income levels. In sub-Saharan Africa, the only country in which cities can effectively access credit markets is South Africa; in East Asia, outside of China, the Philippines is similarly an outlier; and in South Asia, it is only in India where municipalities can effectively borrow – and there borrowing volumes are extremely low (World Bank Citation2011). Municipal borrowing in Latin America is also very limited, one exception being Colombia where municipalities can borrow from a government-owned municipal development bank, FINDETER. In China, city borrowing was legally prohibited until 2013, although significant borrowing took place off-balance sheet. Municipal borrowing is also highly constrained in the Middle East and North Africa.

PPP activity in developing countries at the subnational level is estimated at around USD 10 billion per annum, less than a fifth of national PPP volumes (World Bank Citation2016).

Many public authorities in developing countries use property taxes and the direct sale or leasing of land (often after appropriation and rezoning, as in China and Ethiopia) to raise finance. However, leveraged land value capture transactions are generally scarce, and only a few cities have experimented at a significant scale with these. Latin American cities are among the leaders. For example, Sao Paulo in Brazil has generated over USD 800 million for public works between 2004 and 2009 through the auctioning of development density bonuses. Quito in Ecuador has sold transferable development rights, while Bogota has raised over a billion dollars through betterment levies between 1993 and 2013 (Smolka Citation2013). Many African cities are experimenting with in-kind contributions, development charges and betterment levies, but these are typically imposed in an ad hoc manner rather than as a systematic financing strategy (Berrisford et al. Citation2018).

In short, few towns and cities across the global South are currently deploying the diverse bundle of instruments necessary to systematically leverage private finance at scale. This is despite the fact that it is these urban areas that need to attract investment most urgently, both to redress historical underinvestment and to keep pace with growing urban populations and economies. The next section seeks to explain this phenomenon.

4. Constraints on mobilizing private finance

The factors constraining the flow of private finance into urban infrastructure in developing countries are powerful and deep. Across all types of financing avenue, four generic factors determine the potential size and scope of city leveraging activity (World Bank Citation2011):

The intergovernmental fiscal and institutional framework. The ability of municipalities to attract private finance will depend, in part, on the revenue sources to which they have access to cover financing costs. This includes both revenues which are assigned to local governments (‘own source revenues’) and fiscal transfers instituted to address fiscal gaps. Moreover, the scope to use LVC instruments depends substantially on the system of land property rights, including the quality of the land and property registry, valuation systems and ease of transactions. Much of this is typically established at the national or state level, rather than by city government.

The quality of city financial data, accounts and management systems. In order to make sensible credit and investment decisions investors need to be able to understand municipal accounts and balance sheets and have confidence in the overall quality of financial management systems, not least those pertaining to the enforcement of revenue collection. Where project-related revenue streams are used to secure investment obligations (e.g. in revenue-backed bonds or certain types of PPP transaction), the feasibility and quality of the projects in which private funds will be invested is also directly relevant (this is often referred to as ‘project bankability’).

The depth and character of the financial sector. The size and sophistication of domestic capital markets will influence the quantum of capital available for investment, the returns required, risk appetite and the scope to deploy more complex financing arrangements. The domestic financial sector is, in turn, affected by the surrounding macro-economic conditions that may influence an expansion or contraction of such credit. International financing sources could also be taken into consideration, but most governments in developing countries do not allow local governments to take on private foreign currency liabilities (including important emerging economies such as South Africa, Brazil and Vietnam). These policies are informed by historical experiences in which liabilities denominated in foreign currencies have sometimes created severe financial difficulties for sub-nationals when exchange rates plummeted.

The regulatory framework pertaining to municipal borrowing, PPP and LVC transactions. This comprises the ‘rules of the game’, including matters such as whether cities can borrow and how much, what currencies they can borrow in, the type of collateral that they may pledge to secure borrowing, events in cases of default; their rights to enter into long-term PPP contracts and to determine tariff levels; whether cities can sell and trade development rights; the rules governing rights exchanges; and so on.

In general terms, factors 1 and 2 determine the perceived attractiveness of an investment or borrower, and hence form the demand side of the financing equation. Factor 3 determines the scope to provide finance, and hence the supply side. The quality of the regulatory framework, factor 4, intermediates demand and supply, shaping the incentives and behaviours of both investors and municipal governments. If conditions across all four areas are not conducive to private investment, investment will not take place. For instance, it does not follow that cities which have good credit may necessarily be able to borrow. Actual borrowing potential relies on a sufficiently well-developed financial sector and a regulatory framework that clearly articulates the legal rights of municipalities to borrow.

Analysis undertaken in countries such as India and Vietnam (World Bank, Citation2011; Campanaro et al.Citation2016), and the experience of countries such as South Africa where nominal municipal borrowing expanded significantly once regulatory and other issues were addressed in the early-2000s, show that the binding constraints tend to lie in the demand (or ‘creditworthiness’) and regulatory areas. This analysis underscores that city governments cannot singlehandedly overcome the constraints to mobilizing private finance. The design and nature of national frameworks and systems also dictates municipal or utility ‘readiness’ to secure private investment for climate-compatible urban infrastructure.

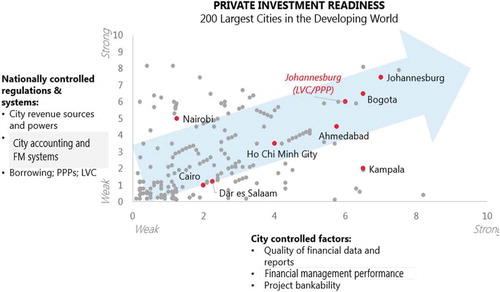

In this context, cities in developing countries can be placed on a spectrum comprising two dimensions. One pertains to matters largely under the control of national governments such as the revenue sources that cities are permitted to collect, the borrowing powers of subnational entities, the quality of land and property systems, accounting standards and so on. The other pertains to matters which are largely under the control of city governments such as the quality of their financial data, financial management systems, balance sheets and so on. This spectrum and a stylized plotting of a few city positions on it are outlined in . It should be noted that this spectrum, and the city positions, can be disaggregated according to different transactional types. For example, Johannesburg and Bogota may have clear borrowing powers and capacities, but the regulatory regime governing their ability to enter into PPP or LVC transactions may be more constrained, in which case they would fall further down the spectrum with respect to these leveraging avenues.

Figure 3. Stock position of municipal debt liabilities (per cent GDP) of various mature markets, 2016 (data source: IMF 2018).

Figure 4. Lending to municipalities in South Africa (data source: National Treasury of the Republic of South Africa. Citation2016).

Figure 5. Stylized illustration of the ‘private investment readiness’ of cities, highlighting the need for robust frameworks and systems at both the national and municipal level. The named cities are only indicatively positionedFootnote2.

A systematic global analysis of cities across developing countries in terms of both these dimensions has not, to the best knowledge of the authors, yet been undertaken. However, it is broadly evident – and substantiated by credit-rating data – that most cities in the developing world would tend to cluster towards the lower left end of the spectrum. These towns and cities face constraints at both the (national (policy/systemic) and local levels. Such cities may be subject to a national regime in which, say, borrowing and PPP transactions are not permitted or are highly constrained. Simultaneously, the quality of their accounting and financial management systems may be poor and their capacity to develop bankable projects weak. Many African and South and East Asian cities fall into this part of the spectrum. To unlock access to private finance in these contexts, there is a need to reform national institutions and frameworks, as well as to improve the quality of city financial data, accounts and management systems.

At the other (highest) end of the spectrum are cities (and utilities) with an enabling national and local environment. Such cities enjoy an intergovernmental fiscal system that provides them with strong revenue powers, permits municipal borrowing and LVC transactions, authorizes cities to pledge revenues and mandates good practice municipal accounting standards. These cities also have robust financial management practices and the capacity to prepare (in house or on an outsourced basis) bankable projects.

There are a handful of developing country cities at the top end of the spectrum. An indicator of this might be the ability to issue a municipal bond, as this demonstrates that a city has a sufficiently robust policy, fiscal, institutional and credit environment at both the national and local level. As of 2018, only 32 cities across 12 developing countries (Argentina, Bolivia, China, Colombia, India, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Russia, South Africa, Uruguay, Vietnam) have issued municipal bonds (see ). At the time of issuance, these cities would all have fallen into the top right quadrant of .

Table 1. The breakdown of large and investment-grade cities by region. (Data source: World Bank City Creditworthiness Database).

In some cases, private investment readiness will be constrained primarily at the local level. In , this would explain cities in the top left quadrant. Many smaller or lower income or poorly managed cities will fall into this category, particularly those in the 23 countries listed in . These countries demonstrably have enabling national environments since some cities have achieved an investment-grade credit rating; however, municipalities with weaker capacities, a smaller tax base or weak financial management systems may not have sufficient revenues to anchor access to credit or may present unacceptably high credit risks, or may not possess the skillsets necessary to wield complex financing instruments such as LVC. Note that, this characterization should be treated with some caution as, in federal systems, ‘nationally determined’ conditions (such as municipal borrowing frameworks) may in effect be determined at the state level, and conditions between states may vary considerably. India is a good example.

In other cases, private investment readiness will be constrained at the national level (represented by cities in the bottom right quadrant of ). This would include cities such as Kampala, which has recently received an investment-grade rating but is prohibited by domestic law from borrowing at a level which would make any transaction attractive to investors. In a rather different country, Vietnam, city (provincial) borrowing has been limited and sporadic. Here, national support is required both to improve the sub-national borrowing regulatory environment (which is not conducive to sustained borrowing at scale) and to improve the quality of sub-national financial management.

The basic challenge of leveraging increased private sector finance into urban infrastructure – climate-oriented or not – involves shifting cities to the top right quadrant of the spectrum. Although the specific reforms and activities required will vary across particular countries and cities, this broadly requires two broad areas of work:

National authorities (or, in some federal countries, state authorities) may need to reform policies and rules pertaining to the intergovernmental fiscal system, city accounting and financial management systems, and regulatory regimes governing municipal borrowing, PPPs and LVC. These reforms often raise fundamental political and policy issues (such as the degree of fiscal autonomy of city governments or the tariff-setting/powers of national ministries) that national decision-makers may be reluctant to address. Even if there is the political will to address them, reform generally takes a continuous effort over a lengthy period.

City authorities may need to improve the quality of their financial data, financial management practices, strengthen their balance-sheets and improve the bankability of their projects. This requires substantial fiscal discipline and raises similarly difficult political and policy issues at the local level. Many city authorities may be reluctant to limit public spending if the political benefits will be largely enjoyed by subsequent city administrations.

In short, improving the ability of city governments and utilities to attract and absorb private investment will typically demand sustained political commitment, comprehensive reform of national (or state) policies and strengthening of systems at both the national and local levels.

An additional area of intervention is possible to mobilize private finance in the near-term in imperfect policy and institutional environments. Investment ‘de-risking’ requires that the risks to private investors generated by suboptimal regulatory regimes and below investment-grade municipalities are transferred to other entities, typically national governments, MDBs or donor agencies. This may be done through various forms of guarantee or credit enhancement. Notable examples include the Local Government Unit Guarantee Corporation in the Philippines, the Development Assistance Committee facility of USAID, and the World Bank Group’s guarantee products.

Interventions of this type need to be treated with caution. Because they inherently create moral hazard (Noel Citation2000), they tend to generate perverse incentives and fiscal risks. Over time, they can threaten the sustainability of the very system they are trying to expand. However, if appropriately targeted and designed, credit enhancement facilities may usefully accelerate private investment while avoiding egregious systemic distortion. For example, it is common among those developing countries which permit city borrowing to prohibit those cities from incurring forex liabilities as they cannot easily hedge currency risk. In such circumstances, providing a forex-risk credit enhancement to transactions in which cities borrow from foreign investors could address the regulatory hurdle and mitigate city currency risks without generating severe moral hazard impacts.

A long-term, coherent strategy coordinated across different levels of government is essential to improve municipal access to private finance. The next section considers these preconditions in light of the growing threat of climate change.

5. Implications for financing climate action

The need to address climate resilience and mitigation imperatives adds both urgency and magnitude to the financing need for urban infrastructure and services. Accordingly, the challenge of financing climate action has drawn increasing attention in the academic and technical literature. A number of articles and reports have been published on themes such as the financing instruments that are potentially available to leverage private investment in municipal infrastructure, the way in which such instruments can be used to accommodate climate investment needs, and other supportive interventions which may be helpful for cities to attract increased private financing flows. There is a particularly strong focus on electricity generation and urban transport infrastructure, which have the most significant implications for urban emissions. Valuable as such contributions may be, they tend to focus on instruments and approaches which, with some important middle-income country exceptions, are currently feasible only in developed countries (e.g. Merk et al. Citation2012).Footnote3 In other cases, the research fails to recognize that responsibility for funding and financing large urban infrastructure does not fall to city governments, but will – particularly for smaller cities – remain the responsibility of much larger state agencies. Alternatively, the literature calls for a radical change in the priorities and approaches of financiers that seems unlikely (e.g. Brugmann Citation2012).

Climate change does not in itself alter the fundamentals of infrastructure finance. Simply put, before a city can issue a green bond, it must first be able to issue a (regular) bond. The relative insignificance of climate considerations (from the perspective of financiers) is demonstrated by comparing the relative cost of finance for conventional versus sustainable infrastructure. A number of global studies have indicated that the pricing of green bonds is practically identical to the pricing of traditional bonds (GIZ Citation2017). One analysis suggests that the relative desirability of green labelling is offset by the perceived additional risks associated with green financing (OECD Citation2015).

It is difficult to get a clear picture of relative spreads specifically for urban climate infrastructure because the municipal market in developing countries is so limited. To date, to the knowledge of the authors it appears that only three developing country cities have issued ‘green bonds’: Johannesburg, Cape Town and Mexico City. The coupon on the Cape Town green bond was only 35 basis points less than that of a regular bond issued by another South African city (Ekurhuleni) with a similar Moody’s credit rating at roughly the same time. Certainly, there are classes of investor which will be particularly attracted to impact financing of this type; this might help explain why the green bonds for Cape Town and Johannesburg were so oversubscribed (Gorelick Citation2018). However, it does not appear that such investors are likely to be more risk-averse or provide such finance on terms which are significantly discounted relative to conventional investments. Even where the financial case for climate-compatible investments may be attractive, investors continue to be deterred by other barriers such as poor provision of information, transaction costs and capacity deficits (Colenbrander et al. Citation2017).

Similarly, climate change does not inherently change the preconditions for city governments to utilize PPPs or LVC. They might choose to fund more sustainable infrastructure projects in light of the need to reduce emissions or enhance resilience, but they will still need to have their fiscal, institutional and regulatory essentials in place: national legislation authorizing municipalities to use these instruments; effective project preparation capacities; strong contracting capacities; integrated spatial, infrastructure and financing strategies and so on (Ahmad et al. CitationForthcoming). Without these fundamentals in place, private investors will lack confidence irrespective of the environmental sustainability of the project.

In sum, early indications are that cities will not be able to attract private green or climate finance on terms which are very much easier than that for regular finance. And there are a wide range of barriers to mobilizing infrastructure investment of all kinds, particularly in the global South (Granoff et al. Citation2016). Compliance with the non-financial terms of ‘green finance’ may also impose greater implementation challenges and reporting duties on cities than conventional debt finance. For instance, ensuring that a green bond is certified under an appropriate standard and that the proceeds are allocated to sufficiently green projects requires higher degrees of sophistication and capacity. There are therefore incremental costs to the issuer that – to date – have not been compensated for through a lower cost for green capital.

Yet, climate change exacerbates the need to rapidly mobilize private finance for sustainable urban infrastructure while also creating new investment risks that need to be managed (Martimort and Straub Citation2016). Since it may take decades for towns and cities to develop sufficiently robust fiscal underpinnings, a subsidy may be required to facilitate investment in urban climate projects. The argument in favour of such subsidization – by central governments or by donor organizations – derives from the vital global, regional and local public good that low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure provides.

There are many ways to provide such a subsidy to cities in developing countries. A plethora of instruments for both regular and climate-oriented infrastructure investment has been developed and utilized in more sophisticated markets for decades. For instance, there is scope to de-risk climate projects through expanding credit enhancement activities, if facilities are adequately capitalized, appropriately institutionalized and professionally managed (Schmidt Citation2014). Or there is scope to support aggregation of projects and therefore spreading of risk, which many cities are pursuing within and across national borders (Colenbrander et al. Citation2018). The need to reduce or respond to climate-related impacts provides the rationale for underwriting credit risks or improving credit access in an appropriate, non-distortionary manner and financial engineering expertise is widely available globally (with donor organizations often willing to pay).

In the medium to long term, however, the expanded use of ‘city climate finance’ instruments in the global south will only be possible to the extent that the conditions which underpin access to finance more generally emerge. The hard, long, most essential task is to develop the policy, regulatory, fiscal and institutional environments which allow such instruments to be utilized in the many countries where such environments do not yet exist.

6. Conclusion

While climate change has galvanized attention regarding the challenge of financing climate-smart, resilient urban infrastructure – and the importance of attracting private finance to such investment – the reality remains that, across the developing world, municipalities and other urban entities have a long way to go before they will be able to do so at scale.

For city governments to systematically leverage private investment, there is a need to (i) reform the intergovernmental fiscal and institutional framework, including the fiscal transfer system and the own source revenue structure of city governments; (b) strengthen cities’ financial management systems and processes, and the overall quality of city governance; (c) deepen the financial sector, specifically domestic capital markets; and (d) enhance regulatory frameworks pertaining to municipal borrowing, PPP and LVC transactions. These four factors must be addressed whether or not urban infrastructure projects are climate-compatible or otherwise.

Municipalities and urban utilities certainly have work to do to strengthen their financial management practices, improve the quality of their data, increase revenue yields, prepare ‘bankable’ projects and explore ways of generating greater revenue security for private investments. However, towns and cities in the global South cannot overcome the barriers to infrastructure investment alone. Enhancing private investment readiness successfully will require action from multiple actors.

National governments need to strengthen domestic institutions and reform policy and regulatory frameworks relating to subnational financial management and financing activity. Multilateral development banks, bilateral donors, city networks and other agencies can support national and local governments in these efforts with a combination of funding support, technical assistance, capacity building and facilitation of knowledge exchanges. Finally, assuming that suitable conditions are created, private investors will obviously need to expand their business with respect to subnational lending, PPPs and LVC transactions.

Conscious, sustained focus and innovation will be required for towns and cities across the global South to achieve private investment readiness. Even if the prospect of a global temperature increase exceeding 2°C does not change the fundamental preconditions for infrastructure finance, it may provide the necessary motivation for governments to act. Such efforts will ultimately be justified by the social, economic and environmental returns that are potentially available in this vast sector of the infrastructure market.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Takaaki Masaki who researched and generated some of the data and charts and to Sarah Colenbrander for her valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Roland White

Roland White, a South African national, is the World Bank Global Lead: City Management, Governance and Finance. With an international career stretching over 30 years across private, public and multilateral development bank sectors he has led major urban analytic, policy advisory and investment operations in multiple countries across several world regions. He has also led a number of global engagements in the city finance space, including serving as co-lead of the Municipal Finance Policy Group for the Habitat III 20-year “New Urban Agenda” conference held in Quito in 2016.

Sameh Wahba

Sameh Wahba, an Egyptian national, is the Global Director for Urban and Territorial Development, Disaster Risk Management and Resilience at the World Bank’s Social, Rural, Urban and Resilience Global Practice. He oversees strategy formulation and the design and delivery of all lending, technical assistance, policy advisory work and partnerships at the global level, a portfolio of $25bn and a team of 300 staff. He has 25 years experience in urban planning, housing, land and local economic development.

Notes

1. In regions around the world, local government expenditure as a proportion of general government expenditure varies from a low of around 8 per cent in the Middle East and North Africa to a high of around 28 per cent in East Asia and the Pacific. (Based on IMF GFS, 2015. This excludes South Asia as data for only one country in that region were available.)

2. The chart is not based on hard numerical data. The plotting of the named cities represents the judgements of the authors. This spectrum could be further disaggregated according to different transactional types. For example, Johannesburg and Bogota may have clear borrowing powers and capacities, but the regulatory regime governing their ability to enter into PPP or LVC transactions may be more constrained, in which case they would fall further down the spectrum with respect to these leveraging avenues.

3. Yaounde, Cameroon, is a notable exception to this norm (Gorelick Citation2018).

References

- Ahmad E, Dowling D, Chan D, Colenbrander S, Godfrey N. Forthcoming. Scaling up investment for sustainable urban infrastructure: a systematic approach to urban finance reform for national governments. London and Washington DC.: Coalition for Urban Transitions.

- Berrisford S, Cirolia LR, Palmer I. 2018. Land-based financing in sub-Saharan African cities. Environ Urban. 30(1):35–52.

- Brugmann J. 2012. Financing the resilient city. Environ Urban. 24(1):215–232.

- Campanaro A, Dang CD. 2018. Mobilizing finance for local infrastructure development in vietnam: a city infrastructure financing facility. Washington (D.C.): World Bank Group.

- Cartwright A, Palmer I, Taylor A, Pieterse E, Parnell S, Colenbrander S. 2018. Developing prosperous and inclusive cities in Africa – national urban policies to the rescue? Coalition for urban transitions. London and Washington DC.

- CCFLA. 2015. The state of city climate finance 2015. New York: City Climate Finance Leadership Alliance.

- Colenbrander S, Dodman D, Mitlin D. 2018. Using climate finance to advance climate justice: the politics and practice of channeling resources to the local level. Climate Policy. 18(7):902–915.

- Colenbrander S, Sudmant AH, Gouldson A, de Albuquerque I R, McAnulla F, Oliviera de Sousa Y. 2017. The economics of climate mitigation: exploring the relative significance of the incentives for and barriers to low-carbon investment in urban areas. Urbanisation. 2(1):38–58.

- Farvacque-Vitkovic F, Kopanyi M, eds. 2014. Municipal finances: a handbook for local governments. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- GIZ. 2017. The potential of green bonds: a climate finance instrument for the implementation of nationally determined contributions? Deutsche gesellschaft für internationale zusammenarbeit. https://www.giz.de/fachexpertise/downloads/giz2017-en-climate-finance-green-bonds.pdf

- Gorelick J. 2018. Supporting the future of municipal bonds in sub-Saharan Africa: the centrality of enabling environments and regulatory frameworks”. Environ Urban. 30(1):103–122.

- Granoff I, Hogarth JR, Miller A. 2016. Nested barriers to low-carbon infrastructure investment. Nat Clim Chang. 6:1065–1071.

- IMF. 2014. Government finance statistics manual 2014. Washington (D.C): International Monetary Fund.

- Layton D. 2016. Effects of the great recession on tax increment financing in the United States, Georgia and Atlanta. The center for state and local finance. Atlanta: Georgia State University.

- Martimort D, Straub S. 2016. How to design infrastructure contracts in a warming World: a critical appraisal of PPPs. International Economic Review. 57(1):61–87.

- Merk O, Saussier S, Staropoli C, Slack E, Kim J-H (2012), Financing green urban infrastructure, OECD Regional Development Working Papers 2012/10, OECD Publishing.

- National Treasury Republic of South Africa. 2016 December. Municipal borrowing bulletin issue 3 http://www.treasury.gov.za/publications/Municipal%20Borrowing%20Bulletin/ISSUE3.pdf.

- Noel M. 2000. Building sub-national debt markets in developing and transition countries: a framework for analysis, policy reform and assistance strategy. Washington DC: World Bank.

- OECD. 2015. Mobilising the debt capital markets for a low-carbon transition. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- OECD. 2018. Development cooperation report 2018. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Schmidt TS. 2014. Low-carbon investment risks and de-risking. Nat Clim Chang. 4:237–239.

- Smolka MO 2013. Implementing value capture in Latin America: policies and tools for urban development. Lincoln institute of land policy. Cambridge.https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/implementing-value-capture-in-latin-america-full_1.pdf

- Suzuki H, Murakami J, Hong Y-H, Tamayose B. 2015. Financing transit-oriented development with land values: adapting land value capture in developing countries. Washington (D.C.): World Bank.

- UN DESA. 2018. World urbanization prospects. Nairobi (Kenya): United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs.

- World Bank. 2011. Developing a regulatory framework for municipal borrowing in India: main report. Washington (D.C.): World Bank.

- World Bank. 2016. Subnational public private partnership market in developing countries. Washington (D.C.): World Bank.