ABSTRACT

Accessibility is critical in achieving sustainable and equitable transport systems. This study investigates the accessibility of older adults, a group that has received little attention in the accessibility literature yet faces significant mobility barriers. Following qualitative approaches, including interviews and open-ended questionnaires, and employing the Accessibility as a Capability framework (AaaC) and Transport-Related Social Exclusion (TRSE) dimensions, the study analyses the opportunities and barriers older adults face in accessing transport systems in six wards of South Manchester. Results reveal the crucial role of individual abilities and perceptions in converting resources into access. Analysis of travel experiences showed that even when accessibility appears high, older adults may still expend a significant amount of effort to gain accessibility, particularly through emotional ‘work’ caused by transport-related fear and stress. The findings suggest a focus on the subjective aspects of travel to remove barriers to accessibility and improve access to valued capabilities while creating more equitable and sustainable transport systems.

Introduction

The 21st Century has seen two major population shifts in the shapes of urbanisation and an ageing population (Leeson Citation2018). Population projections estimate that the number of people aged 60 years and over will double by 2050 with more older people expected to live in cities (WHO Citation2015, Citation2018). These shifts present significant opportunities and challenges for the future. Although urbanisation can result in improved access to services and opportunities, this needs to be supported by the necessary infrastructure, welfare, and other provisions to ensure equitable outcomes and sustainable growth (Leeson, Citation2018). Population ageing is set to impact many sectors, including the economy, transport and land use (Ravensbergen et al. Citation2022). As such, transport systems need to be able to adapt to the ageing population to ensure the sustainability of cities and wider society.

The paramount goal of every transport policy is to improve accessibility to places, people and services (van Wee et al. Citation2011; Miller Citation2018). Access is crucial for societal participation and maintenance of socioeconomic and cultural capital (Miller Citation2018; Middleton and Spinney Citation2019). Societies and individuals rely on transport to access everyday opportunities and these requirements change over one’s lifetime and in accordance with place of abode (Banister Citation2019). A lack of access to opportunities, therefore, suggests exclusion from society and factors such as low income, age and disability can exacerbate this problem (Lucas et al. Citation2016). Equity analysis has been considered in accessibility studies (van Wee et al. Citation2011; Vecchio et al. Citation2020), but only recently have researchers begun to specifically consider older adults’ access to opportunities (Ravensbergen et al. Citation2022). In light of an ageing population, this paper is timely as it will bring critical awareness in ensuring older adults can access opportunities to improve their well-being while enhancing their active participation in society to keep cities thriving. This has long been recognised in the World Health Organisation’s Global Age-friendly Cities guidance (WHO Citation2007) of which twelve UK cities are members.

Ageing remains a pressing social issue in the UK and despite policy commitments, little is known about individual experiences. Planning and policy have tended to focus on improving transport infrastructure rather than the opportunities that infrastructure might afford to local people (Abreu et al. Citation2022). Accessibility measures tend to objectively focus on the interaction between land use and transport (Ryan and Pereira Citation2021). However, the simple existence of a transport system does not guarantee accessibility (Johnson et al. Citation2017). There is growing literature support for approaches that consider equity and social inclusion and the independence, well-being, and quality of life of ageing people (Lin and Cui Citation2021; Abreu et al. Citation2022). Transport studies have largely focused on mapping travel behaviour and assumptions about decision-making and routing (Miller Citation2005). Qualitative investigation that seeks to address the heterogeneity of individuals, their travel behaviour and their potential, imagined, aspirational and emotive mobilities is lacking (Pankhurst et al. Citation2014). Such a study will help place older people’s experiences at the centre of transport planning, thereby improving accessibility to opportunities. This paper aims to contribute empirical evidence to fill the existing gap.

The study aims to analyse the opportunities and barriers older adults face in accessing transport systems using South Manchester as a case study. The study draws on data from qualitative interview surveys and the Capability Approach (CA) to accessibility to understand the opportunities and barriers to mobility among older adults in South Manchester, UK. The study also employs the Accessibility as a Capability (AaaC) framework to analyse the processes by which the interaction between spatial resources and an individual’s conversion function can limit or expand their capabilities.

The study is structured as follows. The next section reviews the relevant literature on travel, accessibility, and exclusion, drawing on the context of older adults in the UK. This is followed by the methodological approach, including the conceptual framework. The results are then presented, followed by a discussion and conclusion.

Literature review

Ageing and travel

Ageing is negatively correlated to mobility. As people age, their mobility level declines sharply, underscoring the need for a more accessible and inclusive built environment to accommodate their needs (DfT Citation2021). This becomes more urgent given that older adults have the desire to maintain independence and inclusion when it comes to travel (Musselwhite and Haddad Citation2010). Although older people are not a homogenous group with varied mobility and travel characteristics (Su and Bell Citation2009), individual and contextual factors determine mobility needs. At the individual level, gender, education, employment status, income, residential location and household characteristics are the major factors influencing older adults’ travel patterns (Cui et al. Citation2016). Declining physical and mental health and increased frailty, on the other hand, reduce older adults’ mobility (Glass Citation2003). Contextual factors include the transport system and land use, as well as the policy landscape. Evidence shows that as people transition into later life, they undertake fewer daily trips and travel shorter distances (Páez et al. Citation2007). For this group, work-related trips decrease while medical, social and shopping-related trips increase (Titheridge et al. Citation2009; Cui et al. Citation2016). Engaging in social activity is particularly important for well-being and plays a major role in later life when established networks diminish (Middleton and Spinney Citation2019). Studies have also shown that older adults do not always travel for functional needs but also for recreation, such as viewing scenery, visiting new places and having chance encounters (Musselwhite and Haddad Citation2010). These aspects are likely to be missed in quantitative travel studies focusing solely on functional travel.

Conceptualising mobility and accessibility

Mobility is the ability to move from one place to another and often reflects the frequency of movements and trips made with a purpose (Plazinić and Jović Citation2018). Some scholars go beyond this definition of ‘realised’ mobility, to ‘potential’ mobility, which incorporates accessibility, motility, opportunities and capabilities (Flamm and Kaufmann Citation2006; Nordbakke Citation2013). This paper draws on ‘realised’ mobility and views it as an important element of accessibility but also acknowledges that a lack of mobility does not necessarily cause a lack of access. This understanding of mobility is compatible with the general understanding in gerontology: a person’s purposeful movement through the environment, which includes forms of transportation (Stalvey et al. Citation1999). Although researching mobility is important as it holds the potential to facilitate access, transport planning has largely concentrated on accessibility (van Wee et al. Citation2011; Miller Citation2018).

Accessibility conceptualisation tends to combine two aspects: the options to reach certain destinations and the resistance to travel (van Wee Citation2016). It is widely defined as ‘the extent to which land-use and transport systems enable (groups of) individuals to reach activities or destinations by means of a (combination of) transport mode(s)’ (Geurs and van Wee Citation2004, p. 128). Accessibility forms the basis for assessing the performance of transport systems in a region (Boisjoly and El-Geneidy Citation2017). Individual characteristics, including income, age, gender, disability and race (Geurs and van Wee Citation2004), provide a social perspective on transport planning (Lucas Citation2012). This perspective is important as it has generated debates around the influence of transport on social exclusion, social equity and sustainability (Lucas Citation2012).

In recent times, accessibility has been framed in terms of capabilities (Vecchio and Martens Citation2021; Luz and Portugal Citation2022). This provides impetus for the application of the capability approach (CA) in studying transport accessibility. Middleton and Spinney (Citation2019) argue that accessibility studies often focus on the ‘objective’ causes of (in)accessibility, as opposed to the actual experiences of being mobile and gaining accessibility. The authors argue that research should focus on the ‘emotional work’ involved in gaining accessibility, and the adaptations individuals undertake to perform in a transport system that does not serve them (Middleton and Spinney Citation2019). Banister (Citation2019) calls for a ‘softer’ approach to accessibility, moving away from the exclusive focus on the materialistic and functional aspects of travel to open up opportunities. This ‘softer’ approach involves measuring perceptions, preferences, experiences and barriers (Banister Citation2019; Tiznado-Aitken et al. Citation2020). As a response, however, scholars are increasingly pointing to the potential of ‘well-being’ based approaches to address the subjective experiences of accessibility, including the CA (Banister Citation2019; Vecchio and Martens Citation2021; Luz and Portugal Citation2022). The CA offers a stronger theoretical basis than traditional transport approaches as it allows the inclusion of subjective factors that shape accessibility (Nordbakke Citation2013). It accounts for the wide diversity of individuals’ characteristics, opportunities and choices (Vecchio and Martens Citation2021). Meanwhile, its people-centeredness provides opportunities to improve social equity, social inclusion and sustainability.

Social exclusion and transport

Social exclusion is largely viewed as relational, focusing on exclusionary processes rather than simply labelling a group as excluded (Popay Citation2010). Individuals are said to be situated on a multidimensional continuum of inclusion/exclusion characterised by the unjust distribution of resources, capabilities and rights (Silver Citation2007; Popay Citation2010). Social exclusion highlights the processes of unequal access to participation in society (Kenyon et al. Citation2002). Although all the excluded have the preference to be included, they are in most cases prevented by barriers beyond their control (van Wee et al. Citation2011). Exclusion policy tends to focus on educational and labour market concerns, which inevitably neglects the needs of the aged (Scharf Citation2015). Yet, the impact and prevalence of social exclusion are often amplified by old age (Walsh et al. Citation2017), underscoring the need to consider the processes by which older adults may become excluded from society.

For people who do not own a car, bus usage tends to increase in later life, especially in countries that provide concessionary passes (Musselwhite Citation2017). Yet, older people still face many barriers to access. Scholars note that issues around physical accessibility, safety, a lack of information, a lack of suitable equipment and furniture and staff are unhelpful to their needs (Musselwhite Citation2017). Understanding the barriers that older adults face in using public transport can, therefore, decrease car dependency and improve accessibility.

Even though it is difficult to say in an absolute sense whether a person is socially excluded and if this is caused by accessibility (Titheridge et al., Citation2009), the concern here is about the processes of transport-related social exclusion (TRSE). Previous studies have determined several dimensions of TRSE, comprising physical, economic, temporal, spatial, and psychological exclusion from facilities. Yigitcanlar et al. (Citation2018) proposed an informational dimension, to account for travel-related information availability. Benevenuto and Caulfield (Citation2019) introduced the social-position dimension to account for restriction based on one’s social position (e.g. gender, race, age, and ethnicity). Luz and Portugal (Citation2022) proposed a combination of all the aforementioned dimensions of TRSE and added ‘digital divide’ exclusion to account for difficulties using or accessing ICT and the internet, which is crucial with the rise of smart mobility (Groth Citation2019). This paper attempts to shed light on the barriers to accessibility faced by older adults using Luz and Portugal’s (Citation2022) TRSE dimensions (see Appendix 1). The processes, actions, and decisions that lead to social exclusion have to be given particular attention to transport research in order to promote just and equitable cities (Lucas Citation2012).

Methodology

Context

Older adults in the UK are largely car-dependent. Evidence suggests that apart from health and locational factors that require people to drive, the dependence reflects the failure of the UK’s transport systems to cater for their needs (Holley-Moore and Creighton Citation2015). Addressing these failings is crucial and the Department for Transport (DfT) recognises that high car dependency is not sustainable in growing metropolitan areas (DfT Citation2019). Accessibility planning in the UK is based on assessing whether ‘people are physically and financially able to access transport’ (SEU Citation2003, p. 1). The UK government publishes annual statistics on transport use (National Statistics Citation2022), yet the Office for Statistics Regulation found that statistics are currently not answering the key questions of those with an interest in accessibility (OfSR Citation2022). Travel statistics are based on modelled journey times which makes it hard to assess the effect of individual and household characteristics which leads to a lack of access and social exclusion (Lucas et al. Citation2016). More specifically, the DfT indicators are not suitable for evaluating the needs of older people as they do not reflect their purpose, attitudes and aspirations towards travel (Titheridge et al., Citation2009). Although accessibility is clearly on the UK transport agenda, the widely held view is that an approach solely based on physical and financial accessibility may be incomplete. Currently, older adults who give up driving suffer a reduction in health and well-being and an increase in stress and social isolation (Musselwhite and Haddad Citation2010). Giving up driving can also increase the likelihood of social exclusion (Cui et al. Citation2016). Therefore, accessible public transport and special transport services become important for those with more complex mobility needs. This study is timely as it will provide empirical evidence to shape the transport needs for older adults in the UK.

The growing interest in social exclusion has generated debate around its linkage to transport. The relationship was first established in the UK Social Exclusion Unit’s report ‘Making the Connections: Final Report of Transport and Social Exclusion’ (SEU Citation2003). The report introduced statutory accessibility audits into Local Transport Plans in England and Wales, involving aggregate measures based on average travel time to essential destinations. Since then, the interaction between accessibility, transport and social exclusion and its effect on accessibility has been explored (Farrington Citation2007). Greater Manchester has Greater Manchester Accessibility Levels (GMAL) to measure the accessibility of a certain point to transport provisions, considering walk access time and service availability (TfGM Citation2016). However, these indicators say nothing about what individuals can access given their unique sets of circumstances (Titheridge et al., Citation2009), including age, gender, disability, and ethnicity. Preston and Rajé (Citation2007) found that measures that account for these factors, still homogenise groups and lose the richness of individuals’ lived experiences and the multidimensional nature of exclusion. This clearly calls for a study that considers the actual exclusionary experiences of specific groups.

Conceptual frameworks: the capability approach (CA) and accessibility as a capability (AaaC) framework

The Capability Approach (CA) focuses on individual freedom and its close association with achievement and well-being (Sen Citation1999). The CA represents a fundamental shift from conventional utilitarian approaches that focus on a person’s resources, to a focus on their capabilities. It sees human beings and their well-being as the ‘end’ or objective of development rather than economic growth (Alkire Citation2007), focusing on what they achieve instead of utility. The approach consists of four main concepts: resources, individual ‘conversion function’, functioning, and capabilities. Resources are the commodities and intangible goods available to a person and are considered a ‘means to achievement’ (Sen Citation1992, p. 33). The individual conversion function is the ability to convert resources into capabilities. Functioning is the ‘various things a person may value doing or being’ with realised functioning, representing what a person achieves and how (Sen Citation1999, p. 75). Capabilities are the ‘alternative combinations of beings and doings that are feasible to achieve’ and entail real opportunities that are available for people to do and be (Sen Citation1999, p. 75).

Well-being is achieved through both functioning and capabilities. While capabilities represent the various opportunities available to a person, functioning are those capabilities the individual chooses to realise and achieve. Therefore, individual freedom and choice are central to the CA (Nussbaum and Sen Citation1993). Sen (Citation1992) makes clear that capabilities must be valued by the individual to achieve freedom and well-being. Social systems should be evaluated according to the extent of freedom people have to achieve the functioning they value (Alkire Citation2002). This paper follows this line of thought and evaluates the urban transport system on its ability to allow people to achieve desired functioning.

Although the operationalisation of the CA in transport geography is still in the infancy stage, it is fast gaining traction as an alternative approach to transport and accessibility analysis (Nordbakke Citation2013; Hickman et al. Citation2017; Bantis and Haworth Citation2020; Vecchio Citation2020). Past studies have utilised Nussbaum’s 10 central capabilities (see Nussbaum Citation2000, Citation2009). Nussbaum argues that ’their list of capabilities has universal appeal, and they are important for any demographic group (Nussbaum Citation2000). This study aims to allow older adults to express what they value, avoiding assumptions and generalisations. As such, the central capabilities will be used to frame the discussion and emphasise capabilities that are not met.

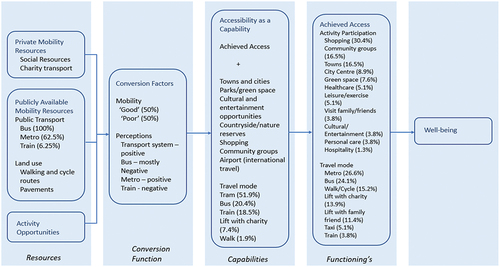

Scholars have conceptualised accessibility as a capability (AaaC) (Vecchio and Martens Citation2021; Luz and Portugal Citation2022). This framing considers how an individual builds and appropriates the possibility of being mobile and accessing valued opportunities () (Vecchio and Martens Citation2021). Luz and Portugal (Citation2022) illustrate how when the interaction between spatial resources and the individual’s conversion function limits an individual’s capabilities, manifesting in the form of barriers. These barriers can create systematic problems in accessing opportunities and can lead to TRSE as discussed previously. Sen argues that evaluations and policies should focus on removing barriers so that individuals have more freedom to live what they value (Robeyns Citation2005). Clearly, identifying barriers to accessibility is crucial to understanding how they can be removed. This study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of these barriers. We argue that removing barriers will expand the capability set that is associated with functioning and ultimately well-being, thereby improving the social inclusion of older adults.

Figure 1. Accessibility as a capability framework (AcaaC).

Research approach

This paper utilises a mixed-method approach. To gather data on AaaC, Vecchio and Martens (Citation2021) recommend combining a top-down aggregate component on addressing transport systems and land use and a bottom-up component shedding light on conversion factors (also known as conversion function and used interchangeably in this paper) through an individual understanding of mobility. For the top-down element, secondary data from Transport for Greater Manchester’s (Citation2016) Accessibility Levels (GMAL) is used. The contribution of this paper is the bottom-up element where the qualitative approach is used for understanding complex notions like freedom and opportunities that are core to the CA framework. To assess TRSE, we use a qualitative approach to understand the individual and grassroots perspectives of those who experience exclusion (Lucas Citation2019). Open-response questionnaires and semi-structured interviews were used to gather the qualitative data.

Data collection

A questionnaire survey was used in gathering empirical data. An open-response questionnaire was used to gather information about participants’ characteristics, perceptions, thoughts and experiences. Open-ended questions were designed to allow participants to recount experiences, perceptions and opinions in their own way (McGuirk and O’Neill Citation2016). The questionnaire data was triangulated with interviews. A semi-structured interview asked follow-up questions on emerging issues from the questionnaire while understanding participants’ subjective travel experiences. A total of 26 participants responded to the open-ended questionnaires while 5 interviews were conducted.

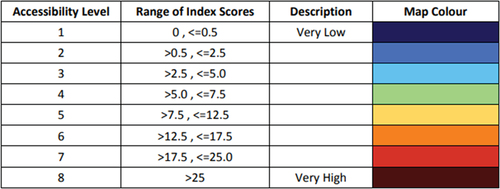

The questionnaire data was used in conjunction with secondary data from Transport for Greater Manchester’s Accessibility Levels (GMAL), which provides data on participants’ spatial resources using postcodes. GMAL scores any location within the Greater Manchester region from 1 to 8 depending on the density of public transport provision (bus, metro and rail), considering access times and average wait times (TfGM Citation2016). A score of 1 represents very low accessibility, while a score of 8 represents very high accessibility (see Appendix 2). GMAL is weighed towards the most accessible transport service, assuming it will be the mode of preference.

Participants recruitment

Questionnaires and interviews were carried out with older adults (60+), who live in the three areas of South Manchester, and who either did not have a driver’s licence or owned a road vehicle at the time of the research. The specificity of the sample allowed involves a relatively small number of participants, assuming that it would be sufficient to grasp the capabilities and functioning relevant to those who meet the criteria. The study areas were selected as they contained the highest proportion of the over 66 age group in the southern region of Greater Manchester and were characterised by at least 1.5% population growth of this age group by 2031 (Wall Citation2021). The three study areas, each made up of two electoral wards, were Chorlton and Chorlton Park, Didsbury East and Didsbury West, and Sharston and Northenden.

Participants were recruited through two pathways. Non-probabilistic sampling is often inevitable in studying specific or hard-to-reach populations (Wellington and Szczerbinski Citation2007). Therefore, an opportunistic sampling method was used by advertising the survey through local community groups on social media. Secondly, participants were recruited using a guided sampling technique using stakeholders from local community groups who facilitated access to the desired participants. Involving stakeholders or ‘gatekeepers’, is often essential in the recruitment of older adults as it increases trust and rapport and can facilitate access to especially hard-to-reach populations (Weil et al. Citation2017).

Questionnaires were completed in February and March 2023. The in-person questionnaires were handed out to a local community group after a short presentation on the project. Participants of both online and in-person questionnaires were required to read and acknowledge the participant information and consent forms for ethical purposes. The questionnaire finished by asking participants if they would like to participate in a follow-up interview, which took place in March 2023 over the phone and email exchanges (one participant). Interviews were audio recorded with the consent of the participants and then transcribed, removing personal identification data to ensure complete anonymity.

Data analysis

The interview data was transcribed and imported into NVivio together with the open-ended questionnaire data for analysis. A qualitative content was then applied. Coding was used to deduce the components of AaaC and TRSE. The categorised data was then reduced analytically to identify and highlight the most relevant and meaningful patterns in the data.

Results

provides an overview of the residential and household characteristics of the study participants. The sample is weighted towards females and Chorlton residents which appeared to be the main demographic of the charity, where 17 of the questionnaires were completed. It was targeted to complete more than five interviews, yet retention of participants proved difficult, potentially due to research fatigue or uncertainty about the value of their participation. The main results are laid out in two parts: the first section follows the components of AaaC, and the second part addresses the TRSE dimensions.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants (n = 26).

Mobility resources

The participants’ mobility resources (i.e. the public transport available to them) were assessed by scoring postcodes against GMAL. Postcodes ranged between 4 and 6 with an average of 5. According to GMAL (see Appendix 2), participants have an average to high ‘accessibility’ to public transport resources. In terms of mode, all postcodes showed access to the bus service, with 65% having access to the metro. Only one postcode had access to a train. In terms of private resources, some participants expressed they had access to charity-provided transport resources, access to lifts in family and friend’s vehicles (social resources) and taxi services. These available resources define how mobile and frequent participants move around in Manchester and beyond.

Conversion function

Ability

As expected, participants’ abilities varied. Participants were split in terms of describing good mobility or poor mobility. While some mentioned they could only walk for a short length of time, others reported using walking aids such as rollators, trolleys, walking poles and sticks. Although not explicitly asked, participants also mentioned health issues, including problems with hearing and eyesight, and cognitive and psychological issues that affect their ability to travel. These abilities define what the participants can do on their own or with the help of mobility aids.

Perceptions

When considering the public transport system in its entirety, people’s perceptions were largely positive. Respondents mentioned the range of transport modes available to them and how this provides opportunities to travel locally and further afield. Respondents remarked as:

You can always rely on public transport. You can catch the tram to the outskirts of Manchester, and you can catch a bus all over the place. (Male, Chorlton)

My area has good transport links for local and further trips. (Female, Didsbury)

Several participants expressed that they felt lucky with the public transport options available to them, and compared their resource provision potentially worse off in some areas:

Yes, we are very lucky. We have good public transport, we have a metro, we have got buses. I know we are very lucky, a lot of places don’t have public transport. (Female, Chorlton)

However, perceptions of individual transport modes varied. Perceptions of the Metro (tram) were largely positive. People expressed that they ‘liked’ and ‘loved’ the tram and described it as ‘excellent’, ‘brilliant’, ‘accessible’, ‘reliable’, ‘clean’, ‘safe’ and ‘on-time’, but that destinations were sometimes limited. Perceptions of the buses were mixed with some describing the service as ‘good’, ‘reasonable’ and ‘satisfactory’; but many had negative perceptions, with participants describing them as a ‘nightmare’, ‘inconsistent’, ‘old’, ‘crowded’ and ‘not comfortable’, with journeys that are ‘slow’ and ‘too long’. Some participants felt that the bus services had deteriorated in recent years. It is noted that bus services may have been cut since GMAL was published.

Since revamped a few years ago, many services have been cut, making it very difficult to get to appointments … the local estate bus is being cut meaning a 10/15-minute walk to the other bus. (Female, Chorlton)

Among the few participants who mentioned the train, there was a consensus that local trains were unreliable due to frequent cancellations. In terms of active travel, perceptions were generally positive, and participants mentioned a variety of routes specifically for walking that are available to them. However, participants felt that the pavements were unsafe and difficult to navigate.

The interaction between resources and the conversion function

Responses revealed that mobility appeared to be a significant factor in determining individuals’ interaction with resources. For example, two female participants () from Chorlton with different levels of mobility had different perceptions of the resources available to them:

Table 2. Participants interaction between mobility and perceptions of resources.

The respondent with poor mobility relied on private transport resources (lifts with friends and taxis), which appeared to be common among those who described poor mobility. Perceptions also shaped participants’ interactions with resources. Despite nearly all participants having the highest access to bus services according to GMAL, people appeared to use the tram due to favourable perceptions.

I only use the bus to access parts that I cannot get to on the tram. I prefer the tram because it’s clean, reliable, and safe. (Female, Chorlton)

As soon as the tram was built, that was it, I never used the bus. And the same with other people, as soon as the trams were built, they stopped using the buses. (Male, Chorlton)

It can be seen that participants’ ability and perceptions shape their interaction with the transport system. Functioning further reveals how the interaction between conversion factors and resources shapes achieved access.

Functioning

Participants mentioned an average of 3 places or activities they travel to in a typical week. Shopping was the most cited achieved access, followed by community groups, towns, the city centre, and areas of green space. The most frequent travel mode was the metro, followed by the bus. A good proportion of the participants used private transport modes, and several participants travelled actively. This provides insight into the main reasons why older adults travel within and outside Manchester.

Capabilities

Participants were asked about places and activities they value being able to access, even if they do so infrequently. It emerged that they value being able to travel to a variety of places inside and outside of Manchester, including towns and cities, the countryside, natural landmarks and international travel. The metro was mentioned as the preferred mode of transport for the majority of these trips, followed by train and bus. A small number of participants also mentioned that they rely on charity-provided lifts to access valued capabilities. One participant expressed the importance of these special transport services:

[Charity A] take us on day trips and we go to a pub for lunch. They have a bus that has a lift so we can get onto it easily. Charity A is my life now, without it I would be very upset and lonely. I would just be sat at home. (Female, Chorlton)

Accessibility as a capability (AaaC)

shows the accessibility of the participants using the AaaC framework. The figure shows how accessibility capabilities and achieved access are derived from the interaction between (public and private) resources and conversion factors. Importantly, the interactions between conversion factors and resources are revealed. For example, participants display higher metro use due to positive perceptions and use private transport modes due to poor mobility.

Travel experience: values

It was revealed that not all travel was undertaken to reach an activity or place. As such, value was derived from travel itself, or the capability to be mobile. Participants valued the independence, freedom and enjoyment that travel gives them. One respondent remarked:

I like the feeling of independence and freedom when I am travelling. Only my age and mobility are restricting me. (Female Northenden)

The interviews revealed that participants valued simply being able to get ‘out and about’. For some, it was important to socialise and avoid loneliness and for others, it was the peripheral, scenic aspects of travelling that they cherished.

I like using public transport, it gets me about to see people. I live alone so it helps with not being alone all the time. (Female, Chorlton)

I watch the seasons changing and listen to music. (Female, Chorlton)

I enjoy the residential scenery, there are lovely trees and houses. (Female, Chorlton)

These can be viewed as capabilities, such as the capability to experience freedom or enjoyment. They are subjective and emotive in nature as opposed to functional and relate to the wider transport system, rather than a specific mode.

TRSE dimensions

shows the number of references made to each TRSE dimension. Sub-themes were identified for dimensions with a significant number of references. Exclusion based on fear, prejudice and feelings; and physical and cognitive exclusion were the most significant dimensions mentioned with 22 references each, followed by geographical exclusion with 17 references. Time-based exclusion and informational exclusion, although lower, were also mentioned a number of times.

Table 3. TRSE dimensions with themes.

Exclusion based on fear, prejudice or feelings

Participants mentioned a range of concerns based on fear, prejudice and feelings. Some participants described more direct experiences of crime and abuse that led to fear when travelling.

There was a stabbing on the metro a few months ago. I saw the crime scene investigators and a section cornered off. For people to say it’s safe, it’s clearly not because people are getting stabbed. I saw a woman tooting gas on the tram or some sort of drug and I have seen kids jumping on the tram tracks. I also saw people making fun of a woman saying that she smelt bad. If that happened to me, I would be so embarrassed. (Female, Sharston)

Sometimes coming to or from a hospital appointment people can be mean. I often feel unsafe, people can be mouthy when you are disabled and have been robbed and assaulted. (Female, Northenden)

I am always alert. I never wear anything like necklaces which may look attractive to other people. I never use my mobile phone. Again, I don’t want to look vulnerable. (Female, Chorlton)

Several participants mentioned a fear of travelling when it is dark. To many, this a dangerous enterprise they will never embark:

Well, it’s not the transport that I fear, it’s more walking to and from the bus stop. Just because there is nobody else around. You just feel like ‘Gosh there is nobody about’. (Female, Chorlton)

Participants also feared traffic and collisions when travelling, with one participant experiencing actual accident and remarked as:

Walking is dangerous. I have been hit from behind several times by bicycles which expect you to jump out of the way which I won’t. I can’t. (Female, Northenden)

Physical and cognitive exclusion

The study revealed a range of physical and cognitive barriers to accessibility. Firstly, several participants mentioned the inadequacy of pavements and how this makes walking with poor mobility and walking aids very difficult.

I have OA so use walking poles. Chorlton has forest trees growing out of the pavement, these cause the pavement to lift or clip. This is very, very dangerous trip hazard. (Female, Chorlton)

We have pavements, but many are narrow and covered with overgrown hedges, parked vehicles and wheelie bins. (Female, Northenden)

Participants also mentioned difficulties finding a seat due to saturated vehicle occupancy.

Vehicle occupancy appeared to dictate whether someone has a pleasant travel experience or not.

Interestingly, it was observed that participants have adapted to the situation by avoiding travelling altogether during busy times such as school rush hour, to avoid difficulties moving and finding a seat.

A range of other issues were mentioned around the lack of available equipment and infrastructure for disabled people. One respondent expressed how the lack of equipment made her ultimately not want to use the bus, which is a clear indication of how TRSE dimensions can result in a lack of capability.

Sometimes there is a bus shelter, but sometimes there are no seats on them, or the seats are dirty and sometimes there is just a pole. 30 minutes is a long time to stand in the rain for someone like me. When you consider all of that, it just makes me not want to use the bus. I would rather stay at home. (Female, Sharston)

Interestingly, it was found that equipment and infrastructure were often present, but they are in most cases in poor condition or not available to use. This included lifts that were out of order, seats that were dirty and uncomfortable, and ramps that were not available to use. It also emerged that bus drivers can be reluctant to lower ramps for seniors and many considered this very worrying. Similarly, information tends to be present but not available to read as participants described having difficulties reading information that is too high, too far away or too small.

Geographical exclusion

There were 17 references for transport services not going to the desired places. Seven of these related to a lack of access to local hospitals and seven related to a lack of access to the countryside. Participants mentioned that travelling to two hospitals in South Manchester (Wythenshawe and Withington Hospital) by public transport was either difficult or impossible. Services appeared to only take them part of the way to the hospital. While some manage to supplement the public transport route with walking, others cannot do it. The role of conversion factors is evident here through differing abilities. One participant summed up these differences:

The sad thing is the lovely tram doesn’t go into the hospital either. It’s fine if you are relatively able to walk, but if you’re not able to walk, it’s a problem. I can still walk for an MRI and to the hospital, I can still do it. My husband is struggling. Particularly Wythenshawe. (Female, Chorlton)

It was found that participants who are not able to walk had to rely on lifts from friends and family. This was interesting; it highlights an adaptation strategy to overcome the barrier which can be explained by the necessity of accessing a hospital.

Participants also expressed a desire to access areas of countryside and national parks but pointed out that public transport routes either do not take them there or involve trains which, as discussed, are perceived to be unreliable.

I would like better access to the countryside. The National Trust has three local centres but no easy public transport routes to get there. (Female, Chorlton)

Snowdonia and the peak district are not great for public transport. (Male, Chorlton)

Some participants also mentioned that they were unable to access a bus or tram service due to distance, echoing a mobility challenge, a deterioration in bus services in their local area and a lack of tram stops.

Interestingly, seven out of the 26 participants expressed that they faced no difficulties or barriers travelling and accessing the places they wanted to go. This could indicate that these participants did not face any barriers, which is good for accessibility.

Discussion

The study results reveal that using the CA and TRSE dimensions can provide a more detailed and nuanced picture of accessibility. Participants had access to public and private mobility resources and used them to access a range of places and activities, which appears positive for accessibility. An exclusive focus on transport provisions (resources) or travel behaviour (functioning) reflects typical approaches in transport studies used to measure accessibility (Miller Citation2005). It is only with deeper investigation into conversion factors, barriers and values we begin to understand how the transport system may not be serving our older population. The study has demonstrated that the true value of spatial resources will depend on an individual’s ability (conversion function) to convert them into valued functioning, which is consistent with previous studies (Vecchio and Martens Citation2021; Luz and Portugal Citation2022). The lack of capability to access hospitals in South Manchester is concerning and supports findings by Holley-Moore and Creighton (Citation2015) who reported that older adults throughout England experience this problem. By using the CA, we introduce the role of the conversion function and demonstrate that despite resources being ‘available’, turning these into a capability is not possible for everyone due to differing levels of individual ability. Transport for Greater Manchester considers both hospitals accessible by public transport (TfGM Citation2022), yet the findings suggest planners reconsider their decision, considering differing levels of ability. This is important because access to hospitals is a central transport-related human capability (Cao and Hickman Citation2019a, Citation2019b), and should be prioritised.

Previous studies remained silent on the role of perceptions in converting resources into functioning. The present findings underscore the importance of perception. Although participants had higher (spatial) access to bus services, the metro facilitated access to more valued functioning and capabilities due to favourable perceptions. This coupled with participants’ travel experiences and TRSE provides a better understanding of how perceptions are formed and shaped by experiences of the transport system (Tiznado-Aitken et al. Citation2020), suggesting that with appropriate interventions, transport perceptions and experiences could be shaped more positively.

The findings also highlight the role of emotions in determining an individual’s conversion function, revealing how stress can play a role in achieving access, particularly through perceived danger. The findings support arguments that a myriad of factors, individual abilities, perceptions and emotions underscore conversion function (Vecchio and Martens Citation2021).

With the lens of the CA and specifically the conversion factors, we get a deeper understanding of the processes behind converting resources into access, thereby revealing the limitations of the current transport system in Manchester.

Barriers to accessibility

The barriers found in this study are in line with non-capability research, which suggests that physical accessibility, safety, information, and equipment are the key challenges older adults face when travelling (Musselwhite Citation2017). This reinforces the need for critical interventions. By bringing capabilities and social inclusion into the accessibility sphere, this study suggests that the transport system can disadvantage and restrict people, underscoring the need to do more to address the inequities. Interestingly, the study also reveals that the presence of a barrier does not necessarily determine inaccessibility or exclusion. This is so because older adults have adopted strategies to overcome barriers, such as only travelling at certain times. The ability of older adults to shape their mobility needs has been highlighted in past studies (Nordbakke Citation2013). The fear of crime, abuse, the dark and traffic collisions create a considerable amount of ‘emotional work’, which form another set of accessibility barrier. According to Middleton and Spinney (Citation2019), for something to be equally accessible, all users should expend a comparable amount of emotional work and have the same journey quality. This finding highlights the need for transport planners to focus on removing the barriers experienced by different social groups to improve equity and accessibility.

Valued capabilities

In line with the CA, this study attempted to engage with the capabilities older adults’ value and have reason to value. The current findings support previous studies (Musselwhite and Haddad Citation2017; Lin and Cui Citation2021) which report that older adults tend to value the sense of freedom, independence and enjoyment that travel gives them. This is especially important given that accessibility research tends to exclusively focus on the functional outcomes of travel (Banister Citation2019). Participants valued the independence; enjoyment travel gives them and the social and scenic aspects of travel. The importance of such capabilities for well-being are recognised through a central capability lens (Hickman et al., Citation2017).

Conclusion

This study aimed to analyse the accessibility of older adults of South Manchester employing the Accessibility as a Capability framework (AaaC) and Transport-Related Social Exclusion (TRSE) dimensions. The findings reveal that resource availability does not guarantee accessibility, indicating that more attention needs to be paid to how individuals engage with resources. Older adults were found to possess and value non-functional capabilities, including freedom and enjoyment, important and subjective elements hardly considered in transport research. The study shows that even when activity participation is high, older adults may still expend a significant amount of effort to gain accessibility, specifically fear and stress. The results of this study highlight the importance of subjective factors when ‘gaining’ accessibility, including perceptions, emotional ‘work’ and values. In a field heavily concerned with functional and material accessibility needs, the findings call for greater consideration of the individual abilities, perceptions, preferences, values and barriers experienced by those ‘gaining’ accessibility. Further research may explore the role of particular transport investments in expanding the capability set. Ultimately, accessibility planning should aim to remove barriers and improve access to valued capabilities to create more equitable and sustainable transport systems.

The study has a few limitations. It interpreted capabilities as perceived opportunities, in line with previous studies, yet capabilities are more complex than perceived opportunities. A new approach to measuring this complex concept could be a good exercise for future studies. Another limitation is that the sample was skewed towards females and Chorlton residents due to recruitment support by the Chorlton-based charity that provided transport to the beneficiaries. This means that the results may not be a true representative of those areas without such resources, hence, the findings need to be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, the findings reveal nuanced features of accessibility associated with the conversion function, presenting policy implications for transport plans in Manchester and other cities that employ capability frameworks. We also recommend future studies to consider adopting quantitative analysis, drawing on large sample size that is representative enough to understand how the various factors considered in this study interact in shaping transport accessibility among the elderly. Case studies of different contexts would also be important in helping to corroborate the current findings.

Appendices

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the research participants for their time. Special thank you goes to the charity Chorlton Good Neighbours, for allowing the first author to conduct surveys with their beneficiaries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elisha Henry

Elisha Henry is a recent graduate of the Department of Environment and Geography, University of York. Elisha collected the data for this work as part of her project work.

Gideon Baffoe

Gideon Baffoe is a Lecturer and Assistant Professor at the Department of Environment and Geography, University of York. He specialises in urban and rural development, planning impacts, informality, and sustainable cities.

References

- Abreu M, Comim F, Jones C. 2022. A capability-approach perspective on levelling up. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/qjau5.

- Alkire S. 2002. Valuing freedoms: Sen’s capability approach and poverty reduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Alkire S. 2007. Why the capability approach? J Hum Devel. 6(1):115–135. doi: 10.1080/146498805200034275.

- Banister D. 2019. Transport for all. Transp Rev. 39(3):289–292. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2019.1582905.

- Bantis T, Haworth J. 2020. Assessing transport related social exclusion using a capabilities approach to accessibility framework: a dynamic Bayesian network approach. J Transp Geogr. 84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102673.

- Benevenuto R, Caulfield B. 2019. Poverty and transport in the global south: an overview. Transp Policy. 79:115–124. doi: 10.1016/J.TRANPOL.2019.04.018.

- Boisjoly G, El-Geneidy A. 2017. Measuring performance: accessibility metrics in metropolitan regions around the world. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/measuring-performance-accessibility-metrics.pdf.

- Cao M, Hickman R. 2019a. Urban transport and social inequities in neighbourhoods near underground stations in Greater London. Transp Plann Technol. 42(5):419–441. doi: 10.1080/03081060.2019.1609215.

- Cao M, Hickman R. 2019b. Understanding travel and differential capabilities and functionings in Beijing. Transp Policy. 83:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.08.006.

- Cui J, Loo BPY, Lin D. 2016. Travel behaviour and mobility needs of older adults in an ageing and car-dependent society. Int J Urban Sci. 21(2):109–128. doi: 10.1080/12265934.2016.1262785.

- DfT. 2019. Future of mobility: urban strategy.

- DfT. 2021. Inclusive mobility.

- Farrington JH. 2007. The new narrative of accessibility: its potential contribution to discourses in (transport) geography. J Transp Geogr. 15(5):319–330. doi: 10.1016/J.JTRANGEO.2006.11.007.

- Flamm M, Kaufmann V. 2006. Operationalising the concept of motility: a qualitative study. 1(2):167–189. doi: 10.1080/17450100600726563.

- Geurs KT, van Wee B. 2004. Accessibility evaluation of land-use and transport strategies: a review and research definitions. J Transp Geogr. 12(2):127–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2003.10.005.

- Glass TA. 2003. Neighbourhoods, ageing and functional limitations. In: Kawachi I, and Berkman LF, editors. Balfour, J.L. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; p. 303–334.

- Groth S. 2019. Multimodal divide: reproduction of transport poverty in smart mobility trends. Transp Res Part A: Policy Pract. 125:56–71. doi: 10.1016/J.TRA.2019.04.018.

- Hickman R, Cao M, Lira BM, Fillone A, Biona JB. 2017. Understanding capabilities, functionings and travel in high and low income neighbourhoods in Manila. Soc Inclusion. 5(4):161–174. doi: 10.17645/SI.V5I4.1083.

- Holley-Moore G, Creighton H. 2015. The future of transport in an ageing society.

- Johnson R, Shaw J, Berding J, Gather M, Rebstock M. 2017. European national government approaches to older people’s transport system needs. Transp Policy. 59:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.06.005.

- Kenyon S, Lyons G, Rafferty J. 2002. Transport and social exclusion: investigating the possibility of promoting inclusion through virtual mobility. J Transp Geogr. 10(3):207–219. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6923(02)00012-1.

- Leeson GW. 2018. The growth, ageing and urbanisation of our world. J Popul Ageing. 2(11):107–115. doi: 10.1007/S12062-018-9225-7.

- Lin D, Cui J. 2021. Transport and mobility needs for an ageing society from a policy perspective: review and implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(22):11802. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182211802.

- Lucas K. 2012. Transport and social exclusion: where are we now? Transp Policy. 20:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.01.013.

- Lucas K. 2019. A new evolution for transport-related social exclusion research? J Transp Geogr. 81:102529. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.102529.

- Lucas K, Mattioli G, Guzman A. 2016. Transport poverty and its adverse social consequences. Transport. 169(6):353–356. doi: 10.1680/jtran.15.00073.

- Luz G, Portugal L. 2022. Understanding transport-related social exclusion through the lens of capabilities approach. Transp Rev. 42(4):503–525. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2021.2005183.

- McGuirk PM, O’Neill P. 2016. Using questionnaires in qualitative human geography. In: Hay I, editor. Qualitative research methods in human geography. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; p. 246–273.

- Middleton J, Spinney J. 2019. Social, inclusion, accessibility and emotional work. In: Docherty I, and Shaw J, editors. Transport matters. Bristol, UK: Policy Press; p. 83–104.

- Miller EJ. 2018. Accessibility: measurement and application in transport planning. Transp Rev. 38(5):551–555. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2018.1492778.

- Miller HJ. 2005. Place-based versus people-based accessibility. In: Levinson DM Krizek KJ, editors. Access to destinations. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; p. 63–89. 10.1108/9780080460550-004.

- Musselwhite C. 2017. Public and community transport. In: Musselwhite C, editor. Musselwhite, C Vol. 10, Leeds, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited; p. 117–128.

- Musselwhite C, Haddad H. 2010. Mobility, accessibility and quality of later life. Qual Ageing Older Adults. 11(1):25–37. doi: 10.5042/qiaoa.2010.0153.

- Musselwhite C, Haddad H. 2017. The travel needs of older people and what happens when people give up driving. In: Musselwhite C, editor. Transport, travel and later life. Emerald Publishing Limited; p. 93–115.

- National Statistics. 2022. National travel survey: 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-travel-survey-2021.

- Nordbakke S. 2013. Capabilities for mobility among urban older women: barriers, strategies and options. J Transp Geogr. 26:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.10.003.

- Nussbaum M. 2000. Women and human development: the capabilities approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Nussbaum M. 2009. Creating capabilities: the human development approach and its implementation. Hypatia. 24(3):211–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2009.01053.x.

- Nussbaum M, Sen A. 1993. The quality of life. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- OfSR. 2022. Review of transport accessibility statistics.

- Páez A, Scott D, Potoglou D, Kanaroglou P, Newbold KB. 2007. Elderly mobility: demographic and spatial analysis of trip making in the Hamilton CMA, Canada. Urban Stud. 44(1):123–146. doi: 10.1080/00420980601023885.

- Pankhurst G, Galvin K, Musselwhite J, Phillips J, Shergold I, Todres L. 2014. Beyond transport: understanding the role of mobilities in connecting rural elders in civic society. In: Hennessey C, Means R, and Burholt V, editors. Community and place in rural Britain. Bristol, UK: Policy Press; p. 125–158.

- Plazinić BR, Jović J. 2018. Mobility and transport potential of elderly in differently accessible rural areas. J Transp Geogr. 68:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.03.016.

- Popay J. 2010. Understanding and tackling social exclusion. J Res Nurs. 15(4):295–297. doi: 10.1177/1744987110370529.

- Preston J, Rajé F. 2007. Accessibility, mobility and transport-related social exclusion. J Transp Geogr. 15(3):151–160. doi: 10.1016/J.JTRANGEO.2006.05.002.

- Ravensbergen L, Van Liefferinge M, Isabella J, Merrina Z, El-Geneidy A. 2022. Accessibility by public transport for older adults: a systematic review. J Transp Geogr. 103:203408. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103408.

- Robeyns I. 2005. The capability approach: a theoretical survey. J Hum Devel. 6(1):93–117. doi: 10.1080/146498805200034266.

- Ryan J, Pereira RHM. 2021. What are we missing when we measure accessibility? Comparing calculated and self-reported accounts among older people. J Transp Geogr. 93:103086. doi: 10.1016/J.JTRANGEO.2021.103086.

- Scharf T. 2015. Eight: between inclusion and exclusion in later life. In: Walsh K, Carney GM, and Leime A, editors. Ageing through austerity. Bristol, UK: Policy Press; p. 113–130.

- Sen A. 1992. Inequality Re-examined. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Sen A. 1999. Development as freedom. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- SEU. 2003. Making the connections: final report on transport and social exclusion.

- Silver H. 2007. The process of social exclusion: the dynamics of an evolving concept. No. 95; CPRC working paper.

- Stalvey B, Owsley C, Sloane ME, Ball K. 1999. The life space questionnaire: a measure of the extent of mobility of older adults. J Appl Gerontology. 18(4):460–478. doi: 10.1177/073346489901800404.

- Su F, Bell MGH. 2009. Transport for older people: characteristics and solutions. Res in Transp Econ. 25(1):46–55. doi: 10.1016/J.RETREC.2009.08.006.

- TfGM. 2016. Greater Manchester accessibility levels (GMAL) model.

- TfGM. 2022. Hospital public transport information: find out how to get to hospitals in Greater Manchester via public transport. https://tfgm.com/public-transport/hospitals.

- Titheridge H, Achuthan K, Mackett R, Solomon J. 2009. Assessing the extent of transport social exclusion among the elderly. J Transp and Land Use. 2(2):31–48. http://jtlu.org.

- Tiznado-Aitken I, Lucas K, Muñoz JC, Hurtubia R. 2020. Understanding accessibility through public transport users’ experiences: a mixed methods approach. J Transp Geogr. 88:102857. doi: 10.1016/J.JTRANGEO.2020.102857.

- van Wee B. 2016. Accessible accessibility research challenges. J Transp Geogr. 51:9–16. doi: 10.1016/J.JTRANGEO.2015.10.018.

- van Wee B, Wee BV, Geurs K. 2011. Discussing equity and social exclusion in accessibility evaluations. Eur J Transp Infrastruct Res. 11(4):350–367. doi: 10.18757/EJTIR.2011.11.4.2940.

- Vecchio G. 2020. Microstories of everyday mobilities and opportunities in Bogotá: a tool for bringing capabilities into urban mobility planning. J Transp Geogr. 83:102652. doi: 10.1016/J.JTRANGEO.2020.102652.

- Vecchio G, Martens K. 2021. Accessibility and the capabilities approach: a review of the literature and proposal for conceptual advancements. Transp Rev. 41(6):833–854. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2021.1931551.

- Vecchio G, Tiznado-Aitken I, Hurtubia R. 2020. Transport and equity in Latin America: a critical review of socially oriented accessibility assessments. Transp Rev. 40(3):354–381. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2020.1711828.

- Wall J. 2021. Older people in Manchester: profile of Manchester residents aged 66+. https://www.manchester.gov.uk/downloads/download/4220/public_intelligence_population_publications.

- Walsh K, Scharf T, Keating N. 2017. Social exclusion of older persons: a scoping review and conceptual framework. Eur J Ageing. 14(1):81–98. doi: 10.1007/s10433-016-0398-8.

- Weil J, Mendoza AN, McGavin E. 2017. Recruiting older adults as participants in applied social research: applying and evaluating approaches from clinical studies. Educ Gerontology. 43(12):662–673. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2017.1386406.

- Wellington J, Szczerbinski M. 2007. Research methods for the social sciences. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- WHO. 2007. Global age-friendly cities: a guide. www.who.int/ageing/enFax:+41.

- WHO. 2015. Word report on ageing and health.

- WHO. 2018. The global network for age-friendly cities and communities: looking back over the last decade, looking forward to the next.

- Yigitcanlar T, Mohamed A, Kamruzzaman M, Piracha A. 2018. Understanding transport-related social exclusion: a multidimensional approach. Urban Policy Res. 37(1):97–110. doi: 10.1080/08111146.2018.1533461.

Appendix 1.

TRSE dimensions adapted from Luz and Portugal (Citation2022, pp 512–515)

Appendix 2.

GMAL Scores