ABSTRACT

Peri-urban land access in Tanzania is adversely embroiled in a dual system that is both formal and informal. Each system is driven by different actors with diverging interests. This paper aims at demonstrating views of the actors’ on the dual system in peri-urban areas. Case study strategy was employed in this study and mixed methods of data collection used. In-depth interviews, household questionnaires and document analysis were employed to collect data. Findings demonstrate that although the formal land-access system is unnecessarily bureaucratic, the associated benefits are worthwhile compared to the informal system. Despite the challenges of the informal system, it remains predominant because of multiple factors including the ability to bridge the gap of high demand for planned and surveyed land that the formal public sector has failed to meet. Thus, it is important for the government to address challenges in the formal land-access system through institutional and policy reforms. There is also need to coordinate and regulate the activities of actors involved in informal land-access processes, if effective land governance in peri-urban areas is to be achieved.

1. Introduction

Land access is a controversial topic in most developing countries. As a resource, land creates socio-economic strata among the populace. Its access and means of access are thus fundamental factors for consideration. Access has been defined as ‘the ability to derive benefits from things’ or the ‘right to benefit from things’ (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003, p. 153). These two definitions and their application are contentious in regard to property and resources. Whereas ‘the ability to’ alludes to the power one can utilise to benefit from something, the ‘right to’ looks at undisputed authority to benefit from something. In utilising resources, other factors such as social relationships can support or constrain realisation of benefits (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003; Moyo Citation2017). Therefore, in order to analyse access, Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003) propose that it is vital not only to look at means and processes, but also at other yardsticks such as relations among actors and how these enable or constrain them from deriving benefits. In this paper, access as 'the ability to derive benefits from things' is adopted because land in Tanzania is a public resource vested in the presidency and citizens have only user rights. Benefits derived from using land include the right to transfer user rights, collect rent from houses built and sell or consume crops grown. Land access can therefore refer to a context where land is available and affordable for users/seekers; who have security of tenure and can therefore make land transactions without obstacles (Quan Citation2006; Moyo Citation2017). The definition adopted is relevant since the paper explores land-access systems through the perspectives of actors. Hence, the means and processes contribute to the nature of land-access systems.

In most developing countries, land access in peri-urban areas is characterised by complex arrangements of land governance systems (Kombe Citation2005; Adam Citation2014; Follmann et al. Citation2018). This is largely attributed to the co-existence of formal and informal systems of accessing land; which may operate independently or simultaneously within the same locality. The informal system is however more popular than the formal. Scholars (Msangi Citation2011, Citation2014; Durand-Lasserve et al. Citation2012; Adam Citation2014) resonate that consequently, because of the popularity of informal procedures, most of the developing countries experience insufficient supply of serviced land and volatile land markets resulting into unplanned and unstructured city growths in peri-urban areas.

The existing dual system is driven by different actors with varying powers, authorities, interests and resources (Lutzoni Citation2016; Nuhu Citation2018). These actors sometimes operate in a network and may have relationships amongst themselves in line with converging interests (Nuhu Citation2018). They may engage in different and sometimes similar land-access systems, in coordination or independently. Thus, actors may have contrasting or comparable perceptions towards the existing land-access systems in peri-urban areas (Kironde Citation2009). There is consensus among scholars that the formal land-access system is systematic and procedural (Masanja Citation2003; Kironde Citation2009; Msangi Citation2014; Nuhu Citation2018). Land seekers and land service providers are in tandem about the complexity in the system. However, this cannot be generalised because there are sporadic events and informalities within the formal system (Kombe and Kreibich Citation2006). Masanja (Citation2003) notes that land-use conflicts and violation of rights are common in areas with dynamic land-use changes. This may lead to conflicts between customary and formal land tenure in the transition phase and portrays the connection between land disputes and tenure security. These perceptions are based on the actors’ motives for accessing land, the process applied, benefits achieved or challenges encountered. However, these have not been addressed appropriately in the literature (see Lupala Citation2008; Kayera Citation2011; Msangi Citation2011, Citation2014; Adam Citation2014; Nuhu Citation2018) to generate information for the land sector.

The aim of this paper was therefore built upon Nuhu’s (Citation2018) recommendation that actors’ perceptions towards the existing land-access systems in peri-urban areas ought to be explored. Exploring the actors’ perspectives contributes to improving peri-urban land governance. The topic under investigation has attracted local and global debates because land access is a fundamental component for development.

This paper is organised as follows; Section 1 provides background information of the study. Section 2 outlines the land tenure systems in Tanzania. Section 3 presents the theoretical understanding focusing on the main concepts used in the paper. Section 4 explains the methodological approach employed. Section 5 presents and discusses the findings reflecting on the actors’ perceptions towards the existing land-access systems. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Land tenure system in Tanzania

In Tanzania, statutory, customary and informal land tenure systems exist. Statutory land tenure system is reflected in two forms: on land granted by the state in planned and surveyed areas or lease hold between 33 and 99 years provided by the state (URT Citation1999; Moyo Citation2017). Under the leasehold, the duration of lease can be revoked before the expiry period if the leaseholder does not abide by the terms and conditions or if the state (grantor) deems it fit to revoke the agreement in the interest of the public (URT Citation1999, Citation2007a; Kombe and Kreibich Citation2001; Kironde Citation2009). Customary land tenure system refers to land occupied by the traditional communities, or clans, or families as a whole, and in perpetuity (Moyo Citation2017). Its use and access is guided and bound by shared customary values and norms which vary from one society to another. Although customary laws are not documented or coded, the state provides legal jurisdiction over customary rights (URT Citation1999, Citation2007a). Informal land tenure system manifests when willing sellers and buyers engage in land transactions outside the government procedures and it operates through individuals’ decisions and actions (Kombe and Kreibich Citation2001; Nuhu Citation2018). The parties may or may not possess any binding documentation, while others may illegally invade vacant land (Massoi and Norman Citation2010; Rasmussen Citation2013; Kironde Citation2016). In this case, such occupiers will be considered squatters.

Different land tenure systems may be prevalent in same geographical location; however, there may be a degree of dominance of a particular tenure system in a specific locality. Statutory land tenure system for instance, is dominant in the urban areas, while customary land tenure is popular in rural areas and to some extent in peri-urban areas. Informal land tenure system is predominant in peri-urban areas (Kombe and Kreibich Citation2001; Masanja Citation2003; Nuhu Citation2018). In order to address informality in the land sector in Tanzania, the government has taken several initiatives. These include formalisation and regularisation of informal land, encouraging participation of the private sector as well as embracing public–private partnerships in land-access services (Kasala and Bura Citation2016). Some cases of informal land tenure system have characteristics of customary land tenure system; for instance, an individual can purchase land informally but then pass it on, to the next generation. Therefore, the person whom the land has been given is considered to have inherited it. In this context, it is argued that customary land may have an informality component and vice versa. Land tenure system and land-access system thus, cannot be discussed in isolation.

Land tenure system determines the land-access process. Formal land-access system operates adequately in areas where statutory land tenure system is prevalent, while informal land-access system is exclusively applicable in the informal and customary land tenure systems. Obnoxiously, informal processes of accessing land may also occur in the planned and surveyed areas when government officers ignore official procedures, often for private gains (Masanja Citation2003; Briggs Citation2011; Nuhu and Mpambije Citation2017). This is a reflection of the informal process operating in an environment of statutory tenure system. Under the formal process, people access land in the planned areas and acquire title deeds recognised by the government (Kironde Citation2009, Citation2015). While the formal system is supported by the existing policies, the informal is equally facilitated by the institutional framework at the local level (Kombe and Kreibich Citation2001, Citation2006). Implementation of both systems involves various grass root actors and institutions.

3. Theoretical underpinnings: peri-urban land, actors and institutions

There is no universal meaning of ‘peri-urban land’ (Rauws & Roo Citation2011; Adam Citation2014). Scholars provide definitions which differ in terms of locality, culture, discipline and the purposes of the topic/study (Kanji et al. Citation2005; Simon and Adam-Bradford Citation2016). Adam (Citation2014) noted that most definitions from the social sciences perspective, focus more on the function of land, its geographical location and legal perspective. Regarding its function, Laquinta and Drescher (Citation2000) point out that peri-urban land is that land which has been dominated by mixed activities; agriculture and settlements. It is also a landscape that has emerged from rural and urban sprawl (Rauws and de Roo Citation2011). Focusing on the legal perspective, Shaw (Citation2005) indicates that peri-urban land is an area that lies ‘outside the legal jurisdiction of the city and sometimes, even outside the legal jurisdiction of any urban local body’. In relation to this, the Tanzania Land Act of 1999 indicates that peri-urban land is within ‘..a radius of ten kilometers out-side the boundaries of an urban or semi built up area, or within any large radius which may be prescribed in respect of any particular urban area by the Minister’ (URT Citation1999, p. 12). This is a temporal criteria that will change overtime as an urban area grows. Peri-urban land attracts a number of actors within the informal as well as formal systems.

Actors include individuals, groups, associations or organisations. These should be able to exhibit capacity to make and undertake decisions. They may be unorganised, organised, coordinated or not (Hermans Citation2005). According to Wasserman and Faust (Citation1994), actors may operate in a network linked with common goals. This link is a strong bond among actors which creates a relation amongst them. A relationship among actors is determined by perceptions, objectives and resources which influence their actions. Hermans (Citation2005) notes that perceptions are the imaginations or ideological visions of the action and its consequences in relation to policy, networks and characteristics. Objectives show the road map for actors towards solving a certain problem to achieve desired goals (Hermans Citation2005; Hermans and Cunningham Citation2018). Resources are the enabling means for actors to achieve their goal and these may include financial, non-financial, or both for example position in a network. Resources determine the power of actors to influence decisions in a network (Ratajczak-Mrozek and Herbec Citation2013). Therefore, resources relate to power implying that the power of actors determine the capacity to control resources. Hermans (Citation2005) contends that objectives influenced by perceptions and enabled by resources results into actions. Any actions taken by an actor whether insignificant or not, affects other actors in a network. Actors’ actions are determined by institutions and sometimes actors can also influence institutions.

The concept of institution has been defined depending on the individual’s discipline, cultural background and political leaning (Castellano and García-Quero Citation2012; Ashu Citation2016). North (Citation1990, p. 3) from the economic discipline defines institutions as ‘…the rules of the game in society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction. In consequence, they structure incentives in human exchange, whether political, social, or economic…’ According to Jepperson (Citation1991, p. 149) from a sociological perspective, institution is a ‘socially constructed, routine-reproduced (ceteris paribus), programme or rules systems. They operate as relative fixtures of constraining environments and are compared by take-for-granted accounts’. Both North and Jepperson are in tandem over social influence and the constraints that shape or determine the interaction of actors.

North (Citation1990) clarifies that institutions can be divided into two sets: the formal and informal set of arrangements. Formal institutions are formal rules and procedures that determine political decision making (Cao Citation2012; McMcloskey Citation2016). The aim of formal institutions is to enhance good governance and efficiency of the public sector, as well as to protect private property rights from misappropriation by private parties or government. Informal institutions can be understood as socially shared rules and norms that structure and determine social interaction and behaviour of actors (Voigt Citation2013). The role of informal institutions is to operate where there is no formal system, or supplement the existing formal institutions in peri-urban areas. This is more applicable in areas exhibiting rapidly changing socio-economic activities, urban growth and high land transactions as noted by Schroder and Waibel (Citation2012). In accessing peri-urban land, actors and institutions are not isolated and land is central in this web.

In this paper, understanding peri-urban land is significant because of its contentiousness and vulnerability to the pull and push forces from both rural and urban areas due to location and multifunction (Kanji et al. Citation2005; Olajuyigbe Citation2016; Wandl and Magoni Citation2017). This is fuelled by rapid urban expansion and population growth (Wandl and Magoni Citation2017; Rahayu and Mardiansjah Citation2018). According to Kanji et al. (Citation2005) competition over land in these areas is high. Therefore, the peri-urban land which would be used for agriculture and other activities is transformed into setting-up buildings and other socio-economic activities (Wandl and Magoni Citation2017). The transformation is also rapid due to the emergence and increase of the number of formal and informal actors with interest in peri-urban land (Kanji et al. Citation2005; Adam Citation2014). In achieving their demands, these actors sometimes have an impact on peri-urban land development which particularly affects the peri-urban poor (Adam Citation2014; Wandl and Magoni Citation2017). Ultimately, peri-urban areas experience high rates of clashes between institutions and actors with different interests than urban and rural areas (Adam Citation2014). Hence, North (Citation1990) cautions that institutions must be differentiated from players or actors. In justification, Ashu (Citation2016) notes that interactions between institutions and players or actors may shape and determine the evolution in access to public services such as land.

4. Methodology

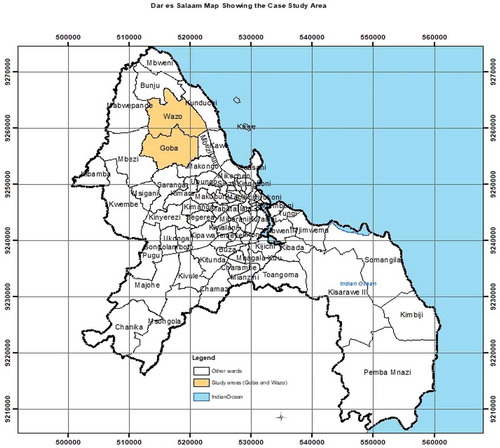

This paper applies a case study strategy by analysing actors’ perspectives towards the prevalent dual system of accessing land in peri-urban areas in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The strategy was adopted because actors’ interests are divergent and thus contribute to complexities in land-access governance. The peri-urban area of Dar es Salaam was selected purposively because of rapid urbanisation with limited transformation and dynamic demographic transition, leading to high competition over access to land among actors. Two wards (Goba and Wazo) as indicated in were selected from the peri-urban area of Dar es Salaam based on the following criteria; (i) areas with vibrant land transactions and parcelling; (ii) areas with high activities of land transformations; (iii) areas with pre-dominance informal system of accessing land. The criteria was significant in enabling access to multiple actors within a dynamic community and therefore perspectives of actors would enrich the argument of the study.

Mixed methods involving both qualitative and quantitative methodological approaches were applied using in-depth interviews, household questionnaire and document analysis. Twenty semi-structured interviews were held with key actors selected from Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), private and public sector as well as brokers. These were purposively selected based on activities of the company/organisation, experiences in land matters and responsibilities in their respective offices. Participants from CSOs, private and public sectors were identified by the administrative personnel in the respective organisation taking into account participants’ roles in land matters. The recommended staff were interviewed from their areas of operation at their convenience and as per proposed schedules. Brokers were identified from their areas of socialisation or business centres locally known as ‘Kijiweni’Footnote1. That is also an area where one get information on various aspects including land/house for sell and rent. Other brokers were identified from their address (telephone) contacts displayed on the roadside notices advertising their services. Interviews were conducted as scheduled by the participants. Nine (9) sitting land occupiers also participated in the interviews based on the size of their plots. Local community leaders were pivotal in identifying these participants based on the size of plots. Two categories were considered: those with small plots and those with big plot sizes. The idea was to uncover the variances in how these plots were accessed and the actors involved. Land occupiers (participants) were interviewed at their places of residence. The questions posed during interviews were explorative in manner in order to identify the type of system actors’ were utilising, challenges and opportunities embedded therein.

Ninety sitting land occupiers were selected whom the researcher administered the questionnaire; in order to get a wider picture on the informal land-access system in the study area. The questionnaire was needed as there is no documentation that describes this process of accessing land. Purposive and simple random sampling were used to select these respondents. The sampling frame purposefully focused on respondents who had accessed land informally, whom local leaders assisted in identifying. This is because the informal land-access system is more dynamic, popular and pre-dominant in the peri-urban areas. It also cuts across all social classes (rich, middle and high income) and drives peri-urban transformation. This is in contrast with the formal system which is state controlled and with procedures. Additionally, documents were analysed in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding and develop knowledge regarding procedures and steps provided in the formal land-access system. Documents analysed included: the National Land Policy of 1995, Land Act of 1999, Urban Land Planning Act of 2007 and Land Use Planning Act of 2007 (URT Citation1995; URT Citation1999; URT Citation2007a; Citation2007b). Content analysis was done in accordance with emerging themes from interviews and reviewed documents. Emerged themes are explained and discussed in Section 5.

5. Findings and discussion

5.1. Peri-urban land access: existing systems and main actors

As discussed in Section 1, in Tanzania, the formal and informal systems are used by actors in the process of accessing land, sometimes concurrently and in other times independently. Formal land-access system mostly predominates in the urban planned areas, while the informal has become the de-facto in peri-urban unplanned areas (Msangi Citation2011, Citation2014). Actors’ decision-making and behaviour are determined under the two systems in land-access processes (Adam Citation2014). In this study, an attempt to understand key actors and their participation in both formal and informal systems that guide access to land in peri-urban areas of Dar es Salaam is made.

Understanding the informal land-access processes that prevail and operate in peri-urban areas in Dar es Salaam cannot be clearly explained without discussing the existing formal system. Formal land-access system in Tanzania is governed by various laws and procedures emanating from the colonial era (DILAPS Citation2006). These have been undergoing changes influenced by socio-economic and political factors. Prior to the colonial era, land access in the country was informed and shaped by customary laws and regulations (Boone Citation2015). Under customary setting, access to land was through inheritance given by a friend or clan leader (Holden and Otsuka Citation2014; Boone Citation2015). However, from the colonial time and after independence (1963 onwards), a shift of ‘power centres’ was experienced where authority to allocate land (give one access) started to shift from the chiefs and clan elders to elected village councils (Massoi and Norman Citation2010). During the colonial time, various formal decrees and legislations were established to guide land access and administration. The German imperial decrees for instance, shifted all land to the empire, except that, which was under private ownership or owned by chiefs or communities. The Land Ordinary Cap. 133 established by the British declared all land as public, whether occupied or not (DILAPS Citation2006). The entire colonial land-access system was basically individualistic, alienating and racial discriminating.

Findings indicate that after independence, Tanzania started to introduce various policies and laws. Land for example is still regarded public property; vested in the president as a trustee on behalf of all citizens (for example URT Citation1967, Citation1977, Citation1999, Citation2007a). Access to formal land is under two fold; (i) procuring a certificate of occupancy from the municipal land office; (ii) initially accessing land informally and then later complying with the formal process to get a title deed. The main key actors mandated to fulfil the aforementioned processes include: Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development (MLHHSD), Local Government Authorities (LGAs), Private sector, CSOs and local communities. The role of the MLHHSD include; initiation of planning and surveying projects, declaration of planned areas, regulation of land use, approval of land-use planning and change. It also offers certificates of occupancy and settles land-use conflicts (Msale-Kweka Citation2017; Nuhu Citation2018). The power of the Ministry in formal land-access processes is mandated by the Tanzania constitution of 1977 and supported by various policies and laws, for instance, the National Land Policy of 1995 and Land Act of 1999. LGA is a planning government arm according to the Land Act of 1999 and Urban Planning Act of 2007 (URT Citation1999, Citation2007a). The authority has been mandated to prepare land-planning projects, implement and coordinate land-use planning in areas of jurisdiction.

The MLHHSD and LGAs are supported by other government agencies such as the National Land Use Planning Commission (NLUPC), professional registration boards and utility agencies. The NLUPC and professional registration boards are instructed to promote good governance in land-access processes by promoting effective land use, standards, practice and discipline, while the utility agencies provide basic services in the planned areas (Kironde Citation2009; Nuhu Citation2018). Findings reveal that local leaders represent government and its agencies at the grass roots in the formal land-access processes. Local leaders include political and appointed leaders (civil servants) within an area at the sub-ward and ward levels that are administration units at grass roots level. Local leaders may among other things, disseminate information about the availability of land for sale in their areas, facilitate land transactions as well as solve land disputes. The private sector through public–private partnership facilitates formalisation of informally accessed land and they initiate formal land-access projects, in collaboration with LGAs. This enables the land occupiers to get title deeds within reasonable period. CSOs advocate for land-access rights of persons whose rights have been denied, abused or violated either in the formal or informal system. Local communities (land buyers and sellers) are the beneficiaries of the formal land processes. Actors in the formal land-access system may also participate in the informal system.

Informal land-access system in Tanzania prevails in areas where land is not professionally planned, surveyed or demarcated (Kombe Citation2005; Kironde Citation2009; Msangi Citation2011, Citation2014). Land under this system is made available in the market by informal actors such as private individuals including sellers, brokers, community members’ as well as the local leaders. In this capacity, save for the brokers, the rest of the actors can act as temporary agents connecting sellers to buyers or vice versa. Hence, an agent plays the role of a broker at a particular time and may get a commission for the services. A community in the peri-urban area comprises of members within the same geographical location and under the same local leadership. Some community members may hold land rights, while others may be tenants. Occasionally, community members may facilitate land transactions since they know most of the land sellers and if requested by land seekers they may identify land available for sale. In this dynamism, one may be a land buyer at a particular time and a land seller at another time depending on one’s intentions and interests. Hence, access to land is open to all as long as one can afford the costs. Actors neither have legal mandate to provide or responsibility to deliver plots nor power to enforce land development standards (Lupala Citation2008; Nuhu Citation2018). Land sellers may commodify land and divide one piece after another as need for cash arises. They may also sell their land through various actors and processes. One of the respondents with a big piece of land confirmed:

…I was lucky that I got a big piece of land at a time when land was still cheap in this area. These days I have started parcelling this plot and selling to get money to build my dream house. Local leaders and some brokers have been referring potential buyers to me.

Land buyers on the other hand, have different land needs depending on their economic status and activity for example building or speculation. They may access land through different channels and this may vary from one buyer to another.

Findings indicate that other key actors in the informal land-access system are brokers; who are the middle men between sellers and buyers. Brokers derive their livelihood from facilitating land transactions by connecting interested parties (Wolff et al. Citation2018). Brokering is a service offered and a business that one chooses to engage in to earn a living. Sometimes, brokers engage in price negotiations in order to meet the buyers’ affordable prices (Adam Citation2014; Nelson Citation2018). The sellers can also contact the brokers when they want to sell their land. Brokers’ in the study area use different means to advertise plots for sale such as putting up informal posters near the road. They also use social platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Blogs, WhatsApp and other applications to advertise plots for sale. This is commensurate with the findings from other studies that social networks of friends, workmates and neighbours were instrumental in enabling land seekers to access plots informally (Lupala Citation2008; Kihato and Royston Citation2013). Community members act as watchdogs of one another over their plots of land in the area. They notify each other in case of trespasses or land invasion. It should be noted that local leaders participate in both formal and informal land-access systems. In the informal land processes, local leaders participate at ward and sub-ward levels facilitating land transactions between buyers and sellers. In witness of these leaders, sellers transfer transaction agreement documents to buyers. Findings reveal that both buyers and sellers pay some amount of money (normally 10 per cent) to the local leaders’ office for their services in the land transacted. One of the land occupiers revealed:

When I sold my two plots, I had to pay five percent of the total amount that I received from the buyer to the local MtaaFootnote2 office. The person whom I had sold the land also paid the same amount to the same office. This money may seem to be a lot but it is inadequate considering the challenges local leaders encounter and activities performed while offering leadership in the community.

In the informal processes, there are no specific classes of actors with specific responsibilities but rather people who participate on a case-to-case basis (Kayera Citation2011; Holden and Otsuka Citation2014). The chain of selling and buying is not systematic; sometimes land occupants can sell their plots on their own or use brokers. Buyers on the other hand can either use brokers, local leaders, friends or relatives to search for plots. The land-sitting occupiers were asked to identify the informal modes or ways they applied to access land in order to understand how the informal land-access system operates. Out of 90 respondents, 85 per cent of land occupiers had purchased plots from peri-urban land holders and 6 per cent had inherited land with no documentation. The findings also show that 5 per cent had invaded vacant land, 2 per cent were given land as a gift from friends, relatives or family members, while 2 per cent were allocated land by political or government leaders.

The different ways applied by peri-urban dwellers to access land informally indicate that despite land being vested in the president in Tanzania, the majority of peri-urban land occupiers have been purchasing or inheriting land from private land holders. It is also noted that the government officials seeking political influence or otherwise, allocate land to people informally especially in undeveloped areas or newly occupied areas. The allocation of land informally by government actors also happens especially when people are evicted from the urban centres due to various environmental hazards and land-use conflicts. It is complex to alienate formal from informal processes, nor is it feasible to put a yardstick from either of the processes to another. As it is paradoxical to differentiate between systems, so is it with actors’ participation. It is difficult to comprehend in which system an actor is passive or submissive in situations where actors are engaged in the land-access dual systems. Therefore, understanding the actors’ perceptions towards the formal and informal land-access systems gives an insight into their interest that drive them to participate in either or both systems.

5.2. Actors’ perspectives regarding land-access systems in peri-urban areas

The paper provides challenges and opportunities of both formal and informal land-access systems based on the actors perceptions and experiences as was revealed during the study. Justifications for the actors’ perspectives for a particular system is also explored. The perspectives have been divided into categories which include simplicity and complexity, land tenure security, land-use disputes and emergency services delivery responses.

5.2.1. Simplicity and complexity

Actors’ views were extracted through contrasting and comparing the simplicity and complexity of land-access systems in terms of financial implications, bureaucracy and time. It was noted that the formal land-access system was time consuming and expensive because of complex and bureaucratic procedures. These procedures are in accordance with stipulated land policies and guidelines such as the Land Act of 1999 and Urban Planning Act of 2007. This is in agreement with the study by Nuhu and Mpambije (Citation2017) which noted that the formal land-access procedures were too many and discouraging. The procedures include letter for application, preparation and approval of town planning layout, request for survey, deed processing and title application. The key procedures are executed in different offices or sometimes locations. Land title applicants visit the Municipal land office where the Municipal surveyor and town planner services are sought. The applicants’ surveyed plots and proposed plans are submitted to the MLHHSD for approval. The approval process passes through different offices in MLHHSD such as Director for Human Settlements, Director of Surveying and Mapping and Commissioner for Lands. Zonal offices were introduced to decentralise land administration and reduce on backlog in the delivery of land administration services at the Ministry. However, these offices have not been able to adequately perform their roles and activities as anticipated because of limited financial and human resources. Zonal offices are at present operating outside the legal framework since policies regarding decentralisation of land administration are still being revised (URT Citation2015). Therefore, MLHHSD is still burdened by the backlog of land activities.

Fulfilling the formal process requires the applicant to invest in time and money since follow up may take a long period to get the title eventually. Hence, the procedures are rigid and not pro-poor. These procedures also affect the facilitators (private sector) in land services. In an interview with officials from the private sector, it was revealed that a firm passes through 7 steps to accomplish the delivering of planning and land surveying services under formal procedures. Notably, it takes one to four months for documents to be handled in one office (Lugoe Citation2008). This creates lack of trust between communities/clients and the private land service providers who might be oblivious about the procedures. The official interviewed from the private firm lamented:

…it is a hectic process to acquire a permit from LGA…it normally takes a long period of time which demoralises our clients. Sometimes, clients think that our services are not effective and this creates misunderstandings between our clients and our firm as services providers.

The possibility of lack of consultation between offices and departments for decisions making is also a common occurrence. This was a concern from one of the officials from the private firms that the MLHHSD has relatively more autonomy and less consultation with other actors. Whereas, most actors complained about procedures in the formal land-access system, the discussion with officials from MLHHSD and LGAs reveals contrary perceptions. Government officials argued that the procedures were meant for checks and balances in the land sector and that citizens who were not comfortable with the system had dubious intentions. Although officials from government were defensive, the reality in the implementation of these procedures leaves a lot to be desired.

The failure of the formal system to meet the land needs of some land seekers gives rise to the application of the informal land-access system. Accessing land informally differs from one case to another, although the actors involved determine the speed of land transactions (Adam Citation2014). Discussion with brokers, land occupiers and local leaders revealed that buyers and sellers may interact without agents, but proceed to use the services of a lawyer or local leader to complete their transactions. In other instances, the agent seeks out for buyers and sellers and proceeds to the local leaders or lawyers for certifying the land transfer. Another scenario is where buyers and sellers based on trust, conclude the land transfer process without third party actors to witness or endorse their transaction. Local leaders revealed that some land seekers in other cases express their need to access land in the areas through their offices. In this case, local leaders act as middlemen or brokers since they have information on who among their local residents is selling land (Jimu Citation2012). The brokers’ revealed that their main responsibility was to share information about the availability of plots in certain areas to prospective land seekers. They also link land seekers to land sellers. In these dealings, brokers are engaged in bargaining and negotiating land prices. This saves land seekers and buyers’ time and money. It is thus easy to access land informally depending on the willingness of the buyers, sellers and inter mediate person.

Findings indicate that, it is possible for land seekers to finish a transaction even within a day. Land seekers have the opportunity to visit many plots and choose the best depending on their need. The middlemen (brokers) and local leaders because of money, they invest their time to make sure land seekers get as many choices of plots as possible to make a decision. Money can even be paid in instalments depending on the agreement between the sellers and buyers. In an interview with one landholder, it was realised that it had taken him more than half a year to complete payment of his plot. Under the informal process, land purchasing is not only by cash but also in form of material exchange. Respondents revealed that some land occupiers acquired products and groceries from the shops within the community on credit and failed to pay back. Consequently, they gave up part of their land/plots to the shop owner to settle the debt. In regard to the views from land-sitting occupiers, the informal system was less bureaucratic, swift and time saving. It was however noted that bureaucracy is reduced by the network established between brokers and land seekers or sellers.

5.2.2. Land tenure security

It is acknowledged by all actors that the formal land-access system enables residents to attain security of tenure over their land because of the legal documentation of holding. They can even use their land for development since they have a guarantee of not to be evicted or invaded. This has been justified by other scholars. Security of tenure is an important factor for individual development and community in general (Kayera Citation2011; Van der Molen Citation2017). Plots accessed formally have legal protection and can be used as a guarantee on economic issues such as borrowing money from the bank (Gilbert Citation2012; Sheuya & Bura Citation2016). Hernando De Soto’s in his book The Mystery of Capital, notes that, security of tenure is a livelihood asset for the poor (De Soto Citation2000; Varley Citation2002; Sjaastad and Cousins Citation2009). In view of this, Tanzania encouraged its citizens in peri-urban areas to formalise their plots in order to use them as collateral. In an interview with one landholder of seven hectares, this revelation was made:

…I am in the process of formalising my land because I want to borrow money from the bank and start a small business since I am a retired civil servant. I have many hectares of land which I will divide into small plots and sell a few of them at high prices after the formalisation process to get more money for my business.

This reveals that plots that have been formalised gain more market value than those not formalised and thus, they are more economically viable for redevelopment or sell.

On the contrary, the informal land-access system has been built on social trust within a community (Kombe Citation2005; Lupala Citation2008). Most people do not have any kind of ownership evidence. This is more evident among people who access land through inheritance. During the process, informal actors tend to trust each other even within a short period of time in the process of land transaction. This was observed in the sub-ward leader’s office where sometimes sellers and buyers come to ward and sub-ward office but do not have anyone to witness their land transaction. Findings reveal that even those people who do not have any document to prove holding of plots, their status as occupiers is recognised by their neighbours, friends and local leaders. In this regard, the role of private firms in providing land services and the need for formalisation of plots becomes irrelevant. The trust in the informal area also ensures securing plot boundaries where community members’ report to owners in the event that neighbouring plots have been invaded or encroached upon by other people. This gives them some sense of security of tenure as one landholder narrated:

I do not have any kind of document to prove that this plot is mine. But all my neighbors are aware that I am the owner of this plot. By the time I purchased this plot, my neighbors were already residing here and therefore, they can defend me in case anyone encroached on my land.

Although there seems to be security of tenure based on trust, this may be unreliable in certain cases. This may happen when familiar neighbours or witnesses shift to other areas since there is no documentation. Therefore, in the case of threatened land tenure, the occupier may fail to get defendants. During the interview with some of the land occupiers, it was revealed that they had no contacts of the people present at the time they purchased their land.

The discussion reveals that there is security of tenure under the formal system than the informal. It is also noted that the formal system can empower the poor to access financial services. Gilbert (Citation2012) emphasises that one’s property is insecure without a legal title and this discourages investment since selling or transferring to generations may not be easy.

5.2.3. Land-use disputes

It was noted that there are relatively few cases of land disputes emanating from the formal land-access system compared to informal. This is attributed to clear plot demarcations and documentation of land occupancy as attested by local leaders; who normally engage in solving such disputes in their spheres of influence. In another perspective, it was admitted that the formal system enables government to acquire land for public use. Findings also show that payment of compensation for land which is surveyed and planned is relatively fast compared to unplanned areas (see Msangi Citation2014; Sheuya and Burra Citation2016; Gwaleba and Masum Citation2018). In the views of local leaders, it is easy to deal with cases related to plots with formal documents to those accessed informally. Unlike land accessed formally, land acquired through the informal system is marred with disputes. These include double sell, land invasions, encroachments, and trespasses arising from unclear boundaries, lack of demarcation between plots and poor documentation. This was confirmed by one of the respondents tussling out his plot boundaries:

…when I bought my plot, we did not put permanent demarcations and over time the boundaries of the plot could not easily be identified…my neighbours have been selling off their pieces of land after another and the new occupiers have encroached upon my plot which I noticed as the size of it decreased and reported to the sub-ward chairman.

The disputes were also associated with the presence of many channels of selling and buying plots which are driven by uncoordinated informal actors especially brokers.

Notably, land sellers and buyers are not obliged to use the clear channels in land transactions (Kayera Citation2011; Adam Citation2014). It was lamented that brokers and sellers have contributed to disputes because of lack of work ethics and integrity. False information in documents of evidence was also revealed as another source of land disputes. These disputes were revealed by local leaders since they are the ones who mitigate between disputing parties in their areas of influence. Representatives from CSOs concurred with local leaders on these disputes since they are seldom consulted to advocate for the rights of the most vulnerable groups to land rights abuses. It is challenging to settle disputes in informally accessed land as the local leaders testified. They narrated that sometimes their office received cases related to invasion of other plots but when the complainant would be requested to provide evidence of holding occupancy rights, it would not be available. At the same time, the trespassers present unknown documentation in the respective areas. Although social recognition is mentioned as applicable in informal systems, reflecting on the increasing pressure, densities and changing economic patterns, documented evidence is a substantial necessity. It is apparent from the perspectives of actors that land disputes are predominant in informally accessed land. This affirms Kombe’s study of 2010 that the disputes are intensified in informal land-access system. The findings that land disputes were pre-dominant in the informal areas is not surprising since the study areas was in peri-urban areas where informal land-access system is popular. Therefore, one cannot conclude that there are few cases in the formal land-access system in this particular area.

5.2.4. Emergency services delivery response

The actors’ views also align to the emergency issues, for example, catastrophes that challenge the success of both land-access systems. However, findings reveal that under the formal system, there are guidelines for taking environmental risk precautions. According to the urban planning regulations, the areas should have a wide space for physical infrastructure with demarcated size (see and ). This creates suitable conditions for responding to disaster risks such as fire outbreaks compared to the unplanned areas (Kayera Citation2011; Mushumbusi Citation2011). In the planned areas, there is demarcated space between plots and therefore, it is easy for emergency services such as ambulance and fire brigade to reach the intended destination. This was also attested by one of the land officials from the municipality:

…people residing in planned areas are very lucky and privileged. In case of any medical emergency, they can easily be located from their residence and taken to health centers to save their life in time..that is why it is important for people to ensure that they buy plots in such areas if they can afford.

Table 1. Space and planning standards for residential areas.

Table 2. Space and planning standards for infrastructure in planned areas.

The realisation of benefits associated with living in planned areas has influenced the government to encourage and support the private sector to facilitate the formalisation of the informally accessed land. In areas where land has been accessed formally, residents easily get emergency response to disasters because the infrastructure is well developed to enable rescuers access to such areas. That is why even private firms that are engaged in providing planning and surveying services to the informally accessed land, are taking precaution of ensuring that the areas have at least good infrastructure (Kasala and Burra Citation2016). In an interview with an official from one of the private firms, it was revealed that firms have directives to ensure that areas that they plan and survey have street roads.

…we try to facilitate peri-urban dwellers to live in planned and surveyed areas. We are even providing land planning and surveying services to predominant informal areas. This will enable effective response to disasters or emergencies in these areas as well.

This response indicates that the private sector is keenly implementing government directives in ensuring that each plot is accessible. If this is not possible, those plots which have accessibility challenge can be grouped to form blocks in order to simplify the accessibility of street roads.

Some of the residents interviewed in areas of informally accessed land concurred that the main challenge they were facing was poor infrastructure development within their areas, which hinders easy accessibility. Thus, it is clear that emergency delivery responses in the two areas differ due to variances in accessibility.

6. Conclusion

Perspectives from the actors cutting across the processes, outcomes and impact indicate that both formal and informal land-access systems have inadequacies and benefits. The complexity of the formal land-access system is fuelled by procedural and policy underpinnings, while the simplicity of the informal land system emanates from the interaction of actors in a free environment. The inadequacies in one system contribute to the strengths of the other. Although the informal land-access system is marred with multiple challenges compared to the formal, it remains the predominant land-access system in peri-urban areas. Participation of actors in both systems is evident and therefore the dynamics in the land-access governance are apparent. The challenges emanating from the interaction of actors are influenced by the existing systems. It is therefore important that the government facilitate collaborative mechanisms between the two systems and actors involved in land access in peri-urban areas. This could be done through public–private partnership which may promote participatory decision-making and establishment of actors’ platforms for experience sharing and lesson learning. It is important that the informal system is supported in order to improve its performance including addressing the inherent challenges such as lack of a regulating system. There is need also for participatory institutional and policy reforms to improve the formal land-access system so as to address and support access to land by the majority poor, most of whom opt for the informal sector. The perspective of actors may not be generalised; it is therefore recommended that further studies should be conducted to identify specific challenge faced by key actors’ such as private firms.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without guidance from my senior colleagues in the thematic discipline as well as financial support from SIDA-SAREC.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Said Nuhu

Said Nuhu is currently a PhD candidate at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Sweden) and Ardhi University (Tanzania) under the double degree program. He holds a Master of Arts Degree in Development Studies and a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Geography and Environmental Studies. He works at the Institute of Human Settlement Studies of Ardhi University as an Assistant Research Fellow. He has published articles related to urban land governance and management, water resources management in urban areas and corruption in the land sector.

Notes

1. Kijiweni/Vijiweni is/are small open areas, informal areas, often under a tree or informal kiosk.

2. Mtaa or sub-ward is a small local unit of administration in Tanzania. It is headed by appointed (salaried) and elected leaders.

References

- Adam GA. 2014. Peri-Urban Land Tenure in Ethiopia [ Doctoral dissertation]. Stockholm: KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

- Ashu STN 2016. The impacts of formal and informal institutions on a forest management project in Cameroon [ Master’s thesis]. Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Boone C. 2015. Land tenure regimes and state structure in rural Africa: implications for forms of resistance to large-scale land acquisitions by outsiders. J Contemp Afri Stud. 33(2):171–190.

- Briggs J. 2011. The land formalisation process and the peri-urban zone of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Plann Theory Prac. 12(1):115–153.

- Cao L. 2012. Informal institutions and property rights. Facult Publications. Paper 1427. Williamsburg: College of William & Marry Law School.

- Castellano FL, García-Quero F. 2012. Institutional approaches to economic development: the current status of the debate. J Econ Issues. 46(4):921–940.

- De Soto H. 2000. The mystery of capital. Why capitalism succeeds in the west and fails everywhere else. New York: Basic Books.

- DILAPS. 2006. Land administration and customary tenure dynamics in post-independence mainland Tanzania. Review Paper No. 6. Dar es Salaam (Tanzania): Dar es Salaam Institute for Land Administration and Policy Studies.

- Durand-Lasserve A, Selod H. 2012. Land markets and land delivery systems in rapidly expanding West African cities. The case of Bamako. In: Sixth Urban Research and Knowledge Symposium. Spain: Barcelona.

- Follmann A, Hartmann G, Dannenberg P. 2018. Multi-temporal transect analysis of peri-urban developments in Faridabad, India. J Maps. 14(1):17–25.

- Gilbert A. 2012. View point. De Soto’s the mystery of capital: Reflections on the book’s public impact. Int Develop Plann Rev. 34:4–18.

- Gwaleba MJ, Masum F. 2018. Participation of informal settlers in participatory land use planning project in pursuit of tenure security. Urban Forum. 29(89):169–184.

- Hermans L. 2005. Actor analysis for water resources management: putting the promise into practice. The Nerthelands: Eburon Uitgeverij BV.

- Hermans LM, Cunningham SW. 2018. Actor and strategy models: practical applications and step-wise approaches. New Jersey. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Holden ST, Otsuka K. 2014. The roles of land tenure reforms and land markets in the context of population growth and land use intensification in Africa. Food Policy. 48:88–97.

- Jepperson RJ. 1991. Institutions institutional effects and institutionalization. In: Powell WW, DiMaggio PJ, editors. The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 143–163.

- Jimu IM. 2012. Peri-urban land transactions: everyday practices and relations in peri-urban Blantyre, Malawi. Mankon (Bamanda): Langaa Research and Publishing CIG.

- Kanji N, Cotula L, Hilhorst T, Toulmin C, Witten W. 2005. Can land registration serve poor and marginalized groups? Summary report; securing land rights in Africa. Research Report I. pp. 3–4.

- Kasala SE, Burra MM. 2016. The role of public private partnerships in planned and serviced land delivery in Tanzania. iBusiness. 8:10–17.

- Kayera JH. 2011. Land Delivery for Housing Development in Dar es Salaam Tanzania: Comparative Study of Formal and Informal Mechanisms at Kinyerezi [ Masters Thesis]. Stockholm (Sweden): KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

- Kihato CW, Royston L. 2013. Rethinking emerging land markets in rapidly growing Southern African cities. Urban Forum. 24(1):1–9.

- Kironde JL. 2009. improving land sector governance in africa: the case of Tanzania. Paper presented at the Workshop on “Land Governance in support of the MDGs: Responding to New Challenges”. Washington DC.

- Kironde JML. 2015. Good governance, efficiency and the provision of planned land for orderly development in african cities: the case of the 20,000 planned land plots project in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Current Urban Stud. 3(04):348.

- Kironde JML. 2016. governance deficits in dealing with the plight of dwellers of hazardous land: the case of the Msimbazi River Valley in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Current Urban Stud. 4(03):303.

- Kombe WJ. 2005. Land use dynamics in peri-urban areas and their implications on the urban growth and form: the case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Habitat Int. 29(1):113–135.

- Kombe WJ, Kreibich V 2001. Informal land management in Tanzania and the misconception about its illegality. In ESF/N-Aerus Annual Workshop. “Coping with Informality and Illegality in Human Settlements in Developing Countries”, May 23–26, Leuven and Brussels.

- Kombe WJ, Kreibich W. 2006. Governance of Informal Urbanisation in Tanzania. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota.

- Laquinta D, Drescher A 2000. Defining peri-urban: understanding rural-urban linkages and their connection to institutional contexts. The Tenth World Congress of the International Rural Sociology Association, Brazil, Rio-de-Janerio.

- Lugoe NF. 2008. Assessment of main urban land use issues in Tanzania. Washington DC: The World Bank.

- Lupala A. 2008. Informal peri-urban land management in dar es salaam: the role of social institutions. J Plann Building Third World. 99:12–15. Trialog.

- Lutzoni L. 2016. In-formalised urban space design. Rethinking the relationship between formal and informal. City, Territory Architect. 3(1):20.

- Masanja AL 2003. Drivers of Land Use Changes in Peri-Urban Areas of Dar es Salaam City, Tanzania. A paper presented at the Open Meeting of the Global Environmental Change Research Community, October 16–18; Canada: Montreal.

- Massoi L, Norman A. 2010. Dynamics of land for urban housing in Tanzania. J Public Admin Policy Res. 2(5):74.

- McCloskey DN. 2016. Max U versus Humanomics: a critique of neo-institutionalism. J Inst Econ. 12(1):1–27.

- Moyo K 2017. Women‘s Access to Land in Tanzania: The Case of the Makete District [ Doctoral dissertation]. Stockholm (Sweden): KTH.

- Msale-Kweka C. 2017. Land use changes in planned, flood prone areas: the case of Dar es Salaam City. Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Ardhi University. Doctorial Theisis.

- Msangi DE 2011. Land acquisition for urban expansion: process and impacts on livelihoods of peri urban households, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania [ Licentiate Thesis]. Sweden. Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Msangi DE 2014. Organic urban expansion: processes and impacts on livelihoods of peri-urban households in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania [ Doctoral dissertation]. Ardhi University Dar es Salaam.

- Mushumbusi MZ. 2011. Formal and informal practices for affordable urban housing: case study. Dar es Salaam (Tanzania): KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

- Nelson A. 2018. Dalal Middlemen and peri-urbanization in Nepal. Rev Urban Affairs. 53:12.

- North DC. 1990. Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nuhu S. 2018. Peri-urban land governance in developing countries: understanding the role, interaction and power relation among actors in Tanzania. Urban Forum.

- Nuhu S, Mpambije CJ. 2017. Land access and corruption practices in the peri-urban areas of Tanzania: a review of democratic governance theory. Open J Social Sci. 5(04):282.

- Olajuyigbe AE. 2016. Drivers and traits of peri-urbanization in Benin City, Nigeria: A Focus on Ekiadolor community. Adv Social Sci Res J. 3:5.

- Quan J. 2006. Land access in the 21st century: issues, trends, linkages and policy options. London: UK. Natural Resources Institute University of Greenwich.

- Rahayu P, Mardiansjah FH. 2018. Characteristics of peri-urbanization of a secondary city: a challenge in recent urban development. IOP Conf Series: Earth Environ Sci. 126(1): 1–8. IOP Publishing.

- Rasmussen MI. 2013. The power of informal settlements. The case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J Urban. 1(6):1–11.

- Ratajczak-Mrozek M, Herbec M. 2013. Actors-resources-activities analysis as a basis for Polish furniture network research. Drewno. Prace Naukowe. Doniesienia. Komunikaty. 56:190.

- Rauws WS, de Roo G. 2011. Exploring transitions in the peri-urban area. Plann Theory Pract. 12(2):269–284.

- Ribot JC, Peluso NL. 2003. A theory of access. Rural Sociol. 68(2):153–181.

- Schroder F, Waibel M. 2012. Urban governance and informality in China’s Pearl River Delta. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie. 56(1–2):97–112.

- Shaw A. 2005. Peri-urban interface of Indian cities: growth, governance and local initiatives. Economic and Political Weekly, 129–136.

- Sheuya SA, Burra MM. 2016. Tenure security, land titles and access to formal finance in upgraded informal settlements: the case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Current Urban Stud. 4(04):440.

- Simon D, Adam-Bradford A. 2016. Archaeology and contemporary dynamics for more sustainable, resilient cities in the peri-urban interface. In: Basant M, Singh V. Thoradeniya B editors. Balanced urban development: options and strategies for liveable cities. Cham: Springer; p. 57–83.

- Sjaastad E, Cousins B. 2009. Formalisation of land rights in the south: an overview. Land Use Policy. 26(1):1–9.

- URT. 1967. Land acquisition act. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam:Government Printers.

- URT. 1977. The constitution of the united republic of Tanzania. Dar es Salaa: Tanznia:Government Printers.

- URT. 1995. The national land policy. Dar es Salaam (Tanzania):Ministry of Land Housing and Human Settlement Development, Government Printers.

- URT. 1999. The national land act. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam: Government Printers.

- URT. 2007a. Urban planning act. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam:Government Printers.

- URT. 2007b. Land use planning act. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam:Government Printers.

- URT. 2011. Urban planning regulations. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam:Government Printers.

- URT. 2015. Habitat III national report. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Land, Housing and Human Settlement Development. pp. 1–77.

- Van der Molen P. 2017. Food security, land use and land surveyors. Survey Rev. 49(353):147–152.

- Varley A. 2002. Private or public: debating the meaning of tenure legalization. Int J Urban Reg Res. 26(3):449–461.

- Voigt S. 2013. How (not) to measure institutions. J Inst Econ. 9(1):1–26.

- Wandl A, Magoni M. 2017. Sustainable planning of peri-urban areas: introduction to the special issue. Plann Pract Res. 32(1):1–3.

- Wasserman S, Faust K. 1994. Social network analysis: methods and applications. Vol. 8. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

- Wolff MS, Kuch A, Chipman JK. 2018. Urban governance in Dar es Salaam: actors, processes and ownership documentation. Working paper reference number C-40412-TZA-1. International Growth Center.