ABSTRACT

This paper investigates sustainable urban aspects of the Great Bazaar of Tabriz (GBT) in Iran, classified as the world’s largest covered bazaar. Qualitative and statistical research methods employed to analyze the sustainable features of the (GBT) and compare them against four dimensions of the sustainable development model. The results of the public satisfaction survey employed, calculated using SPSS for the GBT, show that the majority of approximately 78% of the interviewees are satisfied with the bazaar’s environment, whereas a minority of approximately 16% declared that they are less happier with the environment. Accordingly, the ‘friendly atmosphere’ has the highest impact on satisfaction with approximately 92%, and the ‘role of trade unions’, with approximately 54%, is the lowest factor impacting public satisfaction with the bazaar’s spatial configurations. Historical and vernacular architectural elements are the main strength of the GBT; the lack of infrastructures to expand e-commerce activities is seen as a weakness; the potential grow number of costumer shopping at the GBT is identified as an opportunity, and international sanctions are interpreted as a threat. Finally, recommendations regarding a more comprehensive approach toward the sustainability of the GBT and the flourishing tourism activity in the Tabriz, in general, are presented.

Introduction

In the nineteenth century, the concept of sustainable development appeared to deal with some of the most serious environmental issues due to ongoing expanding urban areas in the natural environment. In the twentieth century, resource consumption and human development stood tragic destruction of the global environment by researchers (Abdullahi and Pradhan Citation2017). To attain sustainability in urban planning and design, each and every area must be in harmony with the surrounding environment and reconcile with its individual users (Ouria and Sevinc Citation2016).

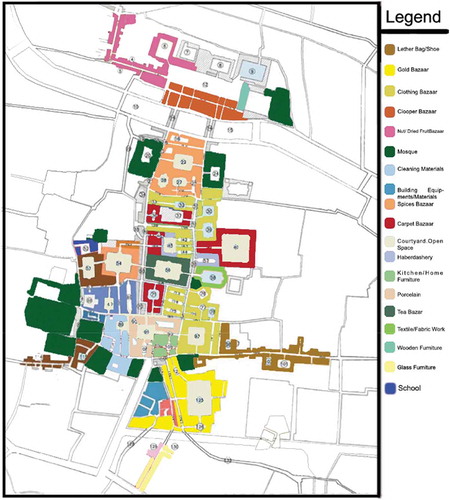

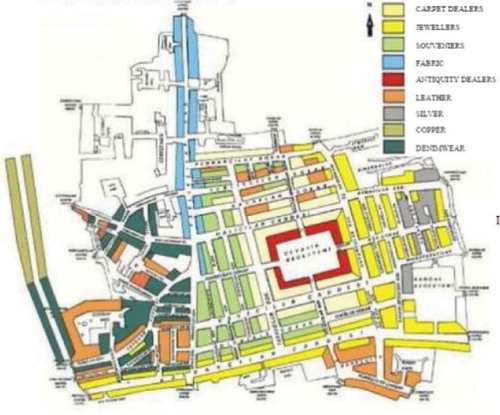

Figure 13. Functional Zoning/Spatial configuration analysis of Tabriz Great Bazaar, Source before rendering: (Edgu et al. Citation2012).

Cities can be compared to living organisms, where perpetuation and growth of one organ depend on the wellbeing of others. Alongside growth, mentalities and ideas are formed. Political ideologies are inspired by the shape and form of cities, and so are a nation’s journey to a better understanding of the self and the public. Spaces impact human behavior as well as a generation’s culture for the next to inspire. Hence, cities are often representative of a nation’s artistic, cultural, and social achievements (Danesh Citation2010). Not only do cities play the obvious part in the global economy (Fanni Citation2006), but they also manifest human cultural achievements as well as how a nation subjectively and intellectually perceives life (Danesh Citation2010).

Traditional bazaars are part of the urban environment of many cities across the world. They can play various roles including contributing to a more sustainable urban environment as well as enhancing a sense of belonging and place attachment (Ashworth and Graham Citation2005). In addition, bazaars also shape the culture of cities by empowering social interactions. Bazaars are multipurpose areas, composed of shops linked together by covered public passageways. Although at first glance, the purpose of building a bazaar may seem to monetize public exchanges, the architecture behind it goes way forward into taking climatic, cultural and social factors into account. In other words, bazaars are of utmost importance in studying and understanding urban sustainability. Bazaars portray the ‘symbioses between the need to create structures for the communities to develop their activities, [and] the need for adaptation to the territorial physical characteristics’ (Correia et al. Citation2009).

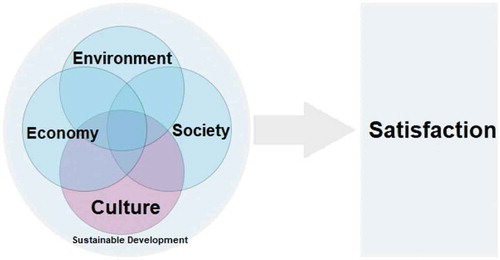

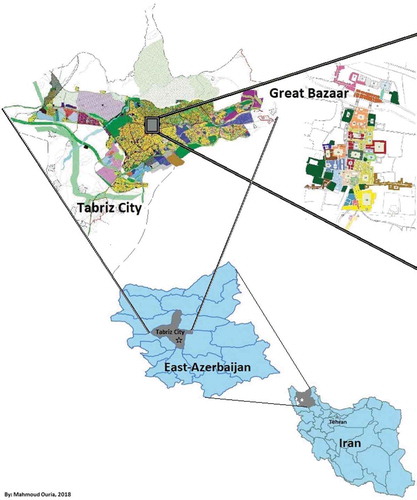

Bearing in mind the multiple purposes of bazaars in an urban environment, the main objective of this paper is to evaluate and highlight the relations that exist between the four dimensions of sustainability, that is, environment, economy, society, and culture, in urban development and public satisfaction which make it possible to find the reasons of existing sustainability and planning for preserving sustainable urban districts (for example, bazaars or trading centers) in future (Opoku Citation2015). Therefore, in terms of satisfaction and concerning sustainable development, this paper argues that development follows satisfaction and sustainable development follows multidimensional satisfaction regarding society, economy, and environment simultaneously. Multidimensional satisfaction from society, economy, and environment addresses how we dealt with different environments. Qualitative and analytical research methods were used to analyze the physical features of the Great Bazaar of Tabriz (GBT) in the city of Tabriz, Iran. Primary data were collected from fieldwork, and secondary data were gathered from published documents. Specifically, a satisfaction survey was employed at the GBT by the authors. Tabriz, as the capital city of East Azerbaijan province, is the biggest city in the Northwest of Iran which is the political and economic center of the region. The city of Tabriz has long been an important center for commercial and cultural exchanges in Iran since ancient times.

Literature review

Satisfaction

Satisfaction, measured through satisfaction surveys, shows how to codify happiness in its different dimensions (Strange and Bayley Citation2008). The surveys of satisfaction posed three main questions: i) levels of satisfaction with one’s own life; ii) satisfaction with the more public realm; and iii) satisfaction with the environmental factors. Also, it has mentioned that happiness rises with income. As people’s properties increase their expectations also rise. Satisfaction is connected to the state of health (socio-environmental status). However, people have a tendency to be more positive about their private life than about the properties, identified as district, city, state or country (socio-economic status). In this paper, tangible factors that affect satisfaction are introduced into environmental sub-title of satisfaction. Additionally, intangible factors are presented to public satisfaction (, and ).

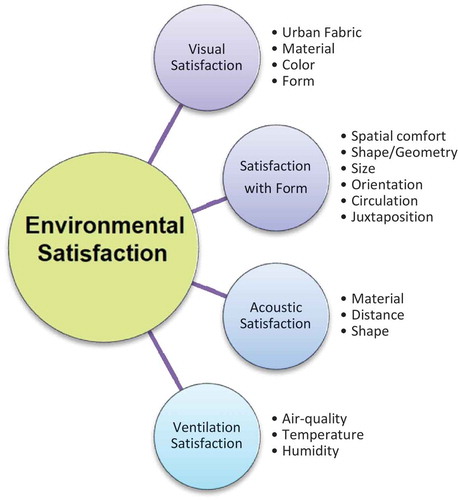

Figure 1. Sub-dimensions of environmental satisfaction (Dillon and Vischer Citation1987).

Figure 2. Sub-dimensions of public satisfaction and features (Bodin Danielsson Citation2010).

Environmental satisfaction

Environmental satisfaction refers to the physical setting and personal feelings. Environmental satisfaction is divided into different sub-dimensions such as floor space (Sundstrom Citation1986), building form, visual or noise pollution, and temperature (O’Neill 1992). Comfort zones are correlated with environmental satisfaction (Brill et al. Citation1984) and can be considered a sub-dimension of environmental satisfaction positively (Marquardt and Charls Citation2002)

The sub-dimensions gauge the level to which specific human necessities have being supplemented. For instance, environmental satisfaction addressed generally by questions such as ‘How do you like the store you are working in there?’ (Kraemer and Partners Citation1977); and ‘All things weighed, how satisfied are you with your workspace?’, the Physical Work Environment Satisfaction Questionnaire (PWESQ) is known as the Human Factors Satisfaction Questionnaire (HFSQ), evaluates satisfaction with analyzing environmental factors related to safety and health, work, equipment, environment, systems, and facilities (Carlopio Citation1986).

User satisfaction is another method to consider environmental satisfaction. The user satisfaction consists of different items evaluating sub-dimensions of environmental satisfaction such as air quality, noise control, thermal comfort, spatial comfort, lighting, privacy, and overall satisfaction (Dillon and Vischer Citation1987).

Public satisfaction

Several studies have been carried out over the past decades which illustrate a sustainable structure underlying public satisfaction with the environment. Neighborhood satisfaction is part of public satisfaction; public satisfaction with environmental quality can be measured as followed ().

Sustainable development

What we now know as the concept of sustainable development is the result of heightened awareness of some developed countries in the 1950s and a decade later about the negative results of industrialization on the environment (Gudmundsson Citation2015). Although the subject alerted more than a dozen nations, it wasn’t until 1992 that the concept was coined and internationally recognized. The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro called for regional attempts at alleviating the consequences of haphazard urban development.

As intriguing as the proposal may sound at first, but the questions it poses are more than answers. For example, ‘what is to be sustained, for how long, and who bears the costs?’ (GudmundssonCitation2015), or was it only brought up to satisfy environmentalists (Norgaard Citation1988). As the result of varied definitions we can come up with, measuring and implementing with sustainability in mind is very challenging (Gudmundsson Citation2015). Requirements analyses show that sustainability can be oblique, misunderstood and subjective to different users. In cases where workers and consumers have clashing perceptions, it becomes unclear which spectrum should be sustained, hence problem-solving processes become more philosophical (Schon and Rein Citation1994).

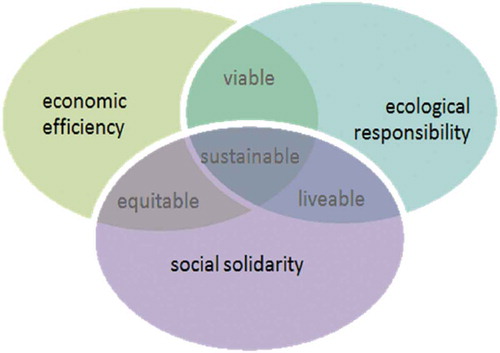

A common criterion for sustainable development, often associated with the Brundtland report of development (Gudmundsson Citation2015) is shown in .

Figure 3. Dimensions of sustainable development (CST, Citation1997; Brodman and Spillmann Citation2000).

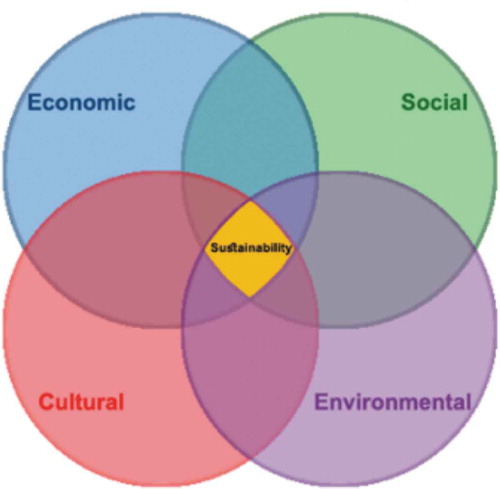

This approach considered economic, ecological and social factors as the main dimensions of sustainable development. Lately, there has been a growing interest in adding another dimension to economic, social and environmental dimensions: cultural sustainability was first suggested by Hawkes in 2001. In a different retrospect, Chiu argued the necessity of considering culture in the scope of housing (Chiu Citation2004). In 2002, Birkeland analyzed the ‘regeneration of post-industrial communities’ in terms of cultural (Nurse Citation2006). Similar ideas with the inclusion of culture were ventured by Throsby4, which focused on the relationship between cultural economy and sustainable development (Throsby Citation2004). Melbourne Principles, a model that adds culture to the fourth dimension, is shown in . This model of sustainability was adopted at the 2002 Earth Summit in Melbourne, Australia (UNEP Citation2002).

Figure 4. Four dimensions of sustainability according to the Melbourne principles of the 2002 Earth Summit (UNEP Citation2002).

Since the concept of culture is relative (UCLG Citation2016), we need to clarify our grounds regarding urban development. The definition of culture varies from one literature to another environmental, economic and social factors are added. Therefore, it is noteworthy to mention the work of Dessein, Soini, and Fairclough. shows three different positions in which culture can be manifested: i) culture in sustainable development, ii) culture for sustainable development and iii) culture as sustainable development (Dessein et al. Citation2015). This paper focuses on ‘culture in sustainable development’. This framework will be assessed through the case study of the Great Bazaar of Tabriz.

Figure 5. Culture and sustainable development: three models (Dessein et al. Citation2015).

Since centuries, the bazar`s environment in Tabriz has not been only a commercial center but also the city’s cultural center that impacts political and social activities (Ouria Citation2016). For example; the Constitutional Revolution would not have been successful without the support of the bazaar economically and culturally in 1906 (Kasravi, Citation1990). Similarly decisions were made for strikes in the bazaar before and after the revolution of 1979. The wolf dance festival, once the most important event of the city, was held in the bazaar from the Seljuqs to the Safavids (Shardin Citation1983). Food and clothing traditions of nations on the Silk Road and Tabriz people were affecting each other mutually by the bazaar. Finally, in spite of international sanctions and lack of governmental investments, Tabriz is seen by many people as the best Iranian city to live in (Iran-Daily Citation2018).

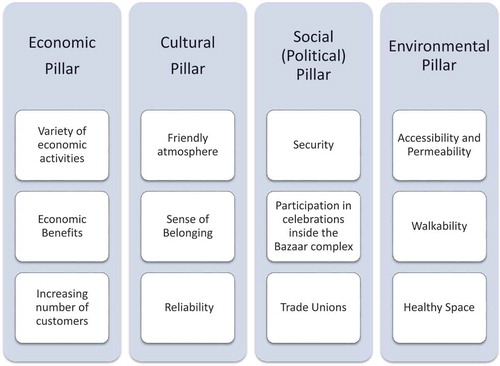

The origin of economics and culture is society. Society is a social system. The social system is governed by social relations. Various choices are made on the basis of differing values of people. However, culture is in fact the basis of these different values of individuals and communities. Therefore, the focus of this work is on culture in sustainable development. At the same time different variables of satisfaction have been acknowledged and classified into the four pillars of sustainable development (see & –).

Table 1. Paired samples statistics.

The role of bazaars in urban environments around the world

Bazaars include cultural, social, physical, and economic functions which are the fundamental part of public spaces in Islamic cities while Agora and Forum were important in Greece and Roman cities respectively (Pourjafar et al. 2014). Both Forum and Agora refer to public space but commercial purposes were highlighted in Agora while the political function was noticeable in Forums. In Bazaars, commercial and political functions are important. Additionally, cultural and religious purposes have been highlighted because of existing mosques, schools, and shrines in their physical structure.

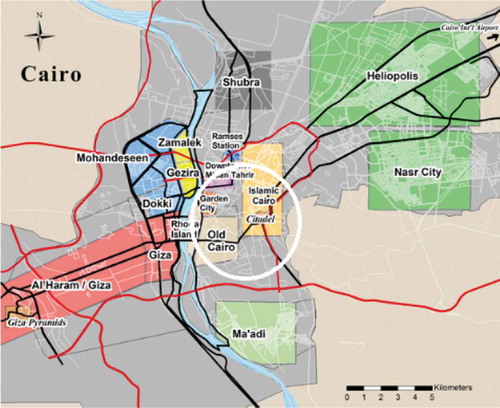

In a sustainable approach to architecture, infrastructures such as bazaars must abide by the principles of sustainable development (Guy and Farmer Citation2001). Bazaars are the central infrastructure in a good number of cities around the world. Understanding their linkage with urban sustainability is paramount. . shows the centrality of the bazaar of Cairo the capital city of Egypt, and how the rest of the city was built in the surrounding vicinity (Ibrahim and Mohamed Citation2005).

Figure 6. Location of bazaar Khan El-Khalili in Cairo, Egypt (Cairomap Citation2016).

Although bazaars were built with intentions other than those of plazas, they seem to have followed the same social, cultural and political patterns. Open spaces of the ancient world, such as ‘agoras’ and ‘forums’, were manifested in the open bazaars of the Middle East. However, these bazaars were covered over time to cope with climatic features. Similarly, in most cases, bazaars were the city center, and housing expanded organically (Edgu et al. Citation2012). According to Kermani & Luiten, bazaars had the same weight as “‘restigious religious, governmental or public buildings”’in shaping the urban fabric of the city (Kermani and Luiten Citation2010).

The concept of ‘functional society’ is visible in old Islamic capitals, where cities were centered on the city’s dominant economic center . Producers, workers, and merchants dwelled in the vicinity of these establishments and, over time, caused main streets and buildings to be developed around them. Since the most powerful people were amongst these same people, city centers also became the core of political decision makings. Therefore, the centrality of bazaars and centrality of other functions have converged to cause the advent of multifunctional architecture based on individual needs (Embaby Citation2014).

Figure 7. Commercial functions of Istanbul grand bazaar in Turkey (Wohl Citation2015).

Inference mechanism

Theoretical framework

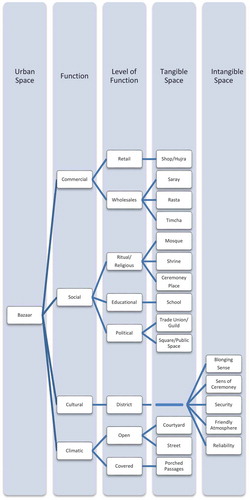

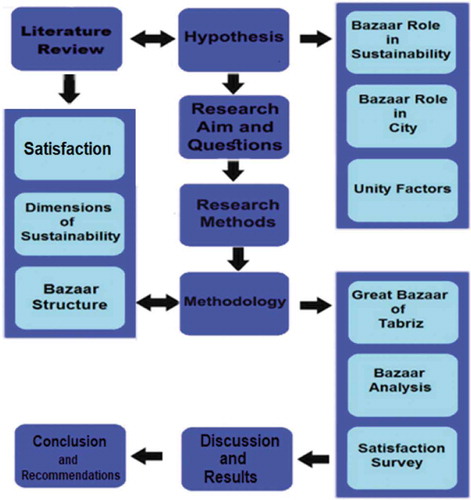

Literature suggests that bazaars have different functions as a public space which impacts the form of city and society. Regarding the concepts of city and society, they refer to physical/tangible and public/intangible spaces. Studies show the importance of bazaars in societies, and we take them as the backbone of a city and take it as the source of sustainability to flow to other parts of the city. Satisfaction from the bazaar may denote successful implementation of sustainable factors in the bazaar. , shows the research design of this paper.

Research aim and research questions

The aim of this paper is to highlight the sustainable urban features and evaluates the correlations between the dimensions of sustainable urban development and public satisfaction. The prime research question of this paper is:

Which dimensions of sustainable development are more correlated with public satisfaction?

As the paper focuses on the GBT, the sub-questions are:

Are the people satisfied with the bazaar’s environment? If yes, why?

Why the architectural components of the GBT are important in public satisfaction?

Research hypothesis

Cultural and social cohesion are tied together; therefore, the impact and consequences of these activities are measured as a function of society (Ralph Citation1997). Although from an anthropological point of view culture precedes society, culture is influenced by society itself. A society is a unique group of individuals who have learned to cooperate with one another. Culture consists of a collection of behavioral memes. In spite of the close internal connections that culture and society share, they are intrinsically different, and yield different outputs. Regarding sustainable development, Culture takes people’s tangible and intangible achievements, learned through social interaction, and transfers them to the next generation. Social behavior is unconsciously impacted by the environment as well as the society it is shaped in. No one is able to escape the limits and boundaries of determined norms and social values since such activities are labeled as deviant and chaotic. Environment determines a set of boundaries on societies and their economies that can only be understood through a better understanding of culture (Ralph Citation1997). Societies and economies are human achievements, and therefore are always transformed through culture and their environments. Whether an environment is created using natural or determined methods can also influence or get influenced by culture. Therefore, culture should be evaluated as a dimension of sustainable development. In terms of satisfaction and concerning sustainable development, this paper argues that sustainable development follows satisfaction. Hence, in this paper, the approach to culture is ‘culture in sustainable development’ in the environment which shows satisfaction (as shown in ).

Methodology

Research methods

This paper employs analytical, qualitative, and statistical research methods. Primary data were collected through public satisfaction survey. Secondary data were gathered from the content analysis of several published documents. In order to evaluate the satisfaction variables, a two-step procedure was employed. First, a questionnaire was designed and handed over to individuals inside the bazaar randomly. Four hundred and thirty questionnaires were distributed. Each questionnaire was composed by a single question i.e.Is the bazaar`s environment satisfactory for you? If yes, please, list the items in brief. As a result of data generated from the distribution of 430 questionnaires, 12 reasons highlighting public satisfaction regarding the bazaar were identified which was the base of analysis. Secondly, based on the results gathered from the completion of the first step, a second questionnaire was employed to evaluate the public satisfaction regarding the 12 reasons that identified through the first questionnaire. In other word, 430 people mentioned different items that they suppose them as satisfactory in the first questionnaire but only 12 items were shared among 430 questionnaires. The 12 reasons for the first questionnaire supposed as a variable of satisfaction and analyzed in the second questionnaire. To measure the confidence interval in statistical conclusions, the standard (Std.) deviation of data was measured in SPSS software. Low standard deviation indicates data to be close to the mean (as shown in ).

Table 2. A SWOT analysis of the GBT.

The case study

Tabriz city is located in the Northwestern part of Iran. The city of Tabriz has long been an important center for commercial and cultural exchanges in Iran. The GBT has been the commercial center of Tabriz for over a millennium; however, it was neglected for centuries, and then re-established its importance in the thirteenth century when Tabriz became the capital city of Safavid dynasty. The city, alongside the bazaar, was the commercial hub of trade routes between the East and the West up to the 18th century (UNESCO Citation2010). shows the location of the GBT.

The GBT is the world’s largest covered bazaar; and, according to UNESCO, an excellent pattern of a cultural and traditional commercial system (UNESCO Citation2015). Being recognized as a UNESCO world heritage site also adds international value to the bazaar (Radoine Citation2013). The interconnectedness of the architectural fabric alongside the organization of the bazaar has turned into a single integrated entity preceded by centuries of continual functioning for over a century. Located along the Silk Road, the GBT is composed of brick structures, buildings, and spaces that come together to provide various functions for the people and the city. These functions range from trade-related to social, educational, and religious activities. shows this integration over time along the city.

Figure 11. The spatial configuration of the Great Bazaar of Tabriz (Radoine Citation2013).

It should be noted that the policymakers tried to reinforce the commercial and cultural exchanges of the GBT but it could be more effective by making wise policy decisions such as controlled endowment policies as well as tax exemptions (UNESCO Citation2010) These policies could not only perpetuate the centuries-old commercial power but can also empower socio-cultural interchange, in which people from different cultures, professions, and backgrounds cohabit to form a unique living entity. However, the role of unions and liberal economics are limited in the market regarding religion economics (Vakif system) and economic policy objectives which cause opposing government intervention in the free market and forbids open competition and free trade. In other words, inappropriate regulations caused uncontrollable inflation because the present policies neither follow the global economy nor traditional methods.

From an architectural point of view, immensely diverse buildings and spaces of the bazaar are beautifully integrated to reciprocate its various functions. The design of the bazaar is one of the masterworks of Azerbaijani style of Iranian Architecture; used by others as an archetype for Persian urban planning (Ouria Citation2016). In Azerbaijani styles of Iranian architecture, bazaars are typically formed at the center of the city, either organically or in a planned way. Contrary to that, the layouts are mostly linear/clustered in shape, by which the public and socio‐cultural spaces are positioned utilizing these forms (Ouria Citation2016).

From radiating aesthetics to creating social interactions, the GBT has been creating value for the city’s citizens, but has had a differing reason for its survival, that is the mutual respect between humans and the environment (Ouria Citation2013). Vernacular and climatic techniques used in creating this masterpiece, provide spaces that adequately satisfy citizen expectations and requirements. The GBT is an ideal archetype for sustainability analysis, for it encompasses a large area of Tabriz and acts as a commercial hub at the heart of the city (ICHTO, Citation2013).

The socio-economic dimensions of the GBT

The exchange of goods or services (commerce), not only satisfies the needs and wants of agents, but also ‘enables establishment of legal and ethical foundations, strengthening of social ties, improving cultural relationships, trading values and technology as well as goods on safe and secure routes’ (Edgu et al. Citation2012). Similarly, the GBT alleviates commercial as well as the aforementioned social dynamics at the center of the city of Tabriz through a congregate of functions it provides like the bazaar in Cairo. In spite of the fact that manufacturing has been relocated to the districts of the city, the GBT is still buoyant and alive (Weiss and Westermann Citation1998; Mohammadi and Oliveira Citation2015). Moreover, it seems that the Bazaar is the fundamental element in any further commercial developments of the city; e.g. tourism and international trade. Indeed, the importance of the bazaar should be amplified in order for the policymakers to keep the bazaar alive—socially, culturally, and economically dynamic—by taking proper urban management strategies into account (Edgu et al. Citation2012).

The interlinkage between the bazaar and the urban environment

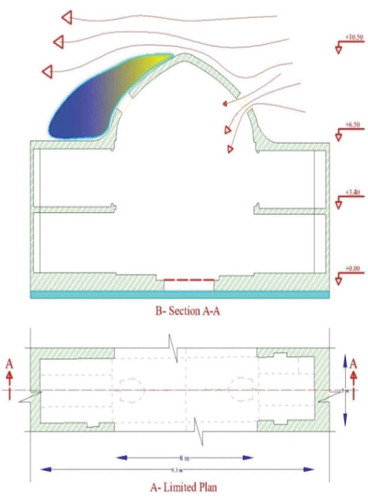

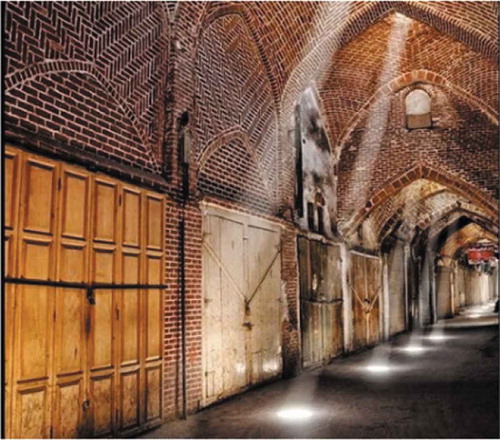

As a result of observation, the GBT consists of a chain of connected brick structures, buildings, and enclosed spaces, all of which bind the bazaar’s functions and continues to persevere its sustainability (UNESCO Citation2010). The first floor is composed of walking and commercial spaces, whereas the warehouse and offices are separated and situated on the second floor. Offices and workshops are less visible and less accessible, for one need to take the stairs to get there (as shown in ).

Figure 12. A Rasta in the Great Bazaar of Tabriz (UNESCO Citation2017).

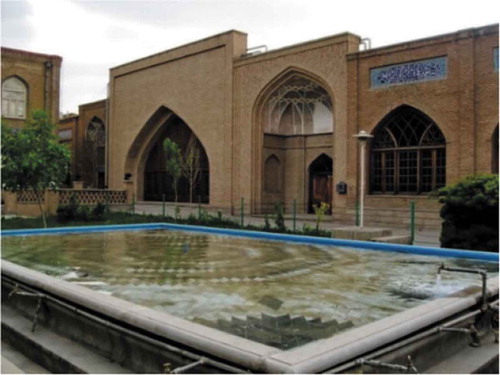

In addition to commercial structures, the bazaar also consists of mosques, courtyards, schools, and several streets. The largest covered bazaar in the world takes the relation between its architecture and the city-region’s climate to pure perfection (UNESCO, Tabriz Historic Bazaar 2010); (Mohammadi and Oliveira Citation2015). shows the elements of the GBT and their respective descriptions or functions.

Table 3. Elements and functions of the GBT.

Spatial configuration analysis of the Great Bazaar of Tabriz

Many dynasties of the past centuries in Iran were unable to create efficient bureaucratic municipal institutions in large scales; therefore, had to settle for compromises. For example, during the Seljuq and Safavid dynasties, delegates carry out their orders to individuals. People of each profession established their own guilds as a means to have direct relations with the government. Nevertheless, the higher bureaucracy had the final say, which was delivered to the people through Fetva (religious guiding/ordering system). As far as the people had the right for a say, was held by census under the provision of the government’s delegates. The medium order was carried out by each Khanliq (governor, or mayor), and lower order by each Vakıf (foundation). This medium- and low-order institutions provided limited health and education services to the public, at a completely separate level from higher bureaucracy and the army.

Today, people can find rāstās in Iranian Azerbaijani bazaars. A rāstā (or arāstā) is a location of similar good-sellers that can be found in specific parts of a bazaar or on specific streets. This is, in fact, an outcome of guilds who preferred to stay close to one another and establish uniform costs for their products. Some apparent examples include cloth merchants, jewelers, carpet makers, knife makers, goldsmiths, dairymen, honey sellers, fishmongers, potters and international traders who traveled through the Silk Road were fascinated by Iranian Azerbaijani way of organizing shops and found these arrangements beneficial for their search for goods and trade opportunities. As a consequence of guilds and rāstās, each section of the bazaar has a group of sellers who neither compete for location nor for the price, but sell each good at uniform price and quality.

Contemporary Iranian big/chained shopping centers are believed to have the GBT as their influence. The current spatial settings are similar to the bazaar’s saraa’s that are connected by clusters, shared spaces that allow for cultural confluences, as well as nodal space configurations that allow shop owners to gather in solidarity ().

The GBT shares development features with other comparable bazaars as in stretching alongside rāstās. However, allocation of khans on one side and saras on the other make it distinct in design and development (as shown in ). The findings of Edgu et al. suggest that the philosophy behind the development schema of the bazaar was the ‘formation of saras alongside the main arteries’ (Edgu et al. Citation2012) like Great Bazaar of Istanbul city. demonstrates the GBT’s schema with the saras hidden from view. The effects of the linear typology of rāstās are clearly visible.

Figure 14. The schema of the spatial configuration of the Great Bazaar of Tabriz (Edgu et al. Citation2012).

Environmental features of the bazaar

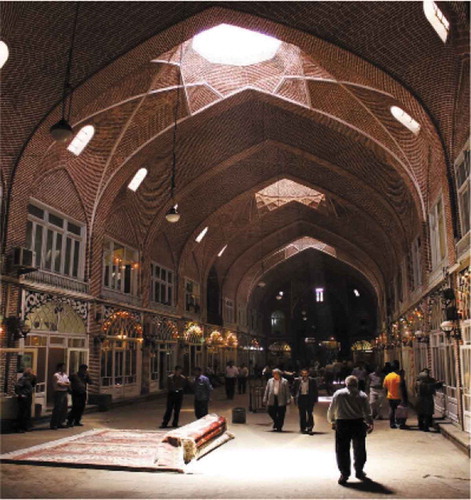

The GBT was built with the city’s climatic conditions in mind. Thermal heating in winter and natural air motion through domes during summer keep the spaces habitable throughout the year (Ouria Citation2013). Plenty of open spaces, such as courtyards increase environmental possibilities. For example, waterfalls and trees make the hot summers more bearable, add up to the satisfaction of individuals, and provide shape as well as visibility to their surrounding shops (as shown in ).

Figure 15. Organizing buildings around a courtyard in the GBT (Pouya Citation2017).

Because bricks have strong thermal mass, the GBT stores heat efficiently using this material as its main building block (Watson and Ghobadian Citation1992). Heat levels, as well as lighting, are sufficient enough in the cold winters of Tabriz to keep the shops in business.

The air inside the bazaar is most of the time clean, partly due to the vernacular choice of materials, and also as a result of keeping cars and small manufacturers out. Environment-friendly materials, natural ventilation, use of greens and clean waters in open spaces have all contributed to the sustainability of the bazaar.

Some of the findings of this research were interestingly sustainable elements such as; vernacular materials, solar and wind performance of domes, covered pedestrian paths, permeable entries, and accessible zoning.

Materials and formation of architectural elements

The geographically mountainous location of Tabriz makes the city endure severely cold winters. The climatic situation during summer time has no advantage either since temperature variation between daytime and night are noticeably divergent. Climatic conditions were a challenge for any sustainable natural design. Nonetheless, architectural measures were accounted for in designing the covered GBT: the materials used as well as the design both help the bazaar absorb a sufficient amount of solar energy and in parallel implements organic ventilation.

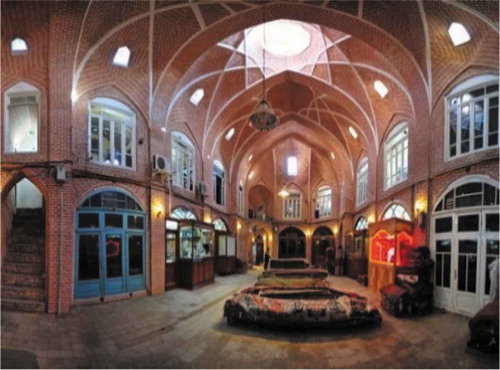

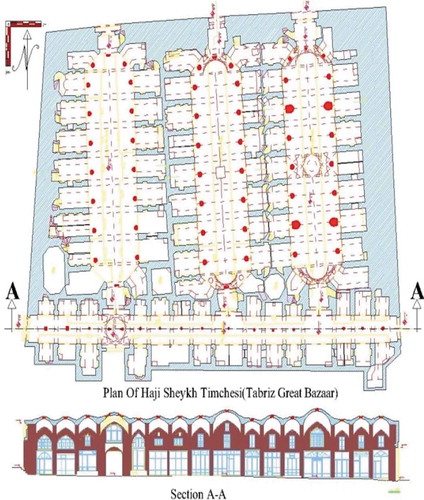

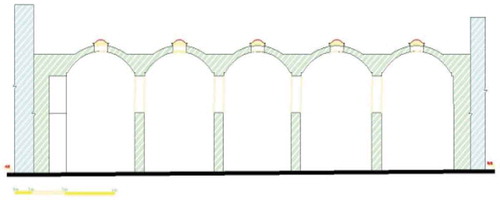

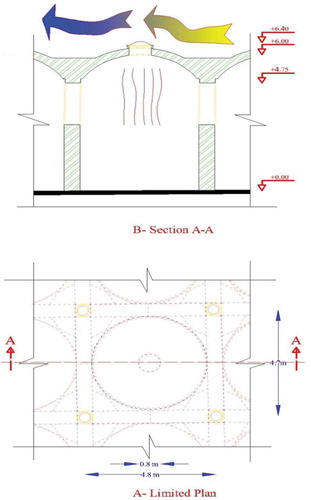

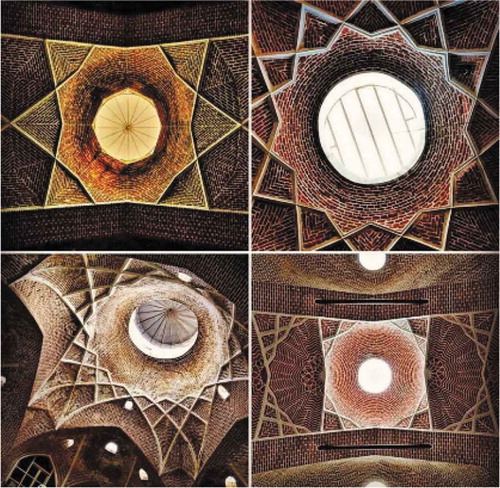

By taking Haji-Sheykh Timchesi as an instance, this section is in principle a largely covered brick complex consisting of public buildings and small stalls, accessible by lanes (as shown in ). At first glance, the bazaar resembles ‘a complicated set of tunnels’ designed for people, not vehicles (Ouria Citation2013). The vaults implemented in high ceilings of the lanes admit light and offer natural ventilation (as shown in –). Indeed, the ceiling (covered nature of the bazaar) protects the interiors from rain and snow during winter and prevents sunlight from being caged inside the bazaar. The exterior structure of the roof also plays a big role in controlling natural ventilation. For example, arch-shaped domes reflect much of the sunlight, whilst providing aerodynamic characteristics that help ventilation. (Ouria Citation2013). The size of the domes was also put into consideration, as the smaller the size of the domes, the less heat can escape from the inside. Moreover, the cardinal positioning of the bazaar permits solar energy to be absorbed from the east and south.

Figure 16. Lined stalls in Haji-Sheykh Timchesi in the GBT (Ouria Citation2013).

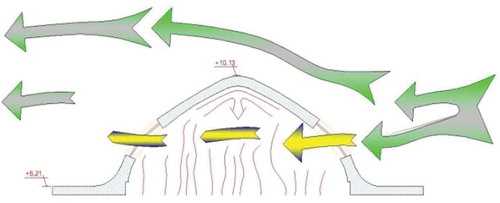

Natural ventilation was one of the biggest challenges to face in the design of any covered structure. The first step to take in solving this problem was to implement vents to let air flow and evacuate heat. Capturing the heated air into the hollowed space of domes used to provide healthy organic ventilation (, and ).

Figure 17. Circular vents of short domes (Ouria Citation2013).

Figure 18. Organic air circulation caused by pressure and temperature differences. (Ouria Citation2013).

The shape of the domes creates a hollowed space beneath, which is ideal for capturing heat and pollution. Both production pollution created by machines and workers and pollution created by the normal daily breathing of visitors rises alongside heat toward the ceiling. Heat and pollution can flow from one dome to another, and eventually escape the domes from their summits. Positioning the domes next to each other is key in a natural flow of heat and pollution from one to the other. Cross-motion of air between the summits of domes allows for air replacement; therefore, fresh air enters the bazaar to replace pollution as well as inside heat.

In total, there are two types of ventilation methods used in the GBT (Ouria Citation2013). Type one is natural wind motion flowing between two axial vents used in spherical domes and arches. Type two uses vertical vents on top of the domes using differences in air pressure technique to replace warm air with external cold air (Kasmai Citation2002). The former is typically implemented in steep-sloped arches and domes, and the latter is typical of moderately sloped domes. It is worthy to mention that these types of ventilation are specific crowded spaces of the bazaar, formally known as Timcha ( and ). Using the two techniques is the most economically and environmentally viable method using natural resources (Ouria Citation2013).

Figure 19. Vents in the GBT (Kalantari Citation2017).

The first type of ventilation, as it is currently known, uses laws of thermodynamics. Differences in temperature cause air pressure to substitute air in accord with the prevailing wind direction. and are graphical demonstrations of thermodynamics of the dome.

Figure 20. Thermodynamic analysis of the dome (Ouria Citation2013).

Figure 21. Two axial vents of keen slopped domes (Ouria Citation2013).

Using traditional techniques, the sustainable system of bazaar not only provides fresh air and natural daylight to flow inside but also protects it from moisture. Since bricks are predominantly created from clay, the structure of the bazaar should be protected from humidity created from daily human inhalations ( and ) (Forutani Citation2006).

Figure 22. Organic ventilation and lighting in the GBT (Moghaddam Citation2017).

Figure 23. Natural lighting and ventilation of Muzefferiye Timcha in the GBT (Angabini Citation2010).

Formation and materials not only assist in solving climatic problems but also define its sense of space and effect social human activities.

Socio-cultural features of the bazaar

In this paper, satisfaction is assumed as the determining factor in evaluating the socio-cultural aspect of sustainability of GBT. Data reveals that social interactions take place in the bazaar along with commercial activities, and consequentially affect a culture that spreads from the bazaar to other urban areas within the city of Tabriz. Tabriz remains to invigorate traditional historic values, inspired by the cultural sustainability of its bazaar located at the core area of the city. This influence stems from functions of the bazaar that make it more than being a merely commercial center. The multifunctional nature of the GBT is, in fact, a reason for its survival for centuries. Non-commercial functions of the bazaar have had the people of the city interact with one another in social, cultural and religious gatherings. In order to accumulate such a high level of achievement, defined spaces were designed and erected. Non-Commercial spaces of the GBT can be noted as; courtyards, squares, bathhouses, mosques, morning or ceremony spaces, schools, sports clubs, tea houses, and tombs.

Interaction between parents who pick up their children from schools, social discussion that place in public bathhouses and social gatherings at teahouses that pave the way for discussing personal problems are a few examples of socio-cultural exchange; however, the unrivalled manifestation would be the public meetings of shop owners at mosques (), who collect money for the poor, and seek informal consultancy with their businesses (Sangsai Citation2008).

Figure 24. Gathering dignities to denote for poor people in the central mosque of the bazaar (Gholami, 2012).

Besides the aforementioned social activities, the GBT is also the source decision-making processes that are later spread around the city as news or rumor. Satisfaction from these spaces impact the memories people create is an experience beyond merely a trade or good economics.

Results & discussion

Whereas sustainable development follows satisfaction, and sustainable development includes different dimensions sus as social, cultural, economic, and environment, therefore, satisfaction should consist of sustainable developments dimensions.

The majority of the interviewee are satisfied with the bazaar’s environment (78%) whereas a minority declares that they are not happy with the environment (16%).

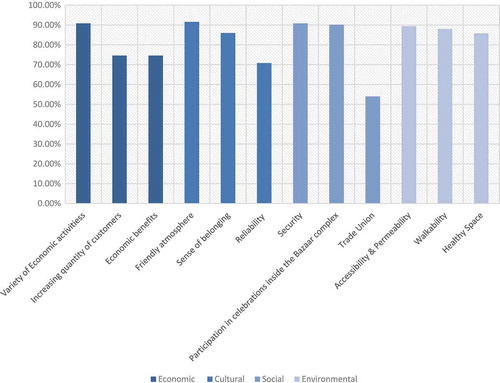

Those respondents who are satisfied with the Bazaar’s economic, social and architectural environment have stated 12 different reasons for their satisfaction such as economic benefits, increasing the number of customers, variety of economic activities, belonging sense of environment, security, friendly atmosphere, participation in celebrations inside the Bazaar complex, accessibility and permeability, walkability, healthy space, mixed activities that take place at the Bazaar, trade unions controlling. In other words, the first questionnaire did ask people why do you satisfy with GBT`s environments? They noted a lot of factors out of which 12 were noted in the majority of the answers. The second questionnaire designed based on the first questionnaire including 12 questions that were emphasized people in the GBT environment. Each question supposed as the independent variable. A paired-samples t-test was conducted to compare the rate of satisfaction and independent variables as follows.

According to the (report of paired samples T-test data in APA style), there was a significant difference in the scores for satisfaction (M = 4.3380, SD = .47358) and performance of trade unions (M = 2.7016, SD = .57154). On the other hand, there is a significant correlation in the scores for satisfaction (M = 4.3380, SD = .47358) and friendly atmosphere (M = 4.3287, SD = .81839). These results suggest that trade unions really do not have an effect relation on the satisfaction while the friendly atmosphere is the most important variable. The results suggest that trade unions should pay more attention to their duties people should keep the friendly atmosphere of the GBT environment.

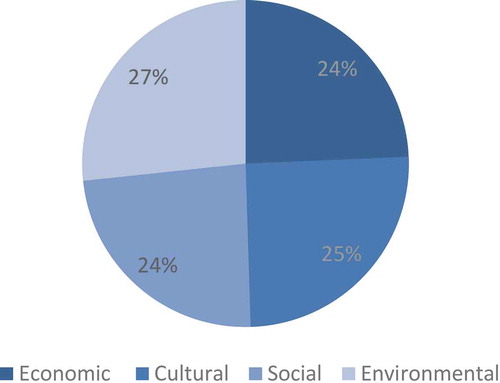

Classification of different variables of satisfaction into four pillars of sustainable development made it possible to understand and estimate the weight and value of each variable into pillar, development, and satisfaction statistically as follows.

shows the mean percentage of each variable of satisfaction into four pillars of sustainable development separately. According to the data, friendly atmosphere impacts, satisfaction sense of Bazaar environment with a rate of 91.6% is the highest factor. On the other, the role of trade unions with a rate of 54% is the lowest factor correlates with satisfaction. Analyzing the variable of satisfaction made it possible to classify the factors into different groups which are related to the four dimensions of sustainability.

shows the distribution of satisfaction states into four dimensions of sustainable development. The distribution of satisfaction correlation into four dimensions of sustainable development shows the role of all dimensions simultaneously. The distribution shows a balance that has caused the sustainability of the Great Bazaar for centuries, as well as the satisfaction of individuals.

Figure 27. Distribution of satisfaction correlation with four dimensions of sustainability in the Tabriz Bazaar.

The GBT has a myriad range of similarities with both Istanbul and Cairo bazaars physically, socially, and commercially. For examples, the formation of rāstās which effect on social activities and orientate commercial hubs are similar in GBT, Istanbul bazaar, and Cairo bazaar. The results show that GBT has a positive effect on the satisfaction of both shop owners and customers. Courtyards make trades of independent nature possible and affect commercial activities in general Economical yet highly sophisticated techniques of energy management such as using wind direction for ventilation and passive solar energy for heating reduced the need for using fossil fuels. Purely architectural techniques applied in the GBT have made sustainable development possible.

Conclusion and recommendations

The bazaar as an urban space includes four main functions (commercial, social, cultural, and climatic) which are divided into different levels and spaces. Satisfaction, measured through satisfaction surveys, shows how to codify happiness in its different dimensions. People have a tendency to be more positive about their private life than about the properties, identified as district or city country (socio-economic status). Tangible factors that affect satisfaction occur in physical space while intangible factors occur in a cultural space. Tangible and intangible spaces can be noted in the GBT. In terms of tangible space, it is remarkable that commercial, social and climatic functions occur in a tangible space. In contrast, an intangible space is conceivable in all districts of the bazaar even in the tangible spaces which limit in cultural function. We have these types of experiences (as a result of cultural functions) that are shaped in intangible spaces, and on other hand are the commercial, social and environmental experiences, which happen in the tangible spaces. Functions and spaces of Tabriz bazaar are presented in for analysis.

Functions of the bazaar are divided into four main levels that is commercial, social, cultural, and climatic. The climatic function consists of covered and open spaces, which include environment-friendly courtyards and porched walkable passages respectively. These elements not only enable sustainability but also empower the commercial function of the bazaar. On the other hand, the bazaar is an enabler of social gatherings (social function) as a vantage point for holding rituals, mourning, religious acts, educational programs, hangouts, and even political campaigning. The cultural function of the bazaar is its district members having cultural experiences in the intangible space, parallel to other functions. In effect, cultural experiences tend to cohere with the spatial sense of other functions.

The GBT has kept its sustainability through cultural, environmental, and economic dimensions since 1000 years ago. To maintain its sustainability, decision makers must tackle the political and economic barriers which could pose a threat to cultural values maintenance in Tabriz, East Azerbaijan Province, and Iran.

It is strongly recommended to consider GBT as the core of the Tabriz 2018 (the Tourism Capital of Islamic Countries in 2018). Therefore, strength, weakness, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) of GBT is concluded to illustrate its actual and potential features as follows.

On the scope of the managerial level, this paper suggests enhancing the preservation of the unique features of the GBT, particularly its architecture. In addition, it is of utmost importance to understand and value the Bazaar as a vital element for urban development. The role of trade unions can be further improved by the government. Better public transportation services offered within the bazaar’s premises can greatly contribute to the dynamics and vibrancy of the bazaar’s atmosphere. The Bazaar has an enormous amount of potential for boosting a sense of belonging and can also be the core of the city in tourism development. Integrative approaches that respect local communities, contribute to their well-being and internalize social responsibility is necessary to achieve these goals. Whereas the revitalization and preserving historic complexes such as the GBT are complicated, amassing comprehensive strategies dealing with aspects of obligations is necessary. Although existing management methods applied to the GBT are helpful, there is a need to appropriate strategies covering contemporary requirements. Additional strategic recommendations toward sustainability of the GBT and flourishing tourism activities in Tabriz and Iran are further identified:

improving international relations regarding economic flourishing and sustainable development;

tourism-based planning regarding attractive and flexible policies;

providing specific tourism planning for the central and historical context of the city;

authorizing and empowering unions and non-governmental organizations;

balancing supply and demand;

supporting local products such as silk, wool, and leather which are base of vernacular handicrafts;

logistic planning for economic prosperity;

enhancing municipal services;

designing adequate and promotional websites to introduce touristic attractions and the historic importance of the GBT;

enhancing tourism services and facilities on the GBT by related organizations;

creating an appropriate database inside the market to guide tourists from relevant organizations;

enhancing health facilities in the GBT;

continuous handling of the floor by the relevant authorities in relation to continuing depreciation due to congestion and population movements and hand-held vehicles;

preserving and restoration of old monuments locating around the GBT;

enhancing the quality of pavements and compromising textures regarding the historic area and suitable street network.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mahmoud Ouria

Mahmoud Ouria was born in Tabriz-Iran (1986). A part of the top students in university at BSc level and member of young researchers & elite club. MSc in Urban Design from EMU in Famagusta, Cyprus (2017). Thesis in Solar design. Has published a few book, lecture notes, and papers. He was Lecturer at NEU in Nicosia (2014-2015), courses taught (B.Sc. Environmental Science I, II). Skillful in architectural drawing software programs and solar energy simulators. Responsible for shifts at the NEU Grand Library (2013). Performed and controlled projects activity scheduling and monitoring in Construction Company in Iran (2009-2013) and (Since 2018).

References

- Abdullahi S, Pradhan B. 2017. Spacial mdeling and assessment of urban form analysis of urban growth. Switzerland: Springer; p. 17.

- Angabini S. 2010 Jul 31. Tabriz historic bazaar complex (Iran (Islamic Republic of)). whc.unesco.org/en/list/1346

- Ashworth, Graham. 2005. Senses of place senses of time. Wilshire. Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Bodin Danielsson C. 2010. Architectural Design’s Impact on Health, Job Satisfaction and Well-being [ PhD Dissertation]. Stockholm: KTH.

- Brill M, Margulis ST, Konar E, Bosti. 1984. Using office design to increase productivity. Buffalo (NY): Workplace Design and Productivity, Inc.

- Brodman U, Spillmann W. 2000. Nachhaltigkeit: standortbestimmung und Perspektiven. Teilsynthese des NFP 41 aus Sicht der Umweltpolitik mit Schwerpunk. Berne: Nationales Forschungsprogramm.

- Carlopio JR. 1986. The development of a human factors satisfaction questionnaire. In: Brown O Jr, Hendrick HW, editors. Human factors in organisational design and management. Elsevier; p. 559–566.

- Cairomap. 2016 Oct 1. http://wikitravel.org/en/File:Cairomap.png.

- Chiu RLH. 2004. Socio-cultural sustainability of housing: a conceptual exploration. Housing Theory and Society. 21:65–76.

- Correia A, Pinheiro M, Manuel L. 2009. Sustainable architecture and urban design in Portugal: an overview. Ren Energy. 34(9):1999–2006.

- [CST] Centre for Sustainable Transportation. 1997. Definition and vision of sustainable transportation. Ontario:The Centre for Sustainable Transportation.

- Danesh J. 2010. Formation fundamentals and physical organization principles of Islamic city Iranian. Islamic Cities. Tehran.

- Dessein JK, Soini G, Fairclough G. 2015. Culture in, for and as sustainable development: conclusions from the COST action IS1007 investigating cultural sustainability. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Dillon R, Vischer J. 1987. Derivation of the tenant questionnaire survey assessment method: office building occupant survey data analysis architectural and engineering. Ottawa: Public Works Canada.

- Edgu E, Unlu A, Salgamcioglu M, Mansouri A. 2012. TRADITIONAL SHOPPING: a syntactic comparison of commercial spaces in Iran and Turkey. Proceedings: Eighth International Space Syntax Symposium; Chile, Santiago: PUC. p. 8099.

- Embaby ME. 2014. Sustainable urban rehabilitation of historic markets “comparative analysis”. Int J Eng Res Technol (IJERT) 3(4):1017–1035.

- Fanni Z. 2006. 2006. CitiesandurbanizationinIranaftertheIslamic revolution. 23(6):407–411.

- Fars News Agancy. 2012. Directed by Khalil Gholami.

- Forutani H. 2006. Building materials. Tehran: Rozaneh.

- Gudmundsson, H. 2015. Sustainable transportation indicators. Sus Dev Springer. (1):A49.

- Guy S, Farmer G. 2001. Reinterpreting sustainable architecture: the place of technology. J Archit Educ:140–148.

- Ibrahim N, Mohamed Y. 2005. Perception of local architects on sustainable architecture in Malaysia. Build Environ J: 2 (2):49–65.

- ICHTO, East Azerbaijan Office, Tabriz, Iran. 2013. Rehabilitation of Tabriz Bazaar. Aga Khan Foundation, an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network, East Azerbaijan Office.

- Iran-Daily. 2018 Apr 24 [accessed 2019 Jan 10]. http://www.iran-daily.com/News/213849.html?catid=3&title=Tabriz–the-best-Iranian-city-to-live-in.

- Kalantari B 2017 Jan 14. www.sepehr-sayahan.com/newsurl.

- Kasmai M. 2002. Climatic & architecture (in Persian). Isfahan: Khak.

- Kasrovi A. 1990. Constitutional revolution in Iran (in Persian). Tehran: Amir Kabir.

- Kermani A, Luiten E. 2010 Jan. Preservation and transformation of historic urban cores in Iran, the Case of Kerman. WSEAS Trans Environ Dev. (1):6.

- Kraemer S, Partners. 1977. Open-plan offices: new ideas, experience and improvements. London (UK): McGraw-Hill.

- Marquardt V, Charls. 2002. Environmental satisfaction with open-plan office furniture design and layout. Ottawa: Institute for Research in Construction National Research Council of Canada.

- Moghaddam B 2017 Jan 22. https://tr.pinterest.com/pin/301319031302483998/.

- Mohammadi A, Oliveira E. 2015. The sustainable architecture of bazaars and its relation with social, cultural and economic components (Case study: the historic Bazaar of Tabriz). Intl J Archit Urban Dev. 4(1): 8–16

- Norgaard RB. 1988. Sustainable development: A co-evolutionary view. Futures. 20:606–620.

- Nurse K. 2006. Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. London: Commonwealth Secretariat Malborough House.

- Opoku A. 2015. The role of culture in a sustainable built environment. Sus Oper Manage Springer, Switzerland:37–52.

- Ouria M 2013. Sustainable architecture and its effect on reduce the rate of green-house gasses in buildings of Great Bazaar of Tabriz-Iran. Industrial & Hygiene Conferance. Publication of Sharif Technical University, Tehran.

- Ouria M. 2015. Introduction to architectural history of Azerbaijan from stone ages to Qajar dynasty (in Persian). Tabriz: Akhtar.

- Ouria M, Sevinc H. 2016. The role of dams in drying up lake Urmia and its environmental impacts on Azerbaijani districts of Iran. SAUSSUREA (ISSN: 0373-2525) 54–65.

- Pouya. 2017 Feb 17. tabrizemodern.blogfa.com.

- Radoine H. 2013. Rehabilitation of Tabriz bazaar. Tabriz: ICHTO East Azerbaijan Office.

- Ralph PL. 1997. World civilizations. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Sangsai E. 2008. History and architecture of Tabriz bazaar. Tabriz: Sotudeh.

- Schon DA, Rein M. 1994. Frame reflection: toward the resolution of intractable policy controversies. New York: Basic Books.

- Shardin J. 1983. Shardin travelogue, Tabriz Chapter. Translated to Persian by Arizi, H. Tehran: Negah Publication.

- Strange, T, and A Bayley. 2008. Sustainable Development. Linking Economy, Society, Environment Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Paris: OECD.

- Sundstrom E. 1986. Workplaces: the psychology of the physical environment in offices and factories. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Throsby D. 2004. Hans abbing, why are artists poor? the exceptional economy of the arts. J Cult Econo. 28(3):239–241. Springer.

- [UCLG] United Cities and Local Governments. 2016. Agenda 21 for Culture: why must culture be at the heart of sustainable urban development? Online: UCLG. http://www.agenda21culture.net/

- UNEP. 2002. Melbourne principles. Melbourne:United Nations: Environment Programme.

- UNESCO. 2010. Tabriz Historic Bazaar, East Azerbaijan, UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2015. World heritage list- tabriz historic bazaar complex, East Azerbaijan, (UNESCO).

- UNESCO. 2017 Jan 2. whc.unesco.org.

- Watson D, Ghobadian V. 1992. Climatic design. Tehran: Tehran University.

- Weiss W, Westermann K. 1998. The bazaar: markets and merchants of the Islamic world. Thames and Hudson: Publications.

- Wohl S. 2015. The grand bazaar in Istanbul: the emergent unfolding of a complex adaptive system. Int J Islamic Archit. 4:39–73.