ABSTRACT

The nature of tenure ‘contracts’ that exist within the low-income settlements involves more than title deeds. Accordingly, ‘tenure security’ manifests itself beyond legal or de jure construction as it also involves de facto forms of tenure and dweller’s perception of security. The perceived tenure security is in turn a function of people’s lived experiences which shape the trust they may grant to the future effectiveness of land tenure arrangements. Contextual and historical factors, ranging from political patronage to market pressure to policy provisions, govern the perception of tenure security which usually gets overlooked in policy formulations. With a focus on Mumbai and Jaipur in India, this paper aims to generate and examine the viability of a list of indicators that influence perceptions of land and housing tenure security. The intention is to engender a method towards housing solutions beyond the unidirectional aim of titling and in favour of incremental approaches.

1 Introduction

Obtaining access to secure urban land is a complex challenge in the context of low-income settlements, often termed slums, or favelas in Brazil, gecekondu in Turkey, kampungs in Indonesia, or bastis in India. A key feature used across contexts to identify such settlements is based on the inability of households to produce formal proof of land or house ownership. Within statutory frameworks, only particular land contracts are deemed to be legal, that is, defensible in a court of law. However, multiple non-recognised forms of land tenure remain de facto. Peoples’ relationship with a house and its land cannot be dissociated from the socio-cultural and political reality of a place. Also, in the shift from customary land tenure as the dominant mode of tenure to freehold private ownership, many people’s historical tenure forms are not recognised. The non-recognition of a range of land tenure and property rights is translated into land and housing policies and perpetuates a dualistic way of thinking of legal-formal versus illegal-informal. This often results in the ousting of those who lack the legal means to prove their ‘eligibility’.

Having a secure form of tenure is a necessary precondition for addressing urban poverty. However, titling is not the only path to attain that. A granular understanding of the existing complexity of a communities’ relationship with their land and housing is needed. Tenure security is a combination of the perception of security along with de jure and de facto security. Unique to the context, there are manifold dimensions and layers that influence peoples’ perceptions. Perceived tenure security must then be analysed as an organic and fluid concept rather than with a linear interpretation. Analysis of the multidimensionality of this perception can push for diverse approaches towards security. Understanding and incrementally upgrading the urban poor’s perception of the security of their land and housing is, thus, a key component in enhancing their agency towards their habitat, increasing participation in land ownership processes, and expanding the landscape of social contracts.

This research sits within the issue of housing inequality, which in turn lies within the scholarship of social justice. Inspired by a range of writers (Young Citation1990; Harvey Citation1993; Fraser 1998; Fainstein Citation2014) who have interpreted socio-spatial justice, the foundation of this research is to explore land as a platform where there is a continual production of new forms of social relations. These relations comprise the ‘social dimension’ of space put forth by (Lefebvre Citation1968) and have inherent social contracts that necessitate deeper scrutiny. The growing perception of social justice as a framework, however, often focuses on either the ‘redistribution’ of resources or the ‘recognition’ of those marginalised (Fraser 1998). This translates into dualistic outlooks, and from the perspective of land and housing, it tends to favour freehold ownership above any other form of tenure. Rather than polarising these two notions, this investigation intends to cultivate an integrated and more nuanced understanding of land tenure and its associated sense, or perception, of security.

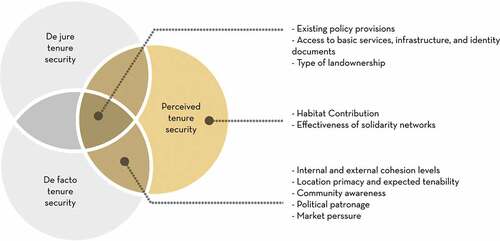

Within the three dimensions of tenure security (see ) – de jure, de facto, and perceived tenure security – this paper primarily aims to deconstruct the dimension of perception and explore the inter-relationality amongst the three. De jure tenure security conforms to the law and relies on the presence of titles and documentation. De facto tenure security tends to exist in practice over a certain duration, whether with lawful authority or not. Perceived tenure security is primarily a subjective assessment of immediate or future risks and need not always be in the form of de jure or de facto. The author seeks to develop a method to gauge the perception of land and housing tenure security of the urban poor, which can guide their decision-making. For this, he determines and examines a range of indicators that influence the perceived tenure security; indicators such as habitat contribution, effective presence of solidarity groups, location primacy, provisions of urban policies, political patronage, access to basic services, etc. Guiding this intention are two central research questions:

What indicators can help one understand what influences perceived tenure security and how can one measure their varying intensities through a social justice lens?

How can these indicators nudge urban policies towards incremental approaches to securing tenure in contrast to the one-size-fits-all approach of accepting freehold private ownership as the most suitable form of tenure?

The author first reviews relevant literature around land tenure, property rights, tenure security, and the formalisation programmes across the world. Following this, the paper maps the evolution of narratives around land tenure and informality at different scales and institutional capacities while narrowing towards the Indian context, with a mention of key urban policies that have impacted low-income settlementsFootnote1. Both international and India-focused learning become the base for a theoretical framework which guides the analysis. The method derived and employed for this research is a re-examination of the author’s field experiences in the Indian cities of Mumbai and Jaipur. The author has visited each of the selected settlements around 6–7 times, conducting first-hand in-depth qualitative interviews, which became the primary data-source for analysis. This assessment brings out the scholarship by means of a qualitative approach and mapping the same using spider-charts.

It must be noted that the derivation of this method to gauge perceived tenure security is based on subjective grounds which the author translates into specific results, and consequently develops generic recommendations. There are three key limitations of this work:

one, due to the restricted scope owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, the author was unable to test this theoretical framework with a directly relevant questionnaire for the selected settlements,

two, not all the listed indicators of perceived tenure security are measurable using the conventional scale of low to high, and

three, the author is conscious that perceptions may not always reflect the threats to tenure security that are not perceptible to people, like speculative land market investments, political changes, unknown legal provisions, etc. Thus, informed decision-making would require a holistic understanding and gauging of the de jure, de facto, and perceptions of tenure security.

This paper explores user-sensitive ways of measuring tenure security in ways which are non-judgemental and do not prioritise one variable over another. The propositions of this work intend to engage with the complexity of land and housing tenure, and the generated process would need to further evolve as a function of the context and of deeper investigations. It is hoped that this non-linear process is continued by relating more variables and it is intended to develop the propositions in a later paper.

2 Freehold, continuum, and beyond: a review of the literature

2.1 Origins

The debate of legality versus illegality has long existed in the domain of land and housing, particularly when the focus is on urban and rural poor. It was in the 1970s that the impetus towards the idea of tenure regularisation for informal housing started taking shape, predominantly stemming from the work of John Turner. He developed the argument that squatter settlements must be ‘accepted’ by the State, and that improved security of tenure can prompt people towards taking charge of their habitats, thus, giving them ‘freedom to build’ their own houses (Turner Citation1968, Citation1972). This is a central prerequisite to assisting self-built housing, an approach that was seen as a solution by using the construction skills that residents possess rather than relying completely on the government. This discourse led many international agencies like the World Bank to support schemes such as site-and-services and slum upgradation programmes, which relied on giving dwellers a legal form of secure tenure in the form of property titles. However, there were counter views to this approach and Burgess (Citation1982) believed that this tactic would lead to the propagation of commercial curiosity, or opposing commercial lobbies, as the settlements would then be formally recognised. Others (Angel Citation1983; Varley Citation1987) also contested if it was necessary to go with the titling approach as there were many cases of high perceived security, of a de facto nature, despite non-possession of titles.

2.2 Shifting paradigm

In the early 1990s, the focus gradually started shifting towards a neoliberal ideology that portrayed the State as inherently inefficient and bureaucracy as corrupt. The antidote was ‘enabling markets to work’ (World Bank Citation1993). The growing focus on capital creation – and cities being its primary accumulator – became the backdrop against which major policies were designed to promote commercial drivers of housing and land. Hernando de Soto, a prominent influencer during this era, predicated that a major impediment for capitalism in the then called Third World was the lack of enforceable formal property rights for the poor (De Soto Citation2000). Through formalisation, he believed that huge ‘dead capital’ could be unlocked. But this proposition did not account for what happened on the ground, such as expropriations as result of the ease with which poperty could be collateralised, or the disintegration of communities because of rapid opportunistic speculation.

The advocacy for the causal relation of legal property rights leading to tenure security – along with projected benefits such as access to credit – was reflected in official documents of the World Bank and UN-Habitat. This was further propagated by their influence on the governance of developing countries (Patel Citation2016). Even within the Sustainable Development Goals, there is an emphasis towards ending poverty in all forms by ensuring that ‘all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, [and] natural resources’ (UKAid Citation2015, p. 6). Yet many have claimed (Burgess Citation1982; Payne Citation2001; Gilbert Citation2002; Varley Citation2002; Mahadevia Citation2010; Van Gelder Citation2010) that reliance on de Soto’s approach can lead to exclusion by inviting market forces that can negatively affect community cohesion. The next section builds upon these arguments.

2.3 Counter arguments on the rise

mRolnik R (Citation2020) firmly believes that ‘individual, freehold, registered private property is the very base [emphasis added] of capitalist economy and capitalist biopolitics’ and the nature of individual property is the origin (p. 143). Drawing on a similar lens on tenure insecurity, Rolnik (Citation2019) argues how the concept of tenure itself, be it temporary or permanent is about people’s lived experiences and perceptions, and is ‘strongly rooted in the political, economic, juridical and cultural context of each region and nation’ (p. 112). Boonyabancha (Citation2019), while narrating her experiences about collective land tenure for housing with Community Organization Development Institute in Thailand, strongly argues that the obsession with individual tenure or freehold makes communities fight for land titles, which ends up becoming ‘another type of eviction’ (p. 172). She asserts that having a land arrangement that is collectively owned and governed, which translates into understanding and building on a different form of tenure security experienced by people, is an effective approach.

The basis of the counter-arguments described above is an underlying belief that land and housing cannot be purely perceived as a commodity or title or a document. It is here that the framework of social justice becomes critical. Expanding the notion of land tenure security, the author relies on the conception of social justice by Fraser (1998) who brings in the lens of ‘recognition’ along with ‘redistribution’. Her key argument elaborates on the growing dichotomy of approaching justice, where the proponents of redistribution ‘reject the politics of recognition outright, casting claims [as] … false consciousness’, while the ones supporting recognition as a dominant mode of thinking ‘see distributive politics as part and parcel of an outmoded materialism’ (Fraser 1998, p. 1). She pushes for integrated thinking – or ‘perspectival dualism’ – where any practice must be simultaneously thought of as economic and cultural (Fraser 1998, p. 5). Translating this lens towards the complexity of land, different authors explore the multidimensionality of tenure and security.

In defining appropriate policies, Payne (Citation2001) emphasises the need to understand the range of tenure systems, like the customary, private, public, religious, and non-formal categories. Owing to this complex overlap of ‘tenure systems and sub-markets within most cities [that] creates a complex series of relationships’ it becomes important to explore land tenure categories that lie within the extremities of de jure and de facto (Payne Citation2001, p. 418). As seen in , Payne reinforces the notion of a non-static nature of tenure, encompassing both pavement dweller and free-holder but acknowledging the variations in the degrees of tenure security.

The above has nurtured the idea of the land tenure security continuum, which has now been adapted by different forums and institutions. Facilitated by UN-Habitat, the Global Land Tool Network has developed a pro-poor tool for land management known as the Social Tenure Domain Model (Lemmen Citation2013) which includes the UN-Habitat endorsed continuum of land rights and tenure systems (see ). The intention of this model is to give legitimacy to different forms of tenure, ranging from customary to informal tenure, thus linking people, social tenure relationships, and spatial units. It propagates the idea of tenure formalisation of anything that falls on the continuum. In the workshop hosted by Habitat for Humanity International on strengthening land tenure security for urban poverty reduction in Asia-Pacific (Habitat for Humanity International Citation2017), a key outcome was the propagation of a non-binary notion of land tenure and levels of security in different countries. The workshop pushed for thinking towards the continuum of land rights model while pushing for the idea of the ‘incrementality’ process.

Figure 3. Continuum/ Range of Tenure Types. Source: UN-Habitat (Citation2008)

The author argues, however, that there are two major assumptions in this mode of thinking: one, ‘pavement dweller’ is considered as one homogeneous group which results in stereotyping and misrecognition of the category; two, the idea of a continuum, in itself, simplifies the complicated issue of land and housing reform, thereby, unwillingly sustaining the dualistic approach of moving from ‘bad’ to ‘best’, or from insecure to secure. It is important to note that these categories are not an endpoint or a comprehensive list, but a beginning – and they must be consciously adapted to the local contexts.

2.4 Moving beyond the continuum

Multiple authors (Payne et al. Citation2009; Mahadevia Citation2010; Van Gelder Citation2010) have analysed the complexity of land tenure and expressed the need to look at it beyond the binaries of legal and illegal. UN-Habitat defines tenure security as ‘the right of all individuals and groups to effective protection by the state against forced eviction’ (UNESCAP and UN-Habitat Citation2008, p. 6). Van Gelder (Citation2010) deconstructs tenure security in three forms; dweller’s perception, legal construction or de jure, and the de facto form. Debunking land titling and homeownership as the ultimate solution to address urban poverty, Payne et al. (Citation2009) show through the examples of Senegal and South Africa how possession of a title deed is not the only factor in engendering tenure security. In both cases, the mere ‘process’ of getting a title, or having an option to do so, bought immense security amidst the urban poor.

The earlier works of Payne (Citation2001) stress the need to understand and build on the systems of tenure that already exist. While it is this seed that is eventually translated into the typological framework he creates (refer to ) to ‘identify the range and distribution of statutory, customary and informal tenure categories in a city, the de facto levels of security [emphasis added] provided by each and the various property rights associated with them’ (Payne 2003, p. 167). In his latest piece, his central focus is on the idea of incremental development of land tenure by respecting the diversity of needs of people (Payne Citation2020). Justifying his claims, he lists a set of good interventions, mainly under tolerance-based, proactive, semi-formal, and formal interventions in geographies ranging from Bolivia, Egypt, Philippines, South Africa, Kenya, Puerto Rico, Thailand, and India.

2.5 Land tenure security in the Indian context

In the Indian context, the complexity of land tenure security appears at different scales and forms depending on the geographical context. Limited research has been undertaken to understand secure tenure beyond the distribution of titles. Banerjee (Citation2002) writes about the two-fold understanding regarding tenure regularisation and its percolation into policies. One is the ‘functional approach, in which secure tenure is seen as a means of achieving definite objective’ while the other being the ‘rights approach, emphasizing that every citizen has the right to a secure place to live’ (p. 37). She recognises that the two possible forms of results for tenure security are either through proper ‘legally’ defined documents or through a range of factors that determines implied tenure security like ‘public investment, notifications, court stay orders, political patronage or group solidarity’ (Banerjee Citation2002, p. 37). With a central focus on tenure systems that exist in Mumbai – mainly tenancy, ownership, and leasehold – (Pimple and John Citation2002) talk about the means through which organisations have achieved success in their demands for better tenure security, however, not centred around getting titles. From the perspective of Delhi, Risbud (Citation2002) highlights manifold examples of people feeling insecure despite having conventional forms of secure tenure.

Going into more depth by profiling different informal settlements of Delhi and Ahmedabad, Kundu (Citation2002) talks about the existing range of tenure systems and the diverse arrangements these habitats encompass. He identifies different factors that can have a major influence on the perception of tenure security amidst people – like the location of a settlement, nature of the land ownership (public or private), possession of identity cards, availability of basic services, and the active presence of NGOs and CBOs to name a few. Mahadevia (Citation2010) looks at tenure status in the form of a continuum that ranges from illegal or insecure to legal or secure. She argues that the policymakers in India need to recognise the gradual upgradation in the de facto forms of security for urban poor to improve their access to measures of social protection.

As a response to the 2009 Central Government policy Rajiv Awas Yojana,Footnote2 the Centre for Urban Equity (Citation2010) proposed a practical approach by creating a ‘Land Tenure Manual’ that discarded the distribution of property rights as a ‘quick’ way to achieve the policy’s objectives. With an attempt to understand the State’s encounter with people through legal tenure security, Patel (Citation2016) explores the other practical side of legal tenure security by highlighting the way in which the State exerts control over people’s lives under the pretext of ‘economic development’ and ‘managing informality’. Nakamura (Citation2016), in the same tone, writes about the ‘invisible rules’ in slums by focussing on the city of Pune, India. Nakamura interprets security in a more nuanced manner, where politics – and not purely the legal status of a settlement – becomes a major factor in people’s perception of tenure security.

Bhan et al. (Citation2014) argue for the need for ‘development time’ that can be a significant way to look at secure tenure without the possession of an actual title, resonating with what Weinstein (Citation2014) calls the ‘Right to Stay Put’. Amidst the range of innovative approaches they discuss, the ‘non-corporate private market’ – comprising of households, communities, and local contractors – is significant. The focus then must be on ‘legitimising’ the existing nature of land relationships people have rather than discarding their ‘eligibility’ from the legality lens (Bhan et al. Citation2014). Developing this thought further, Bhan et al. (Citation2017) define a new way of thinking about legitimacy as an idea, which they call ‘the intent to reside’ (p. 259). This approach breaks from the dualistic thinking of legal versus illegal and does not believe in making residents ‘prove’ their eligibility. On the contrary, the authors propose a need to measure residence by recognising multiple forms of identification through which they can include residents from an early stage by understanding their ‘intention’.

3 Indicators for measuring Perceived Tenure Security (PTS)

Market-centric development agendas have continually pushed for a homogeneous way of tenure formalisation through freehold private ownership. As mentioned before, the understanding of tenure security is a combination of de jure, de facto, and perceived tenure security (PTS). This evidence-based research primarily focuses on people’s perceptions of urban land and housing tenure security, exploring the multi-dimensionality of PTS in depth. The phenomenon of PTS can be conceived as a function of a wide range of factors, which can lead towards recognition of varied de facto tenure categories. The intensity to which a household specifically, or a settlement generally, feels tenure-wise secure is governed by political, legal, economic, socio-cultural, and attitudinal factors.

To understand and gauge this complexity of determining the degree of PTS, the author proposes a framework of indicators. This framework considers both the ‘redistribution’ and ‘recognition’ lens of social justice (Fraser 1998). Just like understanding social justice from a dualistic perspective can lead to a dominance of either material-distribution or difference-recognition, a similar outlook to determine PTS can derive a skewed understanding. For instance, the focus on redistribution can push for the dispersal of identity documents or land titles as a dominant narrative (de jure), while the recognition approach can lead to political campaigning without enough material change. The defined indicators for understanding secure tenure must address the concerns regarding the economic structure of ‘class differentials’ and the culturally defined ‘status hierarchies’ (Fraser 1998, p. 5). So, broadly the author identifies ten indicators that influence the PTS (see ). However, many of these indicators (see ) cannot be boxed under one of the three categories of de jure, de facto, and PTS but are a combination of any of the two or all the three. For the purposes of this work, the author focuses on PTS indicators and their overlaps.

Figure 4. Theoretical Framework to gauge Perceived Tenure Security in a settlement. Source: Elaborated by author from understanding of Fraser (1998).

Figure 5. Distributing indicators within the Venn diagram, with a focus on perceived tenure security. Source: Author.

3.1 Defining the indicators for perceived tenure security

3.1.1 Internal and external cohesion levels

This indicator is a measure of the cohesion between residents of a settlement and the surrounding neighbourhood—which cuts across different factions that exist in settlements based on class, religion, caste, and gender. Ghertner (Citation2012), with respect to the context of Delhi, shows how the stigmatization of slums as ‘filthy’ or ‘nuisance’ leads the surrounding residents’ welfare associations to file litigations against them, eventually leading to evictions. In Mumbai, it is common to find a non-notified settlement adjacent to commercial offices and high-end residential gated communities. This, eventually, exerts direct real estate pressure, often under the name of ‘beautification’. In another context, in the Bombay Hotel settlement in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, Desai et al. (Citation2016) highlight how the 2002 communal riots created further religious segregation between Hindu and Muslim settlements in an already polarized city, thus, affecting people’s PTS levels.

3.1.2 Habitat Contribution

This indicator emphasizes the different kinds of contribution people make towards their habitats—house or surrounding infrastructure—in the form of financial or in-kind investment. Kaccha, semi-pucca, or pucca are some of the common terminologies for defining the structure type. The habitat contribution can be a determinant of people’s confidence to invest in their house and the local environment. Contrary to this, people also contribute or invest in their house despite non-possession of titles, inspired by their neighbours’ investment. Using the case of Buenos Aires, Argentina, Van Gelder (Citation2009) shows how varying levels of perceived tenure security influence housing improvements and the settlement’s development.

3.1.3 Effectiveness of solidarity networks

This indicator examines the existing networks within a settlement, like self-help groups, women’s savings group, or any informal collectives. Often, there are federations in a settlement which could generate solidarity among people during crisis situations, like an eviction notice. Such networks act as an important determinant of security levels in the settlement. Pimple and John (Citation2002) analyze a number of cases within Mumbai where organizations participated in varied capacities, like filing petitions to activism on streets, that considerably shaped the future of those settlements and positively influenced people’s security of tenure.

3.1.4 Location primacy and expected tenability

Location of a settlement in dense urban areas becomes a key determinant of PTS. Often, settlements located close to central areas in a city tend to exist under the fear of eviction to peripheral areas. In addition, the morphology of a place becomes another significant factor that can generate or repel attention. For instance, a settlement located in a low-lying area with continuous waterlogging might have different levels of PTS and de facto security owing to lesser or speculative market pressure. Using specific cases within Delhi, Kundu (Citation2002) argues how an upcoming infrastructure project in a settlement can threaten the perceived security of inhabitants.

3.1.5 Community awareness

Awareness of a community about the socio-political context of their settlement is an important determinant of PTS. Often, the awareness can lead to a surge in community engagement and/or more conflicts, leading to varied cohesion-levels between households. An ideal outcome of awareness could be a collaborative engagement for a common cause which comprises of community representatives like the youth, women, and the elderly. Bridging this information and awareness gap through collective efforts can push people to raise the right concerns and demand their rightful entitlements. Presence or lack of such efforts can influence the PTS levels in any settlement.

3.1.6 Existing policy provisions

Government regulations and policies are one of the few indicators to gauge all the three forms of tenure security: de jure, de facto, and PTS. For instance, in the Slum Networking Project in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, when people were given a no-eviction guarantee for ten years by the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation but without any titles, empirical studies showed how the levels of PTS increased dramatically for many settlements (Kundu Citation2002; Das and Takahashi Citation2009). A legal provision (de jure), even in the absence of title possession, led to varied perceptions within people and furthered a de facto security over time. Specific to the Indian context, the decentralized governance structure which encompasses co-responsibility at the central, regional, and local levels can significantly influence PTS and de facto tenure security; especially in the cases where only a few are aware of some legal provisions while others are ignorant.

3.1.7 Access to basic services, infrastructure, and identity documents

Access to basic services like water, sanitation, and electricity can influence PTS amidst communities. The PTS levels would vary depending on the source of procuring these, whether through the State or other ‘illegal’ channels. As far as other social infrastructure goes, like health and education facilities, PTS levels are a function of the ease of access. Often, uncomplicated access to a nearby government hospital can influence people’s decision to stay in their settlement owing to the secure feeling in times of crisis. Reflections from Gandhinagar, Gujarat, by Nakamura (Citation2016) shows how communities push for the installation of water taps which can give them receipts for use as ‘residential proof for participation in government programmes’ (p. 160). In 1976, when Mumbai’s slum census happened for the first time, the government issued photo-passes to people ‘that shielded them from impromptu evictions and entitled them to the provision of basic services’ (Pimple and John Citation2002, p. 78).

3.1.8 Political patronage

Politics is one of the major drivers for determining the history and future of a settlement while having an impact on people’s PTS. It is a common occurrence in metro cities in India that the local councillor would ensure no-eviction to the residents of a settlement while expecting their votes in return. Some residents also try to use this relationship to improve their PTS. For instance, they would invite a local politician for the inauguration of a community centre or as a chief guest for a local event. Kundu (Citation2002) reinforces this point by highlighting how people establish a form of ‘relationship’ with the local leaders while regular visits by these politicians ‘give signals to these colonies’ that they are safe and not likely to be evicted (p. 155).

3.1.9 Market pressure

Land markets and the surge in land values influence of tenure security, both de facto and perceived. In dense urban areas, real estate pressure is a key determinant in the PTS levels of settlements. This indicator has a correlation with the ‘location primacy’ indicator. For instance, being in a downtown area and surrounded by commercial parks can induce lower levels of PTS for two reasons: the central location of the settlement, and the speculative pressure by the developer if the commercial park needs to expand its territory (de facto). When the major recognized and acceptable tenure form is individual registered property, all ‘other’ forms of tenure face a continuous threat ‘ready to be occupied at any moment’ and becoming ‘new land reserves for rent extraction’, thereby affecting inhabitants’ PTS levels (Rolnik Citation2019, p. 125).

3.1.10 Type of land ownership

Depending on the context of informal settlements, landownership can primarily be public or private, and the degrees of PTS can vary accordingly. On public lands, there is often a factor of the ‘welfare’ State which prevents it from acting in a certain way; while on private lands it is often about finding the actual landowner and making negotiations. Within this binary of public and private, complications arise when multiple landowners claim stake on a singular piece of land. For instance, in Mumbai, there are settlements that partially exist on central government lands, like the Railways or the Airport Authority, and the state government lands. In the case of Delhi, Kundu (Citation2002) shows how certain colonies feel secure despite the recent evictions due to the ‘nature and lack of clarity regarding the land-owning agency’ (p. 150).

Within the framework of PTS indicators, certain caveats must be noted:

The indicator list is not a linear checklist but an expansive one. Depending on the local specificities, certain indicators have more weight and the permutation of a few might be more intense in influencing PTS levels in that settlement. Thus, it will be necessary for this approach to be applied with a basic degree of local knowledge.

It is important to not view the framework in a causal and linear way. There can be several possibilities where the causality between the indicators influencing the PTS can be reversed. So, PTS can itself be one of the indicators which can cause varied intensities of other indicators.

4 Case studies and measurement scale

To apply the theoretical framework on the selected settlements (described later), the author’s method is based on first-hand qualitative interviews. From Feb 2018 to Aug 2019, the author conducted 150 interviews in the settlements of Mumbai, Maharashtra, and Jaipur, Rajasthan while working on a project with Tata Centre for Development at UChicago. The main parameters used for final site-selection were land ownership, settlement’s age, type of structures present (kaccha, semi-pucca, pucca), location, access to basic services and infrastructure, and representativeness of the selection with respect to the other settlements in the city. In the selected sites (three in each city; see ), detailed qualitative interviews with 25 respondents per site were conducted. The learning from those conversations are mapped and analysed ahead. The interviews had questions ranging from access to services, land and homeownership, to possession of any identity documents which are relatable to different PTS indicators.

For the representation of the analysis, the author uses spider charts to map the intensities of PTS indicators – using a self-defined measurement scale (see ). The primary reason for using spider charts (sometimes also called radar charts) as compared to two-dimensional linear graphs is to better convey the interconnected nature of different indicators. This tool functions as a guide to gauge the performance of PTS indicators in the selected sites.

Table 1. Measurement scale for the PTS indicators. Source: Author.

4.1 Mumbai, Maharashtra

The three sites chosen in Mumbai were Sarvodaya Nagar, Kaula Bandar, and Ambojwadi.

4.1.1 Sarvodaya Nagar, Bhandup

More than forty years old, Sarvodaya Nagar is a settlement in Bhandup with approximately 2200 houses, most of which are pucca. This notified settlement represents many other settlements in Mumbai from the perspective of private landownership (where almost 50% of Mumbai slums are on private land), the internal formation of societies (both registered and unregistered), and the distribution of spaces. People here have a regular water supply, electricity connections, and toilet facilities.

4.1.2 Kaula Bandar, Mazgaon

More than forty years old, Kaula Bandar is a settlement in Mazgaon comprising of around 5500 houses, of which most are semi-pucca. This non-notified settlement represents other settlements in Mumbai which are non-notified on the port-trust (or other Central Government) lands and where there is a conflict between land authorities. Although this is on Central Government land, the State or the municipal agencies intervene here based on their interests. People have no legal water-supply, electricity, or access to community toilets.

4.1.3 Ambojwadi, Malad

Around twenty-five years old, Ambojwadi is a settlement in Malad comprising around 12,000 houses, most of which are kaccha. This non-notified settlement represents those kaccha settlements in the city which have encroached upon the State Government lands, or in areas which are demarcated as ‘No Development Zone’, or those settlements where people came post eviction from various parts of the city. People have no legal water-supply or electricity, and there are hardly any community toilets to meet local requirements.

4.2 Jaipur, Rajasthan

The selected sites in Jaipur were Parvati Colony, Jawahar Nagar, and Gurjar ki Thadi.

4.2.1 Parvati Colony, Shastri Nagar

More than thirty years old, Parvati Colony is a settlement/ basti in Shastri Nagar comprising of around 583 households – of which most are pucca. This notified settlement, where almost everyone has a patta,Footnote3 represents such settlements in the city which have got patta or house ownership. This gives them the authority to own the property and upgrade it as per their necessity. Having a patta gives people a permanent address. People here have regular water supply, legal electricity connections, and toilet facilities.

4.2.2 Jawahar Nagar

More than thirty years old, Jawahar Nagar is a settlement comprising of 10,000 houses – of which most are semi-pucca. This notified settlement, even though without pattas, is partly on forest department land (Central Government) and State Government land. It represents those bastis in Jaipur which are 25–30 years, have not received patta, and lack services. People have individual water supply along with electricity lines. Many houses have toilets.

4.2.3 Gurjar ki Thadi

Ranging from ten years to thirty years old patches, the settlement at Gurjar ki Thadi comprises of around 450–500 houses – of which the focus here is on the kaccha part of the settlement. This non-notified settlement, primarily on privately owned land, is representative of many households who came to Jaipur 10–15 years ago and whose houses have been demolished multiple times in the past 2 years and bastis with landownership disputes. People have no legal water-supply and electricity. Few toilets have been built under the government scheme, but people mostly relieve themselves in the open due to cleanliness issues.

4.3 Measurement scale for PTS Indicators

The measurement scale shown in is based on the author’s interpretations of residents’ views and site observations, primarily derived using qualitative methodology. Based on a spectrum, the lower number represents a lesser role of that particular indicator which, in turn, accounts for lesser PTS levels in a settlement. For instance, an active presence of solidarity networks in a settlement would translate into a stronger PTS and it should, thus, have a higher rating on the scale of 1–5.

With regards to the application of this method, there are a few limitations:

While gauging the PTS in any settlement, the defined indicators do not have a specific chronology in terms of their relevance. These indicators are incumbent upon local factors, which would determine the intensity levels of PTS in that context.

The measurement scale defined for all the indicators in the author’s framework is subjective in nature, and to make concrete and generic conclusions is not within the ambit of this research.

Not all the indicators have a strong measurable quality. In case(s) where an indicator cannot be measured on a linear scale, it is not included in the spider chart analysis. Yet, that does not make that/those indicator(s) less important in influencing the PTS.

High on the measurement scale of 1–5 does not have a causal relationship to high PTS always and hence cannot be taken as a generic scale. The measurement scale for any indicator will vary, depending on the political economy of a place.

5 Analysis and Findings

The theoretical framework is used to analyse the selected sites using spider charts as the primary analytical tool. Based on site inferences and using the data mapped in the form of spider charts, the author identifies specific gaps that influence security of tenure. The graded part in the spider charts, within the indicators, visually represents the PTS which people experience in a particular settlement.

This section is broadly divided into three parts:

In the first part, six settlements are analysed – three in Mumbai and three in Jaipur – using the proposed framework. For the scope of this analysis, the focus is on the primary indicators and how they influence PTS in varying intensities. Here, understanding the indicators’ behaviour in relation to other indicators is equally important.

This will be followed by the intra-city analysis, where the PTS charts of all three sites in each of the cities are overlapped to do a comparative study.

In the final part, the above findings are deployed to analyse the performance of PTS indicators at a city level, using an inter-city comparison between the selected settlements in Mumbai and Jaipur. It is to be noted that the specific settlements compared here are relatable in terms of legality issues, type of housing structures, and their demography.

5.1 Mumbai, Maharashtra

5.1.1 Sarvodaya Nagar, Bhandup

Sarvodaya Nagar received documentation from the State authority which gave its residents a feeling of security from being evicted. This was gradually followed by formal access to basic services like water and electricity, thus, giving them more proof in terms of documentation. This settlement is divided into several sub-societies, each comprising of minimum of 20 houses. Despite some societies being unregistered, it reflects an organized form of arrangement to work as a collective. Further, many residents come from a specific geography in Maharashtra and this socio-cultural commonality adds to the feeling of security. Leveraging this solidarity, members of various societies—along with the support of a local politician—have formed a committee to govern their potential redevelopment. This has enhanced people’s PTS, as the residents have registered themselves as a cooperative housing society and now have greater negotiating power. A major impediment, however, for a slightly low PTS is the mounting market pressure, as the settlement’s location is favourable to private developers.

5.1.2 Kaula Bandar, Mazgaon

Being more than 50 years old, Kaula Bandar’s age plays a major role in the perception of tenure security amidst its residents. Even though people have not received State recognition, many have invested in housing structures, which is reflected in their PTS levels. Several families have been here for three generations and believe this is one of the most heterogeneous neighbourhoods. Despite being segregated based on region and religion, there are different solidarity groups present which give people an enhanced sense of security. A primary reason for low levels of PTS here is the ‘illegal’ access to basic services and infrastructure, particularly water and electricity. There is a strong nexus of water mafias who not only operate from this settlement but also live here. Residents tolerate them since the State lacks in the provision of this basic need while the rent-seeking behaviour of local police has allowed this system to exist for years. This translates into a lack of documents among people which always keeps them on the edge. Also, the recently proposed overhaulFootnote4 of the area has increased market pressure which has caused many concerns amidst the residents, thus, reflected in the variation of PTS levels.

5.1.3 Ambojwadi, Malad

The location of Ambojwadi, peripheral from the core city, is a major indicator of people’s high PTS. It is a non-notified settlement and the land on which they are located is under a No Development Zone in Mumbai’s Development Plan. A couple of these factors, along with a mass demolition in 2004, keep the levels of PTS low among a lot of residents. However, a strong equation of many older residents with the local politician has kept confidence high, translating the same into the perception levels. The concerned politician has been repeatedly elected by people here since he has done a lot of improvement in this settlement while the area of Ambojwadi is one of the biggest vote banks in this ward. Limited access to basic services and infrastructure, particularly water and sanitation, has led to low levels of PTS and safety issues among women. People must reserve a specific amount from their earnings, on an everyday basis, for buying water due to lack of proportionate and regular supply by the State. Furthermore, many defecate in the open as the area is close to a swamp and there is no equivalent investment in public toilets. Such factors underwrite the absence of documents and low levels of habitat contribution, thus, leading to lower PTS.

5.2 Jaipur, Rajasthan

5.2.1 Parvati Colony

Parvati Colony is one of the few settlements in Jaipur with pattas, given by the Jaipur Municipal Corporation. This has boosted habitat contribution as many households now have a form of documentation, boosting their PTS from eviction. Although the settlement is located on a steep topography and some settlers face increasing difficulty in accessing water, the reduced market pressure keeps the PTS levels high. Thirty years ago, when people started moving here, this settlement was filled with problems around safety, kaccha housing structures, and no access to basic services and infrastructure. This is an example of how the manifestation of PTS happened post titling. Although people had better access to financing from formal banks, the amount they can borrow, however, is not fixed and dependent on a family’s income and background. Thus, there is no causality of titling with easy access to credit. One of the issues, however, is the self-contained lifestyle of families and this results in class and caste segregation. This creates variability within PTS amidst certain families.

5.2.2 Jawahar Nagar

Jawahar Nagar is one of the biggest stretches of settlements in Jaipur, abutting one of the primary roads. The prime location, ease of access to livelihood opportunities, and growing market pressure—owing to the adjacent affluent housing neighbourhood—is a major indicator for low PTS in the community. Further, there is landownership dispute for many years since this settlement expands into the forest zone which falls under the Central Government while much of Jawahar Nagar is under the land owned by State Government. However, a common factor accounted for by many people for ensuring considerable habitat contribution has been the strength of the community. Since politicians in this area are aware of these dynamics, people have an enhanced sense of PTS. Due to this confidence of not being evicted, many have gradually upgraded their houses and received formal access to basic services like water and electricity, even if piecemeal. The settlement’s age, thus, becomes an important indicator in people feeling enhanced PTS. However, there is segregation along caste lines within the settlement, even though implicit, that varies the PTS levels among different groups.

5.2.3 Gurjar ki Thadi

The settlement in Gurjar ki Thadi is a recent development in Jaipur. One of the major reasons for the extremely low PTS levels is the uncertainty around land ownership, and multiple demolitions it has witnessed within a span of 1-2 years. A part of the adjacent settlement has higher PTS comparatively since they were shifted here by the State, on account of infrastructure development in their earlier location. Thus, a strong contrast is visible between their housing structures and access to basic services. Due to its prime location, there is heavy market pressure which further decreases the PTS levels. People have repeatedly made their kaccha houses despite demolitions but have a lurking fear to make any major investment due to perpetual uncertainty. They do not possess any documentary proof and access electricity through theft. Some have taken group loans from microfinance institutions and have paid from their pockets to clear the area of debris by making the land construction worthy. Despite the least PTS amidst people, they are hopeful of an incremental upgradation in their legal status.

5.3 Intra-city analysis and findings

Overlapping spider charts of the three selected settlements gives a comparative picture of PTS within Mumbai and Jaipur (see ).

Location plays a significant role in defining communities’ perceptions regarding their settlement. Ambojwadi’s low score on location tenability is reflected in low PTS as compared to Sarvodaya Nagar. However, having lesser market pressure than Sarvodaya Nagar and Kaula Bandar, Ambojwadi shows better PTS. Stronger housing structures and better access to water and electricity have a correlation with enhanced PTS, as seen in Sarvodaya Nagar. While in Parvati Colony in Jaipur, a major variation with the other two settlements is through the indicators of market pressure, identity documents, habitat contribution, and access to basic services and infrastructure. What is also evident is the higher levels of political patronage exhibited by Jawahar Nagar compared to Parvati Colony. The latter is much secure due to the possession of titles and thus the PTS levels remain high. The settlement at Gurjar ki Thadi fares exceptionally low on multiple indicators as compared to the other two except the types of livelihood opportunities people possess. This is owing to its location that retains PTS amidst people, even after multiple demolitions it has faced.

In both the cities, the overlapping of the spider charts shows varying behaviour of the same indicator within selected settlements. Thus, the context becomes a major determinant of PTS in a settlement. By locating the intensities of graded portions in the charts, one can determine the specific indicators in each settlement and use that as a lens to gauge PTS. Comparative analysis at an intra-city level provides nuances about one community feeling more or less secure than others. In fact, some indicators might function similarly in two different settlements. In that scenario, the intensities of other dissimilar indicators then become a better guide in understanding the PTS levels of those settlements.

However, the indicators’ understanding remains skewed if only analysed from the intra-city lens. For more nuanced insights on how these indicators behave in determining PTS, it is important to understand inter-city comparisons.

5.4 Inter-city study

In this final section, the spider charts of the same settlements are analysed at an inter-city level. A primary reason for this is to understand city dynamics while gauging the PTS for a settlement. For the scope of this analysis, the spider charts of the settlements which have similar characteristics are overlaid, each in Mumbai and Jaipur. These similarities are primarily based on the legality aspects, habitat contributions, landownership, access to basic services, and the presence of identification documents. Thus, as seen in , and , the spider charts overlaid are of Sarvodaya Nagar and Parvati Colony, Kaula Bandar, and Jawahar Nagar, Ambojwadi and Gurjar ki Thadi – respectively in Mumbai and Jaipur.

Some visible patterns stand out in the three (, and ) overlapped spider charts:

The PTS indicator that determines the cohesion levels – across caste, religion, and class – scores high in Mumbai. A broader reason for this can be a higher population and heterogeneity across the city, added to intense real estate pressure. Further, the radius of migration in Mumbai is not contained within Maharashtra but across the country, owing to the availability of livelihood opportunities. Owing to the shortage of space and burgeoning land prices, the adaptability of different groups increases. As for Jaipur, many migrants are from within Rajasthan or the adjacent state of Gujarat. Furthermore, due to lesser heterogeneity, the role of caste in segregation within the neighbourhoods is very strong, accounting for reduced PTS.

From the perspective of political patronage, variations in the spider charts are reflective of the local dynamics in the specific neighbourhood and city. For instance, the political patronage in Sarvodaya Nagar and Ambojwadi in Mumbai is higher than Parvati Colony and Gurjar ki Thadi in Jaipur. A primary reason for this behaviour is that both the settlements in Mumbai are older and have developed certain political affiliations over time, which accounts for higher PTS. In Sarvodaya Nagar, people have also formed a collective to further the idea of self-redevelopment, which is unlikely without a robust political connection.

Habitat contribution patterns are similar in each of the three charts (, and ). It is a two-way relation. People who feel more PTS can invest in housing, like in Sarvodaya Nagar; or people who invest in housing boldly, irrespective of any documents, feel higher PTS post-facto, as observed in Kaula Bandar and Jawahar Nagar. Similar patterns are seen with respect to investment in basic services and infrastructure. For instance, in Kaula Bandar, people have two sources of electricity – an official source that generates a bill and gives them a form of a secure document while the other is a cheaper source which they use for primary utility.

6 Conclusion: assessing Perceived Tenure Security (PTS) as a step towards inclusive housing

Visiting the initial premise, the overreliance on property titles as a one-way system of increasing tenure security reinforces the one-dimensional understanding of social justice, primarily from the lens of ‘distribution’ or ‘redistribution’. Evaluation of urban poverty must not ‘only’ be in the form of measuring people’s physical assets. Using the list of indicators in the framework, the author goes back to the idea of ‘recognition’ (Fraser 1998). Only when the distribution and recognition aspects of PTS work interactively, can tenure be comprehensively understood. Two characteristics of indicators are important to identify the PTS in a settlement:

Intensity of each indicator.

Dependency chain within various indicators, that is, the permutation.

However, non-causal thinking – that more graded portions lead to more PTS – is also important to note. Strongly dependent on the socio-political factors, these indicators will have varying intensities and causal relationships with other indicators, when determining the PTS experienced by people. The result, then, might not follow the measurement framework defined in this research, all the time.

In Sarvodaya Nagar, access to government-supplied basic services becomes a strong indicator in determining PTS amidst people, while the contrary holds true in Ambojwadi where people still must pay for their water access every day. So, can there be an incremental approach for Ambojwadi to potentially boost its PTS by striving for government-recognised water supply rather than directly fighting towards demanding property rights? In Kaula Bandar, the indicator of landownership becomes critical since the authority on that land stays with the Central Government which has neglected it over many years. So, can an incremental step for enhanced PTS be towards finding a negotiating ground between the State Government and the Central Government? Thus, can certain indicators be tapped into, to incrementally nudge a settlement towards better PTS?

Through this research, the attempt is to arrive at a method in deciphering and representing the complexity of urban land and housing tenure security. Evaluating the defined indicators to gauge PTS can, first, help to identify the context better and determine the gaps that exist; and second, nudge towards designing permutations within the identified indicators along with the necessary intensities. This can lead to a robust plan for need assessment to advance housing security. Better tenure security, when thought through such an incremental approach of upgrading tenure security, has multiple advantages at different scales:

6.1. Macro scale

This can nudge policymakers and State representatives to think beyond a unidirectional solution of land titling or distribution of titles. There is a need for institutional arrangements and concomitant policy reforms that strive for equilibrium between resource-distribution and need-recognition (Fraser 1998). The approach, then, must be centred on incrementalism of tenure security by a variety of paths, giving attention to the relevant indicators. Alternatives like community land trusts, communal titling, no-eviction guarantees, self-redevelopment, etc. should get space in political discourse.

6.2. Micro scale

This can nudge communities themselves to better understand their settlements and better calibrate their activism. In the process, they can share knowledge and the abovementioned alternatives. This could open room for people to gradually overcome short-term crises while simultaneously planning long-term strategies. Even at the scale of NGOs and CBOs, people’s co-option would reduce when their perceived security is self-generated.

Understanding perceived tenure security, and particularly the indicators that influence this perception, is critical for restructuring the normative thought-process towards housing solutions. It allows space for the recognition of a range of land tenure relationships and social contracts that already exist in low-income housing settlements. Having a tool to measure an abstract concept like security can potentially lead to a granular and contextual understanding of housing inequalities, thereby adding a small step towards an inclusive urban development process.

Acronyms

BC Bank Correspondence

BPT Bombay Port Trust

CBO Community-Based Organization

DFID Department for International Development

GLTN Global Land Tool Network

JMC Jaipur Municipal Corporation

NGO Non-Governmental Organization

UN United Nations

PTS Perceived Tenure Security

ROSCA Rotating Savings and Credit Association

Glossary of terms

Basti: A Hindi word that implies a settlement mainly inhabited by poor people. Recently, it has been used in the discourse of urban studies as a replacement to the word ‘slums’.

Caste: A social stratification system prominently used in the context of Hinduism in India. The system places a strong emphasis on hierarchy wherein certain people are considered superior and with better social status than others.

Chawls: A two to three storey residential building with separate tenements, a common passage and toilet services along with an open courtyard, referred here in the context of mill-workers’ housing in Mumbai.

Cooperative Housing Society: A legally registered association consisting of members from one or more residential building in an area.

Kaccha: Kaccha means weak; in this research the term refers to houses made from weaker materials like thatch, tarpaulin sheets, and gunny bags.

Notified areas: These are specific areas in the town or city ‘notified’ as ‘Slum(s)’ by the government have legal recognition, while the non-notified lack legal recognition.

No Development Zone: Under the Draft Revised Development Control Regulation 2034 of Mumbai, parcels of land have been reserved under the No Development Zone, which can include ecologically sensitive zones where the land cannot be developed for commercial purposes.

Patta: A patta is a legal document issued by the Government that conveys about the ownership of a particular property and about the person who is considered to be the owner and has the rights to that property. It is often known as ‘Record of Rights’.

Perceived Tenure Security: The perceptions or feelings of people towards their land and housing tenure.

Photo Passes: These are the identity cards that were issued to dwellers in Mumbai after the first slum census in 1976 to prevent eviction and provide access to basic services.

Pucca: Pucca means strong; in this research the term refers to houses made from strong materials like brick and concrete.

Acknowledgements

This paper is derived from the author’s postgraduate dissertation as a part of MSc. Urban Development Planning program (2019-’20) at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College London. He would like to acknowledge Ruth McLeod and Geoffrey Payne for their supervision and encouragement for this research. The author is also grateful to Anup Malani and Adam Chilton from University of Chicago who gave him an opportunity to work on their ‘Quality of Life in Indian Slums’ project—the basis of which the ground learnings are reflected in the data analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rohit Lahoti

Rohit Lahoti is an urban development practitioner based in Mumbai, and has been working as a consultant and on an initiative that intends to provide technical assistance among low-income communities in India, to equip them to actively participate in planning, and designing their housing, on the lines of self-development. He completed his post-graduation from The Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College London, while his research interest primarily lies in exploring the intersection of tenure security, and land and property rights.

Notes

1 The author has consciously chosen to avoid the terminology of ‘slums’ or ‘informal’ or unrecognised housing but to use ‘settlements’ – except when citing authors and where it has been used officially.

2 Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY) was a centrally sponsored scheme launched by the Indian Government in 2009 with the core vision of a ‘Slum-Free India’ with the delivery of property rights to slum dwellers.

3 A patta is a legal document issued by the Government that conveys about the ownership of a particular property and about the person who is considered to be the owner and has the rights to that property. It is often known as ‘Record of Rights’.

4 Mumbai’s Eastern Waterfront is proposed for a complete redevelopment where a lot of public land under the developer’s eye.

References

- Angel S. 1983. Land tenure for the urban poor. In: Angel S, Archer R, Tamphiphat S, editors. Land for housing the poor. Singapore: Select Books; p. 110-142.

- Banerjee B. 2002. Security of tenure in Indian cities. In: Durand-Lasserve A, Royston L, editors. Holding Their Ground: secure Tenure for the Urban Poor in Developing Countries. London: Earthscan Publications Limited; p. 37–58.

- Bhan G, Anand G, Harish S. 2014. Policy Approaches to Affordable Housing in Urban India: problems and Possibilities. Bangalore: Indian Institute for Human Settlements.

- Bhan G, Goswami A, Revi A. 2017. The intent to reside: residence in the auto-constructed city. In Bhan G, Srinivas S, Watson V, editors. The Routledge companion to planning in the Global South. Routledge. p. 255-263.

- Boonyabancha S. 2019. On ‘being collective’: a patchwork conversation with Somsook Boonyabancha on poverty, collective land tenure and Thailand’s Baan Mankong programme. In: Pérez-Castro B, editor. Radical Housing Journal. p. 167–177.

- Burgess R. 1982. Self-help housing advocacy: a curious form of radicalism: a critique of the work of John FC Turner. In: Ward P, editor. Self-help housing: a critique. London: Mansell; p. 55–97.

- Centre for Urban Equity. 2010. Land Tenure Manual for Slum-free Cities. Ahmedabad:CEPT University.

- Das AK, Takahashi LM. 2009. Evolving institutional arrangements, scaling up, and sustainability: emerging issues in participatory slum upgrading in Ahmedabad, India. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 29(2):213–232. doi:10.1177/0739456X09348613.

- De Soto H. 2000. The mystery of capital: why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere. New York: Civitas Books.

- Desai R, Mahadevia D, Sanghvi S, Vyas S, Malek R, Malek M. 2016. Bombay Hotel: urban Planning, Governance and Everyday Conflict and Violence in a Muslim Locality on the Peripheries of Ahmedabad. Ahmedabad: Centre for Urban Equity.

- Fraser N. Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, recognition, participation. Berlin: WZB discussion paper.91998

- Fainstein S. 2014. The just city. International Journal of Urban Sciences. 18(1):1–18. doi:10.1080/12265934.2013.834643.

- Ghertner DA. 2012. Nuisance Talk and the Propriety of Property: middle Class Discourses of a Slum-Free Delhi. Antipode. 44(4):1161–1187. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00956.x.

- Gilbert A. 2002. On the mystery of capital and the myths of Hernando de Soto: what difference does legal title make? International Development Planning Review. 24(1):1–20. doi:10.3828/idpr.24.1.1.

- Habitat for Humanity International. 2017. Strengthening land tenure security for urban poverty reduction in Asia-Pacific. Manila:GLTN.

- Harvey D. 1993. Class relations, social justice and the politics of difference. In: Place and the Politics of Identity. p. 41–66.

- Kundu A. 2002. Tenure security, housing investment and environmental improvement. In: Payne G, editor. Land, Rights and Innovation: improving tenure security for the urban poor. London. ITDG Publishing; p. 136–157.

- Lefebvre H. 1968. The right to the city. Vol. 3. Paris: Anthropos.

- Lemmen C. 2013. The Social Tenure Domain Model: a Pro-Poor Land Tool. Copenhagen: International Federation of Surveyors (FIG).

- Mahadevia D. 2010. Tenure security and urban social protection links: india. IDS Bull. 41(4):52–62. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00152.x.

- mRolnik R. 2020. Building territories to protect life and not profit: the RHJ in conversation with Raquel Rolnik. In: Lancione M, editor. Radical Housing Journal. p.139–147

- Nakamura S. 2016. Revealing invisible rules in slums: the nexus between perceived tenure security and housing investment. Habitat Int. 53:151–162. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.029.

- Patel K. 2016. Encountering the state through legal tenure security: perspectives from a low income resettlement scheme in urban India. Land Use Policy. 58:102–113. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.016

- Payne G. 2001. Urban land tenure policy options: titles or rights? Habitat Int. 25(3):415–429. doi:10.1016/S0197-3975(01)00014-5.

- Payne G. Land tenure and property rights: An introduction. Habitat International. 28(2):167-1792003

- Payne G. 2020. Options for intervention: increasing tenure security for community development and urban transformation. In: Communities, Land and Social Innovation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Payne G, Durand-Lasserve A, Rakodi C. 2009. The limits of land titling and home ownership. Environ Urban. 21(2):443–462. doi:10.1177/0956247809344364.

- Pimple M, John L. 2002. Security of Tenure: mumbai’s Experience. In: Holding their ground: secure land tenure for the urban poor in developing countries. London: Earthscan.

- Risbud N. 2002. Policies for tenure security in Delhi. Holding their ground: secure land tenure for the urban poor in developing countries. London: Earthscan; p. 59–74.

- Rolnik R. 2019. Uban Warfare: housing under the empire of finance. London: Verso.

- Turner J. 1968. Housing priorities, settlement patterns, and urban development in modernizing countries. J Am Inst Plann. 34(6):354–363. doi:10.1080/01944366808977562.

- Turner J. 1972. Housing as a verb. In: Turner J, Fichter R, editors. Freedom to build: dweller control of the housing process. New York: MacMillan.

- UKAid. 2015. A Land Indicator for the SDGs. Land Policy Bulletin. 2.

- UNESCAP and UN-Habitat. 2008. Land: a crucial element in housing the urban poor. In Housing the Poor in Asian cities.

- UN-Habitat. 2008. Secure Land Rights for All. Nairobi:GLTN Publication.

- Van Gelder J-L. 2009. Legal Tenure Security, Perceived Tenure Security and Housing Improvement in Buenos Aires: an Attempt towards Integration. Int J Urban Reg Res. 33(1):126–146. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00833.x.

- Van Gelder J-L. 2010. What tenure security? The case for a tripartite view. Land Use Policy. 27(2):449–456. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.06.008.

- Varley A. 1987. The relationship between tenure legalization and housing improvements: evidence from Mexico City. Dev Change. 18(3):463–481. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1987.tb00281.x.

- Varley A. 2002. Private or Public: debating the Meaning of Tenure Legalization. Int J Urban Reg Res. 26(3):449–461. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00392.

- Weinstein L. 2014. The durable slum: dharavi and the right to stay put in globalizing Mumbai Vol. 23. University of Minnesota Press.

- World Bank. 1993. Housing: enabling markets to work (English). In: A World Bank policy paper. Washington DC: World Bank.

- Young IM. 1990. Displacing the distributive paradigm. In: Young IM, editor. Justice and the Politics of Difference New Jersey. Princeton University Press; p. 15–38.