ABSTRACT

The prevailing norm in Ghana’s rental housing market involves a mandatory and recurrent advance rent payment of two years or more by renters to their landlords. This paper employs sociological institutionalism, coupled with mixed-methods research design, to investigate the challenges renters face in adhering to the norm and its associated implications. Based on a survey of 362 renters across Ghana and an in-depth literature review, our findings demonstrate that extended advance rent periods, employment-related reasons, and limited savings are the primary factors contributing to the challenges renters face regarding the norm. Adhering to this norm often transforms renters into perpetual borrowers, limits personal development, and alters savings behaviour. The norm’s deep entrenchment can be attributed to Ghana’s political economy, market operations, and institutional deficiencies, perpetuating its prevalence. This research has implications for proposed interventions in the rental housing sector and advances our theoretical understanding of the emergence of distinct norms.

Introduction

Rental housing is a globally recognised alternative to homeownership (Scanlon and Kochan Citation2011), with approximately 1.2 billion people renting their dwellings worldwide (Gilbert Citation2016). The ongoing urbanisation of our planet, predicted to reach nearly 70% of the world’s population residing in cities by 2050 (DESA Citation2019), is expected to bolster the population of renters in both developed and developing countries (Gilbert Citation2016; UN-HABITAT Citation2016). Renting, particularly among young individuals, offers various advantages, including: (i) helping young people secure housing while saving for future homeownership (Cain Citation2017; Asante et al. Citation2018), (ii) providing flexibility for renters to move in and out of rental properties with relative ease (Scanlon and Kochan Citation2011), (iii) allowing renters to adjust their housing according to their budget, whether downsizing during economic hardships or upgrading as their income grows (UN-HABITAT Citation2003), and (iv) enhancing labour market mobility (Huisman Citation2016).

In Ghana, the population has grown from 24.7 million in 2010 to 30.8 million in 2021 (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2022). The youthful population, aged 15 to 39, which constituted 40.9% of the population in 2012 (Government of Ghana Citation2014), is expected to increase further. This population growth is accompanied by a concentration of young individuals in urban areas. Ghana’s urban population has risen from 45% in 1984 to 54.8% in 2021 (UN-Habitat, n.d.Footnote1; Government of Ghana Citation2014). Despite this population surge and rapid urbanisation, challenges persist in providing accessible, decent, and affordable housing in Ghana, a situation mirrored in many sub-Saharan African countries. Ghana’s housing provision has faced limitations since the colonial era’s housing for Second World War veterans (Tipple and Korboe Citation1998; Konadu-Agyemang Citation2001) and government-funded state housing projects post-independence (1957 to 1979). Under the current neoliberal framework, Ghana has not witnessed consistent national housing supply programmes (Al-Hafith et al. Citation2019). Instead, politically-motivated housing projects often remain incomplete or unoccupied (Ofosu-Kusi and Danso-Wiredu Citation2014). Consequently, 97% of Ghana’s 5.3 million housing stock consists of self-built units developed outside the formal planning system (Ehwi et al. Citation2020; UN-HABITAT Citation2011). The country currently faces a housing deficit of about 2 million units (Government of Ghana Citation2014), and it is estimated that urban Ghana alone will require 2.76 million new dwellings by 2030 to address this shortfall (UN-HABITAT Citation2011). In terms of tenure, 42.1% of households in Ghana own their homes, 29.1% live rent-free, and 28% are renters (Government of Ghana Citation2014). However, regions with larger cities, such as the Greater Accra and Ashanti regions, have more significant proportions of renters, at 40.9% and 33.7%, respectively (Government of Ghana Citation2014).

The rental housing market in Ghana is segmented into formal and informal categories (Arku et al. Citation2012). The informal sector further bifurcates into private/commercial rental housing and public rental housing (Arku et al. Citation2012). The private formal sector is primarily driven by profit-motivated real estate developers who construct properties for sale and, occasionally, for rent, typically in the up-market segment (Acheampong and Anokye Citation2015). This sub-market constitutes approximately 2.2% of the existing housing stock (Government of Ghana Citation2014). Public rental housing, as the name suggests, refers to properties funded and developed by the state or quasi-state entities like the State Housing Corporation (SHC) and the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT), which are rented to public-sector workers and civil servants (Adziabah Citation2018).

One distinctive aspect of Ghana’s rental housing market, in both formal and informal sectors, is the practice of demanding advance rent (referred to as AR) before occupancy. AR involves paying rents upfront at the beginning of a tenancy (Ehwi et al. Citation2020). This upfront payment typically covers rent for periods ranging from 6 to 60 months (Adu-Gyamfi et al. Citation2019). This practice differs from deposit-based rent systems common in many developed countries, where tenants usually continue to pay rent on a monthly basis after providing a rent deposit. In contrast, in Ghana, AR payments freeze rent payments for the entire tenancy duration (Ehwi et al. Citation2020). AR is seen as an insurance mechanism employed by landlords to safeguard against rent default (Arku et al. Citation2012) or unforeseen circumstances that could disrupt rent predictability and present value (Malpezzi et al. Citation1990). Some scholars (Asante and Ehwi Citation2022; Yankson Citation2012) argue that AR payments provide landlords with a lump sum of capital for home improvements or new construction projects (Ardayfio-Schandorf Citation2012). Moreover, in a highly inflationary economy, demanding AR can serve as a hedge against inflation (Luginaah et al. Citation2010; UN-HABITAT Citation2011).

Growing scholarly interest surrounds AR payments in Ghana’s housing literature, with previous studies (Ehwi et al. Citation2021; Gough and Yankson Citation2011; Obeng-Odoom Citation2011; Arku et al. Citation2012; Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018; Gavu Citation2020) exploring various facets of the practice. Research has delved into the psychological stress experienced by tenants when raising AR at the end of each tenancy cycle (Arku et al. Citation2012), the number of monthly incomes that both first-time and regular tenants must forgo to meet the AR requirement (Ehwi et al. Citation2020), the influence of landlords on the AR payment period (Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018), and the distinctions between renters who criticise AR payment and those who support it (Ehwi et al. Citation2021).

Beyond Ghana, studies indicate that the practice of AR is prevalent in countries like Senegal, Cameroon, Tanzania, Nigeria, and Angola (Olawande et al. Citation2012; Cain Citation2017; Africanews Citation2018; Andreasen et al. Citation2020). For instance, in Senegal, renters pay 3 months of AR to landlords (CAHF Citation2018). In Tanzania, Angola, and Cameroon, it is common for renters to provide 6 to 12 months of AR to landlords (Cain Citation2017; Africanews Citation2018; Cadstedt Citation2006). From an international perspective, Maguire (Citation2022) argues that a crudely modelled financial system within the housing market exemplified in many countries by rent-advance payment models contributes to debt burdens, evictions due to non-payments which are all prevalent challenges for renters.

However, Ghanaian renters face perhaps the most extreme form of AR practice. Studies by Arku et al. (Citation2012) and UN-HABITAT (Citation2011) reveal that renters in Ghana are required to pay between 24 and 60 months of AR, increasing by 55 to 75% at the end of each contract period. This practice is deeply ingrained to the extent that the government recently launched the National Rent Assistance Scheme (NRAS), specifically aimed at assisting regular income earners struggling with AR payments (New Patriotic Party Citation2020). The scheme, funded with US$1.7 million in capital, directly pays AR to landlords on behalf of renters with regular incomes.Footnote2

Our argument is that the practice of advance rent payment in Ghana has become a norm. What remains less understood are the inherent difficulties associated with complying with this norm and how the norm is sustained beyond tenants’ precarity and landlord’s exercising their monopoly power. Renters may struggle to meet their rent payment obligations due to various factors, including insufficient personal financial planning, unforeseen emergencies requiring the use of the allocated funds, or instances where landlords unilaterally increase rent beyond what was initially anticipated. In any case, whether the rent is in arrears or not, landlords typically demand two years or more years advance rent when payment has to be made. Thus, the empirical questions explored in this study are as follows: 1) Why do renters find AR payment difficult, despite it being an established norm and how does AR payment impact them? 2) How is the AR payment sustained as a norm in Ghana’s rental housing market? We ask these questions because the influence norms have on actors’ compliance is often unproblematised. In other words, the conforming power of norms often overshadow the problematics actors face in the process. Our paper illuminates this systematically less-researched area.

While building upon recent scholarship on the AR system in Ghana (Arku et al. Citation2012; Asante et al. Citation2022; Ehwi et al. Citation2021; Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018), this work distinguishes itself in three ways. First, it illuminates the factors that hinder some renters from embracing the AR practice, despite its normalisation. Additionally, it examines the various factors, beyond individual circumstances, that have entrenched and continue to sustain this norm in Ghana’s rental housing market. Secondly, beyond Ghana, insights from study will contribute towards deepening understanding on a sparse researched area of rental housing markets – the operation of rental housing deposits, which till date, has been dominated by scholarship on typologies and econometric modelling from Asian countries like Korea (Lee and Chung Citation2010; Park and Pyun Citation2020). This insight remains crucial because advance rent and various forms of deposit schemes mark the entry points into rental housing. In other words, the growing literature on access to rental housing (e.g. Lu and Burgess Citation2023; Wendy et al. Citation2015) must be complemented by scholarship on rental deposit schemes to enrich understanding. Lastly, it demonstrates that Ghana, like Anglo-Saxon countries, ‘offers unregulated, market-based PRS [private rental sector] with little legal/de-facto security of tenure of tenure, offering landlords unrestricted power to select tenants, set/increase rents or evict without giving a reason’ (Soaita and McKee Citation2019, p. 149).

The article is structured as follows. After this introduction, Section two provides a brief review of the advance rent system in Ghana, highlighting its origins and rationale. Sociological institutionalism is elaborated as the theoretical basis of this study in Section three, while Section four elaborates on the research approach. The empirical research findings are discussed in Section five, while Section six illuminates the structural factors that have entrenched and sustained the AR payment in Ghana, and concludes.

The advance rent system in Ghana: a brief review

The regulation of landlord-tenant relationships and the broader rental housing system in Ghana has been governed by the Rent Act Citation1963 (Act 220) since the 1960s. This act established the office of the Rent Commissioner, responsible for administering and enforcing its provisions. Initially, Act 220 did not specify the duration over which landlords could charge rents. A study by Ninsin (Citation1989) revealed that during the tumultuous political period of 1982–83, landlords exploited this legal loophole, coupled with a shortage of residential accommodation in major cities, to significantly raise rents, extract substantial sums of AR from prospective tenants, and illegitimately evict existing tenants.

In response to this situation, the government passed three laws: (i) Rent Control Law PNDC Law 5, (ii) Compulsory Letting of Unoccupied Rooms and Houses Law PNDC Law 7, and (iii) Rent Tax Law 1984 PNDC Law 82. These laws aimed to reduce rents for all rental accommodations, make it an offence for landlords to refuse to let out dwellings, and impose new taxes on landlords. Interestingly, landlords in major cities and towns formed associations to resist state oppression. Their activism resulted in the enactment of the Rent Control Law 1986, PNDC Law 138, which eliminated the protections tenants had enjoyed under the previous laws. Nevertheless, the Act does provide some tenant-friendly provisions, specifying that landlords should not demand AR of more than 6 months for shorter tenancies and 12 months for longer tenancies.

Following the introduction of this law, Ninsin (Citation1989) noted that landlords intensified their exploitative treatment of tenants, a situation that has persisted to this day. Enforcement of the AR provision has been challenging for the Rent Control Department. As Kufuor (Citation2018) points out, the Rent Control Department has been ineffective in enforcing the Act due to understaffing and lack of resources. Consequently, there has been limited outreach to educate landlords and tenants about their rights and grievance procedures. The breach of Rent Act provisions has prompted calls for stronger enforcement by the Rent Control Department. Additionally, Ghana’s National Housing Policy recommends a review of the Rent Act Citation1963 (Act 220) to streamline rent regulations, empower the Rent Control Department, and encourage investments in the construction of rental housing while safeguarding vulnerable households from abuse by property owners (Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing Citation2015, p. 17).

It can be argued that beyond political and economic factors, the persistence of AR payment in Ghana is influenced by market failures, exemplified by a consistent housing shortage compared to demand. For instance, the Government of Ghana (Citation2014) reported that the cumulative housing deficit in Ghana in 2010 stood at 717,000 when computed based on 6 persons per household in a 2-bedroom unit. This deficit surges to 2.8 million when calculated using 4 persons per household in a 2-bedroom unit. This growing deficit often compels desperate renters to agree to extended AR payment terms with landlords who seem to capitalise on the housing shortage to maintain the practice without investing in improving existing housing stock (cf. Ehwi et al. Citation2020, Ehwi et al. Citation2021; Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018).

In the wake of significant job losses and wage cuts due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Aduhene and Osei-Assibey Citation2021), the Government of Ghana has sought to encourage landlords to comply with the 6-month AR provision of the Rent Act Citation1963. However, it remains unclear if this statement has had a substantial impact, except for a case that made headlines where a landlord willingly offered a 3-month rent waiver to tenants (Dowuona Citation2020).

Scholars have shown a growing interest in analysing the everyday experiences of renters concerning AR payments. For instance, Arku et al. (Citation2012) conducted seminal work examining housing situations and landlord-tenant relations in informal rental housing in Adabraka, Accra. In a related study, Owusu-Ansah et al. (Citation2018) investigated the relative power of landlords and tenants in Ghana’s rental housing market from a public-choice perspective. Both Arku et al. (Citation2012) and Owusu-Ansah et al. (Citation2018) reported that while some tenants perceived AR as offering stability by eliminating the need for monthly rent payments, most renters expressed concerns about the significant financial pressures associated with the large AR, viewing it as a ‘trap’ and an impediment to both spatial and occupational mobility. As a result, many renters aim to combine renting with building their own houses.

Asante et al. (Citation2018) examined renters’ experiences in combining AR payments with self-building on meagre incomes. They found that this combination imposes stress and undue financial burdens on renters, compelling them to sacrifice non-housing expenditures, such as clothing, support for extended family members, marriage, higher education, and vehicles, among others. Ehwi et al. (Citation2020) revealed that renters in Dansoman, Accra, must save the equivalent of 7 months and a week’s worth of their net income to meet AR obligations, with first-time renters disproportionately impacted, having to save 9 months and a week’s worth of their net income. This financial commitment increases to 13 months and a week’s worth of net income when tenants have to pay a 2-year AR and furnish their dwellings. Such substantial initial financial commitments may hinder households’ ability to meet non-housing expenditures.

While there are both critics and proponents of AR, Ehwi et al. (Citation2021) recently examined the differences between these two groups and modelled the factors predicting the likelihood of being a critic of AR payment. They found that both groups differed in terms of the association between their educational attainment, monthly expenditures, and employment sector. Their model indicated that monthly expenditures, the number of bedrooms, and AR duration significantly predicted the likelihood of being a critic. Despite this growing body of literature, there is limited qualitative insight into the reasons some renters find AR payments challenging.

Sociological institutionalism: norms and their impact on social behaviour

Institutions are conceptually understood in various ways, influenced by different disciplines and ontologies (Sorensen Citation2018). For instance, North’s (Citation1990) definition of institutions as ‘any form of constraint human beings devise to shape human interactions’ (p. 1) and their significant role in reducing uncertainty by establishing a stable structure for human interaction is often linked to rational choice ideals. In contrast, Hall and Taylor’s (Citation1996) perspective characterises institutions as not solely formal rules, procedures, or norms, but as symbol systems, cognitive scripts, and moral templates that provide the ‘frames of meaning’ guiding human action. This sociological viewpoint reflects sociological institutionalism, one of the three strands of the ‘new institutionalism,’ alongside rational choice and historical institutionalism (Hall and Taylor Citation1996; March and Olsen Citation2006).

Sociological institutionalism focuses on social agents who operate according to a prescribed ‘logic of appropriateness’ within a framework of socially constituted and culturally shaped rules and norms (Schmidt Citation2015). From this sociological perspective, institutions encompass norms, cognitive frames, and systems of meaning that guide human actions by providing a context for purposeful activities (Schmidt Citation2015, p. 1).

Norms, in this context, are often considered the unwritten rules of the game, as North (Citation1990) noted. They are perceived as recurring practices widely accepted in specific social, political, and cultural contexts, functioning as potent frameworks for structuring incentives, influencing behaviour, and validating actions (Miller and Banaszak-Holl Citation2005; Rakodi Citation1995). Like other forms of institutions, the power of norms over people’s actions is rooted in the fact that norms establish standards and modes of behaviour that result in rewards when adhered to and sanctions when violated (Ehwi et al. Citation2020; Lowndes Citation2001). In other words, individuals tend to follow norms as long as the potential punitive sanctions for defiance outweigh the benefits associated with disobedience (Alasuutari Citation2015).

Based on this interplay between rewards and sanctions, norms are recognised for their ability to bestow legitimacy on individuals and their actions (Lowndes Citation2001). It is also observed that ‘norms and shared understandings are usually conceived as operating beyond the scale of individual actors or groups, although in some situations, relatively powerless groups can also generate and articulate new ideas and visions for shared spaces through local collaborative action’ (Sorensen Citation2018, p. 5). This implies that norms can emerge from the interests and practices of specific agents or groups in society, including landlords (Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018).

However, it is important to note that adherence to accepted norms does not always lead to behaviour that is legally sanctioned in society (Olivier de Sardan Citation2015). In certain cases, compliance with norms may result in violations of legal and statutory provisions. For instance, Ehwi (Citation2019) illustrates how developers of gated communities in Ghana initiate building projects without first obtaining a land title certificate and planning permission due to norms surrounding potential re-sales of land by chiefs who sell the land. Thus, adherence to norms can sometimes lead to breaches of the law, even when the two coexist. Yet, the ‘norms-behaviour nexus’ has paid relatively little attention to what adherents endure to conform to normative demands and what they compromise, trade-off, or relinquish in the process.

Applying these sociological reflections to the context of Ghana’s rental housing market, Ghana’s Advance Rent (AR) system can be rightfully conceptualised as a norm. This is because it is practically impossible to find rental accommodation that does not require AR for a duration exceeding the legally permissible limit (Ehwi et al. Citation2020). The practice has become pervasive throughout Ghana, with higher prevalence in major cities like Accra, Kumasi, Takoradi, and Tamale, where rapid population growth and housing access challenges persist (UN-HABITAT Citation2011). However, as demonstrated empirically by Owusu-Ansah et al. (Citation2018) using public choice theory, this norm originated and has been sustained by formerly less influential landlords who, collectively, have gained market power due to the scarcity of decent rental housing in Ghana (Ehwi et al. Citation2021). These landlords, empowered by their newfound market position, have fostered a norm of charging AR for periods exceeding the stipulations of Ghana’s Rent Act, Citation1963 (as amended). Section 25(5) of the amended law stipulates that:

Any person who as a condition of the grant, renewal or continuance of a tenancy demands in the case of a monthly or shorter tenancy, the payment in advance of more than a month’s rent or in the case of a tenancy exceeding six months, the payment in advance of more than six months’ rent shall be guilty of an offence and shall upon conviction by the appropriate Rent Magistrate be liable to a fine not exceeding 500 penalty units or in default imprisonment term not exceeding 2 years or both.

Moreover, the recent government pilot policy scheme known as the National Rental Assistance Scheme (NRAS), in which the government pays landlords a lump sum of AR (typically covering 2 years) on behalf of tenants seeking to renew or rent a dwelling in exchange for monthly repayments from tenants, further solidifies the status of AR as a norm (NRAS .Citationn.d.). However, the existing body of literature, particularly within sociological institutionalism, often lacks clarity on what agents or actors endure, trade-off, or relinquish when conforming to the ‘logics of appropriateness’ prescribed by norms (Schmidt Citation2015). Consequently, introducing these arguments concerning the ‘norms-behaviour’ nexus into Ghana’s rental housing market provides an opportunity to investigate why renters find AR payments challenging and the sacrifices they make as a consequence of adhering to this market norm.

Research approach

The context surrounding the empirical data gathering of this research deserves some attention before delving into the research design and data collection. The research was conceived and undertaken immediately after the COVID-19 lockdown was lifted in Ghana (May-June 2020). At the time, although the lockdown imposed in the Greater Accra and Greater Kumasi Area had been lifted, several COVID-19 restrictions, including wearing of nose masks and maintaining social distance, were still in force. There was a palpable sense of scepticism, anxiety, fear, and worry among the populace, partly because it was perceived that Ghana’s lifting of the lockdown was rationalised on the basis of the economic hardship the lockdown inflicted on the population rather than reduced case numbers (Foli and Ohemeng Citation2022). Furthermore, the authors were outside Ghana, making it impossible to design research that takes advantage of in-person contact.

Against this backdrop, it was determined that an online survey was the most appropriate research design. Aside from the fact that many scholars at the time also turned to online surveys to gather data due to similar health and safety concerns (see Amerio et al. Citation2020; Jones and Grigsby-Toussaint Citation2020), online offered advantages including cost effective (printing, commuting, field assistants), could reach wider population, offer convenience and privacy to respondents, provide speed in data collection, automated data entry and analysis (Wright Citation2005).

The target population for this study comprises households in Ghana that are renting their accommodations. However, there was no database of these renters or how to reach them. Hence, we relied on non-probabilistic sampling techniques by combining convenience and snowball sampling (Emerson Citation2015). The online survey was designed using Qualtrics, a survey development software. The survey questionnaire gathered three main forms of information. The first section collected data on respondents’ housing circumstances, including tenancy status, type of house, rent paid, tenancy period, rent advance period, number of bedrooms, etc. The second section gathered data on respondents’ perceptions of the difficulty they face in paying the AR. Respondents were asked to rate the difficulty on a Likert Scale of 1 to 5: where 1 = Not difficult at all, 2 = Not difficult, 3 = Not sure, 4 = Difficult, and 5 = Extremely difficult. Respondents who found the AR payment difficult (Scales 4 and 5) were asked to explain why, given that AR has become a norm in Ghana’s rental housing market. The third section collected data on respondents’ socio-demographic backgrounds, including age, gender, marital status, employment status and sector, and monthly expenditure.

After designing the survey, an anonymous URL to access it was generated. We used multiple strategies to circulate the survey. These included sending the URL via email to individuals and groups for whom we had contact information, such as the general public, university lecturers, officials working in district assemblies with rent control departments, and members of professional groups like the Ghana Institution of Surveyors (GhIS). We also posted the URL on social media platforms like Twitter, tagging government ministries and agencies, including the Ministry of Housing and the Ministry of Information. We sent private social media messages with the survey URL to social media influencers, requesting their assistance in sharing the survey with their followers. We also asked recipients to share the survey link with others. To ensure that respondents met specific eligibility criteria, we clarified in the survey introduction that only individuals currently renting and living in Ghana were eligible to participate. Data collection took place from May to June 2020, with 362 respondents from across the country participating in the survey .

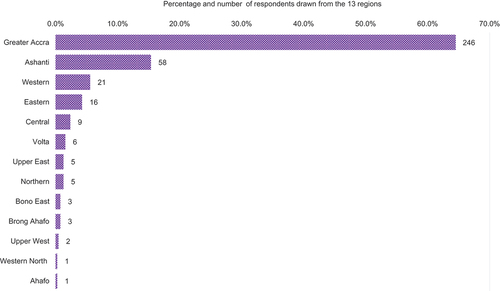

Figure 1. Regions in Ghana where respondents were drawn from.

Data from the closed-ended questions were analysed using simple descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and percentages, which are presented in tables. Qualitative data related to why renters find the AR payment difficult were analysed using a thematic analytical approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The thematic analysis followed a 5-stage process of transcript analysis comprising: a) a thorough review of all qualitative responses from the survey and taking detailed notes of all explanations renters offered in relation to challenges with paying the advance rent; b) noting all the significant quotes that best captured why tenants found the payment of advance rent challenging; c) classifying the reasons offered, developing coding for them and identifying those that constituted major themes c) selecting the main themes to be included in the write-up; and e) finally, interpreting the theme taking note of the context in which they were used and their implications. In line with research ethics, the identities of all respondents were anonymised using the codes MT and FT as descriptors of the male and female tenants, respectively.

Findings

Respondents’ socio-demographic profile

The study included respondents from all 16 regions of Ghana, but a majority (66.1%) were from the Greater Accra Region, followed by the Ashanti Region (14.1%) and the Western Region (5.5%). This concentration is not surprising since the Greater Accra and Ashanti regions have a higher number of tenants compared to other regions (World Bank Citation2014). The respondents consisted of 58.6% males and 40.1% females, with a mean age of 32 (50th percentile). Almost an equal percentage of respondents were never married (47.2%) and married (49.2%). In terms of educational attainment, 56.4% had been educated up to the tertiary level, while 43.6% had post-tertiary education. The majority of respondents (88.4%) were employed. The mean monthly expenditure of respondents was GHȼ 1,500 (US$264.17), which is 40% higher than the national average monthly expenditure of GHȼ 1,071Footnote3 (US$189) (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2019a) .

Table 1. Respondents’ demographic profile.

Respondents’ housing situation

provides information about the housing situation of respondents. About 36.7% were renting for the first time, while 63.3% were considered ‘regular renters,’ having changed houses approximately 2.75 times. Surprisingly, more than 30% of renters did not sign a tenancy agreement, although most respondents were graduates who would typically sign agreements when renting. The mean household size was 4.10, slightly higher than the national average of 4.0 (Government of Ghana Citation2014). In contrast to national statistics indicating that 57.3% of Ghanaians live in compound houses, this study found that 33.6% lived in compound houses, while 42% lived in flats/apartments. The average number of rooms occupied was 2.27, and the average tenancy duration was 1.93 years. The mean monthly rent was GHȼ 535.11 (US$94.24), translating to an annual rent of GHȼ 6,421.32 (US$1,130.87) when multiplied by an average tenancy period of 1.93 years. This annual rent equates to a rental advance of GHȼ 12392.53 (US$2,182.48),Footnote4 which is higher than previous reports. About 58.6% of respondents found the AR payment difficult, while 31.7% did not, and 9.7% were unsure. Renters’ monthly rent constituted 27.3% of their total monthly expenditure, which is higher than the official housing expenditure figure of 15.8% but still lower than the conventional affordability threshold of 30% (Stone Citation2013).

Table 2. Respondents’ housing situation.

Reasons why renters find the rent advance payment difficult and impacts

This section presents findings on why respondents find the payment of the Advance Rent (AR) difficult, even though it has become a norm in Ghana’s rental housing market. Five primary reasons for this difficulty emerged:

Longer rent advance period and affordability problem

Typically, the rental period is influenced by various factors, including a robust referencing system (Yankson Citation2012), landlords’ assessments of prospective tenants’ ability to pay rent periodically (Ehwi et al. Citation2021), insurance coverage against voids, enforceable legislation for easy possession recovery (Obeng-Odoom Citation2011), and landlords’ biases and stereotypes (Asante and Ehwi Citation2022). However, in Ghana, the absence of a reliable reference system and the prevalence of informal sector workers often lead landlords to demand advance rent (AR) for extended periods. The AR is calculated by multiplying the monthly rent by the requested tenancy duration by the landlord. Many tenant respondents regarded these two variables as problematic when asked about the difficulties of AR payments. They expressed their concerns about the longer payment periods with the following assertions.

I found it difficult to renew my tenancy because the landlord was demanding advance rent for 4 years. I don’t understand why they do that in this difficult country (MT, 32, Greater Accra)

For me, I will say, the difficulty comes from the fact that the time frame over which we have to pay the rent advance is too long. Paying advance payment for 2 years was not easy for me at the time. Sometimes, I am tempted to think that they [the landlords] are just taking advantage of us [the tenants] (MT, 35, Ashanti)

In Ghana these days, raising the 2 years advance is challenging. It wouldn’t have been a problem if the landlord allowed me to pay the rent every month because I can hustle to pay. But he insists that the 2 years rent must be paid upfront. As a pupil teacher, I find this totally unfair and exploitative (FT, 31, Northern).

The sentiment of exploitation among respondents is valid, given that Section 25(5) of Ghana’s Rent Act, Citation1963 (as amended), prohibits landlords from charging AR for more than 6 months in case of longer tenancies. However, these sentiments raise questions about the extent to which norms influence behaviour and under what circumstances norms fail to guide social behaviour. We found that norms might fail to influence behaviour when rent payments consume a significant portion of renters’ salaries. Typically, a rent-to-income ratio of 1 to 3 is considered affordable (UN-HABITAT Citation2011; Wilson and Morgan Citation1998). In Ghana, a World Bank study in 2014 pegged affordable rents at 10% of monthly income. Our findings, however, suggested that even though monthly rent is suspended after paying the AR, renters still complained that the contract rent used to calculate the AR exceeded this affordability threshold, as the following quotes illustrate:

When I compare the rent charged to my salary, I think it takes about 20% of my salary. There are other non-housing bills that I also have to pay (FT, 34, Western)

The monthly rent my landlord charges is about a third of my monthly salary, which leaves very little for me to use for sustenance, and other expenses. (MT, 44, Greater Accra)

These quotes are significant because renters perceive their rents as consuming a third or more of their income. However, when considering monthly expenditure, rent payments constitute less than 30%. This indicates that renters’ perception of rent unaffordability is related to their incomes rather than their expenditures. This aligns with Willis and Tipple’s (Citation1991) assertion that in informal economies, using expenditure rather than income is a better measure of affordability since expenditures are not necessarily dictated by people’s income.

Employment-related reasons

We found that four employment-related factors were cited by respondents as reasons why they found the payment of the AR difficult. The first revolves around the precarity associated with unemployment. This type of unemployment is often triggered by unforeseen circumstances such as business closures, job layoffs, or the loss of savings and investments, especially following the recent banking crisis and financial sector clean-up in Ghana (Tella et al. Citation2020). Efforts to secure new jobs and start saving proved futile for some tenants, as indicated by the following remarks:

lost my work 7 years ago and since then I have been trying to find a new job but I have not found any as of yet (MT, 31, Ashanti).

There was not enough income coming in to pay the AR because I no longer have a job (MT, 26, Volta).

It was difficult paying the AR because I was unemployed then and had no means of earning income (MT, 32, Greater Accra).

These sentiments, articulated by ‘graduate renters,’ underscore the prevalence of graduate unemployment in Ghana (Zakaria and Alhassan Citation2019). While it was beyond the scope of this article to determine the exact reasons for graduate unemployment, factors identified by Graham et al. (Citation2019), such as a lack of relevant work experience, limited information on job availability, low social capital, and high work-seeking costs, may hold relevance.

The second employment-related factor making it difficult for renters to pay the AR, despite the norm, relates to households with only one working adult. Typically, in Ghanaian societies with a lone working adult, there is a social expectation that this ‘perceived successful individual’ should assume responsibility for the well-being of both their nuclear and extended families (Acheampong Citation2016). In such cases, although renters understand that AR expenditure is non-negotiable, competing family needs make it challenging to have enough money to pay the AR, as some respondents disclosed:

I am the only person working in my family and I have to provide for my family members and also pay the AR. It is not easy at all (MT, 38, Ashanti)

The third employment-related factor highlighted by respondents pertains to new employment and the lack of adequate savings when the AR becomes due. This primarily applies to newly employed individuals rather than those with considerable work experience and savings (Ehwi et al. Citation2020). The following quotes illustrate this:

I had only just started working and I was being evicted from my old place if I could not raise the AR (MT, 24, Greater Accra)

I had just taken up a job after over a year of not working (FT, 30, Ahafo)

The fourth employment-related factor relates to low-paying jobs and salary payment delays. Recent studies indicate that wages in Africa are generally low compared to other countries and regions worldwide (ILO Citation2019; World Bank Citation2014). The following quotes explain why the difficulty persists despite the AR’s normalisation in the rental housing market:

My salary was woefully inadequate to cater for my daily needs. I had little to save (MT, 32, Bono East).

I was required to pay 2 years advance rent and my income cannot support that level of expense (FT, 35, Ashanti)

Don’t have a well-paid job and all places were asking for 2 years rent advance which was more than my annual salary (MT, 27, Ashanti)

Some tenants faced the additional problem of delayed income payments, making it difficult to plan for the AR payment. They expressed concerns like ‘Salary was not coming as expected,’ ‘My salary was delayed for 3 months,’ and ‘I haven’t been paid my salary yet’ to substantiate their claims. Anecdotal evidence suggests that these low wages are unnecessarily delayed for weeks and months before employees finally receive them. These delays cause undue financial hardships and initiate a cycle of borrowing behaviour, making it difficult for employees to meet financial obligations promptly. The situation is even more challenging for fresh graduates undertaking their mandatory national service, as the allowance paid by the government to national service personnel is insufficient to cover 3 months’ rent for decent accommodation, let alone 2 years or more. Some tenants expressed the following concerns:

If the allowance doesn’t come in time, then I will face difficulties in paying the AR (MT, 23, Greater Accra)

I was a national service person and earned a little over GHȼ500 (US$88.06) every month (FT, 28, Ashanti)

Due to low income, some tenants indicated that they had to take up additional jobs to pay their AR. According to two tenants, ‘Salaries are very low, so I had to do other side jobs,’ and ‘I had to work extra hours.’ Low earnings may force graduates to accept (additional) jobs that may not match their qualifications to meet pressing financial obligations. Taken together, these four employment-related reasons explain why graduate renters, despite the AR becoming a norm in the Ghanaian rental housing market, still struggle to adhere to this rational expectation.

Limited savings and perpetual borrowing

Another reason why renters find AR payments difficult, despite their normalisation, is the limited savings culture. This is primarily because some renters perceive their incomes as insufficient, as highlighted by one of them:

I didn’t have enough money saved up in my Credit Union account and hence had to add a whole month’s wage to my balance and find a fellow credit union member to assist me to access the required amount needed for the rent (MT, 38, Ashanti)

As a result of low savings, paying the AR depletes the limited income that renters have managed to save over time. The following excerpts confirm this point:

To pay the rent, I had to deplete my savings (MT, 31, Volta)

All your savings over the years goes into rent with nothing left for you for any investment (FT, 27, Northern).

Before I could pay the rent, I had to use all my savings and start all over again (MT, 33, Greater Accra)

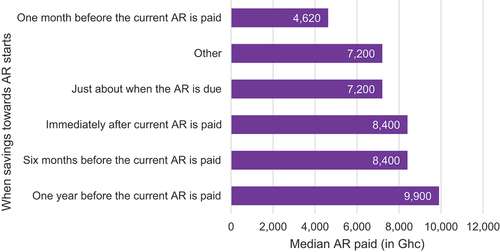

This precarious situation implies that renters often find themselves in a vicious cycle where the sole purpose of saving is to pay the AR. The prominence of the AR payment and its significant influence on renters’ behaviour can be seen from when they begin saving towards the AR payment. As illustrates, one in three tenants who find AR payments difficult starts saving immediately after the current one is paid, while one in five begins saving a year before the current lease expires. In total, 56.6% of all renters start saving towards the AR at least a year in advance.

Table 3. When renters start saving towards paying the rent advance.

In addition to their low income, part of the reason for this saving behaviour is the substantial AR payment they have to make. As shows, renters who start saving towards the AR earlier, including one year ahead, six months ahead, and immediately after the current AR payment, also tend to pay the highest median AR amounts of GH¢9,900 (US$1,728), GH¢8,400 (US$1,466), and GH¢8,400 (US$1,466), respectively.

Figure 2. When savings for AR payment start vs. Median AR paid.

Channelling practically all their savings towards AR payments means that renters have nothing to fall back on in times of emergencies, as one respondent eloquently stated:

Paying advance rent meant letting go/emptying my entire personal savings plus a loan from a friend. It meant in case of an emergency, I had nothing to fall back on (MT, 30, Ashanti).

For some renters, saving all their income to pay the AR means postponing other equally important life goals, such as pursuing further education, personal professional development, or learning a trade. As one tenant summed up the ordeal:

I was saving towards my master’s degree but I had to divert that funds into paying the advance rent and start saving all over again (FT, 32, Greater Accra).

Other tenants lamented how saving all their income to pay the AR has made them chronic borrowers and led to perpetual debts to cover other essential aspects of life, including taking care of family members. These tenants often borrowed from various sources, including friends, employers, and relatives due to their social ties. The following quotes illustrate this:

I am always having to borrow money to supplement some of my family needs. I’m grateful that the people I borrow from mostly are my friends. Else, I don’t know what would have happened (MT, 38, Greater Accra).

My employer helped me pay for the advance rent by giving me a loan (MT, 40, Greater Accra)

Those who do not have this social capital or do not want their family and friends to know the austere life they are living are compelled to resort to loans from banks and other micro-credit institutions (MT, 30, Greater Accra). This practice of forced borrowing, which some renters must endure, aligns with findings from Owusu-Ansah et al. (Citation2018) and Arku et al. (Citation2012), who also observed that to pay the substantial AR, renters have to resort to borrowing from friends, family, and sometimes employers.

Discussion

In this section, we move beyond our empirical findings to illuminate how the constellation of various factors that have contributed towards entrenching AR payment as a norm in Ghana’s housing market.

A fundamental aspect to underscore at the outset is the substantial disparity between our study participants and the general rental household population in Ghana. Our participants boast significantly higher levels of education, with 56.4% having attained tertiary education and 43.6% holding post-tertiary qualifications. This contrasts sharply with the 6.3% and 0.5% educational attainment rates, respectively, for the general population (Government of Ghana Citation2019, p.19). Moreover, our participants demonstrate elevated mean monthly expenditures, averaging Ghc1,500, in contrast to the national average of Ghc 1,071 (Government of Ghana Citation2019, p.199). They also manifest a distinct preference for flats and apartments over compound houses and have exclusive access to basic amenities, placing them within the emerging middle-class segment of Ghana’s population (c.f. Budniok and Noll Citation2018). This unique demographic positioning allows our study to extend the discussion on AR payment challenges to this hitherto unexamined social class.

When focusing on this specific social class, our research findings unveil that the difficulties associated with AR payments in Ghana do not solely afflict the poor, informal sector workers, or inhabitants of informal private housing, as may have been widely assumed. Instead, highly educated and seemingly well-off formal sector employees also grapple with these challenges. This revelation raises critical questions about the 'actually existing ‘middle-class’ in Ghana (Brenner and Theodore Citation2002). It beckons us to contemplate whether the notion of the middle class is merely a semantic label, devoid of the economic prosperity traditionally linked to this social stratum (Budniok and Noll Citation2018; van Blerk Citation2018). Moreover, it prompts a consideration of whether the escalating housing deficit in Ghana drives landlords to seize rent gaps without contributing to housing stock improvement. This scenario is the result of a marked ideological shift in Ghana regarding housing provision and rent determination, underpinned by policy advisors endorsing an unregulated free market (Obeng-Odoom Citation2011; Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018). Obeng-Odoom (Citation2010) concludes that most political parties in Ghana have embraced a market-led approach to housing provision across all tenures.

We contend that as long as neoliberal ideology continues to underpin how rental housing is provided in Ghana, the AR payment as a market norm will persist. This is exemplified by the current government’s National Rental Assistance Scheme. Consequently, the precarity endured by renters is unlikely to change, irrespective of lifestyle and behavioural adjustments tenants may make (Soaita and McKee Citation2019). Any further increase in Ghana’s housing deficit empowers private landlords, who now hold the largest market share of rental properties, to raise rents while retaining the extended AR payment period. Akaabre et al. (Citation2018) argue that this situation leads to ‘rent-seeking,’ where rental dwellings become limited, competitiveness and accessibility become challenging, and households in dire need of housing compete to confer a monopoly on landlords (p.35). In this context, tenants find themselves disempowered and unable to wield their significant numbers to demand policy change (Government of Ghana Citation2019, p.136).

This line of reasoning also underscores the critical question of tenant agency and the role of estate agents in either challenging or perpetuating the prevailing status quo. Our position aligns with the assertion that even middle-class renters lack the capacity to influence how landlords determine rent or furnish rental properties (Ehwi et al. Citation2021). While we refrain from making empirical claims, there is reason to believe that estate agents, rather than striking a balance between the interests of landlords and tenants, are primarily motivated by consultation fees and agents’ commissions (Akaabre et al. Citation2018). Akaabre et al. (Citation2018) further underscore that estate agents often assist landlords in drafting tenancy agreements, which explicitly define the terms of AR payment. Additionally, Asante and Ehwi (Citation2022) suggest that estate agents have adopted a pre-screening process for prospective tenants, determining who is ‘worthy’ of meeting the landlord and who is not. Collectively, this could suggest that estate agents play a significant role in perpetuating the AR norm and the difficulties it imposes.

That said, it is also worth noting that some landlords, despite their theoretical power, may not be as privileged. Arku et al. (Citation2012), observed that some landlords acknowledged that they earned their livelihood from the rent they collected. Due to the inflationary nature of the Ghanaian economy and their responsibilities towards family members, they act in their self-interest by asking tenants to pay longer AR periods to hedge against inflationary effects on monthly rents. Earlier studies (Konadu-Agyemang Citation2001; Tipple and Willis Citation1992; Yankson Citation2012) have pointed out that, in some cases, landlords reside on the same premises as their tenants, both as a measure of social control and due to their economic precarity.

An interesting observation arises from the claims made by Arku et al. (Citation2012) that landlords continue to demand longer AR periods mainly because most city residents work in the informal sector without fixed incomes. Our study respondents predominantly consist of private formal sector (50.5%) and public sector (39.7%) workers, who arguably are well-paid, have fixed incomes and stable employment. Yet, they also face challenges with AR payment. While there have been suggestions that high-end rental properties developed by real estate developers charge AR for periods ranging from three to 12 months (UN-HABITAT Citation2011), this is the exception rather than the norm, catering to only a tiny fraction of the rental household population (c.f. Ehwi et al. Citation2020). This reinforces the view that the AR payment has become a norm, and landlords pay little regard to the socioeconomic and employment circumstances of prospective renters. It is unsurprising that UN-HABITAT (Citation2011) reaches a similar conclusion, observing that ‘the conditions for charging rent advance (in Ghana) are ignored, with two or three years being demanded up-front as a norm (Italics for emphasis), and the conditions for eviction not consistently applied’ (p.22). It further contends that landlords demand longer AR periods not due to rising rents but mainly because it has become the only practical way for landlords to survive. The aforementioned analysis aligns with the argument by Ehwi et al. (Citation2020) that landlords in the private informal rental housing market in Dansoman, Accra, make no distinction in AR charged between first-time renters who are typically younger, single, lower-income earners with limited social capital, and regular renters who are usually older, married, with two income earners and stronger social capital.

It is also crucial to highlight the role played by existing institutional arrangements, such as the operations of the Rent Control Department (RCD), and the nature of the Ghanaian economy, characterised by low wages and salaries, in sustaining the AR payment norm. According to the Ministry of Works and Housing (MWH), the RCD aims to work ‘cooperatively with landlords and tenants to promote optimal and peaceful resolution of rent matters through education, reconciliation while providing advice on rent matters in accordance with the Rent Act of Citation1963.’ However, it is intriguing that while the Act establishes the office of a Rent Commissioner and other Rent Officers, empowering them to execute the provisions of the law, the RCD is merely a department within the MWH. Analysts who have studied the performance of the RCD unanimously criticise its inefficiency. The UN-HABITAT (Citation2011), for example, observes that ‘from January to September 2010, the RCD received 28,219 cases, of which it settled only 7,073, representing a 25% case settlement rate. It further reveals that the department operates far below capacity with 21 professional staff and 23 District and Regional offices nationwide, instead of 170 districts at the time. It also had no computer, and its email was not included in the general inter-departmental email traffic’ (p.170). Surprisingly, after over a decade, it appears that the RCD is still not adequately set up to perform its functions, with no functioning website and a meagre 770 followers on Facebook. It is intriguing that over several decades of its existence, the RCD had its first-ever press conference on 1 October 2021 (RCD Facebook page Citation2020). Given this precarity in light of the growing housing deficit, we contend that the RCD is incapable of delivering its mandate and is thus implicated in fostering the two-year AR payment norm in Ghana’s rental housing market.

Furthermore, one might have expected that our highly educated and mostly formal sector worker participants would be relatively well-off. However, with nearly 60% expressing difficulties with AR payments, and most explicitly citing employment-related factors such as low incomes, delayed salaries as compounding the pressure, our study reveals how Ghana’s economic landscape exacerbates the harsh realities of AR payments. This economic precarity suffered by these highly educated renters casts doubts on the conceptual soundness of the eligibility criteria used for beneficiaries of the newly introduced National Rental Assistance Scheme (see also Ehwi et al. Citation2021). If even the so-called ‘regular income earners,’ as our study shows, find AR payments challenging and in need of support, it begs the question of how much more assistance is required for the majority who primarily work in the informal sector. This suggests that the current government’s approach to alleviating the financial pressures associated with AR payments is based on ‘ability-to-pay’ rather than ‘needs,’ revealing the influence of neoliberal ideology in shaping housing access and support mechanisms.

Finally, the findings from this study make an important theoretical contribution to sociological institutionalism specifically and the institutional literature more broadly. First, the study demonstrates the origins of (market) norms and the pathways they traverse before becoming entrenched. In our study, AR originated with political-economic policy choices by the immediate post-colonial government which seemed to lean heavily towards tenant rather than landlords (Ninsin Citation1989; Obeng-Odoom Citation2011), followed by a pro-market housing policy orientation which placed the burden of housing supply on the private sector (Arku Citation2009; Government of Ghana Citation2015), aided by unregulated demand and supply interactions in the housing market (Asante and Ehwi Citation2020; Obeng-Odoom Citation2011), and institutional inefficiencies in mediating landlord-tenant relations (UN-HABITAT Citation2011) and entrenched by recent government policy. What this suggests is that norms can originate from both formal or informal institutions and go through different pathways instituted and mediated by both state and non-state actors before becoming entrenched (Rakodi and Leduka Citation2004). Secondly, the study reveals how norms which emerge from arguably an ‘illegality’ can coexist with formal institutions (the Rent Act, Citation1963), and gain legitimacy in recent government policy (Ehwi Citation2019).

This observation builds on the rich literature on the relationship between formal and informal institutions (Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004; Rakodi and Leduka Citation2004; Williamson and Kerekes Citation2011). Notably, it echoes Goodfellow and Lindemann’s (Citation2013) recent call for institutional analysts to recognise the nuanced relational interface between the state and non-state organisations in African settings, which can take the form of institutional hybridity, concordant, and discordant institutional multiplicities. Our study reflects a case of concordant institutional multiplicity, where private landlords aided by estate agents have instituted a norm of charging renters 2-years advance rent, contrary to what state law specifies, and yet the state enacts a policy that recognises and further entrenches this aberration. This case of institutional multiplicity appears to serve the interests of both landlords who perceive they are filling a gap left by the state in delivering housing (see Adu-Gyamfi and Cobbinah Citation2020; Ardayfio-Schandorf Citation2012), and the state, whose actors wish to appear responsive to the plight of tenants (National Rental Assistance Scheme Citationn.d.), and potentially consolidate political power.

Thirdly, our study illuminates how norms engender variegated responses from actors, exemplified by how tenants devise different saving strategies to pay their AR. What this suggests is that, irrespective of how burdensome one finds the norm of paying the AR, compliance cannot be negotiated, owing to the reward and risk relationship. Here, compliance with the norm provides tenants with access to accommodation and relieves them of the obligation of paying rent monthly – something to be treasured in a highly inflationary economy like Ghana, where non-food inflation in December 2022 stood at 49.9% (Ghana Statistical service Citation2023). Risks associated with non-compliance with this norm include eviction and subsequent undesirable outcomes engendered

Moving beyond Ghana’s rental housing market, the study contributes to the extant scholarship on how rental housing markets operate in different regions by shedding light on perhaps an aspect of the rental housing literature that has received limited empirical and theoretical contribution – barriers to accessing rental housing (see Lu and Burgess Citation2023 for how skilled migrants access rental housing in China and Stone et al. Citation2015 for accessing and sustaining private rental tenancies in Australia) and the variegated conceptions and operations of rent deposit schemes across different parts of the world (see Park and Pyun Citation2020; Lee and Chung Citation2010 for different deposit schemes in South Korea)

Limitations

We are cognisant that an online survey hardly generates a representative sample due to the potential exclusion of certain demographic groups, including the less highly-educated, those lacking internet access, and those without electronic devices like laptops and mobile phones (Bhutta Citation2012). Furthermore, owing to the lack of full control over who completes the online survey, the sample could be unrepresentative (Ficker Citation2017). However, we addressed this sampling challenge by incorporating eligibility questions that asked respondents to confirm that they are renting and currently live in Ghana, the failure of which terminated the survey. At the same time, this skewness has also offered an opportunity to study a unique subgroup of renters about whom little is known regarding their housing circumstances. Secondly, in our study, respondents from the Greater Accra region appeared disproportionately represented, making generalisation to the broader renter population impossible. This over-representation is however hardly surprising given that Greater Accra remains the most populated region in Ghana (Ghana Statistica Service Citation2022) and has the most vibrant rental housing market, seen in terms of low rent affordability (Adade et al. Citation2022) and the growing number of containers used as housing (Ghana Statistica Service Citation2022).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we reiterate our argument that Ghana’s ‘infamous’ advance rent (AR) payment has become a norm in the rental housing market due to its recognition by government policy (the National Rental Assistance Scheme) and the disciplinary regime it imposes on renters, leading them to devise bespoke saving strategies to meet this financial commitment even amidst challenges. We have demonstrated that issues with AR payments stem from the extended period of time it covers, affordability concerns, employment-related factors, and limited savings. We contend that addressing this entrenched norm in Ghana requires more than legislation aimed at shortening the AR payment period. It necessitates an understanding of the discursive origins of this norm and the nuanced relationship between the state and non-state actors that has evolved over time to sustain it. Practical interventions should include a re-evaluation of the current political economy of housing delivery, underlying ideological beliefs about housing, and access to it. Moreover, there should be a focus on building the capacity of state and quasi-state agencies, such as the Rental Control Department (RCD), tasked with regulating the rental housing market. Crucially, direct government investment in housing delivery is essential to mitigate the current dominance held by landlords (Ehwi et al. Citation2021; Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richmond Juvenile Ehwi

Richmond Juvenile Ehwi (PhD) is a Senior Lecturer in Town Planning at Oxford Brookes University. He was previously a Research Associate at the Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research (CCHPR) in the Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge, UK where he also obtained both his MPhil and PhD from the same university. His recent research interests include barriers to accessing rental housing, stakeholder engagement in smart cities, the proliferation of gated communities and new cities across Africa, the political economy of land administration and remittance and migrants’ living conditions abroad.

Lewis Abedi Asante

Lewis Abedi Asante (PhD) is a Lecturer at the Department of Estate Management, Kumasi Technical University, Ghana. He holds a PhD in Geography and an MSc in Urbanisation and Development from Humboldt-Universitat zu Berlin, Germany and London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom respectively. His research interests include urban governance, market redevelopment, housing and urban regeneration.

Emmanuel Kofi Gavu

Emmanuel Kofi Gavu (PhD) is a lecturer in the Department of Land Economy, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) Kumasi, Ghana. He obtained his BSc (land economy), MSc (geo-information science and earth observation), and PhD from the KNUST, University of Twente, and TU Dortmund University, respectively. His main fields of teaching, research, and professional interests are the application of GIS in urban management, real estate, and housing market analysis. He has published in the areas of hedonic modelling, housing market dynamics, and real estate education. He presents his research at major real estate conferences and seminars around the world. He is a board member of the African Real Estate Society (AfRES), Vice-Chair of the Future Leaders of the African Real Estate Society (FLAfRES), a member of the Ghana Institution of Surveyors (GhIS), and a member of the Society of Property Researchers (giF) Germany. He is a three-time winner of the IREBS Foundation for African Real Research manuscript prize (2012, 2015, and 2017), and a DAAD and Erasmus Mundus scholar.

Notes

1. See https://unhabitat.org/ghana.

2. See https://www.nras.gov.gh/.

3. The mean monthly household expenditure of Ghc 1071 was computed from the mean annual household expenditure of Ghc 12,857 (see Government of Ghana Citation2019, p.199).

4. The US Dollar – Ghana Cedi Exchange Rate at the time of the data collection was $US1 to Ghc 5.7.

References

- Acheampong R, Anokye P. 2015. Housing for the urban poor: towards alternative financing strategies for low-income housing development in Ghana. Int Dev Plann Rev. 37(4):445–465. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2015.29.

- Acheampong R. 2016. The family housing sector in urban Ghana: exploring the dynamics of tenure arrangements and the nature of family support networks. Int Dev Plann Rev. 38(3):297–316.

- Adade D, Kuusaana ED, Timo de Vries W, Gavu EK. 2022. Housing finance strategies for low-income households in secondary cities: contextualization under customary tenure in Ghana. Hous Policy Debate. 32(3):549–572. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2021.1905026.

- Adu-Gyamfi A, Poku-Boansi M, Cobbinah PB. 2019. Homeownership aspirations: drawing on the experiences of renters and landlords in a deregulated private rental sector. Int J Housing Policy. 20(3):417–446. doi:10.1080/19491247.2019.1669424.

- Adu-Gyamfi A, Cobinnah P, Gaisie E, Kpodo D. 2020. Accessing Private Rental Housing in the Absence of Housing Information in Ghana. Urban Forum. 85:32–67.

- Aduhene DT, Osei-Assibey E. 2021. Socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on Ghana’s economy: challenges and prospects. Int J Soc Econ. 48(4):543–556. doi:10.1108/IJSE-08-2020-0582.

- Adziabah S. 2018. Better public housing management in Ghana: An approach to improve maintenance and housing quality [ Doctoral Dissertation]. Delft University of Technology.

- Africanews. 2018. Cameroon: high rent advance crippling working youths. Africanews. https://www.africanews.com/2018/06/26/cameroon-high-rent-advance-crippling-young-working-youths/.

- Akaabre P, Poku-Boansi M, Adarkwa KK. 2018. The growing activities of informal rental agents in the urban housing market of Kumasi, Ghana. Cities. 83:34–43.

- Alasuutari P. 2015. The discursive side of new institutionalism. Cult Sociol. 9(2):162–185. doi: 10.1177/1749975514561805.

- Al-Hafith O, Satish BK, de Wilde P. 2019. Assessing housing approaches for Iraq: learning from the world experience. Habitat Int. 89(April):102001. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102001.

- Amerio A, Brambilla A, Morganti A, Aguglia A, Bianchi D, Santi F, Constini L, Odone A, Constanza A, Signorelli C, et al, 2020. Covid-19 lockdown: housing built environment’s effects on mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(16):1–10. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165973.

- Andreasen M, McGranahan G, Steel G, Khan S. 2020. Self-builder landlordism: exploring the supply and production of private rental housing in Dar es Salaam and Mwanza. J Hous Built Environ. 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10901-020-09792-y.

- Ardayfio-Schandorf. 2012. Urban Families and Residential Mobility in Accra. In: Schandorf A, Yankson P, Bertrand, editors. ‘Urban Families, Housing and Residential Practices’. Africa, Darkar: Council for the Development of Social Science Research; p. 47–72.

- Arku G. 2009. Housing and development strategies in Ghana, 1945–2000. Int Dev Plann Rev. 28(3):333–358. doi:10.3828/idpr.28.3.3.

- Arku G, Luginaah I, Mkandawire P. 2012. “You either pay more advance rent or you move out”: Landlords/Ladies’ and tenants’ market in Accra, Ghana. Urban Stud. 49(14):3177–3193. doi:10.1177/0042098012437748.

- Asante LA, Gavu EK, Quansah DPO, Osei Tutu D. 2018. The difficult combination of renting and building a house in urban Ghana: analysing the perception of low and middle-income earners in Accra. GeoJournal. 83(6):1223–1237. doi:10.1007/s10708-017-9827-2.

- Asante LA, Ehwi RJ. 2022. Housing transformation, rent gap and gentrification in Ghana’s traditional houses: insight from compound houses in Bantama, Kumasi. Hous Stud. 37(4):578–604. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2020.1823331.

- Asante LA, Ehwi RJ. 2022. Housing transformation, rent gap and gentrification in Ghana’s traditional houses: insight from compound houses in Bantama, Kumasi. Hous Stud. 37(4):578–604. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2020.1823331.

- Asante LA, Ehwi RJ, Gavu EK. 2022. Advance rent mobilisation strategies of graduate renters in Ghana: a submarket of the private rental housing market. J Hous Built Environ. 37(4):1901–1921.

- Bhutta C. 2012. Not by the Book: Facebook as a sampling frame. Sociol Methods Res. 40(1):57–88.

- Braun V, Clark V. 2006. Qualitative Research in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101.

- Brenner N, Theodore N. 2002. Cities and the geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism”. Antipode. 34(3):349–379. doi: 10.1111/1467-8330.00246.

- Budniok J, Noll A. 2018. The Ghanaian Middle Class, Social Stratification, and Long-Term Dynamics of Upward and Downward Mobility of Lawyers and Teachers. In: Kroeker L, O’Kane D, Scharrer T, editors. Middle classes in Africa: Changing lives and conceptual challenges. Cham: Palgrave McMillan.

- Cadstedt J. 2006. Influence and invisibility: tenants in housing provision in Mwanza City, Tanzania. Report. Stokholm, University. Accessed July 5, 2023. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:189161/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Cain A. 2017. Angola’s housing rental market. Johannesburg. http://housingfinanceafrica.org/app/uploads/DW-Angola_CAHF_Angolas-Housing-Rental-Market_February-2017.pdf.

- CAHF. 2018. Understanding and quantifying rental market in Africa: focus note - Senegal. Accessed May 20, 2020. Available at: https://housingfinanceafrica.org/app/uploads/Senegal_Rental_Focus-note-22.08.18.pdf.

- DESA UN. 2019. World population prospects 2019. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2019.

- Dowuona S. 2020. Ghana: landlady gives 3 months rent waiver to tenants due to COVID-19 lockdown. https://africaneyereport.com/ghana-landlady-gives-3-months-rent-waiver-to-tenants-due-to-covid-19-lockdown/.

- Ehwi RJ. 2019. The Proliferation of Gated Communities in Ghana: A New Institutionalism Perspective [ Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Cambridge. doi. 10.17863/CAM.50768.

- Ehwi RJ, Asante LA, Morrison N. 2020. Exploring the financial implications of advance rent payment and induced furnishing of rental housing in Sub-Saharan African cities: the case of Dansoman, Accra- Ghana. Hous Policy Debate. 30(6):950–971. doi:10.1080/10511482.2020.1782451.

- Ehwi RJ, Asante LA, Gavu EK. 2021. Towards a well-informed rental housing policy in Ghana: differentiating between critics and non-critics of the rent advance system. Int J Hous Mark Anal. 15(2):315–338.

- Emerson R. 2015. Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: how does sampling affect the validity of research? J Vis Impair Blind. 109(2):164–168.

- Ficker RD. 2017. Sampling methods for online survey. In: Fielding NG, Lee RM, and Blank G, editors. The sage handbook for online research methods. London: Sage Publications Ltd: p. 162–184.

- Foli R, Ohemeng F. 2022. “Provide our basic needs or we go out”: the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, inequality, and social policy in Ghana. Policy and Society. 41(2):217–230. doi: 10.1093/polsoc/puac008.

- Gavu EK. 2020. Conceptualizing rental housing market structure in Ghana, housing policy debate. Hous Policy Debate. 32(4–5):767–788. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2020.1832131.

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2019a. Ghana living standards survey (GLSS7). Government of Ghana. Accra-Ghana (Vol. 7).

- Ghana Statistica Service. 2022. Ghana 2021 population and housing census volume 3: General report highlight, Accra, Ghana Statistical Service. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://census2021.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/reportthemelist/Volume%203%20Highlights.pdf

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2023. Consumer Price Index (CPI): December 2022. Accessed May 20, 2023. Available at: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/Price%20Indices/Bulleting_CPI%20December%202022.pdf.

- Gilbert A. 2016. Rental housing: the international experience. Habitat Int. 54:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.025.

- Goodfellow T, Lindemann S. 2013. The clash of institutions: traditional authority, conflict and the failure of ‘hybridity’ in Buganda. Commonw Comp Polit. 51(1):3–26. doi: 10.1080/14662043.2013.752175.

- Gough KV, Yankson P. 2011. A neglected aspect of the housing market: the Caretakers of Peri-urban Accra, Ghana. Urban Stud. 48(4):793–810. doi: 10.1177/0042098010367861.

- Government of Ghana. 2014. 2010 population and housing report: Urbanisation. Accra-Ghana: Ghana Statistical Service.

- Government of Ghana. 2015. National housing policy. Ministry of Water Resources, works and housing, Accra. Accessed May 23, 2023. https://www.mwh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/national_housing_policy_2015-1.pdf.

- Government of Ghana. 2019. Ghana living standards survey (GLSS7): main report. Ghana Statistical Service, Accra. Accessed May 20, 2022. Available at: https://www.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/GLSS7%20MAIN%20REPORT_FINAL.pdf.

- Graham L, Williams L, Chisoro C. 2019. Barriers to the labour market for unemployed graduates in South Africa. J Edu Work. 32(4):360–376. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2019.1620924.

- Hall P, Taylor RC. (1996). Political science and the three New Institutions. Polit Stud. 44(5):936–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb003.

- Helmke G, Levitsky S. 2004. Informal institutions and comparative politics: a research agenda. International Handbook on Informal Governance. 2(4):85–113.

- Huisman CJ. 2016. A silent shift? The precarisation of the Dutch rental housing market. J Hous Built Environ. 31(1):93–106. doi: 10.1007/s10901-015-9446-5.

- ILO. 2019. Wages in Africa: recent trends in average wages, gender pay gaps, and wage disparities. Available at: https://webapps.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---africa/---ro-abidjan/---sro-cairo/documents/publication/wcms_728363.pdf

- Jones A, Grigsby-Toussaint D. 2020. Housing stability and the residential context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cities Health. 1–3. doi: 10.1080/23748834.2020.1785164.

- Konadu-Agyemang K. 2001. A survey of housing conditions and characteristics in Accra, an African city. Habitat Int. 25(1):15–34. doi: 10.1016/S0197-3975(00)00016-3.

- Kufuor KO. 2018. Let’s break the law: transaction costs and advance rent deposits in Ghana’s housing market. Global J Comp Law. 7(2):333–354. doi: 10.1163/2211906X-00702005.

- Lee C, Chung E. 2010. Monthly rent with variable deposit: a new form of rental contract in Korea. J Hous Econ. 19(4):315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jhe.2010.09.005.

- Lowndes, V. 2001. Rescuing aunt Sally: taking institutional theory seriously in urban politics. Urban Stud. 38(11):1953–1971. doi: 10.1080/00420980120080871.

- Luginaah I, Arku G, Baiden P. 2010. Housing and health in Ghana: the psychosocial impacts of renting a home. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 7(2):528–545. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7020528.

- Lu Q, Burgess G. 2023. Housing for talents: highly skilled migrants’ strategies for accessing affordable rental housing. 2(4):478–501. doi: 10.1177/27541223231210820.

- Maguire N. 2022. The role of debt in the maintenance of homelessness. Front Public Health. 9:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.810064.

- Malpezzi S, Tipple A, Willis K, Walters A. 1990. Costs and Benefits of Rent Control: The Case of Kumasi, Ghana. In: World Bank discussion papers; no. WDP. Vol. 74, Washington, D.C: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/551371468771628163/Costs-and-benefits-of-rent-control-a-case-study-in-Kumasi-Ghana.

- March JG, Olsen JP. 2006. Elaborating the New Institutionalism. In: Rhodes R, Binder S, Rockman B, editors. ‘The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions. Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 3–20.

- Miller E, Banaszak-Holl. (2005). Cognitive and normative determinants of state policymaking behavior: lessons from the sociological institutionalism. Publius. 35(2):191–216. doi: 10.1093/publius/pji008.

- Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing. 2015. National housing policy. Government of Ghana. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2015-12/apo-nid60737.pdf.

- National Rental Assistance Scheme. n.d. Making renting in Ghana accessible for all. Accessed May 10, 2023. Available at: https://www.nras.gov.gh/.

- New Patriotic Party. 2020. NPP 2020 manifesto. Accra-Ghana: Leadership of Service: Protecting our Progress, Transforming Ghana for All.

- Ninsin KA. 1989. Notes on landlord-tenant relations. Rese Rev. 5(1):69–76.

- North D. 1990. Institutions, institutional changes and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Obeng-Odoom F. 2011. Private rental housing in Ghana: reform or renounce? J Int Real Estate Constr Stud. 1(1):71–90.

- Ofosu-Kusi Y, Danso-Wiredu EY. 2014. Neoliberalism and Housing Provision in Accra, Ghana: The Illogic of an Over-Liberalised Housing Market. In: Asuelime L, Yaro J, Francis S, editors. Selected Themes in African Development Studies. Advances in African Economic, Social and Political Development. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-06022-4_7.

- Olawande OA, Adedapo O, Durodola DO. 2012. Real estate market regulation and property Values in Lagos State, Nigeria. Eur Sci J. 8(28):61–77.

- Olivier de Sardan J. 2015. Practical norms: informal regulations within public bureaucracies (in Africa and beyond). In: De H, Oliver de Sardan J, editors. Real Governance and Practical Norms in Sub-Saharan Africa. Abingdon: Routledge; p. 19–62.