ABSTRACT

Participatory Budget, as a process for democratic decision-making in allocating public funds, has gained traction globally since the initial experiences in Porto Alegre, Brazil in the 1980s. This article analyses the 2022 and 2023 experiences of participatory budget (PB) in the city of Monterrey, Mexico. Based on a comparative analysis of secondary data of Monterrey’s two-year programme, the study illustrates the obstacles and potentialities of implementing PB. Some of the limitations revolve around intergovernmental coordination, spatial limitations and limited impact on changing power relations concerning urban interventions. In assessing the programme’s implementation, we seek to highlight that while participation indeed increased from 2022 to 2023, the conceptualisation of the programme differs from the original one in Porto Alegre, and distribution of projects and resources remains uneven. By critically evaluating Monterrey’s PB initiatives, the article aims to contribute to the broader discourse on the complexities and challenges of participatory budget implementation.

1. Introduction

Participatory Budget (PB) is a process, where a local government involves its citizens in choosing how certain amounts of municipal resources should be allocated. Considered a form of participatory democracy in public management (Cabannes Citation2015), the participatory process makes possible a more equitable, rational, efficient, and transparent use of public resources, resulting in the strengthening of the municipal government’s relationship with its citizens. The PB was born in 1989 in Brazil to address the demand for a democratic, open, and transparent government as the country was emerging from a military dictatorship. This process has continuously evolved and spread worldwide. According to Cabannes (Citation2004), the Participatory Budget can be understood in three distinct historic stages. The experimentation stage from 1989 to 1997, which was implemented in Porto Alegre (1989), Belo Horizonte (1993), and Santo André in Brazil, and Montevideo, Uruguay. The second stage, from 1997 to 2000, the ’Brazilian Propagation’ due to the adoption of the model in over 130 cities across Brazil (Cabannes Citation2004). Finally, from 2000 onwards, the expansion and diversification stage, characterised by the implementation of the Participatory Budget in multiple Latin American cities and some European cities. Even when participatory planning emerged as a radical democratic project in the city of Porto Alegre, led by the left (Cabannes Citation2004; Aziz and Shah Citation2021), the fact that it has now been implemented in over 1,500 municipalities in diverse countries and under different political ideologies, highlights the validity and importance of this initiative.

This document examines the implementation of a participatory budget exercise in the city of Monterrey, Mexico, during the years 2022 and 2023. We use the concept of invited participation (Cornwall Citation2017; Miraftab Citation2009), to critically look at the experience of PB, examining if the implementation pushes forward objectives of equity and social inclusion, or increases citizen participation in a tokenisticFootnote1 manners. Within the PB experience, we aim to explore its potential for a reconfiguration of power relations that extend ‘the practice of democracy beyond the sporadic use of the ballot box’ (Cornwall Citation2017, p. 2), to address underlying inequalities. We highlight the limitations of the process in Monterrey, including challenges related to intergovernmental coordination and financial restraints, as well as the positive outcomes resulting, such as increased awareness and visibility of the program, and improvements in participation during both exercises. In assessing the programme’s two first editions, we found that participation indeed increased from 2022 to 2023. However, the conceptualisation of the programme differed from the original aims of the Porto Alegre experience, as distribution of projects and resources remained uneven.

The overarching question guiding our study is the following: what are the main challenges of the PB implementation in Monterrey and how does the programme implementation promote equity in resources redistribution and social inclusion in participation?

The paper is structured in five sections. The following section offers a brief overview of the Participatory Budget, as conceived in Brazil, how and where it has been implemented, and the main characteristics of this process. This is followed by an overview of experiences of PB in Mexico. The third section presents the research methodology based on a case study of participatory budget implementation in Monterrey, Mexico, along with secondary data analysis, such as operational documents of the programme and presentationsFootnote2 by key programme stakeholders. The fourth section discusses the main findings relating to how participation increased in the two editions of the programme and a discussion regarding the underlying objectives of PB. The final section presents the pending challenges and opportunities for implementing a more socially effective participatory budget in Monterrey.

2. Participatory budget: a brief background

The establishment of participatory budgets in Latin American cities has emerged from the necessity for open and democratic governmental processes (Fundar Citation2012). Originated in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 1989, as a process for redistributing the city’s public resources in favour of the most vulnerable groups through participatory democracy (De Sousa Citation1998), the PB aimed of ‘bringing to life practices that were both prefigurative of the societies we want and also part of a strategy for achieving that society’ (Baiocchi and Ganuza Citation2014, p. 30). At its core PB is defined as how ‘’ordinary citizens’ should have a direct say in public budgets that impact them’ (Baiocchi and Ganuza Citation2014, p. 30).

Dominated by a military dictatorship that ruled for 21 years since 1964, Brazil faced multiple obstacles for the construction of a civic culture, the exercise of rights, and autonomous popular participation (De Sousa Citation1998). During the 1970s the country experienced an economic crisis alongside an incipient democratic transition triggered by a strong social and political mobilisation that led to debates that positioned the democratisation of political life and the construction of citizenship at the centre of the national political agenda (De Sousa Citation1998). In this context, an innovative experiment in popular participation in municipal governments, such as participatory budget (PB) took place. The success of the pilot program of the PB in Porto Alegre can be attributed to the establishment of the Department of Popular Administration, whose objective was to guarantee the participation of citizens in the distribution of resources and the definition of investment priorities (Souza Citation2001). In the first editions of the PB, the citizens’ priorities were embodied in projects, which included road paving, drainage, housing, and community equipment (Souza Citation2001).

2.1. Latinoamerican context

The PB has been replicated in various countries worldwide, with notable experiences in Latin America. From 1990 to 2005, Montevideo, Uruguay implemented a PB as part of the decentralisation process with social participation (Montecinos Citation2012, p. 6). During this stage, the PB was evaluated, considering factors such as participation levels, decision-making procedures, and budget preparation. In the second stage (2006 to present), new operational rules were introduced for the participatory process, and council meetings were held to implement the selected proposals.

After Uruguay, other local governments in Latin America began carrying out participatory budgeting programs (Fundar Citation2012). Colombia introduced its first PB program in 1990 in Bogota, followed by Medellín in 2004, and El Salvador and Peru in 2000. In Chile, 37 municipalities implement participatory budgets annually, 28 in Uruguay, and 234 municipalities and municipal districts in the Dominican Republic. Latin America accounts for approximately one-third of all PB programs globally (Fundar Citation2012). Despite these achievements significant challenges remain; national PB policies have generally struggled to effectively promote citizen participation at the local level, ensure fiscal transparency, and establish efficient municipal governance. Overall, there have been few changes to the program’s prescriptive implementation globally. Aziz and Shah (Citation2021) have outlined five stages for implementing PB. The first stage involves dividing the geographical region into districts, allowing citizens to vote on projects within their communities. In the second stage, preliminary proposals are generated through neighbourhood meetings. These proposals are developed and often undergo a feasibility check in the third stage. Moving forward, rounds of deliberation are held to finalise and reach agreements on a selected number of proposals. Finally, the last stage calls for the community to vote on the proposals (Aziz and Shah Citation2021).

2.2. Mexican context

In Mexico, pre-Hispanic cultures, such as the Zapotec, developed systems in which the role of the citizen in city-making was governed by a ‘Tequio’, a socio-political structure that involved collective labour practices in Oaxaca, based on solidarity and reciprocity, where members voluntarily participated in projects for the benefit of the community. Since the fourteenth century, citizens of these cultures actively contributed to their community as a fundamental right, participating in communal activities necessary to provide services and benefits for the entire community. In this system, citizens could design and actively participate in creating projects that would benefit the community as a shared city-making. Through colonisation, industrialisation, and subsequent globalisation, these collective systems have been lost within national governance structures. Only small communities have managed to preserve ‘Tequio’ as a fundamental element of their cultural wealth, continuing to permeate within Oaxacan villages to this day.

Echoing some of these ancient participation mechanisms, participatory budgets have been implemented in Mexico since the early 2000s to promote invited citizen participation. They have been adopted by numerous municipalities across the country, with Mexico City one of the pioneering cities to implement PB in 2011. The PB process in Mexico City involves the collaboration of adjacent municipalities and neighbourhoods, where each municipality allocates a percent of the total annual budget exclusively for participatory budget initiatives. To monitor progress and identify improvement areas, the city conducts annual Citizen Consultations after budget implementation.

In the state of Jalisco, since 2016, a Metropolitan Participatory Budget has been implemented in the cities of Tlajomulco, Guadalajara, Zapopan, and Tlaquepaque. Zapopan has emerged as a prominent municipality in the national PB landscape. They have conducted an annual program with a notable increase in participation. In 2016, 52683 people participated, while in 2020, the number rose to 77,553 participants (Government of the State of Jalisco Citation2016). Other states with a participatory budget are Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Coahuila, Durango, Hidalgo, Nayarit, Puebla, Quintana Roo, Nuevo León, and Sonora. The allocation of budgetary percentages for PB implementation varies across states based on PB regulations for each state.

At the national level, García Bátiz and Téllez Arana (Citation2018, translation by authors), conducted an analysis of the implementation and evolution of PB in Mexico, and they conclude that ‘PB is established as a process with great democratic objectives but with participation processes that contribute little to fulfil them’; and continue saying that PBs predominate with dynamics of very low scope and intensities, which give preference to consultation, do not attempt to be representative, inclusive or redistributive and do not transcend decision-making (García Bátiz and Téllez Arana Citation2018).

As will be discussed in the case of Monterrey and for Mexico, rather than promoting more sustainable change and shared power in decision-making processes, PB has consolidated as ‘an attractive and politically malleable device by reducing and simplifying it to a set of procedures for the democratisation of demand-making’ (Ganuza and Baiocchi Citation2012, p. 1).

2.3. Local context

In 2016, the state of Nuevo León enacted its first Citizen Participation Law which laid the foundation for implementing the participatory budget processes in different State municipalities. Currently, the PB is active in four municipalities: San Pedro Garza García (2019), Monterrey (2022), San Nicolás de los Garza (Citation2022), and Pesquería (2023). In most of the municipalities, only citizens over 18 years old, the legal age in Mexico, can participate in PB processes, except for San Pedro Garza García, which allowed in 2023 the participation of children over nine years old through their vote (Municipality of San Pedro Garza García Citation2023, p. 97)

In recent years, San Pedro Garza García in Nuevo León emerged as a national benchmark for PB including innovation in public policies. While it is acknowledged that the official implementation of the PB took place in 2019, Rodríguez Larragoity (Citation2013, p. 35) demonstrated that participatory budget exercises have been conducted in San Pedro since 2001. The PB process has been adapted and modified over the years. Initially, the program lacked a legal basis. This led in 2003 to the elaboration of a Regulation of the Participatory Budget and an Operating Manual which established that the program was based on the principles of solidarity, subsidiarity, common goods, responsibility, citizen participation, and transparency. The exercises sought to change paternalist and top-down attitudes from the 1990s public policies to a horizontal approach in which citizens took centre stage. The program received the equivalent to five percent of the total municipal expenditure budget. This was allocated among different sectors, prioritising factors such as property tax compliance, the number of properties in each sector, the presence of constituted neighbourhood assemblies, and voluntary contributions from residents.

During the 2006–2009 administration, the program continued to operate but faced two challenges: the insecurity situation, and the economic and financial crises triggered by the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States. This affected the program´s operation, leading to a reorientation of budget priorities. In the 2009–2012 administration, the program was repealed entirely to focus on strengthening citizen security at municipal level.

During 2012–2015, the PB program was re-established, with a reduced budget. Additionally, five investment categories were defined: community, education, organised civil society, sports, and youth. During the 2015–2018 administration, the PB program was kept intact with the assistance of the Regulation of 2013. This regulation proved crucial in ensuring the program´s continuity, as it provided the legal framework to prevent its dismantling (Rodríguez Larragoity Citation2013).

With the arrival of the first non-partisan mayor in 2018, the program was reinstated under the name ‘Decide San Pedro’, and introduced four changes to the process: an increased budget, from $30 million Mex$ to $100 million MX$, the inclusion of sectoral projects in addition to the neighbourhood projects, the implementation of a digital platform for collecting proposals and voting projects, and the use of co creation workshops as a complementary strategy in the deliberative process (Garza, Citation2020).

The experience in San Pedro Garza García is essential for understanding the origins of PB implementation in Monterrey. The modifications the program in San Pedro experienced since its inception in 2001 laid the foundations for the participatory budget program in Monterrey, where PB has been implemented on two occasions. Through several workshops, knowledge was transferred from San Pedro to Monterrey to develop the legal basis and structure of the programme in Monterrey. Expectations for participation were high; however, ‘the preconditions for equitable participation and voice are often lacking within them’ (Cornwall Citation2017, p. 2).

As these cases show, and several authors have noted (Wampler Citation2000; Souza Citation2001; Cabannes Citation2004), PB holds remarkable potential benefits, particularly for the Latin American context, while being wary that participatory budget should not be considered ‘a neutral technical instrument´ (Goldfrank Citation2006, p. 6). Rather, PB can achieve many objectives, like deepening democracy, by promoting citizen participation of historically excluded groups, redirecting public resources and providing services to underprivileged neighbourhoods (Goldfrank Citation2006; Marquetti Citation2002; Nylen Citation2003). Similarly, other advantages are the possibility to include and democratise existing civil organisations and encourage the creation of new ones -echoing Cornwall’s (Citation2017) invited and invented spaces (Abers Citation1996; Baiocchi Citation2001; Goldfrank Citation2006), increase transparency and accountability by reducing clientelism (Abers Citation1996; Wampler Citation2004 in Goldfrank Citation2006).

As the experience from Monterrey will show, the spaces opened for participation might be seen as innovative at first, but ‘are often fashioned out of existing forms through a process of institutional bricolage, using whatever is at hand and re-inscribing existing relationships, hierarchies, and rules of the game’ (Cornwall Citation2017, p. 2), thus Involving those often excluded from participating remains a challenge. We argue that these characteristics of participation are blatantly found in the implementation in Monterrey, where the aim is to increase participation in a programmatic and prescriptive manner, resulting in a tokenistic approach to participation and a limited impact on changing power relations.

The following section introduces the methodology implemented to approach this case study and the main characteristics, challenges, and opportunities of the programme implementation in Monterrey, shedding light on the cumbersome, obscure, and dynamic processes of PB in the city.

3. Methodology

The qualitative analysis is based on a case study approach, and the data gathered includes policy document analysis, open source data, and presentations by four key program stakeholders from the Secretaria de Innovación y Gobierno Abierto del Municipio de Monterrey (Monterrey’s Municipality Secretariat of Innovation and Open Government, SIGA). Mainly, the policy document analysis was based on the consultation of the Regulation of Participatory Budget of the Municipality of Monterrey and the Operative Manual of the Participatory Budget to understand the structure and operational scope of the program. Also the Report of the First Participatory Budget 2022 as well as data available on the participatory budget website ‘Decidimos Monterrey’ to analyse the main results of the PB and compare 2022 and 2023 editions. Similarly, GIS qualitative and quantitative information about the projects proposed, votes submitted, and the winning projects, was recovered and produced to compare the results of 2022 and 2023 implementations, along with demographic and socioeconomic data analysis to characterise the beneficial population.

A stakeholder analysis was carried out to find out the main power relations that condition the implementation of the program. Highlights of this analysis are briefly introduced in the following section.

The analysis of the Participatory Budget Program focused on examining interactions among key stakeholders throughout all phases of the system. The program’s mission was formulated at municipal level to promote organised and accountable citizen participation in allocating public resources. Presentations by a member of the Coordination team and an analysis of the Participatory Budget Regulations helped establish actor networks, showcasing their interactions during the various stages of the participatory budget process, as well as understanding the programme´s objectives and some of its implementation limitations.

3.1. Key findings: tracing the paths of participatory budget in Monterrey

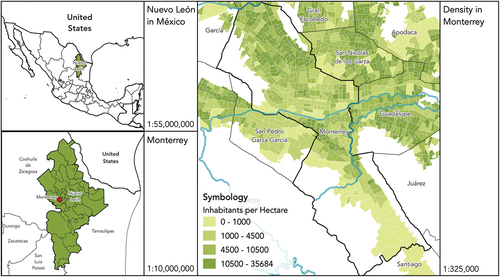

Monterrey, located in the northeastern part of Mexico (), is the capital and largest city of the state of Nuevo León, with a population of 1,142,994 and an extension of 32,465.7 hectares (INEGI, National Institute of Statistics and Geography Citation2020). Monterrey is part of the Metropolitan Area, among 13 conurbated municipalities, and the second-largest Metropolitan Area in the country, with around five million inhabitants (INEGI Citation2020). Monterrey is a major commercial, and economic centre and considered Mexico’s industrial hub due to its highly productive and skilled workforce. According to the Urban Competitiveness Index of 2022 by IMCO (Mexican Institute for Competitiveness), it ranks first in competitiveness among Mexican cities with a population of over 1 million people, attributed to its strong economic performance and innovative practices.

Despite its economic strengths, the city of Monterrey and its conurbations face significant urban development challenges. These include deficient urban planning, poor air quality, insufficient green areas, deficient public transportation, congestion, road insecurity, improper waste management, inadequate coverage of essential services, deteriorated public infrastructure, and accelerated urban expansion (Carpio et al. Citation2021). From 1990 to 2019, the metropolitan area increased by 2,6 times from 30,761 to 80,962 ha, yet the population only grew 1,8 times (Carpio et al. Citation2021). Moreover, the city of Monterrey exhibits significant socio-spatial inequalities.

The PB programme in Monterrey has been implemented on two occasions, in 2022 and 2023, to increase participation by the government, as well as democratise the use of public resources, providing the opportunity for citizens to decide how five percent of the proceeds from the previous property tax year are spent.

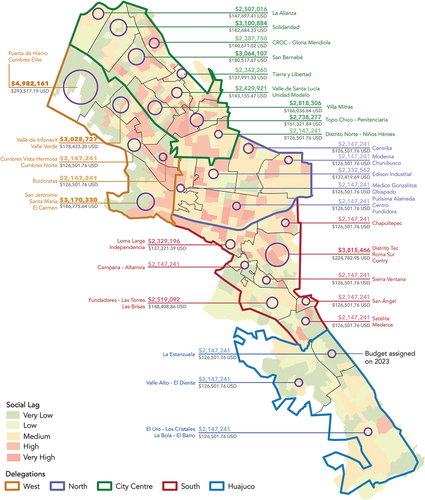

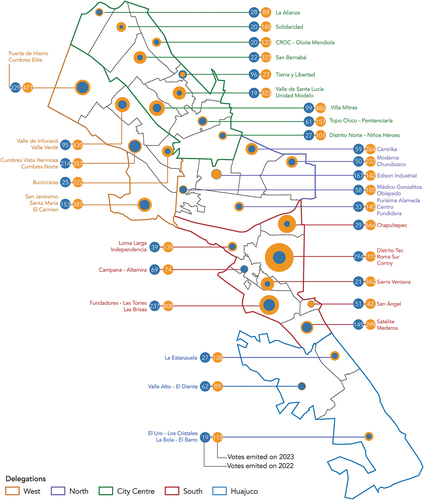

According to the Regulations of Participatory Budget of Monterrey, Nuevo León (Gobierno de Monterrey, Citation2021), citizens, through the proposal and voting of projects in each of the 30 sectors of the program, choose projects to improve their communities (Gobierno de Monterrey, Citation2021). The main objective, according to the policy documents consulted, is promoting the participation of the neighbourhood assemblies and citizens in the decision-making that impact their community through the allocation of a part of the Municipal Budget Expenditures; in an ‘organised and co-responsible way’ under the core principles of participatory democracy, social inclusion, equality, co-responsibility, sustainability, efficacy, efficiency, accountability and transparency (Gobierno de Monterrey, Citation2021: 6–7). Some of the characteristics of the program’s operational basis are outlined below. They shed light on the territorial distribution of participating districts (), project categories, participation modalities, main stakeholders, financial and feasibility processes, and implementation work.

Table 1. Delegations and sections.

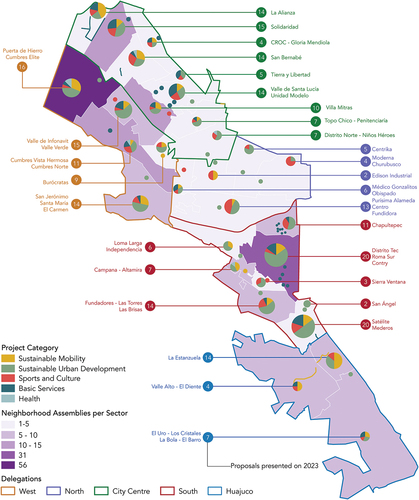

To implement the PB, the Secretariat of Innovation and Open Government (SIGA), along with the Municipal Institute of Urban Planning of Monterrey (IMPLANc), divided the municipal territory into five districts and subdivided into 30 urban sectors (an average of 150 neighbourhoods each), considering the amount of the population that is benefited and the socio-economic needs of AGEBSFootnote3 to define their grouping. In each of the 30 sectors, individuals over the age of 18, living in Monterrey, and who have an INEFootnote4 or residence letters in the municipality may participate in the PB exercise of the sector where they reside. This means 30 participatory budget projects are carried out yearly, with one winner per sector. The districts and sectors can be seen in .

The categories used in the 2022 and 2023 PB are the following:

Sustainable Mobility

Sport and Culture

Basic Services

Sustainable Urban Development

Health

However, these categories do not have a description or clear parameters of what they encompass, blurring which elements are considered in each category, making them susceptible to individual perception. These categories are not restrictive; according to officials, the proposals can be part of more than one category and can be changed according to the criteria of the evaluating official.

3.2. Participation

Citizens can participate directly in the PB by two means: by proposing projects and/or voting for a project. Although it is possible to participate during the implementation process through neighbourhood assemblies and District Councils, there are no clear guidelines for this phase. According to the Regulation Participatory Budget of the Municipality of Monterrey (Citation2023, p. 16–17), to participate, citizens on an individual basis have to register themselves on the website (https://decidimos.monterrey.gob.mx/.) to be able to present project proposals or vote for a project the only way to propose a project is through the website.

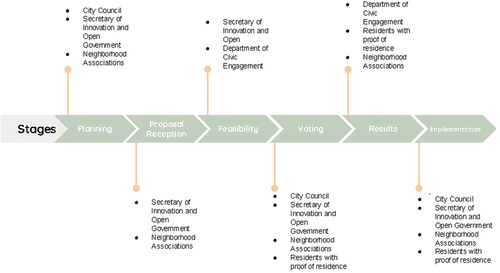

There is significant participation of different entities due to their influence and dependency on the program at different stages ():

Neighbourhood Assemblies: Independent from government organised assemblies of residents from various neighbourhoods within the municipality that represent and advocate the specific needs of their communities.

Secretariat of Innovation and Open Government of Monterrey (SIGA): Responsible for enhancing and encouraging participatory processes in the city, including Participatory Budget.

Secretariat of the City Council: Tasked with setting the public agenda, inviting citizens to participate, and serving as a guiding axis in joint decisions with other secretariats for the Participatory Budget process.

Strategic Projects Coordination: Managing strategic projects within the Secretariat of Innovation and Open Government in Monterrey, including the implementation and participatory processes of the Participatory Budget Program.

City Council: Responsible for making decisions at the municipal government level in Monterrey, setting budgets, and continuous programs, which directly impact the Participatory Budgeting Program.

These actors play a crucial role in the program and their active participation is essential to achieve effective citizen engagement and fair allocation of public resources for the benefit of the local community.

In line with Monterrey PB Regulation (Citation2021: 8), the budget assigned for the program must be greater than 5% of the property tax collection from the previous year. In the first PB edition in 2022, the program had a budget of $66,961,669.00 MX$ (roughly $3,908,116.25 US$) (Dirección de Participación Ciudadana Citation2022, p. 4).

In the second edition of 2023, the budget was $75,961,002.41 MX$ ($4,433,348.50 US$) (Dirección de Participación Ciudadana, Citation2023) (see below).

Table 2. Budget comparative (2022 vs 2023).

With the available budget, each project must have an investment greater than 22,317 UMAS per day, equivalent to $135,069.03 US$. Likewise, the budget for each proposal can be increased with the remainder of the budget once it has been divided among the 30 sectors. According to Article 30 from PB Regulations, these remainings are distributed among the sectors considering the following:

45% based on the compliance of previous Property Tax payment

40% based on the number of people who benefited.

15% based on the number of formally constituted Neighbourhood Assemblies.

In practice, under these rules, some disparities can be observed within sectors.

3.3. PB stages and main findings

During the planning phase, effective communication is crucial. Neighbourhood assemblies are key advocates and intermediaries between the municipality and residents. Deliberative processes are essential in the PB program, particularly during the planning and proposal reception stages. Robust proposals that accurately address community needs and enrich perspectives by ensuring minority voices are included are incentivised, which could result in more equitable proposals. Physical modules in 21 libraries and 30 mobile units were installed for proposal generation; however, there was limited guidance by the authorities on strengthening or developing feasible proposals.

Before projects are put to a vote, public administration agencies assess their technical, legal, and budgetary feasibility. Projects must meet specific requirements, such as being situated in municipal public spaces and adhering to sectoral budgets. In the 2023 PB Program, 108 out of 280 proposals were rejected for not meeting these criteria. Unfortunately, there is currently no formal process for participants to revise and resubmit their proposals for future consideration. Furthermore, participants lack crucial information on budget parameters, hindering their ability to present viable projects for voting.

Citizens can vote on the website after successfully registering. Likewise, voting boots are installed around the municipality where citizens are assisted in casting their vote digitally or through a ballot that contains the name of the project, the name of the citizen that proposed it, and a brief description. However, digital voting is encouraged. After the voting period, votes are verified to prevent duplicate votes cast by the same person; then, the votes are counted, and the winner projects are published on the website.

When a project is selected, exploratory walks involving neighbours and members of Monterrey’s citizen participation office take place. The Municipal Council of the Participatory Budget oversees budgeting, contracting, and project implementation processes. However, the regulation lacks a clear methodology outlining participation in site visits and providing support for consultation, design, or diagnosis.

This section described the particularities of the Participatory Budget in Monterrey, showing the constraints of the implementation process as a consequence of lack of planning and in some cases, clear rules of the game, specifically on the feasibility and evaluation of proposals. The following section compares the PB implementation in 2022 and 2033, followed by a detailed analysis of the 2023 PB. It critically examines the impacts and scope of the programme regarding participation, type and location of projects approved, and overall, if the objectives of the programme are being met; presenting several drawbacks and areas of improvement. The main findings from this comparative analysis will guide the final discussion.

3.4. Comparison 2022–2023

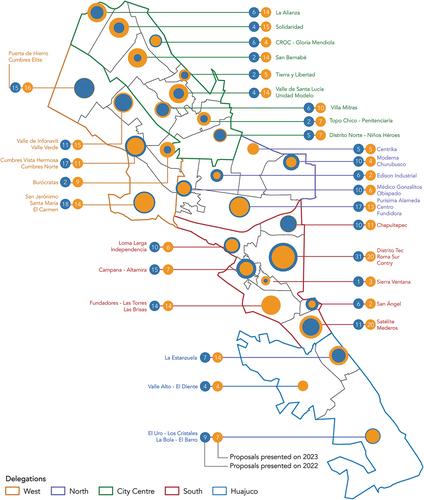

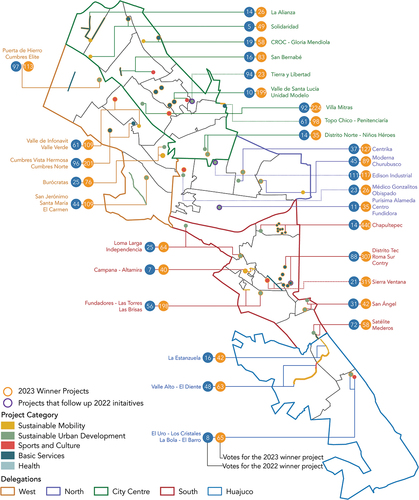

The PB Program of Monterrey was first conducted in 2022, from May to July. In this edition, 266 proposals and 2,409 votes were cast. The 2023 edition took place from October 2023 to February 2023. It aimed to schedule the voting period for January, the month when most property taxes are collected. This strategy intended to increase voter turnout by installing PB modules next to property tax collection centres to inform and invite the citizens to participate through their vote for a project. This strategy was successful as proposals increased by 10.2% (with 293 proposals), while the number of votes increased by 273% (with 8 982 effective votes). There was a considerable increase in the number of proposals in most of the North Delegation sectors and in some sectors of Huajuco and South Delegations (). This increase relates to the additional efforts made to instal itinerant modules to encourage citizens to participate through their proposals and assist them with the submission.

In both editions, almost half of the proposals corresponded to the Sustainable Urban Development category with projects related to park rehabilitation, recovery of public spaces, cisterns for park irrigation, and reforestation of green areas (). Similarly, 20% of the proposals related to the Sustainable Mobility category with projects of safe crossways, sidewalks as well as pathways and stairs in informal settlements; while around 18% of the proposals were about Sports and Culture with projects of creation and renovation of sports facilities, cultural and community centres. The share of proposals by categories reflects in some way the primary needs of Monterrey’s society, where there is a lack of quality public spaces, sports, and culture facilities, and safe pedestrian infrastructure in a city designed and developed for private car mobility.

Table 3. Project categories.

Between 2022 and 2023 editions, there was a slight increase in the projects rejected for not complying with the feasibility revision. In 2022, 39% of the proposals received were rejected, while in 2023 it rose to 41%. As mentioned before, there are no mechanisms for citizens to generate more feasible proposals or have access to guidance from officials.

Regarding voting, in 2023, there was an increase of 273% on effective votes compared to 2022. There was a notable increase in the votes casted per sector, territorially, with an increase ranging from 214% to 2196.5% per sector (see ).

In both editions, the average age of the voters was between 50 to 60 years old. In 2022 and 2023, the votes by women represented 58,3% and 57,6%, respectively. This might reflect the limited diversity of viewpoints in the process, which impacts the satisfaction of a broader range of needs.

Regarding the winner projects, the territorial proximity between them stands out, and in some cases, the 2023 winner projects followed up 2022 initiatives, as is the cases of Tierra y Libertad, Edison Industrial, Purísima Alameda-Centro-Fundidora and Distrito Tec-Roma Sur-Contry sectors (). According to presentations by programme coordinators, these follow-up projects are encouraged as the projects proposed in the first edition were too expensive to be covered by the budget assigned, so it was necessary to break down the project into phases.

In 2023 the programme had a low credibility as perceived by participants, arguing that calling for a second edition was contentious as only one out of 30 winner projects from 2022 were completed by the start of the 2023 edition. However, citizens’ participation was not affected. This might be related to a lack of communication from the SIGA secretariat, where the progress of work was not communicated properly to participant communities.

3.5. 2023 PB analysis

In the 2023 Monterrey’s Participatory Budget edition, the levels of participation in terms of proposals and votes increased considerably from the previous exercise. The number of submitted proposals varied considerably between sectors. The sectors with the most submitted proposals were Distrito TecFootnote5 - Roma Sur – Contry with 20 proposals, Satélite – Mederos, 20 proposals, Puerta de Hierro – Cumbres Elite with 16 projects, and Solidaridad with 15. A comparative analysis of Neighbourhood Assemblies per sector in early 2023 shows a correlation between the number of organised neighbourhoods and the number of proposals submitted. Conversely, some sectors had less than five neighbourhood assemblies but participated through proposals at the same level as the ‘most organised’ sectors, just as the sectors in the North and City Center delegations.

The sector with the highest participation was Distrito Tec, Roma Sur, and Contry with 1772 people who participated in the voting of projects; this may be due to how in the last decade, citizen participation in public decision-making has been encouraged through the Distrito Tec initiative. The second sector with the highest voting participation was Chapultepec, with 666 votes, and thirdly Sierra Ventana, with 342 votes cast.

This implies two issues. On the one hand, the sectors with the higher participation (measured in the number of votes cast) are some of the most affluent zones in the Metropolitan Area, so increased participation might be related to more time availability or shorter working hours corresponding with more privileged sectors of the society. On the other hand, the higher participation sectors are also the ones where most of the Neighbourhood Assemblies are located, meaning that neighbours might know each other and get organised.

Among the proposals, the projects related to Sustainable Urban Development in most sectors stand out (see ); Basic Services in the North Delegation Sectors; and the Culture and Sports projects in the Center and North Delegation (). As suggested in the PB literature, one of the strengths of PB is ‘allowing an “inversion of priorities”’, not only in social and political terms but also in territorial terms. This means that PB will tend to direct public resources towards usually excluded areas and neighbourhoods (Cabannes Citation2004, p. 39). In Monterrey, the case seems to be quite the opposite; the less excluded sectors are the most benefited ones.

Figure 7. Proposals, winner projects and neighborhood assemblies 2023.

Table 4. Share of the proposal’s categories.

If we contrast the sectors of Monterrey’s PB with the CONEVAL Degree of Social Gap (2020), some neighbourhoods appear homogeneous in socioeconomic terms such as Puerta de Hierro-Cumbres Elite with a Low or Very Low degree of social lag. This disparity between homogeneous sectors with low social lag and sectors with medium or high social lag may imply an advantage for the most privileged sectors over the rest since a sector with these characteristics tends to have a higher property tax payment rate and consequently obtains a higher budget item even though there may be sectors with more needs.

4. Obstacles and possibilities for participatory budget in Monterrey

As with other experiences of PB around the globe, the implementation of the programme in the city of Monterrey faced many challenges, which can be explored in two dimensions. Firstly, the tangible challenges and implementation constraints of the programme within the municipal administration, including budgetary and time frame constraints, organisational issues, continuity of the programme across administrations, and spatial delimitations, among others. Secondly, intangible challenges which correspond to what Cabannes (Citation2015, p. 257) argues: ‘… while in most cases PB improves governance and the delivery of services, it does not often fundamentally change existing power relations between local governments and citizens’. The outcomes of this experience remain technically over-determined, and the decision-making of participants is peripheral to local power (Cabannes Citation2015); while participatory budgeting succeeded to some degree in increasing invited citizen participation, there are important limitations to changing power relations.

4.1. Challenges and constraints inside the municipal government

4.1.1. Budget limitations

One of the salient issues is that the base budget of $135,069.03 US, implies a predefined magnitude of the projects that might be implemented. Smaller tactical projects might be rejected if the implementation does not translate to spending the available budget. Or, on the contrary, the project proposal might be forced to reach the costs for participation, spending on unessential concepts, or hampering the feasibility review. Another issue is the allocation of the exceeding budget to higher paying tax rates neighbourhoods, which are higher income areas that generally have infrastructure and equipment needs met. Though it is established on the regulation that the remaining funds can be transferred to other areas, neighbourhoods seek to spend all of the available funds on-site.

4.1.2. Organisational and implementation constraints

The coordination between secretariats within the municipal government was one of the main challenges of the PB, as each secretariat in charge of different stages of the project cycle was not clear on procedures from feasibility to project reception and evaluation, and from voting to implementation. Additionally, we found that decisions on feasibility and approval of proposals fell entirely on the judgement of the official reviewing it without the possibility of challenging the decision. Hence, decisions were taken unilaterally and lacked clarity, as participants were not provided with any feedback. This is a potential area of improvement for the PB in Monterrey, as the way of communicating the approval or rejection of proposals must be reconsidered to avoid demotivating participation and turn the feedback process into a learning experience.

4.1.3. Spatial limitations

The territorial delimitations established by the programme do not represent the nuances in terms of spatial differences, such as population sizes and density, community needs, and urban morphology. For example, in the Uro district, there were only nine projects submitted in 2022 and seven projects in 2023. The particularities of this city area highlight the need for shared public green spaces. In other cases, there were winning projects in the same neighbourhoods, which might be good for localised neighbourhood improvement. Still, it also means that more resources are allocated to the same areas instead of spreading them to other neighbourhoods. Our analysis found that the ‘one size fits all’ approach does not address the complexity of the city. For example, in the Huajuco and the western parts of the city, the housing complexes are closed neighbourhoods that already have neighbourhood assemblies and hence are more organised, but the implementation of projects might not be open for people who do not live in the area.

The projects evidenced socio-spatial fragmentation, working with municipal limits, and the territorial reach of the projects. For example, two sustainable development projects, or public park interventions, in Edison Industrial and Parque Rube remain disconnected while spatially close to each other and close to the sector limits; hence, a larger part of the sector remains unattended. Moreover, when a project is located within municipal limits, the organisation constraints are increased due to a lack of coordination between municipalities, enhancing existing spatial and administrative fragmentation.

4.2. Changes in power relations: promoting equality and social inclusion?

Intangible aspects relate to how power relations are still unchanged by PB in these early stages. A strong critique made of these programmes sustains that in the implementation of PB globally, ‘the communicative dimension has travelled well, but, with very partial exceptions, the empowerment one has not’ (Baiocchi and Ganuza Citation2014, p. 32). Empowerment is harder to achieve since PB is usually applied in a prescriptive manner that risks being ‘only peripherally connected to centres of power, and instead becomes linked to small discretionary budgets, bound by external technical criteria’ (Baiocchi and Ganuza Citation2014, p. 32).

This article has illustrated that, in the case of Monterrey, emancipation (Gherghina et al., Citation2023; Dodds and Paskins Citation2011), or the transition from a top-down to a bottom-up approach of city making is still elusive and very much outside the scope of the programme at this stage. It should be noted, however, that the programme has successfully increased citizen participation, and in some of the districts where PB was implemented, the programme has been fostered through the creation of invited participation and the formalisation of invented participation (Miraftab Citation2009). This somewhat echoes the origins of the programme, as the ‘experience of PB in highly unequal societies such as Brazil should be valued more for its provision of the citizenry to formerly excluded groups in society rather than for the material gains it may bring’ (De Souza Citation2001, p. 184).

In terms of addressing systemic inequalities the programme has a very limited impact even within the sectors in Monterrey, citizen participation and project submission are increased for those that are already better off than other more marginalised areas in the city. This relates to issues of communication strategies and visibility of certain historically segregated communities, implying that inequalities are encroaching rather than being addressed. Similarly, the issue of allocating more budget to higher paying tax rates within the city means that the programme incentivises the participation of higher income neighbourhoods, what Rumbul et al. (Citation2018) have referred to as elite capture and co-optation of the participatory budget. As Cornwall (Citation2017) argues, due to the political ambiguities of participation, it is essential to understand how, by whom, and why are spaces of participation being opened and filled. In other words, being critical of why participatory budget has been implemented, allows us to discern whose participation is incentivised and increased, who can participate, and with what motives.

Lastly, a more nuanced understanding of the particular objectives and outcomes of improving citizen participation might be necessary. For example, one of the lowest participation groups is the youth; the program has the potential to empower the youth and encourage them to get involved in public decision-making. Therefore, investing in communication strategies to attract them will not only improve the program but also the way of doing politics in the coming years.

5. Conclusions

The article has highlighted a series of obstacles and challenges in the implementation of PB in Monterrey. This experience allows us to cast a critical eye over the exercise of participatory budget and how the PB idea has been disseminated and adapted in different parts of the world. The Monterrey case shows the risks associated with promoting PB as a best practice technocratic tool to allocate public resources, without having a serious debate about its basic objective: democratisation and the redistribution of wealth and power in unequal societies. This is evident in the case of Monterrey, where the formalities and procedures of PB have taken centre stage over the underlying purposes of achieving equity and social inclusion (Hernández‐Medina, Citation2010). We argue that the means and methods employed by PB should effectively align and be subordinated with the desired ends and outcomes of inclusion and fostering citizenship. In Monterrey, the underlying socio-economic inequalities resulted in greater involvement by higher income groups and budget allocation to better off neighbourhoods and sectors. PB has been successfully implemented on two occasions in the city, if we consider the sole goal of increasing invited citizen participation in a conservative and technocratic society. While we recognise that PB’s is a step forward regarding ways to redistribute economic resources in Monterrey, the programme has the potential to do more in terms of democratising urban interventions and fostering more robust and less tokenistic citizen participation in urban affairs.

It is therefore no surprise that the PB of Monterrey was conceptualised and operationalised as a process for promoting participatory democracy, co-responsibility, sustainability, efficacy, efficiency, accountability and transparency; and less oriented towards citizen empowerment and achieving equality. Most of the prioritised projects are located in better off neighbourhoods and improvements in infrastructure and public spaces, rather than service provision or addressing issues in structurally and historically neglected neighbourhoods in the city. As with many exercises throughout the world fuelled by the increasing popularity of PB, we find that the experience in Monterrey is a distant interpretation of the first instalments of the programme in Porto Alegre.

The Monterrey case hints that there is a potential of using PB as a means to profoundly transform power relations and transition to an experience that results in more deliberative, redistributive and democratic processes. Concurring with Cabannes (Citation2005), we agree that the participatory budget, as a process of expression of participatory democracy, does not actually become a local driver to representative democracy, but rather ends up transforming into a neighbourhood democracy or, ‘proximity democracy’ failing to overcome micro-local spaces (Montecinos Citation2009, p. 149). In Monterrey, the programme has so far increased invited participation, but missed the opportunity to countervail power dynamics and neutralise the advantages of political actors (Fung and Wright Citation2003). In other words, the programme has not brought citizens closer to changes in social relationships dynamics.

Increasing participation in public affairs is an accomplishment in itself when considering the multiple limitations the programme has had within the Monterrey government. The experience contrasts with the institutional restructuring in Brazil that accompanied the PB implementation, enabling democratic institutions that sustained the processes of participatory budget. The PB in Monterrey is still very isolated, and after two editions, has yet to consolidate its legitimacy, and there is still a long way to go in order to move towards a more emancipatory process of participation where the citizens appropriate the process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Natalia Garcia-Cervantes

Natalia García-Cervantes is a Research Professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design of the Tecnológico de Monterrey, Campus Monterrey. Her research focuses on diverse dynamics in urban areas, such as planning, insecurity and violence, and justice in cities.

Marina Ramirez

Marina Ramírez is an urbanist from the Tecnológico de Monterrey with a minor in Future Cities and Water Management from Windesheim University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. Her research interests include urban participatory processes for shared city-making, spatial justice through housing policies, as well as urban data science for decision-making and strategic urban planning.

Macarena Pena

Macarena Pena is an urbanist from the Tecnológico de Monterrey, working in the public sector. Her research interest include proximate urban environments, integrated water management for city resilience, strategic municipal and regional planning, and equitable participatory processes.

Rodrigo Junco

Rodrigo Junco, is an urbanist from Tecnológico de Monterrey. His research interests includes regenerative culture, water-sensitive planning, spatial justice, and participatory processes. His research aims to advance sustainable urban development through innovative and inclusive methodologies.

Notes

1. Monno and Khakee (Citation2012, p. 98) echoing Arnstein (Citation1969) refer to tokenism in the manner in which participation is restricted to information and consultation of participants ‘without any assurance that citizens’ concerns and ideas shall be taken into account’.

2. Official presentations were given in the context of a course taught at the Bachelor in Urbanism at Tecnologico de Monterrey, during the March-April 2023 academic period.

3. AGEBS: Áreas Geoestadísticas Básicas, geostatistical area units of analysis used by the National Institute of Geography and Statistics that compound from 1 to 50 squares.

4. INE: Identity Card given to citizens who are 18 years old or more, allows them to vote during elections and is the most commonly used id in the country.

5. Distrito Tec is an initiative based on Monterrey, Nuevo León that aims to regenerate the surroundings of the Tecnológico de Monterrey in collaboration with the municipality and the community through the improvement of public spaces and regenerating the social fabric of the area surrounding the main university campus.

6. This Social Index was built by getting an average of the social lag index of each AGEB given by CONEVAL (2020) where: Very High equals 5, High equals 4, Medium equals 3, Low equals 2, Very Low equals 1.

References

- Abers R. 1996. From ideas to practice: the partido dos trabalhadores and participatory governance in Brazil. Lat Am Perspect. 23(4):35–53. doi: 10.1177/0094582X9602300404.

- Arnstein SR 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst of Planners. 35(4):216–224.

- Aziz H, Shah N. 2021. Participatory budgeting: models and approaches. Pathways Between Soc Sci Comput Soc Sci: Theories, Methods, Interpretations. 215–236. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-54936-7_10.

- Baiocchi G. 2001. Participation, activism, and politics: the porto alegre experiment and deliberative democratic theory. Polit & Soc. 29(1):43–72.

- Baiocchi G, Ganuza E. 2014. Participatory budgeting as if emancipation mattered. Politics & Society. 42(1):29–50. doi: 10.1177/0032329213512978.

- Carpio A, Ponce-Lopez R, Lozano-García DF. 2021. Urban form, land use, and cover change and their impact on carbon emissions in the Monterrey Metropolitan area, Mexico. Urban Clim. 39:100947. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100947.

- Cabannes Y. 2005. Children and young people build participatory democracy in Latin American cities. Children Youth and Environ. 15(2):185–210.

- Cabannes Y. 2015. The impact of participatory budgeting on basic services: municipal practices and evidence from the field. Environ Urbanization. 27(1):257–284. doi: 10.1177/0956247815572297.

- Cabannes Y. 2004. Participatory budgeting: a significant contribution to participatory democracy. Environ Urbanization. 16(1):27–46. doi: 10.1177/095624780401600104.

- Cornwall A. 2017. Introduction: New democratic spaces? The politics and dynamics of institutionalised participation.

- de Monterrey G. 2021. Reglamento de Presupuesto Participativo de Monterrey, N.L. Ayuntamiento de Monterrey, Gobierno Municipal, 2021-2024. Available at: https://www.monterrey.gob.mx/pdf/reglamentos/1/Reglamento_de_Presupuesto_Participativo_del_municipio_de_monterrey.pdf.

- De Sousa S. 1998. Participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre: toward a redistributive democracy. Polit Soc. 26(4):461. doi: 10.1177/0032329298026004003.

- Dirección de Participación Ciudadana. 2022. Reporte del Presupuesto Participativo 2022. Secretaría de Innovación y Gobierno Abierto del Municipio de Monterrey. Monterrey’s Municipality Secretariat of Innovation and Open Government, SIGA; https://decidimos.monterrey.gob.mx/rails/active_storage/blobs/eyJfcmFpbHMiOnsibWVzc2FnZSI6IkJBaHBBbTFQIiwiZXhwIjpudWxsLCJwdXIiOiJibG9iX2lkIn19–fdf4ac59fc2836720b4780884c4cfc5724b52ec7/ReportePP2022_GOBMTY%20.pdf.

- Dirección de Participación Ciudadana. 2023. Presupuesto participativo. Secretaria de Innovación y Gobierno Abierto del Municipio de Monterrey. Presentation for the course Complejidad y Debate at the Bachelor in Urbanismo at Tecnologico de Monterrey, April 2023. Monterrey: Monterrey’s Municipality Secretariat of Innovation and Open Government, SIGA.

- Dodds A, Paskins D. 2011. Top-down or bottom-up: the real choice for public services? J Poverty Soc Justice. 19(1):51–61. doi: 10.1332/175982711X559154.

- Fundar. 2012. Participatory budgeting: citizen participation for better public policies. https://fundar.org.mx/publicaciones/brief-participatory-budgeting-citizen-participation-better-public-policies/.

- Fung A, Wright EO, eds. 2003. Deepening democracy: institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. London and (NY): Verso.

- Ganuza E, Baiocchi G. 2012. The power of ambiguity: how participatory budgeting travels the globe. J Deliberative Democracy. 8(2). doi: 10.16997/jdd.142.

- García Bátiz ML, Téllez Arana L. 2018. El presupuesto participativo: un balance de su estudio y evolución en México. PL. 26(52):0–0. doi: 10.18504/pl2652-012-2018.

- Garza C. 2020. Los efectos del uso de tecnología y rediseño de procesos de deliberación pública: estudio de caso del presupuesto participativo en San Pedro Garza García en 2019 [ Master Thesis]. Tecnológico de Monterrey, Escuela de Gobierno y Transformación Pública.

- Gherghina S, Tap P, Soare S. 2023. Participatory budgeting and the perception of collective empowerment: institutional design and limited political interference. Acta Polit. 58(3):573–590. doi: 10.1057/s41269-022-00273-4.

- Goldfrank B. 2006. Los procesos de“presupuesto participativo” en América Latina: éxito, fracaso y cambio. Revista de ciencia política (Santiago). 26(2):3–28. doi: 10.4067/S0718-090X2006000200001.

- Government of the State of Jalisco. 2016. Presupuesto Participativo Del Gobierno De Jalisco, Un Modelo Diferente E Incluyente: Aristóteles Sandoval. https://www.jalisco.gob.mx/es/prensa/noticias/37689.

- Hernández‐Medina E. 2010. Social inclusion through participation: the case of the participatory budget in São Paulo. Int J Urban Regional. 34(3):512–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00966.x.

- INEGI, National Institute of Statistics and Geography. 2020. Manual de Cartografía: Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020, 7.

- Marquetti A. 2002. “Democracia, Eqüidade e Eficiência: o Caso do Orçamento Participativo em Porto Alegre”. En Construindo um Novo Mundo: Avaliação da experiência do Orçamento Participativo em Porto Alegre-Brasil, editado por João Verle y Luciano Brunet 210–232. Porto Alegre: Guayí.

- Miraftab F. 2009. Insurgent planning: situating radical planning in the global south. Plan Theor. 8(1):32–50. doi: 10.1177/1473095208099297.

- Montecinos E. 2012. Democracia y presupuesto participativo en América Latina. La mutación del presupuesto participativo fuera de Brasil. Revista del CLAD Reforma y Democracia. 53:61–96.

- Montecinos E. 2009. El presupuesto participativo en América Latina.¿ Complemento o subordinación a la democracia representativa? Revista del CLAD Reforma y Democracia. 44:145–1174.

- Monno V, Khakee A. 2012. Tokenism or political activism? Some reflections on participatory planning. International Planning Studies. 17(1):85–101. doi: 10.1080/13563475.2011.638181.

- Municipality of Monterrey. 2023 29 de marzo. Es Monterrey primer lugar nacional en recaudación de predial. https://www.monterrey.gob.mx/noticia/es-monterrey-primer-lugar-nacional-en-recaudacion-de-predial.

- Municipality of San Pedro Garza García. 2023. Reglamento de Participación y Atención Ciudadana del Municipio de San Pedro Garza García, Nuevo León. (Articulo 342).

- Nylen W. 2003. Participatory democracy versus elitist democracy: lessons from Brazil. (NY): Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rodríguez Larragoity R. 2013. El capital social y presupuesto participativo: caso San Pedro Garza García, Nuevo León [ Doctorado thesis]. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

- Rumbul R, Parsons A, Bramley J. 2018. Elite capture and co-optation in participatory budgeting in Mexico City. International Conference on Electronic Participation; Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 89–99.

- Souza C. 2001. Participatory budgeting in Brazilian cities: limits and possibilities in building democratic institutions. Environ Urbanization. 13(1):159–184. doi: 10.1177/095624780101300112.

- Wampler B. 2004. Expanding accountability through participatory institutions: mayors, citizens, and budgeting in three Brazilian municipalities. Latin Am Polit Soc. 46(2):73–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-2456.2004.tb00276.x.

- Wampler B. 2000. A guide to participatory budgeting.