ABSTRACT

India continues to urbanise rapidly tinged with sub-standard living conditions of a growing ‘slum’ population. Improving the living conditions of slum-dwellers remains a gargantuan and intractable challenge requiring solutions at scale grounded on households’ real experience of the process. The State of Odisha, in Eastern India, is currently implementing a state-wide land-titling initiative to improve the tenure security of a million slum-dwellers through legal, institutional, and technical innovations based on the Odisha Land Rights to Slum-dwellersAct 2017 (OLRSD). Given the known negative consequences of titling that grants ‘full property rights’, such as the speculative sale of the titles, the facilitation of elite capture,and disruption of community life and social networks, the OLRSD has fashioned the title as a ‘limited instrument’ that still assures the possibility to inherit and aims at facilitating mortgage for housing-backed lending. The paper discusses early learnings from Odisha’s ‘intermediate’ aspects of its titling policy in nine settlements researched across three districts. As per people’s accounts of their experienced reality, the titling, complemented by slum upgrading, has already facilitated improvements in the housing conditions of households subject to extreme poverty. However, concomitant challenges are surfacing for instance, although the OLRSD formally permits the titles to be used as collateral for housing loans, the non-acceptance of the title by mainstream banks forces the recipients to borrow from spurious private lenders, thus increasing their vulnerability. Understanding such and related challenges is relevant for better addressing the dimension of de jure land tenure security in slums at scale across India.

1. Introduction

It is estimated that rapid urbanisation in India may have forced 52–98 million people to live in urban slums (Census of India 2013; Millennium Development Goals database 2014); (Nolan et al., Citation2018). Since the onset of its globalisation in the 1990s, India has experienced unprecedented economic growth. But critics argue that the State veered towards a neoliberal framework (Kundu and Samanta Citation2011; Mahadevia et al., Citation2018) ‘surrendering its role of protecting working-class housing and employment to the interests of transnational capital’ (Chattaraj et al. Citation2017, p. 148). Indian urbanisation has been overridden by a development ideology that perceives of public investment on pro-poor housing as a counterproductive invitation for further migration from villages to cities (Burra Citation2005, p. 68). These migrants who become ‘slum’ dwellers are then perceived to lie in the way of the elite’s aspiration to develop ‘slum-free’ and ‘global and world class cities’ (Banerjee-Guha Citation2002; Dupont, 2011; Goldman, 2011; Roy, 2014 in Hagn Citation2016, pp. 1–2). Despite ‘slum’ dwellers being essential contributors to cities’ economic growth, they suffer deprivations indicative of market and policy failures.

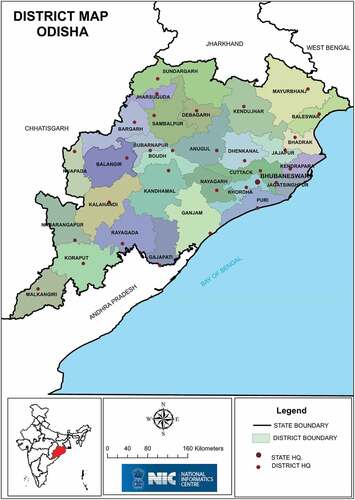

2. The case of Odisha State, India

In this milieu, the implementation of the Odisha Land Rights to Slum-dwellers Act 2017 (OLRSD) setting the basis for one of the world’s largest intermediate ‘titling’ initiative with an aspiration to provide land titles to a million residents deserves close analysis. Odisha is one of India’s poorest and most rapidly urbanising States. Due to its geographical location along the Bay of Bengal, it is also highly prone to natural disasters. Although Odisha has improved its disaster resilience capabilities, cyclones, flooding and droughts have taken a heavy toll on lives, livelihood and infrastructure thus undermining its development gains and exacerbating poverty and pre-existing vulnerabilities (ADB et al., Citation2019). Odisha’s ongoing secure tenure initiative offers unique insights due to its scale and audacity given the political opposition such initiatives encounter.

Odisha’s is an ‘intermediate’ tenure model () in that the title can be inherited and mortgaged for finance, but the title cannot be sold, thus providing a novel case study of limited property rights. Demographic analysis shows that much of India’s urbanisation over the last 20 years has been taking place outside mega-cities (Kundu Citation2011; Dijk Citation2014). Nevertheless, urbanisation and informal settlement studies in India have prioritised mega-cities and neglected smaller towns/cities (Datta Citation2006) and thus by using empirical insights from a less studied state (Veron, 2010 in Hagn Citation2016), this paper addresses this gap. The question guiding this study is: what can be learnt from Odisha’s ‘intermediate’ titling programme with regard to its impact over land tenure security and property rights in slums?

3. Aspects of tenure and rights

Land tenure is defined by Payne (Payne Citation2001) as the mode by which ‘land is held or owned, or the set of relationships among people concerning land or its product’. ‘Secure tenure, is thus the right of all individuals and groups to effective protection by the State against forced evictions’ (Payne et al., Citation2012, p. 8) or the ‘degree of risk of, or protection against, forcible eviction without due legal process and compensation’ (Nakamura Citation2017, p. 1716). Moreover, tenure system cannot be understood except in relationship to the socio-economic or political systems, which produce it (Bruce Citation1998, p. 1) and cannot be ensured in the absence of concomitant rights (Payne, Citation2012 in (Mahadevia Citation2010, p. 53).

Despite its critical significance, scholars and policymakers stress different elements of tenure security thus displaying wide disparity on what is deemed critical for realising it. Van Gelder’s (Citation2010) typology of tenure as de jure (legal), de facto and ‘perceived’, thus adds conceptual clarity and emphasises the lack of conclusive evidence on which type of tenure security is ideal (Patel Citation2016, p. 103).

The de jure tenure security favoured by property rights approaches ensures legal recognition of land rights through titling or registration. In essence, it assumes a dichotomy between formality and informality by equating property rights with tenure security and, conversely, the absence of such rights with insecurity (Van Gelder Citation2010, p. 451).

Alternatively, de facto tenure security is based on the facts on the ground and may be shaped by various non-legal factors, such as the length of occupation in the settlement, the cohesion of communities, political (and NGO) support, lack of evictions in the recent history and access to basic services amongst others (Durand-Lasserve et al. Citation2007; Gilbert, Citation2000; Payne Citation2001; Van Gelder Citation2010; (Nakamura Citation2016).

‘Perceived tenure security’ instead is generally conceived of as a household-level estimate of the probability of eviction (e.g., Bruce and Migot-Adholla, 1994; Gilbert, Citation2000; Razzaz, 1993; Varley, 1987; (van Gelder et al., 2015:487).

A property right is ‘a claim to a benefit (or income) stream that the state will agree to protect through the assignment of duty to others who may covet, or somehow interfere with, the benefit stream’ (Bromley, 1991: 2; (Sjaastad and Bromley Citation2000, p. 3). Tenure, therefore, relates to the means by which land is held and property rights to who can do what on a parcel of land. Some users may have access to the entire bundle of rights’ (with full use and transfer) and others limited usage (Fisher, 1995; (Payne et al. Citation2012, p. 8).

‘Land titling’ – ‘entails official registration and issuance of titles to individuals (or families) now holding (possessing) housing and other land-based assets in an allegedly tenuous and insecure state’ (Bromley Citation2008, p. 20). Titling calls for formalisation of the ‘extra-legal’ (de Soto, 2000) land tenure thus, integrating informal tenure into a formal (de jure) system recognised by the State (Nakamura Citation2014, p. 3422). However, ‘titling’ remains a ‘battleground of ideas’ (Varley Citation2017, p. 385). ‘Pro-titling’ advocates have long argued that registered freehold titles, fully marketable and mortgageable, enable residents to participate in the formal economy (de Soto, 1989; 2000; World Bank, 1993; Van Gelder et al., 2015:486) and reap its benefits including housing improvements and poverty reduction. These claims led to the implementation of mass titling programmes in the Global South for instance, Peru, Thailand, Egypt, Ghana and Indonesia (van Gelder Citation2013).

Moreover, most informal settlements have a ‘bewildering complexity of tenure systems’ (Payne Citation2004, p. 169) and tenure is often irregular and contested rather than strictly illegal (Jenkins, 2006; Dovey and King Citation2011, p. 12). Therefore, policy prescriptions prioritising a tenure regime, e.g. ‘individual freehold’ with its ideological slant towards private property and market forces, is questionable (UN Human Rights Council Citation2012, p. 8).

However, empirical evidence contradicts the claim of titling being a ‘silver bullet’ that positively transforms the lives of residents on its own (Boone, 2019; Buckley and Kalarickal, 2006; Payne et al. Citation2009; Kim et al. Citation2019). A large body of evidence disputes the argument that ‘without titling the native world lies beyond emancipation and is devoid of economy’ (Benjamin & Raman, 2011:46). There is growing acknowledgement that titling can be ineffective or even counter-productive (Shipton, 1988; Bruce and Migot-Adholla, 1994; Pinckney and Kimuyu, 1994; Platteau, 1996; Sjaastad and Cousins Citation2008). Titling, detractors claim, contributes to market-driven displacement of the original residents (Durand-Lasserve et al. Citation2007, p. 207; Smolka & de Larangeira, 2008; Varley Citation2017), loss of affordable housing stock, engenders speculative land transactions and creates land price distortions. Evidence to substantiate this is provided from Afghanistan (WB, 2006), India (Sukumaran, 1999; Banerjee, Citation2002), Egypt (Sims, 2002) and Cambodia and Rwanda (Durand-Lasserve et al. Citation2007) in (Payne et al. Citation2009). Studies point towards detrimental effects such as disruption of social fabric (Payne, 1997; (Bromley Citation2008), exclusion rather than inclusion (Fernandes, 2002, 11; Ramírez Corzo and Riofrio, 2005), aggravation of gender inequality (Varley Citation2007; Van Gelder Citation2010, p. 450) and cementing existing inequalities (Benjaminsen, 2002; Sjaastad and Cousins Citation2008).

Globally, in contrast to the titling (or property rights) approach, the supporters of ‘rights-based approach,’ or gradualists, propose incremental tenure security with emphasis on socio-economic incorporation of the settlements into the formal city (Payne Citation2001 in (Van Gelder Citation2010, p. 450). Furthermore, there is wide recognition that formal property rights underpinned by titling may be neither necessary nor sufficient to ensure security of rights (Deininger, 2003:39; EU, 2004; DfID, 2004 in (Mattingly Citation2013).

Figure 1. Residents of Harijan Sahi with their land rights certificates (LRCs), Gopalpur. Majority of the Harijan Sahi inhabitants had pucca houses prior to LRCs.

Based on the literature review, the following elements are prioritised to study the impact of titling on land tenure security and property rights with regard to:

legal protection against forced evictions

increased access to credit

increased access to basic services and infrastructure

Protection of vulnerable groups and

impact of property taxes and other fees

4. Methodology

This study is based on resident’s perception of their lived realities and the meanings they draw of the impact of this policy decision on it. Thus, the ontology chosen is constructivism and epistemology is interpretivism and constructionism. A case study approach was selected to gain insights into the implementation of the OLRSD 2017, a contemporary complex policy in its natural setting (Merriam, 2009; Simons, 2009; in Harrison et al. Citation2017, p. 8) to gather extensive evidence of a single example (Flyberrg, 2011:3).

As the OLRSD initiative is underway (2017 to 2023), there is therefore sparse literature available about it. Hence, the researcher collected primary data in December 2019 through field visit in Odisha. A follow-up visit planned in March 2020, which could have facilitated further clarifications, could not take place due to Covid-19 related travel restrictions. Guided by purposive sampling method slums in three diverse districts: Konark (Puri), Gopalpur (Ganjam) and Dhenkanal were selected to display multiple perspectives. Konark and Gopalpur are Notified Area Councils (NACs) i.e., smaller towns with populations up to 25,000. Both towns are on the coastline hosting fishermen communities. Dhenkanal on the other hand is a Municipal Council, i.e., a larger city with a population up to 300,000 with the slums comprising a diverse group of marginalised communities including Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). It is also a mountainous region with many slums situated on forestland. Due to paucity of time, no settlements were visited in the two municipalities of Berhampur and Bhubaneswar and data was collected in these bigger cities through semi-structured interviews with JAGA Fellows (JFs)Footnote1. JFs are TATA TrustsFootnote2 (TT) staff embedded in the municipal offices facilitating the JAGA mission (titling and upgrading).

Data collection was undertaken with the use of focus group discussions (FGDs) and semi-structured interviews in December 2019 and March and April 2020. In total, 127 respondents were interviewed: 99 slum-dwellers, 4 each of government officials (Executive Officers (labelled hereafter as EO) and Junior Engineer (JE), overseeing the implementation of the OLRSD) and land expertsFootnote3 and 20 JFs. The discussions were supplemented with official documentation and direct observations to triangulate the findings in an inductive approach that guided the analysis.

Details of slums visited included Konark NAC, Puri District

Nolia Sahi (S1) and

Mausima Sahi (S2)

Gopalpur NAC, Ganjam District

Sai Baba Sahi, (3) &

Sai Baba Sahi 7 (S4),

Harijan Sahi (S5) and

NAC Colony (S6) in and

Dhenkanal District

Hataroad Dama Sahi (S7),

Kathagada Juanga Sahi (S8) and

Kutunia Nua Sahi (S9)

Due to paucity of time, no slums were visited in Bhubaneshwar and Berhampur and data was collected through individual or group interviews with JFs in their offices. Similarly, information about OLRSD implementation was collected in discussions with JFs in Kalahandi and Nayagarh, which were not visited at all.

Figure enumerating the total number of respondents interviewed

4.1. Limitations of the methods

Although the titling program is applicable in all 30 districts of Odisha, due to time and resource constraints, only 3 districts and 2 cities were visited. Data on tenure security was collected from the residents through FGDs at the settlement level with no data collected at household level, which can be heterogeneous. The study did not review if titling was violating ‘urban planning legislation in terms of land use zoning, subdivision and building regulations and standards’ (Banerjee, Citation2002:7) and land tenability challenges for the entirety of slums surveyed. Data on access to services was not collected regarding adequacy and affordability and if private actors or NGOs were filling the gap left by the Government. Instead, the services data was triangulated from discussions with residents and JFs. The titling initiative is underway (2017–2023) with the GoO revising the implementation strategy as it progresses. Some of these issues may bias the analysis and render specific data and analysis redundant.

5. Case study: the Odisha Land Rights to Slum-dwellers Act 2017 (OLRSD) under implementation

Odisha (called Orissa until 2011) ( & ) has a population of 42 million and consists of 30 districts and 114 Urban local bodies (ULBs) with 5 Corporations, 35 Municipal Councils and 63 NACs (Census, 2011). Besides being one of the poorest states in the country, it’s record on human development is also amongst the lowest (Mohanty et al. Citation2016). Although a predominantly agricultural and rural State, Odisha is urbanising rapidly. In comparison to the relatively richer states whose urbanisation level stands at above 40% (Tumbe Citation2016), Odisha’s urbanisation rate is 16% (Census, 2011). The percentage of slum households in proportion to total urban population is 23% (Census, 2011).

Historically, the State of Orissa was formed with the amalgamation of 24 native principalities and areas governed by different revenue systems and tenancy laws which were merged to carve out new districts (Sinha Citation2014). Post-independence, Odisha made changes in its policy framework with a ‘focus on equity, ecology, participatory democracy, economic development and information technology’ (LGAF Citation2014, p. 1). GoO also recognised the importance of land in addressing poverty and have enacted many land reform legislations (UNDP Citation2008). Nonetheless, due to weak revenue administration and lack of updated land records, these laws have had a limited impact (Mearns and Sinha Citation1999) and thus, landlessness, concealed tenancy and poor protection of tribal land rights still abounds (LGAF Citation2014, p. 3).

The government is the absolute owner of all the land in the StateFootnote4 with those enjoying rights to use a parcel of the land called as occupants instead of an owner. These rights to use land can be ‘freehold’ or ‘restricted’. Similar to the rest of India, Odisha has two systems of land record keeping: a ‘deed registration system’, and ‘land revenue system’ or Record of Rights (RoR) colloquially referred to as PattaFootnote5 (Das & Mukherjee, 2018). Land records are, however, maintained across dispersed networks of government offices, thus leading to discrepancies, duplication and uncertainty of data accuracy. Additionally, like the rest of India, its urbanisation processes are suffering due to the ‘absence of proper land records, digitalised records, map and the high transaction costs and the multitude of layers of land administrative system’ (Morris and Pandey 2009; Deininger et al. 2016; Roy, 2017:100)

Property tax is a major source of revenue for the ULBs in Odisha. However, due to a lesser determination and coverage of these taxes, the GoO is losing large amounts of revenue and is currently reviewing its property law regime (LGAF Citation2014). Over the years, Odisha has implemented various GoI led poverty alleviation, affordable housing and slum-free cities programmes such as JNNURM, 2005 and Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY), 2011. The performance of JNNURM was qualified as unimpressive (Hagn Citation2016, p. 6). GoO also launched the Slum Rehabilitation & Development Policy (SRDP), 2011 to have a ‘slum-free Odisha by 2020’, which aims to provide individual land tenure incrementally, improving from restricted (occupancy and short-term lease) to full title with property rights over time and minimising relocations (LGAF Citation2014). In 2015, it also launched Odisha Urban Housing mission, AWAAS, which aims to cater to both rental and permanent housing needs of migrants, homeless and other poor populations.

One of the common challenges in implementing these housing programmes was landlessness or lack of land documentation analogous to other states. Although landlessness is a major problem for the urban poor, studies also demonstrate existence of various tenurial arrangements in slums. In Bhubaneswar, authorised slums included villages that were incorporated into urban limits over the years to government-built resettlement sites under recent schemes and unauthorised’ slums, with no tenurial rights (Anand et al., 2017:21). Similarly, in Berhampur and Puri, many residents were not landless, but lacked documents establishing property transfer and/or cadastral registration (Das et al., 2018). So far in the smaller cities, the shortage of affordable land, increasing poverty and population densities, has not devastated the poor people and their ability to house themselves.

5.1. Details of the OLRSD, 2017

The OLRSD entitles every landless person who is occupying land in a slumFootnote6 in NACs and municipalities and as on 10 August 2017, to a land rights certificate (LRC). The Act covers the entire State of Odisha but is not applicable to Municipal Corporations (Bhubaneshwar, Cuttack, Sambalpur, Rourkela and Berhampur). The LRC is issued jointly in the name of both the spouses or a single person if single-headed household. The LRC is not a freehold individual title. It is heritable but not transferable (by sub-lease, sale, gift, or any other manner) and may be mortgaged for accessing a housing loan. For those who belong to the Economically Weaker Section (EWS), i.e., whose annual household income is below 180,000Footnote7 Indian rupees, free land up to 30 square metres (sq. m) or 323 square feet (sq. ft) will be provided. Furthermore, the land allocation varies in NACs and municipalities. The maximum land given in a municipality is 45 sq.m or 484 sq.ft and 60 sq.m or 646 sq.ft in NACs. The cost beyond the free land is the benchmark value (or premium) to be paid by the slum-dwellers and is lower for EWS families. The land titling program was complemented with slum upgradingFootnote8 called JAGA or Odisha Liveable Habitat Mission (OLHM)Footnote9 and the provision of roads, drainage, sewage systems, toilets, streetlights, piped water and playgrounds. The Housing & Urban Development Department (HUDD) along with TATA Trusts coordinates this initiative. Organisations such as Norman Foster Foundation, Omidyar Network, Cadasta and Spatial Planning & Analysis Research CentreFootnote10 (SPARC) Bhubaneswar have also provided support. Given the high-density and compact nature of the settlements, JAGA used Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) or drones to undertake large-scale slum mapping, which facilitated high-resolution imagery of external boundaries, detailed mapping of the plots (Pichel et al. Citation2019) and led to cost reduction. Subsequent to the drone survey, a door-to-door household survey called Urban Slum Household Area survey (USHA), captured demographic, socio-economic profile, plot area and infrastructure of the dwelling unit (Bridgespan Group, 2017). Slum-dwellers Associations (SDA) are mobilised in each settlement to articulate the needs of the residents. Please explain what these maps show and why they are relevant.

6. Findings and analysis

This section discusses the empirical findings from the field visit in the nine settlements in the three districts visited, the two Municipal Corporations, and the districts of Kalahandi and Nayagarh, which were not visited.

6.1. OLRSD and legal protection from forced evictions

Forced evictions have been uncommon in the settlements visited. No resident feared getting evicted after receiving the LRCs. Only three eviction and relocation cases were cited despite some residents having lived there for more than three or even, eight decades.

The first case was Gopalpur in 2015 where the two slums (labelled S3 & S4 hereinafter) were served relocation orders to move to Narayanpur, 2 km away. As most inhabitants are fishermen, they opposed to moving far from the sea. The local politician had intervened on their behalf thanks to which the order was rescinded (residents of S4). The second instance was Kalahandi in 2016, where residents of Irrigation Colony, a settlement on private land, were relocated to State Government land (Telugubangati Pada), approximately 3 km from the city. The residents had acquiesced as the new site was spacious and they received some basic services (JF_10). The final example was settlement S9 in Dhenkanal, which was served an eviction notice in 2002 but the demolition order was revoked after the intervention of the local politician (residents of S9).

The low rate of evictions was attributed to their locations in relatively less urbanised towns and on low-value land. Furthermore, settlements in Gopalpur and Konark are situated in the coastal region and face the annual wrath of cyclones. The residents of kutchaFootnote11 (provisional) houses suffer heavy damages, including loss of lives and properties (residents of S1, 3 and 4). Another reason cited was residents’ linkages with bureaucrats and politicians. Land allocation and eviction are politically contentious issues and mired in corruption in Odisha. The opposition parties had in general critiqued OLRSD as a ploy of the Biju Janata Dal (BJD), the State ruling party, to garner votes and were also allegedly delaying the implementation of OLRSD by spreading misinformation and obstructing the titling processes (EO_1 and JF_1 & 6).

Moreover, most of the residents did not want to sell or speculate on the land; instead, they wanted to own a pucca (durable house usually built of cement and bricks) house to bequeath it to their children. In Konark and Gopalpur, the residents stressed the importance of LRCs and de jure tenure security, which enabled them to construct ‘pucca’ houses, thus ensuring personal safety and financial savings, which they would otherwise spend annually on repair and reconstruction of houses destroyed by cyclones (residents of S3 & S4). In Nayagarh, many residents wanted to build extra rooms to supplement their income by operating grocery or mobile repair stores (JF_9). The below is the table which demonstrates the property rights of the residents post OLRSD.

6.2. Enhanced access to credit/mortgage

Despite receiving the LRCs, the residents were not served by formal banks. However, on receipt of LRCs, the residents are eligible to receive the housing grant from Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY)Footnote12 housing subsidy scheme and similarly, GoO’s AWAAS Scheme and additional grant from Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) for toilet construction. As the housing subsidy was disbursed to LRC recipients in tranches, the slum-dwellers had to initially invest their own funds to construct the houses up to the plinth level. With no savings, some residents were compelled to borrow from private lenders at exorbitant interest rates (S3, S4 and JF_10). Others were borrowing from family-members, employers, or self-help groups (SHGs) due to the latter’s easy availability without stringent documentation and reasonable interest rates (S2). Besides loans for house constructions, money was also needed to pay for the land premiums (beyond the free land of 30sq m). With no prospects of loans from banks, the poorer households were either taking loans from family and friends or private lenders or seeking time to save funds and the latter was also further delaying the titling process (JF_6 & 9).

The employment profile of the residents showed a high rate of informality. There were a few slum-dwellers who worked as low-level government officials (residents of S2, S5 & S6). Apart from these salaried officials, none of the other slum-dwellers had regular income or access to social security benefits. JAGA mission was soliciting the headquarters of government banks for loans to the LRC recipients; however, no bank had shown any interest (JF_7 & TT 1).

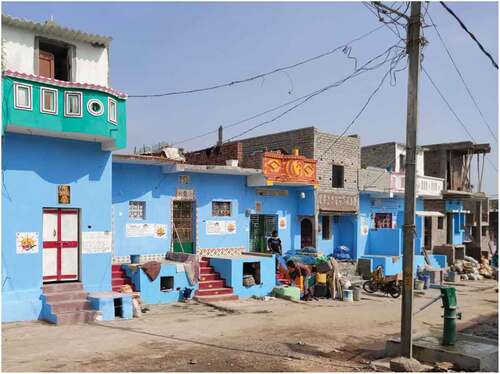

6.3. Access to basic services and infrastructure

Along with titling, the upgrading was aimed to transform slums into liveable habitats. The residents enjoyed some services prior to the OLRSD, but with the upgrading there was an increase in quality and quantity of services. Nevertheless, this access varied. For instance, in Konark (S1) and Dhenkanal (S7) due to space constraints, toilet facilities were planned on a communal basis while in Gopalpur (S3 and S4) the residents were constructing toilets in their houses with the use of SBM subsidies. In Konark (S1) as the Norman Foster Foundation had taken over the upgrading work, an extensive plan was being developed to refashion it into a ‘model settlement’ (TT_1). In contrast, in Kalahandi, apart from land titles and housing subsidies no upgrading was planned (JF_10). In Konark (S2) and Gopalpur (S5 & 6), most residents had constructed pucca houses and had access to basic services years earlier due to their bureaucratic and political networks (JF_1 & EO_2).

In Gopalpur, the increased services had presented some unforeseen pitfalls. After constructing ‘pucca’ houses, the residents complained of a threefold increase in their electricity bills and destruction of the road and drainage. Furthermore, with separate taps for each house, there was a lot of wastage of water leading to conflicts (S3 & 4). In some settlements, the service provision was delayed due to lack of residents’ cooperation. In Konark, drainage and road construction was stalled, as the residents did not want to demolish and construct their houses to facilitate the upgrading plan. Instead, they were demanding the upgrading plans to be altered to circumvent their house (JF_1). Another challenge was encroachment of common land allotted for utilities by the residents. When officials visited the settlement to measure and demarcate land for drainages or roads, they found the land occupied, which forced them to locate in alternative sites and redraw the plans (JF_1 & 6).

In general, the poorer residents were pleased with the enhancement of amenities as it made them feel equal to ‘other city-dwellers’ and that the GoO had finally ‘recognised their existence’. ( & ). Notwithstanding, these improvements of basic services, for the majority of poorer residents, the LRCs and de jure tenure security were of far greater significance (S1, 3, 4, 8 & 9).

6.4. Protection of vulnerable groups

Joint title and women

The women appreciated the joint titles as it gave them many benefits:

Protection from dispossession by husband’s family after his death (S1),

Prevention of speculative sale by men as any sale of the land had to be agreed by the wife as joint title holder (S1 & 4),

Stem domestic violence and abuse in a patriarchal society-like Odisha (LE_SC),

Provision of a safe space if the husband divorces or abandons his wife (EO_1 & JF_6).

One of the challenges of joint title though is that in some settlements due to flexible social mores, couples are known to take different partners. As the LRC is tied to a husband and wife, this could pose difficulty for such couples (LE_PC).

Dwelling owner and tenants

Tenancy was not prevalent in the slums in Gopalpur and Dhenkanal while admitted in Konark, Kalahandi and Nayagarh.

Why will people go for tenancy when there is so much empty land? You can clear the jungle and make a small kutcha house and gradually make it a pucca one. JF_6

There was discrepancy regarding issuance of LRCs to the tenants. In Nayagarh, during the sensitisation process prior to the surveys, owner-occupants/landlords were informed that tenants would be issued LRCs. The landlords, despite their misgivings had relented and the tenants received the LRCs (JF_11). Contrarily, in Kalahandi, the landlords; objected and claimed that since the tenants had not invested funds for house construction, they should be ineligible. Due to eviction threats from the landlords, the tenants had not applied for LRCs (JF_10).

6.5. Payment of property tax and other fees

All residents were aware of property tax (called holding tax) and some residents were already paying this. Since it is a nominal amount, they had no hesitation to pay (in all settlements). Besides, residents are paying a one-off premium for land beyond that assigned under the OLRSD. Despite the financial hardship, EWS households (poorer residents) were incurring loans to pay the premiums since they were keen to receive the LRCs (S1, S8, S9 and JF_10).

In contrast, non-EWS households were not keen to pay higher premiums as these were assessed at market rates. In Gopalpur, residents were reluctant to return the extra land occupied by them or demolish part of their pucca houses. If they were forced to pay, they were negotiating to pay the subsidised premiums that were levied on the EWS households (of S3 and S4) and not the higher rates (S5). Similarly, in Kalahandi, powerful slumlords had occupied large parcels of land, built many houses and rented them out and eschewed the idea of returning the extra land. These slumlords were lobbying with politicians to either waive off the premiums entirely or regularise their large houses, kitchen gardens, trees and land. This reality was summed up as follows by. ‘This project is good for very poor people. The non-EWS and relatively better off people are not even applying for LRCs’JF_10.

Figure 4. Beneficiaries with the LRCs in front of their house being built with PMAY subsidy, after receipt of LRCs, Kalahandi.

(Jagriti Singh/JF, 2019)

6.6. Challenges in the OLRSD implementation

OLRSD is applicable only in smaller towns and cities; nevertheless, the residents in Municipal Corporations will benefit from in situ upgrading in three phases and receive various basic amenities (JF_4).

As OLRSD is a law, the slum-dwellers had reassurance that it will not be repealed with change in political leadership and they were positive about the LRC as it meant ‘respect in society’, ‘better services’, ‘pucca houses’ and ‘an end to being treated like animals’ (S1, S3, S4 & S8). However, the 323 sq ft. of the plot allotted was a concern. With most slum-dwellers having large families, there was fear that it may contribute to intra-household conflicts especially inheritance cases (residents of S9). OLRSD was GoO’s response to address the twin challenges of urban poverty and rapid and haphazard urbanisation. However, it presents substantive and jurisdictional challenges (LE_KK). The GoO had bypassed the revenue department, the owner of State land, and assigned the OLRSD to the urban department. Legally, revenue department is the sole authority to expropriate land, register land transactions and issue titles and deeds. It was feared that revenue department’s disengagement would lead to confusion in land classification; discontinuation of updating of land records (LE_SP) and undermine the sustainability of this initiative (LE_PC).

Senior officials who know about these legal dilemmas are not happy to sign on the dotted line

LE_PC

The OLRSD is a ‘wafer thin policy and lacks a detailed implementation strategy and is more of work your way through issues as you go’ (LE_PC). Allegations of fraudulent claims and cases of vulnerable people being missed out of the beneficiary lists had surfaced in the local media leading to questions being raised about the due diligence process of OLRSD. Additional challenge with OLRSD’s implementation was highlighted by (LE_SC): ‘Land records in Odisha are a mess. Sometimes land is sold and when you dig further, the same land has been sold to someone else or there are issues of tenability’.

The OLRSD prioritises in situ development. However, not all slums were on tenableFootnote13 land; many slums are on private land, temple trust land or railway or forest land. For the households on untenable land, the option provided was relocation, which was turning out to be highly contentious with residents actively opposing any move from their current settlements (JF_10 & 11). Challenges with land tenure and irregularities about land usage were also stalling the process. For instance, in Gopalpur, out of the five slums, one slum was on private and legally contested land. The residents were demanding LRCs but as the land was sub judice, the settlement was not prioritised for titling (EO_2). In Konark, there are 12 slums in total; however, residents of nine ‘slums’ who have ‘pattas’ for their land have refused to participate in the titling programme, as they did not want to be derogatorily called ‘slum-dwellers.’ They had lived in their villages for generations and did not perceive any benefits of titling (JF_1).

Restricted and intermediate title was not appealing to many residents. In Gopalpur, the residents preferred the option to sell their house if facing financial drawbacks and relocate to another slum (S5 and S6). As land speculation is common, the GoO has taken stringent measures including issuing restricted and joint titles (EO_1 & 2).

Slum land was being encroached and grabbed after the surveys contributing to conflicts. In Konark (S2), non-slum people from neighbouring cities had grabbed slum land, built houses and rented them out. The SDA members had opposed these encroachments and complained to the authorities but in vain (JF_1). In Dhenkanal (S8), similarly, non-slum people had encroached on slum land and commenced house construction, which was prevented by the SDA. Contrarily, in S9 in Dhenkanal, some of the SDA members had allegedly sold slum land to non-slum households, who were producing documents to authorities claiming to have resided in the settlement prior to the drone surveys and demanding LRCs (JF_6).

The OLRSD was also delayed due to other unforeseen causes. In Konark (S1) and Kalahandi the drone survey captured only the contours of the houses. In many instances, the residents undertake a lot of their household chores outside the houses, like cooking, sleeping or bathing small children. The dimensions captured by the drones were below the 230 to 484 sq.ft., which made the household ineligible for the PMAY subsidies. HUDD had to intervene to allocate larger parcels of land to these households to ensure eligibility for the housing subsidy (JF_1 &10).

Another additional challenge was fraudulent claims made by the residents. In Dhenkanal, some beneficiaries had ownership documentation for non-slum land and had constructed pucca houses with PMAY subsidy some years ago. However, they had also occupied slum land and were claiming titles and housing subsidies. Since the municipal authorities did not maintain accurate records of PMAY beneficiaries, they had to now undertake rigorous and detailed checks to prevent these beneficiaries ‘gaming the system’. One of the benefits of OLRSD for the municipal authorities with the use of drones and household surveys was accurate geotagged boundary and household information, thus minimising fraudulent claims (JF_5).

7. Discussion

The sections below interpret the empirical findings in light of understanding the tenure security envisaged by OLRSD and the concomitant improvement of living and housing conditions of the slum-dwellers.

7.1. Legal protection from forced evictions: one promise too many

The slum-dwellers covered by the study enjoyed a combination of perceived and de facto tenure security prior to the titling initiative due to a variety of factors demonstrated by the limited number of eviction and relocation notices. The intermediate title and the package of benefits of housing subsidy and upgrading nonetheless provided the EWS households multiple additional benefits: de jure tenure security, a more durable house, increased access to basic services, and, in some instances, protection from natural disasters. Contrarily, for the non-EWS residents, OLRSD and legal tenure security provided no great advantage as they had pucca houses and access to services prior to the titling programme and with the titling had to forego their parts of houses and gardens that exceeded the size stipulated for regularisation. OLRSD’s provisions are restrictive for this group in actually preventing them from consolidating their gains.

Empirical studies attest to an increase in perception of de facto security mobilising residents to housing investments, thus questioning the necessity of regularisation. However, in Odisha, perceived tenure security had resulted in improved housing for the non-EWS residents with political and bureaucratic linkages while the majority of the poorer residents continued to live in kutchaFootnote14 houses prior to the OLRSD. The poorer residents however, were ‘moving up’ the tenure continuum with access to some basic services, voters ID and ration cardsFootnote15 and payment of property taxes. This ‘moving up’ in the tenure continuum, for the residents, however, even after many decades, had not led to any remarkable changes in the living standards of these poorer residents. These variations thus beg the questions about whose perspective is important for tenure security and what should guide tenure security policy interventions.

The rapid commercialisation of land in bigger cities in Odisha has contributed to the spiralling land prices and greater competition over urban land; however, this trend has not yet emerged in the smaller cities and towns. The response of the different sections (EWS and middle class) of the slum-dwellers to OLRSD also further substantiates the heterogeneity and social stratification within slums and demonstrates that not all slum-dwellers are poor. There are great variations amongst slum-dwellers with regard to their livelihood, migration, education or tenure profiles amongst others. OLRSD reveals how local context is significant for tenure security – and that even within part of an urban continuum, there are variations. This highlights a need for a more nuanced understanding of the varying needs of slum-dwellers and for adjusting tenure policies accordingly. Furthermore, while cases of forced evictions after titling are found in India, such cases had not surfaced yet in the settlements researched.

The political issues highlighted in the settlements demonstrate the fraught nature of titling amongst the multiplicity of stakeholders involved. It was widely recognised that the BJD Government had succeeded in implementing the OLRSD due to its political stronghold confirming its ability to control land, planning and informality. BJD Government had succeeded in promulgating these tenure policies and a solution at scale due to its electoral prowess. For the residents, ‘patron-clientelism’ and ‘vote bank politics’ has leveraged tenure security and enhanced access to services.

7.2. De Soto’s claim of unlocking of ‘dead capital’ and the increased vulnerability for accessing credit for slum-dwellers

Similar to global empirical evidence, in peri-urban Odisha challenges to access to credit included not only the lack of formal land title for property to qualify as collateral but also the low value of slum lands – even informal ones. Residents also showed an aversion to pawning their few significant assets, particularly those they regarded as those of a family, rather than an individual. The LRCs, however, granted some more confidence for borrowing from SHGs and private lenders. SHGs and some lenders such as relatives can be qualified as ‘benevolent’ in so far as they grant low interest rates and help residents invest. But other private lenders applied exploitative rates exposing borrowers to rapidly increasing debt, thus, generating further uncertainties and vulnerabilities. Despite the LRCs, the poor gained no access to formal bank loans because as a ‘limited title’, banks could not use them for foreclosure. Also, allowing for foreclosure means making the poor, generally indebted and with limited financial literacy, more vulnerable to losing the stability houses provide them. For the banks, casual and informal employment without the necessary proof of stable income, kept residents as a high-risk category for lending to. In Odisha, the claims made by DeSoto of titling unlocking the dead capital of the poor has thus proven wrong. The case study thus adds to the growing evidence of titling contributing to increased potential vulnerability through over-indebtedness when accessing collateralised credit. It is critical to bear in mind that one of the presumptions of the titling programme was that LRCs would seamlessly engender access to credit from mainstream banks. The failure of this assumption demonstrates the need to create a new relationship between the GoO, banks and the poor in order to responsibly facilitate loans based on the vulnerable people’s capacity to repay without endangering their property.

7.3. Belonging to the city: secure tenure and access to basic services

Previous studies have highlighted a causal relationship between lack of tenure security and access to basic services. (Durand-Lasserve et al. Citation2007; (Kranthi and Rao Citation2010) (Murthy Citation2012); Subbaraman et al. 2012 in (Nolan et al. Citation2018). By ensuring de jure tenure security along with upgrading, OLRSD has led to enhanced quantity and quality of amenities for residents of some settlements. Studies prove that living in slums involves deprivations that cause hardship and ill-health and has negative consequences especially for women. Better amenities increase human capabilities and welfare outcomes. The OLRSD, by also providing increased quality of services, has at least partially addressed these concerns. Thus, in districts where only LRCs and housing subsidies are provided in the first stage, it would be crucial for the State to also facilitate access to basic services and upgrading in order to fashion the LRCs as a meaningful welfare and poverty reduction policy. Additionally, given Odisha’s limited progress in improving human development, access to basic services and infrastructure should be provided to the urban poor as part of its social contract and not be made a condition sine qua non for accessing a titling programme. A land title plays a key role in the poor residents’ lives. However, for the residents, ownership of the plot and house (with subsidy) is not equated highly in comparison to formal titles, with access to basic services and livelihood opportunities.

7.4. Protection of vulnerable persons

Women and joint titles

‘Gender is a key issue in tenure policy’ (Payne Citation2004, p. 170; UNFPA, 2007:19 in Chant Citation2013, p. 17) and the majority of the women consulted were of the opinion that joint title was beneficial to them. However, besides a cursory discussion on the advantages of joint titling, the research did not delve deeper into its impact, namely, shift in household decision-making, reduction in domestic violence and fertility and other welfare outcomes as highlighted (Datta Citation2006, p. 273; Varley Citation2007, p. 1747). Joint titling was GoO’s institutional policy and not a result of advocacy by donors or NGOs (Nielsen et al., 2006; Collin Citation2013, p. 8).

Dwelling owners and tenants

The lack of clarity about tenants and their right to LRCs led to an interpretation in some quarters that OLRSD only applied to ‘dwelling owners’. In Odisha, comparable to the rest of India, where around one-third (Census, 2011) of the urban poor resort to rental arrangements (Jain et al. Citation2016, p. 7), ‘tenants’ form a significant share of the urban poor (Das & Mukherjee, 2018:x). Previous studies have referenced titling leading to increases in rental charges and eviction of tenants (Durand-Lasserve et al., 2007:23; Payne, 1997:46), but this was not highlighted in the field visit. However, it was clear that tenants in some settlements were threatened by the landlords and could not participate in titling, similar to the studies of Rakodi (Citation2014:29; UN-Habitat, 2011b:5 in Mattingly Citation2013, p. 14). This lack of clarity had played into power imbalances between landlords and tenants (Kemeny, 2001; Hulse et al., 2011 in (Prindex Citation2019, p. 12) with tenants in some settlements missing out on the benefits of titling.

7.5. Titling and taxation: the tokenistic property tax and the burden of land premiums

Empirical studies attest to cases where taxes and administration charges hinder land-titling and the slum-dwellers have no resources to keep up their payments, thus abandoning titling programmes. In Odisha, property taxes are nominal and a token payment did not add to the financial burden for the residents. However, the premiums for the extra land appear to be a burden especially for the poorer residents despite the EWS category subsidies. The premiums were causing financial hardship to the poorer residents and increasing their debt burden however, as the slum-dwellers value the LRCs, they are going ahead with these payments. This beneficiary contribution to the programme was an added revenue source for the government to fund amenities and upgrading interventions and contributing to some extent to the sustainability of the programme.

7.6. Challenges of OLRSD implementation

OLRSD has brought to the fore the critical issue that issuance of land titles to the poor cannot be a panacea for addressing the challenges of informal settlements at scale if it does not tackle the fundamental problems, which contributed to informality in the first instance. Merely focusing on the luxury of an assured freehold title (or de jure) tenure security in policy discussions may be missing critical dimensions of tenure security for the residents such as the availability of basic services, a durable house, proximity to livelihoods sources, social recognition and legitimacy by the state.

GoO has taken ample measures to prevent speculative sale of LRCs by the residents for a profit and returning as squatters elsewhere.Footnote16 However, as the LRCs are still being issued, cases of sale of titles in the ‘grey’ market and other challenges, including intra-household conflicts, contestations between slum and non-slum households about land grabbing and delays due to relocationFootnote17 of untenable slums amongst others are surfacing. These myriad challenges again emphasise the critical role of due diligence. Any rushing of titling processes without greater understanding and emphasis on the local context, stakeholders and dynamics pave the way to uncertainties, insecurities and conflicts.

GoO has over the years implemented intermediate tenure policies like the SRDP, 2011 and supplemented GoI’s housing programme of PMAY and its own urban housing mission of AWAAS. OLRSD could therefore in essence be considered a step further within this policy arena, thus, clearing the way for increased uptake of the beneficiary-led construction of the housing subsidy, which was otherwise hindered through lack of land ownership documentation. However, given the various challenges related to freehold titles (e.g., gentrification, speculative sale or breakdown of the social fabric), it is still questionable as to why the GoO has not prioritised other intermediate and strategic tenure options; like for instance, ‘occupancy permits’, ‘directive for non-eviction’ or the provision of basic services and infrastructure. Without a detailed policy paper clarifying the purpose and logic behind this policy, one can only surmise the reasons behind why the GoO prioritised these joint property titles and de jure tenure security policy option.

8. Conclusions

The paper set out to learn about the ‘intermediate’ aspects of Odisha’s titling programme with respect to its early impact on land tenure security and property rights in slums. Although its incidence has varied across types of households and settlements, in general, it has improved de jure tenure security especially of EWS households. Without legal tenure security, according to residents’ accounts, the basic amenities offered to them prior to the OLRSD were abysmal and hence ineffective. The intermediate titling complemented by upgrading efforts is resulting in the realisation of their right to adequate housing of those interviewed. Therefore, for these ‘slum’ residents whose lives have fraught with ‘poverty and policy traps’ (Marx et al. Citation2013, p. 188), OLRSD has provided a sense of dignity leading to their ‘formal incorporation into the official city’ (Payne, 1989; Gilbert Citation2000, p. 149).

The OLRSD is also an example of innovative solutions ensuring de jure tenure security without excessive resource burden on Government. Additionally, by providing a restricted instrument, not equivalent to a freehold title, the GoO has, to a certain extent and to date, prevented the rampant sale of titles, a major concern of policymakers in India (Datta Citation2006).

A shortcoming remains the challenge of facilitating access to credit, which typically property owners can access and which contributes to ‘wealth effects’. The unlocking of ‘dead capital’ through the formalisation of tenure rights comes with an increased vulnerability to over-indebtedness. Additional provisions are therefore required to improve access to finance concomitantly with capacity to repay.

Despite being at its early stages, the OLRSD has already been recognised for its welfare and progressive stance and for the political will involved in providing tenure security for more than a million residents. It has proved that ‘electoral democracy in India has partially forced elites to concede certain rights to the urban poor’ (Chatterjee, 2008; Hoelscher Citation2016) a modest reversal of ‘accumulation by dispossession’ (Chattaraj et al. Citation2017). Policies aiming at ‘slum-free cities’ in India have generally prioritised larger cities and ‘small cities/towns are stuck in the quagmire of underdevelopment’ (Kundu, 2006; Chandrasekhar and Sharma Citation2015, p. 86). Odisha, instead, is unique in attempting to prioritise smaller towns thus dispersing some gains of urbanisation to remote parts of the State setting precedents for other States to follow suit.

Neoliberal ideology may continue to foster ‘exclusionary urbanisation’ (Roy, 2004; Hagn Citation2016), slums designated as a ‘nuisance’ and residents as ‘secondary category of citizens’ (Ghertner, 2008; Roy Citation2009). GoO’s model may spawn similar titling and upgrading interventions in lesser-urbanised cities and towns. Further research on whether this policy outreach contributes to preventing new slums, will be of significance for a rapidly urbanising country. Lastly, of the nine settlements visited, four settlements had pucca houses prior to the LRCs. One settlement had 100% pucca houses while others varied. The remaining five settlements had kutcha houses and they were now constructing pucca houses through the support of housing subsidy. This suggests that the programme had limited, but significant benefits to low-income households.

(Manas/JF, 2019)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shobha Rao P.

Shobha Rao P. Independent Consultant. The research is based on the Master’s thesis produced by the lead author for the Centre for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), Cambridge University. Email: [email protected]

Jaime Royo-Olid

Jaime Royo-Olid, (PhD Candidate at the Centre of Development Studies, Cambridge University and Programme Officer at the European Commission)

Jan Turkstra

Dr. Jan Turkstra (UN Habitat)

Notes

1. Slum’ terminology has been long discredited and critiqued as pejorative, imprecise and over-simplistic (Gilbert Citation2007; Simon Citation2011). Instead, the preferred usage is ‘informal settlement’. In India, nevertheless, the ‘slum label’ has been co-opted by residents to gain access to basic services and other state resources (Burra Citation2005). While recognising these controversies, this paper will retain the term ‘slum’ to align with the Indian legal framework.

2. Tata Trusts is a philanthropic organisation founded by the TATA family (www.tatatrusts.org) and is coordinating the JAGA mission along with the Government of Odisha (GoO).

3. (Landesa, International Forestry Resources and Institutions, NRMC Centre for Land Governance and Regional Centre for Development Cooperation)

4. Based on the Orissa Survey and Settlement Act, 1958

5. Patta/Record of Rights (RoR) is the legal document issued by the Revenue Department, which establishes land ownership and specifies the location and dimensions of the land parcel and classification and whether the tenure is freehold or restricted. However, the process of obtaining an RoR is complex and obtaining an RoR can take anywhere from 3 months to 2 years depending on the availability of various papers and the complexity of the matter with the cost component varying between INR 150 (USD 2.5) to INR 8,000 (USD 125) (Das & Mukherjee, 2018: v &13).

6. OLRSD, 2017 defines a ‘slum’ as a compact settlement of at least twenty households with a collection of poorly built tenements, mostly of temporary nature, crowded together usually with inadequate sanitary and drinking water facilities in unhygienic conditions which maybe on the State Government land in an urban area (GoO Citation2017b:5)

7. Equivalent to USD 2473 (as on 15 February 2021)

8. Slum upgrading, in a narrow sense refers to ‘improvements in housing and/or basic infrastructure whilst in a broader sense, includes enhancements in the economic and social processes that can bring about such physical improvements (UN-Habitat, 2004:3; UN-Habitat Citation2014, p. 16).

9. (http://www.jagamission.org/) accessed on 25 September 2020. The institutional framework and process flow of the JAGA mission can be found at http://www.jagamission.org/pdf/Compendium%20Land%20Rights.pdf

10. Not to be confused with SPARC -The Society for The Promotion of Area Resource Centers. See SPARC Bhubaneswar use of drone technology for slum titling in:

http://sparcindia.com/blogs/how-drone-mapping-paved-way-to-the-worlds-largest-slum-land-titling-project/ accessed on 22 June 2020

11. Kutcha houses are non-durable houses made of plastic sheets, mud etc. while pucca houses are durable houses where the walls (and roof) are made up of bricks, concrete, stones and mortar, slate and metal sheets.

12. PMAY, 2015, the current GoI’s ‘Housing for All’ programme, has many components one of which provides subsidised housing to the EWS families to either construct new or upgrade existing houses, if they possess land ownership documentation (MHUPA, 2016:§7.1). For LRC beneficiaries, INR 150,000 (equivalent to USD 2,310) was provided through PMAY subsidy and INR 50,000 (equal to USD 770) by GoO’s AWAAS programme. The SBM is led by the Ministry of Housing & Urban Affairs (MoHUA) and aims to ensure universal sanitation coverage.

13. Tenable settlements are decided by the GoO and include sites, where existence of human habitation does not entail undue risk to the safety or health or life of the residents on such sites and where the settlement is not considered contrary to public interest or the land is not required for any public or development purpose (LGAF Citation2014). In general, ‘hazardous’ slums are defined in terms of environmental and health risks and ‘objectionable’ slums violate legal or master-plan norms, however the ‘challenge with tenability categorisations, is their arbitrary usage’ (Kundu Citation2011, pp. 2–3). Another incontrovertible challenge is slums on Central government land, which due to colonial legacy, is one of the biggest urban landowners. Yet, it does not allow tenure and services to be provided on its land (Burra Citation2005, p. 69). States that are willing to provide services to residents need a ‘no objection certificate’ (Subbaraman et al., 2012 in Nolan et al. Citation2018, p. 9) and thus, usually slums on Central Government lands are deemed untenable.

14. Katcha: Walls and roofs made of unburnt bricks, bamboo, mud, grass, leaves, reeds, thatch, etc. (Jain et al. Citation2016).

15. Ration cards are official documents given out by the Ministry of Food and Supply that entitle people living below the poverty line to buy a fixed quantity of subsidised food from local governmental fair-trade shops.

16. Sale of patta or slum land after regularisation is common in India. ‘It is widely believed in policy circles that allottees sell their houses to make a profit and then find another piece of vacant public land to squat upon’ (Datta Citation2006, p. 272). One instance of a titling programme within India that had conditional tenure is the case of the Rohini project in Delhi. This included plots for all income groups with conditions for the low income group plots that prevented their sale within five years. However, most plot owners sold out to estate agents using power of attorney, completely bypassing the restriction (Payne, interview transcript 2022)

17. There were many rumours about relocation. Relocation attempts were thus being undertaken at a slower pace, to ensure that relocatees did not return due to lack of basic services and livelihood opportunities in the relocation sites and relocation was thus not unsuccessful.

References

- ADB et al. (2019) Cyclone Fani Damage, Loss & Needs Assessment. pp. 1–275. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_732468.pdf.

- Anand, et al. (2017) Planning, “Violations”, and Urban Inclusion: A Study of Bhubaneswar. pp. 1–60. Available at: http://iihs.co.in/knowledge-gateway/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Bhubaneswar-Final.pdf.

- Aparna Das & Anindita Mukherjee (2018) Demystifying urban land tenure issues. pp. 1–37. Available at: www.giz.de/india.

- Banerjee B. 2002. Security of Tenure in Indian Cities. In: Durand-Lasserve A, editor. Holding Their Ground. 37–58. Available at. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781849771566/chapters/10.4324/9781849771566-11

- Bent Flyberrg. 2011. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study. In Qualitative Research Methods. 1–25. 10.4135/9780857028211

- Bromley DW. 2008. Land Use Policy Formalising property relations in the developing world : the wrong prescription for the wrong malady. Land Use Policy. 26(1):20–27. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.02.003.

- Bruce JW. 1998. Review of tenure terminology. 1:1–8. Available at. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/22013

- Burra S. 2005. Towards a pro-poor framework for slum upgrading in Mumbai, India. Environment & Urbanisation. 17(1):67–88. doi:10.1177/095624780501700106.

- Chandrasekhar S, Sharma A. 2015. Urbanization and Spatial Patterns of Internal Migration in India. Spatial Demography. 3(2):63–89. doi:10.1007/s40980-015-0006-0.

- Chant S. 2013. Cities through a “gender lens”: a golden “urban age” for women in the global South ? Environment & Urbanisation. 25(1):9–29. doi:10.1177/0956247813477809.

- Chattaraj D, Choudhury K, Joshi M. 2017. The Tenth Delhi: economy, politics and space in the post-liberalisation metropolis. Decision. 44(2):147–160. doi:10.1007/s40622-017-0154-8.

- Collin M (2013) Joint-titling of land and housing: Examples, causes and consequences. (EPS-PEAKS) pp. 1–26. Available at: http://partnerplatform.org/eps-peaks.

- Datta N. 2006. Joint Titling- A win-wn policy? Gender and Property rights in urban informal settlements in Chandigarh, India. Fem Econ. 12(1–2):271–298. doi:10.1080/13545700500508569.

- Dijk V. 2014. Subaltern urbanism in India beyond the mega-city slum: the civic politics of occupancy and development in two peripheral cities in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region.

- Dovey, King. 2011. Forms of informality : morphology and visibility of informal settlements. Built Environ. 37(1):11–29. Available at. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23289768.

- Dovey K. 2012. Informal urbanism and complex adaptive assemblage. International Development Planning Review. 34(4):349–367. doi:10.3828/idpr.2012.23.

- Durand-Lasserve et al. (2007) Social and economic impacts of land titling programmes in urban and peri-urban areas: A review of literature. (March) pp. 1–82. Available at: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/government-society/idd/research/social-economic-impacts/social-economic-impacts-literature-review.pdf.

- van Gelder, et al. 2015. Tenure security as a predictor of housing investment in low-income settlements: testing a tripartite model. Environment and Planning. 47(2):485–500. doi:10.1068/a130151p.

- van Gelder JL. 2013. Paradoxes of Urban Housing Informality in the Developing World. Law Soc Rev. 47(3):493–522. Available at. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43670344.

- Gelder V. 2010. What tenure security? The case for a tripartite view. Land Use Policy. 27(2):449–456. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.06.008.

- Gilbert A. 2000. Housing in Third World cities: the critical issues. Geography. 85(2):145–155. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/40573408

- Gilbert A. 2007. The return of the slum: does language matter? Int J Urban Reg Res. 31(4):697–713. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00754.x.

- GoO (2017) OLRSD, 2017. pp. 1–8. Available at: https://govtpress.odisha.gov.in/pdf/2017/1652.pdf.

- Hagn A. 2016. Of slums and politics in puri, odisha: the localisation of the slum-free cities mission in the Temple City. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal. 14:1–22. doi:10.4000/samaj.4226

- Harrison H, Birks M, Franklin R, et al. 2017. Case study research: foundations and methodological orientations. Forum Qualitative Social Research. 18(1):1–17.

- Hoelscher K. 2016. The evolution of the smart cities agenda in India. International Area Studies Review. 19(1):28–44. doi:10.1177/2233865916632089.

- Jain V, Chennuri S, Karamchandani A (2016) Informal Housing, Inadequate Property Rights. pp. 1–72. Available at: https://www.fsg.org/sites/default/files/publications/Informal Housing Inadequate Property Rights.pdf.

- Kim H, Yoon Y, Mutinda M. 2019. Secure land tenure for urban slum-dwellers : a conjoint experiment in Kenya. Habitat Int. 93:1–14.

- Kranthi N, Rao KD. 2010. A case of Hyderabad. Institute of Town Planners. 7(June):41–49. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1483007

- Kundu A (2011) Political economy of making indian cities slum-free. pp. 1–6. Available at: http://southasia.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/shared/events/21st_Century_Indian_City/Slums_2012/Panel_Amitab_Kundu_Paper.pdf.

- Kundu, Samanta. 2011. Redefining the Inclusive Urban Agenda in India. Econ Polit Wkly. 46(5):55–63. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/27918090

- LGAF (2014) Land Governance Assessment Framework State Level Report: Odisha. (August) pp. 1–212. Available at: https://landportal.org/library/resources/land-governance-assessment-framework-odisha-india.

- Mahadevia D. 2010. Tenure security and urban social protection links: India. IDS Bull. 41(4):52–62. Available at. https://www.academia.edu/24733891/Tenure_Security_and_Urban_Social_Protection_Links_India.

- Mahadevia, et al. 2018. Private sector in affordable housing? case of slum rehabilitation scheme in Ahmedabad, India. Environment & Urbanisation. 9(1):1–17. doi:10.1177/0975425317748449.

- Marx B, Stoker T, Suri T. 2013. The economics of slums in the developing world. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 27(4):187–210. doi:10.1257/jep.27.4.187.

- Mattingly M (2013) Briefing paper property rights and development: property rights and urban household welfare. (April) pp. 1–32. Available at: www.odi.org.uk.

- Mearns, Sinha. 1999. Social exclusion and land administration in Orissa, India. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2124. http://www.worldbank.org/html/dec/Publications/Workpapers/home.html

- Mohanty AK, Nayak NC, Chatterjee B. 2016. Does infrastructure affect human development? evidences from odisha, India. Journal of Infrastructure Development. 8(1):1–26. doi:10.1177/0974930616640086.

- Murthy SL. 2012. Land security and the challenges of realizing the human right to water and sanitation in the slums of Mumbai, India. Health Hum Rights. 14(2):61–73. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/healhumarigh.14.2.61

- Nakamura S. 2014. Impact of slum formalization on self-help housing construction: a case of slum notification in India. Urban Studies. 51(16):3420–3444. doi:10.1177/0042098013519139.

- Nakamura S. 2016. Revealing invisible rules in slums : the nexus between perceived tenure security and housing investment. Habitat Int. 53:151–162. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.029

- Nakamura S. 2017. Does slum formalisation without title provision stimulate housing improvement? A case of slum declaration in Pune, India. Urban Studies. 54(7):1715–1735. doi:10.1177/0042098016632433.

- Nolan, et al. 2018. Legal status and deprivation in urban slums over two decades. Econ Polit Wkly. 53(15):1–24.

- Patel K. 2016. Encountering the state through legal tenure security: perspectives from a low income resettlement scheme in urban India. Land Use Policy. 58:102–113. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.016

- Payne, et al. (2012) “holding on: security of tenure - types, policies, practices and challenges.” (October) pp. 1–76. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Housing/SecurityTenure/Payne-Durand-Lasserve-BackgroundPaper-JAN2013.pdf.

- Payne G. 2001. Urban land tenure policy options: titles or rights? Habitat Int. 25(3):415–429. doi:10.1016/S0197-3975(01)00014-5.

- Payne G. 2004. Land tenure and property rights: an introduction. Habitat Int. 28(2):167–179. doi:10.1016/S0197-3975(03)00066-3.

- Payne G, Durand-Lasserve A, Rakodi C. 2009. The limits of land titling and home ownership. Environ Urban. 21(2):443–462. doi:10.1177/0956247809344364.

- Pichel F, Dash SR, Mathivathanan G, et al. (2019) The Odisha Liveable Habitat Mission: The process and tools behind the world’s largest slum titling project. pp. 1–26. Available at: www.conftool.com.landandpoverty

- Prindex (2019) Global perceptions of urban land tenure security Evidence from 33 countries. (Attribution-(CC BY-NC 4.0)) pp. 1–28. Available at: https://www.odi.org/publications/11301-global-perceptions-urban-land-tenure-security-evidence-33-countries.

- Rakodi C. 2014. Expanding women’s access to land and housing in urban areas. 8:1–56. Available at. www.worldbank.org/gender/agency

- Roy A. 2009. Why India cannot plan its cities: informality, insurgence and the idiom of urbanisation. Planning Theory. 8(1):76–87. doi:10.1177/1473095208099299.

- Simon D. 2011. Situating slums. City. 15(6):674–685. doi:10.1080/13604813.2011.609011.

- Sinha BK. 2014. Land reforms: evidences of reversal in Orissa. Journal of Land and Rural Studies. 2(2):171–190. doi:10.1177/2321024914534048.

- Sjaastad E, Bromley DW. 2000. The prejudices of property rights: on individualism, specificity, and security in property regimes. Development Policy Review. 18(4):1–26. doi:10.1111/1467-7679.00117.

- Sjaastad E, Cousins B. 2008. Formalisation of land rights in the South: an overview. Land Use Policy. 26(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.05.004.

- The Bridgespan Group (2017) Odisha: Land rights to slum dwellers (work flow process maps). Available at: www.bridgespan.org.

- Tumbe C (2016) Urbanisation, demographic transition, and the growth of cities in India, 1870-2020. IGC. pp.1–41. Available at: https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Tumbe-2016-Working-paper.pdf.

- UN-Habitat (2014) A Practical Guide to Designing, Planning, and Executing Citywide Slum Upgrading Programmes. pp. 1–167. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Housing/InformalSettlements/UNHABITAT_A_PracticalGuidetoDesigningPlaningandExecutingCitywideSlum.pdf.

- UN Human Rights Council (2012) Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context. (A/HRC/22/46) pp. 1–22. Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G12/189/79/PDF/G1218979.pdf?OpenElement.

- UNDP (2008) Land Rights and Ownership in Orissa. pp. 1–74. Available at: http://www.undp.org.in.

- Varley A. 2007. Gender and Property Formalization: conventional and Alternative Approaches. World Dev. 35(10):1739–1753. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.06.005.

- Varley A. 2017. Property titles and the urban poor: from informality to displacement? Planning Theory & Practice. 18(3):385–404. doi:10.1080/14649357.2016.1235223.