ABSTRACT

Based on case studies in Dublin, Ireland, this paper examines the motives for individuals to establish community gardens therein. The paper also outlines the capacities required for community groups to successfully establish and sustain community gardens in Ireland. These capacities include the involvement of individuals with a range of expertise, the presence of supportive community groups/organisations and state agencies, and access to resources, including land. The research findings, detailed in this paper, indicate that community gardens in urban settings encounter a number of challenges, including the absence of a mechanism for community groups to access land. The article provides a framework for community groups and community organisations to develop community gardens.

Introduction

Community gardens contribute to addressing a range of environmental, economic, and social issues facing urban communities across the globe (Keeney Citation2000; Clavin Citation2011; McIvaine-Newsad and Porter Citation2013). The community gardens tend to be dependent on people with limited resources, power, and ability to influence others (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010). Furthermore, community gardens are developed by committed individuals, who commit their time on a voluntary basis (Teig et al. Citation2009). However, they consistently encounter numerous challenges including lack of support from local people and difficulties in securing funding and land (MacNeela Citation2008). Notwithstanding these challenges, academics, policy makers, and practitioners are increasingly interested in the role community gardens can play in the transition to more sustainable communities (MacNeela Citation2008; Kingsley et al. Citation2019). Although there has been extensive research on the benefits of and motives for the establishment of community gardens, limited research has been conducted into the factors required for their establishment (Ghose and Pettygrove Citation2014).

Evans and Kantrowitz (Citation2004) use social capital to refer to the ways in which capacity building in a community contributes to action. However, restricting capacity to social capital is overly constraining. There are other ‘capacities’ which can be employed (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010). For instance, Robbins and Rowe (Citation2002) say community capacity is linked to resource availability. In relation to community regeneration, Healey et al. (Citation2003) outline the importance of developing institutional capacity which they define as the power of civil society as well as the disposition to form alliances to achieve aims (Healey et al. Citation2003). And, in terms of decision making, Healey et al. (Citation2003) say capacity building relates to the act of enabling people to participate in democratic processes.

The paper examines the capacities required for the establishment and sustainability of community gardens in Ireland by focusing on community gardens in Dublin city. The paper is also concerned with the motivations for citizens to establish community gardens.

The core questions being addressed are

To what extent does Middlemiss and Parrish’s (Citation2010) conceptual and theoretical framework explain the capacities required to establish community gardens?

What are the capacities required to establish and maintain community gardens?

What are the challenges encountered in the formation and maintenance of community gardens?

What motivates citizens to establish community gardens in Ireland?

The second section outlines the literature review undertaken for this study, while the third section details the methodology involved in the research. The penultimate section details the research findings, while the final section of the paper contains the discussion and conclusion.

Literature review

Concepts

Community gardens

In relation to community gardens, the term ‘community’ refers to a group of individuals who collaborate to develop and maintain a garden in an urban setting (Jacob and Rocha Citation2021).

There are a number of descriptions of what constitutes a community garden (Guitart et al. Citation2012). The American Community Gardening Association (ACGA) considers a community garden to be a tract of land cultivated by a group of people (Teig et al. Citation2009). The shortcoming of this definition is that it does not specify characteristics relating to governance, control, or access. Unlike the ACGA definition, Ferris et al. (Citation2001) define community gardens in terms of their collective ownership, control, and access. This approach has the advantage of distinguishing community gardens from private gardens (Ferris et al. Citation2001).

Eizenberg (Citation2012) proposes an alternative perspective which views community gardens as the manifestation of the commons in an urban setting. Some academics and community garden activists view community gardens as a means to contest private ownership of land, develop alternative forms of land ownership, and to challenge the dominant neo-liberal model of urban development (Traveline and Humold Citation2010; Levkoe Citation2011). This perspective fails to consider the diverse motivations for establishing community gardens and the peripheral role that they can play in challenging the dominant model of urban development (Aptekar Citation2015).

Stocker and Barnett (Citation1998) devised a typology which divides community gardens into three categories. The first category is a group of individual plots often referred to as allotments. The second is gardens which are governed by institutions that use gardening as a means of realising their objectives. The third category is collectively organised gardens that are accessible to and benefit the public. This framework is useful in contextualising the wide array of community gardens in Ireland.

Finally, Ferris et al. (Citation2001) named eight different types of community gardens: leisure gardens; early education and school gardens; gardens targeting marginalised groups; therapy gardens; neighbourhood spaces; gardens promoting biodiversity; commercial-orientated gardens; and demonstration gardens.

Capacity

Cohen (Citation1993) defines capacity as an individual’s ability or competence to complete a task. Evans and Krantowitz (Citation2004) critiques the above definition as not taking into account the context in which the individuals live. Indeed, the capacity to undertake actions is linked to the strength of social networks within a community (Evans and Kantrowitz Citation2004). Wang et al. (Citation2012) broadens the understanding of the concept to include the level of strategic capacity within community organisations which can address the lack of resources within a community. Middlemiss and Parrish (Citation2010) combine the individualistic and collectivist focus of the above definitions. In doing so, the concept of capacity refers to the ability of members of a community, or indeed the community, itself to make changes by the ability of members of a community, or indeed the community itself, to make changes by harnessing the individual or collective resources at their disposal (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010).

Motivations for establishing community gardens

The founders of community gardens have different motivations for establishing them (Guitart et al. Citation2012). Community gardens provide a mechanism for communities to have more control of the development of the physical space associated with their neighbourhood (Irvine et al. Citation1999). Research conducted in the USA identifies gardeners joining community gardens for social reasons, including meeting people from different ethnic backgrounds, and making new friends (Teig et al. Citation2009). Glover et al. (Citation2005) cite other social objectives, such as strengthening the capacity of the community to address local issues.

Nettle (Citation2010) identifies motivations that benefit the individual, such as opportunities to engage in physical activity to improve health, and shared benefits such as fostering community engagement, growing food for distribution among members, and promoting a culture of self-reliance. Research identifies that community gardens can be started to stimulate contact with nature (Stocker and Barnett Citation1998), reduce the incidence of food poverty (Holland Citation2004), and increase biodiversity (Nettle Citation2010). It would seem from the above that social and educational objectives take precedence over food production. However, another perspective is that community gardens can contribute to raising awareness of food provenance, tackling passive consumption of mass-produced food and connecting citizens back to growing food (Hill Citation2011). Challenging the neo-liberal system is the primary reason for a cohort of individuals becoming active in community gardens (Eizenberg Citation2012).

Capacities required for community gardens

Community gardens tend to be dependent on people with limited resources and restricted ability to influence others (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010). However, there are examples of community gardens located in affluent neighbourhoods (Horst et al. Citation2017). They tend to be driven by a small cadre of volunteers who generally give a lot of their time and resources to the development of such initiatives (Seyfang Citation2007). Indeed, these individuals tend to be highly motivated and committed gardeners who provide the continuity necessary to sustain the community garden (Follmann and Viehoff Citation2015). In relation to interaction between members, Shah (Citation1996) points to the following:

Successful community organisations, including co-operatives, are concerned with ensuring inclusivity of interaction which contributes to members’ allegiance to their respective organisation

The importance of nurturing relationships between the leadership and the membership as this reinforces the effectiveness of the community organisation

Leadership is seeking to generate additional benefits for the membership

Furthermore, the leadership are predominately experienced gardeners who are willing to pass on their knowledge to less experienced community garden members (Follmann and Viehoff Citation2015). The leadership also need to have the capacity to resolve conflict, promote inclusive interaction, and establish effective governance structures (Jacob and Rocha Citation2021). Conflicts can arise if different visions for a community garden are not accommodated within the governance structure (Aptekar Citation2015). If the conflict associated with prioritising one or more visions over others is not mediated, this can have a detrimental impact on the longevity of the community garden (Jacob and Rocha Citation2021).

Thus,the core group needs to widen the membership beyond the initial core enthusiasts so that the community garden can be developed (Certomà and Tornaghi Citation2015) Personalised recruitment processes and personal appeals can be effective at recruitment (Wesener et al. Citation2020). The recruitment strategy and maintenance in participation is brought about by an association and appreciation of a place – whether this is an affinity to a neighbourhood or attachment to a specific attribute in a place (Hoffman and High-Pippert Citation2010).

The leadership of community gardens need to be able to effectively engage with local authorities and other state agencies in order to secure land, on favourable terms and funding (Fox-Kämper et al. Citation2018). In addition, community gardens need to have access to administrators who can undertake administrative tasks such as drafting reports to funders and local authorities (Jacob and Rocha Citation2021). The establishment of governance structures is an essential task (Jacob and Rocha Citation2021). Support needs to be sourced from support agencies if the leadership do not have the capacity to complete this important task. The presence of community organisations and supportive state and local development institutions can contribute to a range of barriers being overcome in the development of community gardens (Bromage et al. Citation2015). Strong relationships with community organisations and state agencies can lead to them either directly performing the role of animator of community gardens or providing funding for communities to secure the necessary expertise (Walker et al. Citation2007; Jacob and Rocha Citation2021). Positive relationships with residents where the respective community garden is based is considered important for gaining support for the community garden (Bromage et al. Citation2015).

Community gardens need to secure land with good quality soil (Wesener et al. Citation2020). Horst et al. (Citation2017) consider that the lack of permanent land tenure is a barrier to communities establishing community gardens. They also identify that land which is allocated to community gardens is often deemed a temporary use of land, which is a better use than the land being left vacant (Horst et al. Citation2017). However, community gardens based on vacant sites have little security from replacement by other uses (Horst et al. Citation2017). With regard to securing land and start-up capital, local authorities perform a critical role in the establishment of urban community gardens (Holland Citation2004). Some communities are not in a position to access land necessary to initiate and successfully establish community gardens due a deficit in expertise (Hope and Alexander Citation2008). To address this deficit, particularly in less affluent areas, the assistance of local authorities is necessary (Holland Citation2004). However, the compartmentalisation of local authorities can make it difficult for community groups, particularly those without the relevant expertise, to access effective supports from local authorities or municipalities (Hope and Alexander Citation2008). With the retrenchment of the state, there is less funding for local authorities to resource communities to establish community gardens (Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013). A high level of trust of community projects and state institutions within communities contributes to communities becoming more receptive to the development of social enterprises with an environmental focus, including community gardens (Walker et al. Citation2008). The above capacities need to be in place for community gardens to be established and become sustainable (Kirwan et al. Citation2013).

In an Irish context, research on urban cultivation in Ireland has tended to focus on the individual allotment (Corcoran et al. Citation2017). Ireland has been characterised by a growth in community gardens since the mid-2000s (Murtagh Citation2010). The country’s economic downturn in 2009 led to the growth in the number of community gardens (Murtagh Citation2010). Indeed, the economic downturn led to the availability of vacant tracts of land to locate community gardens, land which had originally been earmarked for either residential or commercial development. However, tension exists between civil society groups requiring land to locate community gardens and the demand among entrepreneurs for capitalist development (Corcoran et al. Citation2017).

In addition, local authorities have to balance the community benefits that accrue from community gardens with the requirement of generating financial returns from the sale of public land for development (Lennon and Moore Citation2019).

Local authorities perform a critical role in supporting the development of community gardens (Ricketts Hein and Watts Citation2010). In particular, local authority staff can act as promoters in securing local authority land for community gardens (Ricketts Hein and Watts Citation2010).

The increase in unemployment, associated with the economic downturn, resulted in an increased number of individuals who had time to volunteer in a community garden (Murtagh Citation2010). Corcoran et al. (Citation2017) question whether the cohort of individuals who became involved in community gardens as a result of losing their jobs view their involvement as a stop gap until there is an upturn in the economy or, alternatively, as a sustainable activity in their lives. However, community gardens require expert gardeners and the leadership needs to operate inclusively (Joyce and Warren Citation2016). Finally, civil society organisations in Ireland support the development of community gardens (Murtagh and Ward Citation2011).

Challenges in establishing community gardens

Poor soil is identified as a significant obstacle in developing a community garden (Ruysenaar Citation2013). The challenges community gardens face can be divided into those that emanate internally and those that come from the external environment (Wesener et al. Citation2020). In relation to the former, the following challenges are identified:

Absence of experienced gardeners (Fox-Kämper et al. Citation2018)

Loss of volunteers (Drake and Lawson Citation2015)

Failure to acknowledge different visions for a community garden emanating within the membership (Aptekar Citation2015)

Inability or unwillingness to promote constructive social interaction (Fox-Kämper et al. Citation2018)

Unresolved conflict (Wesener et al. Citation2020)

Absence of expertise to establish an effective system of governance (Jacob and Rocha Citation2021)

Inability of community leaders to forge relationships with key officials within local authorities (Wesener et al. Citation2020)

Challenges arising from outside of community gardens:

Utilities not connected to community gardens (Wesener et al. Citation2020)

Absence of appropriate and sufficient funding to obtain materials and equipment (Fox-Kämper et al. Citation2018)

Dearth of support agencies responsible for supporting the establishment and development of community gardens (Wesener et al. Citation2020)

Residents of the neighbourhood either unsupportive or hostile to the community garden (Fox-Kämper et al. Citation2018)

Local authorities not amenable to allocating land to community gardens (Wesener et al. Citation2020)

Land management policies influenced by neo-liberalism (Certomà and Tornaghi Citation2015)

According to Okvat and Zautra (Citation2011), accessing suitable land, acquiring sufficient volunteers, and sourcing leadership are the key challenges encountered by urban communities striving to establish community gardens. In spite of the above challenges, there is growing interest in academic, community, and policy making sectors of the role that communities can play in the transition to more sustainable societies (MacNeela Citation2008). Therefore, an examination of the capacities critical to the implementation of successful community gardens could assist communities to have a clear understanding of the resources required for their formation and for policy makers to provide the specific resources and supports required for their development (Jackson Citation2005).

Methodology

Conceptual and theoretical framework

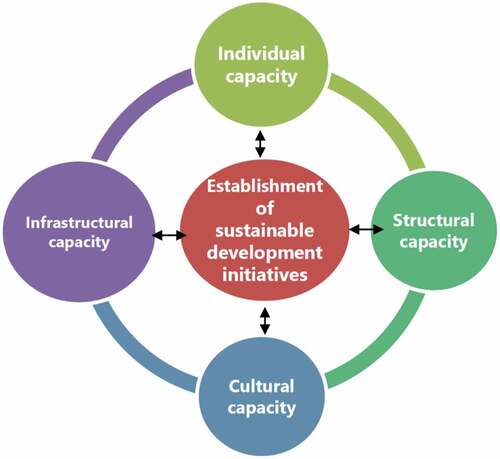

A conceptual and theoretical framework is employed which encompasses individual, structural, cultural, and infrastructural capacities that are interlinked (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010).

The first is individual capacity. Middlemiss and Parrish (Citation2010) define individual capacity as the resources held by individuals within a community. Resources comprise three components: (i) the understanding individuals have of sustainability issues, (ii) their willingness to act, and (iii) the skills they possess to act. Middlemiss and Parrish (Citation2010) assert that an individual’s social context shapes their capacity to initiate social enterprises. However, their enthusiasm can often lead to them becoming ‘burnt out’, and isolated from other residents in the community who do not share their passion for community gardens (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010).

The second is the structural capacity of a community. This focuses on the culture and values pertaining to organisations within a community that have an influence over communities’ efforts to implement social enterprises with an environmental focus (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010). Politicians are included in this category. The third is infrastructural capacity. This refers to the stock of infrastructure that is present in communities which is conducive to the drive to promote sustainability (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010). Some communities have infrastructure which makes them more conducive to the establishment of community gardens.

Cultural capacity refers to the level of commitment and openness to sustainability that exists within a community (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010). It is influenced by the historical context towards sustainability within a community.

To conclude, the research will examine the extent to which individual, structural, infrastructural, and cultural capacities explain the research findings detailed in the results section below.

should be inserted here.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework (adapted from Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010).

Case selection

Four community gardens were selected in the Dublin city area for this article. Social class in Ireland has a profound impact on people’s economic and social well-being (Breen et al. Citation1990).

The Pobal HP deprivationFootnote1 index deems electoral divisions (EDs)Footnote2 that score between −20 and −30 as being very disadvantaged, between −10 and −20 as being disadvantaged, and between 0 and −10 as being marginally disadvantaged (marginally below average).

Hence, the community gardens were selected on the basis of their socio-economic profile. The four community gardens selected are:

Santry Community Garden located in a municipal park on Dublin’s northside in an ED categorised as being affluent, according to the Pobal HP deprivation index

Sitric Community Garden, a small community garden in Dublin’s north inner city, in an ED categorised as socio-economically marginally above average

Ballymun Muck and Magic Community Garden in Ballymun on Dublin’s northside, in an ED categorised as being disadvantaged

Cherry Orchard Community Garden in Cherry Orchard in Dublin’s south west, in an ED categorised as being disadvantaged

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were held with nine key individuals who were gardeners associated with the four community gardens, and with eight individuals working for either civil society organisations or local authorities that provided supports and resources to the four community gardens. The list below outlines the number of individuals interviewed from particular civil society organisations or local authorities.

Two staff members of Ballyfermot Chapelizod Partnership

A staff member of An TaisceFootnote3

Two staff members of two civil society support organisations. One supported the establishment of Cherry Orchard Community Garden, the other provided assistance during the development phase of the Ballymun Muck and Magic Community Garden

A senior official of Fingal County Council

A senior official of the Parks Services of Dublin City Council

An elected member of Dublin City Council who assisted in the formation of a number of community gardens in Dublin

Focus groups were held with three of the committees responsible for the governance of their respective community garden. One of the committees was not meeting during the Summer when the research was undertaken. Hence, the author was not able to conduct a focus group with this committee. The interviews were held either in person or over the phone and they lasted between 40 minutes and one hour. The focus groups were held in a variety of locations and they lasted between 45 and 60 minutes.

Data collection

A list of trigger questions was used to guide the interviews, and some additional questions were posed, depending on each interviewee’s responses. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. A commitment was given to each interviewee that their anonymity would not be compromised. Therefore, quotations cannot be ascribed to individuals associated with specific organisations.

Analysis

Qualitative thematic analysis was employed to analyse the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The process of data analysis occurred inductively and deductively. In relation to the former, the themes were developed from the transcripts. The process entailed reading each of the transcriptions a number of times in order to become familiar with the data. The text of each of the transcriptions was then coded. Themes were then developed from groups of related codes (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). In relation to the latter, four of the themes – individual capacity, cultural capacity, infrastructural capacity, and structural capacity – were taken from the above theoretical framework. The relevant codes were then assigned to the four themes.

Results

The research findings pertain to interviews and focus groups with individuals associated with community gardens, representatives of civil society organisations and local authorities that provide support to community gardens. The five themes employed to categorise the research finding are: motives, individual capacity, structural capacity, infrastructural capacity and cultural capacity.

Motives

The wide range of gardeners’ motivations can be categorised into two categories, those that lead to personal fulfilment, and societal motives. Regarding the former category, community gardeners cite reasons for involvement in order to learn how to grow vegetables, realise their passion for gardening, grow organic food, and broaden their social network.

Regarding the latter category, gardeners speak about becoming involved in community gardens to promote environmental sustainability or to promote urban composting.

By composting, we could produce a lot of very valuable products in a very small space.

Motives associated with personal fulfilment is the most frequent category of motive cited by interviewees. The leadership associated with the community gardens ensure members’ motives are accommodated.

One local authority official said the motive for allocating public land for a community garden is that there would be an opportunity for residents in the locality, which is dominated by apartment blocks, to meet their neighbours and to participate in gardening.

It gives people an opportunity who live in an apartment without a garden to grow vegetables and to meet their neighbours. A lot of people have moved into the area and they could be experiencing isolation.

Another senior local authority official mentions that environmental and social factors inform his decision to allocate land for a community garden.

And I couldn’t see for the life of me why anyone would object to the initiative in terms of the environmental improvements, the visual improvements, and the possibility of people getting training and the possibility of going on for, maybe, learning a skill or being able to set up a business, I can only see benefits out of it, to be perfectly honest, I couldn’t see any negatives out of it at all.

An elected member of a local authority comments that local authorities value community gardens as a mechanism for residents to interact with each other.

Individual capacity

The theme of individual capacity is covered under the sub-themes of administrative expertise, skills, leadership, member input, and succession.

Administrative expertise

The four groups that were formed to establish community gardens possess a range of expertise. Representatives of Ballymun Muck and Magic Community Garden, Cherry Orchard Community Garden, and Santry Community Garden all refer to the importance of having individuals with administrative expertise. These individuals have the ability to effectively undertake administrative tasks, such as completing funding applications to a high standard, planning activities, and preparing accounts. One gardener said the ability to complete high-quality funding applications portrays the community garden in a good light from the perspective of local authorities. Interviewees from the Santry Community Garden and Sitric Community Garden consider having members with promotional and media expertise as being important for publicising what the garden has to offer the community. Gardeners associated with the Cherry Orchard Community Garden speak about different types of expertise being sourced from professional workers employed by the Ballyfermot Chapelizod Partnership which is a local development organisation.Footnote4 An interviewee associated with the Cherry Orchard Community Garden refers to how marginalised areas such as Cherry Orchard tend not to have access to potential members who have skills which community gardens in more affluent areas would have access to. To address this situation, local development companies may be in a position to source this administrative expertise on behalf of community gardens located in marginalised areas of Dublin.

Furthermore, an employee of a community support organisation comments on how Dublin Community Growers serves as a forum for the exchange of information between gardeners involved in community gardens across Dublin. The same interviewee emphasises that Dublin Community Growers and An Taisce may often be the only source of support for community gardens, particularly those located in economically marginalised areas of Dublin.

Skills

Several community gardeners associated with Ballymun Muck and Magic Community Garden, Cherry Orchard Community Garden, Santry Community Garden, and local development agency staff speak about successful community gardens having members with a range of different skills. They rate practical experience and expertise in growing plants as the most critical factors to the development of a successful community garden. Community gardeners in Ballymun Muck and Magic and Cherry Orchard community gardens mention that experienced gardeners are given the responsibility of devising a physical plan and design for the garden. The same interviewees mention that the leadership of community gardens needs to have the skills associated with planning the design for their garden. Planning skills are also required in devising rotas so that experienced gardeners are always present when the community garden is open. Other required skills cited by interviewees include the ability to conduct meetings effectively. Two community gardeners state that inability to moderate meetings effectively can have a detrimental impact on the governance of the community garden.

I have seen how the chairperson of one community garden consistently offered his opinion before getting the views of other committee members. This resulted in very few people showing up to meetings. This led to the community garden stagnating.

Representatives of civil society support organisations and two local authorities (Dublin City Council and Fingal County Council) mention how important it is that the process of assisting community gardeners to gain a range of skills associated with operating a community garden should not be rushed.

It wasn’t just something that you were presented with on day one, it was something that was gradual, and we built up their skills [and] confidence around managing the community garden.

Leadership

Interviewees from the four community gardens emphasise how their leaders provide continuity to the community gardens’ operations.

Interviewees from both Ballymun Muck and Magic and Santry community gardens are of the opinion that leadership is collective in nature as different individuals take on different leadership roles. An alternative model of leadership – a lone facilitator – is mentioned by an interviewee of one of the community gardens. This interviewee states that this model arises from a reluctance of members to take on leadership roles:

… trying to get somebody else, everybody would tell you how valuable this thing is but … getting somebody to take over actually has been impossible.

One interviewee from one of the community gardens mentions how collective leadership can create tensions, particularly in the early stages of the development of a community garden. The same person speaks of requiring the leaders to have the ability to compromise in relation to different perspectives that other leaders may have.

There has to be give and take among the leadership. We all have strong opinions, but you have to acknowledge when somebody else makes a better idea. The key is thinking of what is best for the community garden.

A number of interviewees from three of the community gardens and civil society support organisations identify the key functions of a community garden leader as: member engagement, the delegation of tasks and responsibility, and resolving conflict.

Member input

Gardeners from the four community gardens attribute the time members spend working in the garden as the most critical resource to attaining sustainability.

The key resource is the time individuals are prepared to work in the community garden on a voluntary basis.

According to gardeners from the four community gardens and staff of local development agencies, the amount of time invested by members in the community gardens determines what can be achieved. Interviewees speak about the presence of a core group who are prepared to work in the garden on a weekly basis as being a critical factor in the garden’s success. The core group provide continuity and leadership, and serve as role models to other members.

It was important to have a number of members who were prepared to commit amount of time per week in the garden.

Gardeners from Ballymun Muck and Magic and Cherry Orchard community gardens make the point that the formation of temporary groups can attract individuals who are not willing to commit long-term to the community garden, but who are nonetheless prepared to assist in the organisation of one-off events. Interviewees are conscious that members leave after a period of time for a variety of reasons and, consequently, the core members allocate time to recruiting new members.

Succession

Community gardeners from the Santry Community Garden and the Sitric Community Garden repeatedly speak of the challenges garden leaders encounter in developing a succession plan to ensure that a new leadership takes over the management of community gardens in the decades to come. Individualism in Irish society is one challenge. A concern is expressed that as the economy improves, members will have less time to spend in undertaking tasks associated with managing a community garden. A small number of interviewees from three community gardens believe that, when the economy rebounds, relatively novice members who joined due to losing their jobs will avail of employment opportunities. They emphasised that young members may prioritise securing paid employment so that they provide for their families. Consequently, mention was made of the importance of community garden leadership striving to maintain contact with members and discussing with them how they could continue participating in the community garden. Failure to do this could have adverse effects on the long-term sustainability of community gardens.

It is critical to have a succession so that it does not finish up relying on two or three people.

Another societal challenge noted is that Irish adults are increasingly leading passive lifestyles. One community gardener refers to the difficulty in getting one person to take over managing the community garden.

It’s been really difficult to get somebody to take that over.

According to a number of community gardeners, the challenge of leadership succession will be mitigated if community gardens became more appealing to young people.

Structural capacity

The theme of structural capacity is covered under the sub-themes of local authority, state agency promoter, and state funding.

Local authority

Several community gardeners associated with the Ballymun Muck and Magic, Cherry Orchard, and Santry community gardens note the pivotal role that local authorities can perform in the establishment of community gardens.

Furthermore, they overwhelmingly speak about the relationship with their local authority as being critical to community gardens remaining open.

They emphasise the importance of adhering to the conditions set out in the licence agreement with their local authority.

There seems to be a variation in the duration of the licence agreements with some groups being given a one-year licence while others are afforded longer-term occupancy. One community gardener suggests that local authorities should adopt international best practice of resourcing workers to support communities endeavouring to establish community gardens.

An elected member of a local authority refers to the importance of the leadership of community gardens understanding how the local government system operates. He speaks of the disadvantage that some groups encounter, if they are not aware of how the local government system operates.

None of the three groups were successful but I suspect none of them had the understanding of the political system or the influence to make their proposal come to fruition.

The same interviewee notes how a more politically astute leadership of a community garden had the knowledge to circumvent the difficulty they were having with one official in securing a tract of land. A local authority official comments on how local authorities tend not to initiate community gardens in communities because they may be perceived by community leaders as having ulterior agendas. Hence, they prefer to wait for community groups to come to them with proposals.

It’s really much better if a local community group actually suggests it because it’s their idea and there won’t be any hidden agendas there, people suspect sometimes a local authority has a hidden agenda.

One local authority official speaks of his colleagues being more inclined to support committed, hard-working, and proactive community groups than those who are less hard-working and who considered it to be the local authority’s role to prepare the land for a community garden.

State agency promoter

A civil society support organisation staff member and one local authority official speak of the critical role that is performed by a senior state agency official who is committed to the development of community gardens.

You always need that advocate in-house, say whether it’s in X or Y, someone who’s already bought into that vision and is willing to support that group of individuals.

The same local authority official mentions that a request from a senior local authority official affords it more credibility than if it emanates from a group unknown to senior management in the local authority. A number of community gardeners and civil society support organisation staff speak of how certain local authority staff access resources and funding for the community garden groups. One local authority official explains how this can work in practical terms.

… got everything all lined up, we got permissions, I think it was coming into June and we were kind of running out of planting time rapidly, so I got 1200 plants and we got them all delivered and we had a big planting day.

State funding

While noting the benefits of state funding, a small number of community gardeners mention that receiving some forms of state support poses a challenge to the community garden’s autonomy and to maintaining its values.

Three years ago, we had the option of securing CE programmeFootnote5 and co-ordinator to maintain the garden. The option was put to our members, but they said that this was our community and we do not want it run by taxpayers’ money. They articulated a belief that would have lost their sense of community and control over the garden. The members would become visitors of the centre as opposed to running the garden. This was very encouraging.

Infrastructural capacity

The theme of infrastructural capacity is covered under the sub-themes of securing land and tenure.

Securing land

Gardeners mention how crucial it is to secure land. They pursue two approaches in their efforts to secure a suitable tract of land. One approach entails engaging with their respective local authority. Some community gardeners are familiar with whom to contact in their local authority, either through working in a professional capacity or volunteering activities:

X made contact with Dublin City Council and Y [in the Council who] … made arrangements that we could use the site to set up a community garden.

The second approach involved two individuals endeavouring to identify the ownership of a nearby vacant plot of land. When the ownership could not be ascertained, the individuals commenced preparing the plot for a community garden.

Communities can spend a number of years endeavouring to secure land for a community garden. One community gardener asserts that there needs to be a mechanism in place within each local authority for allocating land to community groups. If this is in place, communities could secure land more quickly. One employee of a civil society support organisation asserts that there is a need for local authorities to compile a database of vacant land that could be used for community gardens and, in turn, would be accessible to the public.

Tenure

A large number of community gardeners and civil society support organisation staff emphasise that short-term leases create insecurity in the minds of the leadership of community gardens. The point is made that it compromises the capacity to engage in long-term planning. To address this, one local development agency employee suggests that local authorities should grant community organisations longer term licences with annual reviews built into the agreement. An individual who supports the establishment of community gardens suggests that community groups’ ownership claims on public land would be obviated if they vacate the community garden for a period of time annually.

Several community gardeners and support organisation staff comment on the challenge that this would present to the community garden leaders to start again if they are forced to give up the land. Although several interviewees acknowledge the potential conflicting demands placed on publicly owned land which is being used for community gardens, the point is made by community gardeners and the staff of support organisations that land should be reserved for community gardens.

To address the conflicting demands placed on the use of public land, a staff member of a local development agency suggests that an area of public parks be dedicated to community gardens. A local authority official said the allocation of land for community gardens would set a precedent for sporting organisations to demand space in parks to be dedicated for sports.

Public parks really are public parks, they have a special mission and really [are] sacrosanct … they should be there for the public use, they shouldn’t be, in my view, railed off. You’ll find yourself as I say, giving this piece and that piece and finding the reason for that, you’ll end up with little or no park.

Cultural capacity

The theme of cultural capacity is covered under the sub-themes of organisational maintenance, collaborative culture, norms, and inclusion.

Organisational maintenance

A number of gardeners speak of the importance of having a core group of active gardeners comprising a minimum of four members. The same gardeners speak about the core group performing a variety of functions. These include opening the garden, devising work plans, countering setbacks, dealing with conflict, ensuring members are included in activities and setting an example of undertaking physical work associated with gardening.

A group of people were willing to be committed, you know, and to be in it for the long haul through the rough as well as the smooth patches.

Collaborative culture

Gardeners attribute the success of their community garden to members working and interacting collaboratively.

And indeed, all the members must be able to work and associate with others collaboratively and make decisions regarding the future of garden in a collaborative manner.

According to a number of gardeners, collaborative culture is underpinned by a combination of consensual decision-making and lateral organisational structures. Indeed, some gardeners comment on how a collaborative style of working would be undermined if community gardens establish a hierarchical structure.

The challenge is to maintain [that] the organisation operates as a committee and makes decisions by a consensus.

At the outset, a number of community gardeners refer to the difficulties in working and interacting collaboratively when strong personalities are involved. However, the time spent in getting to know each other’s perspective and mediating differences is vital to developing a collaborative approach to working.

A number of community gardeners speak of the importance of collaboration extending to all aspects of interaction, such as undertaking gardening activities. Experienced gardeners sharing their knowledge with novice gardeners is deemed an important element of collaboration.

Collaboration can be a challenge for some individuals who are used to tending to their own private garden which does not require them to consult and work as part of a team. The overwhelming majority of members adapt to working and interacting in a collaborative manner. According to a number of interviewees, a very small cohort of gardeners find it impossible to adapt to volunteering in such an environment as they may lack the necessary social skills. The leaders in two community gardens challenge any individuals who correct other gardeners in a disparaging manner for gardening errors as these confrontations can upset those who are corrected. Gardeners frequently speak about those involved in community gardens valuing every individual’s contribution, and that other gardeners are encouraged to work at their own pace. Linked to this, members are encouraged to undertake work that they enjoy and that they have the capacity to undertake.

Community gardens promote social interaction between members through structuring specific times for members to interact with each other. The tea break is deemed the most common way for members to interact.

I’ve always said, the most important piece of equipment is the kettle.

Community gardeners mention the importance of having a facility to enable people to have a cup of tea. The tea break is regarded as playing an important role in fostering a sense of community among members. It enables new members to become more at ease with working in the community garden.

I think the social dimension and the cultivation of a sense of community within the community is primarily important.

The social dimension facilitates members to build trusting relationships with each other, which in turn contributes to members working more effectively together.

Norms

With regard to values, a number of interviewees are emphatic that discriminatory opinions concerning different social groups would not be tolerated. Gardeners emphasise the need for members to comply to a set of rules. The most common rule cited is the prohibition on members helping themselves to vegetables and fruit from the garden.

… some rules have to be, we make sure, people can’t just go and help themselves to vegetables because occasionally we’ve had people taking the piss, so we have little rules like that …

In one of the gardens, the members unanimously agree to observe a code of behaviour. In addition to the prohibition on taking garden produce, other components of the code of practice are that:

Gardeners are encouraged to share their knowledge with other members

Gardeners are encouraged to welcome new members and ensure that they do not feel isolated

Gardeners are expected to interact with all members

Inclusion

According to a number of community gardeners and state agency officials, community gardens are designed to enable people with disabilities to work in the garden. This requires community gardens to allocate funding to amend their design (to ensure accessibility), and to facilitate people with disabilities being in a position to work in their respective community garden.

Built raised beds for people with disabilities who were wheelchair users.

A representative of one state-funded organisation speaks of inviting groups working with the most marginalised social groups, including drug users in recovery, to have access to the community garden.

We would open up the garden to, say, the local addiction services as a way of helping rehabilitation.

He comments on how a minority of gardeners do not welcome this approach. Different social groups, including individuals experiencing mental health issues, are welcomed as members of community gardens. Interviewees are mindful of including and supporting members who are experiencing personal issues in a discreet manner.

Members of community gardens welcome groups of adults with intellectual disabilities and autistic children. The members speak of their community gardens being a forum for fostering inter-culturalism. A number of community gardeners believe that their community gardens assist residents from different cultures in making new friends in their neighbourhood.

Discussion and conclusions

Motives

The research findings suggest that learning how to garden and increased social interaction are the primary motives for becoming involved in community gardens. Social reasons, such as making new friends, are also identified in the literature as a motive for becoming involved in community gardens. Furthermore, both the literature and the research findings identify ideological motives for becoming involved in community gardens. The research findings point to these ideological motives tending to be environmental or ecological in nature, whereas the literature indicates that the principals of some community gardens in North and South America highlight countering neo-liberalism as a motive for becoming involved in community gardens (Levkoe Citation2011; Eizenberg Citation2012). However, no interviewees for this paper mention confronting neo-liberalism as being the primary motive for becoming involved in their community garden. Moreover, a number of motives identified in the literature are not identified in the research. These include providing an opportunity for communities to strengthen their capacity to address local issues, reduce food poverty, and become aware of food provenance.

Capacities

The literature and the research indicate that a number of factors need to be in place if community gardens are to be established and can be sustained. First, both the literature and the research emphasise how a community garden is predicated on a cadre of committed individuals possessing a range of expertise and skills. This expertise enables them to communicate effectively with the external organisations and to undertake the necessary planning associated with developing a community garden. They also provide continuity to community gardens’ operations. Second, experienced community gardeners tend to be prepared to pass on their skills and expertise to less experienced gardeners. Third, the literature and research point to the presence of supportive state and local development agencies as being critical to the continued operation of community gardens. Finally, community gardens groups need to access appropriate land to develop a community garden.

However, a small number of factors required for the establishment and continued operation of community gardens which are covered in the literature but not in the research.

The establishment of effective governance structures to govern community gardens is important.

Land allocated to community gardens needs to contain good quality soil.

The community garden needs to have an electricity and water supply.

Positive relationships with residents where the respective community garden is based are beneficial.

With regard to the research, a number of points are outlined which are not covered in the literature. First, community gardens can adopt either collective or individual approaches to leadership, with the former being more prevalent. Second, a collective and inclusive form of leadership seems to be most suited to operating community gardens. This entails making members feel included and proactively encouraging marginalised groups to gain access to the community garden. Thus, the responsibilities of community gardens’ leadership include member engagement, delegation of tasks and responsibilities, and resolving conflict. Third, member input is a critical resource in community gardens achieving sustainability. Fourth, leadership succession needs to be planned for and the research highlights the importance of investing time and resources in recruiting new members. Fifth, the research findings highlight the role of state agency personnel who promote the interests of community gardens within their respective local authority or regeneration company. This person performs a pivotal role in securing land, resources, and funding essential for the establishment and development of a sustainable community garden. The research findings highlight that these state agency personnel are characterised by being decision-makers or having the ability to persuade their line managers to allocate land for community gardens. Sixth, a collaborative culture in operating the community garden, underpinned by consensual decision-making, is considered important. Social interaction enables such a collaborative culture to be realised. Expression of discriminatory opinions is not tolerated in interactions between community garden members, making the gardens an inclusive space.

Challenges

The research identifies that community gardens encounter a number of challenges:

Securing land with adequate security of tenure

The absence of a mechanism for community groups to secure land

Securing the involvement of young people in the management of community gardens. If this is not addressed, this could lead to succession issues with the leadership of community gardens

The increasingly passive and individualistic lifestyles pursued by Irish citizens

Marginalised areas tend not to have the same access to potential members who have skills as community gardens in more affluent areas

The research points to community organisations striving to develop community gardens, in socio-economically marginalised communities, encountering a greater number of challenges and complex issues than those in more affluent communities. The research also points to there being a lack of leadership with the expertise and skills required to establish and maintain community gardens in some disadvantaged communities. Consequently, this requires the backing of local development agencies and other types of support agencies that assist residents in disadvantaged communities to establish community gardens. These support agencies have expertise in applying for grants, financial management, and organisational development, vital areas of expertise in the setting up and operation of community gardens. Furthermore, in disadvantaged communities, residents who are interested in developing community gardens may not have contacts within local authorities to make an approach to secure land. Consequently, support agencies can act as a conduit to key decision-makers in local authorities to secure tracts of land for community gardens.

Conceptual ant theoretical framework

Middlemiss and Parrish’s (Citation2010) conceptual and theoretical framework focus on the capacities required for the successful implementation of community initiatives. Although it is a robust framework, when applied to Irish communities, it may require some modification to detail the capacities required to successfully develop community gardens.

Regarding leadership, Middlemiss and Parrish’s (Citation2010) theoretical framework does not sufficiently outline the range of skills required for effective leadership. Community garden leaders, according to the research, require a range of skills and expertise: effective communication; horticulture; financial management; mediation skills; negotiation; planning; and knowledge of how to influence local government structures.

With regard to structural capacity, the research endorses the relevance of structural capacity – another component of Middlemiss and Parrish’s theoretical framework – in that local authorities and local development companies perform a vital role in allocating land and other resources to community gardens.

In relation to cultural capacity, many urban communities would not have a history of developing community initiatives with an environmental focus, and therefore values associated should be broadened to include those that focus on community solidarity, as these values arise in urban community gardens and are important in their development.

Regarding infrastructural capacities, the research points to land tenure being a cause of concern for the principals of a number of the community gardens. Indeed, community gardens located on vacant sites have little security from replacement by other uses. Local authorities offer limited protection to the land being used for community gardens while affording the organisations responsible for maintaining the community gardens an annual licence. The research points to this being an ongoing concern for the principals of community gardens.

Moreover, although Middlemiss and Parrish’s explanatory framework provides a solid basis for explaining the factors required for the successful implementation of community gardens, it does not take account of the research findings regarding the importance of organisational ethos which underpins the particular style of interaction. Middlemiss and Parrish’s (Citation2010) theoretical framework also fails to explain the relevance of organisational maintenance and the operational components essential to the establishment and maintenance of a successful community garden. In particular, it does not consider the relevance of inclusivity of interaction and the role that leadership performs in the realisation of it. However, the literature points to the importance of ensuring inclusivity of interaction between members as this contributes to the effectiveness of community gardens.

Recommendations

To facilitate community groups accessing land, each local authority could consider undertaking the following actions:

An audit of sites that could be used for community gardens that are not earmarked for other uses

The allocation of a portion area of a number of parks for use as community gardens

Designate a number of their staff with responsibility for liaising with communities that are interested in developing community gardens

An independent support structure could assist urban communities to develop community gardens – An Taisce could be resourced to perform this role.

below highlights the level of deprivation/affluence of the electoral division in which the community garden is based and below provides an overview of the recommendations for the development of community gardens in Ireland.

Table 1. Level of deprivation/affluence of electoral division in which community garden based

Table 2. Overview of recommendations relating to community gardens in Dublin

Environmental, health and social motives for forming a community garden are articulated. However, food poverty is only mentioned by one interviewee as a motive for becoming involved in the establishment of a community garden. In an epoch where there are number of food bank initiatives in Dublin to address food poverty, it may be timely to undertake research into the potential of community urban agriculture to address food poverty in particular areas. However, food produced from community gardens is not a panacea to addressing food poverty (Pudup Citation2008). Instead, community gardens should be viewed as one measure in an array of interventions to address food poverty (Donald Citation2008).

Another area of research would be to examine the extent to which community gardens are grass roots initiatives.

Acknowldgement

The author is grateful to the Golden Jubilee Trust Fund for sponsoring his PhD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gerard Doyle

The author has 27 years’ experience of working in community development and social enterprise development. He has worked for an area based partnership company, a community development network in five communities in Waterford City, and Waterford LEDC, Ireland’s first not-for-profit company involving the community and the corporate sector. He is currently a lecturer in Environment and Planning, Technological University Dublin. He holds an MSc in Local Economic Development from the University of Glasgow. In 2020, he was awarded a PhD on the role social enterprise can play in the transition to more sustainable local economies. He has published several articles in peer-reviewed international journals including the Journal of Resources, Conservation and Recycling and the Journal of Co-operative Studies.

Notes

1. The index provides a method of measuring the relative affluence or disadvantage of a particular geographical area using data compiled from various censuses. A score is given to an area based on a national average of zero and ranging from approximately −40 (being the most disadvantaged) to +40 (being the most affluent).

2. Electoral Divisions (EDs) are the smallest legally defined administrative areas in the State for which Small Area Population Statistics (SAPS) are published from the Census. http://census.cso.ie/censusasp/saps/boundaries/eds_bound.htm

3. An Taisce is a charity which aims to conserve Ireland’s natural environment and built environment.

4. The Ballyfermot Chapelizod Partnership is one of 38 local development companies in Ireland established to address unemployment and disadvantage within a designated catchment area.

5. Community Employment is an employment programme which helps long-term unemployed people to re-enter the active workforce by breaking their experience of unemployment through a return-to-work routine. The programme assists them to enhance and develop both their technical and personal skills which can then be used in the workplace.

References

- Aptekar S. 2015. Visions of Public Space: reproducing and resisting social hierarchies in a Community Garden. Sociol.Forum. 30(1):209–227. doi:10.1111/socf.12152.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Breen R, Hannan D, Rottman D, Whelan CT. 1990. Understanding contemporary Ireland: state, class and development in the Republic of Ireland. London and Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

- Bromage B, Santilli A, Ickovics JR. 2015. Organizing With Communities to Benefit Public Health. Am J Public Health. 105:1965–1966. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302766.

- Certomà C, Tornaghi C. 2015. Political gardening. Transforming cities and political agency. Local Environ. 20(10):1123–1131. doi:10.1080/13549839.2015.1053724.

- Clavin AA. 2011. Realising ecological sustainability in community gardens: a capability approach. Local Environ. 16(6):945–996. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.627320.

- Cohen J 1993. Building sustainable public sector managerial, professional, and technical capacity: a framework for analysis and intervention. Development discussion papers. Harvard Institute for International Development, Harvard University. 473.

- Corcoran M, Kettle P, O’Callaghan C. 2017. Green shoots in vacant plots? Urban agriculture and austerity in post-crash Ireland. Intl J Crit Geog. 16(2):305–331.

- Donald B. (2008). Food Systems Planning and Sustainable Cities and Regions: The Role of the Firm in Sustainable Food Capitalism. Regional Studies, 42(9), 1251–1262. 10.1080/00343400802360469

- Donald, B.2008. Food systems planning and sustainable cities and regions. The role of the firm in sustainable food capitalism. Regional Studies. 42(9):1251–1262.

- Drake L, Lawson L. 2015. Results of a US and Canada community garden survey: shared challenges in garden management amid diverse geographical and organisational contexts. Agric Hum Values. 32:241–254. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9558-7.

- Eizenberg E. 2012. Actually existing commons: three moments of space of community gardens in New York. Antipode. 44(3):764–782. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00892.x.

- Evans and Krantowwitz E. 2004 Socioeconomic status and health: the potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annual Review of Public Health. 23(1), 303–331.

- Evans G, Kantrowitz E. 2004. Socioeconomic status and health: the potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annu Rev Public Health. 23(1):303–331. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.112001.112349.

- Ferris J, Norman C, Sempik J. 2001. People, land and sustainability: community gardens and the dimension of sustainable development. Soc Policy Admin. 35(5):559–568. doi:10.1111/1467-9515.t01-1-00253.

- Follmann A, Viehoff V. 2015. A green garden on red clay: creating a new urban common as s form of political gardening in Cologne, Germany. Local Environ. 20(10):1148–1174. doi:10.1080/13549839.2014.894966.

- Fox-Kämper A, Wesener D, Sondermann M, McWilliam W, Kirk N. 2018. Urban community gardens: an evaluation of governance approaches and related enablers and barriers at different development stages. Landsc Urban Plan. 170:59–68. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.023.

- Ghose R, Pettygrove M. 2014. Actors and networks in urban community garden development. Geoforum. 53:93–103. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.02.009.

- Glover T, Shinew K, Parry D. 2005. Association, sociability, and civic culture: the democratic effect of community gardening. Leis Sci. 27(1):75–92. doi:10.1080/01490400590886060.

- Guitart D, Byrne J, Pickering C. 2012. Greener growing: assessing the influence of gardening practices on the ecological viability of community gardens in South East Queensland, Australia. J Environ Plan Manage. 58(2):189–212. doi:10.1080/09640568.2013.850404.

- Healey P, De Magalhaes C, Madanipour A, Pendlebury J. 2003. Place, identity and local politics: analysing partnership initiatives. In: Hajer M, Wagenaar H, editors. Deliberative Policy Analysis: understanding Governance in the Network Society, (pp. 60–67). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hill A. 2011. A helping hand and green thumbs: local government, citizens and the growth of a community-based food economy. Local Environ. 16(6):539–553. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.557355.

- Hoffman S, High-Pippert A. 2010. From private lives to collective action: recruitment and participation for a community energy programme. Energy Policy. 38:7567–7574. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2009.06.054.

- Holland L. 2004. Diversity and connections in community gardens: a contribution to local sustainability. Local Environ. 9(3):285–305. doi:10.1080/1354983042000219388.

- Horst, Megan, McClintock , Nathan, Hoey , Lesli 2017 The intersection of planning, urban agriculture and food justice: A review of the literature Journal of American Planning Association 83 3 277–295 doi:10.1080/01944363.2017.1322914

- Horst M, McClintock N, Hoey L. 2017. The intersection of planning, urban agriculture, and food justice: A review of the literature. Journal of American Planning Association. 83(3): 277–295.

- Hope M and Alexander R. (2008). Squashing Out the Jelly: Reflections on Trying to Become a Sustainable Community. Local Economy, 23(3), 113–120. 10.1080/02690940802197531

- Irvine S, Johnson L, Peters K. 1999. Community gardens and sustainable land use planning – study of the Alex Wilson Community garden. Local Environ. 4(1):33–46. doi:10.1080/13549839908725579.

- Jackson T 2005. Motivating sustainable consumption: a review of evidence on consumer behaviour and behavioural change. A report to the Sustainable Development Research Network.

- Jacob M, Rocha C. 2021. Models of governance in community gardening: administrative support fosters project longevity. Local Environ. 26(5):557–574. doi:10.1080/13549839.2021.1904855.

- Jermé ES, Wakefield S. 2013. Growing a just garden: environmental justice and the development of a community garden policy for Hamilton, Ontario. Plan Theory Pract. 14(3):295–314. doi:10.1080/14649357.2013.812743.

- Joyce J, Warren A. 2016. A Case Study Exploring the Influence of a Gardening Therapy group on Wellbeing. Occup Ther Ment Health. 32(2):203–215. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2015.1111184.

- Keeney G. 2000. On the nature of things: contemporary American landscape architecture. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Kingsley J, Foenander E, Bailey A. 2019. “You feel like you’re part of something bigger”: exploring motivations for community garden participation in Melbourne, Australia. BMC Public Health. 19:745. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7108-3.

- Kirwan J, Ilbery B, Maye D, Carey J. 2013. Grassroots social innovations and food localisation: an investigation of the local food programme in England. Glob Environ Change. 23(5):830–837. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.12.004.

- Lennon M, Moore D. 2019. Planning, ‘politics’ and the production of space: the formulation and application of a framework for examining the micropolitics of community place-making. J Environ Policy Plan. 21(2):117–133. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2018.1508336.

- Levkoe CZ. 2011. Towards a transformative food politics. Local Environ. 16(7):687–705. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.592182.

- MacNeela P. 2008. The give and take of volunteering: motives, benefits and personal connections among Irish volunteers. Voluntas. 19:125–139. doi:10.1007/s11266-008-9058-8.

- McIvaine-Newsad H, Porter R. 2013. How does your garden grow – environmental justice aspects of community gardens. J Ecol Anthropol. 16(1):69–75.

- Middlemiss L, Parrish B. 2010. Building capacity for low-carbon communities: the role of grassroots initiatives. Energy Policy. 38:7559–7566. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2009.07.003.

- Murtagh A. 2010. A quiet revolution? Beneath the surface of Ireland’s alternative food initiatives. Irish Geo. 43(2):149–159. doi:10.1080/00750778.2010.515380.

- Murtagh A, Ward M. 2011. Structure and culture: the evolution of Irish agricultural cooperation. J Rural Coop, Hebrew Univ, Cent Agric Econ Res. 39(2):1–15.

- Nettle C. 2010. Growing community: starting and nurturing community gardens. Adelaide: Health SA, Government of South Australia and Community and Neighbourhood Houses and Centres Association Inc.

- Okvat HA, Zautra A. 2011. Community gardening: a parsimonious path to individual, community, and environmental resilience. Am J Community Psychol. 47(3–4):374–387. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9404-z.

- Pudup MB. 2008. It takes a garden: cultivating citizen-subjects in organized community garden projects. Geoforum. 39(3):1228–1240. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.06.012.

- Ricketts Hein J and Watts D. (2010). Local food activity in the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain. Irish Geography, 43(2), 135–147. 10.1080/00750778.2010.514733

- Robbins C, Rowe J. 2002. Unresolved responsibilities: exploring local democratisation and sustainable development through a community-based waste reduction initiative. Local Gov Stud. 28(1):37–58. doi:10.1080/714004128.

- Ruysenaar S. 2013. Reconsidering the ‘Letsema principle’ and the role of community gardens in food security: evidence from Gauteng, South Africa. Urban Forum. 24:219–249. doi:10.1007/s12132-012-9158-9.

- Seyfang G. 2007. Growing sustainable consumption communities. The case of local organic food networks. Int J Sociol Soc Policy. 27(3/4):120–134. doi:10.1108/01443330710741066.

- Shah T. 1996. Catalysing co-operation: design of self-governing organisations. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Stocker L, Barnett K. 1998. The significance and praxis of community-based sustainability projects: community gardens in Western Australia. Local Environ. 3(2):179–189. doi:10.1080/13549839808725556.

- Teig E, Amulya J, Bardwell L, Buchenau J, Marshall A, Litt JS. 2009. Collective efficacy in Denver, Colorado: strengthening neighbourhoods and health through community gardens. Health Place. 15:1115–1122. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.06.003.

- Traveline K, Humold C. 2010. Urban agriculture and ecological citizenship in Philadelphia. Local Environ. 15(6):581–590. doi:10.1080/13549839.2010.487529.

- Walker G, Hunter S, Devine-Wright P, Evans R, Fay H. 2007. Harnessing community energies: explaining and evaluating community-based localism in renewable energy policy in the UK. Glob Environ Politics. 7(2):64–82. doi:10.1162/glep.2007.7.2.64.

- Wang X, Hawkins C, Lebredo N, Berman E. 2012. Capacity to sustain sustainability: a study of U.S. cities. Public Adm Rev. 72(6):841–853. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02566.x.

- Wesener A, Fox-Kämper R, Sondermann M, Münderlein D. 2020. Placemaking in action: factors that support or obstruct the development of community gardens. Sustainability. 12(2):657–686. doi:10.3390/su12020657.

- Walker G, Devine-Wright P, Hunter S, High H and Evans B. (2010). Trust and community: Exploring the meanings, contexts and dynamics of community renewable energy. Energy Policy, 38(6), 2655–2663. 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.05.055

Appendix

Core questions used in interviews

How did the concept of a community garden in your locality come about?

What were the motivating factors for individuals to develop a community garden?

What is the primary focus of the community garden? (Social, economic, education regarding enviro-nment)

What were the essential skills/expertise required to transform the community garden from a concept to growing food?

What were the resources required to establish the community garden?

Did you require resources and supports from outside your community?

What were the challenges encountered in establishing the community garden? How were these overcome?

Has the community developed a formal organisational structure? What are the criteria for membership?