ABSTRACT

In June 2013, widespread popular unrest unexpectedly shook Brazil whilst the FIFA Football Confederations Cup was taking place. Nicknamed as the ‘demonstrations cup’ by protesters, this was one of the greatest uprisings in the history of the country, with its effects still being felt and discussed nationally and internationally. Despite the general consensus on the more immediate causes that sparked the movement – such as the protests by the Movimento Passe Livre against a 20-cent bus fare hike in São Paulo, heavy-handed police repression and the use of social media – there still lacks a holistic explanation about the historical processes that formed the inflammable scenario that triggered those demonstrations and their rapid dissemination. Using quantitative and qualitative data related to recent urban socio-economic changes and civil society mobilisation trends, the present paper constructs an original genealogy of the June 2013 ‘demonstrations cup’. As a result, it indicates a unique confluence of multiple causal factors, such as the rapid and generalised erosion of real income in the Brazilian metropolises, the degeneration of political representativeness and traditional movements, the emergence of new mobilisation tools and the dissemination of anti-mega-events critical subjectivities – hence providing a comprehensive and empirically informed account.

Introduction

In early June 2013, after more than 60 years, Brazil was again to host a major global football event. The Confederations Cup – a competition organised by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (hereafter FIFA) as a final test for the staging of the Football World Cup – was scheduled to begin on June 15. Expectations were high. The president of the Local Organising Committee for the World Cup stated that ‘The Confederations Cup is much more than our big dress rehearsal for the World Cup. The Festival of Champions is a chance to show the world we can deliver an unforgettable tournament for the fans, participants and the media’ (FIFA Citation2013).

It came to be an unforgettable tournament, but for very different reasons to those originally intended. As the competition proceeded, the country experienced what one national newspaper described as an ‘outbreak of demonstrations’ (Manso and Burgarelli Citation2013). In the space of just three weeks more than 2 million people took to the streets of around 350 different cities to express their dissatisfaction with the political system, the insufficient provision of urban services and the contrasting high public expenditures on mega sporting events. Attention turned from what was happening inside the stadiums to what had become Brazil’s largest wave of popular discontent in decades. On June 17, as the Tahitian and Nigerian teams were playing in Belo Horizonte, demonstrators broke into the national parliament building in Brasília. Three days later, protesters started a fire in the headquarters of the Ministry of External Relations. The president made a special statement, broadcasted by all the major TV networks, in an attempt to calm the population. Soon referred to as the ‘demonstrations cup’, this sort of unexpected parallel event caught the eye of the world and, for a moment, dwarfed the football stars.

The immediate causes for this historical uprising are well-known. On June 2, the Municipality of São Paulo implemented a bus fare hike of 20 cents. The Movimento Passe Livre (hereafter MPL) – a young social movement, with autonomist inclinations, demanding free public transportation – initially reacted with protests on June 6 and 7, demanding a reversal of the bus fare hike. These were relatively small demonstrations, gathering no more than 2,000 people each. However, the MPL managed to block Avenida Paulista – the main city thoroughfare. The consequent disruption and the clashes with the police particularly caught the attention of social media users and some mainstream commentators. From then on, momentum was built through an escalating combination of heavy-handed police violence, increasing mainstream media attention and online engagement through social media and livestreaming. After greater demonstrations on June 11th and 13th, which also began to mobilise a few other cities such as Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre, the movement reached its climax between June 17th and 20th when the local governments of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro finally reversed bus fare hikes. From this point, the original demands were widened to encompass much broader issues (Singer, Citation2014), with the number of participants now reaching more than 1.5 million across the country in one single day (Solano et al. Citation2014; Santini et al. Citation2017). The effects of the ‘demonstrations cup’ are still felt and discussed, including as precursor to the general political turmoil that has continued since and the later emergence of the far right in the country (Fernandes Citation2019; Miguel Citation2019).

What really caused it all?

Although such a sequence of facts has not been disputed, the same cannot be said about the deeper conditions that triggered them. Analyses initially tended to hinge deeper causal explanations on specific political, social or economic issues. Lima (Citation2013) focused on the declining legitimacy of political institutions and the exclusion of popular views from mainstream media. Sakamoto (Citation2013) highlighted the importance of a new generation of social media savvy activists, arguing that ‘Facebook and Twitter took the streets of São Paulo’. Maricato (Citation2013) emphasised as one of the main causes of discontent the inadequacy of recent urban policies, which worsened urban living conditions. Vainer (Citation2013) complemented this view, arguing that the urban crisis had been intensified by the ‘exceptional’ developments required by mega sporting events. The MPL (Citation2013) claimed recognition of their agency as a protagonist, whilst Braga (Citation2013) pointed to the new urban precariat as a fundamental actor.

Other analyses have argued that the ‘demonstrations cup’ was an effect of the success of ‘inclusive policies’ pursued by the incumbent Workers Party (hereafter PT). After emerging from the military dictatorship as the main left-wing force, PT became the national ruling party between 2003 and 2016. PT governments maintained neoliberal economic principles and privileged major capitalist sectors, but also facilitated income redistribution and credit expansion, driving consumerism among the lower classes. For Ubide (Citation2013), the 2013 protests signaled the coming into politics of the resulting new middle-class, emerging out of poverty and underdevelopment, thanks to PT policies made aware of historical state failures in service provision. This paradoxical idea, that the PT’s success – rather than its failure – contributed to the June 2013 uprisings, has been favoured by the PT itself, including the now former São Paulo mayor responsible for the bus fare hikes that sparked the protests (Haddad Citation2017).

Other authors have tried to conciliate both the fragmented critical approaches and the pro-PT view. Saad-Filho (Citation2013), for instance, argued that the ‘achievements of the PT administrations have raised expectations even faster than incomes’ (p.662) – hence propelling their demands for better public services. He recognises, however, that the PT governments have also demobilised traditional social movements by incorporating their leaders into the state apparatus and thus coopting them. This has alienated the grassroots of traditional popular organisations from institutional power, causing isolation and discontent. Saad-Filho also acknowledges the limits of the PT’s ‘left neoliberalism’, along with the role played by the then still very incipient economic slowdown and the dissatisfactions of the anti-inclusionary traditional middle-class.

For a genealogy of the ‘demonstrations cup’

The present paper, on the one hand, intends to move beyond the monocausality of early critical contributions, in the wake of Saad-Filho’s (Citation2013) more multi-causal approach. However, on the other hand, the paper also moves against Saad-Filho’s uncritical and largely unevidenced acceptance of the idea that social inclusion through successive PT governments lies at the root of the June 2013 protests.

To do so, this work explores the historical processes that constituted some of the key features of the ‘demonstrations cup’, especially the generalised dissatisfaction with urban living conditions and the emergence of a new generation of protesters, both indicated by opinion surveys conducted during the climax of the protests (Globo Citation2013). In order to satisfactorily grasp multi-causality, the present study is inspired by Foucault’s (Citation2007) concept of genealogy, using it in a loose and undogmatic way. This is originally defined as an ‘attempt to restore the conditions for the appearance of a singularity’- in our case, the ‘demonstrations cup’ – ‘born out of multiple determining elements of which it is not the product, but rather the effect’ (p. 64). Foucault emphasises that the genealogical approach does not take for granted ‘a principle of closure’ in such historical processes – as the proposition of demonstrations inevitably being propelled by a rise in expectations seems to suggest. They rather involve interactions between individuals or groups, as subjects who exercise agency. In other words, these are not processes which are already decided a priori, but are instead contingent on agents’ actions. Nevertheless, although Foucault’s original use of the concept also avoided the comprehension of genealogy as a linear and continuous development (Garland Citation2014), this is actually the case here. Therefore, as the genealogy of the ‘demonstrations cup’ presented below establishes the existence of different historical phases and is not focused on discursive practices, this is not a strictu sensu Foucaultian approach, but rather one inspired by its focus on multicausality and openness of historical processes.

Such a genealogical exploration, in its turn, occurs here methodologically in two stages. First, there is the use of statistical data concerning recent socio-economic urban transformations – more precisely, those that happened between the late 1980’s and the early 2010’s, with a focus on the latest years – to ‘unearth’ the material formation of the June situation. Official statistical data has regard to economic growth, redistribution of income, housing and transportation conditions, the use of new technologies and attitudinal accounts of political inclinations in the general population. As these datasets are extracted from different sources, they not necessarily cover the exact same period but rather slightly distinct subperiods within the general time frame of the new republic era (from late 1980s), signalling more general trends of change. Likewise, organisational trends of the urban civil society are explored by way of qualitative accounts about social movements activities, drawn from the specialised literature and from some of the organisations themselves through their own documents available in public domain, such as websites and reports. Of especial concern is those organisations that recently led the emergence of new forms of mobilisation, which were a particular feature of the ‘demonstrations cup’, involving leaderless horizontal movements and the expansive use of the internet as a mobilising tool.

The particular confluence of these developments is considered in the conclusion, which constructs an original genealogy of the June 2013 uprising and delivers a comprehensive account of the historical origins of those protests along with a brief consideration about its implications to the post-2013 scenario. Thus, the present work uses the general conceptual framing of the right to city, which privileges the role played by urban social movements as the source of change and innovation in the city (Castells Citation1983; Lefèbvre Citation1996/1968; Holston Citation1999), shedding new light on such state-civil society relationships. This framing has been recently used by other authors to analyse key features of the ‘demonstrations cup’ (Verlinghieri and Venturini Citation2018)

Recent socio-conomic transformations

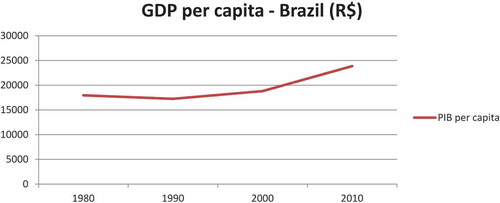

The events of June 2013 are tied to transformations happening in the daily lives of most of the Brazilian urban population. From Brazil’s re-democratization to the present, the main economic trend in the country has been the consolidation of economic development. Over the 1990s, the average annual growth rate of the Gross Domestic Product (hereafter GDP) remained close to 1.7%. In the 2000s, the average rate jumped to 3.3%, a level that was maintained into the early 2010s, indeed between 2010 and 2013 indicated by a rise, to 3.5% (IPEADATA Citation2014). Over the same period, there has been a slowing of population growth. (IBGE Citation2012). The combination of accelerating GDP growth and decelerating population growth resulted in unprecedented improvements in per capita GDP (IPEADATA Citation2014), as shown by .

Figure 1. GDP per capita in 2014 (R$).

Source: IPEADATA (Citation2014)

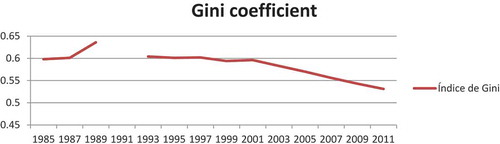

At the same time, moreover, the Gini coefficient dropped substantially between 1989 and 2011 (IPEADATA Citation2014), indicating a considerable reduction in labour income inequality off a high base, as illustrated by .

Figure 2. Gini coefficient – Brazil.

Source: IPEADATA (Citation2014) (No data for 1991)

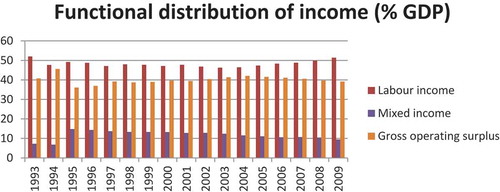

Furthermore, the functional distribution of income, which measures the allocation of income between factors such as capital and labour, also indicates an increase in the share distributed to labour since 2004, accompanied by decreases in the share of capital income, represented by the gross operating surplus, as well as in the income of self-employed workers, represented in terms of mixed income (IPEADATA Citation2014), as shown by .

Figure 3. Functional distribution of income – Brazilian GDP.

Source: IPEADATA (Citation2014).

More progressive minimum wage policy, together with a broader formalisation of labour, explains this gradual trend. While the minimum wage grew at close to 100% above inflation between 1995 and 2014, the rate of informal employment dropped from almost 60% of the working population at the end of the last century, to 47% in 2012 (IPEADATA Citation2014). These developments were accompanied by higher levels of job creation and the strengthening of income redistribution policies.

The combination of all such conditions drove significant gains in purchasing power for a large part of the population. In addition, during this same period, regulatory changes drove an increase in the supply of credit, which decisively underpinned the rapid expansion of the domestic consumer market. Between June 2003 and June 2013, credit operations jumped from 25% to 55% of Brazilian GDP(ANEFAC Citation2014).

Intuitively, this improving economic scenario could be seen as less conducive to the emergence of large-scale street protests. The country was experiencing accelerated economic growth, decreasing economic inequalities and an increase in the purchasing power of a considerable portion of the population, many of whom has been previously excluded from effective economic participation. As such, it was hoped that such a model would guarantee an increase in the level of satisfaction for both labour and capital. But economic indicators tell only part of the story.

The transportation crisis

One of the most important consequences of this rapid insertion into the consumer market was the rapid growth of automobile ownership which soared from 34.9 million in 2001 to 76.1 million in 2012 – the year of 2012 alone registered 14.6% of such an increase, showing an intensification of this process in recent years(Rodrigues Citation2013).This hyper-motorization led to a significant deterioration in transportation conditions in Brazilian cities, especially in big metropolises. Consequences were felt, for example, in the increase of the average commuting time in metropolitan areas, which went from 36 minutes, in 2004, to 40.8 minutes, in 2012 (Pereira and Schwanen Citation2013; IPEA Citation2013). The impact in the major capital cities of Southeast Brazil was particularly acute, given their high populations. In 2004, around 18% of the employees of the city of Rio de Janeiro took more than one hour commuting, while in São Paulo this proportion was 20% (Pereira and Schawanen Citation2013). In 2012, both measurements respectively increased to 24.7% and 23.5% (IPEA Citation2013).

These trends occurred in tandem with public policies that were already stimulating the use of individual transportation, such as tax exemptions on the production of automobiles and motorcycles coupled with above-inflation increases in public transportation fares. Between 2003 and 2009, oil prices hiked by 27.5% nationally, while the increase of the price of new cars did not exceeded 20%. Meanwhile, bus fares increased 63.2% (Carvalho and Pereira Citation2012). As such, there was a considerable migration of users from public to individual transportation, causing a generalized negative impact on standards of living.

The housing crisis

Another factor directly related to changes in the Brazilian economy was the growth of the real estate sector. There was an abrupt hike in real estate prices, especially in the metropolises of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Recife, Belo Horizonte and Fortaleza. Consequently, between January 2008 and June 2013 the average price for renting increased 88% in São Paulo and 131% in Rio de JaneiroFootnote1. Meanwhile, the national minimum wage grew by only 78% (IPEADATA Citation2014).

Not surprisingly, such changes had an impact on access to housing, which already was historically poor (Bonduki Citation2008). Between 2011 and 2012 alone, there was an average increase of more than 10% in the housing deficit of Brazilian metropolitan regions monitored by the Brazilian Institute for Statistics, also known as IBGEFootnote2 . This deficit was especially boosted by the rapid growth of housing costsFootnote3, causing a significant increase in the number of poor families – with income of up to three minimum wages, then equivalent to USD 933 – who spend more than a third of their income on rent. Across the country, this number increased 35% between 2007 and 2012 (FJP Citation2014).

An important role was played by the program ‘Minha Casa, Minha Vida’ (hereafter PMCMV), initiated in 2009 by the Federal Government. Although providing unprecedented funding for the construction of houses for families with an income of up to 3 minimum wages, PMCMV resource allocation mechanisms ensured that contractors would be able to decide where to build new homes. As a price saving mechanism, the lower income housing was often located in the cheaper and therefore more peripheral areas, bearing remarkable urban infrastructure deficits (Cardoso, Aragão and Souza Araújo Citation2011). At the same time, subsidies for the higher income bands – those between 3 and 10 minimum wages – focused on a credit guarantee scheme, which facilitated the purchase of properties already offered on the market. Thus, the Federal Government contributed directly to the expansion of real estate loans.

It wouldn’t be wrong, therefore, to expect that the deliberate heating of real estate markets, understood more as a countercyclical measure than as an urban policy instrument (Cardoso et al. Citation2011), would contribute to rising sale and rent prices. In doing so, public sector actions worked against their expected role in reducing the housing deficit for the lower classes by promoting their migration to precarious and peripheral areas, both through the construction of new subsidized homes in these regions and by indirectly induced gentrification.

The erosion of real income

According to David Harvey (Citation1973), the consideration of inequalities in cities entails going beyond traditional monetary mechanisms of resource allocations. One must also consider other ‘hidden mechanisms’ of distribution, especially the ‘price of accessibility’ to employment and welfare services and the ‘cost of proximity’ to noise and pollution, for instance. Thus, changes in the spatial layout of cities affect what Harvey calls real income, which is broader than just what one actually earns, but also encompasses the prices and costs paid by different agents to access important facilities such as schools, worksites and hospitals and to deal with unpleasant factors such as pollution from a factory next doors and the diseases caused by it, for example.

In this vein, the usually trumpeted statistical gains in terms of monetary income tended to be eroded by the spatial changes in motion in major Brazilian cities. As seen above, the relocation of the poorest to metropolitan peripheries worsened urban precariousness, by marginalising people from basic public services and access to employment opportunities. The consequent increased commuting time and cost tended to, at least partially, offset wage hikes.

Therefore, three fundamental characteristics of this process comprise the triggers for general dissatisfaction. First, there has been an accelerated degradation of transportation and housing conditions in most of the major Brazilian cities during a short period of time, i.e. between the mid-2000s and the beginning of the current decade in spite of wage hikes. Second, the scope of this phenomenon was not restricted to some portions of the population – such as more gradual gains in terms of purchasing power – but affected the daily life of practically all social strata. The increase in home to work commuting time affected all different ranges of income (Pereira and Schawanen Citation2013), including those who already owned motor vehicles. The gentrification driven by the rapid increase in real estate prices also affected the middle classes who were already well served by the housing market, causing other sorts of migration beyond the most evident concerning the more vulnerable classes.

Re-channeling dissatisfaction and by-passing intermediaries

Another factor would reinforce the general feeling of dissatisfaction generated by the deterioration of real incomes in major urban centres: the emergence of new forms of expression of dissent. As a direct consequence of induced domestic consumption and digital inclusion policies, the percentage of Brazilians 10 years of age or older with internet access increased from 20.9 to 46.5 % between 2005 and 2011 (IBGE Citation2013). This was accompanied by the rapid growth of mobile broadband access from 8.6 million in 2009 – 5% of total internet access via mobile phone – to 103.11 million in 2013 – 38% of total internet access via mobile phone (MC Citation2014). Following the rapid expansion of the internet, there was an accelerated growth of access to the so-called social media. Between February 2011 and June 2013, the number of Brazilian users of Facebook, for example, jumped from 10 million to 76 millionFootnote4, an increase of 660% (Veja Citation2013).

This phenomenon presents quantitative and, above all, qualitative changes. With the internet and social media, the expression of popular dissatisfaction is significantly less dependent upon mainstream media intermediaries, who play the role of gatekeepers for information dissemination in support of particular class interests. That does not mean that intermediation is automatically and fully eliminated by the internet. Cyber space is still mediated by consumer markets and surveilled by governments, with new methods of appropriation and intermediation being elaborated by dominant sectors, albeit in a manner that remains less defined that is the case for mainstream mediaFootnote5 . As such, unprecedented windows of opportunity have been opened for the expression of grievances shared by the majority of the metropolitan population.

If the mainstream media tended to temporarily lose its legitimacy as the main communicational channel, it is also the case that institutionalised politics tended to lose its legitimacy as the main political channel. In 2012, the number of people who declared themselves nonpartisan was unprecedented. Between 2007 and 2012, self-declared ‘nonpartisans’ went from 33 to 56% of Brazilians (Duailibe and Toledo Citation2013). This indicated an acute delegitimation of the political parties as traditional links between the population’s political demands and the political institutions was in course.

Mega sporting events in the eye of the hurricane

It is in such context that the controversial mega-events projects were planned and executed, fuelling some of those trends. The urban mobility projects designed for the 12 host cities, for instance, mostly comprised construction of exclusive lanes for bus rapid transit (BRT) and other road system improvements. Overall, the main goal was restricted to strengthening connections between airports, hotel chains and competition venues within the core municipalities of the metropolisesFootnote6. There was not, therefore, much evidence that such actions were intended to meet the broader demands of metropolitan commuters, such as through the prioritization of high-capacity public transportation like trains and metros, which are less polluting and serve to ease congestion on overburdened road systems.

Likewise, mega-event interventions reinforced real estate trends towards overvaluation. The removal of tens of thousands of poor families related to the FIFA World Cup and the Olympics was combined with the use of PMCMV houses as compensation. Furthermore, the concentration of the new urban infrastructure, such as sports and accommodation facilities, in neighbourhoods targeted by real estate expansion agents also reinforced gentrification dynamics (Maricato Citation2013; Vainer Citation2013; ANCOP Citation2014).

Altogether, these different processes deepened the legitimacy deficit of Brazilian institutions and their development model. The main outcomes were a rapid erosion of real income and collective standards of living coupled with the opening of more spontaneous intra-population channels of communication. Unlike the more gradual and restricted increase in purchasing power and its consequent expansion of consumerism, these more negative processes happened in a shorter period of time affecting more people. The preparation for the FIFA Confederations Cup and the FIFA World Cup exacerbated such an urban crisis, as its projects propelled further the expansion of the exhausted road transportation model and gentrification.

Therefore, economic growth based on the expansion of the consumer market without the proper use of public investment to counteract its negative consequences accelerated the processes of the erosion of real income in major Brazilian cities. The inability of the political institutions in dealing with the inherent contradictions of capitalist development was a key factor.

In view of the above, it can be concluded that the emergence of broad dissent around the inadequacy of public expenditure associated with mega sporting events and their impacts played an important role in the pre-Confederations Cup context, coinciding with the general dissatisfaction caused by the Brazilian urban crisis and by rapid real income losses. Nevertheless, there was also another important factor that sparked the June demonstrations: the dissemination of critical subjectivities, initially by politically organised civil society groups, and later considerably absorbed by the unsatisfied masses, to which we now turn.

Organisational trends in civil society

Certain historical associational trends in Brazil played a driving role in the June 2013 demonstrations. Particularly, Brazil experienced the prior development of counter-hegemonic and non-hegemonic groups, demanding greater social transformations and, therefore, tending to be better aligned with the general dissatisfaction growing in Brazilian society.

Fundamentally, counter-hegemonic movements aim at disseminating their worldviews in such a way as to render them hegemonic in civil society. This means the ideological labour of transforming their particular ideals into something universal, hence accepted, incorporated and pursued by other social groups, to a greater or lesser extent. Sympathetic to Marxist tendencies, but not limited to them, counter-hegemonic movements seek to exert greater influence over public policies, often calling for direct participation in the State apparatus. Leadership and hierarchy are understood as necessary organisational vehicles for the achievement of objectives (Graeber Citation2004; Day Citation2006; Purcell Citation2012).

Alternatively, non-hegemonic movements tend to pursue alternative ways of life and social organization. Influenced by anarchism and autonomism, these groups do not aim to become hegemonic, but rather to perpetuate a constant resistance through anti-hierarchic practices. In this sense, there is a disavowal of the fight for the State apparatus and, consequently, for the domination over other groups. Horizontality in social relations is key and the search for maintenance of different worldviews and methods of organization overcomes the attempt to make them dominant in society (Graeber Citation2004; Day Citation2006; Purcell Citation2012).

Such a classification is not intended to exhaust the field and should not be applied rigidly. Associational trends in civil society are not isolated and, therefore, there are bridges and exchanges between them.

Counter-hegemonic movements

Since the 1970s, there has been a significant reduction in the influence of unions and political parties, which hitherto represented action logics based on corporatism and classism (Avritzer Citation1997). New political practices fundamentally organised at the local level began to spread in Brazilian metropolises, as demonstrated by the proliferation of community associations that sought to ensure social rights denied by the 1964–1985 military dictatorship (Boschi Citation1987). Also the urban middle classes socially consolidated their particular methods of political action, which included practices that broke with the idea of collective action restricted to the popular sector and focused on the representation of the interests of independent professionals and cultural identities (Avritzer Citation1997). This has been largely connected to the broader emergence of new social movements (Touraine Citation1985).

Despite the consequent increasingly fragmented agendas, there were common demands for the re-democratization of the country. They were fundamental to the subsequent implementation of participatory mechanisms by local PT governments, such as participatory budgets and consultative local policy boards and councils. However, the concomitant implementation of neoliberal reforms created an institutional vacuum regarding policy areas previously served by the Government, such as welfare provision, forcing a reconfiguration of the associative field during the 1990s. On the one hand, a large number of new NGOs emerged to assume functions that had been performed by the State. On the other hand, there was a reconfiguration of traditional social movements who now sought greater participation in the new institutional mechanisms of social control to address the direct consequences of globalisation, such as the precarization of labour, unemployment and urban violence. Although by different routes, both sets of groups moved toward closer relations with the State, either in the form of a partnership between the Government and civil society for the delivery of services or through the institutionalization of the influence of civil society in the construction of public policies (Gohn Citation2008).

Participatory experiences initially developed at a local scale quickly expanded in the early 21st century as the PT also began winning national elections. In 2001, 45.92% of NGOs affiliated to the Brazilian Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (hereafter ABONG) claimed to participate in some public policy council. By 2004, this number rose to 64.36%, representing a total of 130 NGOs (ABONG Citation2001; Citation2004), as shown by .

Table 1. Participation of affiliated NGOs in councils, networks and forums.

At the same time, there was a tendency to develop inter-territorial and inter-sectoral collaboration by means of networks and forums as a way of adapting to the context of globalisation, expanding the reach and effectiveness of struggles that used to be more restricted in scope (Scherer-warren Citation2006). In 2001 there were 140 ABONG affiliates participating in networks. By 2004 they would reach more than 160 NGOs, or more than two-thirds of the total number of ABONG affiliates (ABONG – Associação Brasileira de Organizações Não-governamentais Citation2001, Citation2004).

Thus, the first decade of the new millennium saw innovations in the various forms of articulation between mobilising agents. However, the formation of new spaces for negotiation also tended to exacerbate tensions between the State and civil society, as the balance between autonomy and participation in negotiations with the State became potentially delicate (Scherer-warren Citation2006). Such contradictions began to emerge in the second half of the 2000s. The increasing dissemination and consolidation of organizations, forums and networks met limits to civil society participation in fundamental state decisions. From a qualitative point of view, participation tended to be restricted to consultative arrangements, often with a small popular representation. Furthermore, consultation processes tended to be transformed into formalities intended to legitimate decisions already taken (Omena de Melo Citation2013). Also there was increasing co-option of leaders of traditional unions and social movements, creating a division between leadership and the rank-and-file (Morais and Saad-Filho Citation2011).

The combination of these factors created disappointment in the new institutional architecture. In the foreground, the grassroots of social movements and NGOs that used to demand the deepening of democracy in the direction of more participative practices began to question outcomes. Their demands did not find a satisfactory answer in Government, which had itself compromised with neoliberalism and its corresponding urban entrepreneurship (Harvey Citation1989). This is expressed, for instance, by the sharp decline in the number of participants in important new participatory institutional mechanisms, such as the National Conference of Cities, which went from 200,000 people in 2005 to 140,000 in 2010Footnote7 . Therefore, at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, an ambience of disapproval was taking root within the counter-hegemonic movements.

Non-hegemonic movements

After several decades relegated to a relatively marginal role, non-hegemonic initiatives began to resurface internationally from the 1970s, against the background of the crisis of the welfare state and the decline of so-called real socialism(Katsiaficas Citation1997). An important point of this new phase was the 1994 Zapatista uprising against neoliberalism and the Mexican State and the following international anti globalisation movement. Four years after the Zapatista manifesto, the first conference organised by the People’s Global Action (hereafter PGA) took place in Geneva, Switzerland. By bringing together social movements from all continents, such a meeting had the objective of initiating the coordination of the so-called ‘Global Days of Action’, aimed at the joint articulation of anti-capitalist resistance to neoliberal globalisation and its agents by means of direct action. From this point on, street demonstrations were organised simultaneously in various cities around the world to coincide with the meetings of supranational organizations, such as the International Monetary Fund and the G7, seen as promoters of global capitalism (Curran Citation2006).

The rise in the North of the anti-globalisation movement became an important inspiration for certain urban countercultural, broadly anarchist articulations in Brazil. Clashes between police and demonstrators during the Seattle protests in 1999 particularly motivated Brazilian groups to get organised around the PGA and collaborate with anti-capitalist demonstrations in Europe and the USA. As such, a growing number of Global Days of Action were organised in several cities in Brazil in the year 2000. However, the experience proved to be short-lived, as in 2001 and 2002 the movement lost momentum, with the last attempts to revive PGA activities failing in early 2003 (Ortellado Citation2004).

Despite the dilution of the anti-globalisation movement in Brazil, the brief experience of the Global Days of Action generated new exchanges between old and new activists, propelling several other local and national initiatives. In the midst of these new self-managed experimentations, two groups stood out due to their strength and longevity: the Centro de Mídia Independente (hereafter CMI) and the Movimento Passe Livre (hereafter MPL) (Liberato Citation2006). Whereas the former represented a new form of activism, based on the non-mediated self-expression of activists – which later became a particularly important feature of the 2013 protests – the latter was based on the promotion of transportation as a fundamental human right – later largely recognised as providing the initial spark for the ‘demonstrations cup’. Thus, it is worth understanding more about their respective influential historical trajectories.

Initially inspired by the 2003 ‘Revolta do Buzú’ (Bus Rebellion), which took place in Salvador, autonomist student movements opposing bus fare hikes rapidly spread to other urban centres in the country. Exchange between these different groups consolidated in 2004 and, especially, in 2005, with the ‘Plenária Nacional do Passe-livre’ (National Free-Fare Plenary) convened during the 5th World Social Forum in Porto Alegre. During this event, the MPL was founded, cementing its commitment to the principles of decentralization, federalism, autonomy and nonpartisan-ism (Liberato Citation2006).

A few years later, the MPL would expand the scope of its claims and its relationship with institutions by placing the demand for ‘zero-fare’ at the center of its goals (MPL Citation2013). The priority, at this point, was not just guaranteeing free pass for students, but also the universalisation of public transportation through the abolition of direct costs to the user, an idea originated during the first terms of the PT in São Paulo’s Municipal Government in the early 1990s. Additionally, later in that decade, various demonstrations against fare increases throughout the country started to reverse Government decisions by enforcing negotiations between movements and local authorities.

Similarly, the CMI continues to be active at the time of writing, being another successful group from the anarchist tradition, as reformulated in the anti-globalisation movement. Indymedia, as it is known internationally, was created shortly after the 1999 Seattle protests to provide an alternative source of information to the mainstream media. Its motto was one of non-intermediation in the production of news, which was to be created and broadcast by ordinary people. In a short period of time the CMI had already been established in major Brazilian cities.Self-declared as partial, activist and anti-capitalist, the CMI also expanded its coverage beyond anti-globalisation protests, coming to embrace the more general theme of social movements and their actions. This meant improved collaboration with several other groups. The CMI played an important role, for instance, in the consolidation of the MPL, through its wide dissemination of the MPL’s early demonstrations (Liberato Citation2006).

Thus, the trajectories of both groups represent the main outcomes of the tradition of non-hegemonic movements. Their relative successes can be explained by the expansion of their original scope, a decision propelled by the expansion of their links with other movements and institutions. The MPL’s ‘nonpartisan-ism, though not anti-partisan-ism’ statementFootnote8 and the CMI’s emphasis ‘on social movements, particularly those of direct action (the “new movements”) and on the policies which they oppose’, place them into what could be called a zone of intersection with counter-hegemonic trends, where interactions between both fields tended to be welcomed.

In the face of concrete urban problems and unsatisfactory governmental answers, the MPL sought to combine autonomy and horizontal organization with precise interventions into the functioning of the state. This involved a departure from a radical disavowal of the state. Similarly, the CMI sought to act under the slogan ‘Hate the media? Be the media!’Footnote9, emphasizing methods of non-representation and direct action in the informational field, to strengthen the influence of social movements of various kinds over public policies.

Thus, the situation on the eve of the announcement of the Brazilian mega sporting events was one of growing disillusionment on the part of counter-hegemonic groups, due to the limitations in the institutionalisation of participation in the state apparatus. In addition, some of the most prominent groups in the non-hegemonic field were becoming more influential. The emergence of popular mobilisations against the FIFA World Cup and the Olympics would draw upon and intensify such tendencies.

Social mobilisations in the era of mega sporting events

In the early 2010s, as the major projects concerning the mega sporting events turned from planning to execution, the impacts of such transformations were gradually experienced by the population. It is estimated that nearly 200,000 people were either removed or threatened with eviction from their homes as a direct result of preparations for the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympics (Souza Citation2012). Concomitantly, the privatisation of stadiums, the destruction of urban infrastructure, the curtailment of street vending, the precarious conditions faced by construction workers, the numerous changes of both legislative and executive orders, the high costs of projects and the absence of popular participation were also increasingly felt (Vainer Citation2013; ANCOP – Articulação Nacional dos Comitês Populares da Copa Citation2014).

All such issues forced the repositioning of an important part of organised civil society. One of the most eloquent responses came from the National Articulation of Popular Committees for the World Cup and the Olympics (hereafter ANCOP), an umbrella network formed by local groups known as ‘Comitês Populares da Copa do Mundo’ (the Popular Committees for the World Cup, hereafter CPCMs) created in each host city by urban movements, NGOs and institutions to denounce and fight against human rights violations associated with the mega sporting events. (Omena de Melo Citation2013).

Some of the groups forming the CPCMs had previously participated in the new institutional mechanisms developed since the country’s re-democratisation. Their main claims have focused on the promotion of the rights to housing, decent work, sports and leisure, public transportation, and transparency and direct popular participation in public policy – all usually encapsulated in the demand for the right to the city (ANCOP – Articulação Nacional dos Comitês Populares da Copa Citation2014). The CPCMs developed into a key space of discussion and negotiation between various organizations about joint actions. It denoted a deepening of the trend, initiated in the 1990s, of bringing diverse groups together around thematically cross-cutting networks.

If the counter-hegemonic sectors formed new specific mobilisation networks targeting the FIFA World Cup and Olympics projects and their consequences, this was less prominently the case for groups more prone to acting in the non-hegemonic field. However, paradoxically, the most prominent post-anti-globalisation survivors, i.e. the CMI and the MPL, were the ones that moved more vigorously to give greater visibility to the impacts of the mega sporting events.

In 2009, the MPL decided to promote discussions exclusively focused on the possibility of using the new context to forward their demands in the public sphere (MPL Citation2009), particularly addressing the need to respond new challenges in the area of urban mobility. The movement also strengthened its links to groups of different kinds. In 2012, for example, the MPL of São Paulo (MPL-SP) joined the CPCM of São Paulo (CPCM-SP, no date), sometimes participating in the protests organised by them (MPL Citation2012). CMI also gave special attention to the impacts of the mega sporting events, by publicizing attempts by groups and networks to address resulting issues. Between 2011 and 2012, the CMI devoted no fewer than 22 editorials to demonstrations against the FIFA World Cup projects, 9 of which focused on the actions organised by the CPMCs.

At the same time, 2011 brought a new wave of protests internationally, which would again inspire other non-hegemonic local movements, indeed also redirecting the activities of some groups to global issues. Internationally prominent protests included the Arab Spring, the Spanish ‘Indignados’ and, particularly, the Occupy Wall Street movement. They all called for decentralization of popular mobilisations and were convened especially by young people through social media, whilst conveying their discontentment with institutional policies. In addition, the permanent occupation of urban public spaces was adopted as a favoured tool of direct action.

Brazil would only join this international map of horizontalist mobilisations in the last months of 2011, when global protests in support of the demonstrators camped in New York emerged. On October 15 of that year, Occupy protests happened in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Campinas, Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, Porto Alegre and Salvador. This experience was, however, fleeting. By the beginning of 2012, Brazilian occupation camps, as the one in Rio de Janeiro shown by , had already been destroyed by the police. Despite not growing to more than a few hundred participants, the Brazilian Occupy movement was symptomatic in many senses. First, it indicated a deepening disillusionment with political and economic institutions, especially from a younger generation. Second, the permanent occupation of public spaces for debate and experimentation was an important novelty to overcome the traditional ‘one-off’ protests. Combining a growing dissatisfaction with the search for innovations, young people managed to transform virtual engagement into actual collective action, spatializing their indignation in the public squares. Some of Occupy´s main achievements in Brazil were the formation of critical subjectivities about political issues and the introduction of new forms of relationship with public spaces and action methods. These were particularly augmented by the novelty of live broadcasts via the internet – also known as livestreaming – a tool then already being adopted by Occupy Wall Street. The transposition of the virtual and diffuse discontentment, typical of some non-hegemonic networks, to an incipient political organization focused on public squares, contributed to other renewed local actions and their dissemination, such as a new day of global action that celebrated a year of the protests of the Spanish Indignados and the occupation of the entrance of the residence of the Governor of the State of Rio de Janeiro in the first half of 2012 (Jornal do Brasil Citation2012).

The urban restructuring connected to the mega sporting events also forced these new non-hegemonic groups to engage with the subject. The successive evictions of anarchist squatters spurred the creation of new organizations and mutual support between them.Footnote10 All such mobilisations counted on the dissemination of press releases, videos and direct online broadcasting.

Altogether, these innovations propelled the creation of intersubjective conditions for the development of criticism against the FIFA World Cup, built gradually through the joint production of counter-information by counter-hegemonic networks along with different generations of non-hegemonic groups. At the same time, new practices of direct action inspired by the international movements were increasingly absorbed into both counter-hegemonic and non-hegemonic fields.Footnote11

This scenario, characterized by the collective dissemination of counter-information, would very quickly escalate toward a confluence of many different groups in direct action. Records of the activities of the CPCMs, for instance, indicate important changes in the process of counter-hegemonic mobilisations, as shown by below. Initially, in 2012, the activities of the CPCM of Rio de Janeiro focused on raising awareness within civil society, with limited attention being paid to street protests.

Table 2. Activities developed by the CPCMO-RJ. (CPCMO-RJ, Citation2014).

In the first half of 2013, there was a shift towards protest. In comparison with the previous year, there was a growth of 100% in street protests, whilst the organization of public debates, publication of documents and inter-organizational meetings fell by half. Particularly notable was the concentration of 6 demonstrations in early 2013, anticipating the large mobilisations of June – a number coming very close to the total number of protests in 2012.

This is an important indication of a wider process of intensifying mobilisation. In 2011 and 2012, organizations of a more counter-hegemonic character consolidated themselves in civil society as promoters of critical views about the process of preparation for mega sporting events. In more restrained fashion, the non-hegemonic groups also contributed to that effect, whether through organizations such as the CMI and the MPL or by the action of the ‘ocupas’. The rapid intensification of street protests in the first half of 2013 emerged from sustained grassroots work of awareness raising over the previous two years.

This escalation combined with similar trends that had been consolidating in other sectors of organised civil society. At the beginning of the decade, the union movement, for example, intensified its own direct actions (Braga Citation2013), by almost doubling the number of strikes between 2010 and 2012, which jumped from 446 to 873 (DIEESE Citation2013). Trade unions involved with works in preparation for the FIFA World Cup contributed significantly to that increase, as the stadiums under reconstruction became the target of 26 strikes between 2011 and 2014 (Rede Brasil Atual Citation2014).

Prioritization of direct action also converged with the mobilisation of autonomist groups. The MPL’s demonstrations against the increase in bus fares – generally considered as the catalyst of the June protests – happened in a context particularly inflamed by the issues brought by mega sporting events, which were surrounded by an urban crisis and an intensified illegitimacy of government amongst various movements. Concomitantly, the spread of new communication technologies, especially the video broadcasts via mobile telephony, which gained relevance since the occupations of public squares in 2011, expanded the repertoires of action and substantially increased the reach of the collective escalation toward direct action.

Conclusions

The multiple triggers of the protests that happened during the 2013 Confederations Cup in Brazil reveals a more complex causality than that presented by existing narratives. The ‘demonstrations cup’ was neither simply the result of an urban crisis (Maricato Citation2013), nor of the mobilisation of social movements (MPL – Movimento Passe-livre Citation2013), nor of the claims for improvements in public services (Braga Citation2013), nor of the erosion of the legitimacy of media and politicians (Lima Citation2013), nor of the innovation brought by the internet (Sakamoto Citation2013). It was actually the unique convergence of all these and other elements that made the ‘demonstrations cup’ possible. The multi-causality of the ‘demonstrations cup’ cannot be simplistically subsumed to a by-product of the success of the PT ‘inclusive’ policies either, which supposedly raised expectations that were not met and caused unrest (Ubide Citation2013; Saad-Filho Citation2013; Haddad Citation2017).

Alternatively, a much more elaborated genealogy of June 2013 is necessary. It can be summed up in three different phases. First, from the late 1980s until the mid-2000s there were slow but continuous improvements in the socio-economic conditions of most of the population, underpinned by economic growth coupled with some intermittent income redistribution. Concomitantly, some counter-hegemonic groups of civil society gradually constructed inter-sectoral and inter-territorial networks that allowed cohesive collective actions demanding more participation in public policies, eventually achieving relative success at different governmental scales. Moreover, non-hegemonic groups began to grow under the inspiration of the international anti-globalisation movements.

The second phase, stretching from the mid-2000’s to the first years of the 2010’s, involved an intensification of economic growth and redistribution of income, combined with a rapid expansion of the domestic consumption market. However, as a consequence, the already precarious urban infrastructure was heavily burdened, particularly the transportation systems and the housing supplies, eroding the real income of most of the urban population and causing severe and generalized dissatisfaction. The unprecedented communication opportunities provided by the same process of consumption incentives paved the way for the exponentialization of grievances through the rapid expansion of internet access and social media. Meanwhile, counter-hegemonic groups became increasingly disappointed with the limitations found in the participation mechanisms previously established by the State. The non-hegemonic groups, in turn, grew in importance, introducing new methods of direct action inspired by the Occupy movement and expanding their inter- and intra-network connections.

The development projects related to mega events were announced at the very end of this phase. They became the ‘straw that broke the camel’s back’, as they deepened the general erosion of real income by fueling the urban crisis with more real estate investment, cosmetic interventions, large-scale evictions and very limited transportation projects. Furthermore, they also became a target around which several counter-hegemonic and non-hegemonic groups could converge, especially via the creation of new thematic networks, such as the Popular Committees for the World Cup. The main result was the collective and systematized dissemination of critical subjectivities on the projects designed for the World Cup, which would conveniently merge with the general mood of dissatisfaction among the population.

This all produced the third phase, which is marked by an abrupt radicalization of part of the organised civil society between the end of 2012 and the first half of 2013. This is illustrated by a rapid increase in the number of street protests promoted by counter-hegemonic networks and union strikes, some of them directly targeted the construction of stadiums. The protests organised by non-hegemonic groups, mostly represented by the usual MPL mobilisations against bus fare hikes, but not restricted to them, brought important innovations associated with new communicational technologies and methods of direct action, which were the final – rather than the initial – spark in such an inflammable scenario.

In the light of the above findings, the genealogy of the ‘demonstrations cup’ mainly contributes to the debate by providing a comprehensive account of the origins of those protests, highlighting not only multiple causal factors but, more importantly, the unique historical relations between them and their contradictions. It indicates that an accumulation of choices made by State representatives in terms of economic, social and urban policies and their relations with the political dynamics within civil society in recent decades had decisive – though undeliberate – influence. The ‘demonstrations cup’, therefore, did not happen because of 20 cents, but due to more than 20 years of unresolved contradictions regarding the Brazilian urban, social, economic and political developments. And its undeniable importance in recent Brazilian history and political developments reinforce the advantages of analyses that keep the focus on relationships between urban social movements and innovation of planning practices.

Last but not the least, it is also worth making a brief consideration about some implications of such conclusions. Most of the characteristics found at the historical roots of the June 2013 protests did not vanish after people left the streets. On the contrary, disillusion about failed development models and degraded urban living conditions – as much as their stark contrast with pharaonic white elephants left behind after mega-events; the erosion of links between political representatives and those represented by them; frustration due to unmet promises of greater participation of the population and movements in the design of public policies; and the growing usage of new technologies such as the internet and social media to express dissent and intervene politically; they all became a very relevant part of the current socio-political context. In fact, these issues are more present than ever in the public sphere. Addressing them is of essence for movements and political forces aiming at greater social justice in the post-2013 Brazil, where far right forces managed to took advantage of the new conditions to build momentum and gain the political upper hand nationally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Erick Omena de Melo

Erick Omena de Melo is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Observatory of Metropolises/Institute of Urban and Regional Planning and Research/Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, with a PhD in Planning and Urban Politics at Oxford Brookes University.

Notes

1. For more information, see http://www.zap.com.br/imoveis/fipe-zap-b/.

2. Survey for the metropolitan regions of Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, São Paulo, Fortaleza, Rio de Janeiro, Recife, Porto Alegre, Belém and Salvador (FJP Citation2014), representing 31% of the Brazilian population.

3. The other criteria for the calculation of housing deficit are: precarious infrastructure, family cohabitation and the excess residents in rented homes.

4. This is equivalent to 40% of the population.

5. Information on the then still incipient new barriers created can be found at http://oglobo.globo.com/sociedade/tecnologia/facebook-reduz-alcance-organico-das-paginas-11968134.

6. Details of the distribution of investments can be accessed at http://www.portaltransparencia.gov.br/copa2014/empreendimentos/tema.seam?tema=8.

7. Data available at http://www.cidades.gov. br/5conferencia/conferencia/historico.htm.

8. Available at http://tarifazero.org/mpl/.

9. Available at http://www.midiaindependente.org/pt/blue/static/about.shtml.

10. See, for example, http://terraeliberdade.org/atividade-do-1o-de-maio/and http://ocupario.org/2012/11/10/urgente-apoio-aldeia-maracana/.

11. See, for example, http://www.pragmatismopolitico.com.br/2012/02/apos-9-dias-de-greve-de-fome-em-frente.html.

References

- ABONG–Associação Brasileira de Organizações Não-governamentais. 2001. ONGs no Brasil: perfil das associadas à ABONG. Rio de Janeiro: ABONG.

- ABONG–Associação Brasileira de Organizações Não-governamentais. 2004. ONGs no Brasil: perfil das associadas à ABONG. Rio de Janeiro: ABONG.

- ANCOP – Articulação Nacional dos Comitês Populares da Copa. 2014. Megaeventos e violações de direitos humanos no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: ANCOP.

- ANEFAC – Associação Nacional dos Executivos de Finanças, administração e Contabilidade. 2014. Análise de dez anos do crédito no país - edição 2013. http://www.anefac.com.br/paginas.aspx?ID=658.

- Avritzer L 1997. Um Desenho Institucional para o Novo Associativismo. Lua Nova, nº 39. São Paulo.

- Bonduki N. 2008. Política habitacional e inclusão social no Brasil: revisão histórica e novas perspectivas no governo Lula. Revista eletrônica de Arquitetura e Urbanismo. 1:70-104.

- Boschi RR. 1987. A arte da associação política de base e democracia no Brasil. São Paulo e Rio de Janeiro: Vértice e Instituto Universitário de Pesquisas do Rio de Janeiro.

- Braga R. 2013. Sob a sombra do precariado. In: MARICATO E, editor. Cidades re-beldes: passe livre e as manifestações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil. São Paulo: Boitem-po/Carta Maior; p. 79–82.

- Cardoso AL, Aragão TA, Araújo FS. 2011. Habitação de Interesse Social: política ou mercado? Reflexos sobre a construção do espaço metropolitano. Rio de Janeiro: Anpur: Encontro da ANPUR; p. 1–20.

- Carvalho CHR, Pereira RHM. 2012. Gastos das Famílias Brasileiras com Transporte Urbano Público e Privado no Brasil: uma Análise da POF 2003 e 2009. IPEA, [accessed 2012 Dec]. http://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/TDs/td_1803.pdf.

- Castells M. 1983. The city and the grassroots. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- CPCMO-RJ – Comitê Popular da Copa e Olimpíadas do Rio de Janeiro. 2014 July. Megaeventos e violações de direitos humanos no Rio de Janeiro: dossiê do Comitê Popular da Copa e Olimpíadas do Rio de Janeiro. CPCMO, https://comitepopulario.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/dossiecomiterio2014_web.pdf.

- CPCM-SP - Comitê Popular da Copa de São Paulo. 2014. Quem apoia e compõe o comitê. CPCM. [accessed 2014 Jun 3]. http://comitepopularsp.wordpress.com/o-comite/quem-apoia-e-compoe-o-comite/.

- Curran G. 2006. 21st century dissent: anarchism, anti-globalization and environmentalism. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Day R. 2006. Gramsci is dead: anarchist currents in the newest social movements. Ann Arbor: Pluto Press.

- DIEESE – Departamento Intersindical de Estatístcia e Estudos Sócio-econômicos. 2013. Balanço das greves em 2012. Estudos E Pesquisas. 66:35.

- Duailibe J, Toledo JR. 2013 January 19. Apartidários são maioria no país pela primeira vez. Estado de São Paulo. http://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,apartidarios-sao-maioria-no-pais-pela-primeira-vez-desde-a-redemocratizacao,986376.

- Fernandes S. 2019. Sintomas mórbidos: a encruzilhada da esquerda brasileira. São Paulo: Autonomia Literária.

- FIFA – Federation International de Football Association. 2013. LOC board hold last general meeting before FIFA Confederations cup. http://www.fifa.com/confederationscup/news/y=2013/m=5/news=loc-board-hold-last-general-meeting-before-fifa-confederations-cup-2080715.html.

- FJP – Fundação João Pinheiro. 2014. Nota Técnica 1 Déficit Habitacional no Brasil 2011-2012: resultados preliminares. Belo Horizonte: CEI.

- Foucault M. 2007. The politics of truth (Ed. Sylvere Lotringer). Los angeles: Semiotext(e).

- Garland D. 2014. What is a “history of the present”? On Foucault’s genealogies and their critical preconditions. Punishment Soc. 16(4):365–384.

- Globo. 2013. Veja pesquisa completa do IBOPE sobre os manifestantes. Globo, [accessed 2014 Jun 01]. http://g1.globo.com/brasil/noticia/2013/06/veja-integra-da-pesquisa-do-ibope-sobre-os-manifestantes.html.

- Gohn MG. 2008. O protagonismo da sociedade civil: movimentos sociais, ONGs e redes solidárias. 2 ed. São Paulo: Cortez.

- Graeber D. 2004. The new anarchists. In: Mertes T, editor. A movement of movements: is another world really possible? New York: Verso; p. 202–215.

- Haddad F 2017 Vivi na pele o que aprendi nos livros. In Revista Piauí. http://piaui.folha.uol.com.br/materia/vivi-na-pele-o-que-aprendi-nos-livros/

- Harvey D. 1973. Social justice and the city. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Harvey D. 1989. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler. 71B:3–17.

- Holston J. 1999. Spaces of insurgent citizenship. In: Holston J, editor. Cities and citizenship. Durham (NC): Duke University Press; p. 155–173.

- IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2012. Censo Demográfico 2010. IBGE, [accessed 2014 Aug]. http://www.censo2010.ibge.gov.br/index.php.

- IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2013. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios: acesso à internet e posse de telefonia móvel celular para uso pessoal 2011. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE.

- IPEA – Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. 2013 October. Indicadores de mobilidade urbana da PNAD 2012. Comunicações Do IPEA. 161. http://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/comunicado/131024_comunicadoipea161.pdf.

- IPEADATA. [accessed 2014 Jun 15]. www.ipeadata.gov.br.

- Jornal do Brasil. 2012. Em protesto, estudantes acampam na frente da casa de Cabral. Jornal Do Brasil. [accessed 2014 Aug 10]. https://www.jb.com.br/index.php?id=/acervo/materia.php&cd_matia=624972&dinamico=1&preview=1.

- Katsiaficas G. 1997. The subversion of politics: European autonomous movements and the decolonization of everyday life. New York: Humanity Books.

- Lefèbvre H. 1996/1968. Writings on cities. trans. and ed. E.Kofman and E.Lebas. Blackwell: Oxford.

- Liberato LVM. 2006. Expressões Contemporâneas de Rebeldia: poder e fazer da juventude autonomista. PhD Diss., Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

- Lima V. 2013. Mídia, rebeldia urbana e crise de representação. In: Cidades Rebeldes: passe Livre e as manifestações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo; p. 89–94.

- Manso BP, Burgarelli R 2013. Epidemia’ de manifestações tem quase 1 protesto por hora e atinge 353 cidades. http://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,epidemia-de-manifestacoes-tem-quase-1-protesto-por-hora-e-atinge-353-cidades,1048461.

- Maricato E. 2013. É a questão urbana, estúpido!. In: Cidades Rebeldes: passe Livre e as manifestações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo; p. 44–63.

- MC – Ministério das Comunicações. 2014. Acesso à internet e direitos do consumidor: balanço e perspectivas. MC, [accessed 2014 Jun 03]. http://www.idec.org.br/pdf/arthur-coimbra-mc.pdf.

- Miguel LF. 2019. O colapso da democracia no Brasil. São Paulo: Expressão Popular/Rosa Luxemburgo.

- Morais L, Saad-Filho A. 2011. Brazil beyond Lula. Lat Am Perspect. 38(2):31–44.

- MPL – Movimento Passe-livre. 2009. Como a copa de 2014 afeta a mobilidade urbana? MPL, [accessed Jul 18]. http://tarifazero.org/2009/10/23/1137/.

- MPL – Movimento Passe-livre. 2012. Toda a cidade pra todos! MPL, [accessed Jul 20]. http://tarifazero.org/2012/12/03/toda-cidade-pra-todos/.

- MPL – Movimento Passe-livre. 2013. Não começou em Salvador, não vai terminar em São Paulo. In: Cidades Rebeldes: passe Livre e as manifestações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo; p. 28–43.

- Omena de Melo E. 2013. Changes and continuities in Brazilian urban governance; the impacts of sporting mega-events. Reviste Territorio. 64:34–38.

- Ortellado P. 2004. Sobre a passagem de um grupo de pessoas por um breve período da história. In: Ortellado P, Ryoki A, editors. Estamos Vencendo! Resistência Global no Brasil. São Paulo: Conrad.

- Pereira RHM, Schawanen T. 2013 February. Tempo de Deslocamento Casa - Trabalho no Brasil (1992-2009): diferenças Entre Regiões Metropolitanas, Níveis de Renda e Sexo. IPEA- Texto Para Discussão IPEA. 1813.

- Purcell M. 2012. Gramsci is not dead: for a ‘both/and’approach to radical geography. ACME: Int E-J Crit Geogr. 11(3):512–524.

- Rede Brasil Atual.2014. Obras de estádios da Copa tiveram 26 greves, aumentos reais e acordos avançados. Rede Brasil Atual, [accessedApril 9]. http://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/trabalho/2014/04/entre-2009-e-2013-trabalhadores-em-estadios-para-a-copa-tiveram-aumento-real-de-ate-7-35-1876.html.

- Rodrigues J 2013. Evolução da frota de automóveis da frota de automóveis e motos no Brasil (2001-2012). Observatório das Metrópoles, October. http://www.observatoriodasmetropoles.net/download/auto_motos2013.pdf.

- Saad-Filho A. 2013. Mass protests under ‘left neoliberalism’: Brazil, June-July 2013. Crit Sociol. 39(5):657–669.

- Sakamoto L. 2013. Em São Paulo o Facebook e o Twitter foram às ruas. In: Cidades rebel-des: passe Livre e as manifestações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo, p. 233–247.

- Santini RM, Silva D, Brasil T, Rezende R, Terra C, Traiano H, Seto K, de Orlandis M, Rescada C. 2017. Media and mediators in contemporary protests: headlines and hashtags in June 2013 in Brazil. Stud Media Commun. 13:259–278.

- Scherer-warren I. 2006. Das mobilizações às redes de movimentos sociais. Sociedade E Estado, Brasília. 21(1):109–130.

- Singer A. 2014 Jan-fev. Rebellion in Brazil: social and political complexion of the June events. New Left Rev. 85:19–37.

- Solano E, Manso BP, Novaes W. 2014. Mascarados: a verdadeira história dos adeptos da tática Black Bloc. São Paulo: Geração Editorial.

- Souza ML. 2012. Panem et circenses versus the right to the city (center) in Rio de Janeiro: A short report. City. 16(5):563–572.

- Touraine A. 1985. An introduction to the study of social movements. Soc Res (New York). 52:749–787.

- Ubide A. 2013 June 20. Protestos são reflexo de nova classe média. Estado de São Paulo.

- Vainer C. 2013. Cidades rebeldes: passe Livre e as mani-festações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil. In: Quando a cidade vai às ruas. 1 ed. São Paulo: Boitempo; p. 35–40.

- Veja.2013. Facebook alcança marca de 76 milhões de usuários no Brasil. Veja, [accessed Jul 30]. http://veja.abril.com.br/noticia/vida-digital/facebook-alcanca-marca-de-76-milhoes-de-usuarios-no-brasil.

- Verlinghieri E, Venturini F. 2018. Exploring the right to mobility through the 2013 mobilizations in Rio de Janeiro. J Transp Geogr. 67:126–136.