ABSTRACT

Land provision for low-income housing in sub-Saharan African cities generally and Lusaka specifically, is a significant challenge faced by planners and city managers, evidenced in the high prevalence of squatter settlements. As part of the solution to the problem of informal settlements, the paper has developed a set of recommendations for providing access to peri-urban lands under customary law for private commercial low-income housing, to reduce the need for informal housing in statutory urban areas. The set of recommendations were developed by exploring the necessary governance processes in the allocation of customary land using a partnership approach.

Introduction

Zambia is a land abundant country, in spite of the availability, people have difficulties in accessing land in urban areas. The access problem contributes to informal housing developments and is more severe in Lusaka, the capital city which has 70 percent of the population living in informal settlements (see UN-Habitat Citation2012). In view of the informal housing growth problem, policy intervention measures have included relocations, site and service schemes and squatter upgrading programmes, but these have failed to effectively deal with the informal growth problem for various reasons. Relocation may give residents access to roads, water pipes, drains and sewers in the new location but is rarely a sustainable solution. Studies indicate that removing squatters from preferred residences does not solve the problem because the places are socio-spatially connected with the relocatees’ sources of income, relatives and friends. Consequently, most relocatees either return to former settlements or start new ones in locations close to income sources, relatives and friends (Viratkapan and Perera Citation2006; Gebre Citation2014).

Site and site scheme involves provision of plots to reduce the need for informal housing, which can fail for several reasons such as high commuting costs to employment and service areas, unpopular predesigned building plans and costs which compel beneficiaries to gentrify (Hansen Citation1997). With reference to squatter upgrading, the aim is provision of on-site services and tenure security to people already in informal settlements with minimal disturbance to livelihoods. However, research indicates this approach has several shortcomings, key among them, upgrading can result in a process of ‘down raiding’ in which higher income groups attracted by the secure status and access to services move into the settlement pushing up prices and displacing more vulnerable low-income groups. This paper contends that these approaches fail because they treat the symptoms and not the root causes. In other words, the rise in informal growth is seen as a failure by governments to develop enabling housing delivery frameworks, in which a durable solution rests. For example, the provision of tenure security to squatters is a reactive response to the informal housing processes and not proactive response or preventive measure in the sense of precluding the land access constraints which prompt people to settle informally.

Many informal housing analysts such as De Soto (Citation1989), Fox (Citation2014), Home (Citation2015), Payne and Majale (Citation2004) and Tannerfeldt and Ljung (Citation2006) hold a similar view who have stated that informal housing is a strategy by the deprived for gaining access to land and housing which cannot be reached by using the formal route. They see the governance systems to be very exclusionary and their existence just serves to entrench the informal housing sector since low-income groups compensate for the lack of state-supported affordable housing delivery frameworks. In this respect, the paper highlights the importance of devising responsive land delivery frameworks. Contextually, the root of the land access problem is perceived to lie in the statutory and customary land tenure structure. A brief historical background to this land tenure structure is that prior to colonialism land was communally owned and governed by chiefs who did not tolerate private ownership. Colonialism brought with it a land governance system (statutory) based on formal planning and individual ownership, which applied to areas used by European settlers (known as crown lands), which were mainly urban areas. The rest of the land was left for the African communities as customary areas (Chitonge and Mfune Citation2015; Mushinge Citation2017). According to the Ministry of Local Government and Housing (Citation2008) document for the preparation of the urban and regional planning bill, the reason for this exclusion of reserved land under customary law from the planning system was because the underlying land tenure system was seen as inimical to the way in which a ‘modern’ planning and land titling system worked. This type of governance which permitted chiefs to exercise authority over customary areas has continued in several post-colonial African countries including Zambia with implications on land access and affordable housing delivery. The land tenure structure which is skewed to customary ownership creates artificial land scarcity, that is, though geographically land is available, it is not accessible for urban expansion, which includes more housing and supportive infrastructure development. The inability to expand is contributing to densification with the consequent problems of high accommodation rentals which compel those priced out of the formal housing market to turn to the informal housing sector.

Statutory private land titling is modelled on the English land law doctrine of tenures and estates which vests absolute ownership in the monarch. The difference with the Zambian situation is that absolute ownership is vested in the republican president who through the provisions of the leasehold doctrine, the state offers persons up to 99-year exclusive possession of land in return for periodic rent. The customary land tenure system vests stewardship in traditional leaders (chiefs), who give subjects unrestricted use rights, without title deeds. Land administration under this category does not tolerate exclusive rights in land, that is, no single person can claim to own land, as the whole land belongs to the community. Given that customary land governance does not tolerate private ownership, this paper is concerned with developing a conceptual and practical land delivery framework for providing access to peri-urban lands under customary law for private commercial low-income housing, to reduce the need for informal housing in statutory urban areas.

The necessity for the framework is supported by empirical studies that indicate customary land tenure is not very receptive to commercial land developments for reasons of territorial shrinkage and cessation of communal land ownership rights (Adams, Citation2003; Brown Citation2003; Mudenda Citation2006). The studies show that when customary land is acquired for commercial developments and related purposes, buyers convert it into statutory private holding to secure tenure. In short, the status changes from communal to statutory private ownership. Since land symbolises power, conversions diminish customary authority. Moreover, according to Brown (Citation2003), whenever conversion takes place, the law starts to exercise a strong legal binding power by defending the private rights of the new owners. In other words, conversions turn inhabitants into squatters. From the foregoing, it is clear that the solution to the access problem lies in devising a land delivery framework which meets the twin goals of providing access to peri-urban lands for low-income housing and preservation of communal land tenure. To this end, the aim of this paper is to explore opportunities for facilitating access to land for low-income groups by developing the governance processes in the allocation of customary land through a partnership approach.

In terms of structure, the paper has seven sections, including the introduction. Section 2 presents the theoretical framework of the study― it discusses the value of partnership approach and the principles and processes of good governance and how they create new possibilities of improving customary land allocation for low-income groups. Section 3 gives background information on the city of Lusaka, the case study area. Section 4 describes the research methods used for filling the identified gaps in the literature used to develop the framework. Section 5 presents the findings which are discussed in section 6. Section 7 provides the conclusion drawn from the study.

Developing the framework using the partnership model and good governance principles

The paper views partnership as the ideal tool for improving customary land allocation on account of the following attributes. First, by definition partnership is, ‘voluntary and collaborative relations between various parties, both State and non-State actors in which all participants agree to work together to achieve a common purpose or undertake a specific task and to share risks and responsibilities, resources and benefits’ (UN General Assembly Citation2005, p. 4). A large body of literature indicates that in the past three decades, the world has experienced a shift in urban governance, away from public sector towards the private sector as well as a shift towards sharing tasks and responsibilities (see for example Elander Citation2002). Therefore, partnership is ideal in the sense of being a means for reconciling the demands of private and communal forms of ownership (Pike et al. Citation2006; Bull and McNeill Citation2008). In this particular case, since loss of territory and dispossessions are the major land conversion concerns, a significant attribute of partnership approach is engagement of a private or government institution to finance, build and operate housing and auxiliary facilities without a customary authority losing land ownership right.

Second, attracting large-scale private sector investments in low-income housing and improving living conditions is considered by some commentators to be best achieved through public–private partnership (PPP) oriented collaborations. Chang (Citation2009, p. 723) provides a good explanation which states that: ‘the rationale behind engaging in public–private partnerships seems quite clear: The private sector typically has access to upfront capital and a track record of delivering products efficiently, while the public sector controls the regulating environment, and at times, crucial resources needed to implement a project … ’ Though in some exceptional cases customary lands can be accessed by private commercial developers acting alone and this can be highly beneficial in the sense of acquiring significant areas at low costs. However, studies show that they do not usually generate conditions that incentivise long-term investments and functional housing markets for the following reasons: generally customary lands have no planning standards to regulate use; they are rudimentary planned and managed, that is, decisions to do with the type of land an applicant can be offered, how it can be offered, for what purpose and what size are not based on formal guidelines. Moreover, the haphazard nature of development discourages private commercial developers from investing in peri-urban areas in preference for state-administered lands, a situation which generates excessive land demands and speculations and the ultimate pricing of the low-income groups out of the formal housing market system (Lusaka City Council Citation2008; UN-Habitat Citation2012). On the other side of the equation, some commonly noted positive characteristics of PPP are that the private sector is generally innovative, enterprising and efficient. These qualities when combined with the public (government) sector features like setting regulations, policies and municipal service provisions make PPP a good approach to the improvement of customary land markets. Third, partnership is an institutional form that involves collaboration not only between governmental and private institutions but also between non-governmental and governmental institutions to improve the lot of the world’s poor (Bull and McNeill Citation2008) such as those examined in this paper, which can be formed to provide resources and services or facilitate land provision for low-income housing delivery.

Though partnership is the ideal approach to the issue, actualisation is not free from challenges. Several scholars who include Elander (Citation2002), Xie and Stough (Citation2002), Farlam (Citation2005) and Bull and McNeill (Citation2008) see partnership as a complex undertaking which requires appropriate governance processes to actualise. By implication, for partnership to function as a vehicle for delivering customary lands, this points to the need to develop the necessary framework. This observation raises the central question which the paper explores: what are the necessary governance frameworks and processes that can facilitate access to peri-urban lands under customary tenure for low-income housing using a partnership approach? In response to this question, partnership being a governance tool, the paper draws on the good governance principles to guide the exploration of the processes. The principles drawn upon in developing the model are rule of law, effectiveness and efficiency, equity and inclusiveness, responsiveness, participation, consensus, accountability and transparency. The principles are drawn from the World Bank (Citation1992), UN-Habitat et al. (Citation2013), and several individual authors such as Rhodes (Citation1996) and Stoker (Citation1995).

Rule of law

This principle is about governing the public by law – it states that to rule in accordance with people’s needs and wishes require enactment of laws based on frameworks which are impartial, fair and enforceable (World Bank Citation1992; UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013). To put this principle’s significance in perspective, several studies attribute non-compliance with urban development regulations which result in informal growth to unsuitable rules (see, for example, De Soto Citation1989; Payne and Majale Citation2004; Tannerfeldt and Ljung Citation2006). Though regulations are vital since they provide guidelines and checks and balances in carrying out housing development, for orderly development to prevail, the regulatory framework should be responsive to local needs and conditions. Hernando De Soto (Citation1989), a Peruvian economist well known for his work on the informal economy and on the significance of business and property rights, explains informal growth and resilience as an adaptation response to regulatory ‘adversities’. He argues that developers are forced into informal housing through the necessity to meet the basic requirements of housing production. Equally Payne and Majale have noted:

Where a small proportion of the population fail to conform, it is reasonable to interpret this as a bad reflection on that particular group. When the majority of the population do not conform it is equally reasonable to conclude that it is bad reflection of the rules and regulations to which they are being expected to conform. (Payne and Majale Citation2004, p. 33).

By implication, the authors are contending that the regulations by which developers are ruled are the problem and not the people. Therefore, as Payne and Majale (Citation2004, p. 6) have argued: ‘ … to be enforceable, rules need to command local acceptance and legitimacy’, by developing enforceable rules and regulations, the application of this principle is critical to preventing peri-urban lands from facing similar problems.

Effectiveness and efficiency

The principles of effectiveness and efficiency among others stress upholding of technological innovations at all levels of development initiatives to achieve environmental, social and economic sustainability (World Bank Citation1992; UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013). To contextualise the principles’ significance, research has shown that the emphasis put on formal materials inhibit innovations in building technology, of cheaper stronger, versatile more durable and socially acceptable materials (Hadjri et al. Citation2007; UN-Habitat Citation2012). According to the UN-Habitat, exclusion of traditional building materials which is motivated by health and safety concerns can result in the construction of less durable informal housing. Hadjri et al.’s study of the potential of earth building to deliver affordable and durable housing in Zambia concludes that:

Zambia presents an interesting case study given the urgent need for low-cost urban housing, the historical use of earth building in rural areas, and the lack of dissemination of studies on traditional construction technologies and their potential to deliver affordable and durable housing (Hadjri et al. Citation2007, p. 141).

This study on earth building for housing provisions establishes that earth materials provide a number of environmental advantages, other than financial benefits in terms of affordability. Some of the established environmental benefits include fire resistance since earth contains good thermal insulating properties for humid countries like Zambia, as it balances humidity and absorbs pollutants unlike buildings made from conventional materials. The study cites Baggs (Citation1992) who reports that ‘a 250 mm thick compressed earth wall has an embodied energy 23 times less than an equivalent 270 mm double skin clay fire brick’ (p143). Other than energy saving, the study establishes that its production (that is, unbaked earth building) requires less heating and cooling. Besides, earth has been established to be very ‘versatile and can be used to reflect architectural diversity; it also offers a means of providing easily extendable or altered housing for all types of households’ (p143). By allowing developers to use traditional building materials that are affordable and have a long and acceptable history in local architecture, the application of these principles is critical to promotion of sustainable development.

Equity and inclusiveness

Equity and inclusiveness principles are about ensuring that all members of a given society feel they have a stake in available resources and services (UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013). This is particularly applicable to the most vulnerable, to improve their wellbeing. To put the significance of these principles into perspective, research on informal housing in various African countries show, many dwellers prefer to build formally but are constrained by financial difficulties. The studies show two broad origins of the financial constraints which are fiscal and property titling policies. Fiscal policies in respect of their negative influence on housing delivery concern unfavourable mortgage access conditions to most low-income developers (Tannerfeldt and Ljung Citation2006; Gardner Citation2007; UN-Habitat Citation2012). Property titling is a constraint in the sense that lending institutions demand collateral in form of land with title deeds or a house with a valuation report, which are not easy or cheap to obtain in many African countries including Zambia. This constraint compels most developers to have a preference for the informal housing delivery system. Similarly, on the supply side, research on the availability of low-income housing development finance in Lusaka revealed that ‘ … the high transaction costs an institution incurs makes dealing with this category of customers not profitable’ (Kangwa Citation2007, p. 22). The lesson drawn from this study is that lending institutions concentrate on high-income clients because they have the ability to provide alternative collateral. The factors that constrain access to formal housing finance are summarised in .

Figure 1. Housing finance and land titling influences on informal growth

Access to finance and title deeds are only part of the concerns; most low-income developers are employed in the informal economy that provide low wages, and so do not qualify for formal mortgage loans. On top of that, the informal nature of enterprises which are not backed with financial records presents difficulties to financial lenders, in terms of applicant suitability assessment in meeting collateral conditions or instalment payments in instances where a mortgage is granted. In this connection, the application of these principles is critical to addressing the problems of housing finance eligibility, affordability and inadequate service provision in peri-urban areas.

Responsiveness

This principle requires institutions to design their service delivery systems in ways that serve vested interest groups timely (World Bank Citation1992; UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013). To put the pertinence of this principle in perspective, research on informal settlements in several African countries indicate most people develop informally due to complex land registration procedures (De Soto Citation1989; Payne and Majale Citation2004; Rakodi and Leduka Citation2004). De Soto sees the informal settlement as an invisible revolution and grassroots uprising against the bureaucracies of state planning. Home and Lim (Citation2007) and Rakodi and Leduka (Citation2004) attribute informal housing developments to the side-lining of indigenous land administration practices, which are free from bureaucratic procedures. To this end, the application of this principle is critical to making land delivery processes cheap and procedurally simple.

Participation

This principle concerns processes that allow involvement of vested interest groups in governance affairs (World Bank Citation1992; Pierre Citation2000; Peterman Citation2000; UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013). According to Peterman (Citation2000), participation makes governance processes inclusive and democratic. For Pierre (Citation2000), recognition of different actors as active subjects and according of respect to diverse opinions make decision-makers treat participants involved in governance processes as a subject and not as an object. To put the significance of this principle into context, research has shown that the vesting of customary land stewardship in traditional leaders limits the participation of subjects on land governance matters. Exclusion begets land wrangles and related conflicts because some decisions are not made for the good of local communities (Brown Citation2003; Mudenda Citation2006). The application of this principle is critical to involvement of subjects in land allocation processes and partnership activities either direct or indirectly through appropriate intermediary bodies or agents.

Consensus

Abbott (Citation1996) and Stoker (Citation1995) describe consensus in urban governance as a group decision-making process in which members develop, and reach agreement to support a resolution in the best interest of a common goal. Consensus-oriented policy-making which is about finding mutual ground and making resolutions acceptable to all differs to the majority voting approach, in that, decisions are arrived at in a dialogue amongst equals, who acknowledge each other’s equal rights, and who take each other seriously. To contextualise this principle’s importance, customary land administration is superintended by leaders who are not elected officials who have the prerogative of decision-making, meaning the term voting is not part of the governance ‘vocabulary’. This management system differs with municipal or central government decision-making system which is superintended by elected representatives who settle differences or resolve contentious issues by means of majority voting. These socio-political differences make consensus the best approach to developing and reaching mutually acceptable agreements and resolutions.

Accountability

The accountability principle concerns recognition and shouldering of actions. This encompasses the obligation to report, explain and to be answerable (World Bank Citation1992; Stoker Citation1997). Several other authors that include Fung and Wright (Citation2001) and Pike et al. (Citation2006) who have explained the significance of this principle from local development and public sector management perspectives, contend accountability is essential in that it provides a democratic means for monitoring and regulating the conduct of officials tasked with the responsibility of managing public affairs, to prevent abuse of authority. The contextual application of this principle is that customary land governance system bestows traditional leaders with management powers; a drawback associated with this kind of approach to land governance is the allocation processes in many cases lack accountability. Studies have shown that the authority given to traditional leaders to allocate land in many cases is misused, i.e. land allocation actions or decisions are not done in accountable ways (Brown Citation2003; Mudenda Citation2006). This makes accountability a critical element of the governance system to prevent abuse of authority.

Transparency

Transparency means that decisions taken and their enforcement are done in a manner that follows rules and regulations. It also means that information is freely available, directly accessible and provided in easily understandable forms to those who will be affected by the decisions and their enforcement (World Bank Citation1992; UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013). Contextually, the free flow of information and the means of dissemination are essential to ensure land allocation decisions and compliance is done according to the laid down rules and regulations which require or prohibit certain behaviour for various purposes like safety or environmental protection. Payne and Majale (Citation2004) assert that the drafting of regulations in manners only comprehensible to professionals contributes to development of informal settlements because it makes it impossible for the general public to understand what is expected of them. This means the regulations should be provided in understandable forms. In addition, other studies indicate that a functional real estate market depends on the information and communication system that shapes the decision-making and transaction environment. To expand on this, according to Berry and McGreal (Citation1995) and Schuster (Citation2005) the significance of information lies in making buyers to be aware of the land or housing products and prices, and sellers aware of the offers made by buyers in order that both can make rational market decisions. The application of this principle is critical to making peri-urban land markets under customary tenure work more efficiently, by for instance, ensuring a land registration system that is accessible to the public is put in place.

Impediments and challenges to actualising the model

The discussion on how the good governance principles can be used to actualise partnerships has not exhaustively dealt with the following three governance issues. The first issue is that partnerships owe their existences in great part to engagements and collaborations of state and non-state actors at various levels (see Pike et al. Citation2006). In this connection, the ideologies that underlie the two land governance approaches are a potential obstacle to partnership formations. Statutory form of governance adopts private land rights as a means of encouraging housing investments. In contrast as already stated above, customary form of governance vests land stewardship in traditional leaders who give subjects unrestricted use rights without title deeds. Statutory form of governance which is followed by government institutions (to a large extent also by corporate bodies) is guided by formal rules and regulations. This differs with the customary governance system which is largely based on unwritten rules or informally recorded agreements. This difference is a potential impediment to meaningful engagements and collaborations. This concern raises the following question: what governance approaches can promote and consolidate engagements and collaborations? The answer to this question requires an empirical research to inform on the strategies for making the key players engage and collaborate.

Second, the ‘top-down’ nature of customary governance system which concentrates power in traditional leaders is an affront to participation, a significant element of partnership. An absence of community participation in partnership management implies self-representation of chiefs, which risks turning partnerships into tools of exploitation. This possibility is well explained by Pike et al. (Citation2006) who has observed partnerships often exclude the very group at which they are targeted and end up as a tool of oppression. This observation raises the following question: what governance approaches can promote local community participation in partnership processes? The answer to this question also requires an empirical research to inform on the strategies for supporting community participation in partnership processes.

Third, a review of the literature shows that many of the rules and regulations developers are expected to conform to are more detrimental than enabling. By implication adoption of the regulations that apply to statutory urban areas can pose the same constraints and the consequent problem of informal growth, which defeats the purpose of the partnership strategy. This observation raises the following question: What aspects of the regulatory frameworks require adaptations to make regulations enabling in the allocation of land? Equally, the answers to this question require an empirical research to examine what has to be adapted/appropriated.

Description of case study area

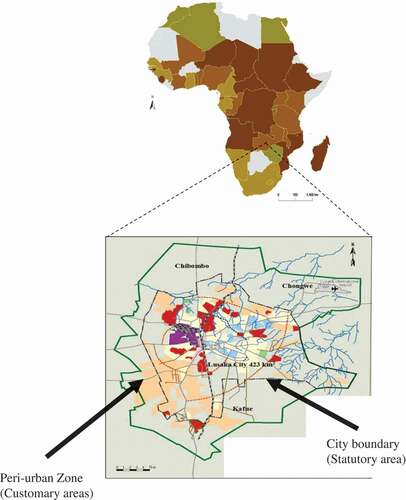

Lusaka is the capital city of Zambia with a population of 1,742,978. It covers a total area of 360 square kilometres, which translates into a density of 4,853 persons per square kilometre (Zambia Central Statistical Office [CSO] Citation2012). The City is surrounded by customary areas and has reached the carrying capacity as shown in . A durable solution is peri-urban land conversion to municipal tenure, but this is not a feasible alternative. This is made impossible, as already stated, by the prevailing customary land tenure system which is typically concerned with preservation of authority and protection of communal land ownership rights, which contrasts with the statutory form of land governance that adopts private land rights as a means of achieving sustainable human settlements and housing investments.

Figure 2. Locations of Zambia and Lusaka City, respectively, highlighting the boundary between statutory urban and peri-urban areas

The land access problem has led to a situation of land use changes from agricultural to residential. However, according to Lusaka City Council (Citation2008) State of Environment Outlook Report, these commercially driven developments do not cater for the low-income groups. Both formal and informal (squatting) means of land use changes make the city sprawl with the attendant problems of inadequate infrastructure – the extension of infrastructure such as roads, electricity, water supply and sewerage treatment facilities, which the City Council is unable to provide. An observable trend resulting from the failure to provide electricity energy is high usage of charcoal as substitute, which is accelerating deforestation. Also the failure to provide basic services like water and sanitation, means boreholes and septic tanks are the common self-improvised facilities; with the later having high polluting effect on underground water. Studies have shown that the City’s geographical location on limestone worsens the problem by reducing dilution of contaminants through natural filtration (Banda Citation2010). Closely related, the poor structures and crowded nature of some informal dwellings pose grave consequences to public health, especially in the rainy season when deadly diseases like cholera outbreaks (Nchito Citation2007).

These are direct negative effects; there are indirect negative impacts which affect residents. People are compelled to commute longer distance from such places, which involve spending time and money when fetching services. These commuting costs put a burden on households, especially the low-income. A reasonable amount of the food that sustains the population is sourced from the surrounding farmlands which are converting to residences, which is impacting on food security. This sprawl according to the Lusaka master plan is conspicuous in the north, east, and south direction of the Greater Lusaka shown in .

Figure 3. Urban sprawl situation caused by formal and informal land use changes

Research methods

The field study adopted qualitative research methods using interviews with research participants considered significant informants for narration of experiences and suggestions pertinent to the study. The participants were 25 experts drawn from state and non-state establishments charged with the responsibilities for management of state functions. The non-state actors were participants regarded to play ‘critical or observer’ roles in housing delivery. Details of the selected institutions and rationale for the selection are in .

Table 1. Respondent institutions

The interviews centred on eliciting views and ideas related to strategies for actualising partnerships from the research participants. This focused on the three questions that emerged from the theoretical framework. Group discussions and personal interviews, using open-ended questionnaires, were the main data collection methods. Open-ended questionnaires often described as conversations with a purpose (Creswell Citation2007), enabled the research to explore an assortment of issues outside the restraints of a ‘fixed question response’ process. The data in the form of notes, tape recordings and observation records were processed through transcription, sorting, coding and categorization for full analysis. Methods of deriving meaning from recorded interview data, such as noting patterns or themes, seeing plausibility, clustering and making comparisons and contrasts, were used (Silverman Citation2001).

Research findings

The empirical research involved different respondents with various actualisation viewpoints, therefore the research findings are presented in the order of the three questions raised in the theoretical framework. The first subsection presents the finding on methods and strategies for building and strengthening collaborative relations among the various institutions. The second subsection presents the finding on the methods and strategies for making partnership processes participatory. The third subsection presents the findings on the identified regulatory aspects that can impede partnership facilitated land and housing delivery processes and the counteractive measures.

Strategies for building and strengthening collaborative relations

The responses to this question were as follows. Drawing on partnership-related work experiences with state institutions, the civil society participants observed that decision-making and operations of local partnership were often dominated by government institutions or large business establishment, which have the capacity and resources to devote to the task. This tendency has the potential for biased resolutions which can cause mistrust from traditional authorities who may misconceive partnership as a government strategy for annexing customary lands. To make state and customary institutions collaborate, the participants emphasised negotiation and compromise approaches to partnership management. The need for these approaches is that since they are dialogue-based, parties with divergent views, particular state institutions and customary authorities who have dissimilar governing systems can reach decisions and agreements that support a common goal through negotiations. For example, a respondent from the Ministry of Lands said that though some land conversions took place, the alienated lands were not sufficient for large-scale city expansion. This response prompted the following question:

The law governing land tenure in Zambia gives powers to the state for compulsory land acquisition for programmes of public interest such as housing which is a critical issue in Lusaka City. Why are these powers not exercised?

‘The provisions are not enforced to avoid conflicts between the state and the customary authorities or communities, which may perceive the action as autocratic. Even if the law in principle recognises the republican president as holder of all land, in trust and on behalf of all citizens, the local chiefs wield power over traditional areas. This makes the compulsory acquisition provision under the existing tenure system contentious and politically risky to a ruling party. The best approach to the issues is negotiations’

Regarding the form and substance of collaborations, a common suggestion was that a partnership should be an activity and a process for providing land and financial opportunities for affordable housing delivery involving government institutions, traditional establishments, NGOs and commercial entities. Two forms of collaborations were suggested: commercial and non-commercial engagements. The corporate sector-based participants and one of the civil society participants proposed business-oriented engagements. The suggested key players and roles were chiefs to be responsible for land provision, the City Council or a government ministry to be responsible for roads, water and other vital services and private land developer(s) to be responsible for construction of houses. The motive underlying the suggestion is preclusion of the negative aspects of conversions. The other reason was that real estate business was a capital intensive venture which made serviced plots or houses supplied wholly by private developers expensive. The explanation was that by offering customary land on lease basis, a traditional authority does not lose the land, instead receives revenue from the private investor, or a community pays the private service provider for better-quality infrastructure and service delivery. Another suggested alternative was build-operating transfer (BOT) partnership framework, in which a customary authority enters into a long-term contract with a private entity to finance, build and operate low-income houses for an agreed number of years and at the end of the contract period transfer ownership to customary authorities.

The civil society participant, who favoured the commercial approach said peri-urban areas under customary tenure needed massive investments in housing and auxiliary infrastructure to improve the poor living conditions. To motivate customary authorities provide (more) land for commercial-oriented developments, the respondent suggested a partnership arrangement that paid royalties. In the respondent’s words:

I find the complaints of City council officials and private commercial developers concerning the refusal by chiefs to provide land unjustifiable. What are required are commercial land delivery deals, which can generate income for the benefit of both parties. For example, a proposal can be put forward by the City Council or a private commercial land developer that goes like this: we want to construct houses for resettling people from urban areas and in return for the land, this is what we are able to offer you what do you say? No chief or community member can make objections to such a progressive partnership deal. The cause of the objection is the failure to address certain basic needs of local communities, or compensate the communities for the lost land, or sharing the proceeds generated from the land given free of charge to local authorities.

The majority of the civil society participants emphasised non-profit engagements; comprising traditional authorities (responsible for land provision), the City Council or central government (responsible for municipal services provision) and NGOs (responsible for resource mobilisation, and where necessary, collateral security guaranteeing). The focus and interest of partnerships in a city like Lusaka, with so many low-income developers, should not be very much on commercial gain, but on assisting people to secure land and on provision of financial resources to build legally and affordably. This was well expressed by one of the participants:

A non-profit collaborative partnership with NGOs is one of the available options which the local authorities or the central government can exploit. Based on my work experiences with squatter programmes, most squatters are resourceful and ingenuous in adapting to their situations and in finding ways to improve their personal circumstances. All that is needed are responsive initiatives by NGOs and the government to stimulate them to invest money in their own houses. The site and service scheme policy response make government the major provider of infrastructure, which is too much of a burden for a low-income country like Zambia, but forging alliances with NGOs, can lessen the burden of providing services. Actually partnerships will only make government an enabler not provider. The major players and investors in such partnerships will be the informal dwellers and other deprived land seekers.

Participants from the Ministry of Local Government and Housing looked at the issue from a technical perspective. They noted that traditional authorities lacked the requisite surveying, planning and development control skills for complex developments, which can result in haphazard developments and poor structures. To avoid this, and to improve the ability of local communities and their traditional establishments to plan and efficiently deliver land, requires a great deal of collaborations with the City Council in form of joint planning engagements.

On the subject of rules of engagements, some participants, mainly from the corporate sector, suggested formal rules to regulate and enforce agreements. Most of the civil society participants, emphasised informal and trust-based agreements, without tightly prescribed contracts. The explanation for this proposal was that the unwritten contractual system of customary land law reduces monitoring and contracting costs. A number of government-based respondents suggested that the rules of engagements should be context-dependent, that is, formal or informal, determined by prevailing circumstances.

Making partnership processes participatory and inclusive

The responses to this question were as follows. In the first place, all the participants agreed with the view that the traditional way of governance generally treats subjects as tools of decision implementations, rather than decision-makers and main actors; attributed to its centralised nature. In order to make partnership processes inclusive and participatory, a common suggestion was devolution of management responsibilities to local communities to make and implement decisions in collaboration with NGOs. To cite one respondent’s suggestions for elaboration:

Customary regimes in Zambia and the rest of sub-Saharan Africa have one commonality; the customs and norms prohibit the flow of decisions from the bottom to the top, which makes land administration a prerogative of chiefs. In some chiefdoms, community participation in land administration is limited to headmen, who are permitted to handle land applications of outside land seekers on behalf of chiefs. Some headmen misuse this privilege by allocating land for personal monetary gains. These misdeeds cause problem such as dislocation of local communities, animosities between chiefs and subjects or between the locals and land buyers. Therefore, the design of partnership as a body for collaboration among vested interest groups should be in a way that creates harmony and equity in land allocation.

Another participant suggested that:

Prevention of the misuse of authority depends on the ability and extent NGOs can open up participation spaces for subjects to influence and shape the land allocation decisions. NGOs are the only entities that can facilitate participation, reason being that as self-governing and neutral entities, that is, not accountable to the state or customary authorities, are better placed to promote community participation, by lobbying for devolution of management responsibilities to local communities in collaboration with NGOs to make and implement decisions. Particularly in relation to the day-to-day business of initiating and preparing plans, approving plans, raising finances and project implementation and maintenance. In other words, civil society mediation provides local communities with the opportunity to interrelate with their traditional leaders to make decisions, exchange ideas, give suggestions and set local priorities and needs, with clear-cut divisions and roles and responsibilities in partnerships.

Networking, described as an activity of using formal or informal personal or institutional contacts, was suggested as one of the forms of intermediary for the following reasons.

‘why do you consider networking a good approach to inclusive decision-making?’

‘Networking approach to partnership governance hold out prospects of more inclusive decision-making in that through the formal or informal interactions, subjects can discuss and negotiate for fair policies, seek transparency and accountability from customary authorities and other key decision-makers.’

Regulatory aspects needing adaptations

On this question, a common response was that people developed informally due to lengthy land titling procedures which often involved costly cadastral surveys, compared to the procedurally simple traditional land titling system. In light of this, the suggestion was that to make partnerships work as a tool for delivering customary lands, the emphasis should be on provision of housing finance and less costly form of land titling to the low-income groups. This required recognition of customary land titling certificates as collateral especially in commercial transactions. A related suggestion was adoption of a communal land titling certification system. The explanation for this was that since lending institutions, demand collateral in form of land with title deed and valuation report, which does not include title certificate documents issued by customary authorities, this titling policy would cause mortgage access difficulties if applied to customary areas. Regarding the need for communal titling certification approach, the explanation was that partnership need to operate as mechanisms for mitigating mortgage access problems and one way of achieving this was through a policy shift from the individual-focused titling system to community-based titling system. The following are some sampled responses for elaboration:

High transaction costs make people to think if I cannot get it quicker, I will abandon what is formal, and the outcome is the unprecedented growth in informal settlements we are witnessing. (words of the Habitat for Humanity Participant).

The UN-Habitat participant also described informal housing as:

A manifestation of property registration and land titling failures by responsible government institutions. This failure is not a recent incidence, but developed 30 to 40 years ago, that is why settlements that had populations of 30,000 have now grown to over 300,000. Once a system fails on critical issues such as land and housing, then people find a way out.

Regarding the significance of communal land titling, the Civic Forum on Housing and Habitat respondent said:

The African communal way of living provides an opportunity for ending housing finance and cadastral service access difficulties in the sense that since land is communally owned, residents can jointly apply for housing finances which will make debts and liabilities to be shared not owned individually. Land tenure security provision using a single land title offers prospects for reducing cadastral survey and related costs because they can be met collectively.

Another respondent stated:

I don’t agree with the view of private land titling as the best form of tenure security. This form of land titling which is borrowed from the English land administration system obligates homebuilders to have surveyed premises. This requirement overlooks the fact that many households are poor let alone a developing country like ours [Zambia] does not have the capacity to provide sufficient cadastral services. Therefore, this policy causes more harm than good to the low-income housing. For partnership to ease land titling constraints communal land titling certification is a very pragmatic means of providing land tenure security for the poor.

A similar suggestion was made by the Entrepreneurial Financial Centre respondent who said:

Formal collateral standards in a peri-urban setting dominated by informal livelihood strategies would not be appropriate. The African communal way of living can facilitate provision of collateral security to those without assets to present as surety. Those without could be assisted with access to credits by scheming mortgage facilities on social collateral basis guaranteed through solidarity groups in which members become responsible for each other’s debt repayment. This is how we reach out to such clients. We tap into the communal networks composed relatives, friend or proxies with the necessary documents, to act as guarantors, to accommodate those without the necessary documents or means.

A Lusaka city planner also said that:

A communal approach to land titling holds prospects for precluding gentrification problems experienced in site and service and squatter upgrading programmes. On recognition of the ability of informal settlers to finance and construct their own dwellings mostly independent of institutional inputs, the council responds by initiating site and service schemes. This strategy involves provision of plots to reduce the need for informal housing, but faces gentrification challenges. Most beneficiaries sell the plots to the rich and relocate to former informal settlement or start another one. The same gentrification problem is experienced in upgrading programmes; the improvements tempt most dwellers to sell the plots and relocate to other informal settlements. A similar scenario is possible with peri-urban improvement programmes, but the presence of chiefs as the custodian of the land and as communal title holder on behalf of the residents, the gentrification problem does not stand a chance of occurring.

Concerning the need to adapt traditional building technologies and methods, the respondents perceived the formal building standards based on the preconceived notion of an ordered city would be inappropriate in respects of the context in which most peri-urban residents live. In light of this, the respondents said adoption of different building standards that allows greater use of cheaper materials was imperative. The emphasis was on the recognition of alternative but robust and inexpensive earth-based materials used in villages, such as clay and dambo soil for brick moulding which are relatively durable, besides the technology involved in the production compared to cement does not involve mortaring and generally 50 per cent cheaper. In the case of weak materials, what is simply required are improvements to building technology to improve durability, structural limitations, and low resistance to abrasion and impacts. The other reason is accommodation of cultural characteristics in the settlement structure, which is greatly side-lined by formal standards. On this, the observation was wholesale adoption of formal standards can disrupt intergenerational transmission of the building and architecture that reflects local cultural in peri-urban areas.

Discussion of the findings

The aim of the research was to provide answers to the three significant questions to partnership actualisation which were not adequately addressed by the literature. Before going into detailed analysis of the findings, it is important to state that the responses show great confidence and optimism among the research participants on partnership as the ideal vehicle for improving access to customary held peri-urban lands and provision of basic services. As regards the questions the research was intended to address, the answers are as follows.

Question one: What governance approaches can promote and consolidate engagements and collaborations?

Regarding the first question, to make the institutions collaborate, compromises and negotiations have emerged as the key strategies for building collaborative relations, the other being informal and trust-based agreements. The explanation for the significance of compromises and negotiations approaches is that they are best for resolving difference or reaching satisfactory agreements involving parties with divergent governance ideologies such as state institutions and customary authorities. This strategy is also highlighted in the literature discourse on the consensus principle of good governance which emphasises cooperation, dialogues and compromises as a means of reaching mutually accepted resolutions without recourse to majority voting (see Stoker Citation1995; Abbott Citation1996; Peterman Citation2000; Pierre Citation2000). With respect to the informal and trust-based contractual strategy, the essence is circumvention of contract enforcement and monitoring costs. This strategy is highlighted in the literature discourse on the good governance principle of responsiveness, which requires institutions to tailor service delivery frameworks to prevailing contexts and situations (See UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013).

Question two: What governance approaches can promote local community participation in partnership processes?

With regard to this question, to promote community participation in partnerships processes, the emerging strategy is civil society intermediary. The basis for this approach is that NGOs’ close working relationships with local communities, their ability to forge multi-layered relations and independence from government or traditional establishments provides an opportunity for communities to engage and negotiate for fair policies, and to ensure transparency and accountability from customary authorities. This proposition is in line with current international thinking, notably, Fung and Wright (Citation2001) who observed a global movement towards management systems that have decisions taken at local levels, often in partnership with local NGOs, aimed at ensuring accountability, transparency and inclusiveness. A noteworthy suggestion for enhancing the intermediary role is networking which resonates with the explanations of Pierre (Citation2000) and Peterman (Citation2000) that collective actions make governance processes inclusive, transparent and accountable. In short, these suggestions connect with the good governance principles of transparency and accountability.

Question three: What aspects of the regulatory frameworks require adaptations to make regulations enabling in the allocation of land?

Concerning the this question, adapting land titling to communal ownership model has emerged as an enabling strategy for partnership-based land and housing delivery processes. The reason behind the communal land titling suggestion is its simplicity, which is also highlighted in the literature discourse on the good governance principle of responsiveness (see UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013). Closely linked, one of the stated causes of informal housing is the exclusionary terms and conditions of mortgage provision. In this connection, a suggested strategy for informal growth prevention in customary authority administered peri-urban areas is the designing of partnership processes in ways that facilitate access to housing finance for the less economically able developers. This strategy is also highlighted in the literature discourse on the equity and inclusiveness principle of good governance (World Bank Citation1992; UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013).

Building standards

The suggestion to adapt building standards to local conditions as a strategy for enabling actualisation is highlighted in the literature discourse on the good governance principles of effectiveness and efficiency (see UN-Habitat et al. Citation2013). Another significance of adapting local building technologies and methods to local conditions stated by the respondents is motivation of voluntary compliance which is also highlighted in the literature discourse on the good governance principle of rule of law (See Payne and Majale Citation2004). Formal recognition and improvements through research make the issue of affordable housing delivery feasible as it will provide planning authorities several approval options regarding housing quality, strength and level of material usage in various neighbourhoods of peri-urban areas. Local building materials, housing methods and technologies and mixed use development will enable urban planners to promote and sustain diversity in a contemporary city.

In sum to make the institutional actors collaborate, the research has shown the importance of consensus-oriented decision-making, cooperation, dialogue, negotiation and compromise approaches to the management of partnership. Closely linked, the research has shown the significance of embedding in partnerships the informal and unwritten system of agreements and contractual practices. Participation as a vital element of partnerships, the research has shown that making partnership-based governance processes participatory requires devolution of management responsibilities to communities to make and implement decisions. To achieve this, NGOs should play a central role, which should take several forms ranging from networking, coordination, dialoguing, lobbying to negotiations. Regarding the question of regulatory adaptions, the research has shown that regulatory frameworks should reflect the traditional methods of land and housing delivery to ease land access constraints and building costs. This should include recognition of documents issued by customary authorities as collateral alongside adoption of communal land titling system to avoid the costly and lengthy land titling procedures of statutory and private land holding system.

Conclusion

This paper has explored land delivery processes which meet the twin goals of providing access to peri-urban lands under customary law for low-income housing and preservation of customary land ownership rights. Partnership has been identified as a strong option for two main reasons. First, it is ideal on account of the tension between private and communal ownership. In short, partnership as the vehicle for delivery of land under customary law does not affect ownership. Second, formally accepted housing delivery depends on financial ability. Most low-income developers opt for the informal sector because it is affordable. The bringing of private, civil society or governmental institution to work with customary authorities for the purposes of financing, or building affordable housing and provision of support infrastructure is a very significant feature.

The paper has shown that making the partnership option work in the delivery of customary lands, the processes should be guided by the principles of good governance. These are rule of law, effectiveness and efficiency, equity and inclusiveness, responsiveness, consensus, accountability, transparency and participation. The significance of rule of law relates to the formulation and implementation of rules and regulations that are appropriate to local conditions. The significance of effectiveness and efficiency relates to the use of local building materials and technologies that reflect the needs, priorities and affordability of developers. A secondary reason is accommodation of cultural characteristics in the settlement patterns. The significance of responsiveness relates to making land delivery cheap and procedurally simple. The necessity of equity and inclusiveness relates to facilitation of access to housing finance and basic services for the low-income groups. The significance of consensus approach is to develop dialogues, attain mutual agreements and resolutions by the actors who operate in different institutional settings. The need for accountability relates to monitoring and regulating the conduct of individuals or bodies trusted with the responsibility of managing land and partnership affairs. Transparency is required to ensure decision-making and their implementation is done according to the agreed rules and regulations. On top of that the information should be freely accessed by stakeholders and in an easily understandable form. The essence of participation is to guarantee greater openness for accountability, transparency, responsiveness, equity and inclusiveness.

Acknowledgements

This paper is derived from the author’s doctoral dissertation and would like to acknowledge Dr Dumiso Moyo, David Kirk and Peter Cockhead, for their supervision and encouragement for this research. The author is also grateful to the journal’s managing editor and the two anonymous reviewers for helpful advice and comments for revision.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Howard S. Chitengi

Howard S. Chitengi is an urban planner who has worked for the Department of Physical Planning in the Ministry of Local Government of the Zambian Government. He holds a Bachelor's degree with a major in Geography from the University of Zambia, a Master's degree In Spatial Planning from the Royal Institute of Technology-KTH, in Sweden and a PhD in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Dundee, in Scotland, United Kingdom. His fields of interest include understanding of the 'push' and 'pull' factors that reinforce informal settlement resilience and how the resilience characteristics can be assimilated in urban planning and development policies. His research works among others seek to promote local approaches to urban planning and development by focusing on and drawing lessons from the dynamics of Sub-Saharan Africa urbanization, informality and spatial planning.

References

- Abbott J. 1996. Sharing the city: community participation in urban management. London: Earthscan.

- Adams M. 2003. Land tenure policy and practice in Zambia: issues relating to the development of the agricultural sector. Oxford: Makoro Consulting.

- Baggs D. 1992. Future architecture trends with fewer building services. Journal of Geotecture International Association. 9(2):37–40.

- Banda L. 2010. Effect of siting boreholes and septic tanks on groundwater quality in saint bonaventure township of Lusaka district [ master’s thesis]. University of Zambia.

- Berry J, McGreal S. 1995. European cities, planning system and property markets. London: E & FN Spon.

- Brown T. 2003. Contestations, confusion and corruption: market-based land reform in Zambia. In: Evers SE, Spierenburg M, Wels H, editors. Competing jurisdiction: settling land claims in Africa (pp. 79–105) Danver: Koninklijike Brill NV. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.ed/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.184.397&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Bull B, McNeill D. 2008. Development issues in global governance: public-private partnerships and market multilateralism. New York: Routledge.

- Chang T. 2009. Improving slum conditions with public private partnerships. REAL CORP 2009 Proceedings. http://www.corp.at/archive/CORP2009_155.pdf.

- Chitonge H, Mfune O. 2015. The urban land question in Africa: the case of urban land conflicts in the city of Lusaka, 100 years after its founding. Habitat Int. 48:209–218.

- Creswell J. 2007. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. California: SAGE Publications.

- CSO. 2012. Census of population and housing report. Lusaka:Central Statistics.

- De Soto H. 1989. The other path: the invisible revolution in the third world. London: Harper Collins.

- Elander I. 2002. Partnership and urban governance. International Journal of Social Sciences. 54(172):191–20.

- Farlam P. 2005. Assessing public-private partnership in Africa Nepad Policy Focus Report No.2. South Africa: South African Institute of International Affairs. https://www.oecd.org/investment/investmentfordevelopment/34867724.pdf.

- Fox S. 2014. The political economy of Slums: Theory and evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development. 54:191–203.

- Fung A, Wright E. 2001. Thinking about empowered participatory governance. In: Fung A, Wright E, editors. Deepening democracy: institutional, innovations in empowered participatory governance. London: Verso; p. 1–20.

- Gardner D. 2007. Access to housing finance in Africa: exploring the issues. Pretoria: FinMark Trust.

- Gebre HA. 2014. The impact of urban redevelopment-induced relocation on relocatees’ livelihood asset and activity in Addis Ababa: the case of people relocated Arat Kilo area. Asian J Humanities Soc Stud. 2(01):43–50.

- Hadjri K, Osmani M, Baiche B, Chifunda C. 2007. Attitudes towards earth building for Zambian housing provision. Proc ICE Eng Sustainability. 160(3):141–149.

- Hansen K. 1997. Keeping house in Lusaka. New York: Colombia University Press.

- Home R. 2015. Colonial urban planning in anglophone Africa. In: Silva CN, editor. Urban planning in sub-Saharan Africa: colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. New York: Routledge; p. 53–66.

- Home R, Lim H. 2007. Squatters or Settlers?: Rethinking Ownership, Occupation and Use in Land Law, Report of Onati Workshop Held in June 2005, papers in Land Management No. 2 Available at http://ww2.anglia.ac.uk/ruskin/en/home/faculties/alss/deps/law/staff0/home.Maincontent.0008.file.tmp/No2-Onati%20workshop.pdf

- Japan International Cooperation Agency Study Team. 2009. The study on comprehensive urban development plan for the city of Lusaka in The Republic of Zambia Draft Final Report – Summary. Tokyo: Kri International Corp.

- Kangwa M. 2007. Availability of finance for housing development: The case of low cost housing in Lusaka [ MBA thesis]. The Copperbelt University.

- Lusaka City Council. 2008. Lusaka city state of environment outlook report. Lusaka:Lusaka City Council.

- Ministry of Local Government and Housing. 2008. Discussion document: revision of legislation related to spatial planning in Zambia. Lusaka:Ministry of Local Government and Housing.

- Mudenda M. 2006. The challenges of customary land tenure in Zambia. Paper presented at shaping the change congress; Oct 8–13; Munich, Germany. https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2006/papers/ts35/ts35_05_mudenda_0858.pdf.

- Mushinge A. 2017. Role of land governance in improving tenure security in Zambia: towards a strategic framework for preventing land conflicts [ PhD thesis]. Technische Universität München.

- Nchito W. 2007. Flood risks in unplanned settlements of Lusaka. Environ Urbanisation. 19(2):539–551.

- Payne G, Majale M. 2004. The urban housing manual: making regulatory frameworks work for the poor. London: EarthScan.

- Peterman W. 2000. Neighbourhood planning and community based development: potentials and limits of grassroots action. London: Sage Publication.

- Pierre J, editor. 2000. Debating governance, authority steering and democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pike A, Rodriguez-Pose A, Tomaney J. 2006. Local and regional development. New York: Routledge.

- Rakodi C, Leduka C. 2004. Informal land delivery processes and access to land for the poor in six African cities: towards a conceptual framework. University of Birmingham. Working paper No. 1.

- Rhodes R. 1996. The new governance: governing without government. Polit Stud. 44(4):652–667.

- Schuster J. 2005. Substituting information for regulations: in search of an alternative approach to shaping urban design. In: Ben-Joseph E, Szold T, editors. Regulating place: standards and the shaping of America. London: Routledge; p. 62–68.

- Silverman D. 2001. interpreting qualitative data: methods for analyzing talk, test and interaction. london: sage publications.

- Stoker G. 1995. Governance as theory: five prepositions. Int Soc Sci J. 50(155):17–28.

- Stoker G. 1997. Public-private partnerships and urban governance. In: Pierre J, editor. Partnerships in urban governance: European and American experience. London: Macmillan.

- Tannerfeldt G, Ljung P. 2006. More urban less poor: an introduction to urban development and management. London: EarthScan.

- UN General Assembly. 2005 Enhanced cooperation between the United Nations and all relevant partners, in particular the private sector. United Nations General Assembly. Report of the Secretary-General, A/58/227.

- UN-Habitat. 2012. Zambia urban housing sector profile. Nairobi:United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- UN-Habitat, ITC, UN University and GLTN. 2013. Tools to support transparency in land administration: training package toolkit. Nairobi:United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- Viratkapan V, Perera R. 2006. Slum relocation projects in Bangkok: what has contributed to their success or failure? Habitat Int. 30(1):157–174.

- World Bank. 1992. Governance and development. Washington (DC):The World Bank.

- Xie Q, Stough R. 2002. Public-private partnerships in urban economic development and prospects of their application in China. Paper presented at the International Conference on Transitions in Public Administration and Governance; Jun 15–19; Beijing. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/aspa/unpan004644.pdf.