ABSTRACT

Based on a case study of Alexandria city, Egypt, this paper investigates the configuration, interrelation, and integration of urban expansion within the framework of sustainability transitions to enhance the performance of sociotechnical transitions. It explores two main arguments; first, to evaluate the recent urban planning innovations, and second, to raise awareness of the participatory planning model to enhance the involvement of the three pillars to better integrate urban sustainable development. It presumes there is a linkage between urban sustainability transitions and the geographical transitions. It further evaluates whether this linkage would benefit accommodating the rapid population growth of Alexandria. This research applies an empirical methodology to test concepts and patterns known from theory generating three scenarios from empirical data. Moving beyond the ‘niche–regime dichotomy’, this study concludes that innovative practices and vested interests are typically constituted in a dualistic manner and tend to incite processes of change in both.

1 Introduction

Cities in the Global South are growing at an extraordinary pace. To begin, it was argued that urbanisation is uplifting the level of living for many inhabitants. It has not been inclusive, and arbitrary dualistic urban growth patterns have created several spatial urban expansion challenges that have impeded the development process (UN-Habitat Citation2016a). Three challenges confront urban expansion around the world: environmental deterioration, climatic change, and socioeconomic inequity (Kanger and Schot Citation2018). These challenges are fundamentally linked to the ‘First Deep Transition’, which refers to the functioning of societal subsystems such as poverty, urban duality, and the economy (e.g. (Piketty Citation2014; Moore Citation2015); or the particular ‘Western’ mode of thinking (e.g. (LaFreniere Citation2007; Lamba Citation2010), or Latin American mode of thinking (Roy Citation2009). The ‘Second-Deep Transition’ (Kanger and Schot Citation2018) refers to the development and expansion of a wide range of socio-technical systems for the provision of land, transport, energy, food, housing, healthcare, communications, and other purpose, as well as the reduction of social inequality. The ‘Third Deep Transition’ describes the impact of climate change on biodiversity loss, as well as spatial and ecological hazards that have threatened the planet, whether in the past, present, or future. On the other hand, urban expansion transitions characterise the overall dynamics that emerge from land use, urban functions, and the natural environment (Tong et al. Citation2019), as well as their spatial consequences on the built environment’s quality and their impact on the triple deep transitions. By the turn of the Third Millennium, a new research arena had emerged, enquiring the ties between theory and practice in urban sustainability transitions, in order to tackle the socio-economic, spatial, and political upheavals of the Global North and South. This research arena aims to guide natural resources towards present and future generations’ needs. On the other hand, there is a pressing need to safeguard the planet from three hazards: climatic changes, biodiversity loss, and spatial degradation.

The Egyptian government’s failure to establish land and housing policies, as well as the formal private sector’s inability to provide land for housing and other social amenities for the poor, has bolstered the appeal of informal land markets and the call for practical land governance (Durand-lasserve Citation2005; Payne et al. Citation2009; Soliman Citation2010; Nada and Sims Citation2021) Furthermore, the majority of Egypt’s dualistic urbanisation and other informal land usage have expanded to the outskirts of the country’s major cities in the form of unlawful land expansion (Salem et al. Citation2020). In this unprecedented era of increasing formal/informal urbanisation, and within the context of Habitat III; this paper highlights the evolution of planning innovation in sustainability transitions on land for urban expansion in Egypt.

Therefore, this paper explores two key arguments: first, whether modern urban planning innovations have successfully integrated urban land expansion with the urban surroundings. Second, it raises awareness of the participatory planning model to enhance the involvement of the three pillars to better integrate urban sustainable development. Finally, the aim is to reach a practical and applicable approach for urban land expansion, as well as to adapt the current planning policies with urban sustainability transitions. Therefore, the goal is to meet the immediate and future population’s housing demands in order to alleviate poverty on the one hand, while avoiding the eradication of the built environment on the other. The central assumption draws the correlation between urban sustainability transitions and geographic transitions, determining whether or not to benefit Alexandria’s rapid population increase. Is there a prospect that land value capture may permit development cost sharing? This research applies an empirical methodology to test concepts and patterns known from theory and practice using a new empirical data. Theoretically, there is enormous literature appraising the theory of sustainability transitions. Practically, the research examines the duality phenomenon of sociotechnical concerning urban land expansion and the application of urban sustainability transitions. Thereafter, the differentiation between various potentialities for urban expansion is explored. In addition, integrating the application of urban sustainability transitions and future urban expansion is critical to achieve sustainable development. The research explains the influence of sociotechnical duality on both the processes of sustainability transitions, and the outcomes of future urban expansion.

The scarcity of the literature on the spatial component of planning and urban/physical expansion in dense cities (Mguni Citation2015; Wieczorek Citation2018), which covers the thorough experience of applying sustainable transitions in both the Global North and South, is a major limitation of this study. Furthermore, most studies on sustainable transitions have relied on looking backward at a case study to determine the driving forces for such transitions (Grin et al. Citation2010). Therefore, this work has relied on the basic idea that a comprehensive assessment of a city’s background and evolution across time (such as Alexandria, Egypt) can be used to establish alternative benchmarks. It must emphasise that some areas in Alexandria are developing according to some planning documents while others are developing completely spontaneously. It can lead to case-specific baselines and targets that can influence analysis, the decision-making process, and consequently, the prospects of intervention in an existing city.

The paper is structured into five sections. The present section includes the research’s key concepts, whereas sections two and three look at rapid urbanisation and urban development, and section four looks at sustainability transitions and urban expansion. The fifth section looks into the possibilities of Alexandria’s spatial sustainability expansion transitions. Beyond the ‘niche–regime dichotomy,’ this research suggests that creative practices and vested interests are often constituted in a dualistic fashion, and that both tend to provoke change processes. This calls into question several long-held beliefs about sustainable transitions. Both theory and practice tend to smooth over such sensitivity in favour of place-blind theory and practice that are thought to be valid in Egypt.

2 The rapid urbanisation and urban expansion

The first Global Conference of Habitat I (Ward Citation1976) was an alarm for the Global South to deal with arbitrary urban growth and rapid population growth, thus contributing to healthy human settlements. Specific attention was given to three core conceptual areas that continuously surfaced throughout the conference and require further elaboration: sustainability, land degradation, and peri-urban expansion. Many studies have been conducted to link urbanisation to many environmental issues that have harmed the built environment. Also, heed was given to the impacts of urban pressures, particularly those being played out in peri-urban localities on land, society, and social sustainability (Maconachie Citation2007; Keivani and Shirazi Citation2019). Now, many urban challenges are facing the Global South, such as social inequality, climate change, informal urbanisation process, urban informality, the scarcity of job creation, and unsustainable forms of urban expansion (UN-Habitat Citation2016a).

Most cities in the Global South are suffering from rapid informal urbanisation, where informal land markets flourished on their peripheries. This arbitrary urban expansion is associated with an unstoppable phenomenon of informal urbanisation. Unfortunately, this phenomenon has deteriorated the urban fabric of cities in the Global South. The New Urban Agenda (NUA) indicates that urbanisation is an engine for development, and proper geographical transitions. It is considered the main driver for formulating a healthy urban fabric (UN-Habitat Citation2016b). The quality of urban fabric production is determined by cooperation among the three pillars of the state, capital, and society, by which they control the geographical transitions. Furthermore, the involvement of various stakeholders is driving the forces to create a healthy environment. Many cities in the Global South are struggling with fragmented urban growth accompanied by high levels of social inequality, where urban informality continues to prosper in the periphery of cities. This fragmented urban growth has been confronted by the three deep transitions of environmental degradation, climatic change, and social inequality. It has also had been to deal with the dualities of sociotechnical and political transformation that dominated the cities of the Global South. The geographical transitions and urban expansion in the Global South have rarely touched on the duality phenomenon (Soliman Citation2021). The rapid growth of urban expansion causes radical transitions in the geographical settings in which arbitrary physical transitions have dominated the growth of cities in the Global South. Geographic transitions are thus coevolutionary processes involving changes in a variety of element, including capital, social behaviour, politics, and resources. It is also the transformative processes linking production, reproduction, distribution, and consumption of goods and services extracted from non-natural and natural resources that influence the degree of quality of the built environment and determine the urban fabric systems of a given setting.

UN-Habitat estimates that there are 881 million people currently living in slums in cities of the South compared to 791 million in the year 2000. By 2025, another 1.6 billion are likely to require adequate, affordable housing (UN-Habitat, Citation2016a). It argued (UN-Habitat Citation2016a) that slums are the products of failed policies, poor governance, corruption, inappropriate regulation, dysfunctional land markets, unresponsive financial systems, and a lack of political desire. However, the persistence of poverty, growing social inequalities, and environmental degradation are among the major urban challenges that face the sustainable development worldwide. Social and economic exclusion and spatial segregation are often an irrefutable reality in cities and human settlements in the South. On the other hand, urbanisation’s potential contributions to achieving transformative development constitute an ambitious roadmap for a sustainable development transition (UN-Habitat Citation2016b). The main component of arbitrary spatial urban growth is the production of urban informality (Pugh Citation1997) associated with the spread of the informal economy. Thus, urban informality is a physical and spatial manifestation of urban poverty, the duality of the economy, and intra-city inequality (Soliman Citation2021). However, urban informality does not accommodate all of the urban poor, nor all slum dwellers are always poor (UN-Habitat Citation2003), but the middle-income classes have been squeezed as well. Therefore, the arbitrary urban expansion on the periphery of cities is a direct response to the growing population of cities in the South.

Turner’s view of self-help housing in Habitat I became a theory and a practice of low-income housing development in the hands of the World Bank. Since the 1980s, the role has changed partly because policies have changed, requiring different purposes in different contexts (Pugh Citation1997), in different ideologies (De Soto Citation1989, Citation2000), different communications technologies (Castells Citation2010), and different perspectives (Soliman Citation2021). Also, if Turner quizzed housing as not what it is, but what it does in people’s lives, it could be argued that housing is what it does to the urban fabric and urban morphology of a given environment (Soliman Citation2019), and how it has affected the sustainability of the urban fabric of cities. However, urban informality is ‘a dynamic, transactive, transformative, and transmissive space’ that better responds to evolving circumstances and contemporary national challenges in a wholly formal or informal private land market. It is being integrated with the socioeconomic and political circumstances of the country (Soliman Citation2020). This development relied heavily on illegal land subdivisions on the fringes of urban areas, accelerated by the shadow economy and characterised by social exclusion and deteriorated natural resources to the point that the final urban fabric is unsustainable. The question is how to integrate or interrelate urban informality within the formal context. However, how it could benefit from urbanisation as an engine for development in a sustainable way by remoulding the arbitrary spatial growth of cities in the Global South.

Therefore, the NUA (UN-Habitat Citation2016b) announced transformative commitments through an urban paradigm shift grounded in the integrated and inseparable three dimensions of sustainable development. These are sustainable urban development for social inclusion and ending poverty; sustainable and inclusive urban prosperity and opportunities for all; and finally, environmentally sustainable, and resilient urban development. The three dimensions have reflected the three goals of 1, 5, and 11 of the SDGs by which it would decrease the level of poverty, ensure social equity, reduce the proportion of the global urban population living in slums, empower women, and promote gender equality to accelerating sustainable development. These goals are trying to reduce cities’ densities and create a healthy environment with basic human needs. They are trying to regulate the arbitrary development within the urban areas. However, informal spatial growth has to be tackled by integrating these three dimensions to create a sustainable environment that may be accomplished through the SDGs.

In Egypt, arbitrary urbanisation processes and rapid population growth have increased the demand for housing plots for low-income groups. Informal rapid urbanisation coinciding with a long time of political and socio-economic transitions in modern Egypt has created an enormous demand for housing plots and subsequently the spreading of spatial arbitrary urban expansion on the periphery of Egyptian cities (Khalifa Citation2015; Abu Hatab et al. Citation2019; Salem et al. Citation2020). Between 1996 and 2006, over 65% of all urban housing production was deemed informal (Soliman Citation2019). After the two Revolutions of 2011, 2013, informal housing production has increased exponentially that is now totally dominant in urban, peri-urban, and rural areas on the Egyptian landscape (Youm7 Citation2016). Also, President Abd Al-Fatah El Sisi declared that more than 50% of urban, and rural agglomerations in Egypt are informal (Soliman Citation2019). It is estimated that Egypt’s population has risen 22.0 million people over the past decade from 72.8 million people in 2006 to 94.78 million people in 2017, giving an annual increase of 2.2 million people (CAPMAS Citation2016). Today, the total population of Egypt ranges more than 103 million people (CAPMAS Citation2022). If the current population growth rates of 1.4%, 1.6% and 1.8% are maintained, Egypt’s population will reach more than 152.08, 162.62, and 180.0 million respectively by the year 2050 (Soliman Citation2021). This will necessitate the addition of at least half to two-thirds of the current urban and rural agglomerations to Egyptian territory in order to satisfy future housing plots as well as numerous social amenities. Alternatively, Egypt will need to build and put in operation of around 30 new cities, each should accommodate around 2.5 million people till the year 2050. Furthermore, if existing housing policy and planning ideas are continued, 50% of future urban and rural expansion will be dispersed informally on nearby agricultural land on the outskirts of cities. . The total area of Egypt is about 1,002,000 square kilometres and the inhabited area around 78,990 km2 given around 7.8% of the total area, therefore, the needed future urban and rural agglomeration, about 6.5% of the total area of Egypt, will be informal (Soliman CitationForthcoming).

On the other hand, in 2016, the total number of housing units in Egypt arrived at 42.97 million units. This is nearly double the number of households (23.45 million), resulting in a 19.52 million housing unit surplus. In 2016, 14.58 million housing units were anticipated to be out of the real estate market in Egypt’s urban areas, with 6.40 million units unoccupied and 8.18 million units closed (CAPMAS Citation2016; Soliman Citation2022). Units are traditionally kept vacant with the expectation that children will inhabit them after marriage as well as for speculation purposes. Another explanation is that the sustained rapid construction over the past 25 years and the relative lack of alternative investment avenues made real estate an inflation-proof savings and investment mechanism, even without a rental yield. Continued uncertainty about the enforceability of the new rental law makes many owners hesitant to let their unoccupied units. This brief background provides an opportunity to consider the future of Egypt’s urban fabric. It also queries how to address present and future new urban expansion to meet housing needs and other social amenities. With the implementation of the General Strategy Urban Plan (GSUP) for 229 cities, 4632 villages, and 27,000 hamlets, it is expected that Egypt will lose formally around 113,300 (Soliman Citation2010), 207,860 (Toth Citation2009), and 13,500 feddansFootnote1 of agricultural areas surrounding Egyptian cities, villages, and hamlets respectively to the year 2027. Given a total loss of agricultural land of 334,660 feddan, or an annual loss of 23,904 feddan. As illustrated in , during the period 2011–2014 and after the two revolts of January 25th, 2011, and June 30th, 2013,, Egypt witnessed the loss of 150,000–200,000 feddan of precious fertile agricultural land to illegal urban sprawl. This was due to the chaotic situation in the country during the two revolts. Combined with this arbitrary urban sprawl, a multitude of urban challenges have emerged from the rapid increase of Egypt’s population to nearly 103 million people (CAPMAS Citation2022). Taking the average loss of 16,733 feddan per year, Egypt will lose all its agricultural land, around five million feddan, within nearly 300 years. Despite the stability of the political context, Egypt has radically changed after two revolts on 25 January 2011 and 30 June 2013, but until now, nothing has been done on the ground to prevent or alleviate the loss of agricultural land to urban informality. Currently, the state of Egypt introduced the Buildings Violations Temporary Reconciliation Law number 17 of 2019 and simplified the procedure of law No. 114 of 1946 for land registration at the Property Proclamation Department to facilitate the registration of real estate properties. There are many new cities under construction outside of the crowded Nile valley. The outcomes of these procedures are still a mystery (Soliman Citation2022).

Table 1. Illustrates the loss of Agricultural land to urban sprawl between 2007–2021

These statistics reinforce the argument that the urban housing crisis in Egypt is not a problem of scarcity of housing units. Rather, it is a result of distorted urban planning and housing policies. An accumulation of ill-conceived and inadequate policies has led over time to a mismatch between supply and demand and severely curtailed private sector investment in housing production. The failure of the government to ensure affordable and viable housing for the urban poor has led many to build homes -semi-legally or illegally- on privately owned agricultural land. Thus, housing informality, or Ashwaiyyat, inevitably became the prototype of the housing delivery system, accommodating the growing population of the urban poor. However, the current planning policies have to be modified or at least be adjusted to achieve three requirements: to implement the NUA, to achieve the commitment of the Egyptian government to the SDGs by 2030, and finally, to meet the increasing demand for land to accommodate future population growth.

3 Sustainability transitions and urban expansion

In the last few years, new planning innovations have taken place aimed at sustainability transitions for the future of urban agglomeration development on the planet. These are diversified in terms of topics and geographical applications and deepened about theories and methods (Köhler et al. Citation2019). Research on sustainability transitions has become a collective, productive, and highly cumulative endeavour (Köhler et al. Citation2019). Transitions in sustainability are shifts or ‘system innovations’ between distinctive socio-technical configurations, encompassing not only new technologies but also corresponding to changes in market forces, user practices, policy, cultural discourses, and governing institutions (Geels et al. Citation2008; Markard et al. Citation2012). A transition, in a simple term, is a shift, negatively or positively, from a certain condition/status to another. Leftwich (Citation2010) defines transitions as all the activities of co-operation and conflict, within and between societies, whereby the human species organises the consumption, production, and distribution of human, natural, and other resources for the production and reproduction of its biological and social life. Transitions are be conceptualised and explain how radical changes can occur in the way societal functions are fulfilled (Koehler et al. Citation2017). On the other hand, sustainability transitions are system innovations that influence geographical settings through changes in socio-technical, economic-technical, and political economy configurations in a specific location (international, national, or local) or a specific context (e.g., housing production, street trading, land market, land tenure, etc.). Transitions are changing the behaviour of humans, changing the urban pattern, and organising natural resources in a sustainable way to meet the needs of a population. It is also the result of transformative processes linking production, reproduction, distribution, and consumption of goods and services extracted for non-natural and natural resources, which influence the degree of quality of the built environment and determine the urban fabric and the geographical systems of a given setting. Transitions are, therefore, coevolutionary processes, involving changes in a range of elements such as capital, social behaviour, politics, and dimensions. Sustainable transitions are brought about by unsustainable consumption, production, reproduction, and distribution patterns in socio-technical systems such as electricity, heat, buildings, mobility, and land use. These transitions occur according to several variables; co-evolution and multiple changes in socio-technical systems, multi-actor interactions between social groups, ‘radical’ change in terms of scope of change, and periods that witness transitions (Geels and Schot Citation2007).

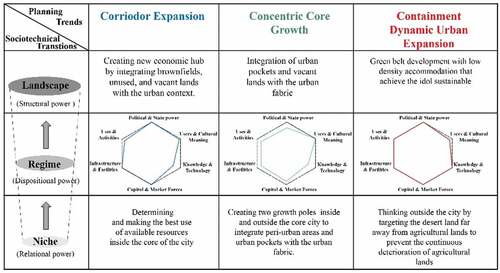

The sociotechnical perspective represents the correlation between technology and society and how each of them influences the other. In the spatial configuration, the sociotechnical perspective is related to transitions that occurred in the geographical contexts. Therefore, sociotechnical systems, as a multi-dimensionality and co-evolution, consist of multiple elements: technologies, markets/capital, user practices, cultural meanings, infrastructures, policies, industry structures, and supply and distribution chains. Furthermore, Grin et al. (Citation2010) connects the Multi-level Perspectives (MLP) as a sociotechnical system tool to an already existing multi-levelled power framework (Arts and Van Tatenhove Citation2004). As illustrated in , Grin et al. (Citation2010) argue that the three levels of power distinguished correspond to the three levels of transition dynamics: (a) relational power at the level of niches, (b) dispositional power at the level of regimes, and (c) structural power at the level of landscapes. On the other hand, the power of the law at the three levels plays a critical role in determining the level of transitions at which law in text differs from law in practice or spiritual law. The latter applies on the ground of urban informality. In such a plural realm, the law of the state is not necessarily the dominant one. Furthermore, the state might not have the capacity to enforce the law (McAuslan Citation2013). Soliman (Citation2019) supports this argument by stating that there are differentiations between the written law and the practiced law. The latter is shaped by people, not only the poor but also the rich, to adapt the law according to their interests and to serve their objectives of gaining extra capital out of playing with the law. The differentiation between the two laws has encouraged people in the Global South to act illegally in their built environment, in which urban informality has flourished (Soliman Citation2017).

Figure 1. Linkage between the three levels of powers and the MLP process.

In the Global South, the rapid growth of informal urbanisation causes radical transitions in the geographical settings in which arbitrary physical transitions have dominated their cities (Soliman Citation2020). Geographical transitions and expansion are a very rare phenomenon in the Global South (Soliman Citation2021). The government’s responsibility is the development of locations with basic urban services to provide affordable land plots for new generations. In other words, the government should provide things that most of the population cannot provide for themselves, while the construction of houses is the responsibility of the citizens.

As shown in , the relationship between sustainable transitions processes and spatial transitions of land redevelopment is influenced by four major variables: sustainable transitions dimensions, transitions concepts, transition levels, and intervention levels. Land redevelopment as complex adaptive systems (Rotmans Citation2006) is in a continuous process of rapid land mechanism changes and has the opportunity to be sustainably integrated into the urban context. This inherent complexity requires thinking of land redevelopment in Egyptian cities as never being finished and facing continuous change.

Figure 2. The correlation between sustainable transitions and land redevelopment Transitions.

The first variable is sustainable transition dimensions. It is linked and integrated with land redevelopment transitions in which three themes are emphasised: complex systems analysis, a sociotechnical perspective, and a governance perspective. These themes are part of a continuous complex of processes and are related and linked to the concept of transitions, transition level, and level of intervention. The first theme is complex systems analyses. It reflects the transition approach, which distinguishes three different levels of analysis (three pillars): relations between the market, government, and society, and their impressions on lifestyles. It also reflects the production, reproduction, distribution, and consumption of spaces within spaces in which certain commodities, such as land or activities, are produced. In this sense, land redevelopment changes can occur through complex interactions between the three pillars, giving total control of the spatial development of a city in Egypt (Soliman Citation2017). The second theme is socio-technical systems, which are the combinations of humans and non-humans that create functional configurations that work (Grin et al. Citation2010). Power is primarily understood in terms of the regulative, cognitive, and normative rules underlying socio-technical regimes, and the ‘power struggles’ between incumbent regimes and upcoming niches. Position power, according to Geels and Schot (Citation2010), is a specific perspective on agency that revolves around actors and social groups with ‘conflicting goals and interests,’ and views change as the result of “conflicts, power struggles, contestations, lobbying, coalition building, and bargaining”. In this perspective, a social struggle over the security of land tenure constitutes a major challenge to combat between incumbent regimes and upcoming niches. The third theme is the governance perspective on transitions, which discusses transition agency in terms of agents’ capacity to ‘act otherwise’ and trigger institutional transformation by ‘smartly playing into power dynamics at various layers’ and various settings (such as Cairo and Alexandria). In this regard, the correlations between the three pillars play a critical role in accelerating the formalisation of land for development.

The second variable is the concept of transitions. Grin et al. (Citation2010) try to analyse the sociotechnical perspectives through linking four issues: co-evolution, the multilevel perspective, the multi-phase process, and the co-design and learning course. The four issues represent functional relationships between actors, structures, and working practices that are closely linked. The higher the scale level, the more aggregated the components and the relations, and the slower the dynamics are between the three pillars. In the first issue, in a biological or economic context, co-evolution refers to the mutual selection of two or more evolving populations. It is the interaction between societal subsystems that influences the dynamics of the individual societal subsystems, leading to irreversible patterns of land delivery. The second issue is the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) in which it conceives of transition as the interference of processes at three levels; niche, regime, and landscape (see ). The central level comprises socio-technical regimes; sets of rules and routines that define the dominant ‘way of doing things’. Regimes account for path-dependence, stability, and are often locked-in, or locked-out, which hinders radical change in land mechanisms. Regimes are stabilised by the socio-technical landscape, a broad exogenous environment, and what time consumes. The landscape encompasses such processes as urbanisation, demographic changes, and market forces that can put pressure on regimes, making them vulnerable to more radical changes. Regimes transform on the condition of the availability of alternatives to a land delivery system that can fulfil the same societal function. The third overarching issue is the Multi-Phase (MP) concept to describe a land delivery and transition in time as a sequence of four alternating phases: (i) the pre-development phase, from a dynamic state of equilibrium in which the status quo of the land changes in the background, but these changes are not visible; (ii) the take-off phase, the actual point of ignition after which the process of structural change picks up momentum; (iii) the acceleration phase in which structural changes become visible; (iv) the stabilisation phase where a new dynamic state of equilibrium is achieved. The final shared issue is that of co-design and learning (Grin et al. Citation2010; Grin and Loeber Citation2007), sometimes called learning by doing, and doing by learning. It signifies that knowledge has been created through a sophisticated, interactive design process involving the three pillars and a social learning process.

The third variable is the transitional levels, which represent an integrated and cross-sectoral approach (horizontal and vertical coordination). The transition process occurs at the horizontal and vertical coordination levels. The former occurs at three levels; macro, meso, and micro; while the latter occurs at various stages of land transitions. These levels are responsible for facilitating the integration of land redevelopment into the urban context and enhancing the land delivery system for low- and middle-income groups.

The final variable is the level of intervention, which is dramatically varied according to various aspects of transitions, and settings. It occurs at two stages of the process: at the beginning and at the end. While financing and investing have lasting effects, the concentration of resources and funding on selected target areas is considered the main tool for active intervention. Also, capitalising on knowledge, exchanging experience and know-how (benchmarking, networking), or learning by doing are concrete methods to control or speed up the level of land transitions. Social networks, actors, and institutions are promoting ‘lock-in’ or ‘locked-out’ and path dependency (Soliman Citation2019; Dixon et al. Citation2014). Monitoring the progress (ex-ante, mid-term, ex-post evaluations, and indicators) is the main indicator to accelerate the land delivery process.

Also, the conceptualisation of the local community level (grassroots level) (Seyfang and Smith Citation2007; Soliman Citation2012, Citation2017), as a valid site for innovation towards land redevelopment sustainability is pursued, i.e., as constituting the niche level in urban areas. The potential and accomplishments of diverse types of a community’s initiatives are acknowledged as transformative change for sustainability articulated around alternative values and social practices for land delivery. Despite increased attention in the transition literature to the thoughts of these transformations (Hoffman Citation2013; Geels Citation2014; Avelino et al. Citation2016), a closer look at the questions of which transformation is for whom, how, why, when, and by whom is required. These questions are relative to Egyptian cities as most of these cities exhibit tremendous illnesses in their geographical, social, economic, and political aspects. Egyptian cities are also characterised by ill-functioning institutions, fluctuations in economic status, client lists, socially exclusive communities, and many proletarians (for example see Sims Citation2014; Payne Citation2022). In Egypt, informal institutions such as norms, values, and cultures play a pivotal role in land delivery and transition processes. They either shape informal institutions that account for more than half of the real estate economy, or they prevail when formal institutions and markets fail.

4 Potentialities of spatial sustainability expansion transitions of Alexandria

The following part highlights the effect of the urban potentialities on the development of Alexandria City and how beneficial the historical development transitions can be in favour of setting up the future urban expansion scenarios for the city. It starts by giving a brief overview of the historical development of the city, then a subsection explores planning principles, formulating criteria, and building scenarios.

4.1 Historical development of the city of Alexandria

Throughout the historical development of the city of Alexandria (see ), several urban expansion potentialities were touched. These potentialities are considered a road map for proposing future urban expansion policies for the city. They are grouped into six main potentialities: the accumulation of capital through market forces, the availability of infrastructure and utilities, political and state power, users and cultural meaning, knowledge and technology, and finally uses and activities. Each one is extracted from the progress of the urban expansion of the city over history.

During the Greek era (332–333 B.C.), Alexandria was surrounded by a great wall to defend the city and to define the development of the city as well. It was divided into four main neighbourhoods, each of which had its own design and category of people. Capital and market forces, users and cultural meanings, infrastructure, social facilities, uses and activities, and knowledge were reflected in the urban fabric of the city. During the Roman era, Alexandria was pretty much the same unless you lived in a small neighbourhood, as the first urban expansion, named Nicopolis, was constructed briefly after the wall because of the war against Cleopatra. It was planned to be integrated with the main road network. Also, political power has a great influence on shaping the city.

The third is during the Islamic era, as the city witnessed the first negative transition as it shrank from the east and south when Al-Fusṭāṭ replaced Alexandria and became the capital of Egypt. As a result, it has lost its role in international connection, political power, knowledge, and learning after the great library was destroyed. It is argued that political instability has a negative direct impact on urban growth by lowering the rates of productivity, as well as human and physical accumulation growth (Aisen and Jose Citation2013). Later, at the beginning of the Ottoman era, Alexandria faced the second deterioration as it shrank even more, formulating what was called ‘Turkish City’. This transition was because the city had lost its significant role in industry and trading due to the discovery of Cape of Good Hope Road.

In the modern era, Alexandria began to flourish at the beginning of the 19th century after the construction of the Mahmoudeya Canal in 1821 and the railway track between Alexandria and Cairo in 1854. In addition, the appearance of car technology had a great influence on the urban fabric of the city. The advanced technological potentialities made a whole new transition in Alexandria’s history in trading, industry, navigation, and urbanisation. Afterwards, at the end of the 19th century, the urbanisation extended in three directions: south, east, and west, reaching the Mahmoudeya Canal in the south and Moharam Bek in the east. It is argued that adequate infrastructure, such as improved water and sanitation, and efficient transportation networks, such as the railway train, have a significant impact on city productivity and connectivity (Arimah Citation2016). Capital accumulation through market forces, infrastructure, tramlines (UITP Citation2009), political and state power, knowledge, and technology appears to have had a significant impact on the city’s flourishing in this era.

At the beginning of the 20th century, in 1918, the Scottish engineer William H. McLean planned the city of Alexandria, in which he proposed to extend the city’s boundary in various directions, to create public spaces, and to develop the road network to cope with the development of car technology. The construction of the Cornish Road linked El Montazah Palace in the east with the Ras Al-Teen Palace in the west. As a result, the urbanisation crawled along the Cornish Road towards the east. McLean’s plan depended on a road network, facilitating transportation between various parts of the city and even extending towards Borg El Arab City in the west. McLane imagined a new suburban garden city in Agami as a summer sea resort in the far west and another one called Smouha to replace El Hadra Lake (Pallini and Scaccabarozzi Citation2016).

After the wars of 1967 and 1973, Alexandria faced a third deterioration when formal development was halted. However, demographic growth did not stop. Also, the displacement of people from Suez Canal cities to Alexandria has led to informal urban expansion on the urban fringe. After this crisis, New Bourg Arab City was constructed in the far west in 1979, as a reflection of new town policy, which failed to attract 30% of the expected population due to the absence of public transportation, job opportunities, and facilities.

Before the beginning of the Third Millennium, the Comprehensive Master Plan of 2005 was submitted in order to control the arbitrary urban expansion on the adjacent agricultural land by directing the new urban expansion towards the west (Dix Citation1986). Unfortunately, due to the lack of a clear vision for the needed land for urban expansion, the sea resort of El Agami was converted into an informal settlement to fulfill the housing needs. Currently, urban informality has accelerated in the core city, and on the periphery of the city. Most old buildings were demolished and replaced by new ones with high-rise buildings neglecting the building code and government restrictions (Nassar Citation2016). This phenomenon, called ‘crisis construction’, leads to high-density areas in various parts of the city. The General Strategic Urban Plan of Alexandria 2032 was introduced in 2015 to examine three subject areas: land, shelter, and local economic development (GOPP Citation2015). The main recommendation of the plan is to direct the new urban expansion towards the west by focusing on the development of the El Ameriyah area to absorb the expected population growth. Another is that the Alexandria core area experiences moderate growth, mostly through belting the unplanned areas while still providing adequate land for development inside the urban area.

The abovementioned potentialities are the basis for shedding light on its influence on the urban expansion process. First, the accumulation of capital through enhancing market forces is facilitating economic growth. Furthermore, it is accelerating the speed of development. Second, the construction of reasonable and reliable infrastructure and facilities is attracting people from inner crowded areas of the city to low-density areas. Third, the willingness of the state to move people from crowded areas to new areas to be able to meet the increasing demand for housing and other economic activities, and further, to cope with the rapid transition process. Fourth, to create a sustainable environment to satisfy the residents’ requirements and to create social inclusion rather than social exclusion, which meets the various requirements of different classes. Fifth, knowledge and technology are playing an important part in the socio-spatial expansion. Finally, the creation of mixed land uses, and activities is helping in accelerating the new expansion process and is opening the doors for new investors to conquer the newly established areas, which also provide access to various facilities within a short distance. These potentialities are the basis for formulating the desired criteria.

4.2 Planning principles, formulating criteria, and building scenarios

This part is anticipated to extract some planning principles to determine certain criteria to be used in generating various scenarios. Short-listed questionaries were sent through the internet to governmental bodies, planning professionals, and experts in the city. It re-assesses evidence from the literature review to identify the effectiveness of the hypotheses of the study. The socio-technical perspective of niche, regime, and landscape is utilised to examine the different aspects that influence the direction of future urban sustainable expansion transitions.

The future sustainable urban expansion transitions in Alexandria rely on various planning principles. This is the continuously changing arena of development, the willingness of the state to future urban development, changing the direction of urban growth, changing the modes of demand and supply, to fulfill the requirements of the bottom strata of society, and changing urban living behaviour. They reflect the willingness of the three pillars of the state, capital, and society to accelerate or decrease the geographical transitions of a given area. These planning principles are flexible, robust, and have great untapped potential to account for demand and supply factors more fully. On the other hand, these planning principles can be used to accelerate hierarchical social, retail, and marketing function transitions. It can determine how many sites are required to provide everyone with various access points to central development hubs. However, the deduced criteria are to enable capital and market forces, to improve infrastructure facilities, to back up political and state power, to empower users and cultural meaning, and finally to encourage the provision of knowledge and technology.

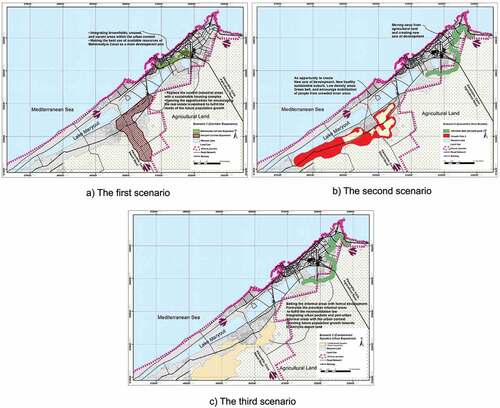

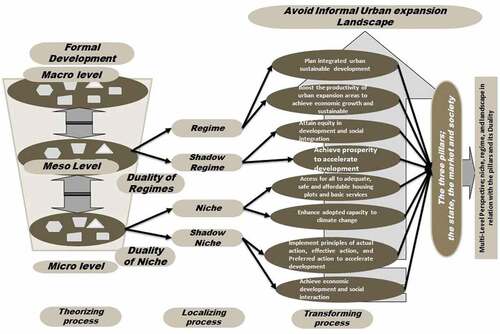

Built on the above planning principles, six criteria have been derived from the empirical part, and literature review, and are used in formulating and evaluating scenarios. Three scenarios are proposed depending on the historical development, literature review of sustainable urban expansion, shortlisted questionaries. The three scenarios that have arrived are: Corridor Expansion, Concentric Core Growth, and Containment Dynamic Urban Expansion. Each scenario will be analysed and evaluated below.

As illustrated in and , three scenarios of urban expansion have been identified to solve Alexandria’s urban problem of future urban expansion until 2032. Future urban expansion should be through various planning modes to meet the requirements of a target population and match the demand and supply of the market forces. These three planning modes briefly describe three themes. A sense of hope determines and makes the best use of the available resources. Another is a sense of desire to rescue the available agricultural land by belting the informal areas with formal development. The third mode is a sense of opportunities to create low-density urban expansion associated with a green corridor. These planning modes are effectively advanced and regulated to cope with the future expansion that codifies the state policy concept of desirable future expansion and welcomes private investment that conforms to the public plan.

Figure 4. Illustrates a sociotechnical perspective of the three scenarios for urban expansion in Alexandria.Source: The authors.

Table 2. Illustrates the three scenario’s policy, reflections, planning mode, objectives, aims, and goals

First, scenario one (corridor expansion) depends on building socio-spatial resilience, relying on sustainable development by integrating the currently available resources of brownfields, unused, and vacant areas into the urban context. This scenario has a sense of hope that determines the available resources and hopes to make the best use of them in accordance with desires to promote or alter urban expansion within the core area of the city where the Alexandrians prefer to live. This scenario aims to allow the opportunity to lock out the vacant areas and brownfields for development to absorb the expected population growth and to minimise travel distance and time for the needed facilities and job opportunities. In this scenario, urban expansion will take place along the Mahmoudeya canal and the Alexandria- Cairo desert road. The replacement of the heavy industrial areas, light industries, and services is relocated to the Al Amriyah district and relies on the Alexandria desert road as the main potential for future urban expansion.

The second scenario (concentric core growth) is a sense of desire based on two main growth poles to prevent excessive loss of agricultural areas; one is in the city’s southern eastern part, which includes peri-urban areas and urban pockets, and the other is in the Al Amriyah district, which serves as a main attractive pole to accommodate the low-income group. The former pole is to restrict the informal areas to formal development by filtrating and making the best use of the urban pockets and peri-urban areas and integrating them with the urban context. The latter will function as a satellite, profiting from the connection between New Borg El Arab and Alexandria’s core urban area. This scenario will adopt a comprehensive policy plan, depending on a balance between demand and supply, which could accelerate socio-economic development by allocating current resources to take advantage of what is available, to enhance rural–urban integration within the city. On top of that, New Borg El Arab will continue its role as a regional growth pole; by connecting it with a direct rail network to Al Ameriyah district and Alexandria city.

The third scenario is a sense of opportunity as an urgent need to direct future urban expansion away from the inner areas. This scenario (Containment Dynamic Urban Expansion) is adopted to meet the urgent needs of climate change. Also, it proposes creating a new axis of development at the local level, linking the southern-western part of the city with the southern-eastern part of the city through new green belt development. It would create opportunities for low-cost land, sustainable and efficient infrastructure, job opportunities, and the required services and facilities to accommodate future population growth. It is argued that (Du et al. Citation2020), a small change in the percentage of unplanned urban expansion can alter the climate, biodiversity, and social inequality, which causes crucial environmental problems that threaten the sustainable development of Alexandria.

As a result, the three scenarios’ main goals are to achieve the global objectives of the SDGs by creating a new healthy, sustainable suburb in the western districts based on the green belt concept with low density −50 people per Fadden- renewable energy generation, and technological innovations. Thus, enabling the urgent adaption to climate change, in addition to the expected population growth and their necessary needs of sustainable urban expansion. Similarly, it aims to use the available desert land in the western sector to achieve the sustainable development transition and to facilitate the provision of services and utilities at a reasonable cost. It also proposes creating a new axis of development at the local level, linking the southern-western part of the city with and the southern-eastern part of the city through new green belt development. It also tries to achieve the goal of encouraging population mobilisation and investment outside of the city. This would be done by creating great opportunities for low-cost land, sustainable and efficient infrastructure, job opportunities, and the required services and facilities. This planning strategy will also protect Alexandria from the El Khamsin wind and play an important role in regulating the climate change in Alexandria.

4.3 Scenarios evaluation

Evaluations of various sites become visible to recognise the maximum access to a given number of new locations. These would fulfill the requirements of urban expansion and meet the stated criteria. It can distinguish between sites that do not provide goods or services because free-market conditions cannot support them, and sites that succeed in providing goods or services because entrepreneurs have recognised the potential for market signals. These methods can be used to select sites among all the locations of the urban expansion or smaller sub-sites within those locations. Moreover, these sites have local access to central places and can function as new hubs, such as strategic places selected using functional integration analysis, which combines various activities as a reflection of mixed land uses. In order to facilitate the future urban expansion of Alexandria, all three pillars should be involved in the development process, backed up by the willingness of the state.

Due to the nature of this study; it is advised to depend on Multi-criteria Evaluation (Lichfìeld and Whitbread Citation1975), which depends on generating planning criteria relating to the stated objectives, aims, and goals. As a result, the best alternative is to be chosen (Voogd Citation1982). This method utilises the above stated criteria which were built upon the collected information derived from the field study. Not to mention, random interviews were carried out by the researchers with specific planning experts. Fortunately, the criteria should satisfy the following thoughts: a) To integrate with the unexpected outcomes while retaining coherence with an overall perspective of the problem, b) To investigate the various challenges as they are verifying the complexity of changes in the city’s peripheries over time -in both socio-economic and physical features- to retrospect and prospect for the urban challenges gathered empirical data, thus avoiding similar problems that might occur in another city while refraining from biased selection of the direction of urban expansion, and to cover all differences and varieties of the development strategies as well.

As explained in the previous section, each criterion will have a certain weight; this weight coincides with its importance and the previous analysis of Alexandria context. Throughout the analysis of Alexandria and its urban challenges; it appears that the most important criteria for the future urban expansion of the city are gathered into six specific criteria . These specified criteria will likely fulfill the immediate and future needs of the population. It has been estimated that the total population of Alexandria will rise from 5.5 to 7.1 million people by the year 2032: at an average density of 150 people/Fadden. Therefore, it is expected that Alexandria City will need 20.000 Fadden to meet the requirements of the population for goods and services until 2032. This future expansion will be divided into two phases: short-term and long-term. The former will meet the immediate needs of the current population for goods and services, while the latter will meet future population growth. To evaluate the best and most practical scenario to be implemented on the ground (see and ), the six criteria are weighted as follows:

Table 3. Illustrates the evaluation of three scenarios against the six criteria

The first criterion is the intuition of the state and its power to enforce development in a certain direction, as it is considered a cornerstone for the sustainable transition development process. Also, the recent development of road networks all over the country and the construction of the fourth generation of new towns are fully supported and encouraged by the state. Therefore, this criterion has the highest weight for the evaluation of the three scenarios −6 out of 6 points-.

The second criterion is capital and market forces, which are the main driving forces for declining or flourishing in the economic situation of a given area. It is asserted that in order to achieve sustainable expansion development, economic development should maximise income, whiles a maintained capital stock has to be achieved (Munasinghe Citation1993). This criterion is as important in weight as the state and power criteria, getting (6 out of 6 points).

The third criterion is related to the infrastructure and the availability of various facilities. To emphasise, the availability of reasonable-standard infrastructure and facilities serves as a magnet for attracting uses, users, and investments (Frantzeskaki et al. Citation2018) counting on recent technologies, a good infrastructure, and on-point services. It is expected that investors and private sectors will flock to locations that have access to such services. On the other hand, it comes as a third category after the willingness of the state and the power of the capital (5 points out of 6).

The fourth criterion is the power of human beings. To elaborate, the role of users is essential to accelerate the development process; as Lefebvre knew well from the history of the Paris Commune, socialism, communism, or anarchism in one city is an impossible proposition, as it happened in Paris in 1871 (Lefebvre Citation1971). However, this does not indicate excluding a fragment of a society, rather than creating a homogenous society capable of driving the development process. In addition, future urban expansion could give a chance to integrate various strata of society into one place and revive traditions among the citizens (it could weigh in at 4 out of 6).

The fifth criterion is the effect of technology on development. The rapid development of technology reflected on communication with society; it made the planet too small and everything reachable and within easy access. The importance of power, society, and communication is essential. Now the question is how these forces can increase or decrease the development processes and their dependence on allocating these three forces, as well as connect them with various strata of society (Castells Citation2010 2nd edition). Strata societies are reviving and sustaining regional communities (Simpson and Hunter Citation2001). This criterion could be rated 4 out of 6.

The sixth criterion is the activities and market. Uses and activities have had a great influence on urban expansion throughout history, as people tend to live near social amenities and various recreation areas. According to Raven et al. (Citation2016) understanding transformation across production and consumption is a top priority for future growth. Thus, the more mixed land uses, the more sustainable the environment, the greater the chance for people’s involvement in the sustainable transition process. It is advised that both the challenges of urban practitioners and scientists, should take up process-content thinking and reflect on how to navigate societal complexity while mobilising innovative and transformative societal potential towards action for sustainability (Frantzeskaki et al. Citation2018). This criterion could be rated 4 points out of 6.

As shown in and , the first scenario appears to meet the requirements for infrastructure, capital, and market forces; however, it does not meet the idol score in the remaining requirements. While the second scenario achieves an intermediate score across the whole criteria. It appears that the third scenario is the most desirable one and scores 33 points out of a total of 36 points, as it meets the objectives of the study for the future urban expansion of Alexandria City. The third scenario is the closest to sustainable urban transition, as it fulfils most of the required criteria except cultural meaning. It has proper linkage and correlation to the levels of the duality of niche, regime, and landscape. It fulfils the six criteria through various pathways. These pathways highlight socio-cognitive aspects of the duality of a regime’s role that shapes socio-technical transitions. Thus, the interactions between the MLP’s various levels are reflected in the enabling milieu and integrated urban management.

illustrates socio-technical transitions through interaction and correlation among the three levels of niche-innovations, regime (a model of a hexagon combining the six criteria), and landscape, reflecting a model of a hexagon combining the six criteria. On the other hand, these three levels are applicable in the Global North. While in the global context, the three levels are dualistic as formal and shadow forms. It could be said that the socio-technical transitions in the Global North are theorising processes, although a localising process with the duality of regime and niche is dominated in the Global South. This dualistic phenomenon has resulted in a transforming process in the cities of the Global South.

Figure 6. Illustrates a sociotechnical perspective of the three scenarios for urban expansion in Alexandria.Source: The authors.

From previous analysis (see and ), it appears that the third scenario is the closest to sustainable urban transition as it fulfils most of the required criteria. It fulfils the six criteria through various pathways; these pathways highlight socio-cognitive aspects of the dual regime’s role, which shapes socio-technical transitions. It also reflects the interactions between various levels of the MLP by enabling milieu and sustainable urban management. The final interaction between the duality of regime and niche of this process is of eight outputs; a) plan integrated urban sustainable development, b) boost the productivity of urban expansion areas to achieve economic growth and sustainability, c) attain equity in development and social integration, d) achieve prosperity to accelerate development, e) access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing plots and basic services, f) enhance adopted capacity to climate change, g) implement principles of actual action, effective action, and h) preferred action to accelerate development, and finally, h) achieve economic development and social interaction.

In each phase of the transition, vertically and/or horizontally, different strategies and instruments -pathways- can be used to create a sustainable urban fabric for the uptake of natural dynamic transitions, such as population growth, production, reproduction, distribution, consumption, capital dynamics, etc. Many pathways are generated to communicate with the three pillars. These pathways are access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable housing plots and basic services; achieving prosperity, attaining equity in development and social integration, improving urban environmental sustainability; and lastly, planning integrated and sustainable human settlements in all parts of Alexandria. It also enhances adaptive capacity to climate change and the protection of natural resources; and boosts the productivity of the city to achieve economic growth and sustainable development at the national and regional levels. These pathways cover a time frame of ten years till 2030 and will be subjected to review every five years. This strategy demonstrates the importance of coordination and integration, as all parts of the city would be a part of the whole.

Besides, national strategies would be interspersed with regional objectives of the city aligned with the 2030 sustainable development agenda. It is hoped that this research will open a new research arena to adjust the planning thoughts for a future urban expansion in Alexandria and elsewhere in cities in the Global South. The future vision would be dedicated to ensuring well-integrated and sustainable human settlements that are resilient, competitive, and capable of providing better living standards in Alexandria City. To achieve a future vision of the new urban expansion, the influence of the three pillars should be considered; this vision should be viewed from multidisciplinary perspectives. The three pillars form the dual regime level, while the challenge of new urban expansion shapes the dual niche level, and the result is the landscape level, which shapes the new urban fabric.

5 Conclusion

It is time to understand the direction of the geographical transitions that will serve as the foundation for meeting the needs of an expanding population and matching the rapid economic transition. Practically, the cooperation between the three pillars (the state, capital, and society) and the interrelation of the geographical transitions within the framework of sustainability transitions are presumed to enhance the continuous sociotechnical and political transitions in Alexandria, Egypt. In theory, if the urban patterns of geographical transitions were reconstructed and the informal urbanisation process was guided, the Egyptian built environment would be improved sustainably while still fulfiling official planning standards.

Moving beyond the ‘niche–regime dichotomy’; this study elaborates on how innovative practices and vested interests are typically constituted in a dualistic manner and tend to incite processes of change in both. Therefore, niche versus shadow niche, regime versus shadow regime are all operating in parallel for development. As a result, the duality phenomenon in the Global South is missing from transition studies and should be taken into account when evaluating future urban transitions.

On a side note, many pathways are generated to communicate with the three pillars. These pathways gained access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable housing plots and basic services, achieved prosperity; attained equity in development and social integration; improved urban environmental sustainability; integrated planning; and sustainable human settlements in all parts of Alexandria. Moreover, it enhances adaptive capacity to climate change and the protection of natural resources, boosting the productivity of the city to achieve economic growth and sustainable development at the national and regional levels. Furthermore, national policies would be united with the city’s regional objectives, in accordance with the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda.

It seems that recurring calls for increased attention to the geographical transitions in the Global North were based on the stability and steady of socioeconomic and political situations that seemed to be consolidated remain relatively healthy development. On the contrary, the opposite is applicable in the Global South; in which most countries are lacking in systematic development. This is due to the phenomenon of duality that characterises these countries, such as formal versus informal economies, formal versus informal urbanisation, exclusion versus inclusion, and so on. Researchers and practitioners in urban transitions are particularly interested in recasting capitalism and societal challenges as opportunities for innovation. On this track, this study explores recent advances in the broader field of sustainability-oriented expansion innovation as well as the subthemes of circular and green technology innovation. It is eager to comprehend these innovation directions at the level of products, product-service systems, and capitalism models. It is particularly interested in developing a deeper knowledge of the innovation processes, ecosystems, and entrepreneurial activities that support these innovative outputs.

Concisely, the study discusses and synthesises the insights of the duality across the three generating scenarios, each touching on one dimension of politics: the materiality of transition politics, the dispersed nature of agency and power, the importance of historical and spatial contexts, and the influence of society in the geographical transitions. Finally, it points out the main insights and answers the research questions in a concluding synthesis. Last but not least, the research interrogates how organisational practices link into, if not impact, broader sustainability transitions. Therefore, the research questions the urban expansion related to the duality phenomenon of the cities in the Global South. Hence, this disciplinary duality reflects the wide-ranging and multi-dimensional nature of transitions, anchored in the concept of politics as typified by many scholars in the North. This research hopes to pave the way for a new research arena that will diversify planning thoughts for a future geographical transformation in Alexandria and other cities in the Global South.

Acknowledgement

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Taylor & Francis has been quite kind in covering the publishing expenses for this work, which we much appreciate. The authors wish to acknowledge Prof. Ramin Keivani, the editor of the International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, for his constructive comments and support on various drafts of this paper. The two anonymous reviewers’ comments were helpful for improving the paper, for whom we appreciate their valuable efforts and their constructive feedback during the review process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed M. Soliman

Ahmed Soliman received his Ph.D. in Social Sciences – Urban Planning and Housing studies from the University of Liverpool, UK from 1981 to 1985. He is currently working as a professor of urban planning and housing Studies and was a former Chairman of Architecture Department in the Faculty of Engineering at Alexandria University (2007-2012), Egypt. He was the Dean of the Faculty of Architectural Engineering at Beirut Arab University, Lebanon from 2000 until 2004. He has published widely on issues of urban planning, urban housing, and informal settlements in several distinguish international journals and contributed in chapters in various books. He worked with Hernando De Soto twice, the first time was in 1997 and the second time was in 2000, studying the informal settlements in Egypt. Soliman is a chair of the academic scientific committee for evaluating the work of academic staff in Egyptian Universities for the qualification to a higher post at the Egyptian Universities. He is the author of A Possible Way Out: Formalizing Housing Informality in Egyptian Cities (2004), University Press of America, USA. His recent publication is “Urban Informality: Experiences and Sustainability Transitions in Middle East Cities”, 2021, Springer Nature.

Yahya A. Soliman

Yahya Soliman obtained his B.A from Architectural Department, Faculty of Engineering, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt. He also awarded his M.Sc. from the same institution in 2020. He has worked as a Teaching Assistant, Architectural Department, Faculty of Engineering, Pharos University, Alexandria. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate Design and Urban Planning Department, Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. He also participated in international conference IST 2020 with paper titled “Urban Sustainability Transitions on new urban expansion Alexandria, Egypt”. Moreover, by 2022 he participated Ecocity World summit 2022 with paper under name of “Platform Urbanism: New administrative Capital City Cairo Egypt”.

Notes

1. One feddan equals 0.42 hectare

2. A part of the planning process is concerned with the formulation of aims and goals and then their translation into more specific objectives, which might be termed plan objectives (derived from policy aims and goals) (Chadwick Citation1978). The terms ‘aim’, ‘goal’, and ‘objective’ are often confused, but the simplest way to explain it would be that you aim to accomplish a goal so that you can reach your objective. To reach this objective, the planner needs to analyse the existing condition of a certain problem by assembling and analysing the information that can be obtained from different sources, such as the actual spatial situation. This could be called the analysis process. In the analysis process as applied in this study, special attention is given to the dynamic character of new urban expansion, and, in particular, to the development of techniques that could be used for collecting information, analysing and monitoring the problem.

References

- Abu Hatab A, Cavinato M, Lindemer A, Lagerkvist CJ. 2019. Urban sprawl, food security and agricultural systems in developing countries: a systematic review of the literature. Cities. 94:129–142. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.06.001.

- Aisen A, Jose F. 2013. How does political instability affect economic growth? Eur J Polit Econ. 29:151–167. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2012.11.001.

- Arimah B. 2016. Infrastructure as a catalyst for the prosperity of African cities. Procedia Eng. 198:245–266. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.07.159.

- Arts B, Van Tatenhove J. 2004. Policy and power. A conceptual framework between the ”oldß and ”newß policy idioms. Policy Sci. 37(3–4):339–356. doi:10.1007/s11077-005-0156-9.

- Avelino F, Grin J, Jhagroe S, Pell B. 2016. Beyond deconstruction, a reconstructive perspective on sustainability transitions governance. Environ Innov Soc Transit. 22:15–25. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2016.07.003.

- CAPMAS. 2016. General statistics for population and housing: population census. Cairo:Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics.

- CAPMAS. 2022. General statistics for population and housing: population census. Cairo:Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics.

- Castells M. 2010. The rise of the network society. 2nd ed. West Sussex (UK): John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Chadwick G. 1978. A system view of planning: towards a theory of the urban and regional planning process. Oxford: Pergamon Press Ltd., Headington Hill Hail.

- De Soto H. 1989. The other path: the invisible revolution in the third world. London: I.B. Taurus.

- De Soto H. 2000. The mystery of capital: why capitalism Triumphs in The West and Fails Everywhere Else. London: Blaack Swan.

- Dix G. B. 1986. Alexandria 2005: Planning for the future of an historic city. Ekistics, 53(318/319), 177–186. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43621977

- Dixon T, Malcolm E, Miriam H, Simon Charles L. 2014. Introduction. In: Urban Retrofitting for Sustainability Mapping the transition to 2050. Abingdon (Oxon, UK): Routledge; p. 1–16.

- Du M, Xiaoling Z, Wang Y, Tao L, Li H. 2020. An operationalizing model for measuring urban resilience on land expansion. Habitat Int. 102:102–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102206

- Durand-lasserve A. 2005. Land for housing the poor in African cities: are neo-customary processes an effective alternative to formal systems? In: N. Hamdi, editor. Urban futures, economic growth and poverty reduction. London: ITDG Publishing; p. 114-134. doi:10.3362/9781780446325.012.

- Frantzeskaki N, Katharina H€olscher K, Wittmayer J, Avelino F, Bach M. 2018. Transition Management in and for Cities: Introducing a New Governance Approach to Address Urban Challenges. In: N. Frantzeskaki et al. Editors. Co-creating sustainable urban future: a primer on applying transition management in cities. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; p. 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69273-9_1

- Geels FW. 2014. Regime resistance against low-carbon transitions: introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective Theory. Culture Soc. 31(5):21–40. doi:10.1177/0263276414531627.

- Geels FW, Hekkert MP, Jacobsson S. 2008. The dynamics of sustainable innovation journeys. Technol Anal Strateg Manage. 20(5):521–536. doi:10.1080/09537320802292982.

- Geels F, Schot J. 2007. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res Policy. 36:399–417. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003.

- Geels F, Schot J. 2010. The dynamics of socio-technical transitions: a sociotechnical perspective. In: Grin JR, editor. Transitions to sustainable development; new directions in the study of long term transformative change. New York: Routledge; p. 11–93.

- GOPP. 2015. General strategic urban plan Alexandria 2032. Cairo:GOPP.

- Grin J, Rotmans J, Schot J; in collaboration with Frank Geels and Derk Loorbach. 2010. Transitions to sustainable development: new directions in the study of long-term transformative change. New York: Routledge.

- Grin J, Loeber A. 2007. Theories of learning. Agency, structure and change. In: Fischer GJF, editor. Handbook of public policy analysis. Theory, politics, and methods. New York: CRC Press; p. 201–222.

- Hoffman J. 2013. Theorising power in transition studies: the role creativity in novel practices in structural change. Policy Sci. 46(3):257–275. doi:10.1007/s11077-013-9173-2.

- Kanger L, Schot J. 2018. Deep transitions: theorizing the long-term patterns of socio technical cahnge. Environ Innov Soc Transit. 10.1016/j.eist.2018.07.006

- Keivani R, Shirazi M. 2019. Urban social sustainability: theory, policy and practice. New York & Abingdon (UK): Routledge.

- Khalifa MA. 2015. Evolution of informal settlements upgrading strategies in Egypt: from negligence to participatory development. Ain Shams Eng J. 6(4):1151–1159. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2015.04.008.

- Koehler J, Geels FW, Kern F, Onsongo E, Wieczorek AJ. 2017. A research agenda for the Sustainability Transitions Research Network, STRN Working Group. STRN. https://pure.tue.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/101288346/STRN_Research_Agenda_2017.pdf

- Köhler J, Geels FW, Kern F, Markard J, Wieczorek A, Alkemade F, Avelino F, Bergek A, Boons F, Fünfschilling L, et al. 2019. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: state of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004

- LaFreniere G. 2007. The decline of nature: environmental history and the western worldview. Bethesda (Dublin & London): Academica Press.

- Lamba H. 2010. Understanding the ideological roots of our global crises: a pre-requisite for radical change. Futures. 42(10):1079–1087. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2010.08.007.

- Lefebvre H. 1971. Everyday life in the modern world. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers.

- Leftwich A. 2010. Redefining politics. People, resources and power. New York (NY): Routledge.

- Lichfìeld NK, Whitbread M. 1975. Evaluation in the planning process. Oxford: Pergamon Press Ltd., Headington Hill Hall.

- Maconachie R. 2007. Urban growth and land degradation in developing cities: change and challenges in Kano, Nigeria. Hampshire (England): Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Markard JR, Truffer B, Truffer B. 2012. Sustainability transitions: an emerging field of research and its prospects. Res Policy. 41(6):955–967. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013.

- McAuslan P. 2013. Land Law Reform in Eastern Africa, traditional or transformative?: a critical review of 50 years of land law reform in Eastern Africa,1961–2011. Oxon (UK): Routledge.

- Mguni P. 2015. Sustainability transitions in the developing world: exploring the potential for integrating sustainable urban drainage systems in Sub-Saharan cities. Copenhagen: PhD submitted to University of Copenhagen.

- Moore J. 2015. London. Capitalism in the web of life: ecology and the accumulation of capital. London: Verso Books.

- Munasinghe M. 1993. Environmental economics and sustainable development. Washington: The World Bank.

- Nada M, Sims D. 2021. Assessment of land governance in Egypt. Cairo: World Bank.

- Nassar D. 2016. Heritage conservation management in Egypt the balance between heritage conservation and real-estate development in Alexandria environment-behaviour proceeding journal. Environ Behav Proceeding J. 1(4):95. NA. doi:10.21834/e-bpj.v1i4.132.