ABSTRACT

Conflicts have a strong impact on land tenure, use, distribution, accessibility, and governance; consequently, a sustainable strategy for peacebuilding requires the set-up of land-based institutional arrangements from the peace negotiation phase onwards. Based on the concept of territorial peace, these arrangements have a key role in the reconstruction of the collective, productive, and symbolic functions of the territory after conflicts, and in addressing conflict root causes related to land inequality. This paper contributes to the development of the concept of territorial peace by providing a framework for its operationalisation, based on three categories of arrangements, and testing it, to qualitatively explore and compare two comprehensive peace agreements: Colombia and the Philippines. Land may take the role of peacemaker in addressing territorial peace’s collective dimensions, especially when it is at the core of a peace agreement; however, its implementation remains volatile if it lacks trust, security, and technical capacity.

1 Introduction

The concept of sustainable development has been the imperative of international development agencies for at least the last three decades; practitioners and policymakers must move through complex relations among social, economic, and environmental development. The analysis presented in this paper is framed within the broad spectrum of the assumption that ‘there can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development’ (United Nations General Assembly Citation2015, p. 2). The interdependence between peace and sustainable development has been considerably addressed by academia in recent decades (i.e., Lederach Citation1998; Dayton and Kriesberg Citation2009), mainly with studies on justice, reconciliation, dialogue, and the reconstruction of the social fabric (i.e., Galtung Citation1969, Citation1996; Richmond Citation2012). Land has been recognised to have a central role before, during, and after armed conflicts and has been studied especially concerning land administration (Todorovski Citation2016), and as a critical step for the facilitation of political and socio-economic recovery (Huggins Citation2009; Augustinus and Ombretta Tempra Citation2021). However, when addressing the land-related conditions that sustain peace, further evidence-based research on the role of the territory as a peacemaker is required. In this scenario, territorial peace is a recently coined concept that considers the nexus between land and sustainable peace, where land plays a key role in the non-relapse of armed conflicts. The term provides an innovative contribution to peacebuilding literature, but its definition and operationalisation are rather fuzzy (Cairo et al. Citation2018) and it lacks a reference to post-conflict land governance mechanisms.

The objective of this research is twofold: firstly, to contribute to the operationalisation of the concept of territorial peace, by building upon the previous work of Peña (Citation2019), among others, and linking it to land governance arrangements in use after a peace agreement; and secondly, testing such a framework, to qualitatively explore two comprehensive peace agreements: the Colombian conflict, between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EPFootnote1) and the national government, and the Moro struggle, between the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Filipino government. Both cases are long-running intra-state armed conflicts, in which land control and management played an important role; after going through extensive peace negotiation processes, they are now in the early stage of the peace agreement implementation, hereinafter referred to as the post-agreement phase. Being aware of the complex linkages and actors embedded in each of the chosen cases, this research concentrates specifically on the institutional arrangements that, established under negotiated and comprehensive peace processes, holistically comprise land issues as a crucial element of conflict resolution and peacebuilding. Therefore, the analysis of peacebuilding actions undertaken by actors other than the national governments and the aforementioned movements is beyond the scope of this research.

The paper introduces a review of the most relevant literature regarding the post-conflict context: the relationship between peace and conflict, peacebuilding and t peace agreements , and conflict-induced land issues. Followingly, it looks at literature on land governance for peacebuilding, and at the concept of territorial peace. Moreover, it develops a framework that links post-agreement land-based policies and the different dimensions of territorial peace. Subsequently, it describes the methodological approach and the characteristics of the two selected case studies. The document concludes with a comparison of the two cases and with a contribution to the literature on territorial peace and peacebuilding.

2 Theory

2.1 Conflict and peace

Important debates have taken place around the meaning of conflict. Traditionally, it has been studied based on the dichotomy of conflict and peace, a tendency that has been slowly changing towards the definition of a continuum, in which the boundaries of the two are blurred and fed into each other (United Nations Citation2008, Citation2017). Within this approach, Galtung (Citation2009) defines conflict as the perceived incompatibility of goals pursued by different actors, be they individual or collective. For the author, a conflict does not necessarily trigger violent confrontations; nevertheless, when the perceived mismatch relates to scarce resources, particularly land, conflicts tend to escalate into armed confrontations (Gleditsch Citation1998), defined as ‘violent confrontation between two human groups of massive size that would generally result in death and material destruction’ (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Citation2018). Armed confrontations are just one of the various ways in which violence is articulated. According to Galtung (Citation2003), violence can be expressed directly, via armed confrontation; indirectly, via economic and political repression; or structurally, via structural and cultural violence. Therefore, peace is understood as a continuum that is not solely achieved via peace negotiations or agreements.

When considering peace as a continuum, a wide range of complementary actions must be in place, ranging from conflict prevention to peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding. Peacebuilding encompasses the construction of memory and truth, transitional justice and reparation, the prevention of violence and crime, the reform of the armed forces and police, the physical reconstruction, the economic recovery, and political stabilisation (United Nations Citation2008, Citation2021). Additionally, the public and private sectors, the civil society, and the international community are differently engaged across the whole continuum and may drive or sink the peacebuilding momentum according to their interests (Galtung Citation1975; Boutros-Ghali Citation1992; Chetail Citation2009; Rettberg Citation2012).

Within the peacebuilding process, the post-agreement phase refers to the period following an armed conflict when the parties have reached a peace agreement or when one side submits to the other (Arrubla Citation2003); other conflicts might still be active and not necessarily connected to the one negotiated (Cepeda Citation2016). This research focuses on two post-conflict cases, Colombia and the Philippines, that are in the early stage of peace agreements implementation: the post-agreement phase.

2.1.1 The peace agreement: from negotiation to transformative peacebuilding

A peace agreement is defined as ‘a formal agreement between warring parties, which addresses the disputed incompatibility, either by settling all or part of it, or by clearly outlining a process for how the warring parties plan to regulate the incompatibility’ (Uppsala Conflict Data Program Citation2022). The signature of a peace agreement is an incentive for the parties to either stop the violence or significantly change the way the conflict is being conducted (Weller et al. Citation2021), as well as a crucial point for establishing the foundations of the social change needed to remedy the root causes of the conflict. Nevertheless, an agreement is not necessarily synonymous with peace, especially when the negotiation and implementation of peace measures are time-consuming and hardly meet expectations (Joshi and Quinn Citation2017). However, it provides insights into the public policies that must be established to achieve sustainable peace in the post-agreement phase (Ugarriza et al. Citation2013).

Building upon a transitional justice perspective, where the peace agreement addresses retributive and restorative justice and focuses on reconciliation, accountability, and legal justice (Lambourne Citation2008), peace studies include a transformative peace perspective, that aims towards participatory, contextual, and localised peacebuilding processes. In this light, sustainable peace links historical wrongs with violence prevention by addressing structural violence, legal justice, and local ownership (Lambourne Citation2008; Lambourne and Rodriguez Carreon Citation2016), starting from democratic and inclusive peace negotiations that set the path to transform socioeconomic and economic power relationships (Lambourne Citation2008). However, not all conflict-affected or involved actors are usually invited to negotiate the peace agreements (Forster Citation2019), and the process may take instead an elitist character (Herbolzheimer Citation2015a). Despite the multiple paths to achieve it, the peace agreement is expected to seal the end of physical violence, which Galtung (Citation1969) defines as negative peace, a crucial step towards positive peace, the one resulting once structural violence is addressed (Herbolzheimer Citation2015a).

Forster (Citation2019) proposes three elements to be considered when classifying a peace agreement: the scope, i.e., inter, intra/national or sub-state peace agreements; the conflict’s phase to which they respond, i.e., pre-negotiation, ceasefire, partial, comprehensive, implementation or renewal agreements; and the contents covered, i.e., security, governance, human rights, socio-economic reconstruction, justice reform, transitional justice, implementation. Comprehensive peace agreements often tackle justice provision, reintegration, power balance, and institutional arrangements to acknowledge and amend the root causes of the conflict (Tellez Citation2019). When land is at the core of the conflict, it is expected that the peace agreement increases the overall quality of land governance, with the inclusion of land institutional arrangements agreed upon by the parties. Overall, peace agreements encounter three important challenges. Firstly, a problem of definition of the conflict as such, usually done on the number of deaths per year, leading to the exclusion of certain actors from the negotiation and the consequent failure in repairing victims (Bell Citation2010; Forster Citation2019). Secondly, the legality of the agreement, the extent to which these are differently supported by legitimised actors and legal frameworks (Forster Citation2019). Thirdly, the timespan between the negotiations and the implementation, which can exhaust the negotiation resources, increasing the risk of violent relapse or non-viability of peace-enabling conditions (Bell Citation2010).

2.1.2 The post-conflict land issues

Peace studies mostly look at land in the post-conflict phase in comparison with the pre-conflict situation; this section, consequently, uses the term post-conflict. In this phase, aspects that should be planned during the peace process come into play, such as reconstruction (referring to the physical structures damaged in the conflict), rehabilitation, integral reparation for the victims, or the role of the military forces in the conflict. The period following the end of confrontations leaves behind torn societies, with the institutional, social, economic, and security issues summarised by Ball (Citation2001) in . All characteristics affect directly or indirectly land management in all its aspects (Hollingsworth Citation2014).

Table 1. Characteristics of post-conflict countries (Ball, Citation2001)

Conflicts increase the vulnerability of people, hamper assets accessibility and destroy social, physical, and financial capital while burdening future generations with a social and economic cost (Ball Citation2001). The high number of displaced people and refugees remains one of the most relevant challenges. Access to shelter has proved to be a key factor in increasing access to food, livelihood restoration, and security. Addressing land, housing, and property (HLP) issues for refugees and internally displaced populations (IDPs) is part of the mandate of several humanitarian agencies with increasing interest over the decades (Norwegian Refugee Council & International Federation of Red Cross Citation2016). To conclude, land inequalities generate confrontations, therefore becoming the theatre for displacement and degradation; when addressing land issues in post-conflict contexts, it is key to consider land recovery holistically, from its environmental value to the economic production, to housing provision, and to the symbolic value for communities (Peña Citation2019).

2.2 Land governance for peace

Land inequality is widely recognised among academics and practitioners as a root or proximal cause of many conflicts around the world; in addition, vast literature supports the strong link between violent conflicts and the (increased) presence of land issues, land rights violations and unequal accessibility and distribution, as in the case of Rwanda (Musahara and Huggins Citation2004) or Bosnia (Jansen Citation2007), among others. Policies on land and natural resources are increasingly relevant in peace agreements, and their role for peacebuilding is included in several United Nations (UN) recommendations and resolutions, among others: the EU-UN Partnership on Land, Natural Resources and Conflict Prevention (United Nations Citationn.d.) and the UN Resolution 1325 (United Nations Security Council Citation2000).

Land governance is a complex concept analysed by different literature streams, some focused on a rather administrative and technical approach, where rights over land are instruments to capital accumulation, as highlighted by Borras and Franco (Citation2010). However, we think that is difficult to discuss land governance in post-conflict contexts without considering its socio-political dimension; for our purpose, land is not a commodity, but rather the space where socio-political interactions are shaped (Borras and Franco Citation2010), and where a ‘totally human game […] plays out over land and terrain’ (Fischer Citation2016, p. 216). Based on the definition by Palmer et al. (Citation2009, p. 9), land governance ‘concerns the rules, processes and structures through which decisions are made about the access to land and its use, the manner in which the decisions are implemented and enforced, the way that competing interests in land are managed’. Followingly, land governance involves a debate around power balance and the political economy of land, which are especially fragile in case of conflict-induced low institutional capacity, democratisation, discrimination, outdated spatial information and cadastral data, and low priority on national agenda for peacebuilding (Augustinus and Barry Citation2006). In this context, not only the content of an arrangement or reform is relevant, but also the process (Palmer et al. Citation2009). For the purpose of this research, the term land accounts for rules, processes and structures over a territory, intended as a geographical area with a political value, given by the demand of collective control, possession and administration (Stienen Citation2020).

By reviewing literature on land governance, conflict, and peace, we identify six contextual, self-reinforcing, and interconnected components of land governance. Firstly, land administration involves the infrastructures around land management, including a land information system, based on a set of information on land use, value, and tenure, through cadastral registers and maps (Enemark et al. Citation2014). Literature calls for more integration between peace treaties and land administration arrangements during the reconciliation (van der Molen and Lemmen Citation2004). Secondly, land tenure regards the type of rights held on land (Borras and Franco Citation2010; Arnot et al. Citation2011); cost-effective forms of land registration programmes are seen as crucial steps of the peacebuilding process, to reduce disputes and conflicts (Van Leeuwen et al. Citation2021). Promoted in stable conditions, land rights become a political matter during conflicts, where displacements and land grabbing impact marginalised conflict-affected populations, as refugees and IDPs (Todorovski Citation2016; Van Leeuwen et al. Citation2021). Thirdly, land accessibility regards the means of obtaining land, which can be obstructed by natural and demographic factors, as well as social and political, among others: the type of tenure, or the lack thereof, the plots’ size, land fragmentation, and the disconnection from other livelihood sources, such as transportation, infrastructure, services, water, the level of destruction of physical assets, and, lastly, the presence of land mines (Daudelin Citation2003). Fourthly, land distribution addresses skewed land concentration and the ‘entrenched power of land-based elites’ (Simmons Citation2004, p. 183), the risk of speculative land acquisition and pro-market land grabbing in the midst of post-war confusion, especially when facing weak institutions (Pritchard Citation2016), turning pro-poor policies into ‘market-friendly’ (Borras and Franco Citation2010, p. 20) reforms. Fifthly, land use is defined as the formal or informal function of a certain land cover,Footnote2 according to a given zoning plan or in disregard of it (van der Molen Citation2002). Although the impacts of conflicts on land use changes are understudied in literature (Garcia Corrales et al. Citation2019), there is evidence that conflict-driven migration, violence, and permanence of non-state actors may lead to the distortion of agricultural practices, such as the enforcement of illicit crops, the preference of seasonal instead of perennial crops (Arias et al. Citation2014), deforestation, and degradation (Aguilar et al. Citation2015). Lastly, as conflicts affect livelihood strategies by reducing financial, natural, and human capital, land-based capacity building, i.e., education support or vocational training, goes hand in hand with the reintegration of ex-combatants, the reversion of illicit agriculture, and rural development (Guarnieri Citation2003; Jaspars and O’Callaghan Citation2010; Subedi Citation2014).

Since the last 30 years, post-conflict land reforms have focused on restorative justice, through a narrow restitution approach, following a traditional Western approach to individual property rights (Alden Wily Citation2009). As armed conflicts have evolved over time, from being inter-state to intra-states conflicts and domestic unrests, often with ethnic implications, land governance should consider collective rights, agricultural land access, intra-state land grabbing and should move towards broad land and property reforms. To conclude, post-conflict land governance may be a facilitating factor for long-term peace and stability, if its rules, processes, and structures focus on fighting inequality, preventing land grabbing, achieving accountability (Todorovski Citation2016), and influencing land use and markets (Alden Wily, Citation2009).

2.3 Territorial peace: sustainable peacebuilding

The territory is the physical realm in which the conflict becomes evident, as Aron (Citation1984) would say. Following the author, the territory can be the means, the scenario and the objective of the conflict: ‘milieu, théâtre et enjeu’ (Aron Citation1984, p. 188); the first regards the territorial control over people, resources, and geography necessary for the conflict to happen, with or without violent confrontations; the second represents the scenario in which the conflicts parties confront each other, organise and develop; the third aspect relates to the motive of the conflict, when it is a question of the appropriation or reorganisation of a territory and its resources (Aron Citation1984). In this sense, a strategy that advocates peace and an end to armed confrontations should address conflict through its contextually relevant territorial dimensions.

The concept of territorial peace provides an innovative holistic interpretation of this link, entailing traditional land aspects (tenure, rights, and distribution), and including administration, governance as well as the symbolic and cultural roles of the territory. The concept has emerged precisely amid the peace negotiations between the FARC-EP and the Colombian government (Cairo et al. Citation2018). Its conceptual development is therefore highly related to the root cause of the Colombian conflict: the high inequality in land ownership, a central point during the negotiations of the peace agreement. However, given the relevant role that land, as a scarce resource, plays in other conflicts around the world, its further conceptualisation may enrich peace studies beyond the Colombian case.

Emerging literature defines territorial peace as a multilevel paradigm of transformative peace; it implies territorial renewal in light of social justice, based on the recognition of historical trends, the characteristics of conflicts, the paths of social, cultural, and environmental organisation of the communities, the definition of the direct or indirect victims of the armed conflict, and the involvement of all stakeholders to achieve land-based peace (e.g., Bautista Citation2017; Peña Citation2019). At its core, territorial peace asks the question of what needs to be changed in social spatiality to create conditions for sustainable peace (Peña Citation2019). Therefore, it promotes a transformative process of the territories that suffered, directly or indirectly, armed conflict; it advocates for the multiple dimensions and meanings that the territory has in building peace, linking land to socio-economic recovery, and, therefore, it invites to consider decentralised, bottom-up and local peace processes (Le Billon et al. Citation2020). To conclude, territorial peace is achieved through several mechanisms involving land governance, fundamental to creating conditions for a sustainable peace for all the actors affected by conflict. In this light, peace agreements set the grounds for transformative land-based policies, able to constitute a further step towards a change from pre-conflict conditions.

2.4 Conceptual framework

2.4.1 Current framework for territorial peace

Within a context of conflict and shattered institutional landscape, peace agreements set the ground for various self-reinforcing and connected institutional arrangements, impacting also on the quality of land governance (Palmer et al. Citation2009). Territorial peace, in turn, poses an innovative, holistic framework to such land-related institutional arrangements.

As explained by Cairo et al. (Citation2018), while being a significant contribution to conflict resolution studies beyond the original geographical context, the term territorial peace is rather fuzzy, and it is open to different interpretations. It goes from encompassing democratic peace, as envisioned by the Colombian High Commissioner for Peace; to a within-region peace, where the nexus urban-rural is addressed, as pursued by the FARC-EP; to the restoration of security, as intended by the Colombian police (Cairo et al. Citation2018). Overall, the concept overlaps for many actors with the idea of decentralisation of the peace efforts. The different interpretations on one side makes the validity and replicability of the concept difficult; on the other, it creates space for debate.

A valid structure of territorial peace is given by Peña (Citation2019), who claims that territorial peace should rebuild the collective functions of the territory, which are: sustainable livelihoods, considering the territory’s socio-economic landscape; identity, meaning the territory’s symbolic value and the different cosmovision around it; community (re)building, linking the rooting, permanence and encountering processes between civil society, victims, ex-combatants and institutions (public, international, private); safety, by guaranteeing the physical stability, housing and land tenure, as well as conflict non-repetition; and leisure, considering the fulfilment of basic wellbeing and enjoyment of the territory (Peña Citation2019).

While Peña’s model presents a holistic approach to the land issue in post-conflict contexts, due to its novelty, it does not yet present clear strategies and mechanisms to achieve what is proposed in each dimension. Specifically, a further step is needed to translate territorial peace’s collective functions into the post-conflict land governance mechanisms, to achieve replicability and tangibility, and to frame the complex interplay of power dynamics and interests involved in an eventual implementation of agreements based on the territorial peace framework. Acknowledging the challenges identified by Bell (Citation2010), a comprehensive agreement based on this approach may encounter important legitimacy issues, considering that measures as land redistribution may not reflect the interest of several actors. To this end, we would like to point out the role of uncontrolled land markets or market-led recovery, preferred in post-conflict contexts, in contradicting structural changes in land accessibility and distribution dynamics (Escallón Citation2021), envisioned by the peace agreement itself. Powerful national or international groups, elites, large landholders, politicians, and military forces may take advantage of the lack of governance and enforcement, promoting land grabbing at the expense of the victims, the rural population, and small landholders.

2.4.2 Proposed conceptual framework

To define the pillars and dimensions of land governance entailed by territorial peace, we propose a conceptual framework consisting of three categories.

The first category refers to Stability and Security and concerns the information accessibility, the cadastral and administrative capacity that should be in place to ensure the tenure security and compensations given to the (new) tenants. Stability is challenged by armed confrontations, which leave the spatial information disrupted and land information systems not traceable or accurate. If cadastres and government buildings are destroyed and administrative personnel unavailable, a response to HLP issues and other socio-economic services are hardly achieved (Augustinus and Barry Citation2006). These arrangements reflect not only the physical disruption but also biased land administration practices, relevant in the case of ethnic-based conflicts (Hollingsworth Citation2014). Administrative arrangements contribute to setting the ground for establishing rules of land data collection and management.

In turn, Security addresses the high rate of returnees in conflict areas and the overlap of statutory and customary tenure systems, tackling directly or indirectly issues of land security, accessibility, and distribution, in support of landless, conflict-affected displaced population and returnees. In this sense, the common debate is between land restitution or compensation, although many authors call for more customary-sensitive reforms (Alden Wily, Citation2009; Pritchard Citation2016), as valid instruments to address sustainable return, livelihood restoration, reducing disputes, abuses, and the possibility of relapse.

The second category, Sustainable Livelihood, and Identity, concerns the restoration of a cohesive society and the recovery or creation of sustainable ways of living. Under these arrangements, socio-economic assistance programs target displaced communities, ex-combatants, and vulnerable groups, by providing in-kind or financial assistance. In addition, changes in land use aim to revert conflict-led agricultural practices and conflict-induced degradation; this should be combined with land-based capacity building opportunities to enable victims and ex-combatants’ reintegration into a productive sustainable society. When returning or settling in a certain territory, beyond possessing resources and ecosystem services, it is crucial to identify and activate local knowledge, co-production of knowledge, and sense of place to avoid conflicts, increase trust and adopt new sustainable livelihood practices (de Kraker Citation2017).

Lastly, the Safety and Power Balance category considers the achievement of a renewed social contract in which all the involved actors, including the ex-combatants, have the guarantee of participation within the governance system and on land matters (Garstka Citation2010). In several cases, agreements establish disarmament phases, programs of support for ex-combatants, integration into political life, the establishment of safety buffer areas where no violence should be perpetrated, and conflict resolution mechanisms. Extremely relevant is the political power distribution, as it responds to requests of autonomy and corrective measures of pre-conflict wrongs; this may go from political autonomy on certain matters to full territorial autonomy (Tellez Citation2019).

These arrangements should be tools for long-term stability and legitimacy among all the involved actors; in the post-conflict peacebuilding phase, they are yet to implement a social and cultural change, but rather are included into policies for land governance and future sustainability. By establishing the link between land-based policies and territorial peace dimensions (), and testing them in two cases, we aim to contribute to the concretisation of the concept of territorial peace and to stimulate new narratives on peacebuilding policymaking.

To summarise, the proposed framework presents a pathway to connect land governance elements to the pillars of territorial peace, so that the latter is strengthened by the elements of the former. Stability and Security are territorial peace elements connected to a stable land administration structure, where clear responsibilities and agencies are established, together with an updated land information system, the recognition of tenure systems, the restitution of land, or its (fair) compensation. The Livelihood and Identity arrangements aim to provide conflict-affected populations and ex-combatants with sustainable land-based livelihood sources and to increase land-based capacity and know-how. Safety and Power-Balance arrangements are connected to land administrative solutions for power distribution, conflict resolution, and the identification of safe territorial entities.

3 Methodology

Building upon the above-mentioned framework, this paper reviewed the land-based policies and institutional arrangements resulting from the peace agreements in the early-stage reconciliation processes in Colombia and the Philippines. Information from secondary sources was triangulated, with three semi-structured interviews conducted with key informants from the public sector and grassroot organisations, involved in the implementation of the peace agreement in Mindanao, Philippines. As of the Colombian case, the current political context and social leaders’ assassinations posed a challenge to collect primary information, whereas the secondary data was abundant. Overall, the collection of primary data was made difficult by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. shows an alignment between the elements of territorial peace discussed above, and the corresponding institutional arrangements that belong to the land governance realm.

Table 2. Land governance institutional arrangements for territorial peace.

In the sections below, the main arrangements, resulting from the agreements in the two case studies, are presented and briefly introduced based on their contribution to the three categories of territorial peace; a full analysis on each arrangement exceeds the scope of this paper.

3.1 Case studies

While there are several examples of conflicts that were (partially) solved via peace agreements, there are a few that can be compared for their scope, stage of implementation, or content. According to the data gathered by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, the conflict between the government of Colombia and the FARC-EP, with a peace agreement signed in 2016, and the conflict in the Mindanao region in the Philippines, where the peace agreement was signed in 2014, are two intra-state conflicts that have recently shifted to a post-agreement stage, with extensive peace negotiations and less than 25 battle deaths per year (Uppsala Conflict Data Program Citation2022). Land inequality is at the core of both conflicts, and it is contextually addressed in both the peace agreements. Lastly, the peace agreements can be classified as national in their scope, post-ceasefire, comprehensive, and content-wise complex.

3.2 Colombia: land skewed concentration and unfulfilled reforms

The conflict between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP is rooted in a profound inequality between the country’s political and economic elites and the rest (majority) of the population, in accessing land, property, and state services for peasants, indigenous, and minorities, caused by mechanisms of land grabbing and dispossession (Berry Citation2017). As a result, in 2014, around 81% of Colombian land belonged to 1% of the population, and at least 40% of large landowners said they do not know the tenure regime of their land (Guereña Citation2017). Such a situation has been exacerbated by conflicts over the control of the vast illegal crops’ plantations (Ahumada Citation2020).

As an answer to such a deep inequality, based on a Marxist-Leninist ideology and with the influence of the Cold War, the FARC were created in 1964. The movement started as a guerrilla, with a military strategy that evolved, throughout the years, from strong community-based support to a drug-trafficking and land control-based power (Uppsala Conflict Data Program Citation2022). In parallel, since the 1960s, at least 34 armed organisations have operated as guerrillas in both urban and rural areas in different regions of the country, from which at least 10 took part in the peace negotiations, signed different peace agreements, and completed demobilisation and reincorporation processes (Universidad Nacional de Colombia Observatorio de Paz y Conflicto Citation2016). Nevertheless, the peace negotiation process between the FARC-EP and the Colombian government has strongly resonated as a case study in recent years given its relevance in promoting broad social transformations (Guzman and Holá Citation2019). The negotiations started in 2012, and the subsequent signing of the agreement in June 2016 in Havana marked the end of armed confrontations between the government and the country’s oldest guerrilla movement, consecrating this armed conflict as the oldest one in the Americas (Plazas-Díaz Citation2017).

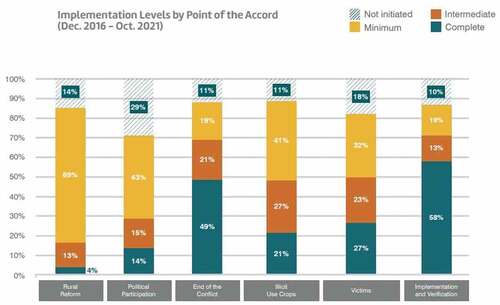

The Havana comprehensive agreement contains six action pointsFootnote3 that address the root causes of the conflict, as well as its socio-environmental consequences and the reincorporation of ex-FARC members into civil society. Given that the land inequality was the trigger for the creation of the FARC, a discussion around comprehensive rural reform, both in terms of access, titling, and use, was central to the peace process. This is reflected on the first point of the final agreement, which establishes a Comprehensive Rural Reform and is, to this date, the point of the agreement whose implementation has brought the greatest complexity and, therefore, is the furthest behind schedule (Fajardo-Heyward Citation2018; Procuraduría General de la Nación Citation2020; Peace Accords Matrix, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies & Keough School of Global Affairs Citation2021). Its poor execution is evidenced by a recent report (Peace Accords Matrix, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies & Keough School of Global Affairs Citation2021), where the implementation of each point of the agreement is compared () (). Despite the progress in terms of combatants' demobilisation, crop substitutions and institutional presence in rural territories (Fajardo-Heyward Citation2018), it has lacked two fundamental commitments: firstly, adjusting the Large-Scale Rural Property Titling Plan, which ensures participation and gender inclusion, and, secondly, the implementation of Territorially Focused Development Programs (Programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial, PDETs), further explained below.

Figure 2. Implementation levels by point of the accord (Peace Accords Matrix, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies & Keough School of Global Affairs Citation2021).

The Comprehensive Rural Reform aims at reversing the effects of the conflict and guaranteeing the sustainability of peace by improving the quality of life of rural inhabitants. Accordingly, it promotes regional integration, social and economic development, and opportunities for rural populations historically affected by the armed conflict and poverty, and it places rural development as one of the pillars of economic and social development. Its scope is national, but its implementation has been defined as progressive, starting with those municipalities with high levels of armed conflict and institutional weakness (Acuerdo Final Citation2016). To that end, it tackles in detail the diverse dimensions of existing but ineffective land and agrarian mechanisms, due to lack of resources, corruption, political will, or violence (Borja Citation2017).

Several agrarian reforms have been attempted throughout the years (Borja Citation2017), creating a complex and diverse institutional body; the Havana agreement contributes to it by strengthening existing institutional arrangements and creating new ones (Borja Citation2017). presents a classification of such arrangements, based on the authors’ conceptual framework.

Table 3. Land governance institutional arrangements in Colombia.

Some arrangements are included in the Havana peace agreement, but were part of previous negotiations; likewise, from precedents peace processes, legal mechanisms were created that still feed into the present institutional framework. This is the case of the Law 1448 of 2011, known as the (1) Victims and Land Restitution Law, an ambitious law that covers the transition to the post-conflict phase via transitional justice and victims’ compensations (Martínez Cortés Citation2013); land restitution is recognised as the preferred approach for displaced population (Congress of the Republic of Colombia Citation2011). Its success has been hampered by multiple causes, among others the protected conflict, identification of victims and of stolen land, institutional overload and low protection for the victims (Amnesty International Citation2012; Summers Citation2012; García-Godos and Wiig Citation2018) To ensure land Stability and Security, Colombia had a (2) cadastre system strongly focused, until 1980, on land taxation, as well as on the provision of geographic information (Ramos Citation2003); similarly, the (3) Autonomous Regional Corporations (Corporaciones Autónomas Regionales, CAR), were created in the 1990s to administer and ensure the sustainable use of land and natural resources. Both mechanisms were never fully implemented; the cadastre system had an administration highly centralised in the capital city, with low rural coverage, lacked sufficient technical expertise at a regional level, and was heavily affected by corruption (León and Dávila Citation2020). As for the CARs, despite their regional nature, regional powers, nepotism, and corruption led not only to the unfulfilment of its nature and aim, but also to negligent actions towards nature conservation and restoration (Montes Citation2018). In this context, the 2016 comprehensive peace agreement proposes a multi-purpose cadastre that goes beyond land registration, is decentralised in technical and administrative capacity, and understands the complex urban-rural dynamics of the country. A first important step was made in restructuring the cadastre by creating the General System of Multipurpose and Integral Cadastral Information, which, in addition to providing information on taxation, location, and size of properties, should also provide information on the land uses and economic activities, addressing not only land stability and security but also sustainable livelihood. In addition, to implement a country-wide comprehensive land reform that addresses tenure security and land distribution, the agreement creates the (4) National Land Fund in 2017, to be administrated by the National Land Agency; one million hectares have been entrusted to this fund, not yet allocated to anyone for use and ownership (Subdirección de Administración de Tierras Citation2020).

Looking at Sustainable Livelihood and Identity, the (6) Agency for the Renewal of the Territory (Agencia de Renovación del Territorio, ART), created in 2005, reinforces the mandate of the Special Administrative Unit for Territorial Consolidation (Unidad Administrativa Especial para la Consolidación Territorial), created in 2011, in charge of coordinating and mobilising public, private, and international resources to promote livelihood alternatives in areas with a presence of illicit crops. The ART is directly related to the recovery of rural territories, the provision of stimulus and technical assistance to the peasants, and the promotion of family and community agriculture. Among ART’s responsibilities, it is important to highlight the creation of the (6) Territorially Focused Development Programs (Programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial, PDETs). These are special 15-year planning and management instruments, with the objective of the stabilisation and transformation of the territories most affected by violence, poverty, illicit economy, and institutional weakness (Agencia para la Reincorporación y la Normalización Citation2021). The PDETs aim to the participatory development in 170 rural municipalities in 16 subregions that have strongly suffered the armed conflict in the country, across different pillars that tackle tenure, land use, food security, housing and infrastructure, capacity, reconciliation, and health. In the PDETs, former FARC-EP combatants are in process of reintegration into civilian life, through sustainable and productive land use and political participation (Borja Citation2017). Production activities range from agriculture to beekeeping, artisanal beer production, or textile manufacturing (Semana Rural Citation2020). As of 2020, the PDET participatory process defined more than 32.800 initiatives, of which only 21% are under implementation, most of them belonging to the pillar of rural education; overall the implementation across the different subregions faces challenges in data availability (Agencia para la Reincorporación y la Normalización Citation2021). As another form of territorial organisation, in the (5) Peasant Reserve Zones (Zonas de Reserva Campesina, ZRCs), instituted with the Law 160/1994, with the objective of ensuring socioeconomic development and land participatory planning (Borja Citation2017), peasants can self-determine their economic development to promote agriculture, food security and regulate land use and ownership (PBI Colombia Citation2018). The PDETs should strengthen the existing ZRCs and the ones in process of being constituted, and recognise their territorial organisation (Agencia Prensa Rural Citation2017), although are still perceived today as disjoint (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, & Agencia Nacional de Tierras Citation2019). Furthermore, the (8) Rural Development Agency focuses on rebuilding rural communities via technical capacity at the local level, through Comprehensive Agricultural and Rural Development Projects, and with a working group focused on peacebuilding, responding to the tasks conceived in the first point of the Havana agreement (Radio Nacional de ColombiaCitation2018; Procuraduría General de la Nación Citation2020).

Lastly, to achieve Safety and Power-balance, in addition to the PDETs, the (9) National Council for Reincorporation (Consejo Nacional de Reincorporación, CNR) was established, composed of two members from the government and two from the FARC. The CNR defines activities, timetables, and monitors the process of reincorporation of demobilised combatants. This council went beyond the Colombian Agency for Reintegration and Normalisation (Agencia para la Reincorporación y la Normalización, ARN), which was founded in 2011 with the mandate of coordinating, advising and executing the reintegration process of demobilised FARC members (Agencia para la Reincorporación y la Normalización, n.d). Due to political pressure, neither the ARN nor the CNR have fully fulfilled their functions in the post-agreement period (Murcia Citation2021).

The implementation of these mechanisms has been affected by the strong political polarisation experienced in the country, following the popular rejection of the peace agreement in the 2016 plebiscite, and the consequent adjustments endorsed by a non-participatory presidential order, leaving the door open for implementation uncertainties. In terms of peacebuilding, these instruments have been of little use in terms of both land redistribution and governance (Borja Citation2017). The PDETs, which promised to be the centre of territorial renewal in the country, have faced significant setbacks in their implementation, particularly because the current national government (since 2018) has not provided the program with sufficient budget or institutional support, especially in those Afro-descendant or indigenous territories (Peace Accords Matrix, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies & Keough School of Global Affairs Citation2021).

3.3 Philippines: the Moro struggle

The Moro conflict in Mindanao, Southern Philippines, has its root in the colonial dynamics of the 16th century, resulting in one of the oldest conflicts, with political, ethnic, and religious implications (Schiavo-Campo and Judd Citation2005). A comprehensive description of the conflict evolution, from the early contact between the local communities and Arab missionaries and traders, the Spanish colonisation from 1565, the American occupation from 1898, until the independence in 1946, can be found in Buendia (Citation2006) and Montiel et al. (Citation2012), among others. Foundation of the conflict is the skewed and unequal control over land and natural resources, to the detriment of ethnic and religious minorities. Precisely, discriminatory land distribution policies, land grabbing and the resettlement programs of Christian settlers across the country against minorities (both the Muslim, referred to as the Moro,Footnote4 and the indigenous population), resulted in land distribution segregation mechanisms, the demolition of pre-colonial customary tenure patterns, and in the concentration of minorities in the southwestern region of the archipelago.

The conflict has taken over the centuries a violent and harsh development since 1968, with the creation of a political force, the Moro National Liberation Front, and of a more religious faction, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). Discontinuous negotiations were conducted from 1997 to 2014. However, the implementation of agreements has been everything but smooth, with mismatches in expectations, terms, and timing (Schiavo-Campo and Judd Citation2005; Buendia Citation2006; Joshi and Quinn Citation2017). The failure of the formal negotiations led to multiple relapses of violent confrontations, with damages to infrastructure and properties, displaced population, and a total death toll of 120.000 deaths (Herbolzheimer Citation2015b), more than 20.100 from 1989 to 2020 (Uppsala Conflict Data Program Citation2022). In 2014, the Philippines government and the MILF peace panel signed the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro, establishing the creation of a self-ruled autonomous region, building upon the 2012 Framework Agreement for Bangsamoro, and organised in two complementary tracks, one Political-Legislative and one focused on Normalisation (Andaya Citation2021).

The first track, as defined by Andaya (Citation2021), outlines the pathways towards the definition of an autonomous region, a crucial point conditional to the peace agreement, and able to pursue Islamic moral code in leadership, and the Bangsamoro right to self-determination (Herbolzheimer Citation2015b; Mindanao Peoples’ Caucus Citation2020a). The Normalisation track includes four points, the first being focused on Safety, including decommissioning, policing, dismantling of armed groups, and clearance; the second establishes socio-economic programs for decommissioned forces and their communities; the third involves different transitional justice and reconciliation measures; lastly, under confidence-building measures, amnesties and MILF camps transformations are enforced (Montalbo Citation2021; Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process Citation2021). Based on the work of Andaya (Citation2021), Montalbo (Citation2021), and the report from the World Bank Group (Citation2017), includes a summary of the tracks’ arrangements, based on the authors’ conceptual framework, and limited to those relevant to territorial peace.

Table 4. Land governance institutional arrangements Filipino peace process.

Looking at the Political-Legislative track, relevant to the achievement of Safety and Power Balance, the (1) Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM)Footnote5 is a parliamentary region with self-elected ministries, governed by Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA), with legislative powers initially until 2022, recently extended until 2025. As said by Abuza and Lischin (Citation2020), ‘it has established a creative power- and revenues-sharing system within a unitary state’ (p. 8). The Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL), signed in 2018 and ratified in 2019, constitutes a major contribution to the normalisation process (Mindanao Peoples’ Caucus Citation2020b; Andaya Citation2021). In 2020, the 1st Bangsamoro Development Plan 2020–2022, set the path for the coming years. The BARMM has exclusive power, among others, on resources management, land distribution, land survey, planning and development (Government of the Republic of the Philippines & Moro Islamic Liberation Front Citation2013). However, concurrent powers with the Filipino Government cover human rights, pollution, disaster risk reduction, justice, and, especially, land registration (Annex on Power Sharing Citation2014). In the latter matter, the BTA administers land registration, through the new (1a) National Cadastral Survey Program based on the central government’s system, and with the disclosure of land data by the Filipino government. However, the decentralisation of land administration, depending on BTA’s strength, face decades of displacements, competing land claims and clans’ feuds (International Crisis Group Citation2020). The BTA has also established the (1b) Office of Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Land Reform of the BARMM, which has tackled unequal land distribution and lack of tenure, assigning 1,200 hectares of land to farmer-recipients and Agrarian Reform Communities in BARMM region-wide before 2020 (Maulana Citation2020; Andaya Citation2021).

As part of the Normalisation track, several joint commissions dedicated to justice, security, infrastructure, energy, have been created, including the (2) Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC), addressing historical injustice, healing, and reconciliation, through land dispossession issues (World Bank Group Citation2017). The TJRC employed a Listening Process, reaching out to many conflict-involved groups; they identified the marginalisation of vulnerable groups through land dispossession as a root cause of the conflict (World Bank Group Citation2017). Other commissions supervise the processes of (3) policing, decommissioning, and landmines clearance, and (4) a Joint Normalisation Committee, through the coordination of other sub-committees, supports the ceasefire and the dispute resolution on the ground (Annex on Normalization Citation2014). Of particular interest are the (5) Confidence-Building Measures, involving the creation of a Taskforce for Decommissioned Combatants and their Communities, in charge of supporting the transformation of six MILF Camps into productive communities. Going ‘beyond the level of negotiation and related legal process’ (Andaya Citation2021, p. 145), confidence building is interpreted as a process that is economically, militarily and security-building relevant (Andaya Citation2021). Lastly, (6) socio-economic development programs are set up, providing ex-combatants, conflict-induced poor, and IDPs with housing, services, and cash. However, funds are diverted from this program to respond to the pandemic emergency and not all beneficiaries have been accommodated (interviews). As presented in the report by the BARMM Authorities et al. (Citation2021), of those IDPs who used to own their land, a quarter lacks proof of ownership; the majority wants to return to their place of origin to recover networks and livelihood, despite the lack of a framework to protect IDPs rights (World Bank Group Citation2017) and of information on government plans for displaced population (BARMM Authorities et al., Citation2021).

Despite the efforts, there are pre-conflict trends not yet addressed by the arrangements. Our interviewees claim that the indiscriminate implementation of land acquisition schemes of Bangsamoro land, implemented in favour of international companies and non-Moro owners, and happening in recent times after the agreement, forces Moro farmers looking for better economic opportunities to become tenants of their own land. Indigenous groups, as the Lumads, have been recognised as consultants in the FAB, but are far from being formally included in the negotiation process and seeing their ancestral rights recognised (Paredes Citation2015). Moreover, as stated by our interviewees, although peace has been supported by Filipino authorities, third sector actors, and civic society networks, the affinity to the MILF is contested by several community members, whose requests have been discarded in the negotiation process. The position of MILF remains contested, as MILF combatants, when joining the intra-community anti-terrorism taskforce, have reinforced a trend of violence and human rights violations against Bangsamoro communities (interviews). Community-based mediation, supported by local and well-respected NGOs, has been significant to tackle clan wars or family land disputes (interviews; World Bank Group Citation2017). Additionally, setbacks and offensives still affect the normalisation process and the combatants’ civil reintegration, although the first phase of demobilisation of the MILF combatants is completed and the MILF has established a political party in 2014 (Abuza and Lischin Citation2020).

4 Discussion

In the two selected case studies, land issues were at the core of the conflict and were brought forward in the peace negotiation, resulting in different institutional arrangements. In Colombia, the peace agreement offers comprehensive attention to HLP issues, from returnees, restitution, land reforms measures, secondary occupation, legislative reforms, and the identification of specialised bodies on HLP issues (Norwegian Refugee Council & Displacement Solutions Citation2018). On the contrary, in the Philippines, the establishment of a parliamentary autonomous region within the country has strongly addressed the request for self-determination of the Moro people. The peace agreement draws concerns for refugee and IDPs return, HLP restitution mechanisms, and HLP legislative reforms, including the protection of indigenous rights (Norwegian Refugee Council & Displacement Solutions Citation2018). Nevertheless, both peace agreements’ implementation is delayed by the permanence of violent groups that are fuelling violent confrontations in the territories, insufficient budget, and institutional support (Mindanao Peoples’ Caucus Citation2020b; Peace Accords Matrix, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies & Keough School of Global Affairs Citation2021).

In both cases, relevance is given to issues of Stability and Security through a revision and decentralisation of the cadastral systems, addressing land tenure issues as a baseline for further land distribution. Arrangements under Stability and Security are crucial to achieving land-based Sustainable Livelihood and Safety and Power Balance; specifically, the set-up of clear land administration and cadastral system clearly underline an equitable land redistribution policy, as well as a certain control of land markets, underpins the protection of land of vulnerable categories and limits speculation. However, the interference of powerful economic groups, such as large landowners that have seen their economic interest threatened by land redistribution and normalisation measures, opposes equitable redistribution principles, and remains a risk to Stability and Security.

In the Philippines, normalisation measures follow a transformative justice paradigm (Andaya Citation2021), through the establishment of a collective identity, upon the recognition and correction of historical alienation. However, as presented in our interviews, the constitution of an autonomous region clashes with the ongoing land grabbing and big-scale international acquisition processes. The BARMM, whose creation is far from being the end of a contested and fragile peace process (Trajano Citation2020), risks falling into the pre-conflict dynamics and losing the opportunity to benefit rural communities. In addition, the agreement between the MILF peace panel and the Filipino Government did not include indigenous populations and Muslim communities not affiliated with the MILF. This situation makes BARMM at risk of defeating its purpose of establishing equitable land distribution in the region. As for Colombia, important challenges in land restitution and redistribution have been faced in recent years, due to the huge scale of the land mechanisms required, the perpetuation of violence, the change of political direction of the government, and the low trust of communities (Robustelli Citation2018). Intertwined with land distribution measures, safety remains an issue in Colombia: social leaders are highly vulnerable: at least 971 social leaders were assassinated since the agreement’s signature in 2016, most of them due to land restitution or with coca crops substitution and in PDETs areas (Martínez Citation2020; Misión de Observación Electoral Citation2021; Murcia Citation2021).

Many arrangements are interconnected and fall into more than one category of our framework. Programs such as the PDETs and the MILF Camps Transformation aim to fulfil a triple function: the reintegration of ex-combatants, the generation of productive projects, and the creation of environments free of armed confrontation, addressing both Safety and Sustainable Livelihood. By doing so, land becomes a crucial ‘peacemaker’. Specifically, in Colombia, it serves as a transitional space to reintegrate ex-combatants, providing economic alternatives and educational processes to rebuild the social fabric. By combining the reinforcement of pre-conflict arrangements and new solutions, the Colombian agreement aims to recover land and communities in a joint pathway, contributing substantially to Sustainable Livelihood and Identity. In the Philippines, the demobilising of ex-combatants implies transformation in land use and agricultural practices, the provision of training, with the idea of building confidence and trust through territorial transformation. Moreover, formal land conflict resolution mechanisms are set up, although much is left in the hands of local NGOs and international bodies and informal conflict resolution.

Common barriers for reconciliation are the historical erosion of trust between groups, the historical economic inequality and the lack of resources and capacity of the new territorial regions, and, lastly, the low participation in law and decision-making of minorities, reinforcing a trend of social exclusion (Kapahi and Tañada Citation2018). Although it is rare to achieve a fully inclusive peace process, the low legitimacy and acceptance of different parties of the peace agreement during the peace process affects political and financial stability, social protection, security and progress in dialogue. In this regard, we would like to highlight the importance of community-based mediation in the Philippines and the work to include combatants and peasants in a livelihood transformative process in Colombia regardless of political extremes. A broad dialogue between conflict-affected groups may promote bottom-up peacebuilding initiatives and the consequent decentralisation and localisation of the peace process.

The framework shows how the three categories of territorial peace – Stability and Security, Livelihood and Identity, Safety and Power Balance- are incorporated in the agreements and the relevance of each arrangement in avoiding conflict relapse and address conflict root causes. These categories are complementary to each other; moreover, if one arrangement can fit into multiple categories, its implementation may follow a parallel path, as in the Filipino case, where the two tracks are connected but still, milestones can be achieved independently by the different set of actors involved (Montalbo Citation2021). Although the framework allows a comparative analysis over a concept so far focused on its geographical origin, it presents some limitations, regarding the merely qualitative approach, and the selection, assignation and comparison of such different and contextual arrangements, as the predominance of one arrangement’s purpose in one or the other category is not always univocal. In this regard, we provide some recommendations in the next section.

5 Conclusion and recommendations

This study draws light on the connection between land governance and its implication for peacebuilding through the concept of territorial peace. We aim to provide firstly, a framework to the concept, and secondly, to apply such a framework to the qualitative exploration of the two comprehensive peace agreements. This research contributes to the literature on peacebuilding and territorial peace, by identifying three types of institutional arrangements that should be part of peace agreements. Stability and Security arrangements set the ground for land administration, land availability, and accessibility; Livelihood and Identity principles are considered in the re-building of a cohesive and productive society; lastly, Safety and Power Balance refer to arrangements between all conflict-involved actors to the re-establishment of political life. The framework allows transferring the concept of territorial peace to a case different from the one at conception, even if not directly addressed. Interestingly, it highlights the benefits that certain arrangements can have on different aspects of territorial peace, feeding into multiple categories and therefore substancially contributing to it. Overall, the arrangements build upon land administration measures, often prioritised to set up a decentralised land administration system and up-to-date land-based information (Huggins Citation2009). Arrangements on alternative land use and land market aim to contrast pre-conflict sources of conflicts and inequality. In this sense, it is important that land markets reflect the same objective and ideology behind the peace agreement, avoiding turning into vehicles of the perpetuation of the pre-conflict status quo (Escallón Citation2021); if such structural changes do not take place, it is difficult for other arrangements to be equitable. In this sense, we can see that, even if Galtung’s (Citation1969) negative peace is not necessarily reached through the agreement, as conflict and violence perpetuate, these agreements address the cultural and structural conflict’s causes; even if the solution is distant, land-based peace arrangements become a powerful tool to start the peacebuilding process and address historical justice failure through a transformation of the territory.

Focusing on the framework, we would like to recommend a further operationalisation and testing of the concept of territorial peace, as its inclusion into the peace literature would enrich the role of land in conflict resolution and peacemaking. Efforts in the development of the concept should work on a clear set of indicators based on qualitative and quantitative analysis to improve replicability and validity, . These indicators should allow a multi-criteria analysis on the arrangements to strengthen their position in one category or another. In this light, research over the local dimension of territorial peace (i.e., Le Billon et al., Citation2020) and over the inclusion of both formal and informal mechanisms that differently address land inequality in the post-conflict phase, should complement studies at the institutional level. Moreover, the framework overlooks the process of peace negotiation, which can span from inclusive and democratic to highly restricted and elitist; we recommend expanding on the role of the peace negotiation process as a starting point on which to build territorial peace upon. Lastly, we recommend all aspects of territorial peace be considered in the negotiation phase and peace agreement, to strengthen the position of land in the peacebuilding process.

Abbreviations

Author contribution

Corresponding Author Francesca Vanelli (MSc Urban Management and Development, IHS, the Netherlands; MSc in Architecture, University of Ferrara, Italy) is a licensed architect, urban planner, and land specialist. Her thematic interests are land governance, land tenure and displacement, land and natural resources management, including waterfront cities and transboundary water bodies, social cohesion, reconstruction and community resilience initiatives against disasters, shocks, or conflicts.

Co-author Daniela Ochoa Peralta is a social researcher, consultant focused on governance, community resilience to climate change and volunteerism. She is a sociologist, with a master’s degree in Urban Management and Development from Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Geoffrey Payne, our interviewees and network for the invaluable support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo in Spanigh) were created in 1964; the suffix EP was added in 1982, accounting for Ejército del Pueblo (People’s Army).

2. Both land use and land cover are identified in cadasters; for the purpose of land governance, we look at the ‘functional land use’ (van der Molen Citation2002, p. 377).

3. The ‘Final Agreement for the End of the Conflict and the Construction of a Stable and Lasting Peace’ of 2016 is focused on six points: 1. A Comprehensive Rural Reform; 2. Political Participation: A democratic opportunity to build peace; 3. End of the Conflict and reincorporation of ex-combatants to civil life; 4. Drug trafficking, 5. Victims (Truth, Justice, Reparations and Non-Recurrence) and 6. Implementation, Verification and Endorsement of the agreement (Acuerdo Final Citation2016).

4. Moro is Spaniard term for Muslim Filipinos. ‘The term has been adopted by the local people and is not considered derogatory’ (Schiavo-Campo and Judd Citation2005, p. 1).

5. The BARMM takes the place of the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), obtaining more political and fiscal autonomy. The BTA is based in Cotabato City, whose administrative jurisdiction was voted during a plebiscite in 2019. To date, Cotabato City has yet to join the BARMM.

References

- Abuza Z, Lischin L. 2020. In: The challenges facing the Philippines‘ Bangsamoro autonomous region at one year; 468. Washington, DC: United States Institute of peace. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/20200610-sr_468-the_challenges_facing_the_philippines_bangsamoro_autonomous_region_at_one_year-sr.pdf

- Acuerdo Final. 2016. Acuerdo final para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera. Available at: https://www.jep.gov.co/Marco%20Normativo/Normativa_v2/01%20ACUERDOS/Texto-Nuevo-Acuerdo-Final.pdf?csf=1&e=0fpYA0

- Agencia para la Reincorporación y la Normalización. 2021. Informe de Seguimiento a La Implementación de Los PDET. https://centralpdet.renovacionterritorio.gov.co/documentos/tercer-informe-de-implementacion-vigencia-2020/.

- Agencia para la Reincorporación y la Normalización. n.d. Route of Reincorporation. https://www.reincorporacion.gov.co/es/reincorporacion/ruta-de-reincorporaci%C3%B3n

- Agencia Prensa Rural. 2017. ‘The PDET Must Start from the Recognition of the Peasant Reserve Zones Constituted and in the Process of Being Constituted’ Social Organizations. https://prensarural.org/spip/spip.php?article22082.

- Aguilar M, Sierra J, Ramirez W, Vargas O, Calle Z, Vargas W, Murcia C, Aronson J, Barrera Cataño JI. 2015. Toward a post-conflict Colombia: restoring to the future. Restoration Ecol. 23(1):4–6. doi:10.1111/rec.12172.

- Ahumada C. 2020. La implementación del Acuerdo de paz en Colombia: entre la “paz territorial” y la disputa por el territorio. Problemas del Desarrollo Revista Latinoamericana de Economía. 51(200):25–47.

- Alden Wily L. 2009. Tackling land tenure in the emergency to development transition in post-conflict states: from restitution to reform. In: Pantuliano S, editors. Practical Action Publishing. Uncharted Territory: Land, Conflict and Humanitarian Action: Bourton-on-Dunsmore, UK.

- Amnesty International. 2012. Colombia: the victims and land restitution law: an Amnesty Intenrational analysis. London, UK: Amnesty International Publications 2012; 24. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4f99029f2.pdf.

- Andaya R. 2021. Transformation through Normalization: delineating Justice in the Bangsamoro Peace Process. Hiroshima Peace Res J. 8:133–157.

- Annex on Normalization. 2014. http://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/PH_140125_AnnexNormalization.pdf.

- Annex on Power Sharing. 2014. https://ucdpged.uu.se/peaceagreements/fulltext/Phi%2020131208.pdf.

- Arias MA, Ibáñez AM, Zambrano, A. 2014. Agricultural Production Amid Conflict: The Effects of Shocks, Uncertainty, and Governance of Non-State Armed Actors Documentos CEDE 011005 (Universidad de los Andes - CEDE).

- Arnot CD, Luckert MK, Boxall PC. 2011. What Is Tenure Security? Conceptual Implications for Empirical Analysis. Land Econ. 87(2):297–311. doi:10.3368/le.87.2.297.

- Aron R. 1984. Paix et guerre entre les nations. Calmann-Levy.

- Arrubla KS. 2003. Economía y nación: una breve historia de Colombia. Bogotá: Norma.

- Augustinus C, Barry MB. 2006. Land management strategy formulation in post-conflict societies. Survey Rev. 38(302):668–681. doi:10.1179/sre.2006.38.302.668.

- Augustinus C, Ombretta Tempra O. 2021. ‘Fit-for-Purpose land administration in violent conflict settings. Land. 10(2):139. doi:10.3390/land10020139.

- Ball N. 2001. The challenge of rebuilding war-torn societies. In: Crocker CA, Hampson FO, Aall P editors. Turbolent peace: the challenge of managing international conflict. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace Press; 719–736.

- Bangsamoro Planning and Development Authority. 2020. https://bpda.bangsamoro.gov.ph/

- BARMM Authorities, UNHCR, & JIPS. 2021. Profiling of internal displacement in the island provinces of the bangsamoro autonomous region in muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

- Bautista S. 2017. Contribuciones a la fundamentación conceptual de paz territorial. Revista Ciudad Pazando. 10(1):100–110. doi:10.14483/2422278X.11639.

- Bell C. 2010. Contemporary peace agreements and accords. In: Young NJ, editor. The Oxford international encyclopaedia of peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195334685.001.0001/acref-9780195334685-e-142

- Berry RA. 2017. Reflections on injustice, inequality and land conflict in Colombia. Can J Latin Am Caribbean Studies/Revue Canadienne Des Études Latino-Américaines et Caraïbes. 42(3):277–297. doi:10.1080/08263663.2017.1378400.

- Borja M. 2017. Perspectivas territoriales del acuerdo de paz. Análisis Político. 30(90):61–76. doi:10.15446/anpol.v30n90.68556.

- Borras SM Jr., Franco JC. 2010. Contemporary discourses and contestations around pro-poor land policies and land governance. J Agrarian Change. 10(1):1–32. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2009.00243.x.

- Boutros-Ghali B. 1992. An agenda for peace. New York: United Nations.

- Buendia RG. 2006. The Mindanao conflict in the. Philippines: Ethno-Religious War or Economic Conflict?; p. 30.

- Cairo H, Oslender U, Piazzini C, Ríos J, Koopman S, Montoya V, Rodríguez F, Zambrano L. 2018. Territorial peace”: the emergence of a concept in Colombia’s peace negotiations. Geopolitics. 23(2):464–488. doi:10.1080/14650045.2018.1425110.

- Cepeda JA. 2016. El posacuerdo en Colombia y los nuevos retos de la seguridad. Cuadernos de estrategia América Latina: nuevos retos en seguridad y defensa. 181:195–224.

- Chetail V. ed. 2009. Post-conflict peacebuilding: a lexicon. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Congreso de Colombia. 2011. Ley 1448 de 2011. Por la cual se dictan medidas de atención, asistencia y reparación integral a las víctimas del conflicto armado interno y se dictan otras disposiciones. https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/sites/default/files/documentosbiblioteca/ley-1448-de-2011.pdf

- Congress of the Republic of Colombia. 2011. Law 1448 of 2011. Official Gazette 48096 of June 10, 2011.

- Daudelin J. 2003. Land and violence in post-conflict situations. Ottawa, Canada: The North-South Institute and The World Bank.

- Dayton B, Kriesberg L. 2009. Conflict transformation and peacebuilding: moving from violence to sustainable peace. London, UK: Routledge; 288.

- de Kraker J. 2017. Social learning for resilience in social–ecological systems. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 28:100–107. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.09.002.

- Enemark S, Clifford Bell K, Lemmen C, McLaren R. 2014. Fit-for-Purpose land administration. Copenhagen, Denmark: International Federation of Surveyors. FIG Publications.

- Escallón JMV. 2021. The historical relationship between agrarian reforms and internal armed conflicts: relevant factors for the Colombian post-conflict scenario. Land Use Policy. 101. 105138. accessed 2021 Feb 1. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105138

- Fajardo-Heyward P. 2018. Colombia 2017: entre La Implementación y La Incertidumbre. Revista de Ciencia Política (Santiago). 38(2):233–258. doi:10.4067/s0718-090x2018000200233.

- Fisher D. 2016. Freeze-framing territory: time and its significance in land governance. Space and Polity. 20(2):212–225. doi:10.1080/13562576.2016.1174557.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, & Agencia Nacional de Tierras. 2019. Las Zonas de Reserva Campesina Retos y Experiencias Significativas En Su Implementación.

- Forster R . 2019. Peace agreements. In: Romaniuk S, editor. The Palgrave encyclopedia of global security studies. Edinburgh, UK: Cham, Palgrave MacMillan; p. 1–7.

- Galtung J. 1969. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. J Peace Res. 6(3):167–191. doi:10.1177/002234336900600301.

- Galtung J. 1975. Three approaches to peace: peacekeeping, peacemaking and peacebuilding.In Galtung J, editor. Peace, War and Defense –Essays in Peace Research. Vol. 2. Copenhague: Christian Heljers; p. 282–304.

- Galtung J. 1996. Peace by peaceful means: peace and conflict, development, and civilization. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Galtung J 2003. Paz Por Medios Pacificos. Paz y Conflicto, Desarrollo y Civilizacion. Red Gernika 7, Bakeaz & Gernika Gogoratuz.

- Galtung J. 2009. Theories of conflict: definitions, dimensions, negations, and formations. Oslo: Transcend.

- Garcia Corrales LM, Avila H, Gutierrez RR. 2019. Land-Use and socioeconomic changes related to armed conflicts: a Colombian Regional Case Study. Environ Sci Policy. 97:116–124. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2019.04.012.

- García-Godos J, Wiig H. 2018. Ideals and realities of restitution: the Colombian land restitution programme. J Human Rights Practice. 10(1):40–57. doi:10.1093/jhuman/huy006.

- Garstka GJ. 2010. Post-conflict urban planning: the regularization process of an informal neighborhood in Kosova/o. Habitat Int. 34(1):86–95. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.07.004.

- Gleditsch NP. 1998. Armed Conflict and The Environment: A Critique of the Literature. J Peace Res. 35(3):381–400. doi:10.1177/0022343398035003007.

- Government of the Republic of the Philippines & Moro Islamic Liberation Front. 2013. Annex on Power Sharing on the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro.

- Guarnieri V. 2003. Food aid and livelihoods: Challenges and opportunities in complex emergencies. Food Security in Complex Emergencies: building policy frameworks to address longer-term programming challenges. 23-25 September, 2003. Tivoli, Italy FAO International Workshop. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- Guereña A. 2017. Radiografía De La Desigualdad: Lo Que Nos Dice El Último Censo Agropecuario Sobre La Distribución De La Tierra En Colombia. Bogota‘: Oxfam.

- Guzman LR, Holá B. 2019. Punishment in negotiated transitions: the Case of the Colombian Peace Agreement with the Farc-Ep. Int Crim Law Rev. 19(1):127–159. doi:10.1163/15718123-01901006.

- Herbolzheimer K. 2015a. Multiple paths to peace: public participation for transformative and sustainable peace processes. Kult-Ur. 2(3):139–156. doi:10.6035/Kult-ur.2015.2.3.7.

- Herbolzheimer K 2015b. The peace process in Mindanao, the Philippines: evolution and lessons learned. 8.

- Hollingsworth C. 2014. A framework for assessing security of tenure in post-conflict contexts. University of Twente.