?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The city centres of South African cities are in the process of degeneration and need transformation. The study assessed the current scenario of the various physical, spatial, and socio-economic attributes of central areas of three South African cities and explored how they can be transformed into great places. The challenges related to physical and visual elements, liveability, social and cultural elements, productivity and sustainability, and human experience and richness were identified. Three important strategies that include community participation is likely to change perceptions and enhance belongingness and ownership, the integration of ICT and the revitalisation of public artefacts and places including cultural and tourist elements and enhancement of accessibility are found to be essential for the revitalisation of the city centres, enhancement of economic activities and vibrancy. Therefore, it is theorised that a combination of these strategies could transform the degenerating city centres into great places.

1. Introduction

Central areas are of vital importance for cities across the world. They offer services to surrounding areas that include commercial, recreational, educational and administrative services (Jones and Livingstone Citation2018; Alexander et al. Citation2019). Moreover, they have the potential for housing diverse architectural and urban morphologies within a compacted framework that allows diversity, neighbourhood interaction, and communication (Das Citation2021; L Corbusier Citation1958, p. 210; Powe and Hart Citation2008; Steyn Citation2012). According to Lynch (Citation1960), the images of cities generally emanate from the image and vitality of their central areas. Further according to Le Corbusier, the central areas constitute richly varied refined vistas and multitudes of different kinds of buildings organised asymmetrically to generate a powerful rhythm. The entire structure is enormous, adaptable, active, sharp, intense and dominant (L Corbusier Citation1927, p. 43). Such a concept is largely observed in the cities in the Global North. These areas are often referred to as Central Business Districts (CBDs), inner cities or downtowns. From the functional perspective, while these places might not be much different in the context of the Global South, they might differ in scale, level of activities and culture. In other words, the sociocultural, economic and political dynamics are different (Lehmann Citation2010; Hansen et al. Citation2018). Consequently, the approaches for their (re)development and sustainability are argued to be different (Hansen et al. Citation2018)

Concerted and conscious efforts are always made to design, redesign, and (re)develop the central areas according to the future visions and sustainable goals of the cities. However, the challenge of redesigning and redeveloping city centres is enormous. Several approaches have been adopted in many cities across the Global South to arrest the decay and enhance the vitality of the city centres. These approaches range from the focused area-based approach (Donaldson and Du Plessis Citation2013), urban renewal programmes promoted by government agencies to gentrification, and redevelopment sphere headed by private sectors for enhanced economic activities, increase in real estate and land values, and intensification of commercial activities (Cobbinah et al. Citation2019). Further, a multidimensional approach encompassing human dimensions, social cohesion, solidarities, supporting national heritage, and recognising and use of indigenous knowledge systems has also been advocated (Parnell, Pieterse, Watson, Citation2009). However, such efforts although observed to have brought some level of development or improved the physical built environment to a certain extent, are found to be isolated efforts and thus the long-term sustainability and transformation to become great places remained as challenges. Furthermore, the city centres in many developing countries are facing competition from forces such as decentralised retail and service agglomerations and new developments (Visser and Kotze Citation2008; Jones and Livingstone Citation2018; Alexander et al. Citation2019) and losing their vitality and importance (Powe and Hart Citation2008; Wrigley and Lambiri Citation2014).

The central areas are integral parts of South African cities. Each large and medium city in the country has a designated central area – the Central Business District (CBD). They were once the nerve centres of the cities having historical, cultural and economic importance. Typically, these areas have mixed land use and constitute functions such as administrative, commercial, residential and other service-oriented activities. However, in recent years, they are losing out to decentralised forces such as the creation of shopping complexes/ malls in suburbs, new commercial and administrative area developments, online marketing systems, etc., similar to other developing countries (Jones and Livingstone Citation2018; Alexander et al. Citation2019). Concurrently, the central areas are observed to be degenerating and do not command the same significance as before (Das Citation2016, Citation2021). The degeneration of the central areas raises questions as to why such degeneration occurs and how these central areas can be revitalised.

In South Africa, Spatial Development Frameworks (SDF) form the base for the sustainable development of cities. Social integration (desegregation) and environmental considerations are a central focus of SDFs (Todes Citation2011), leading to urban redevelopment projects in the central areas of some South African cities. Certain efforts have been made to redevelop the central areas of some cities, for example, Johannesburg, and Cape Town (Didier et al. Citation2012). An approach of Central City Improvement District (CID) in Cape Town and Johannesburg, as a micro local tool of urban management, was argued to enable enhancement of the built environment as well as could able to meet the demands to enhance economic activities (Lipietz Citation2008; Didier et al. Citation2012). Similarly, the gentrification of the central areas of these major cities and area-based management approaches for the CBDs of Townships (small towns around the major cities), for example, the Khayelitsha CBD (a small town about 20 Kilometres south-east of Cape Town CBD) are some of the other major planning approaches also undertaken with varied outcomes (Visser and Kotze Citation2008; Donaldson and Du Plessis Citation2013). However, each of these approaches has its limitations. Gentrification, despite its advantages of linking micro-level manifestations (neighbourhood change, consumption pattern change, etc.,) with macro-level transformations (deindustrialisation, globalisation, etc.,) is also linked to the displacement of lower-income households and economic activities with higher-income households and economic activities. For example, housing for the low-income category or disadvantaged groups is displaced to accommodate higher real estate and commercial activities perpetuated by unchecked private sectors (Cobbinah et al. Citation2019; Wilhelmsson et al. Citation2022). Moreover, it is also strongly associated with class, race, and gender and the underlying process of inclusion and exclusions thus might have challenges to social inclusivity (Visser and Kotze Citation2008). Similarly, area-based programmes and spatial innervations could be isolated sectoral activities and they should be undertaken in combination with economic development, poverty alleviation and reduction of environmental challenges (Donaldson and Du Plessis Citation2013). However, very limited studies have been conducted on the attributes that make city centres functional change, and on strategic interventions for their transformation into great places. Consequently, the urban renewal works conducted are found to be fragmented and their effects are limited.

Further, although advanced Information Communication Technology (ICT) has become a part of the daily life of people, its integration into city life and consequent behavioural and functional changes among people seems not to feature in the renewal and redevelopment of city centres. However, international evidence suggests that ICT has made significant impacts on the functions of city centres, the way people use various elements of the city centres and image building (Das Citation2016). Thus, ICT is expected to influence the city centres and their elements both spatially and functionally (Alghamdi and Al-Harigi Citation2015; Das Citation2016, Citation2021). Such aspects need to be integral parts of the redevelopment and revitalisation of city centres (Das Citation2021).

Therefore, using the city centres of three South African cities, Bloemfontein, Port Elizabeth and Pretoria, this study assessed the current scenario of the city centres and explored opportunities and challenges that need intervention. Grounded on place theory, strategic options were explored that can assist in turning them into great places. In this context, the following research questions were investigated:

What are the spatial and socio-economic factors that influence the vitality of the city centres and what is their current status?

What critical challenges need interventions and what vital opportunities need augmentation to revitalise the city centre?

What strategic interventions could become pivotal in making the city centres great places?

Furthermore, specifically, a theoretical argument that how the integration of ICT in conjunction with socio-political transformation in decision-making and implementation premised upon place theory can engender the revitalisation of these city centres was proffered.

2. Study context cities

Three important cities of South Africa such as Bloemfontein, Pretoria and Port Elizabeth were selected as the case study cities because they have designated central areas (CBDs), portray distinct images and have regional and national importance. While there is physical and structural homogeneity, they also represent functional and geographical heterogony. They are located in three separate regions: Pretoria in the North, Port Elizabeth in the South East and Bloemfontein at the centre providing heterogeneous geographical representation. Each of the cities has a designated CBD that performs several urban functions and has its image. These central areas are predominately mixed land use, with functions including trade and commerce, administration, transportation, culture and recreation. The historic, tourist and architectural elements in these spaces offer functional and structural homogeneity. Therefore, these cities were considered ideal candidates for this investigation.

2.1 Pretoria

Pretoria, situated in the northern part of Gauteng province, houses the administrative branch of the national government. The CBD contains corporate offices, banks, shopping centres, roadside shops and government departments. The skyline of the city centre includes both skyscrapers (up to 150 m tall) and low-rise buildings. Several buildings, monuments and museums of major historical significance are located in the area. Despite being the seat of the National Governance and having high-level administrative, and commercial activities and a number of tourist elements, the CBD portrays a very mixed image. While it provides evidence of upscale development, it also offers an image of a poor, unsafe, non-inviting and congested area.

2.2 Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein is a growing medium-sized metropolitan city and is the capital of the Free State province. It has historical importance as the birthplace of the African National Congress (ANC). The city has grown around the CBD. The CBD is the most important administrative and commercial hub of the central region of the country and includes historical monuments and buildings, and tourist elements. With the repeal of the Group Areas Act, changes in spatial, economic, social and political dynamics occurred, leading to a high level of desegregation and spatial infilling in the CBD after 1994. It has transformed from a traditionally white CBD to a cosmopolitan downtown.

However, in recent years it has been seen that several important economic and service activities relocated from the CBD to the suburbs of the city, as a result of the transportation challenges the CBD has during the peak hours as well as the decline of the built environment. The shift in development has engendered the decline of the CBD, with declining infrastructure and services. The area is increasingly regarded as unsafe, with increasing criminality, despite the recent renewal at the centre of the CBD.

2.3 Port Elizabeth

Port Elizabeth is a major coastal city in the Eastern Cape Province and one of the most industrialised cities in the country. The CBD constitutes major commercial and administrative functions and serves the surrounding suburbs and towns, as well as a holiday destination. Many tourist destinations are located in the city centre. Despite the various resources, the CBD is degenerating and infested with criminal activities.

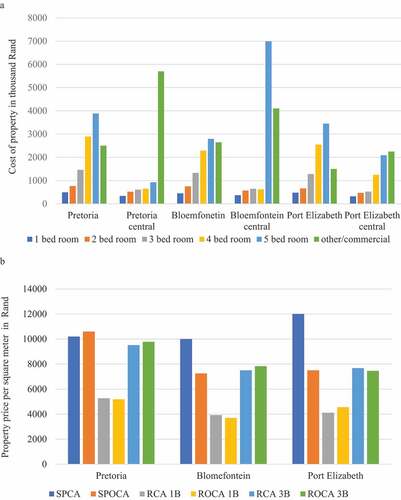

Furthermore, an analysis of the real estate scenarios of the above three cities suggested that the selling price and rental price of the building per square metre are almost similar in both central areas and areas outside central areas in all three cities. Although the unit selling price of commercial areas and large residential buildings are high in the central areas, the unit selling price of one to four-bed residential properties is significantly lower in the central areas compared to the other areas of these cities (). It indicates that there is not much demand for residential properties and the commercial properties do not have any distinct leverage in the central areas. Therefore, the central areas of the three cities appear to be on the wane.

Figure 1. (a) Real Estate prices in the three cities (Cost of property). (b) Real Estate prices in the three cities (property price per square metre) (SP = Selling price, R = Rental, CA = Central area, OCA = Other than central area, B = Bedrooms).

Since most of the CBDs of the country have similar characteristics to the CBDs of these three cities, these cities become ideal candidates for this investigation.

3 Perspectives of central areas as great places

3.1 Concept of place and place-making: a place theory perspective

The concept of place emanated through the humanistic school of thought in geography. ‘Place’ has three parts, physical setting, material form, and investment with sense (Gieryn Citation2000). It is about human-world relations through experience (Pred Citation1984; Laua and Lib Citation2019). In other words, a place is not simply what is seen on the land, a setting, or a location for human activities, rather it is what functions and contributions it makes to history, culture, society and economy by use of a physical setting. According to Pred (Citation1984, p. 279), a place is defined by what takes place ceaselessly, and what contributes to history in a specific context through the creation and utilisation of a physical setting. Relph (Citation2016) added technological changes, which fundamentally impact the attributes of a place including the experience. Delineating the features that lead to the uniqueness of a place or a great place with a distinguishing identity is challenging. However, a great place may shape not only by tangible aspects but intangible features such as distinctive experiences (Corsane et al. Citation2009; Laua and Lib Citation2019).

Placemaking initially was defined as the creation/ upliftment of a social setting through physical intervention (Strydom et al. Citation2018) that incorporates the intrinsic value associated with the setting, thus transforming it into a great place (Laua and Lib Citation2019). However, a move towards placemaking as an instrument for empowerment and community practice is noticed in spatial development planning in recent years (Al-Kodmany and Ali Citation2012; Strydom et al. Citation2018). To develop great places, according to place theory, intangible experiences such as people’s perceptions, feelings about the place and community involvement should inform placemaking, along with such tangible aspects as spatial, environmental and aesthetic features (Laua and Lib Citation2019).

3.2 Great places

The greatness of a place or city entails its magnificence, eminence and unique image (Citation1960; Vanolo Citation2008; Savitch Citation2010). Significant elements include economic and commercial competence, cultural assets, an appealing environment, tourist attractions, and unequalled propositions of philosophy, history and religion (Sassen Citation1991; Savitch Citation2010; Little Citation2013). According to Lynch (Citation1960), the greatness of a place is achieved not by luck but by an unswerving design that creates a unique value to the atmosphere.

Further, urban scholars advocated that one of the novel ways to create and develop public spaces is by putting people and communities ahead of efficacy and aesthetics (Almeida and Fumega Citation2012; Silberberg et al. Citation2013; Hemani and Das Citation2016; Goldsmith Citation2019). They argued for the community-centred urban planning principles that were overlooked during periods of rapid industrialisation, suburbanisation, and urban regeneration (Silberberg et al. Citation2013; Goldsmith Citation2019).

3.3 Central areas as great places

Central areas are compact civic spaces that accommodate diverse built environments and architecture and facilitate societal communication and neighbourhood interaction (Le Corbusier Citation1958, p. 210; Steyn Citation2012). Central areas could be of different sizes with functional hierarchies and deal with specific types of goods and services that attract people. Similarly, they perform civic and entertainment functions, including educational, administrative, service, entertainment, leisure, etc., at different hierarchical levels (Das Citation2021; L Corbusier Citation1958, p. 210; McDonald and Swinney Citation2019; McGough and Thomas Citation2014; Silberberg et al. Citation2013; Steyn Citation2012).

According to Jencks (Citation2000, p. 326), central areas are great places built to look like works of art. However, essentially, they develop through piecemeal growth as a response to a myriad of socioeconomic demands and decisions (Badenhorst Citation2016). Moreover, creating central areas has aimed to enhance the quality of a public place and the lives of its people. In recent years, larger concerns such as healthy living, social justice, community empowerment and economic vitality have been included (Ardill and de Oliveira; McGough and Thomas Citation2014; Badenhorst Citation2016; McDonald and Swinney Citation2019). In other words, central areas seek to improve the interaction of the public space with people, engender attractiveness and joy, link neighbourhoods, raise social justice, catalyse economic growth, promote environmental sustainability, and foster an authentic sense of place (Silberberg et al. Citation2013; Badenhorst Citation2016).

Furthermore, although the dimensions of creative cities (Florida Citation2002, Citation2005) and global cities (Sassen Citation1991) apply to city development at the macro level, they have definite implications at the micro-level such as in the central areas. According to Florida, a better-quality environment, infrastructure and services, in other words, the quality of place, attract the creative class and influences the location decisions of related industries and businesses (Florida Citation2002, Citation2005, p. 33; McDonald and Swinney Citation2019). According to Sassen (Citation1991), global processes are constituted in the urban economy and urban space (Little Citation2013). However, while such places bring economic opportunities and develop interlinkages among the socio-economic condition, production, consumption and lifestyles of the residents, tensions might arise concerning economic equity among the different social classes, leading to conflicts over various aspects such as access to and cost of land for housing, infrastructure, services and public civic spaces (Sassen Citation1996). So, the central areas should thus be places that are inclusive and diverse.

Also, arguments have emerged that central areas are socio-economically valued areas. The maximisation of exchange values of the land and the functions developed over this land govern their development (McGough and Thomas Citation2014; McDonald and Swinney Citation2019). Urban functions that offer higher economic returns get precedence to be located in these areas (Harvey Citation2006; Smith and Floyd Citation2013; Das Citation2021).

Moreover, according to Castells (Citation1996), technology such as ICT plays a vital role and influences both the agglomerations and the dispersion of various central functions (Pratt Citation2008; Alghamdi and Al-Harigi Citation2015). At the micro-level of the central areas, the image of locating global economic activities with the existence of both agglomeration and dispersion and socio-economic diversity would enable the development of a great place (Sassen Citation1996; Little Citation2013; McGough and Thomas Citation2014; McDonald and Swinney Citation2019). Thus, distinct images serve to attract large-scale economic activities, availability of quality infrastructure and services, socio-economic and cultural diversity, and a quality environment.

While such attributes as physical, spatial, socio-economic cultural and technological are necessary to bring a city into the ascendancy, community participation and people-centric urban planning principles should also be used (Almeida and Fumega Citation2012; Silberberg et al. Citation2013; Hemani and Das Citation2016; Goldsmith Citation2019). However, the lack of such positive attributes, the presence of degenerating attributes and the lack of belongingness and acceptance of people could send the places on the path towards degeneration.

In the context of the Global South, an appropriate approach for developing central areas becomes more critical because of the various sociocultural endowments and economic limitations (Lehmann Citation2010; Hansen et al. Citation2018; Larbi et al. Citation2022). Therefore, central areas need a dynamic balance between spatial, economic, social and environmental attributes (Silberberg et al. Citation2013; Goldsmith Citation2019). Overall, the creation of a central area is premised upon accommodating important socio-economic, governance and entertaining functions on a competing basis to bring apposite economic yields (McGough and Thomas Citation2014; McDonald and Swinney Citation2019). According to Savitch (Citation2010), it also should have the attributes of currency, cosmopolitanism, concentration and charisma. In other words, a central area should be elegant, grand, atheistically appealing, safe and socially and culturally acceptable and environmentally sustainable. Moreover, the community should be involved in its creation and management and it should cater to their feelings and experiences (Almeida and Fumega Citation2012; Ardill and de Oliveira Citation2018), to make it a great place.

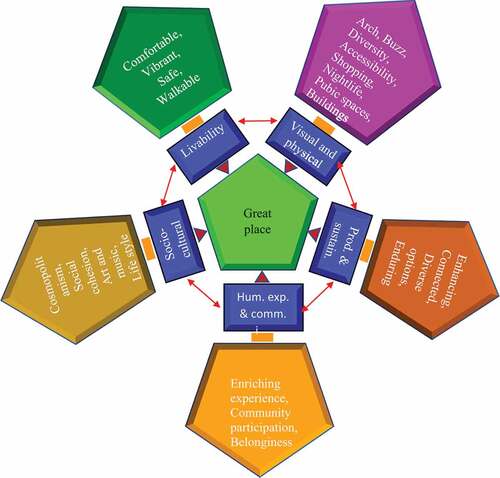

Based on these premises, a central place as a great place can be conceptualised by using various attributes under five aspects such as visual and physical, liveability, socio-cultural, productivity and sustainability, and human experience and community involvement (Vanolo Citation2008; Gehl Citation2016) as shown in . Moreover, ICT can play the central role of a facilitating agent and catalyst for enhancing the various attributes of these above-mentioned five aspects.

4 Research methods

A quantitative research method constituting a questionnaire survey among the stakeholders of the central areas and discussions among the experts by using Delphi techniques were used to conduct the study. The data was collected during the period between October 2017-December 2018. Data collected from the survey were analysed by use of inferential statistical methods including the Dimension reduction method linked to factor analyses and Ordinal regression model estimation to examine the current status of various attributes of the central areas and to explore strategic interventions to transform them into great places.

4.1 Data collection

4.1.1 Stakeholders perception survey

Since systematic and structured statistical data were not adequately available on the attributes of the city centres with different organisations at the city levels such as the metropolitan municipalities, tourism departments, museums or archives, etc., it was pertinent to collect first-hand information to obtain perceptions through conducting a survey among the different stakeholders. So, first, a perception survey was conducted among the various stakeholders linked to the central areas. These included people employed or engaged in the various activities in such areas, local visitors from the other parts of the city, residents in the central areas and tourists. The respondents were chosen randomly based on their willingness to take part in the survey. Care was taken to remove skewness towards one group of respondents, through equitable distribution of the questionnaires among different categories, including gender, race and age. A total number of 910 respondents were surveyed with sample sizes in each city varying between 260 and 350. However, 840 responses (242 from Bloemfontein, 287 for Pretoria and 311 from Port Elizabeth) were returned with a response rate of 92.3%. The sample size was deemed adequate for the population size of the cities with a confidence level of 95% at a confidence interval between 5.56% and 6.3%, at the worst-case percentage of 50%. Such confidence interval was adopted because of the broader nature of the survey (perceptions) and the limitations of the availability of respondents (Delice Citation2010; Creswell and Creswell Citation2017). However, the overall sample size is adequate (>384) at a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 5%. The sample constitutes more than 89.8% of local residents and 10.2% of tourists. Also, of the total respondents surveyed, 10.7% were senior people (≥61 years), 29.5% were from 41–60 years, 32.7% belonged to 25–40 years, and 27.1% were from the 18–24 years age group. Moreover, 60.6% of the respondents were male and 39.4% were female. The demographic mix of the respondents shows a relatively reasonable distribution. The survey was conducted with a pre-tested questionnaire. The questions in the survey questionnaire included respondents’ perceptions concerning the current status of the different attributes and their influence on transforming the central areas into great places. The questions were framed based on the importance of various attributes of central areas (mentioned in ) obtained from the literature. However, isolated interventions, for example, gentrification or area-based approaches, have not been taken as independent factors separately as many of the characteristics of these processes are embedded in the factors considered in this study.

The interviews were conducted through semi-structured direct interviews. Before the interview, respondents were briefed about the meaning of the aspects and attributes used to evaluate the status of the city centres in terms of the opportunities and challenges to become great places.

The perceptions of the stakeholders were collected by the use of a five-point Likert scale with the pointers ranging from highly unacceptable to exceedingly acceptable (1- highly unacceptable, 2- unacceptable. 3- fairly acceptable, 4- highly acceptable and 5- most acceptable) (Li Citation2013; Peeters Citation2015). While collecting data all ethical protocols were adhered to and non-maleficence was observed throughout the study.

4.1.2 Expert discussion by using the Delphi technique

Discussions using the Delphi technique were conducted with 31 experts and professionals to understand the various strategies and policy interventions that would be vital to transforming the central areas into great places (Liggett et al. Citation2011). Delphi uses a group of experts in the related fields, a structured group communication process that enables a group of individuals, to deal with a complex problem effectually (Hsu and Sandford Citation2007). In this process, experts’ views are gathered anonymously by use of a questionnaire and analysed, and a new questionnaire that contains the results of the analyses of the initial information obtained is sent back to the experts to allow them to change their opinion if they think right (controlled feedback). The process works in an iterative manner of two to three rounds (Pulido-Fernández, López-Sánchez and Pulido-Fernández Citation2013). Since this study was explorative and explored plausible strategies and policy options, this technique was considered suitable.

The expert group used for this study included urban planning and design professionals (4), architects (3), civil engineers (4), academicians from the field of architecture and urban planning (6), urban development executives (officers in charge of implementation) (3), entrepreneurs (4), people engaged in image building and branding (2), sociologists (2) and ICT experts (3). The experts were selected based on their relevant expertise and experience. For example, of the four urban and planning and design professionals, two are at the senior level, one each from the middle executive and junior executive level. The discussions were made in two rounds, but, after the first round, five (one urban planning professional, one architect, one academician, one civil engineer and one entrepreneur) opted out. The sample size and diversity of expertise were found to be acceptable (Sobaih, Ritchie and Jones Citation2012; Lin and Song Citation2015). The focus of the survey was on strategies and policy interventions needed to make these central areas great places, including plausible strategic options to improve the physical and spatial character of the areas, such as integration of ICT in various activities, image creation and branding, as community engagement and improve the human experience, etc. As mentioned earlier, the expert discussions were made in two rounds (Lin et al. Citation2014; Song et al. Citation2013). In the first round, the experts were asked to provide a set of plausible strategies and reasons thereof that could assist in transforming the central areas into great places. After the first round, a set of the most preferred strategies were compiled. In the second round, the experts were asked to rank the compiled strategies based on their plausible influence on the transformation of central areas. A five-point Likert scale was also used for their perceptions of the strategic options, with the pointers indicating: 1-not suitable, 2-less suitable, 3-fairly suitable, 4- highly suitable and 5- most suitable. The experts and responses were kept anonymous, to evade any individual and mutual prejudices and biases (Lin et al. Citation2014; Song et al. Citation2013).

4.2 Data analysis

A quantitative approach was used for data analyses. Relevant descriptive, inferential statistical methods and the Ordinal regression model were used for quantitative analysis. The perceptions data gathered from the stakeholders’ questionnaire survey was first checked for reliability, consistency and normality of the data set. Cronbach α test and standard deviation (SD) were done to examine the reliability and consistency of the data. The normality was checked by Kurtosis and Skewness tests. The detailed data analyses and model estimation are discussed in the following sub-sections.

4.2.1 Status and influence of relevant variables in central areas

To examine the current status of the variables and their influence in central areas, Relative Importance Indices (RIIs) for each variable were calculated from the responses received on the Likert scale. The RII is presented in EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) . In addition, a significance test (test) was conducted to check the statistical significance of the perceptions of the stakeholders on the factors that influence central areas (Hsu and Sandford Citation2007; Pulido-Fernández et al. Citation2013).

Where; RII = Relative Importance Index, w = weighting given to each factor (in this study all factors have been given equal weightage), x = Score frequency of ith response to each factor, N = number of respondents for a particular influence factor.

However, before the RIIs were determined, a Communality test was conducted to check the relevancy and importance of variables for transforming the central areas into great places. The total variance in terms of Initial Eigenvalues, Extraction Sums of Squared Loading and Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings were used to observe the number of principal components or major attributes under which the various variables (factors) could be categorised. The dimension reduction method linked to factor analyses was used to determine the communalities and total variance.

Further, from preliminary analyses, it was found that the Kurtosis test values and Skewness values range between −2 and +2 indicating the normality of the data. However, since the data used are in an Ordinal scale, a non-parametric One-Sample Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was conducted to check the statistical significance and reject or retain the null hypothesis that the status of attributes in the central areas is fairly acceptable (at the test value of 3 in Likert scale).

An RII value between 0.6 and 0.79 (on a scale of 0 to 1) or higher was considered fairly acceptable and a value of 0.8 and above was considered highly acceptable. However, RIIs <0.6 were taken as unacceptable. Similarly, a p-value ≤0.05 for α ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4.2.2 Evaluation of strategic measures

Ordinal regression model estimation was made to examine the relative importance or suitability of the various strategic options for the transformation of the city centres into great places. For this purpose, the data collected from the experts on strategic options were used.

The ordinal regression model is a kind of regression model used to predict the behaviour of the ordinal dependent variable (whose values exist on an arbitrary scale) with a set of independent variables. The dependent variable should be the order response category variable (or response variable) and the independent variables (predictor variables) may be categorical or continuous variables. The ordinal regression models are generally used for causal analyses, forecasting an effect and trend forecasting. It focuses on the strength of the relationships between two or more variables and assumes a dependence or causal relationship between one or more independent variables and one dependent variable (Williams and Quiroz Citation2020). In this study, the model was used to examine the strength of the effect of the various strategies on the transformation of the city centres. In other words, the model is used to estimate the influence of various ICT, visual and spatial and social-cultural strategies on the transformation of the city centres. In this case, the various strategies were taken as the predictor variables and the influence of these strategies was considered the dependent variable. Since the data were obtained on an ordinal scale and the relative influence of different strategies was evaluated, this model was found relevant and most suitable.

While developing the model the log-linked ordinal regression model was used. The model is represented by EquationEquation 2(2)

(2) .

Where Pr is the cumulative probability of the response

being at most

is given by a function

the inverse link function) applied to a linear function of

.

The set of observations is represented by p-length vectors

The logistic function is given by EquationEquation 3

(3)

(3) .

Where, are the set of thresholds with

in which k disjoint segments are corresponding to k response levels.

However, before the model estimation results were used, the validity and robustness of the model were checked by Goodness of Fit, Nagelkerke r square (Pseudo r square) and test of parallel lines. IBM SPPS V.27 software was used for data analysis.

5 Results and discussion

The results are presented under three aspects such as (1) the factors that influence the vitality of city centres, (2) the critical challenges and opportunities of the city centres that need redress and (3) plausible strategic interventions which would transform the city centres into great places. The analyses were conducted on an aggregate basis because of the similar nature of the attributes in the central areas. However, before the analyses were made, the reliability and consistency of the responses were verified. The reasonably high Cronbach α values (ranging between 0.704 and 0.856) and low standard (deviation ranging between 0.72 and 0.99) confirmed the reliability and constancy of the responses and therefore can be used for further analysis.

5.1 Exploratory analysis of the factors influencing city centres and their current status

The factors which are observed to be relevant and largely influence the vitality of city centres are presented in . The communalities of the factors ranging from F1 and F25 are found to be significantly high (>0.6). These high communalities indicate that there exists high commonness among the variables and therefore are relevant and likely to influence the vitality of the city centres. Furthermore, the total variance values in terms of Initial Eigenvalues, Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings and Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings indicate that component 1 (25.57%), component 2 (24.08%), component 3 (19.95%), component 4 (9.44%), and component 5 (6.72%) were predominant, resulting in a cumulative variance percentage of 85.35% of the influence on the city centres (). Thus, the influential factors (F1-F25) can be categorised under five principal components or attributes. In alignment with the conceptualisation made in , the five major attributes can be labelled as (1) Visual and physical, (2) Liveability, (3), Social and cultural, (4) Productivity and sustainability and (5) Human experience and community involvement. The status of the factors under each attribute is discussed in the following subsections.

Table 1. Communalities indicating adequacy, relevancy and factorability of the sample.

Table 2. Total variance explained.

5.1.1 Visual and physical

presents the current status of the various factors which influence the vitality of the city centres, which were assessed in terms of RII and significance test results obtained from the perception of respondents. Ten factors (F1-F10) were aligned to the visual and physical attributes of the city centres. The ten factors are found to be statistically significant (p-values ≤0.05 at 95% confidence interval and α < 0.05). This indicates that the status of all the ten factors is either worse or better than the fairly acceptable condition. Out of the ten factors, the quality of buildings in the central areas is found to be highly acceptable (RII = 0.82). Five more factors such as the status of restaurants and dining (RII = 0.67), shopping (RII = 0.71), professional and administrative buildings (RII = 0.75), art, architecture & historical and heritage elements (RII = 0.65), and images of public spaces (for example, parks, congregation places, etc.,) (RII = 0.63) are found to be fairly available. However, accessibility and pedestrianisation (RII = 0.57), buzz (RII = 0.55), diversity (RII = 0.50), and nightlife (PI = 0.45) are the major challenges.

Table 3. Current status and relative importance of variables in the city centres.

Thus, the central areas, although physically and visually appreciable to a certain extent, these areas suffer from challenges concerning poor accessibility, vibrancy, nightlife and moreover inclusion of diversity.

5.1.2 Liveability

Four factors comfortability, safety, vibrancy and walkability (F11-F14) are found to be statistically significant with the central areas as great places. However, the RII values of safety, comfortability, walkability and vibrancy are less than 0.6 (0.58, 0.54, 0.52 and 0.46 respectively). These values indicate that in the current situation the city centres are not considered as safe, comfortable and walkable. Moreover, the city centres lack vibrancy. In other words, the liveability factors are significantly missing despite their significance.

5.1.3 Social and cultural

Cosmopolitanism, social cohesion, art and music, and lifestyle (F15-F18) are the fore socio-cultural factors which can be loaded under socio-cultural aspects of city centres. Three factors that included cosmopolitanism, social cohesion, and lifestyle are found to be statistically significant, thus likely to influence the development of the central areas and attract people to such places. As observed in , the socio-cultural atmosphere in the three city centres is mixed (). For example, the situation of social cohesiveness is somewhat acceptable (RII = 0.62), which suggests that people are open, tolerant and bereft of the feeling of segregation to some extent. Similarly, the lifestyle in the city centres is also fairly acceptable (RII = 0.64). People follow both traditional and modern lifestyles. However, with a low RII (RII = 0.58), the city centres are barely open to cosmopolitanism and openness. Moreover, art and music are not found to be statistically significant as well as have low RII indicating that they might not influence the transformation of the city centres.

5.1.4 Productivity and sustainability

City centres are considered the nerve centres of cities. They are argued to play vital roles in economic activities. They offer physical and social connectivity, and diverse experiences and should be resilient and aesthetically pleasing. However, from this study, it was revealed that although all four factors (F19-F22) are statistically significant and could likely influence city centres, except for their endurance and resiliency (RII = 0.65), the condition of the other three factors is not fairly acceptable. In other words, the city centres do not enhance the local economy, environment and community significantly (RII = 0.58). Similarly, although they offer some physical connectivity, they fail in creating social connectivity (RII = 0.57) and lack options for diversity and experiences (RII = 0.54). These attributes are found to be statistically insignificant. However, the city centres are still functioning and look aesthetically fairly pleasing, which implies that they are enduring and resilient (). Overall, the scenario of productivity and sustainability of the city centres is marginal.

5.1.5 Human experience and community involvement

Enriched human experience and community involvement are two vital aspects of a great place. Three factors such as enriching experience, community involvement and participation, and belongingness (F23-F25) constitute this aspect. All three factors are found to be statistically significant and thus likely to influence the city centres. However, in the current state, the city centres do not offer any feel-good factors and activities that would enrich their experiences (RII = 0.55). The community rarely participates and engages in the decision-making and implementation of any development activities (RII = 0.54). In other words, ideas from the communities for the development of the place are neither solicited nor respected. Also, people do not experience belongingness and there is not much certainty in the permanency of tenancy, business and activities. (RII = 0.58). Thus, the city centres are devoid of important aspects related to human experience and community involvement, despite being governed by a democratic local governance system.

5.2 Critical challenges and opportunities of the city centres

The evaluation of the significance of various factors and their relative importance revealed that most of the factors (F1-F16 and F18-F25) except art and music (F17) under the five attributes such as visual and physical, liveability, social and cultural, productivity and sustainability and human experience and community involvement influence the transformation of the city centres. The city centres have some advantages, which include compact nature, availability of important socio-economic functions, well laid out spatial configuration, central congregation spaces, and tourist and cultural elements (although some are in dormant form). Specifically, currently, the conditions of certain factors such as architecture, public places, restaurants and dining, shopping, professional and administrative buildings, quality of buildings under visual and physical; social cohesion and lifestyle under socio-cultural aspects; and endurance and resilience under productivity and sustainability aspect are fairly acceptable. The advantages and intrinsic potentials of the above-mentioned factors offer opportunities for the revitalisation of the city centres. In contrast, a majority of the factors under all aspects are in unacceptable condition. For example, the city centres lack buzz, diversity, nightlife and accessibility. Similarly, these areas are observed to lack comfortability, safety, and vibrancy and are not walkable for people. Moreover, these areas do not portray an image of diversity and cosmopolitanism and openness. Although these areas have shown resilience, they do not offer an environment for the enhancement of the economy. Connectivity is also found to be a challenge. Furthermore, the role of people and the community is undermined by insignificant community participation and involvement. Moreover, the belongingness of the people to the central areas is meagre. Overall, these places also do not offer any enriching human experience. Consequently, these above-mentioned factors have turned into critical challenges which are needed to be addressed to transform the city centres.

5.3 Strategies to transform the city centres into great places

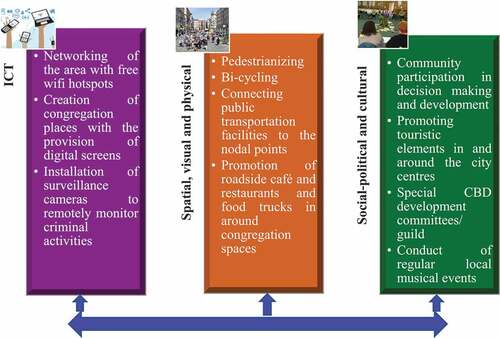

According to place theory, two important aspects are essential to transform the city centres: the creation/ up-gradation of a social setting through physical intervention (Laua and Lib Citation2019) and the empowerment of the community (Lew Citation2017; Laua and Lib Citation2019). So, several strategies were identified and evaluated to transform the city centres into great places. These strategies were categorised into three categories such as (1) ICT-related facilities, (2) visual, spatial and physical redevelopment, and (3) social, political and cultural elements. The strategies under each category were evaluated based on the ordinal regression model estimation findings as presented in . However, before the model results were used, the validity of the models was checked. The Model fit value (0.000 < 0.05), Goodness of fit value (0.381 > 0.05), Nagelkerke (Pseudo R2) (0.716 > 0.7) and the Test of parallel lines value (0.203 > 0.05) indicated that the model parameters are acceptable and the model estimation is valid ().

Table 4. Strategies to transform the city centres.

Table 5. Model validation parameters.

The strategies for ICT-related facilities have been examined previously in isolation (Das, 20,921). However, in this study, this aspect was integrated into other strategies while making model estimations to examine their influence. In alignment with the previous findings, Networking of the area with free wifi hotspots (ICT01), creation of congregation places with the provision of digital screens (ICT02), and installation of cameras to remotely monitor criminal activities (ICT05) are the three most important strategies under ICT (). This is likely to attract the relatively young generation. The integration of the ICT facilitate different activities and enables people to access real-time information on different incidents and happenings, marketing, branding and creating a unique image (Castells Citation1996; Pratt Citation2008; Alghamdi and Al-Harigi Citation2015; Das Citation2021). In addition to networking, a strategy for installing surveillance cameras and their remote monitoring is found to be significant. As suggested by Das (Citation2021), it is likely to assist in dispelling the fear of crime as well as reduce criminal activities.

Under visual, spatial and physical redevelopment, pedestrianising (SP01), bicycling (SP02) and connecting public transportation facilities to the nodal points (SP04) () are essential for increasing accessibility and connectivity (McGough and Thomas Citation2014; McDonald and Swinney Citation2019). Also, the promotion of roadside cafés and restaurants and food trucks around congregation spaces (SP05) might also help to attract people to the city centres and add buzz and vibrancy to the places.

Furthermore, community participation in decision-making and development (SO06), promoting touristic elements in and around the city centres (SO04) and the creation of special Central area development committees/guilds (SO07) are the major social-political and cultural strategies to enhance participation, belongingness and social cohesion (). This might change the perspectives of the people towards the place and the social setting (Almeida and Fumega Citation2012; Hemani and Das Citation2016). More importantly, to make these central areas great places, physical and socio-cultural transformations should complement the involvement and acceptance of the community (Silberberg et al. Citation2013; Ardill and de Oliveira Citation2018).

Therefore, to transform the city centres of South African cities into great places, a three-pronged strategic approach combining the strategies to provide relevant ICT-related facilities, improving visual, spatial and physical elements and creating an environment for human enrichment and community involvement in the development process as presented in needs to be adopted.

6 Discussions and implications

Many cities in the developing countries of Africa and Asia for example, cities of South Africa and India are facing spatial, physical built environment and environmental challenges. Specifically, the central areas are degenerating. To improve the condition of these central areas, the city governments are undertaking significant urban renewal and regeneration programmes. The major focus of these urban renewals and regeneration programmes in practice is physical transformation, although scholars have argued and proposed various approaches and theoretical frameworks (Cobbinah et al. Citation2019; Didier, Peyroux, Morange 201; Donaldson and Du Plessis Citation2013; Visser and Kotze Citation2008; Wilhelmsson et al. Citation2022). Further, arguments have been made for transforming a place or in other words central areas premising on the place theory (Strydom et al. Citation2018). Similarly, the integration of ICT has been argued (Das Citation2016, Citation2021). Although technology specifically ICT has become an integral part of the life of people and has been argued to be incorporated into placemaking (Das Citation2016, Citation2021; Relph Citation2016), its role in the development of places specifically in developing countries has been undermined. Furthermore, the urban development process is being taken up as an apolitical technical process and remains fragmented in many developing countries without the real involvement and participation of people and the various social solidarities in the decision-making and implementation of the project (Bailey and Eric Citation2016; Goodfellow Citation2014). In other words, socio-political and technological aspects are significantly undermined, which remained a significant gap in the urban renewal and regeneration or the transformation of the places. Consequently, any effort to regenerate or improve the city centres remains a meagre physical and spatial exercise without the involvement of the stakeholders, and considerations for integration of advanced technology or ICT. Thus, the solutions become short-term and lack proper acceptance from the stakeholders. Therefore, there is a need to explore a holistic approach that would assist in the transformation of the central areas of the cities.

Findings from the three case study cities of South Africa manifest that the central areas lack attributes such as enhancement and promotion of the old heritage, images, public spaces, accessibility and pedestrianisation, buzz, diversity, nightlife, restaurants and dining. etc. Furthermore, major challenges emanate from the lack of rich human experience and community participation in the development and management of the city centres. Also, the use of ICT remained a challenge. The apparent degeneration of the central areas of South African cities poses a severe challenge to the social-economic vitality of the cities. However, their revitalisation and transformation are critical to the sustainable development of the cities (Laua and Lib Citation2019; Das Citation2021).

Based on the findings, a three-pronged strategic approach was suggested. The basic premise adopted was the need for social innovation to bring back people to these places, and create belongingness and ownership (Almeida and Fumega Citation2012; Hemani and Das Citation2016; Ardill and de Oliveira Citation2018). The combined effect of the strategies (mentioned in section 5.3) would enable the creation of an environment for community participation including the creation of a special central area development committee (Ardill and de Oliveira Citation2018; Gün et al. Citation2021). This is likely to change the perspectives of people towards the social setting as well as enhance belongingness and ownership. The integration of ICT and free wifi hotspots to facilitate different activities and enable people to access real-time information could provide an added advantage and enable people to spend time and remain active in these areas. Also, the installation of surveillance cameras and their remote monitoring is likely to dissipate the fear of crime and encourage people to visit and spent time in the central areas (Das Citation2021; Gün et al. Citation2021). Promotion of the existing touristic and cultural elements in combination with accessible public transportation, pedestrianising and bicycling would provide tourists and visitors with the impetus to visit the places.

Further, two significant aspects came to the fore in addition to the efforts for the physical transformation of a place. First, while stakeholders’ participation in decision-making and implementation has been emphasised, which is highly essential in a pluralistic democratic society, it does not occur adequately. The reason could range from resource and time constraints to the unwillingness of the stakeholders to participate and the creation of an enabling environment by the governance and development agencies (Das et al. Citation2016). Also, managing a plethora of stakeholders and their diverse viewpoints remains largely an unresolved complex challenge in many developing countries (Beck et al. Citation2011). This leads to the need for the creation of an appropriate governance system to develop and manage the city centres within the larger governance systems of the cities (Almeida and Fumega Citation2012; Ardill and de Oliveira Citation2018; Gün et al. Citation2021). Perhaps, in this context to manage the diversity of stakeholders and their innumerable viewpoints, demands and aspirations, the premises of place theory may be augmented by considering the premises of the refurbished Dhal’s theory of pluralist democracy for good governance (Ney Citation2009; Beck et al. Citation2011). However, this study was limited to exploring the strategic options for transforming the central areas, and therefore detailed framework for a governance system was not explored.

The second aspect is the integration of ICT for the transformation of places. It was evidenced that ICT while facilitating various socio-economic functions can also engender the creation of a distinct image (Fernandez-Maldonado Citation2012; Das Citation2016, Citation2021; Yeh Citation2017). It also can assist in the reduction of crime and fear of crime. Furthermore, ICT can enable stakeholders’ participation in the governance system, or more specifically in decision-making and implementation directly (Fernandez-Maldonado Citation2012; Dameri Citation2017; Yeh Citation2017). So, as emphasised in previous studies (Das Citation2021; Gün et al. Citation2021), the integration of ICT in the central areas is essential for their transformation, specifically in developing countries such as South Africa.

7 Conclusion

The central areas of South African cities are in the process of degeneration. The traditional urban renewal processes with physical and spatial interventions may not be adequate to turn these places into great places and the solutions could be short-term. However, this study posits that, despite the plethora of challenges, a combination of social innovation (socio-cultural-political), spatial and ICT-related interventions could turn the city centres into great places. In other words, it can be argued that strategic interventions premised upon place theory could enable the revitalisation of the city centres and transform them into great places. In this context, however, two important aspects such as social innovation, i.e., socio-political considerations including stakeholders’ participation premised upon a responsive governance system and integration of ICT should be essential parts of the transformation process in addition to spatial interventions. This study while extending the discourse on urban regeneration in the developing world could provide valuable insights to urban planners, policymakers and city development authorities to think beyond the spatial and visual urban renewal or regeneration interventions and integrate ICT facilities and human enrichment and community empowerment elements to transform the city centres to great places.

Policy highlights

There is a need to move beyond the conventional spatial intervention to transform the city centres into great places in developing countries such as South Africa.

Social innovation and human experience and enrichment are critical for the transformation of the central areas.

Stakeholder engagement and people’s participation and involvement in decision-making and implementation of development and redevelopment programmes would enable co-design and co-development and enhance belongingness and ownership.

Integration of ICT is likely to play a critical role in enhancing connectivity, image building and making the place safer.

The combined effect of the spatial intervention, integration of ICT and social innovation is likely to transform the city centres into great places.

Ethical approval

Reference number: FEIT 09/17, Faculty Research and Innovation Committee (FRIC), Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology (FEIT), (Central University of Technology, Free State, South Africa).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dillip Kumar Das

Dillip Kumar Das (Prof.) has a PhD in Urban and Regional Planning with a Civil Engineering and city planning background. Currently, he is engaged in teaching, research, and community engagement activities at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. His research and consulting interests under sustainable urban and regional development include systems analysis, system dynamics modelling, infrastructure planning and management, smart cities, and transportation planning. He has co-authored two books as the lead author and published several peer-reviewed research articles.

References

- Alexander A, Teller C, Wood S. 2019. Augmenting the urban place brand – on the relationship between markets and town and city centres. J Bus Res. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.013

- Alghamdi SA, Al-Harigi F. 2015. Rethinking image of the city in the information age. Proc Comp Sc. 65:734–743. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2015.09.018.

- Al-Kodmany K, Ali MM. 2012. Skyscrapers and placemaking: supporting local culture and identity. Archnet-IJAR. 6(2):46–67.

- Almeida DN, Fumega JM. 2012. How can planning for sustainability improve Costa de Caparica’s nightlife? Int J Urban Sust Dev. 4(1):111–123. doi:10.1080/19463138.2012.667411.

- Ardill N, de Oliveira FL. 2018. Social innovation in urban spaces. Int J Urban Sust Dev. 10(3):207–221. doi:10.1080/19463138.2018.1526177.

- Bailey E, Eric MMN. 2016. Urban redevelopment and development relationship: a critical evaluation of Downtown Kingston redevelopment and the development of the Kingston metropolitan area of Jamaica. Int J Urban Sust Dev. 8(2):229–253. doi:10.1080/19463138.2015.1040407.

- Badenhorst W 2016. Revitalising city centres, policy context and trends relevant for partner cities in URBACT’s city centre doctor action planning network, State of the Art: City Centre Doctor Project, pp.1–28. [accessed 2020 May 27]. https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/city_centre_doctor_state_of_the_art.pdf

- Beck MB, Thompson M, Ney S, Gyawali D, Jeffrey P. 2011. On governance for re-engineering city infrastructure. Proc Inst of Civ Eng: Eng Sust. 164(ES2):129–142. doi:10.1680/ensu.2011.164.2.129Paper1000020.

- Castells M. 1996. The rise of the network society. Cambridge (MA): Blackwell Publishers.

- Corsane G, Davis P, Mutas D. 2009. Place, local distinctiveness and local identity: ecomuseum approaches in Europe and Asia. In: Anico M, Peralta E, editors. Heritage and identity: engagement and demission in the contemporary world. London; New York: Routledge; p. 47–62.

- Cobbinah PB, Amoako C, Asibey MO. 2019. The changing face of Kumasi Central, Ghana. Geoforum. 101:49–61. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.023.

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD. 2017. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Newbury Park, USA: SAGE Publications.

- Dameri RP. 2017. Using ICT in smart city. In: Smart city implementation. Progress in IS. Cham: Springer; p. 45–65.

- Das D. 2021. Revitalising the centres of South African cities through information communication technology. Urban Plan. 6(4):228–241. doi:10.17645/up.v6i4.4381.

- Das D. 2016. Engendering image of creative cities by use of information and communication technology in developing countries. Urban Plan. 1(3):1–12. doi:10.17645/up.v1i3.686.

- Das D, Sonar SG, Emuze F 2016. Comprehending the role of people in Urban redevelopment in Indian cities. In Ebohon OJ, Ayeni DA, Egbu CO, Omole FK (eds.) Procs of the Joint International Conference (JIC) on 21st Century Human Habitat: Issues, Sustainability and Development, 2016 Mar 21-24, Akure, Nigeria, 1677–1687.

- Delice A. 2010. The Sampling Issues in Quantitative Research. Educ Sciences: Theo & Prac. 10(4):2001–2018.

- Didier S, Peyroux E, Morange M. 2012. The spreading of the city improvement district model in Johannesburg and Cape Town: urban regeneration and the neoliberal agenda in South Africa. The Int J of Urb and Regl Res. 36(5):915–935. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01136.x.

- Donaldson R, Du Plessis D. 2013. The urban renewal programme as an area-based approach to renew townships: the experience from Khayelitsha’s Central Business District, Cape Town. Hab Int. 39:295–301. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2012.10.012.

- Fernandez-Maldonado A. 2012. ICT and spatial planning in European cities: reviewing the new charter of Athens. Built Env. 38(4):469–483. 10.2148/benv.38.4.469. [accessed 2021 Jan 30]

- Florida R. 2002. The rise of the creative class: and how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

- Florida R. 2005. Cities and the Creative Class. New York: Routledge.

- Gehl J 2016. Creating places for people, An Urban design protocol for Australian cities. [accessed 2020 Mar 16]. https://urbandesign.org.au/content/uploads/2015/08/INFRA1219_MCU_R_SQUARE_URBAN_PROTOCOLS_1111_WEB_FA2

- Gieryn TF. 2000. A space for place in sociology. Ann Rev of Soc. 26(1):463–496. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.463.

- Goldsmith S 2019. Designing human centred city, data-smart city solutions. [accessed 2020 May 13]. https://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/news/article/designing-human-centered-city

- Gün A, Pak B, Demir Y. 2021. Responding to the urban transformation challenges in Turkey: a participatory design model for Istanbul. Int J Urb Sust Dev. 13(1):32–55. doi:10.1080/19463138.2020.1740707.

- Hansen UE, Nygaard I, Romijn H, Wieczorek A, Kamp LM, Klerkx L. 2018. Sustainability transitions in developing countries: stocktaking, new contributions and a research agenda. Env Scie & Pol. 84:198–203. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.11.009

- Hemani S, Das AK. 2016. Humanising urban development in India: call for a more comprehensive approach to social sustainability in the urban policy and design context. Int J Urban Sust Dev. 8(2):144–173. doi:10.1080/19463138.2015.1074580.

- Harvey D. 2006. The limits to capital. London: Verso.

- Hsu C, Sandford B. 2007. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pra Ass Res and Eval. 12:11–18. http://pareonline.net/pdf/v12n10.pdf.

- Jencks C. 2000. Le corbusier and the continual revolution in architecture. New York: Monacelli.

- Jones C, Livingstone N. 2018. The ‘online high street’ or the high street online? The implications for the urban retail hierarchy. The Int Rev Ret, Dist and Cons Res. 28:47–63. doi:10.1080/09593969.2017.1393441

- Larbi M, Kellett J, Palazzo E. 2022. Urban sustainability transitions in the global South: a Case study of Curitiba and Accra. Urb Forum. 33(2):223–244. doi:10.1007/s12132-021-09438-4.

- Laua C, Lib Y. 2019. Analyzing the effects of an urban food festival: a place theory approach. Ann Tou Res. 74:43–55. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2018.10.004.

- Corbusier L. 1927. Towards a new architecture. London: John Rodker.

- Corbusier L. 1958. Modulor 2. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

- Lehmann S. 2010. Green urbanism: formulating a series of holistic principles. Surveys and Perspectives Integr Env and Soc. 3(2):1–10.

- Lew AA. 2017. Tourism planning and placemaking: place-making or placemaking? Tour Geo. 19(3):448–466. doi:10.1080/14616688.2017.1282007.

- Li Q. 2013. A novel Likert scale based on fuzzy sets theory. Exp Syst with Appl. 40(5):1609–1618. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2012.09.015.

- Lipietz B. 2008. Building a vision for the post-apartheid city: what role for participation in Johannesburg’s city development strategy? Int J of Urb and Reg Res. 32(1):153–163. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00767.x.

- Little D 2013. The global city- Saskia Sassen. Understanding society. [accessed 2020 May 13]. https://understandingsociety.blogspot.com/2013/09/the-global-city-saskia-sassen.html

- Lynch K. 1960. The image of the city. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press.

- McDonald R, Swinney P 2019. City centres: past, present and future, Centre for cities. [accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.centreforcities.org/reader/city-centres-past-present-and-future-their-evolving-role-in-the-national-economy/the-performance-of-city-centres

- McGough L, Thomas E 2014. Delivering change: putting city centres at the heart of the local economy, Centre for cities. [accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.centreforcities.org/reader/delivering-change-putting-city-centres-heart-local-economy/economic-importance-city-centres

- Ney S. 2009. Resolving messy policy problems: handling conflict in environmental, transport, health and ageing policy. London: Earthscan.

- Powe N, Hart T. 2008. Market towns: understanding and maintaining functionality. The Town Plan Rev. 79(4):347–370. doi:10.3828/tpr.79.4.2.

- Pratt AC. 2008. Creative cities: the cultural industries and the creative class. Geografiska annaler: Series B - Human geography. 90(2):107–117. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0467.2008.00281.x.

- Relph EC. 2016. Afterword. In: Freestone R, Liu E, editors. Place and placelessness revisited. New York and London: Routledge; p. 269–271.

- Sassen S. 1991. The global city. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sassen S. 1996. Cities and Communities in the global economy: rethinking our concepts. Am Beha Sci. 39(5):629–639. doi:10.1177/0002764296039005009.

- Savitch HV. 2010. What makes a great city great? An American perspective. Cities. 27(1):42–49. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2009.11.012.

- Silberberg S, Lorah K, Disbrow R, Muessig A. 2013. Places in the making: how placemaking builds places and communities. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; p. 1–60.

- Smith JW, Floyd MF. 2013. The urban growth machine, central place theory and access to open space. City, Cul Soc. 4(2):87–98. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2013.03.002.

- Song H, Gao BZ, Lin VS. 2013. Combining statistical and judgmental forecasts via a web-based tourism demand forecasting system. Int J Forecasting. 29(2):295–310. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2011.12.003.

- Steyn G. 2012. Le Corbusier’s town-planning ideas and the ideas of history. SAJAH. 27(1):83–106.

- Strydom W, Puren K, Drewes E. 2018. Exploring theoretical trends in placemaking: towards new perspectives in spatial planning. J Place Man Dev. 11(2):65–180. doi:10.1108/JPMD-11-2017-0113.

- Todes A. 2011. Planning: critical Reflections. Urban For. 22:115–133. doi:10.1007/s12132-011-9109-x

- Vanolo A. 2008. The image of the creative city: some reflections on urban branding in Turin. Cities. 25(6):370–382. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2008.08.001.

- Visser G, Kotze N. 2008. The State and new-build gentrification in central cape town, South Africa. Urb Stud. 45(12):2565–2593. doi:10.1177/0042098008097104.

- Wilhelmsson M, Ismail M, Warsame A. 2022. Gentrification effects on housing prices in neighbouring areas. Int J of Hous Mark and Anal. 15(4):910–929. doi:10.1108/IJHMA-04-2021-0049.

- Williams RA, Quiroz C 2020. Ordinal Regression Models. In Atkinson P, Delamont S, Cernat A, Sakshaug JW, Williams RA (Eds.), SAGE Research Methods Foundations. doi:10.4135/9781526421036885901.

- Yeh H. 2017. The effects of successful ICT-based smart city services: from citizens’ perspectives. Govt Info Quar. 34(3):556–565. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2017.05.001.

- Parnell S, Pieterse E, Watson V 2009. Planning for cities in the global South: an African research agenda for sustainable human settlements. in Shaken, shrinking, hot, impoverished and informal: Emerging research agendas in planning. Prog in Plan. 72:233–241.

- Wrigley N, Lambiri D 2014. High street performance and evolution: a brief guide to the evidence. Southampton, GB: University of Southampton; pp. 1–24. doi:10.13140/2.1.3587.9041

- Pred A 1984. Place as historically contingent process: Structuration and the time-geography of becoming places. Ann of the Asso of Amer Geog. 74(2):279–297.

- Peeters C 2015. How to design and analyse a survey. https://zapier.com/learn/forms-surveys/design-analyze-survey/ [Accessed on 19 May]

- Liggett D, McIntosh A, Thompson A, Gilbert N, Storey B 2011. From frozen continent to tourism hotspot? Five decades of Antarctic tourism development and management, and a glimpse into the future. Tour Manag. 32:357–36.

- Pulido-Fernández M, López-Sánchez Y, Pulido-Fernández JI 2013. Methodological Proposal for the Incorporation of Governance as a Key Factor for Sustainable Tourism Management: The Case of Spain. Int J of Hum and Soc Sci. 3(15):10–24.

- Sobaih AEE, Ritchie C, Jones E 2012. Consulting the oracle?: Applications of modified Delphi technique to qualitative research in the hospitality industry. Int J of Cont Hosp Manag. 24(6):886–906. doi:10.1108/09596111211247227.

- Lin VS, Song S 2015. A review of Delphi forecasting research in tourism. Curr Iss in Tour. 18(12):1099–1131. doi:10.1080/13683500.2014.967187.

- Lin VS, Goodwin P, Song H 2014. Accuracy and bias of experts’ adjusted forecasts. Ann of Tour Res. 48:156–174.

- Goodfellow T 2014. Planning and development regulation amid rapid urban growth: Explaining divergent trajectories in Africa. Geofor. 48:83–93. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.007.