ABSTRACT

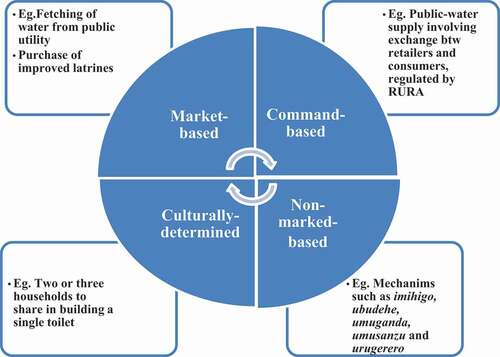

Inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) is a significant health burden in Rwanda. Although current approaches for improving water and sanitation provision to enhance health outcomes are often narrowly associated with monetary exchange, analysis of two informal settlements in Kigali (Gitega and Kimisagara) shows that households attempt to meet their water and sanitation needs through four interlinked exchange systems (market-based, command-based, culturally determined and non-market-based exchange systems). By focusing on existing social relations and exchange systems, sanitation practitioners may be able to foster and strengthen these interlinked water and sanitation marketing exchange systems embedding in the local context and local capabilities, and as a consequence improve the lives of the low-income communities of informal settlements.

Introduction

Diarrhoea is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide and, despite a downward trend in deaths attributed to diarrhoea, still claimed 1.4 million lives in 2010 (Lozano et al. Citation2012). Inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) is responsible for a major proportion of these deaths (Pfadenhauer and Rehfuess Citation2015). The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) estimates that 9% a safe water source and 32% of the world’s population do not use a safe sanitation facility (WHO/UNICEF Citation2015).

In Rwanda, the picture on improving household access to basic infrastructure and services is variable. Based on the National Strategy for Transformation (NST-1) as adopted in October 2017, households with access to an improved drinking-water source (excluding time and distance criteria) were estimated at 85% in 2017; approximately 84% of households use basic sanitation services (if some criteria such as sanitation facilities not being shared between households are excluded) (GoR Citation2017). Considering the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goal6 and according to the 2017 JMP Report, the percentage of households using basicFootnote1 drinking water services was estimated at 57% while 62% of households use basicFootnote2 sanitation services (GoR Citation2018b).

However, informal settlements, which are common in most Sub-Saharan African cities, face unique challenges with approximately 62% of the urban population live in informal settlements (Dinye and Acheampong Citation2013; Shah Citation2016). Informal settlements present a real challenge for achieving sustainable urban development and improved health and quality of life for urban residents. Part of this challenge includes dealing with the lack of basic sanitation facilities, and the consequent unhygienic disposal of human waste through means such as open defecation.

Rwanda has been experiencing a very high rate of population and urban growth. Urban growth is largely concentrated in the City of Kigali, which today accommodates about half of Rwanda’s urban population (Tsinda Citation2018; GoR Citation2018a). This has led to the proliferation of informal settlements, resulting in overcrowding, dilapidated housing conditions and environmental degradation. In Kigali, more than 60% of the urban population live in these settlements (GoR Citation2018a, Citation2018c) .

Provision of basic sanitation facilities and services in urban informal settlements in Kigali, as in other cities of low-income countries, however, is complex due to issues such as the allocation of responsibilities between landlords and tenants, insecure land tenure discouraging investment in sanitation, and differences in residents’ social backgrounds reducing social cohesion (Lüthi Citation2010; Simiyu Citation2017).

Previous research by the authors showed a disparity between supply and demand in the sanitation markets of informal settlements of East African Cities, including Kigali (Tsinda et al. Citation2015; Okurut et al. Citation2015; Tsinda and Abbott Citation2017). However, in low-income countries water and sanitation markets are multifaceted and can only be understood via analysis which goes beyond supply and demand in monetary terms. Market processes do not always involve a monetary transaction (Andreasen Citation1994) and are not conducted by a conventional buyer and a seller (Barrington et al. Citation2017). Instead, exchange in the marketing literature can be understood more broadly as a voluntary trade of something of value, with such exchanges including transactions undertaken via social currencies (such as caring for a friend when they are unwell) or via philanthropy (such donating to local charity) (Barrington et al. Citation2017).

Marketing research identifies a range of exchange partners and their motivations for participating in the market (Laczniak and Murphy Citation2012; Sridharan et al. Citation2015). This broader understanding of exchange suggests that water and sanitation markets can involve a multitude of exchange partners who interact via both monetary and non-monetary transactions to enhance health and wellbeing, through both the water and sanitation products and services exchanged, and an increase in social capital created by the exchange itself (Yip et al. Citation2007; Mohnen et al. Citation2011; Poortinga Citation2016).

This article builds on theories of social exchanges where exchanges are classified into four categories (Sridharan et al. Citation2015; Barrington et al. Citation2017): (i) market-based, ii) gift economy, gift culture or gift exchange (non-market-based), iii) command-based and iv) culturally-embedded. This framework, developed by Sridharan et al. and Barrington et al., was applied and adapted to the Rwandan context.

In a typical market-based exchange, goods and services are exchanged for primarily monetary value received (Tsinda et al. Citation2015). A market- based exchange allows a buyer to access goods or services while allowing the seller an opportunity to make an economic profit (Sridharan et al. Citation2015).

In a gift exchange, products (or services) are not formally traded or sold for money but instead are given without any explicit agreement of future reward (Kranton Citation1996; Cheal Citation2015). In the context of the water and sanitation the gift economy (or non-market exchange system) is often criticised because the recipients do not necessarily feel invested or have a full sense of ownership of the resulting water and sanitation supply solution (Marks and Jennifer Citation2012).

In a command-based exchange, a government owned authority provides goods and services as a result of a provision obligation set through legislation rather than profit motive (Sridharan et al. Citation2015). The provision obligation stems from the need to ensure the right to water and sanitation is upheld for the local population. However, command-based exchange systems have been criticised for providing people with a poor range of options, lacking recipient engagement in the planning process and a lack of responsiveness to changing needs and local conditions (Mitlin Citation2004). In the context of water and sanitation, examples of command-based exchanges include community boreholes or wells provided by the local government, large-scale water supply infrastructural projects and city-wide sewerage systems (Barrington et al. Citation2017).

In a culturally-determined exchange, the provider and recipient engage in an exchange transaction primarily governed by local social practices instead of by conventional economics (Thapar Citation1994; Belk Citation2014; Bisung and Susan Citation2014). The motivations for such exchanges are culturally rooted and based upon reciprocity and the local equitable redistribution of resources (Layton Citation2007). The result of such an exchange tends to be a collectively beneficial outcome instead of a purely individual gain (Layton Citation2007; Domegan et al. Citation2016). For example, in a household in an informal urban settlement may split its water bill with another household, reducing the fixed access costs for both households and thus make getting a water supply connection more affordable, while in a rural area a community-scale water system may be managed by a local committee seeking to ensure that all villagers have access to sufficient water (Sridharan et al. Citation2015).

It is against this background that this article applies a framework of water and sanitation marketing exchange systems based on the four types of exchange systems outlined above, in the context of the informal settlements of Kigali, Rwanda. The findings contribute to developing new insights into how the four exchange systems can be used to ensure water and sanitation provision is responsive to households’ needs and wants as societies move towards universal equitable access.

Method

Study area

The exchange systems framework was applied via a case study research approach to Kigali, the capital city of Rwanda, which has an estimated population of 1 million (World Bank Citation2017). There are a number of informal settlements around the city, with about 63% of the population of Kigali City still living in informal settlements (Tsinda et al. Citation2013).

Two informal settlements of the City of Kigali, Gitega and Kimisagara, were selected as research sites. The characteristics of these two may be summarised as follows: (i) high density of settlement, (ii) an unhealthy environment, (iii) unauthorised, poor housing, (iv) lack of access to quality transportation, (v) lack of access to quality health care, (vi) poor drainage systems, and (vii) poor sanitation facilities and services.

Data collection and analysis

In this study, a purposive sampling framework was used to select informants, using the same framework in both settlements. In-depth interviews and focus-group discussions (FGDs) were used to capture the informants’ perspective on different marketing exchange systems in water and sanitation. This article draws primarily on key informant interviews with officials from the Ministry of Infrastructure (MININFRA), the Water and Sanitation Corporation (WASAC), the Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Authority (RURA),Footnote3 officials of the City of Kigali District of Nyarugenge, Kimisagara and Gitega Sectors. T en FGDs with owner-occupiers (half female and half male) who were the head of households; two FGDs with community health workers; two FGDs with village leaders; and two FGD with service providers in the settlements, were conducted. The discussions were facilitated by two trained researchers and each group was deliberately limited to six to eight participants in order to facilitate meaningful interaction.

Finally, one-day workshop was arranged to seek the views of stakeholders on preliminary research outcomes and their insights into water- and sanitation-related marketing exchange mechanisms in the two settlements. The workshop was designed to bring together stakeholders and various interest groups, with participants being selected by purposive sampling. The workshop consisted of 15 participants representing residents (including owner-occupiers and renters of both genders), service providers from the settlements, local village leaders (one from each settlement), two district officials, one official from the City of Kigali and officials from WASAC, RURA and MININFRA. The above three qualitative research methods are seen here as complementary rather than alternatives.

All FGDs were conducted in Kinyarwanda (the local language) and were later translated into English. The key informant interviews and workshop were conducted in English with a little explanation in Kinyarwanda. Data from interviews, FGDs and workshop were recorded on audio devices, after which they were transcribed verbatim into Microsoft Word. These transcripts were then read multiple times in order to gain familiarity with the data.

Data analysis followed a thematic content approach. The main themes built on social exchange theories, classified into the four categories of the Framework: (i) market-based, ii) non-market-based, iii) command-based and iv) culturally embedded.

Before each interview, respondents were advised of the aims of the study and given time to make an informed decision on whether to participate. Ethical approval was given by the University of Rwanda (UR) Research Screening and Ethics Clearance Committee.

Findings

The findings show that, in two informal settlements of Kigali, water and sanitation products and services are supplied by all four types of exchange systems. Examples of these types of water and sanitation exchange system are shown in .

However, in practice the four exchange systems are not mutually exclusive and frequently co-exist in complementary ways. As identified by Sridharan et al. (Citation2015), these exchange systems can exist as interlinked systems which work together, or as a hybrid system. In the following sections, each exchange system is described (with practical examples), followed by a discussion of the complex system where all four exchange mechanisms work together and complement each other, so that the whole is greater than the parts.

Market-based exchange systems

‘The market’, for informal settlement residents in Kigali, refers to the small local hardware shops and informal service providers (e.g. informal emptiers, masons, pit diggers, etc.) serving the neighbourhoods.

Participants in the interviews, FGDs and workshop agreed that the following water and sanitation products and services are provided by the market-based mechanisms. These include: (i) water purchased from the public utility or from other households; (ii) ecosan model or semi-ecosan toilets and ventilated pit latrines (VIP) (or other latrine technologies); (iii) septic tanks; (iv) construction services and materials for upgrading existing sanitation facilities (e.g. from a pit latrine to an ventilated pit latrine, or adding a cement floor, door, etc.); (v) soap, (vi) simple hand washing equipment or Kandagira ukarebe.Footnote4

Command-based exchange systems

Although water is sold via a market-based transaction to households by individual sellers, the price of the transaction is regulated by RURA, a government regulatory authority. Thus, there is a command-based exchange between the retailer and the regulator, and a market-based exchange between the retailer and consumer, resulting in a hybrid command/market exchange for the overall transaction.

RURA is responsible for the day-to-day regulation and supervision of private operator licensing, adherence to minimum service standards, monitoring of agreed performance benchmarks and adherence to agreed tariffs (GoR Citation2016). Often, RURA cooperates with WASAC, with WASAC playing mainly a supporting role. Furthermore, user associations/committees are involved in the oversight arrangements, representing consumer interests and user rights, as set out in the contractual and regulatory arrangements.

Culturally-determined exchange mechanisms

Although not widely practiced, it has been observed that some households obtain access to an affordable sanitation facility by two or three households building a shared toilet on land adjacent to one of the houses or the nearest vacant land. This is important because the majority of owner-occupiers do not have the means to build individual private toilets, as was pointed out by a resident in Kimisagara (Kigali):

See how many kids I have, I lived here since 1980; this house has three rooms and I use all of them as bedrooms so there is no space available; fortunately I live in harmony with my neighbor and we have constructed a shared toilet in his area and we shared the cost because he is poor like me.

Even if shared toilets are not considered as improved sanitation, it is important to acknowledge that shared toilets are more affordable than individual household toilets and much better than open defecation. That is why some key informants suggest that shared sanitation is inevitable and that emphasis the should be placed on ensuring better standards, better cleaning and a reasonable number of households sharing a single toilet rather than every household having to have its own private toilet.

Non-market-based exchange systems

A number of stakeholders indicated during the workshop that some water and sanitation products and services are provided by non-market-based exchange mechanisms which are best described by their Rwandan names of imihigo, ubudehe, umuganda, umusanzu, urugerero (See .).

Concerning the above non-market-based exchange mechanisms, one representative of women in a village stated:

… .In very serious cases, some costs are covered by community contributions in various forms such as umusanzu whereby village leaders mobilise the community to support households who do not have toilets.

Similarly, some households also confirmed receiving support from their communities, as reported by one resident of Kimisagara:

We used to get labour and financial support from the family, good friends and good neighbours in the construction of houses and improved latrines.

For the poor households (especially the households in Category 1 of ubudeheFootnote5 who do not have toilets) the village leaders organise community members to build sanitation facilities.

Community work or umuganda, which is organised at the umudugudu or village level (lowest level of administration), is followed by ibiganiro (a local community meeting). This meeting is also important for disseminating information to citizens, including information on hygienic practices, with Community Health Workers (CHWs) explaining to people how they can keep healthy by such things as hand washing and keeping their toilets clean. It is generally seen as the responsibility of umudugudu’ village leaders to guide and encourage better-off households to support their neighbours who are poor (especially those in Category 1 in the ubudehe classification). About this, two participants in the workshop stated:

… In my village, our leaders used to sensitize us and raise funds to construct toilets for the very poor and vulnerable households especially older people, widows and orphans of genocide and the practice is now being imitated by our neighbours … (Female owner-occupier from Gitega, 2016).

At the community and household level, there is a need to try to leverage all local resources and mobilise whatever financial and human resources are available to construct home toilets such as exploiting the local expertise and labour of community members, family members, relatives and friends to provide assistance in the form of labour and materials for toilet construction (Official from MININFRA, 2016).

Volunteering and voluntary donations are also used to enable the construction of new toilets, the emptying of toilets once they are full, and the construction of Ventilated Pit Latrines (VIP) or other forms of sanitation recommended by the Government. Social support also takes other forms, such as a daughter or son helping an elderly parent to use a latrine, an individual helping his/her neighbour to build a toilet or a resident providing advice to his/her neighbour on how to empty their pit latrine.

Strengthening interlinked marketing exchange systems

These water and sanitation marketing exchange systems are interlinked. As was often mentioned by the participants in the workshop, the traditional practices are hybridised with market-based exchanges to ensure that community members have access to water and sanitation. Traditional mechanisms have been adopted into the administrative system to assist with the implementation of national policies and targets within a decentralized structure.

The community support through traditional practices take two forms: firstly two or three residents come together and build a latrine to share, and secondly the community at village level and the diaspora organise to contribute finance and labour to build facilities for the very poor and other vulnerable households.

Village leaders organised collecting voluntary financial contributions and labour is provided by community members either as part of umuganda (compulsory community work) or the Vision 2020 Umurenge Programme (a social support programme which boosts the incomes of the poorest members of the community by funding public works).

These traditional practices and programmes build and enforce the idea of collective action, cooperation and mutual assistance. This demonstrates how the state skilfully draws on the traditional repertoires of local forms of organizations in order to address the developmental issues, including sanitation improvement.

Rather than promoting one-size-fits-all water and sanitation marketing approaches, the approach adopted in Kigali suggests it can be more useful to recognise the resourcefulness with which ‘hybrid’ exchange modes are developed and applied in the city’s informal settlements. The leveraging of social capital to enable the exchange of water and sanitation products and services leads to an improvements in hygienic practices. This has also been reported in other settings (Bakshi Rejaul et al. Citation2015, Venugopal and Madhubalan Citation2015).

The mixing of market-based exchanges together with alternative forms of exchange coupled with an understanding and concern for the well-being of the vulnerable (poor households, widows, people with disabilities, etc.) is consistent with recent research findings on the informal settlements of East Africa cities more generally (Tsinda et al. Citation2017; Tsinda and Abbott Citation2017).

However, the results here are informative because although water and sanitation market exchanges are triggered by the need to generate survival income, implementation occurs in a humanistic way whereby people support each other through command-based exchange approaches (e.g. local authorities persuading better-off households to support their neighbours) and/or culturally-embedded exchange approaches (e.g. urugerero, enabling young people following the completion of secondary schools to construct houses and sanitation facilities for vulnerable households).

The research findings also show the complexity of marketing water and sanitation services delivery, because elements are provided by the public sector as a universal right/subsidised but households also remain responsible for purchasing some services on the open market. These findings suggest that in the context of developing water and sanitation marketing approaches the dichotomy of purely profit-driven water service delivery on the one hand or community driver delivery on the other is unlikely to be accurate and therefore not useful in practice. By leveraging the varied hybrid exchange practices which exist, WASH practitioners can improve the water and sanitation provision to more sustainably meet the needs of local communities.

In the interviews with local leaders, it was stressed that social support could not be taken for granted. The participants described a mixed picture of erosion and consolidation of social support under difficult economic conditions. The evidence suggests that where households are linked by monetary exchanges, such as being a member of revolving fund,Footnote6 social support has been strengthened. However, although the very poorest cannot afford to save and therefore cannot benefit directly from membership of revolving funds, the benefits of revolving funds in the context of the case-study settlements of Kigali go beyond monetary exchange and create a collective sense of working together and dealing collectively as a group with daily life issues. This collective approach is useful, as sanitation issues cannot only be solved by an isolated individual – the whole community needs to be involved.

Conclusion

The case study of Kigali reveals that the above diverse range of exchange mechanisms used to acquire WASH products and services

do not occur in isolation; they are integrated and interlinked, with consumers using multiple forms of water and sanitation marketing mechanisms. While these exchange systems exist as interlinked systems which work together, or as a hybrid system, it is clear that the cultural exchange behaviours are dominant in Kigali and work quite well. Therefore, water and sanitation exchange systems should be designed to generate innovative exchange pathways that are economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable in their local context.

However, even if mixed systems exist in other East African cities, the exact practices used in Rwanda would not necessarily work elsewhere because social and political economy conditions differ from country to country, and city to city; what works in one country or one city in Eastern Africa will not necessarily work elsewhere. This suggests that further research is required to determine the extent to which practices adopted in Rwanda apply elsewhere.

The way ahead

It is widely recognised that savings and loans clubs work well in low-income countries in Eastern Africa. The Kigali settlements studied here have been relatively successful in improving water and sanitation with minimal financial resources from the government and in ways that have proved to work for them because the principle of ‘good fit’ rather than ‘best practice’ solutions have been applied (Booth and Cammack Citation2011; Booth and Golooba-Mutebi Citation2012). This implied a real commitment to ‘working with the grain’, meaning adopting solutions which are well adapted to local contexts and build on existing institutional arrangements that are known to work on the ground and a shift from direct support to facilitating local problem-solving processes (Cammack Citation2012).

Acknowledgements

This article was drafted as part of a Post-Doctoral Grants (Post-doc) Scheme through the University of Rwanda, UR-Sweden Programme of Research, Higher Education and Institutional Advancement, which was funded by the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA). The authors would like to thank SIDA and the University of Rwanda for the support provided.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aime Tsinda

Aimé Tsinda is a Senior Lecturer of Urban Planning and Environmental Sustainability at the University of Rwanda. Dr. Tsinda holds a PhD in Environment& Sustainability with dissertation in urban sanitation in Kigali (Rwanda), Kampala (Uganda) and Kisumu (Kenya), University of Surrey, UK, and a Master’s Degree in Urban Planning from the University of Montreal (Canada) with a dissertation in Disaster Risk Management (DRM) in the City of Kigali. He researches on policy analysis, urbanization, WASH, environment, sustainability, climate change and natural resource management.

Jonathan Chenoweth

Jonathan Chenoweth completed his PhD at the University of Melbourne in 2000 before working as a researcher in the Middle East and then the UK. He is a Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Surrey where he directs the Masters teaching in his department and researches on water resources management and sustainable development. His research focuses on water and sanitation provision in peri-urban settlements, consumer attitudes to water supply services and the water industry, and the adaptation of water resources management to the effects of climate change.

Pamela Abbott

Pamela Abbott is Director of the Centre for Global Development and Honorary Professor of Sociology, University of Aberdeen. Abbott's recent research interests focus on urban sanitation, quality of life and socioeconomic transitions in societies experiencing transformations following the Arab Spring. In her writings on feminist perspectives in sociology, Abbott challenges a limited consideration of gender issues within mainstream sociology and advocates a reconceptualization and interdisciplinary approach in order to question fundamental assumptions in the discipline.

Notes

1. According to SDGs, households using basic drinking water services are defined as ones using drinking water from improved water source where the collection time is not more than 30 minutes for a roundtrip including queuing.

2. According to SDGs, households using basic sanitation services are defined as those using improved sanitation facility which is not shared with other households.

3. It is important to give a brief explanation of the roles and responsibilities of the above three key national institutions: (i) MININFRA is a ministry responsible for the development of policies and regulations regarding sanitation, water, urbanisation (including informal settlements) and housing, (ii) WASAC is a national entity set up to manage the water and sanitation services in Rwanda, (iii) RURA is a government agency with a mission to regulate certain public utilities, including water, sanitation, energy, etc.

4. The Step and Wash (Kandagira ukarabe), is a simple hand washing equipment where a small jar or container with clean water is positioned at the top and connected to a peddle that exerts pressure open the flow of water from the container.

5. See for an explanation of the ubudehe socio-economic categories.

6. This refers to informal financing mechanisms consisting of groups of individuals who make regular contributions to a common fund from which these individuals are in turn able to borrow money to pay for sanitation (Chatterley et al. Citation2013).

References

- Andreasen Alan R. 1994. Social marketing: its definition and domain. J Public Policy Marketing. 13:108–114.

- Bakshi Rejaul K, Debdulal M, Mehmet A. 2015. Social capital and hygiene practices among the extreme poor in rural Bangladesh. J Dev Stud. 51(12):1603–1618.

- Barrington DJ, Shields SG, Saunders S, Sridharan RT, Bartram J. 2017. Some lessons learned from engaging in WaSH participatory action research in Melanesian informal settlements. In: WEDC knowledge base. 40th WEDC International Conference, 24–28 July 2017, Loughborough, UK.

- Belk R. 2014. You are what you can access: sharing and collaborative consumption online. J Bus Res. 67:1595–1600.

- Bisaga I, Priti P, Yacob M, Yohannes H. 2018. The potential of performance targets (imihigo) as drivers of energy planning and extending access to off grid energy in rural Rwanda. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. e310; [accessed 2018 Dec 24]. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wene.310

- Bisung E, Susan J. 2014. Toward a social capital based framework for understanding the water-health nexus. Soc Sci Med. 108:194–200.

- Booth D, Cammack D 2011. Governance for development in Africa. Policy Brief, Africa Power and Politics Programme, UK Department for International Development, London (UK).

- Booth D, Golooba-Mutebi F. 2012. Developmental patrimonialism? The case of Rwanda. Afr Aff (Lond). 111:379–403.

- Cammack D 2012. Support to local problem-solving: lessons from peri-urban Malawi. Africa Power and Politics Programme (APPP), Overseas Development Institute, London (UK).

- Chatterley C, Gonzalez O, Sparkman D, Sugden S, Lemme K, Dorsey S. 2013. Microfinance as a potential catalyst for improved sanitation: A synthesis of Waste Lending Experience in Seven Countries. Denver CO, Water for People.

- Cheal D. 2015. The gift economy. Routledge library editions: social and cultural anthropology

- Dinye R, Opoku Acheampong E. 2013. Challenges of slum dwellers in Ghana: the case study of Ayigya. Kumasi. Mod Soc Sci J. 2:228–255.

- Domegan C, McHugh P, Devaney M, Duane S, Hogan M, Broome LR, Joyce J, Mazzonetto M, Piwowarczyk J. 2016. Systems-thinking social marketing: conceptual extensions and empirical investigations. J Marketing Manage. 32:1123–1144.

- GoR. 2016. National water supply policy. Kigali: Ministry of Infrastructure.

- GoR. 2017. National strategy for transformation (NST1)-social pillar chapter. Kigali: Office of the Prime Minister & Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning.

- GoR. 2018a. Urbanisation and rural settlement sector strategic plan (2018–2024). Kigali: Ministry of Infrastructure.

- GoR 2018b. Water and Sanitation 2018/2019 Forward Looking Joint Sector Review Report. Kigali: Ministry of Infrastructure.

- GoR. 2018c. Water and sanitation sector strategic plan (2018–2024). Kigali: Ministry of Infrastructure.

- Kalisa T 2014. Rural electrification in Rwanda: a measure of willingness to contribute time and money. GATE Working Paper No. 1413. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2412519.

- Klingebiel S, Victoria G, Franziska J, Miriam N. 2016. Case study: imihigo—A traditional Rwandan concept as a RBApp. In: Public sector performance and development cooperation in Rwanda. Springer International Publishing ; p.41–73, Palgrave macmillan.

- Kranton RE. 1996. Reciprocal exchange: a self-sustaining system. Am Econ Rev. 86(4):830–851.

- Laczniak GR, Murphy E. 2012. Stakeholder theory and marketing: moving from a firm-centric to a societal perspective. J Public Policy Marketing. 31:284–292.

- Layton RA. 2007. Marketing systems—A core macromarketing concept. J Macromarketing. 27:227–242.

- Lozano R, Mohsen N, Kyle F, Stephen L, Kenji S, Victor A, Jerry A, Timothy A, Rakesh A, Stephanie YA. 2012. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 380:2095–2128.

- Lüthi C, Jennifer M, Kvarnström E. 2010. Community-based approaches for addressing the urban sanitation challenges. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 1:49–63.

- Marks J, Jennifer D. 2012. Does user participation lead to sense of ownership for rural water systems? Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 40:1569–1576.

- Mitlin D. 2004. Competition, regulation and the urban poor: a case study of water. Chapters, in: Paul Cook & Colin Kirkpatrick & Martin Minogue& David Parker (ed.)., Leading issues in competition, regulation and development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing; p. 320–338.

- Mohnen SM, Groenewegen P, Völker B, Henk F. 2011. Neighborhood social capital and individual health. Soc Sci Med. 72:660–667.

- Nzahabwanayo S. 2018. What works in citizenship and values education: attitudes of trainers towards the Itorero training program in post-genocide Rwanda. Rwandan J Educ. 4:71–84.

- Okurut K, Nakawunde Kulabako R, Chenoweth J, Charles K. 2015. Assessing demand for improved sustainable sanitation in low-income informal settlements of urban areas: a critical review. Int J Environ Health Res. 25:81–95.

- Oyamada E. 2017. Combating corruption in Rwanda: lessons for policy makers. Asian Educ Dev Stud. 6:249–262.

- Pfadenhauer LM, Rehfuess E. 2015. Towards effective and socio-culturally appropriate sanitation and hygiene interventions in the Philippines: a mixed method approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 12:1902–1927.

- Poortinga W. 2016. Social relations or social capital? Individual and community health effects of bonding social capital. Soc Sci Med. 63:255–270.

- Shah N 2016. Characterizing slums and slum-dwellers: exploring household-level Indonesian data, Irvine, University of California, Social Science Plaza Irvine.

- Simiyu S. 2017. Preference for and characteristics of an appropriate sanitation. technology for the slums of Kisumu, Kenya. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 9:300–312.

- Sridharan S, Barrington J, Saunders SG. 2015. Water exchange systems. In: Bartram, J, (ed.). Routledge handbook of water and health. London, UK, pp 498–506.

- Sundberg M. 2016. Rwanda and Rwandans in the post-genocide political imaginary: Training for model citizenship, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p.63–98

- Thapar R. 1994. Cultural transaction and early India: tradition and patronage, Delhi, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tsinda A. 2018. Affordable housing in Kigali: issues and recommendations. In Kigali: Institute of Policy Analysis and Research (IPAR-Rwanda).

- Tsinda A, Abbott P. 2017. Between the Market and the State: financing and Servicing Self–Sustaining Sanitation Chains in Informal Settlements in East African Cities. Working Paper 1, Centre for Global Development, University of Aberdeen. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2951915.

- Tsinda A, Abbott P, Chenoweth J. 2015. Sanitation markets in urban informal settlements of East Africa. Habitat Int. 49:21–29.

- Tsinda A, Abbott P, Chenoweth J, Pedley S, Kwizera M. 2017. Improving sanitation in informal settlements of East African cities: hybrid of market and state-led approaches. Int J Water Resour Dev 34(2): 229–244. .

- Tsinda A, Abbott P, Pedley S, Charles K, Adogo J, Okurut K, Chenoweth J. 2013. Challenges to achieving sustainable sanitation in informal settlements of Kigali, Rwanda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10:6939–6954.

- Usengumukiza F. 2015. Governance for development: the case of Rwanda. In. Kigali: Rwanda Governance Board.

- Uwimbabazi P 2012. An analysis of umuganda: the policy and practice of community work in Rwanda [dissertation]. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

- Venugopal S, Madhubalan V. 2015. Developing customer solutions for subsistence marketplaces in emerging economies: a bottom–up 3C (customer, community, and context) approach. Customer Needs Solutions. 2:325–336.

- WHO/UNICEF. 2015. Progress on drinkingWater and sanitation: 2015 Update. In. Geneva: World Health Organisation/United Nations Children’s Fund.

- World Bank. 2017. Note1: urbanization and the evolution of Rwanda’s urban landscape. In. Washington World Bank.

- Yip W, Subramanian AD, Mitchell D, Dominic TS, Jian Wang L, Ichiro K. 2007. Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China. Soc Sci Med. 64:35–49.